10

Styles of depressive thinking: How to develop helpful styles

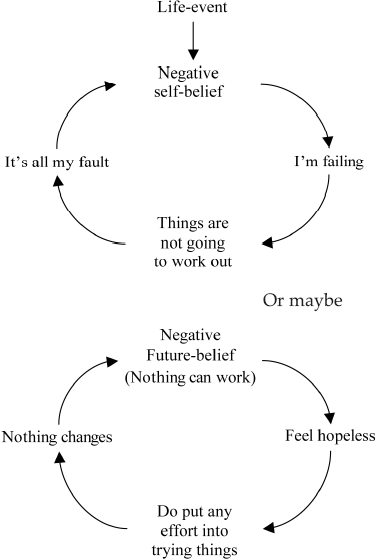

This chapter looks in more detail at the kinds of ways our thoughts can become problematic for us when we get depressed and how to work with them in a compassionate way. Depression can often be linked to difficult life situations: conflicts and problems in relationships, or at work, or with finances, or physical health, or feeling stuck in places we don’t want to be. Coping with these can be hard, but it can become even harder because as we become depressed, the way we think changes. Threat and loss-focused thoughts, interpretations and memories become much easier to bring to mind and dwell on. There is a shift to what is called a threat and loss (negative thinking) bias, and then we are on a downward spiral. 1 A typical spiral is outlined in Figure 10.1.

As our thinking follows a downward spiral, we start to look for evidence that confirms or fits our negative beliefs and feelings. We may start to remember other failures, and the feelings begin to spread out like a dark tide rolling in to cover the sands of our positive abilities. Such thoughts tend to lock in the depression, deepen it and make it more difficult to recover from (see page 101). They drive a vicious circle of feeling, thinking and behavior – and this gives us one route into disrupting the depressing spirals.

Figure 10.1. A typical downward spiral.

Certain styles of depressive thinking are fairly common. Professor Beck, who started cognitive therapy, noted about six or seven types of negative (or as I prefer to called them ‘threat-focused’) thinking biases.2 We will explore some of them here. To work on our biases in a more balanced way, we have to (1) recognize them and (2) make an effort to bring our rational and compassionate minds to the problem. It is important to recognize that humans are often not that logical or rational – we can be, but we have to work at it. In fact a lot of research has shown that many of our ways of thinking about ourselves, other people, different groups, and our hopes for the future can become very biased and inaccurate – even at the best of times!2 So working for balance takes effort and training of our minds. Below we go though some typical biases that tend to appear with depression. We’ll start with jumping to conclusions because this is absolutely typical of the threat-focused and ‘better safe than sorry’ mind.

Jumping to conclusions

If we feel vulnerable to abandonment, or have the basic belief, ‘I can never be happy without a close relationship,’ it is natural that, at times, we may jump to the conclusion that others are about to leave us. This will often impel us to cling on to these relationships, unable to face up to our fear of being abandoned.

The part of our mind that focuses us on threats will tell us that we could not possibly cope with being alone. We might worry about how we think we could cope with everyday life, or we might worry about being overwhelmed by grief, feelings of loss and emptiness. Sometimes these feelings go back to childhood. If you have a fear of rejection or of losing a relationship, one way of helping might be to write down that fear and see if you can think of ways of coping with a break-up – if it occurs. Of course, the break-up may be painful: you can’t protect yourself from life’s painful things, but you can work out how to be supportive and compassionate to yourself in this time of difficulty. It’s hard but it can help us to actually shift our attention and think about how one could cope. For example, be understanding and kind to your distress: it is only natural to feel upset. We might consider how we could elicit help from friends, or remind ourselves that, before we had a relationship with this person, we had coped on our own; or that many people suffer the break-up of relationships and survive. There might even be advantages in learning to live alone for a while.

Putting thoughts into the minds of others

Another form of jumping to conclusions is called ‘mind reading’ or sometimes projection. We make assumptions about their thoughts and feelings. For example, we may automatically assume that people do not like us because they do not give sufficient cues of approval or liking us. In ‘mind reading’ we believe that we can intuitively know what others think.

The key point here is mindfully examining your thoughts rather than automatically assuming that your thoughts about what other people are feeling and thinking are accurate. Research has shown that some people struggle here. For example, parents may believe the annoying behaviors of their children are to wind them up; they take it personally. Or that disobedient children are showing that they don’t care about or respect the parent; again they take it personally. But they are reading intentions into their children that simply are not there. Young children are not thinking about ‘the mind of the parent’ at all. They are not thinking about how to ‘wind the parent up’ or cause them emotional upset – they are simply behaving in these ways to try to get what they want. It’s about them – the child – not the parent.

So the way we attribute intentions and feelings to other people’s behavior is important. When we get depressed we often think other people’s withholding, avoiding or ignoring behaviors are directed at us. Some men think that if their wives do not want to sleep with them when they want to it’s because they don’t love them enough – in reality there may be differences in sex drive, or timing or desire. Women may feel that if men don’t talk about feelings it’s because they don’t love them. In reality the man may have difficulties in talking about feelings in general. When people disappoint us it’s important to think that maybe it’s not really about ‘us’ or ‘me’ it’s about ‘them’. We have to find ways to be compassionately understanding and explore (take time to think about) the ‘minds of others’ in more detail.

Predicting the future

We often need to be able to predict the future, at least to a degree. We need to have some idea about what threats, opportunities and blocks lie ahead to know whether to put effort into things or not. How much energy and effort our brains devote to securing goals depends a great deal on whether we have an optimistic or a pessimistic view of the future. It may be highly disadvantageous to put in a lot of effort when the chances of success appear slim. The problem is that, as we become depressed, the brain veers too much to the conclusion that nothing will work, and continuously signals: ‘times are hard’. Depression says, ‘You can put a lot of effort into this but not get much in return. Close down and wait for better times’ (see Chapter 3). Getting out of depression may involve patience and a preparedness to think that the brain is being overly pessimistic about the future.

Emotional tolerance versus avoidance

Our brains have evolved over many millions of years to be able to have very strong emotions. One of our greatest difficulties is learning how to tolerate and come to terms with strong emotion. We can certainly look to how our thoughts may be making them stronger than they need be, but it’s also important to learn to tolerate the natural and normal power of our emotions; to recognize that there’s nothing wrong with us in having strong emotions. Rather it’s the way we deal with them, either by acting on them impulsively or by trying to get rid of them, avoid them, suppress them, or deny them that causes the difficulties.

A colleague told me a sad story he read in a local newspaper. A woman who was looking for her local Alcoholics Anonymous meeting got lost and couldn’t find the way there. She became upset, frustrated and anxious, so she sat in her car and drank a bottle of wine. She was picked up by the police well over the limit. She had simply not been able to tolerate the upset without wanting to turn off those intense feelings.

Another type of avoidance is the person who feels angry with a parent (say), but is frightened to acknowledge it or work through it. When anger arises she distracts herself or binge eats. Or a person may be frightened of (say) homosexual thoughts and feelings and so drinks to avoid them; or might drink to avoid feelings of loneliness or shame. We can run from all kinds of emotions. Our emotions can also stop us from doing things. Consider a socially anxious person who would love to go to university but the anxiety dictates their actions and they don’t go. Think about how often fears and worries stop you from doing things you really want to do. Sometimes we think about this in terms of confidence, but often it’s about our ability to tolerate emotions and act against that emotion. Most addictions, forms of self-harm, anxiety disorders, reckless and impulsive behavior and some depressions are linked to problems in tolerating emotions.

