Thirty years later

It would be nice to conclude that all who have read (and written) this book will live happily ever after – by putting the knowledge from chapters 1 to 7 together with the insights from chapters 8 to 12 and the glimpses of happiness in chapter 13. To maximize the chances of this happening, here’s a brief recap . . .

First and foremost, accept the empirical evidence. This shows that – in many circumstances – it’s best to dispel the illusion of control and dance instead with chance. Paradoxically, in so doing, we gain more control over many aspects of our lives.

One such area is health and longevity. Medicine, it turns out, is an inexact science. It cannot predict what will make individuals live longer or more healthily. Neither can doctors. So the best course of action is to stay away from them, until we feel unwell (or become pregnant). Consulting doctors, taking precautionary tests, or having regular check-ups does not increase life expectancy. Instead, these activities can lead to further expensive and unpleasant tests and treatment, possibly even unnecessary surgery. On a cheerier note, we can take heart from the power of the human mind to heal the body, as demonstrated by the placebo effect and self-rated health. Best of all, by taking a statistical, evidence-based approach to our own healthcare, rather than placing blind faith in physicians, we stand a better chance of getting the right treatment.

Now for this book’s second area of interest: wealth. Economics and finance are even more inexact sciences than medicine. Experts from these fields are good at explaining past performance but no better at predicting which securities will bring the best returns than a monkey with a dartboard. Rather than seeking expert advice, then, we’re better off investing our savings by selecting stocks at random or by buying into an index fund which tracks a reputable selection of securities. Not only does this reduce long-term risk, it also saves paying fees to fund managers with seven-figure salaries and Ferraris. It’s also important to realize that short- and medium-term stock market uncertainty can be huge. In the twentieth century, the record fall of the Dow Jones Industrial Average index in a single day was 22.6% and in two weeks 38.4% (the corresponding records for increases were 15.3% and 31.5% respectively). The models of mainstream financial theory, most of which rely on “normal” distributions, simply cannot capture such huge rises and falls. All the more reason to trust luck or monkeys rather than self-appointed experts.

Third, what about success in management? Well here, we’re no longer in the realms of science at all – exact or inexact. It’s not clear that management gurus can explain the past let alone predict the future. Averaging the opinions of knowledgeable individuals or using simple statistical models is often more accurate. But frankly, business forecasts usually serve to diminish executive anxieties about future uncertainty – and reinforce the illusion of control. In addition, we must all accept that creative destruction is an integral part of the free-market system, destroying the old and creating the new. Although some individuals and even whole industries may get hurt in this tsunami of progress, society as a whole is a winner. Creative destruction, like evolution, can only be explained after the event rather than predicted in advance, adding an extra level of uncertainty to managerial decision making and strategic planning. The only solution is for managers to embrace the unpredictability of the business environment and to operate a little more like venture capitalists – “investing”, at least for the long term, in a few well-chosen ideas. The trick is to be in with a good chance of at least one brilliant (and lucky) idea more than making up for the inevitable failures.

The principles behind the stories in the first part of the book are explained in the second:

1. The future is never exactly like the past.

2. “Complex” statistical models fit past data well but don’t necessarily predict the future accurately.

3. “Simple” models don’t necessarily fit past data well but predict the future better than complex models.

4. Both statistical models and people have been unable to capture the full extent of future uncertainty and been surprised by large forecasting errors and events they did not consider.

5. Expert judgment is typically inferior to simple statistical models, at least for repetitive decisions.

6. Averaging (whether of models or judgment) usually improves forecasting accuracy.

In addition, there are two different types of uncertainty (called subway and coconut for the purposes of this book), which add a whole new dimension to the task of forecasting.

When it comes to making decisions, the importance of taking full account of uncertainty is paramount. One method is to use the three As: first accept, second assess, and third augment the uncertainty of the situation. Unfortunately, too many people fail to augment and end up having to deal with surprising outcomes. Another strategy is to support intuitive decisions (or “blinking”) by analytic thinking wherever possible – remember the chess grandmasters and their years of painstaking practice. As for the remarkable properties of simple modeling (or “sminking”), decision makers tend to under-exploit them, while relying excessively on the opinions of experts who are immune to the consequences of their expertise.

