The river

where you set

your foot just now

is gone –

those waters giving way to this,

now this.

Heraclitus, Ancient Greek Philosopher

Enough of gurus! Let’s look at the bigger picture. In this chapter, we will show that long-term societal and economic history, not unlike living organisms, is a constantly repeating pattern of creation, growth, decline, destruction, and recreation. This cycle of creative destruction plays out endlessly at many levels: from individual companies to whole industries, from single sectors to entire national economies.

Yet we live in the short term. And we do business on even shorter time scales, which – as we saw in the case of the stock market – presents us with a lot of random fluctuations and little or no patterns. Despite what the management gurus try to tell us, history just doesn’t repeat itself at the level of individual firms or business units. As the Greek philosopher Heraclitus wisely said, you can’t step into the same river twice. Even if the water is the same depth and temperature as before, even if the pattern and the currents look constant, even if no stone on the river bed has moved, the water itself is not the same. It’s constantly churning and changing. But the long term is a completely different story with creative destruction driving societal and economic progress. Like the river, it follows the same inexorable course with few changes, at least most of the time.

Far away from ancient Greek wisdom and the vast panorama of history, managing a business in the twenty-first century is – like managing our health or personal finances – fraught with all the uncertainty we’ve seen in previous chapters. But there are critical differences. Our bodies are highly complex, but our choices in managing them are confined. Running a company offers more options, even more than investing. Investors are usually blessed with the opportunity to withdraw their funds at will if their original decision starts to look bad – a luxury that few executives can afford. No, managers are stuck in the here and now of business and saddled with the consequences of decisions, both good and bad, from the past.

If we raise our sights from the narrow concerns of running a single company to the broader sweep of an entire industry, we do, however, start to learn some lessons from history. Back in 1932, the real price of copper (in constant 2007 dollars) was $1.97. By 1974 it was $7.26 (again in 2007 dollars), an almost four-fold increase. The main reason for this huge increase was the demand from the growing network of copper telephone wires that encircled the globe. But it was also because an industry cartel was controlling the supply.

Economists tell us that high profits are supposed to encourage additional capacity, with new facilities opening to increase production and meet rising demand. The people who run cartels, however, love their rising profits, so why would they reduce them? They work to defy economic principles and to maintain the status quo. That’s exactly what the copper cartel did, restricting the number of mines and factories to constrain supply and maximize the profits of the copper companies – pushing the price up even further.

But high profits attracted competition from outside the copper industry. From the 1950s onward, scientists started exploring the possibilities of fiber optics. But the theoretical problems weren’t solved until 1970, when three scientists, Robert Maurer, Donald Keck, and Peter Schultz, found a way of using fused silica (a material of extreme purity with a high melting point and low refractive index) to transmit more than 65,000 times more information than copper wires – and with much better transmission quality.

Fiber optics transformed the telecoms industry and heralded the coming of the information age. Since the 1980s many million kilometers of telecommunications lines have been installed worldwide and nearly all of them involved fused silica. Today, technical improvements mean that a single hair’s-breadth fiber is enough to carry tens of thousands of phone calls, transmitting more than ten billion digital bits per second. That’s equivalent to 20,000 books the size of this one.

Poor old copper. In less than a decade, the vast superiority of fiber optics made copper wire virtually obsolete. Demand for the metal collapsed, most copper companies went bankrupt and employment in the industry fell by 70% in some countries. To save itself from liquidation, Anaconda, once the fourth largest company in the world, was sold to ARCO in 1977. Prices continued to fall, and ARCO ceased all copper-mining activities in 1983. C. Jay Parkinson, the former president of Anaconda, must have regretted what he said in 1968: “This company will still be going strong 100 and even 500 years from now.” Not that anyone can blame him. At that time, the copper cartel was controlling the market, and prices – not to mention profits – had been on the rise for over thirty-five years. Parkinson had underestimated the incredible power of the market to drive prices down (more about this soon) and thus wreak revenge on the few companies that previously controlled the market. It’s small consolation that plumbers still like to use copper.

The key to understanding this tragic tale of an industry that got its just desserts lies in the fact that Maurer, Keck, and Schultz came from another world entirely. They worked for Corning Glass, a company that had no connections whatsoever with the telecommunications industry, let alone the copper business. It produced ordinary, everyday glass products. In other words, the threat to copper came from outside and, with absolutely no warning, took an entire industry down. Corning Glass didn’t care if the copper industry was destroyed. On the contrary: the faster the destruction, the bigger its own revenues and profits.

