The pubes also present two types. First there are the genera in which the bones are directed anteriorly and meet by a median symphysis and have no posterior extension except for the proximal symphysis with the ischium. This type is represented by Cetiosaurus, Ornithopsis, Megalosaurus, and many genera figured by Professor Marsh. The second form of pubis has one limb which is directed backward parallel to the ischium, and another limb directed forward. It is typically seen in Omosaurus and Iguanodon. There are many variations in stoutness and details of form of the bones, but so far as I am aware these two plans comprise all the Dinosaurian genera.

—HARRY GOVIER SEELEY, ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF ANIMALS COMMONLY NAMED DINOSAURIA, 1887

“BIRD HIPS”

In the 1880s, the number of known dinosaurs was beginning to multiply as Cope and Marsh rapidly added to the list of species already known from Europe. All of these scientists tried to put together a scheme to classify all these groups of individual genera, such as Iguanodon and Megalosaurus and Cetiosaurus plus the new American dinosaurs. In 1866, Cope created the names “Ornithopoda” for iguanodonts and scelidosaurs, “Goniopoda” for Megalosaurus, and “Symphopoda” for Compsognathus. In 1870, Huxley only recognized the families Scelidosauridae, Iguanodontidaea, Megalosauridae, and Compsognathidae; and Harry Govier Seeley added the Cetiosauridae to the list (after Owen had originally described it but not realized it was a dinosaur; see chapter 3). Marsh used a different classification scheme from 1878 to 1884, recognizing orders for Stegosauria, Ornithopoda, Sauropoda, and Theropoda. All four of those groups are still in use today in some capacity. Cope, naturally, refused to recognize most of Marsh’s ideas or names, so in 1883 he wrote about groups he called the Ornithopoda, plus the “Opisthocoelia” for sauropods, “Goniopoda” for theropods, and Hallopoda for a group now known to be pseudosuchian archosaurs, not dinosaurs.

The chaos of names was a product not only of the Cope-Marsh feud but of the choice of anatomical parts that were emphasized, from the shape of the foot to the shape of the skull. Each scientist recognized lower-level groups for predators (Theropoda or “Goniopoda”), sauropods or “Opisthocoelia,” and nearly everyone used Ornithopoda for iguanodonts and their kin. But no one could cluster these many orders of dinosaurs into two or three larger groups.

In 1887, Seeley again tried to make sense of dinosaur classification. He noticed that the structure of the hips seemed to have only two basic forms. Many dinosaurs, such as Megalosaurus, Cetiosaurus, Compsognathus, and a few others known at that time, have a simple pelvis structure, with the pubic bone pointing only in the forward direction (see figure 5.3C). These were the “lizard-hipped” dinosaurs, or “Saurischia.”

In the hips of other dinosaurs, such as Iguanodont, Scelidosaurus, Stegosaurus, and a few others known at that time, at least part (if not all) of the pubic bone projected backward, running parallel to the ischium in the hip (see figure 5.3A, B). Seeley called these “bird-hipped” dinosaurs, or Ornithischia, because living birds also have a backward-pointing pubic bone. Within a few years, most paleontologists of the late 1800s and 1900s had adopted these two categories because it seemed that every new dinosaur found fit into one or the other.

As a group, the Saurischia was always problematic. They were defined by having the primitive reptilian hip structure with a forward-pointing pubic bone, a feature seen in crocodiles and other reptiles. Seeley noticed they had a few unique characteristics, such as hollow, pneumatic bones, but he never emphasized these features. In 1986, Jacques Gauthier proposed a few anatomical features in addition to the hip that seemed to unite the Saurischia. But the latest work by Barron, Norman, and Barrett in 2017 argued that theropods and sauropods were not that closely related after all because few unique evolutionary specializations are found in their skeletons (see figure 5.2)—although many paleontologists beg to differ with them. Various scientists have argued either that sauropods are closer to ornithischians (sometimes called the “Phytodinosauria” or “plant dinosaurs”), clustering nearly all the herbivores, or that theropods are closer to ornithischians (the “Ornithoscelida” hypothesis). Thus whether the Saurischia is a natural group is now under question.

