1 Mapping European Cinema in the 1990s

In the early 1990s, Europe became, as if it had not been so before, a question of space. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the breakup of the Soviet Union, the break-down of Yugoslavia, and the unification of Germany produced radical upheavals in every aspect of European life, but most urgently, they made a collective demand on an idea of Europe as a psychic, cultural, or geopolitical location. For the first time since the end of World War II, the borders of Europe were disconcertingly unstable. Through the 1990s, this traumatic overturning of spatial categories was augmented with a more gradual, although by no means painless, redefinition: the expansion of the European Union to include members and potential members as far apart as Finland, Bulgaria, and Turkey. It is clear that as the physical and political territory of Europe altered in the post–Cold War years, so, too, did its cultural imaginary. What is less clear is how we can read these changes cinematically: how European cinema represented revisions of European space narratively, formally, and stylistically, and, indeed, how the terrain of “European cinema” itself was acted on by the forces that were reshaping the continent.

Rethinking Post-Wall Europe

This question of Europe has grown in stature over the years since 1989, in cinema studies no less than in political philosophy. While Jacques Derrida’s 1991 essay The Other Heading inaugurated an important philosophical discourse on the “new Europe,” the British Film Institute’s 1990 conference “Screening Europe” had already asserted a comparable inquiry into the new European cinema and where it might be heading. For the conference participants, as for Derrida, the possibility of European identity formed a central, and often troubling, problematic. Filmmaker Chantal Akerman claimed that there is no such thing as a European film, while critic John Caughie described the difficult process of becoming European.1 Derrida pinpoints the difficult nature of this identity: the half-constructed European subject is caught between the devil of nationalistic dispersion and the deep blue sea of Eurocrat homogenization. Thus, “the injunction seems double and contradictory for whoever is concerned about European cultural identity: if it is necessary to make sure that a centralizing hegemony (the capital) not be reconstituted, it is also necessary, for all that, not to multiply the borders, i.e. the movements and margins…. Responsibility seems to consist today in renouncing neither of these two contradictory imperatives.”2 For an ethics of Europe, Derrida argues, this bind demands an impossible duty in which the European subject must respond, simultaneously, to two contradictory laws. European cinema, it seems, experiences a similar structural dilemma: how to become European—as opposed to simply continuing an older model of national cinemas—without degenerating into the filmic correlative of Brussels bureaucracy, the Europudding.

As film historian Mark Betz has noted, this debate obscures at least as much about European cinema as it illuminates. Films made in Europe have frequently been coproduced by two or more countries at least since World War II, and the idea of “pure” national film cultures is a myth.3 According to this historical revision, “Italian” or “French” art films are always already European, and the anxieties of the cultural moment immediately after the fall of the Berlin Wall (post-Wall) miss the point or, at the very least, beg the question. Betz points to a telling moment in the British Film Institute (BFI) conference, where a question from the audience about coproduction went unanswered by the panelists, who were unable or unwilling to consider European-ness as part of a mode of production. However, although Betz is quite correct that this unanswered question is symptomatic of an inability to think about European identity, the nature of this missed point is also significant—and has consequences both for European film production in the 1990s and, more to my point, for the developing model of its critical response.

For although we cannot directly map a political anxiety about national versus supranational sovereignty onto the film community’s unease around international coproduction, we can make out a discursive commonality in both cultural and political mobilizations of “Europe” in the post-Wall years. Once again, Derrida establishes the terms of the debate, when he calls for a Europe that refuses self-identity and engages rigorously with what he terms “the heading of the Other.” This ethics of the Other combines the contemporary philosophical elaboration of Emmanuel Levinas with a reading of Europe as a spatial and temporal figure (the “heading”). Clearly, this is a reading of some subtlety, but, given the level of ideological struggle over the terms and conditions of the new Europe, it is perhaps not surprising that public discourse on European identity tended to take up the question in exactly the binary forms of Europe/Other that The Other Heading problematizes. Thus, while conservatives made national sovereignty, immigration, and ethnic minorities into social problems, film cultures evolved an opposing liberal concern with regionalism, minority representation, and transnationalism.4

I do not want to condemn this shift, either as a series of cinematic practices or as a critical paradigm. The manifold concerns of, say, diasporic Turkish filmmakers, beur film, and European film studies cannot be reduced to one ideological imperative, and insofar as we can identify common ground, this is a terrain that has been highly productive, both creatively and theoretically.5 However, it seems to me that to focus on films that narrate the “Other” of Europe so directly, that articulate an anti-Eurocentric hybridity so transparently, is ultimately a self-exhausting critical endeavor. Derrida asks:

Is there then a completely new “today” of Europe beyond all the exhausted programs of Eurocentrism and anti-Eurocentrism, these exhausting and yet unforgettable programs? (We cannot and must not forget them since they do not forget us.) Am I taking advantage of the “we” when I begin saying that, in knowing them now by heart, and to the point of exhaustion—since these unforgettable programs are exhausting and exhausted—we today no longer want either Eurocentrism or anti-Eurocentrism?6

I, too, would like to take advantage of the “we.” If we are to take seriously the post-Wall European subject’s impossible responsibility, we cannot stop with a comfortably liberal celebration of the Other. To adapt Paul Gilroy’s notion of anti-anti-essentialism, any theoretical revision of European cinema needs to articulate an anti-anti-Eurocentrism.7

Such a position has recently been explored outside the field of film studies. Always good for a provocative line, Slavoj Žižek poses the question thus: “When one says Eurocentrism, every self-respecting post-modern leftist intellectual has as violent a reaction as Joseph Goebbels had to culture—to reach for a gun, hurling accusations of protofascist Eurocentric cultural imperialism. However, is it possible to imagine a leftist appropriation of the European political legacy?” Žižek begins to answer his own question (albeit in the form of another question) when, in a different article, he asks, “How are we to reinvent political space in today’s conditions of globalization?”8 What is crucial in this second formulation is that Žižek, like Derrida, stages the question of Europe as simultaneously a matter of space and of time. The time is punctual: Europe is a topic of today. Žižek is no less concerned than Derrida with today’s conditions, but he speaks from a different location, quite literally. The European political legacy is conjured here not from Europe’s headland, the cape, or capital inhabited by French philosophy but from the rapidly changing space of southeastern Europe: the recently and painfully redrawn map of the Balkans.

