Chapter 9

The Fractional Meta-Trigonometry

In the previous four chapters, fractional generalizations of the integer-order trigonometric and hyperbolic functions have been developed. In Chapters 5 and 6, we have seen the relationship of the R1-trigonometry to the R1-hyperboletry. Such a direct relationship for the R2-trigonometry, however, has not been found. After some study of this problem, it has become apparent that more complicated relationships exist between the bases for the various trigonometries. This chapter presents a generalization that helps explore these connections. Furthermore, the chapter contains the hyperboletry1 and all1 of the trigonometries that we have explored to this point. This chapter also presents new trigonometries (Lorenzo [82, 83]) not previously available and potentially allows the solution of linear fractional differential equations in terms of these special functions. The result then is the master fractional trigonometry based on the R-function.

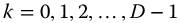

The bases of the trigonoboletries that we have considered to this point are as follows:

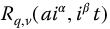

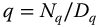

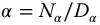

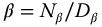

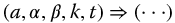

Clearly, trigonometries can be created for, or associated with, all of the indexed forms of the R-function presented in Table 3.2, which is a total of 16 integer-valued bases. Many of these bases will likely have important application in the fractional calculus and in the solution of fractional differential equations. However, a more global approach is considered here. This chapter considers fractional meta-trigonometries based on

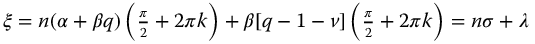

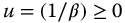

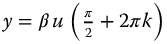

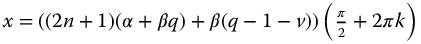

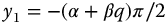

With  and

and  ranging between 0 and 4, all of the integer-valued bases are considered together with infinitely more noninteger possibilities.

ranging between 0 and 4, all of the integer-valued bases are considered together with infinitely more noninteger possibilities.

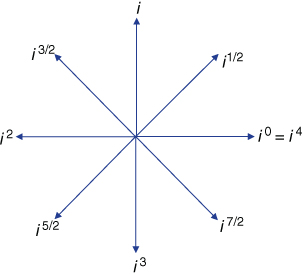

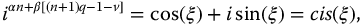

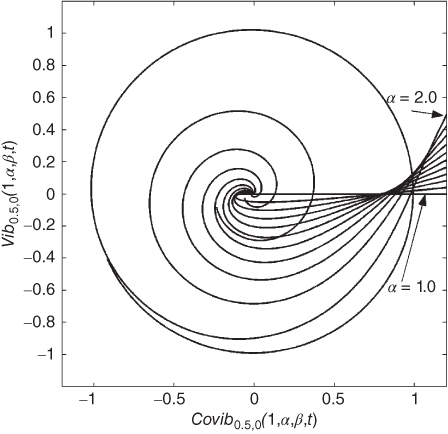

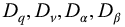

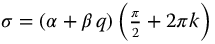

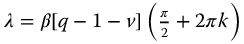

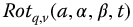

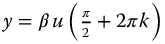

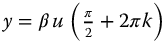

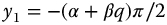

Multiplication of the a or t variables by  rotates the variable in the complex plane by the amount

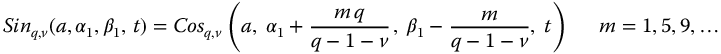

rotates the variable in the complex plane by the amount  radians. This is shown graphically in Figure 9.1. These rotations can have profound effects on the real and imaginary projections, which relate to the generalized functions. This chapter is adapted from Lorenzo [82, 83], with permission of ASME.

radians. This is shown graphically in Figure 9.1. These rotations can have profound effects on the real and imaginary projections, which relate to the generalized functions. This chapter is adapted from Lorenzo [82, 83], with permission of ASME.

Figure 9.1 Graphical display of  for

for  in steps of

in steps of  .

.

Source: Lorenzo 2009a [82]. Reproduced with permission of ASME.

9.1 The Fractional Meta-Trigonometric Functions: Based on Complexity

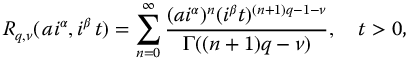

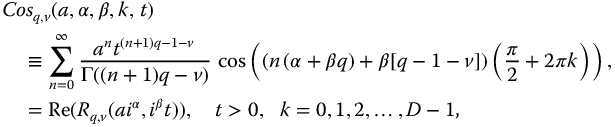

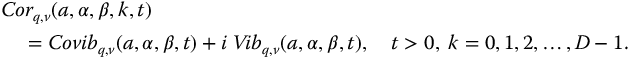

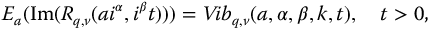

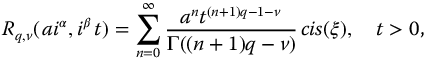

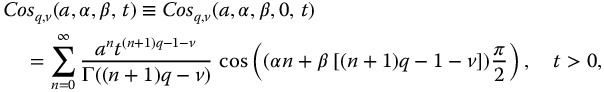

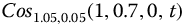

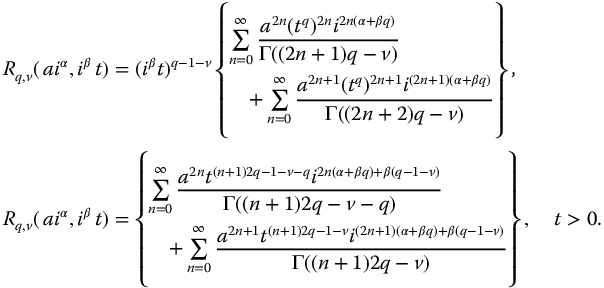

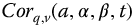

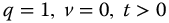

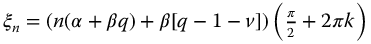

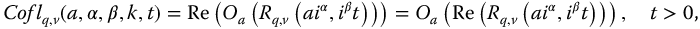

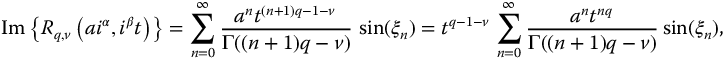

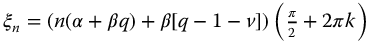

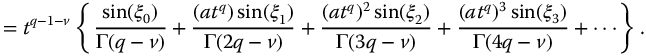

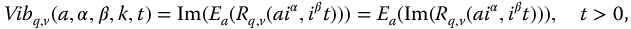

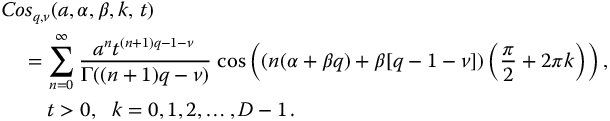

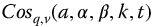

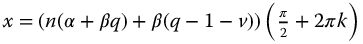

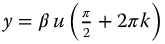

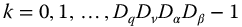

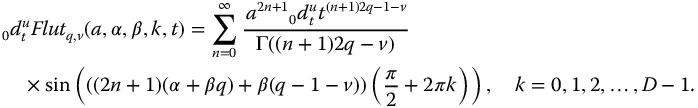

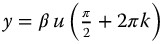

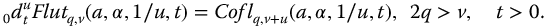

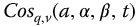

We start by separating  into real and imaginary parts. Thus, we consider

into real and imaginary parts. Thus, we consider

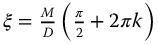

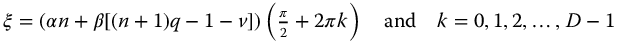

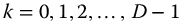

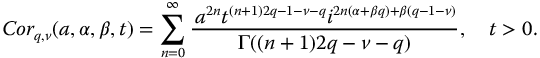

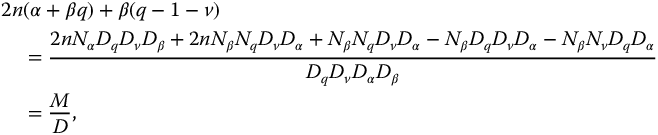

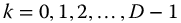

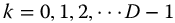

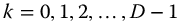

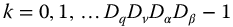

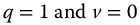

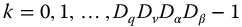

Now, for rational q, v,  , and

, and  , we may write

, we may write

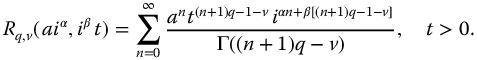

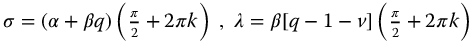

where  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . Then, we may write

. Then, we may write

where  or

or  and

and  , and M/D is rational and in minimal form.

, and M/D is rational and in minimal form.

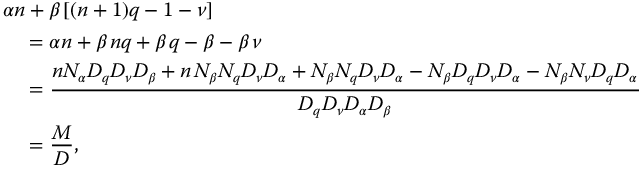

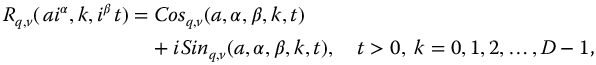

Therefore, equation (9.2) may be written as

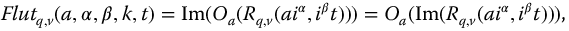

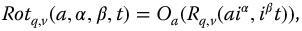

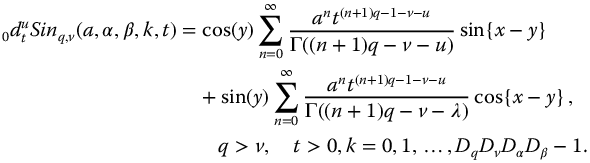

where k is included in the R-function argument to reflect its presence in  on the right-hand side. Then, similar to the earlier definitions, we define the generalized fractional functions as

on the right-hand side. Then, similar to the earlier definitions, we define the generalized fractional functions as

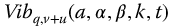

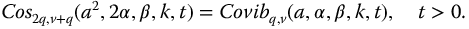

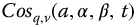

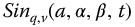

These definitions generalize those for the trignoboletries that were developed in previous chapters. The notation is changed, and here drops the preceding R and its subscript. These fractional meta-trigonometric functions are discriminated from the traditional trigonometric functions by the capitalization and the subscripted order variables. Continuing from Ref. [82] with permission of ASME:

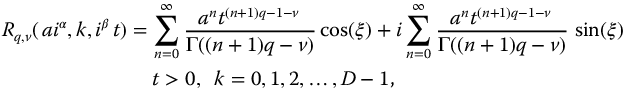

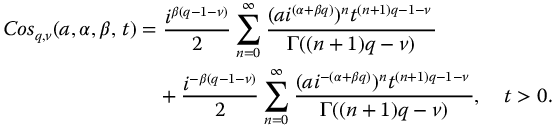

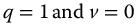

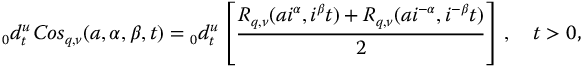

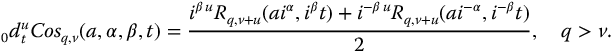

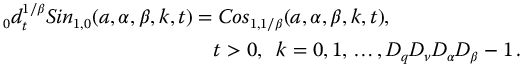

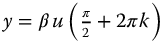

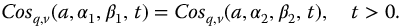

As with the previous trigonometric functions, we define the principal functions for t > 0 as

where D is the product of the denominators of  in minimal form. This is the generalized fractional Euler equation. A complimentary fractional meta-Euler equation is derived later as equation (9.173).

in minimal form. This is the generalized fractional Euler equation. A complimentary fractional meta-Euler equation is derived later as equation (9.173).

9.1.1 Alternate Forms

It should be noted that the form of equation (9.1) was chosen for the convenience that it allowed either the “a” and/or the “t” variables to be made complex. The cost of this convenience, however, was to introduce two new variables,  , into the defining summation. Complexly proportional forms with one less variable in the summation are possible and are discussed in Appendix E.

, into the defining summation. Complexly proportional forms with one less variable in the summation are possible and are discussed in Appendix E.

9.1.2 Graphical Presentation – Complexity Functions

A complete graphical presentation for the  - and

- and  -functions is, of course, impossible. There are seven parameters and variables, and the possible number of charts is limitless. In previous chapters, the effects of variations of q and v have been presented with

-functions is, of course, impossible. There are seven parameters and variables, and the possible number of charts is limitless. In previous chapters, the effects of variations of q and v have been presented with  and

and  values of zero and one. Therefore, the emphasis here is on the new variables introduced in this chapter, namely

values of zero and one. Therefore, the emphasis here is on the new variables introduced in this chapter, namely  and

and  .

.

