During the summer of 1941 the U.S. government reorganized its creaky, conflicted “economic defense” agencies by injecting a guiding authority, the Economic Defense Board (EDB), chaired by Vice President Henry A. Wallace. President Roosevelt established the board by executive order on 30 July, charging it with the oversight and coordination of all economic defense functions. He named as its members the secretaries of the State, Treasury, War, Navy, Agriculture, Commerce, and Justice Departments. Presumably FDR thought only the vice president had the independent stature to force cooperation among the fractious departments. In the international sphere (only a part of the EDB’s responsibilities) economic defense included trade, allocation of imported materials, preclusive buying, and shipping, with tasks including estimates of materials to support friendly neutrals and serving as “a central clearing service” for trade regulation. Another committee chaired by Wallace recommended consolidating the work of the ECA (renamed the Office of Export Control) with the State Department’s Division of Controls, and placing the function under EDB guidance, which Roosevelt ordered on 15 September.1 The ECA, established in July 1940 as a military function, was now a civilian institution; General Maxwell, cut off from his pipeline to the White House, was transferred to other duties.2 Acheson lost his perch supervising the Division of Controls yet retained a far more potent role. As de facto chief of the FFCC he held Japan’s international purse strings, enabling him to undermine resumption of trade with Japan should the EDB decide to advocate any.

Wallace felt that the “international crisis requires a determined intensification of our policy of preventing shipments to Axis-dominated countries.”3 Nevertheless, he showed interest in easing a bit the standstill of trade with Japan at a meeting on 19 August with Col. Charles McKnight, new head of the ever-hopeful ECA Projects Section (Thomas Hewes having departed) and his assertive deputy Chandler Morse. In their briefing titled “The Economic Orientation of the Far-Eastern Crisis, July–August 1941” they seemed unaware of the severity of the financial freeze, which had already halted all trade. In a rehash of the ECA’s Coordinated Plan of May 1941 they recommended stepwise acceleration of sanctions and pressures on Japan: specifically, a formal embargo of all trade, including oil (a step already accomplished de facto by the FFCC’s denial of funds) but with some relief if Japan offered tin, manganese, rubber, and silk, perhaps in exchange for oil within the 1935–36 quota. Wallace concurred in general provided the ideas were not likely to provoke a war.4

The Economic Defense Board was also charged with oversight of financial warfare activities, including controls of foreign exchange, investments, loans, and foreign-controlled assets including frozen funds. This made the board an operating as well as planning agency.5 The authority of Acheson’s FFCC was thus rendered subject to challenge if the EDB cared to recommend a moderation of the freeze. By coincidence, Japan at that time presented to the vice president a remarkable plan to override the iron-bound dollar freeze.

The Japanese government concocted an audacious plan to obtain oil and other resources by end-running the financial freeze. Stranded with unredeemable gold and dollars, denied release of funds for petty oil cargoes, barred from earning spendable dollars by exporting, and prodded by U.S. sleuths to surrender vestigial hidden sums, Japan contrived a plan to exchange over $100 million of commodities by the oldest of human exchange devices: barter.

In mid-August 1941, as it became clear that the freeze was unbreakable, Minister Counselor Sadao Iguchi suggested that Japan would happily resume some exports if it could buy U.S. commodities with the proceeds, in essence via a semibarter system. On the fifteenth Acheson squelched the idea, at least temporarily, by telling Iguchi that raw silk, Japan’s only significant export to the United States, was of no importance. The United States wanted only vital defense materials. When Iguchi asked for examples Acheson changed the subject.6 Six days later Japan launched a mission to appeal to higher authorities, over Acheson’s head, on the wishful presumption that barter trade was immune from the money freeze.

