Maria Bengtsson, Sören Kock, and Eva-Lena Lundgren-Henriksson

Introduction

The former industrial logic—encompassing internal resources and a clean picture of the business environment—has largely been replaced by an industrial logic based on the ability to access external resources in a networked and shared economy. This has changed the previously clear anchorage of various activities within the boundaries of an organization, and made the roles of different firms (i.e., competitors, customers, and suppliers) unclear, which makes the understanding of new forms of business relationship and network contexts important. Research on coopetition had already acknowledged this change in the 1990s and has increased dramatically during the last fifteen years (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, 2016). It has even been argued to be a new paradigm for research that takes the changed character of today’s business into account (Bengtsson et al., 2010; Yamï et al., 2010).

Research on coopetition has been developed over almost three decades. Seminal work in the 1990s focused on the simultaneity of contradicting logics of cooperation and competition (Bengtsson & Kock, 1995, 1999; Gnyawali & Madhavan, 2001), different types of coopetition (Dowling et al., 1996; Lado et al., 1997), and coopetition strategies (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000; Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996). This work primarily provided conceptual attempts to broadly defined coopetition, its antecedents and outcomes, and capabilities or strategies needed to manage coopetition. Recent reviews of the field show that further recent research on coopetition has contributed extensively to the field’s development by providing empirical examinations of coopetition focusing on more specific dimensions (Bengtsson et al., 2013; Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, 2016; Bouncken et al., 2015; Gast et al., 2015; Gnyawali & Song, 2016). This suggests that the research field has reached a breaking point, and that it is time to reflect upon the past and present in terms of what has been accomplished, as well as to generate agendas for future research.

Coopetition research makes an essential contribution to the understanding of today’s changing business environment, but the field of research is fragmented. The definitions and adopted theoretical perspectives are shattered, and the theory of coopetition research has been argued to suffer from incompleteness. Several scholars argue that the field is lacking coherence in the adoption of theories (Bengtsson et al., 2010), and that the lack of precision when it comes to adopting a general definition of coopetition has even been problematic, hindering further advancements of the field (Bengtsson et al., 2013; Gnyawali & Song, 2016). In this chapter, we will discuss the the rooting of coopetition and discuss the implications of the incongruence; we suggest that one solution could be to acknowledge that coopetition appears on many levels, and we also emphasize the multi-level character of the phenomenon, which has been underresearched.

Definitions and theoretical rooting of coopetition

We argue that coopetition is a business relationship, but in previous research the term “coopetition” has been used to describe many different things. Concepts such as coopetition strategy and coopetition advantages (Padula & Dagnino, 2007; Yamï et al., 2010), coopetition as practices (Dahl et al., 2016) and coopetition paradox (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, 2017; Gnyawali et al., 2016; Raza-Ullah, 2017), as well as coopetition mindsets (Gnyawali & Park, 2009) and coopetition business models (Ritala et al., 2014), have been born. These different conceptualizations bring in different theoretical perspectives on coopetition. It is important to further discuss the underlying assumptions and theoretical rooting of different concepts to detect what coopetition could be.

