The classification of sexual behavior as masturbatory, heterosexual, or homosexual is based upon the nature of the stimulus which initiates the behavior. The present chapter, dealing with the homosexual behavior of the females in our sample, records the sexual responses which they had made to other females, and the overt contacts which they had had with other females in the course of their sexual histories.

The term homosexual comes from the Greek prefix homo , referring to the sameness of the individuals involved, and not from the Latin word homo which means man. It contrasts with the term heterosexual which refers to responses or contacts between individuals of different (hetero ) sexes.

While the term homosexual is quite regularly applied by clinicians and by the public at large to relations between males, there is a growing tendency to refer to sexual relationships between females as lesbian or sapphic . Both of these terms reflect the homosexual history of Sappho who lived on the Isle of Lesbos in ancient Greece. While there is some advantage in having a terminology which distinguishes homosexual relations which occur between females from those which occur between males, there is a distinct disadvantage in using a terminology which suggests that there are fundamental differences between the homosexual responses and activities of females and of males.

It cannot be too frequently emphasized that the behavior of any animal must depend upon the nature of the stimulus which it meets, its anatomic and physiologic capacities, and its background of previous experience. Unless it has been conditioned by previous experience, an animal should respond identically to identical stimuli, whether they emanate from some part of its own body, from another individual of the same sex, or from an individual of the opposite sex.

The classification of sexual behavior as masturbatory, heterosexual, or homosexual is, therefore, unfortunate if it suggests that three different types of responses are involved, or suggests that only different types of persons seek out or accept each kind of sexual activity. There is nothing known in the anatomy or physiology of sexual response and orgasm which distinguishes masturbatory, heterosexual, or homosexual reactions (Chapters 14-15). The terms are of value only because they describe the source of the sexual stimulation, and they should not be taken as descriptions of the individuals who respond to the various stimuli. It would clarify our thinking if the terms could be dropped completely out of our vocabulary, for then socio-sexual behavior could be described as activity between a female and a male, or between two females, or between two males, and this would constitute a more objective record of the fact. For the present, however, we shall have to use the term homosexual in something of its standard meaning, except that we shall use it primarily to describe sexual relationships , and shall prefer not to use it to describe the individuals who were involved in those relationships.

The inherent physiologic capacity of an animal to respond to any sufficient stimulus seems, then, the basic explanation of the fact that some individuals respond to stimuli originating in other individuals of their own sex—and it appears to indicate that every individual could so respond if the opportunity offered and one were not conditioned against making such responses. There is no need of hypothesizing peculiar hormonal factors that make certain individuals especially liable to engage in homosexual activity, and we know of no data which prove the existence of such hormonal factors (p. 758). There are no sufficient data to show that specific hereditary factors are involved. Theories of childhood attachments to one or the other parent, theories of fixation at some infantile level of sexual development, interpretations of homosexuality as neurotic or psychopathic behavior or moral degeneracy, and other philosophic interpretations are not supported by scientific research, and are contrary to the specific data on our series of female and male histories. The data indicate that the factors leading to homosexual behavior are (1) the basic physiologic capacity of every mammal to respond to any sufficient stimulus; (2) the accident which leads an individual into his or her first sexual experience with a person of the same sex; (3) the conditioning effects of such experience; and (4) the indirect but powerful conditioning which the opinions of other persons and the social codes may have on an individual’s decision to accept or reject this type of sexual contact. 1

The impression that infra-human mammals more or less confine themselves to heterosexual activities is a distortion of the fact which appears to have originated in a man-made philosophy, rather than in specific observations of mammalian behavior. Biologists and psychologists who have accepted the doctrine that the only natural function of sex is reproduction, have simply ignored the existence of sexual activity which is not reproductive. They have assumed that heterosexual responses are a part of an animal’s innate, “instinctive” equipment, and that all other types of sexual activity represent “perversions” of the “normal instincts.” Such interpretations are, however, mystical. They do not originate in our knowledge of the physiology of sexual response (Chapter 15), and can be maintained only if one assumes that sexual function is in some fashion divorced from the physiologic processes which control other functions of the animal body. It may be true that heterosexual contacts outnumber homosexual contacts in most species of mammals, but it would be hard to demonstrate that this depends upon the “normality” of heterosexual responses, and the “abnormality” of homosexual responses.

In actuality, sexual contacts between individuals of the same sex are known to occur in practically every species of mammal which has been extensively studied. In many species, homosexual contacts may occur with considerable frequency, although never as frequently as heterosexual contacts. Heterosexual contacts occur more frequently because they are facilitated (1) by the greater submissiveness of the female and the greater aggressiveness of the male, and this seems to be a prime factor in determining the roles which the two sexes play in heterosexual relationships; (2) by the more or less similar levels of aggressiveness between individuals of the same sex, which may account for the fact that not all animals will submit to being mounted by individuals of their own sex; (3) by the greater ease of intromission into the female vagina and the greater difficulty of penetrating the male anus; (4) by the lack of intromission when contacts occur between two females, and the consequent lack of those satisfactions which intromission may bring in a heterosexual relationship; (5) by olfactory and other anatomic and physiologic characteristics which differentiate the sexes in certain mammalian species; (6) by the psychologic conditioning which is provided by the more frequently successful heterosexual contacts.

Homosexual contacts in infra-human species of mammals occur among both females and males. Homosexual contacts between females have been observed in such widely separated species as rats, mice, hamsters, guinea pigs, rabbits, porcupines, marten, cattle, antelope, goats, horses, pigs, lions, sheep, monkeys, and chimpanzees. 2 The homosexual contacts between these infra-human females are apparently never completed in the sense that they reach orgasm, but it is not certain how often infra-human females ever reach orgasm in any type of sexual relationship. On the other hand, sexual contacts between males of the lower mammalian species do proceed to the point of orgasm, at least for the male that mounts another male. 3

In some species the homosexual contacts between females may occur as frequently as the homosexual contacts between males. 4 Every farmer who has raised cattle knows, for instance, that cows quite regularly mount cows. He may be less familiar with the fact that bulls mount bulls, but this is because cows are commonly kept together while bulls are not so often kept together in the same pasture.

It is generally believed that females of the infra-human species of mammals are sexually responsive only during the so-called periods of heat, or what is technically referred to as the estrus period. This, however, is not strictly so. The chief effect of estrus seems to be the preparation of the animal to accept the approaches of another animal which tries to mount it. The cows that are mounted in the pasture are those that are in estrus, but the cows that do the mounting are in most instances individuals which are not in estrus (p. 737). 5

Whether sexual relationships among the infra-human species are heterosexual or homosexual appears to depend on the nature of the immediate circumstances and the availability of a partner of one or the other sex. It depends to a lesser degree upon the animal’s previous experience, but no other mammalian species is so affected by its experience as the human animal may be. There is, however, some suggestion, but as yet an insufficient record, that the males among the lower mammalian species are more likely than the females to become conditioned to exclusively homosexual behavior; but even then such exclusive behavior appears to be rare. 6

The mammalian record thus confirms our statement that any animal which is not too strongly conditioned by some special sort of experience is capable of responding to any adequate stimulus. This is what we find in the more uninhibited segments of our own human species, and this is what we find among young children who are not too rigorously restrained in their early sex play. Exclusive preferences and patterns of behavior, heterosexual or homosexual, come only with experience, or as a result of social pressures which tend to force an individual into an exclusive pattern of one or the other sort. Psychologists and psychiatrists, reflecting the mores of the culture in which they have been raised, have spent a good deal of time trying to explain the origins of homosexual activity; but considering the physiology of sexual response and the mammalian backgrounds of human behavior, it is not so difficult to explain why a human animal does a particular thing sexually. It is more difficult to explain why each and every individual is not involved in every type of sexual activity.

In the course of human history, distinctions between the acceptability of heterosexual and of homosexual activities have not been confined to our European and American cultures. Most cultures are less acceptant of homosexual, and more acceptant of heterosexual contacts. There are some which are not particularly disturbed over male homosexual activity, and some which expect and openly condone such behavior among young males before marriage and even to some degree after marriage; but there are no cultures in which homosexual activity among males seems to be more acceptable than heterosexual activity. 7 It is probable that in some Moslem, Buddhist, and other areas male homosexual contacts occur more frequently than they do in our European or American cultures, and in certain age groups they may occur more frequently than heterosexual contacts; but heterosexual relationships are, at least overtly, more acceptable even in those cultures.