Parkinson and his peers in the industry should have known it would happen sooner or later. But they only cared for their short-term profits, not to mention their huge salaries and hefty bonuses (usually increasing even faster than their companies’ revenues). Any economics undergraduate could have told them that competition to an industry all too often comes from outside. Over-inflated profits are very attractive, and outsiders don’t worry about oversupply reducing prices. Nor do they give a damn whether an industry collapses. As it happens, neither should we (though we should retain the nugget of economic wisdom that the story of copper offers). No doubt shareholders and employees suffered, but society as a whole gained immensely. If we’d stuck with copper, there’d be no internet, no e-mail, no free calls from Skype, no Google. One industry collapsed, but others rose phoenix-like in its place, creating new jobs and profits for new shareholders – bringing people together across oceans and time zones at little or no extra cost. Technologically, the world is a better place for the demise of copper wires.

This true story of a metal that lost its luster brings us back to the concept of “creative destruction” that we mentioned earlier. Like most good ideas, there’s nothing new about it. The term was coined by the economist Schumpeter in his classic 1942 book, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. He defined creative destruction as the “process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.”1 Schumpeter believed that entrepreneurs are the people who make things happen in the economy, by transforming innovative ideas into practical opportunities. They introduce new products or services and reduce costs by improving efficiency. In so doing, they overturn old regimes of market leadership and make old products or services obsolete. According to Schumpeter, the opposite of creative destruction is lack of progress and stagnation – not only in the economy but also in society as a whole. The story of copper is a perfect example.

As Benjamin Franklin notoriously observed: “In this world nothing is certain but death and taxes.” The same is true for companies. As we saw in the previous chapter, they typically don’t last long. Even big multinationals rarely make it beyond the age of fifty, so there’s little hope for smaller, local firms and even less for start-ups. By all means, executives can opt to manage for long-term survival, but not without adversely affecting financial performance. This is not simply an empirical fact, but a logical necessity: the safer you play, the fewer risks you take . . . and the lower the potential gains. This is precisely what we saw in chapters 4 and 5: higher returns go hand-in-hand with greater investment risk. The same principle holds in the business world.

As the fall of copper illustrates, it’s no different on the scale of entire industries and economic sectors. In their day, railways, steel, and motor manufacturing all boomed and then bust, or at least slipped into mediocrity. Since then, the entire sector of manufacturing has declined, while the information and communications technologies are riding high. Did we see these changes coming? Initially, no. Then we got our timing wrong in a frenzy of over-reaction. In the process, we created a bubble that finally burst at the very beginning of this century. Nearly half a decade later, the good times were back for the information business, but unfortunately these times did not last long as a bigger bubble emerged and brought about the largest post-war recession. It’s as difficult to predict when an entire economic sector or industry will take off and slow down as it is for individual companies.

These days, everyone loves Google. Internet users, investors, journalists, and business school professors alike, we all revel in its tremendous success – and the benefits this brings us. With Google’s market value of more than $220 billion toward the end of 2007, the power of internet search is apparent for all to see. Yet Google historians tell us it wasn’t always this way. As late as the end of the 1990s, no one in Silicon Valley was interested in buying the company with its unique search technology. The asking price from its founders was just $1.6 million.

Excite, a one-time competitor of Yahoo, came closest with a bid of $750,000. But Yahoo, the now-defunct Infoseek, and a whole bunch of venture capitalists didn’t even bother making an offer. The Valley buzzword of the day was “portal” not “search.” Larry Page, one of Google’s two founders, recalls: “We probably would have licensed it if someone gave us the money . . . but they were not interested in search.” He adds dryly, “They did have horoscopes, though.”2

But even Page and his partners didn’t predict the Google phenomenon (as the attempt to sell proves). No one had the slightest inkling of the vast practical and financial value of its search technology. And it’s lucky for the founders that they didn’t. If Google had sold for $1.6 million at the end of the 1990s there’d have been no stock market flotation in 2004 and no $220 billion-worth of shares in 2007. Google is no isolated case. One of the best books on the subject of commercial success stories, Nayak and Ketteringham’s 1986 bestseller Break-Throughs, concludes that, if there’s one thing all business breakthroughs have in common – it’s the surprise factor.3 No one foresees their occurrence, let alone their immense commercial consequences. If we can’t spot big breakthroughs before they happen, what hope is there of predicting smaller business successes?

