From neologism to a new paradigm

Anne-Sophie Fernandez, Paul Chiambaretto, Frédéric Le Roy, and Wojciech Czakon

Comfortably sitting on your sofa, you watch your favorite show on your Sony TV. Did you know that the screen is front of you was jointly developed by both Sony and Samsung, two rival firms in the consumer electronics industry (Gnyawali & Park, 2011)?

You are in Dubai on top of the tallest building in the world, the Burj Khalifa. Despite being very high in the sky, your smartphone receives a perfect signal. Did you know that the telecommunications network in the United Arab Emirates is the fruit of two competing giants of the satellite telecommunication industry, Airbus and Thales (Fernandez et al., 2014)?

You feel a bit dizzy. Since your doctor has diagnosed you with heart disease, you have to take a pill. On the package, you read Plavix. Did you know that this drug would not exist without the collaboration of two competing pharmaceutical companies, BMS and Sanofi (Bez et al., 2016)?

You are at a New York airport waiting to board your flight across the Atlantic Ocean. Did you know that when you buy a Delta Airlines ticket on an intercontinental flight, you have a more-than-fifty-percent chance of being on an Air France flight? Despite being strong competitors, Air France and Delta Airlines cooperate together to offer more flights and destinations, as well as reduced connecting times and the best possible experience during the flight (Chiambaretto & Fernandez, 2016).

You have just arrived at your hotel for a well-deserved holiday break. You decided to enjoy your holidays in Poland because you saw an advertisement in the subway back home. Did you know that competing hotels and theme parks in this region have decided to join forces to promote their region and make sure you visit, all while remaining in competition (Czakon & Czernek, 2016)?

These examples show that in many industries, competing firms rely heavily on collaboration with their direct rivals to better and faster achieve their objectives, to provide their customers with the utmost satisfaction, and to reach higher performance levels. To grasp this paradoxical combination of simultaneous cooperation and competition, several decades ago a specific term was coined: “coopetition.” The neologism “coopetition,” invented at the end of the twentieth century, results from the combination of “cooperation” and “competition.” In the 1990s, Ray Noorda, the CEO of Novell, used this term to describe the firm’s relationships, which were simultaneously cooperative and competitive with other firms in the IT industry (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996).

In the early 2000s, the term was seized by academics, and coopetition became a concept. Since then, interest in coopetition has continued to grow in strategic management and beyond into other disciplines and sciences. Because they combine the benefits of both cooperation and competition, coopetition strategies are expected to help firms increase their chance of success in the marketplace. As a result, coopetition has become a new paradigm, a new way to analyze social and economic phenomena.

Coopetition has become a behavioral standard for most companies in most industries. Very diverse types of firms and organizations use it widely. Coopetition among large companies or even between smaller firms helps them to overcome their specific challenges. Furthermore, large firms may also collaborate with smaller competitors. However, coopetition is not only relevant for firms; NGOs, associations, and institutions rely on coopetition to reach their objectives. Coopetition is everywhere; it is not exclusive to one industry or one activity.

Coopetition offers various benefits to develop radical and incremental innovation (Bouncken & Kraus, 2013). However, new product development is far from the only activity in which competing firms can work together. Market share, productivity, and financial performance can all be improved through collaboration with carefully chosen and closely managed coopetition (Le Roy & Czakon, 2016). Coopetition relationships can be useful across many functions in the firm, such as marketing activities (Chiambaretto et al., 2016), logistics (Wilhelm, 2011), operations (Czernek et al., 2017), or management control (Graftona & Mundy, in press). All the functions of the firm can potentially be used to foster collaboration between competing firms. This is even truer in the current economy. New issues in globalization and digitalization have contributed to the creation of new business models based on coopetition (Ritala et al., 2014; Velu, 2016).

The need for a dedicated theory of coopetition

We argue that the only way of addressing contemporary challenges that is beneficial to all involved firms and to customers is coopetition. Traditional strategies, such as pure competition or pure collaboration, are widespread across industries; their potential has widely been captured, and thus, comparative advantages have eroded. Recent development of coopetition in various economic areas challenges scholars, first in strategic management. It is absolutely essential for researchers to understand this paradoxical phenomenon and explain how it can safely lead to the creation of superior performance. To address this theoretical challenge, researchers have tried to rely on traditional perspectives in strategic management, such as competitive advantage or collaborative advantage theory.

