Introduction

If collaboration between two rivals can dramatically improve their market position (Gnyawali & Park, 2009) and, if carefully managed, contribute to increasing the respective firms’ performance (Fernandez et al., 2014), then collaboration between three and more partners unlocks the true potential of coopetition. The more actors involved in creating value, the more value that can be generated and appropriated. This chapter takes coopetition thinking back to its origins, rooted in the value net concept, which brings in various actors and establishes collaborative relationships along with competition among them (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1997). As opposed to a dyad, where tensions and paradoxes attract researchers’ attention (Tidström, 2009), it is value creation potential that remains at the core of network coopetition. In order to unlock it, firms need to understand the value net scope, the nature of relationships linking actors together and the strategic challenges related to network coopetition entry, as well as common value generation and capture.

The value network and coopetition

Coopetition is an intriguing concept both for managers and academics, because it is difficult to conceive a simultaneously friendly and rivalrous relationship with a single partner. Significant attention has been attributed to this challenge, by conceptually positioning coopetition as one of four possible inter-firm relationships (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000), along with competition, collaboration and coexistence. This early proposition locates collaboration on some value chain activities, while competition takes place on others, so that the two opposing relational logics are separated. To date, theoretical contributions and empirical studies have provided solid grounds for understanding the paradoxical nature of coopetition (Czakon et al., 2014).

However, the introduction of coopetition into management literature has adopted a value net level of analysis (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1997). Scholars have recently underlined the need to shift beyond dyadic coopetition, in order to tap into the network level of analysis in coopetition studies (Gnywali et al., 2006; Pathak et al., 2014; Sanou et al., 2016; Wilhelm, 2011). Network coopetition refers to multiple actors’ interactions involving various firms, covering the value net. It involves rivals, suppliers, customers and complementors in a joint effort to increase “the business pie,” offering more value for appropriation by each individual actor (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1997). Collaboration rather than competition is in the best interests of each actor, as game theoretical models suggest (Okura, 2007). The baseline argument of coopetition is therefore connected more with the network level of analysis (Pathak et al., 2014), the collective effort to create value and the dynamics of value capture, rather than solely the paradoxical interplay of coopetition and collaboration at dyadic level.

Yet, coopetition research has seldom taken the network level of analysis. The inherent complexity of network coopetition requires a precise delimitation in order to adequately address the actors, structure and dynamics under scrutiny (Figure 4.1). Scholars have used two different concepts: the coopetitive network (Gnyawali et al., 2006), and the coopetition-in-supply network (Wilhelm, 2011).

A coopetitive network is a particular type of network within an industry, unique by the consequences of simultaneous collaboration and competition between its members (Sanou et al., 2016). Different from collaborative networks, coopetitive networks: entail the existence of competitive relationships among actors; are based on business needs rather than trust; and provide access to rival firms’ resources. This unique type of network has been found to have emerged in the steel (Gnyawali et al., 2006) and mobile telecommunication (Sanou et al., 2016) industries.

Supply networks incorporate sets of individual and connected supply chains with links among them (Wilhelm, 2011). Inter-firm relations are established both vertically and horizontally. They involve pure collaboration, competition, co-existence or coopetition. The sourcing strategies of a focal firm create tensions at the horizontal level between respective suppliers. Tensions inherent to coopetition (Fernandez et al., 2014) manifest themselves in vertical relationships differently from horizontal relationships, but impact each other.

Those two concepts have been introduced for specific purposes and therefore limit the scope of attention to emergent networks focused on resource access, or to sourcing network management (Figure 4.1). Interestingly the original concept of a value net is broader, both by the type of actors involved and by the general-purpose statement that is value creation. The inclusion of complementors into the value net goes beyond the scope of supply chain logic. Similarly, value creation can be decided by the customer, who assembles the final composition of offerings available in the value net; therefore, access to resources may reveal itself to be secondary to resource pooling through gathering relevant partners in a joint value creation process.

