13

Stop criticizing and bullying yourself: Treating yourself with compassion

Humans are able to think about themselves as if they were thinking about someone else. We have feelings and make judgements about ourselves; there can be things that we like or dislike; we have relationships with ourselves that can be healing or unhelpful and even abusive. If we are honest we can think or say things to ourselves, and feel emotions (anger and contempt) towards ourselves, that we wouldn’t dream of directing towards other people. We recognize that if we treated others like that it would be abusive. But we treat ourselves like that, especially if we fail in some way, make mistakes, do things we regret, or just feel bad. At the times we need compassion, we actually give it to ourselves least. Because we believe that somehow being critical, harsh, disliking or even hating ourselves is deserved or can be good, we continue to do it. However, self-criticism, especially feelings of anger, frustration or self-contempt, is bad for your brain (see pages 28).1

This chapter encourages you to develop a more helpful and considerate response to yourself. Your sense of yourself is always with you, from the moment you wake up to the moment you go to bed. It makes sense to learn how to have a relationship that is friendly, supportive, healing and stimulates the positive emotion systems in our brain rather than the threat systems.

In depression, thoughts and feelings about oneself can become very negative. I say ‘can’ because this is not always the case. For example, I recall a woman who became depressed when the new people who moved in next door played loud music into the early hours. She tried to get the authorities to stop them, but although they were very sympathetic, they were not much help. Slowly she slipped into depression, feeling her whole life was being ruined and there was nothing she could do. However, she did not think her depression was her fault or that she was in any way inadequate, worthless, weak or bad. Her depression was focused on a loss of control over a very difficult situation.

Sometimes depression can be triggered by conflicts and splits in families or other important relationships. The depressed person may feel defeated and trapped by these relationships, but not to blame for them. Sometimes depressed people feel bad about being depressed and the effect this is having on them and others around them, but they do not feel that they are bad or inadequate as people; they blame the depression.

Nevertheless, many depressed people have a poor relationship with themselves. A poor relationship with oneself can pre-date a depression or develop with it. This chapter will explore the typical styles of ‘self-thinking and feeling’ depressed people engage in, and consider how our relationship with ourselves can be improved. All the styles discussed here can be seen as types of self-bullying. As you will see, we can bully ourselves in many different ways.1

Social comparison and self-blame

We live in a world that is very judgemental and treats us rather like objects.2 At school, being chosen to play on the football team, getting our first job and so on, we are surrounded by people who can do better than us, who we feel are more attractive, more capable, and so on. What is worse – in schools, through our media and in workplaces, we are constantly encouraged to compare ourselves with others – are we as good as them; as clever, attractive or slim; or as wanted? My research has looked at how people can feel under pressure to strive to keep up and avoid being judged as inferior. You will not be surprised to learn that the more people feel under pressure to avoid being seen as inferior compared with others, the more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression they are.3

Social comparison can be helpful because it helps us copy each other – adopting the same values, wanting the same things and trying to improve ourselves. If we fail at an important task, such as an exam or the driving test, we can feel better if we find out that others have failed too. We might feel guilty at feeling pleased they failed too, but it’s only natural to feel better when you think you’re the same as others.

Depressed people can feel that others are more talented or lucky. As children they may have felt that parents favoured their siblings, or they may feel that their siblings had an easier time growing up.4 Sometimes depressed people have many unresolved problems about these early relationships. They may feel that they have always lived in the shadow of a sibling – were less bright, less attractive and so forth. Sometimes parents and teachers have compared them unfavourably with others –‘Why can’t you be like Sam or Jane’ – or maybe they had parents who were always comparing them with others. For example, when Jane came second in class, her father’s reaction was always disappointment: ‘What’s the matter with coming first?’ His motto was, ‘Second is the first loser’. Such children grow up in an atmosphere of constant striving to compete with others to win parental approval; they never feel good enough. If you look back at pages 28–9 you can see how this can stimulate the drive system by trying to be ‘better and better or have more and more’ and never being satisfied or content. That is not your fault, but it is something you might wish to work on, to learn how to be more content and understand the roots of your striving and social comparison. Maybe it is searching for love and acceptance that underlies your striving?

Jim went to university and did well, but his brother Tom was a more practical person and not cut out for the academic life. However, instead of being happy with himself, Tom constantly compared himself with Jim and felt a failure. He would say, ‘Why couldn’t I have been the bright one?’

Babs’ mother was often ill, and as the older daughter she took on responsibility for caring for her. However, she didn’t feel appreciated for the role and grew up feeling secretly resentful, but always putting other people first and presenting herself as a nice person. Her anger at the situation, added to thoughts of how ‘compared with her’, her siblings had an easier life, fuelled her depression.

Even though social comparison can give us lots of problems, it’s interesting that sometimes we don’t compare ourselves with Mr or Ms Average or people who are similar to ourselves. Jane, a mother of two who devoted herself to looking after her children, had a number of friends who went out to work even though they had children too. Jane thought, ‘I’m not as competent as them because I don’t go out to work, and I have to struggle just to keep the home going’. When I asked her if she had other friends with children who did not have outside employment, she agreed that most of her friends didn’t. However, it was not them she compared herself with, but the few who did have jobs. Part of the reason for selecting people like this is that we slightly envy them; we want to be like them.

Sometimes when we compare ourselves unfavourably with others, we also think that other people will have the same judgement of us. Other people will see us as inferior or bad in some way – that we are not as good as other people (recall ‘Mind reading’ on page 207). This can be quite a major problem if we have to open our hearts and share our difficulties.

A young mother’s comparison

Diane felt really depressed after the birth of her child. She found it difficult to feel ‘affection’ for her new baby. She thought that her reaction was different from that of all her friends and therefore there was something wrong with her to feel this way. She was angry and frightened about her depressed feelings and envied what she saw as her friends being happy mothers. As a result, she never told anyone but suffered in silence, feeling different from them and cut off. Had she opened up to others (rather than feeling shamed by her comparisons) she would have found that these are sadly not uncommon experiences, and are no fault of her own – hormonal readjustment can be really unpleasant and play havoc with our minds.

One of the big benefits in working in group therapy is the degree to which people are prepared to share their problems. Often when one person is brave enough to own up to certain types of negative feelings or experiences, other people feel able to share. Indeed, sharing is much easier when we no longer compare ourselves unfavourably with others but realize we are all in this same boat of living in a world of suffering and hardship.

Even those with status can feel inferior

Social comparison is one reason why people who seem to have quite prestigious positions in society can become depressed. I worked with a doctor who had done well during his training yet, when he qualified, found the work stressful. He thought that he was doing much worse than his colleagues. Compared with them, he did not feel confident or on a par. As a caring GP he took more time with his patients and then struggled to keep up – but then blamed himself.

Balancing social comparison

Although it can be very difficult to avoid making social comparisons, here are some ideas to think through to help you think about how social comparison works within you.

When you compare yourself with others, choose a target who is most like you. In other words, avoid comparing yourself with those who are clearly a lot better in certain ways. If a comparison turns out badly, consider the reasons and evidence why this comparison may not be an appropriate one for you. We have different genes, backgrounds, talents and abilities – it is not a level playing field.

Think about the reasons for your comparison. Although comparing ourselves with others is very natural, recognize that it can be harmful and keep in mind why you want to do it – what’s the point of it for you? If it has value, such as giving you something you can try to copy, or it inspires you, that’s fine, but if it depresses you – not fine.

If you do compare and feel down, avoid attacking yourself. Try to remember that there are always people who are better at doing certain things or have more, but it does not make you a failure or inadequate because you can’t do these things or don’t have as much.

Think of your life as your own unique journey, with its own unique ups and downs and challenges. Although you might want to live the life of someone else, this is not possible. Focus on you as yourself rather than you as compared with others.

