Dynamics of coopetitive value creation and appropriation

Paavo Ritala and Pia Hurmelinna-Laukkanen

Introduction

Coopetition is a relationship in which competition and collaboration co-exist, constituting a persisting paradox (Gnyawali et al., 2016). This paradox invites numerous tensions, in particular those of value creation and value appropriation (for discussion, see Bouncken et al., 2018; Raza-Ullah et al., 2014; Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009; Volschenk et al., 2016). Such value-related analysis has been at the core of theorizing about coopetition ever since its seminal formulation (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996), and these two concepts are broadly used to explain how value is created via coopetition relationships, and how this value is captured and divided.

Value creation and appropriation in coopetition—and their interplay—is a multifaceted issue. At the firm strategy level, coopetition provides additional means for individual companies to create value in collaboration with their competitors and to appropriate a share of that value themselves. Several case-based studies have shown how firms have adopted a coopetition strategy for these purposes. For instance, Ritala et al. (2014) show how Amazon.com developed business models that allowed the firm to collaborate with its competitors, to jointly create value via increasing online sales, and finally, to appropriate a margin of the growing markets. Similarly, the LCD TV market collaboration between Samsung Electronics and Sony Corporation demonstrates the challenges and opportunities of coopetition for value creation and appropriation (see Gnyawali & Park, 2011).

At the relationship and network levels, coopetition is seen as a particular context within which value is created and appropriated, creating a juxtaposition that has implications for the management and outcomes of the relationship (see, e.g., Bouncken et al., 2018; Fernandez et al., 2014; Fernandez & Chiambaretto, 2016). In coopetition relationships, value creation and appropriation are continuously adjusted, bargained and developed in an interactive process between the actors (Raza-Ullah, Begntsson, & Kock, 2014; Ritala & Tidström, 2014; Yami & Nemeh, 2014).

These processes also unfold over individual and collective levels of analysis. Value creation can happen partially within individual organizations, or it can be conducted via joint activities. Similarly, value can be appropriated jointly (e.g., via joint products and service sales) or individually, for example, by differentiating products and services under different brands among those involved in coopetition (Gnyawali & Park, 2011). Therefore, these processes are complex and multilevel, and further clarity of their interplay and dynamics is needed.

In order to improve our understanding of the important conceptual underpinnings of value creation and appropriation in coopetition, we first briefly discuss them within the general inter-organizational context. This is followed by a discussion of a “baseline model,” which is the typically utilized logic across theoretical and empirical contributions. Following this, we introduce a more detailed conceptual model that describes how value creation and appropriation are interconnected over time, including feedback loops that explain the temporal dynamics. This model contributes to the coopetition literature by providing an overarching framework to explain how coopetition helps to create and appropriate value.

Value creation and appropriation in the inter-organizational context

In economics, value refers formally to the end customer’s willingness to pay for a certain product, service, or offering (Brandenburger & Stuart, 1996). The important question for strategy research, then, is by whom and how can this value be created, and by whom and how can this value be appropriated? (See also Garcia-Castro & Aguilera, 2015.)

Value creation refers to the activities in the value chain that increase the end customer’s willingness to pay (Bowman & Ambrosini, 2000; Brandenburger & Stuart, 1996). Firms engage in value creation when the profits generated by an activity exceed the input required (Lepak et al., 2007). Such added value contributions can include any activities that end up increasing the perceived value by those receiving it, from early-stage research and development to the provision of materials and resources and branding and marketing.

Inter-organizational relationships, such as alliances, networks, and ecosystems, provide opportunities to facilitate and advance value creation by providing chances to integrate complementary and supplementary resources and capabilities (Barringer & Harrison, 2000; Das & Teng, 2000). Regardless of the actual form of these relationships, the key logic for value creation is that more value is created jointly compared to the resources and capabilities being utilized in separation (Dyer & Singh, 1998).

However, the (jointly) created value is not worth much to its creators if it is not appropriated in the end (Arrow, 1962). In general, value appropriation can be defined as extracting profits in the marketplace (Teece, 1986; 1998). Value appropriation involves various activities, and several mechanisms have been identified that increase appropriability. Typically, these mechanisms relate to protecting valuable assets and creations (Alnuaimi & George, 2016; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen & Olander, 2014) and utilizing the mechanisms to regulate their exclusivity, free use, and controllability (Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2012; James et al., 2013). Value appropriation is also future-oriented. It is important also to recognize the potential to generate future profits based on previous value appropriation (Ahuja et al., 2013; Gans & Ryall, 2017).

