Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.

Winston Churchill

History is bunk.

Henry Ford

In May 2007 a troubled relationship finally came to an end. The final split came as no surprise to those who had been watching. But just nine years earlier it had seemed a match made in heaven. Everyone had said they were perfect for each other: a distinguished European pedigree linked to a name that stood for the American dream. No one would have predicted nearly a decade of miscommunication, mistrust, and misery – and finally the painful break-up itself. It’s another all too true story of misplaced certainty, high emotion, and utter inability to predict.

The relationship in question was the now infamous merger between US car giant Chrysler and the prestigious German motor manufacturer Daimler-Benz. The man at its center was Jürgen Erich Schrempp, CEO of Daimler-Benz AG, who had instigated and sealed the deal – to the point that some commentators called it a “take-over.” But this was a saga on an epic scale with thousands of characters. Not just executives and workers of both companies, but armies of advisers, consultants, and bankers . . . and finally the private equity firm Cerberus, which eventually “rescued” Chrysler.

It all began in 1998. The price tag of $36 billion for Chrysler seemed a bargain. The merger would enable Daimler-Benz to conquer the US luxury car market, while Chrysler would learn from the Mercedes engineering legend and gain a foothold in Europe. After all, if Volkswagen had managed to turn Skoda, infamous for its poor quality, into a respectable car company, the profits to be made from transforming Chrysler were vast. The optimistic assessment was that the market capitalization of the combined company would increase by more than $100 billion after five years, while the absolute worst-case scenario was still over $40 billion.

The stock markets and business press were on the side of the optimists. The day the merger was announced, the Chrysler share price soared by 17.6%, while that of Daimler-Benz went up by 6.4%. Analysts were waxing lyrical about “synergies” and “economies of scale.”

The first signs of trouble came barely six months later in May 1999, when the press started seeing signs of culture clash. Then in 2000 Chrysler suffered unexpectedly high losses – with worse projected for 2001. Schrempp fired the American President, James P. Holden, and replaced him with his own protégé from Germany, Dieter Zetsche. The new guy sacked 26,000 employees and replaced further American executives with Germans. Morale dwindled and years of restructuring loomed. By 2006, Chrysler’s annual loss was $1.2 billion with an additional restructuring charge of $1 billion.

Meanwhile, things weren’t going brilliantly back in Germany. Mercedes was slipping down the industry quality rankings. There was an embarrassing product recall, and losses in the business involving the small Smart cars eventually totaled $3.6 billion.

Schrempp finally stepped down or, more accurately, was forced to do so in 2005, leaving Zetsche in overall charge. Shares rallied at this news, with an 8.7% increase. But the damage was done. In May 2007 Daimler unloaded 80% of its shares on Cerberus, actually paying them $650 million for the privilege of taking over an acquisition that had originally cost $36 billion! Worse still, in November 2007 it was announced that as many as 12,100 more employees would lose their jobs in 2008, in addition to the 13,000 redundancies already planned over a period of three years. So much for the deal that had once been hailed as the “merger of the century.”

How could so many experts get it so wrong on such a multinational scale? All these famously clever people – top executives and their bankers, paid seven- and eight-figure salaries – made catastrophically bad decisions that tarnished two great brands. Had Schrempp and his team ever heard of uncertainty? Did they know that at best only two out of three mergers achieve their financial objectives? They weren’t alone either. Hundreds of journalists, investors, and business school professors, among other experts, had also failed to predict the disastrous turn of events. So how are ordinary mortals supposed to manage in their everyday lives and work?

There’s certainly no shortage of people who claim they can help. Gurus are everywhere. Whether you’re interested in management, alternative therapy, education, marriage, or parenting, there’s always someone with a new theory (accompanied by a glossily marketed new book) which promises to solve all your problems. And – like the investors of the previous chapter – as managers, patients, educators, spouses, or parents, you’re driven by desire, fear, and hope to listen (or at least buy the book). This makes you a captive audience for those who preach simplistic solutions. But which particular gurus should you believe?

As business school professors, the authors’ own experience lies with management gurus – which is why they’re discussed at length in this and the next chapter. But the same arguments can be applied in other fields. We also believe that the management gurus are the most influential of all. Many of them work for leading universities, top media companies, or strategy consultants and so command great respect. Even if you’re not the kind of person to buy business books or magazines, the latest management theories almost certainly have a profound effect on your life. No longer confined to business, their teachings pervade the entire working world and shape the products and services on which we all depend.

By now, you’ll have noticed a pragmatic – if not downright critical – thread to our arguments. Don’t expect us to be any different about management theories. But bear with us, and again we promise a positive message in the end. Like everything else in life, business success is greatly influenced by luck, and this is important to remember. To do otherwise is to give in to the illusion of control – the same illusion of control that duped Jürgen Erich Schrempp into believing that nothing could go wrong with his merger of the century.

