CHAPTER 4

Schleswig-Holstein

‘Linksliberalismus’ one step to the right

Reich on the rise

Compared to Sweden, the institutional and organizational framework of the first all-German elections was different in several ways. First of all, the two-tiered structure of provincial diets and a national assembly made political life more diverse. Furthermore, all elections from 1871 onwards were held against a background in which party organizations, however flimsy, were a political reality, not something which had yet to be created. Indeed, the two most important parties, the Progressives (1861), and the National Liberals (1867), had already formed on the basis of the dominating factions in the Prussian ‘Landtag’. Similarly, the Schleswig-Holstein liberals had, as previously pointed out, organized independently, in 1863, in the ‘Schleswig-Holsteinische Landespartei’ under Wilhelm Beseler; a faction which eventually turned into the left-liberal LPSH/F of Albert Hänel.

As far as left-liberalism in Schleswig-Holstein is concerned, a regular party thus appeared earlier compared to Värmland. Neither was this the result of initiatives at central level. The organization of the left-liberals in Schleswig-Holstein developed parallel to that of the Prussian Progressives, and the LPSH/F remained more loosely integrated with the national organization of the former for most of the period considered. This structure was an effect of the federalistic make-up of the empire with its many, competing regional identities. In fact, the Schleswig-Holstein left-liberals had originally refrained from joining the Prussian party organization simply because the latter had been in favour of annexing the region in 1866 (Schultz Hansen 2003: 465–66). Therefore Lipset & Rokkan’s (1967) observation that modern European party systems were formed on the basis of a merger of competing, regional elites is very applicable to the German pattern. One difference between Germany and countries such as Sweden or the Netherlands was that these rifts in the political fabric of the emerging nation-states were never properly mended. Rather, to many Schleswig-Holsteiners incorporation with Prussia simply meant the introduction of higher taxes and a new, military element hitherto unknown to local society.

Integration of the new Germany into a consolidated political community in the decades to follow, for instance by means of notions such as ‘Heimat’, was achieved only to a certain extent with respect to the establishing of party systems. While keeping some distance to more radical, autonomist factions, such as the Particularists, the Schleswig-Holstein liberals in LPSH/F had close links to the Progressives from 1870, and even managed the inclusion of the ‘Liberale Vereinigung’ (national liberal secessionists) in an alliance in 1884. Despite this coalition, which eventually broke up in 1893, the two party organizations of LPSH/F and the Progressives still remained formally independent of each other up to 1910 (Thompson 2000: 296). Instead of an integrated left-liberal organization, alliances of this kind became a second best option to manage electoral mass-mobilization, and the strategies of obstruction aimed at them by the conservatives and Bismarck in particular.

Originally, new elections to parliament were scheduled for every third year and, after 1888, every fifth year. Among these I have targeted the 1871, 1884, 1898, 1907, and 1912 campaigns as being of particular interest. They bring out another important feature of German liberal parties–but also an important similarity with Sweden–i.e. the circumstance that the parties to a great extent continued to operate by means of proxy. In 1871, liberal opinion in Schleswig-Holstein was put to a first, crucial test during the nationalist fervour that surrounded the ending of the war with France, and the proclamation of a unified Germany. Indeed, even in Schleswig-Holstein, traditionally in favour of autonomy, the Franco-Prussian war had, as we remember, provoked patriotic outbursts, as illustrated by the adolescent Ferdinand Tönnies (chapter 2). Importantly, his case reflected more than just youthful excitement. It also captured the tensions typical of German liberalism, vacillating between different strands of individualism and various old and new modes of collective identification, in the latter case nationalism. Although the nation-state undoubtedly was the result of socio-economic modernization, this was not necessarily the case with the ‘nation’ itself, according to what Tönnies later wrote in his famous treatise on ‘Gemeinschaft’ and ‘Gesellschaft’.

Similarly to the notion of ‘Heimat’, the ‘nation’ was ultimately an expression of ‘natural will’ rather than the product of a modern, ‘rational will’. It drew on ideas of archaic, more genuine and, perhaps, even arcane bonds between people. We need only consider Tönnies’ opinion of the ‘common people’, viz. those among whom the fulfilment of life depended on life among family, friends, and neighbours ‘in home, village and town’ (Tönnies 2001 [1887]: 173):

if the common people and their labour become subject to trade or capitalism, beyond a certain point they cease to be a people or nation. They adapt themselves to alien influences and conditions and become “civilized”. Science, which is really the province of the educated, is continually fed into them in various forms and combinations as a medicine to cure their boorishness (Tönnies 2001 [1887]: 174).

In regions such as Schleswig-Holstein, always a major source of inspiration for Tönnies’ sociological thought, and a region in which, congruous to Värmland, local culture revealed both parochial as well as modernizing traits, these tensions became particularly obvious during the last decades of the nineteenth century.

The complex ethnic and linguistic make-up of Schleswig-Holstein also added to emerging modes of political behaviour and nation-building. On the one hand, insufficient organization and emigration had, by the time of the First World War, pushed the demographic boundary between Danes and Germans further north into Schleswig. On the other hand, ethnic tensions increased with the attempts of forced assimilation and the countermeasures adopted by the Danes (Schultz Hansen 2003: 476–83). Among other things this presented the established parties with an important electoral group which could not be absorbed along conventional lines of issue aggregation and societal representation, to follow Gunther and Diamond (2001). The very same ethnic tensions simultaneously provided sustenance to the Danish lists in the general elections. All the way up to the last pre-war elections in 1912, the first constituency of Hadersleben-Sonderburg continued to send Danish deputies to Berlin (Schultz Hansen 2003: 464).

Economically, as well, Germany was a land of striking contrasts between industrial districts and rural areas. In addition, the agricultural sector as such was quite diverse, a feature which came to colour the debates on tariffs from the late 1870s onwards. Whereas grain-producing areas were more inclined (although not always) to accept tariffs, farmers who were heavily involved in the production of livestock turned more easily towards the free trade camp, since their domestic markets were less vulnerable to foreign competition, and since tariffs meant an increase in prices of fodder. The latter became typical of Schleswig-Holstein, although the issue was not in itself decisive for the political orientation of the farmers. In fact, Thompson suggests that any stress put on the free trade argument would be ‘simplistic’ and ‘at odds with the political situation in the province’ (Thompson 2000: 293–94, quote at 293).1 More specifically, taking stock of this ‘political situation’ implies assessing the autonomist and regionalist traditions prevalent in Schleswig-Holstein throughout the period in question (see below). Moreover, once tariffs had been implemented, it became politically impossible to argue in favour of a complete turnaround on the matter. Thus the extent of the system rather than the principle of tariffs came under debate.

More importantly, however, the ‘Second Reichsgründung’ spelled more than just controversies over protective duties. Tariffs were a symptom rather than a cause of Bismarck’s ambitions finally to crush the opposition in parliament, and in particular the liberals; to stem the rising tide of social democracy and to consolidate the new state by means of a series of administrative, fiscal, and commercial reforms. The most important consequence as we approach the 1880s, therefore, was the end of a liberal era and the emergence of a more authoritarian phase in German domestic political life (Sheehan 1978). Effectively, the liberals were shattered as a result of Bismarck’s policies and the 1884 elections were one pertinent illustration of this–but not in Schleswig-Holstein, where not least the left-liberals fared much better compared to the national average. National liberals and left-wing liberals together received a total of 62.1 per cent of the votes in the region compared to a 36.9 per cent national average (Table 2, chapter 1).