If you are depressed, avoid labelling yourself as inadequate because you think others don’t get depressed. Sadly, many people do get depressed and anxious.

Spend some time refocusing and thinking about how social comparison can be hurtful for so many of us. It is understandable, but think of ways of dealing with it that are kind to yourself.

Self-blame can come from fear

Self-blame and criticism are strongly linked to depression. When people self-blame and self-condemn, there is often a sense of the fear (e.g., of being rejected for mistakes or for not being good enough) and loss. Sometimes we learn to self-blame because we are frightened. Consider this on a world scale. Over thousands of years humans have been very frightened about what life can throw at them. Their children can die of numerous diseases, there can be famines and droughts and all kinds of unpleasant things. In societies throughout the world humans often imagine and then appeal to various gods who might be able to control bad things. Then they have to get them on side and they usually do this by sacrificing, appeasing or promising obedience to the chosen god. Problems arise if this does not work. The following year the diseases still come and so do the droughts, famines and other bad things. People rarely give up on their god as a poor bet; more commonly they blame themselves. They feel they must have done something wrong, or not done things sufficiently right, and have caused offence or displeasure to the god. Self-monitoring one’s behavior, to check if it is acceptable – and then self-blaming if one thinks it is not – are common if we grow in fear of others. Sometimes in these societies if the gods do not help out there is a blaming of other people, ‘Maybe it was those people who broke the traditions and caused the gods to abandon us’ – and so starts a round of persecution born out of fear.

When we believe that powerful others and people can help, love or hurt us – and when we’re children it is parents and teachers who can indeed do those things – it is natural for us to monitor ourselves, trying not to make them angry with us or to withdraw support and affection. Because we are monitoring ourselves, if things go wrong, we blame ourselves. If parents are in a bad mood, we might wonder what we have done to upset them. Thus a natural style of self-monitoring and self-blaming can become a style we carry through life. It is useful to remember that a style we learned out of fear – wanting to please and blaming ourselves, wanting to be loved or protected and not harmed – can become a style we use in all kinds of situations. We may never have learned to see the origins of our self-blaming style as being rooted in fear and wanting love.

If you tend to blame yourself, often worrying if you’ve upset people, not done well enough or have various faults – always try to think about what you are really frightened of. Next, write down the reasons why these might be linked to your fears (of rejection, or people becoming angry). You might not be fully conscious of them at first. Consider if these styles have been picked up in childhood. If so, with your compassionate self-focus, consider the possibility that you are blaming yourself not because you really are to blame, but because it feels safer to self-blame and to protect yourself – just like the people who blame themselves if their gods don’t come through for them. If it is about fear, safety and protection, then be honest about this, rather than thinking your self-blame reflects any truth about you!

Taking too much responsibility

Blaming occurs when we look for the reasons or causes of things – why did such and such a thing happen? When we are depressed, we often feel a great sense of responsibility for negative events and so blame ourselves. As noted above, the reasons for this are complex. Sometimes we self-blame because as children we were taught to. Whenever things went wrong in the family, we tended to get the blame. Even young children who are sexually abused can be told that they are to blame for it – which, of course, is absurd. Sadly, adults who are looking for someone to blame can simply pick on those least able to defend themselves.

Sylvia was a harsh self-blamer. Her mother had frequently blamed her for ‘making her life a constant misery’. Her mother was herself a depressed and angry person, but Sylvia accepted her mother’s explanations at face value – as children do. Not surprising, then, Sylvia took this style of thinking into adulthood and tended to blame herself whenever other people close to her had difficulties. Yet when Sylvia looked at the evidence, she realized that her mother’s life was unhappy for a number of reasons, including a difficult marriage and money worries. As a child Sylvia could not see this wider perspective, but believed what her mother told her. Sylvia had to learn that her self-blame was a style she had picked up in childhood, and practise a more balanced approach. Sometimes, of course, this is quite frightening because it raises a number of other issues about the kind of person she is and the anger she might now feel.

When people are depressed, their self-blaming can become extreme. When bad things happen or conflicts arise, they may see them as completely their fault. This is called personalization – the tendency to assume responsibility for things that are either not our fault or only partly so. However, most life events are a combination of various circumstances. When we are depressed, it is often helpful to stand back and think of as many reasons as possible about why something happened the way it did. We can learn to consider alternative explanations rather than just blame ourselves.

The responsibility circle

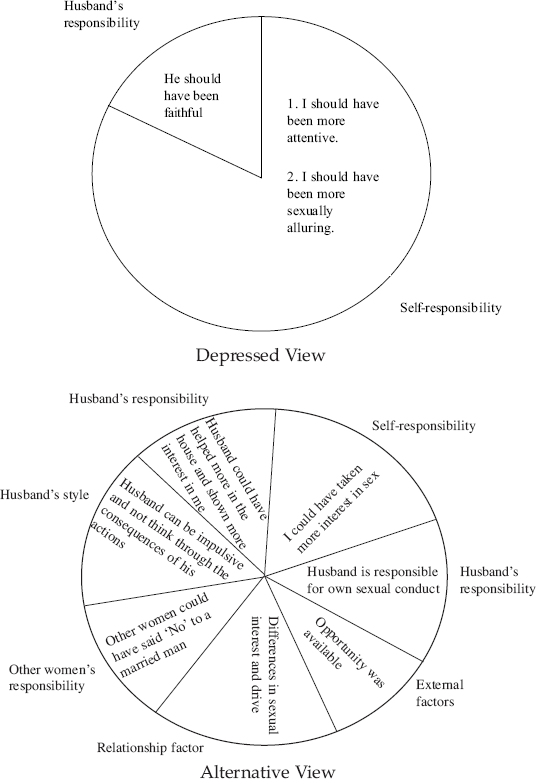

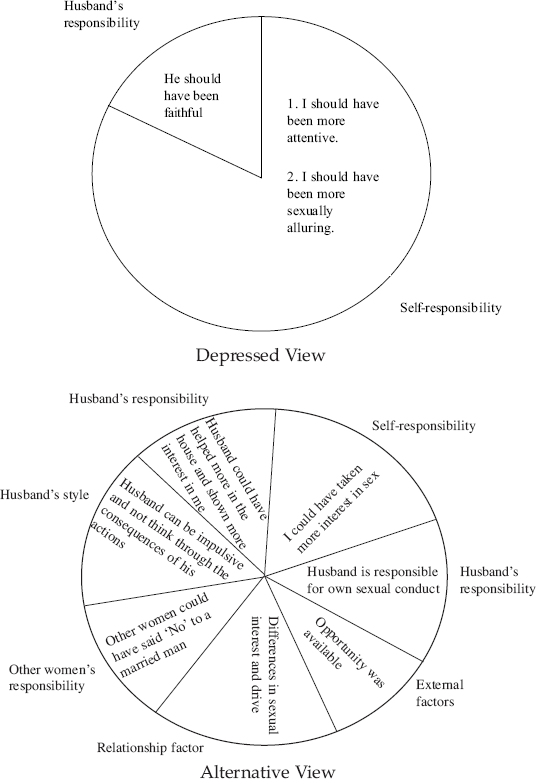

Many of the things that happen to us are due to many reasons. Here is an example to help you think about this. Sheila’s husband had an affair, for which she blamed herself. Her thinking was: ‘If I had been more attentive, he would not have had an affair. If I had been more sexually alluring, he would not have had an affair. If I had been more interesting as a person and less focused on the children, he would not have had an affair.’ All her thoughts were focused on herself. However, she could have had alternative thoughts. For example, she could have thought: ‘He could have taken more responsibility for the children, then I wouldn’t have felt so overloaded. He could have spent more time at home. If he had been more attentive in his lovemaking, I might have felt more sexually inclined. Even if he felt attracted to another woman, he did not have to act on it. The other woman could have realized he was married and not encouraged him.’

