Extraordinary as it may seem, no agency of the U.S. government analyzed how the financial freeze would affect the Japanese economy and people in their entirety. Neither before nor after 26 July 1941 did the administration attempt to forecast Japan’s national product, national income, employment, standard of living, or health and nutrition under freeze conditions. The oversight is astonishing. U.S. civilian and military officials had studied Japan’s dependence on foreign trade for more than four years. They understood that a nation heavily dependent on overseas commerce, especially with the United States, would suffer grievously when its international financial resources were immobilized. It is hard to imagine a similar oversight in later times. During the Cold War, from 1945 to 1989, the United States alone or with its allies imposed economic sanctions against several dozen nations on seventy-five occasions.1 In the computer era Washington must surely conduct thoroughgoing analyses of expected results. Such was not the case in the less sophisticated era before World War II.

After the freeze of 26 July 1941 U.S. civilian and military agencies did comment, here and there, on Japan’s economic difficulties. They lacked current information other than the insights of the embassy staff members in Japan who relied on their contacts among Japanese and foreign businessmen and whatever they could glean from the local press. Most prominently, Francis S. Williams, the U.S. commercial attaché in Tokyo since 1934, sent commentaries to Washington based on “unofficial reports and personal studies over several years.” Grew endorsed his findings.2 Williams and a few observers in Washington addressed limited aspects of Japanese economic life under a peacetime freeze. They did not evaluate the economic impact of a Pacific war on Japan, except for estimates of oil and shipping supply and demand. Their commentaries fell into three categories: exhaustion of stockpiles, declines of specific industries, and platitudes—often lurid—describing Japan’s dire prospects.

Neither, it seems, did Japanese military or civilian agencies undertake a comprehensive analysis of their economy under the freeze between 26 July and 7 December 1941. Like their U.S. counterparts they evaluated the effects of the freeze in three aspects: stockpile exhaustion, travails of a few key industries, and dramatic outcries about the pauperization of Japan. They did not forecast the macroeconomic effects of the freeze on the total economy; they regarded civilian needs as a residual problem after military needs were provided for. Unlike the Americans, however, Japanese analysts turned immediately to considering the wartime economics of their country. Within a few weeks after the freeze began it was clear that it was absolute. Opinions in Tokyo moved toward assuming that negotiations would fail and war would erupt before the end of the year. Japanese planning staffs primarily contemplated their nation’s economic ability to fight a three-year war—similar to the time frame of the U.S. War Plan Orange—by evaluating oil, steel, and shipping, economic activities that could be appraised with some validity for at least the first year of war.

U.S. observers tried to guess at the adequacy of commodity stockpiles in Japan, usually expressed as the number of months on hand at pre-freeze rates of consumption. They understood that the Imperial navy and army held oil inventories directly, and that the stores for the general economy were controlled by other government agencies. U.S. estimates about civilian oil stocks, if no war occurred, ranged from six months cited in press articles to Harry Dexter White’s guess of one year.3 Williams believed nonnaval stockpiles plus local production were sufficient for ten to twelve months at reduced usage rates. “The bottom of the barrel is plainly in sight,” he wrote in November, but Ambassador Grew had pointed out that rigorous conservation would extend stockpile lives.4 Little was known about other commodities. A report to the chief of naval operations in October merely guessed that Japan would exhaust essential stocks other than oil in six months.5