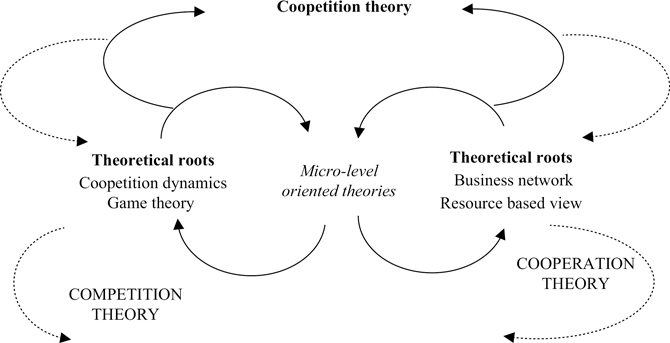

Network theory, research on competition dynamics, the resource-based view (RBV) and game theory are four important roots of coopetition research (dashed arrows in Figure 1.1.). This rooting has implications for how the phenomenon is depicted and understood. By tradition, relationships between buyers and sellers have been in focus when studying business networks, while relationships between competing companies have received less research attention within this research field (Ford & Håkansson, 2013). Actors are, according to network theory, embedded in relationships with other firms in order to gain access to needed resources (Kock, 1991). Håkansson and Snehota (2006) argue, in line with Richardson (1972), that “no business is an island,” indicating that companies are involved in long-term relationships and that atomistic companies do not exist. The relationships in focus have mainly been cooperative relationships. In contrary, theories on competitive dynamics explain the interaction among competitors through firms’ actions and responses, and pay little attention to the cooperation between firms (c.f. Chen, 1996; Smith et al., 1991). Inter-firm competition is explained by the structure of industry and the behavior of the firms, and emphasizes the repertoires of strategic actions that firms can use to achieve dominance and shape the market (c.f. Chen & Miller, 1994; Santos & Eisenhardt, 2009). Research on coopetition has developed by linking these two lines of research together.

Network researchers started to realize that “a firm must coordinate its management of horizontally and vertically directed network relationships in order to obtain a favorable and stable overall network position” (Elg & Johansson, 1996), and started to evoke the idea that it is not enough to only study relationships of cooperation; competition also plays a vital role in networks. The role of cooperation for dynamic coopetition was also stressed. Gnyawali and Madhavan (2001) provided an early attempt at further developing the theory on competitive dynamics by explaining competitive actions and responses with firms embedded in networks, aguing that “actors’ purposeful actions [in competition] are embedded in concrete and enduring strategic relationships that impact those actions and their outcomes”. More recently, Zang et al. (2010: 78) have extended this argument and propose that the presence of competition “is not limited to horizontal alliances but is contained in any type of alliances,” implying that coopetition is involved in all relationships.

To acknowledge that cooperation and competition are equally important and coexistent challenges the previously clear distinction between actors with different roles in networks and industries. Traditional network theory assumes that the relations between a firm and its customers and suppliers are well-defined and that the roles of different actors in relation to a focal firm are clear. The definition of roles is nowadays difficult as roles are not as clear-cut as they used to be. A customer in one activity can at the same time be a competitor, supplier or partner in other activities. Moreover, different forms of direct and indirect competition and cooperation further blur roles and their definitions. Similarly, the definition of competitors was also once clear. All companies in the same industry are generally seen as competitors (Porter, 1980), indicating that all companies providing similar product solutions that satisfy similar customer needs are competitors. This definition has been nuanced by defining competitors as firms in the same strategic group that differ from other groups of firms in the same industry through strategic decisions.

The conceptualization of firms, based on their roles, as competitors, partners, suppliers, and so on is less relevant in present business practice as the same actors can compete and cooperate at the same time (Bengtsson & Kock, 1999, 2000). The concept of role-set, developed by Merton (1957), and the concept of role conflict, presented by Shenkar and Zeira (1992), have been suggested as useful means to solve this problem (Bengtsson & Kock, 2003). A firm can have at least five different roles—as buyer, supplier, competitor, collaborative partner, and complementary actor—that can be part of the role-set in a firm’s relation to another firm. Thus, the activities performed within a relationship can enable or force actors to simultaneously take on many different roles, with conflicts or tension possibly arising between them. Ross and Robertson (2007) address this problem in a similar way, introducing the concept of compound relationships, suggesting that such relationships consist of many sub-relationships. However, we suggest that to capture coopetition relationships between firms we should abound the concept of roles when dyadic relations are discussed and instead talk about activities and the interactions related to them.