Records of male homosexual activity are also common enough among more primitive human groups, but there are fewer records of homosexual activity among females in primitive groups. We find some sixty pre-literate societies from which some female homosexual activity has been reported, but the majority of the reports imply that such activity is rare. There appears to be only one pre-literate group, namely the Mohave Indians of our Southwest, for whom there are records of exclusively homosexual patterns among females. That same group is the only one for which there are reports that female homosexual activity is openly sanctioned. 8 For ten or a dozen groups, there are records of female transvestites—i.e. , anatomic females who dress and assume the position of the male in their social organization—but transvestism and homosexuality are different phenomena, and our data show that only a portion of the transvestites have homosexual histories (p. 679).

There is some question whether the scant record of female homosexuality among pre-literate groups adequately reflects the fact. It may merely reflect the taboos of the European or American anthropologists who accumulated the data, and the fact that they have been notably reticent in inquiring about sexual practices which are not considered “normal” by Judea-Christian standards. Moreover, the informants in the anthropologic studies have usually been males, and they would be less likely to know the extent of female homosexual activities in their cultures. It is, nonetheless, quite possible that such activities are actually limited among the females of these pre-literate groups, possibly because of the wide acceptance of pre-marital heterosexual relationships, and probably because of the social importance of marriage in most primitive groups. 9

As in any other type of sexual situation, there are: (1) individuals who have been erotically aroused by other individuals of the same sex, whether or no they had physical contact with them; (2) individuals who have had physical contacts of a sexual sort with other individuals of the same sex, whether or no they were erotically aroused in those contacts; and (3) individuals who have been aroused to the point of orgasm by their physical contacts with individuals of the same sex. These three types of situations are carefully distinguished in the statistics given here.

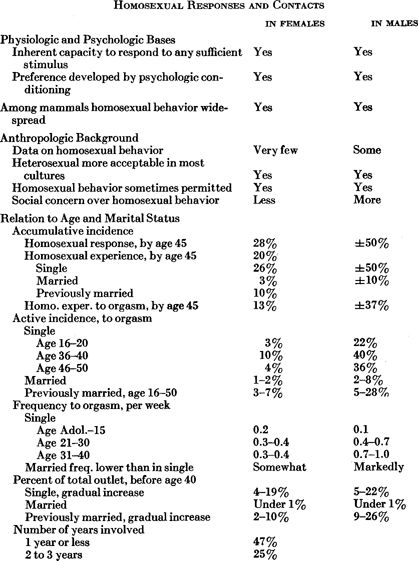

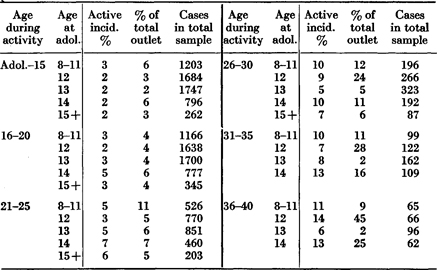

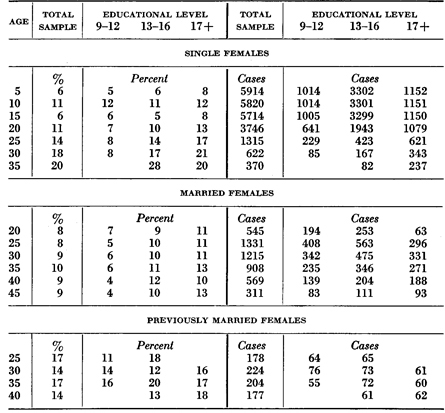

Accumulative Incidence in Total Sample. Some of the females in the sample had been conscious of specifically erotic responses to other females when they were as young as three and four (Table 13 ). The percentages of those who had been erotically aroused had then steadily risen, without any abrupt development, to about thirty years of age. By that time, a quarter (25 per cent) of all the females had recognized erotic responses to other females. The accumulative incidence figures had risen only gradually after age thirty. They had finally reached a level at about 28 per cent (Table 131 , Figure 82 ). 10

The number of females in the sample who had made specifically sexual contacts with other females also rose gradually, again without any abrupt development, from the age of ten to about thirty. By then some 17 per cent of the females had had such experience (Tables 126 , 131 , Figure 82 ). By age forty, 19 per cent of the females in the total sample had had some physical contact with other females which was deliberately and consciously, at least on the part of one of the partners, intended to be sexual. 11

Homosexual activity among the females in the sample had been largely confined to the single females and, to a lesser extent, to previously married females who had been widowed, separated, or divorced. Both the incidences and frequencies were distinctly low among the married females (Table 126 , Figure 83 ). Thus, while the accumulative incidences of homosexual contacts had reached 19 per cent in the total sample by age forty, they were 24 per cent for the females who had never been married by that age, 3 per cent for the married females, and 9 per cent for the previously married females. The age at which the females had married seemed to have had no effect on the pre-marital incidences of homosexual activity, even though we found that the pre-marital heterosexual activities (petting and pre-marital coitus) had been stepped up in anticipation of an approaching marriage. The chief effect of marriage had been to stop the homosexual activities, thereby lowering the active incidences and frequencies in the sample of married females.

A half to two-thirds of the females who had had sexual contacts with other females had reached orgasm in at least some of those contacts. By twenty years of age there were only 4 per cent of the total sample who had experienced orgasm in homosexual relations, and by age thirty-five there were still only 11 per cent with such experience (Table 131 , Figure 82 ). The accumulative incidences finally reached 13 per cent in the middle forties. Since there were differences in the incidences among females of the various educational levels (Table 131 , Figure 85 ), and since our sample includes a disproportionate number of the females of the college and graduate groups where the incidences seem to be higher than in the grade school and high school groups, the figures for this sample are probably higher than those which might be expected in the U.S. population as a whole.

Active Incidence to Orgasm. Since there is every gradation between the casual, non-erotic physical contacts which females regularly make and the contacts which bring some erotic response, it has not been possible to secure active incidence or frequency data on homosexual contacts among the females in the sample except where they led to orgasm. However, comparisons of the accumulative incidence data for experience and for orgasm (Table 131 , Figure 82 ) suggest that the active incidences of the homosexual contacts may, at least in the younger groups, have been nearly twice as high as the active incidences of the contacts which led to orgasm.

In the total sample, not more than 2 to 3 per cent had reached orgasm in their homosexual relations during adolescence and their teens (Table 128 ), although five times that many may have been conscious of homosexual arousal and three times that many may have had physical contacts with other girls which were specifically sexual. After age twenty, the active incidences of the contacts which led to orgasm had gradually increased among the females who were still unmarried, reaching their peak, which was 10 per cent, at age forty. Then they began to drop. Between the ages of forty-six and fifty, about 4 per cent of the still unmarried females were actively involved in homosexual relations that led to orgasm. We do not have complete histories of single females who were reaching orgasm in homosexual relations after fifty years of age, but we do have incomplete information on still older women who were making such contacts with responses to orgasm while they were in their fifties, sixties, and even seventies.

Among the married females, slightly more than 1 per cent had been actively involved in homosexual activities which reached orgasm in each and every age group between sixteen and forty-five (Table 128 ).

On the other hand, among the females who had been previously married and who were then separated, widowed, or divorced, something around 6 per cent were having homosexual contacts which led to orgasm in each of the groups from ages sixteen to thirty-five (Table 128 ). After that some 3 to 4 per cent were involved, but by the middle fifties, only 1 per cent of the previously married females were having contacts which were complete enough to effect orgasm.

Frequency to Orgasm. Among the unmarried females in the sample who had ever experienced orgasm from contacts with other females, the average (active median) frequencies of orgasm among the younger adolescent girls who were having contacts had averaged nearly once in five weeks (about 0.2 per week), and they had increased in frequency among the older females who were not yet married (Table 128 ). In the late twenties they had averaged once in two and a half weeks (0.4 per week), and had stayed on about that level for the next ten years. This means that the active median frequencies of orgasm derived from the homosexual contacts had been higher than the active median frequencies of orgasm derived from nocturnal dreams and from heterosexual petting, and about the same as the active median frequencies of orgasm attained in masturbation. 12

The active mean frequencies were three to six times higher than the active median frequencies, because of the fact that there were some females in each age group whose frequencies were notably higher than those of the median females (Table 128 ). The individual variation had depended in part upon the fact that the frequencies of contact had varied, and in part upon the fact that some of these females had regularly experienced multiple orgasms in their homosexual contacts.