In Tokyo, after Germany attacked the Soviet Union, the Cabinet Planning Board accelerated work on a plan to mobilize materiel. It reported to the cabinet on 29 July 1941 that civilian stocks of nine petroleum products and five other commodities would be exhausted very soon if consumption continued at the 1940–41 rate and if no imports arrived, except the minimal amounts from the “self-defense zone” (the yen bloc) and the “first supply zone” (Indochina and Thailand). Military storage tanks held most of the refined products: heavy fuel oil for the navy, motor gasoline for the army, and aviation gasoline for both. Oil products for the civilian economy were desperately short: ordinary gasoline at 2.5 months’ supply and diesel oil at only 0.3 months’ supply, until crude oil stocks of 4 to 6 months could be processed to provide some relief. Other commodities were disappearing. Manila hemp for fishing, for example, would be gone in one month. The planning board concluded that “the Empire will shortly become impoverished and unable to hold its own.” The cabinet ratified the findings on 22 August.6 On 6 September, Teiichi Suzuki, president of the board, reviewed the recent history of stockpiling. From late 1940 through February 1941 Japan had rushed to purchase about $154 million of “special imports,” yet inventories remained far below needs. A final review of stockpiles, completed on 23 November 1941, predicted that if consumption of eleven critical commodities continued according to plans, eight would have fallen more than 50 percent by 1942. Caches of copper, zinc, and carbon black would be almost gone. Only wool would remain adequate, presumably due to yen bloc supplies and rationing.7

The principal attempt by the United States to evaluate the dependence of Japanese industries on foreign trade had been conducted in April–May 1941 in the vulnerability studies prepared by interagency committees of experts for the Export Control Administration. The committees analyzed the effects of current and future sanctions on trade in specific commodities that Japan bought from or sold to the United States and its Allies (see chapters 10 through 13). None of the project teams quantified Japan’s aggregate economic troubles under an expected dollar freeze, and only a few extrapolated their findings into evaluations of broad economic effects, notably those reporting on Japan’s dependency on foreign mineral fertilizer. None measured quantitatively the effects of commercial isolation on Japan’s ability to support its population. The vulnerability project was far too fragmentary for evaluating Japan undergoing a long-term crisis. In any case, the dominant initiative for economic war passed from the ECA’s export squeeze to the Treasury’s financial freeze in the summer of 1941.

After the freeze a few fragmentary comments on Japanese industries circulated in Washington. On 1 October, Harry White, responding to Morgenthau’s inquiry about an article in the journal China Today predicting a rapid collapse of Japan, reviewed a few industries. He thought the steel mills could scrape by for a year by consuming more ore and pig iron and less scrap. Cotton textile production would drop to 50 percent of normal by the spring of 1942 (less than a 75 percent drop the article predicted), limited to processing raw cotton from the yen bloc and possibly South America. The Japan Federation of Cotton Spinning Companies had already restricted yarn operations to 50 percent of capacity. As to raw silk, White thought that demand would drop by half to two-thirds, a disaster to rural Japan, but he thought the slack could be taken up by domestic consumers. He naïvely misunderstood the impracticability of substituting the small volume of expensive silk for the vastly larger yardage of cotton piece goods that normally clothed the people. Attaché Williams understood that not much silk could be consumed in Japan, rendering the economic blow “particularly staggering.” Grew reported great discouragement among Japanese businessmen. He and U.S. Army intelligence noted farm scarcities due to severe controls and rationing, compounded by flood damage to crops and transportation problems. No U.S. analyst, however, opined that Japan faced starvation in the near term. Naval intelligence flatly stated that food was not a problem.8

Among Japanese planners, oil and shipping were the industries of greatest concern. In July 1941 Japan halted the expansion of steel plants, ironically for lack of steel. Suzuki later reckoned that in the fiscal year ended 31 March 1941, 26 percent of the available 4.82 million tons of steel (12 percent below a planned 5.5 million goal) had gone to the military, whereas in the current fiscal year the army and navy took 45 percent despite a 10 percent lower availability. Yet the Imperial Navy in October demanded more steel for warships and merchant vessels. The Japanese army relinquished a tonnage from its allocation, temporarily sparing the economy. Nevertheless, the steel bottleneck loomed large as a reason other economic outputs were projected to drop an average of 15 percent.

