4

Being one of us

Leaders as in-group prototypes

Reflect, for a moment, on the following “thought experiment.” You hear some other people laughing at a joke that, on the face of it, is not particularly funny. You then find out that the people who are laughing are fellow members of a group that you’re a part of and that you value. Would you laugh too? Now let’s say you found out that these laughing others are part of a group that you’re not a member of and, in fact, have no desire to be. Would you laugh along now? If you imagined yourself being more likely to laugh in the first instance than in the second, then you’d be confirming results of one of our own studies of canned laughter (Platow et al., 2005). In that study, people were influenced by the laughter of fellow in-group members, but not by the laughter of out-group members. This simple study demonstrates one of the key arguments in our analysis of leadership: we are influenced primarily by those who are in-group (rather than out-group) members. To influence others, one has to be accepted by them as “one of us.”

This, however, is only the starting point of our analysis of leadership. One reason for this is that, as we saw in the previous chapter, not all fellow in-group members have the same degree of influence over us. Some in-group members exert almost no influence at all, while others play a central role in defining reality for us. Clearly, we need to know more than just a person’s standing as an in-group or out-group member (whether they are one of “us” or one of “them”) in order to have a complete understanding of their leadership and influence.

As we saw in Chapter 2, many researchers have pursued this issue of relative influence by outlining specific qualities, attributes, and behaviors that leaders need to possess in order to be able to lead—things that set them apart from their followers and make them distinct. However, in contrast to this view, we noted in the previous chapter that the new psychology of leadership takes us down a very different path—suggesting that leaders need to have qualities, attributes, and behaviors that emphasize what they have in common with their followers, while at the same time differentiating them from other groups that are salient in a particular context.

In this chapter, we will elaborate on this point by showing how leaders succeed by standing for the group rather than by standing apart from it. To be sure, this still means that leaders need to display particular qualities and will be valued to the extent that they do. Importantly, though, these qualities are not valued because they are those of an independent individual. Rather, they are valued because they are qualities that epitomize the meaning of the group in context. Among other things, one consequence of this is that as the meaning of the group changes, so will the qualities required of a leader. As we will see, this also means that in order to understand the basis of effective leadership we need to move beyond a predilection for abstract lists of leader characteristics and instead develop an understanding of contextualized group dynamics.

The importance of standing for the group

One important implication of the above arguments is that anything that sets a leader apart from the group will undermine his or her effectiveness. For instance, in all the recent furore about pay for top executives, business leaders might want to ponder some of our own experimental evidence that shows that, as the rewards given to leaders and ordinary group members become increasingly unequal, so those ordinary members become less positive about their leaders and less willing to exert effort on behalf of the group (Haslam, Brown, McGarty, & Reynolds, 1998). This accords with survey evidence that greater pay differentials lead to higher staff turnover—especially among the lower paid (Pfeffer & Davis-Blake, 1992). It also accords with observations by the banker J. P. Morgan at the start of the 20th century that the only feature shared by his underperforming clients was a tendency to overpay those at the top of the company (see Drucker, 1986). Such differentials, felt Morgan, disrupted team spirit, led people in the company to see top management as adversaries, and discouraged them from doing anything that was not in their immediate self-interest.

Of course, however important it may be, both materially and symbolically, pay is only one of many dimensions along which leaders and followers may (or may not) be differentiated. The lessons of our studies and the wisdom of J. P. Morgan apply equally to any aspect of working experience. Thus, drawing on a qualitative study of restaurant operations, Virginia Vanderslice at the University of Pennsylvania concluded that the absence of rigidly differentiated leader–follower roles is a hallmark of high-functioning organizations with engaging and effective leadership (observations that echo points made by researchers like Jeffrey Nielsen, Warren Bennis, and Henry Mintzberg that we discussed in Chapter 2). On this basis Vanderslice concludes:

The very existence of leader–follower distinctions may have the effect of limiting motivation or directing motivation toward efforts of resistance…. While “good” leaders may be thought to be those who draw on the resources of members, leader–follower distinctions may encourage followers to believe they have fewer resources to offer and leaders to rely more heavily on their own resources…. The problem, then, is not the concept of leadership per se, but the operationalization of leadership in individualistic, static and exclusive positional roles that are supposedly achieved or assigned on the basis of expertise.

(Vanderslice, 1988, p. 683)

To take the argument one step further, there is provocative evidence that the very process of selecting leaders may, in itself, affect the relationship between leader and group and hence impact on the leader’s effectiveness even before he or she has started working. Notably, the process of competitive leader selection (something that is generally regarded as essential for identifying the best leaders and that has consequently spawned a massive industry; see Hughes, 2001) can, under some circumstances, break down a sense of shared identity. There are two reasons for this. First, from the perspective of followers, such competition can serve to mark out the leader as someone who is a different type of person from themselves. Second, from the perspective of the leader, such competition may subordinate consideration for the group as a whole to consideration for the personal self. In the scramble to promote the “I”, the “we” may get trampled underfoot.

These ideas were examined in a series of “random leader” studies that the first author conducted with colleagues at the Australian National University in the 1990s (Haslam et al., 1998). These involved groups of three or four participants performing tasks that are customarily used to investigate leader effectiveness. These required groups to decide what articles to rescue from a plane that had crashed in a frozen lake (the “winter survival task”) or in a desert (“the desert survival task”; Johnson & Johnson, 1991). Group leaders were chosen on either a formal or a random basis, or (in Experiment 2) the groups had no leader at all. In both studies, random leader selection involved appointing the person whose name came first in the alphabet to be leader, while formal leader selection was made on the basis of participants’ responses to a “leader skills inventory.” In this inventory individuals rated their own talents on a range of dimensions that previous research claimed to be predictors of long-term managerial success (Ritchie & Moses, 1983). Specifically, participants had to respond to questions like “How well do you communicate verbally?”, “How aware are you of your social environment?”, and “How good are your organizational and planning skills?” The individual with the highest score on this measure was then appointed leader.

The impact of these selection strategies was then assessed on two indices of group productivity that classic work by Dorwin Cartwright and Alvin Zander (1960) identified as the primary benchmarks by which group performance— and hence leadership—needs to be assessed: (1) the achievement of a specific group goal, and (2) the maintenance or strengthening of the group itself. In this case, this meant assessing whether the group’s decisions helped it to survive in the frozen wilderness or in the desert, and whether group members were willing to abide by those decisions (rather than defecting at the first opportunity).

Although the study did not set out to demonstrate that the process of systematically selecting group leaders is generally counter-productive, we hypothesized that this might be the case in the particular conditions that prevailed in this study—where, in the absence of a leader being chosen, the group already had a sense of shared social identity and was already oriented to a well-defined shared goal. This hypothesis was confirmed. In both studies the groups with random leaders out-performed those with formally selected leaders. As the data in Table 4.1 show, in the second study they also outperformed groups with no leaders and exhibited greater group maintenance. What this meant was that when given the chance to walk away from the group’s decisions, individuals in groups with formally selected leaders were more likely to take this opportunity than those whose leader had been chosen randomly. In effect, then, when group leaders had been chosen on the basis of a talent quest, those who failed in this quest turned their back on those who were successful—as if to say “Well if you’re so wonderful, why don’t you get on with it?”