Apple is another prime example, beloved by the business press. Its innovative products have revolutionized the telecom and music businesses and brought huge gains to its shareholders (its share price went from $3.3 in 1997 to more than $160 twelve years later). Going back in time, without Apple there’d be no Windows and today’s creative industries would look very different. Back in 2003, however, the price of an Apple share was only $7 and Apple’s CEO, Steve Jobs, is rumored to have given up stock options that only four years later (with the share price up to $93) would have made him $2.6 billion richer.4 Arguably the most visionary man in business, Jobs couldn’t see the future of the infant iPod and its creative-destructive potential.

Apple and Google are still creating and destroying as we write. The fearful have coined the three-letter acronym DBG (Death By Google) to explain the way in which small changes to the search function slightly affect the order in which sites appear on the results pages. This can send the revenues of the companies who own those sites soaring or plummeting, even forcing some into bankruptcy. The power of Google is generated by people like us, the vast number of visitors who use it to search the web daily free of charge. The business model of providing this and other services for no payment is another aspect of creative destruction with far-reaching consequences. It subverts traditional business paradigms and raises a red flag to those whose livelihoods are threatened. Apple has had a similar effect – even on its comrades in the digital music revolution, let alone the old-guard record companies. By the middle of 2007, the iPod had an 82% market share in the US. Now more recent projects, such as iPhone and iTV as well as Google’s new mobile phone, are giving sleepless nights to executives in the telecom and TV industries.

Meanwhile, Jobs, Page, and the Apple and Google elite enjoy sweet dreams. Perhaps, however, on some dark and stormy nights the troubling memory of Ken Olsen flits across their collective unconscious. In 1986 he was the founder and chairman of the great Digital Equipment. The cover of Fortune magazine hailed him as “America’s Most Successful Entrepreneur”. And no wonder. At that time, Digital had managed to break IBM’s monopoly by introducing smaller, cheaper, and more user-friendly computers. Revenues were growing at close to 40% a year, while profits were growing at more than 20%. But he was a player in a much bigger industry story.

Just over ten years earlier, a small start-up had launched the idea of the “personal” computer. A garage partnership between Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs (yes, him again) had a small but enthusiastic following for their Apple I and II models. As their sales increased, IBM decided to get a piece of the action and introduced its own product in 1981. By October 1986, when Ken Olsen’s face appeared to the world on the cover of Fortune, new customers and companies, such as Compaq, were jumping on the personal-computer bandwagon. IBM and Apple Computer had competition. And Digital had a low-cost, easy-to-use product that screamed out competitive advantage.

However, back in 1987, Olsen didn’t believe in personal computers. He’s credited with the by-now infamous words: “There is no reason for any individual to have a computer in their home.” Whether or not he actually made the fateful statement, he expressed it in his subsequent strategy of not entering the PC industry in time. In the three years leading up to 1995, Digital lost close to $2 billion and only managed to limp on until 1998 by making drastic cuts in cost and head count. Finally, it was obliged to “merge” with (or more accurately “sell itself” to) Compaq.

All this time, the world’s addiction to the personal computer was growing stronger and stronger. By April 2002 sales hit the one billion mark. Predictions (for what they’re worth) indicated that another billion would be sold by 2008. “America’s Most Successful Entrepreneur” had clearly seen the trend toward smaller, cheaper, friendlier computers, but he hadn’t taken his insight to the logical conclusion that would – in just a few years – allow us to have powerful computers within our mobile phones. As for the journalists who hailed him as a business super-hero, they soon moved on to new faces. The Swede Percy Barnevik, CEO of ABB, was greeted as the “Jack Welch of Europe.” Until 2001, that is, when he became a media villain overnight. Since then, others have come . . . and gone: Lee Iacocca of Chrysler, Bob Nardelli of Home Depot, and, more recently, Carly Fiorina of Hewlett-Packard.

So one day, it will be Google and Apple managers having the nightmares. Their pre-eminence will be creatively destroyed (or at least reduced to mediocrity) by new strategic or technological ideas. A new generation of innovation heroes will appear on the magazine covers. But that’s as far as our forecast can go. When and how it will happen remains uncertain. And that’s a tough reality to confront – not just for Google and Apple, but for the whole unpredictable world of business. Don’t let it get you down, though. The dark clouds of uncertainty don’t just cast shadows of danger. They also have silver linings of opportunity. But in order to grasp those opportunities, it’s important to understand history and the fact that accepting new possibilities might mean destroying old ones. Copper wires can’t coexist with fiber optic cables, as the latter are much more cost-effective and billions of times faster and greatly more cost-effective than the former.

