From strategizing coopetition to managing coopetition

Frédéric Le Roy, Anne-Sophie Fernandez, and Paul Chiambaretto

Introduction

Since the seminal book by Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996), coopetition has been the subject of an increasing amount of research. Publications on coopetition have been developed in numerous directions, making it difficult to form a complete synthesis (Bengtsson & Kock, 2014; Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, 2016; Czakon et al., 2014; Dorn et al., 2016; Yami et al., 2010). A common agreement among coopetition scholars is that coopetition can lead to higher levels of performance. As a consequence, coopetition is not only a research topic but also a strategy leading to a higher performance level than other strategies. Firms that implement coopetition strategies, i.e., strategizing coopetition, should expect higher performance than firms that implement purely cooperative or purely competitive strategies (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996; Lado et al., 1997).

The power of strategizing coopetition was first justified by game theory (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996). In the Prisoner Dilemma, although counter-intuitive, the cooperative solution is still the best strategy. Another explanation of the relevance of strategizing coopetition is rooted in the resource-based view theory (Bengtsson & Kock, 1999). As competitors have specific and highly complementary resources, combining those resources leads to a high-performance level. Other theoretical lenses can be used to justify the power of coopetition, including the network theory (Gnyawali & Madhavan, 2001), the resource dependence theory (Chiambaretto & Fernandez, 2016), and the dynamic capabilities theory (Estrada et al., 2016).

However, from other theoretical perspectives, the link between coopetition strategies and performance may appear to be null or negative. For instance, according to the transaction cost theory, high levels of uncertainty lead to opportunism. As coopetition is characterized by high uncertainty, especially in radical innovation projects, coopetitors could be damaged by high-technology plunders and unintended spillover. Therefore, they must avoid coopetition strategies (Arranz & Arroyabe, 2008). In the same way, the core competence theory considers that coopetitors are engaged in a learning race that could be damaging for the loser (Hamel, 1991; Khanna et al., 1998).

To sum up, coopetition can be a win-win strategy but also a win-lose strategy. Therefore, strategizing coopetition is not enough to reach high levels of performance. Coopetitors should pay attention to the risk of plunder in coopetition relationships. This risk of plunder does not mean that coopetitors must end or refuse a coopetitive relationship, but rather that they must manage it properly to create the conditions of successful coopetition. To make coopetition a successful strategy, the key point is management. Management is the “missing link” between coopetition and performance (Le Roy & Czakon, 2016). In this way, the core hypothesis defended in this chapter is that coopetition strategy can have a positive, null or negative impact on performance depending on the quality of the coopetition management implemented.

Strategizing coopetition: A double-edged sword

Coopetition is a dual and paradoxical relationship, simultaneously combining collaboration to create value and competition to capture a higher share of the value jointly created (Peng et al., 2012; Ritala, 2012). The paradox generated by the simultaneity of competition and cooperation represents the essence of the concept of coopetition (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000; Raza-Ullah, Bengtsson, & Kock, 2014).

The idea of combining collaboration and competition instead of opposing them is new in the literature. Economic theory considers that collaboration means collusion and is not good for welfare. Thus, efficient competition implies the absence of collaboration between competitors. Conversely, coopetition considers that collaboration between competitors could be good for the consumer if and only if this collaboration does not mean the end of competition. Collaboration between competitors is better than pure competition as long as the competitors continue to compete (Jorde & Teece, 1990).

This original point of view still requires theoretical justification and empirical evidence. Coopetition as a successful strategy for companies was first legitimated using game theory (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996). The well-known Prisoner Dilemma and the stag hunt game have been used to demonstrate the value of collaborating and competing at the same time (Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009). The coopetitive solution is counter-intuitive, and the actors will prefer a competitive solution. However, the coopetitive solution is the best one for them and leads to an optimal equilibrium.

Bengtsson & Kock (1999, 2000) built on the resource-based view (RBV) to justify the relevance of strategizing coopetition. The RBV explains why competitors are very good potential partners. Indeed, as they have similar and complementary resources, they can combine them to encourage economies of scale and learning (Gnyawali & Park, 2011; Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009). These arguments are consistent with the capabilities-based view (CBV) (Estrada et al., 2016). From the CBV perspective, the recombination of knowledge is critical to build dynamic capabilities (Helfat & Peteraf, 2003). More specifically, innovation capabilities emerge from the recombination of complementary knowledge (Kogut & Zander, 1992). For this reason, several scholars suggest that coopetition is one of the best ways to combine complementary knowledge and develop successful product innovation (Gnyawali & Park, 2009, 2011; Quintana-García & Benavides-Velasco, 2004; Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009).