Why should we care from where each writer writes? Their locations matter not because their nationalities are intellectually determining but because anti-anti-Eurocentric thought intervenes in the relationship between material and discursive spaces. For Derrida, this means the wide-ranging social effects of the heading: the logic by which Europe imagines itself as a spatial and temporal advance-guard for the world. For Žižek, it demands a rethinking of political space, the space of politics, in the temporally constituted terrain of “the former Yugoslavia.” We could point, also, to Etienne Balibar’s work on European identity, which analyzes the meaning and constitutive power of borders.9 Like the heading, the border is a spatial trope that is rhetorical but not merely metaphoric. In centering his discussions of European racism and transnational identity in the figure of the border, Balibar illustrates the theoretical desire to articulate material borders—politically defining spaces—with and through the idea of Europe, its discursive imaginary.

Like this work in political philosophy, I would suggest, film studies needs to form the question of Europe as a matter of space and of time. An anti-anti-Eurocentric consideration of contemporary European cinema must not speak only of coproduction, of European Union funding, and of national heritage; neither must it speak only of the diasporic, the hybrid, and the radical. Rather, it must take on the logic of cartography: a form of writing that articulates both the discursive and the referential spaces of nations (recall that both Borges and Balibar imagine the mapped border as performative, a slippery relationship of image and referent). Cartography encompasses writing and drawing, politics and aesthetics, the political and the physical; it binds spectacle to narrative, graphic space to geopolitical space. And post-Wall European cinema, I will argue, mobilizes exactly this enunciative structure. It maps the spaces of Europe “today,” speaking both of and from the changing spaces of the continent. Most important, it does so as a textual work, coarticulating cinematic space and geopolitical space.

The production of cinematic space has been a recurrent area of film theoretical inquiry, where space is always, to some degree, understood in a relationship to time, temporality, or history.10 The nature of the (temporo-spatial) relationship between profilmic space and cinematic space plays a fundamental role in theories of cinematic specificity. As such, space is a determining element of the cinematic per se. This question has of late returned to theoretical prominence—and not coincidentally. In an article on theorists of cinematic specificity, Thomas Elsaesser—another European theorist who elsewhere has been explicitly concerned with questions of Europe—glosses Siegfried Kracauer thus:

In the often tortuous dialectic between photography and history which Kracauer was at pains to tease out all through his life, the cinema is given a redefinition which, it seems to me, is neither strictly ontological nor epistemological, and yet allocates it a place in a fundamental development of the Western mind: the systematic translation of the experience of time into spatial categories, as a necessary precondition for an instrumental control over reality, but with its equally necessary corollary, namely a narcissistic or melancholy bind of the subject to that reality as image, itself envisaged in the psychologically coherent but ideologically ambivalent form of loss and nostalgia, fragment and fetish.11

This is an astonishingly rich passage, reading cinematic space both through Kracauer’s ontological insistence on the essential qualities of the cinematic image and, at a slightly greater remove, through his Marxism. By extension, Elsaesser implies, we must conceive the historicity of the cinematic image at once in terms of the temporality of the subject and in terms of a dialectical understanding of historical process.

Here, Elsaesser (and, indeed, Kracauer) speaks of history as such, the category of temporality that is overcome, or at least tamed, by its translation into images, into film, into space. But, of course, Elsaesser is also historicizing both Kracauer and this ideological work of cinema in the context of the “real” histories of the twentieth century. The desire for an “instrumental control over reality” leads inevitably to theories of fascism and to the particular uses of geopolitical space, and of the cinematographic image, in twentieth-century Europe. We cannot separate these theoretical discourses on cinematic space and time from the histories and places that have underwritten them; this is no less true for the history of the post-Wall continent than it is for the traumas of mid-century. As the borders of Cold War Europe crumbled, so, too, did dominant narratives of postwar history and, to some extent, the theoretical apparatuses with which history could be thought. It is for this reason, perhaps, that Elsaesser’s contemporary rereading of Kracauer seems to resonate so deeply. For in the European cinema of the 1990s, the cinematic image becomes readable precisely as a troubling of space and time. Certain European films, I will demonstrate, textualize this uncomfortable encounter, and they do so exactly as Elsaesser’s contemporary reading of the cinematic suggests: through a mobilization of the historical image that is inflected with those fin de siècle themes of “loss and nostalgia, fragment and fetish.”

Where, then, does one start in the drawing of maps? It is tempting to essay the bird’s-eye view, the imperial sweep of the world map, with which we can locate European cinema in its proper relation to international currents. To be sure, post-Wall cinema can be viewed as a part of postclassical or even postmodern cinema: it must operate in the eddying currents of global film markets, the development of new distribution and exhibition structures, and the festival-fueled circuits of international art cinema. We can chart material relationships among European art cinemas, Hollywood blockbusters, and the East Asian New Waves, or we can draw theoretical connections around the uses of spectacle, genre, or affect in these contemporary forms. For better or worse, we must do these things. “European cinema,” as a cultural discourse, cannot signify without reference to at least one Other, and if Hollywood has been the dominating Other throughout most of the history of European film production and criticism, it is now necessary to consider a global dimension.

Many European films circulate in a global art film market, in which European-ness asserts specific (although not constant) levels of both cultural and economic capital. European films code internationally as both “not-American” and, in many markets, “not-Asian,” “not-Latin American,” and “not-Middle Eastern.” In addition to these external references, films—even coproductions—function within an internal European hierarchy, where French, British, and Italian mean quite different things to audiences than do, say, Czech, Swedish, and Portuguese. These encrustations of cultural meaning are by no means new (although the range of foreign films available in many markets is), but they are mutable, and like any other historical period, the postclassical era can be characterized by specific forms. In the 1980s and 1990s, this environment produced new kinds of production (television funding, increased coproduction, main-stream/art house crossover films) and new areas of critical interest (heritage culture, postcolonial and minority representations, transnationality). However, while we must keep in mind these large-scale charts of contemporary world or European cinemas, I am not convinced that we approach the question of cartography best by means of such a map. Rather than chart the shapes of European cinema exhaustively from above, it might be more in the spirit of mapping to trace some of its disputed borders: that is, to consider the debates in and around which an analysis of European films can be located.