Given the problems we have with strong emotions and our ‘old brains’, distress tolerance is key to well-being. Compassion can be very helpful in how we learn to work with and tolerate strong emotions. Here are some ideas to have a go at.

Step 1: seeing the point of having a go

Make a commitment to learn to tolerate your emotions as something you want to learn to do.

Recognize the value of doing this; see how it will strengthen you.

Consider the value in giving up the short-term benefit of trying to avoid your emotions (e.g., by avoiding them, drinking or binge eating) in favour of the longer-term benefits of tolerance.

Step 2: what to do next

When you have agreed your motivation then these are some things to try:

Develop an attitude of mindfulness, with two types of focus:

– Sometimes distractions help – focus on something outside of yourself in the ‘here and now’ such as the colour of someone’s clothes, or floor patterns. When I was anxious about giving talks I would try and see a face in the audience that looked friendly and focus on that person, or look just above people’s heads.

– The second form of focusing is to pay attention to how your emotions feel in your body; become curious about them, notice how they come with certain types of thinking and urgencies. You become the observer.

Put your emotions into words as they’re happening: ‘I am beginning to feel frustrated and this is because . . . It is affecting my body by . . . and I am noting a certain urgency . . . There is nothing wrong with me for feeling emotions like this because . . .’ Our brains can give us strong emotions. Research is showing that putting ‘emotions into words’ helps to slow us down and stimulates certain areas of our brain that can help us.

As you notice emotions arising, focus on your soothing breathing rhythm.

Make a commitment not to act on your emotions immediately. Pull back and observe them as best you are able.

Remind yourself there is nothing wrong with you for feeling strong emotion (look out for self-criticism).

If you find yourself thinking, ‘This is unbearable, intolerable, impossible’ and so on, acknowledge these thoughts as notions and judgements that reflect a certain fear in you. However, remember you have made a commitment to try to hold the line – at least for a while.

Keep in mind that these emotions will settle down in time: ‘this too will pass’.

Perhaps you might remember previous occasions when this has happened, so stay with your breathing and focus on ‘This will pass. By tolerating this I am becoming stronger and stronger.’

If you can give yourself some time where you tolerate your emotion, even if it’s only a few moments, you are beginning to learn how to do it.

Be aware of any threat-focused thoughts such as ‘I will lose control,’ ‘this emotion will harm me’, ‘I’m a bad person for feeling this emotion.’ Think through alternatives: ‘I have had these emotions before and have not lost control or been harmed; these feelings are common throughout the world so it can’t be me who is bad. Even if I can only tolerate the emotion briefly it’s a start.’

Learn to acknowledge, value and praise your courage.

Step 3: compassion focusing

With your soothing breathing rhythm, create a com passionate facial expression.

Imagine that you are a compassionate person who can tolerate strong emotion. See an image of yourself tolerating the emotions and being pleased afterwards.

Bring to mind your compassionate image and imagine talking out your emotion to your image.

Write a compassionate letter in your mind about your emotions or what you are feeling this moment.

In these exercises you are practising buying time, being with your emotion, and tolerating it. These are just some ideas and you may find others once you have committed yourself to learning to tolerate strong emotion. It’s not easy, but over time it will get easier for you. Regular practice of mindfulness and compassion work can actually help us become calmer inside. You may also have your own ways of working on this issue. For example although I am not religious myself, I know it can help some people. One woman thought about Jesus: ‘If he can tolerate that, I can tolerate this’. She did not use this to shame herself about her emotion (there are no ‘shoulds’ and ‘oughts’ here), rather it helped her feel ‘one with the suffering of Jesus’ and was very helpful to her. A person who was trying to control her urges to eat when hungry thought about starving children in the world. If they can tolerate that, she could tolerate her urges. It’s not unknown for actors to have severe nausea, even vomiting, on the first night of a play, but they work through it because they really want to act. The first step is really getting clear in your mind the advantage of learning toleration, of putting up with painful feelings.

Emotional reasoning

One of the reasons that we can have problems with emotion tolerance is because our emotions can be more powerful and long-lasting than they need to be. Strong feelings and emotions pull and push us into thinking in certain ways, and this can happen despite the fact that we know it is irrational. The problem is that, at times, we may not get our more rational and compassionate mind to help us. Given the strength of our emotions, we may take the view, ‘I feel it, therefore it must be true.’

Feelings are very unreliable sources of truth. For example, at the times of the Crusades, many Europeans ‘felt’ that God wanted them to kill Muslims – and they did. Throughout the ages, humans have done some terrible things because their feelings dictated it. As a general rule, if you are depressed, don’t trust your feelings – especially if they are highly critical and hostile to you. In Table 10.1 there are some typical ‘I feel it therefore it must be true’ ideas with some alternatives.

In their right place, feelings are enormously valuable, and indeed, they give meaning and vitality to life – we are not computers. But when we use feelings to do the work of our rational minds, we are liable to get into trouble. The strength of our feelings is not a good guide to reality or accuracy. See if you can come up with any other alternatives for the thoughts and ideas in Table 10.1.

TABLE 10.1 FEELINGS, NOT FACTS

|

Situation |

I feel it, therefore it must be true |

Alternative balancing ideas |

|

Going to a party |

I feel frightened, therefore this situation is dangerous and threatening |

This is related to my shyness and confidence, not any actual danger – I can go a step at a time and be kind with my feelings. |

|

Feeling anxious |

I feel as if I will have a heart attack, therefore I will |

This is understandable anxiety which can feel like this – but I have had these feelings many times before and it was anxiety not a heart attack. |

|

Being accused of a minor fault |

I feel guilty, therefore I am guilty and a bad person |

It is understandable to be disappointed but there is so much more to me than that – feeling a bad person is maybe a reflection of my annoyance at being criticized. Learning to cope with criticism will strengthen me. |

|

Losing my temper and shouting |

I feel terrible when I get angry, therefore anger is terrible and I am bad and rejectable |

Yep anger is not a nice feeling but it’s very much part of human nature – I did not design these feelings – and I am trying to understand and work with my anger. |

|

Wanting to cry |

I feel that, if I start crying, the flood gates will open and I will never stop; therefore I must stop myself from crying |

It is easy to feel overwhelmed especially if one is not used to crying and being in touch with one’s pain – but crying does subside and I have shown myself to be effective in turning off my emotions if I really need to. Maybe a little at a time, and staying with my emotions might actually help me. |

|

Feeling self-conscious when I cry |

I feel ashamed when I cry, therefore crying is shameful and a sign of weakness |

Crying is a very important human response built into our bodies. Crying is the display of our pain and is basic to our humanity. Other people have probably shamed me for crying so it is their shame I am feeling. |

|

Making a mistake |

I feel stupid, therefore I am stupid |

Who hasn’t felt that awkward when one does something a bit thoughtless careless and daft – but one cannot sum up a complex self like this. My annoyance is probably driving this feeling and my compassion can actually get stronger if I used it right at these moments. |

Over 2,500 years ago the Buddha said, ‘Our cravings are the source of our unhappiness.’ He also suggested that it is our attachment to things, our ‘must haves’ and ‘must bes’ and ‘others must be as I want them to be’ feelings and beliefs that lead to suffering – not least because life is not like this. All things are transitory and it is coming to terms with that and living in ‘this moment’ that matters. Look out for feelings that indicate you are ‘must-ing’ yourself. As we become depressed, and sometimes before, we can believe that we must do certain things or must live in a certain way or must have certain things, e.g., others’ approval, or achieve certain standards, e.g., weight loss.