One can then write down these various alternatives side by side and rate them in terms of percentage of truth. Or one might draw a circle and for each reason allocate a slice of the circle. The size of each slice represents the percentage of truth. In Figure 13.1 you can see how this worked for Sheila. The two circles represent a depressed view and a more balanced view. Note how some situations often have many causes. Sheila’s more balanced, ‘alternative view’ circle seemed more true to her once she had considered it.

Figure 13.1 ‘Responsibility circles’.

The next thing to do is to go around the circle carefully and think about it in as compassionate, warm, kind and understanding a way as you can. Try and create those feelings in your mind as you consider the alternatives.

Think about the fact that if we take too much responsibility on our own shoulders then we are robbing other people of theirs. In parent–child relationships this can be very important. If parents feel guilt and blame themselves for their children’s difficult or bad behavior, how are the children ever going to learn to take responsibility?

Tess had been depressed when her son Sam was born. Later on, she always blamed this for Sam’s difficult behavior. The family therapist spotted this and noted that Sam had few boundaries because Tess always blamed herself for his behavior. She could not confront Sam and help him become responsible for himself and his behavior.

Compassionate behavior is about giving people what they need, not necessarily what they want. When it comes to responsibility, don’t be greedy and claim more that your fair share!

The same principle can apply when we blame others. We may simply blame them without considering the complexity of the issue, and label them as bad, weak and so forth.

Self-blame and control

One reason we might self-blame is that, paradoxically, it might offer hope. For example, if a certain event is our fault, we have a chance of changing things in the future. We have (potential) control over it and so don’t have to face the possibility that, maybe, we actually don’t have much control. In depression, it is sometimes important to exert more control over our lives, but it is also important to know our limits and what we cannot control. Sheila had to face the fact that she could not control her husband’s sexual conduct. It was his responsibility, not hers. We have to be careful that, in self-blaming, we are not trying to give ourselves more control (and power) than we actually have (or had). We will look at this in regard to shame and abuse on pages 388–89.

Avoiding conflict and anger

Another reason for self-blame is that it may feel safer to blame ourselves than to blame others. By self-blaming we might avoid conflicts and expressing our own anger. You will need to be honest about this – how frightened of your anger are you? How much do you think it could turn you into an unlovable person? Remember the example above of the blaming ourselves if the gods don’t help out or seem punitive (see pages 281–2) – sometimes we can be very frightened of anger and conflicts, and it is out of fear that we self-blame.

It may be that self-blame keeps the peace and stops us from having to challenge others. If, when we were children, our parents told us that they hit us because we were bad in some way, we might have accepted their view and rarely argued. This attitude can be carried on into adulthood. The other person always seems blameless, beyond rebuke.

People can be in conflict and in dilemmas about blame. One part of the self can feel angry, but another part can feel sorry or disloyal to (say) a parent. There can be a real desire to avoid conflict, and not wanting to be seen as ungrateful, aggressive or bad. The problem is, of course, that conflicts are part of life.

Sometimes we recognize that we are not totally blameless in something, but when it comes to arguing our case, the part that is our responsibility gets blown up out of proportion. We become over-focused on it and feel that we have not got a leg to stand on. However, most things in life have many causes, and the idea here is to avoid all-or-nothing thinking. By all means, accept your share of responsibility – none of us is an angel – but don’t overdo it. Healing comes from forgiving yourself and others.

Expecting punishment

When bad things happen, depressed people sometimes feel that they are being punished for being bad in some way. It is as if we believe that good things will only happen if we are good and only bad things will happen if we are bad. If bad things happen, this must be because we have been bad, or simply are bad. When Kate lost a child to sudden infant death syndrome, she felt that God was punishing her for having had an abortion some years earlier. But millions of women have abortions and don’t suffer this event, and vast numbers who suffer this sad event have not had abortions.

In depression the sense of being punished can be quite strong, and quite often, if this is explored, it turns out to relate to a person’s own shame about something in the past. For instance, Richard’s parents had given him strong messages that masturbation was bad. When he began doing it when he was twelve, he enjoyed it but also felt terribly ashamed. For many years, he carried the belief that he was bad for enjoying masturbating and sooner or later he was going to be punished for it. When bad things happened to him, he would feel that these were ‘part of his punishment’.

To come to terms with these feelings we usually have to admit to the things we feel shame about and then learn how to forgive ourselves for them. It can be difficult to come to terms with the fact that the principles of ‘justice’ and ‘punishment’ are human creations. There is no justice in people starving to death from droughts in Africa. Good and bad things can happen to people whether they behave well or badly.

The fear of punishment can also come when we have had parents who frequently lost their temper and became very aggressive. Abigail’s mother could be loving but at times would have rages and be physically aggressive. Clearly, those events created intense fear in Abigail. It is quite understandable that if there were conflicts or things went wrong, Abigail’s threat-protection system would spring into action and she’d have an internal fear that something very bad or threatening was going to happen.

Expectations of punishment can operate at an emotional or gut level. It is important to stand back from that and realize what’s happening inside. We can then practise our soothing rhythm breathing (see pages 123–4), and recognize that our feelings make sense, but we can allow ourselves to be gentle with them now.

Note that Abigail had the classic problem of wanting love from a person who could also be dangerous. This is very tough, because different parts of her brain are in conflict. The part that wants to be close to a loving mother and yearns for protection pulls her forward while the threat self-protection system pushes her away. These are difficult and confusing feelings to have to deal with and can really scramble our minds. If Abigail gets close to people this might reactivate her fear that people she’s close to can blow up at her.

Some people can fear the punishment of Hell. But here’s how I see it. If you believe in Heaven then it’s kind and loving people who go there, right? And these are people who do not like others to suffer. So Heaven is full of those who would work to stop the suffering of others – so if Heaven if full of such souls, who could rest knowing people suffer in Hell – so how can Hell exist? For me it is our own minds that create these fears.

Some people believe that self-criticism is the only way to make them do things. For example, a person might say, ‘If I didn’t kick myself, I’d never do anything.’ Or they might believe that unless they are critical and keep themselves on their toes they will become arrogant, selfish and lazy. They use their self-bullying part to drive them on – sometimes in rather sadomasochistic ways. Such a person may believe that threats and punishments are the best ways to get things done. In some cases, this view goes back to childhood. Parents may have said things like, ‘If I didn’t always get on at you, you wouldn’t do anything’, or ‘Punishment is the only thing that works with you’. They may also have been poor at paying attention to good conduct and praising it, and rather more attentive to bad conduct and quick to punish. As a result, the child becomes good at self-criticism and self-punishment but poor at self-rewarding and valuing. See Table 13.1 for ways to look at this differently.

In depression, however, self-criticism can get out of hand. The internal bully/critic becomes so forceful that we can feel totally beaten down by it. Then, when we are disappointed about things or find out that our conduct has fallen short of our ideal in some way, we can become angry and frustrated and launch savage attacks on ourselves. Research has shown that it is the emotions of anger and contempt in the attacks, not just the kind of things you think or say to yourself, that really do the damage in self-attack.5

It–me

The late Albert Ellis pointed out that self-criticism can lead to an ‘it–me problem’: ‘I only accept me if I do it well.’ The ‘it’ can be anything you happen to judge as important. For example, if you are a student, the ‘it’ may be passing exams. You might feel good and content with yourself if you pass or do well, but become critical and unpleasant with yourself if you do less well. Your feeling of disappointment fuels negative feelings of yourself. Or the ‘it’ might be coping with housework or a job: ‘I only feel a good and worthwhile person if I do these things well.’ Success leads to self-acceptance, but failure leads to self-dislike and self-attacking. Not only may you feel like this, but you might have beliefs where you think it’s true: ‘I’m not worthwhile if I can’t succeed at things’.

