![]()

Although plant disease is everywhere and plants are constantly exposed in the air and soil to the spores and other reproductive structures of a wide variety of potential pathogens, most plants are resistant to attack by most pathogens. Just look around the garden or the countryside and you will find ample evidence that unless an epidemic is raging, disease is the exception rather than the rule. Take a close look at a rose border you have omitted to spray, for example: mildew may be present, but not on all the varieties; black spot may be there too, and if you are unlucky there may be rust on some of the older cultivars and species; but few of the plants will be infected by more than one pathogen, and even those that are infected will have limited the progress of the pathogen so that the lesions grow relatively slowly. Some of the species and/or cultivars will show more resistance than others to each of the pathogens, and some may even be immune.

Wherever you look, in the garden, in agriculture or in natural ecosystems, the pattern will be very similar. Interactions between pathogens and hosts are highly specific, and where disease does occur both susceptibility and resistance may be seen within host populations matched, as we shall see, by virulence (ability to cause disease in a specific host) and avirulence (inability to cause disease in a specific host) within pathogen populations. Finding an explanation for such specificity has occupied the minds of plant pathologists since the last century, and we are still a long way from having a complete picture of the mechanisms involved. In the pages that follow we will present our model of disease resistance in plants, based on the complex and often confusing body of evidence accumulated during the last hundred years or so. The model will not be correct in every detail, and we know that as new evidence comes to light the model will have to be changed to accommodate it. That is the nature of science: evidence is gathered, hypotheses are formulated and tested by experiment and new hypotheses follow.

The evidence and hypotheses are complex. If you would prefer to read about the diseases of plants, turn to Chapter 4, but if you would enjoy the challenge of getting to grips with one of the most exciting aspects of plant pathology, read on.

THE FIRST LINE OF DEFENCE

Plants utilise a variety of mechanisms to exclude potential invaders. Firstly, the very structure of the plant body renders it relatively impregnable to attack. The above-ground portions are covered with a cuticle composed of the tough fatty polyester cutin. Water does not easily adhere to this hydrophobic surface, so that spores landing on the leaf are not easily wetted and spores arriving in water droplets may find no safe resting place. If wax crystals are also present on the surface, as is often the case, or a dense covering of hairs, water droplets are even less likely to stick. Even when spores do remain on the plant long enough to germinate, and sufficient moisture is present to sustain growth of the cells or hyphae, the potential pathogen must be equipped with the appropriate enzymes to dissolve cutin, or must be adapted to gain entry through wounds or natural openings like stomata. In older tissues and roots the process of penetration may also be frustrated by the presence of other complex hydrophobic polymers such as suberin, the principal component of the corky tissue of bark, or lignin, the main component of wood.

THE POISONED CHALICE – PRE-FORMED TOXINS

It is small wonder that, with such formidable barriers to circumvent, few potential pathogens ever gain entry to a plant. Those that do are then likely to have their further progress impeded by the inhospitable chemical environment of the cells and tissues. First of all, the pH may be too high or too low, or wide-spectrum toxins such as alkaloids, phenolic compounds or, especially in seeds, proteins, may be present to destroy all would-be pathogens except those with the appropriate antidote.

Take sitka spruce trees (Picea sitchensis), for example. Trees of this species have been shown to contain high levels of the stilbene glucosides astringin and rhaponticin. These chemicals are highly toxic to fungi and are thought to play a significant role in defence. However, some wood-rotting fungi such as Heterobasidion annosum (butt rot), Armillaria mellea (honey fungus) and Stereum sanguinolentum (red-stain rot) have developed the ability to produce enzymes that detoxify stilbenes and are therefore able to penetrate the wood and cause severe disease.

Similarly the cells of oat roots contain avenacin, a complex molecule called a triterpenoid saponin with a carbohydrate side chain. This binds to the cell membranes of fungi, including Gaeumannomyces graminis, the soil fungus responsible for the take-all disease of cereals and grasses (Gramineae). This means that oat, unlike wheat, is resistant to the common form of G. graminis (called f.sp. tritici). One form of G. graminis has evolved, however, to produce the enzyme avenacinase, which detoxifies avenacin by cutting off the side chain. This form, G. graminis avenae, is capable of infecting oat and causing a take-all disease that is just as destructive as the one seen on wheat.