Whither Heritage?

Particularly prevalent in western Europe, the heritage film is a critically and industrially contentious notion that gets to the heart of contemporary discourses on European culture, identity, and film production policy.12 Like many such critically invented terms, the heritage film is not an easily definable category. In general terms, however, we can say that such films use high production values to fill a mise-en-scène with period detail, representing their national pasts through sumptuous costume, landscape, and adaptations of well-known literary novels. Generally costume dramas (the name is telling) rather than history films per se, and mostly dealing with romanticizable eras such as the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, these films are most often criticized as nostalgic attempts to whitewash the national past for both reactionaries at home and the more gullible foreign markets. Critical and industrial debates here intersect, for the popularity of the heritage film has led to an emphasis on such projects among west European state funding bodies. By popularizing the historical in terms of nostalgia and mise-en-scène, the heritage film has opened up a space within European film culture, not only for increased American and domestic box office but also for a renewed circulation of national identities.

The heritage film has been widely criticized within Europe. Andrew Higson argues that British heritage films cover over political critique with pleasurable mise-en-scène, while Antoine de Baecque considers that what he terms “official” European cinema has a common polish, a homogenized prettiness that lacks genuine engagement with place. Instead of representing the genuine differences in European cultures, he claims, heritage films smooth out history and image. De Baecque contrasts this negative view of an official European cinema with what he considers a contemporary countercinema, including films by Emir Kusturica, Lars von Trier, Alain Tanner, Pedro Almodóvar, and Otar Iosseliani.13 Several of the films I will be considering fit neatly into de Baecque’s and Higson’s notions of the regressive European film: Cinema Paradiso (Tornatore, 1988), for instance, has been widely viewed as an Italian iteration of the British nostalgic heritage film. Especially in the context of international distribution, this type of film is often seen to lose whatever edge a national narrative might involve and to appear to foreign audiences as just another pretty European indie.

And yet, it will be apparent that my intervention is not that of de Baecque, for while he contrasts Kusturica and von Trier as counterauteurs to the official discourse of Bernardo Bertolucci and la belle image, I will be examining some very pretty films alongside those of Kusturica and von Trier. For just as postclassical cinema has blurred the distinction between art house and mainstream, so it is ultimately untenable to maintain the mainstream/countercinema binary in the changed terrain of contemporary European cinema. The nub of this debate is the status of the spectacular image, which for Higson operates to distract the spectator from any political content in the narrative, and for de Baecque provides too beautiful an image of European history and culture. While this argument makes sense when films as disparate as La Vie de Bohème (Kaurismäki, 1992) and Camille Claudel (Nuytten, 1988) are compared, these boundaries break down when other examples are considered. Films like Chocolat and Beau Travail (Denis, 1988 and 2000) use a lush mise-en-scène in the context of a complex reconsideration of French colonial history, while filmmakers like Derek Jarman and Peter Greenaway use countercinematic forms to reimagine typical heritage topics like literary adaptation—Prospero’s Books (Greenaway, 1991)—and artist biopics—Caravaggio (Jarman, 1986). Thus, rather than attempting to separate out the good and bad versions of European heritage cinema, I want to exert some pressure on the terms of debate: to take seriously la belle image and to pinpoint what kinds of historical and spatial engagements the heritage image enables.

Camille Claudel Camille is framed by monuments of European cultural heritage.

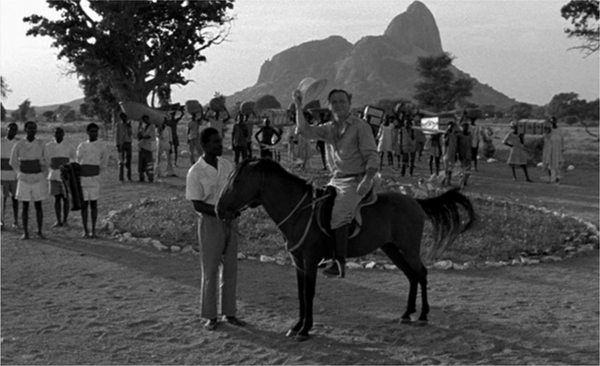

Chocolat Landscape images stage a critique of European colonialism.

Although Richard Dyer astutely points to the significance of the stately home in British heritage films,14 the visual center of la belle image is landscape. Whether the Tuscan orchards in A Room with a View (Ivory, 1985) or the Provençal poppy fields in Manon des sources (Berri, 1986), the genre depends on the production of a beautiful landscape, often drawing from European traditions of Romanticism and realism in painting, in which its historical romance narratives can take place. And for Higson, de Baecque, and most other readers of the heritage genre, it is axiomatic that both the melodramatic narratives and these spectacular images preclude any progressive historical engagement. This argument, however, depends on assumptions about both melodramatic form and the cinematic image that are by no means self-evident. The substantial bodies of film theoretical work on melodrama and on the image demand that we use a more nuanced approach to read their intersection with history, nation, and spectacle. If we begin by theorizing the relationships among specific national histories, landscape images, and melodramatic narratives, it might be possible to map the heritage film differently.

The British films that first defined the heritage film tend, like Cinema Paradiso and Manon des sources, to narrate apparently apolitical histories. We will need to reconsider this commonsense attribution of “politicalness,” as this is one of the points on which discourse on heritage proves weak. However, even before we problematize the notion of a political history, it is clear that some heritage films do narrate political stories and use national or landscape images as part of this process. Most obviously, there are the World War II melodramas in which a romantic story intersects more or less closely with the history of Nazism. Recent examples include Aimée and Jaguar (Färberböck, 1999) from Germany and the Spanish drama ¡Ay, Carmela! (Saura, 1990), although this trope is not exclusively post-Wall and slightly older examples such as La Dernier Métro (Truffaut, 1980) are also common. Tying a melodramatic narrative closely to the idea of national space is a film like When I Close My Eyes (Slak, 1993), in which Slovenian history returns to haunt the present in the image of a field where the heroine’s father was killed for his political activism. Landscape here is far from beautiful nature, and yet the heritage structure of national melodrama is similar to that of the west European films.

