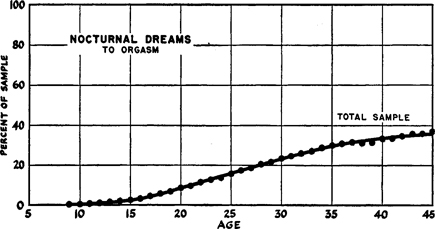

Figure 21. Accumulative incidence: nocturnal dreams to orgasm

Each dot indicates percent of sample with experience in orgasm by the indicated age. Data from Table 42 .

The nocturnal sex dreams 1 of males have been the subject of extensive literary, pornographic, scientific, and religious discussion. The male, projecting his own experience, frequently assumes that females have similar dreams, and in erotic literature as well as in actual life he not infrequently expresses the hope that the female in whom he is interested may be dreaming of him at night. He may think it inevitable that anyone who is in love should dream of having overt sexual relations with her lover. 2 But relatively few records of female dreams have been available to establish such a thesis. 3 Even some of the best of the statistical studies of sexual behavior have failed to recognize the existence of nocturnal dreams in the female. 4

This is curious, for it has not proved difficult to secure data on these matters. Females who have had nocturnal sex dreams seem to have no more difficulty than males in recalling them, and do not seem to be hesitant in admitting their experience. Whether or not they reach orgasm in these dreams is a matter about which few of them have any doubt. Because the male may find tangible evidence that he has ejaculated during sleep, his record may be somewhat more accurate than the female’s; but vaginal secretions often bear similar testimony to the female’s arousal and/or orgasm during sleep. As with the male, the female is often awakened by the muscular spasms or convulsions which follow her orgasms. Consequently the record seems as trustworthy as her memory can make it, and the actual incidences and frequencies of nocturnal orgasms in the female are probably not much higher than the present calculations show. The violence of the female’s reactions in orgasm is frequently sufficient to awaken the sexual partner with whom she may be sleeping, and from some of these partners we have been able to obtain descriptions of her reactions in the dreams. There can be no question that a female’s responses in sleep are typical of those which she makes when she is awake.

Masturbation and nocturnal sex dreams to the point of orgasm are the activities which provide the best measure of a female’s intrinsic sexuality. All other types of sexual activity involve other persons—the partners in the sexual relations—and the frequencies and circumstances of such socio-sexual contacts often depend upon some compromise of the desires of the two partners. The frequencies of the female’s marital coitus, for instance, are often much higher than she would desire, and even those females who are most responsive in their sexual relations might not choose to have coitus as often as their spouses want it. Since other persons have a minimum effect upon the incidences and frequencies of masturbation and nocturnal sex dreams, these latter outlets provide a better measure of the basic interests and sexual capacities of the female.

Whether sexual responses originate through the physical stimulation of some body surface, or through some psychologic stimulation by way of the cerebrum, they are mediated primarily through lower spinal centers and the autonomic nervous system (Chapter 17 ). Ultimately all parts of the nervous system become involved; and all parts of the body which are nervously controlled, especially those which are controlled by the autonomic nervous system, may be affected. Whenever there is sexual. arousal the muscles of the body respond, as we have already noted, with a rhythmic, involuntary flow of movement which is one of the most characteristic aspects of sexual behavior, and at orgasm the body may be thrown into localized or more general spasms or convulsions. All of this seems to be as true of sexual responses and orgasm reached during sleep as it is of sexual reponses and orgasm reached while one is awake. 5

Sexual responses in sleep may differ, however, from the responses which one makes when awake, in the fact that the learned controls and inhibitions which an individual has acquired in the course of his or her lifetime are less likely to operate in sleep. The content of the dream, the speed of the response, and the abandon of the activity in orgasm may be less obstructed by rational controls. The dreams, particularly in the male, may include socially taboo types of behavior, unconventional sexual techniques, contacts with children and with relatives (incestuous relations), exhibitionistic performances, group activity, fantastic and physically impossible techniques, and still other types of activity and partners which the individual certainly would not accept if he or she were awake. 6 One of the most characteristic aspects of nocturnal sex dreams is the speed with which they carry the individual to orgasm, even though he or she may be quite slow in response while awake. An occasional female who finds it difficult to release her inhibitions and reach orgasm while awake may be able to reach it in sleep. There are some females (5 per cent), just as there are some males, who experience nocturnal dreams to orgasm before they have ever experienced orgasm from any other source while they are awake (Table 148 ). 7

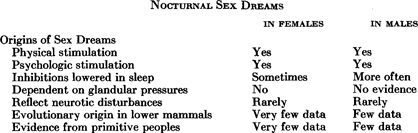

Among both females and males, nocturnal sex dreams, more than any other type of sexual outlet, appear to have their origins in what are primarily psychologic stimuli. 8 It seems true that the direct physical stimulation of an individual’s body by night clothing, the bed covers, the bed partner, and other pressures on the reposing body may sometimes provide physical stimulation which is sufficient to produce orgasm. The physiologic condition of an individual, including her hormonal constitution, may also have a great deal to do with determining the frequencies of her sex dreams; and her nutritional state, her general health, her fatigue, the temperature of the room, and still other physical and physiologic factors may contribute to the origin of the dreams. Certainly there is a portion of the daytime sexual activity of the male and more of the daytime activity of the female which depends primarily on physical stimulation, with a minimum accompaniment of any psychologic imagery or fantasy; but the physical and physiologic stimuli which seem conducive to the development of orgasm in sleep are rarely of the sort which would be sufficient to produce orgasm when one is awake. It is not impossible, and it is even quite probable that a lowered threshold of response during sleep makes it possible for a lesser physical stimulus to precipitate sexual responses at that time; but if physical stimuli alone were sufficient, one might expect them to produce nocturnal orgasms with considerable regularity and with much greater frequency than they usually occur, for the necessary physical and physiologic conditions would appear to be present quite regularly under normal sleeping conditions. It seems probable, therefore, that psychologic stimuli are involved to a greater extent than any of the physical and physiologic factors.

One of the most characteristic aspects of the orgasms which occur while an individual sleeps is the fact that they are almost always accompanied by dreams, even among females who are rarely or never given to sexual fantasy while they masturbate or engage in any other type of daytime sexual activity. The amount of nocturnal orgasm which occurs in the female without any consciously remembered dream is small (p. 212). It involved something like one per cent of the females in the sample (Table 41 ), and there is some reason to doubt whether the failure to recall dreams is sufficient evidence that they did not occur. We are inclined to agree with most psychologists and psychiatrists in believing that the dreams are not only necessary factors in the great majority of cases, but the prime precipitating factors of most nocturnal orgasms; but the physiology of the matter is still poorly understood, and further studies must be made before we can be certain of the extent to which the dreams may actually dominate the situation. The elucidation of this problem should further our understanding of the psychology of female sexuality in general.

