In the spring of 1941 the ECA interagency teams looked beyond Japan’s vulnerability in war materials. The Project Section’s zeal for economic warfare prompted investigations of Japan’s imports of food, clothing, and shelter materials on the premise that in total war, even of the economic variety, no moral distinction need be drawn between soldiers and civilians. Identifying targets for embargo proved a challenge, however. The Japanese civilian economy did not widely depend on U.S. resources—oil, a special case, is dealt with in chapter 13—but the United States did supply some commodities of importance to Japanese agriculture and consumer life. If embargoed, the people would suffer a decline in standard of living, with the unspoken supposition that they might dissuade their leaders from aggressive foreign policies.

Japan’s problem of feeding its own citizens was widely known.1 In Tokugawa times, before Japan opened to trade in the mid-nineteenth century, rice culture was productive enough to feed a stable population of about thirty million.2 After 1860, birth rates rose and death rates fell. Population grew steadily at 1 percent per year, despite emigration. In 1937, 30.8 births and 17.0 deaths per thousand contrasted with U.S. figures of 17.1 and 11.3, a natural accretion rate four times as great as in the United States during the Depression. By 1941 the population had grown to seventy-three million, 143 percent higher than at the time of Commodore Perry’s visit.

However, land under cultivation had barely expanded, from 12 percent of Japan’s area in the 1880s to 16 percent in 1921, including the valleys of Hokkaido, suited only to crops of low nutritional value. At that point virtually all the arable land had been planted. The rest of the terrain was too mountainous for farming. Yet Japanese food production rose 1.3 percent per year, 75 percent between 1880 and 1920, even as farm workers migrated to the cities. The Meiji government encouraged rice culture with subsidies, tariffs, and low taxes. In 1918 soaring rice prices provoked riots, a traumatic event that impelled the government to seek food self-sufficiency within the empire. Subsidized rice culture in Korea and Formosa paid off handsomely. By 1941, when Japan imported 20 percent of its food, the yen bloc as a whole was self-sufficient in rice in most years.3 In Japan proper, each cultivated square mile of the home islands fed 3,596 people, about twenty times the ratio of the United States (U.S. 1950 figures).4 The gain in productivity resulted in part from superior strains of rice and better irrigation, and farm families may have worked longer and more efficiently, but such factors had topped out by the 1930s. The key factor of productivity had been extravagant applications of fertilizers, more intensively than in any other nation of the world.

The Japanese diet was spartan. In 1934–38 the average intake of 2,180 calories per capita ranked well below the 2,800 to 3,100 of Western Europe and the 3,150 calories of the United States (although it was 200 calories higher than India).5 The Japanese people consumed five-sixths of their calories as grains and starches, over half from rice alone. The diet was low in protein, fruits, and vegetables. Prewar Japanese were short in stature—one source cites five feet three and a half inches for males and four feet ten and a half inches for females—so that relative to body mass the Japanese people were not generally undernourished.6

In 1940 and 1941, due to crop failures in Korea, Japan imported non-empire rice. It bought largely from French Indochina, which by then was virtually absorbed into the yen bloc, and from Thailand, which was independent but susceptible to political pressure. Only small amounts came from British Burma. Some American vulnerability analysts mistakenly suggested that Japan could not afford to buy more rice from elsewhere.7 The most perceptive correctly understood that coping with vulnerability in food required ever greater productivity. A slight setback might lead to significant undernourishment. (The “starvation blockade” of Germany was well understood as a decisive factor of World War I.) Probing for weaknesses, the analysts identified two of the three essential fertilizer minerals as viable targets for sanctions. The yen bloc was self-sufficient in nitrogen, but Japan had to spend hard currency for most of its phosphorus and nearly all its potassium needs. (Plant food values are expressed as percentages of elemental nitrogen [N], phosphoric oxide or phosphate [P2O5], and potash or potassium oxide [K2O] contained in fertilizers.) In late 1939 the European war disrupted normal supply channels, leaving the United States as the main accessible source of phosphate and potash. Therein lay an opportunity to pressure Japan by embargo, although necessarily of gradual effect because those minerals leached out of farming soils gradually over two or three growing seasons. Embargoes would not precipitate an immediate food crisis but would eventually undermine the health and nutrition of the Japanese people.

