How important are listening and speaking skills? One recent study found that adults spend an average of 70 percent of their time engaged in some sort of communication. Of the time spent communicating, an average of 45 percent is spent listening, 30 percent is spent speaking, 16 percent is spent reading, and 9 percent is spent writing (Adler, Rosenfeld, and Proctor 2012). In other words, 75 percent of all communication in adulthood directly involves listening and/or speaking skills.

Unfortunately, many of our students will soon leave school inadequately prepared to be active listeners and effective speakers (largely because these skills have not been tested). Many of our students come from classrooms where there seems to be “an implicit belief that the subtle skills of active listening and reasoned speaking will develop simply through children’s involvement in whole class and small group dialogues” (ITE English 2014). And while it is true that children will develop their language skills through the traditional “turn-and-talk” kinds of practices found in schools, it is also true that students need much deeper practice before they will become listeners and speakers who will thrive in an ever more complex world.

Because one of the aims of the CCSS is to address career readiness, it makes sense to start thinking about teaching speaking skills by looking at the annual survey by the National Association of Colleges and Employers. In the survey, employers are asked what skills and qualities they look for when hiring students out of college. In order of importance, here are the skills and qualities they value most:

SKILL/QUALITY |

WEIGHTED AVERAGE RATING* |

Ability to verbally communicate with persons inside and outside the organization |

4.63 |

Ability to work in a team structure |

4.60 |

Ability to make decisions and solve problems |

4.51 |

Ability to plan, organize, and prioritize work |

4.46 |

Ability to obtain and process information |

4.43 |

Ability to analyze quantitative data |

4.30 |

Technical knowledge related to the job |

3.99 |

Proficiency with computer software programs |

3.95 |

Ability to create and/or edit written reports |

3.56 |

Ability to sell or influence others |

3.55 |

* 5-point scale, where 1=Not at all important; 2=Not very important; 3=Somewhat important; 4=Very important; and 5=Extremely important. See more at: http://www.naceweb.org/s10242012/skills-abilities-qualities-new-hires/#sthash.bD472ZFL.dpuf.

Source: National Association of Colleges and Employers (2012)

Potential employers list the “ability to verbally communicate with persons inside and outside the organization” as their highest priority skill, which is ironic given the fact that speaking and listening skills receive much less attention in our schools than do reading and writing skills. Our students probably will be doing a lot more talking in the real world than they will be reading and writing, yet you wouldn’t be able to tell this from the over 500 workshops offered at the 2013 National Council of Teachers of English Conference in Boston, where exactly one workshop was offered to help our students improve their speaking skills. One workshop out of 500. For those interested in the math, think about it in these terms: .002 percent of the workshops offered at NCTE in 2013 addressed the skill most valued by employers.

Sadly, it is not hard to figure out the source of the neglect when it comes to the teaching of speaking and listening skills. In the previous educational era (NCLB), speaking and listening skills weren’t tested, and as we know by now, skills that are not tested quickly fall out of favor in the classroom. Speaking and listening skills were no less important in actuality, of course, but without test emphasis on these skills, they withered on the vine. This is yet another argument why our core values should always supersede any current educational testing movement. Speaking and listening skills are important whether they are tested or not, and our job is to teach competency in all four of the language arts (reading, writing, speaking, and listening). This, again, is why hitching instruction only to what is being tested can be harmful to the overall development of our students.

The good news is that the Common Core standards value speaking and listening skills, even if the current exams do not. To be honest, my goal in teaching my students to speak and listen better is not to get them ready for the next wave of exams. Nor is it to prepare them for a successful career at a Fortune 500 company. I am placing more emphasis on speaking and listening skills in my classroom because these skills are foundational to becoming literate human beings. First and foremost, they are important elements of the language arts. If this renewed emphasis on speaking and listening skills also helps my students to score higher on the state exams or helps to position them to secure good jobs, even better.