A more troubling example is Land and Freedom (Loach, 1995), a film that is usually read in the context of Ken Loach’s politically committed oeuvre, and yet uses national landscapes and melodramatic narrative in a way very similar to that of the heritage film. Here, just as in Cinema Paradiso, there is a young male protagonist, a beautiful southern European setting, and a narrative centered on romantic loss, framed by a present-day coda from which point the historical past can be looked back on with a certain nostalgia. In Land and Freedom, the historical setting is the Spanish Civil War, and the hero is a young British man eager to fight for freedom by joining up with the Spanish Republicans. His letters are found by his granddaughter in the 1980s, at a moment in British history when socialist solidarity was radically undermined. The political overtones of the story are overt, but melodramatic convention demands that political investment be embodied in an object of romantic desire. Thus, the death of the beautiful soldier Blanca prompts emotion, with politics and romance intersecting when the “Internationale” is played at her funeral. What is suggestive about this example is that Loach is rarely considered in terms of melodrama, much less the heritage film, and indeed he is often cited as precisely the opposite. Thinking about Land and Freedom in relation to the visual pleasure of the landscape image, and in terms of nostalgia for a lost past, demonstrates the porousness of the heritage/countercinema boundary and the way in which we might begin to think about issues of nostalgia and spectacle as ideologically weighted.

Framing Popular Memory

The imbrication of history and nostalgia in art cinema predates the heritage film, with the French popular memory debates of the 1970s forming a discursive nexus in which Marxist and poststructuralist theories of historicity intersected with a French cultural reexamination of wartime collaboration and other national histories. Films like Lacombe Lucien (Malle, 1974) became controversial for their revisionist—and unheroic—depiction of the French Resistance and the collaboration of the French populace during World War II, and film theorists such as Marc Ferro and Michel Marie were joined by Michel Foucault and by disciplinary historians in debating the ethics and aesthetics of representing the national past.15 In an interview with Foucault, the editors of Cahiers du Cinéma take a firm stand against la mode rétro (retro style), claiming that Lacombe Lucien and The Night Porter (Cavani, 1974) are both cynical and reactionary, fetishizing the décor of the past while ignoring real history. Foucault, for his part, glosses the rhetorical strategy of such films, claiming that a refusal of heroism is not the refusal of rightist nationalism that one might think: “But below the phrase, ‘There were no heroes,’ is hidden another phrase which is the real message: ‘There was no struggle.’”16 If the new style of historical film was widely read as reactionary on the Left, it was nonetheless viewed as illustrative of an important shift in historical representation: later in the same interview, Foucault asserts that there is a battle being waged over history, with the ownership of “popular memory” as its central contest.17

This debate responded to existing trends in west European film culture: as Pierre Sorlin argues, many history films from this period do not represent stable narratives of historical truth but are constructed as inquiries still in progress. He cites Alain Resnais’s Stavisky (1974), and we could also point to similarly canonical instances from other national cinemas: Die Patriotin (Kluge, 1979), say, or The Conformist (Bertolucci, 1970). However, the modernist art cinema’s formal destabilizing of classical historical narrative remains peripheral to the question of popular memory. Lacombe Lucien is structured as a fairly classical history film, and while the French historians’ debate touches on formal deconstructions of historical “truth,” its real concern is with the radical implications of constituting memory—individual and cultural—as a legitimate category of history writing. In cinematic terms, this impetus is readable less in films that problematize linear narrative and more in films that stage such partial cultural memories as history.

In fact, we can see this structure at work even in the more modernist texts. The Conformist, like Lacombe Lucien, stages conformity, like collaboration, as a survival strategy for a young male protagonist. In both films, the generation gap between youthful protagonist and middle-aged audience and critics enables the history represented to be read as memory: the recovered traumatic past of the sometimes less-than-heroic wartime generation. In the popular memory debate, it is exactly the status of the subject of memory that is in question. Whose memories are these, and where does facing up to the past shade into recuperating unethical national acts through nostalgic regression? Clearly, this was a central question for French public intellectuals in the 1970s, at the moment when World War II was returning as a pressing cultural question. As Germany and Italy began to look back on the fascist past, so France was able to face the history of Vichy more directly.18 But the cinematic engagement with popular memory is not bounded by this moment in French national discourse or by attempts to interrogate wartime histories: throughout the 1980s and 1990s, narratives of memory, and particularly childhood memory, became a popular subgenre in European cinemas.

Structuring personal rather than heritage histories, these films narrate a young protagonist coming of age in a historically specific setting, with the story often framed as flashbacks or narrated as memory by the same character as an adult looking back at his past. Many of these films use comedy to locate national histories within “universal stories” of family drama and childhood romance: here we can point to My Life as a Dog (Hallström, 1985) and Toto le héros (Van Dormael, 1991). In others, the comedy involves a more satirical view of national history, and, given the region’s histories of both black comedy and political censorship, it is perhaps not surprising that many examples of this use of the childhood comedy trope come from eastern Europe. Thus, both When Father Was Away on Business (Kusturica, 1985) and Tito and Me (Marković, 1992) poke fun at Communist Yugoslavia, while emphasizing political distance from their critiques by dint of careful location of the story in the historical past. Less ideologically contentious than the French films, these later invocations of popular memory can seem open to the same critiques as the heritage film: the problem becomes not a self-absolving version of history but yet another avoidance of the political, this time through the self-involved world of childhood.