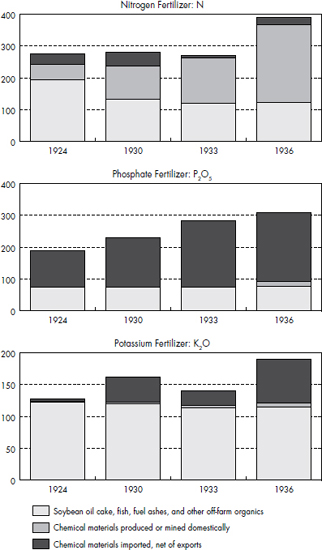

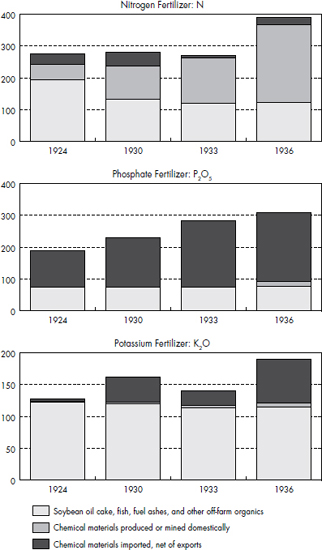

Since earliest times Japanese farmers had applied to crops the “green manure” plant and animal wastes of farms and human “night soil” collected in the villages. But green manures, containing about 1 percent plant nutrients, required much labor for limited gain. Supply could not increase much. At the turn of the century Japanese agriculture turned more to off-farm organics containing 10 to 15 percent nutrients: sardines and fish processing wastes, “oil cake” residue from pressing Manchurian soybeans, and ashes from burning wood and charcoal.8 The organics, however, could not keep up with six hundred thousand new mouths to feed every year. In the twentieth century Japan’s future depended on industrial fertilizers (chart 14).9

Farmers grew rice, the staple food of Japan, in flooded paddy fields where soil chemicals and bacteria fixed nitrogen from the air into compounds that plant roots could absorb. Wet rice culture tamed the vagaries of climate and typhoons, maximized nutrient release, and suppressed weeds, but water migration limited the efficiency of the natural process. Japan needed nitrogen fertilizer, which stimulated growth of large, dark leaves, forcing rapid maturity and allowing the planting of two crops per year. Ammonium sulfate crystals containing 20 percent N, drilled a few inches into wet soils with acidity neutralized by limestone, were highly efficient for rice because the ammonia remained in solution through the growth cycle. Rice yields could be increased markedly, for example, from twenty-four hundred pounds to better than four thousand pounds per acre by application of one hundred pounds of chemical nitrogen.10 In the 1930s Japan successfully expanded ammonia production. Output in Japan and Korea rose fivefold, to a peak in 1941 of 524,260 tons of contained nitrogen. Japan alone ranked third in world production.11 Byproduct ammonia, from converting coal to “town gas” for illumination, and imports, both formerly important, dwindled to less than 10 percent of Japan’s supply. Production of calcium cyanide, another nitrogen compound fixed from the air, grew but peaked in 1937. The nitrogen industry also produced nitric acid for chemicals and explosives, but most of its output went to agriculture.

CHART 14 Japan Proper: Fertilizer Mineral Sources, 1924–1936

OCL, “Place of Foreign Trade in the Japanese Economy,” vol. 1, pt. 2, tables II-7 to II-11.

In April 1941 the U.S. vulnerability analysts described Japan’s demand for ammonium sulfate as “insatiable.” Tokyo had declared a national goal of 2,266,000 tons of capacity by 1 January 1938. The analysts estimated the home islands were already producing 1,600,000 to 1,950,000 metric tons of nitrogen in fertilizers (and Korea about 50 percent as much). But they supposed Japan could not add capacity due to bottlenecks of equipment, electric power, and sulfur pyrites for sulfuric acid needed in processing, and diversions of nitrogen to explosives. Japan imported ammonium sulfate from Manchukuo, but in the late 1930s it also bought an average of 131,000 tons per year from Germany. With Germany cut off in 1940, it bought a minor quantity of U.S. product at premium prices until restricted by licensing rules. In reality, Japan exported nearly as much nitrogen in mixed fertilizers to the colonies and neighboring countries as it imported. Misconstruing the triangular trade, the Americans recommended continued denial of nitrogen exports in hopes of pressuring Japan politically.12

When war came, the empire maintained high ammonia and ammonium sulfate production during the first two years. Only in 1944 did it fall below the prewar peak, by one-third. Yet rice production was actually higher in 1942–44 than in the preceding three peacetime years, even though acreage declined by 3 percent and labor and tools were in short supply, an indicator of sufficient nitrogen application.13 Realistically, Japan was never at risk from U.S. interference with nitrogen. Wishful thinking that it might be vulnerable was a clear example of overreaching among the new bureaucracies.