On the one hand, competitive advantage theory, first developed by Porter (1980), explained that the competitive advantage depends on the position of the firm in its industrial environment. A rigorous analysis of the industry combined with an analysis of the strategic groups and with the value chain of the firm will make it possible to identify the best strategy for the firm. Along a similar line, Barney (1986, 1991), with the resource-based view of the firm, explains that the creation or the control of strategic resources is key to the firm’s success. Firms are invited to invest in the development of strategic resources in order to differentiate themselves from their competitors and to improve their performance.

While shifting attention from the external contingencies to the internal potential in a swift pendulum movement (Hoskinsson et al., 1999), both industry organization view and RBV face the same limitations. They conceive inter-organizational relationships exclusively through a competitive lens. They fail to incorporate collaborative relationships developed between different actors in an industry with substitutes, new entrants, or even with competitors. Firms also collaborate to actually develop the strategic resources they need to compete efficiently in the market. Consequently, competitive advantage theory is not comprehensive enough to capture the coopetition phenomenon.

On the other hand, collaborative advantage theory builds on sociological approaches to explain firm performance. From a social network perspective, firms are encouraged to develop strong collaborative ties with all members of the network. The position of the firm within the network determines its performance (Gulati et al., 2000). In a similar view, alliance theory presents alliances as the key for the success of firms (Dyer & Singh, 1998). Because firms cannot control all resources they need, they have to look for access to missing resources through alliances with partners (Gulati, 2007). The success of the firm thus relies on its ability to access “network resources” and its relational capabilities to maintain stable alliances. As a consequence, the social network and alliance theories analyze inter-organizational relationships only from a collaboration perspective. The theories neglect the competitive dimension that actually exists in any collaboration. Thus, collaborative advantage is relevant to understand coopetition, but it is not comprehensive enough and is thus inadequate to address coopetitive relationships.

As a result, both competitive advantage and collaborative advantage theories focus on only one side of the coin, either the competition or the cooperation, without considering interactions between them. By doing so, they fail to address tensions (Fernandez et al., 2014), to observe and incorporate balance (Bengtsson et al., 2016), to explain how this interaction of collaboration with competition can be understood by managers (Gnyawali & Park, 2009), and to propose how collaboration and competition interplay can be turned into successful management of coopetition (Le Roy & Czakon, 2016). As a consequence, established theories are not relevant enough to analyze the specifics of coopetition.

The emergence of a coopetition theory

Because of its paradoxical nature, coopetition invites scholars to analyze strategies, behaviors, and relationships from a dual perspective. The very nature of coopetition raises new, stimulating questions that need to be addressed by scholars. Considering the simultaneous combination of cooperation and competition, why do actors put themselves in such complexity when they have simpler alternatives? How do they address this complexity over time? What outcomes do they expect from these relationships? How do they manage potential risks? How do they capture the value created?

A dedicated theory of coopetition is needed to explain the success of firms involved simultaneously in cooperative and competitive relationships. Approaching cooperation and competition as two opposites of a continuum becomes nonsense. One of the theoretical challenges is to address both directions simultaneously, focusing on the interdependences between collaboration and competition. Building a new theory was the only option for academics to explain this new strategy. Studies, research articles, and books have flourished over recent years to understand this new strategic behavior.

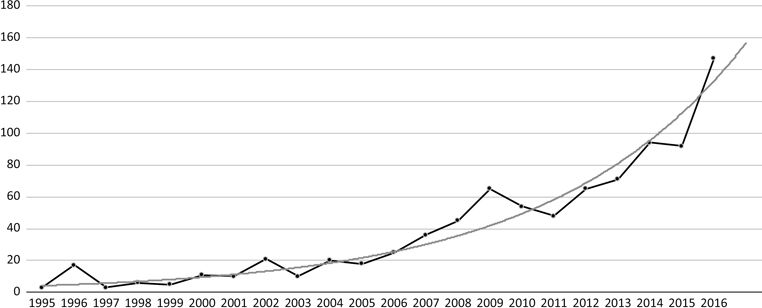

Since the seminal work of Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996), coopetition research continued to grow. As shown in Figure I.1, coopetition research has increased considerably over the last two decades. This extraordinary growth of publications on coopetition reflects a growing and sustained interest of scholars all over the world. In addition to this growth, we can notice a significant improvement of the ranking of the outlets. This publication upgrading demonstrates the recognition of coopetition as a real research topic by scholars. Looking deeper, we must highlight that these publications address a wide range and offer a large variety. Such diversity leads us to think that the coopetition concept appears as one of the richest and most inspiring concepts in strategic management. Recent publications highlight that coopetition pushes back the traditional boundaries of strategic management. Indeed, coopetition is becoming insightful to other disciplines in management (Chiambaretto et al., 2016; Graftona & Mundy, in press).

