Money doesn’t buy happiness.

Traditional saying

Those who say that money can’t buy happiness don’t know where to shop.

Anonymous

At the beginning of this book, we rashly promised you happiness. Well, a final chapter on the subject at any rate. If you remember the genie of chapter 1, his most popular request was for happiness – along with health and longevity, wealth, and professional success. In the first part of this book, we focused on the role of luck in these three areas of life. And in the second part, we gave you the underlying practical and theoretical understanding to grow your personal Fortune in all fields. So, assuming you’ve followed our advice already, are you happy? You should have amassed a big personal Fortune by now, but is that the same thing as greater happiness? You may even have been blessed with unrelenting luck. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re happier either. Happiness is as slippery a concept as it is a highly subjective feeling. In short, it seems impossible to predict our future happiness, or to control it, as pure chance plays a huge role. Unlike love, however, (another wish of those in possession of genies), there is a surprising amount of information on the subject. It is possible to draw some firm conclusions about the pursuit of happiness. And that’s what we’ll endeavor to do for you in this chapter.

Of course, even by imparting all our knowledge on the topic, we can’t promise you happiness itself. But if you press on with this chapter, we can at least guarantee a heady mix of celebrities, fast cars, sex, and nuns . . .

One of the authors knows a girl named Maria. Now, if anyone merits the description of “happy,” it’s Maria. And she’s got plenty to be glad about. She’s just turned eleven and lives with her loving parents and brother in Sarrià, a well-to-do neighborhood of Barcelona. But that’s where her luck seems to end. Maria is disabled and will always need to wear leg braces. Doctors aren’t sure why her legs don’t work properly – perhaps it’s something to do with lack of oxygen at birth or an obscure genetic defect. It doesn’t seem important, anyway, as Maria is always smiling. She never asks for help going up or down the stairs and never falls, even though she always looks as if she’s about to. The little Spanish girl seems to get so much pleasure out of life that her happiness is infectious – for her family and those around her.

Maria goes to the local school, but has few friends. It’s not just that her classmates don’t want to play with her. They tease her too, constantly reminding her of her disability. But somehow, Maria behaves as if she hasn’t heard their comments and enjoys being surrounded by able-bodied kids, who never hear her complaining about her disability or her bad luck. She’s also a good student: top of the class in mathematics and computers. And she never gives up trying to make friends – even with Pilar.

Pilar lives across the road from Maria, in an even bigger house. The two girls are in the same class. Pretty, smart, healthy, loved, and pampered, Pilar ought to be the happiest kid on the block. But she isn’t. For a start, she complains about everything – from the color of her shoes to getting up early to go to school. Once there, she gets on OK with her work and the other children. Not that she’s top of the class in any subject, but then she rarely does her homework or any extra studying. Back at home, she’s most commonly to be found fighting with Anna, her younger sister. The rest of the time Pilar is generally sulking or declaring that she hates her family, her home, and her life. Even as a baby, she rarely smiled and cried when no one was entertaining her. Fortunately, Anna is of a cheerier disposition, but the atmosphere in the house is undoubtedly poisoned by Pilar’s presence. Their mother cannot understand how her two daughters can be so different, as she believes that she raised them in the exact same way.

It’s not obvious why Maria seems to be happier than Pilar, or why Anna is a sunnier child than her sister (their mother reluctantly puts it down to fate). Similarly, it’s not clear why some countries or cultures are happier than others. But research has repeatedly shown that the differences themselves are big and indisputable. Compare and contrast Japan with Bhutan, which in 1999 became the last country in the world to introduce television.

Bhutan is a small Buddhist kingdom, sandwiched between China and India, with an area of about 47,000 square kilometers (that’s 18,000 square miles, which makes it a bit bigger than both Switzerland and Maryland). The population is about 672,000 according to the government’s own census, and 60% of the people make their living from subsistence-level farming. The World Bank estimates GNP per capita at only $1,400, giving its people a fairly low purchasing power by global standards. Yet Bhutan is a beautiful, unspoiled land with mountains, dense forests, and picturesque monasteries. And its people always score highly in international surveys on happiness.

