Introduction

In this paper, we reveal how coopetition provides a new perspective on the standardization process. Standards are “a set of technical specifications adhered to by a producer, either tacitly or as a result of a formal agreement” (David & Greenstein, 1990). They perform different functions, such as defining products, ensuring compatibility, interoperability, guaranteeing safety, and reducing variety. The current world challenges for standards are considerable. They include ensuring food security for a growing population, building more accessible and smarter communities, protecting people’s privacy, increasing cyber security and promoting economic development (ISO 2016 annual report). These challenges require knowledge about standardization, defined as the process of developing standards (understood as technical solutions that constitute market-dominant references).

Research has long differentiated standards according to two standardization processes: de facto standards are developed through market competition, and de jure standards are developed through committee negotiations. Thus, competition and cooperation are the fundamentals of standardization. Here, we explore how the introduction of the concept of coopetition, while perturbing this binary conception, offers a new view on the standardization process. We focus on the specific nature of the relationships between competitors who decide to cooperate in the standardization process. We aim to understand the strategic objectives of these coopetitors. A firm may shape and defend its own standard, ally and support a common standard, or adopt a hybrid position in searching for collaboration while seeking its own advantage. The concept of coopetition helps in understanding this situation. We suggest it throws new light on how firms manage this complex intertwinement between their individual interests and the collective mission for standards.

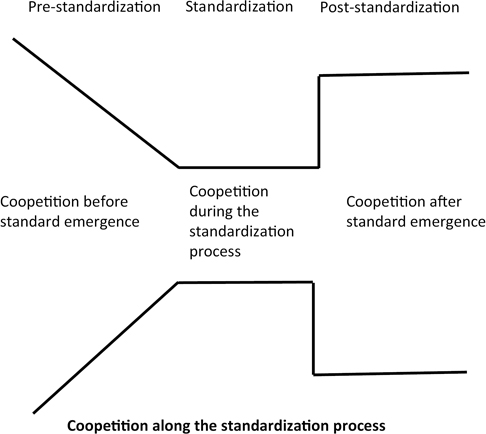

This focus leads us to disassemble the standardization process into three phases: pre-standardization, standardization, and post-standardization phases (Figure 11.1 below represents these three phases). The first phase describes a pre-standardization stadium; it presents a funnel to symbolize standardization as a movement that reduces variety. Among the diversity of techniques, devices, and solutions, only some will become standards as dominant solutions. Here, firms choose to compete, cooperate, or coopete to prepare a new standard emergence. In the contribution, we focus on coopetition strategies in this anticipatory state of a standard emergence. The second phase displays the standardization process. It represents as a rectangle to illustrate a confrontation between selected alternatives. The way sponsors support their standard against their rivals differs according to the context. In an institutional context, formal rules impose that rivals reach a consensus, which shapes specific strategies for competition, cooperation, and coopetition. In our contribution, we present research on coopetition in both market and institutional contexts. The third phase is post-standardization. We present a larger rectangle to illustrate a situation in which a standard has emerged and has largely diffused and gained dominance in the market. In this situation, the firms’ strategies concern the adoption of the standard. They may choose to compete, cooperate, or coopete to conform to the dominant standard or to destabilize and propose a new standard. In the contribution, we show research on coopetition to conform and destabilize a standard.

The chapter is organized into two parts encapsulating these three phases. The first part presents the research on coopetition before standard emergence. We show how firms foster standardization in order to innovate, how setting standards is required for market innovation, why market stakeholders demand standards, and how a failure in coopetition slows innovation. The second part exposes research on coopetition during the standardization process and after standard emergence. We describe the de facto and de jure processes and show how coopetition differs in market or institutional contexts. We then present firms’ strategies to conform or contest a standard and provide a new perspective considering standards to be a driver of coopetition.

Coopetition to foster standard emergence: The determining role of innovation

Research on coopetition has largely investigated how coopetition drives innovation. Research on standardization builds on the idea that innovation requires standardization. Standardization is required to commercialize a new product and create a new market; we present research showing that coopetition is in the best interests of standardization. To explore the relevance of coopetition to establishing new standards for creating a new market, we first propose analyzing the connection between innovation and standardization. We then discuss the two main mechanisms of standard emergence relative to competition and cooperation and introduce coopetition as a new perspective on standard-setting. The third section reveals the advantages and limits of coopetition as a relational strategy that seeks to establish standards that serve market innovation.