In inter-organizational arrangements, value appropriation easily becomes a debated issue, as firms bargain over the division of value (Adegbesan & Higgins, 2011; Dyer et al., 2008). For instance, there may be firm-level concerns about others exploiting the assets that an actor provides for the collaborative activities (Heiman & Nickerson, 2004; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen & Olander, 2014). Likewise, it may not always be easy to decide how the jointly created outputs are going to be appropriated (see, e.g., James et al., 2013 on alternative strategies for value capture) and if an individual actor is able to secure its part (Dyer et al., 2008). However, appropriation can also be viewed at the relationship and network levels. Not only do organizations compete against each other for their share of value (Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009); networks also compete with other networks, which further changes the dynamics of appropriation (see Nätti et al., 2014). Coopetition context provides specific implications for value creation and appropriation, as discussed in the following.

Value creation and appropriation in coopetition: From a baseline model to dynamic interplay

In laying out the game-theoretic foundation for coopetition, Brandenburger & Nalebuff (1996) put forward the seminal quote:

Co-opetition means cooperating to create a bigger business “pie”, while competing to divide it up

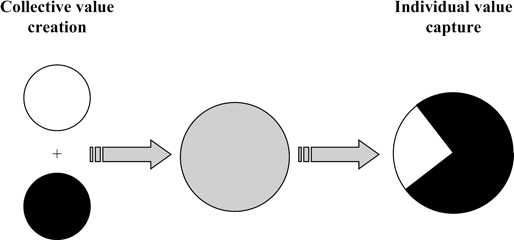

Coopetition literature has built strongly on this idea, and much of the literature is based on the foundational assumption that coopetition allows firms to create more value together and, thus, there will be more for each actor to appropriate later on. Competing firms are seen to collectively create value together when this increases the “size of the pie” more than if firms would not engage in such activity. Such value might include economic and social benefits, larger markets, new knowledge and innovation, and so forth (for a discussion, see, e.g., Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009; Volschenk et al., 2016). Value appropriation, however, is considered an individual activity in which competitors try to capture a share of the created value. The “slice of the pie” among actors changes based on their own differentiation abilities, and on the appropriability mechanisms at the disposal of each actor (Gnyawali & Park, 2011; Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009). The competitive setting also means that the value appropriation phase is subject to more tensions than in relationships among non-competitors (see, e.g., Bouncken et al., 2018; Yami & Nemeh, 2014, for discussion). Figure 5.1 illustrates this baseline model.

As visualized in Figure 5.1, coopetition provides opportunities for creating more value than is available for individual actors (illustrated by a larger range of the collective gray area in contrast to the individual white and black circles). Furthermore, it is shown here that value appropriation often ends up being asymmetrical (illustrated in that the “black firm” appropriates a larger share of the value created). However, this is merely for illustration purposes, as value appropriation can also be more or less symmetrical, depending on the context and contingencies of the coopetition relationship, as well as the individual abilities and aspirations of the actors in appropriating the value.

For most purposes, this simplified model provides a good foundation for explaining value creation and appropriation processes in coopetition. Consider, for example, how collective R&D efforts by Sony and Samsung turn into firm-specific pursuits to capture profits from consumer markets (Gnyawali et al., 2011) or how the global automotive industry creates value by developing joint technology while later competing for market share in the end-product markets (Gwynne, 2009; Wilhelm, 2011).

However, we argue that the processes are often more complex than portrayed in the baseline model. At first sight, value creation and appropriation might look polarized among the elements of coopetition; that is, collaboration relates to value creation and competition to value appropriation. However, in reality, value is being created and appropriated by individual firms themselves and within the scope of the coopetition relationship (see, e.g., Ritala & Tidström, 2014). Value creation and appropriation in coopetition can be viewed as ongoing parallel processes that are mutually interconnected and dynamic, and that can be seen to affect each other over time (Bouncken et al., 2018; Yami & Nemeh, 2014). In this regard, the logic of coopetition, and especially the duality of value creation and appropriation, can be viewed from the paradox perspective, where they are portrayed as mutually interdependent, parallel, and continuous processes (Gnyawali et al., 2016).

