U.S. international economic policy early in 1941 remained focused on conserving defense materials through the export licensing system, in some cases selling strategic exports only to the Western Hemisphere and the British Empire, a policy not specifically targeted at depriving Japan. Commodities that were plentiful were rarely restricted. Petroleum, other than aviation grades, for example, remained generously licensed for Japan.

During the summer of 1940 the newly established Economic Control Administration had rushed to develop and administer the export licensing program for conservation, too busy to consider applying economic power against potential enemies, which in any case was a task beyond its authority. But the impulse to scale up to offensive economic warfare was not long in coming. In September the administrator, Gen. Russell L. Maxwell, submitted planning issues to the Army Industrial College in Washington, D.C. The college operated an Economic Warfare Section to teach courses and “lay the groundwork” for economic warfare, and its commandant had anticipated Maxwell’s need. On 23 September he offered his staff as a nucleus of a national organization for economic war. Maxwell agreed that he needed such a staff, if only to collect economic information. Secretary of War Stimson, in concurrence, ordered transfer of the college’s Economic Warfare Section to the ECA effective 15 December.1 Once aboard, the college staff metamorphosed into the Planning Division, subdivided into three sections. Two dealt respectively with administration and with statistical information on commodities. The third, and most important for economic warfare, was the Projects Section to investigate foreign production, trade, and shipping and make “comprehensive plans for the coordination of economic power as an effective instrument of national policy.”2

A second push toward economic warfare emanated from the Advisory Commission of the Council of National Defense. On 27 November 1940 the civilian commission urged President Roosevelt to designate an agency that would stretch beyond conservation. It would deny resources to potential enemies by targeted controls on exports and shipping and preclusive buying of commodities from neutral countries. Germany and Japan, it was believed, were circumventing the British blockade by obtaining U.S. supplies via other countries. The Advisory Commission pointed out abnormally high Japanese purchases of fourteen commodities since licensing began in July, including oil products, ferrous and nonferrous metals and scrap, and phosphate fertilizer.3

The head of Maxwell’s Projects Section, Thomas Hewes, was a rather odd choice. A bright, fifty-three-year-old, Yale-educated attorney-politician, he had been active in Democratic party affairs since 1912 and on Connecticut state commissions. Although he had served brief stints as assistants to both the secretaries of State and the Treasury early in the New Deal, he had no obvious experience in trade control as an instrument of foreign policy. Given to writing flamboyant, courtlike proposals, he typified the “culture of opportunism” that was sweeping through Washington bureaucracies.4 Such men, newly appointed to new functions, strove to inflate the roles their agencies played into exciting new adventures. Hewes’s key aides were Harvard-educated analysts in their thirties, recruited from traditional agencies, each having a background suited to a niche in trade studies. Chandler Morse, an economist and former professor at Dartmouth College, had served twelve years with the Federal Reserve System in New York and Washington. His interests did include international trade (ultimately focusing on Africa), but his experience was in financial matters.5 Richard H. Sanger, an economic analyst with an interest in the Middle East, held a degree in business administration, a rare specialty in the bureaucracy of those days. He had floated between the Commerce Department’s foreign service and the staff of the Republican National Committee and had tried his hand at writing and reporting.6 Louis Serge Ballif, an accountant, had served six years with the Federal Trade Commission and, more recently, the Tariff Commission, where he studied production costs of European businesses. While cost accounting was a relevant skill, his main value to the Projects Section lay in his understanding of the need to bring together experts with knowledge of specific commodities.7 Hewes’s aides eagerly supported his grasping at opportunities to aggrandize the ECA’s role by moving from materials conservation into economic war of the broadest type. Neither they nor Hewes had any knowledge of Japan per se.

On 17 December 1940 Hewes drafted for General Maxwell a letter to Roosevelt recommending a policy of economic warfare. Because the U.S. and British navies controlled the seas and the United States was an essential market for most neutrals, he pointed out, America could bring to bear pressures amounting to “strangulation” of the Axis. Economic victory, he believed, was preferable to armed combat. Early in 1941 Hewes’s aide Chandler Morse advocated stern measures to “attack the enemy on a broad economic front” by export restrictions and interference with purchases anywhere in the world, enforced by an independent agency of “transcendent potency” to operate in parallel with the Army and Navy.8