However, the pressure exerted from the right only represented one out of two extremes in the liberal dilemma. The following period, mirrored by the 1898, 1907, and 1912 elections, was when the social democrats gradually came forward as the largest faction in parliament. It was also a period during which Schleswig-Holstein to an increasing extent became industrialized. Whereas Schleswig-Holstein at the time of its incorporation with Prussia was overwhelmingly rural and agrarian, by the end of the First World War one-third of the population lived in industrial cities and towns such as Kiel, Altona, Flensburg, Neumünster, and Wandsbek (Ibs 2006: 129). For instance in Flensburg, in 1895, the Socialist Workers’ Association there had numbered only 222 members, but by 1912 the number had swollen to 1,788, including 263 women (Pust 1975: 144). Not only the urban environments were transformed by this development. It was also reflected in an increased political awareness among the rural workers. Class-based political cleavages came to the fore.

As Schleswig-Holstein simultaneously retained much of its rural character, the dual challenge of national unification and socioeconomic modernization provided fertile ground not only for the rise of ‘Heimatkunst’ but also for the emergence of new political divisions. In a sense these were more complex in their make-up compared to those involved with the emerging party system in Sweden. In brief, not only were the liberals more severely faction-alised compared to Sweden; they also faced organized socialism at a much earlier stage in the election campaigns. Finally, throughout the period the conservative, Prussian royal administration in itself posed a major obstacle. Yet, both the 1907 and, in particular, the 1912 elections signalled a left-liberal comeback, judging from the turnout. The left-liberals somehow managed to defend and reinforce their traditional position as a main political force in the region, despite hapless organization. One key to understanding their dominance was the deeply rooted fear of socialism and revolutionary upheaval; another was the design of the electoral system; a third explanation was, however, the left-liberal influence among the peasantry, fragile as it nevertheless proved to be on many occasions.

To begin with, this ‘peasantry’ was much more diverse in its composition than in Värmland, where small-scale family farmers formed a dominant group. The western districts, by the North Sea, were traditionally home to groups of independent farmers (such as Tönnies’ family), which, historically speaking, had been able to maintain their freeholding liberties and features of self-government all the way up to the Prussian annexation. It was a bucolic yet dynamic environment which produced not only the father of modern German sociology, but also the famous historian Theodor Mommsen, who was born in Garding, Eiderstedt. These areas specialized in rearing beef cattle on large farms with the help of hired labour. Politically speaking, farmers and labourers were divided between, on the one hand, national liberals and conservatives and, on the other hand, left-liberals. The mid-section of Schleswig-Holstein was characterized by backward, small and middle-sized farming, where the so-called ‘Geestbuer’ (‘Geestbauer’) tilled the sandy soil and were involved in a mix of grain and cattle production; political opinion was inclined to the left. The east, finally, was generally speaking dominated by large manors but also well-to-do tenant farmers, diversified in terms of production, and dependent on the labour of cottagers and day-labourers. As in the west, political opinion reflected the socioeconomic cleavages in the area: estate owners followed conservative tradition, whereas labourers, tenants and small farmers had liberal and, increasingly, socialist convictions (Tilton 1975: 20–29).

Since liberal leadership in the region at the same time was overtly urban and academic in composition, the urban–rural division was a defining characteristic of the movement (Beyer 1968; Thompson 2000) in much the same manner as in Värmland. Important differences, though, were that the economically dominant groups of farmers were much more volatile, politically speaking, and, eventually, also much more prone to support right-wing parties. Precisely in this dimension, the liberal flaw of weak formal organization proved fatal in the long run. This became obvious not least once universal suffrage was introduced in 1918. As Tilton points out (1975: 10–11), one should therefore also consider that, despite the more generous electoral laws compared to Sweden, these still excluded a majority of the adult population before the First World War. Neither women nor men under the age of 25 had the right to vote; thus, at the time of the 1874 general elections still only a fifth of the population (21.2 per cent) were eligible to vote.2

The 1871 elections

The likely results of the first all-German elections, scheduled for March 1871, were not entirely promising from a liberal point of view. One week before the proclamation of the German Empire, in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles on 18 January, Keiler Zeitung commented at some length on the issue. Citing an article in the Trier-based Volksfreund, a newspaper with close ties to the newly established ‘Zentrum’ party, the time chosen for the elections seemed not only unfavourable but virtually impossible to the liberals. Indeed, many among the electorate stood fully armed in France while the election campaign back home was about to take off. Of these, the best and brightest among the younger generation, a majority were potential liberal voters. Looked at the other way around, the Kieler Zeitung questioned whether political conservatism really was the certain outcome among voters as they grew older. But although there was reason for concern, considering the gravity of the situation, the election also represented an opportunity to steer the new nation down the right tracks of constitutionalism. According to the newspaper, the context of the election if anything highlighted the need to de-militarize German society, including, if possible, a shortening of the three-year conscription.3

The assumptions made as to the connection between age, voting, and military service, however, must be understood in light of the following: conscription applied to all men of military age, i.e. from the age of 20, but given the restrictions built into the electoral system the issue of voting still remained a purely theoretical matter to these groups of young men. What the Kieler Zeitung obviously referred to, then, were the large cadres of reserves which also made up the army. Furthermore, to a left-liberal ear the risks of ‘militarization’ of society could be read not only in terms of a devaluation of civic values through the extended military service of its citizens; in any event this feature became more prominent only after 1871, when it reflected, among other things, in a rapid growth of veterans’ associations and various military clubs. ‘Militarization’ could also be defined in budgetary terms, as ‘high taxes and potentially unchecked state expenditure’ (Clark 2006: 599). All in all the newspaper conceded that the task lying ahead was a formidable one, since the election was hampered not only by the war, but also by the restrictions imposed on the press and on civil liberties, such as the freedom of assembly.4 These were features which quite naturally complicated campaigning.

The newspaper captured several of the main points of the LPSH/F programme which had been launched in May 1870, viz. the peaceful uniting of north and south Germany, cuts in military expenditure, a halt to tax rises, extended civil rights, and self-government. On the issue of northern Schleswig, with its Danish population, the position was also clear: it must at all costs remain an integral part of the region and should not be ceded (Kiehl 1966: 28–31). Apart from the paragraph on northern Schleswig, this programme was roughly in line with the demands previously adopted by the Progressives in other regions, such as Württemberg (the latter related in Eisfeld 1969: 203–204). Differences between parties and factions, though often blurred and confusing, were thus more contingent on a combination of doctrine and party programmes rather than opinions on singular issues, the latter being the case in Sweden during this period. Ideology had made its way into politics, albeit it would often be harnessed by pragmatic considerations in the years to follow. Electoral competition on the basis of party programmes and, simultaneously, restriction of the press and lack of civil liberties was, however, only one feature which made campaigning different compared to Sweden. A third difference still was the very design of the electoral system (see Diederich 1969).

Apart from what has already been said about the restrictions surrounding the right to vote, neither did the electoral system favour the formation of centralized parties. Rather, historically speaking, electoral systems based on single-member constituencies and majoritarian elections usually favoured local or regional elite factions (chapter 2), the latter a prominent feature of political culture in Schleswig-Holstein. At the same time, however, the German system also had positive features. Most notably Suval (1985) has argued that the electoral system was, indeed, inclusive enough to facilitate at least a certain amount of group-specific identification among the voters, based on party affiliation and voting practice. The German social democrats are a strong case in point. Among the positive features, later noticed by among others the Swedish liberals, were also direct elections and the principle of absolute majority (chapter 5).

Whether Suval’s reasoning applies to the much more heterogeneous groups of voters that made up the liberal parties is questionable, though. Confirmation of the rules of the political game by means of the electoral system and, at the same time, affirmation of one’s own interests does seem a process based on principles similar to those suggested by Ostrom (1990). However, the electoral system was only one, if crucial, component of this structure. Compared to the social democrats the liberals lacked important features, and more specifically organizational arrangements and party institutions, on the foundations of which ideological identity and issues could be properly negotiated. Quite naturally this left less room for the liberal parties to perform functions of societal representation and social integration (cf. Gunther & Diamond 2001). We need only in this context consider the organization created by LPSH/F in 1867, which included a general assembly and an executive committee of seven persons, assisted by local representatives, but sparsely so in the countryside (Kiehl 1966: 23–25; Thompson 2000).