In respect to the male, the opinion is quite generally held that nocturnal emissions are the product of “accumulated pressures in reproductive glands.” It is implied that semen accumulates in the testes (!), and that when those glands become full the resultant pressures touch off some mechanism which leads to orgasm and to seminal discharges in sleep. 9 The anatomy and physiology in any such explanation is, however, quite incorrect. As we have already noted in the volume on the male, semen consists primarily of secretions of the prostate gland and seminal vesicles, and it receives only a microscopic bit of sperm from the testes themselves (p. 612). There seem to be no sufficient data to show that pressures in the prostate and seminal vesicles, or in any other glands, actually stimulate the lower spinal centers which are concerned in sexual responses. The very fact that females, without testes, prostate glands, or seminal vesicles, still have nocturnal orgasms provides good evidence that glandular pressures probably have little or nothing to do with nocturnal emissions in the male. When mechanical stimulation results in nocturnal orgasms, it is more likely to be the tactile stimulation of some body surface which is involved.

At various points in the literature the opinion has been expressed that nocturnal dreams in the female are an expression of some neurotic disturbance, 10 and that “normal,” well adjusted females do not dream to the point of orgasm. The very fact that nocturnal sex dreams are not as universal in the female as they are in the male seems to have contributed to the opinion that they are pathologic. There is a tendency to consider anything in human behavior that is unusual, not well known, or not well understood, as neurotic, psychopathic, immature, perverse, or an expression of some other sort of psychologic disturbance. Curiously enough, the persons who contend that sex dreams represent neurotic disturbances in the female admit that it is impossible to believe that 80 per cent or more of the male population is to be considered neurotic simply because that percentage has nocturnal sex dreams which effect orgasm.

It is true that we have few phylogenetic data to establish the evolutionary origin of these dreams in man, for we know of only two instances of nocturnal sex dreams among the females of any lower species of mammal, and only two or three instances in male mammals outside of man. 11 It is, however, very difficult to secure evidence of such dreams in an animal that cannot report its experience, and it is quite probable that further studies will show that such dreams not infrequently occur in other mammalian species. Consequently, one cannot conclude that the near absence of data proves that there is no evolutionary precedent for their occurrence in the human female.

Similarly, there are few records of nocturnal sex dreams among the females of any pre-literate people, although there are more records of sex dreams among males of such groups. 12 This probably proves nothing, although it may suggest that females among primitives, just as among present-day American groups, do not dream to the point of orgasm as frequently as males.

General Summary . At some time prior to the contribution of their histories, approximately two-thirds (about 65 per cent) of the females in the sample had dreams that were overtly sexual (Table 41 ). For 20 per cent the dreams had proceeded to the point of orgasm, although these same individuals had sometimes had sex dreams without orgasm. Some 45 per cent reported having sex dreams which, however, had never reached orgasm. As with the male, the dreams often had a distressing way of stopping just short of the climax of the activity. 13

The accumulative incidence curves indicate that 37 per cent of the females in the sample had experienced dreams which had led to orgasm by the age of 45 (Table 42 , Figure 21 ). This means that 63 per cent had not dreamed to orgasm by that age. The data on the present sample indicate, however, that nearly half of this 63 per cent (i.e. , 34 per cent of the total female sample) had had dreams without orgasm. Including females of all ages, it may, therefore, be estimated that a total of more than 70 per cent have sex dreams in the course of their lives, whether with or without orgasm. 14

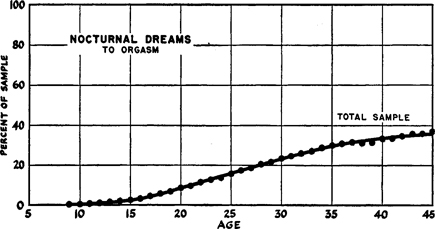

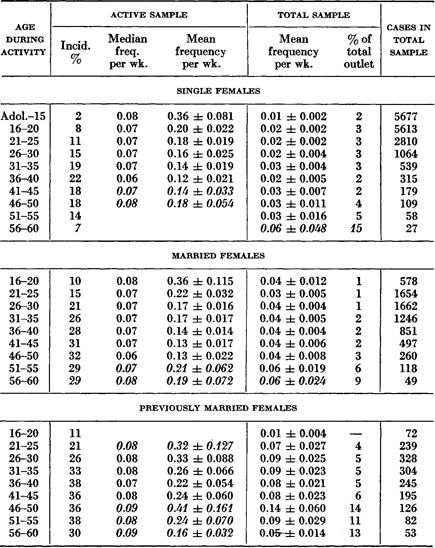

The number of females in the sample who were experiencing nocturnal dreams to the point of orgasm (the active incidence ) in any particular five-year period was, however, small. The incidences ranged from 2 to 38 per cent in the various age groups, but they were usually between 10 and 33 per cent (Table 43 , Figure 22 ). Because of the low frequencies with which such dreams occur, it is probable that not much more than 10 per cent of the females in the population which is adolescent or older in age, have nocturnal dreams to the point of orgasm within any single year.

Figure 21. Accumulative incidence: nocturnal dreams to orgasm

Each dot indicates percent of sample with experience in orgasm by the indicated age. Data from Table 42 .

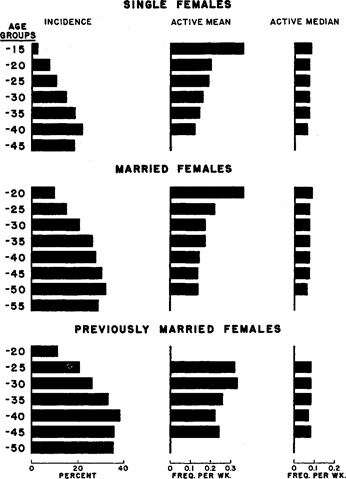

In the sample, the average (median) female who had had sex dreams to the point of orgasm (Table 43 ) was having such dreams at a rate of 3 or 4 times per year (an active median frequency of 0.06 to 0.08 per week). For perhaps 25 per cent, the experience had not occurred more than 1 to 6 times in their lives (Figure 23 ). In the total female sample, regular frequencies had occurred as follow: 15

8% with frequencies over 5 per year

3% with frequencies over 2 per month

1% with frequencies over 1 per week

The most extreme frequencies in any individual history were also low. There were only seven or eight histories among the nearly six thousand in which the dreams had occurred with average frequencies of more than 1.5 per week (three times in two weeks) during any five-year period. There were only one unmarried female over thirty years of age, two or three married females over forty years of age, and four previously married females over forty years of age who had had dreams which average more than once per week. For some other females, exceptional circumstances had produced several nocturnal dreams within a particular week, or even two or three times in a single night, but this was a very rare occurrence. 16 Such high frequencies had almost never extended over any prolonged period of time.

Figure 22. Active incidence, mean, median: nocturnal dreams to orgasm, by age and marital status

Data from Table 43 .

Among women who had been deprived of some drug to which they had been addicted, we have five cases of a considerable increase in the frequencies of sex dreams to orgasm for a matter of a few days or a week or two, but such withdrawal symptoms are more marked among men and less frequently seen among women.

Figure 23. Individual variation: frequency of nocturnal dreams to orgasm

For three age groups of married females. Each class interval includes the upper but not the lower frequency. For incidences of females not dreaming to orgasm, see Table 43 .

