![]()

Whereas large pathogens, the plants that parasitise other plants, are measured in metres and millimetres, smaller pathogens, the bacteria and viruses, are measured in micrometres (= μm or 10 -6 m) and nanometres (10 -9 m), each measurement being a thousand times smaller than the last. Fungi, which have been our major concern so far, fall in the middle of this range, being measured in μm; thus the oospores of Phytophthora are 30–60 μm in diameter and the ascospores of Sclerotinia are approximately 10 x 6 μm. Bacteria are about ten times smaller than the fungi: the cells of Erwinia carotovora, for example, are about 1 μm in length, this being about ten times their breadth. And the viruses are at least 1,000–10,000 times smaller than the bacteria!

Bacteria, like the fungi, have a cell wall composed of complex carbohydrates and a protoplast made up of membranes, cytoplasm and organelles. The nuclear apparatus is less precisely delineated than in the fungi, with no enclosing membrane, but the presence of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and genetic evidence for a linear arrangement of genes suggest a certain similarity to the nucleus of fungi and higher plants. The viruses, by contrast, have no cellular structure and have a central core of ribonucleic acid (RNA) or, in a limited number of cases, DNA; genes can be identified in both the RNA and DNA. The nucleic acid is contained within a protein coat. There are some organisms intermediate between bacteria and viruses, the mycoplasmas, and some ‘viroids’ which consist of circular low molecular weight RNA without a protein coat. These are probably the smallest pathogens of all, where we include the prions, the proteins thought to be the causal agents of some encephalopathies.

The flowering plant parasites of other flowering plants (there is one known conifer parasite of another conifer) can be very large. Members of the mistletoe family, Loranthaceae, can reach the size of a large bush in the crowns of tropical trees, and Rafflesia spp., which live in the roots of tropical vines, have a vegetative body impossible to measure, but it must be of considerable size to nourish the periodic solitary flower, one of which was found to weigh 5 kg. That said, the flowering plant parasites, if they are to survive, must not be larger or more voracious than their hosts can tolerate.

At the other extreme the viruses and viroids have constraints at the molecular level: the infectious virus particle must contain sufficient nucleic acid to programme the continued multiplication of the nucleic acid and the production of the protein coat; also, these organisms are completely dependent on a living host in order to reproduce, for although all the genetic information to reproduce a new virus or viroid particle is contained within the DNA, the biosynthetic machinery of the host must be harnessed to synthesise the new nucleic acid and protein molecules. Despite this, it is not unknown for viruses to cause a slow decline of a host, but this usually allows plenty of time for further spread to another host before death finally occurs.

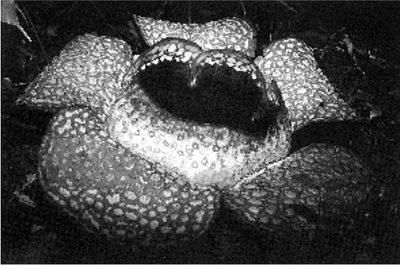

FIG. 12.1

Variegated Abutilon striatum at Downing College, Cambridge, England. The variegation is caused by a viral infection. (D.S. Ingram.)

Being non-mycelial and composed of single particles or cells, the viruses and bacteria have evolved very different mechanisms from the fungi for infecting their hosts. Viruses sometimes enter through transient wounds but are more often carried by a vector such as an insect that feeds on plants or a fungus that infects plants. Bacteria are occasionally carried by vectors but more usually enter a host through a wound or via the stomatal pores.

THE VIRUS DISEASES OF PLANTS*

From the earliest historical times there are written accounts that probably refer to virus diseases of animals and man such as those subsequently identified as smallpox, foot-and-mouth disease and rabies. But it was not until the early nineteenth century that Louis Pasteur reported that no microscopically identifiable organism could be found in infectious fluid causing rabies, and suggested that pathogens might exist that were too small to be seen. The effect of viruses on plants was first recognised in the sixteenth century, when the ‘breaking’ of flower colour in tulips became a common subject for early flower painters, especially in Holland. This condition is now known to be of viral origin, the single base colour of the tulip flower giving way to complex patterns of white or yellow stripes where it has been eliminated from the epidermal cells. By the eighteenth century various degenerative diseases of potatoes were recognised but not categorised, and many of these were probably of viral origin. ‘The curl’, a disease of potatoes now variously ascribed to potato leafroll virus and/or a mixture of the viruses producing severe mosaic symptoms in potatoes, was a cause of crop failure at the time of the potato blight epidemics in the nineteenth century, and in 1869 the variegation of Abutilon striatum (Fig. 12.1), a decorative plant used extensively in Victorian conservatories, was found to be infectious when variegated scions were grafted on to green stocks in the course of propagation.

This was all circumstantial evidence for the existence of a ‘new’ infective agent until Mayer, in 1886, transmitted tobacco mosaic disease to healthy tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants using juice from infected plants, and Ivanowski, in 1892, showed that the juice containing this tobacco mosaic-inducing agent remained infective after passage through bacteria-proof porcelain filters. Nobody paid much attention until in 1898 the great microbiologist Beijerinck independently confirmed these results and referred to the filter-passing material as a contagium vivum fluidum. Also in that year it was shown by Loeffler & Frosch that foot-and-mouth disease of cloven-hoofed animals was caused by an agent that passed the bacterial filters. At about the same time, Erwin Smith (who later went on to study plant bacteria – hence Erwinia) suggested that peach yellows disease in the United States, for which no pathogen was known, might be transmitted to healthy plants by leafhoppers. In fact it was later shown to be caused by very small xylem-inhabiting bacteria near the limit of light microscope resolution, but the research was important because it focused attention on the possibility that viruses could be transmitted by insects.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, viruses were being recognised and described, the mechanisms for their transmission from host to host were becoming apparent and methods for infecting plants experimentally were being worked out. This provided enough information for a measure of practical control of the diseases, but was not intellectually satisfying for it did not solve the mystery of the contagium vivum fluidum. Then in 1935 W. M. Stanley at Princeton University in the USA isolated and purified a protein from tobacco mosaic which he obtained as crystals. This substance retained its infectivity even after successive recrystallisations and after considerable dilution; moreover it was powerfully antigenic and when injected into rabbits yielded a serum that reacted with the sap of diseased plants. Stanley was careful to point out, however, that purification of proteins was difficult and he anticipated that his claim would require modification, as indeed it did. In 1937 Bawden & Pirie showed that the ‘protein’ from diseased tobacco was in fact a nucleoprotein appearing as liquid crystals comprising 5% RNA and an associated protein, and in 1938 the tomato bushy stunt virus was shown to contain 15% RNA in addition to a viral protein.