The Japanese chose a curious spokesman for their last-ditch effort: Raoul E. Desvernine, a New York corporate and banking attorney, president of the Crucible Steel Company of America, and disgraced Democratic party activist. Desvernine had earned Japan’s gratitude in the late 1930s by his efforts to help the Manchuria Industrial Development Corporation, “Mangyo,” a Japanese-owned business syndicate. Yoshisuke Ayukawa, the president of Mangyo, was promoting a five-year plan of industrial development in Manchukuo but had been hobbled by Tokyo’s refusal to allocate dollars to buy steel and machine tools. Hoping that U.S. firms would supply him on credit, Ayukawa approached Crucible, the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, and the United States Steel Corporation through a middleman to buy $15 million of steel, to be financed with five-year loans from National City Bank and three other New York banks. Desvernine expressed “strong interest” in the project, but the State Department, at that time terminating the 1911 commercial treaty with Japan, frowned on investment in Manchukuo. Nothing came of the deal.7

In August 1941 the Japanese engaged Desvernine to propose an extraordinary swap of raw silk for oil and other U.S. commodities. On 21 August he paid a visit to Cordell Hull, accompanied by Jouett Shouse, a Washington legal associate. The next day the two attorneys “talked the matter over” with Vice President Henry A. Wallace in his capacity as chairman of the EDB. Joining them was Charles B. Henderson, chairman of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which had jurisdiction over the Defense Supplies Corporation, an agency that supervised stockpiling of strategic materials. Wallace asked for “the exact proposal” in writing.8 Desvernine thereupon resigned from his post at Crucible Steel and set to work for the next two weeks drafting a proposal, assisted by Tsutomo Nishiyama, the Japanese embassy’s experienced commercial attaché (and in the 1950s Japan’s ambassador to India), and stayed in touch with Tokyo about the project.

Japan’s selection of Raoul Desvernine as emissary was a bizarre if not suicidal choice, suggesting a political tone-deafness. Early in the New Deal, Desvernine had been vehemently anti-Roosevelt. In 1934 he cofounded the American Liberty League, a right-wing propaganda association, to mobilize businessmen and lawyers to defeat FDR’s second-term reelection bid in 1936. Desvernine’s book, Democratic Despotism (still offered in some college curricula), accused the administration of unconstitutionally engorging its power and forcing the country down the roads to fascism, nazism, and communism. He likened a New Deal logo to the swastika and the hammer and sickle. The book vented special vitriol on Henry Wallace, then secretary of agriculture, as a “mystic prophet” who regarded capitalists as an “enemy class [that] is being, as Stalin would vulgarly express it, ‘liquidated.’” Although the Liberty League closed up shop after Roosevelt’s landslide reelection, and in 1941 Desvernine supported defense preparations, it is hard to imagine him as persona grata to Wallace, a left-leaning architect of the New Deal, or to Cordell Hull, who fumed with moral outrage over Japanese aggression.9

American policy makers had toyed with notions of barter trade while designing the freeze rules against Japan in late July. Dean Acheson may have been briefed on British practices by Noel Hall of the Ministry of Economic Warfare. The 30 July memorandum from the Interdepartmental Policy Committee to Welles on freeze procedures had included a suggestion that, after a few months, exports and imports of certain products might proceed under a barter-like arrangement. U.S. importers might be licensed to pay, most likely for raw silk, into a special bank account in favor of Japan. Japanese importing firms would be licensed to spend the dollars for U.S. goods that might be licensed for export, perhaps cotton. The barter idea survived, less specifically, in Welles’s memo, which FDR okayed the next day.10