Japan too is a Buddhist country in Asia. Living standards are high and, as we saw in chapter 2, life expectancy is the highest of all countries, with the exception of some tiny ones like Andorra. But according to surveys, the Japanese are a miserable lot. In 2006, Adrian White, a psychologist from the University of Leicester in the UK, produced a meta-analysis of major satisfaction studies, resulting in a world map of happiness.1 Bhutan comes out in eighth position, mingling with some of Europe’s richest countries, while Japan ranks only ninetieth – lower than Uzbekistan, where GNP per capita is about eighteen times smaller. Just as there seems to be no good reason why Maria is so much happier than Pilar, so there’s no obvious explanation as to why the Bhutanese are so much more content than those from the land of the rising sun.

Happiness is our friend the genie’s most popular request, but some nations and people seem to be naturally happier than others for no obvious reason at all. This is not the only puzzle involving happiness as we will see below.

Are we to assume from the examples so far that money can’t buy you happiness any more than it can buy you love? It’s a question that has intrigued philosophers, poets, and pop stars over the years. And recently, two psychologists, Ed Diener and Martin Seligman,2 set out to answer it once and for all. They carried out a survey of various groups of people, ranging from the tycoons and heiresses on Forbes magazine’s billionaires list to Calcutta’s pavement dwellers. The respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with the statement, “You are satisfied with your life,” using a scale from 1 (complete disagreement) to 7 (complete agreement), with 4 suggesting a neutral attitude.

How much do you agree with the statement? _____

(According to the survey, if your answer is above 5.8, you’re happier than a billionaire.)

Mind you, apart from among homeless people, the research found no huge differences in happiness between the different groups. The Inughuit natives of glacial northern Greenland and the Pennsylvania Amish expressed the same levels of satisfaction with their lives as the very richest Americans. The semi-nomadic Maasai of Africa may be fractionally less content than the billionaires, but they score higher than a random selection of Swedish people. Even the satisfaction rates of Indian slum dwellers are not much worse than an international sample of college students, a privileged group. Intriguingly, one of the biggest differences in satisfaction rates is between the Pennsylvania Amish (scoring the same as the billionaires) and the Illinois Amish (scoring a little better than the Calcutta slum dwellers). But the most striking result is that that none of Diener and Seligman’s groups – including the super-rich list – came close to the perfect 7. (You can compare your own answer with the results of Diener and Seligman shown in table 13.)

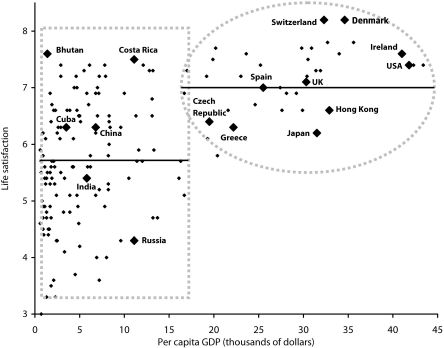

This and other studies point to the same conclusion: life satisfaction doesn’t increase once people reach a certain minimum level of income.3 Some researchers have even expressed this threshold in dollars: per capita GDP, in purchasing power parities of around $16,000.4 In one particular survey, inhabitants of different countries were asked the following question: “On a scale of 1 (dissatisfied) to 10 (satisfied), how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?”5 This time, the researchers plotted the country’s average satisfaction rating against its per capita GDP. This enabled them to distinguish two distinct groups – countries with per capita GDP of more than $16,000 and those with lower levels of income. The two groups are shown in the rectangular and oval shapes in figure 18.

Table 13 Average life satisfaction for various groups

Forbes magazine’s “Richest Americans” |

5.8 |

Pennsylvania Amish |

5.8 |

Inughuit (Inuit people from northern Greenland) |

5.8 |

African Maasai (semi-nomadic tribes from Kenya and Tanzania) |

5.7 |

Swedish sample |

5.6 |

International college-student sample (47 nations in 2000) |

4.9 |

Illinois Amish |

4.9 |

Calcutta slum dwellers |

4.6 |

Fresno, California, homeless |

2.9 |

Calcutta pavement dwellers (also homeless) |

2.9 |

This mapping of international happiness reveals one very strong message. Within each of the two groups of countries, there is no obvious relation between wealth and life satisfaction, but the average level of satisfaction is higher in richer countries. There are, however, some notable exceptions. Bhutan, which we already know about, is joined by Costa Rica in reporting higher satisfaction than the USA. Similarly, Indians are more satisfied than Russians, despite lower GDP per capita, and communist Cuba seems happier than capitalist Japan. The comparison between Hong Kong and China is particularly interesting. People in Hong Kong are on average much better off than those from mainland China, but their levels of satisfaction with life aren’t that different.