This kind of thinking means: ‘I am only as good as my last performance’. But how much does success or failure actually change us? Do you really become good (as a person) if you succeed and become bad (as a person) if you fail? Whether we succeed or fail, we have not gained or lost any brain cells; we have not grown an extra arm; our hair, eyes and taste in music have not changed. The consciousness that is the essence of our being has not changed. It is like water that can carry good or bad things but the water itself is not those things. Of course, we may lose things that have importance to us if we fail. We may feel terribly disappointed or grieve for what is lost and what we can’t have. But the point is that these things will be more difficult to cope with if our disappointment becomes an attack on ourselves and we label ourselves rather than our actions as disappointing. It is very helpful to pull back and reflect on feelings of disappointment and consider if these feelings have somehow got linked to your feelings about yourself. If so, imagine your mind separating them and saying clearly ‘I am upset about this or that – but this is not about me or the essence of me’.

Another key way to work on this ‘it–me’ problem is to separate self-rating and judgements from behavior rating and judgements. It may be true that your behavior falls short of what you would like, but this does not change the complexity and essence of you as a person. We can be disappointed in our behavior (and we can all do some daft, thoughtless and unhelpful things), but as human beings, we do not have to rate ourselves in such all-or-nothing terms as ‘good’ or ‘bad’, ‘worthwhile’ or ‘worthless’. If we do that, we are giving away our humanity and turning ourselves into objects with a market value. We are saying, ‘I can be treated like a car, soap powder or some other thing. If I perform well, I deserve to be valued. If I don’t perform well, I am worthless junk.’ But we are not things or objects. We are living, feeling, highly complex conscious beings, and to judge ourselves as if we are just objects carries great risks.

Self-attacking

Recent research has suggested it is our emotions and response to self-criticism that are associated with depression.5 Our research has also shown that people criticize themselves for different reasons. Sometimes it’s because they want to drive themselves to be better, but at other times it’s out of rage and hatred and just wanting to hurt themselves.6 We might make a mistake, have an argument with somebody, or eat too much and put on a few pounds, and realize that we could have behaved better. We might offer a mild rebuke to ourselves, or try to learn from things. However, when we attack ourselves there are emotions of frustration and anger and sometimes even contempt and shame. It is these feelings that we put into our self-criticism that turn it into much more of an attack on ourselves.

When self-criticism becomes hostile and activates basic beliefs about ourselves (of being weak, bad, inadequate, hopeless, and so on), then depression can take root. We all have a tendency to be self-critical, but when we become angry, frustrated and aggressive with ourselves and start bullying and labelling ourselves as worthless, bad or weak, we are more likely to slip deeper into depression. In a way, we become enemies to ourselves; we lose our capacity for inner compassion. It is as if the self becomes trapped in certain ways of feeling and then (because of emotional reasoning) over-identifies with these feelings. We think our feelings are true reflections of ourselves: ‘I feel stupid/worthless, therefore I am stupid/worthless.’

Here are some ideas about how to work with these difficulties:

If I am honest, my self-criticism and attacking happens because I feel frightened about my mistakes or areas where I feel inferior. This fuels my frustration and anger with myself. Maybe I need to come to terms with what I am actually frightened about. (Spend some moments quietly reflecting on how your self-criticism links to your fears. What is the fear that underlies your criticism and anger with yourself?)

How can I be compassionate to that fear?

To sum up a person (e.g., myself) in simple terms of good/bad, worthwhile/worthless is all-or-nothing thinking. It is compassionate to appreciate that there are some things I can do quite well and some things I don’t do as well as I would like.

All humans are fallible; we make mistakes, mess things up, behave selfishly – all we can do is try our best to improve. Self-attacking does not really help me with this (see Table 13.1).

Because I feel stupid and worthless does not make it true. I’m confusing a feeling with a sense of self.

The idea of worth can be applied to objects such as cars or soap powder but not to people.

I don’t have to treat myself as an object, whose only value is what I achieve or do.

If I say ‘worthless’, it is just one of a number of possible feelings that I, as a human being, can have about myself. I can try and put these critical feelings in perspective.

I would not treat a friend like this – and anyway I am on the path of compassion, so that is what I am trying to develop step by step.

If I had a chance to change the world I would not issue a command that everyone who fails should feel worthless – quite the opposite (a patient came up with this idea, which I think is very interesting and helpful).

Remember these thoughts and reflections have to pass the ‘compassionate friend’ test: Would you say this to a friend? Would you help a friend in this way? Would you agree that it is a kind and nurturing thing to think, say or do?

Self-hatred

As I have mentioned, it is the fear-linked and hostile emotions lurking in the self-criticism that often do the damage. Getting more insight into these emotions and some control over them can be very helpful. At the extreme, some depressions involve not only self-criticism and self-attack, but also self-hatred.7 This is not just a sense of disappointment in the self; the self is actually treated like a hated enemy. Whereas self-criticism often comes from disappointment and a desire to do better, self-hatred is not focused on the need to do better. It is focused on a desire to destroy and abolish.

Sometimes along with self-hatred are feelings of self-disgust. Disgust is an interesting feeling and usually involves the desire to get rid of or expel the thing we are disgusted by. In self-hatred, part of us may judge ourselves to be disgusting, bad or evil. When we have these feelings, there may be a strong desire to attack ourselves in quite a savage way – not just because we are disappointed and feel let down, but because we have really come to hate parts of ourselves.

Kate could become overpowered by feelings of anxiety and worthlessness. When things did not work out right, or she got into conflicts with others, she’d feel intense rage. Even while she was having these feelings, she was also having thoughts and feelings of intense hatred towards herself. Her internal bully was really sadistic. She had thoughts like: ‘You’re a pathetic creature, a whining, useless piece of shit.’ Frequently the labels people use when they hate themselves are those that invite feelings of disgust (e.g., ‘shit’). Kate had been sexually abused, and at times she hated her genitals and wanted to ‘take a knife to them’. In extreme cases, self-hatred can lead to serious self-harming.

Kate’s difficulties came to light in therapy, and for these types of extreme problem, therapy may be essential, but they are helpful to think about on your own too, because it is important to try to work out, and see if your bullying, self-critical side has become more than critical and has turned to self-dislike or self-hatred. Even though you may be disappointed in yourself and the state you are in, can you still maintain a reasonably friendly relationship with your inner self?

If your internal bully is getting out of hand, you may want to try the following: In as warm and friendly a way as you can manage, say to yourself:

I understand that my self-hatred is highly destructive – certainly not very compassionate.

Am I a person who values hatred?

If I don’t value hatred and can see how destructive it is, maybe I can learn to heal this part of myself.

I know perfectly well that, if I cared for someone, I would not treat them with hatred.

Am I as bad as Hitler? No? Then maybe I need to get my hatred into perspective.

Maybe I have learned to hate myself because of the way others have treated me. If I attack myself, I am only repeating what they did to me.

I can learn to be gentle to my hatred – just be in compassionate self mode and then see how hate covers up hurt and fear. Gosh, that might be tough! But that is the compassionate path I’d like to take, even if it is small steps at a time.

First, I commit myself to recognizing my self-hating part as understandable but unhelpful, linked to hurt – and then build on my desire to heal it.

We need to consider, too, that we hate what hurts us or causes us pain. Rather than focusing on hatred, it is useful to focus on what the pain and hurt is about. If you discover that there are elements of self-hatred in your depression, don’t turn this insight into another attack.