Bilateral barter trade was a viable mechanism when two countries desired each others’ products, the normal case for the United States and Japan. In modern barter, the dates and values of cargoes never precisely matched, so bank clearing accounts were necessary. During the Depression many countries had enacted laws to channel trade payments through clearing accounts, usable only for reciprocal purchases, most famously the system installed by Hjalmar Schacht, president of the German central bank before and during the Nazi era. Germany was the premier market for Eastern Europe’s agricultural products, but its finances were too weak to sustain a freely convertible reichsmark. Under Schacht’s scheme, German importers of grain from Hungary, for example, paid reichsmarks into a special clearing account. The exporter could buy German goods or, more likely, sell the money only to another Hungarian firm for buying, say, German machinery. Schacht stimulated or discouraged trade, country by country, through manipulating the levels of clearing balances and the web of exchange rates applicable to the various accounts. He forced Germany’s neighbors to accept disadvantageous terms if they wanted Germany as a customer. In 1939 Great Britain and its dominions and colonies established clearing accounts with neutral countries to control sterling movements and exchange rates during the war. In 1940 Japan and the Dutch Indies authorities adopted a modified clearing system whereby trade was settled through reciprocal yen and guilder clearing accounts with periodic settlements in dollars of relatively small net differences.11

On 12 August Hall informed Acheson of Britain’s intention to establish a clearing account at the Bank of England for trade with Japan. If Japan offered goods “of essential importance,” Britain would buy them, paying sterling into a special account. Japan could withdraw the sterling, but only to pay for nonessential goods the British might choose to license or for other approved purposes, such as paying interest on prewar loans. The Japanese agreed to cooperate, even though the system denied them the automatic right to transfer funds among countries of the sterling area as permitted to other neutral trade partners. India and Burma expected to set up similar accounts with Japan. However, almost no Japanese-owned sterling movements took place after the freeze, except payments for Indian raw cotton ordered previously.12

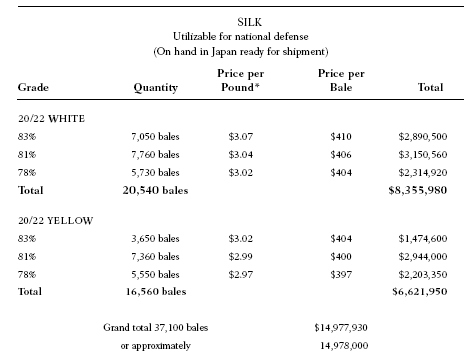

On 5 September 1941 Desvernine returned to the State Department to present to Hull his far-reaching proposal (table 3). Japanese agencies offered to ship thirty-seven thousand bales (4.9 million pounds) of high-quality raw silk, 78 to 83 percent seriplane, white and yellow, “of grade utilizable for national defense.” The bales were owned by the Imperial Silk Company, a quasi-government agency, and ready for prompt shipment by its agent, Mitsui and Company. The delivered value would be approximately $14,970,008 at $3.04 per pound, the U.S. government’s average buying prices for raw silk, which it commandeered from domestic warehouses and factories. Japan wished to receive in exchange twenty commodities worth $14,970,000 at current market prices. All the commodities were available on the West Coast. All cargoes, inbound and outbound, would sail in Japanese bottoms.

Japan’s shopping list paralleled its actual purchases in the first seven months of 1941, other than metals, machine tools, and high-grade gasoline, which had been effectively embargoed prior to the freeze.13 First and foremost, Japan wanted 913,000 tons (about 6.4 million barrels) of petroleum and refined products worth $10,620,000, of which $3,804,000 was to be crude oil from the San Joaquin Valley fields and $6,816,000 refined fuels, primarily ordinary gasoline and diesel oil, plus small volumes of light oil and kerosene. The total volume, roughly one hundred tanker loads, was equal to four months of pre-freeze oil-product purchases. Second, Japan wanted $3.5 million of California cotton, the long-staple variety for weaving superior fabrics and for strengthening ordinary cloth by blending with Indian short-staple cotton. It was an unusual request, perhaps for uniforms, because Japan’s textile exports had virtually ceased while cloth for the civilian market was severely restricted in quality and quantity. Finally, Japan requested fourteen innocuous items worth a total of $819,000, three of which exceeded $100,000: scrap rubber, butyl acetate, and manure salts (low-grade potash). A miscellany of clays, pitch coke, wood pulp, minor chemicals, Vaseline, printing ink, paper rolls for office adding machines, and hops for beer rounded out the shopping list. The scattered list of nonpetroleum articles suggests a Japanese effort to curry political favor with depressed cotton growers and to lend a peaceable coloration to the deal.