This chapter addresses distinct phenomena and challenges typical to network coopetition. If it is a clearly intentional strategy to collaborate with a specific actor, does network coopetition display more deliberate or more consequential features (Czakon, 2009)? How do firms nested in interdependent relationships choose their relationship-mix, resulting in the adoption of various coopetition strategies (Czakon & Rogalski, 2014)? Why do some firms enter network coopetition, while others do not (Czakon & Czernek, 2016)? What benefits does coopetition offer to all involved firms, beyond satisfying their individual needs (Czakon et al., 2016)?

Deliberate or emergent? Coopetition patterns within networks

Deliberate strategies have their corresponding alter egos, with several possible strategies in between. Emergence is seen as “patterns realized in spite of or in the absence of intentions” (Mintzberg & Waters, 1985), and encapsulates all behaviors, processes and resource allocations that have not been previously planned in a rational process (Figure 4.2.). Emergence captures the gap between what has been planned and what is actually being done, opening ways to a more dynamic understanding of strategy, where various factors interact in a long-term process. Coopetition strategies have been depicted as normative and deliberate (Le Roy & Czakon, 2016), similarly to competition and cooperation strategies, which are usually viewed as intentional, with generic options identified by scholars. Yet, their interplay in coopetition may instead be seen as an emergent process (Mariani, 2007). In this section, an overview of studies tackling network coopetition in banking, airlines and tourism sheds light on the various factors impacting coopetition adoption in order to better understand this dynamic process.

A Polish banking franchise system study, focused on a medium-sized retail bank and its 460 franchisees, unveiled the emergence of competition between the franchisees and the franchisor (Czakon, 2009). The franchise network is centralized around the focal bank, and exploits a portfolio of standardized dyadic relationships designed by: 1) specifying goals; 2) defining the scope of respective actors’ activities; 3) setting a governance structure; and 4) declaring partners’ commitment specification.

Interfirm relationships are designed to last, so over time their assessment may lead to various changes (Ring & Van de Ven, 1994). When assessment reveals unsatisfactory results or processes, mutual adjustments are needed, otherwise the relationship is dissolved either by consensual decision or unilaterally. Franchisees were found to expect a fairer share of the business pie, and to demand collaboration process modifications, while the franchisor took a power position and demonstrated low flexibility by sticking to the initial agreement (Czakon, 2009). Consequently, three types of franchisee reactions have been identified: 1) acceptance of the initial conditions; 2) unilateral contract dissolution; and 3) unilateral rent seeking within and beyond the franchise network. Hence, competitive behaviors emerged within the collaborative setting of a franchise network.

A different process of network coopetition development, as a response to changes in the dominant strategies adopted by various firms, has been identified in a long-term study of the airlines industry (Czakon & Dana, 2013). Distinct phases in global airline industry development since deregulation in the late 1970s triggering major shakeouts of existing market rules have been identified (Czakon & Dana, 2013). Firms have adopted dyadic coopetition strategies as soon as market regulation has been relaxed. Next, dyadic coopetition portfolios appeared, mostly focused on marketing and sales. Finally, network alliance competition in the industry followed, competitive both towards other alliances and within the respective networks. Hence, coopetition has emerged from a path of innovation-imitation-covergence across the airline industry. After an innovative model is successfully implemented, actors compete for the best share in the value created. In sum, a collective effort to shape the industry so that it creates more value than before has driven network coopetition.

Network coopetition can also be adopted in a more deliberate process, organized by a leading actor with the consensual agreement of others. For instance, in tourism destinations, marketing coopetition may prove beneficial for involved actors by increasing the competitive advantage against other destinations (Wang & Krakover, 2008). Various interests are nested in a tourism destination, and firms are interdependent to a large extent. Collective problems require collective solutions, including cooperative marketing initiatives, public-private partnerships, intergovernmental coalitions and inter-sector planning (Selin & Chavez, 1995). While industry specific factors foster coopetition in tourism, destinations vary in the degree of cooperation between rivals. Two opposing logics of interaction have been identified: competition where tourist firms try to maximize their individual benefits without engaging in collective action, and collaboration where individual tourism businesses participate in collective action to achieve common goals (Wang & Krakover, 2008).