Taken as a whole, the findings from these studies serve to question the belief that the process of systematic leadership selection is always in the interest of better group performance. Under conditions that we have specified (where there is an existing identity, a clear group goal, and a democratic ethos) it may actually do harm. It was precisely this realization that led the coach of the Australian women’s hockey team in the 1990s, Ric Charlesworth, to avoid going through the process of appointing a team captain—a strategy to which he subsequently attributed much of the team’s considerable success.1

What emerges from this evidence, then, is that distance between the leader and the group is not only bad for leader effectiveness, it is also bad for the effectiveness of the group as a whole. Although this goes against much of the theory and practice in the leadership field, this is a critical message. Yet, to be fair, it is hardly a new observation. In particular, over half a century ago, Muzafer Sherif and colleagues in the United States conducted a series of

seminal studies with boys attending summer camps (Sherif, 1956, 1966). In the course of the studies, two teams of boys engaged in competition for valued prizes and in the most well-known study (conducted at Robbers Cave in Oklahoma) the researchers constructed sociograms in order to chart the patterns of friendship and liking within the two teams. Among other things, these allowed the researchers to map the amount of hierarchical differentiation between the individual group members, and thereby depict how much the group as a whole was differentiated in terms of status (based on liking for various different group members). The findings here were very clear: differentiation between leaders and followers was much higher in the losing group (the “Red Devils”) than it was among the winners (the “Bulldogs”; see Figure 4.1).

Having leaders who are set apart from the group thus appears to be a feature of groups that fail not of those that succeed. This is not to say that leaders cannot be different or creative, only that their difference and creativity must be seen to promote rather than to compromise the interests and identity of the group. Support for this point emerges clearly from a recent program of

Figure 4.1 Sociograms from the Robbers Cave study (from Sherif, 1956). Reprinted with permission. Copyright © 1956 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.

Note: The vertical axis represents the social distance between group members. This distance was smaller for members of the winning group (“Bulldogs”) than for the losing group (“Red Devils”). As Sherif noted, “Bulldogs had a close-knit organization with good team spirit. Low ranking members participated less in the life of the group but were not rejected. Red Devils … had less group unity and were sharply stratified.” (1956, p. 57).

work conducted by Inma Adarves-Yorno and her colleagues at the University of Exeter (Adarves-Yorno, Postmes, & Haslam, 2006, 2007). Among other things, this research demonstrates that in order for a creative act to be seen as such and to be valued by group members it needs to fall within the boundaries of normative group behavior and be performed by someone who is clearly defined as “one of us” (i.e., an in-group member). Significantly too, this work has shown that products developed by in-group members are perceived to be more creative than those developed by out-group members, independently of other factors that might be expected to determine such judgments (e.g., product quality; Adarves-Yorno, Haslam, & Postmes, 2008).

We will return to this critical issue of creativity just before we conclude this chapter. At this point, we simply want to underline our starting message. To take groups, organizations, and societies forward, individuals need to be integrated elements of group life rather than remote and distant isolates (von Cranach, 1986). Groups have little need for maverick leaders who are intent on “doing their own thing” with no heed to the concerns of the team as a whole. This is one reason why autocratic leadership styles and non-participatory leadership practices that fail to appeal to shared interests and goals generally lead to group outcomes that are inferior to those achieved by styles and practices that are more democratic and participatory (e.g., Lewin, Lippitt, & White, 1939; Lippitt & White, 1953).

The limitations of autocratic forms of leadership can also be attributed to the fact that these tend to rob followers of any sense that they have ownership of the tasks in which they are engaged—leading them to feel that they are working for someone else rather than for themselves. Here motivation is extrinsic (rather than intrinsic) and followers expend energy because they have to rather than because they want to (Ellemers et al., 2004). Indeed, this is a key reason why autocratic leadership typically requires constant surveillance in order to achieve its effects. We can therefore add one final element to our analysis of why it is necessary for a leader to be included as “one of us” rather than distanced as “one of them.” As well as making both leadership and the group more ineffective, greater distance from the group also requires more resources to produce inferior output. Whether one is referring to business, politics, or any other form of organization, this is the perfect recipe for mediocrity.

Prototypicality and leadership effectiveness

“Being one of us” may well be our starting point. But we cannot let things rest there. One reason for this is that not all fellow in-group members have the same degree of influence over us. Some in-group members exert almost no influence at all, while others play a central role in defining reality for us. And sometimes (as Winston Churchill found out to his cost when his reward for winning the war was losing the British general election of 1945) leaders who are highly influential in one situation lose their influence in another. In order to have a complete understanding of a person’s leadership and influence, we therefore need to establish a relative influence gradient that will allow us to anticipate and explain the relative influence of different in-group members. Moreover, we also need to know when, how, and why this influence gradient will change across different contexts.

We noted above that traditional ways of tackling this issue have involved identifying specific qualities, attributes, and behaviors that individuals need to possess in order to be able to lead. In older work, the emphasis was on the personality traits that a successful leader requires. In more contemporary literature, the emphasis has been on the need for leaders to match stereotypes of what a leader should be like (e.g., Lord & Maher, 1991). Even if it is accepted that these stereotypes might change over time, it is still assumed, first, that the traits a leader must display are relatively stable, and, second, that there are certain relatively enduring characteristics that all leaders need. These include intelligence (Judge, Colbert, & Ilies, 2004; Lord, de Vader, & Alliger, 1986), even-handedness (e.g., Michener & Lawler, 1975; Wit & Wilke, 1988), and charisma (Bono & Judge, 2004). Some studies also suggest that physical features like height have an important role to play (Judge & Cable, 2004)—although it is clear that height was not a factor that assisted Napoleon Bonaparte (5′ 6″), Haile Selassie (5′ 4″), Queen Elizabeth I (5′ 4″), Yasser Arafat (5′ 2″), Queen Victoria (5′ 0″), or Joan of Arc (4′ 11″).

Self-categorization theory, however, approaches the issue of an influence gradient in a very different manner. It suggests that leaders need to have qualities, attributes, and behaviors that emphasize what makes them the same as their followers, while differentiating them from other groups that are salient in a particular context. Our explication of this point proceeds in two phases. In the first and most extensive section, we will show how relative prototypicality explains which leaders will be effective in a group and why leadership effectiveness varies with context. Second, we will examine the relationship between prototypicality and leadership characteristics. On the one hand, we show how the importance of supposedly core leadership characteristics varies in ways that are predicted by prototypicality processes. However, on the other hand, we show that prototypicality processes explain how it is that leaders are seen to have characteristics such as intelligence and charisma that can enhance their attractiveness to followers.

Understanding prototypicality in context

Consider the results of a national opinion poll that was conducted just a week before the US presidential election of 2000 (CBS News, 2000). In this election the candidates from the two major political parties were George W. Bush and Al Gore. Although Gore lost the election, generally speaking, the majority of respondents (59%) agreed that he was highly intelligent, whereas the majority (55%) thought that Bush was of only average intelligence. What is even more telling is that a sizeable proportion (28%) of Bush supporters rated Gore as more intelligent than their own candidate. Why, then, did they continue to vote for Bush? The question is of more than passing interest, because had people chosen leaders on the basis of supposedly key characteristics like intelligence, Gore would have won by a landslide and we would be living in a very different world today. The answer perhaps lies in the fact that, when confronted with a very intelligent out-group leader, Bush supporters devalued this quality in their own candidate and focused on other dimensions on which they perceived Bush to be superior to Gore. So, whereas 72% of Gore supporters said they wanted a president with above-average intelligence, this was true for only 56% of Bush supporters. Group members thus sought to differentiate their leader from the out-group leader, even if it meant forgoing what is typically seen as a core leadership quality.

