7

Mindful preparations for working with depression

Your journey journal

We have now arrived at the work and practice part of our exploration together. You might find it helpful to have a folder or a journal that you keep to write in reflections on different exercises, or thoughts you’ve had during the day, or ways in which you might respond to things differently, or even note changes in your dreams. It’s like a personal log. You can also gather things along the way – pictures, poems or articles – to stick in it. We know that writing about our thoughts and feelings reflectively can be very helpful to clarify them and can also provide insights. You will find there will be some days when you may want to write in your journal and other times you may not. Having a journey journal is, of course, only a suggestion, although I will be inviting you to use it in different ways as we go along.

First steps: mindfulness

On the road ahead we are going to explore how to work on thoughts, feelings and behaviors, to change depressed brain states. One of the most useful skills to help us in all these efforts is called mindfulness.1

In recent years researchers all over the world have dedicated a lot of attention to mindfulness and how it can help depressed people, and indeed all of us.2 The idea of mindfulness itself goes back thousands of years. Here we focus on mindfulness as a way of learning to pay attention, and hold attention in the present moment with a specific focus and with judgement. This it can bring new balance to our minds and awareness.3

Many of the great teachers of meditation point out that we only exist in this moment – we are a ‘point of consciousness’ passing through or in time. Our consciousness does not exist in the moment just gone nor in the moment yet to arrive – we only exist now. Mindfulness is learning how to bring us to be fully alive to the now of our conscious existence, the only place we actually exist. We can be so lost in the hopes or fears of tomorrow, or the regrets of yesterday, that we miss the moment now – we live in a remembered or imagined world, not in the world of ‘right now’. Of course, sometimes it is very important to reflect back and project forward, but when we do this we want to do it purposely rather than being automatically dragged there by depressed states, fears, angers or strong desires.

The word meditation actually means becoming familiar. For us becoming more mindful is to become familiar with the contents of our minds and how our minds work. Mindfulness also means becoming more aware and more ‘in’ one’s experience; to pay open or curious attention to the details of one’s inner feelings and thoughts as they emerge in one’s mind. How many of us, for example, when anxious or angry, actually stop and pay attention to where this feeling is in our bodies, what our voice sounds like, what part of our mind is now issuing the instructions to our thoughts and bodies; what are our key thoughts and fears? How often do we stand back and practise observing what is actually happening in our minds? Mostly we don’t, and our brain patterns and emotions are just ‘doing their own thing’. Mindfulness is learning how to change this ‘being caught in the automatic-ness’ of the unpleasant emotions and moods.

Yourself and consciousness

Let’s think about ourselves as existing as a point of consciousness ‘in this moment of time’. Consciousness of this type can be regarded like water. Water can contain a poison or a medicine, can be clear or muddy – but water is water – it is pure and is not what it contains. So too with our consciousness – it can be filled with joy, anxiety, anger or depression but consciousness itself is not those things. Learning to recognize yourself as a point of consciousness and distinguish this from the content (your moods, feelings and thoughts) can be helpful. A key to help us is learning about our attention.

Learning to attend

Mindfulness is a way of understanding our attention. The attention can be located as an act of choice. For example, if I ask you to concentrate and attend to the big toe on your left foot, you will suddenly notice sensations from that part of the body. If you now switch your attention to the top of your head, you will experience different sensations. Our conscious attention can be thought of as a spotlight that moves around. It is learning how to direct that spotlight, via our attention, which is key to mindfulness.

Mindfulness is therefore about the clarity of observation. Let’s try an example of eating an apple mindfully. First, you would look at the apple, and note all of its colours and textures. Hold the apple in your hand and feel the quality of its skin. Don’t rush, spend time observing. When your mind wanders from your focus on the apple (as it very easily can), gently bring your focus back to it. In this exploration, you are not judging the apple, you are simply exploring its properties. Then you take a knife, and maybe peel the apple, or cut into it. Once again, notice the effect that you have on the apple, the colour and texture of the fruit beneath the skin. Take time to really observe. Next, you may take a bite of the apple, and now you are going to focus on the senses of taste and what the apple feels like in your mouth. Chew slowly, feeling the texture in your mouth, noticing how the juice might stimulate your saliva and how it feels in your mouth. As you chew, notice how it becomes more mushy. As you swallow, pay attention to the sensations of swallowing. All focus is on the apple.

So we have explored the apple visually, by touch and feel, by smell, texture, and by taste. If we had dropped the apple, we would have been able to hear what it sounded like. In this interaction, there is no judgement, there is only your experience of your interaction with the apple. This is mindful attention, being in the activity, rather than distracted from it by other thoughts, and exploring all aspects of the activity to the full.

Notice how your mind can wander: ‘These are not good apples, where did I buy them from; I ought to eat more fruit; actually I don’t like apples! Oh damn, I cut my finger!’ If you are depressed you might have thoughts like, ‘What is the point of this, it doesn’t solve my problems’ – thoughts that will put you back into stimulating depressed patterns in your mind. One reason for doing these exercises is to practise shifting out of patterns of thinking and focusing that increase rather than diminish depression in our minds. The mind can ‘rest’ in this moment.

Mindfulness is important because most of our lives are spent doing one thing and thinking about something else, and we are never fully ‘in this moment’. Our minds are constantly distracted. Take driving, for example. We can get home and realize we can’t really remember how we got there, because our minds were full of a hundred and one other things. If something unexpected happened, such as a group of naked motorcyclists zooming past us, our attention would have been alerted, or if the driver in front of us suddenly put on their brakes, our attention would be focused again. But this is not savouring the moment; this is being brought to alertness for a specific reason. Mindfulness is about being in the moment.

Soothing rhythm and mindful breathing

We are now going to use the same idea as mindfully peeling and eating the apple, but this time focusing on our breathing. Our breathing will become a central focus around which we will do some compassion-focused exercises later. Learning how to breathe mindfully will be useful when we come to do these exercises. The key here is simply to practise without worrying if you are doing it right, correctly, adequately and so forth. These thoughts are common and understandable but they are distractions. If they arise in your mind, simply notice them and call them ‘your judging and evaluative thoughts’, smile kindly to yourself and bring your attention back on task.

To start with, find somewhere you can sit comfortably and won’t be disturbed. Place both feet flat on the floor about a shoulder’s width apart and rest your hands on your knees. Keep your back straight. Look down at about 45 degrees – or if you prefer close your eyes – whatever you find best for you. You may prefer to sit on the floor, or cross-legged on a small meditation stool. Find postures that are comfortable for you but not slouched. Sometimes lying flat on the floor can be helpful, if that is the most comfortable position for you to start your work. In my CD, which covers aspects of this book, there are ideas that you can listen to.4 The idea is not to become sleepy but to develop a certain type of alertness, focus and awareness. I will, however, explore a set of relaxation exercises with you later in this chapter.

Gently focus on your breathing. Breathe through your nose. As you breathe in, let the air come down into your diaphragm – that’s at the bottom of your ribcage in the upside down V. Place a hand on your diaphragm and notice your hand lift and fall with your breath. Feel your diaphragm – the area underneath your ribs – move as you breathe in and out. Do this for a few breaths until you feel comfortable with it and it seems natural and easy for you. Next place your hands on each side of your rib cage, as low as you can. This is slightly more awkward because your elbows will be pointing outwards. Now breathe gently. Notice how your rib cage expands against your hands outwards, your lungs acting like bellows. This is the movement of the breath you’re interested in; you feel your lungs expanding. You want a breath to come in and down but also expand you out at the sides. Your breathing should feel comfortable and not forced. As a rough guide, it’s about three seconds on the in-breath, a slight pause and three seconds on the out-breath. But you must find the rhythm that suits you. As you practise, replenish most of the air in your lungs but not in a forced way.

