5

Doing it for us

Leaders as in-group champions

Of myself I must say this, I never was any greedy scraping grasper … nor yet a waster, my heart was never set on worldly goods, but only for my subjects’ good. What you do bestow on me I will not hoard up, but receive it to bestow on you again; yea mine own properties I account yours to be expended for your good, and your eyes shall see the bestowing of it for your welfare.… For it is not my desire to live nor reign longer than my life shall be for your good. And though you have had and may have many mightier and wiser princes sitting in this seat, yet never had nor shall have any that will love you better.

(Queen Elizabeth I, The “Golden Speech” to Parliament, November 1601; see MacArthur, 1996, pp. 42–43)

If I have to apply five turns to the screw each day for the happiness of Argentina, I will do it.

(Eva Peron; see Montgomery, 1979, p. 207, used with permission)

In the previous chapter we focused on what leaders have to be—or at least what they have to be seen to be—in order to be effective. But, of course, leadership is not just about being. It is also about doing. In this chapter we therefore ask the question, what do leaders have to do in order to be accepted by followers and be in a position to influence them? To put it slightly differently, how do leaders have to act in order to engage the energy and enthusiasm of the whole group and to ensure that their individual visions and projects are transformed into collective visions and projects?

The traditional answer to this question is to furnish a general list of behaviors that are required of the successful leader. This is the sort of approach that we encountered in Chapter 1, whereby what you are advised to do is learn the secrets of a great leader and then emulate them yourself. The idea here is that if you are a good learner you will be equally successful (although if your role model is Attila the Hun or Genghis Khan it isn’t clear how much this is to be recommended).

Our answer to this question suggests that the types of behavior that generate influence are those that advance—or at least are seen to advance—the particular interests of the group in question. These can never be specified independently of the group that is to be led. And here leaders must not only stand for the group, they must also stand up for it. They must not only be in-group prototypes; they must also be in-group champions.

The logic, then, is similar to that which underpinned our discussion of prototypicality in the previous chapter. While we can specify, at a general level, the processes that underlie effective leadership, the actual forms that leadership has to assume in order to succeed will always depend on the specific nature of the groups in question. To be more concrete, it is one thing to say that leaders must be prototypical, but what actually constitutes prototypicality will, as we have seen, vary from group to group and from context to context. In exactly the same way, it is one thing to say that leaders have to advance group interests, but how groups define their interests and what forms of leadership behavior they see as advancing those interests will, as we will now see, vary from group to group and from context to context.

In seeking to develop this argument, a large part of our analysis will focus on one particular form of leadership behavior: fairness. This is because, perhaps more than anything else, fairness (or what Fleishman and colleagues’ Ohio State studies referred to as “consideration”; see Chapter 2) is commonly identified as the defining characteristic of successful leadership and for this reason it has been the focus of a great deal of research attention. Indeed fairness has been widely seen as something that has the capacity to bridge the gap between leadership and followership. This claim is typified in an observation by the American engineer, George Washington Goethals:

[In your dealings with] those who are under your guidance … you must have not only accurate knowledge of their capabilities but a just appreciation and full recognition of their needs and rights as fellow men. In other words, be considerate, just and fair with them in all dealings, treating them as fellow members of the great Brotherhood of Humanity. A discontented force is seldom loyal, and if discontent is based upon a sense of unjust treatment, it is never efficient. Faith in the ability of a leader is of slight service unless it be united with faith in his justice. When these two are combined, then and only then is developed that irresistible and irrepressible spirit of enthusiasm, that personal interest and pride in the task, which inspires every member of the force, be it military or civil, to give when need arises the last ounce of his strength and the last drop of his blood to the winning of a victory in the honor of which he will share.

(G. W. Goethals; cited in Bishop, 1930, p. 450)

We have no quarrel with Goethals to the extent that he is arguing that a leader’s fairness can unite us by both creating and clarifying shared group memberships, and, in this way, that it can become a basis for influence and inspirational leadership.1 We fully accept that it is important that leaders treat us fairly. In line with the conclusion of the Nobel Prize-winning economist George Akerlof and his co-author Robert Shiller in their book Animal Spirits (2009), we agree that a concern for fairness is one of the fundamental motivators of social and economic behavior. We also agree that unfair treatment at the hands of our leaders drives a sword between them and us, establishing different groups, and thereby destroying the psychological architecture necessary for influence and leadership.

However, this is very different from saying that all leaders of all groups have to be fair at all times and in all ways. Indeed, the idea that leaders must advance group interests—that they must be “doing it for us”—suggests that they might often succeed by being unfair. In line with this point, we will see that the meaning of fairness is open to negotiation. We will see that there are times when a leader’s apparent unfairness (especially towards out-groups or deviant in-group members) can engender support, group maintenance, and influence. But we will also see that, whether group members endorse a leader who favors them over outsiders is itself a function of group norms.

It is therefore important to understand when, and in what groups, leaders need to be either fair or unfair in order to win the endorsement of their followers. This is important for us as theorists, but it is also important for leaders themselves. For it is only if leaders get these things right that they will be able to harness the energies of their followers.

The importance of fairness

Fairness and leadership endorsement

Group members expect their leaders to be fair. In the words of Robert Lord and colleagues, whose work we discussed at length in Chapters 2 and 4, fairness “fits peoples’ views of what a leader should be” (Lord et al., 1984, p. 351). These researchers arrived at this conclusion after providing people with a long list of supposedly leader-like and non-leader-like behaviors and asking them to rate these behaviors in terms of their fit with the image of what a leader should be. As we saw earlier, many behaviors fit this image. Importantly, though, fairness was very prominent among them.

This research led Robert Kenny and a team of co-researchers to seek to clarify further group members’ “implicit” views about what leaders should be and do. They did this by asking people to sort large numbers of leadership qualities (e.g., “being charismatic,” “giving ideas to the group,” “exhibiting confidence”) into different categories based on their perceived similarities and differences. The results suggested that fairness underlies people’s views of a wide range of leadership characteristics associated with both “new leaders” (Kenny, Blascovich, & Shaver, 1994) and “democratic leaders” (Kenny, Schwartz-Kenny, & Blascovich, 1996). Indeed, “being fair” ended up in more categories than any other characteristic, leading the researchers to conclude that “being fair lies at the heart of the many behaviors that help a new leader achieve acceptance by the group” (Kenny et al., 1994, p. 419).

This provides a first lesson in the fairness–leadership relationship. Simply put, group members expect fairness to underpin their leaders’ behaviors. At least, that is what people say. But as we know, what people say they want and how they respond when they get it are not always the same thing. So how do people respond to leaders who are more or less fair?