The development of a network coopetition project requires coordinated action. Dominated networks have been identified in which one central actor establishes a number of bilateral relationships with other, usually smaller companies (von Fredrichs Grängsjö, 2003). However, “equal partners’ networks” formed by small and medium enterprises without a bigger focal firm are also equipped to cope with the strategic challenges local firms face, without the intervention of a dominant player (Della Corte & Aria, 2016). Starting with issue identification (Selin & Chavez, 1995), through network formation (Czakon & Czernek, 2016), to operations coordination (Mariani, 2016), the role of a network leader implementing a network design is crucial.

Relationship-mix: Coopetition strategies in networks

Coopetition can be a deliberate choice for some firms, while being an emerging strategy for other players of the same market (Czakon & Rogalski, 2014). The rationale for engaging in collaboration with rivals may therefore emerge from exogenous pressures such as customer demand or regulatory obligations, or inversely be driven by individual firms’ strategies. Extant research focuses on the central or leading actor, whereas our understanding of other actors’ strategies and foci in coopetition strategizing are largely absent from the literature.

Typically, firm-, relationship-, network- and industry-level factors combine to play a role in determining the likelihood of coopetition adoption, as proposed in a theoretical model for coopetition in innovation (Gnyawali & Park, 2009). Network coopetition appears to be complex, by the number of actors involved and their respective relationship and, a dynamic phenomenon, by the interactions (both collective and unilateral) that unfold over time. Hence, various coopetitive behaviors may be displayed on various markets. Prior research has used structural variables (Luo, 2004; Chin et al., 2008) in order to identify coopetition types depending on the intensity of collaboration and competition, or behavioral variables to develop a coopetition typology based on a firm’s behavioral pattern (Lado et al., 1997).

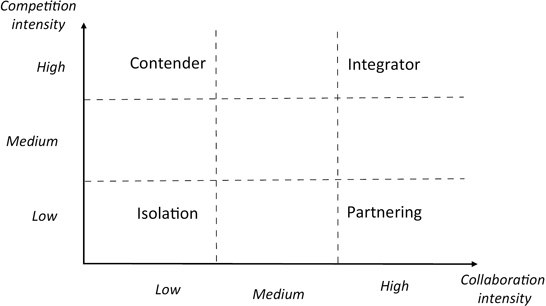

The structural approach uses the relative strength of competition and collaboration to develop a relationship typology. Coopetition can be dominated by collaboration, or by competition, or display an equal strength of its components (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000). Furthermore, a matrix (Figure 4.3) of coopetition types has been developed (Luo, 2004) based on separate and orthogonal measurement of collaboration (high- or low-intensity) and competition (high- or low-intensity). As yet, moderate degrees of relationship intensity have not been identified.

The behavioral approach focuses on strategic behaviors of firms (Lado et al., 1997), an approach that avoids measurement issues. Firms display different profiles depending on their collaborative or competitive mix: monopolistic when firms are unwilling to both collaborate and compete; collaborative rent-seeking when they opt for partnering and leave completion beyond the scope of preferred behaviors; competitive rent-seeking when they opt for rivalry; and syncretic rent-seeking when collaborative and competitive behaviors are strongly manifested.