By gaining control over our musts, ‘got to haves’ and cravings, we are gaining control over our emotional minds. Whatever your own particular ‘musts’, try to identify them and turn them into preferences. Recognize that reducing the strength of your cravings can set you free, or at least freer, and remember that there is often an irony in our ‘musts’. For example, at times we can be so needing of success and so fearful of failure that we may withdraw and not try at all. If you go to a party and feel that ‘everyone must like you,’ the chances are that you’ll be so anxious that you won’t enjoy it and even may not go. And if you do go, you may be so defensive that others won’t have a chance to get to know you.

Disbelieving and discounting the positive in personal efforts

If we have been threatened or experienced a major setback, we may need a lot of reassurance before trying again. This makes good evolutionary sense: it is adaptive to be wary and cautious. We even have a saying for it: ‘once bitten, twice shy.’

The problem is that in depression this same process can apply in an unhelpful way. If we have experienced a failure or setback, we may think we need to have a major success before we can re assure ourselves that we are back on track. Small successes may not be enough to convince us. However, getting out of depression often depends on small steps, not giant leaps. Typical automatic thoughts that can undermine this step-by-step approach are:

I used to do so much more when I was not depressed. Managing to do this one small thing today seems so insignificant.

Other people could take things like this in their stride.

Because it is such an effort for me, this proves that I am not making any headway.

Anyone could do that.

Small steps are all right for some people, but I want giant leaps and nothing else will do.

Remember what we have said about depression – your brain is working differently. Perhaps the levels of some of your brain chemicals have got a little too low. Perhaps you are exhausted. Therefore, you have to compare like with like. Other people may accomplish more – and so might you if you were not depressed – but you are. Given the way your brain is and the effort you have to make, you are really doing a lot if you achieve one small step. Think about it this way. If you had broken your leg and were learning to walk again, being able to go a few paces might be real progress. Depressed people often wish that they could show their injuries to others, but unfortunately that is not possible. But this does not mean that there is nothing physically different in your brain and body when you are depressed than when you are not.

If you can do things when you find them difficult to do, surely that is worth even more praise than being able to do them when they are easy to accomplish. We can learn to praise and appreciate our efforts, rather than the results.

A crucial thing to remember is that you are training and stimulating your brain. By focusing on small things that you can appreciate and give yourself praise for, you will stimulate important positive emotion areas of the brain. Although understandable, it is not helpful to keep dismissing these opportunities to stimulate your brain in a positive way. Try not to get caught up in debates with yourself about whether you deserve it, whether you should do more and so on. Focus on it as ‘physiotherapy for your brain’; exercising and stimulating key systems in your brain over and over again as often as you can.

Disbelieving the positive from others

Another area where we disbelieve the positive is when others are approving of us. To quote Groucho Marx, ‘I don’t want to belong to any club that will accept me as a member.’ Even being accepted is turned into a negative. Here are some other examples:

When Steve was paid a compliment at work by his boss, he thought, ‘He’s just saying that to get me to work harder. He’s not satisfied with me.’

When Ella was asked how she had been feeling when she returned to work after being ill, she concluded, ‘They’re just asking what’s expected. They don’t really care, but I guess they’ll feel better if they ask.’

When Peter passed a nice comment on how Maureen looked, she thought, ‘He’s just saying that to cheer me up. Maybe he wants sex’.

Paul sent in a report at work, even though he knew there were one or two areas where it was weak. When he got approving feedback, he thought, ‘Deceived them again. They obviously didn’t read it very carefully. No one takes much notice of my work.’

Rather than allowing himself to keep on thinking so negatively, Paul was encouraged to ask his boss about his report, especially the shaky areas. He didn’t get the response he expected. His boss said, ‘Yes, we knew those areas were unclear in your report, but then the whole area is unclear. In any case, some of the other things you said gave us some new ideas on how to approach the project.’ So Paul got some evidence about the report rather than continuing to rely on his own feelings about it.

From an evolutionary point of view, the part of us that is on the look-out for deceptions can become overactive, and we become very sensitive to the possibility of being deceived. Moreover, fear of deception works both ways. On the one hand, we can think that others are deceiving us with their supportive words and on the other, we can think that, if we do get praise, we have deceived them. Because deceptions are really threats, when we become depressed we can become very sensitive to them. But again we can try and generate balanced alternatives to these ideas. For example:

Even if people are mildly deceptive, does this matter? What harm can they do? I don’t have to insist that people are always completely straight. And life being life, some people are more deceptive than others. But I can live with that. To be honest I can be deceptive too – it is part of being human.

As a rule of thumb, it can be useful to take people at face value unless experience proves otherwise.

All-or-nothing

All-or-nothing thinking (sometimes also called either/or, polarized or black-and-white thinking) is typical when we are threatened. If we might be under a threat we often need to weigh this up quickly. Animals often need to jump to conclusions (e.g., whether to run from a sound in the bushes), and it is easier to jump to conclusions if the choices are clear – all-or-nothing. So our threat system can go for ‘better assume the worst’ and ‘better safe than sorry’. See if you can spot these in the list below.

My efforts are either a success or they are an abject failure.

I am/other people are either all good or all bad.

There is right and there is wrong, and nothing in between.

If I’m not perfect, I’m a failure.

You’re either a real man or you’re a wimp.

If you’re not with us, you’re against us.

If it doesn’t go exactly as I planned or hoped, it is a fiasco.

If you don’t always show me that you love me, you don’t love me at all.

All-or-nothing thinking is common for two reasons. First, we feel threatened by uncertainty. Indeed, some people can feel very threatened by this. They have to know for sure what is right and how to act and they may try to create the certainty they need by all-or-nothing thinking. Sometimes we may think that people who ‘know their own minds’ and can be clear on key issues are strong, and we admire them and try to be like them, but watch out. Hitler knew his own mind and was a very good example of an all-or-nothing thinker. Some apparently strong people may actually be quite rigid. Indeed, I have found that some depressed people admire those they see as strong individuals, but when you really explore this with them, they discover that the people they are admiring and trying to be like are neither strong nor compassionate. They are rather shallow, rigid, all-or-nothing thinkers who are always ready to give their opinions. A lovely motto someone gave me once was ‘indecision is the key to flexibility’.

There is nothing wrong with sitting on the fence for a while or seeing things as grey areas. Even though we may eventually have to come off the fence, at least we have given ourselves space to weigh up the evidence and let our rational minds do some work.

The other common reason why we go in for all-or-nothing thinking has to do with frustration and disappointment (see Chapter 21). How often have we thrown down our tools because we can’t get something to go right? When you get frustrated you tend to take a more extreme view. It is emotions that drive this view, so balancing of all-or-nothing thinking and our tendency to make extreme judgements of good/bad or success/failure can be very important in recovering from depression. The state of depression itself can reduce our tolerance of frustration and push us into all-or-nothing thinking, so we have to be aware of this and be careful not to let it get the better of us.

All-or-nothing thinking can be unpleasant for other people too. Tim talked about his mother who was depressed and how she found frustration very difficult. ‘Small things would set her off and then you would never know what mood she would be in.’ Tim could identify this as black-and-white and rigid thinking. ‘Things had to be just so and if they weren’t she’d get angry, anxious or withdraw.’ Tim understood that this related to various stresses in her life. Nonetheless, seeing this allowed Tim to reflect on himself and he decided he didn’t want to be like that. When he felt frustration mounting in him he would begin his soothing rhythm breathing, consider if his thoughts and feelings were rather black-and-white and practise being compassionate and tolerant in that context.