In order to address this issue, two Dutch researchers, Arjaan Wit and Henk Wilke (1988) conducted controlled experiments designed to examine how group members respond to a leader’s fairness and unfairness under conditions of shared but scarce resources. In these situations, it is in everyone’s immediate and personal self-interest to use the resource as much as they can. However, if everyone pursues this strategy, a problem arises because the resource becomes depleted. In this way, individual rationality leads to collective disaster. First identified by the British economist William Forster Lloyd in the early 19th century, this is referred to as the “commons dilemma,” in reference to the destruction of common land that occurs if everyone allows their livestock to graze on it unchecked (Lloyd, 1833/1977). Many situations in contemporary daily life have the same dilemmatic structure: access to public television (personal self-interest says to watch without contributing financially), fishing in open waters (self-interest says to fish as much as possible), voting (self-interest says to stay at home and not bother), citizenship behaviors in the workplace (self-interest says to avoid doing more than is formally required because you’re not getting paid for it), and even claiming picnic ground in a busy public park (self-interest says to arrive as early as possible and stake out the largest possible area). In each case, at the level of the collective, people’s pursuit of their personal self-interests can result in ruin. This, then, seems a situation tailor-made for leadership—but how do people respond to the introduction of a leader and how are they affected by the leader’s behavior?

In Wit and Wilke’s laboratory study, people participated in a computer simulation that involved harvesting a resource, with real money being given to those who harvested the most. A series of harvesting opportunities were then provided, with the resource replenishing slightly after each harvest (as you might expect when, say, more fish are spawned at the same time that they are being fished). However, the experimenters made sure that their participants discovered that, in the end, the resource diminished completely (thereby eliminating further opportunities for more harvests and, hence, for more money). Once the resource was completely exhausted, participants were told that there would be a second harvest simulation and they were asked to vote on whether they wanted a leader to manage the resource. Three quarters of them did.

As the second simulation unfolded, the research participants were told that the leader had been either fair or unfair through over- or underpayment to him- or herself, over- or underpayment to the actual participants, and over- or underpayment to another third person who had access to the resource. The study’s findings were straightforward. Leaders who were fair across the board received the strongest subsequent endorsements, whereas leaders who overpaid themselves and underpaid the participants received the weakest endorsements.

Two points emerge from this study, which relate to different ways in which the term “fairness” can be understood. The first concerns the way in which leaders reward themselves compared with their followers: it is important that they don’t treat themselves better than other group members. This confirms our previous claim that anything that distinguishes leaders from followers and that suggests that they are removed from the group is liable to limit and compromise their leadership. This was a point we made at the beginning of the previous chapter and, accordingly, we will not pursue it further here.

The second point, by contrast, is new. It concerns fairness in the way that leaders treat different members—or different sub-sections—of the in-group. Here it is important that they don’t treat some members (or sub-groups) better than others. If they do, their standing as a leader will diminish. In the studies by Wit and Wilke, this sense of fairness has to do with how much of a given resource (in this case resources worth money) leaders give to different members (which is generally referred to as “distributive justice”). But it can also relate to the fair application of the rules that are used to decide how much different people get (referred to as “procedural justice”).

The importance of leaders’ fairness rules is illustrated by a substantial survey study conducted by Tom Tyler and his colleagues in the United States. This investigated American university students’ support for various national political leaders, including US Presidents. In line with our discussion of Rees and Spignesi’s (2007) approval for George Washington (see Chapter 4), these researchers found that endorsement of these leaders was predicted by how procedurally fair the respondents believed the leaders to be when they went about their jobs. Interestingly, this finding also held firm when the researchers controlled for how much the respondents thought they personally benefited from a particular leadership regime (Tyler, Rasinski, & McGraw, 1985). The same basic finding has also been replicated in studies of people’s experiences with their work supervisors (Tyler, 1994) and of Americans’ reactions to the presidency of Bill Clinton (Kershaw & Alexander, 2003). In both studies, the results were again very clear. The more procedurally fair the participants saw the leader’s behavior as being, the more support there was for that person’s leadership.

Fairness and group maintenance

Group members’ views of a leader’s fairness do more than provide that leader with support. Perceptions of leader fairness actually help to hold the group together. In the terminology of Cartwright and Zander (1960), they are a basis for group maintenance and, as we noted in the previous chapter, this is a key feature of most leadership roles. Of course, there are times when group members may applaud the collapse of the group, and celebrate as heroes those who orchestrate that collapse. But such instances are likely to occur when the group has become stagnant, is failing to achieve its goals, or when its leadership is perceived to have been fundamentally unfair. For example, such features can be seen to have been in place under Mikhail Gorbachev’s stewardship of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Indeed, it was because the Soviet regime was seen as unfair that the demise of its leadership was sought and that those, like Gorbachev, who brought this about were fêted.

More often than not, though, the maintenance of a group’s integrity is seen to be very important by its members as well as by other observers and commentators. Indeed, as we noted in the previous chapter, Cartwright and Zander (1960) argued that group maintenance is one of the two primary functions of leadership, the other being goal achievement. They also observed that this maintenance can be achieved through a variety of processes, including: (1) the maintenance of positive intragroup relations and (2) the assurance that all group members and sub-groups (e.g., minorities) are treated in an impartial manner.

Empirical support for these ideas can be found in the work of Manfred Schmitt and Martin Dörfel (1999). They surveyed nearly 300 workers in a large German automobile company. Employees’ perceptions of managers’ fairness was measured, as well as the number of days that these employees failed to show up for work due to illness. As expected, the greater the perceived unfairness, the more days the workers took off sick.

In another test of the effects of authorities’ fairness within the workplace, Joel Brockner and colleagues surveyed nearly 600 employees of a nationwide retail store in the United States (Brockner, Wiesenfeld, Reed, Grover, & Martin, 1993). The store had just completed a round of lay-offs, so it was possible to ask employees (the survivors of this “purge”) very specific and meaningful questions about their employers’ fairness. The employees also indicated their overall commitment to the organization, and responded to the very direct statement, “I have every intention of continuing to work for this organization—rather than a different organization—for the foreseeable future.” Herein lay the critical test relating to group maintenance. Would the employees want to stay? When controlling for workers’ perceived quality of their jobs as well as their prior attachment to the organization, perceived fairness led directly to enhanced organizational commitment. In terms of intentions to leave, prior attachment to the organization also became important. To the extent that workers had some pre-existing attachment to the organization, they had greater intentions of leaving if they perceived the authorities’ behavior during the lay-off period to have been unfair.

So, leadership that is fair helps maintain groups by keeping their members on board. It also maintains groups by facilitating constructive interactions between existing members. The evidence for this comes, once again, from the work of Tom Tyler. In 1995, Tyler and his colleague Peter Degoey surveyed 400 people living in San Francisco during a time of severe water shortages in California. This water-shortage situation is another classic example of a commons dilemma. This is for the simple reason that if everyone pursued their short-term personal self-interest by using as much water as they liked, collective disaster would result because there would be no water left for anyone. This, of course, has strong implications for the ultimate survival— that is to say, the maintenance—of the entire community. Indeed, for precisely this reason a government authority was established in California to regulate residents’ water usage.

Respondents in Tyler and Degoey’s study were asked to indicate the extent to which they viewed the water-use authority’s actions to be fair (in both distributive and procedural terms), as well as their support for, trust in, and likely acceptance of the decisions of the authority. As expected, all of these leadership outcomes were positively related to the perceived fairness of the authority. The more that San Franciscans viewed the authority to be fair, the more they supported it, trusted it, and the more likely they were to accept its decisions. This last feature of decision acceptance is crucial for our current discussion because in this very real setting, accepting or not accepting the decisions of the authority had direct implications for the maintenance or ultimate collapse of the entire community. This is apparent from residents’ responses to direct questions about whether or not they would voluntarily restrict their water usage if the authority asked, and how much they would actually conserve willingly. Here the more fair the residents perceived the authority to be, the more willing they were to forgo their own short-term individual gains for the benefit of the community as a whole. In short, if community leaders were seen as fair, the subsequent behavior of community members was much more likely to ensure, rather than compromise, the community’s survival.