A study on the Polish electricity market recognised the development of the behavioral approach by identifying passive and active behaviors (Czakon & Rogalski, 2014). Passive collaboration reflects firms’ mutual interactions that are mandatory by law, where a large partner cannot refuse to collaborate if asked to do so but is not seeking collaboration. Inversely, active collaboration refers to deliberate collaboration such as partnering agreements or market actions coordinated among firms. Similarly, passive competition refers to non-targeted marketing, sales promotion conducted in the media and sales to customers done only in reaction to their own requests. Finally, active competition encompasses sales activities of firms involving direct, intentional and aggressive sales aimed at specific customers. Evidence shows that firms display three distinct types of coopetitive behavior: passive coopetition, mixed coopetition or flexible coopetition. Interestingly, this study unveils that coopetition can be both active and passive. As a result, the matrix of possible coopetition types expands to nine, capturing passive, passive/active and fully active behaviors (Czakon & Rogalski, 2014). Hence, coopetition takes several forms, with many actors, and a mix of relationships is deliberately adopted by firms.

All in all, coopetition has so far revealed many manifestations, both from a typological perspective developed in early conceptual contributions and from an empirical perspective. Firms face the challenge of shaping their portfolio of relationships with relevant actors in their own environment.

Network coopetition entry: A leap of faith

Game-theoretical models suggest that collaboration with rivals is the best strategy for all involved parties (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1997). However, empirical applications of those models show that firms are reluctant in adopting coopetition, even if it came in connection with clear benefits (Okura, 2007).

Coopetition adoption likelihood models indicate several factors that may play a role in the process: those connected with either the industry, the firm or the dyad. Industry-specific factors are attributed with an interesting feature of impacting all industry players in a similar way, so that they shape the likelihood of coopetition adoption in a given industry (Gnyawali & Park, 2009). In order to explain the adoption of coopetition by a particular firm, scholars have referred to its strategic challenges: gaining access to valuable resources (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000), increasing the market, improving efficiency and strengthening the competitive position (Ritala et al., 2014). Coopetition appears to be instrumental in alleviating resource constraints and in achieving clear-cut strategic objectives by establishing collaboration with a purposefully selected partner. Therefore, dyadic factors are important in coopetition adoption because the partner is expected to provide complementary resources, similar resources, technological capabilities and pursue congruent strategic goals (Gnyawali & Park, 2009).

If industry-, dyad- and firm-level factors are in place, managers still need to adopt a mindset that allows collaboration with others, including rivals, in a shift of attention from the focal firm to the network (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1997). More generally, at a micro-fundamental level of analysis coopetition depends on the extent of: the understanding of private and common benefits, micro or macro ways of thinking, perceived levels of interdependence, perceived levels of complementarity, the personality of owners/managers, the availability of leadership, the locality of marketing activities and a focus on total experience by tourists (Wang, 2008).

Although the drivers for dyadic coopetition occurrence have been discussed in the literature, we lack insight into why firms would join coopetition networks. The dyad-formation decision is very different from network entry. One reason is that at dyadic level interactions connect parties knowledgeable of each other, while at network level the number of partners makes it very difficult to gather necessary information, update it and control the behaviors of others. While the role of control is attributed or taken by a leading actor, the scope of control of all other network members remains limited. Also, in multiparty settings harmful behaviors of one or several partners are more difficult to identify than in dyads, which may foster opportunism of some actors (Zeng & Chen, 2003). Additionally, the influence of a firm on the selection of other partners is limited (Czakon & Czernek, 2016). As a result, “swimming with sharks” (Katila et al., 2008) or “sleeping with the enemy” (Gnyawali & Park, 2009), referring to potential misbehavior and misappropriation of value, is magnified at network level.

Hence, network coopetition requires firms to place their trust in others. Perhaps the most challenging application of trust is related to competitors. This “leap of faith” complements rational calculation to predict partners’ behavior-prediction (Kumar & Das, 2007). Researchers have identified trust as a coopetition success factor during the process (Chin et al., 2008), examined its relationship to innovation output (Bouncken & Fredrich, 2012) and suggested its critical role at the formation stage of multiparty coopetition (Wang, 2008).