The same cannot be said about Ornithischia. The more people look at the group and its members, the stronger the evidence becomes for it being a natural monophyletic group. In addition to their hip condition, ornithischians have another unique specialization: a bone in the tip of their lower jaw forms a beak and is made of a bone called the predentary (because it is in front of the dentary bone that makes up the tooth-bearing part of the jaw). In fact, the presence of this bone is so distinctive and consistent that Marsh called the group the “Predentata” in 1894. Fortunately, Seeley’s name Ornithischia already had priority, or we might be mistaking a group of dinosaurs for a grouping of anteaters, sloths, and armadillos that were long called the “Edentata.”

Beyond the hip structure and the predentary bone, a long list of features confirms the reality of the grouping of ornithischians. The bones at the tip of the upper jaw and snout are usually toothless, and a horny beak probably occluded against the beak on the toothless predentary bone in the lower jaw. In the “eyebrow” area of the eye socket, ornithischians develop a bone called the palpebral, which not found in any other dinosaur. The jaw joint is below the line of the tooth row, which was helpful for the leverage of the jaw needed to chew up plants. Nearly all ornithischians have simple “leaf-shaped” teeth, suitable for cropping vegetation. The tooth rows of most ornithischians are inset deep in the skull, creating a region where fleshy cheeks might have covered the sides of their mouths. This would help keep the food in their mouths as they chewed. Finally, there are ossified tendons all through the backbone, hips, and tail, and in advanced ornithischians, five of the hip vertebrae were fused to the pelvis (primitively, only three were fused in most dinosaurs).

Ironically, the group’s name, Ornithischia, means “bird-hipped” dinosaurs—yet birds are descended from the Saurischia. The earliest relatives of birds have a forward-pointing pubis similar to that of other saurischians, but later in bird evolution the pubis rotated backward, the same condition found in all modern birds. However, birds did not do it in the exact same way as Ornithischia. In addition, recent discoveries have found that weird herbivorous saurischians such as the therizinosaurs and the deinocherids (see chapter 16) also rotated their pelvis backward, but not exactly in the ornithischian manner either. Thus the backward-pointing pubic bone evolved at least three or four times. The ornithischians and therizinosaurs apparently rotated the pubic bone back to allow for a large gut and digestive tract. In birds, the position of the pubic bone is related to the way their skeletons are adapted for flight.

WHENCE ORNITHISCHIANS?

Once the grouping was recognized, paleontologists sorted them into lots of different types of advanced ornithischians: iguanodonts, stegosaurs, ankylosaurs, hadrosaurs, and eventually ceratopsians. But there was no fossil record showing how they were related. Some paleontologists hoped to find fossils that showed how all these diverse groups evolved from a common primitive ornithischian ancestor, and the search was on.

Paleontologists had examples of highly specialized ornithischians, such as stegosaurs, scelidosaurs, hadrosaurs and iguanodonts, but they needed to find primitive dinosaurs with ornithischian features without the specialized armor or jaw features. Naturally, they looked at the relatively generalized ornithischians known as “ornithopods” first. But ornithopods such as Iguanodon had weird specializations, including the thumb spike and the shape of their skull and teeth, so it was not close to the ancestral condition.

One of the early candidates for the most primitive ornithischian was a dinosaur called Hypsilophodon. The first specimens of this creature were found in 1849 on the Isle of Wight on the southern English coast. A group of workers found a block with some vertebrae and limb bones embedded in them (figure 19.1A). To maximize their profits, they sold one half to Gideon Mantell and the other to James Scott Bowerbank. The specimen was so incomplete, however, that its small size led Mantell to identify it as a young Iguanodon when he first saw it. Owen reached the same conclusion in 1855 when he published his own description of the fossil after Mantell had died and it was in the collections of the British Museum.