Notice your breathing, and play around and experiment with it. Breathe a little faster, or a little slower, until you find a breathing pattern that, for you, seems to be your own soothing, comforting rhythm. There will be a breathing rhythm that feels natural to you, and as you engage with it feel your body slowing down. It is as if you are checking in, linking up, with a rhythm within your body that is soothing and calming to you. You are letting your body set the rhythm and breathe for you, and you are paying attention to it. Rest your eyes so that they are looking down at about 45 degrees. You may wish to close your eyes, but notice that sometimes if we do that we can become very sleepy. Spend 30 seconds or so focusing on breathing, noticing the breath coming through your nose, down into the diaphragm, your diaphragm lifting, your chest gently expanding sideways, and then the air moving out, through your nose. Notice the sensations in your body as the air flows in and out. Stop reading this book, and focus on that for 30 seconds (longer if you like) and sense a slight slowing with your breathing. Some people find that focusing their attention on just the inside of their nose, where the air comes in, can offer a helpful attention focus. Try it and see.

You might notice how your body responds to this breathing, with feelings of slowing and feeling slightly heavier in your chair. If you’ve done the exercise you may notice how the chair is holding you up. However, some people can find these first stages quite anxiety provoking, and don’t actually like them. For those who do not like the breathing bit, you can practise mindfulness by holding your attention on something in the way we did above with the apple; choose something like a flower, a tree or the sky. Hold your attention there and if you mind wanders, gently and kindly bring it back. Don’t worry at all if you find the breathing tricky (many people do) and we can do the compassion exercises in later chapters without doing the mindfulness breathing. Nonetheless, it could be useful to practise, so that even if you can only do a few seconds and gradually expand over the days that would be helpful too. The sensations in the body can be difficult for some people – so practising and coming to feel comfortable with the sensations can help.

Wandering and grasshopper mind

Assuming all went well, you may have noticed that actually, although it was only 30 seconds or so, your mind may have wandered off. You may have had thoughts like ‘What’s this about? Will this help me? Did I do my job correctly yesterday? Where did that pain in my leg come from?’ If you practise for any length of time, distracting discomforts are very common. You may have heard various things outside the room; your attention may have been drawn to the postman pushing letters through the letterbox, the traffic outside or whatever. The point about this is that our minds are indeed very unruly and the more you practise this short breathing exercise and the longer you extend it, the more you will notice how much your mind simply hops about all over the place. When you first do this kind of mindful focusing, it can be quite surprising how much your mind does shift from thing to thing. This is all very normal, natural and to be expected. We need to train the mind, and the only thing that is important in this training is not to try to create anything. You are not trying to create a state of relaxation. You are not trying to force your mind to clear itself of thoughts – which is impossible. All you are doing is allowing yourself to playfully and gently notice when your mind wanders and then with kindness and gentleness bring your attention back to focus on your breathing. That’s it. Notice and return. Notice the distractions, and return your attention to your breathing. Notice how often your judging mind tries to get in on the act with thoughts like ‘Am I doing this right; is this helping me; am I relaxed now?’ Just notice these thoughts and return your attention to the breath. The act of noticing and returning your mind to the task at hand (in this case the breath) are the first steps to becoming mindful! In other words, the exercise is simply an exercise where we learn to focus attention. You are not trying to achieve anything. If you have a hundred thoughts, or a thousand thoughts, that doesn’t matter. All that matters is that you notice and then, to the best of your ability, gently and kindly bring your attention back to the breathing.

If you practise that ‘attention and return’, ‘attention and return’, with gentleness and kindness you may find that your mind will bounce around less and less. It may become easier. Remember, you are not trying to relax as such. All you are doing in this exercise is noticing that your mind wanders and then return it to focus on your breathing. Notice and return, and each time it wanders, that’s fine; don’t get angry with it, kindly bring it back to the focus of your breathing. It can also help if you allow yourself to smile when you notice the wandering mind. Develop an attitude of gentleness and kindness to your wandering mind.

This exercise of mindfulness is allowing yourself some time where you focus on your breathing and for your mind to come back to that single focus. You may take an interest in how much of a grasshopper (or kangaroo) mind you have, but at all times try not to condemn your wandering mind, always be gentle, always kind. Notice and return. If you have thoughts that you are not doing it right or that it cannot work for you, then note these thoughts as typical intrusions and return your attention to your breathing.

Some people like to go on and have a focus for their attention, such as a candle or a flower (concentrative meditations). Again the issue here is learning how to enable one’s attention to focus, without it being cluttered with various thoughts, reflections, concerns, worries and so forth; or if it is, to notice this as ‘thoughts arising’. Another variation is to have a mantra, which is a word or phrase to focus on in one’s mind. Some people think you need to be given your mantra whereas others believe you can choose one for yourself such as ‘om’, ‘peace’, ‘calm’ or ‘love’. The key word should have meaning for you, and ‘feel calming’.

Applying the principles of mindfulness

You can use mindfulness in many different ways. Another aspect of mindfulness is to become more fully aware of each moment we are in. For example, while eating, you may practise really focusing your attention on the taste and texture of the food, chewing and eating slowly. Waiting for a bus or lying in the bath or while out walking, really focus on where you are. If walking, focus on the movement of your body. Notice how your feet lift and fall in coordinated action; how the foot comes down from heel to toe as it hits the ground; how your arms move and your breathing flows with the action. In mindfulness we can focus on the thought, ‘I am walking.’ Or focus you attention on what is around you. The idea is to help your conscious mind focus on where you are ‘right now’ – using all your senses – noticing the colours, the sounds and the textures.

A pleasant place to practise mindfulness is in the bath. Often when we relax in the bath we allow our mind to wander all over the place. However, practise breathing your soothing rhythm and breath and attend to the experience of being in the warm water. Feel how your weight is different, explore from the tips of your toes to the top of your head the warmth of the water caressing your body. ‘Be’ in every detail of the sensory experience. These exercises can be enhanced if you allow yourself a gentle compassionate smile and facial expression.

Noticing where we are

You may wish to be in the moment in different ways by paying attention to your senses. While out walking, direct your attention and notice the sky – keep the focus there – notice the changing textures of the sky from the horizon to overhead, or the rushing of the clouds, or their shapes or how the light catches different aspects of the clouds; or on the trees with their different shapes, textures and leaf colours, the feel and taste of the air. Again, if the mind wanders, gently bring it back. The very act of seeing colour and hearing sounds, and sensing the air we are enmeshed and live in, can become like new experiences to us, focused on what is around us in-this-moment.

When we get depressed or worried or preoccupied we can withdraw from the world of the senses and being fully in this moment, and become focused on our thoughts about tomorrow or yesterday, or on feelings or feeling states – the heaviness in the body or the butterflies and anxiety of dread. We do not live in the present moment, but somewhere else. When we are on automatic pilot we are lost to our thoughts and we may hardly notice the outside world. There is evidence that learning to be mindful can help depression because it lifts us away from over-focusing on the negative; gives our brain a chance to rest without being bombarded by negative thoughts.2

Developing Emotional Tolerance

We know our minds will give us a range of thoughts, feelings and moods. Mindfulness can help us to become aware of them without forcing them away, being frightened of or fighting with them, avoiding them, or getting caught up in them. We learn to stand back and observe; to take a ‘view from the balcony’, if you like. If you are feeling sad, be with that sad feeling rather than pushing it away. If you’re fretting or worrying over something, notice how your mind pulls you this way and that. In mindfulness we are not trying to change thoughts but change our relationship to our thoughts and our feelings.