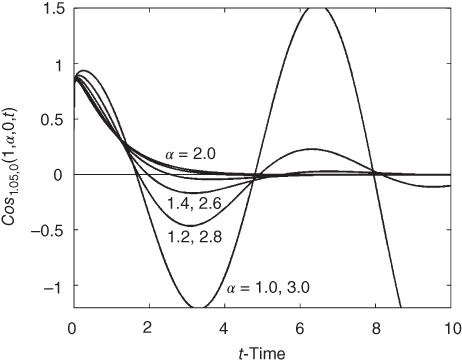

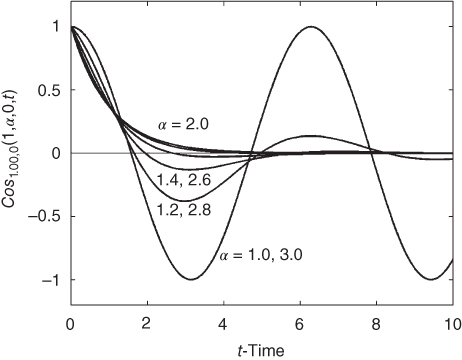

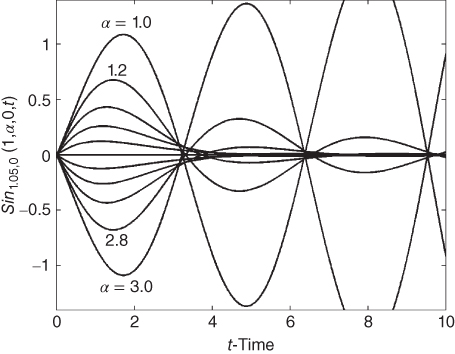

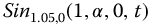

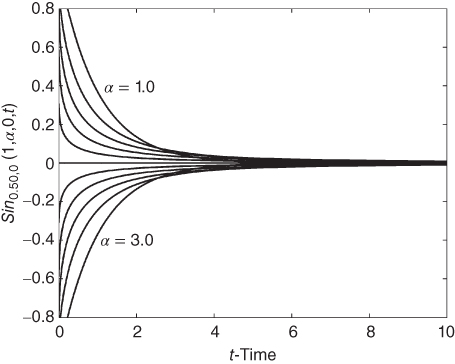

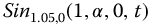

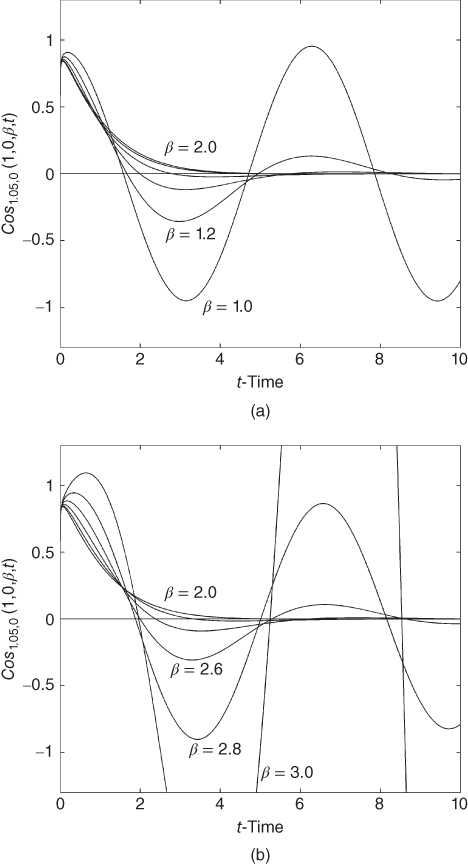

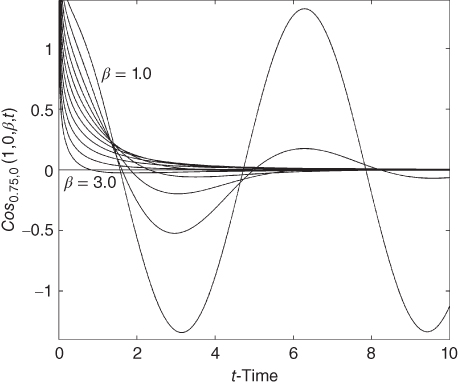

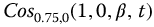

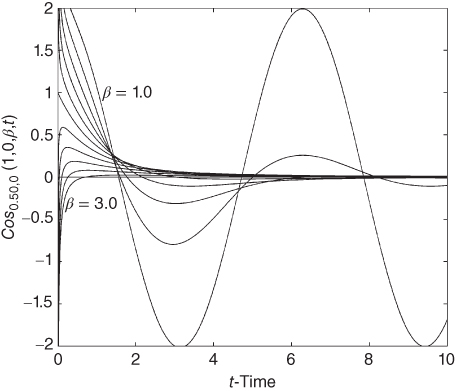

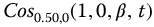

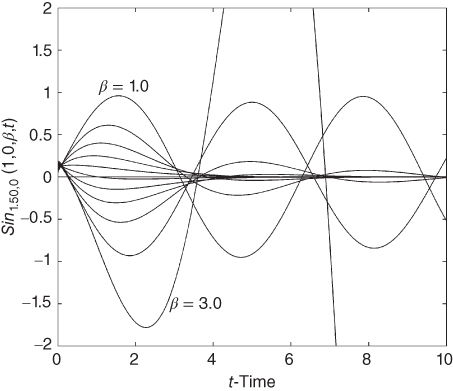

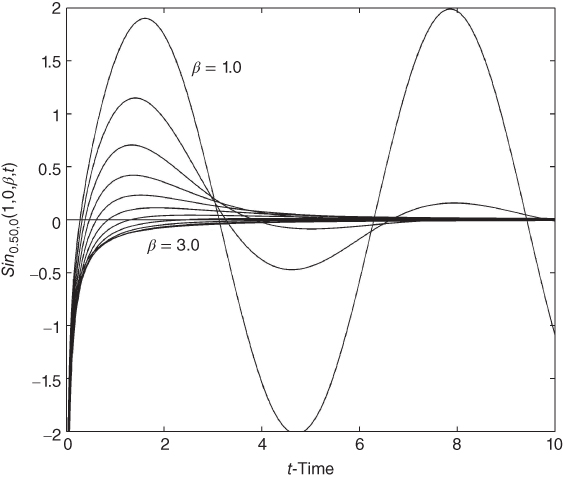

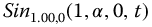

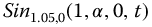

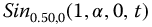

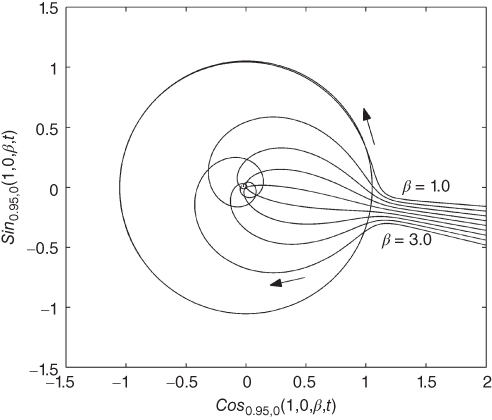

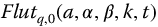

Figures 9.2–9.5 show the effect of varying  in the

in the  for q = 1.05, 1.00, 0.75, and 0.50, with a = 1.0,

for q = 1.05, 1.00, 0.75, and 0.50, with a = 1.0,  , and with

, and with  variations from 1.0 to 3.0. For the

variations from 1.0 to 3.0. For the  -function in Figure 9.3, we see that

-function in Figure 9.3, we see that  over the range shown.

over the range shown.

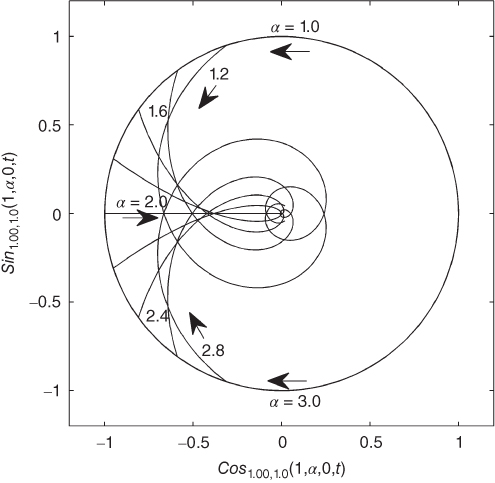

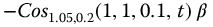

Figure 9.2 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.05, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.05, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

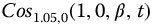

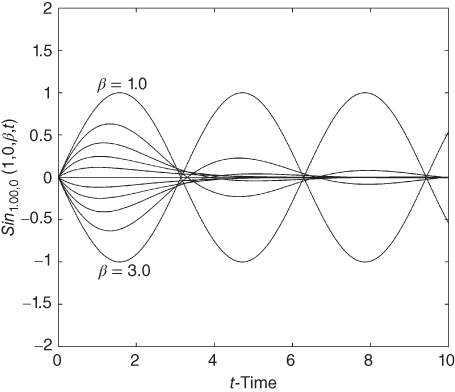

Figure 9.3 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.00, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.00, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

Source: Lorenzo 2009a [82]. Adapted with permission of ASME.

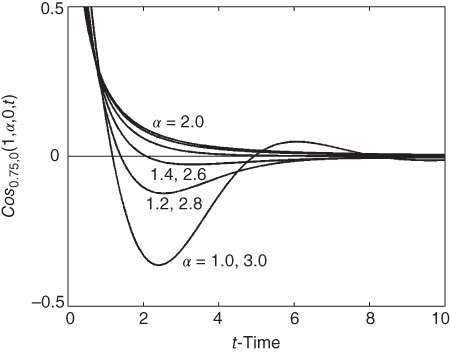

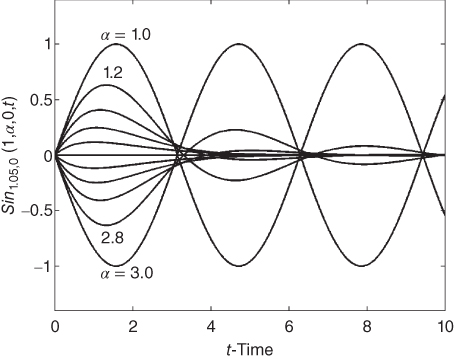

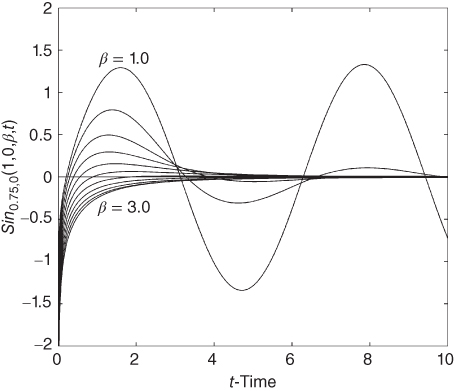

Figure 9.4 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.75, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.75, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

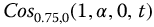

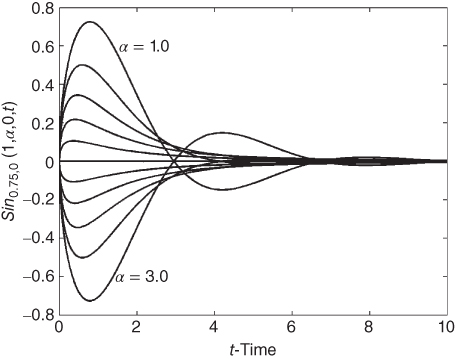

Figure 9.5 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.25, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.25, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

The study is repeated for  in Figures 9.6–9.9. For the

in Figures 9.6–9.9. For the  -functions, in these figures, it can be seen that the behavior is symmetric around

-functions, in these figures, it can be seen that the behavior is symmetric around  ; that is,

; that is,  for

for  .

.

Figure 9.6 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.05, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.05, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

Figure 9.7 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.00, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.00, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

Source: Lorenzo 2009a [82]. Adapted with permission of ASME.

Figure 9.8 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.75, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.75, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

Figure 9.9 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.50, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.50, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

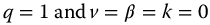

In Figure 9.7, the fractional trigonometric functions appear to be quite similar to exponentially damped sinusoids or cosinusoids. The common feature of these figures is the selection of variables, that is,  . Continuing from Ref. [84] with permission of ASME:

. Continuing from Ref. [84] with permission of ASME:

Relative to Figure 9.7, we have from equation (9.7)

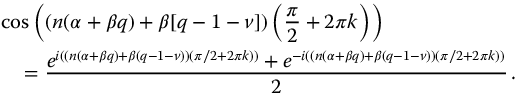

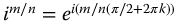

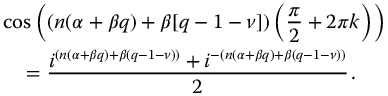

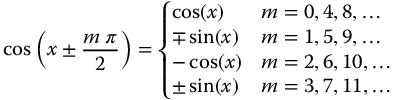

Now, from Ref. [56], pp. 118–119, #632,

Thus,

a closed-form summation. Also, based on Ref. [56], pp. 116–117, #631, we can determine

Because

is simply a constant for any individual curve, we see that for these special cases the functions are indeed exponentially damped sinusoids under the

constraints.

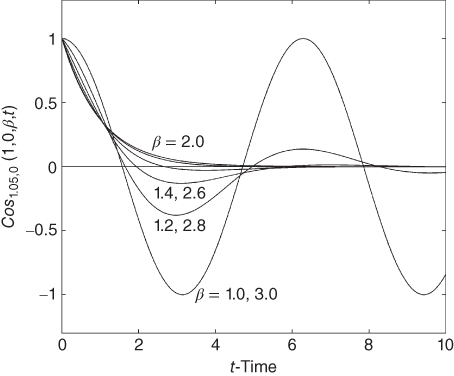

The effects of variations in

on

with

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, is shown in Figures 9.10a–9.13. Symmetry around

, similar to that observed for the

variations, is seen in Figure 9.11 for

. The effect of

variations on the fractional

-functions is presented in Figures 9.14–9.17. For values of q < 1, an increase in

increases the apparent damping as seen in Figures 9.16 and 9.17.

Figure 9.10 Effect of  on

on  with (a)

with (a)  = 1.0–2.0 and (b)

= 1.0–2.0 and (b)  = 2.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.05, a = 1,

= 2.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.05, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

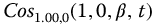

Figure 9.11 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.00, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.00, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

Figure 9.12 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.75, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.75, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

Figure 9.13 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.50, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.50, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

Figure 9.14 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.05, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.05, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

Figure 9.15 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.05, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 1.05, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

Figure 9.16 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.75, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.75, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

Figure 9.17 Effect of  on

on  with

with  = 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.50, a = 1,

= 1.0–3.0 in steps of 0.2, with q = 0.50, a = 1,  , v = 0, k = 0.

, v = 0, k = 0.

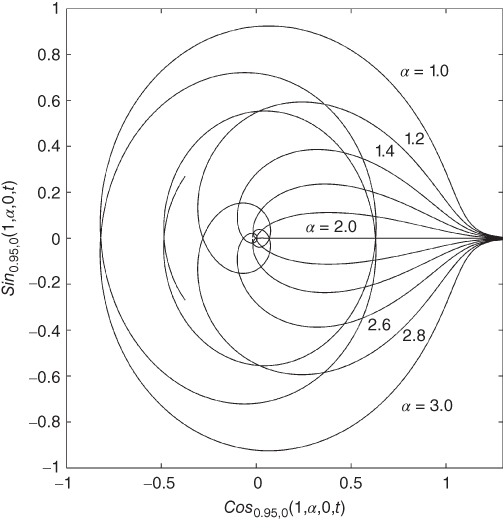

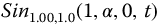

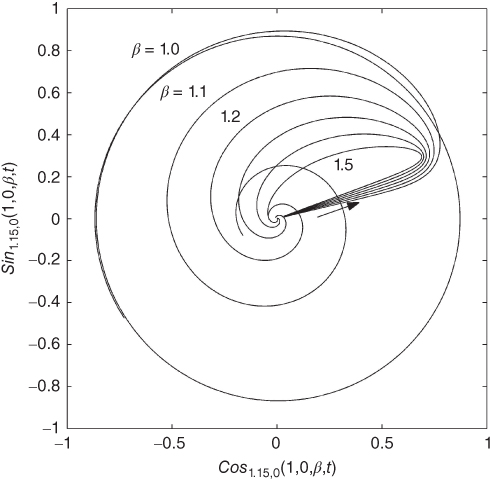

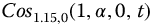

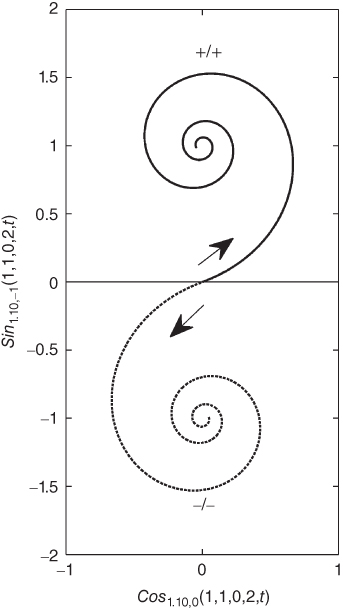

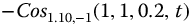

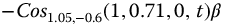

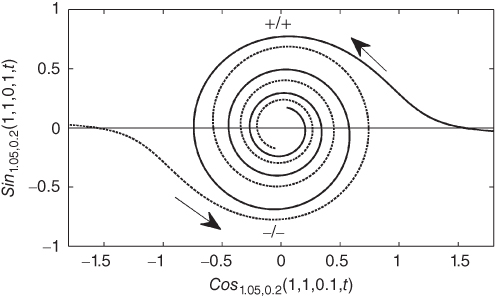

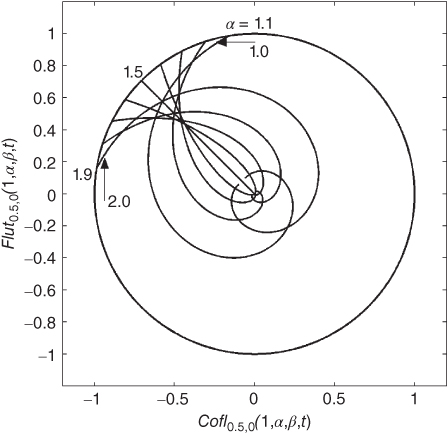

Phase plane plots of Figures 9.18–9.21 study the effects of variations in  for values of q = 1.05, 1.00, 0.95, and 0.50. A significant change in the nature of these cross plots is seen with small variations of q around q = 1.0 in Figures 9.18–9.20. We notice in Figure 9.21 the loss of oscillation due to the small value of q.

for values of q = 1.05, 1.00, 0.95, and 0.50. A significant change in the nature of these cross plots is seen with small variations of q around q = 1.0 in Figures 9.18–9.20. We notice in Figure 9.21 the loss of oscillation due to the small value of q.

