28

What can a corpus tell us about vocabulary teaching materials?

Martha Jones and Philip Durrant

1. What vocabulary is important for my learner?

Language teachers have long used lists of important vocabulary as a guide to course design and materials preparation, and corpus data have always played a major part in developing these lists. As early as the 1890s, Kaeding supervised a manual frequency count of an eleven-million-word corpus to identify important words for the training of stenographers, and similar counts were used by language teachers from at least the early twentieth century onwards (Howatt and Widdowson 2004: 288–92). The argument for prioritising vocabulary learning on the basis of frequency information is based on the principle that the more frequent a word is, the more important it is to learn. Proponents of a frequency-based approach point to the fact that a relatively small number of very common items accounts for the large majority of language we typically encounter. Nation (2001: 11), for example, reports that the 2,000-word families of West’s (1953) General Service List account for around 80 per cent of naturally occurring text in general English. This suggests that a focus on high-frequency items will pay substantial dividends for novice learners since knowing these words will enable them understand much of what they encounter (Nation and Waring 1997: 9).

The development of computerised corpus analysis has made the job of compiling word-frequency statistics far easier than it once was, and has given impetus to a new wave of pedagogically oriented research (e.g. Nation and Waring 1997; Biber et al. 1999; Coxhead 2000). Importantly, the widespread availability of corpora and the ease of carrying out automated word counts seems also to offer individual teachers the possibility of creating vocabulary lists tailored to their learners’ own needs. However, it is important to bear in mind that corpus software is not yet able to construct pedagogically useful word lists without substantial human guidance. Teachers wishing to create such lists will need to make a number of important methodological decisions, and to make these decisions well will need to understand the issues surrounding them.

The first set of decisions that need to be made concerns the choice or construction of a suitable corpus. With the large number of corpora available today, and the relative ease of constructing a corpus tailor-made for a given project, it should be possible to ensure a good match between the corpus and the target language. However, it remains essential that this be based on careful needs analysis. Section 3 of the present chapter describes the issues involved in corpus design in more detail.

A second, and less well-researched, decision is that of defining what sorts of items are to be counted as ‘words’ (Gardner 2008). The teacher will need to decide, for example, whether morphologically related forms (e.g. run and running) should be listed as two separate words or treated as a single item; in other words, whether they should be ‘lemmatised’. Similar decisions must be made for the different senses of polysemous words (e.g. run (a race) and run (a company)). A list which conflates a range of forms, meanings and phrases under the heading of a single abstract ‘word’ will achieve excellent economy of description. However, such economy can be bought only with the loss of potentially important information. Clearly, some forms, senses and collocations of a highfrequency headword like run are more important to learn than others, and many are probably less important than lower-frequency words. Unless separate frequency counts are given, however, a list will give no grounds for prioritising such learning.

Some researchers have justified the use of abstract word groups on the grounds that once one form of a word is learned, learning the related forms requires little extra effort (Nation 2001: 8), and that abstract semantic representations can be given to cover a range of polysemous senses (Schmitt 2000: 147–8). However, others have noted that the learning of morphologically related items may not be as automatic as has sometimes been thought (Gardner 2008: 249–50; Schmitt and Zimmerman 2002), and it is not clear that abstract meaning representations will give learners the information they need to use words effectively. It also seems likely that learners will need to have multi-word expressions brought explicitly to their attention (Coxhead 2008; see also chapters by Greaves and Warren and Coxhead, this volume).

Any decision on this issue must, in the ultimate analysis, depend on what the list will be used for. If a list is intended primarily as an inventory of important vocabulary for comprehension, for example, then many distinctions between forms and senses may be considered less important, since related forms and meanings may be deducible by learners in context. However, if the intention is to specify items over which learners should have accurate active control, a more fine-grained approach may be needed. Another important factor is the time allowed for carrying out the research: automated corpus analysis tools are not yet able adequately to distinguish between different senses of words, and the accuracy of the quantitative means of identifying collocations on which automatic processing depends remains open to debate (see the next section). Extensive manual analysis would be required in order to provide a listing which takes such variations into account.