Network theory provides arguments that align with the RBV and the CBV. It recommends that firms in the same industry, with different but complementary resources and capabilities, should collaborate deeply. Indeed, by collaborating not only at the dyadic level but also at the industry level, they can benefit from a broader knowledge base and become more performant (Gnyawali & Madhavan, 2001; Gnyawali et al., 2006). According to this approach, the challenge for a firm is to become the central actor in the coopetitive network (Sanou et al., 2016). The best strategy consists of being highly cooperative to become central in the network. This central position will give power to the focal firm, which will be able to become more aggressive and therefore more profitable. Following this approach, coopetition strategy is better than either a pure competition or a pure cooperation strategy (Le Roy & Sanou, 2014; Robert et al., 2018).

Game theory, RBV, CBV and network theory all lead to an optimistic view of coopetition, which becomes a better strategy than pure competition or pure collaboration. However, this optimistic view of coopetition is inconsistent with research built on transaction cost theory (TCT) (Arranz & Arroyabe, 2008; Park & Russo, 1996). The TCT considers that coopetition creates a high level of uncertainty, giving actors the incentive to behave opportunistically. Therefore, coopetitors cannot develop trustworthy relationships and cannot fully collaborate. According to this approach, coopetition is a particular type of cooperation in which trust is difficult to develop (Arranz & Arroyabe, 2008; Czakon & Czernek, 2016). As both coopetitors are aware of opportunistic risks, they are discouraged from pooling their core knowledge. Cooperation with competitors exposes the firm to undesired spillover that can be used by the coopetitor. Thus, firms are reluctant to collaborate openly, and it is difficult to develop the necessary level of trust for the success of common projects.

In the same way, the core competence theory considers that coopetition is a risky strategy in which coopetitors are involved in a learning race (Hamel, 1991). Cooperating with a competitor involves sharing knowledge, skills and resources. Without this sharing, the collaboration is useless. However, because the coopetitor is an opportunist by nature, it might use this knowledge for its own individual benefit rather than for common benefits. If there is a significant asymmetry of learning, coopetition becomes a win-lose strategy; i.e., one coopetitor is winning at the expense of the other (Baumard, 2010; Hamel et al., 1989).

The TCT and core competence theory lead to a pessimistic view of coopetition. On the one hand, because collaboration is not really possible between competitors, coopetition cannot have a positive effect. On the other hand, because of the high risks of opportunism, coopetition can be very damaging. Therefore, the coopetition effect should be null in the best situation and negative in the worst situation. Coopetition strategies should thus be avoided as much as possible.

To sum up, depending on the perspective adopted, strategizing coopetition can lead to different outcomes. According to game theory, the RBV, the CBV and network theory, the best partner is a competitor and coopetition is a powerful win-win strategy, even better than purely collaborative or purely competitive strategies. Conversely, the TCT and the core competence theory consider coopetition to be an inefficient, and in some extreme cases a potentially damaging, strategy. Coopetition is conceptualized as a win-lose strategy that firms should avoid.

Strategizing coopetition in and of itself is not sufficient to create a high level of performance. Thus, the decision for any firm is not whether to strategize coopetition, but rather how to successfully strategize coopetition. Our main idea in this chapter is that managing coopetition is the principal success factor in strategizing coopetition.

From strategizing coopetition to coopetitive tensions

By simultaneously combining two opposite behaviors (collaboration and competition), coopetition can be understood as a paradoxical strategy (De Rond & Bouchiki, 2004; Raza-Ullah et al., 2014; Smith & Lewis, 2011). The combination of collaborative and competitive behaviours contributes to the emergence of tensions at different levels: inter-organizational, intra-organizational and inter-individual (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000; Czakon, 2010; Fernandez et al., 2014; Le Roy & Fernandez, 2015; Luo et al., 2006; Padula & Dagnino, 2007). Tensions between cooperation and competition are driven by the conflict between generating shared benefits and capturing private benefits (Czakon, 2010; Khanna et al., 1998; Ritala & Tidström, 2014).