Trust is more than a phenomenon that spontaneously emerges between individuals, but rather a dynamic process that can be influenced, shaped and purposefully used by managers (Bachmann, 2011). In business relationships trust develops in interrelated processes: calculative, capability assessment, intentions assessment, reputation and transference (Doney & Cannon, 1997). The application of a framework of trust-building processes to network coopetition formation reveals that they play various roles.

Difficulties related to the development of calculative, capability-based and intentionality-based trust in network coopetition have been empirically grounded (Czakon & Czernek, 2016). Indeed, identifying prospective benefits in network coopetition and gathering necessary information on the coopetition network is time-consuming and requires experience, analytical skills and information access. Consequently, the trust-building mechanisms usually associated with successful trust-building at dyadic level do not appear to have a positive impact, or any impact, in network settings (Czakon & Czernek, 2016).

By contrast, transference from public-sector institutions appears to be a strong trust-building mechanism, a sufficient condition to join network coopetition. More than inciting or pushing firms into coopetition (Kylänen & Mariani, 2014), public institutions are crucially important in establishing trust among actors. Public authorities are perceived as dedicated to common benefits, as opposed to private actors, who are instead focused on their own private benefits. Additionally, reputation has been found to be a strong trust-building mechanism, especially in small communities. It creates trust sufficient to engage into network coopetition with reputable actors.

Environment- and firm-level drivers fail to explain network coopetition formation. At network level, partner selection is not the key issue. Instead, the dilemma of accepting or turning down the opportunity to join a network is as a key challenge.

Common benefits in coopetition

The paradoxical nature of coopetition attracts all the more attention; normative theories clearly indicate it can be expected to yield benefits otherwise unavailable (Czakon, 2010). Scholars have therefore investigated the benefits that firms may achieve by engaging in coopetition.

Value creation involves synergies by integrating complementary and supplementary resources among competitors. Collaborating with competitors offers the unique advantage of similar positioning in the industry and understanding the customers, business logic and technologies, which fosters knowledge-sharing and available efficiency increases (Ritala & Tidström, 2014). Collaboration involves the process of combining and jointly exploiting resources held by many firms in order to synergistically generate more value than would be possible if the resources were kept separate (Dyer et al., 2008). Collaborating firms generate private benefits, which accrue to the individual firm within the alliance, and common benefits, which accrue collectively to all participants (Khanna et al., 1998).

An emerging thread of research focuses instead on identifying the benefits available to many involved parties through collaboration. “Benefits” refer to the process of value appropriation (Volschenk et al., 2016). Distinct types of benefits have been identified: private, common and public. Private benefits are those that a “firm can earn unilaterally by picking up skills from its partner and applying ... to its own operations in areas unrelated to the alliance activities” (Khanna et al., 1998). “Common benefits” refer to benefits that accrue collectively to all participants in the alliance, and can be captured by each partner of the cooperative relationship (Khanna et al., 1998). Interestingly, common benefits are both a collective benefit of all network coopetitors and a privately captured share (Volschenk et al., 2016). Public benefits are available in turn to society due to coopetitive network operations. These latter benefits are either released purposefully or cannot be effectively protected by the network coopetitors.

A study of the Polish energy balancing market addressed the question of common benefits and provided evidence that coopetition is indeed different from collusion (Czakon et al., 2016). In the energy market, each actor acts separately, and all collectively face the problem of the technical requirement of balancing energy supply and demand at any time, coupled with legal pressures from independent actors to achieve this objective, and a financial drive to balance the market at the lowest possible cost. Indeed, coopetition significantly decreases the balancing costs of all involved firms; this effect is not random, but is connected with the increasing number of coopetitors. Rivals have entered coopetitive relationships because of an inability to achieve efficiency increases alone; they have further developed the coopetition network in order to maximize available common benefits.