But if the political clarity of the Cahiers debate was obscured in the various iterations of national popular memories, it became a defining strand of British cultural criticism from the 1970s through to the 1990s. British writers recast the question of memory in terms of class and identity, while interrogating the relationship between realism and the historical image as a matter of representational ethics. Television provided the first object of critical attention, with Ken Loach and Tony Garnett’s series Days of Hope (1975) becoming an ongoing subject of scholarly contention in the pages of Screen.19 The series looked back on British labor history, depicting a working-class family’s experiences from World War I to the General Strike of 1926. While the complaints of viewers about inaccurate costuming details were cited in Screen as misunderstandings of the ideological valences of social realism, such public investment also demonstrates the ethical and emotional stake, for the national audience, in popular memories. The question of who remembers connects these texts to the French ones, where the claim to speak for working-class subjects produced a debate on the implications for realism of any such staging of remembered experience.

The issues of nostalgia and spectacle were added to those of class representation when, over a decade later, Caughie and others debated the ideological implications of Terence Davies’s films Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988) and The Long Day Closes (1992).20 In these films, Davies frames his 1940s and 1950s families in a series of tableau-like shots, aping the look of slightly stiff family snapshots, but also foregrounding an excessive, not quite realist mise-en-scène. History here resides in the details of clothing and cosmetics, the faded colors of old floral dresses, and the romantic popular songs sung with gusto by the women and viewed with melancholy irony by the present-day spectator. Like the films of the Merchant Ivory team, and even Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence (1993), Davies’s emphasis on the material details of the historical mise-en-scène is criticized by Caughie and others as fetishistic.21 However, the films’ emphasis on working-class families, and particularly on the lives of working-class women, enables a countering argument in which the detritus of popular memory, and its tendencies toward nostalgia and melancholy, is precisely the point.

Distant Voices, Still Lives Popular memory is staged in family tableaux. (Courtesy British Film Institute)

Davies, like his contemporary Derek Jarman, is readable in terms of queer authorship: both directors are/were openly gay, and while Jarman’s films are often more radical in textualizing queer subjectivity, Davies mobilizes a subtler tessellation of autobiography, memory, and a politics of representation. The protagonist of Distant Voices is nowhere coded as gay, although extratextual discourses situate the film as partly autobiographical. More to the point, the fetishistic rendering of the historical mise-en-scène locates the film’s enunciation in the feminine spaces of memory-work, where the women of the family—and the protagonist who looks back—stitch together identity out of the harsh stuff of life. Reading the image this way, we can see the excessive elements of mise-en-scène as projecting a fantasmatic space for the gay (or female) subject in an oppressively macho historical scene. Nostalgia here, like Jarman’s entirely nonrealist queer histories, is inevitably overwritten with pain, refusing the contemporary discourse of an apolitical and frictionless nostalgia, in favor of a difficult return that is closer to the term’s original meaning.22 Thus, in Distant Voices the nostalgic appeal of the women’s camaraderie is offset by the men’s casual brutality and emotional impotence. The family tableaux, which structure nostalgic memory in their faded colors and in their “old photograph” compositions, demand a doubled reading. On the one hand, the scenes are affective, staging the past through melancholic loss. On the other hand, the fragile nature of this nostalgia—the fact that it can exist only through the feminized labor of old snapshots and remembered songs—reminds us simultaneously that the “real history” is one of violence and poverty. The psychic urge to mourn that which we are glad to lose underwrites the apparently simple nostalgia of the image.

Contesting Spectacle

There is a recurring element in all these debates, an element that can best be defined as the status of cinematic spectacle. As we have seen, both the heritage film and more art-cinematic examples like the films of Terence Davies have been criticized for employing the beautiful image at the expense of genuine engagement with the past. This suspicion of the spectacular image is not limited to the history film but is perhaps concentrated there, since in the historical film issues of realism and representation are most visibly at stake. This connection between ethics and aesthetics fueled the debate around Holocaust dramas that in the United States focused on the somewhat visually pretty Schindler’s List (Spielberg, 1993) and in Europe resurfaced around the highly unrealistic Life Is Beautiful (Benigni, 1997).23 While some critics felt that Steven Spielberg’s black-and-white cinematography and Roberto Benigni’s stylized concentration camp debased the Shoah, others argued that realism was an impossible and undesirable goal in representing such unthinkable events. Even without such emotive topics, though, the 1980s and 1990s have been characterized by a critical opposition to visual excess that maps both a theoretical refusal of “postmodern style” and a specifically European backlash against the glossy, expensive Hollywood blockbuster with which local film cultures can never realistically compete.

Michel Chion crystallizes the European critique of postmodern spectacle in a historical taxonomy of the image that moves from the gaudy to the anti-gaudy and, finally, the neo-gaudy. Using the French cinéma du look as his prime culprit, he argues that whereas early color film emphasized color because of its novelty and a perception that it more closely depicted reality, and whereas classical film toned down color to heighten realism and to spare its use for occasional dramatic effect, postclassical neo-gaudy film returns to bright colors, now used indiscriminately and reflexively, without depth or realism.24 As the example of cinéma du look suggests, European films of the 1980s and 1990s did engage with visually rich styles, using mise-en-scène and cinematography in ways that were self-reflexive, mannered, or at the very least striking. We can trace this impetus in visually dense films such as Delicatessen (Jeunet and Caro, 1991), which uses a comic-book aesthetic to create a fantastic diegesis; in the bright colors and excessive scenarios of Almodóvar’s films, such as What Have I Done to Deserve This? (1984); and again in the narrative abstraction and digital manipulation of the image in The Pillow Book (Greenaway, 1996). However, it is clear from these examples that there can be no simple attribution of mainstream versus countercinematic or, indeed, of classical depth versus postclassical surface. Delicatessen apes the faded color palette of 1940s nostalgia, repositioned in a fantastic future in which Paris is populated by cannibals and underground-dwelling vegetarian guerrillas. Pedro Almodóvar multiplies locations of excess in the service of queer explorations of gender and Spanish national identity. And Peter Greenaway patiently deconstructs the sacred cows of British bourgeois culture, with a proliferation of significatory systems that defies any notion of the spectacular image as empty. We could even attribute a neo-gaudy style to Jean-Luc Godard’s films of the period, such as Passion (1982), or to Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colors series (Blue, 1993; White and Red, 1994). Neo-gaudy spectacle is widely visible, but it is neither politically nor aesthetically unitary.

What Have I Done to Deserve This? Neo-gaudy images are filled with excessive color and detail.