Finally, to return to happiness, chance seems to play a significant role here too. And there’s yet another bunch of experts to fend off – the “positive psychologists” who claim they have prescriptions to make us happier and thus live longer. Once again, empirical evidence proves that the self-styled experts may be wrong. Golf seems to work just as well as their recipes for happiness. What’s more, the Japanese, who regularly rank among the most miserable people on earth, are one of the longest-lived nations of all. The same goes for the Greeks, who are well known for their inclination to tragedy yet enjoy one of the world’s highest life expectancies. The paradox of control implies that it’s by coming to terms with the way we are and the culture we’re from, however negative or melancholy, that we create our best chance of happiness. And that’s as happy as this ending gets.

As the final words of this book are typed in August 2009, it is some thirty years since the chance encounter in a business school of the two professors who cannot sing.

During these three decades, their lives have taken many unpredictable twists and turns. There have been new jobs and new countries, new wives, and new children. Fortunately for these patient and forgiving wives and children there has been very little singing. But there has been a great deal of talking – which is something that professors do almost as well as thinking. The talking now tends to take place via the medium of technologies that could not have been imagined thirty years ago: huge networks of fiber optics, mobile phones, video conferencing, and most importantly Skype with its free conference calls.

However, during these thirty years not everything has been a surprise. The professors’ conclusions about our inability to predict have been confirmed by a great number of empirical research findings and their classification of two types of uncertainty is increasingly widely recognized.

As for the third professor, he may not have been around for quite such a long time, but he has been making up for it by spending longer and longer in the shower, where – when not singing – he likes to think. Together with his tone-deaf friends, he has tried to come up with some practical advice to deal with the big challenges facing forecasters, decision makers, and ordinary people alike. Hence this book that is so very nearly finished.

The big question that originally brought the three professors together was what to do about the limited accuracy of forecasting. How can we make decisions, plan, and formulate strategies, given the low levels of predictability and high levels of uncertainty in our lives? But our three wise men would be the first to recognize that luck played as important a part as the big question in bringing them together. How else could three such different people – one Greek, one Scottish, and one Indian – have met in France, after Ph.D.s from top US universities, then have written this book together while living in three cities so far apart: Athens, Barcelona, and Singapore?

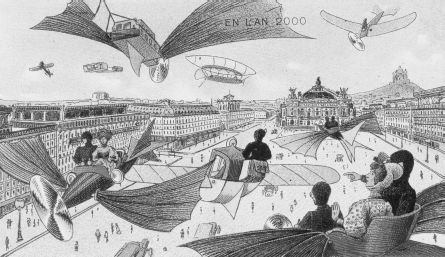

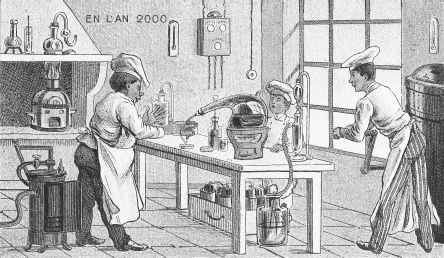

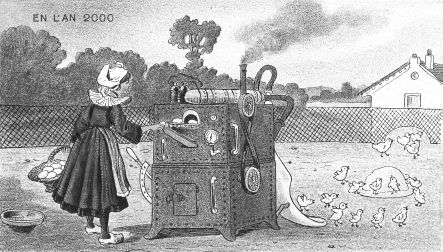

Will the book, this tale of three cities, be a success? Will readers enjoy it? Will it sell well? Who knows? Least of all the three professors, who are sticking to their story right up to the paradoxical last line. Indeed, if you have any lingering doubts about the story of the dance with chance, take a look at figures 19a–19d. They were drawn at the beginning of the twentieth century by Parisian futurologists who were trying to predict what life would look like at the beginning of the next century. Draw your own conclusions, but it’s safe to predict that life 100 years from now will be as unpredictable as it always has been.

Figure 19a A busy street in central Paris

Figure 19b A restaurant kitchen

Figure 19c Relaxing at home

Figure 19d Technology on the farm