The Japanese staffs studied oil most intensively. National reserves of crude and products stood at 42.7 million barrels in March 1941. Hope for synthetic oil from Manchurian shale was revealed as a pipedream; lacking high-pressure reaction cylinders from Germany, only 4 percent of the hoped-for production of gasoline, and no avgas, had been achieved. On 5 November the Cabinet Planning Board demonstrated that the fantasized self-sufficiency goal of about 40 million barrels of products per year from oil shale would absorb 380,000 miners, steel equal to half the navy’s long-term ship program, consume 30 million tons of coal every year, and require nearly a billion dollars invested over seven years. On 14 November army leaders declared a national need for U.S. and Dutch oil of 56 million barrels per year, which Prime Minister Tojo reduced to 42 million barrels.

Shipping, a crucial variable for Japanese prospects in a Pacific war, was subjected to detailed studies that evaluated naval operations, sinkings, and new construction projected over three years of war. Suzuki’s board reviewed the achievements of the 6.5 million tons of merchant shipping available in April–September 1941, of which 3 million tons had delivered 5 million tons of cargo per month for the civilian economy. Concerned about further requisitions for combat, Suzuki warned that 3 million tons of shipping was the necessary minimum to sustain economic production in wartime. Although neither the Japanese nor Americans evaluated shipping under a continuing peacetime freeze, with transpacific trade ended and Japanese vessels restricted to coastal routes no further than Thailand, the problem would have appeared manageable.

Tokyo devoted little attention to the general economy, and apparently none to the suffering of the Japanese people under a long-term freeze. An army estimate in September 1941 indicated that civilian material use was down 45 percent from already depressed levels. Studies alluded to severe fuel shortages for land transportation, fishing and factories but suggested no solution other than conquests of oil fields by war.9

Officials on both sides of the Pacific offered up platitudes about Japan’s financial and economic predicament under the freeze. Grew expected that Japan’s industrial, economic, and financial structure would be “very substantially weakened.” White agreed that Japan faced a state of disintegration, although not as rapidly as some believed. All U.S. observers thought the economy was declining steadily. Williams opined that “Japan’s economic structure cannot withstand the present strain very much longer”; without industrial materials, he declared, it could neither feed its people nor shore up wobbly transportation and utilities. While scoffing at Japanese pretensions of relief through trade with the yen bloc, Williams conceded only that “given a period of another ten years some measure of success might be achieved.” Meanwhile, if Japan elected to slash production, conserve, and drift it would become a “weakling” economically and militarily within twelve months, unable to resist U.S. political demands or to wage an efficient war for more than a few months. On 5 December 1941 U.S. Army G-2 Intelligence concluded that “the economic situation in Japan is slowly but surely becoming worse.” It lacked materials to support industry and the war in China let alone a major war. “In short,” G-2 concluded, “economically Japan is in perilous plight.”

U.S. officials tended toward an optimistic belief that, unless it chose war, Japan must soon cave in to U.S. diplomatic pressure. Maj. Gen. Sherman Miles, the head of G-2, wrote, for example, that “through the advantage the United States has gained through the embargo, Japan finds herself in a very poor bargaining position.” But Grew was a notable exception. The ambassador doubted “the theory put forward by many of our leading economists” that exhaustion of economic and financial resources would in short order bring about Japan’s military collapse. They were assuming continuation of a market economy. Japan, however, had “dramatically prosecuted” converting into a state-directed economy. That a war in the Far East could best be averted by sanctions or even a blockade, the ambassador warned, was not supported by facts he observed.10

Japanese leaders also spouted platitudes by adopting the terms “pauperization” and “impoverishment” in reference to the freeze impact. In July the Cabinet Planning Board declared that the empire “will shortly become impoverished” and must quickly decide on a course for self-preservation. The prevalent attitude held that long-term commercial and financial strangulation would result in “gradual pauperization.” Japan would die a beggar’s death. Ambassador Nomura saw no alternative to war, except, as one historian phrased it, “to endure great hardship and privation, utterly and completely.” The few moderates who warned of the price of war picked up the analogy. At a fateful conference of 26 November that committed Japan to the attack on Pearl Harbor, former prime minister Mitsumasa Yonai advised “that you be careful not to plunge into sudden pauperization in attempting to avoid gradual pauperization.”11