The tough part in all this is that you will need to be absolutely honest with yourself and decide whether or not you want hatred to live in you. When you decide that you do not, you can train yourself to become its master rather than allowing it to master you. However, if you are secretly on the side of self-hatred and think it’s reasonable and acceptable to hate yourself, this will be very difficult to do, and it will be hard to open yourself to gentleness and healing. For some people, this is a most soul-searching journey. But as one patient told me:

And, of course, it is not just with depression that coming to terms with and conquering hatred can be helpful. Many of our problems of living together in the world today could be helped if we worked on this. We all have the potential to hate – there is nothing abnormal about it. The primary question is, how much will we feed our hatred?

Developing compassionate self-correction to replace harsh self-criticism

In this difficult and painful life, when we make mistakes, things don’t work out, or we do things we deeply regret, learning to be kind to ourselves is the most important lesson to help us with depression. The first thing is to decide if you are actually frightened of giving up the self-criticism and self-bullying. If you ask people to imagine what life would be like if they gave up self-criticism and self-bullying altogether, they can actually be quite puzzled and even frightened. They may believe they would not achieve anything; would become lazy, arrogant or unkind. It’s almost impossible for them to believe that they wouldn’t become lazy because they have a genuine wish to do well and a genuine wish to be kind.

The first thing is to make a distinction between what I call compassionate self-correction and shame-focused self-criticism or self-bullying. They are outlined and contrasted in Table 13.1. Compassionate self-correction is based on being open-hearted and honest about our mistakes with a genuine wish to improve and learn from them. No one wakes up in the morning and thinks to themselves, ‘Oh, I think I will make a real cock-up of things today, just for the hell of it’. Most of us would like to do well, most of us would like to avoid mistakes, most of us would like to avoid being out of control with our temper. We need to recognize that our genuine wish is to improve. Self-criticism, on the other hand, comes from a fear- and anger-based place. It is concerned with punishment and is usually backward-looking, related to things we have done in the past. The problem is you cannot change a single moment of the past, you can only change the future.

To appreciate the differences between compassionate self-correction and shame-based self-attacking, imagine a child who is learning a new skill but is struggling and making mistakes. A critical teacher will focus on those mistakes, point out what the child is doing wrong, appear slightly irritated, imply that the child is not concentrating or could do better if they try. The focus of that style of teaching is based on fear and shame – to make a child frightened or to feel bad if they don’t do well. In contrast, consider a kind teacher who focuses on what a child does well and shows them how they can improve and learn from mistakes, and genuinely takes pleasure in the child’s learning. Which technique do you think will help the child the most? Which one would you prefer?

If you do things wrong or make mistakes there is going to be regret, and momentary flashes of irritation, anger and perhaps calling yourself names. The point is though, how long do you stay here? How quickly can you switch to a compassionate refo-cusing?

TABLE 13.1 DISTINGUISHING COMPASSIONATE SELF- CORRECTION FROM SHAME-BASED SELF-ATTACKING

|

Shame-based self-attacking |

Compassionate self-correction |

|

Focuses on the desire to condemn and punish |

Focuses on the desire to improve |

|

Punishes past errors and is often backward-looking |

Emphasizes growth and enhancement |

|

Is given with anger, frustration contempt, disappointment |

Is forward-looking |

|

Concentrates on deficits and fear of exposure |

Is given with encouragement, support, kindness |

|

Focuses on a ‘global’ sense of self |

Builds on positives (e.g. seeing what you did well and then considering learning points) |

|

Includes a high fear of failure |

Focuses on attributes and specific qualities of self |

|

Increases chances of avoidance and withdrawal |

Emphasizes hope for success Increases the chances of engaging with difficult things |

|

Consider example of critical teacher with child who is struggling: |

Consider example of encouraging, supportive teacher with child who is struggling: |

Overview

The way we treat ourselves is quite complex, but the basic question is, can we be a friend to ourselves when things go wrong and we mess up? It is easy to criticize – critics are ten a penny. Compassionate self support is harder but well worth working for. One patient reflected on her depression and eventually recognized that her depression was strongly linked to her self-condemnation. ‘I condemned myself into depression,’ she said. ‘That was all that was in my head, but now there are compassionate alternatives and different feelings about myself.’

We can attack ourselves without really realizing what we are doing. Our feelings and moods seem to carry us along into certain styles of thinking and evaluating ourselves.

If we are to climb out of depression, we may have to take a good look at ourselves and decide to deal with and heal our self-criticisms, anger and self-hatred.

The hard part can be helping ourselves to focus on the need for inner healing. Once we have done that, we can then start to focus on what we need to do to be healed. Often the first step is to sort out our relationships with ourselves.

EXERCISES

Exercise 1

The first steps are to use our rational and cognitive approach to examine self-criticism. The next exercises will use a more compassion-focused approach to work with our inner self-critic. So we can begin:

Consider whether you have an underlying sense of inferiority, with a sense of being not quite up to it compared to others. (To be honest, many people do have that lurking sense and it’s when it gets out of hand that it becomes really problematic.)

Think about whether this is because you have a sense of disappointment, and if related to disappointment is it a sense of fear of, say, rejection or being left behind?

If so, when something happens and you feel bad about yourself, ask yourself: ‘What am I saying about myself? What does this mean about me?’ Write down these thoughts. Try to clarify the key streams of thinking:

– what you think others might be thinking about you

– what you are thinking about yourself.

Look at those thoughts and then:

Consider in what ways you might be using: all-or-nothing thinking, emotional reasoning, disbelieving positives (see Chapter 10).

Using your ‘thought form’, focus on the fourth column (see Appendix 1). Use your rational/compassionate mind to generate alternative views about yourself.

Consider how you might help someone like yourself deal with self-attacking and bullying themselves, and then apply this to yourself. Learn to be gentle with yourself.

Imagine a really caring person advising you. What would they say? Look at the evidence and think of alternatives. Ask yourself: How am I looking after myself with these thoughts/feelings? Do my thoughts help me to care for or look after myself?’ In this way, slowly build up your insights.

Exercise 2

You probably have a sense of the kind of things you say and feel about yourself when you are in that frustrated or disappointed self-critical state. You know what your inner critic says and the kind of attacks it launches. It might have grown from childhood or even started as someone else’s criticism of you. We are now going to work with this inner self-criticism and bullying in a different way, first using our compassionate image.

Set some time aside and then sit or lie comfortably and engage in your soothing rhythm breathing. Create your compassionate self inside of you (see pages 149–151). Imagine that you have all of the ideal qualities of kindness, wisdom (you know how difficult our evolved brains are), strength and maturity, and are never condemning. It is you at your best and how you would most like to be. Spend some minutes really focusing on those, remember to adopt a compassionate facial expression and if possible a relaxed body. Feel yourself expanding as if you are becoming powerful in a calm, confident and very benevolent way. When you feel some degree of contact with those feelings you can try this exercise. Imagine your self-critical side as a person, as if you could take it out of your head and look at it. Now, in front of you, imagine yourself being critical to yourself. See the facial expressions and look at the emotions that self-critical part of you directs at yourself. Now see beyond those emotions, to the disappointment or the fear. Extend your compassion to your critical self. You’re not arguing or trying to change the critical self, and it doesn’t matter how your critical self wants to respond, even by devaluing what you’re doing or ridiculing it. Continue to feel compassion for it and watch what happens. Offer it as much compassion as it needs. One patient told me her self-critical side lifted two fingers to the compassionate self, with words to go with the gesture, but she stayed in compassion mode and gradually the self-critic ‘got smaller and then seemed rather sad, really’.

A variation on this can be to engage in your soothing rhythm breathing and then imagine your compassionate image (see page 156) standing next to you and then both of you extend compassion to your critical self. Again, note what happens. If feelings emerge, be mindful of those feelings and stay with them.