Jack’s suicidal feelings and thoughts had previously worried him, and he would try to put them out of his mind. This of course made them come back even harder. He learned to acknowledge them and recognize that they came and went from time to time; but it was possible for him to acknowledge them, to stand back from them and become less frightened of them; he noted that he shared these experiences and thoughts with many millions of other people; and he could be compassionate to them. Of course, different people find different things helpful in coping with these thoughts. Some people find distraction works, or talking to others, or reminding themselves that they have had such thoughts before and they passed. And of course if you feel unable to control them, then contact your family doctor.

Karen was, in her own words, a ‘fretter’. She learned to pay attention to her thoughts and noticed that they were often full of ‘What would happen if . . .?’ ‘What would happen if I didn’t do . . .?’ Gradually she learned to stand back from them, became more observant of her fretting thoughts, ‘let them be’ and found that ‘by themselves’ they became less intense.

Mindful relaxing

So now we can let be, we can move to another exercise using ‘notice and return’, but this time we are going to focus on allowing ourselves to relax. I am going to talk about letting tension go, and by this I mean trying not to see tension as a bad thing or your enemy that you have to get rid of, but rather as an understandable way your body has tried to protect you by becoming tense and ready for action. We need to be gentle and help the body understand that it does not need to be like this right now. As we let go of our tension, it is like giving the body permission to relax – for which it is grateful.

You can hear this guided exercise on my CD.4 So now once again focus on your breathing until you click into, find, sense, or feel the rhythm that feels most comfortable and soothing to you. If that seems hard, not to worry, just breathe in as comfortable a way as you are able. Spend about 30 seconds finding your rhythm – longer if you wish. When you have done that, focus on your legs. Notice how they feel for a moment. Imagine that all the tension in your legs is flowing down through your legs and down into the floor and away. Let it go on its way. As you breathe in, note any tension and then, as you breathe out, imagine the tension flowing down through your legs and out through the floor. Imagine your legs feeling pleased and grateful that they can let go. Imagine your legs smiling back at you. Sometimes people find if they slightly tense their muscles as they breathe in and then relax as they breathe out this can be helpful. Spend 30 seconds (longer if you like) letting that tension go with kindness.

Let’s focus on our bodies and imagine the tension in our bodies from our shoulders down to our trunk and again, as you breathe out, imagine the tension leaving this part of your body, going down through your legs, down through the floor and away. Again if it helps, gently tense your stomach and back muscles as you breathe in and then relax as you breathe out. In a way it can be like imagining emptying a vessel of the tension that’s now running through your legs and down through the floor. Your body is grateful and you feel kind to it.

Focus on the tips of your fingers, through your wrists, arms, elbows and shoulders. Imagine that the tension that was there can be released – can be let go of. Gently let the tension go so that it can run off down through your body, down through your legs and out through the floor and away – free.

Imagine the tension that sits in your head and neck area and forehead. The tension has been your alert system in action, and it would like to be released now – to take a rest. Again, as you breathe out, imagine it running down through your body, down through your legs and out through the floor.

So now you can focus on your whole body. Each time you breathe out, focus on the keyword RELAX. Imagine your body becoming more relaxed. Spend a minute or so doing this (longer if you like). Create a ‘calm’ facial expression.

Ending

You can end this exercise by taking a deeper breath, moving the body around a little and stretching your arms out. Note how your body feels and how gently grateful it is to you for spending time to let go of the tension. Take a moment to experience the idea of your body being grateful to you for spending time with it. When you are ready, get up and carry on with your day. You can practise this exercise as often as you find helpful. It can help with sleep too. Remember that if your mind wanders when you do it, you can gently bring it back to the task at hand – with a slight, kind smile. And of course practice will help it to become easier for you.

Variations

There are many variations on this basic exercise. It’s up to you how you go about exploring different relaxation exercises and finding ones that works for you, or that you like. The one that I’ve given you is one with a mindful and compassionate focus, and helps some people. The idea is to do the practice and then see what happens for you. When you are trying to relax, ‘notice and return’ when your mind wanders from the focus on relaxing. Remember, it’s a bit like sleep: we create the conditions to aid sleep, but if we focus too much on sleep it slips away. The idea is that as you sit there, allowing yourself to focus on your breathing, you may become more relaxed as you become more familiar with your body and the feelings of relaxation; you may become more aware of where tension sits in your body.

Gradually, you can come to think of your body as a friend, and you can become a friend to your body and take an interest in your body and how you can nurture it, care for it and help it relax. Tension is not your enemy to be ‘got rid of’, because it only came as a form of protection and preparing your body for action – so it is grateful for its release from your body. It’s like telling the army ‘the battles are over and you can all go home now’. Focus on the feeling of gratitude in your body for doing these exercises. Each time you finish an exercise feel your body’s gratitude for a moment. Developing this attitude to relaxing counteracts tendencies to force yourself to relax, getting irritated if it is difficult, or seeing tension as ‘bad’ and ‘to be got rid of’.

Relaxing in activity

Sometimes people can notice certain feelings in their bodies that are unpleasant and are associated with emotions. Sometimes people find relaxing actually makes them feel more anxious. This is not uncommon. When we are in different mind and brain states, relaxing might be a bit tough. If I am very uptight or agitated about something I find focusing on soothing breathing with some physical activity works for me. I might focus my mind on the here and now and engage in soothing breathing but along with physical activity such as cycling, digging the garden, taking a walk, doing the dishes (okay, emptying the dishwasher) or playing guitar.

Sensory focusing

When Sue Procter and I ran a group for people with mental health difficulties, they found mindfulness and relaxation hard at first.5 We brainstormed the issue together and they felt that if they had something they could focus their attention on, other than their breathing and bodies, this might help to get them started. Together we came up with tennis balls to focus on. They would do their soothing rhythm breathing and mindful attention, but focus on holding a tennis ball, exploring its textures and feel in the hand – and yes, it made for some very amusing comments – ‘Hold on to your balls, we are going mindful!’

Grounding

In many parts of the world people have a focus on things like worry beads that are smooth to the touch and can be run through the fingers. When I lived in Dubai in the late 1960s I was struck by how many people used worry beads, with the very clear understanding that these were to help them with attention and staying calm. These beads help to ‘ground’ them, keep their attention focused.

Sometimes people like to ground their meditations or relaxation exercises. You can do this in a number of ways. One is to find a stone you like the look and feel of. As you do your relaxation exercises, hold the stone gently in your hand. Feel it as you breathe. This will help link the feeling of your stone to your state of relaxation. We are going to use the same idea when we look at compassionate imagery in the next chapter. Then later, if you’re feeling tense you can breathe the soothing rhythm and hold your stone, to help ground you slightly.

Another grounding aid can be to use smell. Some people like to associate relaxation and calm with a scent of some kind. Aromatherapists can provide all kinds of smells/scents that are associated with relaxing. If (with or without their help) you find one that suits you, you can carry it with you so that if you want to relax you can engage your breathing and also use your smell/scent. Psychologists suggest that we can prime states if we use multiple senses, such as attention, smell and/or touch.

Another common grounding experience is to gently touch your index finger and thumb together while you’re doing your relaxation exercises. Then when you relax once again, bring your index finger and thumb together. For example, if you were practising your relaxation at work, you can sit with your fingers in that position. Sometimes if we are upset and we want to ground ourselves we can just engage in the soothing rhythm breathing, with index finger and thumb touching.

As with all the exercises in this book, once you understand the principles of what we are trying to achieve (that is to bring some balance to our emotion systems and activate the soothing system in our brains), then look to your own feelings and experience to guide you – try out different things and see what works for you. You have intuitive wisdom; you just need to listen to it.