In most male groups there are individuals who have nocturnal emissions with frequencies which average as high as four to seven, and in some instances as high as fourteen per week over some period of years (see our 1948:521). The range of the variation in the frequencies of nocturnal dreams to orgasm is, therefore, much more limited among females. This is the only instance of a sexual outlet in which the range of individual variation is more limited among females than it is among males. As we have already noted (Chapter 5 ), there are females who do not masturbate more than once or twice in a lifetime, and there are females who report masturbating to orgasm as frequently as a hundred times in an hour (p. 146); such exceedingly high rates are never approached by the male. In their pre-marital petting, there are some females who reach orgasm more frequently than any known male. Similarly, the maximum frequencies of orgasm among females in coitus may far exceed the maximum frequencies attained by any male (p. 350). It is only in the frequencies of nocturnal orgasms that the maximum frequencies for the females fall below the maximum frequencies for the males. In sexual responses which depend primarily upon physical stimulation, the extreme females surpass the males; but in such responses as dreaming to orgasm, which depend primarily upon psychologic stimuli, the males surpass the females.

There were some females, including as many as 2 per cent of those with masturbation in their histories, who were capable of reaching orgasm through fantasy alone (Table 37 ), and this is beyond the capacity of almost any male. This would seem evidence of a high level of psychologic response in those particular females. But even these most responsive females do not have nocturnal orgasms with frequencies which approach those of the more responsive males or even of the average male. It is not immediately apparent why the psychologic responsiveness of a female when she is awake should not be correlated with a similar level of responsiveness when she is asleep.

The frequencies with which the average female in the sample had had nocturnal orgasms (the active median frequencies) were more or less constant for the single and married females of all age groups from adolescence to forty or fifty years of age; for the females of the grade school, high school, college, and graduate school levels; for the females of the various religious, occupational, and rural-urban groups on which we have sufficient data; for the females who became adolescent at various ages; and for the females of the several generations represented in the sample. This is one of the significant aspects of the record. The detailed data, with especial emphasis on the few groups in which there is any significant variation from the general rule, are discussed below.

Relation to Age and Marital Status . Nocturnal sex dreams had occurred among fewer of the younger females (the active incidence ), and among many more of the older females in the sample. It was about 2 per cent who had had dreams to orgasm between adolescence and 15 years of age, but the percentages increased in the older groups. 17 Some 22 to 38 per cent of the females in the sample were having such dreams between the ages of forty and fifty (Table 43 , Figure 22 ). After that the incidences began to decline. We have only one instance of a female over seventy years of age who was having sex dreams to orgasm.

In contrast to the above, the male peak in nocturnal dreams is reached in the late teens or twenties (see our 1948:242), some twenty or thirty years before the female reaches the peak of her dream activity. The later development in the female of an outlet which so largely depends upon psychologic stimuli is a matter that must he considered in any comparison of the female and the male (Chapter 16 ).

While the number of females who were dreaming to orgasm increased with advancing age, there was no correlation between the age of the individual and the frequencies with which she was having experience (Table 43 , Figure 22 ). The average frequencies for those who were having dreams (the active median frequencies ) remained around 3 to 4 times per year from adolescence to the oldest age groups on which we have good samples—at least to age sixty-five.

A somewhat lower proportion of the single females, a higher proportion of the married females, and a still higher proportion of the previously married females were having sex dreams to orgasm (the active incidences) (Table 43 , Figure 22 ). The peak for the single females had come at age forty with 22 per cent involved; it had come for the married females at age fifty with 32 per cent involved. For the previously married females it had come at age fifty-five with 38 per cent involved.

Interesting to note, however, the average frequencies for the females who were having any nocturnal orgasms (the active median frequencies) remained quite constant, at something below 0.1 per week for all groups, including the single, married, and previously married females (Table 43 , Figure 22 ). Marital experience had evidently developed the imaginative capacities of some females who had not had sex dreams before marriage, and of a still larger number of those who had become widowed, separated, or divorced; but even the greatly increased experience which regular coitus had provided had not succeeded in increasing the frequencies of the nocturnal fantasies for the average (median) female.

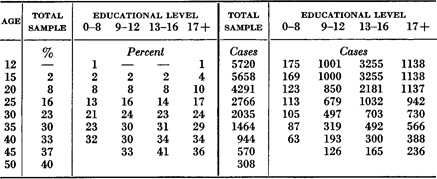

Relation to Educational Level . In the available sample, there seems to have been no correlation between the educational background of the female and the accumulative or active incidence of her nocturnal sex dreams (Tables 42 , 44 ), or the frequency with which she had such dreams to the point of orgasm. Similarly, the portion of the total outlet which she had derived from her nocturnal orgasms did not seem to have been related to the female’s educational level (Table 44 ).

The educational background of the male does seem to have a direct effect on the frequencies of his nocturnal emissions. The males who go furthest in their educational careers appear to have better developed imaginative capacities, and this seems to have an effect upon the development of their psychosexual responses. Unmarried males of the college level have nocturnal sex dreams with frequencies (medians) which are between three and four times those of the males who never go beyond grade school (see our 1948:342); but females who have college and graduate school training do not have sex dreams any more frequently than those who have not gone beyond grade school or high school.

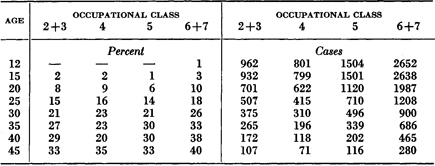

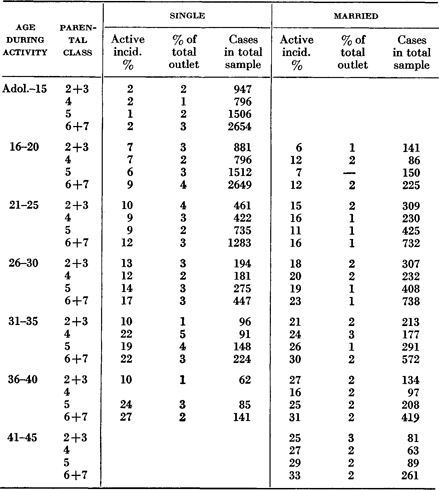

Relation to Parental Occupational Class . There seems to be little correlation between the social levels of the homes in which the girls in our sample were raised, and the incidences and frequencies with which they ultimately had nocturnal dreams to the point of orgasm (Tables 45 , 47 ).

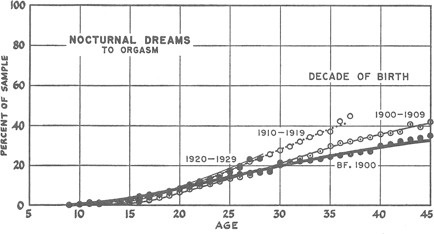

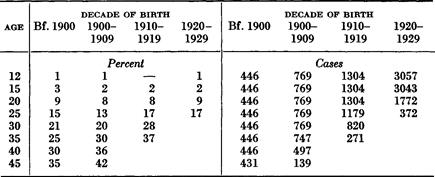

Figure 24. Accumulative incidence: nocturnal dreams to orgasm, by decade of birth

Data from Table 46 .

Relation to Decade of Birth . In our sample, the number of teen-age females of the recent generations who were dreaming to the point of orgasm (both the accumulative and active incidences) was about what it had been among those who were born forty years earlier (Tables 46 , 48 , Figure 24 ). After the early twenties, however, a slightly higher percentage of the females of the younger generation were dreaming to orgasm. But the frequencies were not modified at all in the course of the forty years covered by the sample. If psychosexual development in the female were socially controlled, as it is ordinarily believed to be, we might have expected more change in the incidences and frequencies of nocturnal dreams over this period of years.

