Ingredients

Baking is the ultimate form of pantry cooking. Many baked goods start with a core of the same modest and affordable ingredients—flour, butter, sugar, and eggs—with few obscure additions. If you always have these basics on hand, you can make a vast assortment of recipes, from cookies to layer cakes, with no last-minute grocery runs.

To me, the ingredients that follow are the essentials. Of course, the more you bake, the more your pantry will reflect preferences for particular spices or flavors, but certain items are staples in every baker’s kitchen.

More and more people have started paying close attention to the quality and contents of their food—a good thing—and with that come increases in alternative diets, like vegan and gluten-free, for reasons both practical and political. These diets obviously require pantry substitutions. Beyond that, buying the best ingredients you can comfortably afford is a good rule of thumb.

Baking staples are generally inexpensive, but it’s worth splurging on a few things. The differences in taste and complexity between low and high (or at least decent) quality chocolate (or cocoa powder) are huge. Good eggs, butter, and milk—as well as any flavoring like spices and real vanilla—also make a difference in the overall quality of your final product, so invest in those if you can afford to.

Beyond those key ingredients, it’s typically less about taste than about values. You are unlikely to be able to taste the difference between a brownie made from conventional flour and one made from organic flour milled on a small farm, but the second supports values that are better for our food system both long- and short-term. Whenever it’s possible and practical, consider supporting products—like dairy, chocolate, produce, or even flours—that are fair-trade, small-batch, local or regional, organic, and so on.

THE BASICS OF FLOUR

The backbone of all baking is flour—specifically wheat, although nowadays you can find flours made from all kinds of other grains and even nuts. All-purpose flour is the standard in most recipes, but the type of flour you choose can dramatically change a dish’s flavor and/or texture. In the days, not long ago, when “flour” meant “wheat,” protein content was the most important variable; the higher it is, the chewier and less delicate the end product, which is good for breads and sometimes even cookies, but not for cakes and pastry.

Here, then, are the primary flours you’ll need for baking, plus a few more if you want to experiment further, and plenty of information about how best to use them all. See Substituting Flours in Baking and Gluten-Free Baking for more of the nitty-gritty on making substitutions.

THE FLOUR LEXICON

WHITE FLOURS

A wheat kernel is made up of three parts: endosperm, bran, and germ. There are multiple varieties—hard and soft, spring and winter, red and white—all of which influence the flour’s color and its gluten content. White flour is milled from the starchy endosperm of soft wheat varieties, which makes it soft and fine. Use only unbleached flour; bleaching uses harsh chemicals (it’s actually illegal in some European countries), and is purely cosmetic. And unbleached flour itself is still white, so it will give your baked goods the same look and taste you expect.

ALL-PURPOSE FLOUR This is the workhorse of flours and truly all-purpose; with 8 to 11 percent protein, it covers all the bases. (If the protein content is not listed on the label, just check the number of grams of protein in the nutritional information; since that’s listed per 100 grams of flour, it’s a percentage. So 8 grams of protein means the flour is 8 percent protein.) Some brands may be enriched with vitamins and nutrients in an attempt to compensate for those that are stripped through the removal of bran and germ.

BREAD FLOUR Although it looks and can taste exactly the same as all-purpose, bread flour has more protein—up to 14 percent—which translates to more gluten. This makes it the flour of choice for elastic, easy-to-handle yeast bread doughs that produce chewy crumb and sturdy crust. It’s also a great cup-for-cup substitute for up to half of the all-purpose flour in recipes where you might prefer extra chewiness, like cookies or brownies. Check the label—avoid brands that are “conditioned” with ascorbic acid, which can make the finished product taste slightly sour.

CAKE AND PASTRY FLOURS Softer and more delicate than all-purpose (pastry is 8.5 to 9.5 percent protein; cake is 7 to 8.5 percent), these don’t develop much elasticity in doughs or batters; you get a tender, delicate crumb in cakes and pastries; there are instances in which these are really beneficial, and I note them. If you don’t have any or can’t find it, measure a level cup of all-purpose—see this illustration for the proper way to measure flour—then remove 2 tablespoons and replace with cornstarch.

SELF-RISING FLOUR Also called phosphated flour. This is essentially all-purpose flour plus salt and baking powder. It’s a silly concept, since it’s more expensive and cannot substitute for all-purpose flour; furthermore, it’s easy enough to add those two ingredients to regular flour. Skip it.

WHOLE WHEAT FLOURS

These are milled from all three components of the kernel of hard red wheat—the bran, the germ, and the endosperm. The bran and germ contribute more fiber and nutrients, up to 14 percent protein, as well as a brown color (less so with white whole wheat, below) and pleasantly nutty, wheaty flavor. For those of us who grew up eating white bread, whole wheat is a bit of an acquired taste, and anything made with 100 percent whole wheat flour is heavier and denser than its counterpart made with white flour; a combination is often ideal. Generally, you can use any whole wheat (see varieties below) to replace white flour in almost any recipe without making other adjustments.

WHITE WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR Milled from white wheat instead of red, this is milder (and, obviously, lighter in color), and perfect for people who don’t like the strong flavor of conventional whole wheat flour but want the nutritional advantage. As with other whole wheat flours, most baked goods made with it are on the heavy side, although a little less so.

WHOLE WHEAT PASTRY FLOUR Milled from soft wheat, like its white counterpart, but includes bran and germ. Think of it as a hybrid: It produces a light crumb similar to what you’d get with white pastry flour, but with the characteristics of whole wheat, including nuttier flavor and slightly heavier, denser results. The rules for regular whole wheat flour apply here: Substitute it for only 50 percent of the cake or pastry flour in any recipe and expect the results to be a little less delicate, with more pronounced wheat flavor.

NONWHEAT FLOURS

Nonwheat, or “specialty” flours, are increasingly popular for both gastronomic and nutritional reasons. They come from other grains, nuts, legumes, or vegetables, any of which can be ground or milled into a powder. While some contain gluten, none have as much as wheat, so they’ll create different results and shouldn’t be treated interchangeably (see The Truth About Gluten for more info). But it’s easy enough to work them into your baking rotation, as long as you do so mindfully. This list is not comprehensive but includes the nonwheat flours I actually do use. For guidance about how to substitute them in recipes, see this chart.

RYE FLOUR Closely related to wheat but with more assertive, distinctive flavor and very little gluten. Rye flour is graded dark, medium, or light, depending on how much bran is milled out of the berries: the darker the flour, the stronger the flavor and the higher the protein and fiber. Any can be a good substitute for a small amount—up to 20 percent, say—of wheat flour. Even if you don’t use much, baked goods made with rye flour tend to be moist, dense, deeply colored, and slightly (deliciously) sour tasting. (Don’t try it for the first time in a cake!) Pumpernickel flour is made from whole grain rye berries and is coarser than dark rye flour, and makes a delicious addition to many breads.

BUCKWHEAT FLOUR Most commonly used in pancakes, waffles, blintzes, crêpes, muffins, and noodles, and distinctive in all. As with rye flour, the darker the color, the stronger the flavor. And, as with rye, it’s slightly sour. The plant itself contains no gluten, but the flour is often milled with wheat, so check the label to see whether it’s low in gluten or truly gluten-free.

CORNMEAL AND CORN FLOUR Ground dried corn, available in fine, medium, and coarse grinds and in yellow, white, and blue, depending on the corn. Coarser grinds are more texturally interesting, a little crunchy and a little chewy—these make good corn bread. All can be used interchangeably, unless otherwise specified in the recipe, and are gluten-free as long as they’re 100 percent corn. Stone-ground cornmeal—which is what you want—retains both the hull and the germ, so it’s more nutritious and flavorful than common steel-ground cornmeal, although also more perishable; store it in the freezer. And try it for more than corn bread; it imparts that mildly sweet flavor to breads, pancakes, pie and tart crusts, and even some cakes.

Corn flour is another name for finely ground cornmeal, but be careful: In recipes written in the UK it means cornstarch, a thickening agent. To make corn flour, grind medium or coarse cornmeal in a food processor for a few minutes.

SPELT FLOUR Spelt is related to wheat, with a pleasant, nutty, mildly sweet flavor; it may be a good wheat substitute for people who can tolerate gluten but are allergic to wheat. It’s high in protein, with some gluten for structure but a light enough crumb that you can start by subbing it for up to half of the wheat flour in a recipe. Comes in white and whole grain varieties.

RICE FLOUR Sometimes called rice powder or cream of rice, this is made from hulled, ground, and sifted rice. White rice flour, like white wheat flour, is processed to remove the bran and germ, so it’s mild-flavored. Brown rice flour has had only the outer husk removed, so it’s higher in protein, fiber, and other nutrients and nuttier in flavor. Both have slightly grainy, gritty textures, which some people enjoy, particularly in dishes like piecrust or waffles, where a bit of crunch can be good. It’s best to combine them with other flours, especially when you first start using them. Glutinous (sweet) rice flour is entirely different, producing a stickier texture for things like mochi. Despite its name, it—like all rice flours—is gluten-free.