Why didn’t the United States government undertake a macroeconomic analysis of an isolated Japan in 1941? Lacking documentary evidence, one can only speculate. A possible inhibition was uncertainty about Japan’s economic condition just before the freeze. Tokyo ceased publishing most economic statistics after 1936. National budgets were vague as to expenditures, especially for the military, that were incurred in foreign exchange rather than yen. On the other hand, abundant pre-1937 data were on hand from published sources such as the Japan Year Book and reports of Japanese banks and trading houses as well as up-to-date import-export data from non-empire countries with which it traded. Japan’s industrial progress had been widely reported. Its published five-year plans had stated economic goals through the early 1940s. Thus ample information was available in the United States in 1941 to speculate rationally about the larger effects of a freeze, had anyone cared to do so.

Another possible inhibition might have been the unknown duration of the freezing policy. A short-term economic forecast of, say, a few months would have been of little utility because in the near term Japan could muddle through by dipping into stockpiles, skimping on maintenance, and deferring construction. Policies drafted in Washington at the time of the freezing order assumed partial resumption of trade after about two months, but the administration’s refusal to release frozen dollars or to engage in barter killed that prospect. Deadlocked diplomatic negotiations indicated the freeze might well continue beyond 1941.

A hypothetical American economist would also have had to guess at world political alignments after 1941. Presumably he would have assumed Japan would still be at war in China. Would the United States be fighting Germany, as widely anticipated? If so, would the United States and its allies continue the freeze or try to pacify Japan by easing it, perhaps even seeking to buy Japanese ships and other goods? The United States fighting in Europe could not have offered Japan strategic resources, especially not metals, but cotton and foodstuffs were plentiful. California petroleum was unavailable for an Atlantic war due to a lack of tankers, at least until new ship construction weighed in. In any case, Japan would certainly attempt to adjust to the freeze by extending its austerity programs, substituting local and empire materials wherever possible and shifting workers from processing foreign materials to domestic-sourced industries, perhaps even back to agriculture.

Whatever the reasons for inertia, there remains a tantalizing counterfactual question: What might a U.S. analyst have deduced about Japanese economic life if one had forged a comprehensive evaluation of a long-term freeze? Fortunately, a proxy can be found in the files of the National Archives, an elaborately detailed, secret 519-page study, “The Place of Foreign Trade in the Japanese Economy.” It was prepared during World War II, entirely from prewar knowledge, by economists of the U.S. Office of Intelligence Coordination and Liaison (OCL), a joint office of the Department of State and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) (fig. 2). The OSS, a wartime agency that organized and coordinated U.S. espionage and intelligence activities, headed by William J. Donovan, first launched the project in 1943. In 1943 and 1944 it assembled data on Japanese trade from both published and confidential sources and drew up preliminary analyses. The project was completed under the direction of Arthur B. Hersey, a thirty-five-year-old economist and statistician born in China but educated at Yale and Columbia Universities. Hersey, after postdoctoral work and a stint teaching mathematics, had joined the staff of the National Emergency Council, a New Deal agency that advised Roosevelt on labor and economic recovery issues. In 1935 he transferred to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors as a staff economist in the Division of Research and Statistics, performing quantitative studies of business expenditures and other domestic subjects. In 1943 the OSS recruited him into its Research and Analysis Branch for the study of Japanese foreign trade. In 1945 he returned to the Federal Reserve, which granted him time to direct completion of the study. (Afterward, he served as a senior economist and adviser in the Fed’s Division of International Finance until his retirement in 1972.)12 Although he completed his study in 1946 using some secret data from the prewar years that the Japanese provided U.S. occupation authorities, his analysis and conclusions about foreign trade were based on open sources for 1930 and 1936, and to a degree for 1938. Such information was available in Washington in 1941. The study, declassified in 1948–50, is a unique document that plausibly suggests how American economists might have quantified the deterioration of an economically isolated Japan, if Japan had not resorted to war and if the freeze had continued for a few years in the early 1940s.13

FIGURE 2 Cover OSS/State Department’s “The Place of Foreign Trade in the Japanese Economy”

Call no. HF3826.U5 1946, Library of Congress.