Figure 9.18 Phase plane  versus

versus  for

for  = 1–3 in steps of 0.2, with a = 1.0, q = 1.00,

= 1–3 in steps of 0.2, with a = 1.0, q = 1.00,  , k = 0, v = 0. Arrows indicate increasing function.

, k = 0, v = 0. Arrows indicate increasing function.

Source: Lorenzo 2009a [82]. Adapted with permission of ASME.

Figure 9.19 Phase plane  versus

versus  for

for  = 1–3 in steps of 0.2, with a = 1.0, q = 1.05, k = 0,

= 1–3 in steps of 0.2, with a = 1.0, q = 1.05, k = 0,  , v = 0. Arrows indicate increasing function parameter.

, v = 0. Arrows indicate increasing function parameter.

Figure 9.20 Phase plane  versus

versus  for

for  = 1–3 in steps of 0.2, with a = 1.0, q = 0.95, k = 0,

= 1–3 in steps of 0.2, with a = 1.0, q = 0.95, k = 0,  , v = 0.

, v = 0.

Figure 9.21 Phase plane  versus

versus  for

for  = 1–3 in steps of 0.2, with a = 1.0, q = 0.50, k = 0,

= 1–3 in steps of 0.2, with a = 1.0, q = 0.50, k = 0,  , v = 0. Arrows indicate increasing function parameter.

, v = 0. Arrows indicate increasing function parameter.

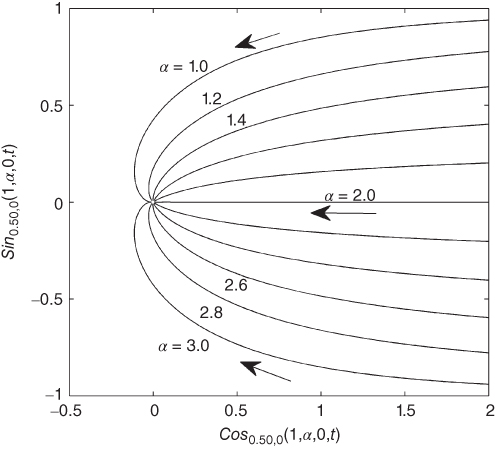

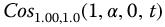

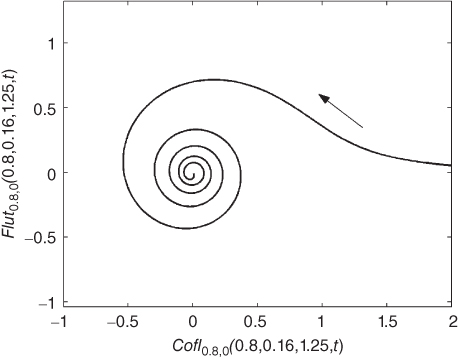

Figures 9.22 and 9.23 show the effect of  on the phase plane behavior of

on the phase plane behavior of  versus

versus  with q = 1,

with q = 1,  , a = 1, and k = 0. By comparing these two figures, the effect of v,

, a = 1, and k = 0. By comparing these two figures, the effect of v,  , is seen to have a strong effect on the function behavior.

, is seen to have a strong effect on the function behavior.

Figure 9.22 Phase plane  versus

versus  for

for  = 1–3 in steps of 0.2, with v = 1.0, a = 1.0, q = 1.00, k = 0,

= 1–3 in steps of 0.2, with v = 1.0, a = 1.0, q = 1.00, k = 0,  . Arrows indicate increasing function parameter.

. Arrows indicate increasing function parameter.

Source: Lorenzo 2009a [82]. Adapted with permission of ASME.

Figure 9.23 Phase plane  versus

versus  for

for  = 1–3 in steps of 0.2, with v = −1.0, a = 1.0, q = 1.00, k = 0,

= 1–3 in steps of 0.2, with v = −1.0, a = 1.0, q = 1.00, k = 0,  .

.

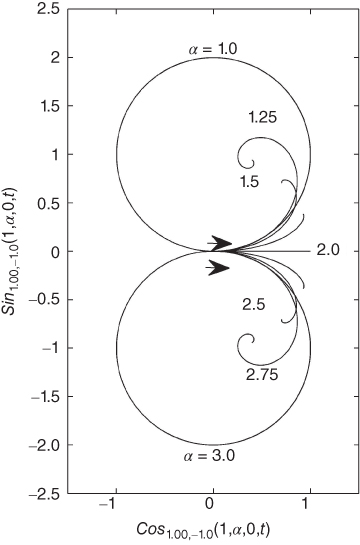

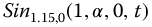

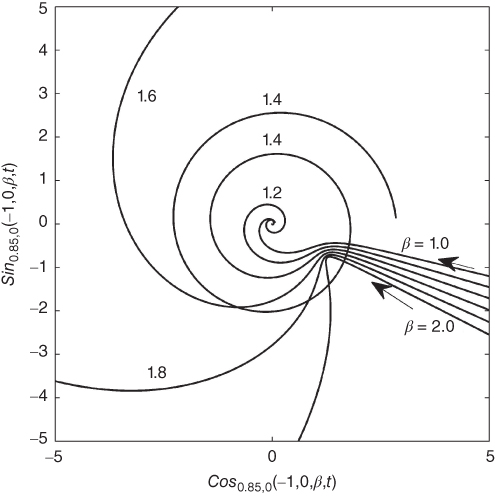

Figures 9.24 and 9.25 show the effect of  on the fractional

on the fractional  for q = 1.15 and q = 0.95. Note, for q > 1 the functions depart from the origin and for q < 1 the functions arrive from infinity. Figure 9.26 shows the phase plane,

for q = 1.15 and q = 0.95. Note, for q > 1 the functions depart from the origin and for q < 1 the functions arrive from infinity. Figure 9.26 shows the phase plane,  versus

versus  , for

, for  . Here, all the functions arrive from infinity with increasing t. However, for

. Here, all the functions arrive from infinity with increasing t. However, for  the functions are captured by the origin, while for

the functions are captured by the origin, while for  the functions are repelled by the unit circle.

the functions are repelled by the unit circle.

Figure 9.24 Phase plane  versus

versus  for

for  = 1–1.5 in steps of 0.1, with q = 1.15, v = 0, a = 1.0, k = 0,

= 1–1.5 in steps of 0.1, with q = 1.15, v = 0, a = 1.0, k = 0,  .

.

Figure 9.25 Phase plane  versus

versus  for

for  = 1–3 in steps of 0.25, with q = 0.95, v = 0, a = 1.0, k = 0,

= 1–3 in steps of 0.25, with q = 0.95, v = 0, a = 1.0, k = 0,  .

.

Figure 9.26 Phase plane  versus

versus  for

for  = 1–2 in steps of 0.2, with a = −1.0, q = 0.85, v = 0, k = 0,

= 1–2 in steps of 0.2, with a = −1.0, q = 0.85, v = 0, k = 0,  , t = 0–12.

, t = 0–12.

Because of symmetrical occurrences in some physical processes, Figures 9.27–9.31 present the  - versus

- versus  -functions together with their symmetric partners

-functions together with their symmetric partners  versus

versus  . Figure 9.31 shows an instance of a barred spiral. Such spirals are of interest in astrophysics; see Chapter 18. The various other special cases are self-explanatory.

. Figure 9.31 shows an instance of a barred spiral. Such spirals are of interest in astrophysics; see Chapter 18. The various other special cases are self-explanatory.

Figure 9.27 Phase plane  versus

versus  and

and  versus

versus  for

for  = 0.2, with a = 1.0, q = 1.10, v = −1, k = 0,

= 0.2, with a = 1.0, q = 1.10, v = −1, k = 0,  , t = 0–18.

, t = 0–18.

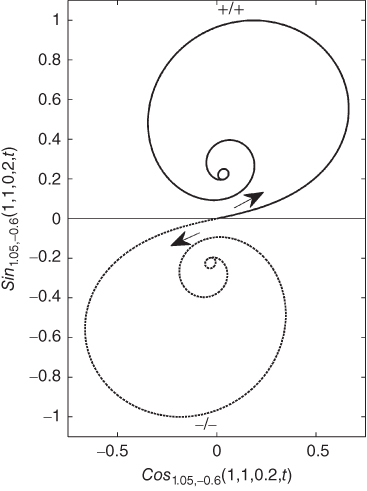

Figure 9.28 Phase plane  versus

versus  and for

and for  versus

versus  = 0, with a = 1.0, q = 1.05, v = 0.2, k = 0,

= 0, with a = 1.0, q = 1.05, v = 0.2, k = 0,  , t = 0–20.

, t = 0–20.

Figure 9.29 Phase plane  versus

versus  and for

and for  versus

versus  ,

,  = 0.1, with a = 1.0, q = 1.05, v = 0, k = 0,

= 0.1, with a = 1.0, q = 1.05, v = 0, k = 0,  , t = 0–20.

, t = 0–20.

Figure 9.30 Phase plane  versus

versus  and for

and for  versus

versus  = 0.1, with a = 1.0, q = 1.05, v = 0.2, k = 0,

= 0.1, with a = 1.0, q = 1.05, v = 0.2, k = 0,  , t = 0–20.

, t = 0–20.

Figure 9.31 Phase plane  versus

versus  and for

and for  versus

versus  ,

,  = 0, with a = 1.0, q = 1.05, v = 0.05, k = 0,

= 0, with a = 1.0, q = 1.05, v = 0.05, k = 0,  , t = 0–10.

, t = 0–10.

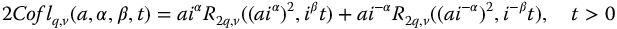

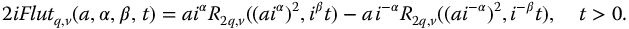

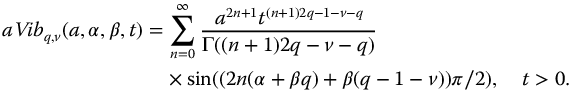

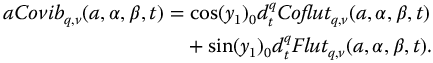

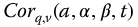

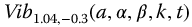

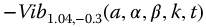

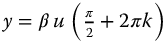

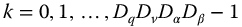

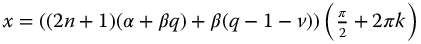

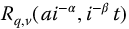

9.2 The Meta-Fractional Trigonometric Functions: Based on Parity

Continuing from Ref. [82] with permission of ASME:

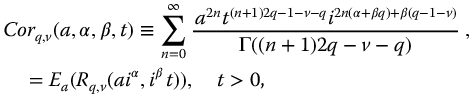

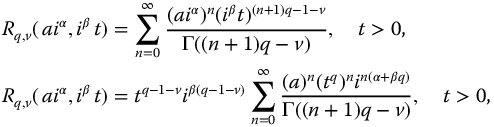

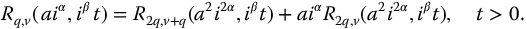

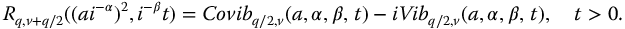

We now consider

based on parity of the exponent of a. Then, equation (9.1) is written as

The summation becomes

9.17

Forming two summations by separating the even and odd powers of a, we have

This also may be expressed as

9.20

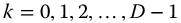

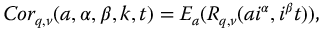

The summations of equation (9.19) contain the even and odd powers of a, respectively. In parallel with the previous development of the R-trigonometric functions, we define the generalized or meta-Corotation and Rotation functions as

where the nomenclature  means the terms with even powers of a in

means the terms with even powers of a in  .

.

Similarly,

and where the nomenclature  means the terms with odd powers of a in

means the terms with odd powers of a in  .

.

As in the previous trigonometries, the generalized Corotation and Rotation functions are also, in general, complex. Clearly, we may also write

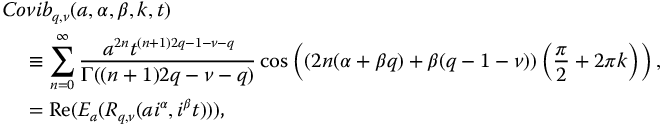

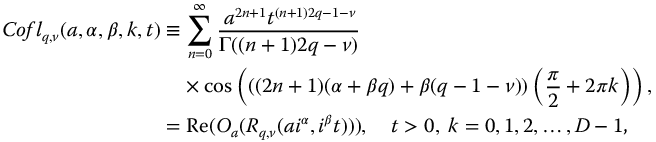

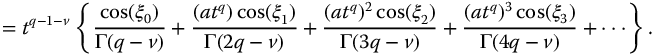

The real and imaginary parts of these functions are now used to define the four new real fractional meta-trigonometric functions. The

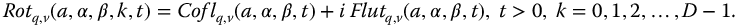

-function is given in equation (9.21) as

Now, applying equation (3.123) to

with

rational, we have

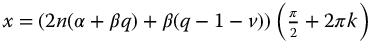

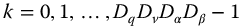

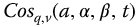

with M/D a rational number in minimal form. Thus, the  may be written as

may be written as

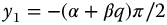

where  . The real part of the

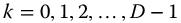

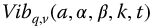

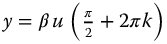

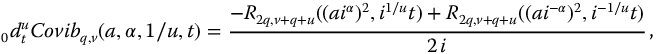

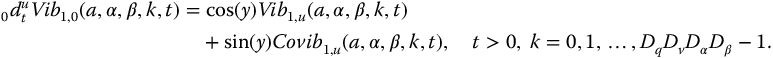

. The real part of the  is now defined as the generalized or meta-Covibration function

is now defined as the generalized or meta-Covibration function

with t > 0, and  .