Overgeneralization

If one thing goes wrong, we can think and feel that everything is going to go wrong – our emotions go on a rollercoaster. When we overgeneralize like this, we see one setback or defeat as a never-ending pattern of defeats. Nothing will work; it will always be this way.

a student received a bad mark and had a heart-sink disappointment feeling and concluded, ‘I will never make it. My work is never good enough.’ (linked to anger, frustration and anxiety)

a friend had told Sue that she would come to her party, but then she forgot the date. Sue thought, ‘This is typical of how people always treat me. No one ever cares.’ (linked to anger, frustration and anxiety)

Dan broke up with his girlfriend and thought, ‘I will never be as happy again as I was with her. I will always be miserable without her.’ (linked to sadness)

So it’s important to be aware of the arising of feelings and meanings and the thoughts that tumble along with them.

In Table 10.2 we can explore some typical balanced and compassionate alternatives for working on our tendencies for overgeneralization. Notice that we always start with being understanding and kind for the distress we feel.

TABLE 10.2 ALTERNATIVES TO DEPRESSING THOUGHTS

|

Depressing thought |

Balanced and compassionate alternatives |

|

Things will never work out for me |

When I am upset it is typical for me to think like this – so I can be wise and kind to myself by recognizing it is my upset that is doing the thinking |

|

|

‘Never’ and ‘always’ are big words. I have thought like this before and things did work out – at least to a degree |

|

|

Let’s take some soothing rhythm breaths and slow myself down a bit and give myself some space to think |

|

|

Now what would I like a really kind and compassionate person to say to me right now (really spend a moment on this idea and go with that) |

|

|

Rather than just blanking out everything I could think that things might go okay |

|

|

Predicting the future is a chancy business. Maybe I can learn how to make things go better. I don’t have to load the dice against myself |

|

|

If a friend had a setback, I would not speak to them like this. Maybe I can learn to speak to myself as I might to a friend. |

Egocentric thinking

In this situation, we have difficulty in believing that others have a different point of view from our own. The way we see things must be the way they see things – e.g., ‘I think I’m a failure, thus so must they.’ We discussed this on page 207, in the section ‘Putting thoughts into the minds of others’.

But there is another way we can be egocentric in our thinking. This is when we insist that others obey the same rules for living and have the same values as we do. Janet was very keen on birthdays and always remembered them. But her husband Eddie did not think in these terms; he liked to give small presents as surprises, out of the blue. One year, he forgot to buy a present for Janet’s birthday. She thought, ‘He knows how important birthdays are to me. I would never have forgotten his, so how could he forget mine? If he loved me, he would not have forgotten.’ But the fact was Eddie did not really know how important birthdays were to Janet because she had never told him. He was simply supposed to think the same way as Janet.

In therapy together with Janet, Eddie was surprised at how upset she had been and pointed out that he often brought her small surprise presents, which showed that he was thinking about her. He also mentioned to her – for the first time – that she rarely gave gifts except at birthdays, and to his way of thinking, this meant that she only thought about giving him something or surprising him once a year!

All of us have different life experiences and personalities, and our views and values differ, too. These differences can be a source of growth or conflict. It is because we are all different that there is such a rich and varied range of human beings. Unfortunately, at times we may downgrade people if they don’t think or behave like us. On the book stands today, you will find many books that address the fact that men and women tend to think differently about relationships and want different things out of them. This need not be a problem if we are upfront about our needs and wants and negotiate openly with our partners. It becomes a problem when we are not clear with them about our wants or we try to force other people to think as we do.

Dwelling and ruminating

As we noted on pages 113–4, dwelling and ruminating on the threats and losses in our lives can be a source of maintaining your brain in a state of threat and stress. All the ways of thinking noted above can feed into ‘dwelling and ruminating’. Some people also think that this is a way to solve problems and, if limited, thinking things through can of course be helpful. However, going over and over things that upset you or make you angry or anxious is not helpful. The steps are:

Practice noticing your ruminations when they start up.

Become mindful and notice the paths your thoughts tread – pull back to your observing kind and curious mode.

Make a commitment to gently refocus your attention – maybe with an activity or bring to mind a helpful image or something that is more likely to stimulate positive feelings in your brain.

KEY POINTS

The way we think about things can lead us further into depression rather than out of it.

When we are depressed, our brains change in such a way that we become very sensitive to various kinds of harm, threats and losses. It is (or was) adaptive for the brain to go for an ‘assume the worst’ and ‘better safe than sorry’ type of thinking when under threat. In these situations, control over our feelings is given more to the threat system in our brain and less control is given to the rational, kind and compassionate systems (see Chapters 2 and 3).

There are some typical types of thoughts that are encountered in depression. These include jumping to (negative) conclusions, emotional intolerance, ‘I must’, dismissing the positives, all-or-nothing thinking and overgeneralizing. We can try to work with these.

One way to help is to recognize the typical styles of depressive thinking and open our hearts to generating compassionate balanced alternatives; to deliberately switch our attention, thinking and behaving away from the threat system into a more balanced and compassionate system.

Exercise 1

Review the different types of thinking outlined in this chapter. Consider which ones seem to apply to you (see Appendix 2 for a quick overview of some typical types of threat-focused thinking).

If you have written down your thoughts, consider which kind of depressive style each thought may be an example of – for instance, is it like jumping to conclusions, or emotional reasoning, or all-or-nothing thinking? You may find that one of the styles (e.g., all-or-nothing thinking) crops up in many different situations. That is certainly one of my styles when under stress.

Use your rational/compassionate mind to generate alternatives; think of questions to put to yourself. Do you have enough evidence for your view? Is this a balanced view? Would you put it to a friend like this? If you are to be really kind now, what would you think? Are you trying to force a certainty when none exists? Are you disbelieving the positives? Are you frightened of believing in the more balanced and compassionate alternatives?

Consider how you might help someone you like generate alternatives to, say, all-or-nothing thinking or jumping to conclusions. Practise being gentle with yourself rather than harsh and critical, and practise seeing things in grey rather than insisting on black and white.

Work on emotional balance and feeling tolerance as noted above.

Focus on what you can do rather than what you can’t. Have the motto, The secret of success is the ability to fail.’ (See Chapter 21 for further discussion of this motto.)

Ask, ‘How am I looking after myself? Do my thoughts help me care for myself?’ Slowly build on your insights.

Always have a go at spending a few moments on your breathing and then trying to shift to the compassionate self or bring to mind your compassionate image (see Chapter 8). Once in that frame (even if only slightly) it might be easier to generate and think about compassionate alternatives.

It can also help to be mindful of your thoughts – note them in your mind and stand back from them – view them from the balcony as it were – watch the mind shift to black-and-white thinking or over-generalizing. It can seem odd and difficult at first, but with practice it can be very interesting. There is no forcing or trying to make yourself change your mind – just be open to the possibility for change and see what happens.

11

Writing things down: How to do it and why it can be helpful

Learning to write about your thoughts and feelings, especially to begin with, can be helpful. Here are some of the reasons why.

Writing down is slowing down. The first reason is that writing slows our thinking down and helps us to focus. It helps to stop those half-formed but emotionally powerful thoughts whizzing around out of control.

Attention. Writing things down helps concentrate our attention and enables us to stand back a little. Seeing the words coming on to the page helps us to distance ourselves from the thoughts, as we have to focus on the process of writing.

Catching thoughts. By slowing down and focusing we may discover all kinds of thoughts ‘lurking in the background’. One way of catching our thoughts, and inner meanings we put on things and feelings, is by being gently curious and asking ourselves some questions such as those I outlined on pages 107–108 Also, having felt something, you stop and say, ‘How can I account for what I feel? What am I thinking?’ This can help to pinpoint and identify our thoughts. The more you slow your thinking down, especially by writing, the more likely you are to ‘catch’ the key thoughts and meanings that are associated with what you are feeling.