Most relevant are Hersey’s scenarios of Japanese standards of living in a hypothetical year “1950”—always enclosed in quotation marks—which envisioned a defeated Japan almost recovered from physical war damage but stripped of its colonies and conquests. (In 1943–44 he could not have foreseen the devastating firebombing attacks of 1945.) Japan in “1950” would not be able to pay for vital imports due to a weak economy, feeble exporting power, adverse “terms of trade” (relative international prices), and, possibly, harsh restrictions of a peace settlement. Although Hersey addressed a theoretical postwar date and a far different world political situation than that of the 1940s, he projected conditions strikingly similar to those facing Japan in 1941, and worsening if it had to endure years of the freeze without resorting to war.

Hersey expected the “1950” foreign trade of Japan to resemble that of the difficult 1930s. In the 1940s economists widely assumed that Depression-like conditions would reemerge in the world after a brief postwar boom. (U.S. troops in the Pacific sang, “Golden Gate in ’48, bread line in ’49.”) In both hypothetical eras, postwar “1950” and the frozen early 1940s, Japan would remain an overcrowded, resource-poor island nation that had to trade to maintain even a spartan standard of living, thus vulnerable to acute deprivation when trade was hobbled for any reason. The adversities of the 1940s would be due to isolation by potential enemies, and in “1950” to disadvantages in reopened world markets, but the Japanese people would suffer similar deprivation in both situations. Other American economists studying the data available in 1941 would in all likelihood have arrived at similar conclusions.

Hersey’s methodology was complex and often arcane. (The technical details are summarized in Appendix 2 of this book.) His key economic variable was Japanese importation of foreign materials consumed by the domestic economy, comprising two-thirds of total imports, which he labeled “retained imports.” (The other one-third was processed into finished goods that were reexported or, in some cases, offset by similar exports of different grades or stages of refinement.) Hersey grouped retained imports into eight categories, themselves aggregations of twenty detailed commodity groups. For simplification, retained imports are further condensed here into two broad categories: goods primarily consumed by households, and those primarily for industry, investment and military forces. Before 1941, 65 percent of retained imports had directly serviced the Japanese public’s standard of living: food and fertilizer, 35–40 percent, and materials for clothing and shelter (cotton, wool, wood pulp for rayon and paper, and lumber), 25–30 percent. The 35 percent of retained imports not directly supporting the standard of living included metals, chemicals, and fuels (25 percent) and manufactures, mainly machinery (10 percent). (Japanese consumers rarely had access to foreign manufactured goods after 1937.) The two simplified categories are admittedly rough. Oil, for example, supported civilian transportation and fishing as well as industry and the navy, while lumber was needed for factories and railroads as well as housing. Errors of aggregation, however, tend to balance out.14

For this narrative two other adjustments have been made to Hersey’s data: converting yen to dollars at the relevant exchange rates and recasting figures to a per capita basis to compensate for the effect of population growth, predicted at seven to eight million more people from 1941 to “1950.” Hersey did not attempt to quantify the entire domestic Japanese economy. He noted, in fact, that retained imports of about $1 billion per year in 1938–39 were relatively small versus national income of $6 to $7 billion, but retained imports were crucial in maintaining Japanese life above a primitive level that domestic resources could sustain alone.15