The classic competitive strategy argument is that increases in market power lead to lower supply prices. Such increases can be achieved by collectively acting with rivals. This view on collective action focuses on value appropriation, rather than on value creation. The study of the Polish energy balancing market coopetition shows how firms can generate cost reductions for all participants. The best choice is to collaborate with one’s rival, as it has similar concerns, needs and capabilities. Such collaboration is value-adding, and not value-capturing, as it does not exert increased market power on actors outside the coopetition network. Interestingly, involved firms realized the benefit when they started to work together in small groups, and then expanded the network by including more and more actors. More than increasing individual efficiency, coopetition offers collective or common efficiency increases.

Conclusions

The network level of analysis reflects the normative, original meaning of the coopetition concept. Collaboration with various actors, despite conflicting interests or direct rivalry, may largely contribute to an increase in total available value. While directly alleviating resource access concerns, increasing market power and firms’ efficiency (Ritala, 2012), network coopetition also generates common benefits, available to all involved parties (Czakon et al., 2016), and public benefits that accrue to society due to coopetitive relationships (Volschenk et al., 2016). At the network level of analysis, the emergence of additional value is more important as compared to dyads. Further research may address common benefits, public benefits and private capturing of those benefits. If cooperation is an efficient way of utilizing limited resources and coopetition a way of managing both competition and collaboration (Wang & Krakover, 2008), then sustainability calls for more attention. Common pool resources need careful governance in order to avoid overexploitation, opportunism or the pursuit of selfish interests at the expense of other actors. Further research in coopetition needs to address value networks as socio-ecological systems where sustainability plays a crucial role (Pathak et al., 2014).

Differently from a dyadic setting, where collaborating with a rival is largely deliberate, coopetition has also been revealed as an emergent strategy at network level. Deliberate network coopetition identified in supply chains appears to be much different from self-initiated and self-coordinated relations between suppliers that lack a moderating third party, and is more likely to be characterized by an equal distribution of power (Wilhelm, 2011).

Various pressures impact on the likelihood of collaboration between many rivals. Pressures may emerge within otherwise collaborative settings due to relational concerns (Czakon, 2010), or within clearly competitive settings due to common issues that are impossible to cope with alone (Czakon & Czernek, 2016). Long-term studies indicate that the pursuit of value appropriation induces airlines to enter into various dyadic and network relationships with rivals (Czakon & Dana, 2013).

Whenever firms decide to launch a network coopetition project, challenges that differ between partners need to be addressed. Trust is necessary to enter network collaboration with rivals, even if theoretical propositions suggest a dominant role of business needs over trust in a network setting (Gnyawali et al., 2006). Our current understanding of network coopetition antecedents is limited to theoretical propositions and qualitative studies. Propositions need quantitative testing in order for us to understand the process of network coopetition emergence, including industry specificity and cultural contingencies (Rusko, 2011).

How network coopetition receives a design, an architecture of relationships and a centralized management within emerging setting governance is clearly under-researched. Some emerging archetypes have been identified in supply network coopetition (Pathak et al., 2014), in horizontal coopetition (Czakon & Rogalski, 2014) or in coopetitive networks (Gnyawali et al., 2006), but other manifestations in different industry settings need to be identified. Coopetition is recognized as an industry-specific phenomenon, therefore it is necessary expand research on different industries in order to increase the generalizability of findings (Wilhelm, 2011) and to carry out industry comparisons (Rusko, 2011), including high-tech versus traditional industries (Sanou et al., 2016).

The distinctive assumption within the network stream of coopetition research is that vertical relationships impact horizontal relationships (Wilhelm, 2011), as much as indirect relationships impact direct relationships around a firm. Therefore, our understanding of network’s dynamics requires a close scrutiny of network structural characteristics (Pathak et al., 2014) and coordination mechanisms (Wilhelm, 2011). Prior research on the role of network centrality (Gnyawali et al., 2006; Sanou et al., 2016) indicates a strong association between this structural variable and competitive aggressiveness. Expanding the scope of scrutiny may involve other structural variables, such as heterogeneity, density or size impact on coopetitive dynamics, firm behavior and performance. Interestingly, central actors who take the leading role in designing and exploiting network coopetition have been in focus (Sanou et al., 2016), while non-central and peripheral actors have received much less attention (Czakon & Czernek, 2016). Yet, our understanding of network coopetition cannot be comprehensive if the motives, behaviors and performance of non-central actors are left beyond the scope of scrutiny.