The advocates of economic war took heart from Britain’s experience. In February 1941, during a visit home, Brig. Gen. Raymond E. Lee, the U.S. military attaché and head of U.S. Army intelligence in London, met with Maxwell’s senior staff and Dean Acheson. British leaders deemed economic warfare a military function, according to Lee. They believed the war’s outcome depended on it. The British had established a highest-level Ministry of Economic Warfare; not organizing it prewar had been a costly mistake, they believed. The U.S. “reward and punishment” idea for prodding neutral suppliers seemed pale in contrast. In late March, Noel Hall, joint head of the British Ministry who was visiting Washington, described his policies and procedures to the Projects Section and other officers of the ECA. As further elaborated by U.S. attachés’ reports, the British distinguished between “economic aspects of war” and “economic warfare.” Hall’s so-called Fourth Service was an offensive agency—more warfare and less economics. It was charged with damaging and destroying enemy economies by denial of shipping and preemption of foreign supplies. In fact, it used every means short of combat, but it coordinated with the armed forces, going so far as choosing economic targets for air attack and naval blockade.9 The muscular British precedent suited Maxwell, a professional soldier, and his eager team of neophytes.

The staff of the Projects Section was keen to prepare for economic war by investigating trade conditions of foreign countries, including Japan specifically, but lacked information and experience. General Maxwell had to ask the Tariff Commission for data on U.S. imports, a subject alien to his export controllers. A staff report, “The International Use of Economic Pressure as an Instrument of National Policy,” apparently added little despite an evocative title. Three later reports by the ECA’s Far Eastern Division addressing the effects of trade restriction on both Japan and the United States were of no significance to judge from later derogatory remarks about them.10

Back in November 1940 the Projects Section had come up with a grandiose idea: to educate itself on overseas production and trade by assembling commodity experts from other government agencies into teams to launch investigations in depth. In December Louis Ballif pointed out to Hewes that troves of data were available in the files and libraries of the Departments of Commerce and Agriculture, the Maritime Commission, and other bureaus. Ballif’s recent employer, the Tariff Commission, in particular employed personnel qualified for field investigations of international commodity trade. Ballif advocated assembling ad hoc committees of such experts to study and report. He envisioned hierarchies of country task forces, for example, a committee on Japan with subcommittees on its economy, trade, and finance. The president could authorize such activity under the Trade Agreements Act.11

Maxwell blessed Ballif’s idea. On 24 February 1941 Chandler Morse set in motion a series of interagency task forces by convening a steering committee of six midranking officers of the Departments of Commerce and Agriculture, the Bureau of Mines, the Tariff Commission, and the Export Control Administration itself. Later, the Forest Service and Federal Reserve were added to the group. The Projects Section also opted to exclude specialists from the private sector to “keep it as quiet as possible.” The proposed task forces would evaluate the impact on Japan of embargoing U.S. materials and denying it alternative sources of industrial, farm, and mineral products respectively. The Tariff Commission would assess the effects on American business, consumers, and labor of curtailing trade, including imports from Japan, a leap beyond the limitation of exports toward a possible termination of all trade. Morse assigned his deputy, Richard H. Sanger, to coordinate the work but decided he would personally select the commodities to be studied. Army Industrial College reports were available for some. Each team was granted flexibility to decide the details of its work, other than petty rules on statistical formatting and the color of report covers. Speed was paramount. Preliminary reports, sketchy if necessary, were to be submitted by the end of March.12

The ECA’s drive toward trade warfare received a boost from the Army and Navy—with qualifications. At the end of January 1941 U.S. and British military planning staffs met in Washington to confer on war plans. Their effort culminated in May with adoption of Plan Rainbow Five, the blueprint for Allied grand strategy over the next four years, famous for the “Germany first” doctrine of defeating the most powerful enemy while consigning a war against Japan to second priority. Adm. Harold R. Stark, the chief of naval operations, and Gen. George C. Marshall, army chief of staff, told Maxwell on 4 April that the combined U.S.-British strategy included economic pressure by “control of commodities at their source by diplomatic and financial measure” as well as actual attacks. The military conferees expected to exchange liaison officers to coordinate the work of the ECA with the British Ministry of Economic Warfare, aiming toward cooperative economic warfare plans against all the Axis powers. Maxwell had already proposed to form a U.S. Economic Warfare Committee on Far Eastern Trade consisting of experts he was recruiting from civilian agencies. On 17 March, Marshall and Stark agreed to assign representatives to his committee while sternly cautioning that economic warfare endeavors must flow from needs of their Joint Basic War Plans. Extreme secrecy must be maintained, they warned, especially because of inferences that the civilian study committees might wander into selecting actual targets of attack.13