Figure 19.1

Hypsilophodon foxii: (A) the first specimen, composed of two blocks sold to Gideon Mantell and James Scott Bowerbank, was misidentified as a juvenile Iguanodon; (B) skeleton of Hypsilophodon as it is known today; (C) an 1894 reconstruction by Joseph Smit, making it look both like a quadrupedal lizard and a biped; (D) the Neave Parker reconstruction, based on the mistaken notion that it had a grasping big toe, so it was drawn as a tree-dweller; (E) a modern reconstruction. ([A–D] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [E] courtesy of N. Tamura)

In January 1868, the Reverend William Fox found more specimens from the Isle of Wight locality, including a complete skull and other postcranial bones (figure 19.1B). These were sent to Thomas Henry Huxley, who immediately recognized that the vertebrae matched the Mantell-Bowerbank specimen, but the skull was very different. It was clearly a small adult, not a juvenile, with a relatively short snout and was a much smaller size than an adult Iguanodon. In a presentation in 1869, and then a full paper published in 1870, Huxley called it Hypsilophodon foxii, named after the genus of iguana known as Hypsilophus (now a junior synonym of Iguana) because its teeth resembled that living lizard. The species name honored its discoverer, Reverend Fox. In that same 1870 paper, Huxley was the first to describe the backward-pointing pubic bone, a feature Seeley would use 17 years later to define the Ornithischia. Huxley thought this pubic bone was proof that Hypsilophodon was even closer to living birds than Archaeopteryx, although we now know that the birds are not related to the ornithischians and their backward pubic bones are due to convergent evolution.

More specimens of Hypsilophodon were found over the years: some scholars thought it was quadrupedal, but others argued that it was bipedal (figure 19.1C). The fact that it still had four fingers and four toes (compared to three in Iguanodon and most other known dinosaurs) suggested that it was more primitive, and some thought of Hypsilophodon as being close to the ancestry of ornithischians. One misconception about Hypsilophodon propagated by Hulke in 1874 stated that it had armor on its neck and back, but these bones turned out not to be armor at all. Another mistaken reconstruction of its foot by Othenio Abel in 1912 suggested that it had an opposable big toe like that of a bird, capable of grasping branches. This led to the famous reconstruction by British paleoartist Neave Parker of Hypsilophodon perched in a branch like a bipedal lizard trying to fly (figure 19.1D).

Later research showed this was incorrect, and in most modern reconstructions of Hypsilophodon it appears as a small, fast-running biped with strong hind limbs and relatively small forelimbs (figure 19.1E). It was about 1.8 meters (6 feet) long and weighed about 20 kilograms (44 pounds). It clearly had a beak on the upper and lower jaws, but it also had the recessed tooth row, so most artists give Hypsilophodon cheeks as well. Further analysis in the past decade has found many more specialized features in Hypsilophodon that firmly place it within the Ornithopoda and not ancestral to the entire Ornithischia. It comes from the Early Cretaceous, so its appearance is too late to be an ancestor. The same goes for some of the candidates proposed by others, such as the Early Cretaceous (Purbeck beds of England) jaws called Echinodon by Richard Owen in 1861, or the Upper Jurassic (Morrison Formation) ornithopods Dryosaurus or Camptosaurus described by Marsh in the 1880s. For something more primitive than the Jurassic ornithischians like the primitive scelidosaurs and stegosaurs, we need to go back to the Early Jurassic or even the Late Triassic.

OUT OF AFRICA (AGAIN)

The problem with so many of the potentially ancestral ornithischians is that they were found to be too specialized once we obtained better skeletal material, and nearly all were too late in time. But Triassic beds with the preservation potential for the earliest ornithischians are not that common around the world, and for almost a century after Hypsilophodon was found, they produced nothing that resembled a primitive ornithischian. Other Triassic dinosaurs, prosauropods such as Plateosaurus (chapter 6), primitive theropods such as Coelophysis (chapter 11), and even primitive saurischians such as Herrerasaurus and Eoraptor (chapter 5), were found, but surprisingly few fossils could be called ornithischian. In 1964, French paleontologist Leonard Ginsburg published a description of fragmentary lower jaws and teeth and some other bones from Basutoland (now Lesotho) in southern Africa. From the scraps he had, it looked like a primitive ornithopod jaw with the characteristic leaf-shaped teeth, so it was certainly an ornithischian. Ginsburg named it Fabrosaurus, after Jean Fabre, the geologist who led the French expedition with Ginsburg that found the fossil. Soon every primitive ornithischian in the 1960s was being thrown into a taxonomic wastebasket group called the “fabrosaurids,” even though the original Fabrosaurus fossils were too fragmentary to be identified as one animal. By 1978, paleontologist Peter Galton (who had proposed Fabrosauridae in 1972) realized that the Fabrosaurus fossils were insufficient to diagnose a genus; the Fabrosauridae were not a real group, just a wastebasket for primitive ornithischians. Galton then proposed a new name, Lesothosaurus (“lizard of Lesotho”), for the best new fossils that had once been called Fabrosaurus.