NUT FLOURS Made by finely grinding nuts, nut flours (or nut meals) are gluten-free and high in protein, fat, and, of course, flavor. Almond flour is the most widely available, with a consistency that resembles cornmeal. Nut flour can also be made with hazelnuts, walnuts, pecans, or pistachios (see the box above to make your own). Generally, you can substitute these for up to 25 percent of the wheat flour in a baking recipe without making other adjustments, but they contribute very little structure on their own, which is why they’re typically paired with other flours and/or egg whites. The oils released during grinding can turn rancid, so store extra in a plastic zipper bag in the freezer.

Use this chart as a quick reference for replacing a portion of the all-purpose or bread flour in your baked goods. You can mix and match, but don’t go over the maximum percentage for any one flour; if you need or want to avoid wheat entirely, see Gluten-Free Baking.

If you want to steer clear of math, put the estimated amount of alternative flour (or flours) in the measuring cup first, then fill the remainder with all-purpose wheat flour and level it off. Err on the more conservative side for anything that needs more structure, like cakes or cookies; you can be more liberal with the substitutions for things like piecrusts, crackers, or pancakes.

FLOUR |

QUANTITY TO SUBSTITUTE IN RECIPES (BY VOLUME) |

Whole Wheat |

Up to half |

Rye |

|

Buckwheat |

Up to one-quarter |

Cornmeal |

Up to one-sixth |

Spelt |

Up to all; then either decrease the total water/milk by one-quarter or increase the flour by one-quarter |

Rice |

One-quarter to one-third |

Nut |

One-quarter to one-third |

Oat |

One-quarter to one-third |

Soy |

Up to one-quarter |

Bean |

One-quarter to one-third |

Sorghum |

Up to half |

OAT FLOUR Like rolled oats, this gives baked goods a moist, crumbly texture and nicely nutty-tasting flavor. You can grind your own by giving rolled oats a whirl in the blender or food processor; just know that it won’t be super-fine. Most oat flours are not gluten-free, because gluten can sneak in during the growing or processing if the oats are grown alongside wheat or the factories also process wheat; check the label and assume it’s not unless specifically stated.

SOY FLOUR Made from roasted soybeans, this has a noticeable bean flavor that makes it best in savory baking, and even then, not everyone likes it (I’m not wild about it myself). You can find it full-fat (sometimes called “natural”), which retains the natural oils, or defatted. Both are high in protein and gluten-free, but you should swap it for only 25 percent of the flour in most baking recipes and expect dense, moist results.

BEAN FLOUR Typically ground from dried chickpeas and/or fava beans; like soy flour, this is gluten-free and high in protein with a strong flavor; in some recipes, it’s mandatory (see Socca). If you want to experiment with it, swap it for one-quarter of the flour in a savory recipe, especially those from south Asia or the Mediterranean.

SORGHUM FLOUR Sorghum is a grass plant that produces both grain and a syrup similar to molasses. The flour tastes and feels like wheat flour—mild yet sweet—but is gluten-free, so it’s a great candidate for experimenting. Try subbing for up to half of the all-purpose flour, or even more for things like pancakes that don’t require too much structure.

POTATO FLOUR Made from whole potatoes that are dried, then ground. (Don’t confuse it with potato starch, which is a lot like cornstarch.) Too much will add an obvious potato flavor and can make your food gummy, but when it’s blended with other gluten-free flours, particularly relatively dry flours like rice, it can add incredible moisture and depth, particularly to breads and any recipe that isn’t too sweet.

TAPIOCA FLOUR Also known as tapioca starch, this comes from the root of the cassava plant. Because it’s so starchy, it shouldn’t be used as a flour substitute, but small amounts—just 10 percent or so—are great in gluten-free flour blends because it contributes good texture. Also great as a thickening agent for sauces and fillings; teaspoon for teaspoon, you can use it as a cornstarch substitute.

THE BASICS OF SUGAR AND OTHER SWEETENERS

There are many kinds of sweeteners, some with their own distinct flavor or consistency (think: honey) and others that blend in seamlessly with the rest of your ingredients (like sugar, which is pretty much one-dimensionally sweet). Since they’re naturally quite shelf stable, you can easily stock your pantry with a wide range.

GRANULATED SWEETENERS

The easiest to use, measure, and store because they’re dry. The most ubiquitous option is white sugar, but there are other options that taste different and perform differently.

WHITE SUGAR The most common granulated sugar, made from sugarcane or sugar beets; highly refined, cheap, convenient, and effective, with a neutral flavor that won’t outshine other ingredients. White sugar comes in various granule sizes and types, each with its optimal uses, but granulated sugar is the equivalent of all-purpose flour: You can use it almost everywhere when recipes call for sugar. The grains are medium size and dissolve well when heated or combined with liquid. There are several other forms of white sugar:

BROWN SUGAR Brown sugar is granulated white sugar with molasses added for moisture and a more complex taste. It can be light or dark, depending on how much molasses has been added. In a pinch, you can make brown sugar by stirring or beating a tablespoon or more of molasses into a cup of white sugar; beating it helps ensure that it’s fluffy and easy to work with. Always pack brown sugar into a measuring cup to eliminate pockets of air and get an accurate measure.

Dark brown sugar is more intensely flavored, but the difference is subtle, and I use light (sometimes labeled “golden”) and dark interchangeably. In most dessert recipes, you can substitute brown sugar for white cup for cup, as long as you remember the color and flavor will be different. To keep brown sugar from hardening, put it in a plastic bag, press out any excess air, and put the bag in a tightly sealed container and refrigerate. To soften rock-hard brown sugar, put it in a heatproof bowl, top with a damp paper towel, and microwave it in 15-second intervals, just until it is loose again; use it immediately. Alternatively, you can grate the hardened rock of sugar on a fine cheese grater.

RAW SUGAR Made from sugarcane in a couple of different ways, these coarse-grained brown or golden sugars taste less sweet than more heavily processed sugars and have a distinctive caramel flavor. You can use raw sugar in place of white sugar in many recipes, provided the grind is fine (you can grind it finer in a spice grinder or food processor easily enough) or the cooking time is long enough to dissolve it completely; as with substituting brown sugar, don’t expect identical results. I like it best sprinkled on top of baked goods like scones and cookies to add a mildly sweet crunch. Here are the most common raw sugars:

OTHER GRANULATED SWEETENERS You might have heard about evaporated cane juice (which comes from sugarcane) or coconut sugar (from the sap of the flowers of the coconut palm tree), which are comparable to light brown sugar in color and flavor. Both sound moderately wholesome (they’re only negligibly more so than white sugar) and are growing increasingly popular, albeit more so in packaged foods than as standalone ingredients. It’s fine to use either if you come across them; just don’t let yourself think they’re anything other than sugar by a different name.

Fructose, a simple sugar found in honey, fruit, berries, and some root vegetables, is often recommended to diabetics because it is metabolized differently than cane sugar. But it’s super-concentrated and loses power when heated or mixed into liquids, so it’s tricky to use; I don’t bother with it.

Nor do I recommend baking with zero-calorie sweeteners, like saccharin, sucralose, xylitol, and aspartame, which at best taste funny and at worst might be hazardous to your health—even the “natural” ones, like stevia. They can also be two hundred times sweeter than sugar, so it’s tricky to substitute them since you have to account for all the lost bulk. Their use should be considered only by diabetics, and even then carefully.

LIQUID SWEETENERS

These dissolve faster than sugar and can bring distinctive flavors to baked goods, but they are not directly interchangeable with each other or with granulated sugars.

HONEY There are more than 300 varieties of honey in the United States alone, including orange blossom, clover, and eucalyptus, and the good ones are all distinctive. Most commercial honeys are blends, and less exciting; but in any case, make sure you’re buying 100 percent pure honey and not flavored corn syrup. Honey never goes bad, but it may crystallize; to fix that, remove the top of the container, place it in a bowl of very hot water, and stir every 5 minutes until the honey reliquefies. (A microwave will work also, but be careful to use low power and very short bursts.)

Honey is about 25 percent sweeter than white sugar, so you would use less of it to achieve the same sweetness. But replacing sugar with honey can be tricky; cookies made with honey, for example, spread more than those baked with sugar. Start by replacing a small amount of the sugar in your favorite recipe (bearing in mind that the color of honey will darken food slightly) and see what happens. Some other guidelines for baking with honey:

MOLASSES A heavy syrup produced during the sugar-making process. The first boiling produces light molasses, which can be used like honey; the second produces dark molasses, which is thick, full flavored, and not so sweet; and the third produces blackstrap molasses, the darkest, thickest, and least versatile of the bunch. You can cook and bake with blackstrap, particularly in things like quick breads that don’t need a ton of sweetness to begin with, although it’s best to blend it with light molasses or honey.