Consider, next, the fate of one of Bush’s most important lieutenants— Donald Rumsfeld—who emerged as an important leadership figure during the 2003 war in Iraq. Prior to the war, Rumsfeld had “looked like an extinguished volcano” and US newspapers were speculating on his likely successors (Parker, 2003, p. 55). Later, once the conflict had receded and the evidence for Iraqi weapons of mass destruction was revealed as a mirage, he lost the mantle of leadership (and the office of leader) and receded into the political shadows. Why did Rumsfeld experience these reversals in fortune? We would suggest it is because, at the time of the war, the values and goals that he espoused matched the terms of an American identity defined in counter-position to Saddam Hussein’s allegedly threatening tyranny. Most obviously, he represented a hawkish America in which conciliation could be portrayed as betrayal. As summarized in The Economist,

Mr. Rumsfeld is one of the most conservative members of a conservative club…. He is “one of us” in a way that Colin Powell could never be.

(Parker, 2003, p. 55)

Yet as the context in which America was defined changed over time, so too the values that defined America changed. Now Rumsfeld’s values became unrepresentative. In this sense, we see that Rumsfeld’s rise and fall as a leader derived not from his individuality, but rather from his success and failure in representing a national identity that changed dramatically in a relatively short space of time. At the height of his influence his aggressiveness was seen to represent “the best of us” (i.e., US desire to fight terrorism and tyranny); but as this waned it was seen to represent “the worst of us” (i.e., US contribution to terror and tyranny; see Cockburn, 2007).

These examples suggest three things. First, the effectiveness of leaders is tied to their in-group prototypicality; second, that in-group prototypicality is not a set characteristic of “us” but rather a function of how “we” relate to “them”; third, as the nature of “them” changes, so does the in-group prototype and hence the qualities that mark out a person as a leader. Let us examine these ideas further in order to understand how the concept of in-group prototypicality (as specified by self-categorization theory) helps us to understand the variability in leadership qualities that we observe both in the laboratory and in the wider world.

As we emphasized in the previous chapter, the critical point to stress is that self-categorization theory provides a dynamic model of group processes whereby, far from being set in stone, “who we are” varies as a function of those with whom we are compared (e.g., see Figure 3.4). It follows from this that the things that allow someone to represent us, to speak for us, and hence to influence us will equally depend on the comparative context. These broad (but revolutionary) ideas are captured in the notion of in-group prototypicality. As originally described by Turner (1987, p. 80):

[Prototypicality] varies with the dimension(s) of comparison and the categories employed. The latter too will vary with the frame of reference (the psychologically salient pool of people compared) and the comparative dimension(s) selected. These phenomena are relative and situation-specific, not absolute, static and constant.

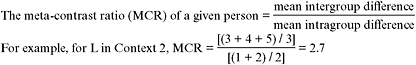

In the same way that category salience depends on what group best distinguishes who we are from who we are not, so the question of what position best defines the group is also a function of what best distinguishes “us” from “them”—and, again, this is formally captured by the concept of meta-contrast. This suggests that any given individual will be more representative of an in-group to the extent that his or her average difference from out-group members is larger than his or her average difference from fellow in-group members. This means that, if a particular in-group member is very different from the out-group while being very similar to fellow in-group members, then the meta-contrast ratio (MCR) becomes very large; and the larger this value is, the more in-group prototypical he or she will be of the in-group as a whole.

To see more closely how this principle works, we can imagine a situation in which people are defined along a political dimension from “socialist” on the left to “conservative” on the right. Now imagine that a centrist political group sits at the center of this continuum, with one member exactly at the center (C), a second member slightly to the right (R), and a third member slightly to the left (L). In a context where salient out-groups occupy the full political spectrum (Context 1 in Figure 4.2), C is the most prototypical of this centrist group. This is because the differences between C and both socialist and conservative out-groups are large relative to the differences between C and his fellow in-group members. By contrast, the ratio of between-group differences to within-group differences is not as large for either R or L. Accordingly, other things being equal, we would predict that in this context C best exemplifies what this centrist group “means” or “stands for” and hence will exert the greatest influence over other group members. In other words, as the most prototypical group member, C is best placed to define the group and hence to play a leadership role within it.

Figure 4.2 Variation in in-group prototypicality as a function of comparative context (adapted from Turner & Haslam, 2001).

Note: L = Left-wing candidate, C = Centrist candidate, R = Right-wing candidate, o = salient out-group positions

The important point to note in this example is that the relative prototypicality of L, C and R varies depending on the frame of reference. In particular, when an out-group is concentrated to one side of the in-group (as in Contexts 2 and 3), the in-group member who is furthest away from that out-group (L in Context 2, R in Context 3) gains in prototypicality.

Now look at Contexts 2 and 3 in the same figure. Here the political spectrum has changed so that this centrist group is confronted only with a conservative out-group (Context 2) or only with a socialist out-group (Context 3). What we also see here is that the relative in-group prototypicality of R and L has changed. In both cases C remains the most in-group prototypical. But L gains substantially in prototypicality (at the expense of R) when there is only an extremely conservative out-group (Context 2), while R gains in prototypicality (at the expense of L) when there is only an extremely socialist out-group (Context 3). This is because in Context 2 L is very different from the conservative out-group, while in Context 3 R is very different from the socialist out-group.

Thus if the extent of a person’s relative influence and hence his or her ability to fulfill a leadership role is determined by relative in-group prototypicality, then C’s authority should be most secure when the group is defined relative to groups occupying the full political spectrum (Context 1). However, this same person would be more open to challenge from the left-winger L if the party confronted only right-wing opponents (Context 2), while he would be more likely to face a challenge from the right-winger R in the context of conflict with a left-wing group (Context 3).

This is obviously a very contrived example. Moreover, it needs to be emphasized that because comparative context (meta-contrast) is only one determinant of prototypicality, in the world at large things are typically much more complex than this (as we will see in Chapter 6). Nevertheless, the important theoretical point that emerges from this example is that the prototypicality of exactly the same individual for exactly the same social group can vary as a function of the broader social context within which that group is defined. This suggests that the ability of individual group members to influence others (i.e., to exert leadership) can rise and fall without any change in their underlying qualities, attributes, or behaviors. This helps us to understand why it is unproductive to suppose that leaders are defined by a set of specific qualities, attributes, and behaviors that serve generally to differentiate them from their fellow group members (e.g., as suggested by Conger & Kanungo, 1998). Indeed, in contrast to this supposition, our analysis suggests that leaders are defined by the specific set of qualities, attributes, and behaviors that—within any given context—serves to minimize their differences from fellow in-group members while simultaneously maximizing their differences from out-group members.

Prototypicality, influence, and transformation

We must be careful, however, not to make premature claims. The examples in the previous section suggest that prototypicality determines who and what people look for in a leader, but they don’t explicitly demonstrate that highly prototypical leaders are more influential than less prototypical leaders. Because influence is so central to our analysis of leadership, this demonstration is central to our case. Fortunately, though, a number of carefully controlled experimental studies provide substantial evidence to support this claim.

