The growth of the Potteries as one of the country’s pre-eminent industrial regions was driven by migration. As a product of the Industrial Revolution, the pottery industry demanded workers and lots of them: some were skilled, others less so. Industry pioneers such as Wedgwood, Spode and Adams looked initially to their Staffordshire backyard. The Staffordshire Moorlands, rural parishes around Newcastle-under-Lyme and the south of the county were all sources of workers, as was the wider area from Cheshire in the west to Derbyshire in the east.

This is not to say that the rural economy was in decline; far from it. Although farming experienced a depression after the Napoleonic wars, Staffordshire escaped the worst effects because of demand from its growing industrial towns. Early moves towards enclosure gave the county one of the most efficient agricultural economies in the country and both landowners and tenant farmers prospered. With a high concentration of mixed farms, there were plenty of labouring jobs, many of them seasonal. The rural population found this work increasingly unattractive, however, and people left the land to get better paid work in urban areas such as Stafford, the Potteries and the Black Country. In the 1830s across Staffordshire as a whole nearly 600 more people left the countryside than settled. Out-migration continued to grow, reaching a peak of over 1,100 in the 1860s.

As domestic workers moved from the land to the potbanks, landowners were forced to look further afield to meet the labour shortage. From the 1820s, migrants from Ireland began to be seen in North Staffordshire. At first they were seasonal workers, who came to work on the farms, but after the Potato Famine of the late 1840s many stayed and took more permanent jobs. The Irish continued to come to Staffordshire in large numbers until at least the 1860s. At this point, increasing mechanization in agriculture started to destroy seasonal jobs and farm work became less of a draw.

In the Potteries the number of Irish immigrants never reached the concentrations seen in other Midlands towns. Figures are hard to come by: best estimates, based on census data, are that during the mid-nineteenth century Irish-born migrants accounted for around 2 to 3 per cent of the population.

Herson (2015) and associated website provide an account of Irish emigrants to Stafford during this period (https://divergentpaths stafford.wordpress.com).

Settlement records are one way of tracking rural migration. Settlement laws required incomers to possess a certificate issued by the parish they had left, which undertook to support them if they needed help within forty days of arriving in their new parish. To assess whether or not a person or family was entitled to legal settlement, an examination (interview) was conducted and based on this, either a certificate or a removal order was issued. These records can provide a detailed account of how the person came to be in the parish.

Settlement and removal records are found in several sources, depending on the period in question. Before 1836 settlement was a parish matter, so the records will be in the parish overseers’ papers at the SSA. After 1836, responsibility passed to the PLUs (see Chapter 5). If a removal order was issued, the receiving parish may hold a copy of the original order. Decisions on removals had to be ratified at the Quarter Sessions, where appeals were also heard. The relevant records are included either in the courts’ general proceedings or under a separate heading.

Census records should be the first port of call where Irish origins are suspected. Unfortunately, birthplaces for settlers are often not recorded as precisely as those born in Great Britain. An ancestor’s entry may simply say ‘Ireland’ without mentioning a county or village. As most (though by no means all) Irish settlers were Roman Catholic, church records at Findmypast should be consulted (see Chapter 4). Workhouse records (Chapter 5) and settlement records (see above) may also be useful. For research within Ireland see specialist guides such as Paton (2013).

Apprenticeship, religious and workhouse records may all be useful in establishing the vital link between the Potteries and an ancestor’s parish of origin and are dealt with in other chapters.

The success of the pottery industry in Staffordshire was built on assimilating the most up-to-date knowledge and innovations wherever they were to be found. Much of this know-how was brought by migrant workers. The role of the Dutch-born Elers brothers and of the early pioneers’ appetite for intelligence on developments in Europe have already been described (see Chapter 2). Later the tide turned and the Potteries became the supplier of skilled workers to locations within the British Isles, North America and beyond. For anyone anywhere in the English-speaking world wishing to start a pottery industry, the first place they would look for workers was the Staffordshire Potteries. Some went on short-term contracts, sometimes marrying and/or having families while they were away; others never returned.