The relation between innovation and standardization is widely debated in the standardization literature. Standardization scholars are challenging the traditional perception of standards as obstructing innovation through their presentation of the “technology freezing” characteristic (Zoo et al., 2017). Considering the “innovation-standardization nexus,” the authors recently reported different reasons that standardization can foster innovation. Initially, standards and standardization contribute to the creation and diffusion of innovation (Goluchowicz & Blind, 2011; Tassey, 2000). Standardization drives innovation when new standards impose requirements that lead firms to innovate. For example, the emission standards that regulate the car industry foster innovation to reduce CO2 emissions. These regulatory standards specify the maximum emission rate authorized and plan the progressive reduction of CO2 emissions over several years. The companies can anticipate and prepare to comply with the requirements; otherwise, they could be excluded from the market. Second, standardization facilitates the diffusion of innovation. Standards are a set of technical specifications and thus constitute a shared basis of advanced technological knowledge, condensed into an easily transferrable form for widespread adoption (Allen & Sriram, 2000). Standardization as a process of standard development offers critical opportunities to direct the focus of an emerging technology, which in turn facilitates the diffusion of innovation by increasing both economies of scale and network benefits (Swann, 2000). Blind (2002) also recognizes the significance of standardization as a diffusion channel of innovation. Third, standardization is considered an increasingly important tool to drive innovation that is often laden with complexity and uncertainty because of its ability to connect and coordinate the innovation process. Notably, Blind & Gauch (2009) show how different types of standards facilitate innovation in particular stages of the R&D process. Blind (2013) identifies four types of standards (variety reduction, minimum quality, compatibility, and information) and their effects on innovation. Variety reduction standards, by defining the specifications of products and services and reducing the variety of products, help firms attain economies of scale and critical mass for market success. Minimum-quality standards reduce the uncertainty and risks originating from the circulation of inferior goods in the market, thus building consumer trust in new, innovative products. This outcome leads to reduced transaction costs for a broader diffusion. Compatibility standards are central to achieving network externalities and avoiding lock-ins in old technologies. Information standards, by providing a common understanding of technological knowledge among standards users, reduce transaction costs and facilitate trade. In sum, the current body of literature recognizes a positive interplay between innovation and standardization (Zoo et al., 2017). This interplay can be specified as two specific mechanisms according to the competitive nature of the standardization process.

Coopetition as a strategy to foster innovation through standardization

Below, we specifically examine the advantages and limits of coopetition as a strategy to foster the development of a new product or market through standardization. We expose four case analyses in which coopetition succeeded or failed to set new standards for commercializing new products.

Coopetition as a required strategy to set standards for creating new markets

Coopetition constitutes a performant strategy to establish the institutional rules for creating a new market. Based on 300 questionnaires on standardization and interviews of the marketing directors of firms participating in the French Standard Development Organization (SDO), we empirically validated that companies chose to engage in normalization because they clearly identified the ability of norms to create new markets. We observed that leaders and innovators in the technology sector are more active in the development of standards. These businesses must cooperate because consensus is needed to establish institutional standards; at the same time, however, they compete with each other to promote their own technology and support the standard that is most beneficial to them. Thus, coopetition to establish norms appears to be a required phase of entrepreneurship strategy (Mione, 2009).

Coopetition as a strategy required by market stakeholders

A case analysis of the geosynthetics market, observing the innovation and standardization phases, showed the performance of coopetition in the early phase of development and a slowdown in the later phases of development (Mione, 2015). In this case analysis, the collective development of the market coexists with the individual interest of benefiting from the expertise of the different specialists. Cooperating facilitates competition as competitors obtain information on technical expertise; however, at that point in time, the development of the pie appears to be of greater importance than protecting the piece of the pie. Specifically, the development of the pie pre-empts the development of any part of the pie. For geosynthetics, the situation is more sensitive. Coopetition is not merely a market-development strategy; it is required by the users. Public works enterprises require reliable technical references, particularly with respect to new technology. Technical standards are these references, which are reliable precisely because they are the result of a process that involves all the players in the market. Therefore, coopetition can be a necessity for market development. For example, to develop an electronic document format, the market demanded de jure standards, and Microsoft was therefore required to engage in coopetition (Yami et al., 2015).