Once methods of transmission by grafting, sap inoculation or insects had been worked out it became possible to give some identity to viruses in terms of their transmission characteristics and the range of hosts they attacked, but their taxonomy still remained difficult. With the establishment of the chemical nature of viruses, however, the way was opened for their study using a variety of chemical and physical techniques. Thus it was found that some were rod-like (tobacco mosaic virus), consisting of a coiled chain of RNA enclosed within regularly positioned protein molecules, which formed a protective coat (Fig. 1.15a)This protein coat, in different forms, was characteristic of particular viruses and a consistent accompaniment of the virus particles, but was not necessary for infection. In other viruses, tomato bushy stunt and turnip yellow mosaic for example, the virus particles were arranged in a somewhat spherical structure with the protein sub-units arranged in a lattice to form the surface of an icosahedron (Fig. 1.15b). The nucleic acid was closely associated with the inner portion of this protein shell in a regular pattern. Crick & Watson, who with Wilkins & Franklin first solved the puzzle of the arrangement of the nucleic acids in chromosomes, described the structure of small viruses in 1956, and there is no doubt that the X-ray crystallographic study of tobacco mosaic virus was an important precursor of their later work on the helical structure and base pairing in DNA.

But before chemistry took over, two important techniques were used in the quantitative study of viruses, based on their ability to form local lesions and on their antigenic properties. The first technique resulted from the discovery by Francis Holmes in 1928 that tobacco mosaic virus produced systemic mottle symptoms in the ‘Burley’ variety of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), but when inoculated in precisely the same way onto the leaves of N. glutinosa produced a dark spot at each infection point – a ‘local lesion’. It was thus possible to establish a relationship between the concentration of virus particles in a sample and the number of local lesions produced on a reactive leaf. Similarly, viruses could at lower dilutions be very precisely identified and quantified using serum precipitation tests and other technically more complex serological methods.

Since then, more refined techniques have been developed, such as the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), where an enzyme-labelled antibody binding to a virus sample precipitates and digests an added enzyme substrate, with consequent colour change; the intensity of the colour change gives a measure of the virus present in the sample. Immunological techniques are not the normal tools of the naturalist, and indeed because of the stringent regulations surrounding their production and use are only likely to be available to research professionals, but it is useful to be aware of their contribution.

However, a great deal of useful field work on the viruses of wild plants can still be carried out using routine tools of the virologist such as grafting and sap inoculation. Successful horticultural grafting for long-term permanent growth is a difficult technological operation but such refinement is not needed for virus transmission; it is sufficient for a temporary union to take place. This may be achieved with simple wedge grafts on herbaceous as well as woody material; with patch grafts on woody material, where pieces of bark cut with a standard cutter are exchanged with similar sized pieces removed from the potential host; with standard budding techniques; and in some instances (e.g. Citrus spp.) with a cut piece of leaf or strip of other tissue imprisoned under a flap of bark on the potential host, where it makes a temporary union, allowing transmission to occur.

For all virus work a source of virus-free seedlings is also necessary. While more complex work requires such seedlings to be grown in an insect-free glasshouse, simple diagnostic work can be carried out at cooler times of year with seedlings grown and maintained in a normal glasshouse, without special exclusion of insects, provided routine spraying for insect control is maintained and sufficient numbers of uninoculated plants are used as ‘controls’.

Sap transmission remains a convenient method for comparative work on the viruses of a number of annual plants. The method used is to grind up symptom-bearing leaves of the donor plant and to rub the juice, roughly filtered through muslin, onto the surface of the tester plant. It is usual to add a small quantity of a fine abrasive such as carborundum powder to the juice to create small wounds on the leaf surface. After this inoculation procedure the juice is washed off the leaves and the plants returned to the glasshouse. With highly infectious viruses like tobacco mosaic virus or cucumber mosaic a high level of transmission will be obtained. Some plants have high levels of inhibitory substances such as tannins in their leaves and it is necessary in these cases to use phosphate buffers or additional reducing agents such as sodium sulphite to achieve adequate transmission. With new and previously unknown viruses it is a matter of trial and error to find the right conditions for transmission, and sometimes transmission by sap inoculation proves difficult or erratic until the virus has been obtained from a more suitable host.

Viruses can be transmitted in nature by other biological means, such as insects with sucking mouthparts, as with aphids and potato virus Y, mealy bugs and cacao swollen shoot virus, leafhoppers and rice dwarf and maize mosaic viruses, thrips and tomato spotted wilt, or white flies and cotton leaf curl. Others may be transmitted by insects with biting mouthparts, for example flea beetles and turnip yellow mosaic. The transmission pattern shown by these insect-virus combinations varies. Many of the aphid-borne viruses are transmitted to the new host immediately after feeding and the insect does not remain infective. Here the mouth parts of the insect appear to act like a dirty syringe which carries some virus with it into the tissues of the new host. Other viruses transmitted by aphids, leafhoppers and beetles are ingested and the insect does not immediately transmit the virus, a latent period of 12 hours or more being required to allow the insect to become infective. Once infective it remains so for at least a week. There is evidence that these ‘persistent’ viruses pass from the gut of the insect and circulate in the body fluid, eventually reaching the salivary glands. From the salivary glands they are injected together with the saliva into the vascular elements of the plant when the insect next feeds, and thus reinfect. In some virus-insect combinations there is evidence that the virus multiplies within the body of the insect and may even be included in the eggs, thereby being passed to a subsequent generation.