Local ‘Wählervereine’ (electoral assemblies) added to this structure, as in Sweden, but these were nevertheless separate entities in relation to the party organization. Any bodies corresponding to the network of local party branches in Sweden were virtually non-existent. Therefore the Schleswig-Holstein liberals were almost certainly less successful in organizing their voters compared to what was the case in Värmland: as late as 1911, the left-liberals had succeeded in enrolling only 5.0 per cent of their supporters (Schultz Hansen 2003: 473). Indeed, they were worse off in this respect compared, most notably, to the left-liberals in Baden, who organized about one-third of their supporters at the same time. Yet, more than Baden, Schleswig-Holstein was typical of the average German organizational pattern amongst the liberals (Thompson 2000: 281–82). Also, the system of second ballots made what were already fragile party alignments even more volatile among the liberal factions. In addition, candidates in the elections were not required to reside in their respective constituencies. This may certainly have provided an antidote to parochial elitism, but at the same time it also widened the gap between voters and their parties in cases–such as with the liberals–where there was no organizational or ideological cement with which to bond grass roots and leadership together.

Against the left-liberals stood the national liberals and, increasingly so, the socialists. When the 1871 elections were announced, the latter had begun to pose a real threat to the established political factions. Contrary to what became the case among some of the Swedish liberals when the franchise movement formed in the early 1890s, the German liberals never seriously contemplated any form of cooperation with the socialists; that they did try to sway the workers by addressing the social issues of emerging industrialism, such as at a national liberal meeting in February 1871, is another matter.5 Neither did any of the centre-left parties have any illusions about a grand left-wing coalition.

Campaigning in strategically targeted areas, such as the western parts of the province, and organizational resolve was part of the socialist strategy (Regling 1965). This was an endeavour that was only fuelled by the introduction of Bismarck’s Anti-Socialist Laws a few years later. By the time of the First World War, the remarkable effort made by the German socialists had, in the words of Watt (1968: 114), resulted in a strong, working-class sub-culture of its own: ‘The Social Democrats had given to him [the worker] his own fraternal and sports organization, his own singing groups, and clubs for his wife and his children. He could read any of more than ninety Social Democratic newspapers, led by the vigorous Berlin daily Vorwärts.’ In contrast to the liberals, therefore, they had successfully managed to become a mass party, including efficacious institutional arrangements for interest aggregation, issue structuring, and mobilization. By that time the social democrats had organized from 12.8 to 52.6 per cent of their voters in Schleswig-Holstein, depending on constituency (Thompson 2000: 282).

By the 1870s the socialists were quite well aware of their potential. For example, they did not hesitate to strike a messianic chord when appealing to the voters; and, in fact, such allusions were all the more important to campaigners operating in strongly religious environments. It was, as Regling (1965: 159) points out, not unusual to compare Ferdinand Lassalle, the late founder of the ‘Allgemeine Deutsche Arbeiter-Verein’ (ADAV, 1863), to Christ, in order to justify the gospel of socialism and, slowly, make it a replacement for religion. In connection to the 1871 elections, therefore, the socialists introduced themselves to the voters in the eight Altona-Stormarn constituencies (Holstein) with help of a motto coined by Lassalle, i.e. that ‘the worker is the rock, upon which the Church of our time will be built’.6 Such confidence was, at this stage, direly needed since the strength of socialism, however threatening from the point of view of the establishment, still left a lot to be desired. Hence the fears of the Prussian government, too, concerning the socialist ‘menace’ in the province, were rather exaggerated. In Rendsburg, northern Holstein, for instance, ADAV had, indeed, a local assembly, but in the early 1870s it still included only a limited number of active members, and they led a rather quiet life as far as politicking was concerned (Regling 1965: 122–23, 172–73). Among their activities were commemorative celebrations of Ferdinand Lassalle’s birthday.7

During the 1865–70 period ADAV managed to extend its activities across the whole of Holstein, and for the voters, the Altona-Stormarn appeal claimed, a great moment had now arrived. The workers were now about to elect their very own representatives to parliament. In contrast to Bismarck’s contempt of parliamentary procedure and protocol, the appeal stressed that the deputies represented and exercised the ultimate legislative power of the Reich (reflecting the more positive appreciation among the Lassallean socialists of the state and its institutions, compared to more orthodox Marxists). And not only that: parliament was, indeed, also ultimately responsible for the implementation of this legislation.8 In matters constitutional the message was therefore in a sense comparable to that of Albert Hänel and, thus, the left-liberal position. Political power was to be wielded by the people through their elected parliamentary institutions. At the same time a major difference compared to the liberals was, of course, the attacks made on capitalism and the explicit ambition to unlock the doors of parliament to deputies recruited from the working classes, not only their alleged representatives from the established political elite. Socialist policy posed a threat not only to the creed of the ‘invisible hand’, typical to economic individualism, but also to the liberal ambition to be the vanguard of the working classes by means of example and cross-class alliances. Indeed, one could therefore say that the 1871 socialist programme in a sense spelled the demise of a liberal era in German politics a few years later, during the ‘Second Reichsgründung’, although this was an end that, somewhat paradoxically, was to come about not because of socialist campaigning, but rather as a result of Bismarck’s determination to rout the liberals.

The Danish issue, viz. Northern Schleswig, as well as lingering separatism among the German population, also complicated the election campaign. Difficulties faced by the parties pertained above all to the dual differentiation of the voters by socio-economic and ethnic identification. For instance, since the Danes entered the elections on the basis of their own candidates, campaigning among them was considered a lost cause from the outset by the liberal and right-wing parties. Eventually the Danes also won the Hadersleben-Sonderburg constituency in the northernmost part of the province (Schultz Hansen 2003: 464), and although the national liberals secured the second, Flensburg-Apenrade, constituency they met significant resistance from the Danish candidate, farmer H. A. Krüger from Bestoft. Krüger, in turn, had been nominated by among others Gustav Johannsen, a bookshop owner in Flensburg, who would himself become a popular name among the Danes but also many German voters in the following elections.9

As for the particularists, they, too, blurred the political front lines among the liberals. One case in point is the non-socialist workers’ association in Schleswig, which decided to nominate a secessionist (particularist) candidate, Count Eduard von Baudissin, whereas the local ‘Bürgerverein’ favoured the national liberal candidate Theodor Reinke.10 Certainly, Schleswiger Nachrichten, which supported Reinke’s candidacy, was blunt as to the prospects of Baudissin: these were ‘now, as before, completely lost’.11 This statement, however, underestimated the strength of particularism in the constituency, since Baudissin carried the day by 3,776 votes to 2,282 for Reinke.12

The press, therefore, however crucial to campaigning, was on occasion well off-target when assessing the public climate. As for the organizational proxies of the parties, these usually continued to be modelled on the ‘classic’ pre-1848 patterns of middle-class association. They included most notably the ‘Bürgervereine’ and different kinds of cultural societies including, particularly in northern Schleswig, nationally orientated ones such as the ‘Harmonie’ society in Flensburg. In this case the association simply shifted from a pro-Danish to a pro-German position after 1867 (Kretzschmer 1955: 282). In yet other cities, such as Hamburg, some of these citizens’ associations were eventually attached to party organizations (Thompson 2000: 283), but this was far from always the case. Equally often their efforts resulted in some confusion on matters political, which only goes to show the malleability of ideological affiliation and the narrow distinction between ‘civic’ and ‘political’ association.