Let’s start with one of the most radical management theories of them all. In 1993, the book Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution hit the airport bookstores. Its authors, Michael Hammer and James Champy, claimed that the time had come to throw out all the principles that had guided business over more than two centuries in favor of a new model. “The alternative,” they warn on page one, “is for corporate America to close its doors and go out of business” – not exactly a modest statement. The new theory went by the name “reengineering” and the book-jacket blurb staked some pretty ambitious claims for it:

Reengineering does not seek to make business better through incremental improvements – 10 percent faster here or 20 percent less expensive there. The aim of reengineering is a quantum leap in performance – the 100 percent or even tenfold improvement that can follow from entirely new work processes and structures.1

Reengineering went on to be a worldwide hit. A 2005 survey of top management tools from the leading international consultancy, Bain & Company, put reengineering, which was used by 61% of companies questioned, in the top ten.

Yet today, reengineering is practically forgotten. There are no major conferences or popular seminars on the subject. The last book we know was published in 2003 and the business journalists have moved on to newer theories. The once popular www.reengineering.com no longer operates, nor do the niche consultancies that sprang up to spread the word. Reengineering has lost its appeal and become part of management history.

It’s not the only business theory to rise and fall in this way either. How many seasoned managers remember Management by Objectives, T-Groups, Theory Z, the Managerial Grid, the Systems Approach, Experience Curves, PIMS, the BCG Growth Matrix, Competitive Strategies, S-Curves, Product Life Cycles, Total Quality Management (TQM), and One-Minute Management? In each case, initial euphoria swiftly gave way to over-familiarity, disappointment, and finally obscurity.

Perhaps each of these theories deserves to be forgotten. But the phenomenon as a whole, with its repeated pattern of growth and decay, should be remembered by any manager seeking a quick fix or miracle cure. In the academic community at least, it’s reassuringly possible to discern a few voices who speak out against the gurus. One of these belongs to Professors Eric Abrahamson and Gregory Fairchild from Columbia Business School in New York, who in 1999 penned the following warning.

Our results suggest that management fashions intended to be both rational and progressive may in fact be irrational and, thus, retrogressive from the point of view of the thousands of organizations and millions of managers and employees who use these fashionable techniques both nationally and globally. Such widespread perpetual change, if it is technically inefficient, has the potential to generate pervasive waste, burnout, and cynicism about the potential for all forms of advancement in management.2

Fortunately for the world of business, it doesn’t necessarily come to this. Many new theories are just variations on old ones repackaged with fancy names and brightly-covered books. You could argue, for example, that the theory of reengineering began with Henry Ford’s production line. But elevate a technical process to a metaphor, add a dose of fear and some marketing know-how, and hey presto, you’ve got a best-seller on your hands! The downside is felt only by the employees whose jobs were reengineered out of existence, or the investors who ultimately paid the fat consulting fees charged by the reengineering experts.

Today, reengineering has been reincarnated as “business process management” (BPM to its friends). It’s better this time around, as the new theory takes the useful idea of “process” and puts it to practical use, while discarding the more faddish and dysfunctional elements. Meanwhile, the term “reengineering” lives on non-metaphorically – and very valuably – in the worlds of manufacturing and software. This happy ending defines the key challenge for managers: how to find and exploit the real benefits in management theories, while avoiding the negative consequences of becoming a management-fashion victim.

One obvious and common-sense course of action is to identify successful companies and find out what makes them great. That’s exactly what Tom Peters and Robert H. Waterman Jr. set out to do in the 1982 book, In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Known Companies.3 It was an instant phenomenon and went on to sell multiple millions of copies, thanks to its simple and apparently impeccable logic. The authors singled out thirty-two outstanding US companies and listed eight common factors for managers in other organizations to replicate.

How have the thirty-two exemplary companies fared since then? In the past quarter-century, five ended in bankruptcy or chapter 11 proceedings while six merged or were bought by other firms. This means that more than one in three of the excellent 1982 firms did not exist at the end of 2007. But what about the remaining twenty-one? Well, if we look at their share prices over the last ten years ending on December 31, 2007, we find that twelve did better than the S&P 500 during this period, one did the same (that is, within ±5% of the S&P 500) and eight did worse. Thus, even if we exclude the six firms that merged or were bought, thirteen companies did worse than the S&P 500 and twelve did better – the pattern of pure chance. Finally, only two of the initial thirty-two companies made it into Fortune magazine’s 2007 survey of the top ten most admired US companies (more about this below). Excellence may well have been found in 1982, but it didn’t definitely endure until 2008.

As if to pre-empt this disappointment, in 1994 another book appeared. Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies was another instant bestseller.4 Its authors, Jim Collins and Jerry Porras, used a similar methodology, only this time the book was the result of a six-year research project and the goal was to find not simply what made companies successful but also to identify what made them stand the test of time. As it happens, half of Built to Last’s eighteen “visionary” companies were also included in In Search of Excellence, although the common factors of their success were quite different in the two books.