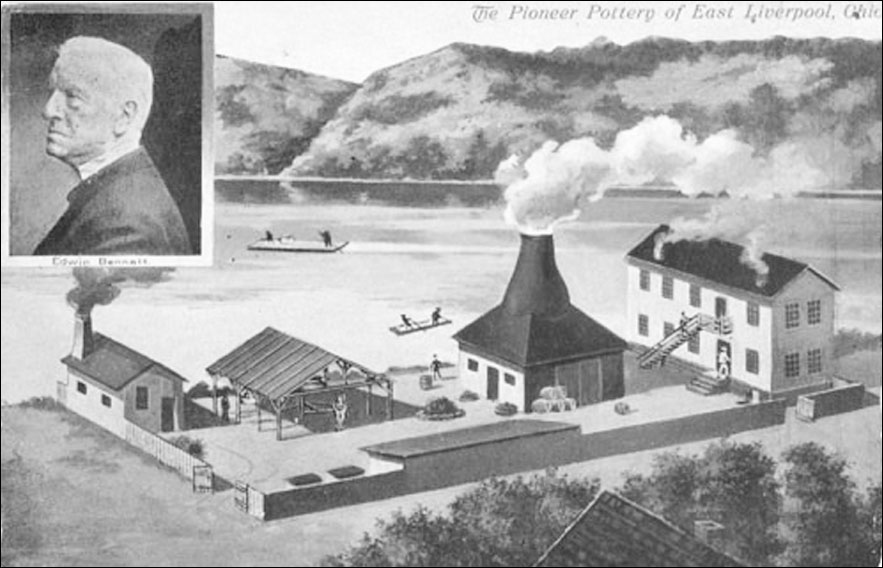

The pottery kiln built by Staffordshire-born potter James Bennett on the Ohio River in 1840. Bennett & Bros produced yellow ware and Rockingham ware in East Liverpool before moving to the Pittsburgh area. (Public domain)

Incomers, such as the French-born Leon Arnoux, continued to play an important role in the development of the Staffordshire Potteries into the nineteenth century. Born in Toulouse, Arnoux came to Britain in 1848 to study manufacturing techniques, Herbert Minton offering him the job of art director. He was responsible for Minton’s display at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and his new majolica coloured glazes won a reputation for both Minton’s and himself. His acclaim inspired other French and Continental artists to migrate to Minton’s. Arnoux encouraged local artists to familiarize themselves with Continental styles and productions, while his engineering background enabled him to effect several technical improvements in pottery making, including the down-draught oven.

By 1800 between 15,000 and 20,000 people were employed in the pottery industry in North Staffordshire. There was job security for all who had the necessary skills. Indeed, skilled labour was so scarce that a system of annual hiring was instituted, enabling employers to contract potters for a period of twelve months: this way employers could be sure they had enough skilled workers for the year ahead. Compared with conditions elsewhere, this made ceramics an extremely attractive industry. Some sought opportunities outside the Potteries. For instance, it is known that the pottery industry around Llanelli, south Wales, recruited many workers from Staffordshire (Bridge, 2004).

From the late 1820s, some of the more skilled potters began migrating to factories in Continental Europe. Both the Dutch and Swedish industries are known to have benefitted in this way (De Groot, 2002) and it is likely that others did too. The number of British potters per European firm was relatively small, tens at the most, but their expertise meant they made a significant impact. Their scarce skills and knowledge enabled them to command high wages compared with the local potters. Some even became managers or part-owners of the factory they worked for.

Edwin Abington, a former china painter from Stoke, became director of the Dutch company De Sphinx, which produced porcelain, in 1856. In turn, he recruited Richard Cartwright, an engraver from Burslem to work in the printing department. Together they reorganized the decorating of wares according to the ‘English system’ (meaning employing more women). Cartwright stayed for more than forty years, only returning to Staffordshire in 1899.