Lesothosaurus is only known from partial skeletal material, but it is clearly a relatively small and very primitive Triassic ornithischian. The skeleton is lightly built and completely unspecialized, with delicate arms and legs and a slender tail. It reached a total length of about 2 meters (6.6 feet), counting the long tail. The skull was not completely primitive, having leaf-shaped teeth, the predentary bone, and evidence of a horny beak on the upper and lower jaws as seen in all ornithischians. It also had the palpebral bone in the eyebrow but does not have the recessed cheek tooth row seen in more advanced ornithischians, suggesting that it didn’t have cheeks.

The specimen is still pretty fragmentary and poorly preserved in key areas, so its relationships are controversial. It was originally considered to be a more specialized ornithopod. Paul Sereno considered it one of the most primitive ornithischians known, but in 2005 Richard J. Butler argued that it was a much more advanced creature, close to the ancestry of the ornithopod-ceratopsian branch. A 2008 study by Butler, Upchurch, and Norman placed it near the base of the stegosaur-ankylosaur branch of ornithischians. This is not surprising for such an incomplete and confusingly primitive fossil in which just a few anatomical features can radically change its position on the family tree.

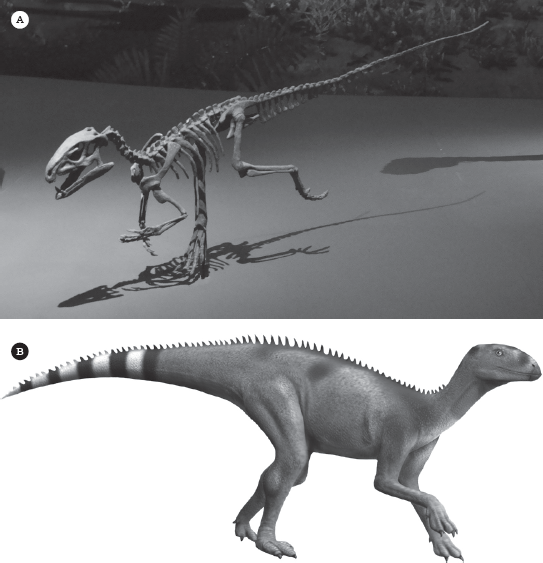

So far, all the possible candidate fossils were too young, too specialized, or too fragmentary to tell us much about the origin of ornithischians. But one fossil does not suffer from these handicaps. During the winter of 1961–1962, a group of British paleontologists combined with South African colleagues to lead an expedition to the interior of South Africa, especially Lesotho (where Lesothosaurus was found much later). Paleontologists Alan Charig of the British Museum and A. W. “Fuzz” Crompton of the South African Museum found a well-preserved fossil skull that was clearly from a very primitive ornithischian. It had the predentary bone and toothless lower beak in front, the palpebral bone in the eyebrow, and columnar chisel-like plant-eating cheek teeth that were slightly inset, suggesting a set of cheeks. However, it had its own specializations in the teeth, including a set of fang-like canine teeth in the snout just behind the toothless beak, plus incisor-like teeth in front of the tusk. These three different types of teeth are extremely unusual for any dinosaur, so Charig and Crompton named it Heterodontosaurus (different toothed lizard) in 1962. In 1974, Crompton, Charig, and their field crew also found a beautiful articulated nearly complete skeleton in its death pose (figure 19.2), also from Lesotho. It clearly showed that Heterodontosaurus had long arms with five-fingered hands with curved claws, and even longer leg bones. The hind foot had four toes, primitive for all dinosaurs, and not the three seen in more advanced ornithischians. The thighbone was relatively short, but the shinbone was long, as were the ankle and toe bones. This showed Heterodontosaurus was a fast, bipedal runner, running with its body horizontal and balanced by its long tail. The complete skeleton and other specimens show that Heterodontosaurus was 1.18 meters (3.9 feet) to 1.7 meters (5.7 feet) long and weighed 1.8 kilograms (4 pounds) to 10 kilograms (22 pounds).