Based on the resource-based view (e.g., Barney, 1991; Peteraf, 1993) coopetition research focuses also on the firm specific advantages that can be obtained through coopetition. Cooperating with competitors becomes a quest for resources that would otherwise be inaccessible for firms (e.g., Bonel & Rocco, 2009; Gnyawali & Park, 2009) that in turn can be used to create and ameliorate a firm’s competitive advantage. The firm’s capability, based on its own resources and strength, to leverage externally accessed knowledge and resources is critical for the firm’s appropriation of them for private gains. Finally, in line with research on dynamic competition, game theory emphasizes the dynamic aspects of interactions among firms, which in turn are linked to coopetition as strategy. Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996) extend the pure competitive perspective of game theory and argue that “[the] firm can use game theory to achieve positive-sum gains by changing the players, the rules of the game, and the scope of the game” (Gnyawali & Park, 2009: 312). Positions and roles are argued to be important when coopetition strategies are developed. An actor’s position in a business network helps in accessing new competitive capabilities and enhances the possibilities to attract new researches and relationships (Gnyawali & Madhavan, 2001). If we also acknowledge that a focal firm can have both direct relationships with a firm and, through this relationship, also have indirect relationships with other firms in the network it becomes important to understand the network context to be able to navigate in a business environment were there are multiple, continuously changing roles for different actors. It is more relevant to discuss roles and positions on the network level as firms on an aggregated level can be defined as mainly being a competitor, customer, or supplier within a specific industry or network. The dynamic aspects of coopetition put great demands not only on firms, but also on current research. Dynamic business models need to be developed that capture the dynamic interplay between actors in networks and that account for the continuously changing roles that different actors play.

The study of coopetition must still be regarded as a nascent field of research. Many empirical studies have been undertaken demonstrating the relevance of coopetition in business life and research (Bouncken et al., 2015; Gnyawali & Song, 2016); however, several challenges point to the need to widen the scope of the studies. For example, in order to understand the real dynamics of coopetition, focus needs to shift upwards, moving from studying one relationship to studying the network level (e.g., Czakon & Czernek, 2016). At the same time, we need to move downward, deeper analyzing the coopetitive activities, as well as different perceptions of these, between the individuals in organizations that are involved in coopetition. Put differently, we need to understand the origin and coping of tensions and conflicts at multiple levels that coopetition creates through the transfer and non-transfer of knowledge between organizations that are positioned as competitors but also cooperate with each other, as an outcome of getting access to resources that they do not themselves possess.

Emerging trends and a research agenda bringing together multiple levels

Research in coopetition needs to be improved to fully account for the multilevel nature of coopetition. Dyadic relationships, coopetition in networks and coopetition strategies have been explored in extensive research studies, but it is often not clearly stated whether it is coopetition in networks or dyadic relationships that the focus of a study (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, 2016). Recent research points at the importance of coopetition practice, tension and trust in coopetition, and coopetition mindsets that are all fundamentally related to individuals and what they think, feel, and do (Huy, 2010) in a situation of coopetition. Accordingly, theoretical approaches focusing on the micro-foundation of coopetition and the interplay between the individual, firm, inter-organizational and network level are needed, yet socio-psychological theories, and theories on organizational behavior, are less frequently addressed in the field. Few studies have investigated the link between the individual level and outcomes and developments of higher-level constructs, such as relational dynamics, strategy, or capabilities (Bengtsson & Kock, 2014; Bengtsson et al., 2016b; Gnyawali et al., 2016; Lundgren-Henriksson & Kock, 2016b; Park et al., 2014). We therefore believe that potential exists for filling these gaps by embracing and further developing the recently emergent trends in the field, as well as integrating these with the established theoretical roots (solid arrows in Figure 1.1). We will now discuss the emergent trends and how they can contribute to a future research agenda.