Clarity. Writing down is an excellent means of gaining clarity. When you have written your thoughts down, you have a record of them in front of you; something you can look over calmly to see how your thoughts may be understandable given your depression and life difficulties, but not helpful to you – and if you dwell on them they will make you feel worse.

Gaining a perspective. Seeing your thoughts written out in front of you may well help you see that your depression is pushing you to be overly negative (loss-and threat-focused) and losing perspective. This is much more difficult to see if you just work with your thoughts in your head, because it is hard to gain the distance that is achieved by writing them down.

Thought forms

Thoughts forms offer ways of helping us to organize our thoughts and to distinguish between situations that trigger our feelings and moods, the kinds of thoughts and feelings that pour through our minds (often in a chaotic way), and then how we can refocus our attention on generating helpful alternatives. Thought forms are just useful guides to help our practice and develop our minds: see Appendix 1 for some ideas.

My advice here is: keep it simple. Use whatever kind of form suits you, rather than struggling with something that you find too complex – provided it does the job, of course. The most basic thought-alternative form is simply a page divided into two columns. You write your unhelpful, threat-focused thoughts in the left-hand column, and helpful, compassionate alternatives in the right-hand column. These depressive thoughts might be triggered by an event, or might come on as your mood dips. The key point is catching what these thoughts are and offering a balanced and compassionate alternative to them.

Table 11.1 shows an example of a completed form.

TABLE 11.1 COMPLETED THOUGHTS FORM

|

Depressing thoughts |

Balanced alternative thoughts |

|

Here I am just lying in bed again |

I have to admit I am not feeling too good right now |

|

Can’t see the point of getting up |

Even though it will be a struggle, if I can try to gently encourage myself to get up and move around a bit this often helps |

|

Things are bound to go wrong |

If I can achieve a couple of things I’ll feel better |

|

Nothing is worth doing anyway – I won’t enjoy it |

Sure, I don’t enjoy things much because I am depressed – the trick is doing things to overcome depression. I know I can enjoy things when I am not depressed. So I will do my best to work against my depressed brain state |

|

Degree of belief: 70% |

Degree of belief: 40% |

Rate your belief

You will see that at the bottom of each column in this example there is a figure for ‘degree of belief’ – that is, how much do you believe what you have written down? Some people find that if they rate how much they believe something this can be helpful for seeing that beliefs are not black and white, all-or-nothing. As time passes and you start to feel better you’ll be able to look back and see how the strength of your beliefs has changed with your recovery. Other people don’t find this particularly helpful, because they feel it is artificial in some way. Once again, find what works for you.

Make up your own column headings

You can make up your own column headings for different tasks. For example, sometimes it can be useful to write down in two columns (1) the reason why you believe and then (2) in the other column the reasons to change that view, or consider the advantages and disadvantages of a particular belief. You might prefer to label the two columns ‘what my threat- or loss-focused and/or self-attacking mind says’ and ‘what my rational and compassionate mind says’. For all these variations you can use the two-column format and simply change the headings to suit.

Adding more columns

In the thought forms given in Appendix 1 you will see other columns. In addition to the two noted above, we also have a column for writing down any critical events that might have triggered your distressing thoughts and a column for describing distressing feelings. This helps to give you a more complete picture; it will help your progress if you can be clear on what kinds of things tend to trigger your change of mood, arouse negative thoughts and feelings, or what those emotions and feelings actually are.

Rate change

It can sometimes be useful to rate the change in the strength of your beliefs and in your emotions after you have been through the exercise. For that, we might add a third column to the simple two-column form. Table 11.2 shows the same examples we used above, with the third column added on.

|

Depressing thoughts |

Helpful thoughts that operate against the depression |

How I feel now compared to before |

|

Here I am just lying in bed again |

I have to admit I am not feeling too good right now. Even though it will be a struggle, if I can gently encourage myself to get and move around a bit this often helps . . . (etc.) |

Yes, I can see that this might be helpful and a way forward |

|

Can’t see the point of getting up |

Even though it will be a struggle, if I can try to gently encourage myself to get up and move around a bit this often helps. |

|

|

Things are bound to go wrong |

If I can achieve a couple of things I’ll feel better |

|

|

Nothing is worth doing anyway – I won’t enjoy it |

Sure, I don’t enjoy things much because I am depressed – the trick is doing things to overcome depression. I know I can enjoy things when I am not depressed. So I will do my best to work against my depressed brain state |

I feel maybe 5% less depressed by compassionately refocusing my thoughts |

Try as best you can, with an encouraging, supportive (not bullying) tone in your mind to carry out your plan to get up and out of bed, move about and do something active, no matter how small. You might rate how you feel having done this, compared to how you were feeling before you started. Note the difference. You could even compare how you feel now with how you might feel if you had not done anything at all but stayed in bed. The point here is that the more you yourself see the value in these kinds of exercises the more you are likely to have a go.

Adapting the basic idea to suit yourself

Once you have got the basic idea of the importance of writing things down and slowing your thinking down, you are prepared to start working on your thoughts, feelings, and moods. However, the exact framework you choose to do this should be something you decide for yourself: it’s important that you are happy with the form you use.

Different forms will be useful for working on different things. I have started us off here with a fairly basic thought-recording form; but please tailor it to suit you. Experiment with these forms and try out designs of your own. However, always keep in mind the basic point of all this: that is, to help you stop hitting your brain with lots of negatives, to get a better perspective on things and start giving your brain a boost and some warmth.

Compassionate reframing

Ideas for generating alternatives are given in Chapters 9–11 and throughout this book. In Appendix 1 there are also various worked-out examples to offer you some more ideas – but these are only ideas. Sometimes it is helpful to take a few soothing rhythm breaths and focus on your compassionate self or image. You are trying to shift the position in your mind to where your thinking comes from – stepping into the compassionate frame of mind, as it were – and then from that position (or mind) starting to think about alternatives. You can also imagine compassionately trying to help someone, such as a friend you care for, to think in a different, more balanced way. How might you focus on strengths and courage, on coping and getting through? What would your voice tone be like? The key is to shift position. You will be very familiar with what your threat, loss and critical mind says, because that part of you will be active a lot of the time, but can you tune in to your compassionate mind, attend to it and develop it? Writing things down can give you the space and distance to start to do this.

There is now increasing evidence that writing about our feelings, expressing and exploring our feelings in writing (so-called expressive writing)1 can be very helpful for some people. Indeed, we can put into words on paper things we might struggle to think about in our heads or express to other people. We will explore some types of writing here so that you can see which one helps you.

Writing about oneself

Choose what you want to write about: your life in general, or a particularly difficult time in your life that you had trouble coming to terms with, or problems that you are experiencing right now. The idea here is to express your thoughts and feelings on paper, writing about what has happened or is happening to you. Imagine that you’re writing to a very compassionate person who completely understands what you feel.

Sometimes writing like this may stimulate different feelings in us. Again the key here is to go step by step and explore what is helpful to you. If you feel that there are things that you really don’t want to face on your own, be honest about that and think about whether you want to obtain professional help to guide and support you, or talk to a friend. Remember all these exercises are intended to be helps and guides for you, and you’ll need to judge just how helpful they are for you.

Another approach to writing is to begin to think about yourself and your feelings from different perspectives. Because we use different aspects of our minds when we write, we can sometimes find that in the process of writing, new insights and meanings emerge in our minds that help us clarify things. Practising doing this can help you access aspects of yourself that may help you understand your feelings better, learn how to tolerate them without fear or worry of acting them out, and perhaps tone down more depression-focused feelings and thoughts. But keep in mind what I have said many times before – this is an invitation, a ‘try it and see’.