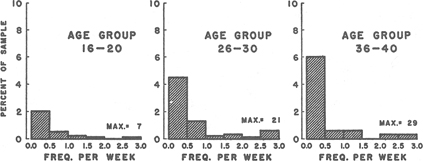

In most age groups, three-quarters or more of the single females who were having homosexual experience to the point of orgasm were having it with average frequencies of once or less per week (Figure 84 ). There were individuals, however, in every age group from adolescence to forty-five, who were having homosexual contacts which had led to orgasm on an average of seven or more per week. From ages twenty-one to forty there were a few individuals who had averaged ten or more and in one instance as many as twenty-nine orgasms per week from homosexual sources. In contrast to the record for most other types of sexual activities, the most extreme variation in the homosexual relationships had not occurred in the youngest groups, but in the groups aged thirty-one to forty.

Figure 84. Individual variation: frequency of homosexual contacts to orgasm

For three age groups of single females. Each class interval includes the upper but not the lower frequency. For incidences of females not having homosexual experience or reaching orgasm in such contacts, see Table 128 .

As in most other types of sexual activity among females (except coitus in marriage), the homosexual contacts had often occurred sporadically. Several contacts might be made within a matter of a few days, and then there might be no such contacts for a matter of weeks or months. In not a few instances the record was one of intense and frequently repeated contacts over a short period of days or weeks, with a lapse of several years before there were any more. On the other hand, there were a fair number of histories in which the homosexual partners had lived together and maintained regular sexual relationships for many years, and in some instances for as long as ten or fifteen years or even longer, and had had sexual contacts with considerable regularity throughout those years. Such long-time homosexual associations are rare among males. A steady association between two females is much more acceptable to our culture and it is, in consequence, a simpler matter for females to continue relationships for some period of years. The extended female associations are, however, also a product of differences in the basic psychology of females and males (Chapter 16 ).

Among the married females in the sample, there were a few in each age group—usually not more than one in a hundred or so—who were having homosexual contacts to the point of orgasm (Table 128 ). Even in those small active samples, however, the range of individual variation was considerable. Most of the married females had never had more than a few such contacts, but in nearly every age group there were married females who were having contacts with regular frequencies of once or twice or more per week. There were a few histories of married females who were completely homosexual and who were not having coitus with their husbands, although they continued to live with them as a matter of social convenience. In some of these cases there were good social adjustments between the spouses even though the sexual lives of each lay outside of the marriage.

Among the females in the sample who had been previously married and who were then widowed, separated, or divorced, the frequencies of homosexual experience were distinctly higher than among the married females (Table 128 ). In some cases these females, after the dissolution of their marriages, had established homes with other women with whom they had then had their first homosexual contacts and with whom they subsequently maintained regular homosexual relationships. Some of the women had been divorced because of their homosexual interests, although homosexuality in the female is only rarely a factor in divorce. It should be emphasized, however, that a high proportion of the unmarried females who live together never have contacts which are in any sense sexual.

Percentage of Total Outlet. Homosexual contacts are highly effective in bringing the female to orgasm (p. 467). In spite of their relatively low incidence, they had accounted for an appreciable proportion of the total number of orgasms of the entire sample of unmarried females. Before fifteen years of age, the homosexual contacts had been surpassed only by masturbation and heterosexual coitus as sources of outlet, and they were again in that position among the still single females after age thirty (Table 171 , Figure 110 ). Among these single females, orgasms obtained from homosexual contacts had accounted for some 4 per cent of the total outlet of the younger adolescent females, some 1 per cent of the outlet of the unmarried females in their early twenties, and some 19 per cent of the total outlet of the females who were still unmarried in their late thirties (Table 128 ).

Among the married females in the sample, homosexual contacts had usually accounted for less than one-half of one per cent of all their orgasms (Table 128 ).

However, among the females who had been previously married, homosexual contacts had become somewhat more important again as a source of outlet. They had accounted for something around 2 per cent of the total outlet of the younger females in the group, and for nearly 10 per cent of the outlet of the females who were in their early thirties (Table 128 ).

Number of Years Involved. For most of the females in the sample, the homosexual activity had been limited to a relatively short period of time (Table 129 ). For nearly a third (32 per cent) of those who had had any experience, the experience had not occurred more than ten times, and for many it had occurred only once or twice. For nearly a half (47 per cent, including part of the above 82 per cent), the experience had been confined to a single year or to a part of a single year. For another quarter (25 per cent), the activity had been spread through two or three years. These totals, interesting to note, had not materially differed between females who were in the younger, and females who were in the older age groups at the time they contributed their histories. This means that for most of them, most of the homosexual activity had occurred in the younger years. There were a quarter (28 per cent) whose homosexual experience had extended for more than three years. There were histories of a few females whose activities had extended for as many as thirty or forty years, and more extended samples of older females would undoubtedly show cases which had continued for still longer periods of time.

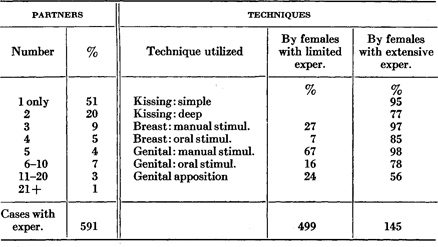

Number of Partners. In the sample of single females, a high proportion (51 per cent) of those who had had any homosexual experience had had it with only a single partner, up to the time at which they had contributed their histories to the record. Another 20 per cent had had it with two different partners. Only 29 per cent had had three or more partners in their homosexual relations, and only 4 per cent had had more than ten partners (Table 130 ). 13

In this respect, the female homosexual record contrasts sharply with that for the male. Of the males in the sample who had had homosexual experience, a high proportion had had it with several different persons, and 22 per cent had had it with more than ten partners (p. 683). Some. of them had had experience with scores and in many instances with hundreds of different partners. Apparently, basic psychologic factors account for these differences in the extent of the promiscuity of the female and the male (Chapter 16 ).

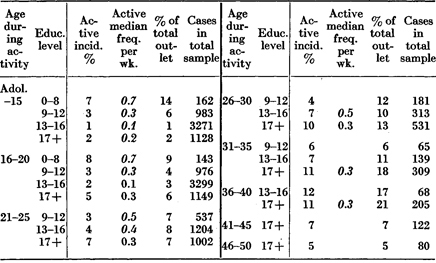

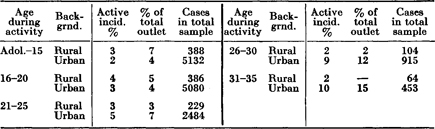

The incidences of homosexual activity among the females in the sample had been definitely correlated with their educational backgrounds. This was more true than with any of their other sexual activities.

Accumulative Incidence. Homosexual responses had occurred among a smaller number of the females of the grade school and high school sample, a distinctly larger number of the college sample, and still more of the females who had gone on into graduate work (Table 131 ). At thirty years of age, for instance, there were 10 per cent of the grade school sample, 18 per cent of the high school sample, 25 per cent of the college sample, and 33 per cent of the graduate group who had recognized that they had been erotically aroused by other females. 14

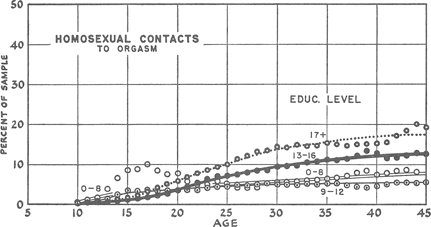

Figure 85. Accumulative incidence: homosexual contacts to orgasm, by educational level

Based on total sample, including single, married, and previously married females. Data from Table 131 .

Overt contacts had similarly occurred in a smaller number of the females of the lower educational levels and a larger number of those of the upper educational levels. At thirty years of age, the accumulative incidence figures had reached 9 per cent, 10 per cent, 17 per cent, and 24 per cent in the grade school, high school, college, and graduate groups, respectively.

At thirty years of age, homosexual experience to the point of orgasm had occurred in 6 per cent of the grade school sample, 5 per cent of the high school sample, 10 per cent of the college sample, and 14 per cent of the graduate sample (Table 131 , Figure 85 ).