What happens to happiness in countries which experience rapid economic growth? To return to Japan once again, real income increased fivefold between 1958 and 1987. But self-reported satisfaction levels remained constant across this period.6 And the London School of Economics professor Richard Layard reports that the percentage of people in Britain and the USA describing themselves as “very happy,” “quite happy,” or “not happy at all” has remained the same for five decades, despite the fact that they were getting steadily richer all this time.7

Figure 18 Life satisfaction vs. per capita gross domestic product (GDP)

In some ways, this is hardly surprising, as researchers have documented the same phenomenon on an individual level, notably with lottery winners. As you might expect, winning the jackpot does make people happy. But not for long. After a year, or at most four or five, they revert to their previous levels of satisfaction. They just get used to being rich and stop being happier than before they won the lottery. So does it really make sense that many of us toil for long hours under constant stress to raise our income to a level far below that of a lottery win? Are we any happier as a result?

The Oxford economic historian Avner Offer goes one step further than asking such questions. He argues that increased wealth has actually undermined human well-being. According to his book The Challenge of Affluence, a rise in psychological distress, together with increased crime, drug dependency, and obesity, are all correlated with economic growth and added wealth.8 Will we be able to reverse this situation in the future and learn to be happier?9 In that case, is there anything that will bring us lasting happiness?

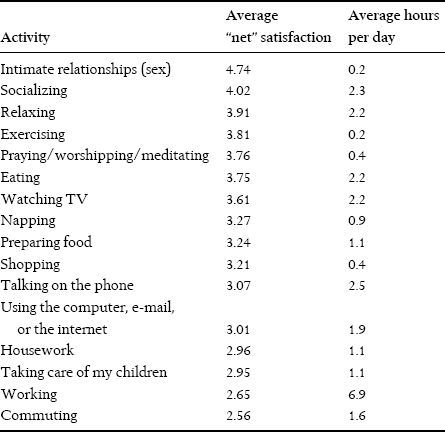

Daniel Kahneman (see chapter 11) recently took a new approach to understanding happiness, which he named the Daily Reconstruction Method.10 His project involved research participants filling out a detailed diary. They had to list everything they’d done during the day, then rate – on a seven-point scale, from 0 (= “not at all”) to 6 (= “very much”) – a number of feelings for each event (for example, pleased, happy, depressed, tired, concerned). The researchers then worked out a “net” satisfaction rating for each activity and took the average across the entire population surveyed. They also calculated the average number of hours spent on each of the activities per day.

Why not try a simplified version yourself? Kahneman’s list of activities is given in table 14, arranged in alphabetical order. We suggest that you just give each of them a score between 0 and 6, where 0 means “doesn’t give me any pleasure whatsoever” and 6 means “makes me very happy.” If you want to go one step further, you can also estimate the number of hours you spend on each activity on an average day.

Kahneman’s happiness guinea pigs consisted of a large sample of Texan women – 909 of them to be precise. They were a pretty representative bunch: 24% African American, 22% Hispanic, 49% white, and 5% other, with an average age of thirty-eight and a mean household income of about $55,000. As experts in statistics, we know you’re probably not a woman in Texas, but as keen observers of human nature, we reckon you probably want to compare their results with yours. So don’t look at table 15,11 unless you’re ready.

Table 14 List of daily activities

We don’t know how these figures compare with your own answers, but some of the data are intriguing. It’s not surprising that sex and socializing are the most satisfying activities or that working and commuting are the least appreciated. But it’s curious that taking care of children comes so low on the list – even lower than doing housework. Are Texan kids really that bad? Or is childcare a universal disappointment?