Writing about yourself from another’s point of view

Sometimes it is useful to try shifting perspective on how we see ourselves. One way of doing this is to write a short letter about yourself, from the point of view of someone close to you who cares about you. I’m going to use the example of a fictitious person we will call Sue, but when you write your letter substitute your own name, of course. Such a letter might include:

I have known Sue for about twenty years. To me, he/she has been

I find Sue

I think Sue struggles with

I like Sue because

Sue’s strengths are

It would help Sue if she could

This exercise is designed to help you develop the habit of considering other perspectives on yourself. If you like, show what you have written to someone you are close to and trust, and see what they think.

Some people find this very helpful, others do not. One person noted that ‘I actually don’t know anybody that well who would be able to write in detail about me.’ So here you might want to imagine a friend, and what you would like them to say about you. If you find it is too easy to dismiss positives then you might want to try practising some of the imagery exercises we talked about in Chapter 8, or the behavioral work in Chapter 12.

Writing compassionately to yourself

In this exercise we are going to write about difficulties, but from the perspective of the compassionate part of ourselves. There are different ways you can write this letter. One way is to get your pen and paper and then spend a moment engaged with your soothing breathing rhythm. Feel your compassionate self. As you focus on it, feel yourself expanding slightly and feel stronger. Imagine you are a compassionate person who is wise, kind, warm and understanding. Consider your general manner, voice tone and the feelings that come with your ‘caring compassionate self’. Adopt a kindly facial expression. Feel the kindness in your face before moving on. Think about the qualities you would like your compassionate self to have. Spend time feeling and gently exploring what they are like when you focus on them. Remember it does not matter if you actually feel you are like this – but focus on the ideal you would like to be. Spend at least one minute – longer if possible – thinking about this and trying to feel in contact with those parts of yourself. Don’t worry if this is difficult, just do the best you can – have a go.

When we are in a compassionate frame of mind (even slightly), or in the frame of trying to help a friend or someone we care for, we try to use our personal experiences of life wisely. We know that life can be hard; we offer our strength and support; we try to be warm and not judgemental or condemning. Take a few breaths then sense that wise, understanding, compassionate part of you arise. This is the part of you that will write the letter. So we write this kind of letter from a compassionate point of view. If thoughts of ‘Am I doing it right?’ or ‘I can’t get much feeling here’ arise, note or observe these thoughts as normal comments our minds like to make, but refocus your attention and simply observe what happens as you write, as best you can. There is no right or wrong, only the effort of trying – it is the practice that helps. As you write, create as much emotional warmth and understanding as you can. You are practising writing these letters from your compassionate mind.

As you write your letter, allow yourself to understand and accept your distress. For example, your letter might start with

I am sad. I feel distressed; my distress is understandable because . . .

Note the reasons, realizing your distress makes sense. Then perhaps you could continue with

I would like me to know that . . .

For example, your letter might point out that as we become depressed, our depression or a distress state can come with a powerful set of thoughts and feelings – so how you see things right now may be the depression view on things. Given this, we can try and step to the side of the distress and write and focus on how best to cope. We can write

It might be helpful to consider . . .

A second way of doing this is to imagine your compassionate image writing to you, and imagining a dialogue with them and what they will say to you. For example, my compassionate image might say something like

Gosh, the last few days have been tough. Isn’t it typical of life that problems arrive in groups rather than individually. It’s understandable why you’re feeling a bit down because . . . Hang in there because you are good at seeing these as the ups and downs of life, and that all things change, and you often say at least we are not in Iraq. So you have developed abilities for getting through this and tolerating the painful things.

You will note that the letter points to my strengths and my abilities. It doesn’t issue instructions such as, ‘You must see these things as the ups and downs of life.’ This is important in compassionate writing. You don’t want your compassionate letters to seem as if they are written by some smart bod who is giving you lots of advice. There has to be a real appreciation for your suffering, a real appreciation for your struggle and a real appreciation for your efforts at getting through. The compassion is a kind of arm round your shoulders, as well as refocusing your attention on what is helpful for you.

AN EXAMPLE

Here’s a letter from someone we’ll call Sally, about lying in bed feeling depressed. Before looking at this letter, let’s note an important point. In this letter we are going to refer to ‘you’ rather than ‘I’. Some people like to write their letters like that, as if writing to someone else. See what works for you but, over time, use ‘I’. You could read this letter and substitute ‘I’ for ‘you’.

Good morning Sally

Last few days have been tough for you so no wonder you want to hide away in bed. Sometimes we get to the point of shutdown, don’t we, and the thought of taking on things is overwhelming. You know you have been trying real hard, I mean you haven’t put your feet up with a gin and tonic and the daily paper. Understandably you feel exhausted. I guess the thing now is to work out what helps you. You’ve shown a lot of courage in the past in pushing yourself to do things that you find difficult. Lie in bed if you think that it can help you, of course, but watch out for critical Sally who could be critical about this. Also you often feel better if you get up, tough as it is. What about a cup of tea? You often like that first cup of tea. Okay, so let’s get up, move around a bit and get going and then see how we feel. Tough, but let’s try.

So you see the point here: it’s about understanding being helpful, having a really caring focus but at the same time working on what we need to do to help ourselves.

Writing as you at your best

Another way to write these letters is to imagine the part of yourself you like, the self you would like to aspire to more of the time (as long it’s not the aggressive kick myself past of course!). Then try to bring that ‘you’ to mind – recall ‘you at your best’, ‘you as you would like to be’ and then write from that part of you.

Guide to letter writing

When you have written your first few compassionate letters, go through them with an open mind and think whether they actually capture compassion for you. If they do, then see if you can spot the following qualities in your letter.

It is sensitive to your distress and needs.

It is sympathetic and responds emotionally to your distress.

It helps you to face your feelings and become more tolerant of them.

It helps you become more understanding and reflective of your feelings, difficulties and dilemmas.

It is non-judgemental/non-condemning.

A genuine sense of warmth, understanding and caring permeates the whole letter.

It helps you think about the behavior you may need to try, to get better.

Depressed people can struggle with this to begin with, and are not very good at writing compassionate letters. Their letters tend to be rather full of finger-wagging advice. So we have to work and practise being compassionate. The point of these letters is not just to focus on difficult feelings but to help you reflect on your feelings and thoughts, be open with them, and develop a compassionate and balanced way of working with them. The letters should not offer advice or tell you what you should or should not do. It is not the advice you need, but the support to act on it.

Writing to others

Another way we can use letters is to express to ourselves our feelings about people. Usually these letters are not sent. If you feel you want to send them, it’s best to keep them for a week or two and think carefully before you do anything about it.

The purpose of this letter is again to articulate your feelings. You can write about your needs or sadness, disappointment or anger, or how you want to be loved or things you find it difficult to express. The point about writing these things down is that we think in a different way when we write.

Writing can help in ways that allow us to make sense of things and come to terms with them in a different way. For example, Kim felt very angry with her mother who was a career woman. As a child, Kim had been looked after by a number of different nannies. For some years Kim felt under pressure to tell her mother what she felt. She also felt she couldn’t have a genuine relationship with her mother until she cleared the air, and that she was being weak in not speaking honestly. However, we talked about this and the importance of taking the pressure off herself ‘to prove herself’ and confront her mother. She wrote some moving letters that were never sent, and at the end of the process felt that a lot of the pressure to confront her mother had gone. In a strange way this actually made it easier for her to think about having a conversation with her mother about the key issues. Kim came to see that the degree of anger she felt blocked her in many ways, because it was less about anger and more about wanting recognition from her mother that was important. The writing helped with the anger and then Kim was able to think about how to have a quieter conversation about the sadness in Kim’s life because of the effects of her mother’s career.