.

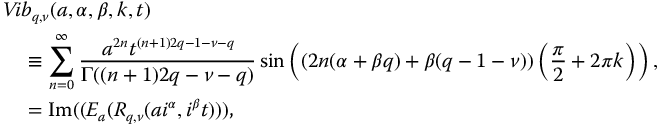

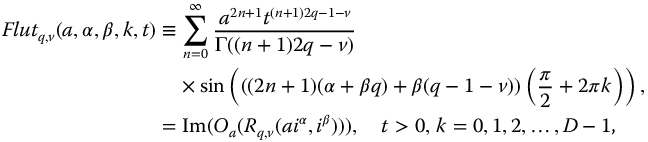

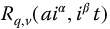

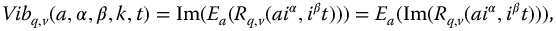

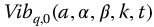

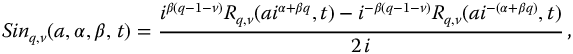

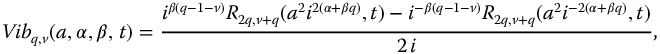

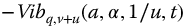

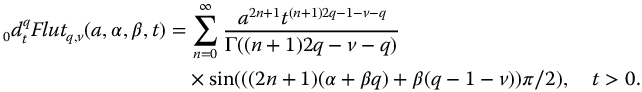

The meta-Vibration function,

, is defined as the imaginary part of the

-function; thus,

with t > 0, and  . Then, we have

. Then, we have

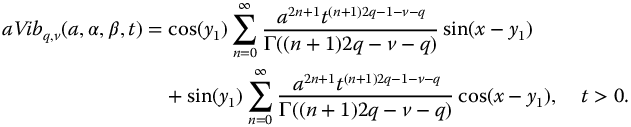

The generalized or meta-Rotation function similarly defines two new functions based on its real and imaginary parts; these are the meta-Flutter and meta-Coflutter functions, that is,

and

and where  is the product of the denominators

is the product of the denominators  .

.

In parallel with equation (9.31), we also have

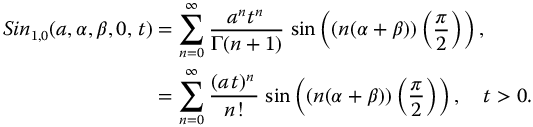

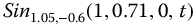

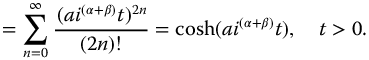

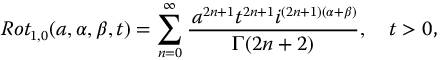

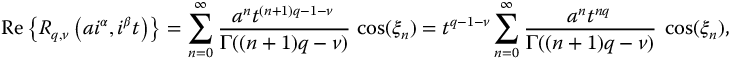

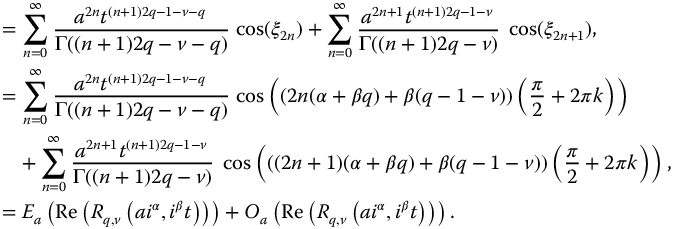

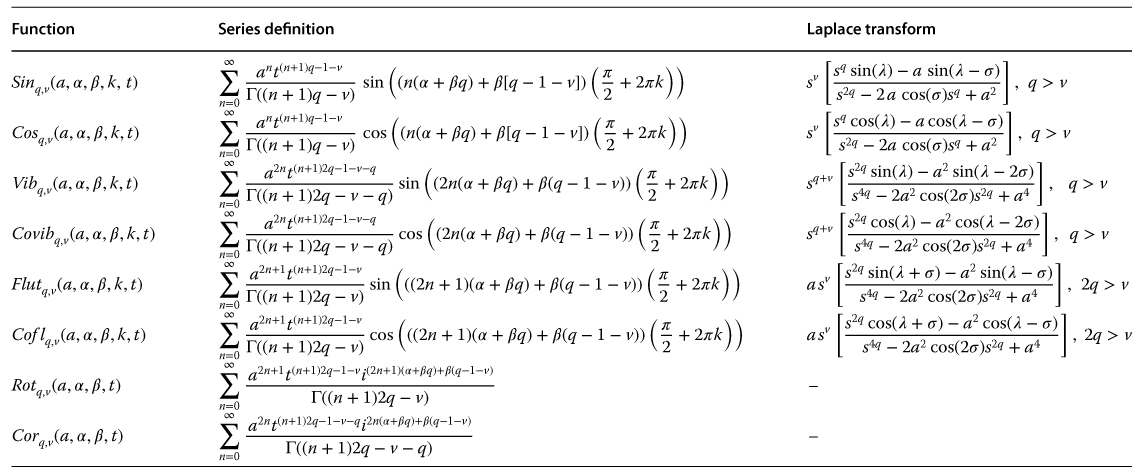

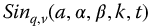

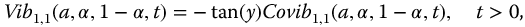

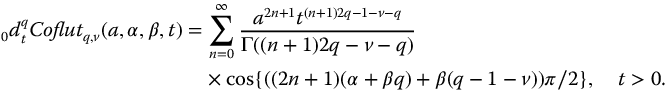

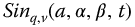

Table 9.1 presents special values for the fractional meta-trigonometric functions when  and

and  . The row

. The row  can apply to the R1-hyperboletry, while the row

can apply to the R1-hyperboletry, while the row  can apply to the R1- and R2-trigonometries. The R3-trigonometry is a special case of the

can apply to the R1- and R2-trigonometries. The R3-trigonometry is a special case of the  row. Of course, any of these rows may also be applied to noninteger values of

row. Of course, any of these rows may also be applied to noninteger values of  and

and  . Continuing from Ref. [82] with permission of ASME:

. Continuing from Ref. [82] with permission of ASME:

Some observations may be made from the table. For example, for the

-function column all terms are of the form

. This may be shown as follows:

Similarly, for the

column, all terms are of the form

, since

Thus, we see that these functions are backward compatible with the hyperbolic functions with imaginary arguments. Other relationships are observed for the remaining columns.

Table 9.1 Special values of the generalized trignobolic functions

Source: Lorenzo 2009a [82]. Reproduced with permission of ASME.

For this table  , also

, also  , – indicates only series description found.

, – indicates only series description found.

9.3 Commutative Properties of the Complexity and Parity Operations

In this section, we demonstrate that the operations of determining the real/imaginary parts and even/odd parts of the parity functions may be interchanged. We start with the real part of  from equation (9.6); then, for

from equation (9.6); then, for  , we have

, we have

where  . Expanding the summation yields

. Expanding the summation yields

Collecting even and odd powers of a gives

However, we also observe that

and that

Now, from equations (9.29) and (9.42), we have

and from equations (9.32) and (9.43)

proving the assertion for these functions.

For the remaining functions, we begin with the imaginary part of  , from equation (9.7)

, from equation (9.7)

where  and

and  . Expanding this summation yields

. Expanding this summation yields

Again, collecting even and odd powers of a gives

Here, we observe

and

Now, using equations (9.30) with (9.49)

and from equations (9.33) and (9.50),

completing the demonstration of the complexity–parity commutivity properties of  . These properties are summarized for the meta-trigonometric functions with t > 0 [83]:

. These properties are summarized for the meta-trigonometric functions with t > 0 [83]:

where  and

and  refer to terms containing the odd and even powers of a, respectively.

refer to terms containing the odd and even powers of a, respectively.

9.3.1 Graphical Presentation – Parity Functions

Once again, it is not possible to show a representative display of the parity functions. The problem is exacerbated because the number of functions is doubled. Thus, the focus is on the effect of the generalizing variables  and

and  .

.

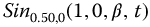

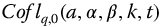

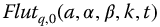

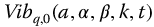

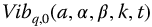

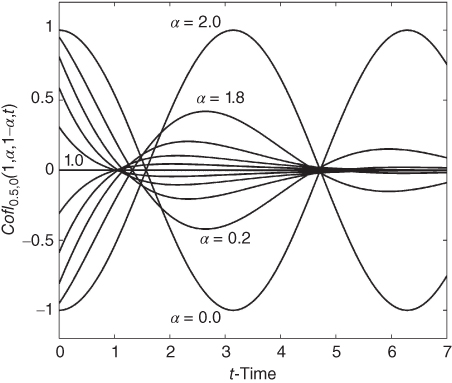

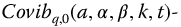

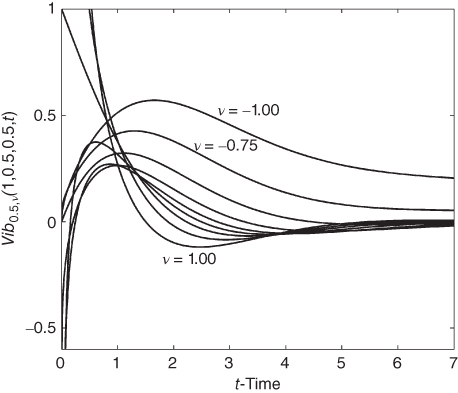

Figures 9.32–9.35 show the effect of the primary order variable, q, on the parity functions,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  as a function of t time, with

as a function of t time, with  = 0.5 and

= 0.5 and  = 0.5. Because

= 0.5. Because  = 1,

= 1,  = 0 corresponds to the R1-trigonometry and

= 0 corresponds to the R1-trigonometry and  = 0,

= 0,  = 1 corresponds to the R2-trigonometry, the choice of

= 1 corresponds to the R2-trigonometry, the choice of  = 0.5 and

= 0.5 and  = 0.5 examines a new trigonometry sharing aspects of both R1- and R2-trigonometries. An observed feature of these figures is that increasing the order q increases the oscillatory behavior of the function in most cases. Note that the reversal of the first peak amplitude for

= 0.5 examines a new trigonometry sharing aspects of both R1- and R2-trigonometries. An observed feature of these figures is that increasing the order q increases the oscillatory behavior of the function in most cases. Note that the reversal of the first peak amplitude for  for the

for the  - and

- and  -functions.

-functions.

Figure 9.32 The effect of q for  , q = 0.1–1.0 in steps of 0.1, with a = 1, v = 0, k = 0,

, q = 0.1–1.0 in steps of 0.1, with a = 1, v = 0, k = 0,  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 0.5.

= 0.5.

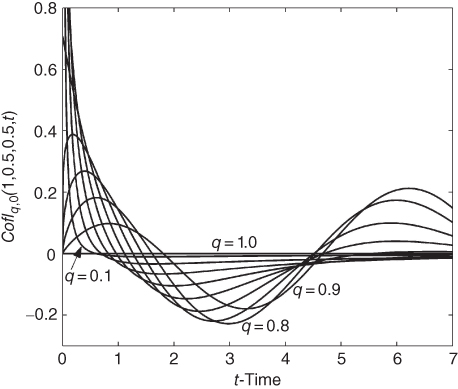

Figure 9.33 The effect of q for  , q = 0.1–1.0 in steps of 0.1, with a = 1, v = 0, k = 0,

, q = 0.1–1.0 in steps of 0.1, with a = 1, v = 0, k = 0,  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 0.5.

= 0.5.

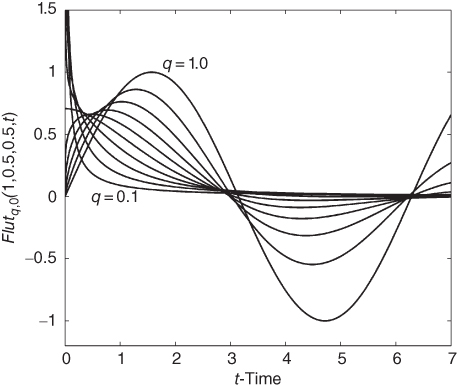

Figure 9.34 The effect of q for  , q = 0.1–1.0 in steps of 0.1, with a = 1, v = 0, k = 0,

, q = 0.1–1.0 in steps of 0.1, with a = 1, v = 0, k = 0,  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 0.5.

= 0.5.

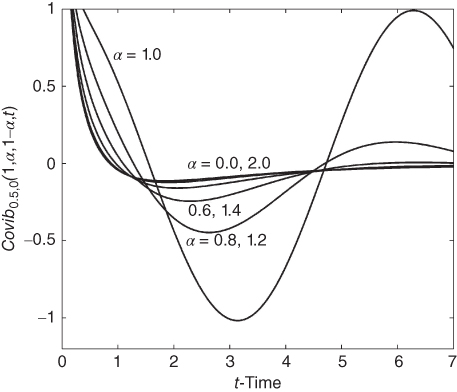

Figure 9.35 The effect of q for  , q = 0.1–1.0 in steps of 0.1, with a = 1, v = 0, k = 0,

, q = 0.1–1.0 in steps of 0.1, with a = 1, v = 0, k = 0,  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 0.5.

= 0.5.

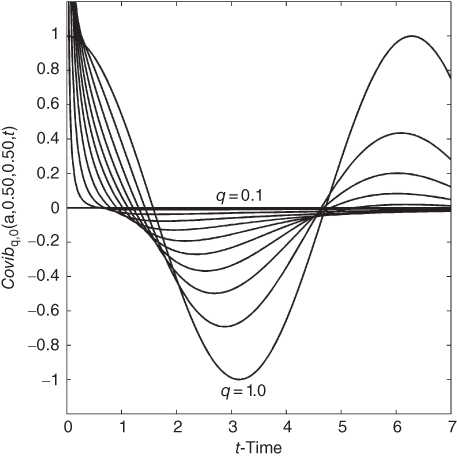

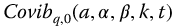

Figure 9.36 The effect of  and

and  ,

,  , for

, for  , with

, with  = 0.0–2.0 in steps of 0.2, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0.

= 0.0–2.0 in steps of 0.2, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0.