An early demonstration of the point that a person’s capacity to influence fellow group members varies as a function of his or her in-group prototypicality was provided by Craig McGarty, John Turner and their colleagues (McGarty, Turner, Hogg, David, & Wetherell, 1992). These researchers conducted experiments that started by asking participants about their personal attitude towards a range of topics in order to establish what the prototypical in-group attitude was in a variety of attitudinal domains (e.g., attitudes toward nuclear power, capital punishment, and the legalization of cannabis). A week later the participants came back and were put into groups where they discussed these issues. After the discussion was over, they then indicated their own personal attitudes for a second time. The in-group prototypical attitudes were established for each group on the basis of the attitudes that they expressed in Phase 1 using the meta-contrast ratio described above. In two separate studies, with different attitudes and different participants, the researchers observed statistically significant and strong relationships between the in-group prototypical attitudes in Phase 1 and individuals’ post-discussion attitudes in Phase 2. In short, after group discussion, the group members aligned their own private attitudes with those that were in-group prototypical.

Further demonstration of the role that relative in-group prototypicality plays in determining a person’s ability to influence others is provided in important work by Mike Hogg and Daan van Knippenberg (e.g., Fielding & Hogg, 1997; van Knippenberg, Lossie, & Wilke, 1994; van Knippenberg & Wilke, 1992). Indeed, Hogg and van Knippenberg have done much to popularize self-categorization theory’s claim that the influence of leaders derives from their status as in-group prototypes (Hogg, 2001; Hogg & van Knippenberg, 2004). In one representative study, the researchers presented law students with arguments for and against university entrance exams (van Knippenberg et al., 1994). These arguments were said to have been generated by another student who was described as being either in-group prototypical or in-group non-prototypical along another attitudinal dimension (views about the amount of time students should be given to complete their degrees). Consistent with predictions derived from self-categorization theory, the participants aligned their own private attitudes more closely with the communication from the in-group prototypical source than with that from the in-group non-prototypical source, regardless of the position for which he or she was arguing (i.e., for or against the exams). The capacity for arguments to shape the opinions of others was thus contingent on the student who presented them being seen to be “one of us” (see also Reid & Ng, 2000).

Studies like these provide clear support for the causal relationship between people’s in-group prototypicality and their ability to influence fellow group members. The more in-group prototypical a person is, the more influential he or she will be. Moreover—remembering that “capacity to influence group members” is the defining feature of leadership—this means that the most in-group prototypical group member is the one who is best positioned to evince most leadership.

Note too, that this analysis provides a more nuanced appreciation of our claim that it is in-group not out-group members who are influential and who emerge as leaders. For while, almost by definition, in-group members will tend be more in-group prototypical than out-group members, there will be occasions when changes in social context lead to the redefinition of group boundaries such that those who were formerly categorized as out-group members come to be redefined as in-group members. Where this happens, there are reasons to imagine that the emerging leadership of those who had previously been understood to be out-group members would be seen as genuinely transformational in the sense implied by Burns (1978; see also Lord, Brown, & Freiberg, 1999; Shamir, House, & Arthur, 1993).

Evidence of this process at work in the world is provided by the dramatic changes that occurred in South Africa in the early 1990s. During the Apartheid regime the nation had been divided sharply along the lines of skin color—so that for most Whites, Blacks were a clearly defined out-group. However, as the Apartheid system was brought to an end many individuals who were previously categorized by Whites as out-group members came to be understood as prototypical of the emerging “rainbow nation” and to exert (transformational) leadership on that basis. Most particularly, arm-in-arm with sweeping political change, it was this recategorization process that brought leaders like Nelson Mandela and Bishop Desmond Tutu to the fore. A vivid description of this process in action is provided by John Carlin (2008, p. i) in his analysis of the way in which the game of rugby provided a field on which these dynamics were played out:

During apartheid, the all-white Springboks and their fans had belted out racist fight songs, and blacks would come to Springbok matches to cheer for whatever team was playing against them. Yet Mandela believed that the Springboks could embody—and engage—the new South Africa. And the Springboks themselves embraced the scheme. Soon South African TV would carry images of the team singing “Nkosi Sikelele Afrika,” the longtime anthem of black resistance to apartheid…. South Africans of every color and political stripe found themselves falling for the team. When the Springboks took to the field for the championship match against New Zealand’s heavily favored squad, Mandela sat in his presidential box wearing a Springbok jersey while sixty-two-thousand fans, mostly white, chanted “Nelson! Nelson!”

In Chapter 6 we will consider in more detail how would-be leaders can manipulate people’s understanding of context with a view to bringing about sweeping change of this form. For now, though, we should note that this example confirms the point that transformational leadership does not follow straightforwardly either from the personality or actions of a leader or from the fixed perceptions and beliefs of their followers. Rather, it can be seen to arise from the forging of a shared social identity around a new definition of the group that the leader comes to embody. In short, it is by becoming emblematic of a new sense of “us” that leaders acquire their transformational power.

At this point, we can again state—this time with more confidence—that we have found a solution to the enigma of the shifting influence gradient. It would be tempting, then, to rest on our laurels. But the skeptic might reasonably object that there is more to leadership than influence. Indeed, if leaders succeed in getting people to do their bidding, only at the cost of deteriorations in other spheres of group life, then this could turn out to be a very hollow victory. For this reason it is worth mentioning some particularly striking findings reported by the Rome-based research team of Lavinia Cicero, Antonio Pierro, and Daan van Knippenberg (2007). They were concerned with the question of how leadership behavior affects the overall satisfaction of group members. To examine this question they conducted a study with workers in a number of different areas—hospital employees, military officers, and call-center workers. First, the researchers assessed employees’ perceptions of their team leader’s in-group prototypicality—asking, for example, whether the leader “is a good example of the kind of people that are members of my team.” They then assessed the workers’ overall level of job satisfaction (e.g., by seeing whether they agreed with the statement “I find real enjoyment in my work”) as well as their level of social identification with their work team (e.g., seeing if they agreed with statements such as “When I talk about my team, I usually say ‘we’ rather than ‘they’ ”). As predicted, the more in-group prototypical these workers saw their team leader as being, the more satisfied they were with their jobs. Moreover, this effect was particularly strong among workers who identified more strongly with their team—that is, among people for whom this particular group membership was important.

In this way, Cicero and colleagues’ data show clearly that having in-group prototypical leaders is associated with greater job satisfaction. Along similar lines, an earlier study by Fielding and Hogg (1997) showed that leaders who were seen as more prototypical were also seen to be more effective. In line with self-categorization theory, one reason why this is to be expected is that leaders who embody our sense of “who we think we are” are more likely to make us feel good about the work that they, as leaders, are asking us to do. Among other things, this is because we are likely to find such work collectively self-actualizing—so that, by working for the leader, we are also promoting the types of things that count for “us.” Indeed, in this sense, to work for an in-group prototypical leader is to work for oneself (i.e., one’s collective self). This is psychologically very different from working for someone else (i.e., a leader who does not represent the self). Overall, then, it appears that more prototypical leaders are not only seen as better leaders but are also more effective in getting us to do things and in making us feel good about doing those things. This is a blessed trinity.

Prototypicality, extremism, and minority leadership

To conclude this survey of the impact of prototypicality on leadership, we turn to a question that is of pressing importance both in politics and in society at large. This concerns the conditions under which different types of leader come to the fore. Why is it, we ask, that at some points in time, groups favor leadership that is moderate, while at other times they prefer leadership that is more extreme? In recent years, this general question has also led to a number of more specific ones. Why do peaceful and temperate crowds sometimes come under the sway of violent members in their midst, so that they become confrontational and aggressive? Why has Muslim leadership been radicalized by the “War on Terror”? Why does faith in democracy sometimes give way to a desire for autocratic leadership?