Before getting into specific speaking and listening strategies, let’s take a look at the Common Core speaking and listening standards, which, at each grade level from kindergarten to grade 12, are divided into two sections: “Comprehension and Collaboration” and “Presentation of Knowledge and Ideas.” As students progress through the grade levels, these standards increase in sophistication. Here, for example, are the speaking and listening standards for grades 9 and 10.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.9-10.1 Initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grades 9–10 topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.9-10.1A Come to discussions prepared, having read and researched material under study; explicitly draw on that preparation by referring to evidence from texts and other research on the topic or issue to stimulate a thoughtful, well-reasoned exchange of ideas.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.9-10.1B Work with peers to set rules for collegial discussions and decision-making (e.g., informal consensus, taking votes on key issues, presentation of alternate views), clear goals and deadlines, and individual roles as needed.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.9-10.1C Propel conversations by posing and responding to questions that relate the current discussion to broader themes or larger ideas; actively incorporate others into the discussion; and clarify, verify, or challenge ideas and conclusions.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.9-10.1D Respond thoughtfully to diverse perspectives, summarize points of agreement and disagreement, and, when warranted, qualify or justify their own views and understanding and make new connections in light of the evidence and reasoning presented.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.9-10.2 Integrate multiple sources of information presented in diverse media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively, orally) evaluating the credibility and accuracy of each source.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.9-10.3 Evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric, identifying any fallacious reasoning or exaggerated or distorted evidence.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.9-10.4 Present information, findings, and supporting evidence clearly, concisely, and logically such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, substance, and style are appropriate to purpose, audience, and task.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.9-10.5 Make strategic use of digital media (e.g., textual, graphical, audio, visual, and interactive elements) in presentations to enhance understanding of findings, reasoning, and evidence and to add interest.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.9-10.6 Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and tasks, demonstrating command of formal English when indicated or appropriate. (See grades 9–10 Language standards 1 and 3 here for specific expectations.) (NGA/CCSSO 2010f)

The remainder of this chapter explores ways to sharpen our students’ speaking and listening skills with specific exercises I have found helpful.

I start by showing students a short clip from a local television newscast and ask them to pay close attention to how a reporter in the field reads the copy. I ask them to note the vocal “moves” the reporter makes: Does he or she pause for effect? When, where, and why does the reporter speed up (or slow down)? When, where, and why does the reporter raise (or lower) his or her voice?

On a second viewing, I have students note the mannerisms employed to make the speech more effective: How are the hands positioned and used? How does the reporter change the angle of his or her head? Are facial expressions used? How is eye contact utilized for effect? Does the reporter stand still, or does the reporter move? Are there graphics or background visuals used to support the speech?

After some practice watching television news, I take excerpts from newspaper stories and I ask my students, “If you were a television reporter in the field, how would you read this copy on the air?” Here is the first line from a recent newspaper article I used in my classroom:

Listen up loners: A new study says having friends can make you smarter, at least if you’re a baby cow. (Netburn 2014)

It is interesting to hear how many ways this line can be read aloud. Pretend you are a reporter in the field and try it. Where do you raise your voice? Do you pause anywhere for effect? What pace “fits” the copy? Do you use your hands? I have students stand up and give their various interpretations of the line, and then I have them practice with more from the same excerpt:

Researchers from the University of British Columbia found that young calves that live alone performed worse on tests of cognitive skill than calves that live with a buddy.

On most dairy farms, calves are removed from their mothers soon after they are born and put in a pen or a hutch where they live alone for eight to 10 weeks while they wean. The practice developed to keep disease from spreading among susceptible baby cows.

But a few years ago, researchers at UBC’s Animal Welfare Program were observing two sets of calves on a farm run by the school. One set of calves had been raised in a group environment—the other set had been raised individually. (Netburn 2014)

To introduce my students to the elements of an effective speech, I use Erik Palmer’s acronym “PVLEGS” found in his excellent book, Well Spoken:

Poise

• Appear calm and confident

• Avoid distracting behaviors

Voice

• Speak every word clearly

• Use a “just right” volume

Life

• Express passion and emotions in your voice

Eye Contact

• Connect visually with the audience

• Look at each audience member

Gestures

• Use hand movements

• Move your body

• Have an expressive face

Speed

• Talk with appropriate speed

• Use pauses for effect and emphasis (2011, 57)

To help familiarize my students with Palmer’s PVLEGS, I play a number of TED Talks for them and have students score the speeches through the PVLEGS lens. We begin by viewing and scoring one together through a whole-class discussion, and from there, students practice scoring a few more in small-group settings before eventually scoring speeches on their own. I use PVLEGS as a scoring guide when the time comes to evaluate my students’ speeches.