A third exercise involves writing a compassionate letter to one’s self-critical side or inner bully. The letter might look like this:

Dear inner critic,

I know that you get frustrated and upset and become angry with me. This is because you are frightened of what will happen if we don’t succeed/achieve/change etc. Actually, like me, you want to be respected, loved, cared for or admired – the basic human wants. The thing is, you worry that all these things will slip through your fingers unless we get our act together. Look, I understand your fear. I also understand that your response is to panic and lash out like this. I’m very sorry you feel so vulnerable. It’s not your fault but this attacking actually contributes to our feelings of vulnerability and depression, and so it’s time to learn how to be gentle and kind in these situations. We can learn to do the things that will genuinely move us forward in life. In your heart you know this. So I’m not going to attend to the things you say as much as I used to, okay? I used to get caught up in them and believe that these thoughts had some truth to them, but they don’t really – it’s just that we’re frightened of rejection. But if I am honest and compassionate I can learn how to cope with rejection if it comes.

Writing these letters can help you develop a different attitude to your self-critic, and become more aware of when that part of you – linked to your feelings of anger, frustration and fear – kicks in. That then becomes the signal to switch to your soothing breathing rhythm and compassionate-balanced focusing.

As with all these exercises, go one step at a time and only engage in things that you find helpful to you, and can see the point of. One of the key elements of helping ourselves is to work out what is helpful to us, because what might be helpful to me may not be helpful to you and vice versa.

In this case imagine your inner critic, and then from your compassionate self recognize that you do not need to keep this ‘voice from the past’. It was not there to really help you. So now imagine that you are leaving it and see it gradually move away and grow smaller, smaller, smaller. You are creating in your mind ‘letting-go conditions’. If this is too difficult and you think it could be a major source for your depression, then maybe professional help would be useful for you.

Sometimes the voice of the critic might remind you of someone who was unkind or even abusive to you. Here you might need a more assertive response. Remember, compassion is not submissive or weak. Finding what works for you can be key here.

14

Depressed ways of experiencing ourselves: How compassionate re-focusing can change our experience

The last chapter focused on thoughts and feelings against the self. This chapter explores how we label ourselves and think and feel about ourselves in unkind ways. Learning to spot and counter these ways of experiencing ourselves can help with depression.

Self-labelling and the different types of self

Most of us have had the experience of feeling bad, inadequate and useless at times. These feelings usually arise when we are disappointed by our actions, have failed at something or have been criticized by others. As we grow up, our parents, teachers, siblings and peers label us in various ways and may call us things that are hurtful. We may be told that we are a nuisance, bad, unlovable, stupid. Or perhaps overprotective parents say that we are not able to make our own decisions or cannot cope by ourselves. Over time, we develop various ways of thinking about ourselves as being a certain kind of person – that is, we come to label and describe ourselves in various ways. Now the label can colour the experience.

We can often label and experience ourselves differently in different roles. For example, suppose you write to a pen friend – how would you describe yourself? Suppose you are applying for a job – how would you describe yourself? If you are writing to a dating agency, how would you describe yourself? Finally, if you are writing to a priest or someone similar to confess something and seek forgiveness, how would you describe yourself then? The chances are that each letter would say different things about you, because we humans are very complex and have many different qualities and parts. In fact many psychologists suggest we have many different types of self and potential selves within us. We can play different roles with different people. With some people we might be light and humorous, but with others we might feel irritable and tense, and with others again we have a sense of unease or anxiety around them. And of course different situations seem to draw out or activate different aspects of ourselves. I am happy to talk to an audience about my specialist field, but put me in a car and tell me to drive to London and you’ll fill me full of dread and anxiety.

When we become depressed, the richness, variety and vitality of our many and potential selves drain away and we start thinking of ourselves in rather simple terms, or labels. The labels might be triggered by life events. For instance, you might be rejected by someone you love and then label yourself as unlovable. Or you might fail at some important task and then label yourself as a failure. Negative labels are often sparked off by negative feelings, which in turn may be strong echoes from the past.

Self-labelling is essentially a form of name-calling. In depression, we come to experience ourselves as if that label (e.g., weak, inadequate, worthless, bad) sums up the whole truth about us. It can feel as if we are the label: our whole self becomes identified with the label. The judgements, labels and feelings that we have about ourselves when we are depressed tend to be the same the world over. Whether we live in China, the United States or Europe, depression often speaks with the same voice. Here are some of the words depressed people typically use to describe themselves:

|

bad |

inadequate |

outsider |

unlovable |

|

empty |

incompetent |

rejectable |

useless |

|

failure |

inferior |

small |

victim |

|

fake |

loser |

ugly |

weak |

|

hopeless |

nuisance |

unattractive |

worthless |

Consider for a moment a person you care about. How do you think they would feel if you started to call them these names? Whenever they made a mistake, you called them incompetent or a failure. Of course, it would make them pretty miserable or they’d sack you as a friend. It is no different from your own self-treatment, though. It is easily done but very unhelpful. The trick is to learn to be kind and balanced in our relationships with ourselves when the going gets tough, when we fall over, when we make mistakes, when we are rejected.

However, we can train our minds to realize that the feeling and label of being ‘worthless or useless’ is only one of many possible sets of judgements. There are others, such as: honest, hard-working, carer, helper, lover, old, young, lover of rock music and chocolate, gardener. Our depressed negative judgements, which seem so certain and ‘all or nothing’, can also be examined for their accuracy and helpfulness. Although depression tends to push us towards certain types of extreme judgements, it is helpful to think that these are only parts of ourselves. Like a piano, we can have and play different notes and can play them in different combinations. We are far more complex than our depression would have us believe. Consider the typical kinds of labels you put on yourself and then reflect on the following:

As a human being, I am a complex person. I am the product of many millions of years of evolution, with an immensely complex genetic code and billions of brain cells in my head. I am also the product of many years of development, with a personal history. One of the things evolution has given to all of us is the ability to operate in many different states of mind and in different roles. Therefore to judge my whole self, my being and my essence, in a single negative term is taking all-or-nothing thinking to extremes.

When I am depressed, it is natural and understandable that I tend to feel bad and inadequate, but this does not make me bad or inadequate. To believe it does would be a form of emotional reasoning. I might feel worthless (that is what depression does to feelings) but this does not make it true. These are the thoughts linked to my fears and anxieties and frustrations but they are not truths.

Although I tend to focus on negative labels when I am depressed, I can try to balance these out with other ideas about myself. For example, I can reflect that I am honest, hard-working and caring – at least sometimes. I can consider alternative labels and inner experiences. When depressed it is easy to focus on the negatives, because that’s what depression does. The trick is to refocus my attention on the things that I appreciate about myself, even if they are difficult to see at times. The act of practising helps me take control of my mind rather than letting depression determine what I think and feel.

How do I see myself when I’m not depressed? Okay, maybe not as good a person as I might like, but certainly not as I do now.

Although depression likes simplistic answers to complex problems and tends to see things in black and white, good and bad, I don’t have to accept this view but can try considering the alternatives.

The essence of me is really my conscious self. Conscious ness is like a spotlight that can shine on many things. It can cast shadows, the light is not the things it lights up – just like me! (See page 121.)

So our labels reflect inner feelings and the way others have labelled us, but we must be careful not to think that the feeling captures the self. The feeling is not yourself – it is (just) a feeling in your consciousness (about yourself) that you are having in this moment. Let’s look at some typical examples that operate in depression.

The empty self

Some depressed people can see themselves as empty. Depression tends to knock out many of our positive emotions, and it is not uncommon to find that people lose feelings of affection for those around them. Hence they feel emotionally dead, drained and exhausted. As one patient told me, ‘I am just an empty shell’. This is an example of allowing our feelings to dictate our thoughts. The feeling of being empty and alone is not the same as actually being an empty shell.