MAPLE SYRUP Made from the sap of maple trees, maple syrup is the most American of sweeteners. Colonial-era settlers used it to make desserts like Cornmeal Pudding; today it’s a favorite topping for pancakes and waffles. Use real maple syrup, never imitation, which is just flavored corn syrup; there is no comparison.

Maple syrup varies in color and flavor, depending on the time of year when it’s collected. There’s a grading system that’s meant to help you choose, although it often causes confusion. Until relatively recently, it consisted of Grade A (Fancy, Medium Amber, or Dark Amber), Grade B (darker, thicker, with a stronger flavor), and Grade C (darkest, with the most pronounced flavor; this was usually not sold retail). Now, it’s all Grade A—rendering the grade meaningless—but accompanied with descriptors. Grade A, Fancy, is now Grade A, Golden Color with Delicate Taste; Grade B is now Grade A, Very Dark with Robust Taste. Whatever you call it, the thicker, darker syrup is better for baking since its flavor is more pronounced.

CORN SYRUP Not to be confused with the controversial high-fructose version, which isn’t sold in supermarkets; this is a thick, sticky sweetener processed from cornstarch. Light corn syrup is clarified; dark is flavored with caramel, which makes it sweeter and, yes, darker. Neither contribute much in the way of flavor, but they’re useful for getting the right consistency in traditional Pecan Pie, Caramels, and some other candies and sauces like Hot Fudge.

AGAVE NECTAR More accurately called agave syrup—it’s processed from the starch of the agave plant’s root bulb. It has a little more flavor than corn syrup but isn’t as assertive as honey. You can substitute it for no more than half the granulated sugar in a recipe; for every cup of sugar, use only ⅔ cup agave nectar and reduce the other liquids in the recipe by ¼ cup.

THE BASICS OF BUTTER AND OTHER BAKING FATS

Fat, in some form or another, is the most important ingredient in many desserts, adding both flavor and tenderness. There is no good reason to reduce fat in recipes, but there are plenty of low-fat alternatives throughout the book, particularly fruit- and meringue-based recipes.

BUTTER

By far the most popular baking fat and my preference for almost everything, butter is an emulsification of about 80 percent butterfat with water and milk solids. In addition to having an unbeatable flavor, it contributes texture in a variety of ways. When it’s softened and beaten with sugar, it holds on to air for a light, fluffy texture; gently worked into piecrusts and pastries, it melts and creates steam, resulting in flaky layers; when more thoroughly worked into “short” doughs like tart crusts or shortbread, it gives a crumbly, sandy texture; and when melted, it creates a moist, chewy batter for brownies and some cookies.

Use unsalted butter exclusively. Salt is incorporated into butter largely as a preservative, which means salted butter may sit around longer than unsalted (also called sweet) butter before it’s sold. Since butter freezes well, and since salt is an ingredient you can add anytime, there’s no reason to buy salted. (If you do buy salted butter, eliminate added salt from your recipe.) Buy the best you can find and afford; good, fresh butter is an affordable luxury.

“European-style” butter, made with cream that’s cultured before churning, is becoming increasingly common. It has a more assertive flavor and higher fat content than standard butter; substitute it freely, and expect better results.

Many recipes call for butter at specific temperatures, because it behaves differently depending on its state. Here’s a rundown:

LARD

Lard, once the baking fat of choice, is finally back in style. (Health-wise, it’s equivalent to butter and better for you than most margarines.) It’s fantastic in pie and tart crusts and some pastries; use, for example, one part lard with three parts butter for the best piecrust you’ve ever tasted.

OILS

Any oil can be used in place of butter, but there will be significant differences in flavor and texture. Oils create moisture, so they retard staleness, but by themselves they don’t add loft as butter does. They work best in quick and yeast breads, muffins, and brownies, where rise comes from leavening like baking powder or yeast, but not so well in most cakes. Having said that, some oils—like olive and nut oils—have good (and distinctive) flavor that can be lovely in some cakes and pastries, as long as you’re looking to highlight that flavor, not hide it. If you want to use oil with a milder flavor, try high quality grapeseed, which is quite neutral.

Store all oil in airtight, preferably dark containers that don’t get hit with direct sunlight—the pantry is great, or even the fridge—and always check for freshness before using; if they smell rancid or metallic, toss them. (This is true not only in baking but in all cooking.)

If you’re looking for a solid, spreadable fat—something to cream with sugar, for example—coconut oil is your best bet. It’s solid at room temperature, although it melts quickly; for best results, premeasure and freeze it until right before use.

Vegetable shortenings and margarine, made with oil but solid like butter, function like butter or coconut oil, but their flavor is neutral at best and greasy or foul at worst. Don’t use them.

THE BASICS OF EGGS

The egg is a baking powerhouse: No other single ingredient adds flavor, tenderness, structure, lift, and binding as effectively. Some recipes call for whole eggs; others call for only the white or the yolk, and both white and yolk are so versatile and essential that you could consider them separate ingredients.

The white—or albumen—comprises about two-thirds of the egg (usually about 2 tablespoons) and over half of the egg’s protein and minerals. It has no notable flavor of its own, but the proteins trap and hold air. Beating them makes them inflate exponentially, giving the signature airiness and lift to meringues, sponge cakes, mousses, and soufflés.

The yolk contains all the fat, plus zinc, the majority of the vitamins, and the remaining protein and minerals. It adds a luxurious creaminess to baked goods and has a distinctive flavor that you can choose to highlight, as in custards, or allow to remain in the background. A blood spot in the yolk is not harmful (nor does it mean you have a fertilized egg) but is a vein rupture, actually indicating a fresher egg (the older the egg gets, the more diluted the blood spot becomes). If it bothers you, remove it with the tip of a knife.

BUYING AND STORING EGGS

Eggs come in different sizes based on weight. Extra-large and large eggs are most common, and most recipes, including mine, assume large eggs, although you can freely substitute extra-large with no detectable consequences.

The color of the shell varies depending on the breed of hen and has no bearing on the flavor, quality, or nutritional content of the egg. There are lots of other ways to label eggs, some of which matter, but most claims (free-range, natural, cage-free, vegetarian-fed . . . ) are unregulated, and therefore meaningless and misleading enough to be essentially useless. If you can get eggs produced by a local farmer, especially one whose practices are open, do so—they often have better flavor and vibrant orange yolks that can even add rich color, and it’s the best (often, the only) way to be an informed, conscientious consumer. Otherwise, USDA Certified Organic is as safe a bet as any.

Most cartons feature a seemingly arbitrary 3-digit number right next to the sell-by date. This is actually the pack date: Days of the year are ordered, 1 through 365, so that January 1 is 001 and December 31 is 365. It’s a small headache (and usually unnecessary) to mentally compute, but if you’re not sure of the eggs’ freshness, you can use it as a benchmark, since properly refrigerated eggs will keep for four to five weeks beyond the pack date. Before buying, take a quick peek inside the carton to make sure all the eggs are sound and check that the sell-by date has not passed.

Although in most baked goods it’s a non-issue, in a few desserts such as mousse or meringue (or raw cookie dough), eggs are not fully cooked; since raw eggs can carry foodborne illnesses like Salmonella, it’s good to be mindful of this, especially when cooking for children, pregnant women, people of old age, or anyone with a weakened immune system. A good option if you want to be extra-careful are pasteurized eggs in the shell. Like pasteurized milk, these are gently heated to kill any bacteria but are still raw. Note that they aren’t available everywhere and are more expensive than others, so you’ll want to plan ahead if you need them.

Separating Eggs

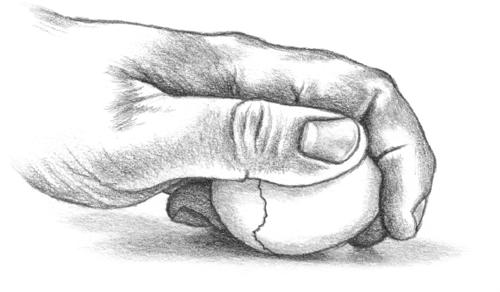

Step 1

To crack the egg, smack the side definitively—but not too aggressively—on a flat, hard surface, stopping your hand when you hear the shell crack.

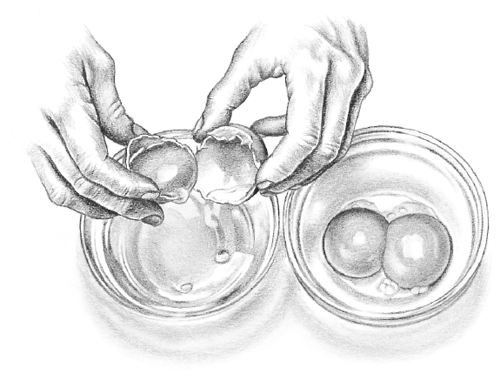

Step 2

The easiest way to separate eggs is to use the shell halves, moving the yolk back and forth once or twice so that the white falls into a bowl. Be careful, however, not to allow any of the yolk to mix in with the whites or they will not rise fully during beating.