The theory of coopetition is still a work in progress. Some systematic reviews show the richness, the youngness, and the diversity of this new field of research (Czakon et al., 2014; Dorn et al., 2016). Coopetitive frameworks used by scholars are based on established theory as game theory (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996), resource-based view (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000), network theory (Sanou et al., 2016), or, more recently, cognition theory (Bengtsson et al., 2016), resource dependence theory (Chiambaretto & Fernandez, 2016), etc. There is not yet a coopetition theory as established as transaction cost theory, for example. Building a theory or some theories of coopetition is a great challenge for the future. Going into this challenge is a key to understanding contemporary and future strategies of the firm. The construction of this theory is still a work in progress. It does not start from zero, and it can be based on past coopetition studies—a journey described here as a safari.

Coopetition safari

Now that you are convinced of the interest of coopetition, you are willing to initiate or to pursue new investigations on coopetition. However, you might wonder: where should I start? What question should I address? Am I sure that this issue has not been addressed yet? How could I contribute to coopetition theory? The Routledge Companion to Coopetition Strategies will help you to find your way in the wild world of coopetition. We provide an exhaustive and structured overview of coopetition research since the birth of the concept. Therefore, this volume pursues a double objective. It will help to position your own research in the coopetition literature, and it will inspire you to conduct future studies on coopetition.

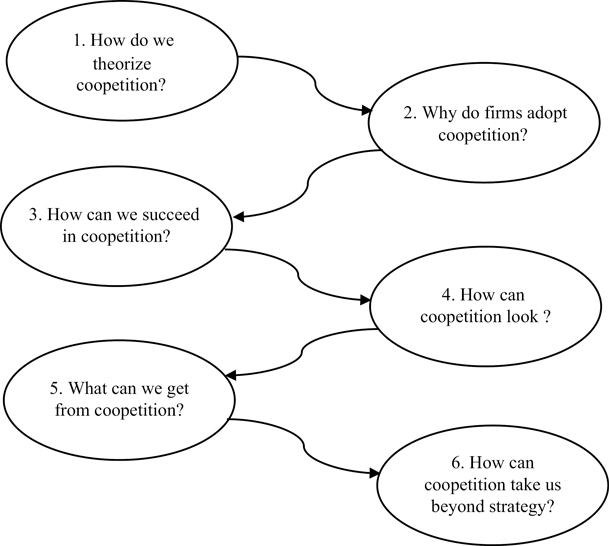

We invite you to join us for a safari into the coopetition world. Figure I.2 maps the path we will follow. We will discover, step by step, the six major questions about coopetition.

1. How do we theorize coopetition? First, it is important to understand the theoretical debates surrounding coopetition. Several theoretical approaches to coopetition are presented in the six chapters of this first part.

2. Why do firms adopt coopetition? After understanding the theoretical debates surrounding coopetition, six chapters will analyze the drivers, antecedents, and determinants explaining why firms adopt coopetition strategies.

3. How can firms succeed in coopetition? After understanding the drivers and antecedents of coopetition, seven chapters will develop insights about the implementation and the management of coopetition strategies.

4. What can coopetition look like? After acknowledging the implementation and the management of coopetition, we explore the morphology of coopetition through six chapters.

5. What can we get from coopetition? After studying the morphology of coopetition, we invite you to dig into its outcomes and implications.

6. How can coopetition take us beyond strategy? To end the overview of coopetition research, we would like to open new doors and to explore studies built on coopetition, but go beyond strategic management.

Is it just the beginning?

After this exciting safari, you might wonder: is coopetition research over or should we keep investigating? So much has been done; there is not much more to examine. However, we believe this is just the beginning of coopetition research.