Insect transmission may be routinely used in the study of viruses, but is probably not the vehicle of choice for the amateur seeking to make sense of a virus problem. The same is likely to be true of the soil fungi or nematodes which transmit soil-borne viruses, but they too are of considerable intrinsic interest. In some fungi, such as Olpidium brassicae (see here), the zoospores pick up the virus from the soil solution around the roots of infected plants and, swimming to a new host, carry the virus into the roots; there is no long term association between fungus and virus. In Spongospora subterranea (see here) the virus is incorporated into the fungal tissue during parasitism of a virus-infested plant, and the particles enter the resting spores, where they are maintained for a long period before a new host is infected by the fungus and the virus transferred at the same time.

Eelworm transmission is usually by members of the free-living genera Trichodorus and Paratrichodorus. These carry the Tobra viruses responsible for tobacco rattle disease, which affects potatoes and bulbs and other hosts as well as tobacco. Similarly, free-living eelworms of the genera Longidorus and Xiphinema carry the nepoviruses, including arabis mosaic, grapevine fan leaf, raspberry ringspot and many others. In the transmission of viruses by eelworms the infected sap, including the virus particles, is sucked from the plant root and the virus particles are adsorbed onto the walls of the pharynx and oesophagus. They are in part released when the salivary fluid is injected into a new host during feeding. There is no evidence of multiplication of the virus within the eelworm vector.

Viruses are also sometimes passed from plant to plant by way of the seed. This is not a common happening, but in lettuce mosaic, for example, identification of mosaic infection of mother plants (which leads to seed infection) is one of the important steps in controlling the disease. Transmission through vegetative propagation is often the reason for the deterioration of stocks of vegetatively propagated crops such as potatoes, raspberries, strawberries, fruit and ornamental trees and bulbs. Once the damaging effects of the resulting diseases were recognised a number of methods of obtaining disease-free stocks were developed. Thus it was found in the 1940s that if the apical meristem was surgically excised from an infected plant and then grown on in culture, a virus-free plant might result which could then serve as the basis for the production of new virus-free clones. Viruses are often absent from the apical meristem of plants and this explains their elimination during meristem culture; sometimes too they seem to die out during the culture process itself, perhaps because of destabilisation of the delicate balance between host cells and pathogen. Virus elimination may be aided by keeping the infected plants at high temperatures; this appears to reduce the relative amount of virus in the tissues and makes it easier to excise virus-free apical meristems.

Other methods of dealing with viruses in crop plants include the use of resistance genes, or control of the vector using appropriate insecticides or fungicides.

Finally it should be mentioned that both fungi and bacteria, as well as plants, may be attacked by viruses. Evidence for their existence can be found in many fungi, but particularly in the watery stipe disease of cultivated mushrooms, where infection leads to the collapse of individual fruit bodies. Virus infections are also responsible for the reduced parasitic vigour that can occur in the fungi responsible for chestnut blight and Dutch elm disease (Chapter 6). In bacteria the virus parasites are called phages and may be revealed experimentally as plaques (circular translucent areas of dead bacteria) on agar plates seeded with the host bacterium. These viruses, as in the T2 phage of Escherichia coli, may have a protein coat, and under the electron microscope can be seen to have a distinct head and a tail. The virus becomes attached by the tip of the tail to the bacterial surface and the nucleic acid contained within the protein coat finds its way through the modified tail tip into the bacterial cell, where it multiplies.

The biology, particularly the ecology, of viruses is full of interest. Some are true latent viruses carried in the host with no visible symptoms (see here). Others may produce severe initial symptoms and then settle down to a more or less symptomless phase. Thus the cacao swollen shoot disease occurs in forest trees related to cacao without apparent symptoms unless the tree is coppiced, when infection may show in the coppice shoots. Inoculation of seedlings of the natural host with the virus leads to initial symptom production, which gradually becomes less apparent. However, inoculation of cacao leads to marked symptoms and a slow decline of the tree, the rate of decline differing with viruses of different origin.

Other viruses are dependent on the ecology of their insect vectors. For example, potato virus Y is carried by the aphid Myzus persicae; the eggs of this insect overwinter on the shoots of trees of the genus Prunus (e.g. cherry and plum) and on hatching pass through several wingless generations before giving rise to a winged generation which moves to surrounding herbaceous plants, including the potato. In the potato field the aphids multiply in discrete areas of the field and when these become crowded migrate, by crawling or by producing further winged forms, to spread through the whole crop, taking any virus infection with them. In cool conditions the build-up is less and in cool windy conditions the distant spread of the aphids by flying is inhibited; for this reason the production of virus-free seed potatoes is restricted to cooler and hillier regions such as Scotland.

The eelworm vectors of the viruses of potatoes, bulbs and soft fruits are less susceptible to environmental changes above ground. Longidorus and Xiphinema, for example, live mainly on the roots of hedgerow trees and shrubs, from whence they spread inwards to the area of cultivation.

The naturalist is unlikely to become acquainted with viral diseases in the same way as with fungal diseases. However, there are some that are worth looking for. Many viruses occur on raspberries and related plants both in the wild and in gardens, producing symptoms such as mosaic, yellowing of the veins, banding of the veins (yellow and brown) and changes in the morphology of the plant such as curled leaves and reduced side shoots. Potatoes are no longer a source of readily available virus symptoms, except where gardeners save their own seed, since commercial seed potatoes (tubers) now have very high health standards and stocks are renewed from healthy mother stocks on a recurring basis. There are a number of rose viruses in the USA, Australia and Europe, however, which may sometimes be found in collections of older varieties. A range of symptoms may be observed including mosaic, yellow leaf flecks and stunting, probably caused by rose mosaic virus, strawberry latent ringspot virus and rose wilt virus respectively. Cucumber mosaic virus is capable of attacking a wide range of hosts in the garden and glasshouse, being found not only in marrows (Cucurbita pepo), courgettes, cucumbers, tomatoes and melons (Cucumis melo) but also in a wide range of ornamental plants such as aquilegia (Aquilegia spp.), delphinium (Delphinium spp.), lupin, geranium (Pelargonium spp.) and aster. We see it commonly in Christmas roses such as Helleborus niger and H. orientalis. In the former it appears to be responsible for the rapid decline in vigour that affects some stocks; in the latter it produces mosaic, vein banding and occasionally ring spot symptoms on the maturing leaves but does not obviously hasten the plants’ decline.

