Who knew that the 2012 presidential campaign would turn into a 1960s flashback? For many of us, the moment of awakening was when Republican candidate Rick Santorum seemingly stepped out of a time machine and proclaimed his opposition not just to abortion rights but to birth control as well. The controversy began when columnist Charles Blow rediscovered Santorum’s 2008 speech to the Oxford Center for Religion and Public Life in Washington, including this comment the senator made during the question-and-answer period:

You’re a liberal or a conservative in America if you think the ’60s were a good thing or not. If the ’60s was a good thing, you’re left. If you think it was a bad thing, you’re right. And the confusing thing for a lot of people that gets a lot of Americans is, when they think of the ’60s, they don’t think of just the sexual revolution. But somehow or other—and they’ve been very, very, clever at doing this—they’ve been able to link, I think absolutely incorrectly, the sexual revolution with civil rights.1

With all due respect to Senator Santorum, I do see connections between the sexual revolution and the civil rights movement, and his comments suggest that he does too, even if he believes they have been linked erroneously. In fact I venture to say that many of the issues in today’s culture wars—gay and transgender rights, gender equality, reproductive choice—center on the disputed territory of sexual norms and are argued in terms of civil rights and government authority to dictate morality. As a means of expressing sexual and gender identity, the fashions of the time revealed the cultural shifts set in motion by the women’s liberation movement and the sexual revolution. The countermovements and controversies over these changes are likewise visible, particularly in the scores of legal cases involving long hair on men: cases that explicitly enlisted the language of civil rights.

This book began as an exploration of gender expression in unisex clothing from the 1960s and 1970s. The culture of that era is a puzzle, even to those of us who lived through it. Was it the “Me Decade,” characterized by narcissism and self-indulgence? Or was it a time of social activism and experiments with communal economies? Did we discover our environmental conscience or dig ourselves even deeper into consumerism? The question originally animating this research was this: Was unisex fashion simply a playful poke at gender stereotypes, or was it a deeper movement to become our “true,” unessentialized selves? Over the past thirty years the ’60s and ’70s have been reduced to a laughable era of loud clothes and crazy hairstyles, just another ride in the pop culture theme park. It is easy to dismiss dress history as a superficial topic, meaningful only to fashionistas and industry insiders. Most of the popular works on ’70s fashion are image-heavy exercises in nostalgia, often with a touch of humor. Those crazy people and their wacky clothes! The problem with popular images of fashion is that they tend to erect a trivial facade over real cultural change.

As I went more deeply into the subject, nostalgia was replaced by déjà vu. Even before Senator Santorum made his revealing remarks, it was obvious to me that we are still wrestling with controversies about sex, gender, and sexuality that manifested themselves in the fashions of fifty years ago. Sometimes the argument was loud and public and fought in the courtroom, as with the question of long hair for men. Sometimes it was an inner, personal conflict between the tug of deeply ingrained feminine expressions and the ambition to succeed in a male-dominated profession. Exploring the rich cultural setting of unisex fashion not only contributes to our understanding of history but also helps us comprehend the current culture wars. It is not hyperbole to say that the lives of today’s children are still being shaped by the unresolved controversies rooted in the social and cultural upheavals of the 1960s and embodied in fashions of the ’60s and ’70s.

I study gender because it is what I must untangle in order to understand my own life. For others the puzzle may be race, death, or something else, but my deepest questions have always been about this paradoxical thing we call gender. I call it “paradoxical” because the term was invented in the 1950s to describe the social and cultural expressions of biological sex. Yet in everyday usage the concepts of sex and gender are almost always conflated, inseparable in many peoples’ minds. Because my relationship to the subject is, and has always been, personal, I include my reflections as part of the body of evidence. Not that my experiences were more authentic than anyone else’s. Rick Santorum also lived through the ’60s and ’70s, though as a man born in 1958, not a woman born in 1949. It is important that our histories incorporate diverse voices, and I include mine as one of millions.

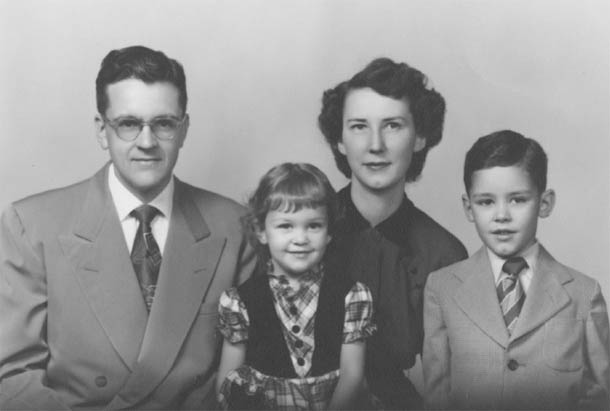

Gendered clothes for a formal portrait, 1952.