Based on the arguments outlined above, we can start to answer such questions by looking at the way in which changes in social context empower those who represent moderate or extreme group positions to exert influence over their fellow group members. Indeed, this was the thrust of our discussion of Figure 4.2 in which we saw how the extremists L and R gained in prototypicality relative to the moderate C when the comparative context included only out-groups at the opposite end of the political spectrum. This demonstration suggests that extremists are much more likely to exert influence over a group when that group is locked into conflict with a clearly defined out-group, so that for members of that group the world is defined starkly in “us and them” terms.

A large body of empirical research has provided evidence of precisely this point. In the laboratory, a program of studies by Barbara David and John Turner (1996, 2001) into the phenomenon of minority influence has shown how the capacity for radical feminists to exert influence over more moderate members of the women’s movement varies predictably as a function of social context. In settings where only feminists were present and salient, the researchers found that those who were in a radical minority exerted very little influence over other women. Yet as the comparative context was extended to include anti-feminists, other women became much more receptive to the separatist message that this radical minority espoused. In the former context there was thus very little enthusiasm for the idea that women might be better off without men altogether. However, this idea—and those who promoted it—gained in appeal once women’s minds had become focused on an out-group who wanted to eliminate feminism.

In the field, these same dynamics have been explored in studies of crowds of football supporters. In particular, work by the second author along with his colleagues Clifford Stott, John Drury, Paul Hutchison, Andrew Livingstone and others has studied the way in which intergroup relations determine the role that different individuals and sub-groups play in defining a crowd’s actions towards other groups (e.g., the police or supporters of rival teams; Reicher, 1996; Stott et al., 2007; Stott, Hutchison, & Drury, 2001; Stott & Pearson, 2007; see also Reicher, 2001; Reicher, Drury, Hopkins, & Stott, 2001).

In an early study, Reicher (1996) examined the dynamics of a student demonstration outside the British Houses of Parliament in Westminster that ultimately turned into a riot. At first, the majority of participants saw themselves as “respectable” members of society who were simply trying to get their message over to Parliament. They explicitly avoided radical groups who were urging confrontation with the authorities. However, the police saw the demonstrators as constituting trouble and, more importantly, they treated the demonstrators as an undifferentiated out-group—in particular, denying all of them the right to lobby their representatives in Parliament. As a result of this, the demonstrators redefined their relationship with the police as one of antagonism and, in this new context, those who advocated confrontation became more prototypical and more influential. As Reicher shows through close examination of participants’ behavior as it unfolded over the course of the demonstration, it was this emergent leadership of more radical elements that turned peaceful protestors into radicalized rioters.

Clifford Stott and colleagues have shown similar dynamics to be at work in an elaborate series of studies into the interactions of police and fans at football matches (Stott et al., 2001). In the 1998 World Cup, for instance, England fans were seen and treated as troublesome by both the local French population and by the police. As a result, fans who initially eschewed violence drew closer and closer to more violent fans, who thereby gained more and more in influence. By contrast, Scottish fans were seen and treated as boisterous but essentially good natured. They met with friendship from locals and police, and even their excesses were treated indulgently. Hence, if any individual Scot sought out confrontation, not only did they get no support, but they were actively stopped by their fellow fans.

Going one step further, Stott sought to put these insights into practice during the 2004 European Football Championships in Portugal (see Figure 4.3). In one part of the country, he and his team (see Stott et al., 2007) trained the police to interact positively with fans, to treat them with consideration, and to do what they could to meet fans’ legitimate needs. In another part of the country the team made no intervention and traditional public order tactics were used. These involved maintaining an intimidating presence on the streets and deploying “zero tolerance” tactics. Stott then examined the dynamics of interactions between the police and England fans in these two areas. In the area where Stott had intervened, there were certainly occasions when individuals acted aggressively. But in no case did they exert influence over other fans and so the police found them relatively easy to manage. Indeed, in many cases this was because other fans intervened to ensure that these individuals did not cause trouble. By contrast, in the area where traditional methods were used there was a growing antagonism between police and fans. In particular, there were two occasions where the police clamped down indiscriminately on England fans after some started behaving rowdily. When some fans responded by attacking the police, others joined in. On both occasions this dynamic led to full-blown riots.

So what was going on here? In analytic terms, a measured police strategy created a context in which “hooligans” were not prototypical England fans and hence, while undoubtedly still present, they had little or no success in leading other fans into conflict. By contrast, a “hard-line” police strategy created a social context that made “hooligans” more prototypical of the fans’ in-group and allowed them to lead their peers into rioting. This work is a powerful illustration of prototypicality dynamics in action, but it also confirms Kurt Lewin’s (1952) famous adage that there is nothing as practical

Figure 4.3 English football fans at the 2004 European Football Championships in Portugal (Stott et al., 2007). Used with permission.

Note: In locations where fans’ identity came to be defined in opposition to the “hard-line” police, “hooligans” became more prototypical of this identity and hence came to exert more leadership over the group. This led to rioting that was not observed in locations where police had been trained by the researchers to use more measured tactics and where “hooligans” were brought into line by more moderate fans.

as good theory—for Stott’s advice derived directly from the principles of self-categorization theory that we are currently describing.

Yet the operation of these dynamics is not restricted to relations between relatively small groups on the ground. They are also at play in relations between whole populations. Along these lines, a number of commentators have noted that, far from alleviating difficulties and tensions, hard-line international policy can actually promote conflict by cultivating support for extremist elements among one’s adversaries. Indeed, this dynamic has been particularly apparent in the escalating “War on Terror” following the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center in New York. While this initiative was supposed to crush the terrorist organizations that perpetrated such acts (e.g., by imprisoning in Guantanamo Bay those suspected of links to Al-Qaeda and its leader Osama bin Laden), in fact it can be seen to have strengthened them by uniting Muslims around a sense of illegitimate persecution, and a leadership that would avenge this perceived injustice. Writing for the Arabic news organization Aljazeera, Ivan Eland thus concluded:

The administration’s war on terror has played right into Osama bin Laden’s hands. A common strategy of terrorists is to strike the stronger aggressor, hope for an overreaction, and thus gain zealous recruits and funding for the terrorists’ cause…. The administration’s highly publicized cowboy invasions and occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq were overreactions that must have put a smile on bin Laden’s face.

(Eland, 2008, paras. 9, 10)

Again and again we return to the same fundamental point: leadership is not vested in leaders alone but rather results from the contextual dynamics that create a sense of unity between them and their followers. For their leadership to succeed, extremist leaders (just like moderate ones) must stand for the group not apart from it. In the absence of this, they will be dismissed as irrelevant eccentrics or as a lunatic fringe (just as Hitler and the Nazi Party were in 1920s Germany; see Evans, 2003). This is a point that the co-writer of The Communist Manifesto, Friedrich Engels, appreciated very well when he observed that:

The worst thing that can befall a leader of an extreme party is to be compelled to take over government in an epoch when the movement is not yet ripe for the domination of the class he represents and for the realization of the measures which that domination would imply…. (For) he is compelled to represent not his party or his class, but the class for whom conditions are ripe for domination.

(Engels, 1850/1926, pp. 135–136; see also Daniels, 2007, p. 78)

Engels’ point was that a leader with an extremist agenda will be ineffective if this agenda makes no sense to the group that he or she is trying to lead. If they are to succeed, then, at the very least, that agenda will have to be watered down. Revolutionary leaders thus often have to compromise their principles in order to appeal to a broad base, but if they do this then they stand to lose their credibility as revolutionaries. Indeed, as the Soviet historian Robert Daniels (2007) observes, this is one reason why it typically proves difficult for someone to lead a group into a revolution and to maintain his or her leadership once the revolution has been successful (see also Hobsbawm, 1999).