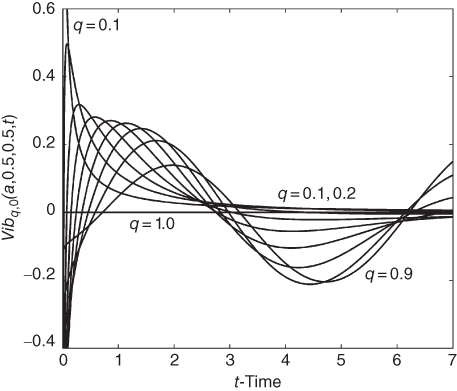

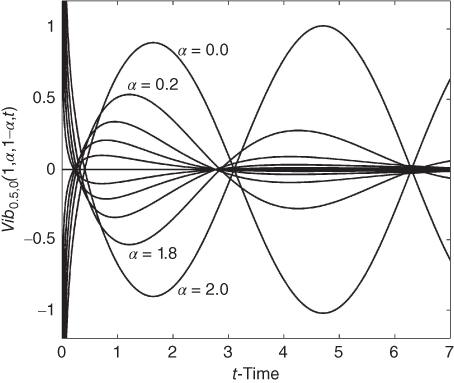

Figure 9.37 The effect of  and

and  ,

,  , for

, for  , with

, with  = 0.0–2.0 in steps of 0.2, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0.

= 0.0–2.0 in steps of 0.2, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0.

Figure 9.38 The effect of  and

and  ,

,  , for

, for  , with

, with  = 0.0–2.0 in steps of 0.2, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0.

= 0.0–2.0 in steps of 0.2, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0.

The effect of  and

and  , where

, where  , for

, for  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  functions is shown in Figures 9.36–9.39. For these figures,

functions is shown in Figures 9.36–9.39. For these figures,  = 0.0–2.0 in steps of 0.2, and q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0. Note that the responses for the

= 0.0–2.0 in steps of 0.2, and q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0. Note that the responses for the  ,- and

,- and  -functions are symmetric around

-functions are symmetric around  , and the

, and the  and

and  functions overlay themselves for

functions overlay themselves for  , where

, where  .

.

Figure 9.39 The effect of  and

and  ,

,  , for

, for  , with

, with  = 0.0–2.0 in steps of 0.2, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0.

= 0.0–2.0 in steps of 0.2, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0.

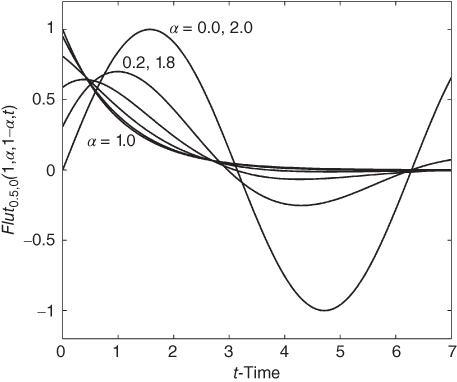

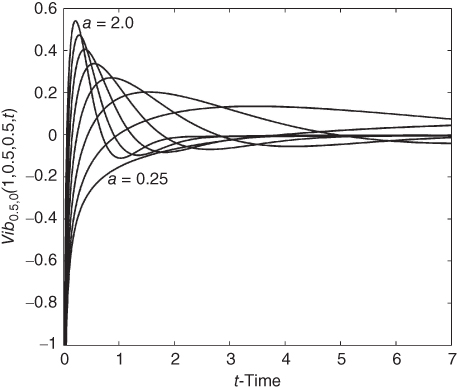

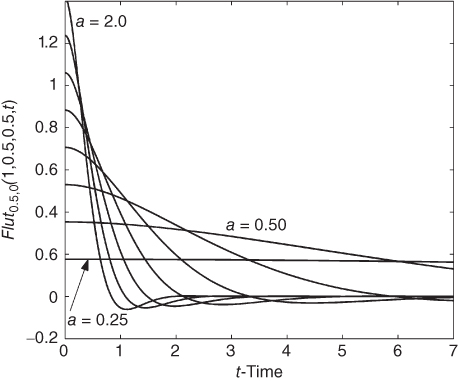

Figures 9.40 and 9.41 study the effect of a for  - and

- and  -functions with a = 0.25– 2.0 in steps of 0.25, and with q = 0.5,

-functions with a = 0.25– 2.0 in steps of 0.25, and with q = 0.5,  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 0.5, v = 0, k = 0.

= 0.5, v = 0, k = 0.

Figure 9.40 The effect of a for  , with a = 0.25–2.0 in steps of 0.25, and with q = 0.5,

, with a = 0.25–2.0 in steps of 0.25, and with q = 0.5,  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 0.5, v = 0, k = 0.

= 0.5, v = 0, k = 0.

Figure 9.41 The effect of a for  , with a = 0.25–2.0 in steps of 0.25, and with q = 0.5,

, with a = 0.25–2.0 in steps of 0.25, and with q = 0.5,  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 0.5, v = 0, k = 0.

= 0.5, v = 0, k = 0.

Figures 9.42 and 9.43 study the effect of the differintegration variable, v, for the  - and

- and  -functions with v = −1.0 to 1.0 in steps of 0.25, and with q = 0.5, a = 1,

-functions with v = −1.0 to 1.0 in steps of 0.25, and with q = 0.5, a = 1,  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 0.5, k = 0.

= 0.5, k = 0.

Figure 9.42 The effect of v for  , with v = −1.0–1.0 in steps of 0.25, and with q = 0.5, a = 1,

, with v = −1.0–1.0 in steps of 0.25, and with q = 0.5, a = 1,  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 0.5, k = 0.

= 0.5, k = 0.

Figure 9.43 The effect of v for  , with v = −1.0–1.0 in steps of 0.25, and with q = 0.5, a = 1,

, with v = −1.0–1.0 in steps of 0.25, and with q = 0.5, a = 1,  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 0.5, k = 0.

= 0.5, k = 0.

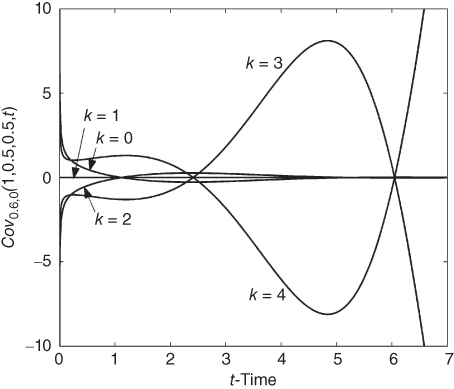

Figure 9.44 considers the effect of the index variable k, for k = 0–4, with q = 3/5, a = 1,  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 0.5, v = 0. Note again the untypical symmetric responses resulting from the particular choice of q.

= 0.5, v = 0. Note again the untypical symmetric responses resulting from the particular choice of q.

Figure 9.44 Effect of k, for k = 0–4, with q = 3/5, a = 1,  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 0.5, v = 0.

= 0.5, v = 0.

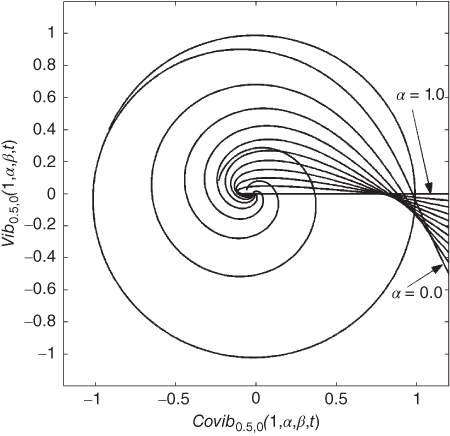

Figure 9.45 Phase plane showing the effect of  and

and  ,

,  , for

, for  versus

versus  with

with  = 0.0–1.0 in steps of 0.1, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0, t = 0–9.

= 0.0–1.0 in steps of 0.1, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0, t = 0–9.

The remaining figures (Figures 9.45–9.52) are phase plane plots chosen to expose a few of the many varied possibilities. Figures 9.45 and 9.46 are phase planes showing the effect of  and

and  , where

, where  , for

, for  versus

versus  . For Figure 9.45,

. For Figure 9.45,  = 0.0–1.0 in steps of 0.1, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0. For Figure 9.46,

= 0.0–1.0 in steps of 0.1, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0. For Figure 9.46,  = 1.0 to 2.0 in steps of 0.1, also with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0. All cases arrive from infinity and spiral into the origin except

= 1.0 to 2.0 in steps of 0.1, also with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0. All cases arrive from infinity and spiral into the origin except  = 2.0, which is attracted to the unit circle. From Lorenzo [83]:

= 2.0, which is attracted to the unit circle. From Lorenzo [83]:

A particularly interesting, and important, pair of plots is found in Figures 9.47 and 9.48 for the

versus

phase plane. For both cases,

= 1.0–2.0 and q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0. While it is not obvious because of the change of scale between the pair, in Figure 9.47 as

is varied over the range

, with

, the responses start from the unit circle and diverge to infinity. In Figure 9.48 with

and all other variables the same, the responses start from the same identical points as in Figure 9.47 but are attracted to the origin. Furthermore, the slopes across the unit circle are preserved for each response. This behavior and its interpretation are discussed in more detail in Section 9.12.

Figure 9.46 Phase plane showing the effect of  and

and  ,

,  , for

, for  versus

versus  with

with  = 1.0–2.0 in steps of 0.1, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0, t = 0–9.

= 1.0–2.0 in steps of 0.1, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0, k = 0, t = 0–9.

Figure 9.47 Phase plane showing the effect of  for

for  versus

versus  with

with  = 1.0–2.0 in steps of 0.1, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0,

= 1.0–2.0 in steps of 0.1, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0,  = 1, k = 0.

= 1, k = 0.

Source: Lorenzo 2009b [83]. Reproduced with permission of ASME.

Figure 9.48 . Phase plane showing the effect of  for

for  versus

versus  with

with  = 1.0–2.0 in steps of 0.1, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0,

= 1.0–2.0 in steps of 0.1, and with q = 0.5, a = 1, v = 0,  = 3, k = 0.

= 3, k = 0.

Source: Lorenzo 2009b [83]. Reproduced with permission of ASME.

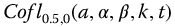

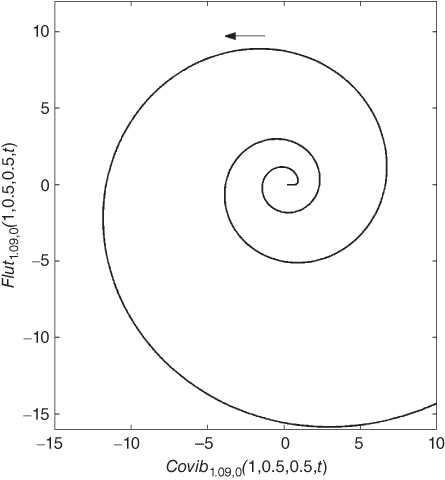

Figure 9.49 Phase plane for  versus

versus  with

with  = 0.16,

= 0.16,  = 1.25, and with q = 0.80, a = 0.8, v = 0, k = 0, t = 0–40.

= 1.25, and with q = 0.80, a = 0.8, v = 0, k = 0, t = 0–40.

Figure 9.50 Phase plane for  versus

versus  with

with  = 0.5, and with q = 1.09, a = 1.0, v = 0, k = 0, t = 0–19.

= 0.5, and with q = 1.09, a = 1.0, v = 0, k = 0, t = 0–19.

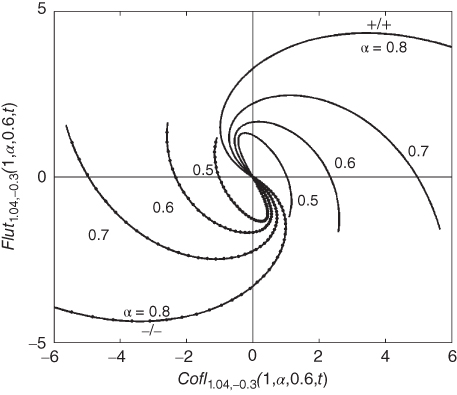

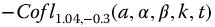

Figure 9.51 Phase plane for  versus

versus  and

and  versus

versus  with

with  = 0.5–0.8,

= 0.5–0.8,  = 0.6, and with q = 1.04, v = −0.3, a = 1.0, k = 0, t = 0–4.8.

= 0.6, and with q = 1.04, v = −0.3, a = 1.0, k = 0, t = 0–4.8.

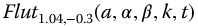

Figure 9.52 Phase plane for  versus

versus  and

and  versus

versus  with

with  = 0.5–0.8,

= 0.5–0.8,  = 0.6, and with q = 1.04, v = −0.3, a = 1.0, k = 0, t = 0–4.8.

= 0.6, and with q = 1.04, v = −0.3, a = 1.0, k = 0, t = 0–4.8.

Source: Lorenzo 2009b [83]. Reproduced with permission of ASME.

Figure 9.49 shows an interesting spiral converging to the origin that is similar to some of the classical spirals [64], pp. 188, 189. Figures 9.50–9.53 are phase plane plots of several barred spirals based on the parity functions. Figure 9.51 presents a phase plane for  versus

versus  and

and  versus

versus  with

with  = 0.5–0.8. The spirals start at the origin and spiral out to infinity with increasing rate as

= 0.5–0.8. The spirals start at the origin and spiral out to infinity with increasing rate as  increases.

increases.

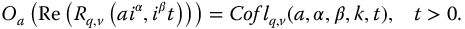

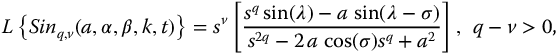

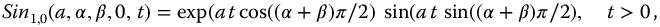

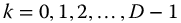

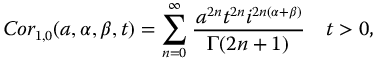

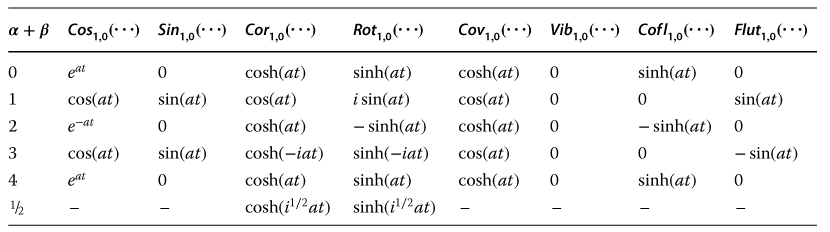

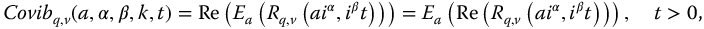

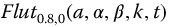

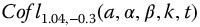

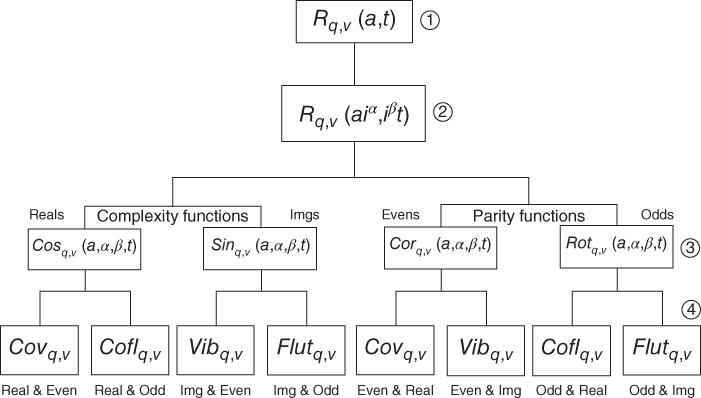

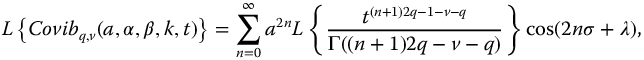

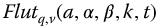

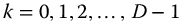

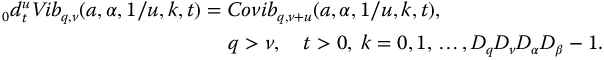

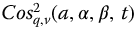

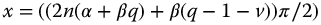

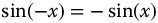

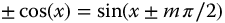

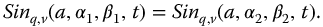

Figure 9.53 Taxonomy of the fractional meta-trigonometric functions.