By the middle of the nineteenth century many in the Potteries were facing hardship. Mechanization and a depressed economy had led to an over-supply of workers and people’s thoughts turned to seeking a new life abroad. The Potters’ Emigration Society, started in around 1844 by trades unionists, was a short-lived attempt at organized emigration to the United States (see box below). Others went under similar schemes sponsored by organizations such as the British Temperance Society or of their own accord. A notice of 1852 refers to a tea meeting being held at the Primitive Methodist School Room in Tunstall for three young men (‘esteemed friends’) who were leaving for Australia. The reason for their departure is not stated but the timing fits that of the Victoria gold rush.

British potters, primarily from Staffordshire, played a major role in the growth of the American pottery industry. In his landmark work on this subject, economic historian Frank Thistlethwaite studied the careers of 100 British emigrant master and journeymen potters (Thistlethwaite, 1958). He found arrivals during every decade of the nineteenth century, with peaks between 1839 and 1850 and between the American Civil War and 1873. These emigrants established industries at East Liverpool, Ohio and Trenton, New Jersey, as well as other locations, with Rockingham ware as one of the principal products.

THE POTTERS’ JOINT STOCK EMIGRATION SOCIETY

In the 1840s, working and living conditions in the Potteries led some to seek a new life abroad. The scheme was instigated by William Evans, a Welshman who settled in the Potteries and became a prominent agitator for workers’ rights. As editor of the Potters’ Examiner newspaper, the mouthpiece of the United Branches of Operative Potters, he advocated organized emigration as a way of overcoming potters’ ills. As Evans saw it, emigration would relieve pressure within an overstaffed industry, allowing wages and sale prices of pottery to rise for those that remained.

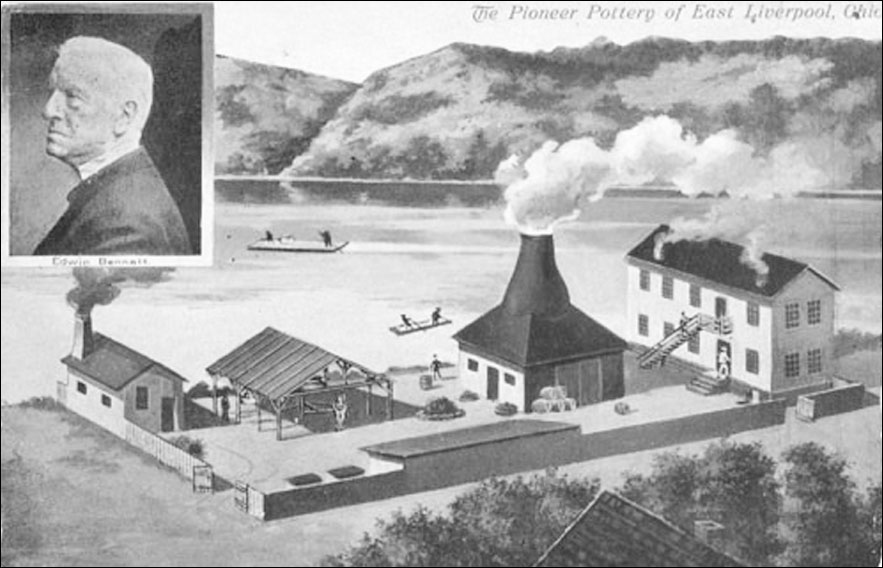

Notice to the ‘Shareholders of the Potters’ Emigration Society’ in the Potters’ Examiner and Workman’s Advocate, 18 May 1844. (Public domain)

The Potters’ Joint Stock Emigration Society and Savings Fund was founded in 1845 to promote the idea. The plan was to raise enough money to buy 12,000 acres of farmland in the United States. Once the land had been bought each shareholder was entered into a draw, with the successful ticketholders each winning a 20-acre holding. The initial draw was made in Hanley’s Meat Market, amid great excitement, with eight families being successful.