Within the last forty years the place of the female in our social organization has materially changed. Her position in the home has been considerably modified, her place in industry and in the business affairs of the nation has developed to an extent which was unimagined forty years ago, she has acquired some position in the political control of the nation, and become active in civic, state, and national affairs to an extent which her grandmother never anticipated. Forty years ago there were only about 7 per cent of the females who ever went to college, but the present generation is sending about 15 per cent of its girls into collegiate work. 18 The proportion who go on into graduate work and into professional programs has increased to an even greater extent. Even among those who do not go to college, the number of years of schooling has, on an average, tremendously increased: forty years ago there were two-thirds (67 per cent) who never got beyond grade school, today there are only 18 to 20 per cent who go no further than that in their schooling. 18 There has been a similarly marked change in the number who complete high school. In spite of this, the number of females who are ever stimulated by daytime fantasies (Chapter 5 ) or by sex dreams as they sleep, and the frequencies with which they have such dreams to the point of orgasm, remain just about what they were in their grandmothers’ generation. The capacity to be aroused psychosexually evidently depends on something more innate than the culture (Chapters 16 , 18 ). In the female, and not improbably in the male, there appears to be a limit beyond which psychosexual capacities cannot be developed within an individual’s lifetime.

Relation to Age at Onset of Adolescence . There seems to have been no consistent correlation between the ages at which the females in the sample had turned adolescent, and their involvement in nocturnal dreams (the accumulative and active incidence figures), or the frequencies with which they had them (the active median and mean frequencies) (Tables 49 , 52 ).

Relation to Rural-Urban Background . In the groups on which the data are available, there are some differences between the incidences of nocturnal dreams among the females who were raised in rural areas and those who were raised in urban areas (Tables 50 , 51 ). However, none of these differences seem to lie in any constant direction, and we are inclined to credit them to the vagaries of sampling, or to the small sizes of some of the samples.

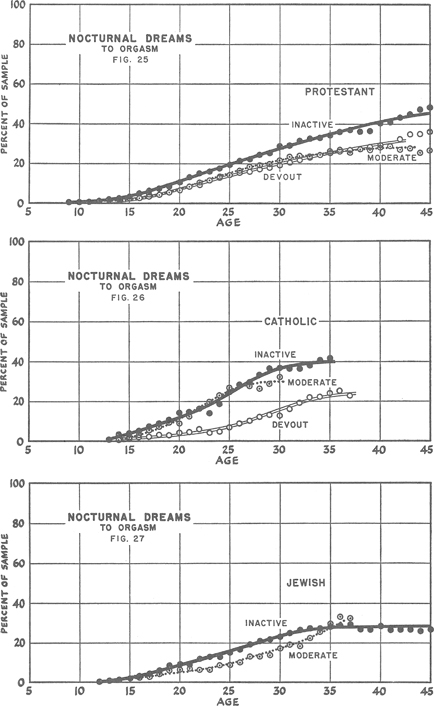

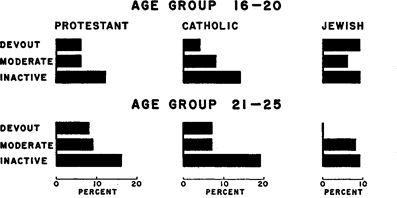

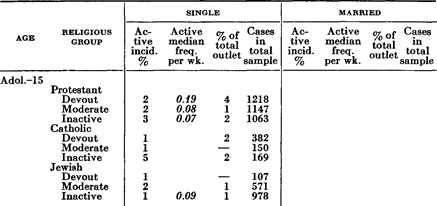

Relation to Religious Background . The number of females in the sample who had ever experienced nocturnal dreams to the point of orgasm (the accumulative incidence), and the number who were having such experience within any five-year period (the active incidence), did seem to have been affected by the degree of their religious devotion (Tables 53 , 54 , Figures 25 –28 ). The differences were not dependent on their Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish backgrounds, but upon the degree of their devotion in their religion. In general, fewer of the females who were active or devout religiously had dreamed to the point of orgasm-perhaps because they had had the smallest amount of overt sexual experience about which they could dream.

Figures 25-27. Accumulative incidence: nocturnal dreams to orgasm, by religious group

Data from Table 53 .

On the other hand, the frequencies with which the females had had dreams after they had once started them did not seem to be affected by the religious background (Table 54 ). It will be recalled that we found a similar situation in regard to the masturbatory frequencies of the females in the sample (Chapter 5 ). It is difficult to understand why a religious background which has kept a female from dreaming of sex for some period of years does not continue to influence her after she has begun to have sex dreams.

Figure 28. Active incidence: nocturnal dreams to orgasm, by religious group

Data on single females; see Table 54.

Nocturnal sex dreams carried to the point of orgasm appear to provide some physiologic outlet, albeit never more than a minor outlet, for about a third of the females (Table 43 ). 19

Nocturnal dreams had accounted for approximately 2 to 3 per cent of the total number of orgasms experienced by the females in the total sample, including both the single and married females of most of the age groups (Table 170 , Figure 109 ). The figure was low, in part because there were three-quarters or more of the females in each age group who were not having any nocturnal orgasms, and in part because the frequencies were always low.

Nocturnal dreams had provided only 2 per cent of the total outlet of the younger single females in the sample and 4 per cent of the total outlet of the unmarried older females (Table 171 , Figure 110 ). Except for animal contacts, nocturnal dreams were, therefore, the least important of all the sources of outlet for the single females of every group under forty-five years of age. As sources of physiologic release for single females, they were surpassed in importance by masturbation, heterosexual petting, pre-marital coitus, and, especially in older groups, by homosexual contacts.

Among younger married females, the orgasms obtained through nocturnal dreams had accounted for only 1 per cent of the total sexual outlet (Table 171 , Figure 111 ). However, the relative importance of the dreams had gradually increased as coital activities slowed up with advancing age, and the dreams had finally accounted for about 3 per cent of the outlet of the married females in their late forties. Animal contacts and homosexual relations were the least important sexual activities of the married females in all of the age groups, but nocturnal dreams were the next least important. Marital coitus, masturbation, and extra-marital coitus had provided larger proportions of the outlet for the married females.

In the histories of the females who had been previously married, and who in consequence had had their chief source of outlet, marital coitus, more or less suddenly withdrawn, orgasms derived from nocturnal dreams had accounted for a more significant part of the total picture. Among the younger females in the sample who had been previously married, and who were now widowed, separated, or divorced, the dreams had accounted for 4 or 5 per cent of the total number of orgasms. Among the older females who had been previously married, the dreams had accounted for as much as 14 per cent of the total outlet (Tables 43 , 171 , Figure 112 ).