Coopetition failure as a breaker of innovation

The development of standards were fruitful to build new markets, but once markets were created, the development of standards became conflictual. The resurgence of competition in standardization drastically reduced the number of standards issued. When the market is developed, positions are defended. Each market has its own representation, conception, and methods. The interest in developing the global market is less collectively shared.

Coopetition is a complex strategy because it requires competitors to share a common vision of market development. A case analysis exploring standardization strategies to develop nonconventional material (bamboo and dried earth) for the Brazilian market (Mione, 2014, 2015) reported the same findings. Again, the stakeholders confirmed the need for standards to reduce information asymmetry and support market structures. In this case, we observed a failure in the development of common standards, which is due to the inability to agree upon a common vision. Social neoinstitutionalists show that battles over standards are based on wars between values, emphasizing the degree to which the contribution to the definition of standards constitutes the exercise of power to support specific representations.

We identified conflicts between contradictory registers of legitimacy (Suchman, 1995) in different situations of standard emergence (non-conventional material; Mione, 2014, 2015): the sustainable management of forests (Mione & Leroy, 2013) and geosynthetics (Mione, 2009, 2015). Because standardization requires legitimacy, coopetition in standardization constitutes a specific challenge; competition between values is barely addressed or resolved and generally leads to the failure of standardization. However, we can observe cases where coopetition enabled surpassing political opposition; this occurred when Microsoft achieved ISO standards as a result of its subtle management of coopetition (Yami et al., 2015).

Coopetition within the standardization process

Two modes of standard emergence: De facto and de jure standardization

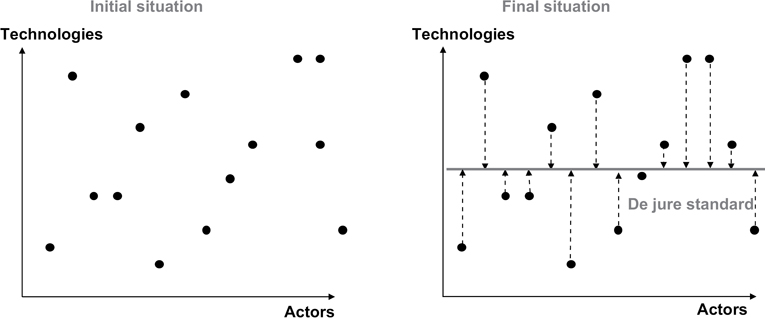

The traditional literature on standardization states that competition and cooperation produce different types of standards. Specifically, standards are set through two main mechanisms: markets and committees (Farrell & Saloner, 1988; Funk & Methe. 2001). In this view, market-issued standards, also called “de facto” standards, emerge through competition, whereas committee-issued standards, also called “de jure” standards, are produced by the convergence of stakeholders through negotiation. Figures 11.2 and 11.3 below represent the two processes by which standards emerge.

A de facto standard spontaneously emerges from the market. Most firms adopt a technology that becomes a standard. A de jure standard is voluntarily defined in committees at the non-market level; this occurs when there is a need to create institutional rules to organize the market. SDOs gather a market’s stakeholders and impose formal and consensual rules to establish formal standards. The consensual dimension requires at least enough cooperation to gather around a table and participate in the standard development.

However, this traditional view has been challenged by the introduction of a more complex understanding of the competitive relationship. Below, we show how the literature on de facto and de jure standards has progressively considered the hybrid nature of a competitive relationship and the introduction of coopetition.