We have only hypotheses to account for the extension of this type of sexual activity in the better educated groups. We are inclined to believe that moral restraint on pre-marital heterosexual activity is the most important single factor contributing to the development of a homosexual history, and such restraint is probably most marked among the younger and teen-age girls of those social levels that send their daughters to college. In college, these girls are further restricted by administrators who are very conscious of parental concern over the heterosexual morality of their offspring. The prolongation of the years of schooling, and the consequent delay in marriage (Figure 46 ), interfere with any early heterosexual development of these girls. This is particularly true if they go on into graduate work. All of these factors contribute to the development of homosexual histories. There may also be a franker acceptance and a somewhat lesser social concern over homosexuality in the upper educational levels.

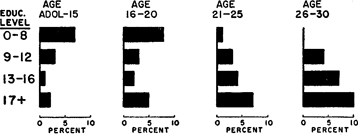

Figure 86. Active incidence: homosexual contacts to orgasm, by educational level

Data based on single females; see Table 127 .

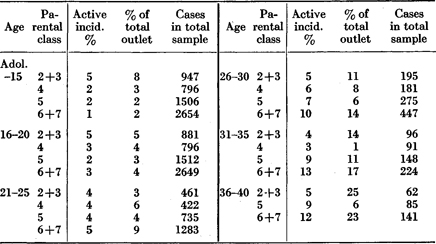

Active Incidence to Orgasm. Between adolescence and fifteen years of age, homosexual contacts to orgasm were more common in the sample of high school females and in the limited sample of grade school females (Table 127 , Figure 86 ). However, between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-five, while the active incidences stood at something between 3 and 6 per cent among the high school females, they had risen to something between 7 and 11 per cent in the college and graduate school groups.

Frequency to Orgasm. Between adolescence and fifteen years of age, the active median frequencies of homosexual contacts to orgasm among the females in the sample were higher in the grade school and high school groups, and lower among the sexually more restrained young females of the upper educational levels (Table 127 ). Subsequently these discrepancies had more or less disappeared, and after age twenty the frequencies had averaged once in two or three weeks for the median females of all the educational levels represented in the sample.

Percentage of Total Outlet. Among the younger teen-age girls, 14 per cent of the orgasms of the grade school group had come from homosexual contacts, while only 1 or 2 per cent of the orgasms of the college and graduate groups had come from such sources (Table 127 ). Subsequently, these differences were reversed, and between thirty and forty years of age the still unmarried females of the graduate group were deriving 18 to 21 per cent of their total outlet from homosexual sources. If one-fifth of the outlet of this group came from homosexual sources, and only a little more than one-tenth (11 per cent) of the females in the group were having such activity, it is evident that the females who were having homosexual experience were reaching orgasm more frequently than those who were depending on other types of sexual activity for their outlet.

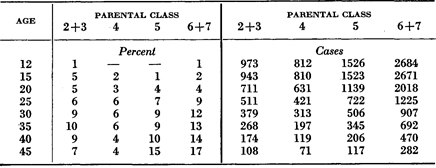

In the available sample there seems to be little or nothing in the accumulative or active incidences, or the frequencies of the homosexual contacts, which suggests that there is any correlation with the occupational classes of the homes in which the females were raised (Tables 132 , 133 ). There is only minor evidence that the accumulative incidences of contacts to the point of orgasm may have involved a slightly higher percentage of the females who came from upper white collar homes, and a smaller percentage of those who came from the homes of laboring groups—at age forty, a matter of 14 per cent in the first instance, and under 10 per cent in the second instance (Table 132 ).

The active incidences in the younger age groups were higher among the females who had come from the homes of laborers; but after the age of twenty the differences had largely disappeared, and after the age of twenty-five the females who had come from upper white collar homes were the ones most often involved (Table 133 ).

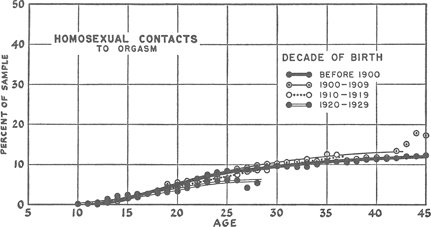

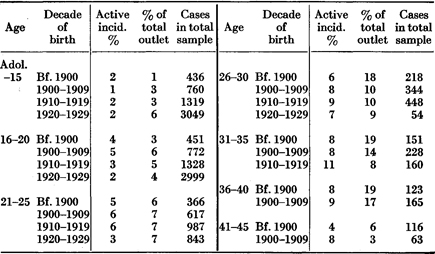

In the available sample, the accumulative incidences of homosexual contacts to the point of orgasm had been very much the same for the females who were born in the four decades on which we have data. There is no evidence that there are any more females involved in homosexual contacts today than there were in the generation born before 1900 or in any of the intermediate decades (Table 134 , Figure 87 ). 15 Similarly, the number of females having homosexual contacts in particular five-year periods of their lives (the active incidences), the frequencies of such contacts, and the percentages of the total outlet which had been derived from homosexual contacts, do not seem to have varied in any consistent fashion during the four decades covered by the sample (Table 135 ).

Figure 87. Accumulative incidence: homosexual contacts to orgasm, by decade of birth

Based on total sample, including single, married, and previously married females. Data from Table 134 .

It is not immediately obvious why this, among all other types of sexual activity, should have been unaffected by the social forces which led to the marked increase in the incidences of masturbation, heterosexual petting, pre-marital coitus, and even nocturnal dreams among American females immediately after the first World War, and which have kept these other activities on the new levels or have continued to keep them rising since then.

There do not seem to be any consistent correlations between either the accumulative incidences, the active incidences, or the frequencies of homosexual contacts, and the ages at which the females in the sample had turned adolescent (Tables 136 , 137 ). Among males we found (1948:320) that those who turned adolescent at earlier ages were more often involved in homosexual contacts as well as in masturbation and pre-marital heterosexual contacts. The absence of such a correlation among females may be significant (see Chapter 18 ).

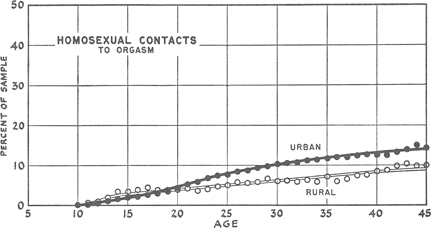

The accumulative incidences of homosexual contacts to the point of orgasm were a bit higher among the city-bred females in the sample (Table 138 , Figure 88 ). The active incidences appear to have been a bit higher among the rural females in their teens, but they were higher among urban females after the age of twenty (Table 139 ). The data, however, are insufficient to warrant final conclusions.

Figur 88. Accumulative incidence: homosexual contacts to orgasm, by rural-urban background

Based on total sample, including single, married, and previously married females. Data from Table 138 .

The educational levels and religious backgrounds of the females in the sample were the social factors which were most markedly correlated with the incidences of their homosexual activity.

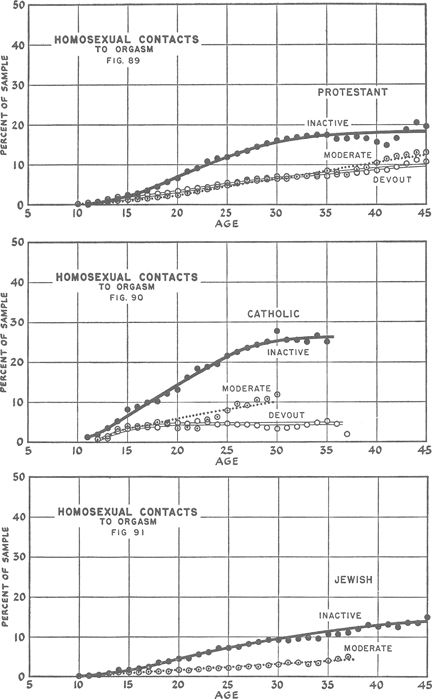

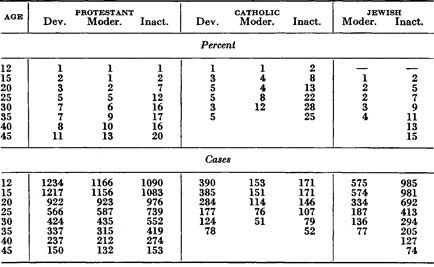

Accumulative Incidence. In the Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish groups on which we have samples, fewer of the devout females were involved in homosexual contacts to the point of orgasm, and distinctly more of the females who were least devout religiously (Table 140 , Figures 89-91 ). For instance, by thirty-five years of age among the Protestant females some 7 per cent of the religiously devout had had homosexual relations to orgasm, but 17 per cent of those who were least actively identified with the church had had such relations. The differences were even more marked in the Catholic groups: by thirty-five years of age, only 5 per cent of the devoutly Catholic females had had homosexual relations to the point of orgasm, but some 25 per cent of those who were only nominally connected with the church. The differences between the Jewish groups lay in the same direction.