As a case in point, Reinke’s and, in particular, Baudissin’s candidacies in the 1871 elections pose two examples of the ambiguous role played by civic association in relation to political association: a formally non-political assembly, a workers’ association, chose to take a clearly political position with respect to the legal and administrative status of Schleswig-Holstein in relation to Prussia. The case of J. Pauls in Bredstedt, in the fourth constituency of Tondern-Husum-Eiderstedt, who eventually declined nomination, is another example. In his case the platform was an anonymous ‘Delegiertenversammlung’, and not one of the regular liberal electoral assemblies.13 Yet a third example was the society of the ‘Schleswig-Holsteinischen Kampfgenossen’, which convened in Itztehoe.14 Associations such as these did, however, not only intervene in the nomination procedure, by screening and putting forward possible candidates. Whether successful or not, they also helped disseminate ideas and created opinion on current issues, such as on the matter of the infallibility of the Pope,15 declared by the Vatican in the previous year–a matter of no small importance in the subsequent unleashing of Bismarck’s ‘Kulturkampf’. Although Catholicism was of no particular relevance to political conditions in Schleswig-Holstein per se, generally speaking anti-Catholic sentiments, often deeply rooted (Gross 2004), were still emblematic to post-1870 German liberalism.

In regard to the role played by the newspapers, and in particular the Kieler Zeitung under the aegis of Hänel’s close ally Wilhelm Ahlmann, as well as considering the use of proxies, the 1871 campaign reveals certain similarities to the pattern typical in Värmland and Sweden. Other similarities included appearances by individual speakers, seen as crucial to electoral mobilization. In fact, the paramount importance of this feature was almost certainly due to the poor organization among the liberals; left-liberals and national liberals alike. Canvassing, though, does not seem to have been a regular part of campaigning; something which, again, was hardly surprising considering the limited financial resources of the parties. Finally, as in Sweden, the campaign was also of relatively speaking short duration. It took place in the last couple of weeks, or even days, before the actual elections. One exception was the nomination of Albert Hänel, in early February, first by the local electoral assembly of LPSH/F in Kiel, later by the electoral assembly in the seventh constituency of Kiel-Rendsburg. In the opinion of the Kieler Zeitung, Hänel, who since 1867 was a deputy to the parliament of the North German Confederation, was the man best suited to avert any tendencies towards factionalizing within the party.16 One such source of factionalism, indeed, was represented by the particularists, including names such as Baudissin, who had left the main party only recently and, at about the same time as Hänel received his nomination, convened at a rally in Rendsburg,17 precisely where the provisional government of Schleswig-Holstein had once been formed in 1848.

As stands clear from evidence, factionalism was very much part of the elections. Also, there was the competition not only from the socialists but also the national liberals and the conservatives to consider. In the long run, and in part as a result of the system of second ballots, the left-liberals and the particularists were forced to join forces in some constituencies, since neither of the candidates of these parties was able to collect enough votes in the first round of the election. All in all this reflected what gradually, in the years to follow, became the hallmark of Hänel’s policies, viz. an ambition to always manoeuvre between the Scylla of liberal factionalism and the Charybdis of socialism.

Albeit at the expense of ideological clarity, this strategy proved successful in yet other respects. Joining together particularist candidates and the LPSH/F secured mandates in seven out of nine constituencies, i.e. all except Flensburg-Apenrade and Hadersleben-Sonderburg (Schultz Hansen 2003: 464). Lauenburg, where the national liberals also won, was not administratively joined with the region until 1876 and then formed a tenth constituency. The outcome stood in stark contrast to most other regions. There the national liberals generally achieved a better turnout compared to the progressives (Sheehan 1978: 125, Table 9.1). Indeed, the left-liberals received a national average of only 16.0 per cent, compared to 30.1 per cent for the national liberals,18 the single biggest faction in parliament. Also, the threat posed by the socialists was contained, although tobacco worker Carl August Bräuer, the social democratic candidate in the eighth constituency, made it as far as the second ballot.19 This circumstance nevertheless spelled important changes which were to occur in connection to the next, 1874, elections, when not only the national liberals advanced their positions at the expense of the left-liberals, but also the social democrats secured two deputy posts, one for Altona-Stormarn outside Hamburg, and, following massive campaigns, one for the ninth constituency. This area included the Segeberg district, which was traditionally dominated by the liberals (Schmidt 1985; Schultz Hansen 2003: 464).

Which features did, after all, make the liberal mode of mobilization by means of weak organization and proxies work? Liberal doctrine, as reflected in the party programme, was certainly important, although it included pragmatic concessions which were not necessarily intrinsic to liberalism as an ideology. This is illustrated by the stress put on the integrity of Schleswig-Holstein as region in the 1870 programme. On the one hand, this item could certainly be read as an appeal to the idea of the right of self-determination. On the other hand it could, however, also be understood in terms of unchecked parochialism, and simply as a conservative reaction to modernization, its foundations being not entirely unlike the kind of belief system Tönnies (2001 [1887]) found typical of pre-industrial communities. What still made this paragraph appealing to left-liberalism was the federalistic framework of the German nation-state which, in turn, could be used to link the idea of liberty with regionally embedded notions of ‘Heimat’.

Regardless of its status as a ‘Honoratiorenpartei’ or ‘Professorial party’, the LPSH/F therefore made a serious attempt to channel public opinion on the matter of regional identity. Not least Albert Hänel was repeatedly accused of intellectual aloofness (see below), but regional pride and independence still became regularly exploited by the party in the following election campaigns. But nevertheless the role of the party elite, as opposed to the structures typical of ‘Frisinnade landsföreningen’ in Sweden, must be stressed. For all its shortcomings the latter left ample room for grass-roots opinion to be funnelled directly into parliament. In addition, the fact that the proxies used by the left-liberals in Schleswig-Holstein, unlike the Swedish popular movements, lacked the properties of mass organizations further helped to narrow the organizational basis of the LPSH/F. Consequently, Duverger’s notion (1967 [1954]) of parties with intra-parliamentarian roots fits better, if not entirely, as a description of left-liberalism in Schleswig-Holstein than of conditions in Värmland.

As in Sweden, albeit for partly different reasons, the left-liberals in Schleswig-Holstein failed to institute organizational mechanisms securing commitment, transparency, and accountability in a manner that facilitated trust in the party among its heterogeneous groups of followers (cf. Ostrom 1990). Similarly, too, doctrine never seems to have been substituted for formal organization as the cement of social cooperation. Despite rhetoric, political pragmatism and alliances between the elites of the competing factions remained more important factors to the structuring of left-liberalism. When we add to this the particularistic, ethnic, and socio-economic realities of Schleswig-Holstein, the success of liberalism appears all the more enigmatic. Which factor could span the classic urban–rural divide within the Schleswig-Holstein liberal movement; a divide further increased by the design of the electoral system and, in our particular case, more sharply drawn because of the divergent positions taken with respect to relations with Prussia?

Again, individualism, although drawn from different sources, provides an important part of the explanation. From that perspective, too, there were both differences as well as interesting similarities compared to Sweden and Värmland. Beginning with the differences, German liberalism after 1848 never seriously attempted the transformation to mass politics in the same manner as the Swedish liberals did; but neither were they forced to do so by mounting pressure from within a framework of regular mass-movements such as in the Swedish case. To begin with, nonconformism failed to spread extensively, let alone make an impact on political life in the same manner as in Sweden: for example, roughly 6 per cent of the population in Värmland was organized in different nonconformist churches by 1905, but around 1910 only 0.3 per cent of the population in Schleswig-Holstein (chapter 2). Neither did mass-based teetotalism, such as the Blue Ribbon or the Good Templars, play any significant social, let alone political, role in German society, although they did eventually spread, primarily in the northern parts of the country from the 1880s onwards. In fact, Schleswig-Holstein and Hamburg became strongholds of the German Good Templars, but even so the movement was numerically weak compared to Värmland, and most likely it became more typical of Danish than German civic associations in the region.