As each chapter notes, coopetition created disruption and a new school of thought. Previous studies provided insights into some of the major questions surrounding coopetition. However, all these contributions only represent the genesis of coopetition research such that most of the questions addressed are only partially answered. Many research directions require further investigation.

We, coopetition scholars, believe that coopetition is a promising research field, but contributions to this topic have only begun. We call for more research on coopetition and for more researchers to investigate the complexity and the challenges of coopetition relationships. Coopetition research already goes beyond the boundaries of strategic management to other management fields as marketing management (Chiambaretto et al., 2016) or accounting (Graftona & Mundy, in press). Furthermore, coopetition research is now a topic in economic science (Rey & Tirole, 2013), political science (Sack, 2011), and psychology (Landkammer & Sassenberg, 2016). Moreover, coopetition research escapes from social sciences to basic science! For instance, coopetition is now a concept used in biology (Khoury et al., 2014) and physics (Chu-Hui et al., 2017)!

Therefore, we can assume that The Routledge Companion to Coopetition Strategies gives access to studies that are just the beginning of a new upcoming coopetitive world!

The Routledge Companion to Coopetition Strategies outline

This book is structured in six parts that are related to the six major questions we identified on coopetition.

Part I. Coopetition Theory. First, it is important to understand the theoretical debates surrounding coopetition. Several theoretical approaches to coopetition are presented.

The first one is offered by Maria Bengtsson (Umeå University, Sweden), Sören Kock (Hanken School of Economics, Finland), and Eva-Lena Hundgren-Eriksson (Hanken School of Economics, Finland). They provide an overview of coopetition roots and argue that micro-level-oriented theories have major potential to advance future coopetition theory.

A second approach was developed by Tadhg Ryan Charleton (Maynooth University, Ireland), Devi R. Gnyawali (Virginia Tech, USA), and Robert Galavan (Maynooth University, Ireland). They combine insights from five important theories and illustrate how an integrative approach can generate a more systematic understanding of coopetition.

A third perspective was proposed by Frédéric Le Roy (University of Montpellier and Montpellier Business School, France), Anne-Sophie Fernandez (University of Montpellier, France), and Paul Chiambaretto (Montpellier Business School and École Polytechnique, France). They present a managerial theory of coopetition, arguing that management is one of the most important factors for coopetition to be a successful strategy.

A fourth approach was taken by Wojciech Czakon (Jagiellonian University, Poland). The author advocates that coopetition at the network level displays distinctive features and promising advantages compared to dyadic coopetition. He presents the main knowledge and invites further research.

In the fifth chapter, Paavo Ritala (Lappeenranta University of Technology, Finland) and Pia Humerlinna-Laukkanen (University of Oulu, Finland) develop a dynamic interplay model of value creation and appropriation in coopetition that examines the roles and relationships of these two processes.

The last chapter of the first section is written by Giovani Battista Dagnino (University of Catania, Italy) and Anna Mina (Kore University of Enna, Italy). They provide an overview of the four phases of coopetition research and offer some hints on its convergence on a few specific issues.

Part II. Coopetition Antecedents and Drivers. After understanding the theoretical debates surrounding coopetition, six chapters will analyze the drivers, antecedents, and determinants explaining why firms adopt coopetition strategies.

The first chapter, written by Wojciech Czakon (Jagiellonian University, Poland) and Katarzyna Czernek-Marszałek (University of Katowice, Poland), explains how different trust-building mechanisms encourage competitors to enter into two types of dyadic and network-collaborative relationships.

The second chapter, proposed by Frédéric Le Roy (University of Montpellier and Montpellier Business School, France), Frank Lasch (Montpellier Business School, France), and Marc Robert (Montpellier Business School, France), questions the best partner choice in an innovation network. They underline in which conditions a competitor is the best partner for innovation.

In a third chapter, Marcello Mariani (University of Reading, United Kingdom) exposes the role of policy makers and regulators in driving and affecting coopetition. The author shows that economic actors did not intentionally plan to coopete before the external institutional stakeholders created the conditions for the emergence of coopetition.

Fourth, Patrycja Klimas (University of Katowice, Poland) identifies organizational cultural features and cultural models that could drive coopetitive relationships in different industries.

Fifth, Anne Mione (University of Montpellier, France) introduces the context of standardization as an antecedent of coopetitive relationships. Interactions between standardization and coopetition are discussed.