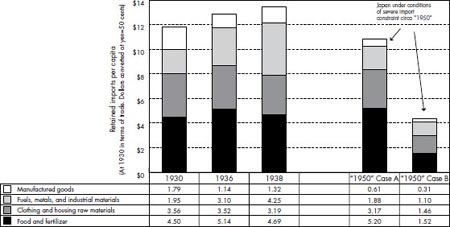

The OSS–State Department analysis posed two scenarios for “1950,” Case A and Case B (table 4). Case A assumed a standard of living forced back to the level of 1930, before Japan’s decade of extraordinary industrial growth. Hersey considered Case A generous. He thought the bountiful terms of trade of 1930—high silk price versus cheap agricultural imports, for example—were unlikely to recur after the war, especially as nylon crowded out raw silk. Case A envisioned Japan affording to buy approximately the same value of imports as those of a typical 1930s year (measured at constant prices; see Appendix 2). During that decade greater retained imports more than offset population growth, so that retained imports per person had grown from $11.80 to $13.45 per year in constant dollars. However, due to expected further population growth, a Case A postwar Japan with stagnant retained imports could afford at best $10.85 per capita, a reduction of about 15 percent from the 1930s average.

TABLE 4 Japan Proper Retained Imports, Actual 1930s, and Projections to “1950”a

a Millions of dollars converted from 1930 yen at yen=$.50

b Implied estimate of 1942 population for Case A and Case B.

Figures approximated due to rounding decimals.

OCL, “Place of Foreign Trade in the Japanese Economy,” vol. 1, pt. 1, tables I–19 to I–21.

Japan’s ability to feed itself had topped out in the 1930s. Nutrition had been maintained by a greater volume of retained imports. In “1950” a further increase in foreign food, fertilizer, and oil for fishing would be necessary to maintain the average diet at 1930 levels, about 2,250 calories per person per day. With export earnings lagging, non–food-related imports would necessarily be tightly restricted, with national priorities favoring essential materials for clothing, shelter, and infrastructure. “Luxury” consumer goods, such as food varieties and manufactures, would rank last, if at all. Hersey allowed for a slight moderation of the pinch on consumers by supposing Japan would increase the portion of retained imports destined for households from 65 to 70 percent. With scarce foreign exchange earnings mostly allotted to basic living, imports per capita of industrial materials and fuels would plummet to half the average prewar level, and imports of machinery and other manufactures even further.

Case A envisioned Japan maintaining frugal standards of decency in life’s essentials, its economy sluggish and lacking foreign resources for growth and renewed industrialization, with little prospect of improvement. The Japanese diet would be spartan: more wheat and coarse grains and starches (barley, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and oats), less of the beloved Japonica rice, and much less variety of fish, meat, sugar, fruits, and vegetables. Tobacco would be scarce and expensive. Men and women would wear inferior clothing, mostly spun staple rayon with perhaps some blending of cotton and wool. Leather shoes would be scarce. Housing for the rising population would necessitate imports of lumber and pulp, although local cement could substitute somewhat. Few if any private automobiles would be manufactured, and probably none imported. Output of traditional small housewares could be maintained, more or less, but not better goods, let alone modern appliances. Industries needing chemicals and fuels, and structural materials beyond maintenance needs would stagnate. In sum, Japan’s decade of strenuous national effort after 1930 would be nullified.16

For a speculation on the extreme grief of a freeze-hobbled Japan in the early 1940s, Case A is too optimistic, a “best case” because retained imports would have shriveled under the freeze even more than in the postwar austerity cases. But Hersey’s Case B posited a “1950” far more dismal than a frozen Japan in the 1940s (chart 20). Case B assumed export earnings so drastically collapsed that nourishment and health could no longer be sustained through importing, as it had been in prewar years. A horrendous collapse of commerce and extremely weak terms of trade based on the adverse price relationships of 1936 (see Appendix 2) would compress exports by 60 percent below the prewar average. A drastic shortage of foreign exchange would restrict retained imports per capita to one-third of an average 1930s year. Japanese life would be thrust back to nineteenth-century standards. Diet would shrivel to 1,800 calories per capita per day, 20 percent lower than in the 1930s, necessarily consisting of 83 percent cereals and starches. (In comparison, in the 1990s the daily per capita consumption in Japan was 2,898 calories, of which only 40 percent was from cereals and starches.17) Hersey imagined either “semi-starvation of the urban population” or “chronic malnutrition for the whole population,” depending on government food allocation policy.18 Imports for other needs would have to be slashed even more drastically. The standard of living, broadly measured, would fall 25 to 33 percent below Case A, itself below prewar standards.