FIGHTING BACK – GENERAL ACTIVE DEFENCE

If a potential pathogen is able to breach the plant’s structural defences and survive the toxic chemicals in the cells, a further line of defence may be brought into play. This involves the activation of new biochemical pathways that change the cellular environment, making it even more hostile to microbial growth. Firstly, however, the invader must be recognised as an alien. Whether specific chemicals secreted by microbes or structural molecules of their cell walls and/or membranes are recognised by the plant, or whether general stress is the signal, is not known. Fungi and bacteria secrete a wide range of chemicals during pathogenesis, such as enzyme proteins and polysaccharides, any of which might enable a plant to recognise them as aliens. Moreover, components of the cell wall such as proteins, glycoproteins and polysaccharides, as well as the fatty components of membranes, might also function as recognition factors. Different experiments with various host-parasite interactions have implicated all these factors, as well as metabolic poisons such as heavy metals and antibiotics, as ‘elicitors of defence reactions’. It is probable that different groups of plants have evolved different mechanisms for recognising a wide spectrum of alien invaders.

Once recognition has occurred a chemical signal is activated in the plant cells, ultimately triggering the defence responses. The nature of this signal is again largely unknown, but various factors involved in signalling in animals, such as free radicals (especially superoxide), calcium, calmodulin, G-proteins, protein kinases and phosphatases have all been implicated in defence responses of different plant species. As with recognition, it is likely that plants have a relatively flexible signalling system to switch on general active defence responses in a wide variety of circumstances.

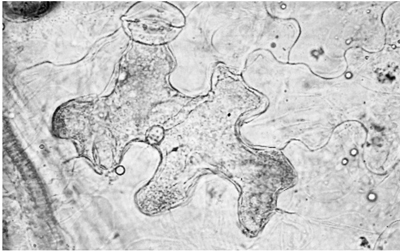

Following recognition, a ‘hypersensitive response’ almost invariably occurs (Figs. 3.1 and 3.2). This is a kind of cell suicide, activated by an invader, that has evolved as part of a suite of responses to limit or prevent further spread of that invader. It involves the rapid programmed collapse and death of the initially invaded cell and sometimes the cells adjacent to it. The dead cells turn brown almost immediately. The mechanism of cell death is poorly understood, but research with potato suggests that it probably involves release of the free radical superoxide within the invaded cell. This damages the membranes irreversibly and the cell collapses. Phenol-oxidising enzymes are then released and these convert cellular phenolic compounds to dark, toxic polymers such as melanin which are laid down in the cell wall. The hypersensitive response alone is probably sufficient to prevent the further growth of obligate biotrophs, which require living cells if they are to survive, but additional responses are required for the limitation of necrotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens.

FIG. 3.1

The hypersensitive response: cotyledons (first formed leaves) of a lettuce (Lactuca sativa) cultivar containing a gene for resistance, inoculated with droplets of water containing spores of an avirulent race of Bremia lactucae, cause of downy mildew. The invaded cells have died rapidly and turned brown. (I.C. Tommerup.)

FIG. 3.2

A single cell of lettuce exhibiting the hypersensitive response to an avirulent race of Bremia lactucae. (D.S. Ingram.)

The best studied of these is the rapid accumulation of new antimicrobial toxins of low molecular weight called phytoalexins. Phytoalexins were first discovered by K.O. Muller, working during the 1940s on the resistance of potato to the blight fungus Phytophthora infestans. Subsequently they were studied by I.A.M. Cruickshank, working on the resistance of pea to a variety of fungi, and then by many other plant pathologists. Much of the research centred on peas (Pisum sativum) and beans (Phaseolus and Vicia spp.) and their potential pathogens, because the young split pods, with their series of depressions where developing seeds had lain, provided a convenient experimental system for inoculating tissues with drops of water containing spores of a potential pathogen and then, after attempted invasion, for withdrawing them easily for chemical analysis.