Source: Lorenzo 2009b [83]. Reproduced with permission of ASME.

Figure 9.52 is a very interesting phase plane plot for  versus

versus  and

and  versus

versus  with

with  = 0.5–0.8. The unusual feature here is that the departure is from the end of the spiral bar as

= 0.5–0.8. The unusual feature here is that the departure is from the end of the spiral bar as  increases. Such barred spiral behavior is of particular interest in the astrophysics of the galaxies. More such behaviors are studied in Chapter 18.

increases. Such barred spiral behavior is of particular interest in the astrophysics of the galaxies. More such behaviors are studied in Chapter 18.

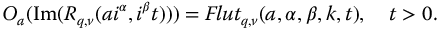

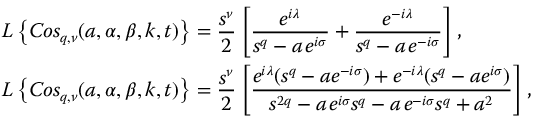

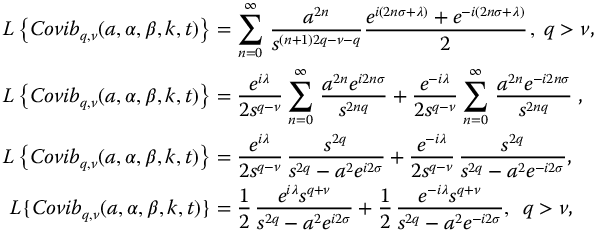

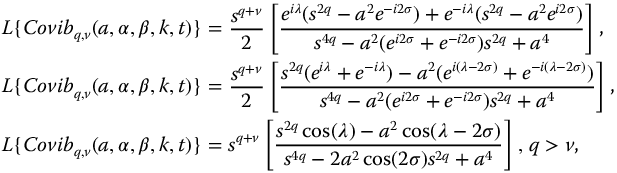

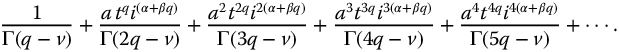

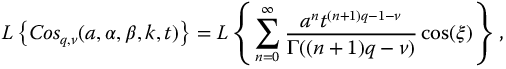

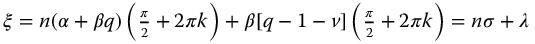

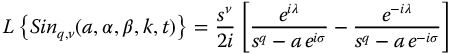

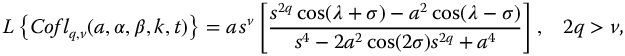

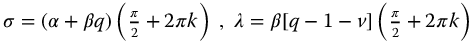

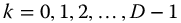

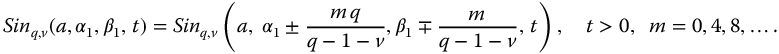

9.4 Laplace Transforms of the Fractional Meta-Trigonometric Functions

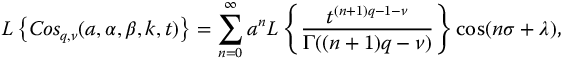

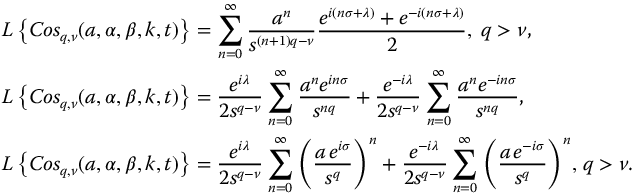

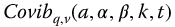

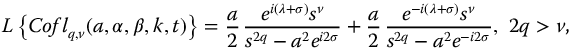

The development of the Laplace transform for the generalized functions parallels that of the previous trigonometries.

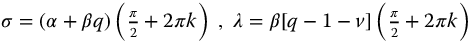

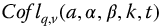

where  ,

,  , and where D is the product of the denominators

, and where D is the product of the denominators  , in equation (9.3), in minimal form. Because the series converges uniformly (see Sections 3.16 and 14.3), we may transform term-by-term. Thus,

, in equation (9.3), in minimal form. Because the series converges uniformly (see Sections 3.16 and 14.3), we may transform term-by-term. Thus,

Continuing from Ref. [83]:

Recognizing the summations using equation (7.52) gives

where  ,

,  , and

, and  . The two forms, those of equations (9.65) and (9.66), are particularly useful.

. The two forms, those of equations (9.65) and (9.66), are particularly useful.

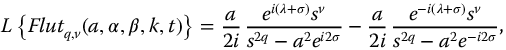

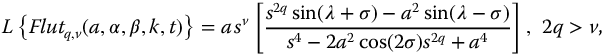

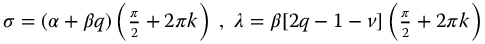

The derivation for the Laplace transform of  proceeds in a similar manner:

proceeds in a similar manner:

with  ,

,  and giving the results

and giving the results

and

where  and

and  .

.

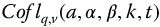

The Laplace transform for the  follows.

follows.

Continuing from Ref. [83]:

where  , and

, and  is the product of the denominators

is the product of the denominators  , in minimal form and where

, in minimal form and where  and

and  .

.

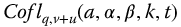

Similarly, for the  , we have

, we have

where  , and

, and  .

.

The Laplace transform for the  follows:

follows:

where  , and

, and  .

.

The derivation for the  is similar to that for

is similar to that for  and yields

and yields

where  , and

, and  .

.

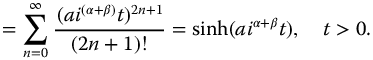

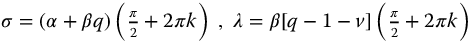

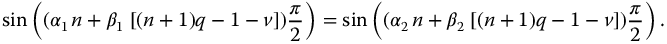

This collection of Laplace transforms generalizes those derived for the previous trigonometries. Comparison of these transforms with the parallel results for the R3-trigonometric functions shows that the transforms are structurally the same and the R3 results may be had by the substitutions  . Table 9.2 summarizes the Laplace transforms of the meta-trigonometric functions.

. Table 9.2 summarizes the Laplace transforms of the meta-trigonometric functions.

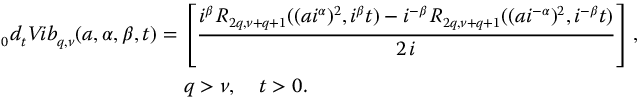

Table 9.2 Summary of the meta-trigonometric functions

Source: Lorenzo 2009b [83]. Reproduced with permission of ASME.

,

,  ,

,  ; D is the product of the denominators of

; D is the product of the denominators of  with repeated multipliers removed.

with repeated multipliers removed.

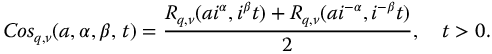

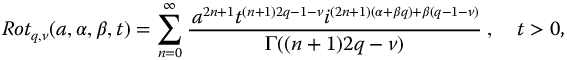

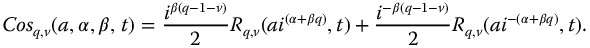

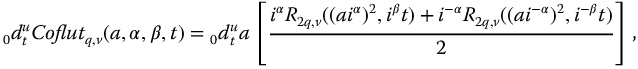

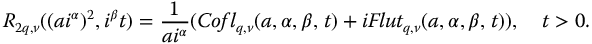

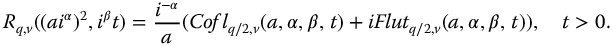

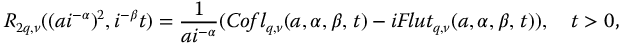

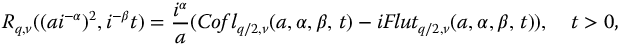

9.5 R-Function Representation of the Fractional Meta-Trigonometric Functions

The fractional exponential or R-function representation of the trigonometric functions is useful for analysis and numerical computation. Continuing from Ref. [83]:

Now, from the definition of

, we have for t > 0

Now,

Applying equation (3.124), namely  , yields

, yields

Then,

The summations are recognized as R-functions giving the result

Applying equation (3.121) simplifies the result to

The remaining functions are determined in a similar manner and are listed in two forms, t real and complex; thus, we have

or

or

or

or

or

Finally, summarizing the results of equations (9.22) and (9.24)

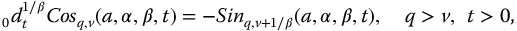

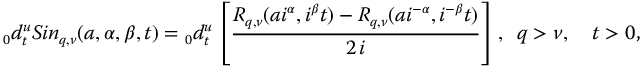

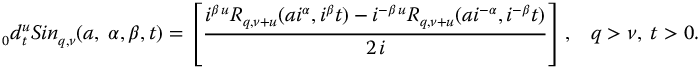

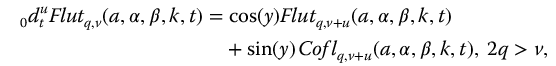

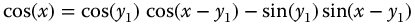

9.6 Fractional Calculus Operations on the Fractional Meta-Trigonometric Functions

For the fractional differintegrations that follow, it is assumed that the integrated function, and all of its derivatives, are identically zero for all t < 0. Continuing from Ref. [83]:

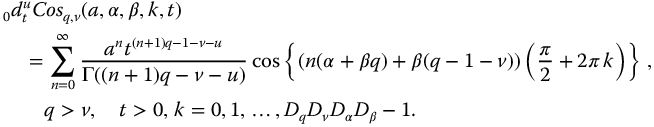

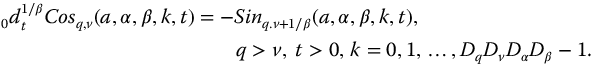

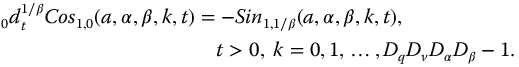

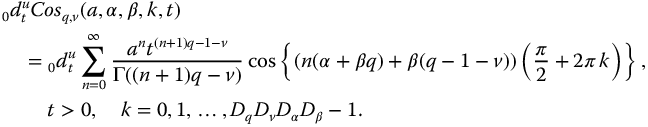

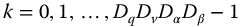

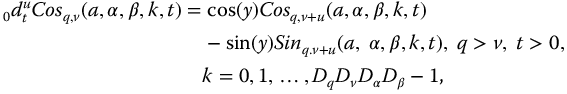

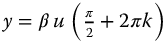

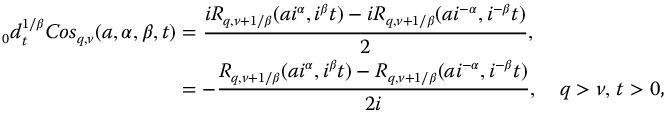

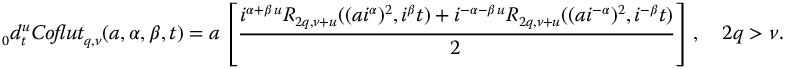

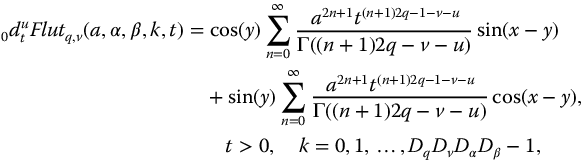

9.6.1 Cosq,v(a, α, β, k, t)

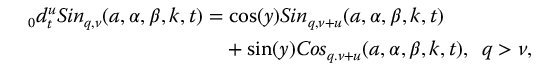

The u-order differintegral of  is determined for t > 0 as

is determined for t > 0 as

We may differintegrate term-by-term (see Section 3.16); thus,

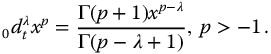

Applying equation (5.37), that is,

Thus equation (9.96) becomes

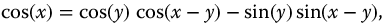

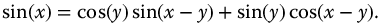

From the sum and difference formulas for the integer-order trigonometry, the following identities may be derived:

and

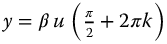

Now, in equation (9.98), let  , and

, and  , with

, with  ; then applying equation (9.99) gives

; then applying equation (9.99) gives

The summations are recognized as  and

and  , respectively, yielding the final result

, respectively, yielding the final result

where  . Taking

. Taking  , we have

, we have  and

and  giving

giving

Now, taking

An alternative development of the result of equation (9.103) is obtained as follows:

by the differentiation equation (3.114)

When  , we have

, we have

which is recognized as

which is identically equation (9.104) when  .

.

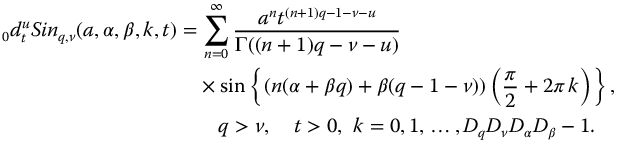

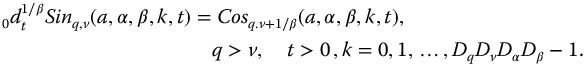

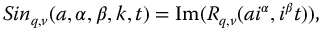

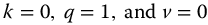

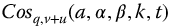

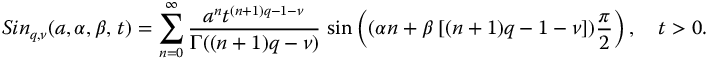

9.6.2 Sinq,v(a, α, β, k, t)

Determination of the differintegral for the  -function proceeds in a manner similar to that of the

-function proceeds in a manner similar to that of the  . Then, the u-order differintegral of

. Then, the u-order differintegral of  is determined as

is determined as

Application of equation (9.97) to this equation gives

In equation (9.110), let  and

and  ,

,  ; then applying equation (9.100), we have

; then applying equation (9.100), we have

The summations are seen to be  and

and  , respectively, yielding the final result

, respectively, yielding the final result

where  . Taking

. Taking  , we have

, we have  and

and  , giving

, giving

Furthermore, taking  gives

gives

The R-function-based development of the result of equation (9.113) is obtained based on equation (9.84) as

by the differentiation equation (3.114)

When  and k = 0, this yields the same result as equation (9.113).

and k = 0, this yields the same result as equation (9.113).