The very first lodge appeared in the Danish-speaking district of Hadersleben, in 1883, whereas the first German lodge followed in Flensburg, in 1887. Ten years later the Nordslesvigs Good Templar reported a total of 48 lodges, which comprised 1,232 members.20 All of the localities mentioned in the material pertained to northern Schleswig, but at the same time the statistics ranged up to lodge no. 64 (the higher the number, the more recent its date of formation).21 This might imply that a further 15 lodges–perhaps German ones –were excluded from the report, closed down, or in any event had failed to submit data. Assessing the level of membership relative to the population as a whole is difficult, but we may remember that in Värmland there were a total of 18,451 organized teetotallers by 1905, 10,520 of whom were Good Templars.22 Also, judging from the issues addressed by the Nordslesvigs Good Templar, the organization was largely non-political, at least up to the turn of the century, contrary to what was the case in Sweden.23

As I have previously stressed, German public life therefore lacked important, mass-based proxies that–and this was the essence of the Swedish popular movements–could function as inroads to political influence and simultaneously help formulate a more widely defined conception of modern citizenship, despite the limitations of the electoral system. Most notably in the case of organized temperance, the brunt of anti-alcohol campaigning continued to fall on the efforts of the state-aligned DV, which, in Schleswig-Holstein around 1900, also included many prominent liberals as members, such as Albert Hänel and Wilhelm Ahlmann.24 Although the DV expressed itself benignly when taking stock of the Good Templars,25 any actual, let alone extensive, cooperation, does not seem to have evolved before well into the twentieth century.26 In addition, whereas for instance the baptists and methodists made some inroads in local society, they do not seem to have been able to penetrate to any significant extent a confessional environment which was dominated by the Lutheran Church and the ‘Innere Mission’. As Hahn-Bruckart notes, they were not particularly successful in transmitting what he depicts as a specifically American nucleus of civil association to German soil (Hahn-Bruckart 2006: 246–49). (Interestingly, the same juxtaposition between ‘American’ and ‘German’ civil society had been made eighty years previously, in an essay by Dr Hans Fraenkel, 1922, when taking stock of the new Weimar Republic in a Festschrift dedicated to the famous liberal historian Friedrich Meinecke; see later in this chapter.)

Instead, religious life was shaped by other influences, and with far deeper historical roots. Unlike Denmark, Germany lacked a Grundtvig, viz. the Danish nineteenth-century theologian Frederik Grundtvig, who successfully reformed the Church along modern lines (see, for instance, Claesson 2003). And unlike Sweden, low church and nonconformist movements were weakly developed. Yet, the same pietistic awakening, originating in Saxony and Prussia, which had swept north, including to parts of Sweden, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, had left an imprint on the social environment of Schleswig-Holstein as well. As in Sweden, where nineteenth-century nonconformist movements represented an alternative path towards the individualization of society, so did pietism in Schleswig-Holstein, historically speaking, exercise the same pressure and, furthermore, on the foundation of non-Enlightenment and non-secular ideas (Hejselbjerg Paulsen 1955; Jakubowski-Tiessen & Lehmann 1984; Weitling 1992). As we have seen in chapter 2, it was the German Enlightenment that took colour from pietism, and not the other way around. Also, similarly to Tocqueville’s observation of the relation between civic association and Protestant dissent in America (1981 [1835–40]; Eckstein 1994), pietism at the same time represented a counterweight to excessive self-interest: it taught that individual experience was crucial both to religious awakening and personal responsibility. In the long run pietism therefore promoted the individualization of society, but individualism informed by a sense of responsibility which, contrasted in particular to the atomized economic individualism of emerging liberalism, put more stress on the role of the individual as part of a community.

The kind of morality that religious awakening aimed at was not alien, for instance, to the ideas underpinning Kant’s notion of categorical imperatives, considering morally just acts among modern citizens, or C. F. Gellert’s conception of individual responsibility. And since pietism had challenged established Lutheran orthodoxy, in the long run it also eroded trust in the official authorities. Paradoxically, it facilitated what eventually became modern and secularized rationalism. By doing so pietism did, in a sense, become a forerunner of Enlightenment ideas and also liberalism. As society assimilated these generally different yet in crucial respects similar strands of thought, they gradually crystallized into various types of civic associations in the cities and towns of Schleswig-Holstein, all according to the middle-class conception of social cooperation founded on individual effort but, simultaneously, closely-knit circles of peers. Not surprisingly, we can note a basic similarity between this way of thinking and acting and Tönnies’ reasoning about the importance of local context to the fulfilment of the ‘common people’ (see above).

Two of the organizational expressions of this aspect of local culture were the ‘Bürgervereine’ and–as in Sweden–the emergence of small savings banks (on savings banks in Schleswig-Holstein, see Kopitzsch 2003: 318–21). Certainly, geographical data should always be interpreted with care, but under any circumstance it remains an interesting coincidence that at least some of the first ‘Bürgervereine’ in Schleswig-Holstein appeared precisely in localities (Flensburg and Husum) where pietism had made strong inroads as far back as the 1670s (Jakubowski-Tiessen & Lehmann 1984: 321–22). Also, pietist centres such as the above-mentioned were among the places where early savings banks appeared; at the same time, though, the very first ones were actually run by reform-minded estateowners in Dobersdorf and Knoop, in the Kiel area (Kopitzsch 2003: 321).

Whether the local peasantry had much to say on the subject of Kantian philosophy, and of categorical imperatives, may remain a matter of dispute; that some of them, indeed, were familiar, for instance, with Gellert and his writings is clear (chapter 2). But the main point is: when traditions such as this merged with a social and cultural environment in which attachment to the land and a deeply-rooted sense of independence, symbolized by the unique position that the province had for centuries upheld against the Danish crown, this could easily result in the peculiar blend of utilitarian individualism, political radicalism, but also conservatism that has been noted by Tilton (1975), Thompson (2000), and others before them. But at the same time, all this also represented a different culture compared to that of Albert Hänel and his colleagues. With or without the help of organizational proxies, electoral mobilization of the rural electorate was not easily coordinated by the parties. In fact, individualism itself among the more well-to-do farmers often hindered organization on an extensive level when it came to interests that extended beyond farm, family, and village community. In the same way as among the Swedish liberals, individualism both stimulated partisanship and became an obstacle to cooperation and collective agency. Also, similar to the situation in Värmland, it was not unusual that the left-liberals had to accept the nomination and election of deputies who were more right-wing than their liking, following the inclinations of the voters. This was a move made to avoid the election of outright conservative candidates or, in more industrialized constituencies, social democrats.

The efforts made by Hänel to secure the re-election of national liberal Georg Beseler, the brother of Wilhelm Beseler (see above), in the sixth constituency of Pinneberg in the 1877 and 1878 elections is a case in point (Beyer 1968: 158–59). This was, as Beyer (1968) noted, a tactic facilitated by the system of second ballots, this system continued to be favourable to the liberal parties during the whole period up to 1914. If liberalism, therefore, turned into a makeshift belief in values and outlooks not easily translated into modern political language and a modern left-right comprehension of society, at the same time it had the ability to appeal to people, since its basic tenets of freedom, self-determination, and individualism were attractive to everyone but, alas, trusted by no one. The clearest example of the latter was the farmers.

As much as the liberal creed of self-determination could easily be appreciated by the farmers, their economic interests were guided by a different rational, which found other outlets than those represented by the liberal parties. The clearest expression of this came in the shape of the ‘Bund der Landwirte’, which was established in 1893. This was an agrarian interest organization sponsored by the conservatives, and with its main basis of operations in central and northern Germany. Among the well-to-do farmers in Schleswig-Holstein, many a voter would still opt for the left-liberals or the national liberals in the parliamentary elections,27 but in matters economic their sympathies often lay elsewhere. Features such as these also explain why the liberals in the region were less successful, compared to Sweden, in integrating the peasantry within the organizational framework of the modern political party. Rather, the fact that the left-liberals remained a force to be reckoned with during the 1880s was in part a result of deliberate organizational changes in the LPSH/F, in part a reflection of the personal leadership skills of Albert Hänel.