TABLE 3 Japanese Barter Proposal to United States, 5 September 1941

*Note: United States government price.

American commodities proposed to be taken in exchange and payment for silk

The two-way exchange of about $30 million of products was Japan’s “initial” offer for discussion, Desvernine said, limited only by the bales of highest grade silk on hand from the spring crop. Within three or four months Japan would offer from the next crop another 10,000 to 15,000 bales of high-grade silk worth $6 million. It also had on hand 100,000 to 120,000 bales of ordinary commercial grade silk, of unstated value but at current prices worth up to $40 million.14 The total value of all the bales on offer, $60 million, exceeded the $52 million worth of raw silk exports to the United States in the first seven months of 1941 and was equivalent to one year’s gold production of the Japanese Empire. Tokyo was inviting, in the aggregate, a two-way swap of $120 million of commodities. The offer did not specify the counterpart U.S. commodities for the second and third lots of silk, but if Japan were again to ask for two-thirds of its recompense in oil, it would acquire altogether twenty-five million barrels, equal to almost one year of pre-freeze oil imports from the United States.15

Hull forwarded the proposal to Dean Acheson, his aide most likely to reject it. Acheson inquired through the Office of Production Management whether U.S. military forces needed any silk. On 13 September he reported back to Hull that the Army and Navy had silk “more than sufficient” for two years for parachutes and other needs and did not want more. Nor was silk for hosiery a necessity, he said, because the OPM was rationing it and directing supplies of substitute fibers. Acheson rendered a peculiar legal opinion, that Roosevelt’s freeze directions prohibited Treasury licenses because silk had been Japan’s main source of dollars to buy oil. It was a wildly improbable interpretation because, in the usual case of trade under freeze rules, a payment to a Japanese seller from blocked funds would languish in his frozen account unless Acheson’s own committee awarded further licenses to spend it. Furthermore, he warned Hull, “private” negotiations like this deal involving Mitsui were harmful to U.S. policy. According to Shanghai sources, the barter scheme was a ploy to incite hosiery manufacturers to lobby for raw silk. Japan had tried similar approaches to other parties, he declared.16

Acheson’s arguments convinced the secretary. Hull orally informed Desvernine’s colleague Shouse three days later that the United States found it impossible to discuss barter with Japan. This was the moment for Henry Wallace, if he wished, to advocate that his EDB intervene and to suggest at least a possibility of barter with Japan. He did not. According to Hull, Wallace scolded Desvernine, telling him that U.S. policy was against the “appeasement” of Japan. Likening the barter ploy to Hitler’s reviled Munich Pact was the kiss of death. At Acheson’s urging, supported by Hull, the vice president dropped the matter altogether, without the courtesy of a written reply. Acheson was never again to be directly challenged about alleviating the freeze of Japanese funds.17

The death of the barter fiasco occurred five days afterward. On 18 September 1941 Nishiyama approached Acheson and Edward G. Miller Jr., the Treasury’s liaison man with State, to ascertain the State Department’s reaction. Nishiyama, believing that applications to deliver raw silk and receive unblocked dollars might be held up because of banking problems, submitted a dense memo by an American silk industry expert purporting to show that Japanese trading firms effectively financed U.S. silk dealers and manufacturers. The inquiry, of course, ended up in Acheson’s hands. He retorted that the State Department could not consider “isolated requests” for commercial deals while Hull and Nomura were engaged in broad policy discussions. “He [Nishiyama] did not press the matter further,” Acheson reported laconically.18