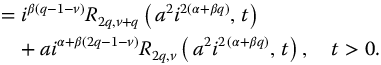

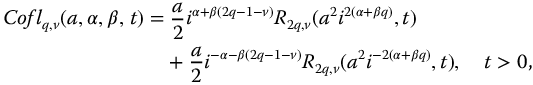

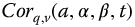

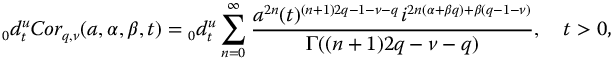

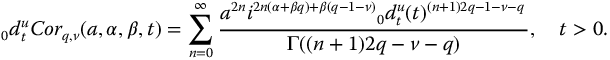

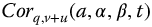

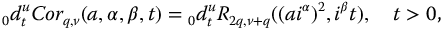

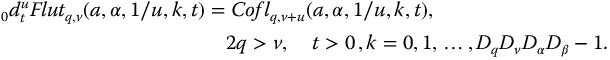

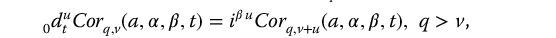

9.6.3 Corq,v(a, α, β, t)

The u-order differintegral for the  -function is determined, using definition (9.2.8), as

-function is determined, using definition (9.2.8), as

Application of equation (9.97) to this equation gives

with  , and where the summation has been recognized as an

, and where the summation has been recognized as an  -function, to yield the final result. In terms of the R-function, we have

-function, to yield the final result. In terms of the R-function, we have

or

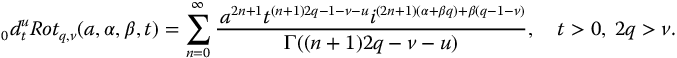

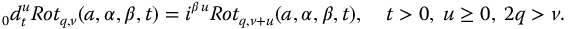

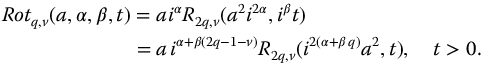

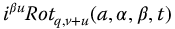

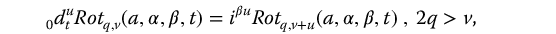

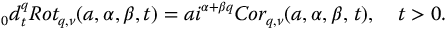

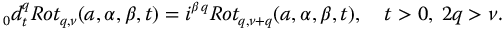

9.6.4 Rotq,v(a, α, β, t)

Determination of the differintegral for the  -function proceeds in a manner similar to that of

-function proceeds in a manner similar to that of  . Then, the u-order differintegral of

. Then, the u-order differintegral of  is determined as

is determined as

Application of equation (9.97) to this equation gives

The summation is seen to be  , yielding

, yielding

In terms of the R-function representation, we have

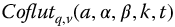

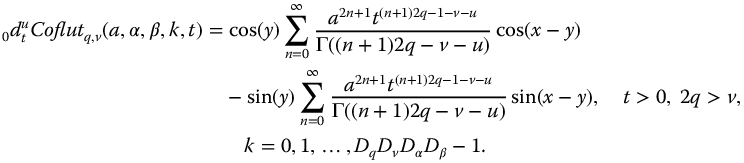

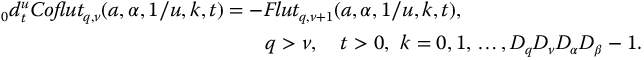

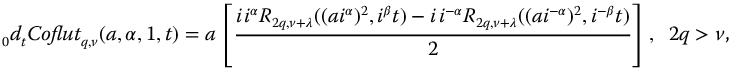

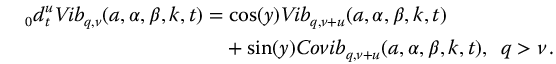

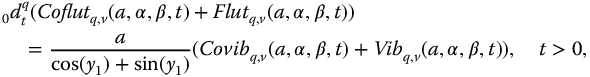

9.6.5 Coflutq,v(a, α, β, k, t)

In this section, we determine the differintegral of the Coflutter function. The u-order differintegral of  is determined as

is determined as

Application of equation (9.97) to this equation gives

with  . Now, in equation (9.128), let

. Now, in equation (9.128), let  ,

,  , also, let

, also, let  ; then, applying equation (9.99), we have

; then, applying equation (9.99), we have

The summations are recognized as  and

and  , yielding the desired differintegral form

, yielding the desired differintegral form

where  . For the special case with

. For the special case with  , we have

, we have  and

and  , giving

, giving

Taking  in equation (9.130) gives the general form for the differintegral of the Coflutter function as

in equation (9.130) gives the general form for the differintegral of the Coflutter function as

Furthermore, with  , we have

, we have

The alternative R-function-based development of the results of equation (9.90) is obtained as

by the differentiation equation (3.114)

For the case  ,

,

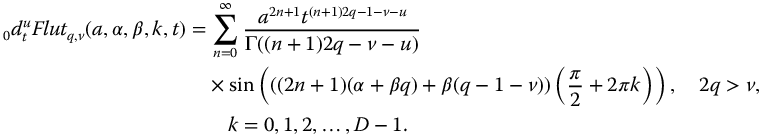

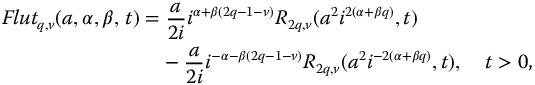

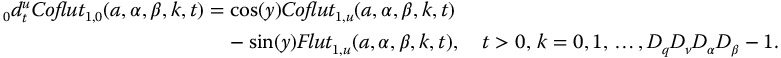

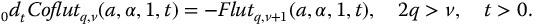

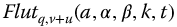

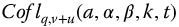

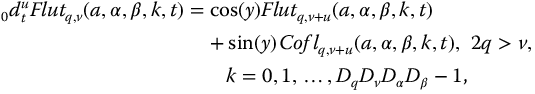

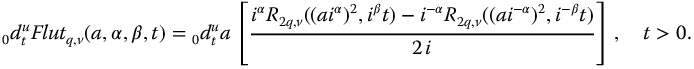

9.6.6 Flutq,v(a, α, β, k, t)

The  -order differintegral of

-order differintegral of  is determined as

is determined as

where  is in minimal form.

is in minimal form.

Applying equation (9.97) to this equation gives

Now, in equation (9.139), let  ,

,  and let

and let  ; then, applying equation (9.100), we have

; then, applying equation (9.100), we have

with  . The summations are recognized as

. The summations are recognized as  and

and  , respectively, yielding the final result

, respectively, yielding the final result

where  . For the special case where

. For the special case where  , we have

, we have  and

and  , giving

, giving

The alternative R-function-based development of the results of equation (9.92) is obtained as follows:

Application of the differentiation equation (3.114) gives the result

With  , we have

, we have

or

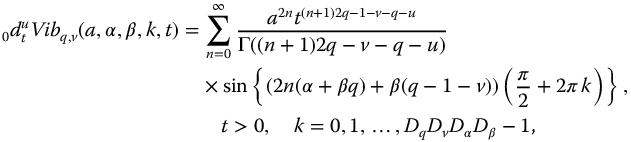

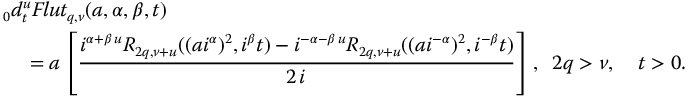

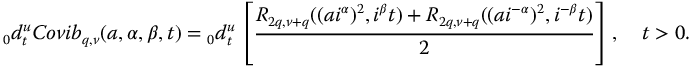

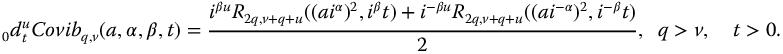

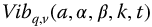

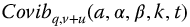

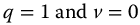

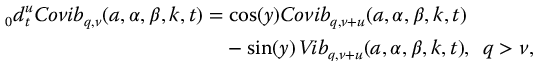

9.6.7 Covibq,v(a, α, β, k, t)

The  -order differintegral of the

-order differintegral of the  is determined as follows:

is determined as follows:

Application of equation (9.97) to this equation gives

Now let  ,

,  in equation (9.147) and let

in equation (9.147) and let  ,

,  ; then, applying equation (9.99), we have

; then, applying equation (9.99), we have

The summations are seen to be  and

and  , respectively, yielding the key result

, respectively, yielding the key result

where  . When

. When  we have

we have  and

and  ; thus,

; thus,

The R-function-based differintegral is obtained as

By the differentiation equation (3.114)

When  , we have

, we have

The right-hand side is seen to be  , thus validating equation (9.150).

, thus validating equation (9.150).

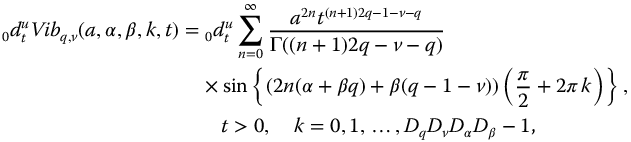

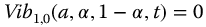

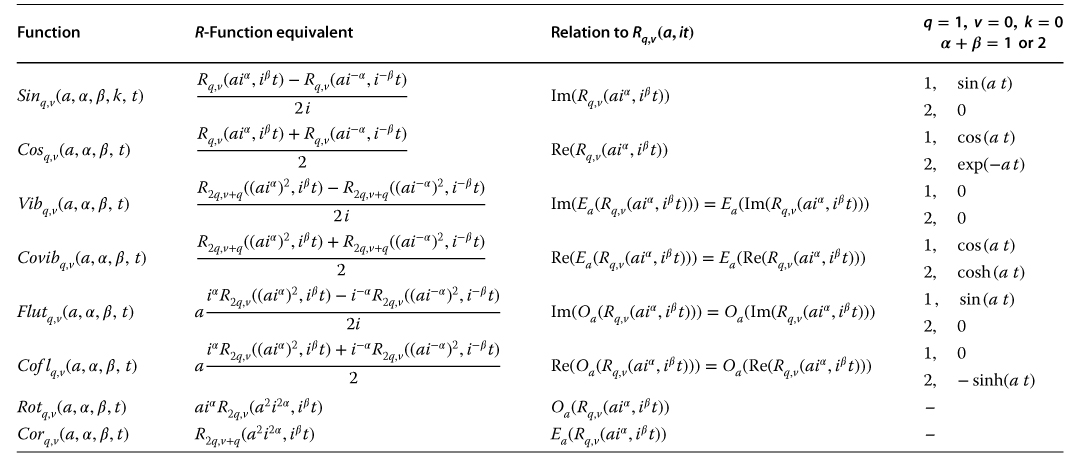

9.6.8 Vibq,v(a, α, β, k, t)

The  -order differintegral of the generalized vibration function,

-order differintegral of the generalized vibration function,  , is derived as follows:

, is derived as follows:

Application of equation (9.97) to this equation gives

with  . Now, let

. Now, let  ,

,  ,

,  , in equation (9.154). Then, applying equation (9.100), we have

, in equation (9.154). Then, applying equation (9.100), we have

The summations are recognized as  and

and  , respectively, yielding the key result

, respectively, yielding the key result

where  . When

. When  , we have

, we have  and

and  , giving

, giving

Now, taking  in equation (9.156),

in equation (9.156),

With both  and with

and with  , we have

, we have

However, if additionally  ,

,  ; therefore, we have

; therefore, we have

where  . The alternative R-function-based development of the results of equation (9.88) is obtained as

. The alternative R-function-based development of the results of equation (9.88) is obtained as

by the differintegration equation (3.114)

When  , we have

, we have

Tables 9.2 and 9.3 summarize the various properties of the meta-trigonometric functions.

Table 9.3 Summary of the meta-trigonometric functions

Source: Lorenzo 2009b [83]. Reproduced with permission of ASME.

,

,  ; D is the product of the denominators of

; D is the product of the denominators of  in minimum form.

in minimum form.

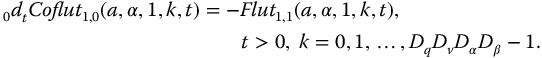

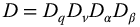

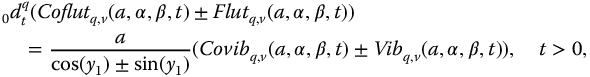

9.6.9 Summary of Fractional Calculus Operations on the Meta-Trigonometric Functions

For ease of reference the fractional calculus operations are summarized here. The derivations are for t > 0, and  and

and  :

:

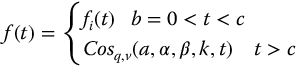

9.7 Special Topics in Fractional Differintegration

In this, and previous chapters, fractional differintegrals of the fractional trigonometric functions have been derived. In all cases, the fractional differintegration has started from t = 0. Because the functions are zero for t < 0, initialization or history effects have not been an issue. However, when a function does not start from zero or is segmented, such as

and preceded by another different function, fractional differintegrations must consider the initialization effects caused by the preceding function. Clearly, there will be times when it is desired to start a fractional differintegration at times other than t = 0. The reader is cautioned that fractional differintegration differs from integer-order integration in this important regard. Detailed analysis of these important differences is addressed in Appendix D.

9.8 Meta-Trigonometric Function Relationships

This section determines generalized identities for the fractional meta-trigonometric functions in terms of the fractional exponential functions. These are parallel to the very basic identities presented in equations (1.18) and (1.19). The results will, of course, apply to all particular fractional trigonometries that may be derived by specializing the results of this chapter.

9.8.1 Cosq,v(a, α, β, t) and Sinq,v(a, α, β, t) Relationships

The generalized fractional Euler equation, with k = 0, for the  - and

- and  -functions was determined in Section 9.1 as

-functions was determined in Section 9.1 as

The complementary generalized fractional Euler equation, with k = 0, can be determined by expanding  , in a manner similar to the expansion from equation (9.1) to (9.5), or by subtracting equation (9.84) from (9.82), which gives

, in a manner similar to the expansion from equation (9.1) to (9.5), or by subtracting equation (9.84) from (9.82), which gives

Continuing from Ref. [83]:

Adding and subtracting the resultant equations provides the following two identities:

From the result of equation (9.176), it is clear that because  and

and  are real, the product

are real, the product  must also be real. Thus, we note that

must also be real. Thus, we note that  is the complex conjugate of

is the complex conjugate of  . These identities (9.176) and (9.177) are broad generalizations of

. These identities (9.176) and (9.177) are broad generalizations of  and

and  from the ordinary trigonometry. This may be shown by taking

from the ordinary trigonometry. This may be shown by taking  in equations (9.176) and (9.177).

in equations (9.176) and (9.177).