Coopetition in de facto and de jure standardization

Competition is the dominant relational mode in de facto standardization. Much of the standardization literature has focused on de facto standards (Gawer & Cusumano, 2002; Schilling, 1998; Shapiro & Varian, 1999; Sheremata, 2004) and has demonstrated the aggressiveness of competition. In this context, the literature has described the “winner-takes-all” principle (Shapiro & Varian, 1999), which signifies that war is fatal to the loser. He is destroyed and disappears, which is a relatively scarce occurrence in traditional competition. Network effects explain this phenomenon, which provides a definite advantage to the survivor and assigns all benefits to the dominant player. Although there are certain limitations to this standardization movement, certain wars and battles remain famous because of the fatality issue (VHS/Betamax). However, a standards war requires allies, and Shapiro and Varian (1999) have long established that firms must ally with competitors to win a standards battle. This situation has been described as a coalition or a strategic alliance rather than as coopetition. However, Garud et al. (2002), who studied the standardization of Java sponsored by Sun Microsystems, noted that this process involved “coopetition.” Gnyawali and Park (2011) referred specifically to coopetition in the context of innovation in the video industry. Direct references to coopetition to describe specific standards wars have recently occurred in various contexts, such as accounting (Fernandez & Pierrot, 2016), traceability (Allamano-Kessler et al., 2016) and the video industry (Allamano-Kessler & Mione, 2017). The de jure context offers more opportunities to identify coopetition because cooperation is clearly imposed by third actors in institutional contexts.

De jure standardization creates conditions in which competitors meet and collaborate. The research has examined how SDOs can resolve coordination problems. Comparing the relative performance of market competition versus committee coordination in forming standards, Farrell & Saloner (1988) find that although committees take longer to achieve a consensus than markets, committees tend to do better. Farrell (1996) emphasizes the advantage of achieving consensus and the benefits of avoiding a costly standards war. Other scholarship in this stream highlights firms’ systematic venue preferences (Lehr, 1992; Lerner & Tirole, 2006) and the role that multiple competing standards organizations play in coordinating rule development (Genschel, 1997). Another stream of research has observed competitive relations during the standardization process. Oshri & Weeber (2006) noted that the two relational modes (competition and cooperation) can coexist at different stages of the development of a de facto or de jure standard. The researchers showed that at each stage of the development of a standard, actors choose among pure relational modes, cooperation or competition, or different levels of the hybrid mode. This approach had previously been developed in numerous works (Axelrod et al., 1995; De Laat, 1999) and shows the interest in deepening the knowledge of relational modes (cooperation and competition as “pure mode” and coopetition as “hybrid mode”) at the emergence of a formal standard. Observing the de jure process, Yami et al. (2015) showed the subtle management of coopetition implemented by Microsoft for a document format. Microsoft alternated different relational modes in the coopetition situation within the AFNOR (French: SDO) and used coopetition as a means to maintain market control.

Research also shows that participating in committees develops the social capital of the engineers serving in these forums (Dokko & Rosenkopf, 2010; Riillo, 2013) and provides opportunities to make alliances (Rosenkopf et al., 2001; Benmeziane et Mione, 2015; Mione and Benmeziane, 2017; Waguespack & Fleming, 2009). Thus, de jure standardization creates the conditions for installing coopetition as a situation (Mione, 2009). In this context, coopetition constitutes a strategy to gain influence and control in the standard definition (Benzemiane & Mione, 2016). Realizing a quantitative study on data gathered from the European Cooperation for Space Standardization (ECSS) over the 1999–2014 period, Benmeziane & Mione (2016) show how coopetition is a performant strategy to obtain a strategic position within the SDO and to occupy a position to influence standard-shaping.

Coopetition to destabilize a dominant standard

Coopetition may serve strategies to destabilize a standard. We observe many situations where firms or organizations, instead of adopting the standard, choose to create a rival one. In sustainable management, the emergence and development of the Forest Stewarship Council (FSC) standard on sustainable forest management triggered the development of a rival standard (PEFC, first named Pan European Forest Certification and then called Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification) (Mione & Leroy, 2013). In the context of electronic document formats, Microsoft would not conform to the ISO open-format standard and engaged in the ISO standardization process to define a new standard based on its own draft, OOXML (Yami et al., 2015). American and European universities have designed their own new ranking to destabilize the dominant Shanghai ranking. In these different situations, firms and organizations contest the order settled by the standard and offer an alternative. The choice not to conform and to engage in competition is based on three reasons. The first is that conforming adds weight to the standard; indeed, network effects apply to the standard (Mione, 2009). This is not only the case for interface standards that enable technical compatibility between networks. We support the idea that standards gain their structuring force on the market due to the network externality benefits (Katz & Shapiro, 1985). Only when they constitute a common reference will standards be an advantage for their users. The success of the ISO 9000 standard relates to this effect; firms choose this certification because of its widespread adoption and the more adopters, the more attraction to new users (Mione, 2009). For this reason, firms may refuse to conform to a specific standard because they do not want to contribute to its development through their own adoption and because to some extent this choice may influence followers. Creating, developing, and sustaining a rival standard is an attempt to interrupt the network effect that beneficiates to the dominant standard.