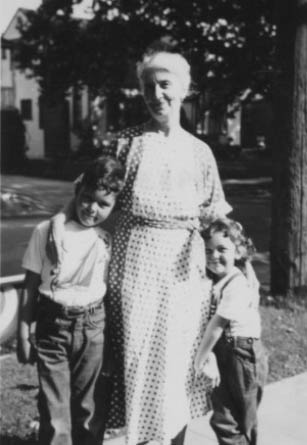

You see me here in three very different childhood pictures. The formal portrait is me at about three and a half, in a velvet-trimmed dress I still remember fondly. My mother’s red houndstooth check dress was also trimmed with velvet, and my father and brother wear nearly identical warm gray suits. We look like the very model of a gender-appropriate family in 1952. The snapshot of my brother and me was taken around 1953 on a family vacation. My hair is in its natural unruly state, and I am wearing my brother’s old T-shirt and jeans. This was my world in the 1950s: dresses and pin curls for school, church, and parties, but jeans for play. I wanted to be a cowboy when I grew up, and one Christmas my parents humored me with a cowboy outfit with a two-gun holster. I adore all of these pictures, because they are all so very me.

I got my first period the year after the Pill was approved by the FDA. In 1963, when Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique was published, I was just starting high school. Like so many young women who were swept along in the sexual revolution and the cultural shifts of the 1960s, I was promised much and given, well, not little, but less than the word “revolution” implied. The more I pursued the idea of “gender,” the more it got tangled up in sex. This became ever clearer as I explored unisex and gendered clothing from the 1960s and 1970s. There were so many dead ends, so much confusion, and so very much unfinished business! Researchers thrive on open questions; gender is mine, because it is the aspect of my own life that puzzles me most.

Neutral styles for leisure, 1953.

The project also became broader, more complicated, and its scope widened. Enlarging the time frame was easy: while unisex fashions peaked in the early 1970s, they first appeared in the 1960s and did not shift out of the foreground until around 1980. When I realized that designer Rudi Gernreich had created both unisex fashions and the topless bathing suit, it was clear that the sexual contradictions of the period demanded attention. Reflecting the revised scope of the project before me, the working title for this book went from “Unisex: The Unfinished Business of the 1970s” to “Sex and Unisex: Fashion, Feminism, and the Sexual Revolution.” “Feminism” dropped in and out of the title as I pondered the constrained and loaded meanings of that term. Finally it stayed in, because the feminist movement for gender equality was an important factor in the linkage between the sexual revolution and civil rights, and because as I completed this book in 2014, feminists were being blamed for all sorts of ills, from poverty to the decline of toughness in our foreign policy.2

Jo Barraclough, cowboy, 1956.

The actual timeline addressed in this book is complex. It includes the early 1960s, with teens and young adults imitating popular musicians, and with young designers producing clothing for a new generation inspired by the civil rights movements and the sexual revolution. Designers from Paris (Pierre Cardin) to Hollywood (the uniforms in Star Trek) imagined a future of equality and androgyny—within the limits of their own worldviews, of course. The movement of women into male-dominated professions, facilitated by the equal employment opportunity portion of the Civil Rights Act, coincided with the rise of professional clothing for women. The history of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the U.S. Constitution, which was reintroduced to the public discussion in the late 1960s, parallels the popularity of unisex clothing for both men and women. Passed by Congress in 1972 when unisex trends began to peak, the ERA ultimately failed state ratification, vanishing from the nation’s agenda at the same time more stereotypically gendered styles were enjoying a revival.