A further consideration that needs to be borne in mind by word-list compilers is that frequency is not the only factor which might make a word worthy of attention. In compiling the well-known General Service List, West and his colleagues considered a number of criteria other than frequency: less frequent words were included if they could be used to convey a range of important concepts; words were excluded if a synonym was available; words needed to be stylistically neutral; and ‘intensive emotional’ words (i.e. items ‘whose only function is to be the equivalent of underlining, or an exclamation mark’) were not included (West 1953: ix–x). Other factors which have been suggested as criteria include the likely difficulty of a word for the learners in question (Ghadessy 1979) and the subjective ‘familiarity’ and psychological ‘availability’ of words (i.e. how readily they come to a native speaker’s mind), factors which are suggested to identify words which carry important semantic content (Richards 1974). Teachers may also need to consider which words belong together as natural ‘sets’.O’Keeffe et al. (2007: 40), for example, point out that there are wide differences in the frequencies of the names of different days of the week, with Friday, Saturday and Sunday being the most common, and Tuesday and Wednesday far less frequent. As these authors remark, however, there are few who would propound teaching only the most frequent of these names as basic vocabulary and leaving the others for later. In short, a careful consideration of a range of factors other than frequency is likely to improve the value of any pedagogical list.

2. Vocabulary materials and formulaic language

One of the central insights to come from corpus linguistics in the last thirty years is the extent to which competent language users draw not only on a lexicon of individual words, but also on a range of lexicalised phrasal units which have come to be known as ‘formulaic sequences’ (Wray 2002; Schmitt 2004). Exactly what should count as a formulaic sequence remains disputed, but a list might include:

• collocations and colligations: hard luck, tectonic plates, black coffee, by the way;

• pragmatically specialised expressions: Happy Birthday, Pleased to meet you, Come in;

• idioms: the last straw, fall on your sword, part and parcel;

• lexicalised sentence stems: what’s X doing Y (as in what’s this fly doing in my soup), X

BE sorry to keep TENSE you waiting (as in Mr Jones is sorry to have kept you waiting). What these items have in common is that they appear to be, in Wray’s words, ‘prefabricated: that is, stored and retrieved whole from memory at the time of use, rather than being subject to generation or analysis by the language grammar’ (Wray 2002: 9).

Defined in this way, such sequences are arguably part of the vocabulary of the language which learners need to acquire, and a number of writers have emphasised the importance for learners of getting to grips with items of this sort (e.g. O’Keeffe et al. 2007: Ch. 3; Coxhead 2008). Constructing utterances from formulae, rather than stringing together individual words according to the rules of grammar, is held both to be cognitively efficient (Ellis 2003) and to give the speaker a better chance of hitting on the natural, idiomatic way of expressing themselves (Kjellmer 1990; Hoey 2005). For these reasons, a good knowledge of formulae is generally thought to be important for achieving both fluency (Pawley and Syder 1983; Raupach 1984; Towell et al. 1996; Kuiper 2004; Wood 2006) and nativelike production (Pawley and Syder 1983; Kjellmer 1990). More controversially, some researchers have claimed that the acquisition of grammar is based on a process of abstracting away from an inventory of initially rote-learned formulas (Nattinger and DeCarrico 1992: 114–16; Lewis 1993: 95–8), though this idea is hotly disputed (Wray 2000).

If we accept that formulae are an important aspect of vocabulary learning, then our vocabulary materials need to be adapted or extended to include them. However, this raises two difficult problems. First, we need to determine which word strings are formulaic. Second, we need to decide which of the many formulae known to native speakers learners most need to learn.

Wray (2002: Ch. 2) describes four prominent methods for identifying formulae: intuition (formulae are those sequences which the analyst, or their informant(s), recognises as formulaic); frequency (formulae are those sequences which occur with a certain frequency in a corpus); structure (formulae are those sequences which are anomalous in that they do not follow the usual rules of the language); and phonology (formulae are sequences which are phonologically coherent). All of these identification criteria are problematic, however, because all of them are indirect. The definition of formulae as items which are retrieved from memory depends, as Wray notes, on an ‘internal and notional characteristic’–retrieval from memory – which is not directly observable (2002: 19). Each approach therefore can only give us clues about, rather than confirmation of, formulaicity.

Within corpus linguistics, the primary identification criterion has been frequency of occurrence. The logic of this approach is two-fold: on the one hand, common phrases are held to be common as a result of their being stored in language users’ mental inventories and so frequently retrieved from memory in preference over less conventional expressions; on the other hand, phrases which are common in the language a speaker hears are more likely to become ‘entrenched’ in their lexicon. The frequency approach has the advantage over other methods of relative objectivity, and of allowing large amounts of text to be easily processed; it also bypasses the possible problems of subjectivity and inconsistency to which human analysts may be prone (Wray 2002: 25). However, it also has a number of important shortcomings.

