Clinical Approach to the Patient with HIV

Diagnosis and natural history

HIV is now a manageable chronic condition with a life expectancy that can match that of the general population, in those who start effective ART early enough. Starting treatment when disease is more advanced compromises clinical outcomes. In 2013, 24% of those living with HIV in the UK were unaware of their infection; 42% of people newly diagnosed in the UK in 2013 were ‘late presenters’ – that is, they had a CD4 count below the threshold to start therapy (<350 cells/mm3); and in 33%, the CD4 count was <200 cells/mm3, putting them at high risk of HIV-associated pathology (Fig. 12.12). Increasing the uptake of HIV testing is a major public health objective. Guidelines on HIV testing from the British HIV Association (BHIVA) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) include clinical settings in which HIV testing should be universally offered, together with a list of clinical situations and diagnoses (indicator conditions) that are highly predictive of HIV infection and in which HIV testing should be recommended (Box 12.8). Testing should be recommended for all new registrants in primary care and patients admitted to acute medical care in areas of the UK where HIV seroprevalence is >2/1000 population.

Discussion about HIV testing and the consent required is straightforward and within the competencies of a wide range of healthcare professionals. Sensitive and specific point-of-care HIV antibody tests using either blood or oral fluids can give results within minutes and have extended the possibilities for diagnosis. Home sampling approaches, with specimens sent to a central laboratory and results given over the telephone, have been shown to increase testing rates in some populations. Changes in legislation in the UK now allow for the sale of home testing kits for HIV, although ‘kite-marked’ kits are not yet available. It is crucial for all reactive point-of-care tests to be followed up with confirmatory serological assays and for appropriate arrangements to be made to ensure that patients receive their test results and those who are found to be HIV-positive have rapid routes into specialist care.

Investigation of HIV

HIV infection is diagnosed either by detection of virus-specific antibodies (anti-HIV) or by direct identification of viral material. The recommended UK first-line assay is one that tests for HIV antibody and p24 antigen simultaneously. These fourth-generation assays have the advantage of reducing the time between infection and an HIV-positive test result to 1 month, which is several weeks earlier than with sensitive third-generation (antibody-only detection) assays.

Detection of IgG antibody to envelope components

This is the most commonly used marker of infection. The routine tests used for screening are based on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) techniques, which may be confirmed with Western blot assays. Up to 3 months (mean 6 weeks) may elapse from initial infection to antibody detection (serological latency, or window period). These antibodies to HIV have no protective function and persist for life. As with all IgG antibodies, anti-HIV will cross the placenta. All babies born to HIV-positive women will thus have the antibody at birth. In this situation, anti-HIV antibody is not a reliable marker of active infection, and in uninfected babies will be gradually lost over the first 18 months of life.

Simple and rapid HIV antibody assays are increasingly available, giving results within minutes. Assays that can utilize alternative body fluids to serum/plasma, such as oral fluid, whole blood and urine, are now available and home testing kits are being developed. These tests are extremely sensitive and may give false-positive results, making it necessary to perform a confirmatory test.

A serologic testing algorithm for recent HIV seroconversions (STARHS) can be used to identify recently acquired infection. A highly sensitive ELISA that is able to detect HIV antibodies 6–8 weeks after infection is used on blood in patients with a positive oral fluid test, in parallel with a less sensitive (detuned) test that identifies later HIV antibodies within 130 days. A positive result on the sensitive test and a negative ‘detuned’ test are indicative of recent infection, while positive results on both tests point to an infection that is more than 130 days old. The major application of this is in epidemiological surveillance and monitoring.

Detection of IgG antibody to p24 (anti-p24)

This can be detected from the earliest weeks of infection and through the asymptomatic phase. It is frequently lost as the disease progresses.

Genome detection assays

Nucleic acid-based assays that amplify and test for components of the HIV genome are available. These assays are used to aid the diagnosis of HIV in the babies of HIV-positive mothers or in situations where serological tests may be inadequate, such as in early infection when antibody may not be present, or in subtyping HIV variants for medico-legal reasons. (See the discussion of viral load monitoring on p. 339.)

Detection of viral p24 antigen (p24ag)

This is detectable shortly after infection but has usually disappeared by 8–10 weeks after exposure. It can be a useful marker in individuals who have been infected recently but have not had time to mount an antibody response.

Isolation of virus in culture

This is a specialized technique available in some laboratories as a diagnostic aid and a research tool.

Clinical features of untreated HIV

The spectrum of illnesses associated with HIV infection is broad and is the result of direct HIV effects, HIV-associated immune dysfunction, and the drugs used to treat the condition, as well as coexisting morbidity and co-infections. Since the introduction of effective therapy, the majority of people with HIV in resource-rich settings begin treatment whilst asymptomatic, before the onset of significant immunosuppression or progression to an AIDS-defining event.

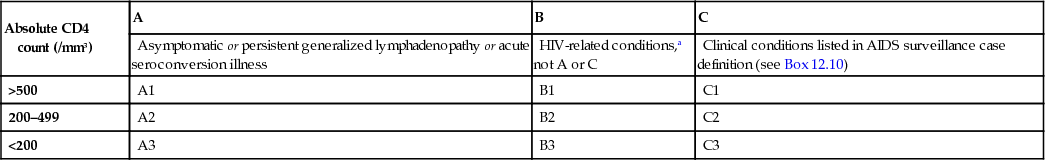

Several classification systems exist, the most widely used being the 1993 Centers for Disease Control (CDC) classification (Box 12.9). This classification depends, to a large extent, on definitive diagnoses of infection, which makes it more difficult to apply in those areas of the world without sophisticated laboratory support.

As immunosuppression progresses, the patient is susceptible to an increasing range of opportunistic infections and tumours, certain of which meet the criteria for the diagnosis of AIDS (Box 12.10).

The definition of AIDS differs between the USA and Europe. The US definition includes individuals with CD4 counts of <200 cells/mm3, in addition to the clinical classification based on the presence of specific indicator diagnoses shown in Box 12.9. In Europe, the definition remains based on the diagnosis of specific clinical conditions with no inclusion of CD4 lymphocyte counts. Where ART is available and started before the development of severe immunosuppression, progression to AIDS is now uncommon.