The unisex movement affected all ages, in part simply because adult fashions trickled down to school-age children. Beyond the usual influence of fads and fashions, public discussion about the origins and desirability of traditional sex roles fueled changes in clothing for babies and toddlers beginning in the early 1970s. Between 1965 and 1975, girls started wearing pants to school, just as their mothers wore them to work. Boys as well as men enjoyed a brief “peacock revolution,” when bold colors and patterns brightened their wardrobes. Legal battles were fought over hair, beginning with lawsuits over school dress codes but eventually extending to the military, police and firefighters, and white-collar workers. These sartorial changes occurred against a backdrop of intense popular and public policy discourse on issues ranging from access to contraception in the 1960s to girls’ participation in organized sports, following the passage of Title IX in 1972. The pendulum started to swing back toward more traditionally feminine clothing in the mid-1970s with designer Diane Von Furstenberg’s wrap dress (1974) and the launch of Victoria’s Secret (1976), and by the mid-1980s unisex fashions had largely faded into the haze of nostalgia.

For the most part, “unisex” meant more masculine clothing for girls and women. Attempts to feminize men’s appearance turned out to be particularly short-lived. The underlying argument in favor of rejecting gender binaries turns out to have been more binaries. First there was a forced decision between gender identities being a product of nature or nurture. For a while the nurture side was winning. Gender roles were perceived to be socially constructed, learned patterns of behavior and therefore subject to review and revision. Unisex fashions were one front in the culture wars of the late ’60s and ’70s, a war between people who believed that biology is destiny and those who believed that human agency could override DNA. As more people accepted the significant cultural nature of gender, a new binary emerged. Either culturally dictated gender roles were good and necessary, or they were outmoded and dangerous. Throughout this book I try to expose how categories and labeling, while useful in many ways, can also perpetuate stereotypical thinking. Stereotypes encourage simplistic ways of viewing a complex world. There is a reason why humans use stereotypes: they help us make quick decisions in confusing or chaotic situations. But quick decisions are not always the right ones. Many of our gender stereotypes are superficial, arbitrary, and subject to change. (This was the main point of my first book, Pink and Blue.3) Boys one hundred years ago wore pink and played with dolls. Legos used to be unisex. Field hockey is a man’s game in India. Elevating stereotypes to the level of natural law is, well, silly. Most of our gender stereotypes depend on our believing that sex and gender are binary; to summarize the last fifty years of research on the subject, however, they are not. There are babies born every day who are not clearly boys or girls on the outside, and our insides—physical, mental, and emotional—comprise an infinite range of gender identity and expressions.

The unisex movement—which includes female firefighters, football star Roosevelt Grier’s needlepoint, and Free to Be . . . You and Me—was a reaction to the restrictions of rigid concepts of sex and gender roles. Unisex clothing was a manifestation of the multitude of possible alternatives to gender binaries in everyday life. To reduce the unisex era to long hair vs. short hair, skirts vs. pants, and pink vs. blue is to perpetuate that binary mind-set and ignore the real creative cultural pressure for new directions that emerged during this period. Reducing the pursuit of equal rights to the clothes worn to a protest trivializes the most important social movement of our lifetime.

Lest anyone worry that this is going to be a memoir, my research draws on dress history, public policy, and the science of gender, not just my own frail memory. To describe the various styles and trends associated with unisex fashion, I consulted mass-market catalogs, newspaper and magazine articles, and trade publications. Each of these sources offers a slightly different perspective on the trends. Catalogs and the popular fashion press tend to be neutral or positive about new fashions; industry sources (Earnshaw’s, Women’s Wear Daily, Daily News Record) can be more sanguine, especially as a trend begins to fade. Critical views can come from newspapers and magazines but are especially plentiful in cartoons and other forms of humor. The legal and policy reactions to unisex styles include court cases, government regulations, and dress codes, such as those relating to hair length for men and pants for women. The judicial opinions handed down in these cases were particularly helpful in tracing the shifts in what is considered “generally acceptable” forms of dress. Scientific inquiry into gender and sexuality during this period expanded rapidly as a response to feminism, the sexual revolution, and the gay rights movement. The scientific literature, both academic and popular, provides vital insights into the competing schools of thought on what constituted “normal” sexuality and gender expression and how the scientific evidence was (or was not) translated into popular opinion and practice.

Sex and Unisex offers an interdisciplinary analysis of the gender issues raised during the 1960s and ’70s in the United States. Each chapter focuses on one element of the unisex movement, illuminating the conflicts within it and how unresolved issues are still playing out today. At the same time, every chapter addresses some of the same organizing questions: What variations of gendered and unisex design are evident, and what do they reveal about underlying conflicts about sex and sexuality? How were conceptions of masculinity and femininity highlighted or subverted by unisex styles? Along the way I consider the reactions of those people who adopted unisex fashion and those who resisted them. My main argument is that this era, its conflicts and its legacy, reveals the flaws in our notions of sex, gender, and sexuality, right down to the familiar dichotomy of “nature or nurture.” These flaws underlie the unfinished business at the intersection of the sexual revolution and the civil rights movement as revealed in today’s culture wars.