POWDERED EGGS You can find dehydrated whole eggs and egg whites in easy-to-use powders that, when reconstituted with water, serve all the same functions—binding, moistening, leavening—as their fresh counterparts, with a very similar texture. I prefer fresh whole eggs since they’re so easy to keep around anyway, but powdered whites are particularly useful for making meringues and anywhere you’d otherwise be left with extra yolks. Since they’re pasteurized, they’re also safer for use in raw recipes like Royal Icing. Powdered eggs are shelf-stable, so you may just want to keep them on hand to use in a pinch. Follow the package directions for reconstituting and use them as a one-for-one substitute. All that said, their flavor isn’t as good, so it’s best to stick with fresh eggs for custards and other recipes where the eggs’ flavor should stand out.

I do not recommend meringue powder—which combines egg whites with sugar, cornstarch, and sometimes other stabilizers and preservatives—since each brand varies and you can’t be sure how it’ll impact your recipes until they’re out of the oven.

BAKING WITH EGGS

For most things, you can just take an egg straight from the fridge and crack it into your bowl. Room temperature eggs are a little easier to beat, but this is only important when they need to hold as much air as possible, as in meringues. (I’ll let you know when you need to take this extra step.) A fast and safe way to bring eggs to room temperature is to soak them in a pan of warm (not hot) water for 5 to 10 minutes.

It’s easiest to separate eggs when they’re cold. Start by setting out two bowls, one for yolks and one for whites. Gently tap the side of the egg on a flat, hard surface or the edge of a bowl to make a clean crack along the center of the shell, then pull it apart into halves. Transfer the yolk back and forth or crack the whole thing into your cupped palm, and let the white drip into one of the bowls, taking care that the yolk doesn’t break. (A bit of yolk will make it impossible for the whites to gain maximum volume.)

See tempering eggs and beating eggs.

THE BASICS OF CHOCOLATE

Like coffee and wine, you can spend too much time thinking about chocolate. I approach all these things similarly: I look for a delicious product of the highest quality I can afford and find without hassle. In a way, chocolate is simple: if it’s inviting when you bite into it, it’s good enough for cooking. This is why I generally avoid chocolate chips and premade sauces; they’re usually not delicious when eaten straight, and it’s easy enough to chunk, chop, or melt a good eating chocolate. Your desserts will be much better for that bit of extra work.

You can even use good-quality “candy bar” chocolate for cooking; you’re not limited to whatever happens to be on the shelf in the baking aisle. For most desserts—and for eating—I turn to dark chocolate, labeled either bittersweet or semisweet.

HOW CHOCOLATE IS MADE

Chocolate is made from cacao beans, the seeds of the cacao tree. Twenty to fifty of them grow in an oblong pod; it takes about four hundred seeds to make a pound of chocolate. There are different types of cacao trees, which influences the flavor of the finished product, but other variables—where the cacao is grown and how it’s processed and blended—are equally or more important in determining quality and flavor.

Once the ripe pods are collected, the seeds and their surrounding pulp are fermented, a process that changes their chemistry and develops flavor. The beans are dried by machine or, preferably, in the sun. At this point they can be shipped to chocolate makers, who sort, roast, and shell the beans. The resulting nib is ground and refined into a paste called chocolate liquor (which contains no alcohol but can be thought of as a straight “shot” of chocolate). Separating the solids from the fat in chocolate liquor results in two products: cacao solids, which give a bar its distinct flavor, and cocoa butter, which makes the chocolate creamy, smooth, and glossy.

To get to edible chocolate, the liquor is usually mixed with other ingredients—most often (not always) sugar, and sometimes additional cocoa butter, vanilla, milk, or (less desirable) vegetable oils or other additives—then gently stirred or “conched.” Before chocolate can be molded and sold, it is tempered, a heating and cooling process that keeps it from crystallizing and makes the chocolate hard, smooth, and glossy. (See this recipe to temper your own chocolate for Chocolate-Dipped Anything.)

Here’s the bottom line: The quality of the ingredients, the number of additives, and the level of attention during the production process are what distinguish the best chocolate from others.

HOW TO BUY CHOCOLATE

There are, essentially, four types of solid chocolate: unsweetened, dark, milk, and white. Within those categories, the percentage of cacao solids and milk solids varies. The lingo can get confusing, so just remember this: The higher the percentage of cacao, the less sweet the chocolate will likely be. (Generally, higher percentages of chocolate solids also mean higher quality.)

THE CHOCOLATE LEXICON

Here’s a quick breakdown:

UNSWEETENED CHOCOLATE (Baking Chocolate, Chocolate Liquor) A combination of cacao solids and cocoa butter and nothing else; 100 percent cacao. Unsweetened chocolate is too bitter to eat but is useful for home chocolate making, cooking, and baking since it’s a blank canvas; you have complete control over the sugar content and flavors of whatever you make with it.

DARK CHOCOLATE (Bittersweet, Semisweet, Dark, Extra-Dark) This is the type of chocolate I use most often, good for everything from chopping for cookies to melting into ganache to eating out of hand. Most of the chocolate recipes in this book call for dark because it’s the easiest way to get strong chocolate flavor.

Dark chocolate must have at least 35 percent cacao solids, but usually that percentage is much higher, and no more than 12 percent milk solids (often there are none, but sometimes they’re added for texture). Since that leaves so much room for variation, look for an exact cacao percentage; 50 to 60 percent is a good all-purpose range. If none is mentioned, check out the ingredient list to see what else is included. A higher percentage doesn’t guarantee good quality, but it does mean there isn’t a lot of room for fillers and usually indicates more intense flavor.

All this can only tell you so much. To make any kind of informed decision about chocolate, you should try a few brands, then settle on your favorites. Good-quality dark chocolates coat your mouth evenly without any waxiness or grittiness and have a strong, pure chocolate flavor; they also snap cleanly when you break a piece.

MILK CHOCOLATE If you like sweet, melt-in-your-mouth chocolate, this is it. Milk chocolate must contain a minimum of 10 percent cacao solids, 12 percent milk solids, and 3.39 percent milk fat, and can be as complex as dark chocolate. Don’t skimp: Make sure what you buy includes real, high-quality ingredients and tastes rich and almost buttery. You can substitute milk chocolate for dark chocolate in cookies or ganache according to your preference, but be prepared for different results, with flavors muted against a backdrop of creaminess.

WHITE CHOCOLATE White chocolate is technically not chocolate, but a confection made from cocoa butter. It must contain at least 20 percent cocoa butter, 14 percent milk solids, and 3.39 percent milk fat; the rest is sugar (and ideally not much else). Although you can substitute it for dark or milk chocolate, it’s really a completely different ingredient.

There’s a deep chasm between good white chocolate and the cheap stuff. To avoid the latter, check the label for strange-sounding ingredients and make sure cocoa butter is listed first (cheap knockoffs use vegetable oil in its place). Then taste it: Good white chocolate has a subtle flavor with an irresistible creaminess from the cocoa butter and isn’t waxy, gritty, or bland. At its best it melts very slowly in your mouth and is something like what you might imagine eating straight vanilla would be like, although it doesn’t necessarily contain any vanilla at all.

COCOA POWDER After cocoa butter is pressed out of the nibs, or separated from the chocolate liquor, the solids are finely ground into a powder. “Dutched,” “Dutch-process,” or “alkalized” cocoa has been treated with an alkaline ingredient to reduce acidity and darken the color. “Natural” cocoa powder—ground roasted cocoa beans and nothing else—is lighter brown, with more intense chocolate flavor and natural acidity. Cocoa powder is essentially distilled cacao, so it’s worth the extra expense to get the good stuff.

As long as they’re unsweetened, natural and Dutch-process cocoas are interchangeable in most of the recipes here. (Sometimes I specify one or the other.) As a rule of thumb, natural cocoa should be used with baking soda and Dutch-process cocoa with baking powder; see The Basics of Leavening for more on substituting.

STORING CHOCOLATE

There’s no need to refrigerate chocolate, but it’s best kept in a cool, dry place (the fridge is as good as any, as long as it’s well wrapped). Stored properly, chocolate can last for at least a year; dark chocolate can even improve as it ages.

Sometimes chocolate develops a white or gray sheen or thin coating. The chocolate hasn’t gone bad; it’s “bloomed,” a condition caused by too much moisture or humidity or fluctuating temperatures, which cause the fat or sugar to come to the surface of the chocolate and crystallize. The chocolate is still perfectly fine for cooking as long as you’re not making coated candy. It’s also okay to eat bloomed chocolate out of hand too, although it may be grainy.

THE BASICS OF DAIRY

Dairy products should always be refrigerated, ideally at 40°F (or even lower) and never on the refrigerator door, which is warmer and less stable than the fridge’s cabin. Use what you need, then return the rest to the fridge; never put unused milk or cream back in the container or it may cause the whole batch to spoil faster. Store cheese and butter tightly wrapped in the refrigerator. You can freeze unsalted butter for months at a time, then thaw it completely in the fridge, but don’t freeze milk or cream.