Prototypicality and leadership stereotypes

Leader stereotypicality is subordinate to in-group prototypicality

The work we have discussed in this chapter is representative of a considerable body of evidence that supports the notion that the qualities we look for in leaders are a function of variable group prototypes. It follows from this that there is no point in trying to identify a specific set of qualities that a leader must possess, or in trying to identify fixed stereotypes to which they should conform. The evidence that leads to this conclusion is all the stronger for being drawn from very diverse sources: laboratory experiments, field studies, and historical examples. Yet it could still be argued that, in many cases, we have stacked the odds in our favor. Perhaps leaders who are seen as prototypical are influential not because they are prototypical but because they conform to particular leadership stereotypes. A more conclusive demonstration of the distinctive importance of in-group prototypicality would therefore involve conducting a study in which this variable is pitted directly against leader stereotypicality. Studies by researchers at the University of Queensland set out to perform critical tests of exactly this form. Specifically, Sarah Hains, Mike Hogg, and Julie Duck (1997) developed an experimental paradigm in which university students were asked to consider arguments for and against increased police powers. In “high-salience” conditions (but not “low-salience” conditions), the group was made psychologically important to its members by leading the students to believe that they would be discussing ideas in a group with other like-minded students, and asking them to develop arguments in support of their group’s views. Participants then read about a randomly chosen leader who was either representative or unrepresentative of their group’s views (i.e., in-group prototypical or in-group non-prototypical), and who had described him- or herself as either having or not having stereotypical leader qualities. In particular, this description made reference to behaviors such as emphasizing group goals, planning, and communicating with other group members that previous research by Cronshaw and Lord (1987) had suggested were typically associated with effective leadership (akin to work in the behavioral tradition that stresses the importance of initiation of structure and consideration; e.g., Fleishman & Peters, 1962; see Chapter 2).

In line with leader categorization theory and previous work in the behavioral tradition, the researchers found that leaders were generally seen as more effective and as more appropriate to the extent that they engaged in leader-stereotypic behavior. But in line with hypotheses derived from self-categorization theory, when the group was highly salient what really mattered to group members was whether the leader was prototypical of the group. This was more important than whether the leader displayed leader-stereotypic characteristics.

Thesefindings are complex but they suggest two things. First, the behavior of a leader matters most to the people in a group when that group is psychologically important to them. Second, under these circumstances, what is even more important is that the leader represents what the group stands for. As Hogg, Hains, and Mason (1998) conclude on the basis of a series of follow-up studies that replicated these findings:

As group membership becomes increasingly salient, people base their leadership perceptions less reliably on whether a person has generally stereotypical leadership qualities, and more significantly on the extent to which the person fits the contextually salient in-group prototype.

(p. 1261)

In short, when push comes to shove, it matters more that a leader looks like “one of us” than that he or she looks like a “typical” leader.

Leader stereotypicality is a product of in-group prototypicality

The foregoing discussion suggests that there are some critical contexts in which the stereotypicality of leader behavior—the extent to which a leader conforms to stereotypic expectations of how leaders should behave—is less important than some previous analyses suggest (e.g., Lord & Maher, 1991). But does this mean that there is no relationship between a person’s leader stereotypicality and his or her leadership? Not at all. Indeed, we do not question the importance of leadership stereotypicality. What we do question are the primacy and sufficiency of leader-stereotypical qualities, attributes, and behaviors in the leadership process. That is, we suggest that the effects of stereotypicality can only be understood in relation to processes of prototypicality. Rather than pitting the two factors against each other—as thesis and antithesis—it might therefore prove more productive to produce a synthesis based on how they operate together.

As a starting point for such a synthesis, it is worth recounting the comments of a local Republican Party boss when he was asked about the meaning of “Americanism”, which his candidate, Warren Harding, was advocating in the 1920 presidential race. “Damned if I know,” he replied, “but you can be sure it will get a lot of votes” (Dallek, 2003, p. 158). Harding himself echoed these thoughts in the much-quoted line: “I don’t know much about Americanism, but it’s a damn good word with which to carry an election.”2 The causal sequence here is quite clear. Those who successfully claim to embody the group are those who come to be seen and supported as leaders. It is not that those who look like leaders come to be seen as embodying the group. In this case, then, what mattered was that the would-be leader of Americans exemplified “Americanism” (whatever this might mean), not that he possessed some clearly specified and fixed “American” attributes.

Yet these are strong claims to rest on anecdotal foundations. Fortunately, again, they are backed up by a body of evidence obtained from survey and laboratory studies. In particular, three interrelated programs of research have sought to identify the source of the leader-stereotypical qualities of trustworthiness, fairness, and charisma. Let us consider each of these in turn.

Trustworthiness

A leading website that provides a list of quotes for speakers includes the observation from the physicist Stephen Hawking that “leadership is daring to step into the unknown.” The rather obvious point, however, is that “daring to step into the unknown” is not only associated with leadership. It is also associated with followership. And as the recent activities of leading global financiers have demonstrated, in this it can also be a forerunner to personal and collective ruin. Accordingly, whatever else it is, for followers, “daring to step into the unknown” is a reflection of one fundamental factor: trust. As Stephen Robbins (2007) has observed, trust is therefore essential to leadership. If followers do not believe that their leaders are trustworthy, they will not follow them.3

These observations may all seem quite self-evident. Indeed, they may appear to be more statements of fact than statements of theory. However, our concern here is not whether the trustworthiness of a would-be leader is important, but whether this trustworthiness is a characteristic of leaders that drives our commitment to them, or whether instead it is a consequence of those leaders’ capacity to embody group memberships that are important to us. Do we follow our leaders because we trust them, or do we trust them because they are our leaders?

In fact, from work that we alluded to in Chapter 3, we know already that the perceived trustworthiness of another person is a consequence of shared group membership. There we noted that people tend generally to see members of their in-group as more trustworthy than members of out-groups (e.g., Doise et al., 1972; Platow et al., 1990). An additional question, then, is whether in-group members will be seen to be more trustworthy to the extent that they are in-group prototypical.

To examine this issue, Steffen Giessner and Daan van Knippenberg (2008) surveyed working people from 11 different countries, asking them to think about a leader they had experience of in the past, and then to rate that leader in terms of his or her in-group prototypicality and trustworthiness. As expected, the more the leaders were seen to be prototypical of the in-group, the more they were trusted by the respondents. However, these data are only correlational. So in order to establish whether in-group prototypicality plays a role in causing group members to trust a leader, Giessner and van Knippenberg conducted a laboratory experiment in which the leader of an in-group was described as being either highly prototypical of that group or as being non-prototypical. Specifically, participants were presented with one of two scenarios in which their team leader was described as being either (1) representative of the team’s norms and as having attitudes and interests that were in line with these norms or (2) as being an “outsider” who had interests and attitudes that deviated from team norms. Having read these descriptions, the participants were asked to indicate how much they trusted the leader. The results were very straightforward: those leaders who were in-group prototypical were perceived to be much more trustworthy than those who were non-prototypical.