The eighteen companies of Built to Last are all still in business. On the other hand, several have been through bad patches, while Citigroup, Sony, Ford, and Motorola have faced serious financial problems (which resulted in their share prices falling by more than 84% between 1995 and 2009). In terms of stock market returns in the seven years ending on December 31, 2007, nine of the eighteen companies did better than the S&P 500, eight did worse and one did the same (within ±5%). OK, they have lasted. But overall their financial performance is average. Was the six years of research really any more effective than randomly selecting eighteen companies that happened to be going through a good patch at the time of writing?

At this point, it all seems a bit confusing. Why can’t those management gurus get it right? And given their atrocious track record, why do managers keep buying into their latest theories?

The second question probably has a more obvious answer than the first. It goes back to the greed, fear, and hope that we’ve seen before. It’s all too easy to be seduced by a theory that promises effortless success. There are probably further psychological explanations too. Management gurus are usually poor historians while many managers often have big egos. They like to think their situation is unique and that there’s nothing to learn from their predecessors’ vast bank of experiences and mistakes. Sometimes this attitude pays off. If you’re an innovator like Henry Ford, you’ve earned the right to dismiss history as bunk. But for the rest of us this can lead to grave errors.

Now to the gurus, themselves. To be fair, we’re sure they have the best intentions and they don’t in any way set out to exploit the psychological weaknesses of managers. But best intentions are no substitute for rigorous methodology. To see exactly what we mean, let’s consider how to draw a valid scientific conclusion from a sample of data.

Imagine, by way of example, that you work in the facilities department of a university, which is currently refurbishing its student rooms and buying a new set of beds. You’re sent out to estimate the average height of male students, but you’re only given the time and funding to measure 50 of the 6,000 men currently enrolled. The obvious reaction is to measure the first fifty you see. But only a couple of students into the process, you notice that everyone waiting in the queue to be measured just got off the coach from the inter-university basketball tournament. And so it dawns on you that you need to find a way of selecting the fifty male students by chance. Only once you’ve done this – and measured their heights – can you make a scientifically meaningful statement about the average height of the 6,000 students. It’s this chance selection that ensures your sample of fifty is likely to be representative of the wider population.

If we apply this thinking to In Search of Excellence and Built to Last, the once impeccable logic starts to look a bit shaky. The (rather small) samples of thirty-two and eighteen companies respectively were selected anything but randomly. No doubt, the “best practices” the authors identify really are common to all the companies concerned. But how do we know they aren’t shared with thousands of average performers, failures, and bankrupt companies? In short, these particular management theorists over-sampled success and under-sampled mediocrity and failure (this over-sampling of successful firms becomes obvious by the fact that six of the top ten US companies identified in Fortune’s 1983 survey5 were included In Search of Excellence and five of the top ten in Fortune’s 1993 survey were included in Built to Last).

Tom Peters, Jim Collins, and their co-authors aren’t alone. Most management gurus make the same mistake. It’s nonetheless strange to find so many intelligent people falling into such an old trap. Way back in the 1930s, the Austrian-born philosopher of science, Karl Popper6 leveled exactly the same charge at Sigmund Freud, whose psychoanalytical theories had gained widespread acceptance. Popper pointed out that real scientists start with conjectures, which they then try to refute – as well as seeking evidence to support them. Only by failing to disprove their hypotheses, can they prove they were right all along. (This is why the medical researchers whose work we glimpsed in chapters 2 and 3 always have control groups in their experiments.) Meanwhile, “pseudoscientists,” as Popper called them, only look for events that prove their ideas correct. Theories like this are little more than untested assertions. That’s not to say that the assertions won’t eventually turn out to be right – but we can only reach this conclusion once someone has tested them.

The other problem is the way in which the theorists make inferences from their own sample of successes to the entire population. For instance, imagine that gurus identified an incontestably brilliant management practice among eighteen companies in the US during the 1990s. Will the brilliance of this practice hold true for all other firms in the US? Will it also work in India or China in 2010? Or in the US in 2015? Not necessarily. We all know that many important factors change across time and place, history, and geography. To make this kind of extrapolation is equivalent to assuming that our results for the average height of fifty male students will also apply to the entire male population not only now but also in fifteen years’ time.

Clearly, outstanding companies owe their performance to certain factors. And equally clearly, it’s of considerable interest to identify and exploit these factors. But it’s far-fetched to assume that they’ll be unremittingly beneficial in different times, cultures, and environments. Time and again, we’ve seen extrapolations like this fail in the world of business. Many of the Japanese star companies of the 1980s, which the management gurus once urged us to emulate, themselves faced serious problems less than a decade later. Sony, the Japanese super star (one of the visionary companies included in Built to Last) stayed successful to the end of the twentieth century, but at the beginning of the twenty-first – after its share price had fallen 84% – the board of directors took the last resort of appointing a foreigner to head a much-needed turnaround. Past success is no guarantee for the future . . . or new markets, or new technologies. This much is an empirical fact. After all, even Wal-Mart, that paragon of all-American retail virtue, withdrew from Germany under a cloud of failure. And what could all those once-rock-solid typewriter companies have done to halt the digital word processor’s march of progress?