It soon became evident that phytoalexins are normally synthesised by the living cells of the plant close to the point of challenge by an avirulent form of a pathogen. The response is a metabolically active one, requiring oxygen, and involving the synthesis of new enzymes rather than the passive conversion of the existing components of dead or dying cells. Furthermore, the production of phytoalexins is triggered by cellular messages synthesised following recognition of an invader as alien. A wide diversity of phytoalexins has been identified, each typical of a particular plant species or group. All are widely fungitoxic and completely non-specific in their activity against pathogens. Any specificity of resistance in which they are involved must therefore be embodied in the recognition process rather than in the mechanism of pathogen death.

The study of phytoalexins was important in the history of plant pathology, for it marked a change of emphasis away from simple observation of resistance reactions and towards the systematic investigation of the cellular and biochemical mechanisms involved.

In addition to the accumulation of phytoalexins, polymers such as callose, suberin and lignin, hydroxyproline-rich proteins and even silica may be synthesised rapidly and deposited in the walls of the living cells adjacent to the hypersensitive site, possibly in response to the general stress engendered within the tissues. These provide further structural barriers to pathogen growth and may also cross-link with the plant’s cell wall components such as hemicelluloses and pectic substances, rendering them resistant to breakdown by fungal enzymes and therefore unavailable as a source of food. Finally, pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins may be synthesised and accumulate at the infection site. Some of these are enzymes such as glucanases and chitinases, capable of breaking down pathogen cell walls. Others bind to pathogen membranes and proteins, including enzymes, and exert an inhibitory effect in this way. They undoubtedly contribute to the toxic milieu in and around the hypersensitive cell.

PR proteins, together with lignin, are also synthesised at some distance from the infection site, even in different leaves on the same plant, and help to repel further invasion attempts by potential pathogens. This so-called systemic acquired resistance, first studied in members of the cucumber family (Cucurbitaceae), is triggered by salicylic acid, a phenolic acid produced or released during the hypersensitive response, but how the signal moves through the plant and how it activates the synthesis of PR proteins is not yet known. A related chemical, methyl salicylate, is volatile and may even be released as a gas by plants attacked by fungi to trigger resistance in adjacent plants. Methyl jasmonate, another gaseous messenger, may also be involved in triggering resistance responses in nearby plants. Such effects of volatiles could explain the efficacy of ‘companion plants’ in preventing disease. For example, the aromatic Artemisia spp. such as tarragon (A. dracunculus), southern wood (A. abrotanum) and wormwood (A. absinthium), which are said to prevent infection in adjacent plants, are known to emit significant quantities of methyl jasmonate.

There may be other products actively synthesised during the basic defence of plants against aliens, but they have not yet been discovered. Any one of the resistance responses is probably capable of preventing or restricting the growth of a potential pathogen, yet most appear to be activated together during defence. Plants thus seem to have adopted a ‘belt and braces’ approach in the evolution of mechanisms for protecting themselves against all possible invaders, which is not surprising given the great diversity of potentially pathogenic microorganisms. Furthermore, the accumulation of toxic factors such as phytoalexins and PR proteins within the hypersensitive cells prevents colonisation by secondary invaders and saprophytes, which might otherwise take advantage of the dead cells as a source of food.

As with the defence of a country, the defence of plants against potential invaders incurs a cost. For example, the synthesis of phytoalexins requires the consumption by the plant of considerable reserves of energy. The effect on the productivity of the plant (or yield in the case of a crop) will inevitably be significant.

The basic defence processes described so far are non-specific and are probably controlled by several genetic factors in both hosts and microorganisms. It is likely, however, that only relatively few genes are involved in triggering resistance and these activate a cascade of responses. This kind of resistance has been variously described as ‘basic incompatibility’, ‘general resistance’, ‘non-host resistance’ and ‘species incompatibility’.

BREACHING THE BARRIERS: NECROTROPHS

Microorganisms that have evolved to become pathogens of particular plant groups have somehow acquired mechanisms for overcoming the basic defence processes of those groups.