Table 15 Average “net” satisfaction and average hours of daily activities

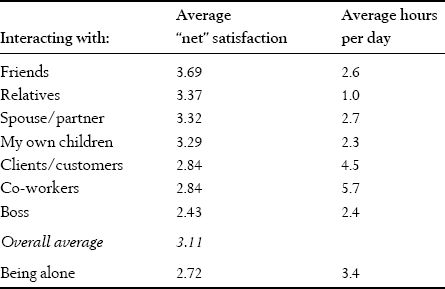

Data in the social sciences should never be taken at face value, however. Note that the 0.2 hours spent on sex is an average – no one is suggesting that twelve minutes is enough for a 4.74 satisfaction rate! Sex is always a problematic issue in surveys, anyway. It’s hard to get people to be really truthful about it: some people exaggerate, while others come over all coy. In this particular study only 11% of respondents listed sex as an activity, so sweeping generalizations aren’t possible. Instead, the researchers turned their particular attentions to the second activity on the list: socializing. They collected data on different types of social interaction and came up with the results shown in table 16 (using the same scale of satisfaction).12 Unsurprisingly, spending time with friends is most satisfying, while being with the boss is about as miserable as it gets. The respondents clearly don’t enjoy being alone either, but even that’s better than suffering the presence of the big bad boss.

Table 16 Satisfaction from different kinds of social interactions

After analyzing all the data, Kahneman and his colleagues concluded that people’s happiness with daily life is strongly influenced by personality characteristics, situational conditions, and mental health. If you’re prone to depression, it’s obvious that you’re not going to find routine activities very uplifting. More significantly, the researchers found that factors such as education or income had little impact on the Texan women’s satisfaction. However, the better they slept, the happier they became the next day. So even if you can’t buy happiness, perhaps you can at least sleep your way to satisfaction.

Sleep isn’t the only solution. The newish field of positive psychology aims to help people improve their satisfaction with life and develop a more optimistic outlook. Its basic thesis is that Freud was wrong to characterize the human condition by its different neuroses. Instead, they cite evidence that smiling people are not only healthier and live longer, but also work harder, are more productive, more socially engaged, and generally more successful in life. Miserable souls, they argue, are self-obsessed and pessimistic, which gives others a low opinion of them too. As a result, things get even worse for them . . . and they get even unhappier. The most important teaching of the positive psychologists, however, is that absolutely anyone – even the grumpiest people – can take specific actions to increase their happiness in the long term.

This is where the nuns we promised you come in. Now nuns provide great opportunities for psychologists – positive or not. That’s because they all follow routine lives with similar activities and comparable diets. What’s more, they don’t get married or have children. In short, nuns constitute a homogeneous population.

One of the positive psychologists’ favorite studies concerns 180 nuns in Milwaukee.13 Back in 1932, the then novices were asked to write short sketches of their lives. One wrote: “God started my life off well by bestowing upon me grace of inestimable value. The past year has been a very happy one.” She recently died, aged ninety-eight, after a lifetime of extraordinarily good health. By way of contrast, one of her sisters painted a neutral-to-sad picture of her own life, concluding, “With God’s grace, I intend to do my best for our Order.” She died of a stroke at the age of fifty-nine.

OK, so two nuns from Milwaukee don’t prove much. But experienced researchers studied all 180 of the sketches and ranked them according to their net satisfaction with life. Then they looked at how long the nuns lived. It turns out that nearly 90% of the “happiest” quartile made it to eighty-five or more and 54% of them were still alive at ninety-four! By then, there weren’t many of the “saddest” quartile left. Less than a third of them reached the age of eighty-five and only 11% survived to ninety-four. As well as the nuns, Martin Seligman of the University of Pennsylvania, one of the leading lights in positive psychology, cites another survey, this time of 839 patients at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. It was found that “optimists” from this sample lived 19% longer than “pessimists.”14 But that’s all you can conclude. Who’s to say that the main reason for being an optimist wasn’t better health in the first place?

There are many further studies linking life satisfaction with health, long life, and success in general from all over the world. In the UK, researchers took blood samples from 216 middle-aged civil servants and found that the happiest people had the lowest levels of cortisol (a hormone that can be harmful in excess) and plasma fibrinogen (a chemical linked with heart disease).15 And in Holland, a large-scale study of 3,149 elderly people concluded that happiness – or at least satisfaction with various aspects of life – was closely correlated with longevity.16 Curiously, too, some researchers have even seen fit to investigate the difference in life expectancy between those who won major awards and those who were simply nominated (although it may be going one logical step too far to assume that the former are happier than the latter). Nobel Prize winners between 1901 and 1950 lived on average two years longer than mere nominees. Winning an Oscar is even better! Out of 1,649 nominees studied, the ones with Academy Awards on their mantelpieces lived 3.6 years longer than the rest.17 Don’t say we didn’t warn you that social sciences data have to be handled with caution, as another study, never mentioned by positive psychologists, found that Oscar winning screenwriters lived 3.6 years shorter on average than those merely nominated for the prize.18