In recent years, Tyler and colleagues have sought to flesh out the processes whereby the fairness of leaders generates behaviors that ensure the cohesion and survival of groups. Their work points to the importance of one critical mediating factor: respect. This is already apparent in the study we have just been describing. Here one of the questions that Tyler and Degoey asked the residents of San Francisco was how much they felt respected by fellow community members. Specifically, the survey included questions of the form “If they knew me well, the people in my community would respect my values.” Questions such as these are particularly interesting because they appear to be completely divorced from the authorities themselves and from the domain in which their leadership operates. Nonetheless, the more that the authorities were perceived to be fair, the more people felt that they were viewed with respect in their community. Moreover, this was enhanced if the residents had relatively strong identification with their community in the first place.

In subsequent studies, Tyler and his group made two further observations. First, that enhanced respect leads to enhanced collective self-esteem (i.e., how positively people see themselves as group members; Smith & Tyler, 1997). Second, that enhanced respect is associated with increased rule compliance, increased citizenship behavior (i.e., putting oneself out for fellow group members), and increased commitment to the group. In sum, increased respect leads to an increase in various forms of contribution that are essential to group maintenance. Putting all these findings together, it appears that the perceived fairness of leaders promotes an increased sense of being respected by fellow group members, which in turn promotes increased contributions to the group. Tyler and Blader (2000, 2003) refer to this pattern of relationships as the group engagement model (see Figure 5.1).

In order to provide a complete test of their model, Tyler and Blader (2000) conducted an extensive investigation of the attitudes and reported behaviors of over 400 working people in the United States, whose annual incomes ranged from less than $10,000 per year to over $90,000 per year. The study focused on people’s reactions to authorities in the workplace— typically their supervisors. Here, in a single study, the authors were able to show that perceptions that an authority’s procedures were fair did in fact lead to higher levels of perceived respect within the organization, and that this subsequently led to more favorable attitudes toward the organization, as well as greater “in-role” (mandatory) and “extra-role” (voluntary, citizenship) behavior. Simply put, by enhancing respect, leaders’ use of fair procedures encouraged group members to think and behave in ways that held the group together. Within the group, a leader’s fairness is a powerful bonding agent.

Cracks in the wall: Unfairness in the definition of fairness

Thus far, the evidence that we have presented seems to tell a pretty consistent story. At least when it comes to the treatment of people within a group, people seem to expect fairness, they seem to reward leaders who display fairness, and they seem to commit themselves to groups that are governed by fairness. This is true whether it is a matter of fairness between leaders and

Figure 5.1 The group engagement model (after Tyler & Blader, 2000).

Note: The model explains group members’ willingness to engage in behavior that is beneficial to the group in terms of their perceptions of the fairness of leaders and the sense of respect that this fairness communicates.

followers or else of fairness in the way that leaders treat different followers. It is true whether one is referring to what one gives to people (distributive justice) or to the application of rules determining what outcomes people should receive (procedural justice).

However, this very breadth of support points to the fact that “fairness” can be understood in many different ways and along many different dimensions. Fair’s fair, right? Well, not entirely. People might know about different types of justice rules (Lupfer, Weeks, Doan, & Houston, 2000). But they don’t always agree on how they should be applied.

To see this point more clearly, consider a study that was conducted with American university students by David Messick and Keith Sentis (1979). In this the students were asked to imagine that they and another student had done some work for one of their professors. Some students were asked to imagine that they had worked more hours than the other student, others that they had worked an equal number of hours, others that they had worked fewer hours. The students were then told that the professor had $50 to split between them and the other student in order to pay them for their efforts. They were then asked three questions to indicate: (1) how they (the students) would distribute the $50 in order to be most fair; (2) how they would most like to distribute the $50; and (3) how, if they had to make a distribution, they would actually distribute the $50.

Unsurprisingly, when asked which distributions they would like most, students always preferred to give more money to themselves than to the other student. But when it came to judgments of fairness, the students showed evidence of two fairness rules. The first was an equity rule and involved paying more to the person who worked more. The second was an equality rule and involved making a completely equal distribution (especially when both had worked the same amount). However, when choosing which rule to apply, the students thought it would be fair to overpay themselves slightly when they worked more than the other relative to what they thought would be fair when the other person worked more than them. A similar pattern occurred with students’ intended distributions.

What is most interesting about these findings is the clear evidence they provide of shared norms (rules) about fairness. Clearly, though, the students seemed to invoke these rules in ways that best suited their own self-interest. When they worked more than the other person, they distributed the money proportionally (respecting the equity rule). But when the other person worked more than them, students’ distributions moved in the direction of equality. In essence, students were always being fair (with the exception of the blatant self-interest in their liking for overpayment to self), but they were picking and choosing the fairness rules that most satisfied their personal self-interest. Such findings bring into focus the potential for debate about what is fair and when. People will follow fairness rules, but they customarily do so in a self-interested manner. Despite this, when a sample of American (Messick, Bloom, Boldizar, & Samuelson, 1985) and Dutch (Liebrand, Messick, & Wolters, 1986) university students were asked to list the fair and unfair behaviors that they personally displayed and that other people displayed, these respondents routinely listed more fair and fewer unfair behaviors of their own relative to those of others. In other words, far from being sensitive to their selective application of fairness rules, people tend to see themselves as paragons of fairness, at least in comparison to others.

Clearly, then, there is variation in the application of fairness principles—and in the understanding of what constitutes fairness—within a group. However, as we will see in the next section, this point becomes even clearer when we consider the application of fairness principles between groups.

From fairness to group interest

The boundaries of fairness

Social psychologists and moral philosophers acknowledge that there are boundaries to fairness. Fairness is assumed to apply primarily—if not solely— within a specific moral community. In some contexts, this is so taken for granted that we can almost overlook it. For instance, Goodhart (2006) points out that Britain, in common with all other nations, spends far more on the health of its own citizens than on citizens of other countries. As a result, the budget for the National Health Service is 25 times the development aid budget despite there being considerably greater need in developing countries.2

Not only is it the case, however, that we are less willing to give positive outcomes to out-groups than to our in-group. We are also more willing to give them negative outcomes—at times, extremely negative ones. Consider the case of the United States soldier, Sergeant Hasan Akbar.3 In March 2003, Sergeant Akbar tossed a grenade at fellow United States soldiers in the early days of the invasion of Iraq. After this, he was apprehended, tried, found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. This is an interesting sequence of events, given that he was supplied with the grenade by the United States government, and given the specific assignment to kill people. Indeed, had Sergeant Akbar tossed the grenade in the other direction, killing those identified as the enemy, he may well have been hailed as a hero. Clearly there are social groups within which moral principles, including fairness, are expected, if not legislated. However, outside the boundaries of these groups or moral communities, the rules are eased, exceptions are made, and explanations and rationalizations are provided in order to minimize any sense of moral violation. Here people often prove willing to do whatever it takes to avoid being fair or being seen to be fair. Indeed, this is the basis of the proverbial observation that “all’s fair in love and war.”