According to wartime U.S. studies, Japan reached the point of diminishing returns in rice fertilization in the early or mid-1930s, that is, the percentage increase of the rice harvest was one-third to one-half the percentage increase in fertilizer applied. As an alternative, Japan increased plantings of wheat, barley, potatoes, and naked barley (a hulless variety freed from the coating by threshing). Phosphate addition was essential for dry farming of these grains and starches in northern valleys and cool uplands. Phosphate enhanced rapid growth, developed better roots, and accelerated tillering (sprouting) and faster ripening, enabling multiseason cropping. It also retarded plant diseases and provided insurance by underwriting yields in bad climate seasons. The dry grains responded to phosphate applications with yield increases up to an extraordinary 50 percent. By 1941 they furnished 20 percent of Japan’s calories with the help of imported phosphate minerals.14 Potatoes and sweet potatoes, 7 percent of the national diet, responded to phosphate with 7 to 29 percent higher yields. In comparison, phosphate increased rice yields only 5 percent or so because paddy water converted enough soil phosphorous to soluble compounds.

World agriculture relied on shallow beds of phosphate rock pebbles mined in Florida, in North Africa, and on Pacific islands. Insoluble phosphate rock contained up to 77 percent BPL, “bone phosphate of lime,” a commercial measure of phosphate content. A ton of rock reacted with sulfuric acid yielded 1.5 tons of superphosphate, a chemical containing 20 percent P2O5. In the 1920s Japan developed a large superphosphate industry. By 1941 forty-six plants located near deposits of sulfur pyrites produced 1.5 million metric tons of superphosphate from 1 million tons of imported rock, all of Japan’s needs and a surplus for the colonies, plus phosphorous chemicals.15

Japan imported phosphate rock from four regions. Prospecting in the 1920s had turned up deposits on its Pacific Mandated Islands. Production on Angaur, in the Palau group, reached 143,000 tons in 1939. Smaller productions commenced in the 1930s on Peleliu in the Palaus, Fais in the Caroline Islands, Saipan in the Marianas, and, nearer home, Daitojima near Okinawa. The empire’s production of 375,000 tons of rock provided 32 percent of Japan’s rising needs in 1939. North Africa, primarily Egypt and to a lesser extent Morocco, was a steady supplier. “Land pebble” rock from central Florida, shipped through the port of Tampa, was another reliable source. The closest non-yen sources—freight costs mattered for a commodity worth only three dollars a ton—were four tiny Pacific islands controlled by British, British-Australian, or French enterprises. Mines on Christmas Island, south of Java, and Makatea, a French island in the Tuamoto group, shipped mainly to Japan, but their outputs were small. On the other hand Nauru and Ocean Islands, atolls mandated to Australia, had a combined capacity of 1,250,000 tons—the world’s fifth largest producer—but they supplied Australia and New Zealand and only a residual bit to Japan. By 1940 the Pacific phosphate islands had neared practical limits of production.

The war in Europe curtailed two of Japan’s foreign phosphate sources. Egypt was cut off after Mussolini entered the war in June 1940. In December 1940 two German raiding ships bombarded the loading docks and booms at Nauru and sank several special freighters, putting the operation out of commission. The other phosphate islands diverted sales from Japan to Australia and New Zealand. (Ironically, Japan had permitted the German ships to use its Caroline Islands bases.) Japan hurriedly developed small mines in China and French Indochina.16 In the emergency, however, the United States offered the largest accessible source of phosphate rock. Florida’s mines supplied almost all U.S. agricultural needs, and exported 1.1 million tons until loss of markets in Europe due to the war. Phosphate reserves were so enormous, and production so expandable by simple dredging and washing in shallow pits, that the mineral was not critical nor even “strategic,” according to a congressional committee report in 1938 in response to Roosevelt’s inquiry.17