For many necrotrophs, like the Pythium spp. that cause damping-off of seedlings, the basic strategy is to kill the host cells with a combination of enzymes and/or toxins before the resistance responses are activated (see here). In addition, some necrotrophs have evolved the capacity to detoxify resistance factors such as phytoalexins and PR proteins, either by breaking them down enzymatically or by binding them chemically. For example Fusarium oxysporum pisi, cause of vascular wilt in peas, has been shown to produce an enzyme capable of breaking down the phytoalexin pisatin, known to be involved in the resistance of peas to attacks by fungi. It has been postulated that some necrotrophs may also produce suppressors of defence processes, although these have been little studied.

The host ranges of necrotrophs are generally very wide, but are nevertheless usually circumscribed in some way. This suggests that different necrotrophs have evolved mechanisms enabling them to attack some groups of plants but not others. Such broad specificity might be explained by the production of enzymes capable of degrading some but not all cellular components. For example, most necrotrophs are unable to attack the woody tissues of trees, this capacity being restricted to pathogens such as Armillaria mellea (the honey fungus), which have evolved the ability to produce lignin-degrading enzymes. Furthermore, the pathotoxins of necrotrophs may not be active against all species of plants. Victorin, the pathotoxin produced by Bipolaris victoriae, cause of Victoria blight of oats, is toxic only to the cells of oat cultivars bred using the rust-resistant cultivar ‘Victoria’ as a parent. The gene controlling rust resistance, it would seem, also causes oat cells to bind the toxin Victorin, causing them to die. Many other necrotrophs produce host-specific toxins. If suppressors of general active defence are produced, they may be active against some groups of plants but not others.

Once a necrotroph has established itself within a host its progress may be impeded, but not prevented, by the wound responses of the plant. These are the reactions that most plants activate, non-specifically, in response to mechanical damage caused by pathogens, herbivorous insects and animals, gardeners or the elements. They are similar to the non-specific defence responses described earlier, but may occur more slowly. They include stimulation of a biochemical pathway called the shikimic acid pathway, which leads to the synthesis of toxic phenolic substances, many of which may be oxidised to dark toxic products like melanins. This pathway also provides the building blocks for the laying down of lignin in the cell wall. In addition, callose may accumulate to wall off the damaged area. Finally corky layers may be formed, creating further structural barriers. Presumably, the interplay between a necrotroph’s pathogenicity factors and the host’s wound responses determines the speed with which the infection spreads and thus the ultimate size of the lesion.

In some cases evolutionary selection may have led to forms of plants in which various aspects of the wound response to particular necrotrophs is exaggerated, leading to a significant slowing down of the progression of the disease. The overproduction of resins in roots of some conifers infected with Heterobasidion annosum, cause of butt rot, is an example of this phenomenon, as is the laying down of corky tissue around infections of potato by Streptomyces scabies, cause of common scab. Many of the components of general active defence (see above) may have had their evolutionary origins in wound responses.

A MORE SUBTLE APPROACH: BIOTROPHS AND HEMIBIOTROPHS

Biotrophs and hemibiotrophs seem to have evolved different strategies from those of necrotrophs for dealing with the plant’s basic defences, enabling them to grow within living cells and tissues and extract nutrients from them. Assuming the presence of a mechanism for penetrating the cuticle, one means by which this could be achieved would be to present no signals to enable the plant to recognise the invader as an alien. This would involve the evolutionary loss or structural modification by the pathogen of all such signal molecules. In this model, which is accepted by many plant pathologists, the plant’s basic defence systems would simply not be activated.

However, given that basic defence processes in plants seem to be activated by a wide variety of factors, many of them non-specific or not even the product of a pathogen, and that biotrophs and hemibiotrophs make extensive growth in the host tissues and modify their metabolism in a multiplicity of ways, it is hard to imagine that basic resistance mechanisms would not be activated at some point. An alternative model, which takes account of this, might be one in which specific suppressors of basic resistance were involved in establishing a particular biotrophic or hemibiotrophic species as a pathogen of a particular plant group. There is, however, as yet only limited evidence to support this hypothesis.