Incubation, seroconversion and primary illness

Primary HIV infection (PHI) refers to the first 6-month period following HIV acquisition. This is a period of uncontrolled viral replication resulting in high levels of HIV circulating in the plasma and genital tract, and consequently of high infectiousness. At a population level, PHI is increasingly recognized as a contributor to onward transmission. In the UK, up to 20% of all newly diagnosed individuals are recently infected. The 2–4 weeks immediately following infection may be silent, both clinically and serologically. In a number of people, a self-limiting acute viral illness, which may be confused with glandular fever, occurs 3–6 weeks after exposure. This is a key point for making the diagnosis; however, HIV is frequently not considered in the differential. Symptoms include fever, arthralgia, myalgia, lethargy, lymphadenopathy, sore throat, mucosal ulcers and, occasionally, a transient, faint pink, maculopapular rash. Neurological symptoms are common, including headache, photophobia, myelopathy, neuropathy and, in rare cases, encephalopathy. The illness lasts up to 3 weeks and recovery is usually complete.

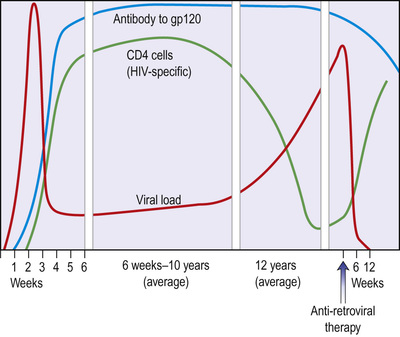

Laboratory abnormalities include lymphopenia with atypical reactive lymphocytes noted on the blood film, thrombocytopenia and raised liver transferases. CD4 lymphocytes may be markedly depleted and the CD4:CD8 ratio reversed. Antibodies to HIV may be absent during this early stage of infection, although the level of circulating viral RNA is high and p24 core protein may be detectable. NAAT assays of HIV RNA may be diagnostic 7 days before a p24 antigen test and 12 days before a sensitive HIV antibody test. If PHI is suspected but standard diagnostic tests are negative, then repeat testing in 7 days and referral for expert advice is recommended.

Clinical latency

The rate of clinical progression of untreated HIV is variable. The majority of people with HIV infection are asymptomatic for a substantial but variable length of time. However, the virus continues to replicate and the person is infectious. Most people with HIV have a gradual decline in CD4 count over a period of approximately 10 years before progression to symptomatic disease or AIDS. Others progress much more rapidly, with continued high levels of viral RNA and a rapid decline in CD4 count over 2–5 years. Other long-term non-progressors may continue with a normal CD4 count over many years. Within this group, a small sub-population of elite controllers maintain a viral load <2000 copies/mL or even undetectable levels without therapy.

Older age is associated with more rapid progression. Gender and pregnancy per se do not appear to influence the rate of progression, although women may fare less well for a variety of reasons. A subgroup of patients with asymptomatic infection have persistent generalized lymphadenopathy (PGL), defined as lymphadenopathy (>1 cm) at two or more extra-inguinal sites for more than 3 months in the absence of causes other than HIV infection. The nodes are usually symmetrical, firm, mobile and non-tender. There may be associated splenomegaly. The architecture of the nodes shows hyperplasia of the follicles and proliferation of the capillary endothelium. Biopsy is rarely indicated. Similar disease progression has been noted in asymptomatic patients with or without PGL. Nodes may disappear with disease progression.

Symptomatic HIV infection

As HIV infection progresses, the viral load rises, the CD4 count falls and the patient develops an array of symptoms and signs. The clinical picture is the result of direct HIV effects and of the associated immunosuppression.

In an individual patient, the clinical consequences of HIV-related immune dysfunction will depend on at least three factors:

• The microbial exposure of the patient throughout life. Many clinical episodes represent reactivation of previously acquired infection, which has been latent. Geographical factors determine the microbial repertoire of an individual patient. Those organisms requiring intact cell-mediated immunity for their control are most likely to cause clinical problems.

• The pathogenicity of organisms encountered. High-grade pathogens, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Candida and the herpesviruses, are clinically relevant, even when immunosuppression is mild, and will thus occur earlier in the course of the disease. Less virulent organisms occur at later stages of immunodeficiency.

• The degree of immunosuppression of the host. When patients are severely immunocompromised (CD4 count <100 cells/mm3), disseminated infections with organisms of very low virulence, such as M. avium-intracellulare (MAI) and Cryptosporidium, are able to establish themselves. These infections are very resistant to treatment, mainly because there is no functioning immune response to clear organisms. This hierarchy of infection allows for appropriate intervention with prophylactic drugs.

End-organ effects of HIV

Neurological disease

Neurological disease

Infection of the nervous tissue occurs at an early stage but clinical neurological involvement increases as HIV advances. This includes AIDS dementia complex (ADC), sensory polyneuropathy and aseptic meningitis (see p. 866). These conditions are much less common since the introduction of ART. The pathogenesis is thought to be due both to the release of neurotoxic products by HIV itself and to cytokine abnormalities secondary to immune dysregulation.

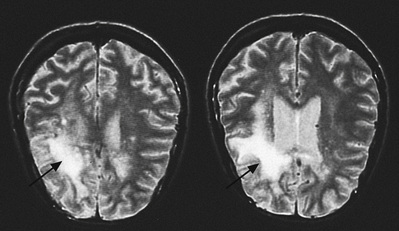

ADC has varying degrees of severity, ranging from mild memory impairment and poor concentration through to severe cognitive deficit, personality change and psychomotor slowing. Changes in affect are common and depressive or psychotic features may be present. The spinal cord may show vacuolar myelopathy histologically. In severe cases, computed tomography (CT) scanning of the brain shows atrophic change of varying degrees. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) changes consist of white matter lesions of increased density on T2-weighted sections. Electroencephalography (EEG) shows non-specific changes consistent with encephalopathy. The CSF is usually normal, although the protein concentration may be raised. Patients with mild neurological dysfunction may be unduly sensitive to the effects of other insults, such as fever, metabolic disturbance or psychotropic medication, any of which may lead to a marked deterioration in cognitive functioning.

Sensory polyneuropathy is seen in advanced HIV infection, mainly in the legs and feet, although hands may be affected. Severe forms cause intense pain, usually in the feet, which disrupts sleep, impairs mobility and generally reduces the quality of life.

Autonomic neuropathy may also occur with postural hypotension and diarrhoea. Autonomic nerve damage is found in the small bowel.

ARVs that penetrate the central nervous system (CNS) can lead to significant improvements in cognitive function in many patients with ADC. They may also have a neuroprotective role.