Another strategy recommended by Erik Palmer, this time in his book Teaching the Core Skills of Listening and Speaking, is the Poker Chip Discussion (2013). Prior to whole-class discussion, each student is handed a poker chip. Students “spend” their chips by talking, and all students are asked to spend their chips before the end of the discussion (depending on the situation, the teacher might start each student off with two or three chips instead of just one). This strategy encourages all students to participate, instead of the usual five or six students who typically carry the conversation. It is a low-stress way to make sure all voices are heard.

Students in my class often read self-selected books (more on this in Chapter 8). The Interrupted Book Report is an accountability measure for self-selected reading, but it also strengthens students’ speaking skills. I pick a student randomly and have her stand up and tell the class about the book she is reading. At some point while the student is talking, I interrupt by calling out, “Stop.” Sometimes I let the speaker talk for a minute or two; sometimes I cut her off (often mid-sentence) after a few seconds. I then call on another student and he stands and starts sharing a summary of his book. The Interrupted Book Report is fun, because students don’t know when the “stop” will come. They have to keep talking until they hear it. The other benefit, of course, is that students get to hear what others in the class are reading. Interrupted Book Reports often serve as commercials for what students might read next.

If the class is reading a whole-class novel, the Interrupted Book Report is a good review strategy. A student begins by retelling what happened from the beginning of the book (or from the beginning of the chapter) and when she is stopped, another student is chosen to pick up the summary exactly where the first student stopped. This second student continues the summary until he is interrupted, and a third student is then called to pick up from where the latest interruption occurred. And so forth. Because students are picked randomly to continue the summary wherever it may be interrupted, this sharpens listening skills as well.

Esquire magazine prints letters from its readers in every issue, but what is really funny is that the magazine always features one line out of context from a letter they have decided not to publish. Here are some recently published, context-free sentences from various issues:

“Did you know that she went to Space Camp three times?”

“I woke up at 6:00 a.m. just to brush my teeth.”

“The next day, I’d apply a tincture of benzoin to the blister, pop in a plastic tooth guard, and go at it again.”

After introducing the concept of the context-free sentence, students are asked to revisit their writer’s notebooks and to choose one line out of context to read to the rest of the class. But I don’t want them to simply read their lines; I want them to read their lines dramatically. Even though it’s only one line, I want each student to consider PVLEGS when deciding how to deliver it. I model this by choosing one line I have written and performing it with the elements of PVLEGS in mind.

When we begin sharing the lines out loud, I do not indicate any order of speakers. I require every student to stand and deliver one context-free line, and I set a time limit of five minutes for everyone to have shared. Who goes first and who goes next is up to the students (this creates a funnier chain of context-free lines). If a student asks, “How will I know it’s my turn?” I reply with, “It is your turn when no one else is talking.”

In a novel, the reader has to read many chapters before finding out the resolution. In Of Mice and Men, for example, the reader does not find out Lenny’s fate until very late in the novel. Newspaper articles, on the other hand, are often written in the exact opposite fashion. They adopt the “inverted pyramid format,” in which the “ending” is revealed in the lead paragraph. An example:

Los Angeles (CNN) — A magnitude-5.1 earthquake struck the Los Angeles area Friday night, jolting nearby communities and breaking water mains in some neighborhoods. Its epicenter was in Orange County, one mile east of La Habra and four miles north of Fullerton, the U.S. Geological Survey said. (Karimi and Sutton 2014)

In inverted pyramid writing, the reader is told what happened immediately, and he or she can choose whether to read deeper into the article for further details.

Once students understand how newspaper leads are written, I model how a newspaper lead for a novel might be written. The lead for Of Mice and Men, for example, might read as follows:

Weed, CA — In what some are calling an act of mercy, George Milton, an intelligent but uneducated man, shot and killed his friend, Lennie Small, after it was found that Small had accidentally broken the neck of Curley’s wife. Milton allegedly acted to prevent Small from facing a painful death from the lynch mob that was closing in on him.