But by far the most controversial claim of the positive psychologists is that they know how to increase and sustain your happiness.19 Some of them recommend exercises such as keeping a daily diary for six weeks to “count your blessings” or “writing a letter of gratitude” once a week for two months. Other suggestions include: building optimism by visualizing the best possible future for yourself once a week for eight weeks; practicing altruism and routinely committing kindness for six to ten weeks; and spending fifteen minutes a day reflecting, writing, and talking about the happiest and unhappiest events in your life. Dr. Seligman’s own website – one of many internet projects devoted to boosting your spirits – isn’t exactly modest about its own achievements.20

Early results from the Reflective Happiness website of Dr. Seligman demonstrate that after taking the first Happiness Building Exercise, 94% of members had a decrease in depression (some greater than a 50% reduction) and 92% increased their happiness. These results are comparable to the beneficial effects of antidepressant medications and cognitive therapy.

Positive psychology is common sense – up to a point. Of course people can shift their mindsets temporarily to focus on the upsides of life. It also stands to reason that happy people are likely to attract more friends, have fewer divorces, exude more confidence, and exhibit less stress. But this is a bit of a chicken-and-egg situation. And as for happiness making you live longer, who are you going to believe? One hundred and eighty nuns from Milwaukee or the entire nation of Japan who score so low in “happiness” surveys but live the longest of practically all countries? (Actually, the correlation between satisfaction with life and life expectancy among countries with more than $16,000 per capita GDP is zero.)

Fortunately for those cynical souls who come over all queasy when counting blessings or visualizing beautiful futures, there’s a simple alternative to positive psychology. It’s called golf. A recent study found that 300,818 golfers from Sweden lived, on average, five years longer than non-golfers, regardless of sex, age, and social group.21 Assuming these calculations are correct, this is a huge increase in life expectancy. But before you rush out to buy a new set of clubs, take a common-sense check again. Does the increase in life expectancy come from regularly spending four or five hours in the fresh air, walking briskly for six to seven kilometers, and flexing a few other muscles along the way, while at the same time socializing with other like-minded golfers? If so, then there are many other ways to improve your health and life expectancy. Golf and positive psychology are just two of the options.

It’s no wonder that so many psychologists are skeptical about the claims of Dr. Seligman and his followers. They question whether someone’s basic personality can change, whether you can turn a Pilar (from the beginning of this chapter) into a Maria (from over the road). Julie Norem, a psychology professor from Wellesley College and author of The Positive Power of Negative Thinking, says, “If you’re a pessimist who really thinks through in detail what might go wrong, that’s a strategy that’s likely to work very well for you. In fact, you may be messed up if you try to substitute a positive attitude.”22 She’s concerned that the messages of positive psychology may reinforce the naive belief, so prevalent in the US, that individual initiative and a positive attitude can solve all problems.

In particular, the critics of positive psychology question the link between happiness and success. History is littered with tales of tortured geniuses after all. The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s research, which we mentioned in chapter 11, confirms that celebrity at least doesn’t go hand in hand with happiness.23 He found that none of the ninety-one famous people he interviewed had been popular during adolescence. Instead, their great strength was the ability to focus on the skill that eventually made their name. Success, it seems, typically requires a level of dedication that’s incompatible with a healthy social life. Perhaps, in old age, as they look back at their lives, successful people are happy. But the converse is certainly not true. In fact, most of us tend to stop trying, as soon as we’re happy with our performance, leaving little room for further success.

Csikszentmihalyi is himself something of a celebrity in psychological circles. He’s most well known for an earlier piece of research, which seemed to prove – unlike the survey of Texan woman we reported earlier – that people are happiest at work (or at least, under certain circumstances)!24 Rather than getting his subjects to fill in exhaustive diaries of their activities and states of mind, he sent them messages at random moments in the day using an electronic beeper. They had to report exactly what they were doing at that precise time . . . and how happy they felt. According to Csikszentmihalyi, his respondents were happiest when in a “state of flow.” By this he meant that they were absorbed in a precise activity that is intrinsically rewarding, difficult but not impossible, and has clear goals that allow for frequent feedback on progress. In states of flow, people have a sense that they’re in control, yet lose all track of time and feelings of self-consciousness. A good example – take it from us – might be writing a book when it’s going well. As it happens, most cases of this heightened state occur at work rather than at play.