Eye disease

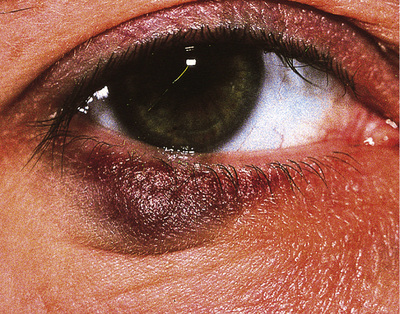

Eye disease

Eye pathology may occur in the later stages. The most serious condition is cytomegalovirus retinitis (see p. 258), which is sight-threatening. Retinal cotton wool spots due to HIV per se are rarely troublesome but they can be confused with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Anterior uveitis can present as acute red eye associated with rifabutin therapy for mycobacterial infections in HIV. Steroids used topically are usually effective but modification of the dose of rifabutin is required to prevent relapse. Pneumocystis, toxoplasmosis, syphilis and lymphoma can all affect the retina and the eye may be the site of first presentation.

Mucocutaneous manifestations

Mucocutaneous manifestations

The skin is a common site for HIV-related pathology (Box 12.11), as the function of dendritic and Langerhans cells, both target cells for HIV, is disrupted. Delayed-type hypersensitivity, a good indicator of cell-mediated immunity, is frequently reduced or absent, even before clinical signs of immunosuppression appear. Pruritus is a common complaint at all stages of HIV. Generalized dry, itchy, flaky skin is typical and the hair may become thin and dry. An intensely pruritic papular eruption favouring the extremities may be found, particularly in patients from African backgrounds. Eosinophilic folliculitis presents with urticarial lesions, particularly on the face, arms and legs.

Drug reactions with cutaneous manifestations are frequent, rashes developing notably to sulphur-containing drugs, amongst others (see Fig. 31.52 ). Recurrent aphthous ulceration, which is severe and slow to heal, may impair the patient's ability to eat. Biopsy may be indicated to exclude other causes of ulceration. Topical steroids are useful and resistant cases may respond to thalidomide. In addition to the above, the skin is a common site of opportunistic infections (see pp. 1384–1385).

Haematological complications

Haematological complications

These are common in advanced HIV infection.

• Lymphopenia progresses as the CD4 count falls.

• Anaemia of chronic HIV infection is usually mild, normochromic and normocytic.

• Neutropenia is common and usually mild.

• Isolated thrombocytopenia may occur early in infection and be the only manifestation of HIV for some time. Platelet counts are often moderately reduced but can fall dramatically to 10–20 × 109/L, producing easy bleeding and bruising. Circulating antiplatelet antibodies lead to peripheral destruction. Megakaryocytes are increased in the bone marrow but their function is impaired. Effective ART usually produces a rise in platelet count. Thrombocytopenic patients undergoing dental, medical or surgical procedures may need therapy with human immunoglobulin, which gives a transient rise in platelet count, or with platelet transfusion. Steroids are best avoided.

• Pancytopenia occurs because of underlying opportunistic infection or malignancies, in particular M. avium-intracellulare, disseminated cytomegalovirus and lymphoma.

• Other complications involve myelotoxic drugs, which include zidovudine (megaloblastic anaemia, red cell aplasia, neutropenia), lamivudine (anaemia, neutropenia), ganciclovir (neutropenia), systemic chemotherapy (pancytopenia) and co-trimoxazole (agranulocytosis).

Gastrointestinal effects

Gastrointestinal effects

Weight loss and diarrhoea are common in people with advanced untreated HIV infection (see Box 13.19). Wasting is a common feature of advanced HIV infection, which, although originally attributed to direct HIV effects on metabolism, is usually a consequence of anorexia. There is a small increase in resting energy expenditure in all stages of HIV, but weight and lean body mass usually remain normal during periods of clinical latency when the patient is eating normally.

HIV enteropathy with varying degrees of villous atrophy has been described with chronic diarrhoea when no other pathogen has been found.

Hypochlorhydria is reported in patients with advanced HIV disease and may have consequences for drug absorption and bacterial overgrowth in the gut.

Rectal lymphoid tissue cells are the targets for HIV infection during penetrative anal sex and may be a reservoir for infection to spread through the body.

Renal complications

Renal complications

HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN; see p. 737), although rare, can cause significant renal impairment, particularly in more advanced disease. It is most frequently seen in black male patients and can be exacerbated by heroin use.

Nephrotic syndrome subsequent to focal glomerulosclerosis is the usual pathology, which may be a consequence of HIV cytopathic effects on renal tubular epithelium. The course is usually relentlessly progressive and dialysis may be required.

Many nephrotoxic drugs are used in the management of HIV-associated pathology, particularly foscarnet, amphotericin B, pentamidine and sulfadiazine. Tenofovir is associated with Fanconi syndrome (see p. 1286).

Respiratory complications

Respiratory complications

The upper airway and lungs serve as a physical barrier to air-borne pathogens and any damage will decrease the efficiency of protection, leading to an increase in upper and lower respiratory tract infections. The sinus mucosa may also function abnormally in HIV infection and is frequently the site of chronic inflammation. Response to antibacterial therapy and topical steroids is usual but some patients require surgical intervention. A similar process is seen in the middle ear, which can lead to chronic otitis media.

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis (LIP) is well described in paediatric HIV infection but is uncommon in adults. There is an infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells and lymphoblasts in alveolar tissue. Epstein–Barr virus may be present. The patient presents with dyspnoea and a dry cough, which may be confused with pneumocystis infection (see p. 349). Reticular nodular shadowing is seen on chest X-ray. Therapy with steroids may produce clinical and histological benefit in some patients.

Endocrine complications

Endocrine complications

Various endocrine abnormalities have been reported, including reduced levels of testosterone and abnormal adrenal function. The latter assumes clinical significance in advanced disease when intercurrent infection superimposed on borderline adrenal function precipitates clear adrenal insufficiency, requiring replacement doses of gluco- and mineralocorticoid. Cytomegalovirus is also implicated in adrenal-deficient states.

Cardiac complications

Cardiac complications

Cardiovascular pathology is increasingly recognized as a cause of morbidity in people with HIV. Although lipid dysregulation has been associated with ARV medication, the observation has been made that high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels are lower in those with untreated HIV infection than in HIV-negative controls. In a large international study (SMART), ischaemic heart disease was more common in those who took intermittent ARV therapy than in those who maintained viral suppression. Cardiomyopathy, although rare, is associated with HIV and may lead to congestive cardiac failure. Lymphocytic and necrotic myocarditis has been described. Ventricular biopsy should be performed to ensure that other treatable causes of myocarditis are excluded.