At the inter-organizational level, tension initially arises out of the dilemma between the creation of common value and the appropriation of private value (Ritala & Tidström, 2014; Gnyawali et al., 2016). After the knowledge creation phase, tensions arise between the distributive and integrative elements of knowledge appropriation (Oliver, 2004). Another type of coopetitive tension occurs based on the risks of transferring confidential information and the risks of technological imitation. Partners pool strategic resources to achieve their goals (Gnyawali & Park, 2009); however, at the same time, they must protect their core competences to remain strong competitors.

At the intra-organizational level, i.e., at the project level, coopetitive tensions are even more important because the implementation of coopetition strategies requires employees from competing parent firms to work together (Fernandez et al., 2014; Gnyawali & Park, 2011). The project level is thus crucial to an understanding of how intra-organizational tensions are managed.

One critical intra-organizational tension arises from the dilemma between sharing and protecting information (Fernandez et al., 2014; Fernandez & Chiambaretto, 2016; Levy et al., 2003). Partners in an alliance can easily learn from one another, especially if they are competitors (Baruch & Lin, 2012; Estrada et al., 2016; Khanna et al., 1998). Although partners must share information and knowledge to achieve the common goal of the collaboration (Gnyawali & Park, 2011; Mention, 2011), each partner must also protect the strategic core of its knowledge from its competitor because partners that operate in the same industry must develop unique skills (Baumard, 2010; Ritala et al., 2015). Information that is shared within a common collaborative project could potentially be used in a different market in which the partners compete. The competing partner could benefit by appropriating the shared information (Hurmelinna-Laukkanen & Olander, 2014).

In a coopetitive project in which partners could utilize shared information for their own purposes, the risk of opportunism and appropriation is particularly high (Baruch & Lin, 2012; Bouncken & Kraus, 2013; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen & Olander, 2014; Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009, 2013). Fernandez and Chiambaretto (2016) defined this coopetitive tension related to information as “the difference between a firm’s need to share information to ensure the success of the common project and its need to limit information sharing to avoid informational spillovers into other markets.”

Another critical tension occurs among the different business units (Luo et al., 2006). Managers involved in internal activities compete with colleagues involved in coopetitive activities to obtain human, technological and financial resources from the parent firm (Tsai, 2002).

At the inter-individual level, coopetitive tensions appear for a variety of reasons. Individuals face the dilemma of choosing between a single strategy and collaboration. In a purely collaborative project, a common identity is gradually created as individuals from different companies work together over time. In a coopetitive project, two firms’ identities are mixed without being merged. The psychological equilibrium of the individuals involved can be disturbed (Gnyawali et al., 2008; Gnyawali et al., 2016; Raza-Ullah et al., 2014). Another source of tension relates to employees involved in activities developed with competitors. These employees face tensions when a current competitor becomes a partner or when a partner becomes a competitor (Gnyawali and Park, 2011; Raza-Ullah et al., 2014).

In a nutshell, there are substantial tensions in coopetition due to the competitive dimension of the coopetitive relationship. These tensions can be considered very damaging for the quality of the collaboration between coopetitors. They can create mistrust, mutual negative effects and unsolvable conflicts between coopetitors. However, they can also be considered the real source of coopetition success because they encourage coopetitors to find a way to transcend their paradoxical coopetitive relationship.

In this way of thinking, coopetition provides coopetitors with additional resources and competitive challenges to best use these resources. Coopetitive tensions stimulate firms and individuals to give the best of themselves and to go faster and further than pure competition or pure collaboration. Therefore, coopetitive tensions are considered more as a strength than a weakness of coopetition. In this perspective, reducing coopetitive tensions will lead to a decrease in competition and thus to an end of coopetition (Park et al., 2014). Consequently, companies must not attempt to reduce or eliminate these tensions but should instead manage them efficiently (Le Roy & Czakon, 2016). Instead of reducing competition or collaboration, firms should rather maintain a balance (Clarke-Hill et al., 2003). Relevant managerial tools are then required to reach and preserve this balance (Bengtsson et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2007; Chen, 2008).

When coopetitive tensions require the management of coopetition

Coopetition paradox belongs to a larger stream of literature dedicated to the management of paradoxes (Lewis, 2000; Smith & Lewis, 2011). In this literature, two contradictory approaches to managing paradoxical tensions are frequently debated. The first approach recommends paradox resolution by splitting opposite forces (Poole & Van de Ven, 1989). The second approach suggests that separation creates vicious cycles. Therefore, scholars in this second approach recommend accepting and transcending the paradox at both the individual and the organizational levels. Once the paradox is accepted, a resolution strategy should be implemented (Smith & Lewis, 2011; Smith & Tushman, 2005).