Once a biotrophic or hemibiotrophic species in the past evolved the means of becoming a pathogen of a particular plant group, there would have been strong selection pressure upon the populations of the host for mutants possessing the ability to recognise the pathogen as an alien and to activate resistance. By virtue of their increased capacity to survive infection and therefore reproduce, the progeny of such mutants would increase in the population and the potential food source available to the pathogen would diminish. This in turn would place upon the pathogen population similarly strong selection pressure for new mutants that were not recognised and could thus colonise the mutant form of the host. The process would be repeated over countless generations of both host and pathogen, and this evolutionary tit for tat would result in an elaborate system of different variants of the host and races of the pathogen, creating a highly specific pattern of resistance and susceptibility in the host and of virulence and avirulence in the pathogen. This is exactly the kind of situation we find when we examine the genetic structure of populations of biotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens and their hosts. The evolutionary process is speeded up and the resulting host variety/pathogen race structure accentuated in crop plants such as wheat or potato that have been artificially bred for resistance to the pathogens.

The resistance responses involved in these highly specific interactions appear to be the same as those associated with general resistance: the hypersensitive response and the accumulation of other factors such as structural barriers, phytoalexins and PR proteins.

HISTORIC EXPERIMENTS WITH FLAX RUST

To understand the mechanisms underlying such an elaborate system of resistant varieties and races it is necessary to know something of the genetic basis of the phenomenon. Following the rediscovery, at the turn of the century, of Gregor Mendel’s work on the inheritance of characters in plants, the Cambridge plant pathologist and wheat breeder Rowland Biffen showed that the inheritance of the resistance of wheat to the rust fungus Puccinia graminis conformed to Mendel’s laws. It was not until the 1940s and 1950s, however, that H.H. Flor, working in the United States, provided a clear genetic explanation of what was going on. He worked with flax, Linum usitatissimum, and its rust, Melampsora lini, which is a short-cycle rust (see here) with no alternate host.

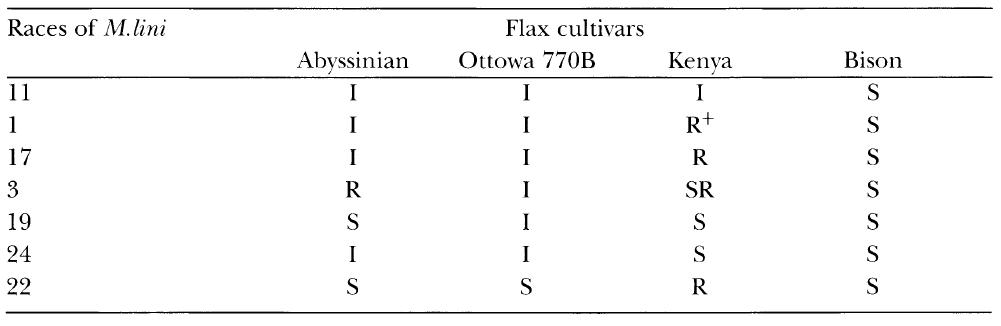

In his first major experiment Flor inoculated four different cultivars of flax – ‘Abyssinian’, ‘Ottawa 770B’, ‘Kenya’ and ‘Bison’ – with seven different races of M. lini and then recorded the results, as set out in Table 3.1. Bison was susceptible (S) to all the races of M. lini, but the other cultivars gave a variety of responses. Flor arbitrarily classified them as immune (I), highly resistant (R+), resistant (R), semi-resistant (SR) and susceptible (S).

TABLE 3.1

Interaction of flax (Linum usitatissimum) and races of flax rust (Melampsora lini). (After Ellingboe, 1984.)

I = immune, R+ = highly resistant, R = resistant, SR = semi-resistant, S = susceptible.

Next he crossed each of the cultivars to ‘Bison’, the universally susceptible cultivar, to determine the number of gene differences between each cultivar and ‘Bison’. He also intercrossed each of the cultivars to determine the number of gene differences between the cultivars, and he intercrossed the different races of M. lini. From all this a basic pattern emerged, illustrated by the simple combination of two cultivars and two races as in Table 3.2.

TABLE 3.2

The interaction between two cultivars of flax and two races of flax rust. (After Ellingboe, 1984.)