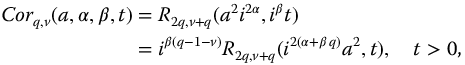

9.8.2 Corq,v(a, α, β, t) and Rotq,v(a, α, β, t) Relationships

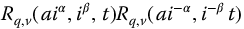

Consider, from equation (9.124) with

The summation is recognized as  yielding

yielding

From equation (9.125), we have

Therefore,

Continuing from Ref. [83]:

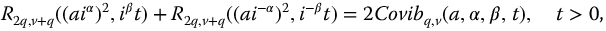

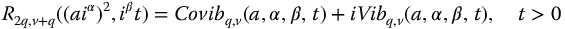

9.8.3 Covibq,v(a, α, β, t) and Vibq,v(a, α, β, t) Relationships

Equations (9.86) and (9.88) are rewritten in the following form:

Adding these equations gives the generalized fractional semi-Euler equation for the Vibration functions as

or

While subtracting yields the generalized complementary semi-Euler equation

or

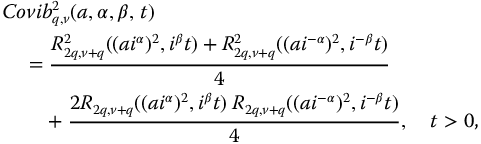

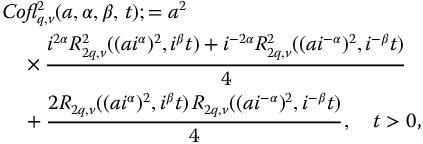

The terminology semi-Euler is used because of the q to q/2 relationship between the right- and left-hand sides of the equations. Squaring equations (9.86) and (9.88) yields

Adding and subtracting these equations give

meta-identities relating the  and

and  -functions.

-functions.

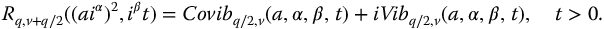

9.8.4 Coflq,v(a, α, β, t) and Flutq,v(a, α, β, t) Relationships

The  - and

- and  -functions can also be related. We rewrite equations (9.90) and (9.92) as follows:

-functions can also be related. We rewrite equations (9.90) and (9.92) as follows:

and

Adding equations (9.192) and (9.193) gives

Alternatively,

the generalized fractional semi-Euler equation for the Flutter functions. Subtracting equation (9.193) from (9.192) yields

or

the generalized complementary fractional semi-Euler equation for the Flutter functions. The functions as represented in equations (9.90) and (9.92) are squared to give

The sum and difference of these equations yield

generalized identities relating the  and

and  -functions.

-functions.

9.8.5 Coflq,v(a, α, β, t) and Vibq,v(a, α, β, t) Relationships

Taking  and k = 0 in equation (9.139) gives

and k = 0 in equation (9.139) gives

Now,

Let  and

and  with

with

Then, we may write equation (9.203) as

More succinctly,

Taking  , and k = 0 in equation (9.204) gives

, and k = 0 in equation (9.204) gives

Now,

Using the same substitutions  and

and  with

with  into equation (9.208) gives

into equation (9.208) gives

Adding equations (9.206) and (9.209) yields the interesting result

where  . Subtracting equation (9.206) from (9.209) gives the complementary result, which may be combined into the single identity

. Subtracting equation (9.206) from (9.209) gives the complementary result, which may be combined into the single identity

where again  .

.

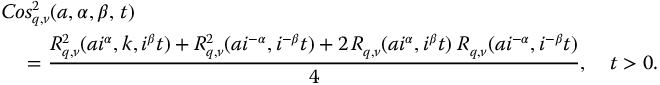

9.8.6 Cosq,v(a, α, β, t) and Sinq,v(a, α, β, t) Relationships to Other Functions

The following relationships are presented without proof. They may be easily shown by substitution into the defining series and with the use of equations (9.99) and (9.100):

For the principal functions, we have

where  .

.

where  .

.

These are but a few of the many relationships possible for the meta-trigonometric functions. Many other relations paralleling the multiple- and fractional-angle formulas from the integer-order trigonometry and more are yet to be derived.

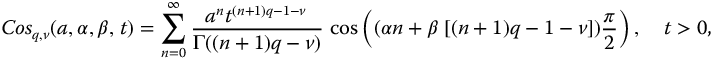

9.8.7 Meta-Identities Based on the Integer-order Trigonometric Identities

Because the series definitions of the meta-trigonometric functions contain the periodic cosine and sine functions, inter-relationships may be determined for these functions. This section determines meta-identities based on these relationships for the  - and

- and  -functions. Identities such as

-functions. Identities such as  and

and  are possible bases, as are the following identities provided by Spanier and Oldham [116], pp. 298–299 from the integer-order trigonometry:

are possible bases, as are the following identities provided by Spanier and Oldham [116], pp. 298–299 from the integer-order trigonometry:

Identities for the  -functions are considered first.

-functions are considered first.

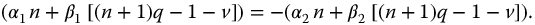

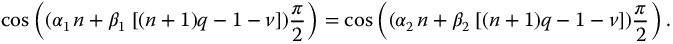

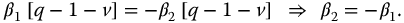

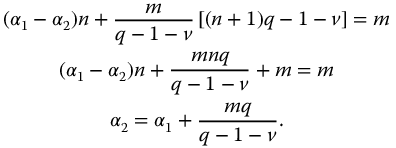

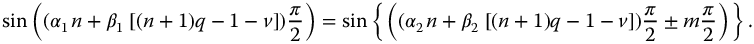

9.8.7.1 The cos(−x) = cos(x)-Based Identity for Cosq,v(a, α, β, t)

The question to be answered is: For given values of q and v what values for  and

and  will provide an identical function with parameters

will provide an identical function with parameters  and

and  ? In other words, under what conditions will

? In other words, under what conditions will

From the definition of  ,

,

This will occur when for all n

Now, from the classical trigonometry using  , this requires

, this requires

This equality must also hold for n = 0; thus,

This result substituted into equation (9.221) yields

from which

Thus, the final result is

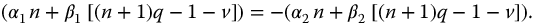

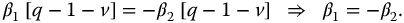

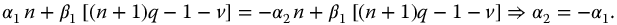

9.8.7.2 The sin(−x) = − sin(x)-Based Identity for Sinq,v(a, α, β, t)

Here, we wish to find conditions under which

From the definition of  ,

,

Considering the sine arguments

This equality must also hold for n = 0; thus,

This result is now substituted into equation (9.226) giving

Combing the argument result with the sign change for  yields the final result

yields the final result

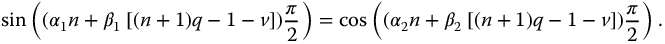

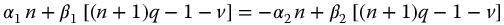

9.8.7.3 The Cosq,v(a, α, β, t) ⇔ Sinq,v(a, α, β, t) Identity

Selected arguments of the classical cosine and sine functions in the  - and

- and  -functions also lead to identities. For this study, we consider

-functions also lead to identities. For this study, we consider

and

Then  when

when

From the classical trigonometry (equation (9.217), we have  , where

, where  . Applying the identity to equation (9.230) gives

. Applying the identity to equation (9.230) gives

Comparing arguments

Again, the relationship must hold for n = 0; thus,

This result substituted into equation (9.232) yields

Thus, the resulting meta-trigonometric identity is given by

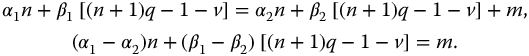

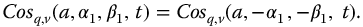

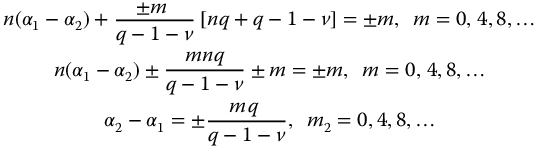

9.8.7.4 The sin(x) = sin(x ± mπ/2)-Based Identity for Sinq,v(a, α, β, t)

For  , identities will occur when

, identities will occur when

Based on the definition of  ,

,

We require

Here, from equation (9.217), we use the identity  , where

, where  ; thus,

; thus,

Comparing arguments

Since the relationship must also hold when n = 0,

Substituting equation (9.240) into (9.239) gives

Thus, we have the identity

Clearly other, possibly stronger, identities of this type are possible. Importantly, because the series defining the parity functions also contain integer-order sine and cosine terms, similar identities may be created for them. Continuing from Ref. [83]:

9.9 Fractional Poles: Structure of the Laplace Transforms

Consider the Laplace transform of the Covibration function. From equations (9.72) and (9.71), we have

This can be further resolved to

From the transform pair (equation (244), it may be seen that the  may be composed by a weighted sum of four R-functions or four complex fractional poles. The transforms of all of the fractional meta-trigonometric functions may be similarly decomposed.

may be composed by a weighted sum of four R-functions or four complex fractional poles. The transforms of all of the fractional meta-trigonometric functions may be similarly decomposed.

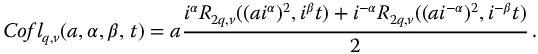

9.10 Comments and Issues Relative to the Meta-Trigonometric Functions

The previous sections of this chapter have presented the definitions, Laplace transforms, special properties, and identities for the meta-trigonometry based on the fractional exponential function,  . From these meta-definitions and properties, the analyst may specialize the variables q, v,

. From these meta-definitions and properties, the analyst may specialize the variables q, v,  , and

, and  to obtain particular fractional trigonometries or hyperboletries. The same variables substituted into the meta-transforms, meta-identities, and so on will yield those transforms and identities specialized to the particular fractional trigonometry.

to obtain particular fractional trigonometries or hyperboletries. The same variables substituted into the meta-transforms, meta-identities, and so on will yield those transforms and identities specialized to the particular fractional trigonometry.

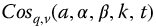

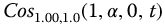

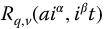

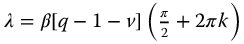

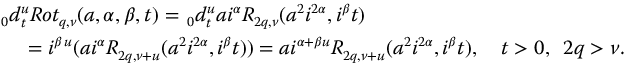

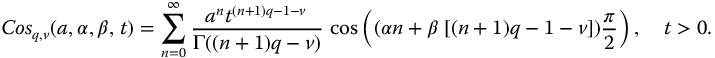

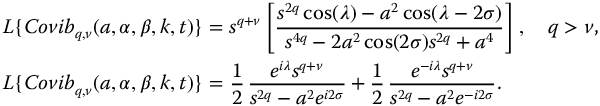

The mathematical process that was used to generate the meta-functions is shown graphically in Figure 9.53. The a and t variables of fractional exponential function,  -function expressed in series form, are generalized to the complex forms shown in the level 2 box. Two paths are shown from level 2 to level 3. The left path takes the real and imaginary parts of the series while the right path takes the even and odd powered terms of the series. From level 3 to 4, following the left path, four new functions are generated by taking the even and odd powered terms of the cosine and sine series. Following the right path, the same four functions may be generated by taking the real and imaginary parts of the complex corotation and rotation functions.

-function expressed in series form, are generalized to the complex forms shown in the level 2 box. Two paths are shown from level 2 to level 3. The left path takes the real and imaginary parts of the series while the right path takes the even and odd powered terms of the series. From level 3 to 4, following the left path, four new functions are generated by taking the even and odd powered terms of the cosine and sine series. Following the right path, the same four functions may be generated by taking the real and imaginary parts of the complex corotation and rotation functions.

Thus, the process described produces eight functions, six of which are real, and the complex corotation and rotation functions. It is noted that at level three, the leading term of the Laplace transform denominators is 2q while at level four it doubles to 4q. It is noted that the mathematical process observed here is fractal and may be repeated indefinitely to finer and finer resolution of  .

.

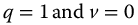

9.11 Backward Compatibility to Earlier Fractional Trigonometries

The generalized fractional or meta-trigonometry as defined here contains both the R2 and R3-fractional trigonometries discussed previously. For example, to obtain the R2-functions, we need only set  and

and  in the meta-functions; that is, the basis for the trigonometry is

in the meta-functions; that is, the basis for the trigonometry is  . Similarly, for the R3-trigonobolic functions, we set

. Similarly, for the R3-trigonobolic functions, we set  , giving the basis

, giving the basis  .

.

The generalized R1-trigonometry is not, however, directly compatible with definitions forwarded for the R1-trigonometry, which was conceived prior to the generalized theory. However, the principal R1-trigonometric functions are compatible with the meta-trigonometry. It is noted that both versions have the basis  .

.

The choice q = 1, v = 0,  , and

, and  will yield the functions and identities associated with the classical trigonometry (albeit with new names).

will yield the functions and identities associated with the classical trigonometry (albeit with new names).

The Covibration function is the real and even part with respect to the powers of a of  and, therefore, is a proper successor to the cosine function of the classical trigonometry and the Flut function is imaginary and odd part with respect to the powers of a and, therefore, is an appropriate successor for the sine function. Thus, the

and, therefore, is a proper successor to the cosine function of the classical trigonometry and the Flut function is imaginary and odd part with respect to the powers of a and, therefore, is an appropriate successor for the sine function. Thus, the  -function in the meta-trigonometry is only the real part of the

-function in the meta-trigonometry is only the real part of the  -function and

-function and  is only the imaginary part of the

is only the imaginary part of the  -function; that is, the parity operations have not been applied. The taxonomy chart of Figure 9.53 illustrates the relationships.

-function; that is, the parity operations have not been applied. The taxonomy chart of Figure 9.53 illustrates the relationships.

9.12 Discussion

The meta-trigonometry expands the fractional trigonometries and fractional hyperboletry from the four bases of Chapters 5–8 to the complete infinite set. The defined functions are useable for the study of many dynamic processes and for the solution of many classes of fractional differential equations via the Laplace transforms of the meta-functions. Considerable study will be required to determine which of the bases are important and where they may be applied. While the fractional trignoboletries release us from the constraints associated with the unit circle, many challenges must be met for the area to develop to mathematical maturity, some follow.

The foregoing material has only dealt with the primary functions:  ,

,  , and so on. The ratio and reciprocal functions (i.e., tan, cotan, etc.) associated with the six primary functions still need to be defined and to have their properties developed. The task is daunting as there are 36 such functions. The next chapter provides some thoughts on this topic.

, and so on. The ratio and reciprocal functions (i.e., tan, cotan, etc.) associated with the six primary functions still need to be defined and to have their properties developed. The task is daunting as there are 36 such functions. The next chapter provides some thoughts on this topic.

Development of inverse function definitions (in series form) is problematic since in most cases no repetitive principal cycle exists, and the inverse functions are one-to-many mappings. Software methods, however, may allow us to temporarily bypass this step for practical application. A more detailed discussion of this topic is found in Chapter 20.

The existence of orthogonal function sets outside of the classical trigonometry will need to be explored. Furthermore, will the classical definitions of orthogonality be adequate or will new fractional-based definitions be needed?