If this wartime example appears too extreme, consider two other contexts in which people are actually paid to be fair. At the University of South Australia in Adelaide, Philip Mohr and Kerry Larsen (1998) analyzed the umpiring decisions in over 170 Australian Rules football matches that were played between teams from different Australian states over a four-year period. Needless to say, the umpires who adjudicate the games are supposed to do so from a position of impartiality and fairness; their very purpose is to ensure “fair play.” Yet when the researchers identified the home state of the umpires, they found that the awarding of free kicks (penalties that give an advantage to one team) was distinctly unfair. And guess what—it reliably favored the teams from the umpire’s home state. Moreover, this pattern of in-group favoritism was particularly pronounced when the match was being played in the umpire’s home state. Clearly the requirement for umpires to be impartial and fair was being flouted in these intergroup contexts, and this was especially true when umpires were under the watchful eye of their in-group.

More telling still is an analysis of the decisions of the International Court of Justice that was performed by two researchers from the United States, Eric Posner and Miguel de Figueiredo (2005). This court is the primary judicial body of the United Nations and in many ways it represents the ultimate world body for meting out justice and fairness. Accordingly, one might expect it to be the very apotheosis of fairness. Yet, when looking at the Court’s final decisions, Posner and de Figueiredo found that judges clearly favored the countries they represented, as well as those that were similar in wealth, political system, and culture. In short, like the football umpires, the judges did not seem to dispense justice even-handedly. Instead, they delivered more justice for “us” than for “them.”

If these studies still do not make a strong enough case, consider some classic laboratory studies conducted by John Turner (1975) many years earlier. In these, Turner created ad hoc, trivial categories that had no substantial meaning outside the laboratory. That is, they were so-called “minimal groups” of the form that we discussed in Chapter 3 (after Tajfel, 1970). Having placed participants in groups, Turner then asked them to distribute a set amount of money between themselves and another person in their own category (i.e., an in-group member), or between themselves and another person in the other category (an out-group member). As expected, participants’ monetary distributions were characterized by greater levels of fairness when they involved an in-group rather than an out-group member.

Far from being trivial, this final study is extremely important. As we noted above, the difference between killing one’s fellow soldiers and those of the opposing army may seem so obvious that it does not require formal analysis. However, this extreme case is no different from the minimal group studies in its fundamental exemplification of our initial premise that the application of fairness has contours and boundaries. Indeed, from the work we have discussed thus far it is apparent that these contours and boundaries manifest themselves and prove to be important in situations that are extreme (as in the case of war), trivial (as in the case of meaningless laboratory groups), and relatively common (as in the case of football matches and court cases). What we see too is that, in all cases, the application of fairness rules is structured by our shared group memberships. In each case there are boundaries within which fairness rules are seen to apply. Beyond these, we are reluctant to invoke the same rules. Fairness, then, is for our own moral community, for “people like us.” Outside this, the rules are likely to change—if they apply at all.

But while fairness rules exist and people recognize them, there remains debate both about which rules to employ and about what is and is not fair. Importantly, the existence of such debate does not imply individualistic relativism. It does not mean that fairness and justice are determined by every individual in isolation—so that, in the end, “anything goes.” Instead, debate about fairness involves communication and discussion, and normal processes of protest, persuasion, and influence between individuals and groups that hold different positions of power, wealth, status, and information. The intended outcome of this debate is some degree of consensus about how resources ought to be distributed and about how procedures ought to unfold. This debate is going on around us all the time and in their early elaboration of equity as one form of fairness, William and Elaine Walster (1975) noted that individuals and groups have a vested interest in contributing to this debate by putting forward their case. Walster and Walster also recognized, however, that it is typically more powerful groups who capture the lion’s share of the resources and have greater ability to make rules in the name of fairness that allow them to maintain their relatively powerful position and their command of resources. Again, it is not that fairness varies with each individual’s unique perspective, but rather that it is affected by the perspective of individuals as group members. This is an important point, for as we will see in the next section, fairness depends critically on one’s position within broader intergroup contexts. This means that people not only see themselves as being fairer than others (as noted above), but also that they see fellow in-group members as fairer than out-group members (Boldizar & Messick, 1988).

Group interest and leadership endorsement

It is one thing to argue that, while fairness amongst the in-group is the rule, so is unfairness to the out-group. It is quite another to demonstrate that we prefer leaders who are unfair to out-group members over those who are fair. Already, though, the examples we have provided give us some inkling that this might be the case. Thus Posner and de Figueirdo (2005) speculate about why it is that judges sitting on the International Court of Justice display partiality towards their home nation. Amongst many possible reasons, they suggest that voting against one’s own country—even if it represents the most appropriate application of fairness—may result in the judges’ failure to maintain support from their home country, and hence to secure reappointment. As they observe, “there is evidence that the nomination of judges is a highly political process” (p. 608). Likewise, the fact that football umpires display greater in-group favoritism when they are in front of an in-group audience suggests that they too are sensitive to the fact that their authority depends on the in-group’s approval of their decisions. In these most real of situations, it seems that people in positions of authority can (or at least feel they can) secure leadership positions precisely by being unfair to the out-group.

This suggestive evidence is buttressed by a series of experiments conducted by the third author and colleagues at the University of Otago in New Zealand. These set out to provide a systematic analysis of when people support fair leaders and when they support unfair leaders (Platow et al., 1997). Like Tajfel (1970) and Turner (1975), in their first study the researchers assigned university students to minimal groups that had no meaning outside the laboratory context. After a short problem-solving activity within their groups, the individual group members proceeded to perform a series of individual computer-based tasks. The students were told that some, but not all, research participants would need to complete extra tasks, and that a leader was needed to distribute these tasks amongst participants. In all cases, the research participants themselves were neither the leader nor the potential recipients of the additional tasks. In this way, personal self-interest was completely removed from the equation.

Unsurprisingly, when the two recipients of the extra tasks were both members of participants’ own in-group, leaders received strong support when they made fair (in this case, equal) distributions but they received little support if they made unfair (unequal) distributions. However, when the distributions were made between a fellow member of participants’ own in-group and a member of another group in a different laboratory (an out-group), patterns of leadership endorsement changed. In this intergroup context, the fair distribution represented equal treatment of the in-group and out-group member, and the unfair distribution favored the in-group member over the out-group member. What emerged here was that support for the fair leader dropped while support for the unfair leader rose so that there was no longer any reliable difference in endorsement of the two.

In a second study, Platow and colleagues (1997) provided another sample of New Zealand university students with a scenario that involved two people flying to the nation’s capital, Wellington. They were going to participate in a forum to discuss the impact of recent government policies on university education. Five-hundred dollars was said to be available to assist with travel costs. When the authority distributing the money gave $250 to each of two students (neither of whom were the participants themselves), participants provided strong endorsement for this authority to remain in his or her position. On the other hand, when the authority gave all $500 to one student and nothing to another, the level of endorsement substantially decreased. Again, then, these patterns suggest that, within our own group, we prefer leaders who are fair to those who are unfair. But the pattern changed when it came to allocations between groups—that is, when participants had to divide the available funds between a student and a government official (an outgroup member). In such conditions, unfair allocation (giving everything to the student and nothing to the official) led to increased endorsement of the allocating authority, while fair allocation (splitting the funds evenly between the two) led to decreased endorsement.