At the same time, there is a countervailing refusal of exactly these trends. Of course, European cinemas have always been largely low-budget and hence have a practical investment in what we might call an aesthetics of almost-poverty. Nonetheless, countering spectacle is not simply a matter of gritty realism: with Dogme ’95, anti-spectacular cinema became arguably the most influential European film movement of the 1990s.25 The signatories of the Dogme Vow of Chastity promised not to use special effects, to periodize, or to make genre pictures but only to shoot on location with available props and natural lighting. The manifesto states: “Today a technological storm is raging of which the result is the elevation of cosmetics to God. By using new technology anyone at any time can wash the last grains of truth away in the deadly embrace of sensation. The illusions are everything the movie can hide behind.”26 Although not entirely serious, and not entirely hewed to by its members, this manifesto demonstrates both the centrality of spectacle in any efforts to rethink European cinema and the way in which historicity has become closely connected to spectacle, even—or perhaps especially—for those who seek to oppose them both. For the members of Dogme, historicity is as much a problem for realism as spectacle, a position that makes no sense in relation to, say, classical Hollywood history films but, rather, is logical only in response to the spectacular histories of the European heritage film. While the grainy digital video (DV) of Thomas Vinterberg’s Festen (1998) produces its own visual beauty, its low-light and low-life immediacy clearly stands in a dialogic, if antagonistic, relationship with the aesthetics of la belle image.

While this cinematic and critical debate around the status of the image is grounded in European histories of representation, neither the broad critique of the spectacular image nor the notion of a return to the spectacular is limited to Europe. The question of spectacle as a style was discussed explicitly in the 1980s as part of the largely American debate on postmodernity, while a more film-historical approach has dominated recent discussions of postclassical cinema. I will return periodically to some of the conflicts arising from the postmodern debates, but for now it is sufficient to note that the Jamesonian critique of the spectacular image as empty, superficial, and affectless has been widely criticized and yet even more widely assimilated into mainstream critical discourse on the cinematic image, including that in Europe. In terms of film history, the notion of the postclassical is also originally American but has taken on a global range. What Miriam Hansen has characterized as a new cinema of attractions is evidenced in Hollywood special effects blockbusters but also, more relevantly for this project, in the visually arresting mise-en-scènes of the 1990s Asian New Waves.27 Can we draw a map of European cinema that runs through Hong Kong?

The colonial relationship has long been articulated in European cinemas (especially those among the United Kingdom, France, India, and Africa), with colonized space functioning as exotic backdrop for Western romance, adventure, and psychodrama. Spectacle, in these texts, is not empty but produces meaning in a system of visual and narrative power that is both gendered and raced.28 As Homi Bhabha suggests, however, even in these colonial narratives we can trace the structure of liminality: a staging of cultural difference that foregrounds borders, fissures, and hybrid spaces.29 The radicality of this cultural difference must be opposed to any ideologically bland notion of cultural diversity or plurality, and in this territorial and temporal instability, the writing of postcolonial identities can take place. To be sure, we can link Hong Kong cinema to Britain through their opposing perspectives on the colonial relationship, but such a move would no doubt prove problematic. We cannot once again annex Hong Kong for Europe. More productive is to reread Western theories of postclassical spectacle (the postmodern, the cinema of attractions) through the spaces and images—what Bhabha calls, in another context, the “territorial paranoia”—of colonial space.

In the same moment as post-Wall cinema, Hong Kong culture was also experiencing a uniquely punctual relationship to space and history. Ackbar Abbas claims that Hong Kong cinema in the years leading to the 1997 handover to China visually condenses the territory’s anxieties about its own disappearance. Reading not only film but also architecture and fiction, Abbas argues that Hong Kong is characterized by a “space of disappearance.”30 He claims that since Hong Kong is almost without history, and its colonial past was about to be erased, history is to be found fleetingly, in spatial relationships and missed encounters. This situation was the exact opposite of that in Europe of the 1990s, where spectacle and historical representation were easily conflated. How, then, does postclassical spectacle intersect with (colonial) histories or aesthetics with ideology?

One film that seems to address these questions is Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000), in which the vanished Hong Kong of the early 1960s is captured just at its final moment.31 The film uses aesthetically beautiful images, slow motion, excessive mise-en-scène, costumes, and lighting to construct a spectacular and nonrealist past that nonetheless stages the painful disappearance of a material place and time. The narrative is structured around romantic loss, where an ambiguous relationship develops between a man and a woman whose respective spouses are having an affair, and the ending cements this melodramatic trope of what might have been. The hero travels to Angkor Wat and whispers his secrets (presumably his pain at never having spoken his love) into a small hole in the wall of the temple. He covers it with mud, to hold in the secret, in a narrative twist that follows the “too late” structure by which Franco Moretti has characterized the affective moment in melodrama.32 Finally he speaks, after a whole narrative in which the lovers cannot take that risk. But his speech is not heard. There is a close-up of the hole, after he has left, and the image of the blades of bright green grass, still attached to the bit of earth he has stuck in the hole, brings together spectacular and narrative affect in a moment of pure loss. The temporal and spatial specificity of these blades of grass—in the wrong country, and years after the affair—bears the weight not just of this romantic loss but the loss of the Hong Kong of the 1960s and the politics of disappearance in the 1990s.

In the Mood for Love The grass-covered hole is a material signifier of loss.