Keep in mind also that these ways for being with our bodies can also be used when we are engaging in activities. Suppose we have to do the washing up or the ironing: we can practise doing them by working through our relaxing training, rather than being on automatic pilot and ruminating on our difficulties. Developing a relaxed body is a way of being kind and gentle with it and nurturing it. Sometimes we have to be reminded to do it, so it can be useful to put notes about the place – perhaps behind the sink, or near the bath.

Bring relaxation into everyday life: the chill-out

Being alone

It is often useful to recognize that although caring relationships are very important for us, at times it is important to be alone. Of course some people live alone and feel lonely, but for others it can be hard to find personal space and time in modern houses that are designed as small boxes. And of course the British weather can trap us inside. However, for millions of years we would not have needed to wander far to get away from others. Aloneness as choice is of course very different from loneliness which we do not choose. If possible, get some time alone. I have known some women who feel guilty about this, or for telling the family they need chill-out time alone. One woman noted that even when she went to take a bath it wasn’t long before voices would call at her, ‘Where are you; where did you put my shirt; Mum, have you seen my homework?’ Explain to people that we all need time for ourselves, to chill out, and this is not a reflection at all of not wanting to be with people. The point is to put time aside to be alone and think about how to use that time to nurture and nourish yourself.

Chill out in your mind

If you are busy, small chill-outs can be helpful. Keep in mind all the time that what you’re trying to do is to stimulate and regulate brain patterns. For example, you get a phone call and someone upsets you. Stop for moment and focus on your breathing. Notice the feelings rippling through your body. Try putting them into words, as research shows that this helps with regulating our feelings. For example, ‘Right now my body is feeling tense. I have this tension and butterflies in my stomach, my face is tense, my mind is leaping from one angry or upset thought to another. Okay, let’s find the soothing rhythm and reside there for a while. My old brain will be rushing along as it does, but I am going to be with my soothing rhythm for a moment and watch my thoughts and feelings go by.’ Perhaps you have seen those colourful spiralling patterns that are created on the computer when we play music – it can be something like that. This learning and practice, to stand back and observe our minds, can be very helpful. Shortly we will be looking at compassionate imagery and how it can be added into this work.

In Chapter 4 we noted that we can have many mixed and conflicting emotions all at the same time. If we are rushing we don’t take time to pull back from the many feelings swirling around in us. For example, in addition to being angry about something, we might feel sad and anxious. We can engage in soothing rhythm breathing, and pull back from our emotions, become more observant and aware of their mixed and varied textures. As we become more emotionally aware we can learn to recognize these feelings, and even to spot them as they arise. This can be very helpful because it means we can take steps to help ourselves have more control with feelings.

Mindfulness can be a way of engaging in all aspects of our lives. Although it is extremely helpful to have time aside which you can dedicate to mindful practice, it is also useful to bring it to key activities in all facets of your life. Mindfulness can help us to enjoy the small things more, to savour our pleasures.

Becoming an alien for a day

There is a rather nice playful exercise that you can try to see if this creates a type of mindfulness for you and new feelings about being alive – this is to imagine becoming an alien for a day. Imagine that you come from a very different planet, maybe one where there is little light and the sky is dark, and you’re visiting here. You are fascinated by everything that you see and sense; by the sky and its ever-changing colour patterns, the smell and feel of the air, the sounds around you, the colours of the cars, the trees and the grass. Allow yourself to be amazed and fascinated by the greenness in the living plants and the shapes of leaves. The idea is to playfully begin to experience the world anew; to bring a freshness to our perceptions and senses. I once read about some funny graffiti. Someone had written ‘Is there any intelligent life on this planet?’, clearly bemoaning some of the silly things we humans do. Underneath someone had written, ‘Yes, but I’m only visiting’.

The art of appreciation

If we can direct our attention to where we want to direct it, to the top of our head or to a big toe or to the plants sitting on the sideboard, why not use this ability to stimulate some of our positive emotions? There is an old saying that ‘The glass can either be seen as half full or half empty’. When we feel good the glass is half full; when we’re feeling depressed we see it as half empty (if we are a bit paranoid, we might wonder who has been drinking our water!). We know that our moods shift our attention. The glass is the same whatever – it does not change – only our feelings and perceptions of it do. But we can also practise learning to shift our attention to the things that we appreciate, things that stimulate pleasures and nice feelings in us; we can practise directing our attention to the half-full bit of the glass. Here’s how to have a go.

Each day when you wake up, focus on the things that you like or that give you just a smidgen of pleasure. For example, you may have liked being in a warm bed. Rather than focus on how having to get out of bed is annoying, smile to yourself at the enjoyment you have had in being comfortable and warm and in just 16 hours or so you can come back here. Think about how you enjoy the shower or the taste and feel of your first cup of tea, or the taste of your breakfast, or reading the newspaper. When you make your tea and toast, try doing it mindfully. Pay attention to the water, that life-giving fluid, and how it gradually turns brown as the tea infuses in it; notice the toast has got lots of dark crumbs; if you were an ant crawling over your toast it would be a lunar landscape. When was the last time you really tasted fresh toast and butter; I mean took the time and attention and really tasted it? Do you know the smell of the air of a new spring day; do you take time to really breathe it, notice it and appreciate it?

Even doing something mundane such as the washing-up, do you notice the warm feeling of the water, do you notice the bubbles and the way in which you can see rainbows in the bubbles? We lose our fascination because we are a species that easily gets used to things, we get bored and want something new. We’re also thinking about so many other things – one of which is that it is a drag to have to do the washing up when we are tired and want to do so many other things – like get back to that warm bed. But learning ‘to notice’, to feel and to see, can stimulate our brains in new ways.

Appreciating other people

Take time to appreciate what people do for you. Choose a day and spend time focusing only on the things that you like and appreciate in people. The things you don’t like you will let go and not focus on. You can do that tomorrow if you want to, I guess. Think about how all of us are so dependent on each other. People have been up since 4 a.m. so we can have our fresh milk, bread and newspapers, and every day they do the same. What about the people you work with? What are their good points? How often do you really focus on those? How often do you make a point of telling people that you appreciate them? What you are doing in these exercises is practising overruling the threat system that will focus you on the glass being half empty. It’s what it’s designed to do, and what we can so easily be pulled into. So let’s start to take control over our feelings and deliberately use our attention to practice stimulating emotion systems that we want to stimulate because they will give rise to brain patterns that give good feelings; appreciation is one way of practising doing this.

Sadness

If we are depressed then in becoming mindful we can also become aware of unaddressed issues in ourselves. When people practise mindfulness, it is not uncommon for them to become sad and even tearful because they are now open to unaddressed issues. Once the mind stops rushing from thing to thing it can begin to experience the more subtle levels of itself. For ex ample, Jennifer discovered that working with a compassionate form of mindfulness made her feel sad. Then she realized it touched a part of a memory of the death of her mother five years earlier. In her heart she knew she had been trying to avoid grieving – almost as if, if she didn’t grieve, then maybe mum hadn’t really died.

So if you have sad or anxious feelings arising in your work, stay with them – be mindful and observant of them, maybe write about them in your journal. If you have friends or a partner you may wish to discuss your feelings with them. If these feelings seem an important block to you, and you’d like to find a way to work with them, you may want to find a group to work with and share your experiences. Or you may want to find a mindfulness or meditation teacher, or a therapist who works with mindfulness, or offers you space and reflection for your feelings. The point is that there is nothing wrong with you or with your mindfulness if distressing feelings start to bubble up; this simply may be an indication that there are things you could address, and perhaps obtaining the help of others will be really useful to you at this time in your life.