In the remainder of this chapter, we develop an extended model that takes into account the parallel, interdependent, and dynamic nature of these processes, as shown in Figure 5.2.

Individual and collective value creation

The baseline model (Figure 5.1) gives an impression that the value creation side of coopetition is straightforward. Resources are combined to produce unique combinations and synergy. In this sense, competitors can utilize their joint background knowledge of markets and technologies to efficiently put together their existing resources (Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009).

However, at the firm level, contributing to value creation also means providing relevant resources to competitors, potentially leading to the emergence of coopetitive tensions in value creation (Bouncken et al., 2018). In the best case, the returns are high nevertheless. For instance, Ritala (2009) suggests that the competitive background between collaborating actors might enable them to create more value than is the case with non-competitors. Furthermore, Alnuaimi & George (2016) suggest that, in the long term, the immediate loss of knowledge to other actors can be recuperated by absorbing refined knowledge. It is shown in Figure 5.2 that collective alignment enables competitors to jointly create value beyond individual contributions, which can be divided by the same actors.

In the value creation phase, the coopetitors naturally assess the prospects of value appropriation in the future (Bouncken et al., 2018). We refer to this process as the anticipated appropriability (see Figure 5.2, feedback loop at the bottom). This term illustrates the temporal feedback component, which emerges as firms see the prospects for appropriating value from the coopetition relationship and are consequently motivated to provide inputs to mutual value creation. In essence, the incentive effect of anticipated appropriation suggests that the “shadow of the future” connects value appropriation and creation. The actual experience of increased appropriability can strengthen this link. On the negative side, the firms might see that their prospects for value appropriation are weak. This might lead to a risk of harming future developments due to overprotection and underinvestment in the firm’s own development activity (Bouncken et al., 2018; Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009).

Individual and collective value appropriation

For actors to have incentives to engage in coopetition and joint value creation in the first place, a value appropriation trajectory needs to be in sight (Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009). As depicted on the right side of Figure 5.2, value appropriation is fundamentally based on individual aspirations, where each competitor aims to gain as big a share of the jointly created value as possible, following the pie-splitting logic of coopetition and alliances in general (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996; Dyer et al., 2008).

However, at the same time, there are other dynamics to be considered: within alliances and networks, value appropriation often pursues to achieve fair allocation of the results (see, e.g., Adegbesan & Higgins, 2011; Dhanaraj & Parkhe, 2006) but also may extend to making sure that the value created benefits the actors within the coopetition networks rather than those outside (see Hurmelinna-Laukkanen et al., 2012). In this way, the value appropriation activity can be collective, and the companies involved in coopetition may well put joint effort into extending appropriation possibilities for all participants (see, e.g., Nätti et al., 2014; Ritala & Tidström, 2014). This is shown as the expanding value appropriation area on the right side of Figure 5.2.

Furthermore, the individual appropriability for different firms in coopetition is also affected by the governance form and other coordination mechanisms of the coopetition relationship. For instance, joint ventures and other equity-based arrangements typically provide a relatively clear contractual base for dividing the profits from alliances and partnerships. However, for non-equity alliances that rely on formal and relational contracts, the division of value is not as clear-cut (see, e.g., Contractor & Ra, 2002; Olander et al., 2010; Oxley, 1997). In those cases, the relational dynamics of coopetition and individual firms’ efforts affect the individual share of the value appropriated more (see, e.g., Ritala & Tidström, 2014).

In the best cases, the increase in value appropriation at the relationship or network level means that the companies involved in coopetition benefit not only from the immediate profits but can also start a new cycle of value creation. The anticipated appropriability is not the only mechanism that can connect value appropriation to further value creation; as the willingness of end customers to pay results in increased profits, there are more resources to allocate to new value creation endeavors. In addition, the generated outputs can be turned into background assets for subsequent value creation (Alnuaimi & George, 2016). This generative appropriability (Ahuja et al., 2013) is a relevant feedback component between value appropriation and subsequent value creation (see Figure 5.2, feedback loop at the top).

Implications

Overall, our chapter provides several implications for coopetition research, practice, and policy, and outlines useful directions for future research. These implications are discussed next.