Grief

Sometimes if we are grieving it can help if we write letters to the dead person, saying goodbye or whatever else we want to say. Goodbye letters can sometimes be quite emotional but also helpful in articulating and expressing our feelings.

As with all these exercises, take one step at a time and only do things that are helpful for you, or that you can see will be helpful if you stick with them. If you feel you grief is overwhelming then this might be a time to think about professional help from a counsellor or psychotherapist. Or simply take very small steps, but do it reasonably often, and build up.

Forgiveness

The last 10 years have seen a lot of research on forgiveness.2 However, there is a lot of misunderstanding about it. Forgiveness is about letting go of our anger. The person we forgive we may never like, never want to see. We might never condone their actions. Forgiveness is simply putting down our weapons and our desire for vengeance, and walking away. We say, ‘It ends here.’ Of course there may be a lot of thoughts such as, ‘I must not let them get away with it,’ ‘It is too unfair’, ‘I am weak if I do not pursue this,’ ‘If I were a proper person I would do something about this.’ The problem is that living with anger often isn’t going anywhere and that is very depressing. The only person we are hurting is ourselves and our brain, because we are constantly stimulating threat systems in our brain. Anger that is unhelpful like this simply makes us feel powerless.

Forgiveness is a way in which you can bring peace to your mind. We could fill a whole book looking at how to work on forgiveness.2 If you go on to the Internet you will be able to explore lots of sites on forgiveness. Check them out and see what works for you; some are interesting and helpful, and some not. But at a straightforward level, forgiveness letters are simply ways to help you acknowledge your anger and upset and forgive, let go, move on, walk away. As one patient told me:

I realized I had spent a lot of my life hating my mother and yet also wanting her to love me. She just wasn’t up to it. When I realized that actually she was quite a damaged person and simply wasn’t up to being as I wanted her to be, I felt more sorry for her and able to forgive her. To be honest I pulled back quite a bit and I think she would like me to have seen her more, but I found a comfortable distance for me. Recognizing this and letting go of my anger and my need set me free. And you know, wherever she is now (she died a few years ago), I genuinely hope she’s happy.

Importantly, keep in mind that the point of these letters is not to stir up difficult emotions but to be compassionate about them and learn how to think about them in compassionate and balanced ways.

Gratitude and appreciation

So far we have rather focused on writing about difficult things. However research has also shown that it’s very helpful if we can spend some time thinking about things we appreciate, like and feel gratitude for.3 When we are depressed it can be quite difficult to have feelings of gratitude. Nonetheless if we focus on those feelings it will stimulate parts of the brain that are associated with positive antidepressant feelings. You can start by thinking of a person or key phase in your life, or someone who is showing you some kindness no matter how small, and think about gratitude. The feeling of gratitude is not a grudging or a belittling feeling at all, but a feeling of pleasure and joy that the other person was there and helped you in some way.

Gratitude is not associated with a feeling of obligation. The moment we feel obligated by somebody else’s kindness it is difficult to feel gratitude. Focus on the behavior. One patient noted that although there were things that angered her about her husband, just focusing on her gratitude for him helped her feel more balanced and happier.

The same goes for appreciation. Take your pen and a fresh sheet of paper, and write about the things you appreciate and like in your life. They might be quite small things like the first cup of tea of the day; the blue of a summer sky; certain tele vision programs; the warmth of your bed; a relationship; or part of your job – absolutely anything that gives you feelings of appreciation and liking. Notice how we often let these pass. Bear in mind why you are doing this as an exercise – it is to balance up your systems and to stimulate part of your brain that will help you counteract the feelings of depression. Recall that depression will force you into a corner of your mind so that you always have to walk on the shadowy side of the street, so we have to practise refocusing.

KEY POINTS

To combat depression, we can call on different parts and abilities of ourselves: our rational minds and our compassionate/friendly minds. Writing helps us slow down and think in different ways.

By calling on these aspects of our minds and trying to activate them, we are making our brains work in certain ways that can counteract depression.

We can learn to write about our difficulties reflectively and with compassion by putting ourselves in the compassionate frame of mind when we write. This can take practice. Using a letter-writing approach can be helpful.

Exercise 1

Write down your depression thoughts about a particular situation. Look at them carefully.

As you think about alternative ideas, take a rational/compassionate approach. Try thinking about what you might say to a friend who is in a similar situation. You might also consider how you think when you are not depressed.

To begin to generate alternative thoughts, look back at the ideas on pages 187 9 and focus on:

What is it helpful to attend to (e.g., from memory or in your current situation). Remember the old saying ‘is the glass half full or half empty?’ – practise attending to the half-full aspects too.

What is a fair, logical or reasonable way to think and reason?

What would be the helpful and supportive things to do in this situation?

Exercise 2

Write some compassionate letters for yourself, or engage in writing that expresses your feelings.

Even if you don’t have much faith in the alternatives you think of at first, the act of trying to generate them is an important first step. As with all exercises it is what you think will be helpful to you that is key, because different people find different things helpful. Make sure that all of your efforts to help yourself meet the ‘friend and compassion test’. This means that any of your alternative thoughts are considerate, helpful behaviors that you would be prepared and pleased to offer to friends and that you can see are evidence of compassion. Logic and common sense is not always useful to us; it’s when we feel it is helpful in our hearts that matters.

12

Changing your behavior: A compassionate approach

As we saw in earlier chapters, the depressed brain state can be a kind of ‘go to the back of the cave and stay there’ state. We want to pull the covers over our head and wish the world would go away. When we feel like this it helps to take a compassionate approach: in other words, to be very understanding of such feelings but also to think what might be triggering this feeling and how to break out of it. Maybe we have been working too hard and are exhausted, or maybe life events, setbacks and conflicts have taken the wind out of our sails. Sometimes a mild depression tells us we are exhausted and we really need to find a way to slow down and get some rest, let our bodies recuperate. Humans are like other animals – we need chill-out time. It is amazing how, when people take longish breaks from work, they often say they feel themselves slowing down, and the pace of life is easier. We must admit to ourselves that, through no fault of our own, we are living in a ‘rush rush, hurry hurry’ society where we can get rather exhausted. Learning to take time out, respect our body and rest it as much as possible is important, and I agree – it is easier said than done. In particular, one of the problems of being a single parent is the sheer workload, and demands that can be exhausting. If burnout and exhaustion are behind the depression, it’s important to see this and to address it in appropriate ways – without blaming oneself for being tired!

However, as we get depressed we can also stop doing various activities and disengage, and this adds to a depression cycle rather than helping it. We find resting is not helpful. When we are depressed, daily activities can seem overwhelming. In these situations it can be very useful to operate against the pull of depression. We need to encourage ourselves to do more not less, but the emphasis is on encouraging not bullying ourselves. This helps us to activate our drive system. It helps if we organize activities in such a way that they can be approached step by step. In the last 10 years or so therapies for depression have been developed which focus specifically on changing behavior.1 There are also self-help books dedicated to this type of ‘change your behavior, change your mood’ approach.2 It’s important, though, that you see this as helping you, not just as putting on a mask and carrying on regardless.

Tasks and goals

When therapists are trained, they are often taught to focus on three things: the bonds and relationships between patient and therapist; the tasks that need to be undertaken; and the goals and aims of the therapy. In helping yourself to get out of depression, you can take the same approach. The bonds and relationship you have with yourself have been the focus of earlier chapters, so now let’s look at tasks and goals.