Figures 89-91. Accumulative incidence: homosexual contacts to orgasm, by religious background

Based on total sample, including single, married, and previously married females. Data from Table 140 .

There is little doubt that moral restraints, particularly among those who were most actively connected with the church, had kept many of the females in the sample from beginning homosexual contacts, just as some were kept from beginning heterosexual activities. On the other hand, as we have already noted, some of the females had become involved in homosexual activities because they were restrained by the religious codes from making pre-marital heterosexual contacts, and such devout individuals had sometimes become so disturbed in their attempt to reconcile their behavior and their moral codes that they had left the church, thereby increasing the incidences of homosexual activity among the religiously inactive groups.

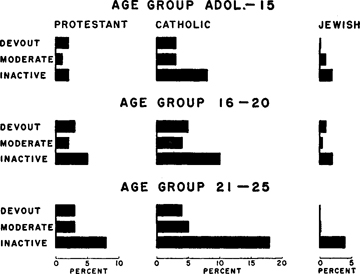

Figure 92. Active incidence: homosexual contacts to orgasm, by religious background

Data based on single females; see Table 141 .

Active Incidence. In eleven out. of the twelve groups on which we have data available for comparisons, the active incidences of homosexual contacts to the point of orgasm were lower among the more devout females and higher among those who were religiously least devout (Table 141 , Figure 92 ). For instance, among the younger adolescent groups, there were 3 per cent of the devoutly Catholic females who were having homosexual relations to the point of orgasm, but 8 per cent of the inactive Catholics. Similarly, at ages twenty-six to thirty, among the still unmarried Protestant groups, 5 per cent of the more devout females were involved, but 13 per cent of the least devout females (Table 141 ).

Active Median Frequency to Orgasm. In the sample, there does not seem to have been any consistent correlation between the active median frequencies of homosexual activities and the religious backgrounds of the females in the various groups (Table 141 ).

Percentage of Total Outlet. The percentage of the total outlet which had been derived by the various groups of females from their homosexual relations was, in most instances, correlated with the number of females (the active incidences) who were involved in such activity (Table 141 ); but among the religiously more devout females, and especially in the older age groups, the percentage of the total outlet derived from homosexual sources was in excess and often in considerable excess of what the incidences might have led one to expect. This had depended in part upon the fact that an unusually large number of the religiously devout were not reaching orgasm in any sort of sexual activity (Table 165 ), and for those who had accepted homosexual relations and reached orgasm in them, those relations had become a chief source of all the orgasms experienced by the group. It is also possible that a selective factor was involved, and that the sexually more responsive females were the ones who had most often accepted homosexual relations.

The techniques utilized in the homosexual relations among the females in the sample were the techniques that are ordinarily utilized in heterosexual petting which precedes coitus, or which may serve as an end in itself. The homosexual techniques had differed primarily in the fact that they had not included vaginal penetrations with a true phallus.

The physical contacts between the females in the homosexual relations had often depended on little more than simple lip kissing and generalized body contacts (Table 130 ). In some cases the contacts, even among the females who had long and exclusively homosexual histories, had not gone beyond this. In many instances the homosexual partners had not extended their techniques to breast and genital stimulation for some time and in some cases for some period of years after the relationships had begun. Ultimately, however, among the females in the sample who had had more extensive homosexual experience, simple kissing and manual manipulation of the breast and genitalia had become nearly universal (in 95 to 98 per cent); and deep kissing (in 77 per cent), more specific oral stimulation of the female breast (in 85 per cent), and oral stimulation of the genitalia (in 78 per cent) had become common techniques. In something more than half of the histories (56 per cent), there had been genital appositions which were designed to provide specific and mutual stimulation (Table 130 ). But vaginal penetrations with objects which had served as substitutes for the male penis had been quite rare in the histories. 16

It is not generally understood, either by males or by females who have not had homosexual experience, that the techniques of sexual relations between two females may be as effective as or even more effective than the petting or coital techniques ordinarily utilized in heterosexual contacts. But if it is recalled that the clitoris of the female, the inner surfaces of the labia minora, and the entrance to the vagina are the areas which are chiefly stimulated by the male penetrations in coitus (pp. 57 4 ff.), it may be understood that similar tactile or oral stimulation of those structures may be sufficient to bring orgasm. However, for females who find satisfaction in having the deeper portions of the vagina penetrated during coitus (pp. 579-584), the lack of this sort of physical stimulation may make the physical satisfactions of homosexual relationships inferior to those which are available in coitus.

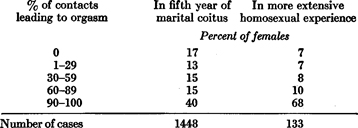

Nevertheless, comparisons of the percentages of contacts which had brought orgasm in marital coitus among the females who had been married for five years, and in the homosexual relations of females who had had about the same number of years of homosexual experience, show the following:

The higher frequency of orgasm in the homosexual contacts may have depended in part upon the considerable psychologic stimulation provided by such relationships, but there is reason for believing that it may also have depended on the fact that two individuals of the same sex are likely to understand the anatomy and the physiologic responses and psychology of their own sex better than they understand that of the opposite sex. Most males are likely to approach females as they, the males, would like to be approached by a sexual partner. They are likely to begin by providing immediate genital stimulation. They are inclined to utilize a variety of psychologic stimuli which may mean little to most females (Chapter 16 ). Females in their heterosexual relationships are actually more likely to prefer techniques which are closer to those which are commonly utilized in homosexual relationships. They would. prefer a considerable amount of generalized emotional stimulation before there is any specific sexual contact. They usually want physical stimulation of the whole body before there is any specifically genital contact. They may especially want stimulation of the clitoris and the labia minora, and stimulation which, after it has once begun, is followed through to orgasm without the interruptions which males, depending to a greater degree than most females do upon psychologic stimuli, often introduce into their heterosexual relationships (p. 668).

It is, of course, quite possible for males to learn enough about female sexual responses to make their heterosexual contacts as effective as females make most homosexual contacts. With the additional possibilities which a union of male and female genitalia may offer in a heterosexual contact, and with public opinion and the mores encouraging heterosexual contacts and disapproving of homosexual contacts, relationships between females and males will seem, to most persons, to be more satisfactory than homosexual relationships can ever be. Heterosexual relationships could, however, become more satisfactory if they more often utilized the sort of knowledge which most homosexual females have of female sexual anatomy and female psychology.

There are some persons whose sexual reactions and socio-sexual activities are directed only toward individuals of their own sex. There are others whose psychosexual reactions and socio-sexual activities are directed, throughout their lives, only toward individuals of the opposite sex. These are the extreme patterns which are labeled homosexuality and heterosexuality. There remain, however, among both females and males, a considerable number of persons who include both homosexual and heterosexual responses and/or activities in their histories. Sometimes their homosexual and heterosexual responses and contacts occur at different periods in their lives; sometimes they occur coincidentally. This group of persons is identified in the literature as bisexual.

That there are individuals who react psychologically to both females and males, and who have overt sexual relations with both females and males in the course of their lives, or in any single period of their lives, is a fact of which many persons are unaware; and many of those who are academically aware of it still fail to comprehend the realities of the situation. It is a chatacteristic of the human mind that it tries to dichotomize in its classification of phenomena. Things either are so, or they are not so. Sexual behavior is either normal or abnormal, socially acceptable or unacceptable, heterosexual or homosexual; and many persons do not want to believe that there are gradations in these matters from one to the other extreme. 17

In regard to sexual behavior it has been possible to maintain this dichotomy only by placing all persons who are exclusively heterosexual in a heterosexual category, and all persons who have any amount of experience with their own sex, even including those with the slightest experience, in a homosexual category. The group that is identified in the public mind as heterosexual is the group which, as far as public knowledge goes, has never had any homosexual experience. But the group that is commonly identified as homosexual includes not only those who are known or believed to be exclusively homosexual, but also those who are known to have had any homosexual experience at all. Legal penalties, public disapproval, and ostracism are likely to be leveled against a person who has had limited homosexual experience as quickly as they are leveled against those who have had exclusive experience. It would be as reasonable to rate all individuals heterosexual if they have any heterosexual experience, and irrespective of the amount of homosexual experience which they may be having. The attempt to maintain a simple dichotomy on these matters exposes the traditional biases which are likely to enter whenever the heterosexual or homosexual classification of an individual is involved.