No company has managed to remain “excellent” or “visionary” for long periods. Instead, the changing business environment requires a model of continuous adaptation – and sometimes revolution – which can’t be achieved using recipes from the past. So was Henry Ford right all along? Well, only up to a point. Over-simplistic historical – or geographical – reasoning really is bunk. Perhaps management gurus and their followers spend too much time looking purely at business. With a little more training in the subtleties of historical, geographical, scientific, and statistical methodology, they might design some more robust research projects with the following characteristics:

• Sampling failure as well as success. A group of randomly chosen firms, similar to those singled out for their great performances (but different in that they lack the “best practices” identified), would have to perform relatively badly over a long period of time. To be fair, Built to Last tries to do this up to a point.

• Large, representative samples over long periods of time. The number of firms investigated would need to be large enough – and the time span of the investigation would need to be long enough – to prove that the companies’ achievements are due to the specific factors identified, rather than luck.

• A solid attempt to refute the theory. In particular, researchers would need to look carefully for firms that exemplified the selected “best practices” identified, but which nonetheless fail.

• An ongoing reality check. Researchers would need to verify that the factors for success discovered hold true in new environmental conditions. They’d have to be prepared to refine or abandon their theories accordingly.

Alas, these conditions are almost impossible to respect, but it would be nice to think that management researchers aspire to them. On the other hand, perhaps it’s just as well they don’t. If someone ever did figure out the exact recipe for business success, everyone else would apply it and all businesses would become disappointingly average!

As the two quotes with which we started this chapter suggest, we believe it’s important to learn what we can from the past, but without extrapolating wildly into the future. And if we really want to understand what makes companies successful across time, it’s a useful exercise to track the performance of companies at different points in their histories. Consistent success might indicate practices that stand the test of time. Inconsistency would suggest the contrary.

We’re therefore lucky that, since 1983, Fortune magazine has been publishing an annual league table of America’s most admired firms. The ranking is based on a survey of managers and analysts (the data are collected and analyzed by the top consulting firm Hay Group). Set criteria are used to give each company scores, which are then aggregated to get the overall result. So how many stars of the 1980s are on Fortune’s current list? Very few, it turns out, and in some industries there are none at all. Once great names, such as AT&T, General Motors, Ford, Sears Roebuck, Eastman Kodak, and Xerox, have all suffered serious reversals in their corporate Fortunes over time.

The difference between explaining the past and predicting the future is fundamental. All credit to Fortune magazine that they don’t make guru-like claims to offer the recipe for future success. Instead, without doing any fancy research, they ask respondents to identify high performance in firms they know a great deal about. And when we measure the subjective criterion of “admiration” against objective factors, such as stock market performance, we find a great deal of correlation. The ten most admired companies in 2005 produced average returns of 23.1% in 2003 to 2004 (compared to the S&P 500 average of 10.88%). Go back a bit further and the story is the same. Between 1999 and 2004, the top ten produced average returns of 6.1%, while the S&P 500 average was a dismal -2.3%.

No clairvoyance here, then. Just good solid knowledge of the past and present. On the other hand, in the near future at least, you’d probably expect many of the most admired companies to continue performing well. Even if they don’t have the best practices, they’ve got some momentum from accrued competitive advantages. And indeed, for the 2005 top ten, this was the case. Nine of them also appeared in Fortune’s ten most admired companies for 2006 – and even the one that got away, Wal-Mart, only slipped from fourth to twelfth. The same happened in 2007 and 2008. From the top ten of 2006, eight still remained in 2008 (Dell and Microsoft dropped out) and Microsoft was in sixteenth place.

But there was no way of knowing that Dell, the most admired company of 2005 and eighth in 2006, would slide out of the 2007 and 2008 surveys altogether (it’s not even in the newly expanded “top twenty”). In 2006 it had serious operational and strategic difficulties. By the middle of the year its share price dropped to under $20 (from over $42 at the end of 2004). As if the customer service problems and the massive notebook battery recall weren’t enough, there was also a Federal investigation into its finances and accounting practices. At the time of writing (mid 2008) we have no foresight as to whether Dell will recover or regain the admiration of Fortune’s survey respondents. But at the time of reading, you probably have the benefit of some hindsight as to whether the stock market was correct in reducing Dell’s value by over 50% in less than two years. Our point is simply that your hindsight and our lack of foresight are very different beasts.