Evans used the Potters’ Examiner to promote the scheme. He published general information to prospective migrants and specific details about the Upper Mississippi area. Letters from migrants in Illinois, Ohio and Wisconsin to families back home were printed to demonstrate the benefits of migration. Rather than give money to the strike fund, readers were encouraged to donate to the savings fund that aimed to assist potters to emigrate.

Enough money was raised to purchase land in Wisconsin, where a new settlement called Pottersville was founded. But the immigrants were not prepared for the poor land and harsh frontier conditions. It is not known how many families made the journey: certainly fewer than 100. By 1850 the scheme was cancelled and its demise brought down the United Branches of Operative Potters. Many of the emigrants returned home, though others stayed and continued to build their lives in Wisconsin and elsewhere.

The Hobson Collection at the STCA has material related to William Evans and the Potters’ Joint Stock Emigration Society within its trades-union series [PA/HOB/1-4]. Goodby (2003) offers a detailed account of this doomed venture.

For some the emigration was involuntary. Justice was harsh during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and a sentence of transportation could be handed down for relatively minor offences such as stealing a sheep or a pair of breeches. Crimes such as rioting were even more likely to attract harsh punishment. In 1842 more than fifty potters and miners from across the Potteries were transported to Van Diemen’s Land (modern-day Tasmania) in the wake of Chartist unrest (see Chapter 4). Overall, more than 16,000 convicts from the West Midlands were transported to Australia between 1788 and 1852, the majority from industrial areas such as the Potteries and the Black Country.

Religious conviction was another motivation for people to leave their Staffordshire homeland. For example, around 1,200 Mormons from Staffordshire are thought to have emigrated to the United States during the middle years of the nineteenth century (Arrowsmith, 2003). Government assistance was available for those wishing to travel as free settlers. Between 1876 and 1879 more than 1,000 assisted migrants from the Midlands settled in Queensland alone. Of these around 430 came from Staffordshire, many of whom were miners.

JONATHAN LEAK: THE CONVICT POTTER

Jonathan Leak, a potter from Burslem, arrived in Australia as a convict in 1819. He had been convicted with two others of breaking into the home of Mrs Chatterley of Shelton and stealing a quantity of silver. Having initially been given a death sentence, this was commuted to transportation to Australia for life. He arrived at Sydney in the Colony of New South Wales on board the brig Recovery on 18 December 1819.

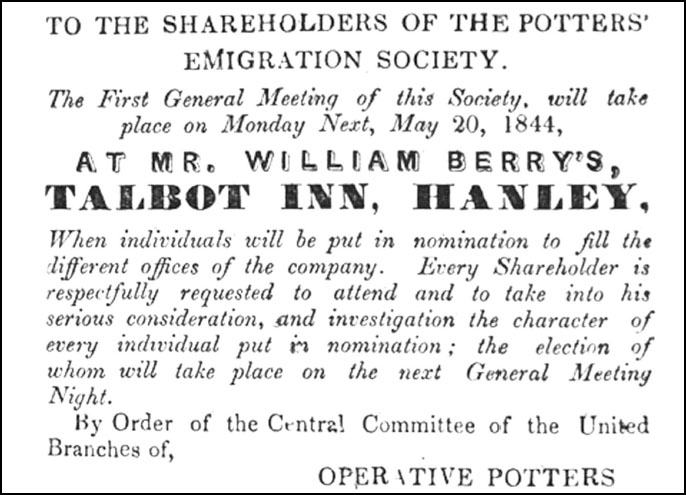

Earthenware bottles made by Jonathon Leak in New South Wales and a contemporary newspaper advertisement. (Public domain)

Before his conviction Leak had run his own pottery works in Commercial Street, Burslem. While working in the Government Pottery in New South Wales, he realized the potential for setting up his own business. Permission for this was granted, as well as for his wife and children to have free passage from England. He was given a ticket-of-leave, meaning he was permitted to spend the rest of his sentence working for himself provided he stayed within the colony.