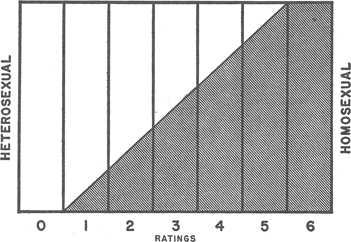

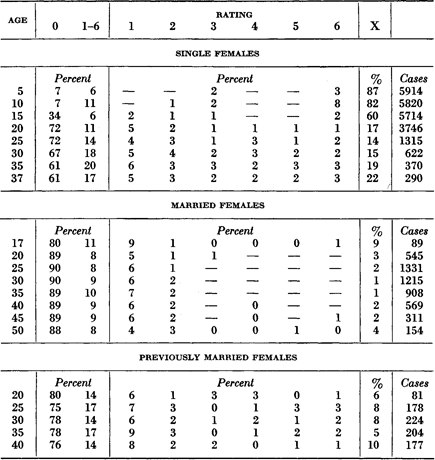

Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating. Only a small proportion of the females in the available sample had had exclusively homosexual histories. An adequate understanding of the data must, therefore, depend upon some balancing of the heterosexual and homosexual elements in each history. This we have attempted to do by rating each individual on a heterosexual-homosexual scale which shows what proportion of her psychologic reactions and/or overt behavior was heterosexual, and what proportion of her psychologic reactions and/or overt behavior was homosexual (Figure 93 ). We have done this for each year for which there is any record. This heterosexual-homosexual rating scale was explained in our volume on the male (1948:636-659), but before applying it to the data on the female it seems desirable to summarize again the principles involved in the construction and use of the scale.

Figure 93. Heterosexual-homosexual rating scale

Definitions of the ratings are as follows: 0 = entirely heterosexual. 1 = largely heterosexual, but with incidental homosexual history. 2 = largely heterosexual, but with a distinct homosexual history. 3 = equally heterosexual and homosexual. 4 = largely homosexual, but with distinct heterosexual history. 5 = largely homosexual, but with incidental heterosexual history. 6 = entirely homosexual.

¶ The ratings represent a balance between the homosexual and heterosexual aspects of an individual’s history, rather than the intensity of his or her psychosexual reactions or the absolute amount of his or her overt experience.

¶ Individuals who fall into any particular classification may have had various and diverse amounts of overt experience. An individual who has had little or no experience may receive the same classification as one who has had an abundance of experience, provided that the heterosexual and homosexual elements in each history bear the same relation to each other.

¶ The ratings depend on the psychologic reactions of the individual and on the amount of his or her overt experience. An individual may receive a rating on the scale even if he or she has had no overt heterosexual or homosexual experience.

¶ Since the psychologic and overt aspects of any history often parallel each other, they may be given equal weight in many cases in determining a rating. But in some cases one aspect may seem more significant than the other, and then some evaluation of the relative importance of the two must be made. We find, however, that most persons agree in their ratings of most histories after they have had some experience in the use of the scale. In our own research, where each year of each individual history has been rated independently by two of us, we find that our independent ratings differ in less than one per cent of the year-by-year classifications.

¶ An individual may receive a rating for any particular period of his or her life, whether it be the whole life span or some smaller portion of it. In the present study it has proved important to give ratings to each individual year, for some individuals may materially change their psychosexual orientation in successive years.

¶ While the scale provides seven categories, it should be recognized that the reality includes individuals of every intermediate type, lying in a continuum between the two extremes and between each and every category on the scale.

The categories on the heterosexual-homosexual scale (Figure 93 ) may be defined as follows:

0. Individuals are rated as 0 ’s if all of their psychologic responses and all of their overt sexual activities are directed toward persons of the opposite sex. Such individuals do not recognize any homosexual responses and do not engage in specifically homosexual activities. While more extensive analyses might show that all persons may on occasion respond to homosexual stimuli, or are capable of such responses, the individuals who are rated 0 are those who are ordinarily considered to be completely heterosexual.

1. Individuals are rated as 1 ’s if their psychosexual responses and/or overt experience are directed almost entirely toward individuals of the opposite sex, although they incidentally make psychosexual responses to their own sex, and/ or have incidental sexual contacts with individuals of their own sex. The homosexual reactions and/or experiences are usually infrequent, or may mean little psychologically, or may be initiated quite accidentally. Such persons make few if any deliberate attempts to renew their homosexual contacts. Consequenly the homosexual reactions and experience are far surpassed by the heterosexual reactions and! or experience in the history.

2. Individuals are rated as 2 ’s if the preponderance of their psychosexual responses and/or overt experiences are heterosexual, although they respond rather definitely to homosexual stimuli and! or have more than incidental homosexual experience. Some of these individuals may have had only a small amount of homosexual experience, or they may have had a considerable amount of it, but the heterosexual element always . predominates. Some of them may turn all of their overt experience in one direction while their psychosexual responses tum largely in the opposite direction; but they are always erotically aroused by anticipating homosexual experience and/or in their physical contacts with individuals o their own sex.

3. Individuals are rated as 3 ’s if they stand midway on the heterosexual-homosexual scale. They are about equally heterosexual and homosexual in their psychologic responses and/ or in their overt experience. They accept or equally enjoy both types of contact and have no strong preferences for the one or the other.

4. Individuals are rated as 4 ’s if their psychologic responses are more often directed toward other individuals of their own sex and/or if their sexual contacts are more often had with their own sex. While they prefer contacts with their own sex, they, nevertheless, definitely respond toward and/or maintain a fair amount of overt contact with individuals of the opposite sex.

5. Individuals are rated as 5 ’s if they are almost entirely homosexual in their psychologic responses and/or their overt activities. They respond only incidentally to indiviauals of the opposite sex, and/or have only incidental overt experience with the opposite sex.

6. Individuals are rated as 6 ’s if they are exclusively homosexual in their psychologic responses, and in any overt experience in which they give any evidence of responding. Some individuals may be rated as 6’s because of their psychologic responses, even though they may never have overt homosexual contacts. None of these individuals, however, ever respond psychologically toward, or have overt sexual contacts in which they respond to individuals of the opposite sex.

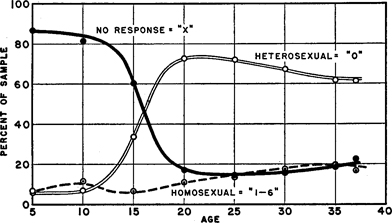

X. Finally, individuals are rated as X ’s if they do not respond erotically to either heterosexual or homosexual stimuli, and do not have overt physical contacts with individuals of either sex in which there is evidence of any response. After early adolescence there are very few males in this classification (see our 1948: 658), but a goodly number of females belong in this category in every age group (Table 142 , Figure 95 ). It is not impossible that further analyses of these individuals might show that they do sometimes respond to socio-sexual stimuli, but they are unresponsive and inexperienced as far as it is possible to determine by any ordinary means.

Percentage With Each Rating. It should again be pointed out, as we did in our volume on the male (1948:650), that it is impossible to determine the number of persons who are “homosexual” or “heterosexual.” It is only possible to determine how many persons belong, at any particular time, to each of the classifications on a heterosexual-homosexual scale. The distribution of the available female sample on the heterosexual- homosexual scale is shown in Table 142 and Figure 94 . These incidence figures differ from the incidence figures presented in the earlier part of this chapter, because the heterosexual-homosexual ratings are based on psychologic responses and overt experience, while the accumulative and active incidences previously shown are (with the exception of Table 131 and Figure 82 ) based solely on overt contacts.

The following generalizations may be made concerning the experience of the females in the sample, up to the time at which they contributed their histories to the present study.