Finally, Mahito Okura (Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts, Japan) and David Carfì (University of California, USA) explain the advantages of building on game theory to understand coopetition. They present some models and encourage further research.

Part III. Coopetition Tensions and Management. After understanding the drivers and antecedents of coopetition, seven chapters will develop insights about the implementation and the management of coopetition strategies.

The first chapter, written by Annika Tidström (University of Vaasa, Finland), highlights the tensions resulting from the combination of cooperation and competition. She encourages a dynamic, multi-level, and practice perspective to analyze the phenomenon.

In the second chapter, Anne-Sophie Fernandez (University of Montpellier, France) and Paul Chiambaretto (Montpellier Business School and École Polytechnique, France) study the specific tension related to simultaneously sharing and protecting information in coopetitive relationships. They analyze the resulting tensions and suggest ways to manage those efficiently in coopetitive projects.

Third, Isabel Estrada (University of Groningen, Netherlands) focuses her attention on knowledge management in coopetitive projects. Coopetitors need to share their knowledge with one another and, at the same time, protect their knowledge from one another. She highlights promising directions to advance the field.

Fourth, Eva-Lena Lundgren-Henriksson (Hanken School of Economics, Finland) and Sören Kock (Hanken School of Economics, Finland) study the place of individuals in coopetition. They discuss possible incorporation of the sensemaking perspective to analyze the interplay of discourses and emotions at the individual and collective levels.

In the fifth chapter, Anne-Sophie Fernandez (University of Montpellier, France) and Frédéric Le Roy (University of Montpellier and Montpellier Business School, France) reveal an original organizational design and a specific managerial principle to manage coopetition at the project level.

The sixth chapter, written by Tatbeeq Raza-Ullah (Umeå University, Sweden), Maria Bengtsson (Umeå University, Sweden), and Vladimir Vanyushyn (Umeå University, Sweden), develops the concept of coopetition capability. Coopetition capability helps managers to address coopetition paradox inherent to alliances between competitors and the resulting paradoxical tensions.

Finally, Stefanie Dorn (University of Cologne, Germany) and Sascha Albers (University of Antwerp, Belgium) propose an integrative multi-level approach to coopetition management. They highlight the interdependencies between these different levels.

Part IV. Coopetition at Different Levels. After acknowledging the implementation and the management of coopetition, we explore the morphology of coopetition through six chapters.

First, Philippe Baumard (CNAM, France) introduces some thoughts about the possible asymmetric gains when small and large firms coopete. He shows that the mismatch of scale between the partners can create dramatic levels of asymmetry.

In a second chapter, Paul Chiambaretto (Montpellier Business School and École Polytechnique, France) and Anne-Sophie Fernandez (University of Montpellier, France) adopt a portfolio perspective to analyze the evolution of coopetition. They show that the share of coopetition in an alliance portfolio tends to increase under high levels of uncertainty.

Third, Aleksios Gotsopoulos (Sungkyunkwan University, South Korea) shows that coopetition could occur in larger groups, involving larger size and more diverse resources. He encourages further research on coopetitive groups to grasp their dynamics.

Alain Wegmann (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland), Paavo Ritala (Lappeenranta University of Technology, Finland), Gorica Tapandjieva (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland), and Arash Golnam (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland) show in the fourth chapter that ecosystem is a useful concept for analyzing strategies in which competitors are also considered complementary partners.

In the fifth chapter, Heloise Berkowitz (CNRS-Toulouse School of Management, France) and Jamal Azzam (Toulouse School of Management, France) focus on the dynamics of coopetition in meta-organizations. They explore coopetition among actors who agree to license their patents through meta-organizational devices such as patent pools.

Finally, Alain Jeunemaître (École Polytechnique, France), Hervé Dumez (École Polytechnique, France), and Benjamin Lehiany (SKEMA Business School and École Polytechnique, France) present coopetition as a multifaceted concept. They analyze how visuals substantiate the concept and how far visualization may explain it and recommend the use of specific templates.

Part V. Coopetition Outcomes and Implications. After studying the morphology of coopetition, we invite you to dig into its outcomes and implications.

We will take the first step with Johanna Gast (Montpellier Business School, France), Wolfang Hora (University of Liechtenstein, Liechtenstein), Ricarda Bouncken (Bayreuth University, Germany), and Sascha Kraus (ESCE, France) to explore the complicated relationship between coopetition and innovation. The authors analyzed quantitative contributions to present the debate on coopetition and innovation performance.