According to the paradox resolution approach, several coopetition scholars consider that the management of collaboration and the management of competition should be split to manage coopetitive tensions (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000; Dowling et al., 1996; Herzog, 2010). The separation can be functional or spatial. For instance, coopetitors can cooperate on one dimension of the value chain (i.e., R&D) while competing on another dimension (i.e., marketing activities), or coopetitors can cooperate in a given market while competing in another one.

However, other scholars have noted the limitations of this principle and recommended a more integrative approach (Chen, 2008; Oshri & Weeber, 2006). The main problem with the separation principle is the creation of internal conflict in the company between people dedicated to competition and people dedicated to collaboration (Pellegrin-Boucher et al., forthcoming). In line with the paradox acceptance approach, the integration principle requires individuals to understand their roles in a paradoxical context and to behave accordingly, following both logics simultaneously. Thus, the challenge for managers is to transcend the paradox, to simultaneously manage collaboration and competition, and to thereby optimize the benefits of coopetition (Luo, 2007).

The separation principle and the integration principle belong to two different and opposite schools of thought. In the first one, the basic idea is that individuals cannot integrate the paradox; therefore, the separation principle is needed and the only one to implement coopetition strategy. In the second school of thought, the separation principle is considered a negation of the paradoxical nature of coopetition. Companies can successfully manage coopetition if and only if individuals can develop a coopetitive mindset.

A third school of thought attempts to combine these two opposite approaches. Instead of opposing the separation and the integration principles, scholars suggest that both principles should be used simultaneously to efficiently manage coopetitive tensions (Fernandez et al., 2014; Fernandez & Chiambaretto, 2016; Séran et al., 2016). The separation principle is required at the organizational level. Competition and cooperation should be split between different levels of the value chain or between different products or markets. This separation is necessary to define a dominant role, either collaborative or competitive, for each activity within the firm. However, this single separation is not sufficient to efficiently manage multiple coopetitive tensions because they generate additional tensions within the organization at the individual level.

At the individual level, the integration of the coopetition paradox is necessary to manage coopetitive tensions. Indeed, the separation principle creates internal tensions within firms between those employees in charge of collaboration and those in charge of competition. The only way to control these tensions is to encourage people to understand the role of each employee in a coopetitive setting. The understanding of the coopetition paradox limits the tensions within the firm and allows individuals to adopt simultaneous cooperative and competitive behaviors with their coopetitors. The integration of the coopetition paradox by individuals is facilitated by the joint implementation of formal coordination (procedures, regular meetings, etc.) and informal coordination (social networks, social interaction, trust, etc.) (Séran et al., 2016).

The separation and the integration principles are complementary. Each principle has virtues and limits, and the combination of both principles compensates for their limits. For instance, Fernandez and Chiambaretto (2016) showed empirically how to combine both principles to manage tensions related to information at the project level. According to the separation principle, managers use formal control mechanisms, i.e., the information system, to share only the critical information required to achieve a project goal and to protect the non-critical information. Simultaneously, managers use informal control mechanisms to differentiate appropriable critical information from non-appropriable critical information, to transform one into the other. Such abilities developed by managers rely on a cognitive integration of the coopetition paradox. Thus, efficiently managing tensions related to information requires a combination of both the separation and integration principles.

Other empirical evidence is provided by Séran and colleagues (2016) in the banking sector. In this sector, coopetition relationships exist within multi-unit organizations, such as Crédit Agricole and Banque Populaire Caisse d’Epargne. Coopetitive tensions appear at the intra-organizational and inter-individual levels. Authors have shown that these tensions are efficiently managed by the implementation of a separation principle—independent banks, distinct brands and staff—and the implementation of an integration principle based on formal and informal coordination.

Opening the black box: Managing coopetition on a daily basis

The separation and integration principles are used together but at different levels. The separation principle is associated with the organizational design of the company, or at least within the business unit. Within this unit, certain projects are conducted with rivals and other projects are performed in pure competition with these rivals. The integration principle pertains to the individual level. People are more or less able to integrate the paradox of coopetition and adopt both a balanced mindset and behavior.