Conditions associated with HIV immunodeficiency

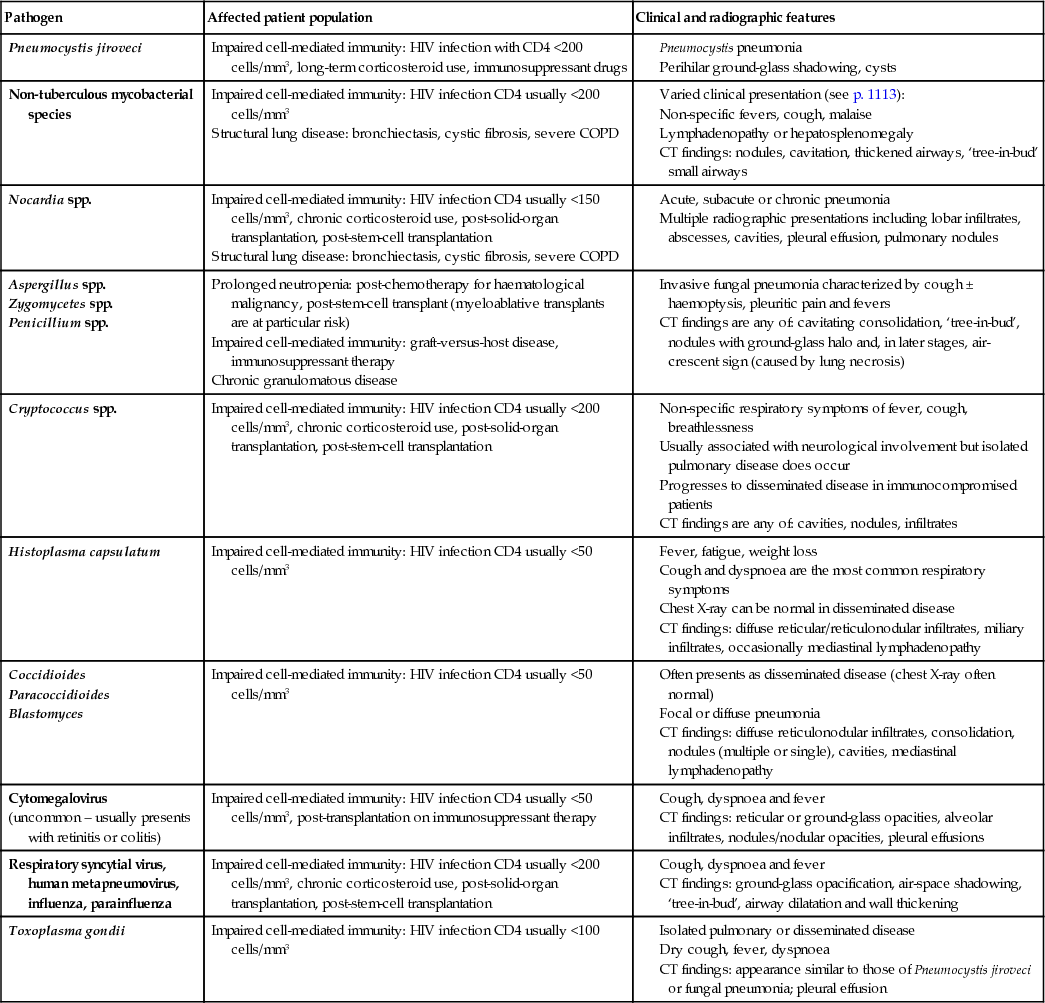

Immunodeficiency (see pp. 138–142) allows the development of opportunistic infections (Box 12.12 and see also Box 12.21). These are diseases caused by organisms that are not usually considered pathogenic, unusual presentations of known pathogens, and the occurrence of tumours that may have an oncogenic viral aetiology. Susceptibility increases as the patient becomes more immunosuppressed. CD4 T-lymphocyte numbers are used as markers to predict the risk of infection. Patients with CD4 counts of >200 cells/mm3 are at low risk for the majority of AIDS-defining opportunistic infections. A hierarchy of thresholds for specific infectious risks can be constructed. Mechanisms include defective T-cell function against protozoa, fungi and viruses, impaired macrophage function against intracellular bacteria such as Mycobacteria and Salmonella, and defective B-cell immunity against capsulated bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus. Many of the organisms causing clinical disease are ubiquitous in the environment or are already carried by the patient.

Diagnosis in an immunosuppressed patient may be complicated by a lack of typical signs, as the inflammatory response is impaired. Examples are lack of neck stiffness in cryptococcal meningitis or minimal clinical findings in early Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia. Multiple pathogens may coexist. Indirect serological tests are frequently unreliable. Specimens should be obtained from the appropriate site for examination and culture in order to make a diagnosis.

Assessment and monitoring of HIV-positive patients

Initial assessment

People are newly diagnosed with HIV in an increasingly wide range of settings and need to be transferred appropriately into effective care. All those with a new diagnosis of HIV should be reviewed by an HIV clinician within 2 weeks of diagnosis, or earlier if the patient is symptomatic or has other acute needs. A full medical history, physical examination and laboratory evaluation should be undertaken in all newly diagnosed patients to determine the stage of infection and the presence of co-morbidities and co-infections, and to assess overall physical, mental and sexual health. The initial assessment should also include details of the patient's socioeconomic situation, relationships, family and social support networks, and substance misuse, together with contact tracing and partner notification. Specialist advice should be sought if there are children who require testing. Baseline investigations will depend on the clinical setting, but those appropriate for an asymptomatic person in the UK are shown in Box 12.13.

Monitoring

Patients are regularly monitored, depending on infection and treatment stage.

For people who are not yet on therapy, monitoring should take place 2–4 times per year, with longer intervals for those with higher CD4 counts, to assess progression of the infection and the need for treatment. Decisions about appropriate intervention can be made.

For people starting therapy and those on established effective therapy, monitoring is described in on page 344.