Network coopetition poses distinct methodological challenges due to its inherent complexity and dynamics. This thread of research refers to the original idea of value nets, which populate the landscape. Figure 4.1 clearly shows that extant research needs to address the whole value net. So far, researchers have been reducing the scope of attention and leaving some actors and respective relationships beyond scrutiny. Therefore typologies, process models and comprehensive models explaining behavior and performance of both the individual member and the whole network offer immense opportunities for future research.

References

Bachmann, R. (2011). At the crossroads: Future directions in trust research. Journal of Trust Research, 1(2), 203–213.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2000). “Coopetition” in business Networks—to cooperate and compete simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(5), 411–426.

Bouncken, R. B. & Fredrich, V. (2012). Coopetition: performance implications and management antecedents. International Journal of Innovation Management, 16(05), 1250028.

Brandenburger, A. M. & Nalebuff, B. J. (1997). Co-Opetition: A revolution mindset that combines competition and cooperation: the game theory strategy that’s changing the game of business. Currency Double Day, New York.

Chin, K. S., Chan, B. L., & Lam, P. K. (2008). Identifying and prioritizing critical success factors for coopetition strategy. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 108(4), 437–454.

Czakon, W. (2009). Power asymmetries, flexibility and the propensity to coopete: an empirical investigation of SMEs’ relationships with franchisors. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 8(1), 44–60.

Czakon, W. (2010). Emerging coopetition: an empirical investigation of coopetition as inter-organizational relationship instability. In Yami, S., Castaldo, S., Dagnino, G. B., & Le Roy, F. (Eds), Coopetition: Winning Strategies for the 21st Century. Cheltenham; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, pp. 58–72.

Czakon, W. & Dana, L. P. (2013). Coopetition at Work: how firms shaped the airline industry. Journal of Social Management/Zeitschrift für Sozialmanagement, 11(2).

Czakon, W., Fernandez, A. S., & Minà, A. (2014a). Editorial–From paradox to practice: the rise of coopetition strategies. International Journal of Business Environment, 6(1), 1–10.

Czakon, W., Mucha-Kuś, K., & Sołtysik, M. (2016). Coopetition strategy—what is in it for all? A study of common benefits in the Polish energy balancing market. International Studies of Management & Organization, 46(2–3), 80–93.

Czakon, W. & Rogalski, M. (2014). Coopetition typology revisited–a behavioural approach. International Journal of Business Environment, 6(1), 28–46.

Czakon, W. & Czernek, K. (2016). The role of trust-building mechanisms in entering into network coopetition: The case of tourism networks in Poland. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 64–74.

Della Corte, V. & Aria, M. (2016). Coopetition and sustainable competitive advantage. The case of tourist destinations. Tourism Management, 54, 524–540.

Doney, P. M. & Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. The Journal of Marketing, 35–51.

Dyer, J. H., Singh, H., & Kale, P. (2008). Splitting the pie: rent distribution in alliances and networks. Managerial and Decision Economics, 29(2–3), 137–148.

Fernandez, A. S., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Sources and management of tension in co-opetition case evidence from telecommunications satellites manufacturing in Europe. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 222–235.

Gnyawali, D. R., He, J., & Madhavan, R. (2006). Impact of co-opetition on firm competitive behavior: An empirical examination. Journal of Management, 32(4), 507–530.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Park, B. J. R. (2009). Co-opetition and technological innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises: A multilevel conceptual model. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(3), 308–330.

Katila, R., Rosenberger, J. D., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2008). Swimming with sharks: Technology ventures, defense mechanisms and corporate relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly, 53(2), 295–332.