When dealing with these distressing feelings it can be helpful to recognize that they can be a natural symptom of depression. Depression can knock out our capacity to feel. Thus, it is not you, as a person, who cannot feel; rather, you are in a mental state of not feeling. As soon as your mood lifts, you will feel again. Try not to attack yourself for your loss of feelings, even though it can be desperately sad and disappointing (see page 411). Indeed, if you focus on the sadness of it, rather than the badness, you might find that you want to cry, and crying might be the first glimmerings of a return of feelings. If this happens, put time aside to allow yourself to cry, check out if you have fears of crying and think about what they are. Think about how you may address those fears. Consider how in the past you have coped with these feelings, and you may have more courage than you are acknowledging.

Sometimes the experience of emptiness is linked not to negative things about the person but to the absence of positive things. Paula explained this feeling to me: ‘I’ve never felt bad about myself really. I think I’m not a bad person on the whole, but I just feel that I’m a ”wallpaper person”.’ She felt neither lovable nor unlovable; she just didn’t feel anything strongly about herself one way or another. She revealed a history of emotional neglect by her parents. They had not been unkind to her in an aggressive way but were simply not interested in her. With no one in her life who she felt valued her, Paula had been left with feelings of emptiness and drifting through life. When she looked at the advantages and disadvantages of this idea of being a ”wallpaper person”, she discovered that, although it gave her a feeling of emptiness, it was also serving a useful purpose: it protected her from taking any risks. She had a motto: ‘nothing ventured, nothing lost’.

This view of the self was also a safety strategy protecting Paula from the fears of going out into the world to try to achieve things and change her sense of herself. Changing things we feel safe and familiar with can be difficult and frightening – even if those things are not good for us.

One way to approach this is not to think of getting rid of anything. We can keep our old beliefs as long as we like, if we feel safe with them, but we can also try to build new ways of thinking and feeling and gradually see if we like those better as they become safe and familiar. Feel free to hang on to your beliefs as long as you feel you need them. Try not to feel that something is going to be taken away from you, leaving you vulnerable. But also allow yourself to outgrow your old beliefs.

Here are some ideas for building new self-experiences:

Compassionately prepare yourself to take risks and learn how to cope with failure, disappointment and possible rejection (see Chapter 22). This will be much easier if you learn the art of being kind to yourself in the face of setbacks. We can start with small steps.

Focus on times when you do have some feelings for things – maybe the music you enjoy, or watching a movie.

Develop your mindful attention (Chapter 7) and note how your mind pulls your thoughts this way and that – so, far from empty.

Consider that emptiness is a form of emotional reasoning, such as ‘I feel empty therefore I am,’ which, of course, does not make it true (see pages 213–215).

Consider that what you are calling emptiness might actually be loneliness or a kind of lostness – unsure what you want to do or where to go in life. If so, be honest about that and gently accept it, but also see it as a specific problem to be worked with.

Engage in your compassionate self work and imagery (see Chapter 8). Sometimes working to help others – making that a life goal – can give us a new sense of purpose.

As we have seen, a key step forward is to act against the feeling or thought that seems to be causing us trouble. Let’s think why you are not empty. Consider your fantasies, dreams, desires and preferences. The pattern of your preferences makes you a unique person. For a start, you probably want to feel different from how you do now. That must mean that you desire to achieve a certain state of mind – not to be depressed any more.

Let’s begin by looking at your preferences. What kinds of films do you prefer and what kinds do you tend to avoid? What kind of music do you like and what leaves you cold? What kind of food do you like and what makes you feel sick? Would you prefer to eat a freshly baked potato or a raw snake or a cockroach? Simple and silly ideas perhaps, but you do have preferences. What kinds of people do you like and feel comfortable with? Which season do you like best? What kinds of clothes do you prefer? If you say that you have no preferences, try wearing a salmon pink top with fluorescent green trousers that don’t fit! The point is not so much that you are empty but that you may, for example, lack confidence to do the things you want, or be feeling very tired, of feel trapped in a lifestyle that is boring. You see, the label does not help you — but working out the actual problem might.

Think about what could happen if you started working on your preferences and developing them. This means not only thinking about your preferences but also acting on them, so it might lead to some anxiety. If so, write down your anxious thoughts and compassionately think how to shift them – see if your fears are exaggerated. How could you take steps to overcome your anxieties?

Suppose you admit that, however mild they might be, you do have preferences, and emptiness is in your feelings not fact. But then you might say, ‘Yes, but I don’t have any qualities that another person might find attractive.’ That’s another issue – that’s not about you, but how you relate to other people. If this is what you think, then your feelings of emptiness may possibly be more related to loneliness. Or perhaps it’s a problem of confidence. Have you shared your preferences with others? If not, what stops you? What would it take for you to turn to someone you know and say, ‘I’d like to do this or that. Would you?’ If you find that you have thoughts of, ‘But they may not want to, or they might think that I was being silly or too demanding,’ the problem is less one of emptiness and more one of confidence. It may be true you have a problem with confidence, and it’s also true that if you do not practise expressing your preferences and desires it can sometimes be difficult to know them yourself. How can you learn what you like and enjoy if you don’t try things out and discover you like this but you don’t like that?

It may also be that you are being unrealistic. Do you want to be attractive to some people, or to everyone you meet? Are you too focused on social comparison (see pages 276–281)? Do you believe that, because your parents didn’t seem that interested in you, nobody will ever be?

Here are some more balanced, helpful ways of thinking about this:

Telling myself I’m empty is a form of emotional reasoning.

I can learn to focus on my preferences and start to share these with others. It may be difficult, so I’ll go one step at a time, but at least I’m on the road to developing.

I may be discounting the positives in my life and saying that some things about myself don’t count. If so, what would they be?

I might be self-labelling here and not appreciating that all human beings are highly complex.

Maybe it is not so much that I am empty but that I am lonely and I have difficulties in reaching out to others.

Maybe it is a problem with confidence. If I felt more confident in expressing myself, would I feel empty?

Am I attacking myself by saying that nobody could be interested in me without giving them much of a chance? If so, how could I give them a chance?

Feeling a nuisance

Nearly all of us humans want the approval of others. This often means that we want to be seen as having things (e.g., talents and abilities) to offer others, and it may be easier to care for others than to be cared for. One problem that can arise is that, when we have needs that can only be met by sharing our difficulties with other people, we feel that we are being a nuisance and may not deserve to be cared for (see Chapter 18). People can be riddled with guilt and shame about needing help. In their early life, their needs may not have been taken seriously. One patient of mine – whose motto was, ‘A problem shared is a problem doubled’– was constantly monitoring the possibility that she was a burden to others. This led to guilt and feeling worse, which, of course, increased her need to be cared for and loved.

The fear of being a nuisance is a common one, but also a sad one. Of course we can feel like a nuisance in a whole variety of ways. Maybe we are physically unwell, are not as competent as others in the group and so on. Sometimes we may have difficulty in being fully open about our needs and asking others for help. Instead, we tend to ‘beat about the bush’ when it comes to our own needs and feelings, and send conflicting messages to others. People’s sex lives can be full of these kinds of worries in approaching one’s partner for a sexual encounter.

Sometimes patients come to therapy but feel awkward, and instead of getting down to the business of trying to sort out what they feel and why they constantly worry about burdening me. They may feel they are not entitled to be in therapy that their problems are not serious enough, that they are ‘making mountains out of molehills’. Rather than allow us to come to a view on this together, they’ve already decided that they’re being a nuisance to me. I explore this fear of being a nuisance quite early on. Sometimes it relates to shame, sometimes to a fear that I won’t be able to cope with their needs because these are too great and complex. At other times it relates to trust: they think that, while I will be nice to them on the surface, secretly I will be thinking that they are time-wasters, that I will deceive them about my true feelings.

Concerns of being a nuisance and being a burden can be upsetting, so it’s useful to consider the following points.

All humans have a need for help from time to time.

Am I labelling and criticizing myself for having these needs rather than facing up to them and understanding what they are?

What does my compassionate/rational mind say about that?