Sometimes of course we focus our attention on certain things, or do certain things, to avoid certain feelings, thoughts or memories. Again, this is very understandable, and sometimes helpful. For example, Karen, a young doctor, tried not to think about the death of a close friend when she was at work as she didn’t want to be tearful in front of her patients. Sonia did not want to think about her unhappy childhood experiences in class when she was teaching. The ability to control attention and emotions is of course very helpful. The point is though, do we give ourselves the opportunity to create space and time to explore these things and themes and heal them, or are we always on the run from them? If you are very busy you may skip lunch, but if you keep avoiding eating your body will become weak. As they say, there is a time and place for everything. However, depressed people are notorious for never creating space, or finding it very difficult create space, to actually deal with the things that are hurting them inside.

If you are very depressed you may find these exercises hard because our positive systems are toned right down, but do have a go and give it some time. You may find the exercises easier as your mood shifts.

Overview

Mindfulness is a way of learning to use our attention and train our minds. What I have written here are some basic ideas. If these appeal to you then do seek out trained practitioners who can take you further on your journey of exploring mindfulness, teaching the traditions and opening up new ideas for you. There is much more to mindfulness than we have space to explore here.

Our minds are often easily pulled and controlled by our emotions, key worries or moods.

We can learn to become more aware of this and exert more control.

A key skill is that of mindfulness which is learning to pay attention in a particular non-judgemental way. Recent research has shown this can be very helpful to people.

Mindfulness can also be used to direct attention in a particular way, on specific activity.

Mindfulness can be used to bring you a new interest in the world and appreciation of aspects of it.

Directing our attention so that we learn to focus on the half-full rather than the half-empty glass, and learn to focus on what we can appreciate and enjoy in ourselves and others, can be helpful to our minds.

EXERCISES

Throughout this book we will be exploring various exercises. The more effort you can put into these exercises the better, of course. But some exercises suit some people better than others, so do find what suits you. On the other hand, don’t give up on things too easily if you find the exercises difficult, because they might still be very useful to you. Indeed, the very fact that they are difficult may suggest a need for practice. Be honest with yourself. Here are some exercises in regard to mindfulness.

Exercise 1. Putting time aside to practise

You may listen to some of the CDs mentioned in Appendix 3. Or just practise your soothing breathing relaxation. Or seek out a group in your area to practise with.

Exercise 2. Bringing mindfulness into your everyday life

Whether you are waiting for a bus, having lunch or a bath, talking to your friends over coffee, practise being fully in the moment; if your mind wanders on to different topics, fears or concerns then gently bring it back. When talking to people, listen to what they are saying, rather than getting caught up in thoughts about whether they are interested in you.

Exercise 3. Sometimes just sit

Practise the ability to sit or just be with your thoughts and feelings and simply observe. Notice that you will have easy and hard days for this.

Exercise 4. The journey journal

Keep notes in your journey journal to reflect on how your practice is unfolding.

8

Switching our minds to kindness and compassion

This chapter explores some ways in which we can direct our thinking and attention to activate a soothing part of our brain. We’re going to be looking at developing kindness for ourselves and for others. Both these can really help our minds become more settled and cope better with life difficulties. However, some depressed people are actually resistant or frightened of the idea of being kind to themselves, even when this can help with depression. If this idea of self-kindness seems strange or threatening to you, just stay with it for a while and later we will explore your fears of becoming kind, understanding and compassionate to yourself. But it is always just a step at a time.

In this chapter we are going to use our imagination. Some of you might think, ‘Oh, I am not very good at imagining things, I have no imagination.’ Well, don’t give up on the idea yet, let’s have a go and see how far we can get. In fact, you don’t have to be good at imagining things; it’s the act of trying that is important. The key is trying to direct your attention and create things in your mind that are good for your brain.

It is important to recognize that when we ‘imagine things’ we usually don’t see detailed pictures in our minds. Generally, images are fleeting and we get fragments and glimpses of things. For example, if I ask you to imagine your favourite meal, or the house you might like to live in, or what you will be doing tomorrow, you probably will not get a clear picture in your mind; more like fleeting impressions and feelings. When we talk about imagery we are really trying to create ‘a sense of’ as opposed to a ‘clear picture of’. It is about how we direct our attention, the focus of our minds. For all of the exercises below it’s really the effort to create things in your mind, in a certain way, that matters rather than the results, or having clear pictures in your mind.

Mindful imagery

When we do these exercises we do them mindfully (see Chapter 7), aware that our attention will wander. You might be able to focus for a few seconds and then your mind wanders off to various things you have done, think you should do, or want to do and so on. It does not matter if your mind wanders a hundred times, gently bring your attention back on to the task. The act of noticing and redirecting your attention is the important bit. If you find thoughts like ‘I can’t do this’, ‘I am not doing this right, I cannot feel anything’, notice these thoughts, and then gently and with kindness bring your mind back to what you’re trying to do. You will also notice that some days you will find it easier than others. In all these exercises there is no forcing or pushing oneself to do things. We simply put time aside to do the exercise, without judgement of whether it goes well or badly, because there is no well or badly (unless you make that judgement) – rather there is just ‘the doing’. Practice on a regular basis helps, of course, as it does for any skill we want to learn, be it playing golf, the piano, or painting – practice will help us improve.

Safe place imagery

The first imagery exercise we’ll do is about creating a place in our minds that we feel comfortable in. Let’s deliberately practise creating in our minds places that we find soothing, calming and where we want to be. To begin with, it is useful to start by sitting or lying down comfortably and going through your soothing breathing rhythm and a short relaxation exercise (see pages 123–5). If you don’t like the breathing exercise then sit quietly for a few moments. Then allow your mind to focus on and create a place that gives you the feeling of safeness, calm and contentment. The place may be a beautiful wood where the leaves of the trees dance gently in the breeze. Powerful shafts of light caress the ground with brightness. Imagine a wind gently on your face and a sense of the light dancing in front of you. Hear the rustle of the trees; imagine a smell of woodiness or sweetness in the air. Or your place may be a beautiful beach with a crystal blue sea stretching to the horizon where it meets the blue sky. Underfoot is soft, white fine sand that is silky to the touch. You can hear the gentle hushing of the waves on the sand. Imagine the sun on your face, sense the light dancing in diamond sparks on the water, imagine the soft sand under your feet as your toes dig into it and feel a light breeze gently touch your face. Or your safe place may be by a log fire and you can hear the crackle of the logs and the smell of wood smoke. These are examples of possible pleasant places that will bring a sense of pleasure to you, which is good – but the key focus is on feelings of safeness for you. They are only suggestions, and your safe place might be different.

When you bring your safe place to mind, allow your body to relax. Think about your facial expression; allow yourself to have a soft smile of pleasure at being here. It helps your attention if you practise focusing on each of your senses; what you can imagine seeing, feeling, hearing and any other sensory aspect.

It is also useful to imagine that as this is your own unique safe place, the place itself feels joy in you being here. Allow yourself to feel how your safe place has pleasure in your being here. Explore your feelings when you imagine this place is happy with you here.

When you become stressed or upset you can practise your soothing breathing rhythm for a few minutes and then imagine yourself in this place in your mind and allowing yourself to settle down, to give you some chill-out time. Keep in mind that we are using our imagery not to escape or avoid, but to help us practise bringing soothing to our minds. Keep in mind too that these are all what we call behavioral experiments for you to try out and see what happens inside you. You get your own evidence for what is helpful to you, and build on that.

Compassion-focused imagery

Compassionate colour

Sometimes depressed people like to start off with imagining a compassionate colour. Usually these colours are pastel rather than dark. Engage in your soothing breathing rhythm and imagine a colour that you associate with compassion, or a colour that conveys some sense of warmth and kindness. Spend a few moments on that. Imagine this colour surrounding you. Then imagine this entering through your heart area and slowly through your body. As this happens, focus on this colour as having wisdom, strength and warmth/kindness, with a key quality of kindness. It would help if you can create a facial expression of kindness as you do this exercise.