MILK I only use whole milk for baking; it creates the fullest flavor and texture and the softest crumb. It contains 3.25 percent fat, which means 2 percent is an adequate substitute, though it makes no sense to me. One percent and skim milk will add no flavor or texture to your baked goods, only moisture.

BUTTERMILK This tangy, once-thick liquid was the by-product of churning butter. Nowadays it’s made from milk of any fat content that’s cultured with lactic-acid-producing bacteria, so it’s more like thin yogurt than anything else. Still, that added acidity makes an extra-tender batter for pancakes, some cakes, and biscuits.

HALF-AND-HALF Half milk, half cream, with a fat content that can range anywhere from 10.5 percent to 18 percent. It’s especially nice in puddings, custards, or ice creams if you want something richer than milk but not quite as heavy as cream.

CREAM Rich, thick, and unbeatable for everything from Whipped Cream to ice creams. You’ll see all sorts of confusing labels for cream, but the kind you want is heavy—not whipping and definitely not “light”—cream, without any additives or emulsifiers, and not ultra-pasteurized (this takes longer to whip and has a distinctive cooked flavor). Generally 1 cup of cream whips up to about 2 cups. The fat content of whipping cream ranges from 30 percent to 36 percent; heavy cream is 36 percent fat or more.

YOGURT Made from milk cultured with bacteria to produce its tangy flavor and thick consistency. Like buttermilk, its acidity tenderizes batters and doughs. Look for “live, active cultures” or similar terminology on the label and avoid any with gelatins, gums, stabilizers, or sugar.

Like milk, you can find it in whole, low-fat, and nonfat versions; strained versions like Greek yogurt are thicker. (You can make this yourself by putting regular yogurt in a cheesecloth-lined strainer.) In general, whole-milk yogurt gives the best results.

You can warm yogurt gently, but be careful or it may curdle.

SOUR CREAM AND CRÈME FRAÎCHE Made from cream cultured with lactic acid bacteria to make it thick and rich. Sour cream is tangier, with about 20 percent butterfat (although there are reduced-fat and fat-free versions, which you don’t need), while crème fraîche is usually at least 30 percent butterfat and has a creamy, mildly sour, and nutty flavor. Both are wonderful in baking, adding lots of moisture and lovely flavor; both—but especially crème fraîche—are excellent dolloped straight over finished desserts.

Take care if you’re cooking them over direct heat, as they can curdle—although not as quickly as yogurt—so incorporate them with other ingredients only over very low heat.

Crème fraîche can be hard to find (and expensive). Fortunately, you can make your own: Let a cup of heavy cream come to room temperature in a small glass bowl, then stir in 2 tablespoons of buttermilk or yogurt. Cover loosely and let the mixture sit at room temperature until thickened to the consistency of sour cream, anywhere from 12 to 24 hours. Cover tightly, refrigerate, and use within a week.

CREAM CHEESE, RICOTTA, AND MASCARPONE These mild, soft cheeses add body, creamy flavor, and just a bit of tang to baked goods, frostings, and fillings. Cream cheese is the thickest. Always buy it in bricks rather than the whipped version in tubs, and let it soften to room temperature before you use it.

The best ricotta is milky, fresh, and soft, with such a light texture it’s like eating a cloud; cheesemongers and even some Italian delis make it fresh daily, and that’s best. If it seems especially runny, strain it in a fine- or medium-mesh sieve before combining with other ingredients. Commercially produced ricotta will do the job for batters and doughs (although you’ll be sacrificing some of the fabulously mild flavor and creaminess), but for pastries where it’s the filling or a main flavor, you’re better off using another creamy cheese—goat cheese is good for savory recipes and cream cheese for sweet. Ricotta varies drastically in quality, so check the ingredients and make sure it’s not packed with preservatives or chemicals.

Mascarpone, like crème fraîche, is soft, buttery, and only mildly tart, ideal both in batters or custards and as a simple topping or garnish; it can also be just as pricy and hard to find. Generally, you can use them interchangeably, but if you want mascarpone’s sweeter flavor and can’t find it, whip 1 cup softened cream cheese with ¼ cup heavy cream and 2 tablespoons softened butter until smooth and light.

THE BASICS OF LEAVENING

Baking soda, baking powder, yeast, and natural starters like sourdough are all leaveners, which means they give baked goods lift (the word leaven means “lighten”). They all work the same way: by producing carbon dioxide bubbles that are trapped by the dough or batter’s structure and, in turn, make it rise.

Baking soda and powder, typically used in quick breads, cookies, cakes, and the like, are chemical leaveners. They’re used very similarly but aren’t immediately interchangeable (if you don’t have the one you need, see the chart below for substitutions). Yeasts are actually living organisms that produce carbon dioxide as they feed on the natural sugars in bread and pastry doughs; they can be store-bought or cultivated from wild yeasts (as in sourdough and biga).

Be careful to add only the amount of leavener specified in the recipe. Baking soda and powder can taste quite salty and bitter, even soapy, if they’re not balanced by other ingredients, and too much of any leavener can cause air bubbles to grow too big and break, making your baked goods collapse.

Baking powder, double-acting

AMOUNT: 1 teaspoon

SUBSTITUTION: ½ teaspoon cream of tartar plus ¼ teaspoon baking soda; add ¼ teaspoon cornstarch if you’re making a big batch to store

or

1½ teaspoons single-acting baking powder

or

¼ teaspoon baking soda; replace ½ cup nonacidic liquid in the recipe with ½ cup buttermilk, soured milk, or yogurt

Baking powder, single-acting

AMOUNT: 1 teaspoon

SUBSTITUTION: ⅔ teaspoon double-acting baking powder

or

¼ teaspoon baking soda plus ½ teaspoon cream of tartar

Baking soda

AMOUNT: ½ teaspoon

SUBSTITUTION: 2 teaspoons double-acting baking powder; replace acidic liquid in recipe with nonacidic liquid

Yeast, instant

AMOUNT: 2 teaspoons

SUBSTITUTION: 1 cake fresh (⅗ ounce)

or

1 packet (¼ ounce or 1 scant tablespoon) active dry

BAKING SODA

Baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) produces carbon dioxide only in the presence of liquid and acid, like buttermilk, yogurt, or vinegar. Every recipe that uses baking soda must have an acidic component or it will not rise. Furthermore, baking soda releases all of its gas at once, so it’s best to add it with the flour, at the last minute before baking. Once it hits the acid and liquid, it goes to work, and you want those bubbles formed in the oven, not on the counter, so don’t delay baking delicate batters that contain it. (It’s okay, and sometimes even preferable, to hold off on baking denser things like cookies or bars.)

Take care when you’re baking with cocoa powder: Natural cocoa powder has enough acidity to activate baking soda, but if you’re using Dutch-process cocoa and there are no other acidic ingredients, you must substitute baking powder. If you use natural cocoa powder and there’s no baking soda in the recipe, add ¼ teaspoon to balance the acidity and improve leavening.

BAKING POWDER

Baking powder is simply baking soda with a dry acid added to it (along with some starch, which keeps the baking powder dry and therefore inert until it is added to a recipe). Single-acting powders generally contain cream of tartar as the acid, which is activated by moisture, so the batter must be baked immediately after mixing, just like those containing baking soda. Double-acting powder, which is more common, usually contains both cream of tartar and the slower-acting sodium aluminum sulfate, so it releases gas in two phases: The cream of tartar combines with the soda and produces the first leavening; the aluminum sulfate reacts to heat, so it causes a second leavening during baking. Therefore, a batter using double-acting baking powder can sit at room temperature for a few minutes before being baked, but just a few.

YEAST

The process of leavening is as old as baking—that is, thousands of years—but it changed significantly when Louis Pasteur discovered in the mid–nineteenth century that yeasts are actually living, single-cell organisms that produce carbon dioxide through fermentation. Before then, most breads were risen with sourdough starters, which contain wild yeasts (see All About Sponges and Starters for more on wild yeasts). After Pasteur, commercial yeast began to dominate. There are a few kinds:

INSTANT YEAST Also called fast-acting, fast-rising, rapid-rise, and bread machine yeast, this is the yeast I use in every recipe in this book. It’s a type of dry yeast and by far the most convenient: It can be added directly to the dough at almost any point, and it’s fast and reliable. It has ascorbic acid added (and sometimes traces of other ingredients too); this helps the dough stretch easily and increases loaf volumes. In most doughs, you won’t notice any difference in flavor. Like active dry yeast, it comes in ¼-ounce foil packets or in bulk; it keeps almost forever, refrigerated or frozen.

ACTIVE DRY YEAST This type falls in between instant and fresh and was used by most home bakers until instant yeast came along. Active dry yeast is fresh yeast that has been pressed and dried until the moisture level reaches about 8 percent. Unlike instant yeast, it must be rehydrated, or “proofed,” in 110°F water (it should feel like a hot tub when you dip your finger in it); below 105°F it will remain inert, and above 115°F it will die. So if you must use active dry yeast instead of instant, use a thermometer! It is sold in ¼-ounce foil packets, which don’t need to be refrigerated. Like instant yeast, it’s also sold in loose bulk quantities, which should be stored in the refrigerator.