Nevertheless, Japan did not spend its dollars for American phosphate. The vulnerability specialists assumed, wrongly, that Tokyo was focused on production of rice, the crop least responsive to phosphates, because labor shifting to industry inhibited expansion of dry grain farming. They also calculated that it had been importing excessively and had built a one-year stockpile of rock and superphosphates. Thus they concluded that a phosphate embargo would have “minor if any effect” unless all sources, presumably including the empire island sources, were cut off. They did not evaluate any crop loss Japan might suffer.18

In fact, Japan’s stockpile was inadequate. Superphosphate manufacture declined rapidly from a 1940 peak of 1,846,000 tons, by 50 percent within two years and nearly 100 percent after mid-1944 as U.S. submarines isolated the Japanese-controlled islands. (Nauru and Ocean were occupied by Japan but bypassed by the U.S. offensive, surrendering at the end of the war along with Angaur.) The prompt phosphate shortage had dire consequences. Whereas Japan maintained its prewar rice production until the last year of the war, the harvest of wheat, its second most important foodstuff, dropped precipitously after 1940 despite acreage expansion. Barley declined soon after. It was a rare instance of U.S. analysts, perhaps lulled by Washington’s “nonstrategic” attitude toward phosphate, underestimating the deprivation a shortage would inflict on the Japanese people.19

Potassium improved the health and vigor of grains, benefits important in cloudy weather with low sunshine.20 In traditional Japanese agriculture wood ashes, and seaweed in some places, had provided potassium. Until 1914, mines in Germany supplied the world with potassium sulfate, a mineral containing 50 percent K2O. The World War I blockade of Germany drove prices above $100 per ton, raising havoc with global agriculture, especially in the United States, where corn, cotton, and tobacco were heavy potassium consumers. After the war France and Spain entered the export trade, and the U.S. government subsidized prospecting, successfully, at a cost of $2 million, a lordly sum for the times. In the 1930s U.S. firms commenced production from deep-lying beds of potassium chloride containing 60 percent K2O in New Mexico, and from brines of Searles Lake, California. Because of freight economics, however, the United States continued to import half or more of its needs from across the Atlantic while exporting to Japan. The Spanish Civil War and the general European war forced the United States back on its own production, which proved so readily expandable that by 1941 it was self-sufficient.

The case for vulnerability of Japan in potash was persuasive. Potassium from organic sources and some local low-grade salts fell short of needs in the 1920s. Japan turned to foreign potash minerals. In the late 1930s imports from Germany and the United States averaged 180,000 tons per year, a small tonnage compared to 1 million tons of phosphate rock; however, high-grade U.S. potash sold for forty dollars per ton versus three or four dollars for rock, and freight was more expensive due to the train haul to the West Coast and special handling to keep the soluble salts dry. Thus Japan’s import bill for each mineral was similar, $3 or $4 million per year. The European war limited its potash imports to 75,000 tons, some from the United States where some fertilizer plants resold for a quick profit despite voluntary rationing by the mining companies (which extracted largely from federal lands) to reassure American farmers. The vulnerability analysts wondered if the lower imports were due to Japan’s lack of hard currency, which was hardly a problem for such minor payouts.

The vulnerability studies concluded that potash was Japan’s Achilles heel and that an embargo would be the strongest possible pressure the United States could inflict on the Japanese people, albeit one that would pinch gradually:

The results of a failure to apply potash to the soil, in quantities necessary for maximum crop yields, will be manifest in Japan in the first year of sparse application following cessation of imports. The depletion of potash stocks and the exhaustion of the soil should cause a critical situation to develop in the second year. . . . It would be impossible to produce potash in Japan in appreciable quantities from uneconomical sources without large investment in research, plant equipment, and a delay of years.