In July 1823 Leak successfully obtained two land grants close to the Government Pottery, which enabled him to establish his own workshop. By 1828, Leak’s pottery was employing over twenty free men and he was the only potter operating in the colony. Newspaper articles refer to the production of 40,000 bricks weekly, while advertisements show a variety of goods for sale including tiles, bricks, ginger beer and other bottles, stone jars for pickling and preserving, and earthenware of all sorts.

Jonathan Leak was eventually granted a conditional pardon which gave him citizenship of the colony but no right to return to England. He is remembered as the most successful potter in the early history of Australia.

Like most towns in the nineteenth century, housing conditions in the Potteries varied markedly according to social class. Certain groups tended to congregate within specific areas, leading to a form of segregation according to class, occupation and ethnicity. Thus, miners would cluster together in rows of terraced houses situated close to the mines where they worked; the middle classes often lived in their own (sometimes suburban) estates; and the small Irish community tended to live close to one another in the poorer parts of town.

It had not always been like this. Given the Potteries’ rural origins, early eighteenth-century housing was in cottages and farms next to and between the potbanks. As the manufactories proliferated, workers’ housing, too, developed in a random, unplanned manner. Josiah Wedgwood’s model village alongside his factory at Etruria – which opened in 1769 – broke the mould, providing his workers with houses and gardens within a rural setting. But it was motivated as much by commercial necessity as philanthropy: Etruria was some distance from established centres of population and Wedgwood needed (by the standards of the day) large numbers of people to staff his new works.

At Etruria the houses were built along one street and had earth floors. According to the historian E.J. Warrillow: ‘They were roomy and well lit, with quaint windows of small panes of green glass . . . The front door steps were of iron, six inches wide, and were always kept beautifully polished . . . By 1865 there were approximately 125 numbered and 65 un-numbered houses in the village.’ While the concept was original, the houses themselves appear to have been similar to those being built elsewhere in the area at the time, albeit probably of superior quality. In general, workers’ properties comprised either one or two rooms downstairs, plus two upstairs. Few had water supplies or sanitation.

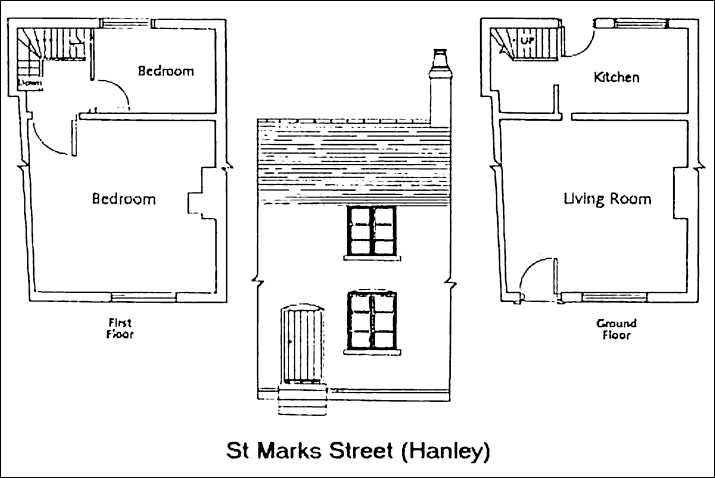

Plan of a worker’s house in St Mark’s Street, Hanley, built around 1840. The layout was typical of much working class housing of the time. (Stoke-on-Trent Historic Building Survey)

Roden (2008) discusses housing developments that occurred within the jurisdiction of the manor courts (known as copyhold areas) during the early stages of the Industrial Revolution. It shows that while a few famous potters were responsible for a handful of the developments, the majority were orchestrated by property speculators who were seeking to take advantage of the economic boom brought about by the pottery industry.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century many areas were beginning to be developed in a more systematic manner. Estates were laid out to rigid specifications. Although water and sewerage were still elementary, this was compensated to some extent by relatively low-density building, often with small gardens attached. Overall, the Potteries avoided the back-to-back dwellings and dense courts of the kind found in Birmingham and elsewhere, most likely because land for development was relatively abundant. The fact that some housing initiatives were financed by cooperative societies composed of artisans concerned about such matters may also have been a factor.