FRESH YEAST Also known as cake or compressed yeast, fresh yeast is usually sold in foil-wrapped cakes of about ⅔ ounce. It should be yellowish, soft, moist, and fresh smelling, with no dark or dried areas. Fresh yeast must be refrigerated (you can freeze it if you like); it has an expiration date and will die within 10 days of opening. It also must be proofed before being added to a dough. This means you must combine it with warm liquid; when you do, it will foam and smell yeasty (if it doesn’t, it’s dead).

THE BASICS OF SEASONING

Most baked goods are rich and sweet enough, but an extra dash of flavor can transform good into unforgettable or old standby into something new. Spices, extracts, and other seasonings add dimension, and often you can play around with them, adding them at will: Even if you’re not wild about the flavor someone else is likely to be.

Remember, though, unlike savory cooking, baking doesn’t provide many chances for you to taste and adjust seasoning, so think it through before you start randomly tossing flavors into your concoction. When I’m experimenting, I like to take notes as I go to log what went well (and what didn’t). Err on the side of less seasoning; you can always punch up the finished product with a sauce, glaze, or fruit.

SPICES AND SALTS

Whole spices are usually of higher quality than ground, keep well, and have the best flavor when they’re freshly ground. A spice or coffee grinder does the best job of this and need not cost more than $20; but they’re difficult (or impossible) to wash, so you might use separate grinders for spices and coffee. You can also grind spices by hand with a mortar and pestle; press in a firm and circular motion until powdery. Toasting spices before grinding deepens their flavor.

Preground spices are convenient, though, and often the difference is not huge in baked goods. Some pregound spices are better than others; check the list below for help. Store spices in tightly covered containers in a cool, dark place for up to 1 year; know that the flavor will diminish over time, so add a little extra whenever you’re using old spices.

ALLSPICE Berries from the aromatic evergreen pimento trees, these are small and shriveled; they look like large peppercorns, smell a bit like a combination of cloves and nutmeg, and taste slightly peppery. Available as whole berries or ground. Use just a pinch; a little goes a long way. Extremely useful in pies, puddings, and gingerbread.

CARDAMOM A hallmark of Scandinavian baking that’s also common in Indian and Middle Eastern foods. Whole pods may be green, brown-black, or whitish. Each contains about ten brown-black slightly sticky seeds with a rich spicy scent, a bit like ginger mixed with pine and lemon: great with most fruit, paired with other warm spices, or in quick breads. Available as whole pods, “hulled” (just the seeds), and ground. Ground is the most common but by far the least potent. I buy whole pods and mince or grind the seeds in a mortar and pestle. You don’t need much since the flavor is so strong and distinct.

CINNAMON One of the most widely used spices in baking, from the aromatic bark of a tropical laurel tree. Ground cinnamon is useful and flavorful, but it’s easy enough to grind the long, slender, curled sticks of bark. The whole sticks are also ideal for infusing liquids, as when poaching pears or making Simple Syrup. A classic pairing for apples and pears; also excellent with chocolate, in quick breads and cookies, and in custards and puddings.

CLOVES The unripe flower buds of a tall evergreen native to Southeast Asia. Pink when picked, they are dried to reddish brown, separated from their husks, then dried again. Whole cloves should be dark brown, oily, and fat, not shriveled. They have a sweet and warm aroma and a piercing flavor. Both whole and ground forms are common, and both are good but should be used sparingly—the flavor can be overwhelming.

GINGER Available fresh (a large, tan, slightly leathery rhizome that you peel and mince or grate on a Microplane), ground, or candied (also called crystallized). Ground is more suited to making batters and doughs and combining with other spices because it has a mellower flavor, but fresh is unbeatable for spicy, lively flavor—bright and potent. Fresh ginger should be stored, skin on, in the fridge; to prepare it, use a paring knife or vegetable peeler to remove the tough skin, then grate or mince it.

You can use ground and fresh interchangeably: figure ¼ teaspoon ground equals 1 tablespoon grated fresh.

NUTMEG The egg-shaped kernel inside the seed of the fruit of a tropical evergreen tree, dark brown and about 1 inch long. Available whole or ground; whole will keep forever and is easy to grate on a Microplane, with a far better flavor, so there’s no reason to buy ground. It’s strong and slightly bitter, so use sparingly—start with ⅛ teaspoon or even less before adding more. A sweet and warm spice, it’s lovely with fruit and in custards, puddings, and cakes.

SAFFRON The most expensive spice in the world; the threads are pistils of a crocus that has a short growing season. But it’s potent stuff, so you need only a small pinch in most instances. It’s highly aromatic, warm, and distinctive, and gives food a lovely yellow color. Ground saffron is useless, and probably not saffron at all; buy only the threads from a reputable source (saffron.com has been such a source for at least thirty years). Steep them in a bit of warm water, then add the water to batter or dough.

SALT As you know, essential everywhere, and in baking no less than elsewhere. There are a few kinds:

STAR ANISE The fruit of an evergreen tree native to China; pods are a dark brown, eight-pointed star, about 1 inch in diameter, with seeds in each point, perhaps the strangest-looking spice you’ll ever buy and quite lovely. Although it has a licoricelike flavor, it is botanically unrelated to anise. Available whole; steep it in cream or other warm liquid to use.

VANILLA BEANS From the seed pod of a climbing orchid, grown in tropical forests, this is probably the most widely used flavoring in baking. Good pods are 4 to 5 inches long, dark chocolate brown, and tough but pliant. Inside they have hundreds of tiny black seeds. Good vanilla is expensive, so be suspicious of cheap beans. Wrap tightly in foil or seal in a glass jar and store in a cool place or the refrigerator. Use a paring knife to split the pod lengthwise and scrape the seeds into batters, doughs, or cooking liquid. Vanilla extract isn’t as good, but it isn’t bad, either; see the following section.

Using a Vanilla Bean

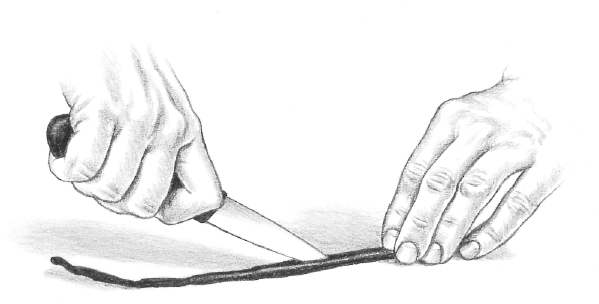

Step 1

Use a paring knife to split the vanilla bean in half the long way.

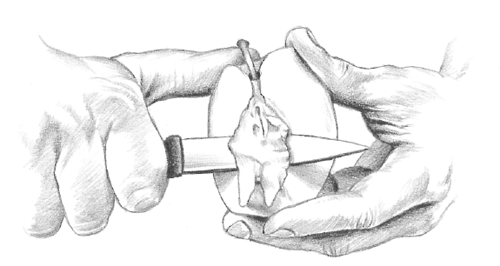

Step 2

Scrape out the seeds with the knife.

EXTRACTS, OILS, AND WATERS

These concentrated infusions of flavor are easy to incorporate into all sorts of doughs, batters, and custards and often more effective than using the original ingredient.

Extracts are made with alcohol, so they’re not very heat stable and will eventually start to evaporate and lose flavor; wait to add them to warm liquids until they’re off the heat and have had a minute to cool down. As a rule, steer clear of “flavorings”—as opposed to extracts—which may be pure but are often synthetic and/or diluted.

VANILLA EXTRACT The most popular and cost-effective way to bake with vanilla. Use it in just about anything, whether you want the vanilla front and center or just to round out the other flavors. Look for “pure” on the label; imitation vanilla is weak at best, bitter and chemical tasting at worst.

You can sometimes find vanilla paste, which is more expensive than extract but contains the intensely fragrant seeds you’d find in a pod. Generally you can use the same quantities as you would of extract, but check the label beforehand.

ALMOND EXTRACT Like almond to the nth degree, this is a great way to add sweet, nutty flavor to almost anything. Use it to complement pistachios, pecans, walnuts, or any stone fruit, but a little goes a long way, so never add more than ¼ teaspoon at a time.

PEPPERMINT EXTRACT A perfect match with dark or white chocolate in brownies, candies, and even frostings. The extract is made by combining peppermint oil with alcohol, but you may prefer to buy the oil itself (see below) for a more potent and intense flavor. Extract, however, is a bit more forgiving.

FLAVORING OILS The most potent way to add flavor, since it’s just the essential oil of the base ingredient; make sure it’s pure and food grade. You can find peppermint, almond, orange, lemon, and lime oils and more in specialty shops.