Positive psychology is all very well, but perhaps the answer lies in the Far East. Meditation, as practiced by religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism for thousands of years, seems to combine Csikszentmihalyi’s state of flow with the relaxation prized by the Texan women. However, it requires considerable effort and the mastery of some pretty difficult techniques. Attaining deep spiritual fulfillment is much harder than visiting a “happiness” website and carrying out some positive-thinking exercises. Beware of gurus bearing easy recipes, as we said before. And to reprise another recurring theme of this book, predicting happiness – even our own – is also pretty difficult, or even pointless. Let’s explain . . .

So far we’ve ticked off sex, celebrities, and nuns. Now for the fast cars. Daydream for a moment that you’re making a choice between a sleek sports car (perhaps a Porsche convertible), and a nice, reliable, but rather dull, saloon (let’s say a Volvo). Implausibly, in our hypothetical world there are no major financial or practical obstacles to either option. But there is a fairy godmother who makes one stipulation. Before making your decision, you have to envisage how happy you’ll be as a Porsche-owner. Then you must do the same for the Volvo. In fact, even in the real world, where there are no fairy godmothers, this is a good strategy for many of life’s decisions.

So which car did you go for? For most of us, even with the happiness-predicting condition, the Porsche wins every time. It’s a nobrainer. But that’s the crux of the problem. We ought to be better at applying our rationality to the slippery concept of happiness.

Harvard psychology professor Daniel Gilbert has made extensive studies of people’s ability to predict their future states of happiness. His book, Stumbling on Happiness, makes entertaining but depressing reading.25 As a species, he claims, we are truly rubbish at predicting our satisfaction levels. And the main reason is our intrinsic adaptability. The new Porsche may indeed give us a first rush of pleasure, but we soon get used to it (like the lottery winners we mentioned earlier) . . . and move on to the next desire – a fabulous house or stunning spouse maybe. Of course, we make a similar prediction error about that, before getting our fix of joy and then coming down from the initial high. And so it goes on. And on and on. It’s almost as if we’re too adaptable for our own good. We rapidly get used to even the most luxurious material possessions or outstanding achievements that subsequently have little or no affect on our happiness.

Collectively, however, the constant renewal of discontent helps the human race to progress. It’s part of the creative-destructive process we saw in chapter 7. And our surfeit of adaptability also has its plus points for the individual. We all have an amazing ability to bounce back – after disasters, as well as triumphs. People who discover they’re HIV-positive are devastated to start with. But as the weeks go by, they learn to live with their condition and the emotional distress subsides. The same goes for those suddenly afflicted with severe disabilities.26 Human beings somehow adjust their sights. Some are just grateful to be alive, while others find new pleasures in the capacities they formerly took for granted: seeing, hearing, smelling, talking. Divorce, bereavement, bankruptcy, loss of a limb, you name it, the pain eventually fades and we rebuild our lives. Sadly for us, though, intense pleasure fades in exactly the same way. Euphoria, by definition, is short-lived – even more so for a non-golfer or a miserable nun.

In short, our adaptability extends to both the good and the bad events that chance brings our way, and we tend to overestimate the long-term impact of both the good and bad outcomes in our lives. What’s more, our inability to forecast our future happiness leads us to make bad decisions over and over again. But – as we’ve seen with health, investments, and management – it’s important to recognize our poor powers of prediction and to take this into account when we make our decisions. As the empirical research shows, we can’t expect our recently sought happiness to continue indefinitely. At the other extreme, the influence on our happiness of even highly negative outcomes fades with the proverbial healer that is time.

According to Gilbert, the main issue we have to confront is the limitations of our own imagination. We tend to exaggerate certain details and conveniently overlook others. For example, we have a vivid image of driving our Porsche with the roof down on a sunny day. We don’t glimpse the possibility of sudden rainstorms, high insurance premiums, expensive repairs, careless speeding fines, spoiled hair-dos, three six-foot passengers . . . or any of the other annoyances associated with owning a cool convertible.