The analysts predicted that an embargo of commercial grade potash, along with British closure of a Dead Sea brine plant in Palestine, interference with Spanish shipments, and preclusive buying of Chilean salts, would totally deprive Japan. A presidential order of 10 January 1941 placed potash salts exceeding 27 percent K2O under export control, leaving available only “manure salts” of very low grade. For such grades Japan would have to spend more dollars for potassium than for oil, hypothetically because shipping was unavailable. Nevertheless, because Japan might out of “dire need” buy 27 percent grade manure salts, the analysts recommended embargoing them.21

The decline of potash available to Japan was sudden and extreme, a drop of two-thirds in 1941 and almost 100 percent thereafter. It was far more drastic than the 40 percent decline of phosphate supply and the insignificant drop of nitrogen in the same period. During the war a marked decline of dry crop harvests reflected shortages of imported fertilizer minerals. The U.S. analysts may have exaggerated the impact of an absolute cut-off of potash compared with the partial cut-off of phosphates as the benefits of the latter were greater. Taken together, an implied crop deficit from lack of mineral imports of, say, 30 percent of dry grain harvests and a few percent of the rice crop, might equate to a loss of 7 percent of Japan’s grain and 5 percent of its overall calories. Meanwhile population was growing 1 percent annually. The U.S. experts’ supposition that a fertilizer blockade would, in time, cause a disastrous food shortage was fundamentally correct. It constituted one of the harshest threats of economic war against the Japanese population.22

The yen bloc was self-sufficient in nonstarch foodstuffs, which provided one-sixth of Japan’s nutrition. The vulnerability studies recognized the importance of protein for health and vigor but they estimated that the Japanese diet contained only 3 percent protein, 65 calories per capita per day, nearly all in three ounces of fish. (Lacking grazing land, Japan was thought to rank lowest in per capita meat consumption of any major country, about 15 percent that of western countries, less even than India where cattle slaughter was taboo in places.) The analysts had trouble calculating the fish supply. The catch of edible fish was about 2.2 million metric tons, but another 1 to 1.5 million tons of sardines were thought to be pressed for cooking oils and fertilizer residue. They reported that potential U.S. interference would have to be indirect, through embargoes of oil fuel, hemp for nets, and steel and lumber for vessels. During World War II shortages of fuel and materials, requisitions of vessels, and sinkings indeed reduced the catch drastically.23

It is surprising that the Japanese did not consume more soybeans, a high protein food. The available supply was large, 75 percent imported from Manchukuo and 25 percent home grown. Mills extracted cooking oil and sold the residue mostly as fertilizer. Soybeans were eaten mainly in miso paste and shoya sauce, condiments of low caloric value. Other than oil, soybean consumption was a minuscule 8 grams per day in 1941, less than 1 percent of caloric intake. Therefore no vulnerability team investigated soybeans. Yet as the war progressed the Japanese of necessity consumed more and more, shipped via Korea. The consumption of soybeans as food rose to 13 grams per capita in 1945. But more than sixty years after the war the average Japanese person consumes about 40 grams of soybeans per day in tofu, enriched flour, and other foods, along with much more protein in fish and meat.24

Edible oils for food and cooking provided an estimated 2 percent of the Japanese diet, forty calories per day. Japan produced 800 million pounds annually from sardines and soybeans, and exported 350 million pounds. Japan did not usually buy animal fats, although, mysteriously, imports of lard worth $1.8 million amounted to 3 percent of all Japanese purchases from the United States in 1941. Perhaps Japan was hastening to spend its dollars for an available product. The analysts saw no opportunity for harming Japan other than cutting off copra (dried coconut) from the Philippines and Allied colonies.25

The Japanese people had a taste for sweets. Sugar intake of 140 calories per day provided 6.5 percent of their calories. Imports of about a million tons per year came mostly from Formosan sugar cane and smaller amounts raised on Okinawa and Saipan. Sugar beets were grown on Hokkaido. Fertilizer needs were not great. No opportunity for U.S. pressure was apparent. The vulnerability project ignored sugar as well as the remainder of the Japanese diet, a miscellany of fruits, vegetables, eggs, and dairy products raised within the yen bloc.26

The vulnerability teams rendered split opinions about the two most common clothing fibers. They recommended embargoes of wood pulp and salt, the basic ingredients for rayon manufacture, while shying away from an embargo of raw cotton because of the plight of American farmers.