First, there is the problem of corpus representativeness and variation between speakers: all speakers have a different history of exposure to the language, and a corpus cannot give a perfect reflection of any of them. The fact that a particular phrase is common in a particular corpus does not, therefore, guarantee that it will have been common in the experience of any particular speaker. This problem is compounded by the fact that formulae are often closely associated with particular contexts. Second, the relationship between frequency and formulaicity cannot be a straightforward one because it is known that many archetypally formulaic expressions (especially, for example, idioms) are relatively infrequent, while many word sequences which we would not want to call formulae (especially combinations of high-frequency words which come about by chance or grammatical concord, e.g. and in the) can be very frequent (see Greaves and Warren, this volume, who look at this kind of sequence in the context of multi-word units). Relatedly, many writers have questioned the basic assumption that frequent word sequences are frequent because they are stored in the mind. Corpus linguists need to be wary here of the fallacy of ‘introjection’ (Lamb 2000) – the naive ascription of all patterns of language directly to real features of the human mind. It may be that a sequence is frequent because of some psychological factor, but it is also possible that it is frequent simply because of ‘the nature of the world around us’: ‘[t]hings which appear physically together’, ‘concepts in the same philosophical area’, and ‘organising features such as contrasts or series’ (Sinclair 1987: 320).

Furthermore, the job of the vocabulary materials developer does not end once formulae have been identified. They also need to determine which of the ‘hundreds of thousands’ of such items estimated to exist in the average native lexicon (Pawley and Syder 1983: 210) learners most need to know. An obvious corpus-based solution would again be to select the most frequent formulae. This would be a natural extension of a frequency-based approach to identification. However, it would also be open to the pedagogical objections discussed in the previous section against using frequency to determine the contents of word lists.

It will be clear to the reader that methods in this important area are still very much in their infancy, and developments are ongoing. To date, perhaps the most sophisticated attempt to come to terms with the problem of estimating formulaicity (i.e. mental storage) from frequency, and of matching both with pedagogical usefulness, has been that of Ellis et al. (2008), who combined frequency-based and psycholinguistic methods with a survey of teacher intuitions to construct a listing of useful phrases for students of English for Academic Purposes. If we are to produce principled listings of conventional formulae, much more work along these lines will be needed.

3. What type of corpus is suitable for academic vocabulary learning?

As mentioned in Section 1, a corpus should include the target language students will be exposed to as part of their studies. A number of corpora focusing on English for Academic Purposes have recently been developed in an attempt to meet the needs of international students studying in higher education. For an overview of recently compiled EAP corpora, see chapters by Coxhead and Lee, this volume and Krishnamurthy and Kosem (2007).

Academic written English has long been the focus of corpora compilers and researchers, as EAP students need to learn the appropriate language to read academic texts efficiently and write clearly, accurately and appropriately according to conventions established by the members of academic communities in specific disciplines. The British Academic Written English Corpus (BAWE) (Nesi et al. 2005), which has recently been made available to researchers, consists of 6.5 million words of proficient student writing covering four levels of study on undergraduate and taught postgraduate programmes and four broad disciplinary areas (arts and humanities, social sciences, life sciences and physical sciences). This corpus will undoubtedly prove to be valuable to researchers but it is not clear whether EAP practitioners who wish to use some of the data for the development of teaching materials will be able to have access to this material. Another example of an EAP corpus of academic written English which will be made available is the Michigan Corpus of Upper-Level Student Papers (MICUSP). Other smaller EAP corpora, some of which include PhD theses, have been compiled by individuals, but the data are not always readily available.

The Academic Word List (AWL) (Coxhead 2000; Coxhead and Byrd 2007), based on a corpus consisting of approximately 3.5 million words and covering a wide range of academic texts from a variety of subject areas in four faculty areas (arts, commerce, law and science) is now widely used by researchers, materials writers (e.g. McCarthy and O’Dell 2008), EAP practitioners and students. It is considered to be a good example of language-in-use focused on academic writing and the main aim of its compilation was to provide words deemed to be core academic vocabulary worth learning. However, this view is challenged by Hyland and Tse (2007), who found that occurrence and behaviour of individual lexical items varied across disciplines in terms of range, frequency, collocation and meaning, which led to the conclusion that the AWL is not as general as it is claimed to be.