The role of science and social science research in framing the public debate on gender is especially significant. It is no coincidence that studies of sex and gender expanded dramatically during the 1960s and 1970s as the women’s liberation movement gathered momentum. Many of these were either reported in the newly launched Psychology Today (1967) or Ms. (1971), both of which played important roles in translating often-obscure scientific studies into popular articles. The credibility and persuasive power of scientific evidence is based on its reputation as objective, but critics have pointed out that the science of gender often falls short of perceived objectivity. The questions, protocols, and interpretation of gender science have often been shaped by the researchers’ cultural context, if not by their personal concerns or political persuasions. At the publication level the decision of what reaches the public, and at what stage, affects not only public awareness of the findings but also whether it is accepted as scientific “truth.” The story of unisex fashion, and the larger unisex movement, needs to be placed in the context of gender science as it developed as a field and as it informed the public. Each chapter in this book foregrounds a particular aspect of unisex fashion and connects it with both the public conversation surrounding it and the scientific knowledge that was shaping public opinion.

In chapter 1, “Movers, Shakers, and Boomers,” I look at the generational push toward gender-free fashion as an expression of the coming of age of the postwar baby boom generation. Admittedly most teenagers in the 1960s did not have a “war on culture” in mind when they emulated their musical idols or adopted the fresh designs of Rudi Gernreich and London’s Carnaby Street. Gernreich, the Austrian-born American designer and gay rights activist, introduced both the topless bathing suit and many of the most iconic unisex fashions. Even more than fashion designers, musicians were the undisputed style leaders of the early 1960s, with the televised appearances of groups such as the Beatles and the Supremes inspiring millions of young consumers. Besides changing American music, popular performers spread new expressions of sexuality, particularly for men. The conflict between styles that were intended to display and celebrate the human body and a movement to erase differences that result in inequality is a major theme in fashion from the mid-1960s on and remains unresolved as the baby boomers enter old age.

The next chapter, “Feminism and Femininity,” traces the changing notion of femininity in the face of second-wave feminism, beginning with the 1963 publication of The Feminine Mystique. While I focus on the most visible sartorial change for girls and women during the period, which was the acceptance of pants outside of leisure settings, I also consider the impact of styles of teen-oriented fashions—part of the cultural movement Vogue editor Diana Vreeland christened the “Youthquake”—on women’s bodies. Women’s bodies themselves became more visible (literally, as hemlines rose) and were reshaped through exercise and new styles of undergarments (or none at all). The sexual revolution gave women credit for having sexual appetites, and the Pill gave them the means to satisfy those appetites without fear of pregnancy, but it also gave us a new “feminine mystique”: the sexually liberated, available sex object, epitomized by Helen Gurley Brown’s “Cosmo Girl.” The paradox of this era is that the pressure on women to be attractive—young, slender, and sexy—intensified and gradually spread to all ages. I discuss the clothing worn by singer Cass Elliot of the Mamas and the Papas as an example of the resistance that was possible due to the sheer variety of available styles at the time.

Chapter 3, “The Peacock Revolution,” focuses on the expansion of choices for men, ranging from Romantic revival (velvet jackets and flowing shirts) to a pastiche of styles borrowed from Africa and Asia. Journalist George Frazier popularized the phrase “peacock revolution” to describe the styles coming from London’s young Carnaby Street designers, which promised to restore the lost glory of flamboyant menswear. Expanded color palettes, softer fabrics, and a profusion of decorative details represented a very direct challenge to the conformity and drabness of menswear at mid-century. For critics of new men’s fashions, flowered shirts and velvet capes raised the specter of decadence and homosexuality, a fear reinforced by the emergence of the gay liberation movement. Just as women’s unisex styles had to balance being sexy and liberated, men’s styles tended to navigate the territory between expressiveness and effeminacy. That tension still exists, kept alive by unfolding controversies about LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) rights.