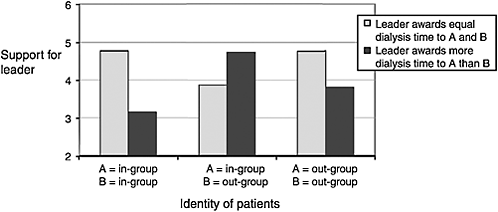

The researchers’ final study looked at intra- and intergroup allocations in the context of a more acute, more familiar, and more realistic dilemma. What happens when you have to allocate scarce time on a kidney dialysis machine amongst multiple patients? Participants, once again New Zealand University students, were presented with a memorandum, supposedly written by the (male) Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of a local Health Authority. The memorandum proposed procedures for dividing time between two equally needy patients. Participants were then asked their opinion about the CEO.

In this study, the pattern of findings was similar to that in the first two studies—although, if anything, the contrast between the consequences of intragroup and intergroup allocations was even clearer than before. Thus, when the patients were described as two life-long New Zealanders, the CEO received strong endorsement if he proposed an equal distribution of time, and he received much weaker endorsement if he proposed an unequal distribution of time. However, as can be seen from Figure 5.2, this pattern completely reversed when one of the patients was described as a life-long New Zealander and the other was described as a recent immigrant, and the inequality favored the life-long New Zealander. Now, in order to win support, the leader had to allocate more time to the in-group member than to the out-group member.

Four points are important to note about this final study. First, the researchers controlled for participants’ own expectations of personally needing such life-support systems. Second, the researchers also controlled for

Figure 5.2 Support for a hospital CEO as a function of his allocation of dialysis machine time and the identity of patients (data from Platow et al., 1997, Experiment 3).

Note: When the patients are both in-group members or both out-group members the CEO receives more support if he allocates time equally rather than unequally. However, when one patient is an in-group member and the other an out-group member the CEO receives more support if he gives more time to the in-group member than if he allocates time equally.

beliefs that the life-long New Zealander deserved more because he or she had contributed more to the country (e.g., in taxes). Third, the researchers included an additional situation in which the CEO was described as an Australian (an out-group member) and the distribution was between a lifelong Australian and an immigrant to Australia. In this purely out-group context, the typical fairness–leadership endorsement effect was found, with the fair CEO receiving stronger endorsement than the unfair CEO. This third situation is critical because it highlights the point that it is favoritism toward people’s own group, not just any group, that is important. It is only when fairness decisions relate to “us and them” that group members reward asymmetry in a leader’s displays of inequality with their own expressions of support for that leader.

Fourth and finally, it is worth pointing out that outcomes like those that were observed in this study are not unknown in medical practice. In the 1980s, research by Thomas Starzl and his colleagues reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association revealed that some hospitals in the United States were retaining high-quality human organs for donation to those patients who were residents of the state in which the hospital was located (Starzl et al., 1987). As a result, residents of other states tended to receive lower quality human organs. To dispassionate readers, this probably sounds unfair, if not outrageous. Yet it seems highly likely that the hospital decision makers instituted this practice because it was a form of unfairness that their constituents—the state’s taxpayers—were perceived to endorse. Indeed, it seems likely that the decision makers felt that this pattern of distribution was required in order for them to be supported in their position. In short, their leadership was perceived to be contingent not on displays of fairness, but on displays of in-group-favoring unfairness.

We have dwelt at some length on this series of studies because it provides a stark demonstration of the point that it is misleading to suggest that a specific form of action—fairness in this instance—is always required of a leader or will always buttress a leader’s position. Sometimes leaders must be fair, sometimes leaders must be unfair. But that is only half the story. For, as we have also seen, there is a systematic pattern to the circumstances under which these different behaviors are demanded. On the one hand, leaders must be fair within a group because to do otherwise would set member against member and (as we saw in the previous section) this could jeopardize the group’s very existence. In all these ways, unfairness militates against the group interest while, as a corollary, fairness promotes the group interest. On the other hand, though, leaders must be unfair between groups because they are expected to support their own group. In this context, fairness would fail to advance the group interest while, as a corollary, unfairness promotes this interest. Overall, our point should be obvious by now. The constant here lies not at the level of specific behavior but in the expectation that leaders should promote, and be seen to promote, the group interest in a way that appears appropriate to group members in the situation at hand (for further elaboration of this point, see Duck & Fielding, 2000, 2003; Jetten, Duck, Terry, & O’Brien, 2002).

In order to drive home this crucial point, let us depart temporarily from the issue of fairness, and, indeed, from the issue of what leaders need to do. For if the critical thing is whether leaders are seen to benefit the group, then, as long as such perceptions exist, leaders should be embraced irrespective of their actions. Support for this hypothesis is provided by a seminal study conducted by James Meindl and his colleague Raj Pillai at the State University of New York at Buffalo (Pillai & Meindl, 1991). All of the participants in this study were provided with identical biographical information about the male CEO of a fast food company. What the experimenters varied was the information that participants were given about the company’s performance. In four conditions this was presented as either declining steadily or declining suddenly, improving steadily, or improving suddenly. What the researchers found was that the CEO was seen as particularly charismatic when there was sudden improvement in the company’s fortunes and as particularly uncharismatic when there was sudden decline. That is, although there was no difference in what participants were told about this individual and nothing to suggest that he was in any way responsible for the company’s success, participants assumed that the leader had achieved positive outcomes for the group and he was valued accordingly.4

Meindl, along with his colleagues Stanford Ehrlich and Janet Dukerich (1985), corroborated these findings through an extensive archival study of over 30,000 press articles relating to 34 different companies. This revealed a significant and strong correlation between improvement in an organization’s performance and references to leadership in the article’s title. In other words, leadership is seen as relevant and important when a group is doing well. The same relationship was also revealed in analysis conducted at an industry-by-industry (rather than company-by-company) level.

This tendency to explain group performance—particularly improved group performance—with reference to the group leader is referred to by Meindl as the romance of leadership. Meindl sees this “romance” as automatic and almost inevitable—rather like catching a cold. However, the fact that people assume that the leader “did it for us” even in the absence of clear information about the leader’s action does not mean that they ignore such information when it is clearly available. To clarify this point we return to the issue of what leaders do, to the specific matter of fairness and unfairness, and to another of our own studies.

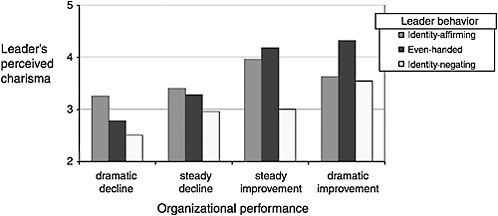

This study (Haslam et al., 2001) was modeled on the research of Meindl and Pillai described above. Participants were told about a student leader, Mark, and about the profitability of his Student Union—which had either improved steadily, improved suddenly, declined steadily, or declined suddenly during his tenure. In line with Meindl’s original work, Mark was seen as most charismatic when there was a sharp upturn and least charismatic when there was a sharp downturn in the Union’s fortunes. But participants were also given information about Mark’s general leadership style, which was either to favor the out-group (in-group identity-negating), to be even-handed between in-group and out-group members (even-handed), or else to favor the in-group (in-group identity-affirming). As can be seen from Figure 5.3, with this variable added to the mix, things began to get more interesting.