The scope of the commodity task forces broadened rapidly from objective analytical surveys to recommendations for economic warfare policies to proposals for punitive actions against Japan. On 11 March 1941 Morse recommended to C. K. Moser, chairman of the ECA’s Far East Research Unit, that he focus on bottlenecks in Japanese industry that could be exploited to apply significant economic pressure. (He added, far beyond his authority, that the information might prove useful for targeting air attacks.) On the fifteenth he directed that the team studies were to be uniformly titled “The Economic Vulnerability of Japan in [name of a commodity].” The reports, ultimately on about fifty commodities, came to be known as the Vulnerability Studies.14 Four days later the teams were instructed to quantify the injuries to Japan if the United States preclusively bought up raw materials from neutral countries to keep them from Japan’s grasp—not just for U.S. defense needs—and to comment on the impacts on those neutrals and on world prices and production. They were also to suggest other means of isolating Japan and to assess the difficulties it would face in obtaining needed materials in 1941, an indication that early sanctions against Japan were anticipated by the ECA planners. Since the Lend-Lease Act and combined military planning had committed the United States to global cooperation with Britain, the studies were further broadened to include parallel embargoes, shipping denials, and preclusive purchasing by the British Empire. The goal of the ECA was no longer merely conserving for national defense. It was intent on denying commodities to Japan and even penalizing its economy by cutting U.S. imports of its products. On 3 April, Hewes, the leader of the program, reported to Maxwell that the Projects Section’s highest priorities were the team investigations for “economic warfare,” as they were bluntly called.15

Hewes’s section assembled sixty government analysts into thirteen committees to study groups of commodities, about half minerals and half vegetable and animal products.16 A committee typically had four to six members drawn from three or four agencies. The largest number, including seven committee chairmen, were former colleagues of Louis Ballif at the U.S. Tariff Commission, an unusual entity for leadership because it mainly kept an eye on U.S. imports, whereas most teams were investigating exports. The United States imported few strategic commodities and those it did, such as tin and rubber, entered duty-free and were of no concern to the Tariff Commission; however, the commission’s staff had studied foreign industries for resetting tariff rates from time to time, for example, to adjust for dumping. The second largest number of analysts, and three team chairmen, came from the Commerce Department, the agency that collected statistics on both exports and imports and posted commercial attachés in a few countries, including Japan, to report on business conditions. The vulnerability teams, to judge from their reports, consulted published aggregated data, not confidential information submitted to Commerce by individual American companies. The Department of Agriculture and the Bureau of Mines contributed experts to a few panels. Only one ECA employee served, and one from the Federal Reserve, both on iron and steel. Having no experts from industry, several teams advanced naïve conclusions about Japan. The State and Treasury Departments did not participate at all. Either the ECA wished to plot an independent course, or those departments responsible for foreign economic and financial policy wished to avoid participation with the ad hoc effort of an untested emergency agency. In any case, nearly all the vulnerability analysts were seized by that culture of opportunism affecting other bureaucracies in 1940–41. They enthusiastically strived to influence policy by recommending economic war against Japan by means of embargoes.

By late March 1941 preliminary studies began flowing in, some just a few pages long, some a hundred or more. Because of broad interest, mimeographed copies were widely distributed throughout the government. (In a comical misunderstanding Lt. Col. J. S. Bates of the Planning Section locked reports in his desk because they were marked “confidential,” so the crucial studies of steel, oil, and chemicals did not reach Maxwell for two to four weeks.) Quality and value were far from uniform; the Commerce Department offered to reorganize and conform the statistical data more professionally. Since most committees recommended halting export licenses for Japan immediately, for the sake of urgency Hewes forwarded their reports without a personal review. By 11 April nearly all were ready for delivery to military and civilian agencies.17

The end point of the vulnerability studies and related efforts of the ECA’s Projects Section was a two-volume report titled “A Coordinated Plan of Economic Action in Relation to Japan,” rushed to completion on 1 May 1941. It included the vulnerability studies, other recent investigations of Japanese vulnerabilities in food, shipping, and machinery, and generalized studies of the Japanese government and economy by the ECA’s Far Eastern Committee. Maxwell delivered the report to Stark and Marshall, their intelligence chiefs, most cabinet secretaries, and in mid-May to Vice President Henry Wallace, albeit with a disclaimer that he had not thoroughly reviewed it nor granted final approval.18 Hewes enthused that he had submitted a coordinated, integrated, written plan of action that “first exposes the economic vulnerabilities of Japan and then lays out in one, two, three order the exact steps by which to carry through an aggressive American effort to isolate and strangle her” in order “to endeavor to wrench Japan from the Axis” by an “enduring an all-out campaign to isolate her economically” if diplomacy failed. The U.S. government must deploy “all our economic potency” against Japan,” he argued, “driving straight at the heart of the enemy’s internal living and his fighting power.” To accomplish the grand objective the United States must immediately adopt an economic warfare policy under a single administrator charged with preparing detailed plans of action. Maxwell, Hewes, and their minions obviously expected the mantle to fall on their shoulders.19