As mentioned in Section 1, careful needs analysis is at the centre of the construction of a corpus which represents the target language. McEnery and Wilson (1996) note that sampling and representativeness are crucial in the compilation of a corpus which is representative of the type of language to be examined, as tendencies of that variety of language together with their proportions can be illustrated accurately. It is important to define a sampling frame: that is, the entire population of texts from which samples can be taken. Nesi et al. (2005: 2) provide information on possible sampling methods such as random sampling (every subset of the same size has an equal chance of being selected), stratified sampling (population first divided into strata and then random sampling used), cluster sampling (population divided into subgroups and only some of those subgroups are chosen), quota sampling (population is cross-classified along various dimensions deemed important and quotas are established for each of the subgroups), opportunistic sampling (taking whatever members of the population are easy to get hold of) and purposive sampling (an expert in a relevant field chooses cases on the basis of a judgement as to how well they exemplify a particular population).

Corpus size is another important aspect of corpus compilation to consider. While a small corpus (e.g. a corpus of less than a million words) may be sufficient to portray grammatical features for learners to explore, a larger corpus (e.g. one of tens of millions of words) is needed in order to generate frequency lists of words and phrases considered to be representative of the type of language under examination, especially when it comes to ‘occurrences of salient but infrequent items so that relevant patterns of use can be observed’ (O’Keeffe et al. 2007: 55).

In Section 5 we describe the compilation of a corpus of science and engineering research articles, discuss issues related to approaches used for designing vocabulary teaching materials, and provide samples of teaching materials based on this corpus.

4. What vocabulary input do my teaching materials provide?

A number of studies based on comparisons of linguistic features portrayed in academic writing textbooks and corpus-based research into language actually used in expert and student writing have identified a lack of fit between the two. Harwood (2005: 150), for example, notes that ‘textbooks are found to understate the enormous disciplinary variation in style and language which corpora reveal’ and goes on to add that ‘a lack of specificity can mislead and distort’ (ibid.: 155).

Another example of the discrepancy between recommendations given in textbooks as regards language use and evidence from corpus-based research of real language usage is the study conducted by Paltridge (2002). He compared the advice on organisation and structure of theses and dissertations and the structure of master’s and doctoral theses, as evidenced in a corpus. He found that while published handbooks did cover some aspects of the research process, they did not provide information on the content of individual chapters or the range of thesis types that his corpus study revealed.

In Section 1 we suggested that in order to produce pedagogically useful word lists, considerable human guidance is necessary. Ideally, the selection of raw data on which to base teaching materials should be conducted by an EAP teacher with experience in the analysis and exploitation of language corpora although perhaps only a few EAP teachers may have been trained to do so. Evidence of how materials developers give serious consideration to theoretical and pedagogical aspects of materials design and development, whether the materials are produced for local, international, commercial or non-commercial consumption can be found in Harwood (forthcoming).

In the absence of corpus data on which to base materials development or an appropriate textbook, a number of teachers resort to the creation of in-house materials which will involve the adaptation of authentic texts or texts found in textbooks. As Samuda (2005: 235) notes, ‘teachers engage in re-design, tweaking, adjusting and adapting materials to suit particular needs’. A number of in-house materials are produced in EAP units for the teaching of academic reading and writing. These materials are often piloted, revised, updated and improved. There is evidence that shows that evaluation methods which involve feedback from different parties are important if materials are to meet the specific needs of students (Stoller et al. 2006). Table 28.1 shows a list of keywords – i.e. words whose frequency is unusually high in comparison with some norm (Scott 1999) – generated by WordSmith Tools 5.0 (Scott 2008). It is based on a comparison of a small corpus of sample in-house EAP materials used for the teaching of academic reading and writing and a reference corpus consisting of the non-academic parts of the British National Corpus. The purpose of this comparison was to ascertain to what extent academic vocabulary and discipline-specific vocabulary is included in this sample of in-house materials.

After a search in the Academic Word List (Coxhead 2000), it was found that only academic and project from the list in Table 28.1 were academic words. However, further down the frequency keyword list, we have others such as sources, section, sections and research, in sublist 1; conclusion, in sublist 2; task and technology, in sublist 3, and topic and extract, in sublist 7, to name a few. As regards discipline-specific vocabulary, only a few words, such as genetic, obesity, collocations and thermal could be considered to be more specialised.