Between the organizational-design level and the individual level, an intermediary level is the working group dedicated to the common project with the competitor. At this working-group level, people from competing firms work together on a daily basis, sharing their knowledge, know-how, resources and competencies. Therefore, at this level, the value of coopetition is created, but the risks of plunder are at their highest. Consequently, this level is critical for coopetition success.

How should firms manage coopetition at this working-group level? Two previous studies are dedicated to this question. The first focuses on technology coopetition (Le Roy & Fernandez, 2015) and the second focuses on selling coopetition (Pellegrin-Boucher et al., 2018). Both each identify an additional principle: the co-management principle for technology coopetition and the arbitration principle for selling coopetition.

First, the co-management principle is required for technology coopetition (Le Roy & Fernandez, 2015). This co-management principle is implemented into the common team created by the coopetitors: the coopetitive project team. The co-management principle is based on peer logic. The coopetitive project team is managed via a dual managerial structure. Team members from competing firms are pooled and work together on a daily basis. Parent firms adopt an organizational design in which they equally share the decision-making process, thus managing the risk of opportunism. Therefore, power is balanced and symmetric in a horizontal collaboration. Although this redundancy in managerial functions may appear to be a waste of resources, it is essential to develop trust and to encourage necessary knowledge-sharing among team members (Fernandez et al., 2018; Le Roy & Fernandez, 2015).

Second, the arbitration principle is needed for selling coopetition (Pellegrin-Boucher et al., forthcoming). Selling coopetition relies on alliance managers, whose mission is to win calls for tenders by collaborating with competitors. This mission creates internal tensions between alliance managers and sales managers who may also apply for these calls for tenders alone. These tensions cannot be resolved by the separation and integration principles, and thus the hierarchy must rely on arbitration to address these internal conflicts.

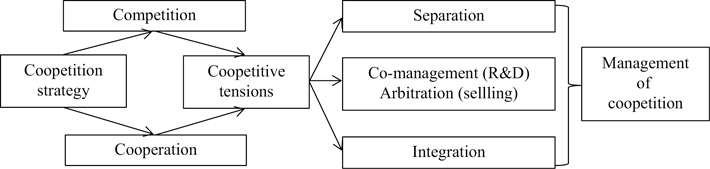

Based on these previous studies, we propose a multi-level framework to analyze the management of coopetition strategies (Figure 3.1). The separation principle is relevant to managing coopetitive tensions at the organizational level, and the integration principle is appropriate for managing coopetitive tensions at the individual level. At the project level (R&D or sales project), the co-management principle is relevant in technology coopetition, whereas the arbitration principle is better suited for selling coopetition. These principles should be simultaneously combined and implemented to efficiently manage coopetitive tensions.

The importance of the combination of these principles was initially found in the space industry for technology coopetition (Le Roy & Fernandez, 2015) and in the ICT industry for selling coopetition (Pellegrin-Boucher et al., 2018). These high-tech industries are characterized by high levels of R&D costs, high levels of risk, high levels of knowledge, high market uncertainty, etc. All companies evolving in high-tech industries face similar issues. Thus, our framework could guide these companies to adopt coopetition strategies and to succeed in such environments. Further studies could confirm this assumption in other high-tech or low-tech industries. From this perspective, coopetition management is a new and stimulating research topic with significant potential for researchers and practitioners.

Conclusion and research perspectives

In this chapter, we indicate that coopetition strategy can be a double-edged sword, representing either a win-win or a win-lose strategy. The positive or negative effect of strategizing coopetition clearly depends on the management of coopetition. Because coopetition simultaneously combines two contradictory logics, it creates tensions at several different levels: inter-organizational, intra-organizational and inter-individual. These tensions must be efficiently managed so that firms can benefit from coopetition. The question of relevant principles for managing coopetition is therefore the key question in coopetition research.

This question remains an open one and, thus far, three schools of thought can be distinguished. The first is based on the separation principle, the second on the integration principle and the third on a combination of the separation and integration principles. In this third school, some researchers explore more deeply at the working-group level and identify two other principles depending on the coopetition type: the co-management principle for technology coopetition and the arbitration principle for selling coopetition. Overall, successfully managing coopetition requires a combination of complementary principles: the separation principle at the business unit level; the co-management principle (for technology coopetition) or the arbitration principle (for selling coopetition) at the working-group level; and the integration principle at the individual level.