Something between 11 and 20 per cent of the unmarried females and 8 to 10 per cent of the married females in the sample were making at least incidental homosexual responses, or making incidental or more specific homosexual contacts—i.e. , rated 1 to 6 —in each of the years between twenty and thirty-five years of age. Among the previously married females, 14 to 17 per cent were in that category (Table 142 ).

Something between 6 and 14 per cent of the unmarried females, and 2 to 3 per cent of the married females, were making more than incidental responses, and/or making more than incidental homosexual contacts—i.e. , rated 2 to 6 —in each of the years between twenty and thirty-five years of age. Among the previously married females, 8 to 10 per cent were in that category (Table 142 ).

Figure 94. Active incidence: heterosexual-homosexual ratings, single females, age twenty-five

For definitions of the ratings, seep. 471. Data from Table 142 .

Between 4 and 11 per cent of the unmarried females in the sample, and 1 to 2 per cent of the married females, had made homosexual responses, and/or had homosexual experience, at least as frequently as they had made heterosexual responses and/or had heterosexual experience—i.e. , rated 3 to 6 —in each of the years between twenty and thirty-five years of age. Among the previously married females, 5 to 7 per cent were in that category (Table 142 ).

Between 3 and 8 per cent of the unmarried females in the sample, and something under 1 per cent of the married females, had made homosexual responses and/or had homosexual experience more often than they had responded heterosexually and/or had heterosexual experience—i.e. , rated 4 to 6 —in each of the years between twenty and thirty-five years of age. Among the previously married females, 4 to 7 per cent were in that category (Table 142 ).

Between 2 and 6 per cent of the unmarried females in the sample, but less than 1 per cent of the married females, had been more or less exclusively homosexual in their responses and/ or overt experience—i.e. , rated 5 or 6 —in each of the years between twenty and thirty-five years of age. Among the previously married females, 1 to 6 per cent were in that category (Table 142 ). 18

Between 1 and 3 per cent of the unmarried females in the sample, but less than three in a thousand of the married females, had been exclusively homosexual in their psychologic responses and/ or overt experience—i.e. , rated 6 —in each of the years between twenty and thirty-five years of age. Among the previously married females, 1 to 3 per cent were in that category (Table 142 ).

Figure 95. Active incidence: heterosexual-homosexual ratings, single females

For definitions of the ratings, X, 0, and 1-6, see p. 471. Data from Table 142 .

Between 14 and 19 per cent of the unmarried females in the sample, and 1 to 3 per cent of the married females, had not made any sociosexual responses (either heterosexual or homosexual)—i.e. , rated X —in each of the years between twenty and thirty-five years of age. Among the previously married females, 5 to 8 per cent were in that category (Table 142 ).

Extent of Female vs. Male Homosexuality. The incidences and frequencies of homosexual responses and contacts, and consequently the incidences of the homosexual ratings, were much lower among the females in our sample than they were among the males on whom we have previously reported (see our 1948:650-651). Among the females, the accumulative incidences of homosexual responses had ultimately reached 28 per cent; they had reached 50 per cent in the males. The accumulative incidences of overt contacts to the point of orgasm among the females had reached 13 per cent (Table 131 , Figure 82 ); among the males they had reached 37 per cent. This means that homosexual responses had occurred in about half as many females as males, and contacts which had proceeded to orgasm had occurred in about a third as many females as males. Moreover, compared with the males, there were only about a half to a third as many of the females who were, in any age period, primarily or exclusively homosexual.

A much smaller proportion of the females had continued their homosexual activities for as many years as most of the males in the sample.

A much larger proportion (71 per cent) of the females who had had any homosexual contact had restricted their homosexual activities to a single partner or two; only 51 per cent of the males who had had homosexual experience had so restricted their contacts. Many of the males had been highly promiscuous, sometimes finding scores or hundreds of sexual partners.

There is a widespread opinion which is held both by clinicians and the public at large, that homosexual responses and completed contacts occur among more females than males. 19 This opinion is not borne out by our data, and it is not supported by previous studies which have been based on specific data. 20 This opinion may have originated in the fact that females are more openly affectionate than males in our culture. Women may hold hands in public, put arms about each other, publicly fondle and kiss each other, and openly express their admiration and affection for other females without being accused of homosexual interests, as men would be if they made such an open display of their interests in other men. Males, interpreting what they observe in terms of male psychology, are inclined to believe that the female behavior reflects .emotional interests that must develop sooner or later into overt sexual relationships. Nevertheless, our data indicate that a high proportion of this show of affection on the part of the female does not reflect any psychosexual interest, and rarely leads to overt homosexual activity.

Not a few heterosexual males are erotically aroused in contemplating the possibilities of two females in a homosexual relation; and the opinion that females are involved in such relationships more frequently than males may represent wishful thinking on the part of such heterosexual males. Psychoanalysts may also see in it an attempt among males to justify or deny their own homosexual interests.

The considerable amount of discussion and bantering which goes on among males in regard to their own sexual activities, the interest which many males show in their own genitalia and in the genitalia of other males, the amount of exhibitionistic display which so many males put on in locker rooms, in shower rooms, at swimming pools, and at informal swimming holes, the male’s interest in photographs and drawings of genitalia and sexual action, in erotic fiction which describes male as well as female sexual prowess, and in toilet wall inscriptions portraying male genitalia and male genital functions, may reflect homosexual interests which are only infrequently found in female histories. The institutions which have developed around male homosexual interests include cafes, taverns, night clubs, public baths, gymnasia, swimming pools, physical culture and more specifically homosexual magazines, and organized homosexual discussion groups; they rarely have any counterpart among females. Many of these male institutions, such as the homosexually oriented baths and gymnasia, are of ancient historic origin, but there do not seem to have been such institutions for females at any time in history. The street and institutionalized homosexual prostitution which is everywhere available for males, in all parts of the world, is rarely available for females, anywhere in the world. 21 All of these differences between female and male homosexuality depend on basic psychosexual differences between the two sexes.

Society may properly be concerned with the behavior of its individual members when that behavior affects the persons or property of other members of the social oganization, or the security of the whole group. For these reasons, practically all societies everywhere in the world attempt to control sexual relations which are secured through the use of force or undue intimidation, sexual relations which lead to unwanted pregnancies, and sexual activities which may disrupt or prevent marriages or otherwise threaten the existence of the social organization itself. In various societies, however, and particularly in our own Judeo-Christian culture, still other types of sexual activity are condemned by religious codes, public opinion, and the law because they are contrary to the custom of the particular culture or because they are considered intrinsically sinful or wrong, and not because they do damage to other persons, their property, or the security of the total group.

The social condemnation and legal penalties for any departure from the custom are often more severe than the penalties for material damage done to persons or to the social organization. In our American culture there are no types of sexual activity which are as frequently condemned because they depart from the mores and the publicly pretended custom, as mouth-genital contacts and homosexual activities. There are practically no European groups, unless it be in England, and few if any other cultures elsewhere in the world which have become as disturbed over male homosexuality as we have here in the United States. Interestingly enough, there is much less public concern over homosexual activities among females, and this is true in the United States and in Europe and in still other parts of the world. 22

In an attempt to secure a specific measure of attitudes toward homosexual activity, all persons contributing histories to the present study were asked whether they would accept such contacts for themselves, and whether they approved or disapproved of other females or males engaging in such activity. As might have been expected, the replies to these questions were affected by the individual’s own background of experience or lack of experience in homosexual activity, and the following analyses are broken down on that basis.

Acceptance for Oneself. Of the 142 females in the sample who had had the most extensive homosexual experience, some regretted their experience and some had few or no regrets. The record is as follows:

| Regret | Percent |

| None | 71 |

| Slight | 6 |

| More or less | 3 |

| Yes | 20 |

| Number of cases | 142 |

Among the females who had never had homosexual experience, there were only 1 per cent who indicated that they intended to have it, and 4 per cent more who indicated that they might accept it if the opportunity were offered (Table 144 ) .

But among the females who had already had some homosexual experience, 18 per cent indicated that they expected to have more. Another 20 per cent were uncertain what they would do, and some 62 per cent asserted that they did not intend to continue their activity. Some of the 18 per cent who indicated that they would continue were making a conscious and deliberate choice based upon their experience and their decision that the homosexual activity was more satisfactory than any other type of sexual contact which was available to them. Some of the others were simply following the path of least resistance, or accepting a pattern which was more or less forced upon them.