What’s around the corner for the company you run or work for? Are you at the total mercy of creative destruction? Or is there something you can do to save the day? As in previous chapters, we’re convinced that dispelling the illusion of control can be fundamental. If leaders of the copper industry had abandoned their attempt to control by cartel, paradoxically, they could have shaped their own destiny for a little longer. Instead, their greedily inflated profits offered rich pickings for unexpected competitors.

We’re no gurus, however. We realize that there’s much, much more to doing business than triumphing over the illusion of control. Managing isn’t like investing, where we were able to offer specific advice for general success. Instead, business is characterized by its complexity – which adds further uncertainty to the unpredictability that creative destruction brings. At the same time, feedback comes infrequently and is hard to evaluate. It’s difficult (if not impossible) to assess past performance and to attribute outcomes to specific decisions, actions or people. Of course, executives congratulate themselves when things go well and blame bad luck or others when things go badly. They also tend to surround themselves with people who echo these conclusions. That’s just human nature. But it only compounds the uncertainty and unreliability of the feedback. Worse still, it blinds them to looming creative destruction. And, as Schumpeter told us many decades ago, creative destruction is one of the few certainties of business. And it’s not just inevitable – it’s beneficial, for society as a whole, that is!

So, in the rest of this chapter, we advocate two strategies based on accepting the inescapability of creative destruction. The first involves understanding the factors that produce creative destruction, so as not to be finished off by it (or at least to delay it as much as possible). The second is more radical. It consists of harnessing the power of creative destruction, instead of giving in to it. Neither strategy promises certainty or a panacea for all other business problems, of course. But they’re both better than the third choice – which is to sit back and wait to be engulfed.

In chapter 5, we dabbled in the stock market and found that the short and medium term were all about flux and unpredictability. However, we also discovered that – in the long run – the only way was up. It turns out that there are similar long-term trends in economics, which have implications for all managers. So, for a second time in this book, we’re ready to make some predictions for the long run.

They’ve been going down since 1800, in fact, when the effects of the industrial revolution started to kick in. And economists are virtually certain that real prices (adjusted to exclude inflation) of nearly all standardized products and services will continue to decrease exponentially in the long run. Of course, it’s not quite as simple as that. Two notable exceptions are oil and gold. But even in these exceptional cases, the real price hasn’t gone up but remained constant in the long term, at least until now.

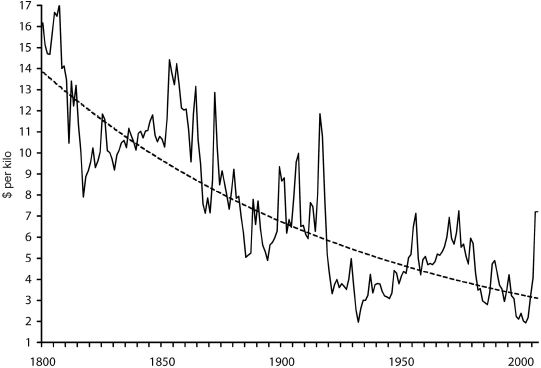

In the short term and medium term, however, there are huge fluctuations, which can inflict extensive losses or gains on both producers and consumers. As we saw earlier, the real price of copper quadrupled between 1932 and 1974, fell by 73% between 1974 and 2002 . . . and went back to the 1974 level in 2006. But even in the extreme case of copper, the general trend is consistent, as figure 7 shows.

Again, salaries have been going up exponentially since 1800 (see figure 8), although there are considerable variations in the shorter term. It’s the same story as prices but in reverse.

Figure 7 Real copper prices (constant 2007 dollars)

Figure 8 Real wages/salaries in constant 2006 pounds, UK

Put them together and these two long-term trends are extremely good news for those of us who earn money and buy stuff with it. Our buying power increases at a double exponential rate as prices decrease and income increases! All those lovely standardized goods and services are ours for the taking. The result is material abundance, at least in economically advanced countries.

On the other hand, when our weekend shopping frenzy is over and we’re back at work, it’s a different story. Falling prices and rising pay add up to a double whammy for managers. One way or another, their ultimate objective is to increase the profitability of the companies they work for. And the easiest way to do so in the short term is to increase prices, while also decreasing their payroll expenditure. Trouble is, that’s the opposite of what’s going on in the marketplace, as we just saw. In the long term, the winners are the companies who can capture market share by lowering prices and still attract the best talent by increasing salaries.