Increased interest in the micro-foundation and the multilevel nature of coopetition

A general research trend in the coopetition field is a move toward individual and microlevel approaches to coopetition. This is, for example, manifested through conferences with special themes or tracks embracing the strategy-as-practice approach (e.g., the special track in the IMP conference in Kolding, Denmark in 2015 and the 6th Workshop on Coopetition Strategy in Umeå in 2013). An increased interest has, for example, been given to the discussion on managing coopetition tensions, i.e., the actual manifestation of coopetition paradoxes (Gnyawali et al., 2016; Raza-Ullah, 2017a) stemming from simultaneous cooperation and competition (Bengtsson et al., 2016b; Gnyawali et al., 2016; Le Roy & Czakon, 2016; Séran et al., 2016; Tidström, 2014). The interest in addressing micro-level mechanisms and drivers underlying coopetition formation and development, such as emotions and trust (Czernek & Czakon, 2016; Raza-Ullah et al., 2014; Raza-Ullah, 2017), as well as routines and practices (Dahl, 2014; Dahl et al., 2016; Lundgren-Henriksson & Kock, 2016a, 2016b), has also emerged. Closely related, but still in its infancy, is to approach coopetition strategies as emergent through practice (Mintzberg & Waters, 1985; Wittington 2007). Some studies have acknowledged the simultaneity of deliberate and emergent features of coopetition (Dahl et al., 2016; Mariani, 2007), signaling the need to acknowledge and investigate both intentional and unintentional features in order to fully understand developments and outcomes of coopetition strategies and relationships.

Another identified field of emergence is the application of institutional and stakeholder theories to coopetition (Akpinar & Vincze, 2016; Volschenk et al., 2016). This discussion has the potential to contribute to the research field by addressing the important issue of multiple actors’ influence on the formation, development of dynamics, and outcomes of coopetition, both within and outside organizational boundaries (Kylänen & Rusko, 2011). For example, previous advances have shown that external institutional actors might influence the formation and development of coopetition strategies (Mariani, 2007; Tidström, 2014), and that the existence of conflicting goals within the organization might influence the development of the coopetition dynamics (Dahl, 2014). There has recently been a call for multilevel research looking deeper into the cognitive and behavioral dimensions of coopetition as well as the role of multiple actors in coopetition (Bengtsson & Kock, 2014; Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, 2016; Fernandez et al., 2014; Gnyawali et al., 2016; Raza-Ullah et al., 2014; Tidström, 2014), particularly through the adoption of new theories (Bengtsson & Kock, 2014; Le Roy & Czakon, 2016).

A micro foundations approach could thus explain why different outcomes occur by focusing on how individuals and social processes across levels are interrelated (cf. Felin et al., 2012). We believe that the micro foundations approach could substantially complement the theoretical roots, increasing understanding of the relational dimension regarding how interrelated processes at multiple actor levels (Bengtsson et al., 2010) aggregate to changes in cooperation and competition (Dahl, 2014; Mattsson & Tidström, 2015), and accordingly in roles in business networks.

Integrating the emerging trends: Bridging the micro and macro levels

As previously stated by a number of scholars (e.g., Bengtsson & Kock, 2014; Bouncken et al., 2015), coopetition as a concept needs further clarification, both in terms of its key characteristics as well as its levels of analysis. Following the general trend particularly in strategic management, moving from process-based research towards practice and micro-level research (Whittington, 2007), we believe that scholars need to move beyond descriptive research, such as examining what processes and activities occur, as well as what is generated, to investigating in-depth how coopetition processes and activities form and develop in practice, as well as why these processes and activities take place.

We hence call for a stronger focus on how multiple actors—from the network to individual levels—influence, and are influenced by, coopetition. This would incorporate an extension of the goals and motives included in coopetition strategies from pure economic values to also include social ones (Lundgren-Henriksson & Kock, 2016a), as well as an extension of more stakeholders included in the coopetition picture (Chen & Miller, 2015). We believe that micro-level approaches to strategy and capabilities can assist in accomplishing this shift (Bengtsson et al., 2016a). What the strategy-as-practice approach particularly recognizes is the fact that strategic participation is driven by individual incentives, and that views of strategies do not necessarily converge across the organization (Jarzabkowski et al., 2007). When developing coopetition at inter- and intra-organizational levels, stipulated cooperative and competitive goals and activities in the beginning might not be realized, or new goals and activities might arise along the way, that might diverge (Dahl, 2014; Dahl et al., 2016). Accordingly, there might be stakeholders other than the direct coopeting parties, either intra-organizational or external (Whittington, 2006), with their own interests and goals to realize, which might influence the formation and development of coopetition in an intentional or unintentional manner (Akpinar & Vincze, 2016; Mariani, 2007; Volschenk et al., 2016).