Immunological monitoring

CD4 lymphocytes. The absolute CD4 count and its percentage of total lymphocytes fall as HIV progresses. These figures bear a relationship to the risk of occurrence of HIV-related pathology, and patients with counts <200 cells/mm3 are at greatest risk. Rapidly falling CD4 counts and those at or below 350 are an indication for immediate initiation of ART. Factors other than HIV (e.g. smoking, exercise, intercurrent infections and diurnal variation) also affect CD4 numbers. CD4 counts are performed at approximately 4–6-monthly intervals unless values are approaching critical levels for intervention, in which case they are performed more frequently.

Virological monitoring

Viral load (HIV RNA). HIV replicates at a high rate throughout the course of infection, many billions of new virus particles being produced daily. The rate of viral clearance is relatively constant in any individual and thus the level of viraemia is a reflection of the rate of virus replication. This has both prognostic and therapeutic value.

The commonly used term ‘viral load’ encompasses viraemia and HIV RNA levels. Three HIV RNA assays for viral load are in current use:

Results are given in copies of viral RNA/mL of plasma, or converted to a logarithmic scale, and there is good correlation between tests. The most sensitive test is able to detect as few as 20 copies of viral RNA/mL. Transient increases in viral load are seen following immunizations (e.g. for influenza and Pneumococcus) or during episodes of acute intercurrent infection (e.g. tuberculosis), and viral load measurements should not be carried out within a month of these events.

By about 6 months after seroconversion to HIV, the viral set-point for an individual is established and there is a correlation between HIV RNA levels and long-term prognosis, independent of the CD4 count. Those patients with a viral load consistently >100 000 copies/mL have a 10 times higher risk of progression to AIDS over the ensuing 5 years than those consistently <10 000 copies/mL.

HIV RNA is the standard marker of treatment efficacy (see below). Both duration and magnitude of virus suppression are pointers to clinical outcome. The aim of therapy is to secure long-term virological suppression, and a rising viral load in a patient whose adherence is assured indicates drug failure.

Baseline measurements are followed by repeat estimations at intervals of 4–6 months, ideally in conjunction with CD4 counts, to allow both pieces of evidence to be used together in decision-making. Following initiation of ART or changes in therapy, a reduction in viral load should be seen by 4 weeks, reaching a maximum at 10–12 weeks, when repeat viral load testing should be carried out (see Fig. 12.12).

Genotype determination

Clear genotype variations exist within HIV; not only are there variations between viral subtypes but also well-identified point mutations are associated with resistance to ARVs. New infections with drug-resistant variants of HIV may be seen. Viral genotype analysis is recommended for all newly diagnosed patients with HIV. The most appropriate sample is the one closest to the time of diagnosis and the results are used to guide the selection of ART agents.

Management of HIV-Positive Patients

Effective ART has transformed the clinical outcomes for people with HIV, extending life expectancy towards that of the general population, bringing down morbidity and cutting infectiousness to people who are HIV-negative. Current management strategies aim to maximize wellbeing with long-term, effective suppressive therapy within a chronic condition model, beginning before the patient is symptomatic (Box 12.14). The treatment of opportunistic conditions in immunosuppressed patients is most commonly seen either in situations where ART is not available or in previously undiagnosed patients presenting with advanced infection. With access and adherence to potent, tolerable ARVs within a managed clinical setting, life expectancy for people with HIV can approach that of the general population. Nevertheless, there is still no cure for HIV and patients live with a chronic, potentially infectious and unpredictable condition. Limitations on ART efficacy include the inability of existing drugs to clear HIV from certain intracellular pools, the occurrence of drug side-effects, adherence requirements, complex drug–drug interactions and the emergence of resistant viral strains. Even with complete viral suppression, ART does not fully restore health, and treated infection is associated with a variety of non-AIDS complications, including cardiovascular disease and some cancers.

The aims of management in HIV infection are to:

• maintain physical and mental health

• restore and improve immune function

This requires long-term, maximal suppression of HIV activity using ARV medication and management adopting a multidisciplinary team approach. Regular assessment is needed to obtain details of intercurrent medical problems, medications, vaccinations, any recreational drug use, sexual history, reproductive decision-making, cervical cytology, and social situation to include support networks, employment, benefits and accommodation. Depression and anxiety are common among people living with HIV and can have a deleterious impact on adherence to medication regimens, making it important for mood and cognitive function to be routinely and regularly assessed. Psychological support may be needed, not only for the patient but also for family, friends and carers. Regular reviews of sexual and reproductive health, together with advice on reducing the risk of HIV transmission, must be provided and future sexual practices discussed. Information is required to allow people to make informed choices about childbearing. The implications for sexual partners and existing family members should be considered and diagnostic testing offered as necessary. Regular monitoring of weight, body mass index, blood pressure and cardiovascular risk is required. Dietary assessment and advice should be freely accessible. General health promotion advice on smoking, alcohol, diet, drug misuse and exercise should be given, particularly in light of the cardiovascular, metabolic and hepatotoxicity risks associated with HIV and its treatment.