The vulnerability studies of April 1941constituted the most detailed effort the United States government ever undertook to evaluate the impact on Japan of a near-total curtailment of trade. The chosen commodities, nominated by a midlevel official, included most of the major articles of trade between the two countries, several minor ones of military value, some that the United States did not export or even produce, and the principal articles that it imported from Japan. For most of the commodities the interagency teams recommended complete embargos. For only a few did they propose no action, or omit recommendations altogether. They also commented on the burdens facing the U.S. economy from eliminating trade in each commodity, which they believed to be minor in all cases. What emerged was a show of determination of the export control bureaucracy to deny Japan almost all commerce with the United States and with the British Empire and other powers friendly to the Allies, a program nowhere authorized by the laws and orders that empowered the ECA.

Despite his staff’s enthusiasm Maxwell did not commission a grand summary report of the impact of commercial isolation on the entire Japanese economy. Nevertheless, the vulnerability studies merit serious historical consideration. They are the main contemporary evidence of U.S. government judgments of the specific difficulties Japan would face, commodity by commodity, if and when trade ended. (For a reconstruction of what U.S. authorities might have concluded had they undertaken a comprehensive study in 1941, see chapter 18.)

Although the vulnerability studies were not presented in a particular order, they are summarized here in four groupings:

1.Commodities of strategic importance that Japan bought from the United States or its allies, or from U.S. companies operating in Latin America, described in the remainder of this chapter. Embargoes would primarily harm the Japanese army and navy. Of course, metals, oil, and some others were also important for Japan’s civilian economy but they are fairly labeled as strategic because Japan most desired them for war.

2.Commodities primarily for civilian needs of food, clothing, shelter, and other amenities of life that Japan obtained largely from the United States and its allies (chapter 4). Embargoes would punish the population, an extreme manifestation of total economic warfare.

3.Commodities that America imported from Japan (chapters 3, 4, and 11). A few were desirable for the U.S. economy although not crucial. None were deemed vital for U.S. military needs. Import embargoes were recommended for silk and several other articles, to deny Japan foreign exchange and in a few cases to disrupt internal Japanese economic life.

4.Crude and refined petroleum, by far the most sensitive and critical of commodities (chapter 13) (charts 10, 11, and 12).

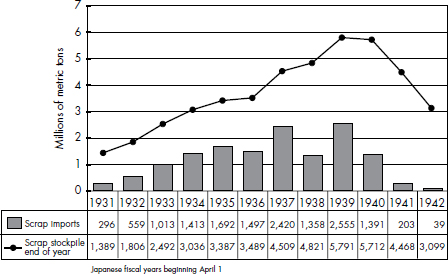

Japan’s vulnerability in ferrous raw materials had not changed since the U.S. embargo decision of late 1940 (chapter 7). Exports to Japan had previously averaged $45 million per year. Analysts surmised that the complete halt of U.S. scrap metal sales, and to a lesser extent restriction of pig iron from India to one-third of 1938 levels, posed serious problems for Japanese open hearth and electric furnace steel production (chart 13). They believed that in 1941 the steel mills were drawing down “fairly large” stockpiles of scrap previously imported. Yen-bloc iron ores were considered low grade and uneconomic, but high-grade iron ore still flowed in from Japanese-owned mines in British Malaya and new U.S.-owned mines in the Philippines, Japan being their only customer. Japan lacked blast furnace capacity to process more ore, however, and could not complete new capacity for two or three years. The study team felt it was desirable to cut off the ores from U.S. and Allied colonies to impede steel output. But how? The United States and Britain could not buy the huge ore tonnages mined in the Far East due to lack of shipping. Storage at the mines was impractical. Shutting them would harm the colonial economies. With an air of resignation, the analysts recommended pressuring the Philippine and Malayan authorities to halt production, cushioned by grants of money to compensate labor and non-Japanese owners. They glumly hoped that Japanese ore stocks were “not so great as to render futile efforts to restrict further shipments of such materials to Japan.”20