None of these differences in the proportions of the total outlet derived from dreams were, however, the product of any variation in the frequencies of the dreams themselves. From the youngest to the oldest age groups, the frequencies (the active median frequencies) of the dreams of the single, married, and previously married females who were having any dreams at all were quite uniform. The variations in the proportions of the total outlet which were derived from dreams had depended primarily on the fact that the frequencies of petting, coitus, and homosexual relations varied in different age and marital groups. These other outlets were the ones in which other persons, the sexual partners of the female, had played a predominant role in determining the frequencies of contact. But the frequencies of the nocturnal dreams, which seem a better measure of the female’s innate sexuality, had not changed in the long span of years between adolescence and fifty, or under any of the various social conditions imposed by marriage, education, rural-urban backgrounds, religion, and other factors.

There is a longstanding and widespread opinion that nocturnal orgasms provide a “natural” outlet for persons who abstain from other types of sexual activity. The frequencies of the dreams are supposed to have an inverse relation to the frequencies of other sexual activities, thus providing a safety valve for the “sexual energy” which accumulates when other outlets are unavailable or are not being utilized. Some authors, for instance, assert that orgasms in sleep occur only among unmarried virgins, or among married females when orgasm has not been reached in coitus, or when spouses are separated, or when marital coitus is for any other reason not available. 20

The theory has considerable moral importance, for it recognizes nocturnal dreams as an acceptable form of sexual outlet—the only acceptable form outside of vaginal coitus. In both Jewish and Catholic codes, vaginal coitus in marriage, and such preliminary play as will lead to vaginal coitus, is considered the natural means of fulfilling what is taken to be the prime function of sex, namely procreation. Because other forms of sexual activity do not serve this procreative function, none of them except nocturnal dreaming to orgasm is morally acceptable. Orgasm resulting from nocturnal sex dreams is allowed as an exception because, if it is not deliberately induced, it is involuntary and a “natural” sort of “compensation” for the abstinence. The Catholic code, however, is precise in its condemnation of nocturnal orgasms which have been deliberately induced. 21

The belief that nocturnal dreams are compensatory carries the promise that undue physiologic tensions will be relieved if an individual remains abstinent. For those who accept the theory as an established fact, it is then possible to contend that there are no biologic or medical reasons which should make it impossible for anyone, female or male, to remain completely abstinent and chaste before marriage. But the compensatory function of nocturnal dreaming to orgasm has, as far as we have been able to discover, never been established by scientifically adequate data. If there are persons who, being abstinent, have specific records to contribute on this subject, it would be of considerable scientific and social value to have them made available for scientific study.

The moral significance of nocturnal sex dreams has most frequently been considered in connection with the male, but the principle has, on occasion, been extended to the female. Hammer, 20 for instance, asserts that the female who is deprived of other sexual outlets will find relief in nocturnal orgasms once every third day. Mantegazza, 20 however, says once in four or five days. No data are presented, and apparently the very positiveness of these statements is supposed to guarantee that they are based on specific evidence.

Because of the importance of this concept of a compensatory function served by nocturnal orgasms, we have gone to some pains to analyze the data on our total sample of 7789 females. From these analyses the following generalizations may be drawn:

1. Out of our total sample of 7789 females, including both Negro and white and both prison and non-prison cases, there are 1761 females who had dreamed at some time in their lives to the point of orgasm. However, only 251 of these cases, which is 14 per cent of all of those who had ever had nocturnal orgasms, seem to show a compensatory relationship between the dreams and the other outlets.

2. Such compensatory relationships seem to occur most frequently when other sexual outlets are drastically reduced or eliminated. When the female has not previously had nocturnal dreams, she may have them after the reduction of the other outlets. This was true in approximately 200 of our cases. When the female had previously had dreams, the frequencies may increase when the normal outlets are eliminated or reduced. This may occur, for instance, when divorce or separation from a spouse eliminates the coital sources on which the individual has been chiefly dependent (p. 536). Clear-cut cases also occur when a woman is committed to prison, which in most instances is synonymous with depriving her of the opportunity to have any regular sexual outlet. Out of our 208 prison cases of females who had ever in their lives had sex dreams to orgasm, 140 (68 per cent) showed marked changes in the incidences or frequencies of nocturnal sex dreams to orgasm after commitment to the penal institution. The specific data are as follows:

| Percent | |

| Nocturnal sex dreams only while in prison | 62 |

| Nocturnal sex dreams began in prison, continued outside | 6 |

| Nocturnal sex dreams increased while in prison | 23 |

| Nocturnal sex dreams decreased or stopped in prison | 9 |

| Number of cases | 140 |

3. Nocturnal orgasms seemed to occur, or increased in frequency, when socio-sexual outlets (as opposed to solitary outlets) were reduced or proved inadequate. The specific cases include instances of dreams which began only when petting, coitus, or homosexual outlets were eliminated or materially reduced in frequency. There are instances of nocturnal orgasms occurring after petting, or after premarital or marital coitus which had failed to bring the female to orgasm. Such cases, however, are not sufficiently frequent to warrant any statistical treatment here.

4. In nearly every instance the compensatory nature of the nocturnal dreams seemed quite inadequate. The increase in the frequencies of the nocturnal orgasms is usually not more than a few per year, although the outlets for which they were supposed to be compensating may have averaged several times per week.

5. In contrast to this group of cases in which the nocturnal experience seems to serve a compensatory function, there are’ some 117 cases (7 per cent of the 1761 females who had ever experienced nocturnal orgasms) in which the nocturnal orgasms seemed to correlate positively with the occurrence of other sexual outlets. Nocturnal dreams seem to have occurred only when these individuals were most often involved in other types of sexual activity, or the dreams increased under such conditions (see our 1948:529). Instances of this are to be seen in the fact that the married females (in the same age groups) have higher rates of dreams than the single females.

6. For 183 females (10 per cent of the 1761 females who had ever experienced nocturnal orgasms), the nocturnal orgasms started in the same year that one or more of the other types of sexual activity had begun.

| % of females | |

| Nocturnal dreams began when masturbation began | 33 |

| Nocturnal dreams began when petting began | 34 |

| Nocturnal dreams began when coitus began | 48 |

| Nocturnal dreams began when homosexual contacts began | 8 |

| Number of cases | 183 |

7. In some instances nocturnal orgasms were superimposed on what would seem to have been quite adequate or even high rates of outlet. The most extreme instance was that of a female whose nocturnal orgasms were averaging twice a week, although (because of her ability in multiple orgasm) she was having an average outlet of nearly 70 orgasms per week.

8. In a portion of the cases, there seems to be a positive correlation between high levels of erotic responsiveness and the frequencies of nocturnal dreams to orgasm. For the 74 females in the sample whose nocturnal dreams had averaged at least once a week for at least five consecutive years, the record shows the following:

| Erotic responsiveness | %with nocturnal orgasms |

| Above average | 58 |

| Average | 30 |

| Below average | 12 |

| Orgasmic response in coitus | |

| 100% of contacts | 89 |

| With multiple orgasm (1.5 to 10 times each) | 39 |

That 89 per cent of those with the highest dream frequency had reached orgasm regularly in their coitus, strikingly contrasts with the fact that not more than 47 per cent in any group of married females had ever reached orgasm one hundred per cent of the time, even after twenty years of marriage (Table 112 ). That 39 per cent of those who had most frequently dreamed, experienced multiple orgasm in coitus, similarly contrasts with the fact that only 14 per cent of the total sample had regularly experienced multiple orgasm (p. 375).