Estates often contained a church or chapel, a school, beerhouses and shops. Normally several grades of houses were built so that there was some mixing of classes and occupations. As most housing was built to rent, financiers and contractors were very aware of the need to attract the best custom. Features such as a hall (also called a ‘lobby’) or separate parlour were marks of superiority. In the Potteries, perhaps more than other area of the country, decorative detailing such as tiles and terracotta architraves were used across the housing stock. Numerous examples are still to be found, often in surprising places. In the better quality terraced housing room sizes increased and better provision was made for kitchens and lavatories. But at the same time, amenities such as front and rear gardens often disappeared.

By the mid-nineteenth century substantial detached and semi-detached houses for the middle classes became more numerous. Such households had, by definition, one or more live-in servants, which had significant implications for the layout of a house. As well as separate sleeping accommodation (usually very cramped), the design had to ensure that servants were kept out of sight as much as possible. Unsolicited collisions between mistress and servant, gentleman and tradesman were to be avoided at all costs. In the larger houses there was even gradation between the servants, so that the ‘upper’ servants were separated as much from the ‘lower’ servants as they were from the ‘family’.

One of the most notable examples of an estate of middle-class detached houses is The Villas, Stoke. This development of twenty-four dwellings was built in the early 1850s by the Stokeville Building Society to designs by the architect Charles Lynam. Herbert Minton was one of the main influencers behind the scheme. Predominantly following the Italian style, the houses all had clear differentiation between service and family areas. The Villas district was the first designated conservation area in Stoke-on-Trent and a number of the houses are listed.

Of course, housing of this quality was the exception rather than the norm. Indeed, over the course of the nineteenth century housing conditions for much of the working population actually deteriorated. Government inspectors commented on the conditions on frequent occasions. A report in 1848 expressed particular concern about common lodging houses. Conditions at a house in Stafford Street, Longton, kept by a Mrs Tomlinson, were typical:

In one house there are two rooms, four beds in one, and two in the other; they charge 9d. per night for adults, and 1d. for children. There are three houses: and six bed-rooms, eleven beds in the three front rooms, and five in the back rooms, making in all: sixteen beds in six rooms. These rooms are about ten feet square, and one window in each room. The back yards are confined, and the privy and cesspool broken and filthy.

The situation was not much improved by the end of the century, despite a number of reports and inquiries. The piecemeal nature of development led to a situation where the middle classes often lived cheek by jowl with housing of the very poorest quality and overcrowding was rife. An inquiry published in 1901 reported how:

at the rear of one of the best residential quarter, I found a house with three rooms rented at 4/- a week. I went straight upstairs here, keeping as far as possible from the filthy walls. The room I entered was about eleven feet square. It contained two bedsteads standing close together. A little boy and a woman were the only persons at home. They told me that the father, mother, and seven brothers and sisters occupied the apartment at night. The elder brother was fifteen years of age, and the youngest child was three. There was no bed covering; the place was over-run with vermin; and there was no ventilation, for the windows would not open. Consequently the air in the place was heavy and sickening.

Visiting the area in the 1930s, J.B. Priestley described housing conditions in the Potteries as ‘Victorian industrialism in its dirtiest and most cynical aspect’.

While the problem was clear for all to see, the authorities were slow to act. Not until the interwar period did the corporation begin a programme of house building. Between 1921 and 1939 over 8,000 council houses were built around the city. Estates constructed during this period include Bentilee, Abbey Hulton, Carmountside, High Lane and developments around Trent Vale. Further expansion followed after the Second World War, but years of undermining meant that the high-rise development that came to characterize other urban centres was, on the whole, avoided.