Tasks

Often, as we move forward out of depression, there are various tasks that we can set for ourselves on our step-by-step journey. Here are some examples:

Write down your thoughts and feelings.

Try tape recording ideas that are good alternatives to your negative thoughts on a tape. When you feel down, play these alternatives to yourself.

Learn to be honest with yourself.

Learn how to take big problems and break them down into smaller ones.

Set yourself small things to do that operate against the depression each day.

Increase the time you spend talking with friends.

Make the phone calls you need to make to sort things out.

Learn to be more assertive or less self-attacking.

These are not easy things to do, so you may have to work hard. When we are depressed our thoughts and feelings are very dismissive – they may say things like, ‘This won’t work for me; don’t be silly; I can’t do it; can’t be bothered; I’m too angry; it’s too difficult’. These are all very common thoughts. The way to deal with them is to expect them, to notice them, but focus on the task anyway. If you put a certain time aside, e.g., five minutes, plan to focus your time on the task. You might also think about whether this feeling is actually linked to angry rebellion and you are really saying, ‘Oh, sod it. I just don’t want to do it, so why should I!’ If that is true, then honestly acknowledge it – be compassionate and understanding of such feelings, but then take a breath and think about how to actually help yourself move forward. Think also that there may have been many times in life when you predicted that things would not work out but they did.

Having small and achievable goals can be helpful as these are the things you want to achieve. At first, depressed people usually just want to feel better. But this large goal needs to be broken down into smaller ones. These smaller goals might be:

To do a little more each day.

To be more assertive with some other person(s).

To spend more time on something I enjoy.

To join a club or charity where I can get involved with other people and feel useful.

To spend more (or maybe less) time with my children.

The most important commitment is to put effort into transforming your depression by training your mind in helpful, compassionate actions. You do this in the knowledge that:

The way our brains have evolved over many millions of years can be very tough on us and give a host of unpleasant feelings and moods.

That is absolutely not our fault – we did not design our brain, choose our genes, or how our early relationships shape us.

But it is up to us to try as best we can to work with our minds to change our mental states.

Commitment is linked to the value we put on things. For example, if I ask you not to express your anger for a week, or to go out even if you’re depressed, you might be uncertain. What about if I offered you £10? Okay £100? Not enough? Okay £1 million. Of course I can’t do that, but think about it – if there is a really big payoff you might put a lot of effort into something. We have to be honest about this. Like a person training to get physically fit, some days will be harder than others – but the clear goal keeps them going. For working on a depressed state of mind, focus on how it will help you to get better and really make that your goal – think of all the benefits – imagine (and see) yourself as ‘feeling better’ and what you are doing now you are better. It is easy to let these slip from one’s mind when it gets tough. It can be useful to set yourself a couple of goals at the beginning of each day or week. Start by setting small goals – the smaller, the better. If things are difficult or you don’t reach your goals, ask yourself some questions.

Were the goals too ambitious?

Could I have broken them down further?

Did I run into unexpected problems?

Did I put enough effort into achieving them?

In my heart of hearts, did I think that achieving them wouldn’t really help?

If it did not go as I wanted, am I being compassionate with myself?

Behavioral experiments

Many therapists encourage us to try what we call behavioral experiments. This means trying out different things, keeping an eye on what works for us, how we might do things differently to make them work better for us, and tailoring them to our needs. This does not mean doing things simply because we’re told to, but trying to see the point of what we’re doing. For example, if you want to get physically fit you might go to the gym and really push yourself even though it’s not entirely comfortable. You learn what works for you and put up with the discomfort because you understand what you’re trying to achieve. Indeed, the discomfort may actually inspire you because you feel it is helping you move forward in your goal of ‘getting fitter and stronger’. We can approach depression like this too.

Take staying in bed. If staying in bed helps you feel better, all well and good, but often in depression it does not. We simply use bed, not to rest and regenerate our energies, but to hide away from the world. Then we feel guilty and attack ourselves for not doing the things we have to do. When you are lying in bed, you may tend to brood on your problems. Although bed can seem like a safe place to be, it can actually make you feel much worse in the long run. The most important step is to try to get up and plan to do one positive thing each day. Remember, your brain is telling you that you can’t do things and to give up trying. You will slowly show that part of yourself that you can do things, bit by bit.

Occasionally, however, because depressed people often bully themselves out of bed with thoughts such as, ‘Get up, you lazy bum, how can you just lie there?’, it can be useful to try the opposite tack. This is to learn to stay in bed for a while, at least one day a week, and enjoy it – read a magazine or listen to the radio and allow yourself to feel the pleasure of it. To practise being able to lie in bed without feeling guilty can be helpful for some people. Imagine that you are exercising that pleasure area of your brain, which really needs exercise.

Designing experiments

It is useful to work on and against our depressive ideas by setting experiments: that is, testing things out and rehearsing new skills. A useful motto here is, ‘Challenging but not overwhelming’. Remember – design your experiments – things to have a go at – to take you forward step by step, rather than rushing into something that has a high risk of failure. Don’t worry if the steps seem too small. If things go a bit pear-shaped, remember it was just an experiment and think about how to learn from it.

Experiments don’t always work out as we hope they will. When I was a shy young student at college, a good friend encouraged me to ask a woman to dance at our college dance. It was noisy, but I got my request across. She turned to her friend, looked at me, looked back at her friend, laughed – and they both got up and walked to the bar! Oh dear. On another occasion I had learned some assertiveness and was in a shop queue when an older man pushed to the front of the queue. People were irritated. I need to do something here, I thought. I’m a psychologist and an assertive one. I left my position at the back and said to the man, quite kindly I thought, ‘Excuse me, look, I’m sorry but there is a queue.’ He looked at me and then said, ‘Why don’t you eff off, you four-eyed git, before I smash your face in.’ My response was of course to say, ‘Absolutely – look – I’m off right now!’ So even the best-intended plans don’t always work out!

If we try things and they don’t work out, we can try to find out why. Was there anything about it that was a success? For ex ample, you did try and you can learn to cope with these setbacks and try again in the future. One can learn not to be so fearful of failing or rejection – it is unpleasant but nothing more. My college friend thought it was funny that the girls walked off but said, ‘That’s typical, you’ve just got to keep trying. Somewhere in the hall a girl will want to dance with you, you’ve just got to find her. On attempt 252 maybe.’

We also need to think whether we were attempting too much. Were our expectations too high? In the case of tackling the aggressive man the answer is probably yes – he was a big fellow, and I am by nature a coward. Did your negative thoughts overwhelm you? Did you really put the effort into it that you needed to?

People can generate and write down alternative thoughts and ideas and behaviors. They may be very casual about it and just look at the words without thinking their meaning through, or trying to put feelings of kindness and understanding into those alternatives. In the back of our minds might be a thought, ‘This approach can’t work.’ So we stack the experiment against ourselves before we begin.

So we may need to use the courageous part of our compassionate mind to tell ourselves in a friendly, supportive way:

Look, I know this is hard, and yes, it is a shit being depressed, but let’s not stack things against myself. Let’s give it a fair go. After all, what have I got to lose? If I were helping a friend, I’d know how tough it is but I’d also encourage them to give it a go. Let’s go through this step by step.

Getting out of depression takes effort, and this is especially true if you are trying to help yourself. It is the same with getting physically fit. It would be no good putting on your trainers and running to the garden gate and back – you have to push yourself more than that (assuming you don’t live in a stately home where the garden gate is a mile away). It is very understandable to find this tough going, and it may be that there are times when we need some extra help from friends or professionals. There’s no point in berating ourselves if we’ve tried our best and have found it too hard.

Blocks to becoming active