Gilbert’s solution is to consult people who have been there, done that, and got the T-shirt. Rather than relying on our incomplete imaginations, he argues, we should consult people who have owned both Porsches and Volvos for a while. We should ask them to tell us what they like and dislike in the most precise detail. Experiments performed by Gilbert and his colleagues show that we can figure out our happiness more accurately if we consult just one, randomly selected person who’s already had the same experience. This is “future perfect” thinking of the kind we described in chapter 10 taken to its logical extreme. As well as imagining what a future experience was like in the past, we find someone for whom it’s already done and dusted. Decisions affecting our happiness can be, therefore, dealt with in a more rational manner than naive belief in its predictability. As for all the other areas of life we’ve considered in this book, we can safely conclude that predicting our future happiness is not possible.

By now, you’re probably wondering how much all this research into happiness is really worth. After all, there’s no convenient unit for measuring happiness. It’s all very well to ask people to rate their satisfaction on scales of 1 to 5 or 1 to 7, but the answers surely depend on their cultures, their ages, their moods, how well they slept the night before, and all manner of subjective and objective factors. Indeed, there’s a great deal of controversy in psychology about the measurement of happiness.

On the one hand, there are academics who point out that their so-called subjective measures are remarkably consistent. On the other hand, some psychologists have gone to amusing lengths to prove that happiness levels fluctuate according to the weather or what you had for lunch. Professor Norbert Schwarz of the University of Michigan, for instance, asked people to fill out a questionnaire on life satisfaction. The catch was that they had to photocopy the questionnaire before filling it out. The further twist was that some subjects found a dime on the photocopier (planted by the experimenters), while others didn’t. And yes, you guessed it, those who found the dime were upbeat about their lives as a whole as well as the economy.27

Another experiment used students as its subjects. One group was asked, first, “How happy are you with life in general?” and then, “How many dates did you have last month?”28 There was practically zero correlation between the answers to the two questions. However, the order of the questions was reversed for the second group of students. This time there was a clear link between the number of dates and the level of their happiness. Of course, the groups were large enough and representative enough for their real differences in happiness to be negligible. It just goes to show that a satisfying month of love can cast a rose-tinted glow over every other aspect of life.

Obviously, the same question asked in different contexts yields very different answers. Remember the Texan women, who rated “taking care of my children” as less fun than “housework”? Their attitude contradicts the findings of the academic literature and the popular press alike. People questioned by the University of Uppsala in Sweden ranked interacting with their children the most enjoyable activity of all, followed by going on trips and being with friends.29 And when TIME magazine asked its readers, “What one thing in life has brought you the greatest happiness?” 35% said it was their children, grandchildren, or both.30 We shouldn’t jump to the conclusion that the children of Sweden or TIME readers are little angels, but focus instead on the way the question is asked. Clearly, there’s a big difference between childcare as a day-to-day activity and as a life-time’s achievement. Raising kids is a time-consuming and exhausting task, especially when you’re a working mother. But look back on the experience (even when your children are still quite young) – and it takes on a whole new light.

The difference between the pain involved in completing a task and the pleasure of the outcome is not only significant but complex. It’s not a gap that can be measured with a single question about how happy you feel. Imagine you’re in a small sailing boat, crossing the Atlantic single-handed. It’s midnight and there’s a storm raging. You’re wet, cold, and physically exhausted. If ever there was a zero on the happy-ometer, this is it. In fact, you mutter to yourself between chattering teeth: “I will never do this ever again. If I survive, that is.” But a week later, as you sail into harbor in the sunshine, your view has changed. The sense of achievement and joy at seeing your family smiling and waving on the waterfront is overwhelming. And a month later you’re planning your next big trip, this time across the Pacific.

The same is true of writing a book. It’s time consuming, mentally draining, and makes your family complain. But once it’s published and your readers are enjoying it, somehow it all seems worthwhile. And if it makes it onto the bestseller lists then it all the negatives are forgotten. Even the grumpiest family members encourage the author to start writing the sequel.

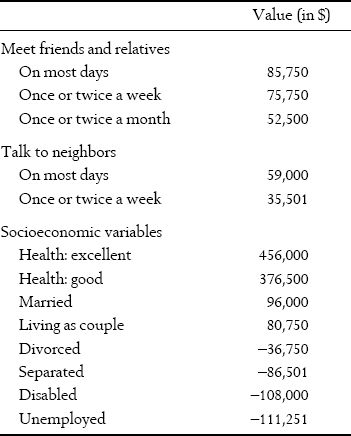

All in all then, it’s difficult to measure happiness. But that doesn’t mean to say we should give up. The American Declaration of Independence famously holds that “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” are among man’s unalienable rights. And the eighteenth-century Enlightenment thinker Jeremy Bentham went so far as to propose that the purpose of public policy was to maximize happiness. Today, “Happiness Economics” has entered the mainstream and some academics are even putting dollar values to different aspects of life. Using a long-term survey sample in the UK, one researcher matched up answers to life-satisfaction questions, various socio-economic data, and income figures to come up with the happiness price list shown as table 17.31