From crosses with ‘Bison’ and 13 other cultivars, the progeny being challenged by 12 races of the fungus, it became clear that ‘Ottawa 770B’ possessed a single ‘major’ gene for resistance, which Flor designated an ‘R gene’. This was inherited in a simple Mendelian way and was dominant over susceptibility. Thus the two situations are designated RR and rr respectively. The letters are repeated because, being diploid, there may be two copies of the R genes in each host cell.

Crosses between Races 24 and 22 of M. lini gave the following result:

First generation (F1) – all avirulent on ‘Ottawa 770B’

Second generation (F2) – 75% avirulent and 25% virulent on ‘Ottawa 770B’

The inability to infect a resistant host, avirulence, was dominant over virulence, the ability to infect. Thus these two situations are designated Av and av, respectively. The letters Av are not repeated because the nuclei of M. lini are haploid (i.e. they possess only one copy of each chromosome). In summary then, these simple experiments showed that there was one gene difference between the two hosts and between the two races, the presence or absence of a resistance gene (R gene) and an avirulence gene (Av gene) respectively. Resistance was dominant over susceptibility and avirulence over virulence.

Further experiments by Flor and others revealed additional information about R genes and Av genes, as follows.

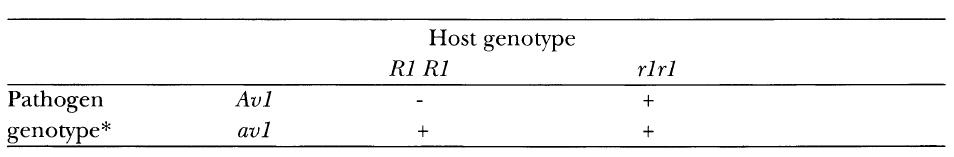

THE GENE-FOR-GENE HYPOTHESIS

Two clear conclusions may be drawn from Flor’s data. Firstly, single dominant genes in the host and pathogen control resistance (R genes) and avirulence (Av genes), respectively. Secondly, resistance reactions (phenotypes) result from the interaction of one R gene with a single, specific avirulence gene. Conversely, a susceptible reaction results if the R gene is absent or recessive in the host, or the Av gene absent or recessive in the pathogen. Thus the range of pathogenicity of a physiologic race of M. lini is determined by pathogenicity factors specific for each resistance factor possessed by the host.

This one-for-one relationship became known as the gene-for-gene relationship. It can be expressed in its simplest form as shown in Table 3.3.

TABLE 3.3

The gene-for-gene relationship.

– = Resistant interaction

+ = Susceptible interaction

The presence of a resistance gene in the host does not of itself confer resistance to the pathogen. It only does so if the attacking pathogen strain possesses the complementary avirulence gene. Where a host possesses two or more R genes, it is only necessary for the attacking fungus strain to possess one of the complementary Av genes for resistance to occur. Thus an interaction involving three R genes and three Av genes might be expressed as in Table 3.4.

TABLE 3.4

The interaction beween cultivars of flax with three R genes and races of flax rust with three corresponding av genes.

+ = Susceptible interaction (growth of pathogen)

– = Resistant interaction (no growth of pathogen)

The gene-for-gene hypothesis and all the other essential features of the interaction of M. lini with flax appear to apply, with minor variations, to most other biotrophic and hemibiotrophic plant-pathogen interactions in crops and in the wild. Among the interactions studied in particular detail are the following: Erysiphe graminis (powdery mildew) – cereals and other members of the grass family (Gramineae); Puccinia graminis (black stem rust) – cereals and other members of the grass family; Bremia lactucae (downy mildew) – lettuce and other members of the daisy family (Compositae); and Phytophthora infestans (blight) – potato and other members of the potato family (Solanaceae). Significantly, the gene-for-gene hypothesis also appears to hold true for the resistance of plants to biotrophic fungi that are not normally pathogenic on them – resistance of barley, for example, to Puccinia graminis f.sp. tritici, which is normally a pathogen of wheat but not barley!