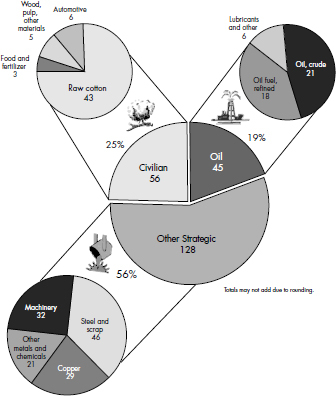

CHART 10 U.S. Exports to Japan, 1939 (in Millions of Dollars)

Department of Commerce, Foreign Commerce and Navigation of the United States, 1940–42.

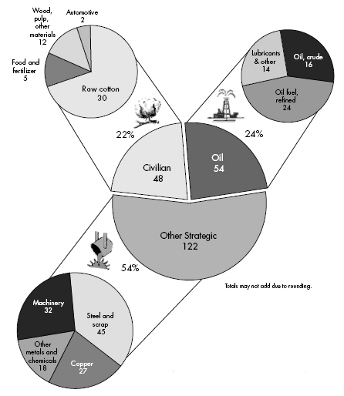

CHART 11 U.S. Exports to Japan, 1940 (in Millions of Dollars)

Department of Commerce, Foreign Commerce and Navigation of the United States, 1940–42.

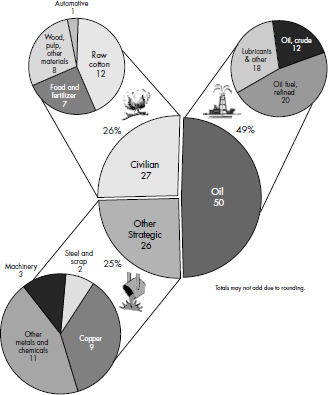

CHART 12 U.S. Exports to Japan, 1941 (in Millions of Dollars)

Department of Commerce, Foreign Commerce and Navigation of the United States, 1940–42.

CHART 13 Japan’s Scrap Iron and Steel Imports and Stockpile, 1931–1942

USSBS, Coal and Metals in Japan’s War Economy, appendix Table 8.

Copper was a necessity for modern war: wire and cable for electrical circuitry of ships and planes, cartridges and artillery shells of brass alloys, and nonrusting bronze and brass fittings for navies and air forces. Japan’s civil economy also required copper for electrical transmission, and steam and water tubes for factories and transportation. Before the First World War Japan had mined copper enough for itself while exporting 60 percent of its production. In 1917 production accelerated to 122,000 metric tons, making it briefly the world’s second largest producer (after the United States). With a postwar price collapse and return of competition, exports dwindled. As Japan pursued an ambitious electrification program, by 1926 it was a net importer. It bought Latin American semirefined copper, concentrated ore from the Philippine Islands, and U.S. scrap. By 1937 Japan had to import half its requirements. Despite a large smelter capacity estimated at 130,000 tons of metal, in 1939 U.S. shipments of refined copper ingots and shapes soared to 125,000 tons (and another 116,000 tons in 1940 in spite of licensing requirements), plus some scrap and finished goods. Next came a scramble in January 1941 before an announced termination of exports, effective 3 February, due to shortages in the United States. Altogether Japan obtained about 80 percent of its copper from the United States. Copper constituted 12 percent of Japan’s U.S. purchases in those years, at a cost of $25 to $28 million per year (ranking third behind oil and iron). It bought lesser quantities from U.S.-controlled companies in Chile and Peru; a plan to buy concentrated ore from several other countries did not work out, except for small quantities from the Philippines. By 1941 the United States was invoking contractual rights to demand cancellation of exports from Chile and diversion to the United States, and was buying up Peruvian output.

The vulnerability analysts had no information on the split of consumption, military versus civilian. Japan’s shift from importing wire and cable to buying crude and scrap inferred a trend toward war uses, as well as conserving foreign exchange by refining at home. The copper team recommended continuing the ban on export licenses, persuading South American countries to halt all sales to Japan, and possibly buying up Philippine ores. (Britain absorbed the output of Canada, Australia, and southern Africa.) Meanwhile, since war operations in China did not seem to consume much copper for artillery shells or replacing lost ships and planes, the analysts were certain that Japan had been stockpiling imported copper in fear of U.S. controls. In fact, the stockpile and yenbloc production proved adequate well into World War II.21