The prodigious barter scheme, sponsored by the government in Tokyo, was certainly not an isolated commercial offer. Nevertheless, Japan’s last hope died that day, no doubt adding to Nishiyama’s frustrated outburst in October. Nomura immediately cabled Tokyo that according to “Desburnin” the prospects of negotiations were now much poorer than when the effort began and that “for the present no consideration would be given to the question of bartering silk for oil.”19 It was the moment when the leaders in Tokyo understood that no trade was possible on any terms at any foreseeable time unless it offered far-reaching concessions in the negotiations dealing with peace in East Asia. On 5 December Cordell Hull groused to Nomura that he had been “severely criticized” for permitting oil exports to Japan in the period before it took southern Indochina. In a classic understatement on that late date the secretary observed “that it was very difficult to resume the supply of oil to Japan under the present circumstances.”20

A postscript to the sorry barter episode unfolded over the next few years. After Pearl Harbor, Desvernine broadcast Wake Up America harangues on the NBC radio network to defend wartime profits and complain of controls on business. Perhaps in retaliation, Attorney General Francis Biddle opened an investigation of his prewar representation of an arm of the Japanese government. Nishiyama had boasted of official authorship of the barter proposal, which was not actually made by Mitsui. Desvernine had also tried to help reopen cotton sales to Japan. Among documents the FBI seized from Japanese files in the United States after Pearl Harbor was a letter from Desvernine to Kazuo Nishi, manager of the Specie Bank’s New York agency, dated 6 December 1941, thanking Nishi for honoring him at a cocktail party. In September 1943 a Justice Department investigator, Jesse Climenko, contacted Acheson. Because in 1941 Hull had telephoned the substance of Acheson’s rejection yet Desvernine “had continued to act as though he was unaware” of it, he might be prosecuted under the Logan Act of 1799. (The act, stemming from a rivalry between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, prohibited private citizens from interfering in official relations with foreign governments. Nobody has ever been convicted under it.) Nothing came of it. In December 1945, the gossip columnist Drew Pearson broke a story that Bernard Baruch, a confidante of FDR, had intervened to squelch Desvernine’s prosecution. Desvernine and Baruch, it was said, had worked all along with Postmaster General Frank Walker “to get information from the Japanese in order to know what they were up to.”21

After collapse of the barter scheme Nishiyama pecked away at other appeals to the Treasury Department. The twentieth of September witnessed him confronting Miller, Fox and Pehle, the department’s Foreign Funds Control staff, with an offer to deliver gold or dollar notes from “Japan and/or China” aboard a ship that would also carry the Asian merchandise stored in Japan to U.S. buyers. The Treasury team brushed him off, telling him that gold and currency were such unusual mediums as to require action by the Interdepartmental Policy Committee—Acheson and friends—which wouldn’t meet for a week. Privately, they thought that greenbacks might be acceptable if rounded up in Japan, but not in China, closing off any serious prospect of that solution.22