When students finish a whole-class book study, I often have them write one-paragraph leads recapping the books. I ask them to stand up and share them in front of the class. There are two benefits to this activity: (1) it strengthens summary skills and (2) it presents students with a low-pressure way to get up in front of the class and practice their oral skills. Writing one-paragraph leads can also be assigned after reading specific chapters.

When students draft a speech they have to know their purpose and their audience, because knowing purpose and audience not only determines how the speech will be written but also determines how the speech will be delivered. If, for example, you are giving a speech about the intricacies of basketball, your speech to a group of college basketball coaches is going to sound very different from your speech to a class of third graders. Who receives the speech determines how it should be written and delivered.

For the 2 x 2 Speech assignment, students are asked to take one topic and write to two different audiences: two 2-minute speeches. Sam, for example, first wrote a two-minute speech explaining how to excel at playing Call of Duty with a high school audience in mind. He then rewrote the speech so that it would be understandable to his grandmother. The 2 x 2 Speech assignment teaches students to pay close attention to purpose and audience. Students can then be asked to give one—or both—of their speeches.

Favorite 5 is a writing assignment, but it easily can be turned into a short speech. I begin by modeling my Favorite 5s in a number of areas:

Favorite 5 Baseball Players of All Time

Hank Aaron

Willie Mays

Pete Rose

Greg Maddox

Mike Trout

Favorite 5 Bill Murray Films

Lost in Translation

Groundhog Day

Caddyshack

Rushmore

Favorite 5 Candy Bars

Snickers

Butterfinger

Three Musketeers

Heath Bar

Chick-O-Stick

Favorite 5 Television Characters

Phil Dunphy (Modern Family)

Frank Underwood (House of Cards)

“Matt LeBlanc” (Episodes)

Walter White (Breaking Bad)

John Luther (Luther)

Once students have generated a number of Favorite 5 lists, they choose one list and write a defense of it. They then stand up and orally defend their lists.

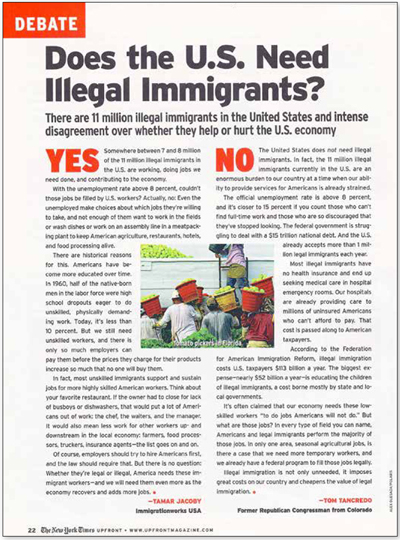

Another written assignment that lends itself to having students speak in front of the class is the Yes/No Argument, which I have modeled after a column featured in Upfront magazine. This column features a debatable question (e.g., “Does the U.S. Need Illegal Immigrants?” [Jacoby and Tancredo 2012]) and runs opposing arguments (see Jacoby’s and Tancredo’s responses in Figure 7.1). Students are then asked to generate argumentative questions they care about and to write both sides of the argument. See Figure 7.2 for Jesuson’s arguments on whether schools should offer cash bonuses for good test scores.

Figure 7.1 Upfront’s Yes/No Argument

Figure 7.2 Jesuson’s Yes/No Argument

Once students have written both sides of the issue, I randomly select them to stand up and read one or both sides of their arguments.

I use the 4 x 4 Debate after students have diligently researched a given issue. Begin by placing four chairs in a row in the center of the classroom (I clear out all the other furniture to the periphery). Have the students who support a “yes” position stand in a group behind these chairs. Take another four chairs, and place them in a row facing the first set of four chairs. Have the students who support a “no” position stand in a group behind these chairs. Tell the students that you, the teacher, will randomly choose debate team members to fill the chairs and that all students will have five minutes to put their heads together to help the chosen four consider the following: their main argument points, the counterarguments they will soon hear, and how they will respond to these counterarguments. If it is helpful, they can scribble bullet notes.