Then, André Nemeh (Rennes School of Business, France) presents a discussion about coopetition strategy and the first-mover advantage (FMA) perspective. He shows that different approaches to orchestration of resources will lead to different benefits/speeds of products’ introduction for coopetitive NPD projects.

Third, Marcus Holgersson (Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden) offers a reflection on intellectual property management in technology-based coopetition. He designs a framework to analyze IP agreements in coopetition and shows that knowledge, technology, and IP can be protected to enable controlled sharing through licensing in coopetition.

In the fourth chapter, Paavo Ritala (Lappeenranta University of Technology, Finland) presents an overview of previous studies about coopetition and market performance. He reviews the existing evidence for key mechanisms, contingencies, and practical examples to explain how and why a firm’s market performance is affected by its coopetition strategy.

Fifth, Jako Volschenk (University of Stellenbosch Business School, South Africa) discusses the different types of value that can be generated and captured in coopetition. He incorporates the stakeholder theory and the six capital models into an integrated typology of value creation in coopetition.

Lastly, Chandler Velu (University of Cambridge, United Kingdom) explores the relationship between business model design and coopetition-based strategies among competing firms. The chapter proposes a framework on how, when, and why business model innovation is required for coopetition-based strategies in order to contribute to competitive advantage.

Part VI. Coopetition Beyond Strategy. To end the overview of coopetition research, we would like to open new doors and to explore studies built on coopetition but that go beyond strategic management.

The first perspective is offered by David Teece (Berkeley Haas, USA). Considering that coopetition can take numerous forms, David Teece analyzes strategic aspects of these arrangements and discusses how the dynamic capabilities’ framework addresses the fundamental issues of how coopetition arrangements are selected.

Second, a marketing approach to coopetition is proposed by Călin Gurău (Montpellier Business School, France), Paul Chiambaretto (Montpellier Business School and École Polytechnique, France), and Frédéric Le Roy (University of Montpellier and Montpellier Business School, France). After defining the concept of coopetitive marketing and its origins, the authors show the interest of investigating coopetition strategies through a marketing lens, such as pricing or branding policies.

In a third chapter, Thuy Seran (University of Montpellier, France) and Hervé Chappert (University of Montpellier) combine management accounting and strategy approaches to shed new light on coopetitive tension management. Based on Simon’s levers of control, they design and discuss an integrative framework to efficiently manage coopetition at the network level.

Fourth, Miriam Wilhelm (University of Groningen, the Netherlands) opens a discussion between coopetition and supply chain management. She outlines the concept of vertical coopetition that occurs in buyer–supplier relations, and she demonstrates the value of applying a triadic perspective on vertical coopetition.

In the fifth chapter, Malin Näsholm (Umeå University, Sweden) and Maria Bengtsson (Umeå University, Sweden) adopt an entrepreneurship perspective on coopetition. They discuss the specificities of small firms that make coopetition important for their growth and success but also make them particularly vulnerable. They conclude on the capabilities required to make coopetition a successful strategy for SMEs.

Finally, Frédéric Le Roy (University of Montpellier and Montpellier Business School, France) and Henry Chesbrough (Berkeley Haas, USA) develop the concept of open coopetition, combining insights from both the open innovation and coopetition literatures. After defining the concept, they question the key success factors of open innovation based on collaboration with a competitor.

References

Barney, J. B. (1986). Types of competition and the theory of strategy: Toward an integrative framework. Academy of Management Review, 11(4), 791–800.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2000). “Coopetition” in business networks—to cooperate and compete simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(5), 411–426.

Bengtsson, M., Raza-Ullah, T., & Vanyushyn, V. (2016). The coopetition paradox and tension: The moderating role of coopetition capability. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 19–30.

Bez M., Le Roy F., Gnyawali D. Dameron S. (2016). Open innovation between competitors: A 100 billion dollars case study in the pharmaceutical industry. 3th World Open Innovation Conference, Barcelona, Spain.

Bouncken, R. B. & Kraus, S. (2013). Innovation in knowledge-intensive industries: The double-edged sword of coopetition. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 2060–2070.

Brandenburger, A. M. & Nalebuff, B. J. (1996). Co-opetition. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group.