Try telling that to a copper industry executive back in the 1960s. He would have laughed in your face. As we said in chapter 6, most business people just don’t get history. And you can’t blame them really. The board, shareholders, and financial analysts are usually too busy looking at the next quarter’s results to care about the past or even the medium-term future. And there’s certainly no incentive to pry into the long-term threat posed by some scientists in a glass-manufacturing company.

But how on earth do you go about squeezing prices downwards, while also generating extra cash to hire and retain competent employees – at the same time as keeping your shareholders smiling? The only solution is to increase productivity, usually through automation, organizational improvements, or technological innovation. Think about using a bulldozer to dig the foundations of your house, rather than a spade. Or, to use a more recent innovation, booking flights over the internet, compared to queuing on the high street and generating pointless paperwork. This may not sound very glamorous or clever, like inventing a new search technology, reinventing the MP3 player as an iPhone and iPod, or creating an entirely new material to transmit digital information. But it can be equally effective in the survival stakes. The streamlining strategy can stop competitors from outside your industry from overtaking you and forcing you out of business. Creative destruction it isn’t, but it can save you from being creatively destroyed for many profitable years to come.

Before we talk about our second, bolder strategy, let’s digress pleasantly for a moment into the world of childhood. As a seven-year-old, what did you want to be when you grew up? It’s unlikely that “executive” was very high up your list of ambitions. You don’t see many kids dressing up in suits and ties to enact boardroom dramas. Instead, these days at least, they’re outside playing soccer in David Beckham shirts or indoors perfecting their karaoke. Unlike the children of yesteryear, who wanted to be nurses or train drivers, the youth of today generally aspire to stardom. Europe, Asia – and now the US – is full of little boys who don’t simply wear the Beckham shirt, but genuinely believe they will live the Beckham life one day.

So what do we as parents do? Should we encourage our kids to moderate their ambitions from movie star to train driver, nurse, or executive? Should we tell them that, for every Beckham, Ronaldinho, and Zidane, there are several thousand professional soccer players who never make it to the premier league, let alone the national side? Should we point out the daunting mass of competition from all the other kids who are similarly convinced that stardom beckons?

The answer is that we can try, but it probably won’t do any good. No parental illusion of control here then, but plenty of a different kind of illusion from the kids: the illusion of success. As we mentioned at the beginning of this book, this is largely caused by the media. Television, newspapers, and glossy magazines rarely tell us about “failed” actors, singers, dancers, and football players, let alone the “average” ones. They’re not news – just like the thousands of airplanes that safely reach their destination every day.

The same goes for entrepreneurs who dream of turning their start-ups into Apple or Google. Do they realize that fewer than one in ten new products succeed? Do they know that most of the startups that survive achieve only average performance? Have they ever heard a venture capitalist joke about the “living dead,” those entrepreneurs who limp on for years by borrowing from family and friends, never paying salaries or turning a profit?

Again, it’s tempting to blame the media. The business papers are always writing about Bill Gates and Michael Dell, not Joe Average or David Failure. But it’s also our fault. We don’t want to read about ordinary entrepreneurs making average profits or the start-ups that finished up. The only failures we show any interest in are the spectacular ones like LTCM, Enron, WorldCom, and Lehman Brothers, which involve the mighty falling. We get the media we deserve. So when we automatically equate “start-up” with success, we ultimately have ourselves to blame. Mediocrity and failure are a bit like the dog that didn’t bark – they don’t draw any attention to themselves until we, like Sherlock Holmes, are willing to seek beyond the obvious.

The illusion of success, however, isn’t all bad. Like the illusion of control it can lead many people to make the wrong decisions, but for a select few it pays off. Take Tiger Woods. His father introduced him to golf at the precocious age of eighteen months and encouraged him to practice intensively throughout his childhood. If Earl Woods had worried about his son’s minuscule chances of becoming a champion, golf would be a much duller sport today.

More importantly, the world needs crazy entrepreneurs who believe they’re invincible. Without them we’d have no new products or services – no cars, no telephones, no internet. If everyone feared failure, there’d be no such thing as progress. This process is analogous to evolution, where certain mutations form the basis of a new species, while other animals become extinct. Some entrepreneurial innovations prove successful and evolve into engines of progress, while others lead to the dead-end of bankruptcy. It’s bad luck for the individuals that fail, but it’s highly beneficial to society as a whole. In fact, it’s precisely what’s needed for creative destruction to take place. It may be unpleasant, but it is the truth: modern society benefits from the failure of the many as much as it thrives on the success of the few.