Figure 19.2

Heterodontosaurus: (A) complete articulated skeleton from the Triassic of Lesotho; (B) reconstruction of the head in life. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

In nearly all respects, Heterodontosaurus provides a good image of what the earliest ornithischians were like. About the only specialization unique to Heterodontosaurus and not found on later dinosaurs were the weird tusks, or fangs, in the mouth. Other skulls have been found with no tusks, so the presence or absence of tusks may be an example of sexual dimorphism, a difference between males and females, or these tuskless specimens may not be Heterodontosaurus at all. In addition, even juvenile specimens seem to have large tusks, so it is a feature of the genus.

The specimen was crucial in many ways. Not only was it the best primitive ornithischian fossil ever found, but it showed the kind of anatomy that was the starting point for the evolution of all other groups of ornithischians, without the problems that plagued incomplete specimens like Lesothosaurus, Fabrosaurus, and other primitive forms.

Its discovery also came at a crucial time during the Dinosaur Renaissance. Until then, most paleontologists doubted that Saurischia and Ornithischia were closely related, or that Dinosauria was a real, natural group of organisms. They thought that saurischians and ornithischians had independently evolved from different lineages within the thecodonts. The cladistic revolution that established the common ancestry of all dinosaurs was still on the horizon, but a 1974 paper by Peter Galton and Bob Bakker pointed out just how many uniquely dinosaurian features could be seen in a good fossil such as the complete Heterodontosaurus, especially in the wrist and ankle. (John Ostrom was coming to the same conclusion independently.) They argued that the Dinosauria was clearly a natural monophyletic group, not an artificial assemblage of saurischians and ornithischians that evolved independently from the thecodonts and were arbitrarily called dinosaurs. That conclusion was supported by John Ostrom in the 1970s and 1980s and confirmed by the cladistic analysis published by Jacques Gauthier in 1986.

HETERODONTOSAURS EVERYWHERE

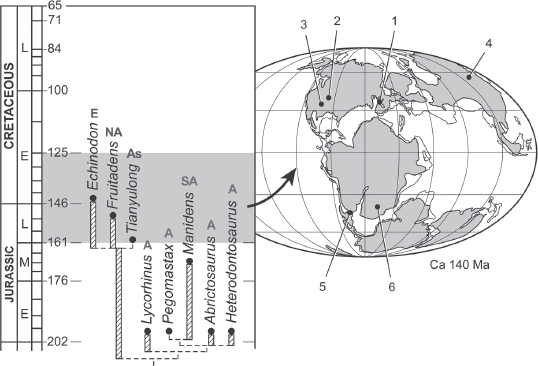

Even though the genus Heterodontosaurus is known from just a few specimens, and primitive ornithischians are rare in Triassic and Jurassic beds worldwide, their diversity has increased as more and more fossils have been discovered around the world. Numerous other genera of heterodontosaurines are found in the Late Triassic or Early Jurassic of southern Africa, including Lycorhinus, Pegomastax, Abrictosaurus, plus Manidens from Chubut Province in Argentina (figure 19.3). In addition to these members of the subfamily Heterodontosaurinae, more primitive members of the family Heterodontosauridae include Echinodon from the Lower Cretaceous beds of England (first named and studied by Richard Owen in 1861); Fruitadens from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation in the Fruita area near Grand Junction, Colorado; and Geranosaurus from the Early Jurassic of South Africa.

Figure 19.3

The family tree and geographic distribution of heterodontosaurs. (Courtesy of P. C. Sereno)

The most interesting new heterodontosaur is Tianyulong from China, which is preserved in fine-grained lake shales, so the soft tissues are intact (figure 19.4). This fossil shows that some heterodontosaurs had a covering of long filamentous fibers similar to bristles (and possibly homologous with the primitive Type 1 feathers of Prum and Brush), especially along their back and sides. They were arranged almost like the spines of a porcupine along the back. Sereno actually described Tianyulong as a “nimble two-legged porcupine.” This specimen, plus a number of others including Psittacosaurus, show that feathers were found across the entire Ornithischia, and most dinosaurs in both branches were probably feathered in some way. Added to the other primitive ornithischians, such as Lesothosaurus, plus the primitive relative of ankylosaurs and stegosaurs known as Emausaurus, the outlines of the diversification of the major groups of ornithischians by the Early Jurassic is becoming better and better understood.