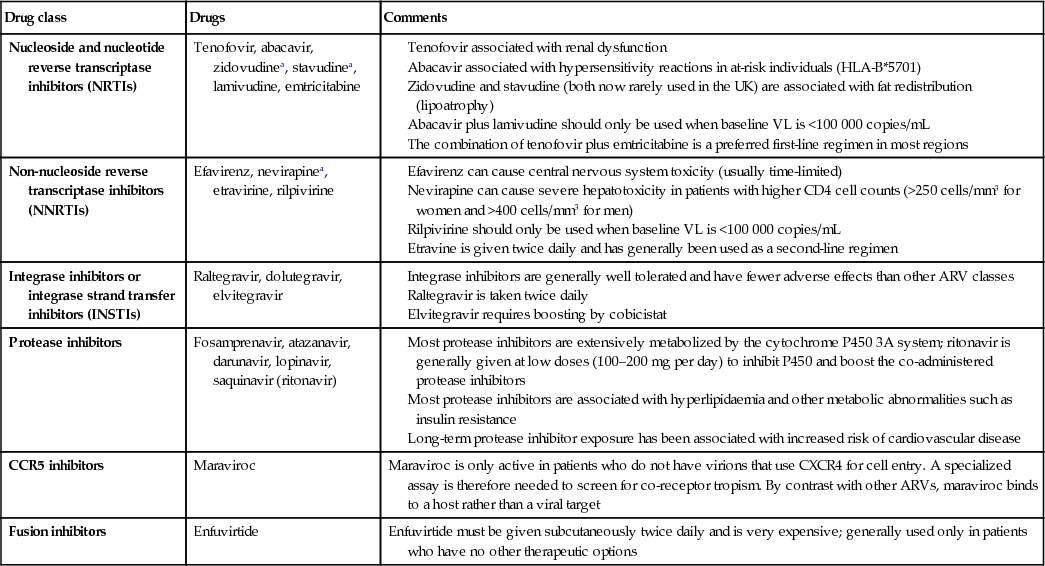

Anti-retroviral drugs

The treatment of HIV using anti-retroviral therapy (ART; Box 12.15) continues to evolve and improve. Increased potency, reduced toxicity, greater convenience of formulation, and availability of compounds with different mechanisms of action, coupled with an improved understanding of drug resistance, have combined to improve HIV clinical and virological outcomes consistently. An increase in the numbers of compounds, and the array of drug–drug interactions, for example, combine to make HIV treatment complex, and better clinical outcomes have been linked closely to physician expertise and the numbers of patients under direct care. With several of the older compounds now available as generics, some drug costs are likely to fall, and commissioners are increasingly focusing on the cost-effectiveness of the newer agents to justify their use. Regularly updated treatment guidelines are produced in the UK by the British HIV Association and in the USA by the Department of Health and Human Services. The most up-to-date versions can be found on their websites (see ‘Further reading’) and the current version must be used.

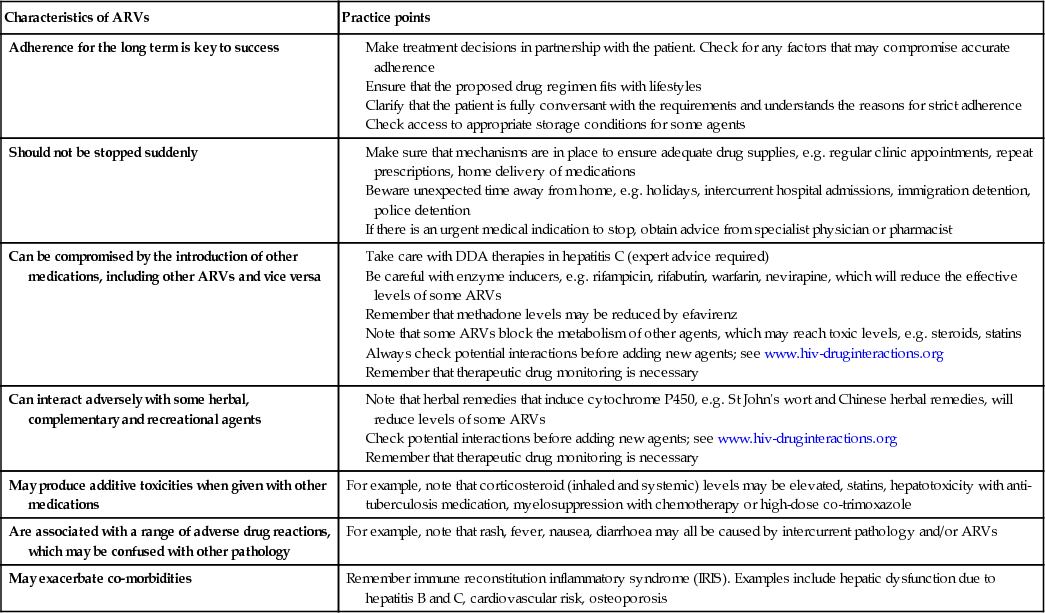

The key practical principles of prescribing ARVs are given in Box 12.16.

Reverse transcriptase inhibitors

Nucleoside/nucleotide analogues

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) inhibit the synthesis of DNA by reverse transcription and also act as DNA chain terminators. NRTIs need to be phosphorylated intracellularly for activity to occur. These were the first group of agents to be used against HIV. Usually, two drugs of this class are combined to provide the ‘backbone’ of an ART regimen. Several fixed-dose NRTI combinations are available, which helps reduce the pill burden. NRTIs have been associated with mitochondrial toxicity (see p. 346), a consequence of their effect on the human mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Lactic acidosis is a recognized complication of the older members this group of drugs. Nucleotide analogues (nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors, NtRTIs) have a similar mechanism of action but require only two intracellular phosphorylation steps for activity (as opposed to the three steps for nucleoside analogues).

Non-nucleoside analogues

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) interfere with reverse transcriptase by direct binding to the enzyme. They are generally small molecules that are widely disseminated throughout the body and have a long half-life. NNRTIs affect cytochrome P450. They are ineffective against HIV-2. The level of cross-resistance across the class is very high. All have been associated with rashes and elevation of liver enzymes. Second-generation NNRTIs, such as etravirine and rilpivirine, which have fewer adverse effects, have some activity against viruses resistant to other compounds of the NNRTI class.

Protease inhibitors

Protease inhibitors (PIs) act competitively on the HIV aspartyl protease enzyme, which is involved in the production of functional viral proteins and enzymes. As a consequence, viral maturation is impaired and immature dysfunctional viral particles are produced. Most of the PIs are active at very low concentrations and in vitro are found to have synergy with reverse transcriptase inhibitors. However, there are differences in toxicity, pharmacokinetics, resistance patterns and also cost, which influence prescribing. Cross-resistance can occur across the PI group. There appears to be no activity against human aspartyl proteases (e.g. renin), although there are clinically significant interactions with the cytochrome P450 system. This is used to therapeutic advantage, ‘boosting’ blood levels of PI by blocking drug breakdown with small doses of ritonavir or cobicistat. PIs have been linked with abnormalities of fat metabolism and control of blood sugar, and some have been linked with deterioration in clotting function in people with haemophilia. In general, PIs have a higher genetic barrier to resistance than other drug classes, and newer PIs such as darunavir have activity against viruses resistant to the older drugs in the class.

Integrase inhibitors

These drugs act as a selective inhibitor of HIV integrase, which blocks viral replication by preventing insertion of HIV DNA into the human DNA genome. Three compounds are in clinical use and are effective in treatment of both drug-experienced and drug-naive patients, with tolerability and safety profiles that are superior to those of NNRTIs and PIs. For these reasons, dolutegravir, a second-generation integrase inhibitor, has been shown to be superior to both efavirenz and darunavir, and also has a high genetic barrier to resistance.