9. There is some correlation between the occurrence of masturbation and nocturnal dreams. There is also some correlation between the occurrence of fantasies in masturbation and nocturnal dreams. The data are as follows:

| Masturbation in history | % females with sex dreams | % females without sex dreams |

| With fantasy in masturbation | 35 | 19 |

| Without fantasy in masturbation | 18 | 13 |

| Without masturbation in history | 47 | 68 |

| Number of cases | 3423 | 1859 |

10. There are some individuals whose histories seem to show both compensatory and positive relationships between their nocturnal dreams and their other sexual activities. For instance, there are persons whose dreams began in the same year that coitus began, but when the coital rate was considerably stepped up in marriage, the dreams completely stopped. There are also cases of individuals whose dreams began only when their outlet was considerably increased through marriage, but whose dreams increased in frequency when their husbands were away from home.

It is quite possible that the different factors responsible for nocturnal dreams may operate in diverse ways. It is conceivable that physiologic factors may be responsible for the inverse or negative relationships which we have found. On the other hand, the psychologic factors which affect nocturnal dreams would more often produce positive correlations. This is indicated by the fact that there are cases in which the sexual experience of the previous evening supplies the subject matter of the nocturnal dream, leading to a repetition in sleep of the orgasm which had been had before retiring.

11. For 79 per cent of the 1761 females who had had sex dreams, there do not seem to be any obvious correlations between the occurrence or absence of nocturnal dreams and the magnitude of the total outlet. There are high rates of nocturnal dreams among females who have high rates of outlets from other sources, and similarly high rates of dreams among those who have very low rates of outlet from other sources. There are individuals representing every other level of outlet, who have never had any nocturnal dreams. There are even individuals who give evidence of high psychologic responsiveness in connection with their other sexual activities, who do not have nocturnal dreams. This means that a multiplicity of factors must, in the majority of instances, determine the occurrence or non-occurrence of such nocturnal dreams, and that no single factor or small group of factors may account for their occurrence or non-occurrence in a history. What the present data do seem to show may be summed up as follows:

| Relation Between Nocturnal Dreams and Other Sexual Outlets | |

| % | |

| Inverse or compensatory relationship | 14 |

| Positive or parallel relationship | 7 |

| No marked relationship (among females with dream experience) | 79 |

| Number of cases with nocturnal dreams | 1761 |

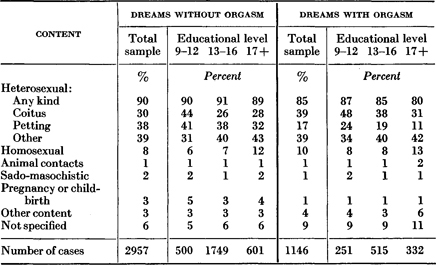

About one per cent of the females in the sample reported nocturnal orgasms without dreams (Table 41 ). 22 Of the females who had had sex dreams, whether with or without orgasm, something between 85 and 90 per cent had had heterosexual dreams (Table 55 ). This closely matched the extent of the overt heterosexual activity in the same histories. Between 30 and 39 per cent of the females had dreamed, at least on occasion, of actual coitus, 23 while 17 to 38 per cent had dreamed on occasion of heterosexual petting which did not involve coitus. 24

The sexual partners in these dreams were usually obscure and unidentifiable—an epitomization of some general type of person 25 ; and even the actor in the dream was not always the dreamer, but a person who combined the capacities of an observer and a participant in the activity. More precise data are needed on this matter. Many of the heterosexual dreams had an indefinitely affectionate or generally social content which did not include overtly physical contacts. While such dreams may in actuality be sexual in significance, they are quite different from the overtly sexual dreams which males usually have.

Some 8 to 10 per cent of the females having dreams had had homosexual dreams (Table 55 ). 26 This again, was very close to the number who had had overt homosexual experience. There were dreams of pregnancies resulting from the homosexual relations. 27

About 1 per cent of the females had dreamed of sexual relations with animals of other species. About 1.5 per cent had dreamed of sadomasochistic situations. Various other types of sex dreams had occurred in still other cases (Table 55 ).

Something between 1 and 3 per cent of the females had dreamed that they were pregnant or that they were giving birth to a child (Table 55 ). It is notable that these were reported as “sex dreams.” For nine out of every ten of the females who had had such dreams, the dreams had not led to orgasm. Such dreams need further consideration, because the connection between the reproductive function and erotic arousal is probably not as well established as biologists and psychologists ordinarily assume. By association, many males and apparently some females may become erotically aroused when they contemplate any reproductive or excretory function, probably because it depends at least in part on genital anatomy, and this may explain why some females consider dreams of pregnancy as sexual. It is more likely they consider their pregnancy dreams as sexual simply because they know, intellectually, that there is a relationship between sexual behavior and reproduction. There are still other possible explanations in psychiatric theory.

Sex dreams, whether they occur in the female or the male, are often a reflection of experience which the individual has actually had. On the other hand, some 13’ per cent of the females in the sample (Negro and white) who had ever dreamed, had had sex dreams which went beyond their actual experience. 28 The specific record is as follows:

| Dream Content Without Overt Experience | |||

| WITHOUT ORGASM | WITH ORGASM | WITH ANY DREAM | |

| Dreams of coitus (not rape) | 36 | 10 | 46 |

| Dreams of rape | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Dreams of petting | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Dreams of homosexual contacts | 16 | 7 | 23 |

| Dreams of animal contacts | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Sado-masochistic dreams | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Dreams of pregnancy and childbirth | 13 | 2 | 15 |

| Number of females whose dreams precede experience | 622 | ||

The dreams which antedate experience may represent some desire to participate in an activity which has not yet been accepted in actual life, or which the female has not yet had the opportunity to engage in, or which she would always avoid in overt relationships. Freud and other psychoanalysts believe that the dream content is often a record of repressed desires. 29 Not a few individuals derive considerable pleasure from vicariously participating, through these dreams, in activities which, for one reason or another, are ’unattainable in actual life.

On the other hand, some of these dreams represent activities, like rape, which the individual may not desire and of which she may actually be afraid. It seems reasonable to believe that some of these dreams are nightmares rather than anything which the females would welcome either in or out of sleep.

The records which we have in the present study do not provide any original data for a discussion of the sexual symbolism of dreams.

The great majority of the females in the sample had accepted their nocturnal sex dreams without any disturbance. A smaller percentage had worried about the moral significance of their sex dreams. However, fewer females than males ever worry over their dreams, probably because some males are disturbed by their seminal emissions. In most instances the females had taken their experience as pleasurable, and had attached little other importance to it. 30

Table 42. Accumulative Incidence: Dreams to Orgasm

By Educational Level

Table based on total sample, including single, married and previously married females.

Table 43. Active Incidence, Frequency, and Percentage of Outlet Dreams to Orgasm

By Age and Marital Status

Italic figures throughout the series of tables indicate that the calculations are based on less than 50 cases. No calculations are based on less than 11 cases. The dash (–) indicates a percentage or frequency smaller than any quantity which would be shown by a figure in the given number of decimal places.

Table 45. Accumulative Incidence: Dreams to Orgasm

By Parental Occupational Class

The occupational classes are as follows: 2 + 3 = unskilled and semi-skilled labor. 4 = skilled labor. 5 = lower white collar class. 6 + 7 = upper white collar and professional classes.