The desultory minuet moved to higher levels. On 3 October 1941 Ambassador Nomura appealed personally to Cordell Hull to release payments for the two tankerfuls of oil licensed for export since August. Two uneasy weeks had elapsed without response to Nishiyama’s proffer of gold or currency. Therefore, Nomura said, “despite serious difficulties” Japan had decided to remit dollars from Brazil as proposed earlier by the United States.23 Japan did transfer $170,000 to the United States, Welles learned on 17 October, on the understanding it would be released to the Japanese embassy to pay for the oil cargoes. But the Treasury refused to unfreeze that money from Brazil or any other funds. Another week passed. Then came the denouement. Nishiyama met again with Treasury and State staffers Fox and Miller, who clucked solicitously over his “anxiety for a decision.” He learned, however, that the Interdepartmental Policy Committee could not decide because a new problem had arisen: the insolvency of the Yokohama Specie Bank’s New York agency, the bank that held almost all of Japan’s frozen dollars. Acheson disingenuously accused the Japanese of fomenting a banking crisis by secreting in Brazil more money that ought to be returned to the YSBNY. This was untrue. The solvency crisis arose from U.S. government interference with transfers of money owed to the bank for settlements of silk delivered before the freeze. The surprised and “very disturbed” Nishiyama, shedding his diplomatic sangfroid, complained that the two tankers had been idling in California ever since the freeze. He “wondered whether the question would ever be resolved.” Had the committee rejected the offer of funds from Brazil? Perhaps not, he was told, if Japan produced detailed reports of movements of funds in South America. He would try to respond, he said, but money was fungible and almost impossible to trace specifically. Anyway, what was the connection between minor payments for oil and the solvency of Japan’s largest overseas bank? Would “any method of payment ever be satisfactory?” Smoothly the Americans replied, “This government is always willing to consider any suggestions the Japanese may advance for effecting such payment.” The Japanese diplomat morosely observed, with polite Japanese understatement, that a favorable decision “wasn’t promising.”24 His colleague Iguchi briefed Nomura about the sour news prior to the ambassador’s next meeting with Sumner Welles. Afterward, Welles and Acheson agreed to continue stalling by giving “thorough consideration” to Japan’s proposal.25 Japan’s best course would be to send the tankers home, which is what Tokyo ordered. Acheson, in his memoirs, mused that the last remaining vessel, the Tatsuta Maru, “like the USS Maine and Jenkins’ ear, became the instrument of great events.” It departed in late October with a ballast cargo of asphalt.26

While regulators in Washington stonewalled Japanese pleas to license a few dollars for test shipments of oil, others continued the charade that parts of the United States were running dry of petroleum products, by inference justifying the continued stoppage of oil exports to Japan. Roosevelt, at the urging of Harold Ickes, his petroleum coordinator, had told the nation a parable that curtailing Japan’s oil was appropriate policy because of an impending fuel shortage on the East Coast (chapter 15). The shortage was supposedly due to the British borrowing fifty U.S. tankers to carry Lend-Lease oil across the Atlantic, one-fifth of the fleet that supplied the northeastern states from Maine to Virginia. Ignoring evidence to the contrary, Ickes doggedly persisted in spreading alarms that gasoline consumption would have to be curtailed by 33 percent in the Northeast to leave shipping space for winter fuel oil. The story is told in detail in Appendix 1.

In September a special Senate Committee under Senator Francis Maloney held hearings and concluded that there was no shortage of oil products, nor a shortage of transportation because of efficiencies in shipping as the industry had predicted, and more efficient driving. The railroad companies testified that they could readily make up for any remaining deficiencies by bringing into service twenty thousand idle tank cars. Ickes, outraged, returned to testify in October. He still insisted he was correct and that the railroads were exaggerating. Meanwhile, California had so much surplus capacity after the freeze ended exports to Japan that it was curtailing production and running short of storage tanks. In any case, because of fewer losses to submarines than expected and more tankers leased from the fleets of Norway and Holland, the British began returning tankers and completed the returns in November.

Meanwhile, California crude, fuel oil, and gasoline could not be carried to the East Coast for lack of transportation, which called into question Roosevelt’s pronouncement of 24 July that oil ought not to go to Japan while Americans suffered. Upon imposing the freeze two days later, the White House had declared it designed “to prevent the use of the financial facilities of the United States and trade between Japan and the United States in ways harmful to the national defense and American interests.” Whatever the virtues of the freeze of Japanese assets, the rationale of a U.S. fuel shortage was a political contrivance.27

In the last weeks before Pearl Harbor financial dealings between Japan and the United States dwindled to sniping over trivial sums. A Japanese ship stranded in California without funds for fuel and dock charges was granted money from blocked accounts and discharged after a flurry of high-level correspondence.28 A Japanese-owned cotton exporting firm in Texas, its accounts frozen and with nothing to sell, asked permission to switch to domestic dealings. The Treasury refused, for no obvious reason since the company’s funds would have remained frozen due to its ownership.29 In California odd lots of Japanese goods ordered before the freeze had been offloaded from the vessel Heian Maru and released from customs control, but authorization to honor drafts payable by the U.S. buyers had to be negotiated one by one. Permissions trickled out grudgingly during October and November for a few hundred dollars each of window glass, fishing nets, hog bristles, Christmas ornaments, Kikkoman soy sauce, $80.00 of crabmeat, $31.00 of fishing tackle, and $11.32 of ceramic squirrels. The money was deposited into frozen accounts in Japanese bank branches.30