This comparison can lead us to conclude that in-house EAP materials may be suitable for the teaching of academic vocabulary but if the aim is to learn discipline-specific words or phrases, perhaps materials based on a specialised corpus would be required.

5. What approaches should be used for designing teaching materials?

While more and more EAP units are developing in-house materials for the teaching of academic writing, these do not often focus on disciplinary variation. This section describes a corpus of science and engineering journal articles, compiled by the authors, and possible corpus-based approaches to the teaching of vocabulary and formulaic sequences by using word lists and concordance lines as well as awareness-raising tasks based on this corpus.

Academic journal articles which PhD students are likely to draw upon as part of their research can be a useful resource for the teaching of academic vocabulary, and the data are often freely available in electronic form in university libraries. A corpus aimed at firstyear PhD science and engineering students at the University of Nottingham was compiled with a view to creating word lists and concordances on which to base vocabulary teaching materials. The corpus consists of 11,624,741 words (accessed on-line) and covers a wide range of disciplines in the faculties of science and engineering. Table 28.2 includes a sample list of keywords generated by using WordSmith Tools 5.0 (Scott 2008) and based on the comparison of the science and engineering corpus and the same reference corpus described in Section 4. The words on this list were found to be key in all disciplines in our science and engineering corpus.

As mentioned in Section 1, frequency is only one of the criteria used for the selection of particular lexical items to be taught. Other important factors to consider are range of

word meanings, familiarity, availability and level of difficulty. The list of keywords was subsequently examined by one of the present authors in order to select a list of fifty words using her intuition regarding what words would be likely to be useful for thesis writing. Table 28.3 shows this list.

Once a list of keywords has been selected, the next stage in materials development involves the production of concordance lines for students to examine as well as awarenessraising tasks which include clear instructions as to how the data should be analysed and questions which will guide the students’ exploratory data analysis. Advocates of datadriven learning (DDL) or inductive approaches to the learning of grammar and vocabulary have made use of concordance texts to develop teaching materials which facilitate the learner’s discovery of patterns based on evidence from authentic texts and foster a sense of autonomy, as the learner does not depend on the teacher to work out rules of usage (Tribble 1990; Tribble and Jones 1990; Johns 1991a, 1991b).

More recent studies have described the use of concordances to develop EAP/ESP teaching materials. Thurstun and Candlin (1998) used concordances in combination with a variety of problem-solving activities for independent study of academic vocabulary. They claim that this type of material provides exposure to multiple examples of the same vocabulary item in context and raises awareness of collocational relationships. Nation (2001) also stresses the importance of multiple encounters with new words in order for students to be able to use these words in writing. Despite criticisms of the use of corpusbased material in the classroom (Cook 1998; Widdowson 2000), several studies conducted on the teaching of academic writing comment on the value of concordances as a first step to uncover linguistic features which would otherwise be difficult to identify (Hyland 1998, 2003; Thompson and Tribble 2001; Hoon and Hirvela 2004).

In the light of the usefulness of concordances discussed so far, we now need to examine the list of 50 keywords shown in Table 28.3. This list was scrutinised in greater detail with the aim of extracting a few words to be included in concordances for our PhD students to examine guided by awareness-raising tasks. The words selected were: average, behaviour, consequently, higher, positive, presented, response, shown and study.

These nine words could not be considered to be discipline-specific, which may not seem coherent with the arguments for the compilation of discipline-specific lists of academic vocabulary included in Section 3. However, this selection was pedagogically driven on the basis of the following criteria:

a. Frequency (frequently used words in corpus data across disciplines).

b. Words which were frequent both in corpus data across disciplines and in a sample text our PhD students had previously been asked to read to identify academic vocabulary.

c. Words frequently used

either: in all three of the following sources: corpus data across disciplines; the sample text given to students to read; and in the Academic Word List (Coxhead 2000);

or: in two of these.

The students had no previous experience using concordances, so it was hoped that the choice of familiar words would make the first encounter with this type of learning material less alien or threatening.