We believe that the above-mentioned areas of advancement and emerging trends call for a redefinition of current ideas about coopetition, where the concept of paradox is developed further. Hence, we propose that coopetition should be defined as simultaneous intentional and unintentional cooperative and competitive interaction between multiple stakeholders at any level of analysis, which are driven by different interests and goals and that, subsequently, form a paradoxical relationship.

Extending the notion of coopetition capabilities

Finally, micro-level approaches can in particular contribute to the coopetition capability discussion. In order to combine the resources obtained at the network and inter-organizational levels with internal resources, as well as leverage from these (Bouncken & Kraus, 2013; Ritala 2012), firms engaging in coopetition must draw upon their capabilities (e.g., Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2013). Coopetition researchers have accordingly proposed that the capability signifies support of both value creation in inter-competitor interactions and intra-organizational value appropriation activities in order to profit from coopetition (Gnyawali & Park 2009; Luo et al., 2006; Luo, 2007; Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009; Ritala & Tidström, 2014). Furthermore, coopetition capability also needs to embrace an ability to manage paradoxical tension and the cognitive difficulty and emotional ambivalence of which it consists (Raza-Ullah, 2017b).

We have also seen a recent increased interest in approaching coopetition capabilities as coping with tensions (Bengtsson et al., 2016b; Gnyawali et al., 2016; Le Roy & Fernandez, 2015; Raza-Ullah et al., 2014, Raza-Ullah, 2017a) at multiple levels, including the individual level, as well as from a cognitive point of view—as the individual ability to think paradoxically (Bengtsson et al., 2016b; Gnyawali et al., 2016). Furthermore, we also need the capability to manage ambivalent emotions as part of paradoxical tension (Raza-Ullah, 2017b). This interest coincides with recent research on micro foundations, where a “managerial cognitive capability” has been introduced that includes cognitive and psychological processes (Helfat & Peteraf, 2015: 832) to understanding macro-level constructs. The commonly held assumption in coopetition studies is that these capabilities are to be found in the minds of top managers (Luo, 2007; Peng & Bourne, 2009); yet, in-depth knowledge of this mindset is scarce (Fernandez et al., 2014). Recent research also shows that coopetition tensions occur at lower levels in organizations, and that a capability accordingly involves creating understandings of coopetition that are shared internally in the organization (Bengtsson et al., 2016b).

Applying a micro-level-oriented approach to coopetition capabilities could thus complement these insights, by approaching the strategic dimension of coopetition from a novel perspective. By going deeper into the psychological and cognitive dimensions (Bengtsson & Kock, 2014; Le Roy & Czakon, 2016) of both managers and employees when it comes to simultaneous cooperative and competitive interactions, knowledge of the nature and origin—as well as individual-level perceptions and coping—of tensions and role conflicts could therefore be increased. A micro foundations approach to coopetition (Gnyawali et al., 2016) would hence establish an explanatory link between aggregated coping of tensions at multiple actor levels, and more (Lindström & Polsa, 2016; Morris et al., 2007) or less (Bouncken & Kraus, 2013) beneficial coopetition strategy outcomes.

We have argued throughout this chapter that a more systematic integration of micro-level perspectives into coopetition research has potential to build a solid coopetition theory. We therefore hope that the suggested research agenda will inspire future research at the macro level, such as coopetition capabilities, dynamics, and strategies, by addressing emerging concepts in the field, such as emotions, cognition, and social processes, from the perspectives of multiple individuals.

References

Akpinar, M. & Vincze, Z. (2016). The dynamics of coopetition: A stakeholder view of the German automotive industry. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 53–63.