Japanese diplomats, businessmen, and resident aliens were cut off from drawing on their bank accounts, as were Americans caught by freezing orders in Japan. Tokyo and Washington agreed to allow them to withdraw for subsistence—five hundred dollars and five hundred yen per person per month, respectively, two thousand dollars for Ambassador Nomura—but not dollars to pay Japanese officials in South America.31 Japanese seeking passage home on the repatriation ship needed special dispensation to buy tickets.32 Japanese immigrants traditionally remitted money to wives and children at home, typically twenty-five or fifty dollars at a time. The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco refused to grant a general license, although it allowed the Seattle branch of the Specie Bank to honor 754 “benevolent remittances” under extremely tight supervision.33 As late as 3 December payments for trade journals mailed to Japan was debated at senior levels. The foreign ministries of two great powers had been reduced to quibbling over one hundred dollars in magazine subscriptions.34

Within a month of the freeze it became apparent that the U.S. operations of the Yokohama Specie Bank faced a terminal predicament. On 20 August Attaché Nishiyama furnished the Treasury a report showing that the New York agency’s obligations during the rest of 1941 totaled $11.5 million, $8.5 million of which was for interest and redemption of dollar bonds of Japanese governments and companies payable to owners outside Japan, and $3 million was for operating expenses of the YSB’s U.S. branches. He hoped to have licenses issued to pay from blocked funds.35 According to Herbert Feis, the State Department’s adviser on international economic affairs, dollar bonds issued by or guaranteed by the Japanese government, mostly in the 1920s, totaled $238 million (excluding $27 million of private company issues). He estimated 40 percent were held by Americans, the rest having been resold to Japanese owners. Some $105 million bore interest coupons payable in 1941.36 The Specie Bank agency in New York, the paying agent, had available only $6 million to meet such obligations that, in happier times, it could easily have serviced. But the bank was in trouble because a special freezing order barred it from collecting $16 million it had advanced on imports of raw silk, and $3.5 million for other Japanese goods. The bank held warehouse receipts evidencing its ownership of the silk bales, which had arrived in America before the freeze. Like all Japanese-controlled assets, transfer of the bales to customers required Treasury licenses. The bank had pleaded for permission to release the silk to local Japanese importing houses for onward delivery to U.S. factories and to collect the money it was owed.37 Edward G. Miller Jr. demurred. The Treasury could not, he said, agree to obligate itself to issue licenses for a series of transactions over a long period of time. It would only deal with specific licenses on the facts of each transaction.38 The State Department regarded the bank’s dilemma as genuine. Feis had recommended to Acheson on 19 September that the U.S. government license the silk settlements and allow payments to bondholders; funds flowing into the bank agency in excess of bond service would remain blocked by the freeze while the silk would remain in the country subject to government order.39

In October bank examiners of the office of Comptroller of the Currency determined that, without an inflow of money, the YSBNY could not survive for long. Nevertheless, it objected to releasing the bank’s valuable security (the bales of silk) to unknown and possibly insolvent buyers, or even to a first-class buyer such as Mitsui, ostensibly because the customers had not applied for licenses to take ownership and pay the Specie Bank. It was a charade of circular reasoning. The U.S. Defense Supplies Corporation had commandeered all silk inventories in the United States to be held for its purchase. If the USDSC had paid promptly there would have been no problem. It had insisted, however, on leisurely retesting to confirm quality, even though raw silk was subjected to rigorous commercial testing in both Japan and America. With its banking license coming up for renewal on 15 November, the YSBNY faced a crisis. The San Francisco branch was also in trouble.40 On 28 November the five Japanese New York banking agencies announced plans for suspending activities if necessary. As the New York Times observed, in the event of war, their affairs would be taken over by the Alien Property Custodian.41 That is exactly what happened.