Rate books, held at Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, may provide an insight into your ancestor’s housing circumstances. Rates were collected in each parish for support of the sick and poor, and other local purposes such as highways, sewers, lighting and gaols. These can be used to establish whether your ancestors were tenants or property owners, while the rateable value of the property can be used to gauge the status of the occupant. The STCA has a good collection of municipal rate books from across the Six Towns [SD 1452] plus valuation lists for the period 1913–56 [SD 1214]; see search room handlists for both series.

Newcastle-under-Lyme Reference Library has microfilm copies of municipal rate books from 1840, intermittently to 1892. These cover the whole town by street, listing owners and occupiers. Rate books and valuation lists from urban and rural districts now covered by Staffordshire Moorlands are at Staffordshire Record Office [D4627].

Before incorporation, rates were paid to the parish. Under the Poor Relief Act of 1601 the inhabitants of a parish had to contribute, according to their ability to pay, towards the maintenance of the poor. From this the local taxation system, based on rates, grew and evolved. The STCA has a parish rate book for Stoke covering Penkhull, Boothen, Clayton and Seabridge, Shelton and Hanley and dated August 1807. There is also a rate collector’s ledger for St Paul’s parish, Burslem, 1817–1926 [SD 1592]. Other parish rate books may be found at the SRO but comparatively few have survived for North Staffordshire.

The so-called ‘1910 Lloyd George Domesday Survey’ was a property revaluation that took place at the end of the Edwardian period at the instigation of David Lloyd George, who was then Chancellor of the Exchequer. The resulting records link individual properties to extremely detailed Ordnance Survey maps used in 1910, which are coupled with the accompanying books containing basic information on the valuation of each property. The registers for Stoke-on-Trent are available at the STCA [D3573] and are now online for the whole country at TheGenealogist website (www.thegenealogist.co.uk).

The Stoke-on-Trent Historic Buildings Survey in the 1980s recorded all housing then surviving in the Potteries and built before 1914, and made detailed plans of over 100 buildings. This archive is now deposited at the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery. The City Surveyor’s Collection at the STCA has plans of Harpfield, Meir and other housing schemes, as well as files on aspects such as water supplies and sanitation [SA/CS].

Roden (2008) is a highly detailed and scholarly account of early housing developments in the Potteries during the period 1700–1832. The tenancies in this book are listed online at Staffordshire Name Indexes as ‘Copyhold Tenants of the Manor of Newcastle-under-Lyme, 1700–1832’. Rural properties may be covered by the Tithe Commutations of the 1830s and 1840s (see Chapter 8).

Arrowsmith, Stephen G., The Unidentified Pioneers: An Analysis of Staffordshire Mormons 1837 to 1870 (Brigham Young University, 2003); available at https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu

Bridge, Brian, Leaving Llanelli: Potters Returning to Staffordshire 1871– 1881 (Llanelli WEA journal, 2004)

de Groot, Gertjan, ‘British Potters in Swedish and Dutch Pottery Industries in the 19th Century’, conference paper (2002); available at www.researchgate.net/publication/319245599

Goodby, Miranda, ‘Our Home in the West: Staffordshire Potters and Their Emigration to America in the 1840s’, Ceramics in America (2003); available at: www.chipstone.org/article.php/75/Ceramics-in-America-2003/

Herson, John, Irish Families in Victorian Stafford (Manchester University Press, 2015)

Paton, Chris, Tracing Your Irish Family History on the Internet (Pen & Sword, 2013)

Roden, Peter, Copyhold Potworks and Housing of the Staffordshire Potteries, 1700–1832 (Wood Broughton Publications, 2008)

Thistlethwaite, Frank, ‘The Atlantic Migration of the Pottery Industry’, Economic History Review, 11, 264–78 (1958)