One patient noted when he used compassion to help him face up to difficult decisions, the colour he associated with it became stronger. He was good at experimenting and seeing what worked for him; listening to his own intuitive wisdom. He began to think about his compassionate colours as helping him with different things.

Compassion qualities

Compassion is ‘being sensitive to distress with a desire and commitment to try to relieve it’. It is also an openness to the desires to see self and others flourish, and taking joy in that flourishing. Compassion and warmth are not just distress-focused – but a commitment for creating ‘contented joyfulness’ too. We can see compassion in lots of different ways, for example as simple and basic kindness, openness and generosity. We can add to these the idea that compassion is also related to wisdom (it can’t be unwise), strength (it is not weak and indeed often helps us develop courage), warmth (linked to the feelings of kindness) and non-judgemental attitudes. In the next chapter we will look at these qualities and skills in more detail.

The flow of compassion

Compassion-focused exercises and imagery are designed to try and create feelings of openness, kindness, warmth and gentleness in you. You are trying to stimulate a particular kind of brain system through your imagery. We can do this in a number of ways, such as using our memory and also our imagination.

Compassion-focused exercises can be orientated in three main ways:

Compassion flowing out from you to others. In these exercises we focus on the feelings when we fill our minds with kind thoughts and wishes for other people.

Compassion flowing into you from others. In these exercises we focus our minds on opening to the kindness of others. This is to open the mind and stimulate areas of our brain that are responsive to the kindness of other people.

Compassion for yourself. This is linked to developing feelings, thoughts and experiences that are focused on kindness to yourself. Life is often very difficult and learning how to generate self-compassion can be very helpful during these times and particularly to help us with our emotions.1 The key is practising, developing and focusing your compassionate mind.

Now we are going to explore experiences for each of these three aspects. In all these exercises below it is your intentions and efforts that really matter. You may need to practise your feelings before they come naturally. So we can learn how to become compassionate because we try to practise thinking and acting compassionately, whereas the feelings may be harder to generate.

Becoming the compassionate self

The first set of exercises is focused on you practising generating feelings of compassion within yourself. Here we are going to work on your inner kindness and how to focus it, build on it, learn how to direct it and practise it. In a way we are going to use exercises that good actors use to create states of mind in themselves. For example, if actors want to convey anger or anxiety or sorrow, they try to create these feelings in themselves. Indeed when they ‘get into role’ it can actually change their bodies and physiology. If you get into an anger or anxiety role, your heart rate may go up. Imagining ourselves in a role, or as having certain feelings and thoughts, changes our physiology. We can use this well-known fact to create compassionate healing patterns in our bodies.

First, find a place where you can be alone and quiet. Now, gently, with your soothing rhythm breathing, if you can, imagine that you are a wise and compassionate person. Think about all the ideal qualities you would love to have as such a person. Imagine that you have them. It does not matter if you have these qualities or not in reality because we are simply imagining them. Research has shown that just imaging doing certain things changes our brains – and might actually make us better at that thing. Imagine that you have those qualities right now, in this moment. Imagine having great wisdom and understanding. Spend time imagining what that feels like.

Imagine having strength and fortitude. Spend time imagining what that feels like. Next imagine having great warmth and kindness and never being judgemental and again spend time imagining what that feels like. Think about what other qualities you’d like to have in your compassionate self. Imagine that you have them. Imagine your inner sense of calmness in your compassionate self that is based on wisdom. Try imagining each quality, noticing how that feels. Adopt a kind and gentle facial expression and spend time exploring that. Assume a body posture that feels compassionate to you, and spend some time exploring that too. You can also bring to mind ‘you at your best’, recalling a time you have felt calm, kind and wise. Breathe your soothing rhythm and focus on these memories and qualities.

Imagine the sound of your voice, your tone, pace and rhythm when you speak from this compassionate self. Imagine the emotion and feelings that are in you and are expressed in what and how you speak. You might imagine yourself as younger or older than you are now. Imagine yourself dressed in a certain way. I don’t know why, but for me I imagine having longer hair – it’s somehow associated with my image of a compassionate self. Maybe I am being kind to the fact that I am going bald!

Each day, put some time aside to ‘play with’ this role of being a ‘calm compassionate self’. Sometimes depressed people tell me that they’re like this already because they are kind to others. Indeed that might be so, but they can also be a bit submissive and do things they don’t really want to do because they want to be polite or they want to see themselves as a nice person and worthy of being loved (people pleasers). And that is perfectly understandable. However, the compassionate self we are thinking about here is not worried about what other people think. We have to distinguish true compassion and kindness from submissiveness.

Compassion under the duvet

Many meditation guides will advise you to spend time on your practice, perhaps sitting for 10 or 20 minutes a day. Tibetan monks may spend hours each day on their meditations. When we are depressed, that’s a bit tough! So let’s begin with what I call ‘compassion under the duvet’. When you wake up in the morning, or before you go to sleep, spend a moment or so with your soothing rhythm breathing, wearing a kindly expression and making a commitment to try as best you can, without judgement, to become a compassionate person. Focus on your kind facial expression. Imagine that you are a compassionate person and run through the exercise above.

Any time you have, such as waiting for a bus, or sitting on a train, or in a waiting room, or lying in the bath or walking – concentrate on your breathing and focus your attention on being a compassionate person inside yourself. These are times when our mind is often just idling along thinking all kinds of things, so why not use this time more productively to practise your exercises? You may find that if you practise every day, even if it’s only for a minute or two, the sense of compassion will actually stay with you more and more and you will want to practise more. Little and often can be very helpful.

Using your compassionate self

Different people find that they prefer to do things in a different order to that which is given here. Try for yourself and see what works for you. Perhaps focusing on compassion for others or developing your compassionate image (see below) is best for you as a starting place.

Wanting to be free of depression

When you feel you have the basic idea of imagining yourself as a compassionate being, and can notice but don’t engage (in fact smile at) all those thoughts that whisper in your mind, ‘No you’re not; you can’t do this; it’s not going to work you know,’ you can focus on a few key statements such as:

May I be well.

May I be happy.

May I be free from suffering.

Focus on the desires in the words and your kindly facial expression. Feelings may come slowly with practice.

If you feel this is a bit overwhelming, pull back to focusing on just being a compassionate person; focus on your breathing, your facial expression and the tone of your voice. If you feel uncomfortable – say you feel you do not deserve compassion or for some other reason – then stay with the exercise for as long as you are able. You are slowly desensitizing yourself to fears and concerns about being kind to yourself. Try not to engage with arguments for or against in your mind – just do the exercise as best you can. If you feel very little, do not worry as the practice itself can be helpful – simply give some time to the exercise. Again, go at your own pace and explore how these ideas work for you. If this is still tough for you then you might want to start your practice with compassion for others (see below). If this is still difficult then there are other exercises throughout this book that you might get on with. The point is to try not to force anything – just be as mindful and open to possibilities as you can. It’s like sleeping – we can’t force ourselves to go to sleep, and if we keep checking ‘Am I nearly asleep now?’ it doesn’t help. We can only create the conditions where sleep may occur.

Developing self-compassion for the difficult parts of ourselves

We are now going to use this compassionate self and focus it on others and on ourselves. When you feel you have practised becoming the compassionate self a few times, and are beginning to get the hang of it, you can use this exercise to help you cope with difficult feelings or setbacks in your life. For example, imagine that you are angry but are also fighting with yourself about it. Sit comfortably for a moment and create your compassionate self. Remember to adopt suitable facial expressions. If you have been engaged in your soothing breathing, just have a sense of your body calming. Now imagine your angry self; see it a few metres in front of you. Look at the angry expression and note the feelings inside this angry part of you – the frustration or sense of injustice – feelings that are not very pleasant. Now feel compassion for the angry part of you that you can see in front of you. You are not trying to change anything, because you realize that anger is part of our human brain that can be powerful and unpleasant. To the best of your ability, send compassion to that anger you see in front of you. It can have as much compassion as it needs. Notice what happens if you just sit compassionately with your anger.