Any unusual morphology or discoloration in wild plants that cannot be attributed to known fungal diseases may be investigated for possible viral origin. But be warned, this is not a road one can go down lightly; the study of viruses needs organisation and resources that can be provided only by the most dedicated amateur worker.

THE BACTERIAL DISEASES OF PLANTS

The morphological variety of bacteria is not great: they may be rod-shaped (sometimes with clubbed ends), spherical (cocci), comma-shaped or spiral. These variously-shaped cells may appear as single entities or grouped in twos (Diplococcus), in chains (Streptococcus), in groups like bunches of grapes (Staphylococcus) or in packets (Sarcina). The individual cells may or may not have flagella, and these appear in different positions and in different numbers on the cells with such regularity that they can be used as criteria for classification, as can the enclosing cell wall, which may appear as a structure that only reveals its presence when stained or may be surrounded by a well-marked mucilaginous wall (largely polysaccharide), the capsule. This last is sometimes only formed if the bacteria are grown in culture. In non-encapsulated bacteria a particular staining technique has proved useful in differentiating two groups, Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The procedure uses the crystal violet stain followed by a mordant such as iodine to stain the cells, already dried and fixed on a slide; washing with dilute ethyl alcohol or acetone removes the stain in a number of instances but leaves it completely fixed in others. This procedure, discovered empirically by a Danish bacteriologist called Gram, appears to distinguish some fundamental property of the wall and of the cell, and is used as a criterion in the classification of bacteria, together with their limited morphology.

By contrast the metabolic activities of the bacteria are very varied. They actively metabolise components of substrates presented to them and secrete into their environment a wide variety of other materials, particularly enzymes. These may be coded not only by the bacterial chromosome but also, in some cases, by a piece of extra-nuclear DNA called a plasmid. Plasmids are infective and may be passed from one bacterial cell to another. Whether they may be regarded as sub-viral parasites of bacteria is a moot point. The metabolic properties of bacteria, along with the morphological features already mentioned, are used in the detailed identification and classification of the organisms, and are of great importance in determining their pathogenic behaviour: most are necrotrophs although some have an interesting biotrophic behaviour. Bacteria also have a rapid multiplication rate, especially in higher temperatures; they are in general, therefore, pathogens of the tropics although some can multiply and spread under temperate conditions.

A few plant pathogenic bacteria are Gram-positive. The genus Clavibacter, for example, with rod-shaped cells lacking flagella, is responsible for a large number of vascular diseases, especially wilts. The genus contains a number of well-marked species and also, within some species, subspecies which are confined to separate hosts but are otherwise not separable. Thus the tomato canker and vascular wilt originally attributed to C. michiganensis is now thought to be caused by a subspecies C. michiganensis ssp. michiganensis. Other forms, such as C. insidiosus, which causes wilt in lucerne and C. sepedonicus, which causes ring rot and wilt in potatoes, are now included in C. michiganensis as ssp. insidiosus and ssp. sepedonicus respectively. This taxonomic complexity is mentioned here because it reflects the pathogenic behaviour of the bacteria, where one species is capable of forming distinct, specific, pathogenic relationships with different plant genera whilst retaining the same morphology and basic biochemical equipment.

Ring rot of potatoes is a particularly damaging disease worldwide. It has caused much loss in the USA and Canada and is prevalent in northern Europe, although currently it is not present in Britain on any permanent basis. In Britain quarantine is maintained with careful scrutiny of samples of all imported potatoes. This is particularly important because field symptoms tend to appear late and may not reveal the existence of the disease before the crop foliage has been burned down and the tubers dug at an early date (a good practice for the control of other diseases). Apparently healthy tubers may thus contain the organism, and it is the planting of infected tubers that spreads the disease; the vascular system of emerging shoots is invaded, as is that of the stolons on which the new tubers will be borne. Of these tubers some may be lightly and some heavily infected; the former give rise to infected plants in their turn while the latter rot in the soil. The bacteria from these rotting tubers do not infect other tubers or succeeding crops, for they do not persist in the soil from season to season. The spread and intensity of the disease is greatest where potato tubers are cut up to supply seed for the next crop, since cross contamination occurs when unsterilised knives carry the bacteria to freshly cut xylem vessels.

A disease caused by Clavibacter spp. that the naturalist could look out for is that caused by C. rathayi on cocksfoot. Here the inflorescence is covered with a yellow slime and the flowering structure dwarfed. It is occasionally seen in Britain and is sometimes a serious problem in mainland Europe. Possibly the same or very similar organisms attack bent grasses (Agrostis spp.) in the USA and wheat in a number of subtropical countries. In these hosts the bacteria are spread by the eelworms Anguina tritici and A. graminis. On their own, Anguina species cause individual wheat grains to swell, forming ‘corn cockles’. The biology and taxonomy of C. rathayi and its allies need to be examined further, particularly in wild grasses, and this could be achieved by means of straightforward field studies to determine host ranges.

The genus Pseudomonas (Gram-negative organisms with rod-shaped cells bearing single or multiple polar flagella) contains a large number of species responsible for plant diseases, including P. solanacearum and P. syringae. P. solanacearum causes the brown rot of potatoes and is, like Clavibacter, a vascular disease, but is not confined to the vascular tissue and breaks out to invade and rot the cortex of the potato tuber. Furthermore, it can contaminate and invade tubers in the soil. It occurs in at least three races, each of which is further divided into pathotypes (fine divisions of a species classified in terms of pathogenicity). The races here attack (1) hosts in the potato family (Solanaceae) but not potato itself (and in culture produce a dark colour because of the action of the enzyme tyrosinase on phenolic chemicals); (2) potatoes (isolates show a weak tyrosinase reaction); (3) the banana and its relatives (isolates of this race show no evidence of tyrosinase production).