Second, firms and organizations may refuse to conform to a standard because they do not adhere to its value. Standards, however technical, define the behavioral rule that allows respecting values (Mione, 2009). In the sustainable management certification (Mione & Leroy, 2013), in geosynthetics (Mione, 2009), and for bamboos (Mione, 2015), we showed that rivals used different legitimacy registries, and that the battle of standards revealed a conflict between values.

Third, the decision not to conform and to instead propose an alternative may be due to the decision to control and shape instead of adapt to environment. Defining the “new game strategy,” Buaron (1981: 27–8) is explicit about the advantage of shaping the environment:

The successfull new-game strategist measures every strategic move by its impact on his relative competitive position. He knows that the first rule of gaining or sustaining an advantage over the competitors is to control the conditions of the game … So rather than waiting for the battle to come to him, he aims to choose the field and determine the manner and timing of the conflict. Continually weighing his company’s strengths, vulnerabilities and resources against the competition, he is prepared to decide where to compete, how to compete and when to compete.

(Buaron, 1981: 27–8)

More recently, D’Aveni (1995) showed that strategy is necessarily proactive, creating and perturbing the environment instead of admitting and adapting to it. Coopetition is required to install a standard battle and decide to settle new rules because standard definition requires allies. In this situation, the destabilization of the precedent order and the building of a new environment constitutes a driver for coopetition.

Standardization as a driver of coopetition

Standardization may also constitute an external driver of coopetition. In previous sections, we have reviewed research on standard-setting as a driver of coopetition. Another perspective explores standards as an external driver to coopetition. This is the case when firms decide to coopete in order to gain access to resources enabling them to conform to the standard. In an exploratory approach, Laifa and Mione (2012) considered how regulatory emission standards led firms to coopetition.

Bengtsson and Raza-Ullah (2016) have recently considered different levels of drivers triggering coopetition. The Gnyawali and Park (2009) model comprises the structuring foundation for the examination of drivers. This model offers the first dynamic coopetition conceptualization to feature the role of the drivers and integrates industry, organizational, and dyadic relational factors. Standards do not appear in this model. However, standards requirements may induce technological convergence and high R&D costs, which are elements beyond the three elements that describe the industry-level factors. New perspectives show that standard requirements impose new conditions that either authorize or forbid the product’s entry into the market, thus exerting environmental pressure that favors coopetition. The institutional environment has been identified as a driver of coopetition (Mariani, 2007). The perspective of coopetition being either forced on or constrained by the environment is developed by Czakon and Czernek (2016), who add institutional, competitive, and customer pressure as exogenous drivers of coopetition. Finally, Bengtsson and Raza-Ullah (2016) proposed the inclusion of industrial characteristics, technological demands, and influential stakeholders as external drivers. We suggest considering standards as an external driver for coopetition.

However, standard-setting also constitutes a strategy that can drive coopetition. As noted by Overmars (2016), the intention to establish industry standards may induce coopetition because access to partners’ broad capabilities can come in very handy when competing to win new product and technology battles (Hamel et al., 1989). Therefore, Overmars (2016) observes that one reason that companies can decide to collaborate with competitors is arguably their willingness to set industry standards (Overmars, 2016). In our view, standardization constitutes a driver of coopetition in two distinct situations: when competitors ally to settle a new standard and when competitors cooperate to share resources and innovate in order to be able to satisfy the requirements imposed by a new standard.