It should be clear from our digression that the key to harnessing creative destruction – as an individual company or sole entrepreneurial operator – lies in balancing our attitudes to success or failure. It’s significant that the most entrepreneurial economies in the world are those – like the USA and unlike much of Europe – where failure is not only tolerated but it is accepted. Those countries that lose their appetite for risk become incapable of innovating and changing the status quo. Successful innovation, therefore, requires a lot of trial and error and, paradoxically, cannot be achieved without failure!

At the same time, as an individual player, it is absolutely critical to understand your chances of failing and the risks involved. People who practice so-called “dangerous” sports set an interesting example. We generally believe that those who scale a cliff face, base-jump from a bridge, or sail solo around the world are seeking the thrill of adventure to the point that they’re prepared to risk their lives. By contrast, we see the vast majority, who opt for more conventional sporting hobbies, as playing safe. However, appearances are perhaps deceptive. Many people have accidents playing basketball, American football, soccer, rugby, squash, cycling, and even cheerleading (thanks to the pyramid formation and that irresistible temptation to throw people in the air). The reason is simple. In a dangerous sport, the danger is obvious, so evaluating the risk and taking measures to avoid injury are part of the game. Meanwhile, on the municipal sports ground or on in the school gym, people feel so safe that they fail to take the most basic precautions.

Any individual seeking success should take some inspiration from dangerous sports and realize that much of the pleasure is in the journey rather than the arrival. He or she should confront the possibility of failure and construct a personal safety net. Having a plan B or an exit strategy is crucial. It may not lead to the success originally desired, but could salvage the situation from total disaster. In the case of dangerous sports, total disaster spells death; in business it means financial ruin.

But it’s not just about meeting with triumph and disaster and treating those two imposters just the same. In any competitive context – business included – most performances are just average. This is a mathematical certainty. Only a select few can be tennis champions or principal ballerinas. Mid-table mediocrity is in most cases the most likely alternative to success or failure – and a possibility that has to be faced bravely too.

There are also lessons for success-seekers from the world of investment. As we saw in chapters 4 and 5, there are rarely big gains without big risks. The same is true in many other areas of life, including business. Above all, those aiming high should accept and embrace the role of luck in the final outcome – whilst of course doing all they can to improve their chances of success.

The best business-school brains all over the world devote a great deal of time and intellectual energy to the question of entrepreneurship, whether the traditional start-up model or so-called “corporate entrepreneurship” (which tries to foster innovation within the context of a large organization). We firmly believe that they’re right to do so – especially if they’re as willing to tackle the issue of failure as they are to tell success stories. The entrepreneurs that our society relies on for progress must first be able to see and then judge the risks and opportunities involved in their ventures. Come to that, business schools have a role to play in educating everyone, so that society can continue to nurture the desire for success, whilst becoming more accepting of failure.

On the other hand, it should be obvious by now that we don’t believe entrepreneurship experts from business schools – or anyone else – can provide simple recipes for success. As we’ve pointed out before, it would be a logical fallacy to believe in a failsafe method of succeeding in business. As soon as everyone reached average performance, someone would find a way of taking their company to the next level.

On a brighter note, entrepreneurship experts have developed some guidelines for managers (and governments) who seek to cultivate the right attitudes to success, mediocrity, failure, luck, and skill, in such a way as to generate creative destruction. Rather than giving a set of rules, we prefer to express these guidelines in the form of a series of tensions. There are no easy ways out. It’s up to each individual to decide where to place themselves between the opposing forces – knowing that one end of the spectrum represents eventual destruction from someone else’s creativity, while the other unacceptably risks everything on driving your own creative destruction.

Everyone knows that companies must be effective and efficient in order to keep costs down and compete with other firms. It’s also generally accepted that effectiveness and efficiency are typically achieved by implementing systems of control that minimize wastefulness without deviating from budgets. The problem is that tight operational controls can also stamp out innovation. They place people under constant stress and leave them little or no free time to think creatively. This is another instance of the paradox of control. You gain more options by giving up some control.

Companies like Google, and even more established players like 3M, try to keep the entrepreneurial fires burning by letting employees use, say, ten per cent of their time to pursue projects that interest them. At the same time, they make sure that people use the remaining ninety per cent as efficiently and effectively as possible on core corporate activities. When the internet bubble burst at the beginning of this century, some Silicon Valley firms survived precisely because they had adopted this strategy. Their employees had used their “free” time to develop alternative products and services that worked for the company’s benefit.