Vulnerability analysts examined exports of several industrial commodities of small dollar value viewed as potential bottlenecks for Japanese war industries. All were abundant in the United States and its possessions, and in some cases exported, so the embargoes they recommended would constitute a direct form of economic war rather than conservation:

•Abrasives. Japanese industry consumed silicon carbide and other synthetic abrasives for metal grinding by machine tools. In the 1930s its factories migrated from inferior natural emery to artificial abrasives produced in electric furnaces, but capacity limits required importing from the United States and Europe. In 1940 America supplied $1.5 million worth, five times the 1938 amount, indicating Japanese stockpiling. Although production in the United States and Canada was plentiful, the analysts recommended embargoes by both countries.22

•Carbon black. The United States was practically the only international supplier of carbon black, a high-grade sootlike residue of oil refining, for compounding with rubber in the manufacture of long-lived vehicle tires resistant to abrasion. Japan had few private automobiles but it manufactured tires for bicycles and, more importantly, for military trucks and planes and mobile industrial equipment. In the late 1930s Japan imported an average of thirty-seven million pounds of American carbon black annually, 2 percent of U.S. output. Although worth only half a million dollars, the analysts believed Japan had no other source and recommended an embargo to “seriously handicap” tire production.23

•Abaca. Manila hemp, stronger and more durable than other fibers, was the preferred cordage material for ropes and nets of naval, merchant, and fishing vessels. Philippines farmers were virtually the only growers. Japan bought fifty thousand tons of abaca per year, 60 percent of its cordage needs, from the islands. In April 1941 the Philippines came under the U.S. export licensing system. A vulnerability study recommended an embargo, albeit at serious cost to growers because preclusive buying was impractical. Nations harvesting other tropical cordage fibers were to be coaxed to follow suit. Japan would suffer “marked inconvenience.”24

•Fluorspar. Aluminum exports to Japan had been halted by the U.S. moral embargo at the end of 1939, an ineffective sanction because Japan had expanded metal production several fold (chapters 5 and 10). The vulnerability analysts were impressed, however, by the “very great significance” of fluorspar, a calcium fluoride mineral utilized in smelting aluminum and a potential bottleneck for Japan. In the Bayer process, the only practical refining method, alumina (aluminum oxide refined from bauxite ore) was dissolved in a bath of cryolite (sodium aluminum fluoride) in large electrolytic cells. Molten aluminum was precipitated by passing electric current through the cells. The world supply of natural cryolite came from a single mine in the Danish colony of Greenland. Japan normally imported 1,300 tons of cryolite per year but in 1939 bought a precautionary 6,147 tons, still inadequate for its soaring aluminum industry in the analysts’ opinion. In 1940 the Nazi occupation of Denmark cut off the source. Japan switched to synthetic cryolite manufactured from high-grade fluorspar. Therein lay an opportunity to hobble its aluminum output. Japan controlled only low-grade ores, in Korea and Manchuria. (Low-grade fluorspar was added as a flux in steel furnaces; although empire supplies were thought to be sufficient for Japan’s 15,000-ton demand, the study did not comment on a possible steel bottleneck.) The United States mined 30 percent of the world’s fluorspar of cryolite grade, and Germany mined about the same. When the war isolated Germany, Japan snapped up the small outputs of South Africa and Mexico. The vulnerability analysts enthused that a U.S. embargo, in conjunction with friendly countries, presented “a real opportunity to cripple the Japanese aluminum industry.” The clever notion failed, however. After fluorspar exports ended, Japan’s aluminum expansion continued unhindered by the imagined fluorspar bottleneck.25

•Organic solvents. After four years of war Japan was known to be a large producer of explosives. The vulnerability analysts reviewed U.S. exports of explosives raw materials that were derived from petroleum refining. Methanol was a feedstock for TNT (trinitrotoluene), and acetone for cordite (and, along with butanol, both were widely used for lacquers, resins, and cellulose plastics). The United States produced nearly two billion pounds of these organic chemicals annually, and exported globally. Japan’s small petrochemical industry was believed to lack adequate capacity. Japan purchased from the United States annually more than thirty million pounds of organic alcohols and solvents, and prior to 1939 it imported methanol from Germany. The vulnerability analysts recommended embargo of all three, including butanol in order to divert Japanese refineries’ capacity away from the explosives feedstocks.26

•Petroleum coke. Petroleum coke was a solid “bottom of the barrel” residue of oil refining. The purest grades were pressed into carbon electrodes for aluminum refinery cells and for steel electric furnaces. Low grades were burned as cheap fuel. From 1938 to 1940 Japan imported about $1 million of high-value U.S. “pet coke” annually. Nevertheless, because Japan’s refineries could produce it as long as they got crude oil, the vulnerability analysts opined that cutting Japan off would be “hardly worth while” unless part of a total petroleum embargo.27

The vulnerability studies recommended severing Japan from strategic commodities that the United States did not export by urging the British Commonwealth and other Allies to embargo them and by joint preclusive buying of neutral production.