Conclusion

These insights lead to several recommendations for new research in this field. The first is to advocate the use of the coopetition concept to better understand standardization and firms’ perspectives on their engagement in standardization. We suggest that standardization constitutes an ideal locus to explore coopetition from a strategic and managerial perspective. In standardization, coopetition is not exclusively a matter of simultaneous competition and cooperation on different levels, such as the market and non-market levels. Battling and partnership are simultaneously based on the standard definition. Partners fight and, at the same time, attempt to establish consensus; this is why the negotiation process is one emblematic locus of coopetition. In addition, de facto and de jure standards should not be differentiated as competitive or cooperative. De facto standardization requires collaboration and committee-issued standards also compete within the standardization process and in the market as soon as they are published; only through market competition will they gain dominance. Also, standardization can be seen as a pre-competition phase. However, in the research presented here, both phenomena, i.e., innovation and standardization, were intertwined. Finally, the standardization process is complex and requires overcoming apparent paradoxes. The concept of coopetition throws new light on the standardization process because it reconciles the antagonism between competition and cooperation. Such lenses are now required to better understand the complexity of the standardization process. We suggest starting with coopetition as a method of selecting standards that enable market innovation and, more generally, a market’s smooth functioning.

References

Allamano-Kessler, R. & Mione, A. (2017). Coopetition to win a format battle; coo-standardization in the video industry. 22nd EURAS annual conference, 28–30 June, Berlin.

Allamano-Kessler, R., Mione, A., & Larroque, L. (2016). Fatal competition, peaceful coexistence or active coopetition between traceability standards in the distribution channel? 21st EURAS annual conference, June 29–July 1, Montpellier.

Allen, R. H. & Sriram, R. D. (2000). The role of standards in innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 64(2–3): 171–181.

Axelrod, R., Mitchell, W., Thomas, R. E., Bennett, D. S., & Bruderer, E. (1995). Coalition formation in standard-setting alliances. Management Science, 41(9), 1493–1508.

Bengtsson, M. & Raza-Ullah, T. (2016). A systematic review of research on coopetition: Toward a systematic level of understanding. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 23–39.

Benmeziane, K. & Mione, A (2016). Coopetition to gain influence, leadership and control on Standard Setting Organization. 21st EURAS annual conference, June 29–July 1, Montpellier.

Benzemiane, K. & Mione, A. (2015). Participating in standard setting organizations to build equity strategic alliances. 20th EURAS Annual Conference, June 22–24, Copenhagen.

Blind, K. (2002). Driving forces for standardization at standardization development organizations. Applied Economics, 34, 1985–1998.

Blind, K. & Gauch, S. (2009). Research and standardisation in nanotechnology: evidence from Germany. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 34, 320–342.

Blind, K. (2013). The impact of standardization and standards on innovation. Compendium of evidence on innovation policy intervention. Nesta Working Paper Series (13/15), Manchester.

Buaron, R. (1981). New game strategy. The Mac Kinsey Quarterly, 12 (spring): 24–40.

Czakon, W. & Czernek, K. (2016). The role of trust-building mechanisms in entering network coopetition: The case of tourism networks in Poland. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 64–74.

D’Aveni, R. (1995). Hypercompétition. Paris: Vuibert.

David, P. A. & Greenstein S. (1990). The Economics of Compatibility standards: An Introduction to Recent Research. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, June, Stanford University.

De Laat, P. B. (1999). Systemic innovation and the virtues of going virtual: The case of the digital video Disc. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 11(2), 159–180

Dokko, G. & Rosenkopf, L. (2010). Social capital for hire? Mobility of technical professionals and firm influence in wireless standards committees. Organization Science, 21(3), 677–695.

Farrell, J. (1996). Choosing the rules for formal standardization. Working Paper, University of California at Berkeley. https://eml.berkeley.edu/~farrell/ftp/choosing.pdf.

Farrell, J. & Saloner, G. (1988). Coordination through committees and markets. Rand Journal of Economics, 19(2), 235–252.

Fernandez, A.-S. & Pierrot, F. (2016). The consequences of a third party decision on coopetition strategies; the case of the International Accounting Standard-Setting Process. International Journal of Standardization Research, 14(2), 1–19.

Funk, J. L. & Methe, D. T. (2001), Market and committee-based mechanisms in the creation and diffusion of global industry standards: the case of mobile communication. Research Policy, 30, 589–610.

Garud R., Jain S. & Kumaraswamy A. (2002). Orchestrating institutional process for technology sponsorship: The case of Sun Microsystems and Java. Academy of Management Journal, 45 (1), 196–214.

Gawer, A. & Cusumano, M. (2002). Platform Leadership: How Intel, Microsoft, and Cisco Drive Industry Innovation. Harvard: Harvard Business School Press.