Even so, this small percentage of slack involves a real extra cost that most conventional big businesses are reluctant to shoulder. Creating an environment for innovation to thrive is – and will continue to be – one of the biggest corporate challenges. At the very least it involves recognizing that creativity is incompatible with tight schedules and that truly creative people can’t operate under tight controls. The trick is to find the right balance between efficiency on the one hand and nurturing innovation on the other.

It’s only natural that managers don’t like risk. They want to keep their jobs and move up the greasy pole. Collectively too, companies tend to be conservative animals that shy away from risk. But it’s the same old story as in chapters 4 and 5. It’s almost impossible to achieve above-average returns without taking some above-average risks. As we saw earlier, there’s strong evidence that simply managing for survival doesn’t guarantee strong, long-term performance for shareholders. Far from it. Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan whose work we referred to in the previous chapter (along with many other experts) have produced research that conclusively proves the need to take a few risks along the way.5

Ironically, not taking risks is perhaps the biggest risk any organization can take. Look at the stagnation of the former communist states in the years leading up to the fall of the Berlin Wall. The challenge is to allocate enough resources to experimentation and risk-taking without staking everything on the success of a crazy new idea. Of course, some risks can lead to serious problems, even bankruptcy. But not to take any risk at all guarantees you’ll be overwhelmed by the forces of creative destruction.

It’s an age-old story, we know, but the companies that last are generally prepared to spend generously on R&D, brand-building, and developing their employees – the engines of creative destruction. In short, they see the value in sacrificing immediate profits on the altar of long-term competitive advantage. The contradiction is that the stock market doesn’t seem to look beyond the next few quarters’ earnings. Yet those companies concerned purely with milking their cash cows inevitably have a short shelf-life that doesn’t bode well for shareholders. Again, it’s a question of balancing the tensions in a way that works for the company.

Once upon a time, companies’ competitive advantages depended on their fixed assets: their factories, their machinery, their land. Building a new plant required a major capital outlay, which fortunately also discouraged new competitors to enter the market. This is still true up to a point in certain sectors, but today, there is overcapacity in practically all industries. Competitive advantages come instead from new products and services, clever marketing, and innovative strategies. And these activities all depend on people, not fixed assets.

Compare and contrast Google and GM. The former had only 16,000 employees (in 2007) and no tangible assets to speak of. The latter had nearly 300,000 employees and acres of factory space. But, surprise, surprise, the stock market, at the end of 2007, considered Google to be eleven times more valuable than GM. Investors aren’t fazed by Google’s size or lack of property. On the contrary, they consider these advantages that make the company not only nimble but also able to keep its talented workforce happy and creative. You may not be able to touch or feel these assets, but they’re the ones that keep Google ahead of its competitors in the world of search engines and information technologies.

But unlike machines and production lines, talented people are notoriously hard to manage. Their demands are high, so not all companies can afford them in the first place, let alone keep them productive as time goes by. Perhaps this is the most difficult of all the challenges we’ve mentioned.

It’s illuminating to examine the approach taken by venture capitalists. Contrary to popular belief, venture capitalists don’t rely on accurate predictions of the future for their success. Like us, they know that the future’s not ours to see. Of course, there’s a certain amount they can do to check that a business is well run and founded on solid premises. But they can’t tell which brand-new products and services will catch the consumer’s imagination, no matter how much research they do. Instead, a good venture capital fund adopts a “que será será” attitude and invests in a number of projects. It’s taken for granted that some will fail, but that some of the successful ones will make it big and compensate for any losses. If that sounds implausible, consider how many companies innovated with MP3 and music distribution technologies before Apple sewed up the market with the iPod and iTunes.

Venture capitalists also have a clear exit strategy. They usually withdraw after three to six years, sending out a clear message that the chosen companies have two stages in their life cycle. The first involves creating and bringing to market a successful product or service. The second is about managing that product or service as effectively and efficiently as possible. Venture capitalists separate the two. They focus on the former with their know-how and connections, while leaving the latter to someone else. Perhaps, in so doing, they provide established companies with a model for resolving the tensions we ran through above.

As we’ve seen, businesses find themselves in a bind. On the one hand, they want to be rational and maximize their short-term profits for the benefit of their shareholders. On the other, they know they have to innovate to compete with entrepreneurs who are working in their garages for eighteen hours a day, seven days a week with no pay but limitless motivation. The only solution seems to be to reorganize along the lines suggested by the venture capital industry, creating separate entities – some dedicated to milking existing products or services for short-term gain, and others given creative license – whilst also benefiting from the finance, expertise, and connections of the parent company.