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Bengtsson, M., Eriksson, J., & Wincent, J. (2010). Co-opetition dynamics: An outline for further inquiry. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 20(2), 194–214.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (1995) Relationships among competitors in business networks – competition and cooperation in three Swedish industries. Paper presented at the 13th Nordic Conference on Business Studies in Copenhagen, Denmark, August, 14–16.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (1999). Cooperation and competition in relationships between competitors in business networks. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 14(3), 178–193.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2000). “Coopetition” in business networks – to cooperate and compete simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(5), 411–426.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2003) Tension in co-opetition. Developments in Marketing Science 26, 38–42

Bengtsson, M., Johansson, M., Näsholm, M., & Raza-Ullah, T. (2013). A systemic review of coopetition: Levels and effects on different levels. Paper presented at the 13th EURAM Conference, Istanbul, Turkey, June 26–29.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2014). Coopetition – Quo vadis? Past accomplishments and future challenges. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 180–188.

Bengtsson, M., Kock, S., Lundgren-Henriksson, E.-L., & Näsholm, M. (2016a). Coopetition research in theory and practice: Growing new theoretical, empirical, and methodological domains. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 4–11.

Bengtsson, M. & Raza-Ullah, T. (2016). A systematic review of research on coopetition: Towards a multi-level understanding. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 23–39.

Bengtsson, M. & Raza-Ullah, T. (2017). Paradox at a inter-firm level: A coopetition lens. In Lewis, M., Smith, W., Jarzabkowski P., & Langly, A. (Eds), Oxford Handbook of Organizational Paradox: Approaches to Plurality, Tensions and Contradictions.

Bengtsson, M., Raza-Ullah, T., & Vanyushyn, V. (2016b). The coopetition paradox and tension: The moderating role of coopetition capability. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 19–30.

Bonel. E. & Rocco, E. (2009). Coopetition and business model change – A case-based framework of coopetition-driven effects. In Dagnino, G. B. & Rocco, E. (Eds), Coopetition strategy – Theory, experiments and cases (pp. 191–218). Oxon: Routledge.

Bouncken, R. B. & Kraus, S. (2013). Innovation in knowledge-intensive industries: The double-edged sword of coopetition. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 2060–2070.

Bouncken, R. B., Gast, J., Kraus, S., & Bogers, M. (2015). Coopetition: A systematic review, synthesis, and future research directions. Review of Managerial Science, 9(3), 577–601.

Brandenburger, A. M. & Nalebuff, B. J. (1996). Co-opetition. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group.

Chen, M.-J. (1996). Competitor analysis and interfirm rivalry: Toward a theoretical integration. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 100–134.

Chen, M.-J. & Miller, D. (1994). Competitive attack, retaliation and performance: An expectancy‐valence framework. Strategic Management Journal, 15(2), 85–102.

Chen, M.-J. & Miller, D. (2015). Reconceptualizing competitive dynamics: A multidimensional framework. Strategic Management Journal, 36(5), 758–775.

Czakon, W., & Czernek, K. (2016). The role of trust-building mechanisms in entering into network coopetition: The case of tourism networks in Poland. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 64–74.

Czernek, K. & Czakon, W. (2016). Trust-building in tourist coopetition: The case of a Polish region. Tourism Management, 52, 380–394.

Dahl, J. (2014). Conceptualizing coopetition as a process: An outline of change in cooperative and competitive interactions. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 272–279.

Dahl, J., Kock, S., & Lundgren-Henriksson, E.-L. (2016). Conceptualizing coopetition strategy as practice – A multilevel interpretative framework. International Studies of Management and Organization, 46(2–3), 94–109.

Dowling, M. J., Roering, W. D., Carlin, B. A., & Wisnieski, J. (1996). Multifaceted relationships under coopetition – Description and theory. Journal of Management Inquiry, 5(2), 155–167.

Elg, U., Johansson, U. (1996). Networking when national boundaries dissolve. European Journal of Marketing, 30(2), 61-74.