Coopetition remains more of an open field of research than a closed one. Research on managing coopetition remains scarce, and further research is needed in other industries to discuss the relevance of the preliminary results presented in this chapter. Is our framework relevant for companies in low-tech industries or for SMEs? Understanding and analyzing the management tools used in coopetition strategy in these circumstances is crucial.

As highlighted in this chapter, previous research remained focused on management principles. Once these management principles have been identified, it is necessary to delve further into the black box of coopetition. For instance, researchers should explore organizational designs used by firms at the working-group level. Le Roy and Fernandez (2015) identified the coopetitive project team. Do companies use organizational designs other than coopetitive project teams and why? One recent contribution suggests that a company can use another organizational design known as the separated-project team, based on the risks, costs and innovativeness of the project (Fernandez et al., 2018). Additional research is needed to reveal other organizational designs and to understand their drivers and implications. In particular, we must examine how companies manage their coopetition strategy when the coopetitive project involves more than two coopetitors.

Future studies should also focus on certain managerial aspects of coopetitive projects. For instance, the information systems used to achieve coopetitive projects represent an exciting research perspective. The pioneering work of Fernandez and Chiambaretto (2016) requires additional research to better understand how information is shared and protected by coopetitors. We also must further investigate the management control of coopetitive projects. Preliminary research shows that management control creates specific issues that can be more thoroughly investigated (Grafton & Mundy, 2017). The marketing management of coopetition represents another fascinating research perspective. Pellegrin-Boucher et al. (2018) suggest that managing the selling of coopetition involves a specific principle known as arbitration. Futures studies could examine the management of selling coopetition as well as marketing, distribution or branding coopetition (Chiambaretto et al., 2016). Managing coopetition in supply chains, purchasing and logistics is an entirely open question that should also be specifically examined.

To sum up, researchers have taken the first steps towards a broader understanding of coopetition management. Given that coopetition management is the key success factor in strategizing coopetition, further research on this topic is necessary.

References

Arranz, N. & Arroyabe, J. C. (2008). The choice of partners in R&D cooperation: An empirical analysis of Spanish firms. Technovation, 28, 88–100.

Baruch, Y. & Lin, C.-P. (2012). All for one, one for all: Coopetition and virtual team performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 79(6), 1155–1168.

Baumard, P. (2010). Learning in Coopetitive Environments. In Yami, S., Castaldo, S., Dagnino, G. B., & Le Roy F. (Eds), Coopetition: winning strategies for the 21st century. Cheltenham; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2000). “Coopetition” in business networks—to cooperate and compete simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(5), 411–426.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2014). Coopetition—quo vadis? Past accomplishments and future challenges. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 180–188.

Bengtsson, M. & Raza-Ullah, T. (2016). A systematic review of research on coopetition: Towards a multilevel understanding. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 23–39.

Bengtsson, M., Raza-Ullah, T., & Vanyushyn, V. (2016). The coopetition paradox and tension: The moderating role of coopetition capability. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 19–30.

Bonel, E. & Rocco, E. (2007). Coopeting to survive; surviving coopetition. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 70–96.

Bouncken, R. B. & Kraus, S. (2013). Innovation in knowledge-intensive industries: The double-edged sword of coopetition. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 2060–2070.

Brandenburger, A. M. & Nalebuff, B. J. (1996). Co-Opetition: A Revolutionary Mindset That Redefines Competition and Cooperation. Doubleday: New York, 121.

Chen, M.-J. (2008). Reconceptualizing the competition-cooperation relationship: a transparadox perspective. Journal of Management Inquiry, 17(4), 288–304.

Chen, M.-J., Su, K.-H., & Tsai, W. (2007). Competitive tension: The awareness-motivation-capability perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 101–118.

Chan, S. H., Kensinger, J. W., Keown, A. J., & Martin, J. D. (1997). Do strategic alliances create value? Journal of Financial Economics, 46, 199–221.

Chiambaretto P., Calin G., & Le Roy F. (2016). Coopetitive branding: Definition, typology, benefit and risks. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 86–96.

Chiambaretto, P. & Fernandez, A.-S. (2016). The evolution of coopetitive and collaborative alliances in an alliance portfolio: The Air France case. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 75–85.

Clarke-Hill, C., Li, H., & Davies, B. (2003). The paradox of co-operation and competition in strategic alliances: towards a multi-paradigm approach. Management Research News, 26(1), 1–20.