Again this is no simple, guru-style solution. The exact distribution of resources across business units is hard to get right. Even if we could give you a magic ratio, there are by definition no formulae for innovation and success, which have a sneaky tendency to defy all rules. Yet several companies are adopting the venture capital approach. Business Week recently reported that Google for one is busy investing in high-tech start-ups around the world. That way, they’re not only first in line for any marketable technologies developed, but also avoid paying out vast sums of money to venture capitalists who got there before them.6 These and other innovative types of investments will have to continue if companies are going to exploit the benefits and avoid the dangers of creative destruction.

Society itself must play a part too, with governments encouraging both corporate entrepreneurs and the traditional garage or bedroom-based species with, for example, tax breaks that shift attitudes to success and failure. Heaven knows, it’s hard enough to create an internal company culture of creativity, let alone the external conditions for incubating innovation. But the fact is that no successful innovation is possible without trial and error – and therefore failure.7 Failure is thus a necessary part of our economic system, whether we like it or not. So we might as well change our attitudes to it.

The forces of creative destruction now operate on a global scale. As managers have come to accept innovation as a critical corporate challenge, so they have sought global solutions. Many are building R&D facilities in India and other low-cost, highly educated countries – often with financial incentives from national governments. Other solutions are to outsource innovation to universities or dedicated firms, again not necessarily around the corner from headquarters. Nowadays there are even innovation brokers who match inventors with potential funding, sometimes from large corporations which have grasped the importance of creative destruction. All in all, the rate of innovation is increasing – and with it the pace of creative destruction.

Thanks to the internet, the pace of creative destruction is accelerating yet further. Not only does global connectedness provide innovative new products and services and business models, it also provides tools for innovators. Information and even products or services are disseminated instantly at a global level, eradicating inefficiencies and wiping out any old-fashioned competitive advantages based on geography or local knowledge. Today it takes only a few minutes to compare prices from suppliers across the globe and to choose the one that offers the best value for money. The internet has transformed both markets and competition, cutting out the much-derided middle-men . . . thus eliminating the necessity of a loop in the virtuous cycle of innovation.

Finally, the copper-style ascendancy of the old-school Western and Japanese multinationals is coming to an end. The fall of communism and rise of technology have enabled companies from countries in Eastern Europe, as well as from China, India, Malaysia, and Taiwan, among others, to go global. And until they start having to pay Western or Japanese wages, innovation is the only option for the rest of the world. It makes no sense that a Barbie doll or a pair of running shoes that costs less than a couple of dollars to produce in Vietnam sells for more than thirty times this amount in Europe, Japan, or the USA. Prices will be forced down in these places, while salaries in the new economies will be driven upwards – all thanks to creative destruction.

The story we have been telling in this chapter is another illustration of the paradox of control. Imagine for the moment that you are the benevolent dictator of your country and you want to make sure that the economy works both well and fairly. So – with the best of intentions – you introduce planning and control systems to make “sure” that people get what they want when they want it. The problem – and this has been illustrated again and again by the failure of centrally planned economies – is that this won’t work well. There is no way that your planners will be able to forecast consumer demands nor even anticipate technological innovations or external events that can change both demands and costs. No, you are better off giving up control and letting market forces take over. The paradox of control works here too. The more you are willing to give up control and let the market forces take over the more you increase your chances of future success. This is precisely why “free markets” outperform all other economic systems and produce the greatest wealth – even though they are not without their own imperfections.

In the last two chapters we’ve seen that management theories are as transitory as companies themselves. There are no simple formulae for success, let alone lasting success. On the other hand, there are two enduring trends in the business world: exponentially decreasing prices and exponentially increasing pay. These pose long-term challenges that run contrary to most executives’ short-term objectives. The only solution is to accept – and ideally exploit – the forces of creative destruction that drive the free-market system, constantly obliterating the old and replacing it with the new.

But of course, as with all advice given by well-meaning books, it’s much easier said than done. Doing business is like stepping into Heraclitus’s river. It’s a highly complex activity, buffeted by many temporary currents. Indeed, the uncertainties that we’ve seen throughout the first half of this book can all sweep companies’ fortunes away: terrorist attacks, tsunamis, epidemics, public health scares, rogue traders, stock market crashes, not to mention unforeseen new forces, such as the increased focus on the environment and employee rights. In the second half of the book, we’ll resist the temptation to give you advice about managing your health, investments, or business, and focus instead on explanations. We’ll dip into the statistics, science, and psychology of uncertainty and leave you to draw some conclusions of your own.