Research implications

Joint value creation is a central motivation for coopetition. In this chapter, we extended this logic further. In particular, we suggest that this activity is not solely collective, as is often depicted, but simultaneously takes place individually, with the potential to concurrently provide individual benefits (see also Alnuaimi & George, 2016). At the same time, negative outcomes may emerge if a firm’s contribution is exploited by others, the value creation inputs are unequal, or if the firm becomes held captive by the coopetition activity, unable to pursue its own development trajectories.

Our model further suggests that value appropriation relates to individual pursuits to maximize the share of the value captured, as well as to collective efforts in this regard. The former aspect is well researched, while the latter has received less attention. Although distributing the outputs fairly among the actors and allowing individual value appropriation is relevant (Dhanaraj & Parkhe, 2006; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen et al., 2012), joint efforts for increasing overall value appropriation should be considered. From this perspective, the boundaries of appropriation can also be linked at the collective level, where competitors jointly improve the overall appropriation (e.g., Ritala & Tidström, 2014). In that case, value appropriation enhances the overall commercial exploitation and prevents valuable knowledge from leaking to rival networks or companies (Hurmelinna-Laukkanen et al., 2012; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen & Olander, 2014).

Following the definition of paradox (Gnyawali et al., 2016; Smith & Lewis, 2011), we perceive value creation and appropriation as interdependent forces that persist over time in coopetition relationships. This means that value creation and appropriation are interconnected in a dynamic interplay with several feedback loops. The developed framework (Figure 5.2) shows two feedback loops—anticipated and generative appropriability—that connect value creation and appropriation. The first relates to individual actors’ anticipated value appropriation, which affects their motivations to provide inputs to the value creation, while the latter refers to the resources available for value creation that are generated over time through appropriation. Although the existence of generative appropriability (Ahuja et al., 2013) in particular has been acknowledged in literature (more and less implicitly), placing these feedback components explicitly within the coopetition context allows understanding of the dynamics that guide these activities.

Practical and policy implications

For coopetition practice, our model suggests that collective and individual aspirations need to be balanced throughout coopetitive relationships. For instance, the motivations to participate in value creation need to be examined actor by actor, and reflected against anticipated value appropriation prospects. Furthermore, free riding and opportunism need to be dealt with efficiently to maintain a collective and individual balance of inputs and captured value, in the short and long term.

In addition, important policy implications are related to collusive features of value creation and appropriation, which are often overlooked. In general, value created in coopetition is expected to benefit the actors involved and to spill over to the end customers. However, there are also situations where the value creation-appropriation connection generates negative market implications. One notable issue is that oligopolistic market features may emerge that diminish the actual value to end customers or suppliers. If coopetition affects appropriation in such a way that the bargaining power of downstream and/or upstream markets is too heavily restricted, a collusion problem emerges (see Pressey et al., 2014; Pressey & Vanharanta, 2016).

As competitors join forces in value creation, the number of alternative offerings might be limited, and some developments are unrealized. This outcome might relate to limited resources and attention, or to power relationships, where one firm sets the direction for other companies. When a coopetitive arrangement is formed, it may be that such a firm (or a group of firms) eventually directs the whole industry along a specific path (see Wiener & Saunders, 2014).

Collective forms of coopetitive value appropriation may be at least equally problematic. Different forms of cartels with price-fixing and dividing of markets may emerge from initially beneficial coopetition activities (Pressey & Vanharanta, 2016). In these instances, the value spilling over to end customers might be directly limited as collaborating competitors retain a larger part of it with increasing margins. The value appropriated might also be controlled indirectly as firms outside the coopetition get pushed aside.

This issue has been acknowledged by policy makers and regulators. Competition laws have been introduced to address these issues, such as Article 101(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) prohibiting competition-restricting collaboration by competitors, accompanied by Article 101(3), which allows for joint value creation when the benefit goes to consumers. That is, as long as coopetitive value creation and value appropriation do not endanger the benefit of end customers, such activities are acceptable. In the best cases, the created value in coopetition is notable enough to benefit the involved competitors and the end customers, and healthy competition creates further differentiation, innovation, and market development.