Split, merger, and success

A main objective and long-desired goal of Bismarck was to undermine the liberals in parliament (this and the following paragraph, Sheehan 1978: 181–88, 199). Controversies concerning the accountability of the imperial administration to parliament, as well as Bismarck’s proposal for fiscal reform and protective duties, provoked the desired split. The left-liberals became more and more isolated at the same time as the moderate and right-wing elements of the liberal factions were pushed closer to the conservatives. In the spring of 1878, tensions had escalated. The crisis culminated following two attempts to assassinate the emperor, William I. The blame was put on the socialists, since 1875 united in the ‘Sozialistischen Arbeiter-Partei’, when ADAV had merged with a competing faction at the Gotha conference (only with the reorganization of the party in 1890 did the official name of the party become ‘Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands’). In this situation parliament was dissolved and new elections declared. The outcome was a defeat for the liberals–national liberals and progressives alike–and the introduction of the Anti-Socialist Laws. By the end of the year the protectionist programme of the government was consolidated and it was accepted by parliament in the following year, although, in fact, agricultural interests continued to remain uncertain about the usefulness of tariffs.

Principles of free trade were defended by radicals on the left wing with the help of the argument that economic and political freedom, the classic item on any liberal agenda, were too closely connected to be separated in the manner implied by the shift towards protective customs: the right of political representation went hand-in-hand with freedom from economic regulations. The alignment of political individualism and economic individualism was, however, always uneasy and could be criticized for being far too doctrinaire. In effect the 1878–79 events shattered the German left and the liberals in particular. One important result was a general turn towards the right in domestic political life. Another outcome was increased factionalizing among the liberals themselves. As in 1867, when the liberals had split in progressives and national liberals, in turn the national liberals now split on the issue of tariffs. The left-wing faction seceded and formed the ‘Liberale Vereinigung’. As a whole the liberals moved from defeat to defeat in the following 1881 and 1884 general elections, and with national liberalism at the core of the changes. Under the leadership of Johannes Miquel a clear-cut protectionist agenda was finally adopted by the latter in March 1884. In what became known as the ‘Heidelberg Declaration’, the paramount importance of agriculture to the German national economy was stressed.

This was a move which would seem to have made voters in Schleswig-Holstein more susceptible to the National Liberal Party, and less inclined towards the left-liberals under Albert Hänel. This, however, would prove not to be the case. During what was as usual a short campaign–effectively it began in September, and the nomination procedure was completed by early October,28 whereas the date for the elections was set for 28 October–the problem of tariffs, and constitutional as well as social reforms, formed the agenda. Indeed, the last item could not escape political attention,29 since not only did Bismarck try to fight off political radicalism with the help of the Anti-Socialist Laws and a confrontational policy towards the liberals: his move to sway the working classes by proposing state-managed social insurance must also be considered as part of the attempts to wrestle the political initiative from the hands of the opposition. Approval of the package, though, was not unanimous. The initial proposal of 188l, which covered work injuries, had been contingent on centralized control by the imperial administration as well as subsidies by the federal states. It was eventually accepted in 1884, but only on the basis of a less centralized, corporatist structure. In turn the proposal for health insurance for the workers had a less controversial design, whereas that of pensions raised the issue of taxation and, indirectly, state control over society (Edebalk 2003).

Precisely because of factors such as these, the 1884 election campaign to great extent focused on taxation and tariffs. These were considered emblematic of Berlin’s attempts to strengthen its administrative grip on society. On the matter of protective duties, the exchange between left-liberals and national liberals had actually begun the previous year; something which only goes to show how flammable this issue still was, five years after the 1878–79 stand-off between Bismarck and the opposition. Yet for the farmers in Schleswig-Holstein the choice to opt for tariffs was, as I have previously pointed out, far from obvious. Rather, this issue must be understood in light of the ideological and organizational development among the liberals in 1883–84.

In a speech which Hänel addressed to the voters in the seventh constituency (Kiel-Rendsburg) in 1883, he had emphasized the liberal demands for increased civil liberties but also his reluctance about tariffs. These, he claimed, would only benefit big business. He therefore appealed to the common sense of ‘the people’–including the farmers–on this matter, similarly to what would become the case among free traders and protectionists in Sweden only a few years later. In addition, Hänel made clear that he was firmly opposed to any form of ‘factional politics’ (Kiehl 1966: 46–47, quote at 47). Probably this argument was not primarily rooted in anti-party sentiments of the traditional kind, but was a tactic and, in this respect, a reflection of the fear of further faction in connection with the impending elections. Rather, Hänel prepared the ground for the great left-liberal coalition of 1884, i.e. the merger of the progressives and the ‘Liberale Vereinigung’ into the ‘Deutschfreisinnige Partei’. By this configuration the left-liberals tried to ward off the ‘external challenge’ (Panebianco 1988) posed by Bismarck and to unite what remained of the liberal opposition in parliament.

Unlike Eugen Richter, the leader of the progressives, Hänel was therefore not alien to the idea of cooperating with national liberal dissenters. Only in 1884, however, did this become an acceptable solution to Richter. It then emerged as an opportunity to reverse the electoral defeats of 1878 and 1881 by amalgamating the left-liberals with the national liberal dissenters. Based on the alliance between the progressives/LPSH/F and the new ‘Liberale Vereinigung’, Hänel continued to defend his view on tariffs during the campaign. Although sympathetic towards social reforms–but, importantly, based on the self-determination of the workers–he spared no effort in vehemently criticizing the protectionist agenda of the national liberals.

Hänel’s criticism of protective duties was not to remain unchallenged as the general elections approached. The opposition, though, was of a kind which, perhaps, had not been expected. Shortly before the elections, the Schleswiger Nachrichten not only rebuked Hänel’s entire mode of liberalism as being too theoretical and, ultimately, disloyal from the perspective of the Reich‘s interests. Indeed, the newspaper also raised the question whether an issue such as that of tariffs should be politicized at all.30 Two points can be made here. Firstly, viewed from a certain perspective the coalition of interests that made up the ‘Deutschfreisinnige Partei’ could certainly be interpreted as nothing more than just a shrewd attempt at politicking by Hänel and the progressives. In other words, the left-liberals were simply unreliable opportunists. Secondly, however, there was also a more profound meaning to the criticism voiced by the newspaper. Although campaigning had developed in the direction of competition between regular party programmes earlier compared to the situation in Sweden, viz. spelled the ‘politicization’ of politics at an earlier stage, obviously some issues could, given the circumstances, still be considered as being above factional strife.

To begin with, the ideological position of the newspaper itself should be considered. Søllinge and Thomsen (1989: 656–57) describe the Schleswiger Nachrichten as ‘apolitical’, but at least as far as the 1870s and 1880s are concerned this label should more correctly be read as a euphemism for a national liberal bias. Importantly, this also meant signalling a greater degree of allegiance to the new German state and its leadership. Tariffs, having been defined by Bismarck as a reason of state, were by definition above electoral strife. With the help of a slightly Hegelian reading of the kind of relationship between the state and the citizens that this implied, the position of the newspaper could therefore be understood as radical and at the same time informed by the highest of reason–that of national interest. Consequently, the Schleswiger Nachrichten discarded Hänel’s views as being much too aloof to German political logic. More precisely, it suggested that his position was untenable since the left-liberals grounded their reasoning in an economic theory which was basically ‘unsound’, and on the basis of this rejected ‘all practically minded men’ as ‘illiberal’ and ‘reactionaries’.31 In fact, on the contrary, the national liberals and their supporters comprised precisely the kind of ‘practically minded men’ who correctly understood the needs of the country. Hence Hänel’s opponents also tried, more or less directly, to whet the interest of the farmers, practical men as they no doubt were. As Germany rapidly industrialized, so did the market for produce expand, and tariffs, so it would seem, provided the farmers in Schleswig-Holstein, as elsewhere, with valuable protection from outside competition. So the national liberal and conservative arguments read.