Table based on total sample, including single, married, and previously married females.

Table 46. Accumulative Incidence: Dreams to Orgasm

By Decade of Birth

Total based on total sample, including single, married, and previously married females.

Table 47. Active Incidence and Percentage of Outlet: Dreams to Orgasm

By Parental Occupational Class and Marital Status

The occupational classes are as follows: 2 + 3 = unskilled and semi-skilled labor. 4 = skilled labor. 5 = lower white collar class. 6 + 7 = upper white collar and professional classes.

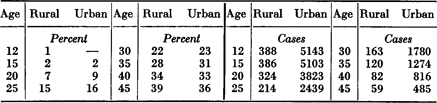

Table 50. Accumulative Incidence: Dreams to Orgasm

By Rural-Urban Background

Table based on total sample, including single, married, and previously married females.

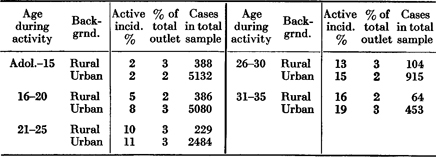

Table 51. Active Incidence and Percentage of Outlet: Dreams to Orgasm

By Rural-Urban Background

Table based on single females only.

Table 54. Active Incidence, Frequency, and Percentage of Outlet: Dreams to Orgasm

By Religious Background and Marital Status

Table 55. Content of Nocturnal Sex Dreams Percentage with experience prior to interview

The totals of the various types of dreams always exceed 100 per cent because some individuals dream of more than one type of experience. Some individuals appear in both portions of the table, dreaming sometimes with and sometimes without orgasm.

1 The term is generally used for all sex dreams in sleep, whether they occur in sleep at night or in sleep during the daytime.

2 This projection of the male’s hope that the female is dreaming of him is found as far back as Ovid in the first century B.C. See: Ovid: Heroides, 15: 123–134; 19:55–66 (1921:188–190, 262–264).

3 The existence of sex dreams in the human female has been recognized, however, in: Aristotle and Galen ace. Havelock Ellis 1936(1,1) :199. Longus [Greek, 3rd cent. A.D. ?]: Daphnis and Chloe, 1896:41; 1916:83 (“what they had not done in the day, they did in a dream”). Anon., The Fifteen Plagues of a Maiden-head, 1707:4, 6 (“as e’er I’m sleeping in my Bed, I dream I’m mingling with some Man my Thighs…. For dreams … at the present quench my Lechery.” And, “Fancy some Gallant brings to my Arms … till breathless, faint, and softly sunk away, I all dissolved in reaking Pleasures lay”). Tissot 1785:233–234 (cites 2 cases). Guibout (1847) ace. Ellis 1936(1,1): 199 (an early French account). Roland 1864: 66–69 (a diary account of preadolescent dreams with orgasm). Rosenthal (1875) ace. Kisch 1907:376 (probably the earliest medical discussion of sex dreams in women). Nelson 1888:390–391, 401. Kisch 1907. Rohleder 1907(1). Bloch 1908. Nystrom 1908:20. Moll 1909, 1912. Adler J.911. Talmey 1915:246. Hirschfeld 1920. Robie 1925. Marcuse in Moll 1926(2). Blanchard and Manasses 1930. Kelly 1930. Childers 1936:446 (Negro and white children). Ellis 1936(1,1):187–204 (the most detailed discussion of the psychologic aspects of nocturnal sex dreams among females). Stokes 1948. Ford and Beach 1951. Also see the other authors cited throughout the present chapter.

4 Among the few studies which have included specific data on sex dreams among females, note the following: Heyn 1924:60–69 (452 women interviewed in a medical clinic in Germany). Hamilton 1929:313–320 (the most detailed investigation, with material on 100 married women, in 13 tables. The percentages cited here are recalculated from these tables, in order to make them comparable to the present data). But no investigation of such dreams was covered in such important studies of the female as: Davis 1929, Dickinson and Beam 1931, Dickinson and Beam 1934, Landis et al. 1940, and Landis and Bolles 1942.

5 Muscular movements in nocturnal orgasm are also noted in: Krafft-Ebing and Kisch acc. to Rohleder 1907 (1) :231. Heyn 1924:60–64.

6 The inclusion of things in dreams which are not accepted when awake is elaborately discussed in Freud 1938:208 ff., and noted in Hamilton 1929:317–318, and Havelock Ellis 1936 1,1): 195–196.

7 The occurrence of orgasm in the nocturnal dreams of the female, before it occurs in any other sort of experience, is also noted in: Kisch 1907:576–577. Moll 1909:86; 1912:95. Heyn 1924:62–63. Robie 1925:205. Blanchard and Manasses 1930:32. Havelock Ellis 1936(1,1) :197. Stekel 1950:158–159. See p. 213.

8 Male paraplegics (Chapter 17 ) whose spinal cords have been severed may have nocturnal sex dreams and sometimes ejaculate. See: Shelden and Bors 1948: 388. Talbot 1949:266. Bars, Engle, Rosenquist, and Holliger 1950:393. In such paraplegics, psychologic stimulation of the genital area is impossible. Because of this, Ford and Beach 1951:164 state, “It seems more probable that sexual dreams associated with genital reflexes are a product of sensations arising in the tumescent phallus.” With this interpretation we do not wholly agree. While the data from the paraplegics show that orgasm during sleep may be induced by physical stimulation alone, they do not disprove our contention that psychologic fantasies are; in the intact individual, the primary sources of the nocturnal responses.

9 Instances of this opinion that accumulated pressures in various structures are responsible for nocturnal sex dreams in the male (and, by a parallelism, in the female) may be found in: Loewenfeld 1908:598 (discusses a hypothetic increase of arousability of the cortical sex centers determined by an accumulation of libido-genic matters in the blood). Hammer ace. Heyn 1924:61 (a discharge from over-strained mucous glands). Rice 1933:39, 41. Kahn 1939: 26. The erotic literature consistently refers to pressures in the testes. ,

10 The opinion that females who have sex dreams are neurotic is expressed in: Kisch 1907:576. Krafft-Ebing acc. Kisch 1907:377. Loewenfeld 1908:596. Bloch 1908:439–440 (includes older references). Krafft-Ebing acc. Heyn 1924:60. Heyn 1924:63 objects to this neurotic interpretation.

11 Nocturnal dreams among the males of lower mammals are reported in Ford and Beach 1951: 165 for the cat (with ejaculation) and for the shrew (with erection only). We have observed erection in male dogs while they slept. From one of our subjects we have a clear-cut record of sex dreams in a female boxer dog. During periods of heat, the dog regularly showed signs of sexual disturbance while asleep, with body movements, vocalization, vaginal swellings, and the development of vaginal mucous secretions. Dr. Karl Lashley tells us of a female dachshund whining, making pelvic thrusts, and showing genital tumescence in sleep during periods of estrus.