Though there are eight total chairs (four on each side facing each other), when it comes time to start the debate, I choose six students to participate, three on each side. This leaves an open chair on each side of the debate—sort of a “wild card” seat that can be filled at any time by any outlying student who wants in on the action. If all four seats are filled and another student wants to join the debate in progress, he or she simply walks behind a seated debater and taps that student on the shoulder. That student must then exit the debate, and the person who tapped the shoulder then slides into the chair.

To encourage reasoned debate (instead of having the exercise devolve into a shouting match), each side can speak only when it is their turn. The turns are set up as follows.

Three minutes |

Side A chooses a spokesperson to give an opening statement. Side B listens. |

Three minutes |

Side B chooses a spokesperson to give an opening statement. Side A listens. |

Two minutes |

Side A has the floor, and anyone on that team may speak. They can continue to deepen the arguments they introduced in their opening statement, or they can begin to refute what the other side said in their opening statement. Or they can do both. Side B listens. |

Side B has the floor, and anyone on that team may speak. They can continue to deepen the arguments they introduced in their opening statement, or they can begin to refute anything the other side has said to this point. Or they can do both. Side A listens. |

|

4 minutes |

Both sides leave the debate and return to their groups away from the four chairs to strategize where their argument(s) should go next. After four minutes, each side returns to its four chairs. They can choose to return the same four students, or they may elect to replace them with new representatives. |

Two minutes |

Side A has the floor and the debate continues. Side B listens. |

Two minutes |

Side B has the floor and the debate continues. Side A listens. |

Two minutes+ |

This two-minute back-and-forth rhythm is repeated until the debate has run its course. Create other group breaks if necessary. |

When the debate concludes, all students (whether they actively participated or not) are asked to write reflections. Here are some questions they might consider:

• Who “won” the debate? Why do you think so? Be specific.

• What grade would you give your team for its performance in the debate? Explain.

• Did the debate change your mind on this issue in any way? Explain.

• Reflect on something you learned in the debate.

• What was not said in the debate that should have been said? What was left out? Had it been said, how might that have changed the course of the debate?

Students are then chosen randomly to stand up and to share their reflections.

A variation to the 4 x 4 Debate: If you want to throw your students a curveball before the debate starts, force the teams to switch sides at the last minute. Those who believe “A” are now required to argue in favor of “B”; those who believe “B” are now required to argue in favor of “A.”

I like to use this strategy after students are assigned a large chunk of text to read. I place them in a circle, and I begin with a very simple direction: “Say something.” One student says something to get the conversation started, and then a second student can either add to what has already been said or can take the conversation in a new direction. The order of speakers can be predetermined by simply going in a clockwise direction, or the conversation can be wide open, so that it jumps randomly around the circle. If I choose the latter, I trace the conversation (see below).

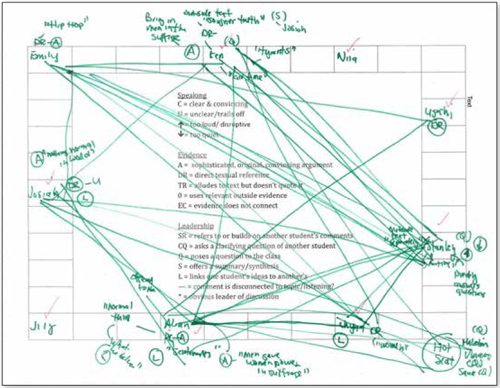

I often use the Trace the Conversation activity when my students are gathering to discuss a book they are reading. In Socratic Seminar fashion, desks are placed in a rectangular seating arrangement so that students are facing one another when discussing the topic at hand. Before the conversation begins, students are told that I will trace the trajectory of the conversation and that I will score their participation on three levels: speaking, evidence, and leadership. To help assess the quality of the conversation, my colleague Justin Boyd created symbols to help keep track of the talk:

Speaking

C = Clear and convincing

U = Unclear/trails off

= Too loud/disruptive

= Too loud/disruptive

= Too quiet/hard to hear

= Too quiet/hard to hear

Evidence

A = Sophisticated, original, convincing argument

DR = Uses direct textual reference

DNQ = Alludes to text but doesn’t quote it

O = Uses relevant outside evidence

EC = Evidence does not connect

Leadership

BLD = Refers to or builds on another student’s comments

CQ = Asks a clarifying question of another student

Q= Poses a question to the class

S = Offers a summary/synthesis

L = Links one student’s ideas to another’s

— = Comment is disconnected to topic/listening?