Khanna, T., Gulati, R., & Nohria, N. (1998). The dynamics of learning alliances: Competition, cooperation, and relative scope. Strategic Management Journal, 193–210.

Kumar, R. & Das, T. K. (2007). Interpartner legitimacy in the alliance development process. Journal of Management Studies, 44(8), 1425–1453.

Kylänen, M. & Rusko, R. (2011). Unintentional coopetition in the service industries: The case of Pyhä-Luosto tourism destination in the Finnish Lapland. European Management Journal, 29(3), 193–205.

Kylänen, M. & Mariani, M. M. (2014). The relevance of public-private partnerships in coopetition: Empirical evidence from the tourism sector. International Journal of Business Environment 5, 6(1), 106–125

Lado, A. A., Boyd, N. G., & Hanlon, S. C. (1997). Competition, cooperation, and the search for economic rents: a syncretic model. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 110–141.

Le Roy, F. & Czakon, W. (2016). Managing coopetition: the missing link between strategy and performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 3–6.

Luo, Y. (2004). A coopetition perspective of MNC–host government relations. Journal of International Management, 10(4), 431–451.

Mariani, M. M. (2007). Coopetition as an emergent strategy: Empirical evidence from an Italian consortium of opera houses. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 97–126.

Mariani, M. M. (2016). Coordination in inter-network co-opetitition: Evidence from the tourism sector. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 103–123.

Mintzberg, H. & Waters, J. A. (1985). Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6(3), 257–272.

Nielsen, B. B. (2011). Trust in strategic alliances: Toward a co-evolutionary research model. Journal of Trust Research, 1(2), 159–176.

Okura, M. (2007). Coopetitive strategies of Japanese insurance firms a game-theory approach. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 53–69.

Pathak, S. D., Wu, Z., & Johnston, D. (2014). Toward a structural view of co-opetition in supply networks. Journal of Operations Management, 32(5), 254–267.

Ring, P. S. & Van de Ven, A. H. (1994). Developmental processes of cooperative interorganizational relationships. Academy of Management Review, 19(1), 90–118.

Ritala, P. (2012). Coopetition strategy—when is it successful? Empirical evidence on innovation and market performance. British Journal of Management, 23(3), 307–324.

Ritala, P. & Tidström, A. (2014). Untangling the value-creation and value-appropriation elements of coopetition strategy: A longitudinal analysis on the firm and relational levels. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(4), 498–515.

Ritala, P., Golnam, A., & Wegmann, A. (2014). Coopetition-based business models: The case of Amazon. com. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 236–249.

Rusko, R. (2011). Exploring the concept of coopetition: A typology for the strategic moves of the Finnish forest industry. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(2), 311–320.

Sanou, F. H., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2016). How does centrality in coopetition networks matter? An empirical investigation in the mobile telephone industry. British Journal of Management, 27(1), 143–160.

Selin, S. & Chavez, D. (1995). Developing an evolutionary tourism partnership model. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(4), 844–856.

Tidström, A. (2009). Causes of conflict in intercompetitor cooperation. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 24(7), 506–518.

Volschenk, J., Ungerer, M., & Smit, E. (2016). Creation and appropriation of socio-environmental value in coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 109–118.

von Friedrichs Grängsjö, Y. (2003). Destination networking: Co-opetition in peripheral surroundings. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 33(5), 427–448.

Wang, Y. (2008). Collaborative destination marketing understanding the dynamic process. Journal of Travel Research, 47(2), 151–166.

Wang, Y. & Krakover, S. (2008). Destination marketing: competition, cooperation or coopetition?. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20(2), 126–141.

Wilhelm, M. M. (2011). Managing coopetition through horizontal supply chain relations: Linking dyadic and network levels of analysis. Journal of Operations Management, 29(7), 663–676.

Zeng, M. & Chen, X. P. (2003). Achieving cooperation in multiparty alliances: A social dilemma approach to partnership management. Academy of Management Review, 28(4), 587–605.