Figure 19.4

(A) Complete specimen of Tianyulong from the Lower Cretaceous Liaoning beds of China. Boxes frame the muzzle, hand, feet, and tail. (B) Life-sized model of Tianyulong. ([A] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [B] photograph by the author)

Finally, there is an even more primitive fossil from the lower Upper Triassic Ischigualasto Formation of Argentina, source of Herrerasaurus and Eoraptor. Discovered in 1962 by Galileo Juan Scaglia, it was named Pisanosaurus (figure 19.5) by R. M. Casamiquela in 1967, in honor of Argentine paleontologist Juan Arnaldo Pisano of the La Plata Museum. It was later redescribed by José Bonaparte in 1976. Although it is missing its tail and the pelvis is too broken to determine whether the pubic bone pointed backward, several features of the skull suggest that Pisanosaurus might be the most primitive ornithischian ever found. It is probably a dinosaur, and not a more primitive archosaur, because the hip socket is perforated. The lower jaw has a predentary bone, an inset row of herbivorous teeth, and it has a very low jaw joint, all ornithischian features. The top of the skull is missing, so we do not know if it had a palpebral bone in its eyebrows. These missing features leave it open to lots of confusion and to different interpretations: it has been called a heterodontosaurid, a hypsilophodontid, a fabrosaurid, or the earliest known ornithischian. Some would put it just outside the Dinosauria and within the silesaurids (see chapter 5). We will probably never be able to resolve this with the known specimens to date.

Figure 19.5

Pisanosaurus: (A) reconstructed skeleton; (B) artistic reconstruction of the dinosaur. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

We now have a solid and improving fossil record of the earliest evolution of ornithischians. The remaining chapters focus on the major groups of ornithischians that evolved by the later Jurassic and came to dominate herbivore faunas through the Cretaceous.

FOR FURTHER READING

Baron, Matthew G., David B. Norman, and Paul M. Barrett. “A New Hypothesis of Dinosaur Relationships and Early Dinosaur Evolution.” Nature 543 (2017): 501–506.

Bonaparte, José F. “Pisanosaurus mertii Casamiquela and the Origin of the Ornithischia.” Journal of Paleontology 50, no. 5 (1976): 808–820.

Butler, Richard, Paul Upchurch, and David Norman. “The Phylogeny of Ornithischian Dinosaurs.” Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 6, no. 1 (2008): 1–40.

Colbert, Edwin. Men and Dinosaurs: The Search in the Field and in the Laboratory. New York: Dutton, 1968.

Farlow, James, and M. K. Brett-Surman. The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999.

Fastovsky, David, and David Weishampel. Dinosaurs: A Concise Natural History, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Holtz, Thomas R., Jr. Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. New York: Random House, 2011.

Naish, Darren, and Paul M. Barrett. Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2016.

Norman, David B., Hans-Dieter Sues, Lawrence M. Witmer, and Rodolfo A. Coria. “Basal Ornithopoda.” In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed., ed. David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, and Halszka Osmólska, 393–412. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Seeley, Harry Govier. “On the Classification of the Fossil Animals Commonly Named Dinosauria.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 43 (1888): 165–171.

Sereno, Paul C. “Phylogeny of the Bird-Hipped Dinosaurs (Order Ornithischia).” National Geographic Research 2, no. 2 (1986): 234–256.

——. “Taxonomy, Morphology, Masticatory Function, and Phylogeny of Heterodontosaurid Dinosaurs.” ZooKeys 226 (2012): 1–225.

Weishampel, David B., and Lawrence M. Witmer. “Heterodontosauridae.” In The Dinosauria, ed. David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, and Halszka Osmólska, 486–497. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

Zheng, Xiao-Ting, Hai-Lu You, Xing Xu, and Zhi-Ming Dong. “An Early Cretaceous Heterodontosaurid Dinosaur with Filamentous Integumentary Structures.” Nature 458, no. 7236 (2009): 333–336.