Co-receptor blockers

Maraviroc is a chemokine receptor antagonist that blocks the cellular CCR5 receptor entry by CCR5 tropic strains of HIV. These strains are found in earlier HIV infection and, with time adaptations (against which maraviroc is ineffective), allow the CXCR4 receptor to become the more dominant form. The drug is metabolized by cytochrome P450 (3A), giving the potential for drug–drug interactions. Tropism assays to establish that the patient is carrying a CCR5 tropic virus are required before treatment is used.

Fusion inhibitors

Enfuvitide is the only licensed compound in this class of agents. It is an injectable peptide derived from HIV gp41 that inhibits gp41-mediated fusion of HIV with the target cell. It is synergistic with NRTIs and PIs. Although resistance to enfuvitide has been described, there is no evidence of cross-resistance with other drug classes. Because it has an extracellular mode of action there are few drug–drug interactions. Side-effects relate to the subcutaneous route of administration in the form of injection site reactions.

Starting therapy

Although the benefits of ART in HIV infection are indisputable, treatment regimens require a long-term commitment to high levels of adherence. Risks of therapy include short- and longer-term side-effects, drug–drug interactions and the potential for development of resistant viral strains, although, with newer agents and improved formulations, the difficulties associated with treatment have diminished. The full involvement of patients in therapeutic decision-making is essential for success. Various national guidelines and treatment frameworks exist (e.g. guidelines from BHIVA, guidelines from the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), recommendations from the International Antiviral Society (IAS)). Laboratory marker data, including viral load, genotype and CD4 counts, together with individual circumstances, underpin therapeutic decision-making. The current UK recommendations are shown in Box 12.17. In situations where therapy is recommended but the patient elects not to start, then more intensive clinical and laboratory monitoring is advisable.

Questions still remain about the best time to start therapy. Unequivocal clinical benefit has been demonstrated with the use of ARVs in advanced HIV disease. In all patients with symptomatic HIV disease, HIV-related co-morbidity, AIDS or a CD4 count that is consistently <200 cells/mm3, treatment should be initiated as soon as possible. In such situations, there is a significant risk of serious HIV-associated morbidity and mortality, and the longer-term prognosis for patients initiating therapy <200 cells/mm3 is not as good as for those who start at higher counts.

In asymptomatic patients, the absolute CD4 count is the key investigation used to guide treatment decisions. The UK recommendation is that therapy should be started at or around a CD4 count of 350 cells/mm3. Treatment should not be delayed if the CD4 count is close to this threshold.

Debate persists around starting therapy at higher CD4 counts. The risk of disease progression for individuals with a count >350 cells/mm3 is low and has to be balanced against ARV therapy toxicity and the development of resistance. However, there is growing appreciation of the long-term inflammatory effects of HIV that predispose to non-AIDS illnesses, which, together with the reduction in infectiousness for those on effective therapy, is shifting opinion towards starting sooner. Earlier intervention at higher CD4 counts may be considered in those with a higher risk of disease progression: for example, with high viral loads (>60 000 copies/mL) or rapidly falling CD4 count (losing more than 80 cells/year). Co-infection with hepatitis B and C virus may be an indication for earlier intervention (see p. 351). Patients with primary HIV infection and neurological involvement, an AIDS-defining illness or a CD4 count <350 cells/mm3 should start therapy, which should be continued indefinitely. Special situations (seroconversion, pregnancy, post-exposure prophylaxis) in which ARV agents may be used are described on pages 346–347.

The evidence that treatment reduces infectiousness should be discussed with all patients with HIV; those who wish to start treatment to reduce the risk of transmission to others should do so, irrespective of CD4 count.

Choice of drugs

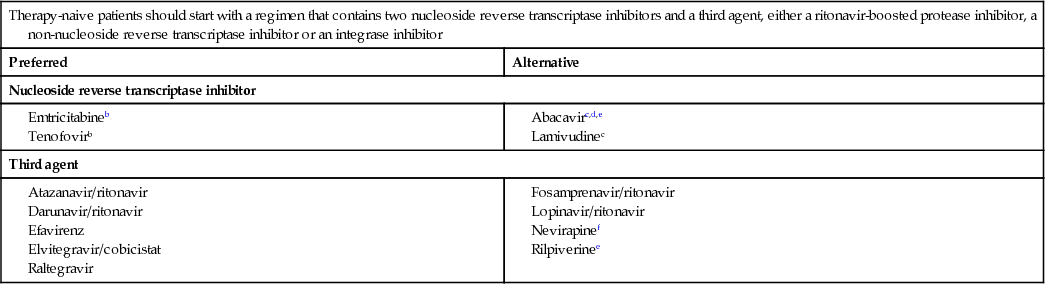

The drug regimen used for starting therapy must be individualized to suit each patient's needs. As differences in drug efficacy become less marked, tailoring treatment to the patient's needs and lifestyle is key to success. Treatment is initiated with three drugs: two NRTIs in combination, with a third agent – either an NNRTI, a boosted PI or an integrase inhibitor (Boxes 12.15 and 12.18). The development of fixed-dose co-formulations reduces pill burden, increases convenience and facilitates adherence.

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

The choice of two NRTIs to form the backbone of therapy is influenced by efficacy, toxicity and ease of administration. The availability of once-daily, one-tablet, fixed-dose combinations, Truvada (tenofovir/emtricitabine) and Kivexa (abacavir/lamivudine), has led to the prescription of one of these as the two-NRTI backbone for the majority of patients who are naive to medication. Kivexa should be used only in those who are HLA-B*5701-negative. Data comparing Truvada and Kivexa in naive patients have demonstrated the non-inferiority of Kivexa at viral levels <100 000 copies/mL. In patients with high viral levels, Kivexa should be reserved for use when Truvada is contraindicated.

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

The decision about whether to use an NNRTI, a boosted PI or an integrase inhibitor will depend on the particular circumstances of each patient. In the UK, however, an NNRTI-based regimen is still the most commonly prescribed for patients starting treatment.

Efavirenz is the recommended option in the UK, having demonstrated good durability over time, and potency at low CD4 counts and in high viral loads. It is associated with CNS side-effects, such as dysphoria and insomnia. Rilpivirine has fewer side-effects and is better tolerated than efavirenz, but is less effective when the viral load is >100 000 copies/mL, making it an alternative rather than a preferred first-line drug. Single-tablet, fixed-dose preparation of efavirenz co-formulated with Truvada (Atripla) and rilpivirine with Truvada (Eviplera) allows for a ‘one pill once a day’ regimen.