•Bauxite. American hardliners had been frustrated by their inability to deprive Japan of aluminum. The U.S. moral embargo and the unavailability of European metal meant little to Japan; with ample power from hydroelectric dams and thermal coal plants, local production surged ahead. The self-sufficiency in smelting was so evident that the ECA did not bother to commission a vulnerability study of aluminum metal. Japan, however, imported 100 percent of its bauxite, the common commercial ore that contained about 25 percent aluminum. When Japan began to produce aluminum in the mid-1930s it purchased 10,000 to 15,000 tons of bauxite annually from India, Malaya, and Greece because the Netherlands East Indies, the largest regional producer, sold its output to Germany. Mines on three Japanese mandated islands in the Pacific yielded some bauxite, of which little was known, but experiments in Manchuria to process low-grade aluminous shales were correctly suspected as technological dead ends. In 1939, with Germany isolated, Japan stepped in to purchase an astonishing 168,000 tons from the Indies. This indicated to the vulnerability analysts that it was procuring “a large accumulation (possibly a two years’ supply) of bauxite over and above the requirements.” The studies reckoned that preclusive buying of East Asian bauxite was impossible because of lack of shipping for the bulky ore. (The United States itself relied on imported ore from British and Dutch Guiana.) Japan would be “seriously crippled in her efforts to make aluminum for airplanes” only if the bauxite of British Asian colonies and especially the Dutch Indies were cut off, and then only after two years, the analysts gloomily concluded.28

•Ferroalloys. Manganese was the most essential ferroalloy for common grades of steel. Adding 14 pounds of it contained in ferromanganese, an iron-manganese alloy, to a ton of molten steel scavenged sulfur impurities to yield stronger steel amenable to heat treatment. The analysts estimated Japan needed 90,000 to120,000 tons of high-grade manganese ore per year for steel making and even larger tonnages for chemicals and furnace refractories. Empire production, 66,000 tons in 1936, was increasing. Nevertheless, from 1935 to 1939 Japan imported an average of 210,000 tons of ore, largely from India supplemented by mines of British Malaya and from 1939 the Philippines. The purchasing was far in excess of needs, indicating massive stockpiling. The United States depended totally on imports of manganese, and feared that its main supplier, the Soviet Union, might soon be cut off. It was trying, along with Britain, to contract for the ores of all accessible countries. The vulnerability analysts inferred that Allied buying was pinching Japan because it accepted ores of less than the 50 percent manganese content demanded by American steel companies. They recommended pressure by the United States and Britain and their Asiatic dominions and colonies to sell all to them and none to Japan. In their rather extreme opinion, the Allies “would be justified in using any available measures to prevent manganese ore being exported to Japan from any source of supply, even if these two countries themselves did not need all the ore which is obtainable anywhere.”

Chromium was the key ingredient of the stainless steels essential for navies. Japan appeared to be self-sufficient in manufacture of ferrochrome. Its mines fulfilled its demand for thirty-nine thousand tons of chromite (chromium ore), except in 1939, when it imported some from the Philippines. Yet vulnerability studies were prepared on the hypothetical grounds that the United States and Britain needed Pacific basin ores that Japan might buy. The analysts worried that Japan might seek to control the outputs of the Philippines and of New Caledonia, a French island colony governed by De Gaulle’s Free French. Both sources were of rising importance to the United States, which had no chromite deposits. The country ought to acquire all their production, the analysts advised.