In a later phase of this study participants were given information about the goals that the team leader was required to achieve and also told whether or not the team had been successful in reaching them. What was interesting here was that when the group failed to achieve its goals, those participants who had been told the leader was prototypical of the group were far more forgiving of the leader’s failure than those who were told that the leader was non-prototypical. Statistical analysis also confirmed that this willingness to forgive failure was a consequence of the greater trust that participants placed in the in-group-prototypical leader. Trust thus appears to be absolutely central to the leadership process, but answers to questions about who it is that we are prepared to trust seem to be firmly grounded in issues of shared social identity.

Fairness

For many commentators, fairness is a key characteristic of leaders. From James Rees and Stephen Spignesi’s (2007) study of George Washington to Richard Marcinko’s (1998) analysis of commando leaders, the message is that all followers must be treated alike—although the vigilant reader may recall from Chapter 1 that commando egalitarianism amounts to treating everyone “just like shit” (Marcinko, 1998, p. 13). For Rees and Spignesi a key lesson to be gleaned from George Washington’s effectiveness as a leader is that:

[He] did not want personal relationships to unduly influence the decision-making process, and he wanted to avoid the appearance of playing favorites … to maintain his reputation for utmost fairness.

(Rees & Spignesi, 2007, pp. 45–46)

In line with this sentiment, there is plenty of evidence that people often prefer leaders who are fair to those who are unfair. Indeed, the application of judicious decision-making is seen by many as the fundamental hallmark of leadership. We will examine this issue much more closely in the next chapter and discover that there are some important exceptions to this rule. Nevertheless, at this point it is pertinent to ask once more whether perceived fairness is a stereotypic leader characteristic that is associated with a leader’s in-group prototypicality and, more specifically, whether it is a consequence of that prototypicality.

One recent study that starts to answer these questions was conducted by a Finnish group led by Jukka Lipponen (Lipponen, Koivisto, & Olkkonen, 2005). These researchers measured the attitudes of workers in two Finnish banking organizations—asking them to think about their immediate supervisor, and then to indicate how prototypical that person was of their work group by responding to a range of statements (e.g., “Overall, I would say that my supervisor represents what is characteristic about my work group members”; after Platow & van Knippenberg, 2001). The researchers also asked the workers to rate the supervisor’s fairness by responding to statements such as “my supervisor is able to suppress personal biases.” As expected, the more these workers saw their supervisor as in-group prototypical, the fairer they perceived him or her to be.

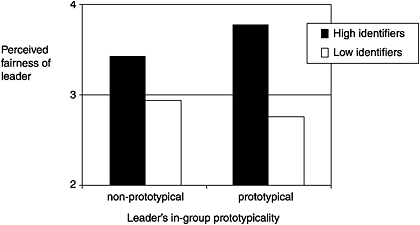

More recently, Eric van Dijke and David de Cremer (2008) surveyed over 250 Dutch civil servants, asking them three sets of questions. First, the respondents rated their team leader’s in-group prototypicality, using questions that were similar to those in the Finnish study described above. The researchers also measured the perceived fairness of these team leaders by asking a series of further questions. Did the leader apply rules consistently? Did the leader allow workers to have a say in important decisions? As in the work of Lipponen and colleagues, van Dijke and de Cremer observed a reliable positive relationship between these two sets of responses, such that leaders who were more in-group prototypical were also seen as more fair. Importantly, however, van Dijke and de Cremer went one step further and also measured respondents’ social identification with their work organization (i.e., organizational identification; see Haslam, 2001; Van Dick, 2004). As in several other studies that we have already discussed, the civil servants’ level of organizational identification proved to be an important qualifier of the relationship between leader in-group prototypicality and perceived leader fairness. Indeed, when these workers had low levels of identification with their organization—that is, when this particular group membership was relatively unimportant to them—there was no relationship between leader in-group prototypicality and leader fairness. Leaders were thus seen as more fair to the extent that they were more in-group prototypical, but this was true only if membership of the civil service was an important part of a respondent’s self-concept.

These Finnish and Dutch studies both support the hypothesis that there will be a positive relationship between leaders’ in-group prototypicality and their perceived fairness. The more a leader is seen to represent a valued in-group, the fairer he or she is seen to be. Again, however, these studies are only correlational and so it is impossible to establish whether prototypicality leads to perceived fairness, or whether fairness leads to perceived prototypicality (or whether both are the product of some other factor).

To help clarify this issue, van Dijke and de Cremer (2008) conducted a laboratory study in which the key theoretical variables (in-group prototypicality and organizational identification) were manipulated, not just measured. This involved recruiting Dutch university students to participate in a computer-based study in which they were asked to imagine themselves working for a specific (but hypothetical) company. Some of the participants were told to imagine that they fitted in well with this organization, that they were very involved in the work they had to do, and felt “at home” with their team. Other participants were told the opposite (i.e., that they did not fit in well, were not involved with their work, and did not feel at home). By this means, participants were induced to think about themselves as having either high identification with the organization (i.e., so that they were “high identifiers”) or low identification (“low identifiers”). After this, the participants then read some information about the behavior of their supposed team leader. This information indicated either that this leader was prototypical of their work group or that he was non-prototypical. Specifically, the information given to participants was as follows (square brackets indicate the wording used when the leader was non-prototypical):

Your team leader is [not] very representative for the kind of people in your team. As a person, he is [not] very much like the other team members. His background, his interests, and his general attitude towards life are very much like [different from] those of the other team members. He feels very much [does not feel] at home in your team.

(van Dijke & de Cremer, 2008, p. 239)

After having read all this information, participants were asked to indicate how fair they thought their leader was.

The key question in this study, then, was whether the leader’s in-group prototypicality and participants’ identification with the organization would have any impact on the perceived fairness of the leader’s behavior. The important feature of the study’s design was that in fact this behavior was identical in all experimental situations. Nevertheless, the results revealed significant differences in the leader’s perceived fairness in different situations, and the pattern of this variation was very similar to that which was observed in van Dijke and de Cremer’s earlier survey study. Thus, as can be seen in Figure 4.4, for low identifiers the leader’s in-group prototypicality had no substantive bearing on perceptions of his fairness. However, among high identifiers,

Figure 4.4 Perceived leader fairness as a function of (a) that leader’s in-group prototypicality and (b) perceivers’ social identification (data from van Dijke & de Cremer, 2008).

Note: Perceivers who identify highly with their group perceive the leader to be fairer when he is prototypical rather than non-prototypical of their in-group. However, this is not true for those who do not identify with the in-group.

leaders who were in-group prototypical were seen to be significantly fairer than leaders who were non-prototypical.

As with trust, what this research shows is that leaders’ fairness matters very much to those who follow them. Again, however, perceptions of this characteristic seem to flow from a person’s leadership rather than into it. More specifically, we see that whether or not leaders are seen to be fair depends, at least in part, on whether or not they are seen to be “one of us”—at least by people for whom “us” is important. On this basis it seems highly likely that when Americans like Rees and Spignesi (2007) make claims about George Washington’s fairness they are not simply describing a raw property of the man himself. Instead, this description should be seen as one that is colored by the biographers’ knowledge that Washington was one of the founding fathers of a nation that they both hold dear.

Charisma

Trust and fairness may be important for leadership, but there is one characteristic that often seems to be even more essential: charisma. Some claim that a leader who has it is assured of success; that a leader who lacks it is doomed. Thus, as the American conceptual artist Jenny Holzer put it in her 1977 work, Truisms, “lack of charisma can be fatal.” So, to continue in the vein of the previous two discussions, it is instructive to ask whether this too is associated with, and might be a product of, a person’s in-group prototypicality.