Czakon, W. & Czernek, K. (2016). The role of trust-building mechanisms in entering into network coopetition: The case of tourism networks in Poland. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 64–74.

Czakon, W., Fernandez, A-S., & Minà, A. (2014). From paradox to practice: the rise of coopetition strategies. International Journal of Business Environment, 6(1), 1–10.

De Rond, M. & Bouchikhi, H. (2004). On the dialectics of strategic alliances. Organization Science, 15(1), 56–69.

Dorn, S., Schweiger, B., & Albers, S. (2016). Levels, phases and themes of coopetition: A systematic literature review and research agenda. European Management Journal, 34(5), 484–500.

Dowling, M. J., Roering, W. D., Carlin, B. A., & Wisnieski, J. (1996). Multifaceted relationships under coopetition description and theory. Journal of Management Inquiry, 5(2), 155–167.

Estrada, I., Faems, D., & de Faria, P. (2016). Coopetition and product innovation performance: The role of internal knowledge sharing mechanisms and formal knowledge protection mechanisms. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 56–65.

Fernandez, A.-S. & Chiambaretto, P. (2016). Managing tensions related to information in coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 66–76.

Fernandez, A.-S., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Sources and management of tension in co-opetition case evidence from telecommunications satellites manufacturing in Europe. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 222–235.

Fernandez A.-S., Le Roy F., Chiambaretto P. (2018). Implementing the right project structure to achieve coopetitive innovation projects. Long Range Planning, 51(2), 384–405.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Madhavan, R. (2001). Networks and competitive dynamics: A structural embeddedness perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(3), 431–445.

Gnyawali, D. R., He, J., & Madhavan, R. (2006). Impact of co-opetition on firm competitive behavior: An empirical examination. Journal of Management, 32, 507–530.

Gnyawali, D. R., He, J., & Madhavan, R. (2008). Co-opetition. Promises and challenges. In 21st Century Management: A Reference Handbook, Wankel, C. (Ed). London: Sage Publications, 386–398.

Gnyawali, D. R., Madhavan, R., He, J., & Bengtsson M. (2016). The competition–cooperation paradox in inter-firm relationships: A conceptual framework. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 7–18.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Park, B.-J. (2009). Co-opetition and technological innovation in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: a multilevel conceptual model. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(3), 308–330.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Park, B.-J. (2011). Co-opetition between giants: Collaboration with competitors for technological innovation. Research Policy, 40(5), 650–663.

Hamel, G. (1991). Competition for competence and inter-partner learning within international strategic alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 1, 83–103.

Hamel, G., Doz, Y. L., & Prahalad, C. K. (1989). Collaborate with your competitors – and win. Harvard Business Review, 67(1), 133–139.

Helfat, C. E. & Peteraf, M. A. (2003). The dynamic resource-based view: capability lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal, 24, 997–1010.

Herzog, T. (2010). Strategic management of coopetitive relationships in CoPS-related industries. In Coopetition: winning strategies for the 21st century, Yami S., Castaldo S., Dagnino G. B., Le Roy F. (Eds). Cheltenham; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. & Olander, H. (2014). Coping with rivals’ absorptive capacity in innovation activities. Technovation, 34(1), 3–11.

Grafton J. & Mundy J. (2017), Relational contracting and the myth of trust: Control in a co-opetitive setting. Management Accounting Research, 36, 24–4.

Jorde, T. M. & Teece, D. J. (1990). Innovation and cooperation: implications for competition and antitrust. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(3), 75–96.

Khanna, T., Gulati, R., & Nohria, N. (1998). The dynamics of learning alliances: competition, cooperation, and relative scope. Strategic Management Journal, 19(3), 193–210.

Kim, J. & Parkhe, A. (2009). Competing and cooperating similarity in global strategic alliances: an exploratory examination. British Journal of Management, 20(3), 363–376.

Kogut, B. & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3, 383–397.

Lado, A. A., Boyd, N. G., & Hanlon, S. C. (1997). Competition, cooperation, and the search for economic rents: A syncretic model. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 110–141.

Le Roy, F. & Czakon, W. (2016). Managing coopetition: the missing link between strategy and performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 3–6.

Le Roy, F. & Sanou, F. H. (2014). Does Coopetition Strategy improve Market Performance: an Empirical Study in Mobile Phone Industry. Journal of Economics and Management, 17, 63–94.