12 Nocturnal dreams among females of primitive peoples (in every instance without any record of orgasm) are reported in: Crawley 1927(1) :233 (for the Yoruba in Africa). Malinowski 1929:339-340, 392 (for the Trobrianders in Melanesia). Blackwood 1935:549, 552, 559 (18 of 177 recorded dreams were sexual, among the Melanesians of Bougainville). Havelock Ellis 1936(1,1): 199 (for the Hindu and Papua). Devereux 1936:32, 57 (for the Mohave Indians). Gorer 1938:185 (for the Lepcha). Laubscher 1938:10 (for the Tembu in South Africa). DuBois 1944:45, 69-70 (for the Alor in Melanesia). Elwin 1947:480 (for the Muria in India). Ford and Beach 1951:165 (give no cases; state it is rare in anthropologic literature).

13 Dreams stopping short of orgasm are also noted in: Heyn 1924:65. Marcuse in Moll1926(2):861 (in specifically neurotic females).

14 Incidences of dreams to orgasm in the female are also reported in: Schbankov ace. Weissenberg 1924a:9 (in 12 per cent of 324 female Russian students). Heyn 1924:61 (about 50 per cent, slightly fewer in virgins). Hamilton 1929: 313 (37 per cent). Incidences are discussed, without specific data, in: Loewenfeld 1908:588. Eberhard 1924:263. Stokes 1948:18 (less frequent among females than males) .

15 Additional data on the frequencies of nocturnal orgasms may be found in Loewenfeld 1908:596 (individual variation). Heyn 1924:61-62 (frequency higher in females with “stronger sex drive”). Hamilton 1929:315-.316 (12 out of 15 single females had frequencies of 3 per year or less. Of 41 females, 56 per cent had dreams only after marriage, 34 per cent had them both before and after marriage, and 10 per cent had them only before marriage).

16 Exceptional frequencies of more than one per night are also noted by: Stekel 1923:81; 1950:159. Heyn 1924:64. Hamilton 1929:315.

17 For correlations of nocturnal dreams with the age of the female, see also: Havelock Ellis and Moll in Moll 1911 1921:614 (less commonly in the female, more often in the male during adolescence). Heyn 1924:63 (an occasional instance before first menstruation). Hamilton 1929:313, 320 (says 2 per cent by age 16, has 1 case before first menstruation; 21 out of 40 married women who had experienced sex dreams, had them more frequently in later marriage).

18 These data on educational attainment in the U. S. population are approximated from the Sixteenth Census of the U. S., 1940 (Population v. 4, pt. 1, U. S. Summary) 1943:79.

19 That dreams provide some physiologic release is also noted in Heyn 1924:64 ff.

20 As examples of this concept of a compensatory function in the female’s nocturnal sex dreams, see: Rohleder 1907(1):231. Kisch 1907:576-577 (dreams when frigid in coitus). Loewenfeld 1908:596 (dreams correlated with high erotic responsiveness). Adler 1911:129. Hammer and Mantegazza ace. Heyn 1924: 60-61. Heyn 1924:62-63, 69 et passim (dreams correlated with high erotic responsiveness). Krafft-Ebing 1924:97. Marcuse in Moll 1926(2):861 (dreams because of cultural restraints on other outlets). Moll 1926 (2) :1076. Hamilton 1929:320 (of 42 females, 52 per cent found their dreams compensatory). Dickinson and Beam 1931:185, 285 (as a substitute for unsatisfactory coitus).

21 The Catholic viewpoint on nocturnal dreams to orgasm is this: Such dreams are without fault or sin provided (1) they are not deliberately induced by thought or deed; (2) they are not consciously welcomed and enjoyed. See the following: Arregui 1927:6 (item 8, no. 3), 151 (item 257, no. 1, 2), who says: Pollution in sleep, following from improper thought, since it no longer belongs to the free will, is not in itself imputed to sin, but the placing of the cause from which it was foreseen to be about to follow is imputed to sin. Nocturnal pollution which is not at all voluntary, is free from all fault, although it pleases the one sleeping. To promote the dreams by touch, movement, etc., is grave …. not positively to hinder it is no sin provided the danger of consent be lacking. Pollution caused in sleep by chaste conversation held on the day before with a person of the opposite sex, by strongly seasoned foods, by liquors, or by a rather suitable position on the bed, is not imputed to sin, even though it was foreseen, provided, however, that it was not intended or, once having arisen, deliberately admitted.

Davis 1946(2):243, 246, says: Since pollution directly voluntary is a grave sin, it is not permitted even for the purpose of recovering health or for relieving pain, or for calming or destroying the temptations of the flesh…. nor is it permitted to give consent to it even though the ejaculation has arisen naturally. Nor is it permitted to release it, already begun, by completing any positive act. But indeed it is not a grave sin to hold oneself passively if no consent be given. Hence, respectable dancing, reasonable sport, moderate eating and drinking, kisses and embraces according to the custom of the country among those engaged and among friends are permitted, even though pollution may follow, be foreseen or permitted, but in no way intended, nor while it is going on considered as pleasing and welcome.

The Jewish interpretation is typified by the statement in Leviticus 15:15-16, that nocturnal emissions make one unclean, and one must wash and be unclean until the evening.

22 Nocturnal orgasms without the recall of dreams are also noted by: Heyn 1924: 64. Hamilton 1929:315. Confusion of the dream with reality, especially in the female, is stressed in: Havelock Ellis and Moll in Moll1911, 1921:615. Havelock Ellis 1936(1,1) :200–205.

23 Hamilton 1929:314-315 says 22 per cent of first dreams were of coitus. Our data range from 26 to 48 per cent in various groups.

24 Petting in the dream content is also noted in: Heyn 1924:64. Hamilton 1929:314 (records only a few cases).

25 That the dream partner is not the real lover and is often unidentified, is also noted in: Heyn 1924:64. Krafft-Ebing 1924:98 (no concrete persons). Hamilton 1929:318–319 (identifiable partner in about 50 per cent).

26 Homosexual content of the dreams is also noted in: Krafft-Ebing 1901:28–27. Hirschfeld 1920:73, 317. Heyn 1924:65. Moraglia in Heyn 1924:65. Hamilton 1929:317. Kelly 1930:136.

27 Dreams of pregnancies resulting from homosexual contacts are also noted in Hirschfeld 1920:74. This is what the Negro vernacular identifies as a jelly baby .

28 The relation of the dreams to actual experience or the lack of experience is discussed in: Havelock Ellis and Moll in Moll 1911, 1921:615. Kelly 1930:163 (dreams can occur in inexperienced girls, but are more common in older women with masturbatory or coital experience). Dickinson and Beam 1934: 136. The following authors deny (incorrectly) that virgins are capable of reaching orgasm in nocturnal dreams: Rohleder 1907(1):231; 1918(1):135. Adler 1911:129. Loewenfeld 1911b:16L Reisinger 1916:344. Kahn 1937:346; 1939:404.

29 The Freudian opinion on the nature of nocturnal dreams is summarized, for instance, in Freud 1935:116, 120; 1949:48 (dreams are sometimes an unconscious wish-fulfillment, sometimes represent unsatisfied conscious desires, but “the satisfaction in a pollution-dream can be real”). Heterosexual dreams among males who are completely homosexual are noted in Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin 1948:526–527.

30 The wide acceptance by females of sex dreams without worry is also noted in: Heyn 1924:66. Hamilton 1929:316 (says 19 per cent worry).