* = Obvious leader of discussion

There is no particular order given to the conversation, and when it begins, I trace the trajectory of it on my seating chart. If, for example, Josiah starts the conversation and Alan speaks next, I draw a line from Josiah to Alan on the chart to show the direction of the conversation. If Stanley then speaks after Alan, I draw the line from Alan to Stanley. And so forth. Each time someone speaks, I quickly add one or more of the symbols next to his or her name so that later I will remember what he or she added to the conversation. By the end of the discussion, I have a visual that shows the history of who spoke (and how many times), who did not speak, and what each person contributed to the discussion. In Figure 7.3, you will see an example that my colleague, Martin Palamore, created to track a small-group conversation in his middle school history class. See Appendix B for a blank copy of the conversation chart, or download a copy of the chart at kellygallagher.org (click on “Resources” and select the “Track the Conversation” chart).

Figure 7.3 Tracing a conversation in a middle school history class

The Teach Us Something assignment is a simple way to get students up and talking in front of the class. The title is self-explanatory: Each student is given four minutes to teach the class something we didn’t already know. Students are encouraged to support their teaching lesson with visual aids. The students and I enjoy this assignment because no two speeches are alike and we all learn.

I want students to know there is a difference between hearing and listening. Listening moves deeper than simply hearing. It requires a level of focus. To work on developing my students’ listening skills, I place them in a circle (they can be whole-class circles or small-group circles) and hand each one of them a playing card. A random topic is thrown out (e.g., “names of candy bars,” “characters in To Kill a Mockingbird,” “words that start with Th”) and one student is selected to share an answer. If the topic is “fast food restaurants,” for example, the student chosen to speak first says, “McDonald’s,” and then the conversation moves clockwise to the next person in the chain. The second person calls out a different answer (“Burger King”), and then it moves to the third person in the chain. Students remain in the chain if they can come up with an answer that has not yet been said (this is where the listening skills come into play). If a student cannot think of an answer, or if the student repeats an answer that has already been said, he or she drops out of the chain (which is demonstrated by dropping the playing card onto the floor). The last person holding a playing card wins. To raise the pressure a bit, I often impose a five-second response time.

Regrettably, memorization has become a lost art in our schools. This is unfortunate, as Tom Newkirk reminds us in The Art of Slow Reading, because having students memorize meaningful historical passages is not simply an exercise in rote learning, “it is claiming a heritage. It is the act of owning a language, making it literally a part of our bodies, to be called upon decades later when it fits a situation” (2011, 77). Memorization, Newkirk argues, “allows language to be written on the mind” (2011, 76).

At the Harlem Village Academies High School (where I taught one year), it is standard practice that students conduct declamations, which are defined “as a recitation of a speech from memory with studied gestures and intonation as an exercise in elocution or rhetoric” (Vocabulary.com 2014). For example, students in history classes are asked to memorize and perform passages from iconic speeches (to see Sheck’s performance of Napoleon Bonaparte’s proclamation to his soldiers, search “SM Declamation” on YouTube). In my English classes, I traditionally have students memorize twenty lines of Shakespeare (to see Felipe perform the famous advice scene in Hamlet, search http://www.kellygallagher.org/instructional-videos/).

Newkirk advocates another way to get students to practice their memorization skills in front of the class: Assign them to tell a joke. He cites the third-grade classroom of Tomasen Carey, who prepared her students “by first telling a joke herself, stressing the way a joke builds often through repetition, often of three instances (like so many fairy tales). She discussed the use of voices and pacing, creating anticipation for the punch line” (2011, 86). When we did this assignment one year, I had students consider the elements of PVLEGS as they practiced their deliveries. Before you ask students to stand in front of the class to deliver their jokes, introduce two major ground rules: (1) the selected jokes have to be appropriate for the classroom and (2) students have to practice the joke numerous times in different small groups where they receive suggestions from their peers on how best to deliver them (Newkirk 2011).