Unsurprisingly, good health has by far the highest value, while unemployment and disability have the highest costs. Good relationships whether with a spouse, partner, friends, neighbors, or relatives – are clearly very important to a happy life. And interestingly, divorce is about $50,000 less painful than separation. It seems that the initial separation is the hardest part of the process and that the final divorce brings an almost beneficial sense of closure.32

Table 17 Valuations of social network status and other life events

So we’re back to where we started our journey toward understanding happiness with the thorny issue of money. Money may not automatically bring happiness, but some people are using it to measure happiness. Such studies as these have their limitations, but provide an interesting if rough guide not only to what makes us happy but also to what’s possible in the study of happiness. Neuroscience is adding to the debate, as researchers start to measure activity in the parts of the brain where happiness resides. Nutritionists have joined the fray, suggesting that certain foods – among them turkey, tomatoes, and chocolate – can make you happy thanks to their high levels of serotonin. And of course, drugs that cheer people up have long been of great interest and profit to the pharmaceuticals industry, not to mention illicit dealers.

Meanwhile, countries as diverse as Bhutan, Australia, China, Thailand, and the UK are working on “happiness indices” to be used alongside GNP to evaluate socio-economic progress. In the UK, even the Bank of England – a national symbol of the importance of money – is looking for ways to measure happiness. But the greatest challenge is perhaps to use wealth in such a way that it generates happiness – without in turn compromising prosperity. Most people think, for example, that a good work–life balance makes you happy. And everyone knows that losing your job makes you unhappy, at least in the short term. However, countries such as France, which have legislated for greater job security and a shorter working week with long paid vacations, have felt the economic pinch. Rightly or wrongly, in 2007 the French population elected a new president on a ticket of employment reform in the belief that the economy would benefit. Happiness isn’t necessarily a vote-winner.

Curiously, several languages, including French, German, and Spanish, don’t fully distinguish between luck and happiness. The adjectives heureux, glücklich , and feliz can all be used to denote both luck and happiness. Yet the two concepts are very different in one fundamental way: although no one can change their luck, some people may be able to influence their happiness. Quite how to do so is not clear but some psychologists suggest that we’re getting there, slowly.

What we do know is that the quest for happiness drives many of our actions. Although money isn’t the answer, we’re not yet sure what is – even if sleep and chocolate both help. And despite the fact that we’re hopeless at predicting our own feel-good factors, we can take heart. Innate human adaptability usually reduces fluctuations in our happiness, at least in the longer term. Although happiness is, according to Aristotle, the most important human pursuit, “something complete and self-sufficient,” even he – in all his classical wisdom – couldn’t tell us how to achieve it. And we can’t either, except by suggesting that you spend more time playing golf (or any other similarly healthy activity that you enjoy) and less time making money. Apart from that, try to base decisions that will affect your future happiness on the experiences of others who have been in similar situations.

But we still can’t understand why some people, like Maria, are content while others, like Pilar, aren’t, or why the Bhutanese are so much happier than the Japanese. Is it the luck of the genetic draw or there are some deeper reasons that we’ll never fathom?

Throughout this book, we’ve had tantalizing glimpses of the power of the human mind: placebos that suppress acute pain; self-rated health questionnaires that are more accurate than doctors; years of dedication to attain grand-master status; how the destructive forces of creativity can be beneficial to our societies. At the same time we’ve presented the biases and limitations of our minds and their negative consequences on the way we make decisions and face future uncertainty, including the infamous illusion of control. These phenomena may be little understood and accepted, but they’re all part of our mental inheritance. Unfortunately, we can’t ignore them just because we can’t understand them or predict their consequences.

So it is with happiness. If it were straightforward, we’d be one hell of a lot better at managing it. But, as with our health and longevity, wealth and professional success, happiness is complex to the point of unpredictability. One fact about happiness is simple, though: as the old Scottish proverb goes, be happy while you’re alive for you will be dead for a long time.