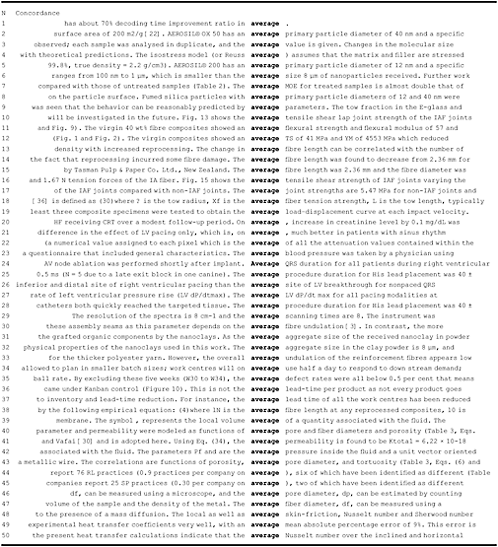

Figure 28.1 includes sample concordances of average which are accompanied by a sample awareness-raising task given to students.

Sample task based on concordances of average

The following questions will help you notice patterns either in the left or right context, i.e. to the left or the right of the Key Word in Context (KWIC). Spend some time analysing the concordances of this word and answer the following questions:

1. The word ‘average’ can be used as a noun or as an adjective. Look at the right context. Which seems to be more frequently used in this body of data?

2. Look at the right context. Find examples of the following uses:

a. result obtained when adding two or more numbers together and dividing the total by the no. of numbers that were added together;

b. a number or size that varies but is approximately the same;

c. typical or normal person or thing;

d. normal amount or quality for a particular group of things or people;

e. neither very good nor very bad.

3. Look at the left context. When used as a noun, ‘average’ is preceded by an article, either definite ‘the’ or indefinite ‘a/an’. Which article is more common in this set of data?

4. Look at the left context. Sometimes ‘average’ is part of a prepositional phrase. Which prepositional phrases can you find in the concordances?

5. In what section(s) of a journal article do you think you are more likely to find the word ‘average’?

If students are able to handle tasks such as this one successfully, future tasks can be made progressively more challenging by asking students to identify formulaic sequences used in their disciplines.

A number of recent studies on academic writing have revealed considerable use of phraseology in discipline-specific texts. In his corpus-based study of engineering textbooks, Ward (2007) notes that there is a strong link between collocation and technicality. His analysis focused on collocations including discipline-specific nouns. He claims that what students need to know about items on a frequency list is their collocational behaviour and that centrality of collocation to specialisation is better shown in data from words common in more than one sub-discipline. Two possible approaches to the

Figure 28.1 Concordances of average from a corpus of scientific and engineering research articles.

teaching of collocation are recommended in his study. The first is raising students’ awareness of the existence and frequency of collocations and the second is teaching the process of reading collocations as chunks.

Gledhill (2000) investigated phraseology found in introductions from a corpus of cancer research articles and argues for the design of a specialised corpus of the research article and a computer corpus-based methodology to describe the phraseology of the research article genre. His study centred specifically on collocations of grammatical words and their role in terms of textual function and recommends a combined approach to genre and corpus analysis. Corpus analysis can reveal recurrent patterns while the genre approach provides the opportunity to observe the series of choices in different sections of the academic research article. Gledhill’s study (ibid.: 130) revealed that in some instances collocation involved terminology, thus reflecting the recurrent semantics of the specialist domain, and in other instances collocation revealed the dominant discourse strategies in the research article. At the end of the study, Gledhill concludes that phraseology is part of the defining characteristics of the discourse community.

Other discipline-specific studies have focused on the use of lexical bundles or semantic associations. Cortes (2004) compared the use of lexical bundles in published and student disciplinary writing using a corpus of history and biology research articles and students’ papers in the undergraduate lower and upper divisions and graduate level at Northern Arizona University. The study suggests that explicit teaching of lexical bundles is necessary in order to enable students to notice them first and then use them actively in their writing. Nelson (2006) identified the semantic associations of words by using a corpus of spoken and written Business English and demonstrated how words in the Business English environment interact with each other on a semantic level. His study shows that words have semantic prosodies which are unique to business, separate from the prosodies they generate in the general English environment.

Drawing on the literature relevant to vocabulary acquisition, corpus-based studies and the design and development of teaching materials, this chapter has described how a carefully compiled corpus of discipline-specific research articles could be exploited to design EAP vocabulary teaching materials in order to meet the needs of PhD students in their first year of their programmes. It is likely that frequent exposure to this type of material will enable students to recognise and use key vocabulary in their disciplines.

Further reading

Biber, D. (1993) ‘Representativeness in Corpus Design’, Literary and Linguistic Computing 8: 243–57. (Biber’s work is an excellent introduction to issues in corpus design and compilation.)