The first point to note from this graph is that this information clearly had an effect on judgments of the leader’s charisma in ways that one might expect: overall, identity-affirming leaders and even-handed leaders were seen as more charismatic than identity-negating leaders. The second point is that information about “doing” interacted with information about outcomes to the extent that an identity-affirming leader under conditions of steady decline was rated as more charismatic than an identity-negating leader under conditions of steady improvement.

The third point is that the interactions become particularly intriguing under the conditions of steady and dramatic improvement. Here, it is the even-handed, not the identity-affirming leader who is rated as most charismatic. This might seem at odds with our previous findings that the identity-affirming leader receives most endorsement from followers. But only if one forgets that endorsement and attributions of charisma are somewhat different things. One way of explaining these results, then, is to say that if leaders bring about success by using an identity-affirming style, they might well be endorsed and supported. But, insofar as they have simply done what was expected of them, leaders won’t be attributed any special or unusual qualities. By contrast, when a leader brings about success by bucking

Figure 5.3 Perceived charisma as a function of organizational performance and leader behavior (data from Haslam et al., 2001).

Note: Followers generally perceive leaders as more charismatic the better the organization has performed and as less charismatic if their behavior has been identity-negating. However, the identity-affirming leader is protected from blame in the context of a dramatic decline in organizational performance and the even-handed leader is seen as more charismatic in the context of a dramatic improvement in performance.

expectations (as long as this does not actively negate in-group identity), then he or she will be seen as somewhat special and be accorded charismatic qualities.

These last comments are, clearly, somewhat speculative. But, for all their complexity, what these results clearly underline is the importance of being seen to be “doing it for us.” Leaders who are seen in this way—either because they conscientiously affirm the group’s identity or because they are lucky enough to be in post at a time when the group is doing well—will become more secure in their position.

It is now time to move on and examine whether “doing it for us” also makes leaders more effective in guiding the group. That is, group members might endorse leaders who advance the group interest, but do they actually follow them?

Group interest and social influence

Let us now return more squarely to the question of how acts of fairness and unfairness impact on successful leadership—leadership influence, to be more specific. And let us start with a study from our own program of research that moves us on a step from where we were before.

The study involved participants being informed about another student leader—“Chris” (Haslam & Platow, 2001). Chris had responsibility for deciding who, among his student council, should be given a prize. Some of these council members had adopted positions that were normative for the group (such as supporting gun control or opposing university funding cuts) and some had adopted non-normative positions (supporting university funding cuts or opposing gun control). In three different conditions, participants were told that Chris had either given more prizes to councilors who adopted a normative stance, more to those who had adopted an anti-normative stance, or an equal number of prizes to normative and anti-normative councilors.

The critical dependent measure here was not support for the leader in general terms, but rather specific support for his decision. As we might expect from the studies reported in the previous section, such support was as high when Chris was unfair in favor of normative members as when he was even-handed, but when he was unfair in favor of non-normative members support was much lower. To reframe this in terms we have used previously, in-group identity-affirming decisions were supported much more than identity-negating decisions. This, rather than fairness or unfairness per se, was what counted.

Now, let us advance the argument a step further still. It may be the case that people support leaders when their behavior is seen to affirm the group position, even if they are unfair. But if a leader is seen as group-affirming at one point in time, will this have any effect on support for his or her subsequent proposals?

To provide an initial answer to this question, we can return to the experiment by Platow and colleagues (1997) in which New Zealand university students responded to a decision made by the CEO of a local Health Authority regarding the distribution of time on a kidney dialysis machine between two equally needy people. As we noted above, the students provided relatively strong support for the fair over the unfair leader when the context was purely intragroup, but this pattern was reversed in an intergroup context (see Figure 5.2). One feature of this experiment that we didn’t describe earlier relates to an additional comment that students read in the memorandum supposedly written by the CEO. After describing his policy regarding the distribution of time on the dialysis machine, the CEO ended with the simple statement that memoranda of this nature were “sufficient to inform staff of this policy.” In terms of social influence, the critical test for the researchers was the degree to which the participants would agree or disagree with this general principle, even though the CEO offered no other supporting arguments for it.

The data here were very clear. When the distribution of dialysis time had been between two life-long New Zealanders, the students agreed more strongly with the CEO’s stated opinion if he had been fair rather than unfair in his allocation of time. However, this influence pattern completely reversed in the intergroup context. Now the New Zealand participants agreed more strongly with the attitude expressed by the leader when he or she showed normatively unfair, in-group favoritism rather than intergroup equality. Thus, not only was an unfair leader able to secure relatively strong endorsement, but he was able to actually demonstrate leadership by exerting influence over others.

Platow, Mills, and Morrison (2000) conducted a second test of this influence process in an experiment that involved different social groups and a different influence context. Here New Zealand psychology students served as participants in a context in which their social identity as psychology students was made salient, and dental students served as a comparison out-group. On arriving in the laboratory, the participants were told that they would first be evaluating a series of abstract, 20th-century paintings by Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, and then completing a series of computer-based experimental tasks. However, before judging the paintings, the experimenter informed the participants that extra computer tasks had to be distributed to some, but not all, of the participants (in the same manner as the research by Platow et al., 1997, that we discussed above). Through a series of subtle procedures, the experimenter was able to make these distributions in a public manner while ensuring that the participants realized that they themselves were not recipients of the extra tasks. As in other studies of this type, this latter feature ensured that any pattern of findings would be unrelated to personal self-interest. The experimenter then proceeded to make a fair or unfair distribution of the extra tasks between two unknown psychology-student participants (i.e., in-group members) or between one unknown psychology-student participant and one unknown dental-student participant (an out-group member). As in Platow’s other research, the unfairness in the intergroup context was in-group favoring.

When all this had been done, the experimenter asked participants to complete the painting-judgment task. However, at the start of this, the experimenter made the following seemingly throw-away comment:

I’m not sure whether I should say this, but … personally, I really like Kandinsky. In my work for this project, I’ve come to really like his art. But we’d like you to go ahead and just rate your impressions of each painting as I go through [them].

This simple communication served as the influence attempt. If participants simply conformed to the experimenter’s opinion because of his or her authority, then we would expect all participants subsequently to agree with the experimenter, and rate paintings labeled as “Kandinsky” more positively than those labelled as “Klee.” But this is not what happened. Instead, for those participants who saw the experimenter as a fellow in-group member, that experimenter’s prior fair and unfair behaviors consistently affected the participants’ subsequent ratings of paintings labeled “Kandinsky” and “Klee.” Participants preferred Kandinsky to Klee when the experimenter had been fair within the in-group; but they preferred Klee to Kandinsky when he or she had been unfair within the in-group. Importantly, though, this pattern of influence was completely reversed when the experimenter had made intergroup distributions. Here the participants preferred Kandinsky to Klee when he or she had been unfair and in-group favoring in the intergroup context. On the other hand, they preferred Klee to Kandinsky when the experimenter had been fair between the groups.