In potatoes the disease is widespread in warmer parts of the world, is present in mainland Europe and has recently been identified in imported seed in Britain. It is not restricted to seed transmission, in which it differs from ring rot. Rotting tubers release bacteria which can gain entry to a new host through injured roots or wounds on the stem and also via the stomata, where they enter the substomatal chamber, multiply and destroy the surrounding tissue by means of enzymes.

Pseudomonas syringae is a name used for a number of disease organisms once separately identified as distinct species; now they are thought to be pathogenic forms of the single species, and about 50 pathotypes have been identified. These include the pathotypes causing halo blight of oats, halo blight of beans and celery leaf spot, which contrast with pathotypes causing wilt and canker on the twigs of woody plants with associated leaf infection as in, for example, lilac blight, Prunus stem canker (especially of cherry and plum), poplar canker and the olive knot and ash canker. Infection takes place through stomata, lenticels or wounds. Invaded areas may exude bacterial slime which is further spread by rain splash, and reservoirs of infection in the tissues may give rise to later infection when the organisms are in turn released. Infected leaves often remain attached to the stem into the autumn and winter. In cherry and plum the bacterium invades the cortex of the young shoot through a leaf base or lenticel, and killing the tissue causes splits in the bark. Depending on the success of infection the bacterium at the edge of these splits may advance into neighbouring healthy tissues to form a canker, and may even expand sufficiently to ring the stem. Control in all these forms of P. syringae depends on an intimate knowledge of the individual pathogen and the introduction of sprays or pruning to remove infection foci at appropriate times.

One other important group of bacterial plant pathogens is found in the genus Erwinia, which is characterised by Gram-negative rod-shaped cells with flagella produced generally over the whole surface of the cell (Fig. 1.14). E. amylovora is responsible for the notorious fireblight disease of members of the rose family (Rosaceae) such as apple, cotoneaster (Cotoneaster spp.), hawthorn and pyracantha (Pyracantha coccinea). About a hundred hosts have been recorded. The bacteria overwinter in cankers which begin to ooze in the spring, whence bacterial cells are carried to the flowers by insects and spiders. The invaded flowers become water-soaked and then darken and dry to give a burnt appearance, hence the name fireblight, and as the disease spreads to the leaves these too take on a burnt appearance. The bacteria produce a non-specific polysaccharide toxin called amylovorin which plays a significant role in symptom development. Some host varieties are able to resist attack by the toxin, but in general the disease must be controlled with chemical sprays and by pruning.

Altogether there are more than twenty taxonomic entities in the genus Erwinia that are recognised as producing disease. E. carotovora, in various pathotypes and subspecies, is responsible for a range of soft rots of carrot (Daucus carota), beet, rhubarb (Rheum spp.), rhizomatous iris (Iris spp. hybrids) and so on. The subspecies E.c. carotovora, which grows at higher temperatures in the range 36–7°C, and rapidly rots the host tissues, is responsible for the soft rot of vegetables in store or in transit. E.c. ssp. atroseptica causes the blackleg disease of potato, which extends from the infected tuber as a vascular wilt and then rots the stem bases; tubers for the next season may be infected and rot in store. However, all rotting of potatoes cannot be attributed to this organism and the complex of closely related organisms attacking potato needs expert assessment. What is clear is that a variety of rotting organisms allied to this bacterium can be found in the soil, in association with roots and in watercourses, and in favourable moist, warm conditions these will rot potatoes. In the days before temperature-controlled stores were common, if potatoes slightly infected by Phytophthora infestans found their way into a store the disease would spread within the individual tubers, and although it would not spread from tuber to tuber the moisture given off in the course of infection would, under particular conditions, condense on the surrounding tubers and activate various organisms related to E. carotovora to rot the tubers. If this went on unnoticed large tonnages could be lost.

A distinct species of Erwinia, E. salicis, causes watermark disease of the cricket bat willow (Salix alba var. coerulea) and other willows, in the eastern counties of England. This bacterium occurs in the xylem vessels, where it spreads and causes a brown staining and watermark which spoils the wood for cricket bat production. The bacterium enters the tree through small insect wounds and is spread when larger insect wounds allow the bacteria to exude and be picked up in turn by biting and sucking insects. The leaves of recently infected branches turn brown and these brown ‘flags’ at midsummer are characteristic indications of the disease, easily seen on railway journeys through East Anglia.

FIG. 12.2

Nitrogen-fixing nodules on the roots of broad bean (Vicia faba). (Debbie White, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.)

All these bacteria share a common property: they can only enter the plant by accident or by force: by accident when a stem breaks or a knife cuts or an insect bites, introducing the bacteria into the xylem; and by force when the bacteria spread via water droplets to the plant surface and find their way into the substomatal chamber or lenticel, where they multiply and secrete enzymes that destroy the cells ahead of them and allow invasion. They are in both these situations behaving as very successful necrotrophs.

The relationship between bacterium and plant may, however, be much more intimate. For example, there are two Gram-negative species which are not destructive of the host tissue in the normal sense and which depend on a close integration with the metabolism of the host for their survival and multiplication. They are difficult to place taxonomically. The first is Rhizobium leguminosarum, which in a mutualistic relationship causes nodules to form on the roots of plants in the pea family (Leguminoseae); these can easily be seen if pea or bean seedlings are gently dug up and their roots washed free of soil (Fig. 12.2). In the nodules gaseous nitrogen from the atmosphere is fixed into soluble nitrogenous salts. In simple terms the green plant supplies carbohydrate to the bacterium and in turn receives a supply of nitrogen in excess of that present in the soil, hence the ecological role of many legumes as pioneer colonisers of infertile ground. The organism has a wide range within the Leguminoseae, but particular legumes such as clover and lucerne (alfalfa) are infected by specialised strains of the organism. The bacteria do not produce spores but seem capable of surviving for long periods in the soil in the absence of a host. There is a gradual linear decline in their presence in soil over several years but figures of ten years or more are quoted for their survival in air-dried soil.