Harwood, N. (ed.) (forthcoming) Materials in ELT: Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Harwood’s edited book is an up-to-date collection of studies focusing on materials design and development.)

Nation, P. and Waring, R. (1997) ‘Vocabulary Size, Text Coverage and Word Lists’, in N. Schmitt and M. McCarthy (eds) Vocabulary: Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 6–19. (Nation and Waring’s work offers an excellent introduction to issues surrounding word-list compilation and use.)

Wray, A. (2002) Formulaic Language and the Lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Wray’s work has become a standard introductory text to formulaic language, including reviews of the literature on most aspects of the phenomenon.)

References

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad S. and Finegan, E. (1999) Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Harlow: Longman.

Cook, G. (1998) ‘The Uses of Reality: A Reply to Ronald Carter’, ELT Journal 52: 57–64.

Cortes, V. (2004) ‘Lexical Bundles in Published and Student Disciplinary Writing: Examples from History and Biology’, English for Specific Purposes 23: 397–423.

Coxhead, A. (2000) ‘A New Academic Wordlist’, TESOL Quarterly 34: 213–38.

——(2008) ‘Phraseology and English for Academic Purposes’, in F. Meunier and S. Granger (eds) Phraseology in Language Learning and Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 149–61.

Coxhead, A. and Byrd, P. (2007) ‘Preparing Writing Teachers to Teach the Vocabulary and Grammar of Academic Prose’, Journal of Second Language Writing 16: 129–47.

Ellis, N. C. (2003) ‘Constructions, Chunking, and Connectionism: The Emergence of Second Language Structure’, in C. J. Doughty and M. H. Long (eds) The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 63–103.

Ellis, N. C., Simpson-Vlach, R. and Maynard, C. (2008) ‘Formulaic Language in Native and Secondlanguage Speakers: Psycholinguistics, Corpus Linguistics, and TESOL’, TESOL Quarterly 41: 375–96.

Gardner, D. (2008) ‘Validating the Construct of word in Applied Corpus-based Vocabulary Research: A Critical Survey’, Applied Linguistics 28: 241–65.

Ghadessy, M. (1979) ‘Frequency Counts, Word Lists and Materials Preparation’, English Teaching Forum 17: 24–7.

Gledhill, C. (2000) ‘The Discourse Function of Collocation in Research Article Introductions’, English for Specific Purposes 19: 115–35.

Harwood, N. (2005) ‘What Do We Want EAP Teaching Materials for?’, Journal of English for Academic Purposes 4: 149–61.

——(forthcoming) (ed.) Materials in ELT: Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hoey, M. (2005) Lexical Priming: A New Theory of Words and Language. London: Routledge.

Hoon, H. and Hirvela, A. (2004) ‘ESL Attitudes Toward Corpus Use in L2 Writing’, Journal of Second Language Writing 13: 257–83.

Howatt, A. P. R. and Widdowson, H. G. (2004) A History of English Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hyland, K. (1998) Hedging in Scientific Research Articles. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

——(2003) Second Language Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hyland, K. and Tse, P. (2007) ‘Is there an “Academic Vocabulary?”’, TESOL Quarterly 41(2): 235–53.

Johns, T. (1991a) ‘Should You Be Persuaded’, ELR Journal 4: 1–16.

——(1991b) ‘From Printout to Handout’, ELR Journal 4: 27–46.

Kjellmer, G. (1990) ‘A Mint of Phrases’, in K. Aijmer and B. Altenberg (eds) English Corpus Linguistics: Studies in Honour of Jan Svartvik. London: Longman, pp. 111–27.

Krishnamurthy, R. and Kosem, I. (2007) ‘Issues in Creating a Corpus for EAP Pedagogy and Research’, Journal of English for Academic Purposes 6: 356–73.

Kuiper, K. (2004) ‘Formulaic Performance in Conventionalised Varieties of Speech’, in N. Schmitt (ed.) Formulaic Sequences: Acquisition, Processing and Use. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 37–54.

Lamb, S. (2000) ‘Bidirectional Processing in Language and Related Cognitive Systems’, in M. Barlow and S. Kemmer (eds) Usage Based Models of Language. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications, pp. 87–119.

Lewis, M. (1993) The Lexical Approach: The State of ELT and a Way Forward. London: Thomson Heinle.