In both these studies, then, the leader was only capable of exerting positive influence over followers when he or she had a history of championing the group interest, either by being equally fair to in-group members, or by favoring in-group members over out-group members. In short, we now see that leaders’ capacity to exert influence—the very essence of leadership—rests on their behavior being seen to have “done it for us.”

In an effort to take these ideas still further, we conducted a further experiment that built on the one described above by Haslam and Platow (2001). As in the first study, student participants were told about the behavior of a student leader (again, “Chris”) who had been in a position to reward normative and anti-normative student councilors. Here, though, they were also told that Chris had come up with a new plan to lobby the university to erect permanent billboard sites on campus (you may recall that Platow and colleagues made reference to the same plan in one of the studies that we described in the previous chapter; Platow et al., 2006, Experiment 1). The study examined the support for Chris’s reward policy as well as support for this new initiative. However, on top of this, participants were also asked to write down what they thought about Chris’s decision to push for permanent billboard sites by making open-ended comments and suggestions about the proposal. Independent coders then looked at the suggestions and counted the number of these that discussed positive features of the proposal and that attempted to justify it in some way, as well as those that were critical of the proposal and that attempted to undermine it.

As in the earlier study, participants were more supportive of a policy that was fair or one that rewarded normative in-group members than they were of one that rewarded anti-normative ones. However, beyond this, their support for the leader’s new billboard campaign was also affected by the history of this behavior. More specifically, it was only when Chris had been fair or had stuck his neck out for their group and its members in the past that followers were willing to express support for his future plans.

However, as we have already pointed out several times, the key to leadership lies not simply in getting followers to say that they agree with one’s vision, but in motivating them to do the work that helps make that vision a reality. Many a leader’s grand designs have been left in tatters because the expressions of support that they initially elicited were never translated into anything concrete. Followers’ words of support are cheap; what really counts is their sweat and toil (and sometimes their blood). Accordingly, these are more dearly sought, and less easily bought. The critical question, therefore, is under what conditions will a leader’s vision engage the energies of followers and come to define a collective enterprise? Under what circumstances are followers willing to exert effort in order to ensure that a leader’s aspirations are realized? When will the leader’s word become the follower’s command?

Because it helps answer these questions, the really interesting data from the study we are currently discussing emerged from participants’ open-ended reactions to Chris’s billboard policy. As the data in Figure 5.4 indicate, these provided evidence of a pattern that was rather different from that observed on measures of expressed support. Specifically, although Chris had elicited equal levels of support for his billboard policy when he had been fair or identity-affirming, students’ willingness to generate helpful arguments that supported or justified the proposal differed markedly across these two conditions. When Chris’s behavior had been in-group identity-affirming, students typically generated at least one argument in support of the billboard scheme. However, when he had been in-group identity-negating or fair, the silence from his followers was deafening. In both conditions students provided virtually no helpful comments, and those that they did offer were actually outnumbered by their unhelpful ones. Support for Chris the even-handed leader thus proved to be ephemeral and half-hearted, while support for Chris the identity-affirming leader was substantive and enduring. Only when he had a history of championing the group and its members was the group prepared to stand up for him and do the work (in this case the intellectual justification and rationalization) necessary for his vision to be realized.

Figure 5.4 Ideas generated by followers in response to a leader’s vision for the future as a function of that leader’s prior behavior (data from Haslam & Platow, 2001).

Note: Followers only generate ideas that advance the leader’s vision when the leader’s prior behavior has affirmed the group’s identity. If that behavior has been even-handed or identity-negating then, on balance, the ideas they generate are unhelpful.

Here, then, we see that the leader’s championing of the in-group interest impacted directly not only on his ability to demonstrate leadership (i.e., to influence the views of followers) but also his capacity to achieve impactful leadership (i.e., to engage followers so that they contributed to the achievement of group goals).

In sum, then, it is neither fairness nor unfairness that enhances leadership standing, leadership performance, and leadership achievement. What matters is championing the group.

Clarifying the group interest

There is one final twist to our tale. This may seem a rather arcane point and it is often overlooked or misunderstood. But nonetheless it is of critical importance both conceptually and practically. It is also at the core of what we will argue in the chapters that follow.

Throughout this chapter we have argued that, to be effective, leaders need to support the group interest in ways that are contextually appropriate rather than to display a set repertoire of behaviors. This argument stands. However, thus far, we have not really explored the notion of “group interest” itself. In particular, we have not asked what sort of things actually constitute this interest. Implicitly, though, we have generally associated group interests with an increase in material resources for group members. Indeed, in most of the studies we have reported, the group interest has been equated with giving one’s own group more than others. The message could be read as “leaders who are unfair to the out-group will always thrive.” This would be a depressing conclusion as it would suggest that intergroup inequality is part of our very nature. Fortunately, however, it is a misreading both of the social identity approach and of our approach to leadership.

When we introduced social identity theory in Chapter 3, we explained that one of its core premises is that people seek positive distinctiveness for their group. They want their group to be better than others. However, equally, we stressed that what “better” means for any given group depends on its specific norms and values. These define what actually matters to group members, and what they want to have more of. Certainly, this can often be material resources: we want to be richer, we want to have more. Equally, it can often be related to dominance and status: we want to be more powerful, we want to be stronger. In all these cases the valuation of the in-group generally means being anti-social to relevant out-groups.

But this is not necessarily the case. Sometimes a group might define itself in terms of spiritual values: we want to be loving, to be charitable, to be kind. In this case, positive differentiation can manifest itself in being pro-social towards the out-group: cherishing them, helping them, being kind them. To put it slightly differently, it is the things we value in our in-groups that determine how processes of differentiation play themselves out (see Reicher, 2004; Reicher et al., 2010; Turner, 1999). And, even if we have no control over basic group processes, we certainly do have choice over our group beliefs and ideologies. This is a point that was expressed forcefully by Martin Luther King in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail”:

Was not Jesus an extremist for love … Was not Amos an extremist for justice …? Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel … And Abraham Lincoln … And John Bunyan … And Thomas Jefferson … So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists will we be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or the extension of justice?

(King, 1963, p. 88)

Now, exactly the same considerations apply when we address the concept of interest. If we think of “interest” in terms of getting more of what matters to us, then in any given circumstance, exactly what outcomes constitute the promotion of interest will depend on what it is that we value. In the case of groups, the meaning of “promoting group interest” will therefore depend on the norms and values of the group in question. And if it is crucial for successful leaders to advance these interests, then they can only do this if they are aware of these values and norms and hence have an understanding of what “promoting group interest” means in concrete terms.

As far as fairness and unfairness are concerned, then, intergroup unfairness may well enhance the leader’s position to the extent—and only to the extent—that the group values material well-being. However, it won’t do so where the group’s values center more on fairness, spirituality, or asceticism. In such cases having more could even be seen as a thoroughly bad thing that compromises rather than promotes the group interest (Sonnenberg, 2003). All in all, then, it is too simple to conclude that leaders will always thrive by displaying intragroup fairness and intergroup unfairness. It is more accurate to say that leaders thrive by acting in line with group values and norms.