Today, as we write, the participants in Fortune’s survey have just discovered Google and its dominance of the internet. It was included for the first time in 2007, as America’s eighth most admired company, and it rose to fourth in the 2008 survey. This reminds us of Dell’s meteoric rise between 1995 and 2000, when its share price went from less than $1 to over $50. Just remember Google’s words on its own search page: “I’m feeling lucky”. Are their strategists doing everything right? Or was the company in the right place at the right time? Only time – not gurus – will tell.

Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne’s Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant provides another prescription for success – “innovative strategies.”7 Although one can raise questions about Blue Ocean Strategy, along with other business blockbusters such as In Search of Excellence and Built to Last, it’s also important to recognize that they provide an important service. Namely, they identify a number of “excellent” or “visionary” companies based on valuable accounts of past successful performance that is due to some form of innovative strategy. It would be pointless to argue against this historical logic.

However, even in the case of innovation, we warn against assuming a one-to-one relation between prescriptions based on past success and future triumphs. It’s the deterministic relation between the “lessons from” and the “how to” in the subtitles of these books with which we take issue. And that’s because it’s yet another case of the illusion of control. It’s going one step too far to believe that these factors – deployed by different organizations in different times, places, and situations – will lead to outstanding performance again and again, with complete certainty each time.

But there’s also an inverse problem. That is, companies often fail to spot the innovations on their own doorsteps. Consider the case of Xerox. In the 1970s it dominated the market in office copying. Cleverly spotting the rise of computers and the possible threat to the entire photocopying industry, Xerox executives set up a research program at their California office in Palo Alto to investigate the future of the “paperless office.” The brilliant researchers were highly innovative and essentially created the PC, complete with easy-to-use interfaces, mouse controls, connections between different computers, and even a form of email. Sadly for Xerox, the senior managers on the East Coast lacked the imagination to see what their own West Coast unit had achieved. Fortunately for the rest of the world, someone else – a twenty-something techie from outside the organization – glimpsed the potential of Xerox’s innovations. His name was Steve Jobs.

Jobs claims that, if Xerox had realized what they’d created, they’d have dominated the computer industry through to the 1990s. As it turns out, Jobs initially got his own strategy wrong with Apple, which went through some bad times of its own. It’s not clear that Xerox would have done any better. What is clear, however, is that high levels of creativity and innovation are – by definition – limited to a few talented individuals or companies. If everyone had the talent of Van Gogh, Picasso, or Monet, then the level of creativity would rise to new levels that only a few even more exceptional artists could achieve. The trick for the art investor is to spot today’s great painters who will be remembered tomorrow . . . or – if you’re a senior manager – to predict which innovative strategies will work in the future, and be lucky enough to be alone in doing so.

Contrary to the image projected by best-selling books, the business environment is extremely complex. It’s influenced by many chance events and driven by new technologies that defy prediction. What can the Encyclopedia Britannica do to compete with the free internet site Wikipedia? How should IBM and DEC have responded to mass demand for PCs? What could Compaq have done to compete with Dell’s new business model of selling directly to the customer, allowing it to offer lower prices for computers of the same or better quality? These were novel challenges with no precedents. Perhaps history can offer inspiration in such circumstances, but it certainly provides no magic keys.

Sometimes, the only hope is to break with the past completely. That’s why a change of CEO sometimes works. IBM, once considered the best-run company in the USA, had a narrow escape from bankruptcy during the period from 1991 to 1993 when it lost close to $12 billion. It returned to profitability after hiring an outsider who changed precisely those practices that had led to its former glory. As Blue Ocean Strategy documents so well, the problem is that competitors are forever catching up, copying not only successful products but proven practices. “Visionary” companies have to stay on their toes, forever seeking new vision and new innovative strategies.

If there’s one lesson from history, it’s this: history never repeats itself in exactly the same way. If there is another lesson, it is that successful innovation cannot be predicted.

Time and time again, we see the outstanding firms of the past become the underachievers of the present. Rubbermaid, for example, was in Fortune’s list of America’s most admired companies for eleven consecutive years between 1986 and 1996, even making it to number one in 1994 and 1995. That didn’t prevent Newell, a lesser-known company that also made plastic household goods, from buying it just a few years later. Similarly, General Motors used to be a paragon of management and market leadership. But by the turn of the twenty-first century, it was flirting with bankruptcy, and then lost its position as the world’s biggest car manufacturer to Toyota, which was practically unknown three decades ago.

Now, by our own admission, a few examples from the past don’t prove anything (least of all about the future). So let’s look in a little more detail at the ebbs and flows of the Fortune rankings of America’s most admired companies over the period 1983 to 2008. During this time, the magazine’s knowledgeable respondents considered more than a thousand companies. Yet, in twenty-six years of compiling top tens, they included a total of only forty-nine organizations. In other words, over 95% of eligible companies never made it into the list. An elite seventeen, however, have been in the top ten more than five times.