This was a position that was anew criticized by Hänel. A week after the remarks made in the Schleswiger Nachrichten, Hänel spoke polemically against government policy and, above all, the national liberal programme. Sceptic towards the German ‘ecstasy’ for colonies, resentful at military expenditure and the monopoly on tobacco, he questioned whether the Reichstag should really continue to approve one new tariff after the other. Particularly on this point, national liberal policies and the ‘Heidelberg Declaration’ were questionable. Many national liberals in Schleswig-Holstein, he pointed out, were actually free traders by conviction, but in practice had their hands tied by the Declaration. What, then, was really the position of the national liberals?32 They had, Hänel stated emphatically, only two options. They could continue to side with the government and the conservatives in an ambition to ‘pile one tariff upon the other’, as well as continue to thwart governmental accountability on budget matters, and corrupt the electoral laws. This would indeed be in all ‘consequence with the Conservatives and their enmity with Liberalism’. Or they could, like the left-liberals, turn in opposition against these foul policies.33 Rather than appealing to ‘reasons of state’, Hänel struck a different chord: the bureaucratized, top-heavy Prussian conception of state was, after all, something completely different than the more loosely integrated, federalistic idea of Germany hailed by Hänel. In essence Hänel’s rejection of the national liberals and the pro-tariff camp played on the deeply rooted suspicion in Schleswig-Holstein of anything that smacked of centralized government from Berlin. The matter at hand was as much about preserving independence from Prussia as it was, such as in the case of social insurance, about the classic credo of ‘liberating the individual from the chains of restrictions in the name of civilization’.34 By conflating these two positions, Hänel made a case which probably was more appealing to the Schleswig-Holstein mindset.

In an open letter to the voters in the seventh constituency, the liberal voting committee had drawn a clear line between, on the one hand, conservatives and national liberals and, on the other, left-liberalism. The difference, the Kieler Zeitung pointed out, was that the former put state and government before the people, whereas the latter put the people, the grass roots, before the government. 35 This perspective was, as had also been the case during the 1871 elections, easy enough to amalgamate with the age-old autonomist sentiments in the region. When linked to the issue of tariffs it could also appeal to voters in an area which, particularly around Rendsburg, was predominantly agricultural.36 Furthermore, at an early stage in the campaign the Kieler Zeitung had also been careful to point out that, in its opinion, support of the national liberals would in the long run only profit the social democrats.37 It was, all in all, a clever case of structuring critical issues and strategic deliberations in such a manner that the integration of disparate groups of voters into the party ideology was promoted (cf. Gunther & Diamond 2001). The cross-class approach in combination with the appeals made to self-determination obviously worked. Hänel secured his victory in the constituency with an overwhelming majority of 10,747 votes.38

However, striking a balance between the national liberals and the social democrats only represented one facet of left-liberal campaigning. Certain events during the campaign in the third constituency of Schleswig-Eckernförde provide an illustration of the delicacy required of the left-liberals. In the town of Schleswig, a new association had formed in the Friederichsberg district the previous year. It was the ‘Friedrichsberger Bürgerverein’. Immediately, it had involved itself in the preparations for the local, 1883 elections39 and, if less obvious, it seems to have played a part in building opinion in conjunction with the 1884 general elections as well. On 25 October, three days before election day, the members convened to enjoy a lecture given by a photographer, Schnittger, on ‘the life of the German bürger one century ago’.40 The lecture was also announced in the local Schleswiger Nachrichten the same day.41 Mundane as the event was, the proceedings did however also include the planning of an Augustenburger seminar, discussions of which involved the participation of Schnittger. 42 And this part of the agenda had not been publicly advertised. Which meaning can be read into this event?

As we have seen previously, appeals to self-determination remained a powerful tool in regional political life; and as for particularism, although much less flammable at this stage, it was still a topic of some controversy, not least among the liberals. Traditionally the Augustenburger cause held some appeal in the Schleswig area. A door-to-door poll conducted almost twenty years earlier, in March 1865, had shown that a majority of the townspeople were sympathetic to the idea (Petersen 2000: 119), and as we also remember, Count Baudissin, a particularist candidate, had more recently won the elections in this constituency in 1871. In light of this, the arrangement of an Augustenburger seminar could well have been an attempt to stir up old sentiments on the matter in connection to the elections.

At the time of the 1884 elections the liberal candidate was Asmus Lorenzen, a farmer of free trade persuasion from the village of Büdelsdorf,43 whereas Christian Wallichs of the free conservatives ran as his main opponent (the free conservatives were a faction rooted in the royal bureaucracy and, thus, signified loyalty to Berlin first and, only secondly, to Schleswig-Holstein). While losing the city districts of Schleswig to Wallichs, Lorenzen did however win the constituency as a whole.44 The choice of a left-liberal candidate from among the ranks of the farmers may well have reflected grass-roots sympathies not only for the party’s position on current issues, such as tariffs. Possibly, the outcome also reflected some of the traditional autonomist sentiments cum agrarian outlook on life that continued to exercise an influence on political life in the region.

However, the case of Lorenzen is also interesting from a different point of view. Albert Hänel himself appeared at the nomination meeting. There he assisted in the introduction of Lorenzen to the audience. The latter, he said, was a man who would not blindly follow the party line, although he had accepted all aspects of its programme. According to Hänel, Lorenzen, to be sure, was ‘no puppet, but a Landmann and also a man’,45 and therefore worthy of trust, one may assume. Personal appearance was, of course, important to prospective deputies. However, as in Sweden, personal appearance also seems to have gone hand-in-hand with a certain hesitation about associating oneself too closely with a formal party and fixed programmes: individual citizenry and its virtues were more important to a deputy than his loyalty to the party. What remains particularly striking, though, is that this tension between personal conviction and affiliation to party was brought up by none other than the party chairman himself.

Reminiscent of Eduard Lasker’s 1876 description of his national liberal faction as a ‘great political community’, characterized by unity but at the same time also diversity of opinion (chapter 1), Hänel’s statement captured the ever-present dilemma among German liberals: should they remain a loosely integrated ‘Bewegung’, a ‘movement’, or turn themselves into a coherent organization? Last but not least, Hänel’s introduction of Lorenzen was not only an admission of this problem and an acknowledgement of the personal qualities of the latter. It was also a symbolic act of reassurance in the sense that the allusions made to Lorenzen’s earthbound qualities obviously aimed at satisfying the utilitarian approach to politics among the farmers. In Lorenzen, therefore, the left-liberals had found precisely the kind of practically-minded candidate who could rebuke the criticism of their programme as being too theoretical and detached from everyday life and practice.

The campaigning in Schleswig does not only indicate the intricacies of regional political culture and the ambiguous nature of party affiliations, but also the importance of civic associations formally independent from party structures. Various ‘Bürgervereine’, liberal workers’ associations, and other civic arenas played a role both in building opinion and by breeding the kind of enlightened citizens that the liberal creed hailed, as well as filtering these citizens out as suitable candidates for the elections. This pattern was not unique to the Schleswig-Eckernförde constituency. For instance, in the sixth constituency of Pinneberg the liberals nominated the teacher Johannes Halben, born in Lübeck in 1829. Among his greatest assets was that he had not only founded the ‘Klub Fortschritt’ (the Club of Progressives), in 1863, but had also profited from 30 years’ experience of the Workers’ Educational Society in Hamburg.46 Admittedly, his was a background quite different from that of Lorenzen, but nevertheless one more in line with the socio-economic and cultural conditions in a district which for all practical purposes was evolving into an industrialized suburb. In addition to examples such as these, there also emerged other associations and spheres, positioned somewhere between being regular proxies and outright secondary organizations to the party, such as the liberal ‘Kirchenverein’ in Schleswig-Holstein (Kiehl 1966: 457).