Abbas does not talk about In the Mood for Love, whose release postdates that of his book by several years, but Wong’s film enables us to connect the “space of disappearance” to the postclassical structuring of the spectacular image. For Bhabha, such crises in national representation provide spaces of productive instability: using the Derridean supplement to describe the space in which “the nation’s totality is confronted with, and crossed by, a supplementary movement of writing,” he argues that “it is in this supplementary space of doubling—not plurality—where the image is presence and proxy, where the sign supplements and empties nature, that the disjunctive times of Fanon and Kristeva can be turned into the discourses of emergent cultural identities, within a non-pluralistic politics of difference.”33 In the Mood for Love suggests that we can also read this supplementary doubling cinematically. Where the spectacular image is both presence and proxy, both a signifier of and a replacement for the disappearing colonial territory, then we may be able to read spectacle also in terms of temporal disjuncture and emergent cultural identities. And this, as it turns out, it also a necessary move for Europe. Bhabha insists, following Frantz Fanon, that a postcolonial reading of textual strategies not only forms an Other space from which to read anticolonial work but also demands a reconceptualization of Western theories and of European spaces. He trenchantly asks: “Does the language of culture’s ‘occult instability’ have a relevance outside the situation of anti-colonial struggle? Does the incommensurable act of living—so often dismissed as ethical or empirical—have its own ambivalent narrative, its own history of theory? Can it change the way we identify the symbolic structure of the Western nation?”34 Repositioning postclassical spectacle through contemporary Hong Kong film suggests that the cinematic destabilizing of colonial space may also destabilize European theories of political space, history, and the spectacular image.

Historical Loss

Several of the films I have discussed—including In the Mood for Love; Distant Voices, Still Lives; and Land and Freedom—share another discursive pattern: a narrative of loss forms their primary mode of engagement with the historical past. As Elsaesser argues, loss and nostalgia can be considered constitutive of cinematic temporality, but the longue durée of modern subjectivity is nonetheless subject to locally specific articulations. For Hong Kong, the disappearance of colonial identity and the return to China provoke anxiety, while in Europe in the 1990s, we find other sorts of disappearance, other ghostly returns. For historian Mark Mazower, late-twentieth-century Europe is characterized by a “sense of fin de siècle disorientation,” a problem that “reflects the specific historical experience of Europe this century, and the carnage that followed its once-fervent faith in utopias.”35 This formulation implies a European subjectivity confused by history, disenchanted—a Europe at a loss perhaps, but far from suffering from nostalgia for carnage. Mazower is correct in his assessment—it is apparent that we must situate the post-Wall continent in relation to the violent histories of Nazism and Communism—and yet there is an experience of loss to be found within this process of disenchantment.

We can locate the emergence of this discourse of loss first in the immediate crisis that the fall of the Wall prompted for the European Left, in which the triumphalism of the West German Right in 1989 (and the rightist Christian Democratic Party’s victory in the East in 1990) seemed to presage an inevitable obsolescence of European socialism. In Germany, the reunification debate produced a broad range of opinion, from the East German dissident socialists’ desire to create democratic socialism in a reimagined German Democratic Republic (GDR) to the conservative—and ultimately victorious—view that the GDR should be assimilated into the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) with as little ceremony as possible. From many leftist writers, though, came the fear, articulated by Peter Schneider, that the Right was right after all.36 Celebrations of the democratic revolution entailed a trickier positioning for those who did not want to subscribe either to a telos of capitalist triumph or to straightforward apologism. The problems of the German intellectuals and leftist politicians (East and West) quickly became the problems of progressive European discourse in general. Žižek’s question—“Is it possible to imagine a leftist appropriation of the European political legacy?”—defines the dilemma of the European Left not simply as a matter of politics but fundamentally as a question of how to read history.

As European identities were thrown into flux in 1989, it became pressing to consider the histories that had led to this point. In precisely this moment it became possible, and indeed imperative, for European cultures to look back at the history of the postwar system and for the Left to stage that look in terms of loss. The history at stake in this narrative of loss and disenchantment, I will argue, centers on the immediate postwar years in Europe, from 1945 to 1948. Whereas the art cinema of the 1960s and 1970s began to reexamine the war years (most significantly in Germany, Italy, and France) in the wake of 1989, the period immediately following the war came under reconsideration. The political crisis caused by the sudden reintegration of East and West was also a moment of potential for change: to reimagine both national and supranational identities. And the desire to move on from the Cold War era and to imagine the end of this historical period was played out cinematically in a need to rethink the history of its beginnings.

For the Left, the question of 1945 to 1948 was: What went wrong? This question is formed differently across the continent, for things went wrong in a multitude of ways. The most significant difference, of course, is that of Western and Eastern Europe, in which the West experienced a rapid return to a conservative hegemony, while the East wrestled with supposed socialist states that rapidly repressed their populations and marginalized those who fought for democratic socialism. And while these two sets of dissidence frequently seemed to have little to say to each other, the situation in Germany in 1989 proved their positions closer than one might have thought during the years of partition. In the brief period of optimism before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall, socialists on both sides imagined the “Third Way,” which would take the best from both systems. The rapidity with which this vision collapsed under the weight of East German desire for freedom and West German economic pressure found both Lefts together again, once more plucking defeat from the jaws of victory.

Thus, for history films in the early 1990s what is important is not so much the reconsideration of a historical moment in and for itself but the implications of that history for the present. While New German Cinema forced a public acknowledgement of Nazism that was, one could argue, long overdue, the films I will be analyzing are more concerned with the relationship between 1945 and 1989. In Italy, for example, 1945 was a moment of optimism, in which a leftist coalition was on the point of creating a new Italian republic. Then, in the 1990s, the collapse of the First Republic demanded a reevaluation of its inception. For the former Communist countries, 1945 was, of course, the moment before the institution of the Soviet bloc and, correspondingly, the last point at which a discourse of European-ness was possible. This is why Žižek wants to rehabilitate some version of Eurocentrism for the new Europe, insofar as this notion of continental identity is exactly what had not been possible for the fifty years of partition. For the cinema of the early 1990s, it therefore becomes crucial to assert a new set of relationships to the national and European past. Not all these films should necessarily be thought of as leftist texts per se, but all are engaged with these ideological shifts, their implications for various European spaces, and the question of how this present can be related to the postwar past.

The chapters that follow do not attempt an overview of contemporary historical films; rather, they consist of a series of detailed case studies, focusing on one film or a group of related films in a particular country. There are various reasons for this approach: first, far too many films were made across Europe in the 1990s for any kind of overview to make critical sense; second, since this project is not analyzing a preexisting genre or national cinema, the idea of a coherent and numerically significant body of related texts is less central than a concern for the specific work of each film; third, and perhaps most important, the arguments that I will be making require a depth and breadth of textual analysis that can occur only in the context of such lengthy case studies. Both methodologically and theoretically, I will be making a claim for the place of textual analysis in film theory and history. In order to discuss adequately the complex interrelations of history, loss, and the cinematic image, close attention must be paid to textual elaborations of space, time, and spectacle. Only by analyzing formal discourses of mise-en-scène, editing, and narrative structure can we tease out the stakes of an anti-anti-Eurocentric textuality.