Tungsten was a critical ingredient of extraordinarily tough tool steels. Unusually, the yen bloc produced a surplus. Japan consumed two thousand tons per year of 60 percent–grade tungsten oxide concentrated ore from Korea and another two thousand tons procured “in one way or another” from unoccupied China, the largest world producer, despite a U.S. government contract to buy all the output of Nationalist China. Not much could be done to inconvenience Japan, except to continue the embargo of pure U.S. tungsten metal and preclusively buying British Burma’s mine output.29

The United States was the world’s dominant supplier of molybdenum for alloying tough steels. Exports to Japan had ceased under the moral embargo of December 1939 (chapter 6). The studies recommended formalizing it by executive order.30

Nickel was an indispensable strategic metal for armor, for stainless and alloy steels, and for plating ordinary steel. Oddly, it was not a subject of a vulnerability study, even though the Japanese Empire had no internal sources. Japan relied largely on Canadian nickel and, in part, on ore from French New Caledonia. The key world supplier, International Nickel Company of Canada (Inco) in which U.S. investors held a large stake, was booked up with deliveries to the United States and England. Presumably nickel was omitted from the vulnerability agenda because Inco was not supplying Japan.

•Asbestos. Asbestos fiber more than three-eighths of an inch long was a strategic material used to line brakes and clutches and to insulate and fireproof ships and buildings. (Short fibers, not strategic, were mixed into cement.) Neither the United States nor Japan mined any asbestos. Canada, the top producer, along with South Africa and the Soviet Union, supplied the world. There was no shortage in 1941. Japan had stopped buying U.S.-manufactured asbestos sheet, which was soon embargoed in any case. Since the late 1930s, however, its imports of long-fiber asbestos from Canada had risen sharply, an indicator of stockpiling. The “quite easy” solution for economic war was to induce Canada to embargo sales.31

•Exotic strategic specialties. War industries consumed certain articles of high value, measured in pounds, not tons, and found in only a few locations. Preemptive buying of most was feasible, and recommended by the analysts in most cases, along with diversions of British Empire output. Brazil was the indispensable source of three such commodities. Perfect quartz crystals, “highly strategic” for their piezo-electric qualities in radios and instrumentation, were still reaching Germany, and Japanese buying had soared. The studies urged that a U.S. agency in Rio buy the crystals direct from the mines, avoiding shady middlemen.32 Sheet mica, a rare transparent variety of a common mineral, was used in radio condensers and tubes, gauge glasses, and other technical equipment. India, the larger of the two producers, had halted sales to Japan, but in Brazil Japanese traders were buying recklessly at any price. The proposed solution was preemptive U.S. buying.33 Industrial diamonds were essential for metalworking drills, saws and dies for defense work, and rock drilling. Output was tightly controlled in British Africa, and the Belgian Congo under British supervision, which together mined 95 percent of the world’s diamonds. None were reaching Japan for its need of forty thousand carats per year for war production. But Brazil, the only neutral source, was infested with smugglers. Again, the answer was preclusive buying.34 Natural graphite flakes and lumps were fashioned into crucibles and retorts for defense plants. Japan had no deposits. The British had halted sales from Ceylon in January 1941 at U.S. request and were blockading Vichy French Madagascar, actions sufficient to pinch Japan.35

The vulnerability analysts, rather unusually, advised against embargoes of two other minor commodities. Germany had been the main supplier of high-grade optical glass for periscopes, gun sights, camera lenses, and the like, but as trade with Germany was already reduced, no action was proposed. Nor was an embargo of kapok from the Dutch East Indies, for flotation life preservers, necessary because substitutes were easily available.36

Surprisingly, a few other important strategic commodities already under U.S. licensing did not merit ECA studies. Japanese deficiencies in such materials were briefly considered in a State Department report of 27 May 1941. Zinc was vital for galvanized steel, brass, and complex castings, and lead for ammunition and gasoline refining. The yen bloc was 60 percent self-sufficient in zinc but only 20 percent in lead. Japan imported both metals from dollar-area countries—Canada, Mexico, and Peru—and some from Australia, at a cost of $5 million annually. As for tin, a $10 million requirement for solder, brass, and canning sheet, the yen bloc was one-third self-sufficient. Sources friendly to the United States, namely, Malaya, the Dutch Indies, and Bolivia, were logical candidates for preclusive buying.37

From a policy point of view the embargoes of strategic resources advocated by the vulnerability study teams were of two broad categories. First, the materials needed for U.S. rearmament and in short supply in the United States, whether actual or threatened, had been restricted from sale to Japan by the spring of 1941. The recommended embargoes, therefore, did not really amount to waging economic war. On the other hand, the embargoes advocated for materials in ample supply, even if military in their end-uses, amounted to a limited economic war—limited because the intention was to hamper military aggression, not to penalize the Japanese economy and people. But the vulnerability project went far beyond advocating embargoes of strategic materials. They also pressed to embargo goods essential for maintaining the life, health, and standard of living of the Japanese people, the ultimate U.S. move to a full economic war.