The bacterial cells multiply in the soil around the seedling root to be infected, causing curling and branching of the root hairs, a symptom which may be induced by the bacterial conversion of tryptophan, released by the roots, to the plant hormone indoleacetic acid. The bacterial cells then become attached to and penetrate the root hairs, forming an infection thread that grows along the root hair into the body of the root; this penetration process may be aided by the release of cell-softening enzymes such as polygalacturonases. Changes in plant hormone levels as a result of bacterial activity cause the cells to divide and a nodule to form, and Rhizobium cells are released from the infection thread into these living nodule cells, where they are enclosed by an extension of the plasmalemma. The bacteria finally enlarge and differentiate into spherical or branched nitrogen-fixing cells called ‘bacteroids’. The mature nodule is a highly organised structure with an inner core containing the bacteroids and a growing outer region. Xylem and phloem vessels connected to the host’s plumbing system maintain a supply of water, mineral ions and carbohydrates to nurture the bacteroids and carry nitrogenous salts to the rest of the plant.

The nodule is also highly organised biochemically to support the nitrogen-fixing activity of the bacteria while preventing damage to the host cells. This is well illustrated by the processes which protect the nitrogenase enzyme responsible for fixation from being deactivated by oxygen, to which it is sensitive. Oxygen is essential to the metabolism of the host cells, so a supply must be maintained. Root nodule cells contain the reddish pigment haemoglobin which binds oxygen in a similar way to the pigment of animal blood cells, and this oxygen can then be released into the plant’s respiratory pathways direct from the haemoglobin, without reaching the bacteroids. Such is the level of integration between the metabolism of the plant and bacterium that the haemoglobin is probably synthesised jointly, with the bacterium producing the oxygen-binding ‘haem’ portion of the molecule and the plant producing the colourless protein to which it is attached.

Agriculturally, the nodule-forming bacteria are of great importance. There appears to be a reservoir of symbionts in the soil for indigenous crops such as the clovers in Europe, but exotic crops such as lucerne in the UK, soya (Glycine max) in the USA and subterranean clover in Australia require initial inoculation of the seed with a compatible strain of the bacterium. Estimates of the world production of nitrogen by Rhizobium (in wild and cultivated plants) suggest an annual yield of 1,000 million tonnes. In conventional temperate agriculture it is reckoned that a hectare of clover/rye grass sward will fix about 200 kg of nitrogen annually to yield over 7,500 kg of dry matter, compared with a potential yield of 11,000 kg of dry matter from an application of 400 kg of fertiliser nitrogen. Clearly, so long as fertiliser nitrogen is cheap there is no commercial advantage in relying on legume nitrogen, although in environmental terms the reverse may be the case.

Nitrogen-fixing nodules are also formed on the roots of some shrubs and trees, but here the cause is not a bacterium but a Streptomycete, an organism intermediate between a bacterium and a fungus. For example, species of alder form nodules in association with members of the Streptomycete genus Frankia and these can be seen if young alder roots are carefully excavated. A related Streptomycete species, Streptomyces scabies, causes the common scab disease which mars the skin of so many potatoes.

The second bacterium with a close biotrophic relationship with its host is Agrobacterium tumefaciens, which causes crown gall tumours in a wide range of dicotyledonous plants (Figs. 12.3 and 12.4), but is not known to attack monocotyledons. The bacterium, which can survive in soil, gains entry to its host through wounds and is particularly troublesome in nurseries, where the stem and root pruning of plants for sale leads to the later development of tumorous growths, particularly at soil level. Tumours may also form at graft unions, especially on fruit trees. The most surprising thing about A. tumefaciens is that the tumours it induces continue to grow in a disorganised way, even when the bacterium has died out in the cells or has been eliminated experimentally by raising the temperature or exposing it to antibiotics. Similarly, pieces of bacterium-free tumour are capable of inducing a new tumour if grafted onto a healthy host. The bacterium, in producing a tumour, has transformed otherwise healthy tissue into tumorous tissue which then remains tumorous, irrespective of the presence or absence of the infecting bacterium.

FIG. 12.3

A crown gall tumour induced by artificial inoculation of a sunflower plant with Agrobacterium tumefaciens. (Dennis Butcher.)

FIG. 12.4

A tumour, probably induced by Agrobacterium tumefaciens, on a stem of Corylus sp. from Thetford Forest, Norfolk, England. (B. Golding.)

At first this seemed to be beyond all reasonable biological explanation, but in the 1970s the presence of a plasmid was discovered in Agrobacterium and found to be passed to the potential tumour cells of the host. Agrobacterium cells without the plasmid were non-pathogenic, but could receive the plasmid from a plasmid-carrying pathogenic strain of the bacterium to become pathogenic themselves. But more was to come. The pathogenic bacteria (but not non-pathogenic forms) were found to induce the production in the attacked host tissue of opines (carboxy ethyl and dicarboxy propyl derivatives of amino acids such as arginine, lysine and histine) and to utilise these opines as a source of carbohydrate and nitrogen. Moreover, strains that induced and utilised octopine, for example, did not induce or utilise another opine such as nopaline and vice versa. So here we have a pathogen inducing the production of its preferred substrate in the host, thus favouring its pathogenicity.

The story became even more interesting when it was discovered that the tumour-inducing plasmid (or part of it), following transfer to the host cells, became closely associated with the DNA of the nucleus. There it coded for the production of messenger RNA which affected the metabolism of the cell, causing it to produce excessive quantities of hormones and to become tumorous. Opine production was induced in the same way. This is a truly remarkable three way plant-pathogen relationship of bacterium, plasmid and plant. The only other well-documented example we know of involves the related bacterial species Agrobacterium rhizogenes, which induces root proliferation in its hosts, leading to the so-called ‘hairy root’ disease.

Finally, the tumour-inducing properties of A. tumefaciens and its plasmid have been harnessed by the genetic engineer to carry genes from the nucleus of one plant to the nucleus of another in order to introduce new characteristics into a crop or ornamental plant in a breeding programme. In commercial genetic engineering new ways have now been found to replace the living bacteria with microprojectiles, but there is no doubt that work on A. tumefaciens laid the foundation for modern biotechnology.