Future research agenda

Value creation and appropriation—in addition to collaboration and competition—are probably the most decisive theoretical components that have been used to explain the coopetition phenomenon (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996; Gnyawali et al., 2016; Raza-Ullah et al., 2014; Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009; Volschenk et al., 2016). In this chapter, we briefly outlined an integrative view of the state of the art in this regard and put forward a suggestion for a dynamic model of value creation and appropriation in coopetition. Even with the cumulating evidence in coopetition literature, there are yet-unexplored aspects, especially when we take the dynamic view suggested in the current study. This provides several avenues for further conceptual and empirical inquiry.

First, further studies could examine the interplay of value creation and appropriation. Based on the research discussed throughout this chapter, we know that value creation and appropriation affect each other and are often parallel processes, not just sequential (i.e., creation precedes appropriation). Examining the tensions arising from this parallel processing of partially contradictory logics could build on the strategic dualities and paradox research (e.g., as suggested by Gnyawali et al., 2016) in further explaining how firms in coopetition can cope with often opposing demands. This calls for firm-level inquiry where individual firms’ abilities to cope with such a paradox are investigated, as well as alliance-, network-, and system-level examinations of value creation and appropriation dynamics in coopetition.

Second, the two feedback loops suggested in this study (generative appropriability and anticipated appropriability) provide opportunities for future research. For instance, how much do firms appreciate the value creation efforts in the present that have only uncertain appropriation prospects versus those with immediate ones? How do coopetitive dynamics affect this perception? For generative appropriability, how can firms in coopetition ensure that the value they appropriate can be used for future value creation in those relationships? To what extent does joint value appropriation facilitate continuity in coopetitive ties? Questions such as these call for longitudinal research designs where the process and outcomes of coopetition are examined, and the aforementioned and other links between creation and appropriation are distinguished.

Conclusion

Collective value creation has typically been seen to precede the individual value appropriation efforts in coopetition. We have argued that while this portrays many instances of coopetition, the reality is more multifaceted and there are more dynamics between and among these processes. The perspective described in this chapter suggests that instead of a linear view, a more dynamic model of value creation and appropriation is useful for capturing the temporal and inter-level dynamics of coopetition.

References

Adegbesan, J. A. & Higgins, M. J. (2011). The intra-alliance division of value created through collaboration. Strategic Management Journal, 32(2), 187–211.

Ahuja, G., Lampert C., & Novelli, E. (2013). The second face of appropriability: generative appropriability and its determinants. Academy of Management Review, 38(2), 248–269.

Alnuaimi, T. & George, G. (2016). Appropriability and the retrieval of knowledge after spillovers. Strategic Management Journal, 37(7), 1263–1279.

Arrow K. (1962). Economic welfare and the allocation of resources for invention. In: The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity: Economic and Social Factors. Nelson, R. (Ed.). New York: Princeton University Press: 609–625.

Barringer, B. R. & Harrison, J. S. (2000). Walking a tightrope: Creating value through interorganizational relationships. Journal of Management, 26(3), 367–403.

Bouncken, R., Fredrich, V., Ritala, P., & Kraus, S. (2018). Coopetition in new product development alliances: advantages and tensions for incremental and radical innovation. British Journal of Management, 29(3), 391–410.

Bowman, C. & Ambrosini, V. (2000). Value creation versus value capture: towards a coherent definition of value in strategy. British Journal of Management, 11(1), 1–15.

Brandenburger, A. M. & Nalebuff, B. J. (1996). Co-opetition. New York: Doubleday.

Brandenburger, A. M. & Stuart, H. W. (1996). Value-based business strategy. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 5(1), 5–24.

Contractor, F. J. & Ra, W. (2002). How knowledge attributes influence alliance governance choices: a theory development note. Journal of International Management, 8(1), 11–27.

Das, T. K. & Teng, B. S. (2000). A resource-based theory of strategic alliances. Journal of Management, 26(1), 31–61.

Dhanaraj, C. & Parkhe, A. (2006). Orchestrating innovation networks. Academy of Management Review, 31(3), 659–669.

Dyer, J. H. & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660–679.

Dyer, J. H., Singh, H., & Kale, P. (2008). Splitting the pie: rent distribution in alliances and networks. Managerial and Decision Economics, 29(2–3), 137–148.