What is the evidence that other people won’t help me or want to share with me if I ask them?

Am I predicting a rejection before it comes?

Am I choosing to ask people for help who I know in advance are not very caring, or would have difficulty understanding my feelings?

Am I saying that all my needs must be met before I can be helped and therefore thinking in all-or-nothing terms?

Are some of my needs more important than others? Can I work on a few specific problems or needs at a time?

Can I break my needs down into smaller ones, rather than feeling overwhelmed by such large ones?

Can I learn to be more assertive and clear about my specific needs? Would that help me?

There is another aspect that can be useful to consider. Sometimes we know that we are in need of healing or help and that we have to reach out to others, but we don’t know what for or what exactly our needs are. That takes some thought, but if you do become clearer on these issues, consider what you will do to help yourself if you do find someone who can meet some of your needs. This is quite an important question. Of course, you might feel happier with some of your needs having been met, but how will this change you? How will you use these met needs for personal growth? When we think about this we sometimes recognize that we are looking for other people to help us develop confidence, or help us feel better. In fact, although others can be very helpful in this regard, these are things we need to work on for ourselves as well.

Sharon was afraid to ask her husband to spend more time with her and to be more affectionate. She thought that this would interfere with his work and that she was simply being a nuisance to him. However, as she explored these needs and considered how she would be different if they were satisfied, she realized that she actually needed his support and approval to boost her own self-confidence. Then she would be more able to go and find a job. By thinking what she would do if some of her needs were met – that is, how this would change her – she recognized two things: first, that there were things she could do for herself to help boost her own confidence (such as not criticizing herself and learning to be more assertive); and second, she recognized that she could be clearer with her husband about the fact that she wanted him to help her gain confidence to go looking for work.

Sharon also realized that seeking more affection from her husband might not be a burden but would actually strengthen the relationship, and this was something she could test. On reflection, she saw that her husband might well benefit from talking more about his feelings and needs, too. She was able to see that her needs could be joint needs. When she spoke to her husband about this, at first he did not really understand. But she stuck to her guns, and later he, too, came to see that he had been so focused on work that he had become lonely himself and felt their relationship was drifting. Not knowing how to address that, he drifted further into work. Moreover, he admitted that he knew that Sharon had felt down but was not sure what to do because she only spoke about her feelings in a general way, not the problems that lay behind her feelings – how she was bored and lonely in the house and she wanted to get out and find a job. To not burden her when she felt down, he had stopped sharing his own problems with her. We can stop sharing for fear of burdening others! Relationships flourish precisely because we share our needs and grow together, not because we hide them.

Fakery

Related to emptiness but different from it is the feeling that one is a fake. From an evolutionary point of view, deception and fakery have been very important behaviors for animals and humans. Quite a lot of animal behavior actually depends on fakery and bluff. Faking and bluffing can be very protective. It is also important to note that children have to learn how to lie. The ability to lie and fake things is actually an important social skill. However, when we become depressed we can feel as if everything we’ve done has been a pretence or a fake, or simply the result of luck. Depressed people begin to devalue their previous or current successes. The reasons for this vary. Sometimes they are perfectionists and think less of things that they feel are not up to standard. They know that there are flaws in their actions or achievements, but become overly focused on them. They think that they were pretending to be more competent. When a professor who held an exalted position in the academic world won a prestigious prize he became depressed, because he felt that he had fooled everyone and that all his writings were of little value. Success did not fit with this self-identity. There was also a fear that he might not maintain his reputation, people would find errors and it would collapse; people would then be very disappointed in him.

When depressed, we may also start to worry about whether the feelings we had for others in the past were genuine, or we were fooling ourselves. However, depression is the worst possible time to start making these kinds of decisions because it reduces the capacity for positive feelings, and we often become less affectionate. In addition, feeling that we are deceiving others can lead to guilt, which we then try to cover up (see Chapter 18).

When Brenda became depressed, she became preoccupied with having fooled Nick into marrying her and that she was now faking love for him. When she came to see me, we had a conversation that, boiled down to its essentials, went something like this:

Paul: When you got married, did you think that you were faking your love for Nick?

Brenda: No, I wouldn’t put it like that. I was, to be honest, more unsure about him and more worried than I let on, but we got on okay and I thought it would work.

Paul: Marriage can be a scary time, so maybe you had mixed feelings and were unsure of what to make of those feelings.

Brenda: Yeah, I guess so. It was a big step to get married and I was worried about whether I was making the right decision.

Paul: Do you think that being understandably worried about making the right decision means that you were being deceptive?

Brenda: I’m not sure.

Paul: Okay, well, let’s put it this way. If you are being deceptive with Nick, is it possible that this is because you are confused in your mind and not sure what you really feel about him?

Brenda: Oh, yes, all my feelings seem confused right now.

Paul: Okay, well, let’s see this problem as one of confusion rather than one of deliberate deception. Right now you may not feel a lot of love for Nick, but we aren’t sure why that is. Maybe there are things you are resentful about, or maybe there are other reasons, but if we work through these, step by step, we might get a clearer picture of what you feel. The problem is, if you just attack yourself for feeling that you are deceiving Nick, then you will feel guilty and find it more difficult to sort out your feelings.

This gradually made sense to Brenda. It turned out that, because she had not been passionately in love with Nick from the start, she felt in her heart that she had deceived him and this made her feel terribly guilty. To overcome her guilt, she would do things in the relationship that she did not want to do (e.g., sex, going out), but she also felt resentful for giving in. She felt rather used by Nick. Slowly Brenda began to see that her main feelings were actually anger and resentment. Once she stopped feeling guilty for having deceived Nick and faking love, she could move on to sort out the genuine problems in the relationship. To do this, she also had to recognize that love is complex and not at all like the movies make out. Brenda discounted the positive in her life by only focusing on her negative feelings and on the times she felt confused about her feelings for Nick rather than on the times she enjoyed being with him. Working on the resentment actually strengthened their relationship.

Sometimes people feel that they have no choice but to fake things. For instance, they may feel that they have to fake love, to hold together a relationship or a family or, as in the following example, a career. Mike faked a liking for his boss who, he thought, could sack him if he did not make a good impression. He came to hate himself for being (as he saw it) weak. However, he could have looked at it differently. He could have said, ‘I understand that I need to hold on to this job and I don’t have that much power to do this other than creating a good impression and getting on with my boss. Actually, I am a very skilled social operator.’ This is not to say that it’s okay to fake – that’s a personal decision. Rather, we need to be honest about it, understand the reasons for it and avoid attacking ourselves for it. If we want to reduce the degree to which we fake things with others, we need to learn how to be more self-confident, compassionate with ourselves and others, and assertive. That will be hard to do if we are attacking and running ourselves down.

The fear of being a fake is not only associated with guilt (as it was for Brenda) but carries the fear of shame (Chapter 17) and being found out. Some people live in constant fear that, because they are living a pretend life, they will be found out, ridiculed and shunned.

Here are some ways to think about dealing with feelings of being a fake:

It may be true that I may have been lucky in some things, but this cannot account for everything I have achieved. I must have some talent, even if it is not as great as I would like.

Sometimes I fake things because I am confused and/or frightened. It would be better to work on this confusion and fear rather than simply attack myself for the fakery and pretence.

Faking or not faking is rarely all-or-nothing. There are degrees of faking and some are actually helpful.

If, since I feel like a fake, I believe I am a fake, this is emotional reasoning. I could be more balanced in my thinking here.

Feeling like a fake is often a symptom of depression. My depression may not be giving me an accurate view of things or myself.

If faking is upsetting me, it would be better for me to understand my reasons for it. I might then be in a better position to change. If I attack myself for faking, I will feel much worse and need to fake more, not less. Let’s be compassionate here and see what lies behind these feelings.