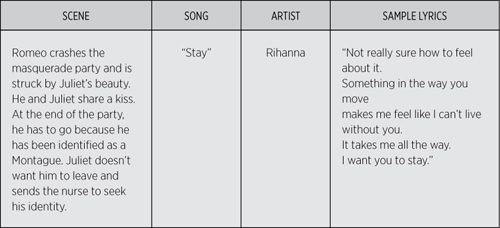

This is a written assignment that I have students turn into a speech. The assignment is simple: Students create a soundtrack to accompany a book or play. I have the students pick scenes from the books they are reading and match them to appropriate songs. I model this with a song that I have selected for the masquerade scene in Romeo and Juliet:

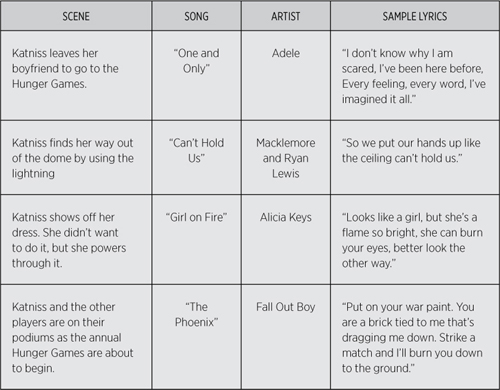

Here are songs Dyamond selected for scenes in Catching Fire by Suzanne Collins (2009):

Once the students have chosen their songs, they give three-minute speeches explaining and defending their selections. Many students weave the music into their talks.

My friend Penny Kittle turned me on to the power of spoken poetry in the classroom, a good way to get students up and speaking in front of the class.

I begin by sharing a number of spoken poems with my students (for a list of high-interest spoken poems, go to kellygallagher.org and search “Kelly’s Lists” under “Resources”). When we read a poem for the first time, students put their pens or pencils down and simply enjoy and absorb it. Many of the poems are on YouTube, so we watch and listen to them being read by the poets. In the second-draft reading, we reread the poem, this time marking the “hot spots”—words, phrases, or lines that jump out at us. Once the hot spots are identified, we each choose one and begin writing. Some choose to write poems, others create prose. I do this first, projecting my draft on the screen for students to see as I think out loud while writing. After five minutes or so, I ask my students to begin writing as well, and we begin writing concurrently.

Getting a rough-draft poem down on paper is jusst a start. After we have written a number of them, we pick one poem to take into revision. In Figures 7.4a and 7.4b, you will see how much my poem changed over the course often revisions, all of which were done—five minutes at a time—in front of my students. I began with a line from Phil Kaye’s (2011) “Repetition” (“If you watch the sun set too often, it just becomes 6 p.m.”), and it is interesting to note that even though that was the line that sparked me to begin drafting, it is a line that did not make it into the final draft of the poem. My last draft ended up far from my first draft.

Figure 7.4a My first poetry draft derived from Phil Kaye’s “Repetition”

Figure 7.4b My second poetry draft derived from Phil Kaye’s “Repetition”

Once we have taken our poems through a number of revisions, it is time to share them with the rest of the class. I pass out a sign-up sheet, and when the scheduled day arrives, students get up and perform their poems to the class.

To develop my students’ listening skills, I use a number of website resources. Here are three of my favorites:

• “Top 100 Speeches”: I have students listen to some of the “Top 100 Speeches” found on the American Rhetoric (2014) website (americanrhetoric.com/ top100speeches). Most of these speeches come with both audio recordings and transcripts, but in order to sharpen my students’ listening abilities, I have them listen and take notes without the texts of the speeches in front of them. Not only do these speeches help my students improve their listening skills, they also shore up their lack of historical knowledge.

• “Left, Right, and Center”: Los Angeles public radio station KCRW’s free weekly podcast “Left, Right, and Center” provides a “civilized yet provocative antidote to the screaming talking heads that dominate political debate” (KCRW 2014). On this show, a panelist from the political left, a panelist from the political right, and a panelist from the political center civilly argue the week’s events. Students are asked to take notes on the arguments made on both sides of the issues, and once the podcast is over, I often ask students to share their thinking in writing. Like the “Top 100 Speeches” assignment, this activity has proved invaluable in broadening my students’ knowledge of the world.