ROSE WATER AND ORANGE BLOSSOM WATER Produced from the distillation of roses or orange blossoms in water. Rose water’s delicate flavor is an excellent match for stone fruits, berries, melon, and pistachios; orange blossom, citrusy and just slightly bitter, goes especially well with honey, warm spices, nuts, and dried fruit.

Both are highly aromatic, imparting exotic floral flavors that are beguiling in puddings, custards, even cakes and frostings, and many Middle Eastern and Indian desserts. Be careful not to use too much, or your food will taste like perfume; a couple of drops are enough to add just a suggestion of something floral.

OTHER SEASONINGS

You can use solid ingredients by grinding, mincing, or chopping them, or by infusing any of them into liquid. This is an unusual way to capture the flavor of your favorite teas or flowers, and the most reliable way to add coffee to your baking.

TEA Tea is an overlooked ingredient for many baking recipes. As with chocolate, start with something you’d enjoy on its own, whether black tea, scented tea like Earl Grey or jasmine, or green tea. (Matcha, a Japanese green tea, is already finely ground, so you can incorporate it as easily as ground spices.) Generally, there are three ways to add tea in baking:

Food Coloring

Some people get up in arms about artificial food coloring, but I think it’s much more of a cause for concern in processed foods, when it may be used to make things look fresher than they are or mask other ingredients. In your home cooking, when you’re just adding a few drops here and there to otherwise whole ingredients, it’s harmless—and there’s no denying it’s fun when you’re baking with kids or for the holidays.

You can make your own natural food coloring. Just be aware that if you add a substantial amount to a recipe, you might change the consistency and flavor of the finished product. But here are the best natural alternatives I’ve found; start with the recommended amount and add a bit more as you need. For fresh fruit and vegetables, purée in a blender or food processor (use a bit of water to loosen them up if necessary), strain, and use the juice:

COLOR |

SUBSTITUTION |

Red and pink |

At least 1 tablespoon beet juice, fresh or from a can of beets |

Orange |

At least 1 tablespoon carrot juice |

Yellow |

At least ¼ teaspoon ground turmeric |

Green |

At least 2 tablespoons spinach juice |

Purple |

At least 1 tablespoon blueberry or blackberry juice |

COFFEE Substitute freshly brewed coffee for up to half of the liquid in recipes for sauces like Simple Syrup or Caramel Sauce or add 1 or 2 shots of espresso to any dough or batter. An alternative, if you have it around, is adding a bit of instant coffee directly into the other dry ingredients.

HERBS These don’t just play a prominent role in most cooking—in baking, too, they add an unparalleled freshness and depth of flavor that sets a recipe apart. Of course, they’re perfect in a savory application with cheese, eggs, or vegetables, but they’re also a natural match and pleasant surprise with many fruits and sweet custards.

Fresh herbs keep best when stored in the refrigerator; put them, stem side down, in a glass of water as you would a bouquet, with a plastic bag over the leaves; change the water every day. Sturdier herbs, like rosemary and thyme, can simply be wrapped in damp paper towels and slipped into a plastic bag, but be sure to change the towel regularly so it doesn’t mold. The stems are usually bitter, and for some herbs, like rosemary, they’re practically inedible, so strip the leaves from the stems before using.

You can find dried versions of nearly any herb, with varying degrees of success. As a rule of thumb, softer herbs—like parsley, cilantro, mint, basil—should always be used fresh; those with woody stems and sturdier leaves—think rosemary, thyme, oregano, sage—are fine dried. Store dried herbs in sealed lightproof jars (or in a dark place) for up to a year. Their flavor will get weaker over time; taste before using and you’ll know when it’s time to replace them.

Dried or fresh, herbs can be incorporated into your baking in a few ways: minced and stirred directly into batters, doughs, custards, or fruit and vegetable fillings; infused into warm liquids and then strained out; or chopped and scattered as garnish. I especially like basil paired with peaches or berries; fresh mint with chocolate or fruit; and rosemary with apples, pears, and warm spices.

THE BASICS OF FRESH PRODUCE

Produce can be a star or play a supporting role alongside bigger flavors; it adds color, moisture, and flavor. The wonderful thing about baking with fresh fruits and vegetables is that when they’re good, they’re good, and often interchangeable. A tart, jam, or other fruit dessert that features excellent summer berries will be just as fabulous if you make it in the winter and substitute apples or pears; and vegetables are excellent in all kinds of baking, whether they’re filling savory pastries or grated into Zucchini Bread or Carrot Cake.

In general, in-season is best, but it’s a mistake to think “fresh or nothing.” Some frozen produce is not only good enough to eat but sometimes better than what passes for fresh, especially, of course, in winter. The same can sometimes be said of canned items like pumpkin. No matter what you get, do be picky when you buy: Fresh produce should be neither too firm nor too soft, and frozen and canned varieties should have no added ingredients like sugar.

When buying fresh produce, check for damage or rotten spots and make sure the color is close to ideal. Pay attention to where it came from, keeping in mind that miles traveled are a good indication of how long ago fruits and vegetables were harvested. Virtually all produce is available year-round, but seasonal selections are usually just better. (You may naturally gravitate to what’s seasonal anyway, since that’s what’s both tastiest and grown closer to home.) Moreover, if you’re concerned about the impact of mainstream farming methods on your health and the environment, seeking out locally or regionally grown fresh produce—even if that means making substitutions based on what’s available—means you’ll be getting the best fruits and vegetables available and supporting the people who raise them.

THE FRUIT AND VEGETABLE LEXICON

The more you bake with fruit and vegetables, the more you’ll love it—there are so many opportunities to experiment, and when you start with good stuff, your job is so easy. (Even if you don’t start with good stuff, baking has the ability to mask some flaws.)

Here’s what you need to know about choosing and preparing those fruits and vegetables most commonly used in baking. (For those used in savory applications, see How to Prep Any Vegetable for Savory Baking.)

APPLES

When it comes to baking, not all apples are equal. And, happily, since apples are among the few fruits that still sport many varieties in the big markets, there is plenty of opportunity to find the good ones. Because you want your finished dish to be neither too sweet nor too tart, neither too crisp nor too yielding, and bursting with unmistakable apple flavor, the apples you choose should be succulent, but shouldn’t give up too much juice, or they’ll bog down the dough, batter, or crust.

The greatest variety, of course, is at local orchards in the fall; types vary from region to region, but among the most common are McIntosh, Cortland, Golden Delicious, and the decent if not fabulous Honeycrisp and Granny Smiths. When in doubt, cook with apples that you’d be happy eating.

PREPARING Rinse; peel if you like, starting at either end and working in latitudinal strips or around the circumference—I like a U-shaped peeler, but the choice is personal. You can get rid of the core with a slicer-corer, which will cut the apple into six or eight slices around the core in one swift motion; dig it out with a melon baller; or cut the apple into quarters with a paring knife and trim the core from each quarter (see illustrations below).

Coring an Apple

Step 1

If you want to keep the apple intact but remove the core, use a melon baller to dig out the core from the blossom end of the apple.

Step 2

For other uses, simply cut the apple into quarters and remove the core with a paring knife.

APRICOTS, PEACHES, NECTARINES, AND PLUMS

Stone fruit are succulent, juicy, and luxuriously sweet-tart, whether raw or cooked. Peaches and nectarines are nearly identical in shape, color, and flavor, but peach skin has a soft fuzz (increasingly bred out, sadly) and nectarine skin is smooth; use them interchangeably.

Apricots are small, with silky skin; good fresh apricots are stunningly good but increasingly difficult to find (Blenheims, in my experience, are the best variety you can buy without becoming a fanatic). Dried apricots may be a better choice, and can be soaked to make them plumper and more tender.

Plums come in hundreds of varieties, ranging in flavor from syrupy sweet to mouth-puckeringly tart. My favorite are red-fleshed or green, but they all can be good.

In general, look for plump, deeply colored, gently yielding, and fragrant specimens without bruises. Tree-ripened fruit is best, especially in the summer, when it’s most likely to be local. Stone fruit does ripen at room temperature, however (but quickly): Put hard fruit in a paper bag to hasten ripening or just let it ripen on the counter, and keep your eye on it.

PREPARING Wash, cut in half from pole to pole, and twist the halves to remove the pit. To peel, leave the fruit whole, cut a shallow X into the bottom end, and drop into boiling water for 10 seconds or so, just until the skin loosens; plunge into a bowl of ice water until it cools completely, then slip off the skin with your fingers or a paring knife.

BANANAS

A tropical plant with hundreds of varieties, the most familiar—and almost the only one seen in the U.S.—is the Cavendish. They ripen nicely off the plant and are often sold green; store at room temperature for anywhere from a day to a week. You can refrigerate to delay further ripening; the skins may turn black, but the flesh is good to eat for weeks. The longer they ripen, the softer and sweeter they become, and if you’re using them to bake, it’s actually preferable to let them become brown all over for a deeper, rounder flavor. You can also peel bananas and freeze them in plastic zipper bags; thawed to room temperature, they’ll be ugly and brown but be perfect for banana bread.