The group which had had homosexual experience and who expected to continue with it represented every social and economic level, from the best placed to the lowest in the social organization. The list included store clerks, factory workers, nurses, secretaries, social workers, and prostitutes. Among the older women, it included many assured individuals who were happy and successful in their homosexual adjustments, economically and socially well established in their communities and, in many instances, persons of considerable significance in the social organization. Not a few of them were professionally trained women who had been preoccupied with their education or other matters in the day when social relations with males and marriage might have been available, and who in subsequent years had found homosexual contacts more readily available than heterosexual contacts. The group included women who were in business, sometimes in high positions as business executives, in teaching positions in schools and colleges, in scientific research for large and important corporations, women physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists, women in the auxiliary branches of the Armed Forces, writers, artists, actresses, musicians, and women in every other sort of important and less important position in the social organization. 23 For many of these women, heterosexual relations or marriage would have been difficult while they maintained their professional careers. For many of the older women no sort of socio-sexual contacts would have been available if they had not worked out sexual adjustments with the companions with whom they had lived, in some instances for many years. Considerable affection or strong emotional attachments were involved in many of these relationships.

On the other hand, some of the females in the sample who had had homosexual experience had become much disturbed over that experience. Often there was a feeling of guilt in having engaged in ah activity which is socially, legally, and religiously disapproved, and such individuals were usually sincere in their intention not to continue their activities. Some of them, however, were dissatisfied with their homosexual relations merely because they had had conflicts with some particular sexual partner, or because they had gotten into social difficulties as a result of their homosexual activities.

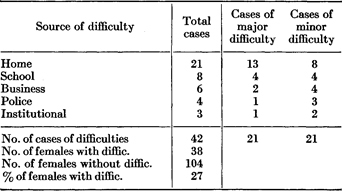

Some 27 per cent of those who had had more extensive homosexual experience had gotten into difficulty because of it (Table 145 ). Some of these females were disturbed because they had found it physically or socially impossible to continue relationships with the partner in whom they were most interested, and refused to contemplate the possibility of establishing new relationships with another partner. In a full half of these cases, the difficulties had originated in the refusal of parents or other members of their families to accept them after they had learned of their homosexual histories.

On the other hand, among those who had had homosexual experience, as well as among those who had not had experience, there were some who denied that they intended to have or to continue such activity, because it seemed to be the socially expected thing to disavow any such intention. Some of these females would actually accept such contacts if the opportunity came and circumstances were propitious. It is very difficult to know what an individual will do when confronted with an opportunity for sexual contact.

Approval for Others. As a further measure of female reactions to homosexual activity, each subject was asked whether she approved or disapproved or was neutral in regard to other persons, of her own or of the opposite sex, having homosexual activity. Each of the female subjects was also asked to indicate whether she would keep friends, female or male, after she had discovered that they had had homosexual experience. Since the question applied to persons whom they had previously accepted as friends, it provided a significant test of current attitudes toward homosexual behavior. From these data the following generalizations may be drawn:

1. The approval of homosexual activity for other females was much higher among the females in the sample who had had homosexual experience of their own. Some 23 per cent of those females recorded definite approval, and only 15 per cent definitely disapproved of other females having homosexual activity (Table 144 , Figure 96 ).

3. The females who had never had homosexual experience were less often inclined to approve of it for other persons. Some 4 per cent expressed approval of homosexual activity for males, but approximately 42 per cent definitely disapproved (Table 144 ). Some 4 per cent approved of activities for females, and 39 per cent disapproved.

4. Among the females who had had homosexual experience, some 88 per cent indicated that they would keep female friends after they had discovered their homosexual histories; 4 per cent said they would not (Table 144 , Figure 97 ). Some of these latter responses reflected the subject’s dissatisfaction with her own homosexual experience, but some represented the subject’s determination to avoid persons who might tempt her into renewing her own activities.

5. Among the females who had had homosexual experience, 74 per cent indicated that they would continue to keep male friends after they had discovered that they had homosexual histories, and 10 per cent said they would not (Table 144 , Figure 97 ). The disapproval of males with homosexual histories often depends upon the opinion that such males have undesirable characteristics, but this objection could not have been a factor in the present statistics because the question had concerned males whom the subject had previously accepted as friends.

6. Females who had never had homosexual experience were less often willing to accept homosexual female friends. Only 55 per cent said they would keep such friends, and 22 per cent were certain that they would not keep them (Table 144 , Figure 97 ). This is a measure of the intolerance with which our Judea-Christian culture views any type of sexual activity which departs from the custom.

7. Some 51 per cent of the females who had never had homosexual experience said that they would keep homosexual males as friends, 26 per cent said they would not, and 23 per cent were doubtful (Table 144 , Figure 97 ). As we have noted before (1948:663-664), this sort of ostracism by females often becomes a factor of considerable moment in forcing the male who has had some homosexual experience into exclusively homosexual patterns of behavior.

Moral Interpretations. The general condemnation of homosexuality in our particular culture apparently traces to a series of historical circumstances which had little to do with the protection of the individual or the preservation of the social organization of the day. In Hittite, Chaldean, and early Jewish codes there were no over-all condemnations of such activity, although there were penalties for homosexual activities between persons of particular social status or blood relationships, or homosexual relationships under other particular circumstances, especially when force was involved. 24 The more general condemnation of all homosexual relationships originated in Jewish history in about the seventh century B.C. , upon the return from the Babylonian exile. Both mouth-genital contacts and homosexual activities had previously been associated with the Jewish religious service, as they had been with the religious services of most of the other peoples of that part of Asia, and just as they have been in many other cultures elsewhere in the world. 25 In the wave of nationalism which was then developing among the Jewish people, there was an attempt to dis-identify themselves with their neighbors by breaking with many of the customs which they had previously shared with them. Many of the Talmudic condemnations were based on the fact that such activities represented the way of the Canaanite, the way of the Chaldean, the way of the pagan, and they were originally condemned as a form of idolatry rather than a sexual crime. Throughout the middle ages homosexuality was associated with heresy. 26 The reform in the custom (the mores) soon, however, became a matter of morals, and finally a question for action under criminal law.

Jewish sex codes were brought over into Christian codes by the early adherents of the Church, including St. Paul, who had been raised in the Jewish tradition on matters of sex. 27 The Catholic sex code is an almost precise continuation of the more ancient Jewish code. 28 For centuries in Medieval Europe, the ecclesiastic law dominated on all questions of morals and subsequently became the basis for the English common law, the statute laws of England, and the laws of the various states of the United States. This accounts for the considerable conformity between the Talmudic and Catholic codes and the present-day statute law on sex, including the laws on homosexual activity. 29

Condemnations of homosexual as well as some other types of sexual activity are based on the argument that they do not serve the prime function of sex, which is interpreted to be procreation, and in that sense represent a perversion of what is taken to be “normal” sexual behavior. It is contended that the general spread of homosexuality would threaten the existence of the human species, and that the integrity of the home and of the social organization could not be maintained if homosexual activity were not condemned by moral codes and public opinion and made punishable under the statute law. The argument ignores the fact that the existent mammalian species have managed to survive in spite of their widespread homosexual activity, and that sexual relations between males seem to be widespread in certain cultures (for instance, Moslem and Buddhist cultures) which are more seriously concerned with problems of overpopulation than they are with any threat of underpopulation. Interestingly enough these are also cultures in which the institution of the family is very strong.

Legal Attitudes. While it is, of course, impossible for laws to prohibit homosexual interests or reactions, they penalize, in every state of the Union, some or all of the types of contact which are ordinarily employed in homosexual relations. The laws are variously identified as statues against sodomy, buggery, perverse or unnatural acts, crimes against nature, public and in some instances private indecencies, grossly indecent behavior, and unnatural or lewd and lascivious behavior. The penalties in most of the states are severe, and in many states as severe as the penalties against the most serious crimes of violence. 30 The penalties are particularly severe when the homosexual relationships involve an adult with a young minor. 31 There is only one state, New York, which, by an indirection in the wording of its statute, appears to attach no penalty to homosexual relations which are carried on between adults in private and with the consent of both of the participating parties; and this sort of exemption also appears in Scandinavia and in many other European countries. There appears to be no other major culture in the world in which public opinion and the statute law so severely penalize homosexual relationships as they do in the United States today.