Among the variations to the basic theme, in addition to those listed above, are incomplete expression of some genes, resulting in partial resistance and partial virulence; and the presence of modifier genes which modify the expression of an R gene or an Av gene. In some instances resistance genes may be recessive, as in the case of the mlo gene for resistance of some barley cultivars to Erysiphe graminis. This gene results from a mutation leading to a defect in the mechanism controlling calcium levels in barley cells. Since calcium ions are involved in regulating callose deposition, the mutant lines lose all control over this process and callose is produced very rapidly, walling off the fungus before it is able to extract nutrients from the host cells.

IMPLICATION OF THE GENE-FOR-GENE HYPOTHESIS

The implication of the gene-for-gene hypothesis for understanding the mechanism of host-pathogen interaction is that resistance, being controlled by a dominant gene, must normally involve a gene product in the host that recognises a product of a dominant gene in the avirulent pathogen. This in some way leads to the hypersensitive response and the synthesis of products such as phytoalexins, PR proteins and so on that we have already seen to be involved in basic resistance, and which also appear to be characteristic of specific resistance to biotrophs.

For most of us it is counter-intuitive that a dominant gene in a pathogen should control production of a factor that enables that pathogen to be recognised as an alien and therefore rejected by a potential host. The reason, however, is that the host has evolved to recognise a pathogen product that may have no role in pathogenicity per se, such as a wall or membrane component, or alternatively may be secreted as an aid to pathogenicity (a pathogenicity factor). It is only in the context of interaction with such a resistant host that we think of this as the product of an avirulence gene. In all other contexts the gene is simply a dominant gene specifying a product that is a structural component or pathogenicity factor of the potential pathogen.

A potential pathogen might evolve not to be recognised by a host simply by loss or modification of the gene specifying the product. Providing that such a change was not lethal the pathogen would regain its virulence. The evolutionary response of the host would be to recognise another pathogen product. This might be any similar product of the pathogen genome, which is consistent with the observation that avirulence genes tend to be scattered about the genome, rarely being in allelic series as R genes are.

The host product that recognises the pathogen must be linked in an elaborate way to the resistance response mechanism, which makes it much more likely that the product of a new mutant form of the host is related to the original product. This proposition is consistent with the observation that R genes tend to be arranged in allelic series in the host genome.

RECOGNITION IN GENE-FOR -GENE INTERACTIONS

During recent years great effort has been expended by plant pathologists in attempts to identify the recognition factors involved in the highly specific gene-for-gene interactions. Various candidates were proposed, including DNA, proteins, glycoproteins and polysaccharides, but no definitive answers were obtained. A breakthrough came with the development of the procedures of molecular biology, which made it possible to isolate and clone resistance genes, especially those conferring resistance of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) to races of the hemibiotrophic pathogen Fulvia (Cladosporium) fulva which causes debilitation and eventually necrosis. The story now emerging is that the recognition factors in these hosts, and probably in many other plants exhibiting gene-for-gene resistance to pathogens, are proteins rich in repeated molecules of the amino acid leucine (the so-called LRR proteins). Such compounds could evolve as a series of closely related forms in the way that would be required in gene-for-gene interactions. It seems probable that such recognition factors are often located in the membranes of the resistant host cells, with the part of the molecule involved in recognition orientated towards the outside of the cells and the part involved in activation of defence reactions orientated towards the inside.

Although avirulence genes have also been isolated and cloned from a number of pathogens, including the Avr9 gene of Fulvia (Cladosporium) fulva that interacts with the Cf-9 gene for resistance in tomato, the mechanism by which the avirulent pathogen is recognised is still not known. The Avr9 gene codes for a peptide protein of 28 amino acids, but precisely how this binds to the corresponding Cf-9 LRR protein remains to be elucidated. Peptide avirulence factors have not been identified in all the host-pathogen interactions studied so far. Moreover, how binding is converted to a signal that eventually reaches the nucleus and activates the resistance responses is still not at all clear, although calcium ions (Ca++) within the cell seem to be involved. Free calcium is known to be involved in the regulation of a number of cellular processes in plants. With the rapid advances in molecular analysis of plant pathogen interaction it is certain that significant new information relating to the operation of the gene-for-gene system will be revealed in the next few years.