PREPARING Just peel and chop or slice as needed. Squeeze some lemon or lime juice over the freshly cut banana to prevent discoloring if it’ll be served raw (or just top with whipped cream and no one will know the difference!).

BERRIES

There are hundreds of types of berries, ranging from sweet to tart to everything in between. Supermarket varieties, sadly, are picked well before their prime, so they sometimes wind up tasting like cardboard (sweetened cardboard, if you’re lucky). For the best berries, you’ve got to go local and in season. All should be fragrant (especially strawberries), deeply colored, and soft but not mushy. For the most part they’re interchangeable in any berry pies, tarts, or cobblers; try combining them to your tastes.

Blueberries can be considered the all-purpose berry: hardy (for a berry), fairly inexpensive, beautifully colored, and delicious. Look for ones that are plump and unshriveled; size is irrelevant. Peak season is July and August, but unlike most berries they’re even decent off-season. The blueberry’s closest relatives, huckleberry and juneberry, are too fragile ever to make it even to a farmers’ market, but if you’re lucky enough to find them, they’re great in any blueberry recipe.

The strawberries you’ll find year-round at the supermarket are grown more for hardiness and disease resistance than for flavor, and that’s a real shame because a truly ripe strawberry is heavenly, best raw in Strawberry Shortcakes or Strawberry Pie. Peak season in most places is early summer; out of season, they’re just no good.

Blackberries and raspberries, along with all their cousins (boysenberries, loganberries, and mulberries, to name a few), are varying degrees of sweet-tart. If you live in the northern half of the United States, these berries grow wild and in abundance all summer; keep your eyes peeled for low-lying bushes with colorful fruit. When buying in plastic containers, inspect the pad of paper under the berries; if it’s heavily stained with juices, keep looking.

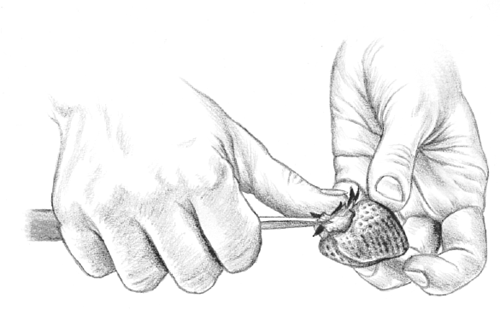

PREPARING Gently wash and dry; be especially gentle with blackberries and raspberries. Pick over blueberries and remove any stems. To hull strawberries, pull or cut off the leaves and use a paring knife to dig out the stem and core (see illustration).

Preparing Strawberries

To prepare strawberries, first remove the leaves, then cut a cone-shaped wedge with a paring knife to remove the top of the core. A small melon baller also does the job nicely.

CARROTS

The most common root vegetable (potatoes are tubers), carrots aren’t just for side dishes and stocks: They have a sweetness all their own that’s perfect in baking, as evidenced by the popularity of Carrot Cake. Cheap, versatile, and available year-round, the ones from the supermarket are easy to use, but it’s worth trying those from a local farm to marvel at the intensity of their flavor. Avoid any carrot that is soft, flabby, or cracked, and store in your vegetable drawer, wrapped loosely in plastic in the refrigerator; they keep for at least a couple of weeks.

PREPARING Peel with a vegetable peeler, then trim off both ends. Chop, slice, or grate as the recipe directs.

CHERRIES

When cherries are good, they are succulent, juicy, fleshy, and even crisp, with a compelling flavor somewhere between berries and other stone fruits. Sweet varieties, like the deep red, heart-shaped Bing we often find at supermarkets, are best for eating out of hand or for a topping or tart filling. For baking, tart cherries—more often sold at farmers’ markets and farmstands, typically smaller, brighter red, and rounder in shape—have a more complex flavor. Either way, look for shiny, plump, and firm specimens with fresh-looking green stems. Keep refrigerated and use as soon as possible; they won’t last long.

PREPARING Wash, dry, and remove the stems. A cherry pitter (which also works for olives) is handy; you can also MacGyver a pitter with a clean bobby pin or paper clip, pushing it to the center of the fruit and using it to hook the pit to pull it out, or by pushing out the pit with a chopstick (wear old clothes). Or cut the cherries longitudinally or pop them open with your fingers, twist the two halves apart, and use a paring knife or your fingers to pull out the pit.

CITRUS (LEMONS, LIMES, ORANGES, AND GRAPEFRUIT)

Citrus fruits’ bright, sunny flavor shines in Lemon Curd, Key Lime Pie, and Orange Soufflé. But even when you’re not going for an assertive citrus flavor, a squeeze of lemon juice provides balance to many baked fruit fillings like apple, pear, or peach; juice from oranges, grapefruit, and limes makes a stellar and distinctive complement to nearly any fruit. A sprinkle of zest—the colorful portion of the outer skin (but not the white pith underneath, which is bitter)—can be added to almost anything, from cookie doughs and cake batters to sauces and custards, for wonderful flavor without the acidity of the juice.

Citrus is available all year, although winter is when you’re likely to find the most unusual—and, typically, best—varieties. Meyer lemons are less acidic, with a uniquely floral, piney fragrance; key limes are tiny, round, and sweeter than the more common variety; clementines, satsumas, and tangerines are all sweet-tart varieties of the classic Mandarin orange; blood oranges have a stunning, deep red flesh.

In any case, look for plump specimens that are heavy for their size and yield to gentle pressure; hard or lightweight fruit will be dry. Store in the refrigerator.

Preparing Citrus

Step 1

Before beginning to peel and segment citrus, cut a slice off both ends of the fruit so that it stands straight.

Step 1

Cut lengthwise, with the blade parallel to the fruit and as close to the pulp as possible, to remove the skin in long strips.

Step 3

Cut between the membranes to separate segments.

Step 4

Or cut across any peeled citrus fruit to make “wheels.”

PREPARING If you are both zesting and juicing a citrus fruit, do the zesting first: For tiny flecks that are nearly undetectable in dishes except for their flavor, use a sharp grater (like a Microplane or the smallest holes of a box grater). Or use a zester, a nifty tool with small sharp-edged holes, to cut long, thin strips of zest, which can then be minced or used whole as a wonderful garnish. A paring knife works too.

See the illustrations above for peeling and segmenting the whole fruit.

Citrus is easiest to juice at room temperature, especially if you roll it on the countertop first to loosen it up a bit; use a reamer, juicer, or fork to extract as much juice as possible.

MANGOES

There are dozens of shapes, sizes, and colors of mango, and they can range from exceedingly tart to syrupy sweet. Color isn’t as important as texture; the softer it is, the riper. Some varieties of mango will start to wrinkle a bit at the stem when they are perfectly ripe. Bought at any stage, however, the mango will ripen if left at room temperature. Once ripe, store in the refrigerator or it will rot.

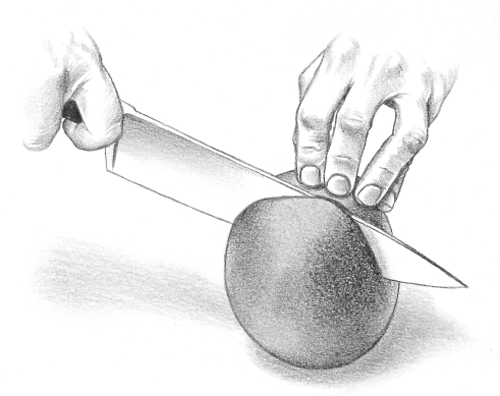

PREPARING There are a few different ways to get the meat out of a mango and remove the long, narrow seed; how you do it will depend on your knife skills and your patience. See the illustrations below.

Version I

Step 1

Peel the skin from the fruit using a normal vegetable peeler.

Step 2

Then cut the mango in half, doing the best you can to cut close to the pit.

Step 3

Finally, chop the mango with a knife.

Version II

Step 1

Begin by cutting the mango in half, doing the best you can to cut around the pit.

Step 2

Score the flesh with a paring knife.

Step 3

Turn the mango half “inside out,” and the flesh is easily removed.

PEARS

Pears are one of the few fruits that actually improve after being picked; their flesh sweetens and softens to an almost buttery texture that becomes doubly tender once baked or poached. But finding a perfectly ripe pear can be tricky: Their peak is fleeting, so we often end up with either a crunchy fruit with little flavor or a mushy one with unappealing texture. Don’t be discouraged if all you can find are hard, green fruit. Leave them at room temperature until the flesh yields gently when squeezed and smells like . . . well, pear; some varieties will also change color, from green to yellow.

The Anjou and Bartlett varieties are ubiquitous: sweet, firm, and suitable for most baking when they’re ripe, but rarely impressive; Bosc and (sometimes) Comice, also in most supermarkets, are better. Visit local farmers’ markets and orchards in the fall and you’re likely to find more, with a range of flavors and textures.

PREPARING Peeling is not necessary, but it’s easy with a vegetable peeler. Core as you would an apple.

PINEAPPLE