On 7 December 1941 officers of the New York State Banking Department worked through the night in preparation for seizure of the Japanese banks. The following morning they took control of the offices, which ceased operations except as directed by the U.S. government. The Japanese staff was interned and eventually repatriated along with Japanese diplomats on neutral ships. Control of the banks passed in March 1942 to the Office of the Alien Property Custodian, which presided over liquidation of their assets.42 During and after World War II, U.S. owners of Japanese bonds and other claimants filed for recompense from the blocked accounts. Some were paid, including Standard-Vacuum for oil it had delivered to Japan from the East Indies, but a $17 million claim by the Bank of Japan was disallowed after the war. Justice was long delayed to one group: citizens and residents of Japanese descent who were forcibly relocated during the war and who had deposited in small sums $10 million in Japanese bank branches in California, primarily at the Specie Bank. The Office of Alien Property Custodian offered compensation, but because the branches kept their books in yen, it ruled that the money represented funds in Japan and should be returned at the postwar yen exchange rate of 360 to the dollar versus the prewar rate of 4.3, that is, about 1 percent of the original value of the deposits. A few accepted. Others sued the United States. Their case was argued up to the Supreme Court, which accepted it for trial despite the U.S. government’s arguing that the statute of limitations had run out. On 10 April 1967 the court ruled eight to zero that seventy-five hundred depositors were entitled to full compensation of $10 million. It reasoned that Congress had intended that procedures under the Trading with the Enemy Act were akin to bankruptcy proceedings in which belated claims were allowable; it did not concede that the government had acted “unconscionably.”43

In 1947 U.S. occupation authorities ordered the Yokohama Specie Bank dissolved. It reemerged later as the Bank of Tokyo with a much enlarged worldwide network of branches.44

Was the financial freeze a more potent form of economic warfare than commodity embargoes? Dean Acheson thought so. The assistant secretary of state, an officer of the department traditionally charged with peaceful solution of tensions through diplomacy, looked back with satisfaction on 22 November 1941. In a report to Hull on the “Present Effect of the Freezing Control,” which may have gone higher in the administration, Acheson listed achievements that could not have been accomplished as well, or at all, by regulation of trade. With evident relish he reported:

•The freeze had slashed U.S. exports to Japan from $10 million per month to nil. Although export licensing control had been extended to petroleum and most other strategic goods, Japan might still have purchased lumber, raw cotton, foodstuffs, and other articles commonly available to neutral countries under general licenses. Acheson especially noted that foods for Japan and occupied China (other than edible fats and oils) were barred only by the financial freeze.

•Dollar freezing impeded or stopped Japanese commerce with South America and the rest of the dollar bloc. It helped end trade with the Netherlands Indies that was conducted partly in dollars, stiffening the Indies’ own embargo.

•The freeze was “our machinery for controlling imports” from Japan, a policy not addressed by any other executive order. Japan would “undoubtedly” have sold silk despite the few U.S. goods still available to buy in return, in order to defend market share against conversion of the hosiery industry and consumer preference for nylon.

•Japanese assets in the United States, had they not been immobilized, would have been withdrawn because the United States did not have other legal exchange controls.

•The freeze of Chinese assets stabilized the yuan and blocked Japanese evasions through the Shanghai exchanges.45

While Acheson’s boast acknowledged that tighter export licensing might have achieved some of the same results, it remained a robust tribute to the potency of dollar warfare. In 1941 the relentless dollar freeze threatened to pauperize Japan. Japan’s response was not long in coming. On 22 November, the day of Acheson’s self-congratulatory survey, the last of six Japanese aircraft carriers arrived at Hitokappu Bay in the Kurile Islands, from where they would sail four days later for Pearl Harbor.