BACTERIAL HRP GENES

Recent research on the pathogenicity of certain plant pathogenic bacteria merits special mention, for it may throw further light on the process of recognition in plant-pathogen interaction.

In addition to possessing genes controlling the synthesis of cell-degrading enzymes, toxins and other general pathogenicity factors, bacteria have also been shown to possess clusters of additional genes that are essential for pathogenicity. Mutants in which the genes have been deleted are not only nonpathogenic, but also lose the ability to elicit a hypersensitive resistance response in host cultivars carrying R genes. The genes have therefore been designated ‘hrp genes’ (hypersensitive response and pathogenicity genes). They have been studied most extensively in forms of Pseudomonas syringae that infect a variety of plant hosts, including tomato, Xanthomonas campestris pv vesicatoria, which causes bacterial spot on tomato and pepper (Capsicum annuum var. annuum), and Erwinia amylovora, cause of fireblight on members of the rose family (Rosaceae).

Some experiments have shown that hrp genes are not active when the bacteria are grown in culture on media rich in nutrients. They are activated immediately, however, when the bacteria are transferred to a starvation medium. This suggests that in nature it is the nutrient-deficient state of the region between the cells of the host, which a pathogenic bacterium encounters as soon as it has passed through a stomatal pore or other opening, that activates hrp genes. Specific compounds such as sulphur-rich amino acids normally found in the spaces between plant cells may also be important triggers. Only some of the hrp genes are involved in ‘recognising’ the host environment. Once activated, however, they switch on the rest of the hrp genes, some of which synthesise proteins important in building channels through the bacterial membrane to enable the bacterium to pump into the host cell the enzymes that degrade cell walls and proteins, and other substances important in pathogenesis.

Very recent research with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato has suggested that one of the pathogenicity proteins pumped into the host cell in this way is the protein product of the avirulence Pto gene. In tomatoes carrying the corresponding R gene, this is recognised inside the cells by the serine-threonine protein kinase, the primary product of the resistance gene, and the cascade of reactions associated with hypersensitive resistance is then switched on.

It seems possible that plant hosts have evolved to recognise specific bacterial proteins pumped into their cells during, and as an aid to, pathogenesis, and this leads to activation of their resistance responses and exclusion of the pathogen. It is possible that biotrophic fungi produce similar pathogenicity substances, perhaps secreted by haustoria, and that these also function in triggering resistance.

SUPPRESSION OF RESISTANCE

It may be argued, especially from experiments performed with potato and Phytophthora infestans, and cereals and Erysiphe graminis, that virulence of a pathogen may in some circumstances result from the secretion by the pathogen of substances capable of suppressing host resistance responses. No chemical substance has been positively identified as a resistance suppressor, nor has a satisfactory explanation been produced to suggest how such a system, in which virulence rather than avirulence would be dominant, could be consistent with the genetic data supporting the gene-for-gene hypothesis. Nevertheless, it remains an intriguing possibility and it is hoped that future research may provide further evidence to support or refute it. One possibility is that suppressors may be involved in determining the basic compatibility between a host and pathogen, but not in mediating the race-specific gene-for-gene interactions.

IN SUMMARY

We have seen how plants have evolved a variety of structural and chemical barriers and active processes to prevent or repel attacks by the vast majority of potential pathogens, and therefore remain healthy. We have also seen how some organisms have evolved mechanisms to overcome the plant’s basic resistance processes and become pathogens, and how plants have in response evolved additional mechanisms to recognise these as aliens and repel them. And we have seen how pathogens may circumvent these additional lines of defence. Knowledge of such matters enables the plant pathologist to understand better the distribution and dynamics of disease in natural populations of plants (see Bibliography). It also helps plant breeders to develop ways of controlling disease in crops by selecting and breeding resistant cultivars. Finally, as more is learned of the molecular biological control of disease resistance and of pathogen variation, it makes possible the application of the techniques of genetic engineering to produce the disease-resistant crop plants of the future by isolating resistance genes from one species or cultivar and transferring them to another in wide crosses that could not be achieved by conventional plant breeding methods.