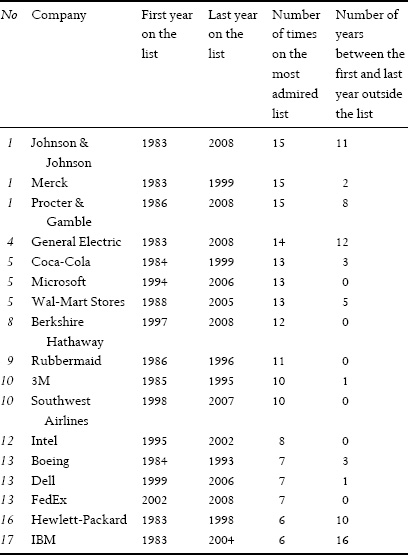

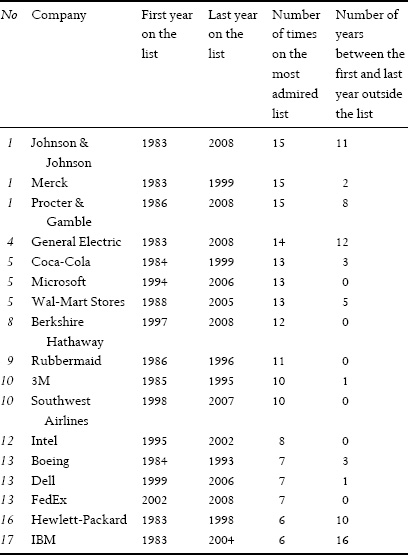

As table 10 shows, the most dominant companies of all – over this period – are Johnson and Johnson (J&J), Merck, and Proctor & Gamble (P&G). These three giants have appeared in the top ten an impressive fifteen times in the twenty-six years between 1983 and 2008. It is interesting that these three companies were also included in both Built to Last and In Search of Excellence.

Table 10 Fortune ’s most admired companies, 1983–2008

J&J and P&G have remained in the most admired list for several years through to 2008 but not Merck, which was dropped in 1999. Merck’s profits have fallen considerably since the late 1990s and, by 2005, its stock price had dropped by 73% (although it then recovered a little). It all began when Merck canceled the launches of several drugs that were supposed to be block-busters. There were also safety scares about certain products already on the market, as well as some patent infringement lawsuits and investigations into the possible withholding of evidence about the efficacy and safety of drugs. As the search for those responsible intensified, management problems became ever more severe. The once revered Merck lost its shine and became just another drugs company. Its rapid decline proves, once again, that past performance is simply not sufficient to predict future success.

Table 10 also shows that five firms in the sweet seventeen (Rubbermaid, Berkshire Hathaway, Southwest Airlines, Intel, and FedEx) are included every single year between their first and last appearances. Others (GE, Wal-Mart, and Coca-Cola) exhibit a similar pattern, but lapse for a few years before reappearing consistently once again. The remaining companies also show a tendency to cluster around consecutive years, although there are a few exceptions. The message seems to be that, once the admiration wanes, it’s hard to regain.

Curiously, table 10 shows a distinct shift between the new century and the old. Merck, Coca-Cola, Rubbermaid, and Hewlett-Packard appeared consistently before lapsing in 2000 and failing to return. Conversely, Berkshire Hathaway, Dell, GE, Microsoft, Southwest, Wal-Mart, Johnson & Johnson, and Procter & Gamble all appear for the first time, or reappear after an absence of several years, around 2000. Could it be that the most admired companies at the end of the last century simply made a natural regression toward the average? Perhaps an era of mediocrity has even dawned for the mighty Microsoft. After all, it slipped off the bottom of the list in 2007 after thirteen consecutive years in the top ten. Former McKinsey consultants Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan8 have made a special study of once-star companies and suggest that it’s rare to sustain stellar performance beyond a decade: “As soon as any company had been praised in the popular management literature as excellent or somehow super-durable, it began to deteriorate.” If this is true, then Microsoft is already living on borrowed time.

More than that, is it possible that Microsoft’s success was just due to being in the right place at the right time? The right place is the IT business. And the right time was the mid-1990s to mid-2000s – heyday of all things involving computers. Given the march of IT progress, it also makes perfect sense for Dell and Microsoft – leaders in their industry as were Hewlett-Packard and IBM before them – to appear when they did. In the case of Berkshire Hathaway, GE, Southwest, or Wal-Mart it could be a different kind of luck: drifting into one of those blue-ocean innovations or happening on a bunch of talented managers.

Out of curiosity, we compared our table of “the most admired of the most admired” with the names in Built to Last and In Search of Excellence. Remember that both books involved long, systematic research, whereas the magazine’s ranking is based on a survey of experts, whose subjective scores are averaged to get the top ten. Despite these very different methodologies, it turns out that eight companies (3M, Boeing, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Procter & Gamble, and Wal-Mart) are common to all three sources. In addition, the top three (J&J, Merck, and P&G) are included in both books. Is this coincidence or simply due to the over-sampling of success that we warned about earlier?