McCarthy, M. J. and O’Dell, F. (2008) Academic Vocabulary in Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McEnery, T. and Wilson, A. (1996) Corpus Linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Nation, P. (2001) Learning Vocabulary in Another Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nation, P. and Waring, R. (1997) ‘Vocabulary Size, Text Coverage and Word Lists’, in N. Schmitt and M. McCarthy (eds) Vocabulary: Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 6–19.

Nattinger, J. R. and DeCarrico, J. S. (1992) Lexical Phrases and Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nelson, M. (2006) ‘Semantic Associations in Business English: A Corpus-based Analysis’, English for Specific Purposes 25: 217–34.

Nesi, H., Gardner, S., Forsyth, R., Hindle, D., Wickens, P., Ebeling, S., Leedham, M., Thompson, P. and Heuboeck, A. (2005) ‘Towards the Compilation of a Corpus of Assessed Student Writing: An Account of Work in Progress’, paper presented at Corpus Linguistics, University of Birmingham, published in the Proceedings from the Corpus Linguistics Conference Series, 1, available at www.corpus.bham.ac.uk/PCLC

O’Keeffe, A., McCarthy, M. J. and Carter, R. A. (2007) From Corpus to Classroom: Language Use and Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Paltridge, B. (2002) ‘Thesis and Dissertation Writing: An Examination of Published Advice and Actual Practice’, English for Specific Purposes 21: 125–43.

Pawley, A. and Syder, F. H. (1983) ‘Two Puzzles for Linguistic Theory: Nativelike Selection and Nativelike Fluency’, in J. C. Richards and R. W. Schmidt (eds) Language and Communication. New York: Longman, pp. 191–226.

Raupach, M. (1984) ‘Formulae in Second Language Speech Production’, in H. W. Dechert, D. Mohle and M. Raupach (eds) Second Language Productions. Tubingen: Gunter Narr, pp. 114–37.

Richards, J. C. (1974) ‘Word Lists: Problems and Prospects’, RELC Journal 5: 69–84.

Samuda, V. (2005) ‘Expertise in Pedagogic Task Design’, in K. Johnson (ed.) Expertise in Second Language Learning and Teaching. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 230–54.

Schmitt, N. (2000) Vocabulary in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——(ed.) (2004) Formulaic Sequences: Acquisition, Processing and Use. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Schmitt, N. and Zimmerman, C. B. (2002) ‘Derivative Word Forms: What Do Learners Know?’ TESOL Quarterly 36: 145–71.

Scott, M. (1999) WordSmith Tools Users Help File. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

——(2008) WordSmith Tools 5.0. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sinclair, J. M. (1987) ‘Collocation: A Progress Report’, in R. Steele and T. Threadgold (eds) Language Topics: Essays in Honour of Michael Halliday. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 319–31.

Stoller, F. L., Horn, B., Grabe, W. and Robinson, M. S. (2006) ‘Evaluative Review in Materials Development’, Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5: 174–92.

Thompson, P. and Tribble, C. (2001) ‘Looking at Citations: Using Corpora in English for Academic Purposes’, Language Learning and Technology 5: 91–105.

Thurstun, J. and Candlin, C. N. (1998) ‘Concordancing and the Teaching of the Vocabulary of Academic English’, English for Specific Purposes 17: 267–80.

Towell, R., Hawkins, R. and Bazergui, N. (1996) ‘The Development of Fluency in Advanced Learners of French’, Applied Linguistics 17: 84–119.

Tribble, C. (1990) ‘Concordancing and an EAP Writing Programme’, CAELL Journal 1(2): 10–15.

Tribble, C. and Jones, G. (1990) Concordances in the Classroom. London: Longman.

Ward, J. (2007) ‘Collocation and Technicality in EAP Engineering’, Journal of English for Academic Purposes 6: 18–35.

West, M. (1953) A General Service List of English Words. London: Longman.

Widdowson, H. (2000) ‘On the Limitations of Linguistics Applied’, Applied Linguistics 21: 3–25.

Wood, D. (2006) ‘Uses and Functions of Formulaic Sequences in Second Language Speech: An Exploration of the Foundations of Fluency’, Canadian Modern Language Review 63: 13–33.

Wray, A. (2000) ‘Formulaic Sequences in Second Language Teaching: Principle and Practice’, Applied Linguistics 21: 463–89.

——(2002) Formulaic Language and the Lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.