In the 1930s Japan greatly expanded production of long-filament rayon, a yarn extruded from bleached sulfite pulp chemically digested in caustic soda. For durable textiles it imported pure alpha-cellulose “dissolving pulp” from the spruce and hemlock forests of Scandinavia and North America that contained long-chain molecules relatively free from lignin. In 1935 Japan (along with Germany and Italy) decided to conserve foreign exchange by substituting low grade pulp from the inferior softwoods of northern Japan, Korea, and Sakhalin. Processing of local pulp yielded short rayon fibers that were spun together into rayon staple yarn, far less durable than cotton or long-filament rayon. After the Sino-Japanese War began industrial laws mandated a switch from cotton, the most important textile, to rayon staple cloth. In 1938 rayon clothing surpassed cotton. But, unless blended with sturdier fibers, staple cloth lost 50 percent of its strength when wet and was liable to fall apart in Japan’s humid weather. The rayon mills had no standards for pulp and poor quality control. A Tokyo Women’s Federation petitioned for sturdier goods. The fabric broke at the first washing, the women said, looked wrinkled, and “lasts not more than one day.”

Japan’s five-year plan anticipated self-sufficiency in rayon pulp by 1942, but in 1940 supply fell short of need by 200,000 tons. It imported 123,000 tons, 96,000 tons of which came from the United States, a jump of U.S. sales from $1.8 million in 1939 to $6.3 million in 1940. With Scandinavia inaccessible due to war the U.S. vulnerability analysts saw an opportunity. They recommended embargoing rayon pulp exports, in cooperation with Canada. They expected that Japan would maintain a reduced output of staple fiber from local pulp, but fabric quality would decline further, another blow to the quality of Japanese life.

A second necessity for rayon production was caustic soda (sodium hydroxide, NaOH, also known as lye), an alkali derived from common salt that dissolved the wood pulp and also was used for manufacturing dyes and soaps. Japan consumed 2.5 million tons of salt, including large tonnages for food processing, but was only one-third self-sufficient because rainy weather interfered with evaporation from seawater ponds. It imported salt from East Africa, a shipping burden for a bulky mineral worth $2 per ton, and from China. The five-year plan targeted 1 million tons from China by 1943, although typhoons upset production there from time to time. The United States supplied a minor 100,000 tons. The vulnerability analysts reasoned that caustic soda was essential to the Japanese economy and that a shortfall would have disastrous economic effects. They recommended an embargo along with a British halting of East African salt. After the war it was learned that rayon fabric production had already slipped from 1.086 billion square yards in 1939 to 633 million in 1941.27

Raw cotton was the only major commodity for which U.S. economic needs overrode the impulse to punish Japan. Unlike most commodities, there was a glut of cotton due to war. The textile mills of Britain and Europe had cut back drastically, and cotton-raising countries were buried in surpluses. An embargo was a hopeless prospect.

In normal times the Japanese cotton textile industry provided 70 percent of the country’s clothing fabric and a large surplus for export to the yen bloc, East Asia, and the Americas. Japan grew no cotton; before the China Incident its factories processed 1.6 to 1.9 million bales (of 473 pounds each) of foreign raw cotton. After 1936, to conserve foreign exchange, Tokyo enacted laws to eliminate cotton from most domestic clothing in favor of rayon, because pulp comprised only 10 percent of that fabric’s cost whereas raw cotton comprised 50 percent of cotton fabric cost. A “link system” allowed mills to import raw cotton only for exports, further limited in 1938 to exports only to non-yen countries. Cotton was channeled to military uniforms, work clothes, and to some blending with rayon. Domestic consumption shriveled to 617,000 bales in 1939. Imports of wool, primarily Australian and South African and used for the military, were also sharply curtailed. Silk of course, was plentiful after the financial freeze but the quantity was too small to matter.

Japan historically imported half its raw cotton needs as long-staple U.S. cotton, half as short-staple from India and minor amounts from China and elsewhere. In the crop year August 1940 to July 1941 Japan slashed its already low purchases, largely at the expense of the United States, from which it bought only 200,000 bales, switching to long staples from Brazil and Peru. U.S. analysts expected further cutbacks due to large inventories of cotton and textiles. It appeared that China could provide most of the 500,000 bales minimum need, although Chinese short staple was of such weak quality that it ordinarily was used for nonwoven applications such as padding. But quality was improving, and Japanese-owned mills in occupied cities might serve Japan by depriving Chinese consumers.