Le Roy, F. & Fernandez, A.-S. (2015). Managing coopetitive tensions at the working-group level: the rise of the coopetitive project team. British Journal of Management, 26(4), 671–688.

Levy, M., Loebbecke, C., & Maier, R. (2003). SMEs, co-opetition and knowledge sharing: the role of information systems. European Journal of Information Systems, 12(1), 3–17.

Lewis, M. W. (2000). Exploring paradox: Toward a more comprehensive guide. Academy of Management Review, 25, 760–776.

Luo, X., Rindfleisch, A., & Tse, D. K. (2007). Working with rivals: the impact of competitor alliances on financial performance. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(1), 73–83.

Luo, X., Slotegraaf, R. J., & Pan, X. (2006). Cross-functional “coopetition”: The simultaneous role of cooperation and competition within firms. Journal of Marketing, 70(2), 67–80.

Mention, A.-L. (2011). Co-operation and co-opetition as open innovation practices in the service sector: Which influence on innovation novelty? Technovation, 31(1), 44–53.

Oshri, I. & Weeber, C. (2006). Cooperation and competition standards-setting activities in the digitization era: The case of wireless information devices. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 18(2), 265–283.

Padula, G. & Dagnino, G. (2007). Untangling the rise of coopetition: The intrusion of competition in a cooperative game structure. International Studies of Management and Organization, 37(2), 32–52.

Park, B.-J. (Robert), Srivastava, M. K., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Walking the tight rope of coopetition: Impact of competition and cooperation intensities and balance on firm innovation performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 210–221.

Pellegrin-Boucher, E., Le Roy, F., & Gurău, C. (2018). Managing Selling Coopetition: a case study of the ERP industry. European Management Review, 15(1), 37–56.

Pellegrin-Boucher, E., Le Roy, F., & Gurău, C. (2013). Coopetitive strategies in the ICT sector: typology and stability. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 25(1), 71–89.

Peng, T.-J. A., Pike, S., Yang, J.C.-H., & Roos, G. (2012). Is Cooperation with competitors a good Idea? An example in practice. British Journal of Management, 23(4), 532–560.

Poole, M. S. & Van de Ven, A. H. (1989). Using paradox to build management and organization theories. Academy of Management Review, 14, 562–578.

Quintana-García, C. & Benavides-Velasco, C. A. (2004). Cooperation, competition, and innovative capability: a panel data of European dedicated biotechnology firms. Technovation, 24(12), 927–938.

Raza-Ullah, T., Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2014). The coopetition paradox and tension in coopetition at multiple levels. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 189–198.

Ritala, P. (2012). Coopetition Strategy – When is it successful? Empirical evidence on innovation and market performance. British Journal of Management, 23(3), 307–324.

Ritala, P. & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2009). What is in it for me? Creating and appropriating value in innovation-related coopetition. Technovation, 29, 819–882

Ritala, P. & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2013). Incremental and radical innovation in Coopetition—The role of absorptive capacity and appropriability. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(1), 154–169.

Ritala, P. & Tidström, A. (2014). Untangling the value-creation and value-appropriation elements of coopetition strategy: A longitudinal analysis on the firm and relational levels. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(4), 498–515.

Ritala, P., Olander, H., Michailova, S., & Husted, K. (2015). Knowledge sharing, knowledge leaking and relative innovation performance: An empirical study. Technovation, 35, 22–31.

Robert, M., Chiambaretto, P., Mira, B., & Le Roy, F. (2018). Better, Faster, Stronger: The impact of market-oriented coopetition on product commercial performance. M@n@gement, 21, 574–610.

Sanou, F. H., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2016). How does centrality in coopetition networks matter? An empirical investigation in the mobile telephone industry. British Journal of Management, 27, 143–160.

Séran, T., Pellegrin-Boucher, E., & Gurau, C. (2016). The management of coopetitive tensions within multi-unit organizations. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 31–41.

Smith, W. K. & Lewis, M. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: a dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381–403.

Tsai, W. (2002). Social structure of “coopetition” within a multiunit organization: Coordination, competition, and intraorganizational knowledge sharing. Organization Science, 13(2), 179–190.

Yami, S., Castaldo, S., Dagnino G. B., & Le Roy, F. (2010). Coopetition winning strategies for the 21st century. Cheltenham; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.