To underline this point, let us finish with a simple but powerful example. This comes from the world of sport—normally a domain that is highly competitive and in which groups take pleasure in doing down their opponents. But if there is one place in the world of sport where different norms prevail, where respect for one’s opponent is critical, and where (at least in theory) taking part is more important than winning, it is the Olympic Games. During the summer Olympics of 2000 in Sydney, a survey of Australians was carried out in which people were asked how much they supported leaders who either favored the in-group over the out-group or else treated the two groups equally (Platow, Nolan, & Anderson, 2003). The results were as clear as ever, but now they went against the pattern we have reported time and again in this chapter. In this context, where norms of consideration and fairness were to the fore, the leader who favored the in-group was endorsed less than the leader who was even-handed. Where what we value, above all else, is fairness to all, fairness to all is what a leader needs to deliver.

Conclusion: To engage followers, leaders’ actions and visions must promote group interests

In this chapter, we asked what leaders need to do in order to be effective. We organized our discussion around what is widely recognized as one of the key activities in which leaders engage: dealing with different people and making decisions about how to treat them. We started by investigating the basic proposition that leaders have to be fair—and we discovered that there are indeed many occasions and many ways in which fairness will entrench not only the position of the leader in the group but also the position of the leader in society. However, as the chapter unfolded, we showed that things are not always so simple. Yes, sometimes leaders will thrive through fairness, but equally they will sometimes thrive through unfairness, especially unfairness in allocations between groups. One way of resolving this apparent paradox is to say that leaders need to be fair within their in-group but to favor that in-group over other out-groups. But we then discovered that even this resolution is too simple because, depending on group norms and values, there will be times when favoring the in-group will be applauded and times when the leader who shows such partiality will be condemned.

The one constant that shone through all these twists and turns was thus not a matter of behavior but of process. What leaders need to do is to promote the group interest in the terms specified by the group’s own norms and values. This last clause is critical. It means that, if the leader is to provide the group with the things that matter to it, he or she has to have specific cultural knowledge of the group in question. We have said it before and we will say it again, but it is sufficiently important to bear saying here as well: for would-be leaders, nothing can substitute for understanding the social identity of the group they seek to lead. There are no fixed menus for leadership success, it is always à-la-carte.

Extending this point, what we have seen as this chapter has progressed is that leaders who take care to promote the group interest (more colloquially, those who are in-group champions, those who “do it for us”) reap many benefits. They receive endorsements from followers, they are likely to be seen as charismatic, they influence the opinions of their followers, and they are able to enlist the efforts of their followers in bringing their visions of the future to fruition.

This last point is critical. Vision, after all, is often seen as the thing that marks out great leaders. To quote the Australian religious commentator, Bill Newman:

Vision is the key to understanding leadership, and real leaders have never lost the childlike ability to dream dreams … Vision is the blazing campfire around which people will gather. It provides light, energy, warmth and unity.

(cited in Dando-Collins, 1998, p. 162)

But, on its own, vision is of little use. Many people have a clear and powerful sense of the future, but this alone does not make them leaders. After all, having visions can also be a sign of lunacy. People only become leaders, then, when their vision is accepted by others. As James Kouzes and Barry Posner put it in their best-selling book The Leadership Challenge:

A person with no constituents is not a leader, and people will not follow until they accept a vision as their own. Leaders cannot command commitment only inspire it. Leaders have to enlist others in a common vision.

(2007, p. 17; emphasis in original)

So what determines whether a vision is solitary or whether it becomes shared? When do we dismiss self-styled seers as delusional and when do we hail them as prophets who are leading us to the Promised Land? It is hard to overestimate the importance of this question. As the historian Andrew Roberts observes, it is one that “lies at the heart of history and civilization” (2003, p. xix). The answer certainly is not to be found in the nature of the vision itself or in its strength. Confirming this point, David Nadler and Michael Tushman conducted an extensive review of research that tracked leaders’ performance prospectively over extended periods. Their conclusion was stark: “unfortunately, in real time it is unclear who will be known as visionaries and who will be known as failures” (1990, p. 80).

Perhaps so. But followers are not completely helpless in distinguishing between visionaries and failures. They can look at the track record of leaders. They can inspect the visions themselves. More particularly, they can ask what these things say about the relationship between the visionary’s perspective and their own collective perspective. Moreover, it is this relationship that ultimately determines whether or not a vision becomes shared. And it is in pointing to the importance of this relationship that the contribution of this chapter lies.

For it is where followers can see that a leader is attuned to their sense of what counts in the world, where they have evidence that he or she is committed to advancing “our cause,” where the leader can be seen to act for the group rather than for themselves, that they will embrace the leader’s vision as their own. To extend Newman’s analogy of the campfire a little further, where a leader’s vision is seen to promote group goals, then others will help fan the flames. But when this vision is seen to serve other interests, then the aspirant leader will be shunned as a dangerous pyromaniac and others will douse the fire.

The important point, then, is that leaders can do something to ensure that their vision becomes shared. Leaders’ actions can make a difference in binding them to followers and vice-versa. Leadership is not a matter of chance, it is not a matter of fate, it is not something one is born to. It is something in which leaders themselves can be active agents by knowing how to configure their own behaviors in relation to group identities. Indeed, in a very important sense, we have so far under-represented the extent of this agency. This is because, throughout this chapter (and also in the last), we have looked at how leaders can present themselves and shape their action so as to reflect the terms of group identity. But we have treated the groups and their identities as if they themselves were givens. That is, we have looked at how leaders are able, and need, to fit the group mould. What we have not considered is that they might achieve a fit by shaping the mould itself.

To be more concrete, one of the points that has become clear as this chapter has progressed is that leaders very often need to behave differently in intragroup and intergroup contexts. Often (though not always) they thrive by displaying intragroup fairness and intergroup partiality. In making this argument we may appear to presuppose that leaders act in a world where the groups themselves are set in stone, where it is absolutely clear who is “us” and who is “them.” But this is self-evidently not the case. Often these things are most unclear. Should radical and moderate feminists see themselves as opposed, or are they all feminists confronting a patriarchal world? Who should we see as fellow nationals—all those living in and committed to the country, or only those who were born in the country and who have parents with similar credentials? These and many other similar debates constantly rage around us (see Billig, 1996).

Our point is not simply that leaders can play a part in shaping these debates—and hence shaping the very groups they seek to represent—but also that the ways leaders treat people as similar or as different play a critical part in drawing category boundaries. If we are fair in our treatment of people, the implication is that we are all “in it together.” If we are unfair, the implication is that we are in different camps. This is an insight that this book’s third author confirmed in research with colleagues that presented participants with a situation in which two people had done some work, and a third person then paid them either fairly or unfairly (Platow, Grace, Wilson, Burton, & Wilson, 2008). After observing this behavior, the participants were asked to infer potential group memberships between these three key players. When the distributions were fair, participants inferred a single group membership between all three people. However, when distributions were unfair, participants inferred that the person making the distribution and the favored recipient shared a common group membership and that the unfavored recipient was an outsider.

In a second study, participants read about a researcher who was planning to hire two research assistants, paying them either equally or unequally. For some participants, both research assistants were described as fellow Australians (an intragroup condition). For other participants, one research assistant was described as a fellow Australian and the other was described as a French national (an intergroup condition). In the intragroup conditions, it was when treatment was fair that people felt most Australian. In the intergroup conditions, it was when treatment was unfair (and in-group favoring) that people felt most Australian.