Other bacteria such as Corynebacterium facians cause distortion of host tissues and the formation of ‘fasciations’ – flattened, fused masses of stems in plants as diverse as aster, wallflower, sweet pea and forsythia (Forsythia spp.) – but the cells are not transformed as they are with Agrobacterium.

THE PARASITIC FLOWERING PLANTS

Having looked at the viruses, the smallest plant pathogens, and the bacteria and their allies, the smallest ‘cellular’ pathogens, we now turn to the largest pathogens of all, the flowering plants (although the estimates for the great size and age of the fungus Armillaria mellea – see here – might be at odds with that statement). It is estimated that about 1%, or about 3,000 species, of the known flowering plants have evolved a parasitic lifestyle, far more than the casual observer might suspect.

Parasitic plants attack in one of two ways. Firstly they may invade the roots of their host, a mode of parasitism adopted by more than half the known parasitic species. Such plants may have a complete above-ground structure which is green and superficially indistinguishable from that of their non-parasitic neighbours. Some of these are in fact facultative parasites (Fig. 12.5) and may live without attachment to a host plant for some weeks or months (e.g. eyebright (Euphrasia officinalis) and yellow rattle (Rhinanthus minor). Others may invade the host at an early stage and disappear from superficial view until the flowering shoot, without chlorophyll, emerges to flower and set seed (e.g. the broomrapes (Orobanche spp.) and toothworts (Lathraea clandestina and L. squamaria), and the tropical Rafflesia spp.) (Fig. 12.6).

Alternatively parasitic plants may invade the stems of their host, competing for space with the branches of the host and deriving nutrients from the vascular system which they tap. These forms (e.g. the mistletoes (Loranthaceae) (Fig. 12.7)) are often much branched and green, although the balance of the pho-tosynthetic pigments may be different from normal, and the stems may become filament-like and pale in colour, as in the dodders (Cuscutaceae) (Fig. 12.8), with a major reduction in the chlorophyll pigments.

FIG. 12.5

Yellow rattle (Rhinanthus minor), a facultative parasitic flowering plant. (Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.)

FIG. 12.6

A single flower (approximately 60 cm diameter) of Rafflesia pricei in Mount Kinabalu National Park, Sabah, Malaysia. (Colin Pendry, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.)

FIG. 12.7

Mistletoe(Viscum album) growing far to the north of its normal range, on hawthorn (Crataegus sp.) at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. (Debbie White, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.)

FIG. 12.8

Dodder (Cuscuta sp.) parasitising plants in the Rio de Janeiro Botanic Garden, Brazil. (D.S. Ingram.)

The species with chlorophyll are referred to as hemiparasites and, if they have a free-living phase, as facultative hemiparasites. Those without chlorophyll, which make up some 20% of all known parasitic plants, are known as holoparasites. Most of these are obligate holoparasites since they are totally dependent on the host for a supply of carbohydrates.

Many of the parasitic flowering plants are notable features of particular ecosystems while others are troublesome as parasitic weeds. In temperate regions the hemiparasitic members of the figwort family (Scrophulariaceae), for example, are important constituents of natural, mature grassland communities, but also occur as cornfield weeds. In Britain rattles (Rhinanthus spp.) have a damaging effect, reducing the number of species in a community over time. In the warmer parts of the USA and South Africa their obligately parasitic relatives are found in communities inhabiting open sunny sites or areas kept open by periodic fires.

Members of the sandalwood and dwarf mistletoe family (Santalaceae), which inhabit similar ecological niches in nature, are now mainly recognised as troublesome parasitic weeds of cultivated plants. An exception is bastard toadflax (Thesium humifusum), which is found in chalk pastures in Britain and also in grassland in Europe and Russia. The dwarf mistletoes (Striga spp.) commonly grow on the roots of various legumes and grasses, attacking particularly cereals in semi-arid regions with poor soil. They also occur in agricultural systems in moist savannah areas of Africa and extend into Asia, Australia and the USA, where the accidental introduction of one species, Striga asiatica, led to a serious infestation of parts of North and South Carolina. According to current estimates over 40% of arable land in sub-Saharan Africa is infested with S. hermantica, the main cereal root parasite, and well over 60% of the 73 million hectares in cereal production in savannah regions worldwide is contaminated with this or other Striga spp. Since the sorghums and millets of these dry regions are the main staples of the people who live there and are hosts to the Striga spp., the economic importance of parasitic plants is obvious.

The broomrapes (Orobanchaceae), relatives of the Scrophulariaceae, are particularly damaging on the Leguminoseae (hence broomrape) and Solanaceae. They can be found in Britain and mainland Europe attacking Galium spp. (bedstraws), Achillea spp. (yarrow etc.) and other wild hosts. The destructive pathogen Orobanche crenata is confined to the Mediterranean seaboard, but other species have spread north and south from there, and also eastwards to India and China. They have also been introduced into the USA, South America and South Africa.

The most striking of all the root holoparasites, although seen by few naturalists, are members of the Rafflesiaceae. Rafflesia arnoldii was first discovered in Sumatra in 1818, when a male flower was observed and measured at nearly 1 m in diameter. A female flower nearly as big was found a few years later and given the name R. titan, although how one names a species which is only found occasionally and which has flowers difficult to preserve is far from clear. These flowers are said to weigh about 5 kg. No specimens which can be referred to either of these two species have been found again. Most modern sightings are of R. tuan-mudae, which is still spectacular but has smaller flowers. The plants, which are strictly limited in their hosts to members of the vine family (Vitaceae) of the genus Tetrastigma, live within the roots of their host. The only visible evidence of their existence is the appearance of the flower at ground level, where it forms a flat basin surrounded by four to six petaloid sepals and with a central column bearing either anthers or a stigmatic disk and surrounded by a diaphragm. The heavy stench, similar to rotting meat, attracts pollinating insects. The ovary lies below the petaloid flower parts and ripens to become a berry containing many small seeds which are disseminated by fruit-eating animals. The cycle from seed to seed appears to be about five years and the flower remains visible for about five days. It is not surprising therefore that there are gaps in our knowledge of these plants.