If you find your mind wandering, refocus it on your powerful compassionate qualities. If you feel you are getting pulled into the anger and starting to feel angry again, then break off, pull back and re focus on your breathing and becoming the compassionate self. See your compassionate self as the wiser, older, more rooted part of yourself – you at your best. When you feel back in that role then re-engage. Your sense of yourself should also stay in the compassionate position, so pull back and refocus if that slips. If you feel yourself become critical of yourself, then again pull back and refocus on being the compassionate self.

Notice how if you hold your compassionate position, somehow that can feel quite powerful because it comes from a position of wisdom, fortitude and strength. Explore that sense of power-fulness from this position. I chose anger as the emotion to focus on here because anger and frustration are often emotions depressed people struggle with. Another emotion you might wish to work with might be anxiety.

When you feel ready you can engage with ‘the depressed self’. Once again see this (depressed) self in front of you, and in your wisdom recognize our brains have been designed to allow depression, and that is not our fault. Life can be very hard and painful. The depressed self is only one of many selves and brain patterns. The most important thing is to practise having compassionate kindness towards this self rather than anger, contempt or fear. And this is not self-pity or feeling sorry for yourself, because compassion asks you to develop wisdom, strength and courage as well as warmth and kindness.

When you first focus on the depressed self you might feel pulled into the depressed self, and tearful. Pull back, and refocus on the compassionate self so that compassion grows in you – feel yourself expanding and becoming stronger based on wisdom and understanding. This may take time.

People’s experiences with this can be very different. One woman felt tearful and cried, but felt this connected her with important feelings. She felt better because she was able to end her sitting with a compassionate focus. Another woman started out okay, but then felt overwhelmed and could not hold the compassionate self position. She needed more practice. Another person become agitated and had to work slowly on the compassionate self. The key thing is not to be overwhelmed but to work at your own pace and explore what is helpful for you. Your goal is to become kind to yourself and understanding of your depression. In these exercises we are not trying to change the depressed self but take a compassionate stance towards it.

Happy self

Recall a time when you were happy. Looking through the eyes of your compassionate self, see yourself smiling, happy and feeling content. Let your compassionate self feel joy for the happy self. Notice what feelings come up when you focus on being ‘happy’ – strangely it might make you feel sad because happiness might seem a long way away! Or you might notice other resistances. If so, stay with these feelings as best you’re able and always pull back to just being the compassionate self if it feels overwhelming. The important practice here is creating in your mind the potential for happiness and self and support from the compassionate self. We can learn to imagine ourselves as ‘well’, ‘happy’ and free of suffering. You can extend to any other positive aspects of yourself that you wish.

Compassionate practice is not just with threat-based feelings but with positive ones too!

Compassion and kindness for others

In our next exercise we are going to imagine kindness flowing out. Some of you might find this an easier exercise than the one above, so might prefer to start here. There is now increasing evidence that if we practise trying to focus on compassion for others this stimulates key brain areas which are helpful in combating depression and anxiety.2

Recall a time when you felt very kind and caring towards someone (or if you prefer, an animal). Don’t choose a time when that person was very distressed, because then you are likely to focus on that distress. As in the experience of remembering somebody being kind to you, ensure that you have space to practise without distraction, sit comfortably and engage in your soothing rhythm breathing. Remember to create a kindly facial expression with (say) a slight smile. Notice your feelings in your body and the sense of yourself that emerges from such memories.

Next, bring to mind a person or people whom you want to feel you can help to be free of suffering. This may be a partner, a friend or a child. The idea is to practise filling your mind with compassion for another – you can choose who the other will be. Proceed with the following steps.

Imagine yourself expanding as if you are becoming more powerful and wise.

Pay attention to your body as you remember your feelings of kindness and the compassionate self.

Spend a few moments feeling this expansion and warmth in your body (but don’t worry if these feelings do not seem to be there – it is the trying that is important). Note your real genuine desire for this other person to be free of suffering and to flourish.

Spend one minute thinking about your voice tone and the kind of things you say or the kind of things you might do or want to do.

Focus now on your real desire for the person to flourish and be free of suffering. See them in your mind as smiling back at you. Focus on three key ideas (and the feelings and desire within them):

– May they be well.

– May they be happy.

– May they be free of suffering.

Spend one minute (more if you can) thinking about your pleasure in being able to be kind.

When you feel able, you may also focus on feelings of kindness in general, the feelings of warmth, the feelings of expansion, the voice tone, the wisdom in your voice and in your behavior. When you have finished the exercise you might want to make some notes about how this felt in your body.

If you want to take this practice further, you can gradually expand the circle of people to whom you send your compassion – to friends and acquaintances, then to strangers and even to people you don’t like. They too have all found themselves here with a brain they did not choose and passions, desires and feelings they did not design, and are ignorant of the forces that operate within them. However, this is more advanced practice and if you are depressed you might want to start slowly and build up. The basis of the practice is to fill your mind with desires and feelings for all living things to be free from suffering and to flourish. If you can expand your practice time to, say, five and then ten minutes. Longer would be helpful, but any time you can give to practice is useful.

Being joyful in other people’s flourishing

In this exercise we are going to focus on creating what is called sympathetic joy, which is joyfulness in the flourishing and well-being of others.

Find a place where you won’t be distracted and can sit comfortably and engage in your soothing rhythm breathing. Do that for about one minute until you feel ready to engage in the imagery. Now try and remember a time when you were very pleased for someone else’s success or happiness. Perhaps it’s someone close to you in your family; seeing them do well made you very happy. Recall their facial expressions in your mind. Feel the joy and well-being in them. As you do this, focus on your own facial expressions and feel yourself expanding as you remember the joyfulness of that event.

Notice how this joyfulness feels in your body. Allow yourself to smile. Spend two or three minutes sitting with that memory. Then, when you’re ready, let the image fade and maybe write some notes.

In the next stage you can focus on your feelings of joy for the successes or relief from suffering of others, eventually expanding this to all living things.

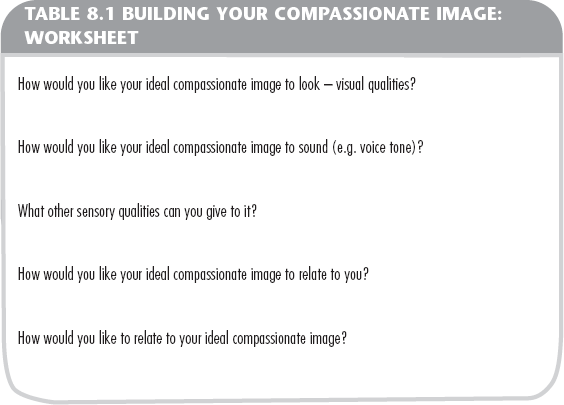

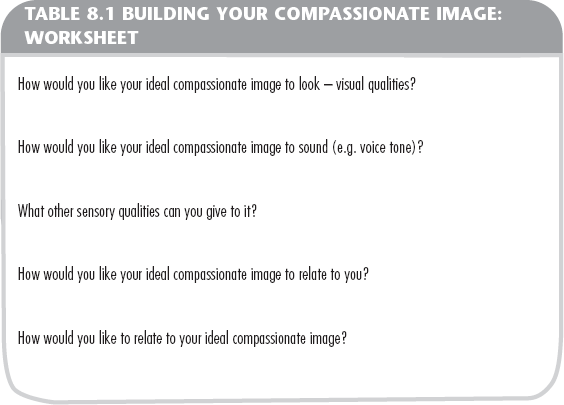

Imagining your ideal compassionate image

We are going to change the flow a bit. So far we have focused on your internal feelings of the compassionate self and being compassionate to different parts of you. Then we directed this to others and tried to fill our minds with kindness and wisdom. In the next exercises we are going to practise exploring our feelings as a recipient of compassion, by imagining another mind – wiser, stronger and warmer than our own – wanting us to be free of suffering and to flourish. I call this ‘imagining your ideal compassionate image’. Let’s now focus specifically on the ideal compassionate image that brings compassion for you. You can work on this using the worksheet on page 174.