There is a particularly strong overlap between Built to Last and Fortune’s most admired of all. Nine companies appear in both lists and most of the other Built to Last companies have appeared in Fortune’s top ten at some point. In fact only four of the eighteen firms haven’t – and one of those, Sony, which is Japanese, isn’t eligible anyway. In Search of Excellence has less in common with our Fortune list, which you might expect, since it predates the magazine’s ranking and the research it draws on goes back even further. Nonetheless, nine companies out of the twenty-three included in In Search of Excellence (and that were still in business) also appear in our Fortune list.

If anything, the massed ranks of the Fortune respondents are rather better than the painstaking researchers at picking companies that last. Only one of their top seventeen, Rubbermaid, has fallen into truly serious difficulties, while – as we saw earlier – three of the eighteen from Built to Last and at least eleven of the thirty-two from In Search of Excellence are in serious trouble or out of business altogether. One reason for this is probably that the Fortune survey isn’t hung up on finding a simplistic recipe for success. The respondents use multiple criteria and their own totally subjective hunches to select companies. In 2008, the executives, directors, and securities analysts surveyed used a total of eight categories (quality of management, quality of products and services, innovation, long-term investment value, financial soundness, people management, social responsibility, and use of corporate assets) to rank companies. This means that single issues, such as stock market performance, don’t skew the results. For example, Microsoft, Wal-Mart, GE, and Dell have all done worse than the S&P 500 but still managed to retain their admired status. Yahoo and eBay, on the other hand, don’t appear in the top ten, despite their superior stock market performance and record for innovation.

The other reason that a popular business magazine seems to get better results than the academic researchers is simply that there are so many more opinions involved. Erroneous assessments cancel each other out. In other words, the averaging process extracts “pattern” from a “noisy” background. Gurus, in contrast, tend to operate alone, in pairs, or very small groups. Their more individualistic predictions – amplified by the need to identify success factors – are then totally exposed to the uncertainties of the future. In chapter 9, we’ll return to this problem of separating pattern from noise when we consider the power of averaging. We’ll discuss why and when we can rely on the “wisdom of the crowd” to assess uncertain quantities such as sales and reputations. In the meantime, let’s just say there’s more wisdom than madness in the way Fortune canvases the opinion of a large number of independent respondents.

Companies are like living creatures. They come into the world and, once they survive their teething troubles, they mature and eventually cease to exist. Sometimes, if they’re not killed off by bankruptcy, they even reproduce through the medium of merger or acquisition. Arie De Geus, a retired Shell executive,9 has conducted research that shows the life expectancy of new firms in Europe or Japan to be less than thirteen years – down from twenty in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Even if they grow up to be large multinationals they’re likely to last only forty to fifty years in total. And Foster and Kaplan estimate that by 2020 the average S&P 500 firm will stay in the index for just ten years – down from sixty-five in the 1920s, when the list first appeared.

There are, as usual, exceptions. Like giant tortoises, there are some companies that have made it to over 150 years of age. But they tend to move like giant tortoises too. All the evidence points to the conclusion that the financial performance of long-lasting firms is below the market average. As Foster and Kaplan say: “the corporate equivalent of the El Dorado, the golden company that continuously performs better than the markets, has never existed. It is a myth.”10 Managing for survival doesn’t guarantee strong performance for the entire corporate lifespan – in fact, just the opposite.

The ephemeral nature of success and the natural tendency toward mediocrity and eventual failure is the rule for all systems devised by mankind, whether countries, industries, economic structures, or superpowers. Since the beginning of human history, empires have come, seen, conquered . . . and disintegrated. Persia, Greece, and Rome took it in turn to dominate the ancient world. Since then, there’s been a succession of empires, culminating in the presence of a single superpower at the end of the twentieth century. But change is already underway. Many people say that the twenty-first century belongs to China.

Since the industrial revolution, entire economic sectors have risen to preeminence only to lose their appeal as others gained in significance and profits. The canals and railways dominated the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, finally giving way to oil and steel, followed by car manufacturing in the twentieth century. In the last 100 years, electrical appliances, telecoms, banking, pharmaceuticals, consumer electronics, and financial services have all risen to prominence. Now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, all of these have been eclipsed by the new stars of the information industry (despite a small blip at the end of the millennium). Right now, search engines and social networking sites are all the rage, but who knows what tomorrow will bring?

Identifying the secrets of successful companies and replicating them elsewhere is the holy grail of management gurus, consultants, and their customers. Or maybe it’s more like searching for the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, though. We can never get there.