CHART 20 Japan: Retained Imports per Capita, 1930s and “1950” Projections

OCL, “Place of Foreign Trade in the Japanese Economy,” vol. 1, pt. 1, tables I-19 to I-21. Converted to dollars per capita by author.

In Case B Japan’s meager exports would earn barely enough to finance imports of essentials for human survival. The nation would subsist by exporting rural goods: raw silk to a fading market, fish, exotic farm specialties, cottage wares, and handicrafts, all lagging in price compared with its former advanced manufactures. Eighty years of advantages hard won in world markets by skilled labor and management would be nullified, leaving almost no surplus to buy materials for trade-oriented factories. The export-led growth that had buoyed Japan since Meiji times would shift into reverse.

Workers would suffer horrifically in Case B. Factories deprived of foreign materials would go dark. Steel from local ore and scrap would barely maintain railroads, utilities, and the most essential processing industries. Imports of machinery and manufactures would sink by 70 to 80 percent. Cities would suffer massive unemployment, and in a great migration to the countryside, possibly ten million Japanese would return to the already overcrowded land. Rural population might swell to forty million, the same 50 percent of total population as in 1920 but much larger in absolute numbers.19 There they would find little relief. With overseas demand lost to synthetics, farm families dependent on raw silk for cash earnings would slide into poverty. No Japanese family would have found solace in Hersey’s remark that its purchasing power would sink “not necessarily lower than that in other Asiatic countries,” implying a standard of living at the level of China or India.20

Were Hersey’s calculations a valid analog for the fate of Japan under a multiyear dollar freeze after 1941? Cases A and B probably bracketed the agonies facing a nonbelligerent, financially frozen Japan in the early 1940s. A more likely outcome was a middle scenario proposed here, an interpolation to adjust for differing circumstances of the two hypothetical eras.

A relatively more favorable circumstance for Japan in 1942–43 would have been its unimpaired trade with the yen bloc—the colonies of Korea and Taiwan, Manchukuo, the Mandated Islands, occupied parts of China, French Indochina, and probably Thailand. In contrast, in “1950,” the former yen territories would be independent and its former members demanding hard currency for their goods. In the 1930s the yen bloc provided about 45 percent of all Japanese imports (29 percent from Korea and Formosa, 14 percent from Manchukuo, Kwantung, and North China, and 1 or 2 percent from Indochina and Thailand). It supplied most of Japan’s imported food, all of its rubber and tin, some iron ore and alloying metals, and some cotton, but only small quantities of fuels, ores, and metals and almost no manufactures. Yen bloc supplies were largely retained for consumption in Japan rather than processed for reexport. For example, the deliveries of Korea and Formosa typically consisted 70 percent of food and fertilizer. A frozen Japan in the 1940s would have continued its policy of paying them by delivering Japanese-produced articles such as cement, coal, nitrogen fertilizer, and machinery; by investing yen capital in pubic works and industries; and by transferring gold to Thailand and probably Indochina.