Felin, T., Foss, N. J., Heimeriks, K. H., & Madsen, T. L. (2012). Microfoundations of routines and capabilities: Individuals, processes, and structure. Journal of Management Studies, 49(8), 1351–1374.

Fernandez, A.-S., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Sources and management of tension in coopetition case evidence from telecommunications satellites manufacturing in Europe. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 222–235.

Ford, D. & Håkansson, H. (2013). Competition in business networks. Industrial Marketing Management, 42(7), 1017–1024.

Gast, J., Filser, M., Gundolf, K., & Kraus, S. (2015). Coopetition research: Towards a better understanding of past trends and future directions. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 24(4), 492–521.

Gnyawali, D. R., Madhavan, R., He, J., & Bengtsson, M. (2016). The competition-cooperation paradox in inter-firm relationships: A conceptual framework. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 7–18.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Madhavan, R. (2001). Networks and competitive dynamics: A structural embeddedness perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(3), 431–445.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Park, B.-J. (2009). Co-opetition and technological innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises: A multilevel conceptual model. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(3), 308–330.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Song, Y. (2016). Pursuit of rigor in research: Illustration from coopetition literature. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 12–22.

Helfat, C. E. & Peteraf, M. A. (2015). Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 36(6), 831–850.

Huy, Q. (2010) Emotions and strategic change. In Cameron K. S. and Spreitzer G. M. (Eds), Handbook of Positive Organizational Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Håkansson, H. & Snehota, I. (2006). No business is an island: The network concept of business strategy. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 22(3), 256–270.

Jarzabkowski, P., Balogun, J., & Seidl, D. (2007). Strategizing: The challenges of a practice perspective. Human Relations, 60(1), 5–27.

Kock, S. (1991). A Strategic process for gaining external resources through long-lasting relationships – examples from two Finnish and two Swedish industrial firms. Economy and Society no. 47, Swedish School of Economics and Business Administration, Helsinki, Finland.

Kylänen, M. & Rusko, R. (2011). Unintentional coopetition in the service industries: The case of Pyhä-Luosto tourism destination in the Finnish Lapland. European Management Journal, 29(3), 193–205.

Lado, A. A., Boyd, N. G., & Hanlon, S. C. (1997). Competition, cooperation, and the search for economic rents: A syncretic model. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 110–141.

Le Roy, F. & Czakon, W. (2016). Managing coopetition: The missing link between strategy and performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 3–6.

Le Roy, F. & Fernandez, A-S. (2015). Managing coopetitive tensions at the working-group level: The rise of the coopetitive project team. British Journal of Management, 26(4), 671–688.

Lindström, T. & Polsa, P. (2016). Coopetition close to the customer – A case study of a small business network. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 207–215.

Lundgren-Henriksson, E.-L. & Kock, S. (2016a). A sensemaking perspective on coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 97–108.

Lundgren-Henriksson, E.-L. & Kock, S. (2016b). Coopetition in a headwind – The interplay of sensemaking, sensegiving, and middle managerial emotional response in coopetitive strategic change development. Industrial Marketing Management, 58, 20–34.

Luo, Y. (2007). A coopetition perspective of global competition. Journal of World Business, 42(2), 129–144.

Luo, X. M., Slotegraaf, R. J., & Pan, X. (2006). Cross-functional “coopetition”: The simultaneous role of cooperation and competition within firms. Journal of Marketing, 70(2), 67–80.

Mariani, M. M. (2007). Coopetition as an emergent strategy: Empirical evidence from an Italian consortium of opera houses. International Studies of Management and Organization, 37(2), 97–126.

Mattsson, L.-G. & Tidström, A. (2015). Applying the principles of Yin-Yang to market dynamics. Marketing Theory, 15(3), 347–364.

Merton, R. K. (1957). The role-set: Problems in sociological theory. The British Journal of Sociology, 8(2), 106–120.