The stem parasites are epitomised by the mistletoes (Loranthaceae). Viscum album has a long folk history in Europe, where it has been a significant element in winter solstice celebrations, in druidical ceremonies and more recently in Christmas decorations. It is temperature-sensitive, being most common in the south of Britain and virtually absent from the north (but see Fig. 12.7). In the USA the role of Viscum at Christmas is taken by mistletoes of the native Phoradendron spp. There too the endemic dwarf mistletoe Arceuthobium spp. is a major pathogen of native conifers. In the tropics mistletoes of the genus Loranthus are conspicuous in the crowns of forest trees and can be economically important pathogens of fruit and beverage crops.

On the whole, because of their size and life span, the flowering plant parasites are not easy experimental material and our knowledge of them is fragmentary, but occasionally revealing. One of the best researched genera is Striga, the obligate parasite described above. The seeds of this plant germinate only in response to root exudates of its preferred host, an obvious device to prevent fruitless germination. Thus S. hermantica seeds from millet parasites respond to millet root exudate, while those from sorghum do not, and vice versa. While there is a series of conditioning factors that affect germination, the overriding stimulus seems to come from specific compounds in the root exudate. These have been difficult to characterise because of their instability (the stimulating effect of an extract disappears at room temperature after about 2 hours) but there is now good evidence that a complex hydroquinone is the stimulant present in the root exudate of sorghum.

In facultative root parasites the seeds can apparently germinate without the presence of a root stimulus and can live autotrophically (without dependence on the host) for some time. Not so Striga spp.; they produce tiny seeds about 100 μm in diameter which need to make contact with the host root at an early stage. Clearly, in a relationship depending on a highly labile root stimulant and a small seed without reserves, the position of the seed in relation to the root is critical for infection to take place. Indeed there is a considerable amount of experimental evidence on this point and on the mechanism of induction by the hydroquinone in S. hermantica, together with the production also of a material by the Striga root which is thought to act as a stabiliser of the stimulatory material.

Once seed germination in flowering plant parasites has taken place, either close to the root or on the shoot surface, multicellular haustoria are produced to link the parasite to the host’s root or shoot. There is an underlying theme to all such structures, whether on root or shoot, but because of their economic importance most is probably known about Striga spp.. In this genus the first response as the emerging root of the parasite approaches the host root is enlargement of the cortex of the parasitic root, generating a lateral or terminal protuberance. This is followed by the division of the cells surrounding the vascular tissue and the production of epidermal hairs, which appear to become attached to the surface of the host root, as does the surface of the swollen end of the parasite root. From this surface a peg-like protuberance grows forward and penetrates the host tissue, where it is called the ‘endophyte’. The mature haustorium that develops from the enlarging penetration peg forms a vascular extension which grows towards the vascular system of the host. The area in-between, known as the hyaline body, contains only a few strands of rather simply differentiated xylem and no clearly differentiated phloem. There is thus a complete, though sparse, connection between the xylem tissue of host and parasite but no clearly visible phloem connections. This is intriguing and suggests that the hyaline body, in spite of its simple appearance, may substitute for phloem and have complex functions in the storage and transport of carbohydrates and other substances from host to parasite in a manner yet to be understood.

Once germination has been induced there is ample evidence that attachment to the plant is a physical response to a surface, and a great variety of inert substances are capable of bringing about attachment with more or less equal facility, although there is some conflicting evidence that epidermal secretions may be involved. In Striga spp. attachment occurs within 24 hours of the seed receiving the chemical signal for germination; and growth and penetration to link with the host’s vascular system follow in another 24 hours. Where parasite and host are incompatible the host rapidly develops responses such as localised cell necrosis (hypersensitivity), production of corky layers, callose deposition and lignification of the cell walls, very much as in response to incompatible fungi and bacteria (see here).

And so we come to the end of our exploration of the world of plant parasitism. We have seen that this is a niche occupied by viruses, bacteria, fungi and higher plants themselves, and that there is a remarkable degree of parallelism in the strategies that have evolved. The relationships range from necrotrophy through hemibiotrophy and biotrophy to mutualism. Sometimes the pathogen or parasite has evolved an obligate relationship with its host and in others it has retained the flexibility to adopt an independent existence. It would be wrong, however, to think of any one of these relationships or strategies as being more successful, more advanced or more specialised than another; each enables the parasite or pathogen to invade and succeed in one of a range of potential niches not available to its competitors. In the case of mutualistic relationships, which we have touched on only occasionally, the ecological range of both partners is extended by their shared existence.

We find plant diseases fascinating subjects for study at every level, whether it be their natural history, their taxonomy, the complexities of the structural and biochemical relationships between host and pathogen, their importance in agriculture, their control or their effects on history. And again, it would be wrong to think of any one of these approaches as more sophisticated or more important than another; to a scholar all knowledge is important in achieving a measure of understanding of the world we inhabit. We hope that in writing this book we may have communicated some of our all embracing interest and enthusiasm for pathogens to fellow natural historians.

We end with a final plea: enjoy your pathogens and don’t let them intimidate you (see Appendix).

POSTSCRIPT

Those who study plant diseases must ‘get their eye in’. It is easy to walk past vegetation without seeing the infected plants. One day, however, the difference between infected and healthy individuals will leap to the eye, and once recognised will never be forgotten. While this revelation can take place anywhere to reward the careful observer, it happens particularly and effortlessly, in our experience, at picnics or lunch breaks in the countryside, especially if wine or beer rather than tea provides the liquid refreshment. Not when lying flat looking up at the sky, but when replete and resting with the back against a rock or tree; at that time the eye roves in a relaxed way over the nearby vegetation and soon distinguishes anything strange. Perhaps the most spectacular picnic find of our experience was the discovery of Schizonella melanogramma by a student during a lunch break in the Cairngorm mountains in Scotland. This is an unusual smut with its spores in attached pairs, occurring on the leaves of a sedge, and until that time it had not been recognised in Britain. If you are not so lucky, don’t worry; admire the view and try again another day.