It would have been absurd for the Department of Agriculture vulnerability analysts to propose an embargo. “Surpluses of cotton throughout the world are abundant to the point of being burdensome. . . . Cotton [growers] will face impoverishment or even disaster,” they wrote. Preclusive buying was inconceivable because surplus inventories of 14.5 million bales in the United States alone were about one and a half years’ needs and were mostly financed by loans from the U.S. Reconstruction Finance Corporation. To buy up 8.5 million surplus bales in the rest of the world would cost $300–350 million. Faced with political clamor from the depressed southern cotton belt, the analysts used the occasion to appeal for international agreements to curtail production everywhere, not to embargo America’s largest foreign customer.28

Japan’s rather small leather industry depended 100 percent on imported cattle hides, primarily from China, but 20 percent from the United States and some from Argentina and Australia. Leather footwear was a luxury for civilians; wooden “geta” clogs were a necessary substitute. U.S. hide exports had been subject to license since 1940. The vulnerability analysts recommended an embargo, which would be meaningful only if Argentina and Australia collaborated, and even then not very damaging. U.S. sheepskins, 14 percent of the Japanese supply, offered even less opportunity because Manchukuo and China were the major sources. They also advised embargoes of vegetable-based chemicals for tanning leather, but substitutes from China and from synthetic chemicals would suffice for Japan.29

Rubber was the only tonnage industrial commodity more readily available to Japan than the United States. In addition to tires for military vehicles and planes Japan manufactured car and bicycle tires and tubes, industrial belting, boots, and shoes with rubber lowers and canvas uppers. It exported 20 to 30 percent of such manufactures, largely to the yen bloc. Most of the world’s natural rubber trees grew on Southeast Asian plantations. (Synthetic rubber was not produced in quantity in 1941.) British Malaya was the largest supplier, especially to the United States. French Indochina and Thailand, drawn “into the economic if not the political orbit of Japan” in 1941, exported 115,000 tons, well in excess of Japan’s calculated demand of 65,000 tons. Japanese control there edged out U.S. buyers and was an affront to U.S. international influence, said the analysts indignantly. Yet they did not suggest a Malayan embargo. The only remaining option, beyond the 1940 embargo of reclaimed scrap rubber, was an unlikely interference with Thai and Indochinese shipments to Japan by force.30

Japan relied on lumber for construction more than any other country. Houses damaged by fires and earthquakes needed replacement routinely. During the economic expansion of the 1930s, as villagers migrated to urban jobs, construction of dwellings soared in crowded cities. The forests covering more than half of Japan yielded ordinary dimension lumber sufficient for local use, and for the yen bloc where skimpy forests were suitable only for pulp. Yet Japan lacked the large trees for logs up to twenty-four inches in diameter and twenty to sixty feet long needed by its important plywood industry. Douglas fir was the best plywood core material, which Japan imported as logs and “Jap square” hewn logs from the U.S. Pacific Northwest and Canada. Other woods sufficed for plywood veneers. After 1937 Japan severely restricted lumber imports in order, in the opinion of U.S. analysts, to save foreign exchange. It substituted lauan, a cheap hardwood from the Philippines and Southeast Asia, for plywood cores. By 1939–41 U.S. exports had dwindled to $1.5 million or less per year, down 70 to 90 percent from earlier peaks. A vulnerability team recommended embargoing all logs from North America, the Philippines, and British and Dutch Asia to “seriously affect” the plywood industry. In addition, an embargo of “airplane grade” Sitka spruce, though small in value, would impair construction of training aircraft. Even cedar for pencils ought to be embargoed.31

A vulnerability team rummaged in odd corners of trade data to find U.S. commodities enjoyed by Japanese consumers that might be blocked. They saw little real opportunity. The Japanese were avid readers, but the yen bloc was self-sufficient in the pulp used to make paper. Gum rosin, a turpentine chemical for soap, paper, and paints, was not an essential product, and an embargo would hurt American producers. Borax from California, a chemical for household products, was already embargoed and Japan was thought to have stockpiled enough a few years earlier.32 The United States formerly sold ten thousand passenger automobiles per year, assembled or crated for assembly in Japan, and auto engines and parts. By 1940 Japan’s imports of three cars per week may have been for foreign diplomats and businessmen.33 No study was necessary.

The interdepartmental vulnerability teams of 1941 identified civilian commodities that if embargoed by the United States would lower the standard of living in Japan, by outright food shortages in the case of fertilizer minerals and oil and by debasing the quality of clothing and construction. They made no attempt, however, to quantify the impact of halting exports on the standard of living or the economy as a whole, nor did any American agency do so before the war. Toward the end of this book a plausible scenario of economic squalor, based on post-1941 studies, presents such an evaluation (chapter 18).