That doesn’t stop people like Jim Collins repeatedly trying, however. He’s one of the authors of Built to Last, which was written partly with a view to correcting the methodological problems of In Search of Excellence. Yet Built to Last was not without a few problems of its own. One of Collins’s colleagues at the top management consultancy, McKinsey, allegedly told him, “You know, Jim, we love Built to Last around here. You and your co-author did a very fine job on the research and writing. Unfortunately it’s useless.”

So serial-guru Collins embarked on another mammoth research project. Five years later, in 2001, it came to fruition with his next best seller. Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap . . . and Others Don’t.11 Collins isn’t exactly modest in his claims. He says he’s identified the “timeless ‘physics’ of good to great” and can show us “how you take a good organization and turn it into one that produces sustained great results.” And you don’t even have to be good for it to work. He adds that “almost any organization can substantially improve its stature and performance, perhaps even become great, if it conscientiously applies the framework of ideas we’ve uncovered.”

Whatever happened to the eleven companies identified by Collins as having made the leap from good to great? It turns out that none of them has appeared in the Fortune top ten of most admired US companies since 2001, when the book came out. One of them, Gillette, no longer exists. It remains a successful brand-name, but the company itself has been bought by Procter & Gamble. Of the remaining ten, the stocks of seven of them performed worse than the S&P 500 during the last five years (ending in December 2007) while that of one did the same (within ±5%). That “physics” is beginning to look less “timeless” already. For all we know, to be fair to Collins, the companies could all have stopped applying his framework. But in their particular case, it may be time for a sequel, Great to Good. We hope, for their sakes, that the inevitable follow-up, Bad to Worse, doesn’t come too soon.

Meanwhile, McKinsey partner Bruce Roberson, in collaboration with two academics, kept pursuing the end of that rainbow. They started the Evergreen Project, a five-year study of more than 200 well-established management practices used by 160 companies over a ten-year period (1986 to 1996). It culminated in 2003 in another book, What Really Works: The 4+2 Formula for Sustained Business Success.12 The book concludes that the companies with the best long-term performance are extremely good in four fundamental practices and very good in two out of a further four practices. Here’s the “four” part of the equation – the must-haves:

• Devise and maintain a clearly stated, focused strategy

• Develop and maintain flawless operational execution

• Develop and maintain a performance-oriented culture

• Build and maintain a fast, flexible, flat structure.

And here are the four additional options, from which companies should choose two to master.

• Hold on to talent and find more talented employees

• Build a leadership philosophy of commitment to the business and its people

• Change your industry through innovation

• Grow through mergers and alliances.

There’s not much room for argument with any of this. It sounds like good common sense. But what the authors don’t say is how to devise and maintain a clearly stated, focused strategy, how to develop and maintain flawless operational execution, how to develop and maintain a performance-oriented culture, how to come up with the innovations that would change your industry, and so on . . . you get the picture. And that’s the hard bit.

Another more recent management book along the same lines of research is Alfred Marcus’s Big Winners and Big Losers: The 4 Secrets of Long-Term Business Success and Failure, published in 2006.13 The promised recipe for success is: start from an advantageous industry position (“a sweet spot”) and make sure your management is adaptive, disciplined, and focused. Conversely, the recipe for failure is: start from a disadvantageous industry position (“a sour spot”) and make sure your management is rigid, inept, and diffused. Again, so far, so indisputable. But how do you do all this in your particular situation?

At least the recipe for becoming a business guru is by now quite obvious. Carry out a long study of successful companies (and ideally some failures too). Criticize some previous such studies. Come up with some “secrets” common to all of them. Fill in the gaps by describing the exploits of a bunch of companies that prove your case particularly strongly. Easy, if a little time-consuming.

In both What Really Works and Big Winners and Big Losers, however, the chosen few companies don’t stand the test of time. Campbell Soup is classified as really working by the former, but as a big loser by the latter. Yet there’s only three years between their publication dates. What’s more, the stock market performances of the supposedly exemplary companies in both books are already falling short of expectations. No matter, next year, there’ll probably be another guru with another crop of successful companies, which will – sooner or later – fail.

OK, we’ve been a little mean to the gurus. There is clearly much food for thought and plenty of inspiration in their accounts of business success or failure. The theorists also provide an important historical record besides identifying the broad issues to which managers should pay attention. But it’s equally clear that we can’t count on research studies based on detailed dissection of past performance as a guide for the future. To do so is – once again – to fall victim to the illusion of control. Yet, paradoxically, the limited life span of all humanity’s structures – from small companies to empires, from management theories to (presumably) the entire capitalist system, is itself a case of history repeating itself on a grander scale. The implications of this duality – that is, what we can and cannot learn from history – are the theme of the next chapter. As both the Fortune survey and the histories of the companies identified in the three best selling books prove, there is no such a thing as lasting success. Instead, the excellent, visionary, and good-to-great companies identified by the gurus regress toward mediocrity. This is either a very depressing or a rather comforting thought, depending on which way you look at it.