Fernandez, A.-S. & Chiambaretto, P. (2016). Managing tensions related to information in coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 66–76.

Fernandez, A.-S., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Sources and management of tension in co-opetition case evidence from telecommunications satellites manufacturing in Europe. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 222–235.

Gans, J. & Ryall, M. D. (2017). Value capture theory: A strategic management review. Strategic Management Journal, 38(1), 17–41.

Garcia-Castro, R. & Aguilera, R. V. (2015). Incremental value creation and appropriation in a world with multiple stakeholders. Strategic Management Journal, 36(1), 137–147.

Gnyawali, D. R., Madhavan, R., He, J., & Bengtsson, M. (2016). The competition–cooperation paradox in inter-firm relationships: A conceptual framework. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 7–18.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Park B.-J. R. (2011). Co-opetition between giants: Collaboration with competitors for technological innovation. Research Policy, 40(5), 650–663.

Gwynne, P. (2009). Automakers hope “coopetition” will map route to future sales. Research Technology Management, 52(2), 2.

Heiman, B. A. & Nickerson, J. A. (2004). Empirical evidence regarding the tension between knowledge sharing and knowledge expropriation in collaborations. Managerial and Decision Economics, 25(6–7), 401–420.

Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2012). Constituents and outcomes of absorptive capacity – Appropriability regime changing the game. Management Decision, 50(7), 1178–1199.

Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. & Olander, H. (2014). Coping with rivals’ absorptive capacity in innovation activities. Technovation, 34(1), 3–11

Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P., Olander, H. Blomqvist, K., & Panfilii, V. (2012). Orchestrating R&D networks: Absorptive capacity, network stability, and innovation appropriability. European Management Journal, 30(6), 552–563.

James S. D., Leiblein, M. J., & Lu S. (2013). How firms capture value from their innovations. Journal of Management, 39(5), 1123–1155.

Lepak, D. P., Smith, K. G., & Taylor, M. S. (2007). Value creation and value capture: A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 180–194.

Nätti, S., Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P., & Johnston, W. (2014). Absorptive capacity and network orchestration in innovation communities – Promoting service innovation. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 29(2), 173–184.

Oxley, J. E. (1997). Appropriability hazards and governance in strategic alliances: A transaction cost approach. The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 13(2), 387–409.

Pressey, A. D. & Vanharanta, M. (2016). Dark network tensions and illicit forbearance: Exploring paradox and instability in illegal cartels. Industrial Marketing Management, 55, 35–49.

Pressey, A. D., Vanharanta, M., & Gilchrist, A. J. (2014). Towards a typology of collusive industrial networks: Dark and shadow networks. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(8), 1435–1450.

Raza-Ullah, T., Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2014). The coopetition paradox and tension in coopetition at multiple levels. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 189–198.

Ritala, P. (2009). Is coopetition different from cooperation? The impact of market rivalry on value creation in alliances. International Journal of Intellectual Property Management, 3(1), 39–55.

Ritala, P., Golnam, A., & Wegmann, A. (2014). Coopetition-based business models: The case of Amazon.com. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 236–249.

Ritala, P. & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2009). What’s in it for me? Creating and appropriating value in innovation-related coopetition. Technovation, 29(12), 819–828.

Ritala, P. & Tidström, A. (2014). Untangling the value-creation and value-appropriation elements of coopetition strategy: A longitudinal analysis on the firm and relational levels. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(4), 498–515.

Smith, W. K. & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381–403.

Teece, D. J. (1986). Profiting from technological innovation: implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy, 15(6), 285–305.

Teece, D. J. (1998). Capturing value from knowledge assets: the new economy, markets for know-how, and intangible assets. California Management Review, 40(3), 55–79.

Yami, S. & Nemeh, A. (2014). Organizing coopetition for innovation: The case of wireless telecommunication sector in Europe. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 250–260.

Volschenk, J., Ungerer, M., & Smit, E. (2016). Creation and appropriation of socio-environmental value in coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 109–118.

Wiener, M. & Saunders, C. (2014). Forced coopetition in IT multi-sourcing. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 23(3), 210–225.

Wilhelm, M. M. (2011). Managing coopetition through horizontal supply chain relations: Linking dyadic and network levels of analysis. Journal of Operations Management, 29(7), 663–676.