Genschel, P. (1997). How fragmentation can improve co-ordination: Setting standards in international telecommunications. Organization Studies, 18(4), 603–622.

Gnyawali, D. & Park, B. (2009). Co-opetition and technological innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises: A multilevel conceptual model. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(3), 308–330.

Gnyawali, D. & Park B. J. (2011). Coopetition between giants: collaboration with competitors for technological innovation. Research Policy, 40(5), 650–663.

Goluchowicz, K. & Blind, K. (2011). Identification of future fields of standardisation: an explorative good idea? An example in practice. British Journal of Management, 23 (4), 532–560.

Hamel, G., Doz, Y., & Prahalad, C. K. (1989). Collaborate with your competitors and win. Harvard Business Review, January–February, 133–139.

ISO (International Standard Organization, also called International Organisation for Standardization). (2016). Annual report www.iso.org/publication/PUB100385.html.

Katz, M. & Shapiro, C. (1985). Network externalities competition and compatibility. American Economic Review, 75(3): 424–440.

Laifa, R. & Mione, A. (2012). Technical standards as drivers of coopetition, EIASM Workshop on coopetition strategy, September 12–14, Katowice, Poland.

Lehr, W. (1992). The political economies of voluntary standard setting. PhD Thesis, Stanford University.

Lerner, J. & Tirole, J. (2006). A model of forum shopping. American Economy Review, 96(4), 1091–1113.

Mariani, M. (2007). Coopetition as an emergent strategy: empirical evidence from an Italian consortium of opera house. International Studies of Management and Organization, 37(2), 87–126.

Mione A. (2009). When entrepreneurship requires coopetition: The need for norms to create a market. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 8(1), 92–109.

Mione A. (2014). Standard questions in developing a new market; the lessons from non-conventional materials. Key Engineering materials. TransTech Publications, 600, 413–418.

Mione A. (2015). The value of intangibles in situation of innovation; Questions raised by the standards’ case. Journal of Innovation, Economics and Management, 17(2), 49–68.

Mione A. & Leroy M. (2013). Décisions stratégiques dans la rivalité entre standards de qualité: le cas de la certification forestière. Management International, 17(2), 84–104.

Mione, A. & Benmeziane, K. (2017). Relational strategies in standard setting organizations; when alliances in standard shaping leads to alliances on the market. 17th EURAM annual conference, 21–24 June, Glasgow.

Oshri, I. & Weeber, C. (2006). Cooperation and competition standards-setting activities in the digitization era: The case of wireless information devices. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 18(2), 265–283.

Overmars, C. (2016). Factors that drive coopetition and exploration of potential supply-based drivers to coopetition. University of Twente, 1st July.

Riillo, C. (2013). Profiles and motivations of standardization players. International Journal of IT Standard and Standardization, 11(2), 17–33.

Rosenkopf, L., Metiu, A., & George, V. (2001). From the bottom up? Technical committee activity and alliance formation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(4), 748–772.

Schilling, M. (1998). Technological lockout: an integrative model of the economic and strategic factors driving technology success and failure. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 267–284.

Shapiro, C. & Varian, H. R. (1999). The art of standards war. California Management Review, 41(2), 8–32.

Sheremata, W. A. (2004). Competing through innovation in network markets: strategies for challengers. Academy of Management Review, 29, 359–377.

Suchman, M. (1995). Managing legitimacy: strategic and institutional approaches, Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610.

Swann, G. M. P. (2000). The Economics of Standardization: Final Report for Standards and Technical Regulations Directorate. Department of Trade and Industry.

Tassey, G. (2000). Standardization in technology-based markets. Research Policy, (29), 587–602.

Waguespack, D. M. & Fleming, L. (2009). Scanning the commons? Evidence on the benefits to startups of participation in open standards development. Management Science, 55 (2), 210–223.

Yami S., Chappert H., & Mione A. (2015). Strategic Relational sequences; Microsoft’s coopetitive game in the OOXML standardization process. M@n@gement, 5(18), 330–356.

Zoo, H., de Vries H. J., & Lee, H. (2017). Interplay of innovation and standardization: Exploring the relevance in developing countries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change (118), 334–348.