Mintzberg, H. & Waters, J. A. (1985). Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6(3), 257–272.

Morris, M. H., Koçak, A., & Özer, A. (2007). Coopetition as a small business strategy: Implications for performance. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 18(1), 35–55.

Park, B.-J., Srivastava, M. K., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Walking the tight rope of coopetition: Impact of competition and cooperation intensities and balance on firm innovation performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 210–221.

Padula, G. & Dagnino, G. B. (2007). Untangling the rise of coopetition – The intrusion of competition in a cooperative game structure. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 32–52.

Peng, T. J. A. & Bourne, M. (2009). The coexistence of competition and cooperation between networks: Implications from two Taiwanese healthcare networks. British Journal of Management, 20(3), 377–400.

Peteraf, M. (1993) The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 179–191.

Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy. New York: Free Press.

Raza-Ullah, T. (2017a) A Theory of Experienced Paradoxical Tension in Co-opetitive Alliances (Doctoral dissertation, Umeå Universitet).

Raza-Ullah, T. (2017b) The role of emotional ambivalence in coopetition alliances. Academy of Management Proceedings. Paper presented at 77th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Atlanta, August 4–8, 2017.

Raza-Ullah, T., Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2014). The coopetition paradox and tension in coopetition at multiple levels. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 189–198.

Richardson, G. B. (1972). The organisation of industry. The Economic Journal 82, 883–896.

Ritala, P. (2012). Coopetition strategy – When is it successful? Empirical evidence on innovation and market performance. British Journal of Management 23(3), 307–324.

Ritala, P. & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2009). What’s in it for me? Creating and appropriating value in innovation-related coopetition. Technovation, 29(12), 819–828.

Ritala, P. & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2013). Incremental and radical innovation in coopetition – The role of absorptive capacity and appropriability. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(1), 154–169.

Ritala, P., Golnam, A., & Wegmann, A. (2014). Coopetition-based business models: The case of Amazon.com. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 236–249.

Ritala, P. & Tidström, A. (2014). Untangling the value-creation and value-appropriation elements of coopetition strategy: A longitudinal analysis on the firm and relational levels. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30, 498–515.

Ross, W. T., Jr. & Robertson, D. C. (2007). Compound relationships between firms. Journal of Marketing, 71(3), 108–123.

Santos, F. M. & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2009). Constructing markets and shaping boundaries: Entrepreneurial power in nascent fields. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4): 643–671.

Séran, T., Pellegrin-Boucher, E., & Gurau, C. (2016). The management of coopetitive tensions within multi-unit organizations. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 31–41.

Shenkar, O. & Zeira, Y. (1992). Role conflict and role ambiguity of chief executive officers in international joint ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 55–75.

Smith, K. G., Grimm, C. M., Gannon, M. J., & Chen, M.-J. (1991). Organizational information processing, competitive responses, and performance in the U.S. domestic airline industry. Academy of Management Journal, 34(1), 60–85.

Tidström, A. (2014). Managing tensions in coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 261–271.

Volschenk, J., Ungerer, M., & Smit, E. (2016). Creation and appropriation of socio-environmental value in coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 109–118.

Whittington, R. (2006). Completing the practice turn in strategy research. Organization Studies, 27(5), 613–634.

Whittington, R. (2007). Strategy practice and strategy process: Family differences and the sociological eye. Organization Studies, 28(10), 1575–1586.

Yami, S., Castaldo, S., Dagnino, B., & Le Roy, F. (Eds) (2010). Introduction – Coopetition strategies: Towards a new form of inter-organizational dynamics? In Yami, S., Castaldo, S., Battista Dagnino, G., & Le Roy, F. (Eds), Coopetition – Winning strategies for the 21st century (pp. 1–16). Cheltenham; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Zhang, H. S., Shu, C. L., Jiang, X., & Malter, A. J. (2010). Managing knowledge for innovation: the role of cooperation, competition, and alliance nationality. Journal of International Marketing, 18(4), 74–94.