The films do share certain crucial elements, however. All were made in the late 1980s to the mid-1990s, and all narrate European histories in or from the mid-1940s. History films of a sort, these texts nonetheless circulated not as generically historical but more as art cinema. Most obviously, what these films have in common is their doubled historical locations, for all were made around 1989, and all tell stories about the end of World War II and the beginning of the divided Europe. And, although formally diverse, these films share a mode of textualizing these histories by elaborating connections between cinematic and geopolitical spaces and between past and present temporalities. This process of textualization is central to our discussion, for the status of the film text is not merely that of historical or theoretical example. My aim is to coarticulate film theory with history, and in doing this the role of textual analysis is of central importance. In these contemporary European films, the staging of history and space is enabled by particular mobilizations of the cinematic image, most readily summed up in the (nonetheless ambiguous) idea of spectacle.

The point of bringing together these films is not so much to outline a new genre as to tease out a moment, a way in which film intervenes in the production of historical and political meaning. The histories at stake are primarily political, but, like Elsaesser, I am just as interested in film histories or, rather, the histories of cinema. The historical moments in which the films were made, and those represented textually, correspond to worldwide shifts in modes of production, as well as to changes in various European cinematic forms. Thus, any investigation of the textual staging of history has to take into account both the history of Europe and the cinematic history within which the films are made. These, however, are not so separate and cannot be neatly categorized as antinomies of text and context. Rather, the film histories of both the postwar moment in which the films are set and the post–Cold War moment of their production become a part of the films’ elaboration of historical space.

Chapter 2 considers a group of Italian films that were made in the years immediately before and after the dramatic fall of the Italian First Republic in 1991. Fitting relatively smoothly into the category of heritage film, Cinema Paradiso, Mediterraneo (Salvatores, 1991), and Il Postino (Radford, 1994) form a series: all romantic melodramas, all focusing on the lives of young men, and all narrativizing the years immediately after World War II in Italy. These films would appear to fit into the notion of la belle image, centered as they are on beautiful landscapes within which their historical romances take place. However, I argue that both the national image and the melodramatic narratives of these films subtend a politically potent engagement with a specific national history. This chapter examines the uses of the beautiful landscape image in relation to theories of mourning, melodrama, and historical loss. It also considers questions that will prove recurrent around the heritage film, nostalgia, and indexicality; it reads the spectacular image through theories of cinematic specificity but also through Walter Benjamin’s concept of the dialectical image.

Chapter 3 begins to shift the critical terrain to that of the continent as a whole, considering the effects of 1989 on political and cultural definitions of Europe. It discusses the cartography of the new Europe, examining how films from several countries produce cinematic maps. Beginning with an analysis of how visual theories have taken up a discourse of cartography, this chapter explores filmic tropes of geopolitical space from the city and the nation to more difficult in-between spaces such as the border. In parts of Europe like the Balkans and Germany, the space engendered is not beautiful but complex, limited, or impossible. In addition, this chapter moves from heritage films to art cinema (by no means a clear generic leap) and outlines the contemporaneous debates around post-Wall art film.

Chapter 4 analyzes Underground (Kusturica, 1995), locating this controversial film within theoretical debates on Balkanism, in which Western representations of the Balkans are situated within an epistemological structure similar to that of Edward Said’s notion of Orientalism. Kusturica has frequently been attacked for presenting stereotypical images of Serbian, Croatian, and Bosnian characters, but this analysis focuses less on ethnic “images of” criticism and more on questions of enunciation and address. It asks: Can a Balkan film speak? and How can we read the iteration of Balkanist tropes in a Balkan film? While Yugoslav and post-Yugoslav film is usually read within a straightforward, if highly charged, ideological discourse, this chapter articulates national space with a textual logic of melancholia and with a film history of Yugoslav neorealism. The question of representing the 1940s, I suggest, is also thinkable in terms of cinematic histories of the nation. In this chapter, the spaces under consideration are not the beautiful landscapes of the Italian films but the mise-en-scène of the cellar and the impossible space of Europe, as seen from the abjected and denationalized space of Yugoslavia.

Chapter 5 focuses on Zentropa (von Trier, 1991), a film that addresses postwar German space, looking back to the zoned postwar Germany, but that also demands an international perspective in extratextual terms. Zentropa is not simply a coproduction but a coproduction that narrates a history of another country. While Germany is one of the film’s coproduction partners, the film is also French, Danish, and Swedish and is most often considered in relation to its Danish director. Moreover, Zentropa reflexively repeats a history of international representation on the German ruins: this chapter situates Zentropa in terms of the history of the Trümmerfilm (ruin film), as well as in the context of German and international cinema’s response to Germany’s place in the postwar European order. Zentropa is an unusual text—a film about nation that is almost impossible to categorize in national terms. Eschewing conventional discourses of national cinema, my analysis interrogates the film’s construction of cinematic space through a generic history of monstrosity, femininity, and dark European spaces, articulating its referentiality through questions of film noir, horror, and the feminine, European monster. It also relates this cultural history of German/European monstrosity to the film’s formal technique of back projection, considering how projection becomes a mode of articulating—and disarticulating—political spaces.

In each of these case studies, cinematic form provides the basis for an analysis that seeks to think both historically and theoretically about the staging of history and demands that the relationship between spectacle and ideology in contemporary cinema be closely examined. If we are to attend to the subtle vocalities of post-Wall European cultures, to read outside overtly political narrative interventions or supranational film policy, it becomes necessary to reestablish the centrality of the film text. This is not a formalist position—quite the opposite. Rather, if European cinema studies is to move beyond a bland historicality, close attention to textual work is the best way to reconcile the demands of poststructural theory and film history. If an anti-anti-Eurocentrist cinema is possible, we must map its borders, its contradictions, and its appearances in the European film text.