Barbershops felt the immediate effect of unisex trends: haircuts went from a weekly ritual to an occasional, do-it-yourself task. When men finally returned to regular styling, they tended to patronize “unisex salons,” not barbershops. An entire new industry was born in the mid-1970s, as the once modest market for male grooming and grooming products expanded. Today not only are unisex hair salons still thriving, but upscale barbershops are competing with them for a portion of the huge market for male grooming, including manicures, antiaging treatments, and body hair removal, or “manscaping.” The long hair saga provides insight into the continuing, often covert, movement to permit men as much personal expression as women.

In chapter 4, “Nature and/or Nurture?” I turn to children’s clothing and the most fundamental questions of the unisex era: What is the origin of gendered behaviors, and can they be changed? As the women’s movement challenged traditional female roles and popular media seemed to offer new expressions of masculinity and femininity, public attention turned to early childhood and the potential to alter the future by changing the way children learn about gender. Scientific evidence pointed to gender roles being learned and malleable in the very young. Children born between the late 1960s and the early 1980s were likely to have experienced nonsexist child raising to some extent, whether at home, school, or through media like books and television.

This particular aspect of the unisex movement offers the richest source of evidence of popular beliefs about sex, gender, and sexuality, which were often strongly influenced by parental ambivalence and anxiety. This chapter places changes in children’s clothing styles in the context of competing scientific explanations of gender and sexuality, how well they were understood by the general public, and how children responded to the unisex movement. Nor have the questions raised forty years ago been satisfactorily answered; the public is still divided over issues of gender and sexuality. Whether the topic under discussion is same-sex marriage or gender-variant children, beliefs about nature and nurture—based on science or scripture—are fundamental to the arguments.

In chapter 5, “Litigating the Revolution,” I examine the legal side of the unisex movement, focusing mainly on the battle over long hair on boys and men and the impact of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The British Invasion in popular music deserves much of the credit for the early trend toward longer hair for men. But the Black Power movement further complicated questions of gender-appropriate grooming by intersecting them with expressions of racial identity. Men with long hair faced considerable criticism and resistance, with many confrontations ending in court, as had been the case with women wearing pants. African American women opting for Afros and braids also experienced criticism and discrimination as the dialogue about gender expanded to include “natural” versus “artificial” beauty. Battles over hair length began in high schools and gradually expanded into the workplace and the military. Young men daring to wear their hair long were accused of everything from anarchy to homosexuality, which suggests just how disruptive it seemed to their parents, teachers, and bosses. Within a few years many of those parents, teachers, and bosses also sported sideburns and hair creeping past their collars; by 1972 the judge in one long hair case noted, “The shift in fashion has been more warmly embraced by the young, but even some of the members of this court, our male law clerks and counsel who appear before us have not been impervious to it.”4

Title VII (Equal Employment Opportunity) had an enormous impact on workplace clothing for women and for both men and women in formerly single-sex professions such as police officer and flight attendant. That story is told here through a description of the efforts to develop appropriate uniforms and through analysis of the initial changes in uniform styles. Title IX (Equal Opportunity in Education) was responsible for an expansion of girls’ and women’s sports programs at the high school and collegiate level. As women’s sports gained funding and recognition, the clothing worn for those sports were redesigned.

Neither of these issues is yet settled in terms of policy or popular culture. Although women now account for more than half of the workforce, they continue to be paid less than their male counterparts for similar positions. Female sports stars are as likely to be recognized for their appearance as for their ability. The importance of beauty and sexual display, even in the workplace, seems even greater than it was before the unisex movement. This chapter juxtaposes sociological research on women’s equality with the rise and fall of unisex clothing for work and sports.

The final chapter, “Culture Wars, Then and Now,” summarizes and synthesizes the themes from previous chapters, bringing the discussion around to the current cultural landscape. Some of the innovations of the unisex era—pants for women, for example—represent permanent changes in cultural patterns but not a revolution in gender roles. Other trends from the 1970s—unstructured alternatives to men’s business suits, for example—turned out to be short-lived fads. The sexual revolution and the gains of the civil rights era are still controversial, and the clothing changes that originally accompanied them are an important way to reveal the outlines of today’s conflicts. Today’s fashions and beauty culture continue to be sources of tension for women, between their need to be taken seriously (as workers, athletes, and human beings) and the traditional role of clothing as a form of self-expression and a means of enhancing one’s sexual attractiveness.