Chiambaretto, P. & Fernandez, A.-S. (2016). The evolution of coopetitive and collaborative alliances in an alliance portfolio: The Air France case. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 75–85.

Chiambaretto, P., Gurău, C., & Le Roy, F. (2016). Coopetitive branding: Definition, typology, benefits and risks. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 86–96.

Chu-Hui, F, Dong, Y., Yi-Mou, L., & Jin-Hui W. (2017). Coopetition and manipulation of quantum correlations in Rydberg atoms. Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics, 50(11).

Czakon, W., Mucha-Kus, K., & Rogalski, M. (2014). Coopetition research landscape – A systematic littérature review 1997–2010. Journal of Economics & Management, 17, 121–150.

Czakon, W. & Czernek, K. (2016). The role of trust-building mechanisms in entering into network coopetition: The case of tourism networks in Poland. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 64–74.

Czernek, K., Czakon, W., & Marszałek, P. (2017). Trust and formal contracts: Complements or substitutes? A study of tourism collaboration in Poland. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(4), 318–326.

Dorn, S., Schweiger, B., & Albers S. (2016). Levels, phases and themes of coopetition: A systematic literature review and research agenda. European Management Journal, 34 (5): 484–500.

Dyer, J. H. & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660–679.

Fernandez, A.-S. & Chiambaretto, P. (2016). Managing tensions related to information in coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 66–76.

Fernandez, A.-S., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Sources and management of tension in co-opetition case evidence from telecommunications satellites manufacturing in Europe. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 222–235.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Park, B.-J. R. (2009). Co-opetition and technological innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises: A multilevel conceptual model. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(3), 308–330.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Park, B.-J. R. (2011). Co-opetition between giants: Collaboration with competitors for technological innovation. Research Policy, 40(5), 650–663.

Graftona, J. & Mundy, J. (in press), Relational contracting and the myth of trust: Control in a co-opetitive setting. Management Accounting Research.

Gulati, R., Nohria, N., & Zaheer, A. (2000). Strategic networks. Strategic Management Journal, 203–215.

Gulati, R. (2007). Managing Network Resources: Alliances, Affiliations, and other Relational Assets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hoskisson, R. E., Wan, W. P., Yiu, D., & Hitt, M. A. (1999). Theory and research in strategic management: Swings of a pendulum. Journal of Management, 25(3), 417–456.

Khoury, G. A., Liwo, A., Khatib, F., Zhou, H., Chopra, G., Bacardit, J., Bortot, L. O., Faccioli, R. A., Deng, X., He, Y., Krupa, P., Li, J., Mozolewska M. A., Sieradzan, A. K., Smadbeck, J., Wirecki, T., Cooper, S., Flatten, J., Xu, K., Baker, D., Cheng, J., Delbem, A. C. B., Floudos, C. A., Keasar, C., Levitt, M., Popović, Z., Scheraga, H. A., Skolnick, J., Crivelli, S. N., & Players, F. (2014). WeFold: A coopetition for protein structure prediction. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics, 82(9), 1850–1868.

Landkammer, F. & Sassenberg, K. (2016). Competing while cooperating with the same others: The consequences of conflicting demands in co-opetition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(12), 1670–1686.

Le Roy, F. & Czakon, W. (2016). Managing coopetition: the missing link between strategy and performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 3–6.

Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competition. New York: The Free Press.

Rey, P. & Tirole, J. (2013). Cooperation vs. collusion: How essentiality shapes co-opetition. Working paper, n°IDE-801, October 13, Toulouse School of Economics, Toulouse, France.

Ritala, P., Golnam, A., & Wegmann, A. (2014). Coopetition-based business models: The case of Amazon. com. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 236–249.

Sack, D. (2011). Governance failures in integrated transport policy – on the mismatch of “co-opetition” in multi-level systems. German Policy Studies, 7(2), 43–70.

Sanou, H., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. (2016). How does centrality in coopetition network matter? Empirical investigation in the mobile telephone industry. British Journal of Management, 27, 143–160.

Velu, C. (2016). Evolutionary or revolutionary business model innovation through coopetition? The role of dominance in network markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 124–135.

Wilhelm, M. M. (2011). Managing coopetition through horizontal supply chain relations: Linking dyadic and network levels of analysis. Journal of Operations Management, 29(7), 663–676.