The usual way we experience compassion is, of course, through the kindness of others. This usually flows in and through relationships. We can practise stimulating our soothing system by imagining relating to ‘compassionate others’. Just as we can imagine ideal meals or ideal sexual partners, that can stimulate our bodies and physiologies in specific ways (see page 28), so we can create inner images that can stimulate the soothing system. The idea here is to play with, create, discover, build and develop your compassionate imagery; experimenting with what works for you. In fact the idea of imagining a compassionate other, and practising and focusing our minds on that image, as a way to help ourselves develop emotionally and heal, is thousands of years old.3

Let’s think about how we might create a compassionate image that we can relate to using fantasy images. When you think of compassion, what kinds of images come to mind? Close your eyes for a moment and allow the word compassion or kindness to sit gently in your mind. What colours are associated with it for you? What sounds and textures? There is no rush. Maybe a mixture of colours and sounds come to mind.

In the next step we are going to focus on creating a specific image that you can feel has great compassion for you – that is ‘is sensitive to your suffering and has a deep wish to help you with it.’ The image that might arise could be of a person, but some people prefer animals, or even a tree or a mountain. Remember you might only get a fleeting sense of something (see pages 145–146). What are the qualities that you see as central to compassion? Spend a moment and think about that. It might be kindness, patience, wisdom, and caring. The act of thinking about compassion and its qualities helps you start to focus your attention on it. When you have had some thoughts of your own you can consider giving your image four basic qualities. We met them earlier, but let’s look at them in a bit more detail now. These qualities are:

1 Wisdom. Imagine that your compassionate image understands completely what it means to be a human being, to struggle, to suffer, to have rage, feel depressed, but also to have desires, to feel joy. It understands the evolved creation of our human minds with all their complex feelings, lusts, desires, happy and distressing thoughts, that can conflict inside us. It knows these are part of being human. Some people like the idea that their compassionate image has been through similar things to themselves but is now older and wiser; it understands you perfectly because it has been there itself. The image has a wise mind because it knows from experience, but has reached the point of inner peacefulness. This sense that it will have had the same feelings, conflicts, fantasies and emotions as you can be important as a source of kinship, and points (and can inspire us) to the ability to move on and develop.

In Buddhism certain images of compassionate others (called Bodhisattvas) are indeed like this. They have been fully human and subject to the same passions and desires, mistakes, aggressions, depressions and regrets as all of us, but through their training, study and practice have gained insight and developed compassion that has emerged from personal struggle and suffering.

2 Strength and fortitude. Give your image the ability to endure and tolerate painful things, but also the strength to defend and protect you if necessary. Imagine it as strong and courageous. As we will see later, sometimes compassion requires us to have courage. Sometimes, too, it requires us to be able to tolerate and not act on our more destructive thoughts and feelings, or learn to be assertive, or acknowledge we need to face things that we are perhaps frightened of facing.

3 Warmth and kindness. Imagine your compassionate image has warmth and kindness that radiates from and around it. This key quality is specifically there for you because this is your own unique image that you are creating and building.

4 A non-judgemental/non-condemnatory approach. Our compassionate image is never condemning, judging or critical. This does not mean it doesn’t have desires or preferences. Indeed, its main desire is for your well-being and flourishing. Nor does being non-judgemental mean it is happy to go along with whatever feeling or action you decide; but it won’t condemn you for it but rather invite you to understand your feelings and thoughts and choose a compassionate path – which at times can mean learning to be assertive.

So these are our key qualities that we are going to build into our compassionate image. The idea here is to create an image that is unique and special for you. The image is yours and yours alone. Keep in mind that it is your ideal and in that sense suffers from no human failings but is fully and completely compassionate every time because it embodies these qualities exactly. Note that the idea of it being ‘an ideal’ is that it is ideal to you (it may not be ideal to anyone else). You give it every quality that is important to you, just as if you thought about your ideal house, meal or car you would give it everything that you wanted and wouldn’t hold back. So it is with your ideal image; you imagine it to have every aspect of compassion that is important to you. Deborah Lee has referred to this aspect as your ‘perfect nurturer’ – somewhat parental-like and protective – and some people really like that idea. Others see compassion in different ways, say as a friend or mentor – so you can decide exactly what qualities it has. Again, these kinds of exercises are used by various therapists to help people.4

Some people like to use religious images, for example of Buddha or Christ. If these images are helpful then by all means use them, of course, but for the exercises we are doing here, create a new one just for you, because it also represents a creation of your mind; it is your inner sense of compassion that you are learning to give a voice to. Sometimes religious images can have associations that are not helpful – such as the concern that Christ might disapprove of sin – whereas the compassionate image we are developing here is never judgemental or punitive in any way.

Find somewhere to sit comfortably where you will not be disturbed, and decide if you want to use a CD of chants or music, or have (say) a water fountain on, or a candle or some other sensory aspect in the room. Later you may not want these additions, but they can be helpful to start with to create the mood. I know some pieces of music help me, but the choice of music can be very personal. Thinking about listening to and finding music that helps you and stimulates feelings of kindness and gentleness can itself be interesting and helpful.

Sit with eyes looking down or closed, and engage in your soothing rhythm breathing. When you feel that your body is now into the rhythm of breathing, start to imagine your ideal of compassion. Bring a slight, gentle smile to your face and consider the following questions.

If you could design for yourself your ideal compassionate ‘other’ (that may or may not be a human person) – what qualities would it have? What would it look like?

If you are struggling with this, try this exploration:

If you could design the ideal compassionate other for a child, what qualities would it have – how would it change as the child grows into an adult and what would it be like when the child is an adult?’

On page 174 there is a worksheet you can use. If you want to do this exercise then go to the worksheet now, read through the instructions, then engage your soothing rhythm breathing for 30 seconds and see what (if any) image comes to you. The idea is to do it mindfully so that if your mind wanders off task, you just bring it back.

When you are doing this exercise, go into as much sensory detail as you can. For example, think about how old the image is (if it’s a human one), the gender, type of eyes. Can you see it smiling? Do you have a sense of the hair style and colour? Do you have a sense of its clothes and postures? Next, focus on the sounds, the tone of the voice. If it communicates with you, what would it sound like to you? If there are any other sensory qualities that you would like your compassionate image to have, bring them into your exercise. One person I worked with saw a tall and bushy tree. It had been there for a long time and she felt she could snuggle into its branches and feel protected.

Think about how you would like your image to relate to you. Some people would like the image to seem older and wiser and very protective. For example, the person who thought of the tree for her compassionate image focused on its protective aspects, feeling surrounded by its branches. Other people like the idea of imagining being cared for, or cared about. One person wanted their image to truly understand how painful and difficult certain aspects of her life had been and still were. Sometimes our image may be parent-like – it can have all the qualities of the parent we always wanted, completely loving, forgiving and admiring; taking pleasure in our being. It is interesting to imagine that your compassionate image has ‘pleasure in your being’. Notice those intrusive ‘Yes, but.’ thoughts when you do this. They are common and understandable but, in this exercise, bring your attention back on task.