In addition, new issues have emerged from the unresolved questions of the 1970s. Who in 1975 could have predicted that the 2012 presidential election campaign would feature arguments about the centerpiece of the sexual revolution, the contraceptive pill? That princess merchandise for preschoolers would be a billion-dollar industry? That X: A Fabulous Child’s Story would be enjoying a revival among a new generation of young parents longing for ungendered clothing and toys for their babies? That the new frontiers in civil rights would be same-sex marriage, transgender rights, and the protection of gender-creative children? By examining the cauldron of the sexual revolution through everyday fashions, I hope to restart the dialogue we abandoned a generation ago and move us closer to resolving both old and new controversies.

The fashion industry has spent billions of dollars convincing us that fashion is frivolous. Yes, fashion is fun, but clothing is also bound up with the most serious business we do as humans: expressing ourselves as we understand ourselves. In the 1960s and ’70s millions of Americans were struggling with existential questions: Who am I? What does it mean to be fully who I am? What rules are worth following and which should be discarded? Barriers of race, class, religion, and gender were being challenged by some and protected by others.

The story of these experiences is found in every trace of culture from that time period. It could be experienced through so many lenses—politics, music, humor, drug culture, alternative economies—but I have chosen to examine it through clothing and appearance, because dress has been my lens since I was very young. Having lived through that time as a teenager and young woman who followed fashion and eventually majored in it in college, I am amazed to admit that I did not fully comprehend the size and ferocity of the larger cultural conflict going on around me at the time. I cannot remove myself from the story, so I must place myself within it. Some of my academic peers, especially those outside American Studies, may find this self-reflexivity uncomfortable, but as I see it, I had a choice. I could omit my experiences and give the impression that my historical analysis, written decades after the fact, coincides with my original personal experience. But it doesn’t. The 1970s Jo was too busy living to do a “close read” of her own times. So instead I’ve included my experiences as proof that we experience cultural change from such a personal stance that it can feel like we are and are not part of that change at the same time.

Readers of the era under discussion will find some familiar stories here, but they may also find themselves thinking “that’s not the way I experienced it.” I hope they will share their versions too. Readers who were elsewhere or not yet born know this era only through family stories and media stereotypes. They realize that what they’ve seen is probably not the whole picture, but it’s all they have. Hopefully this book will help them get a more accurate idea of the relationship between gender and fashions of the times. And even more hopefully there will be more books, articles, and discussions to follow. The world we live in today is cluttered with the unfinished business of the sexual revolution, and too many of the questions in the 1960s and 1970s have never been answered.

Inevitably this is an incomplete account. Gender identity can never be separated from race, class, age, or other personal dimensions. One of the biggest challenges I have faced with this project has been discerning how to contain it without either oversimplification or confusion. Considering the many different effects generated by the social and cultural forces of the early 1960s, the more factors I introduced, the more I risked a tangled, confused argument. My decision to focus on the gender identity issues as they were manifested in the broad age/sex categories of the fashion marketplace (children, teens, women, men) resulted in a more diffuse treatment of race than I originally intended. Rather than add racial identity to the mix throughout, or craft a separate chapter to highlight the racial dimension of fashions, I have incorporated some of this material into each chapter. There were moments in the ’60s and ’70s when gender and racial stereotypes clearly collided in mainstream fashion—for example, the use of African American models to display “exotic” or flamboyant styles. A few of the early legal cases involving workplace dress codes raised issues of both gender and racial discrimination. Thankfully there are important recent works on the intersection of race and gender in fashion,5 and this book will not be the last word; the door is wide open for future researchers.

Culture changes. In fact we are so used to the notion that it changes that we find it hard to imagine living in a society where the culture of our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents is the same culture that surrounds us today. We have never experienced cultural stability, except as a childhood illusion. During our entire lifetimes culture has been changing around us, and we have changed culture. In our day-to-day lives we have argued about culture because we see that it can change, we believe that people can change it, and we are both excited and afraid. Women in our society exist in a reality where culture change, in the form of fashion, is an almost constant part of our lives, but industrial man has managed to finesse this by freezing masculinity with the adoption of the business suit. Through the suit and tie, men experience a common thread between themselves and earlier generations of men in a way that women cannot.

Perhaps the most perplexing puzzle when it comes to fashion is the relationship between masculinity and femininity. How does this underlying relationship influence what happens when one role or both change drastically? This is what happened in the 1960s and ’70s, when it seemed that both masculinity and femininity were being redefined and yet there was no blueprint, no plan, and no endgame—only questions.