In all these respects the liberals were better prepared compared to the conservatives, who became the last political faction to form a regional umbrella organization, as late as 1882 (Kiehl 1966: 459). Yet left-liberal organization, although encompassing the entire region, was still thin on the ground by modern standards. In addition, economic problems continued to haunt the LPSH/F throughout the campaigns of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Small cash amounts could be collected through the local committees of the party, but most of the funding was provided by the members of the executive committee in Kiel, including Wilhelm Ahlmann, who, apart from owning the Kieler Zeitung, was also a banker (Kiehl 1966; Thompson 2000). Newspaper coverage was also of great importance, much in the same manner as the Swedish liberals made systematic use of their connections with the press. In particular the Kieler Zeitung–a newspaper which (at the price of 4 Marks 50 Pfennig per quarter) ‘remained true to the ancient, Schleswig-Holstein ideals of freedom, the rights of the nation, and prosperity of the people’47–was important. It was used not only to market the party programme but also advertised for campaign contributions during the elections.48

Lack of formal organization and lack of financial resources put great stress on the individual performance of the party leadership. Above all Hänel, one among a small group of natural candidates, was kept busy touring the region during the 1884 campaign. On 1–2 October he was scheduled to speak not only in Husum and Bredstedt, but also Tondern, in western Schleswig.49 This was only three days before he was expected to deliver a keynote speech at the party convention of the LPSH/F at Neumünster.50 The venues of such events as well as for the regular nomination meetings of the party, though, were not, as often was the case in Sweden, those of the supporting civic associations themselves. Rather, political meetings among left and right alike usually convened at hotels, inns, and restaurants.51 Political culture in Schleswig-Holstein was one of local village taverns but at the same time universal doctrines, whereas political culture in Värmland to a greater extent revolved around mass organization but at the same time singular issues.

At the Neumünster convention the party consequently gathered at the local railway hotel.52 Beginning by outlining the history of the old ‘Landespartei’ and the path towards the 1884 coalition with the ‘Liberale Vereinigung’, Hänel summarized the main points of the left-liberal programme. What risked being a bland, scholarly digression turned out, in fact, to be a cleverly designed thrust into the traditions and culture of the region. It was important, Hänel noted, to understand the historical specificity of Schleswig-Holstein in order to properly appreciate the party’s position in relation to the conservatives. For one thing, the latter had no real grasp of concepts such as ‘duty’ and ‘honour’ (harsh words, indeed, to a conservative ear). Rather, they continued to consider the freedom fighters of 1848 simply as ‘rebels’ and ‘traitors’, and, furthermore, only held the Augustenburg particularists in contempt. Similar volleys were fired at the national liberals, ending with the declaration that the party programme of LPSH/F, indeed, had nothing to do with ‘capitalism and factional strife at all costs, nor with abstract Manchester doctrine, nor with the implementation of a fully-fledged free trade system.’ No, the keystone of liberalism, as Hänel saw it, was the well-being of the nation on the basis of rule by a free people.53 The message paid off.

Firstly, the alignment of the progressives with ‘Liberale Vereinigung’ was, as such, an organizational feat which strengthened Hänel’s position in the party. Secondly, there was the virtue of self-determination to be considered. In Schleswig-Holstein this line of argument was compatible with the historical and socio-economic identity of the region. It could certainly strike home among the urban middle classes but could, at the same time, appeal to the proud and self-reliant farmers. One important flaw, though, in this individualistic and anti-etatist agenda was that it made the left-liberals less ready to embrace a more progressive perspective on social reform, unlike Swedish liberals around the turn of the century; to an increasing extent they accepted the idea of state-managed social reforms, but then again, the nature of the state apparatus differed between Sweden and Germany. Put simply, while the left-liberals in Schleswig-Holstein, for obvious reasons, were convinced that the state was really nothing more than a disguise for Bismarckian authoritarianism, any equivalent to this was absent among the Swedish, including the Värmland, liberals.

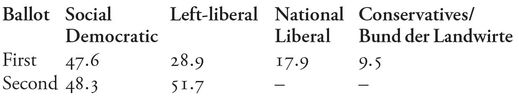

As the election results began to be reported back, it was clear that the liberal coalition had held the ground more successfully compared to other Prussian provinces–but so had the national liberals, too (chapter 1, Table 2). More specifically, the coalition received 34.2 per cent of the votes in the region, and the national liberals 27.9 per cent (Ibs 2006: 152). Out of ten constituencies, the left-liberals held sway in four and the national liberals in two. In the remaining four, the vote fell in favour of the conservatives/free conservatives (two), the social democrats (one), and–as usual–the Danish list, in the first, northern constituency of Hadersleben-Sonderburg (Schultz Hansen 2003: 464).

Proxies had played a part in the mobilization of liberalism. Yet their role was not unequivocally positive, albeit for slightly different reasons than in Sweden. Compared to Värmland, they could not equal the kind of public involvement in political life that was made possible by the popular movements in the 1887 elections or, most notably, those in 1893 and 1896. Certainly the German proxies were, as in Sweden, collective expressions of an individualized society, and of different strands of political individualism. However, political individualism as such was also, in principle, quite feasible without the underpinnings of civic association. This was not least the case as long as citizenship remained restricted because of the design of the election laws. As I have previously stressed, the main problem was that liberal proxies were not mass-based and, hence, left the electorate in Schleswig-Holstein even more volatile than what became the case in Värmland. This observation in turn begs the question of why the German liberals did not seriously pursue mass-organization by means of party instead. Paradoxically, political individualism provides the answer in this context, too. The very stress put on individual freedom, effort, and performance, whether interpreted from an urban, middle-class perspective or a rural perspective more or less automatically steered campaigning along old, established, and well-trodden paths.

Interestingly, these old and well-trodden paths had a specific feature which made liberal rhetoric sound quite different compared to the that of, most notably, Mauritz Hellberg in Värmland. His was a radicalism which, not least by the force of his anti-clerical views, tried to execute a break with history and tradition. (Then again, sequentialist interpretations of political modernization could be voiced in this context as well, such as in the liberal debating society in Karlstad, of which Hellberg was a member; see chapter 3.) Yet by comparison, Albert Hänel, possibly in part because of his professional background, made much more frequent use of the past as a value in itself, and as means of legitimizing liberalism to the voters in Schleswig-Holstein. It was, as with the 1884 elections, a regionally specific expression of ‘Historismus’. Liberalism was the defender of regional identity and tradition rather than the liberator from outdated traditions.

Momentum lost

The 1898 elections reflect two processes of equal importance to national and regional political culture: firstly, the step-by-step growth of the Social Democratic Party into the largest faction in the German parliament; and, secondly, the increased importance of ethnic orientations to nationalism and national identity. In the first case the lifting of the Anti-Socialist Laws in 1890 also led to a reorganization of the party; it thereby became a platform for a distinct working-class sub-culture, but also a political machine which soon enough was criticized because of its monolithic structure and oligarchic tendencies (Michels 1983 [1911]). Largely at the expense of the liberals, the social democrats went from 27.2 per cent of the vote and 56 mandates in 1898 to 34.8 per cent and 101 out of 397 mandates following the 1912 elections.54 In the second case the emergence of ‘Völkisch nationalism’ combined the elements of ‘Heimat’ ideology with Prussian militarism and the increasingly imperialistic ambitions of Wilhelmine Germany. Although this process was not completed by the turn of the century, it nevertheless provoked fundamental changes in political life during the 1890s, most notably expressed in the appearance of new right-wing parties. Finally, internal fragmentation gained impetus among the liberals during the 1890s. One reason was the return of the old, pre-1884 divisions, while another factor was the growing discontent with Eugen Richter, the party chairman of the German Progressive Party. At heart of the problem was Richter’s leadershipstyle in parliament, which many considered too oppositional. Tensions culminated with disputes over military expenditure and a split of the ‘Deutschfreisinnige Partei’ in 1893. While one faction remained under the leadership of Richter, now under the name of the ‘Freisinnige Volkspartei’, the other faction, ‘Freisinnige Vereinigung’, included the Schleswig-Holstein liberals (Sheehan 1978: 265; Ibs 2006: 153).