Two recent studies conducted by two of the authors in collaboration with colleagues in the Netherlands and Britain again provide clearcut answers to this question (Platow, van Knippenberg, Haslam, van Knippenberg, & Spears, 2006). Both involved measuring the perceived charisma of a leader who varied in his relative in-group prototypicality.

In the first study, Australian university students were shown a graph that was said to represent the distribution of qualities that characterized students from their university. The information did not indicate what these qualities actually were; instead, it simply said that this distribution was derived from a test to “measure similarities and differences between students who attend University [X] (like yourself) and students who attend other universities.” For all participants, an asterisk was also placed on this graph. This represented the position occupied by a student leader, “Chris.” Chris’s prototypicality for the student in-group was then manipulated by varying the position of this asterisk across three experimental conditions. High prototypicality was indicated by the fact that Chris was shown as being at the center of the distribution (indicating that he had a lot in common with other students); low prototypicality was indicated by the fact that he was located at either the left-hand or right-hand extreme of the distribution (indicating that he did not have a lot in common with other students).

Participants then read a letter that had supposedly been written by Chris in which he outlined his plans to place permanent billboard sites around campus at a cost of around $3,000. After they had read this, the students then rated Chris’s charisma on a series of scales. For example, they were asked whether Chris “inspires loyalty,” “has a sense of mission which he transmits to others,” “makes people feel proud to be associated with him,” and has “a vision that spurs people on” (along the lines of the MLQ that we discussed in Chapter 2; Bass & Avolio, 1997). The results were clear. When Chris’s position on the distribution indicated that he was in-group prototypical, he was seen to be much more charismatic than when he was non-prototypical.

Remember too that participants in this study did not even know what the actual characteristics were that made Chris more or less in-group prototypical: all they knew was whether these were, in fact, prototypical in-group characteristics. In other words, in order to be seen as charismatic (or not), it didn’t matter what particular qualities Chris possessed, it mattered only that they were qualities that epitomized us.

Of course, one might object to this conclusion by suggesting that group members only fall back on information about a leader’s in-group prototypicality when they don’t have any more specific information to go on. To address this issue, we conducted a second study in which the qualities that the leader was said to possess were explicitly identified. The first phase of this study involved surveying students to find out what they thought the typical qualities of students at their own university were as well as those that characterized students attending a rival institution in the same city. This revealed that students in the in-group were thought to be “friendly,”“easy going,” and “tolerant,” while those in the out-group (the other university) were seen as “high achieving,” “intellectual,” and “serious.”

In the study’s second phase the researchers presented students with information that described a leader of their student executive (“Chris”) as either (1) high on in-group characteristics and low on out-group characteristics (i.e., so that he was in-group prototypical) or (2) low on in-group characteristics and high on out-group characteristics (i.e., so that he was in-group non-prototypical). In addition, participants read a short letter from this leader. In this he talked about his leadership either by emphasizing the group as a whole (e.g., “Let’s do something together … for all of us”) or talked about his leadership in terms of interpersonal exchange (e.g., “Do something for me, so I can do something for you”). In other words, the former message was transformational, but the latter was transactional.

After reading this message the participants then rated the leader, Chris, on the same scales as in the previous study. So were these ratings in any way affected by his in-group prototypicality and his rhetorical style? Yes they were. Replicating the main finding from the previous study, when Chris was in-group prototypical, ratings of his charisma were relatively high, regardless of his rhetorical style. However, when he was in-group non-prototypical, ratings of his charisma were also relatively high if his rhetoric was transformational and emphasized the collective (“us”). In contrast, when Chris was non-prototypical and couched his message in transactional terms, he was perceived to be particularly uncharismatic.

Notice too, that in this second study the characteristics that were seen to be typical of the out-group were actually more stereotypical of leaders in general than those that were characteristic of the in-group. Here, leadership categorization theory might lead us to believe that group members should generally prefer a leader who is intellectual and high-achieving to one who is tolerant and easy-going (e.g., Lord & Maher, 1990). Nevertheless, as we have seen several times already, regardless of how attractive they are in the abstract, when particular characteristics exemplify “them” rather than “us,” they tend to be far less prized in our leaders. And this is particularly true if those leaders appear to show no interest in “us,” and choose to frame their leadership in transactional rather than transformational terms.

On this basis, we can conclude that charisma does indeed appear to be a “special gift” of leaders as suggested by Weber (1922/1947; see Chapter 2). However, this is not a gift that they possess, and it is certainly not a characteristic of their personality. Rather, as Platow and colleagues suggest in the title of the paper in which the above two studies were reported, it is a gift that followers bestow on leaders for being representative of “us.” This is a gift that leaders have to earn by representing us, not one they are born with and can take for granted.

Prototypicality and the creativity of leaders

We promised, at the start of this chapter, to return at the end to the question of creativity. This is an important issue since leaders who are limited to working in an existing rut will clearly be limited in their ability to guide group members through an uncertain and ever-changing world. Any model that suggests that leaders can only ever reproduce the status quo must therefore be an inadequate model of leadership. For this reason it is important to stress that we regard prototypicality not as something that limits leaders, but as something that enables them to work creatively with and for group members.

Some evidence of this creativity can be found in the studies that we have just described. If we reflect again on the results of the second of Platow and colleagues’ (2006) charisma studies, it is interesting to note that group members appear not only to have viewed the leader who was in-group prototypical as more charismatic, but also to have given him greater latitude in his behavior than the leader who was non-prototypical. That is, as long as he was relatively in-group prototypical, Chris was seen as charismatic and it did not matter whether he had used a transformational or transactional communication style. This points to some of the advantages that can accrue to leaders by virtue of their in-group prototypicality. For once a leader is thought by fellow group members to embody the essence of “us” relative to “them” in a particular context, it suggests that he or she may actually have the ability to diverge from existing definitions of what is normative, and thereby take (or, more aptly, lead) the group in new directions. This is important because, as we saw in earlier chapters, leaders’ capacity to rally followers behind their creative initiatives is recognized as a central feature of the leadership process (Cartwright & Zander, 1960). The question of how exactly this is achieved is thus a central one—for both theoretical and practical reasons.

As we discussed in Chapter 2, the answer previously proposed by Edwin Hollander (e.g., 1964) is that leaders need to build up a line of “idiosyncrasy credit” by first proving that they conform to group norms before being given license to depart from those norms. In contrast to Hollander’s analysis, however, the social identity perspective suggests that the underlying process here is not one of interpersonal exchange but rather one that centers on a higher-order sense of group identity that leaders and followers are perceived to share. In these terms, idiosyncrasy credit is fundamentally grounded in group members’ categorization of the leader as someone who is “one of us” and who is also prototypical of us. Among other things, this helps explain how leaders are able to gain support for novel projects outside the small group contexts in which idiosyncrasy credit is typically studied and in which interpersonal exchange is not possible. The capacity for a leader to acquire credit by championing and representing novel social identities (as we noted previously in the case of Nelson Mandela’s vision of post-Apartheid South Africa) also explains why individuals who represent minorities and radical groups can bring about change even under conditions where they have no established credit with the majority. Indeed, their capacity to do this points to a key problem that Serge Moscovici (1976) identified with Hollander’s original theorizing, which he faulted for placing too much emphasis on the way that influence reflects established relations of authority—thereby underplaying the potential for leadership to drive social and organizational change.