• Old Time Radio: Another website that is excellent for building listening skills is RadioLovers.com, where access to classic radio shows is one click away. Teachers can choose from dramas, comedies, mysteries, westerns, science fiction, superheroes, or musicals.

For these listening exercises, students might be asked to apply what are traditionally considered to be reading and writing strategies. As they listen to old time radio programs, for example, I might have students chart literary elements (e.g., theme, foreshadowing) or the structure of the plot (e.g., rising action, conflict). While listening to political speeches or debate, I might have them chart both what was said and what was not said.

Students can develop their oral literacies by creating podcasts. A good place to start is with the Smithsonian American Art Museum (2014), which provides guidelines on how students can build podcasts around one or more of the pieces of artwork in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s collections (see http://americanart.si.edu/education/resources/guides/podcast.cfm). Students choose an artwork, research it, and then write scripts aimed at hooking the listeners. The Smithsonian website offers teachers support materials—from how to technically set up the podcasts to providing student models.

Play a modified version of the childhood game “telephone” to build listening skills. A message is whispered to one child, who then whispers into the ear of another child, who then, in turn, whispers it to the next child. The message is passed from child to child until it passes through the entire class. The goal is simple: to keep the message as close to the original as possible. I have older students play telephone as well, but I up the ante a bit. Not only do I start the game with a message to the first student but also I give a second message to the last student, thus creating a game where different messages are heading in opposite directions. To make it harder, I sometimes play annoying music in the background while the game is in progress, or I talk over the students as the messages are being passed.

Almost all schools have morning announcements. Administrators at the Durham Academy in Durham, North Carolina, decided to have some fun when they announced via video that there would be no school due to a snow day: http://www.g105.com/onair/brooke-50858/the-coolest-snow-day-announcement-you-will-ever-see-12062707/.

Have students create and film their own short morning announcement clips. Here are some topic possibilities for the school announcements:

• Results of a recent game or academic competition

• Student-of-the-month announcement

• Announcement of an upcoming event (game, dance, club meeting)

• A “shout out” for students or staff who deserve recognition

• College acceptance announcements

• Announcement of results on a test, essay, or project

• Preview of an upcoming assembly (or recap of an assembly)

• Infomercial for a given day or time period (e.g., Veteran’s Day, Black History Month)

National Geographic posts thousands of interesting short videos on its website (http://www.nationalgeographic.com). The topics range from animals to geography to weather disasters. For example, I may have students watch a clip on the violence exhibited by humpback whales (National Geographic 2014; to see the video “Wild Hawaii: Violence in the Deep,” go to http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/wild/wild-hawaii/videos/violence-in-the-deep/?videoDetect=t%252Cf). As students watch, they are asked to take notes, writing down as many factoids as they can as they listen to the narration.

After showing the video, I place students in a circle. I start with the student to my left and ask him or her to share one factoid. The conversation then moves clockwise, and each student is asked to “add 1”—to share one factoid that has yet to be shared. If a student cannot add 1, or if a student repeats a factoid that has already been shared, he or she is out of the competition. The last student to present a fresh fact is the winner.

When students are first learning this activity, I allow them to consult their notes during the competition, but if I want to up the ante a bit, occasionally I will have them compete without their notes after giving them a moment or two to review them.

Many of the reading activities described in Chapter 2 and many of the writing activities described in Chapter 4 can also be adapted into short speech activities. For example, a student who has written a 17-word summary could be asked to stand up and share his or her response orally. Here is a list of strategies mentioned in Chapters 2 and 4 that easily could be turned into opportunities for our students to speak and to listen:

What I am advocating in this chapter flies in the face of what is currently favored by the latest rounds of testing of Common Core standards—at least on the speaking side of things. Yes, students might be asked to listen to a speech as part of a state test and be required to respond to it—and this is a step in the right direction—but it remains highly unlikely that students will be tested on their ability to speak effectively. If history is any indicator, what is not tested will fall out of favor in our nation’s classrooms, which means teaching students how to speak effectively will be placed on the back burner. This is yet another example where teaching blindly to the latest round of tests is not in the best interest of our students. The development of our students’ speaking and listening skills should remain a priority regardless of what is valued by this year’s exam.