Hersey did not break out retained imports received from the yen bloc. If one assumes that Japan did not upgrade and reexport more than 10 percent of them in products such as refined flour and sugar or mixed fertilizers, Japan might reasonably have obtained 60 to 65 percent of its customary imports for consumers’ needs from the bloc. Yen bloc rice and cereals, supplementing domestic agriculture, would have been adequate, or nearly so, to maintain nutrition of Japan’s rising population at the 2,250 calories per person that prevailed in the late 1930s. (Hersey noted, however, that the climate had been unusually good in the last prewar years so that a regression to normal farm yields might squeeze food supplies.) On the other hand, the bloc could supply only 32 percent of the phosphate and almost none of the potash fertilizers normally imported by Japan. Sooner or later, perhaps after two years as U.S. vulnerability studies observed, slumping grain production in Japan would strain food supplies. Except for sugar from Formosa and the Marianas Islands the diet would be less varied than before the freeze and short of protein from a fishing fleet deprived of oil, especially for deep-sea fishing which was both the most productive and most fuel-dependent form of fishing.

The yen bloc could not have supplied Japan with other consumer needs. It had almost no wool for sale. China consumed its rather small cotton crop in its own textile mills. Except for scarce heavy-duty work clothes, the Japanese would wear rayon, not the durable long-strand variety from good foreign pulp, but short-staple spun rayon from local trees, woven into flimsy textiles well known to fall apart in Japan’s wet climate. (Silk would be available for blending, but not in quantities to help much.) Leather for shoes and boots would be unavailable; rubber from Indochina would substitute, at least for the lowers. Luxuries would be scarce, perhaps a bit of sugar and tobacco. Gasoline and diesel motor vehicles would almost disappear from Japanese roads.

On the other hand, the standard of living of a 1940s freeze era could have been even worse than supposed for “1950” due to two other circumstances. First, the economic drain of the war in China had already caused dire shortages and rationing, made worse by the freeze. (Logically the China war and a freeze went together; if Japan ended the war the United States would have relaxed or ended the freeze.) Second, the freezing orders rendered Japan’s gold production and gold reserves worthless internationally. Hersey assumed postwar gold and silver mining at only half the 1930s volume due to equipment shortages and loss of colonial mines, but after the war Japan could expect to freely sell its output for hard currency.

Hersey thought the “invisible” elements of Japan’s balance of payments would be negligible in “1950,” but the same would have been true in the frozen 1940s. The freeze halted hard-currency earnings from shipping; revenues could not have recovered much by “1950,” so soon after a war in which 80 percent of Japan’s merchant marine was sunk. The freeze also terminated earnings from Japan’s overseas investments that were seized by its enemies, a result not much different from the “1950” scenarios because the investments were not returned after the war. Similarly, outgoing interest payments on Japanese foreign loans ceased at the end of 1941, when blocked dollars in New York ran out, and postwar Japan could not have afforded to resume payments until long after “1950.” In neither era would Japan have had access to foreign loans, in the 1940s due to the freeze and afterward, Hersey thought, due to lack of creditworthiness. (He did not foresee postwar aid from the United States.) The Bank of Japan’s gold reserves in its vaults were still large in 1941 but useless during the freeze. Hersey imagined they might still be unavailable in “1950” because they would be sequestered by the Allied authorities for restitution or occupation costs. A small exception, “compassionate remittances” from overseas Japanese settlers, halted by the freeze, would help a bit in “1950.”21

The picture that emerges of the Japanese under a freeze, circa 1942–43, is of people with an adequate diet high in starches but deficient in other food groups, shabbily dressed as their wardrobes wore out, and suffering the effects of cold and damp. Transportation and utilities would be decaying. Depression-era unemployment would probably have returned to the cities, and extreme hard times to the villages. After a couple of years of embargo, Japan might have matched Case A in avoiding malnutrition, but with other aspects of life rolled back to primitive levels approaching those of Case B. While not as calamitous overall as Case B, a reduction of 35–40 percent of customary imports for consumption per person would have been a serious matter for Japan’s trade-dependent society. It would equate to a rollback of the Japanese standard of living of about 15 to 20 percent in broad terms. An apt comparison might have been to the most poverty-stricken families in the most miserable regions of the United States in the worst depths of the Great Depression, surviving but enduring lives of grim deprivation with little hope of relief.