Nevirapine is of equivalent potency to efavirenz but has a higher incidence of hepatotoxicity and rash. Toxicity is greater in women and in those with higher CD4 counts. It is contraindicated in women with CD4 counts >250 cells/mm3 and in men with counts >400 cells/mm3. It can be a useful alternative to efavirenz if CNS side-effects are troublesome, and in women with lower CD4 counts who wish to conceive.

Etravirine is a second-generation NNRTI with some activity against drug-resistant strains, and is useful in the treatment of experienced patients.

Protease inhibitors

This class of drugs has demonstrated excellent efficacy in clinical practice. PIs are usually combined with a low dose of ritonavir (a ‘boosting’ PI), which provides a pharmacokinetic advantage by blocking cytochrome P450 metabolism. If this approach is used, the half-life of the active drug is increased, allowing greater drug exposure, fewer pills, enhanced potency and a minimized risk of resistance. The disadvantages include a greater pill burden and increased risk of greater lipid abnormalities, particularly raised fasting triglycerides. Cobicistat, a novel cytochrome P450 inhibitor with no intrinsic anti-HIV activity, is an alternative.

Atazanavir, darunavir and lopinavir, boosted with ritonavir, are most commonly used as first-line therapy. All three can cause gastrointestinal disturbance and lipid abnormalities. Atazanavir increases unconjugated bilirubin levels and may produce icterus. All have interactions with cytochrome P450.

Integrase inhibitors

The potency of this class of drug, coupled with the relatively favourable side-effect profile in comparison to efavirenz and fewer drug interactions in comparison to PIs, makes it an increasingly popular third agent.

Raltegravir, the first licensed compound in this drug class, has high anti-HIV activity for both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients, with a favourable side-effect profile and few drug interactions. The genetic barrier for resistance is relatively low, twice daily dosing is required and there are no single-tablet co-formulations available.

Elvitegravir is metabolized via the cytochrome P450 pathway, requiring co-administration of a cytochrome-P450 blocker to secure adequate plasma concentrations, thus increasing the drug–drug interaction potential. Single-tablet co-formulations exist with tenofovir, emtricitabine and cobicistat (Stribild). Dolutegravir, a second-generation integrase inhibitor with a good side-effect profile, has a higher genetic barrier to resistance than raltegravir and can be dosed once daily. A fixed-dose tablet of dolutegravir co-formulated with abacavir and lamivudine has recently been approved.

Monitoring therapy

Success rates for initial therapy using modern ARVs, as judged by virological response, are very high. By 4 weeks of therapy, the viral load should have dropped by at least 1 log10 copies/mL and by 12–24 weeks should be below 50 copies/mL. A suboptimal response at either time point demands a full assessment and possible change in therapy. Once stable on therapy, the viral load should be routinely measured every 3–6 months. CD4 count should be repeated at 1 and 3 months after starting ART and then every 3–4 months. Once the viral load is <50 copies/mL and the CD4 count has been <350 cells/mm3 for at least 12 months, monitoring frequency may fall to 6-monthly or even longer (Box 12.19). Impaired immunological recovery is associated with treatment initiation in advanced infection (a low CD4 count and late presentation) and with older age.

Regular clinical assessment should include review of adherence to, and tolerability of, the regimen, weight, blood pressure and urinalysis. Patients should be monitored for drug toxicity, including full blood count, liver and renal function, and fasting lipids and glucose levels.

Drug resistance

Resistance to ARVs (Box 12.20) results from mutations in the protease reverse transcriptase and integrase genes of the virus. HIV has a rapid turnover, with 108 replications occurring per day. The error rate is high, resulting in genetic diversity within the population of virus in an individual, which will include drug-resistant mutants. When drugs only partially inhibit virus replication, there will be a selection pressure for the emergence of drug-resistant strains. The rate at which resistance develops depends on the frequency of pre-existing variants and the number of mutations required. Resistance to most NRTIs and PIs occurs with an accumulation of mutations, whilst a single-point mutation will confer high-level resistance to NNRTIs. There is evidence for the transmission of HIV strains that are resistant to all or some classes of drugs. Studies of primary HIV infection have shown prevalence rates of between 2% and 20%. Prevalence of primary mutations associated with drug resistance in chronically infected patients not on treatment ranges from 3% to 10% in various studies.

HIV anti-retroviral drug resistance testing has become routine clinical management in patients at diagnosis/before starting therapy and for whom therapy is failing. The tests are based on PCR amplification of virus and give an indirect measure of drug susceptibility in the predominant variants. Such assays are limited by both the starting concentration of virus and their ability to detect minority strains.

For results to be useful in situations where therapy is failing, samples must be analysed when the patient is on therapy, as once the selection pressure of therapy is withdrawn, wild-type virus becomes the predominant strain and resistance mutations present earlier may no longer be detectable.

Databases containing nearly all published HIV (amongst others) and protease sequences and associated resistance patterns are maintained in real time by Stanford University (see ‘Further reading’).

Phenotypic assays provide a more direct measure of susceptibility but the complexity of the assays limits availability.

Drug interactions

Drug therapy in HIV is complex and the potential for clinically relevant drug interactions is substantial. Both Pls and NNRTIs are able to inhibit and induce cytochrome P450 variably, influencing both their own metabolic rates and those of other drugs. Both inducers and inhibitors of cytochrome P450 are sometimes prescribed simultaneously. Induction of metabolism may result in sub-therapeutic ARV levels with the risk of treatment failure and development of viral resistance, whilst inhibition can raise drug levels to toxic values and precipitate adverse reactions.

Conventional (e.g. rifamycins) and complementary therapies (e.g. St John's wort) affect cytochrome P450 activity and may precipitate substantial drug interactions. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), indicating peak and trough plasma levels, may be useful in certain settings.

Potential interactions can be checked using the online tool maintained by Liverpool University (see ‘Further reading’).

Adherence

Patients' beliefs about their personal need for medicines and their concerns about treatment affect how and whether they take them. Adherence to treatment is pivotal to success. Levels of adherence below 95% have been associated with poor virological and immunological responses, although some of the newer ARVs are more forgiving. Poor absorption and low bioavailability mean that, for some compounds, trough levels are barely adequate to suppress viral replication, and missing even a single dose will result in plasma drug levels falling dangerously low. Patchy adherence facilitates the emergence of drug-resistant variants, which, in time, will lead to virological treatment failure.

Factors implicated in poor adherence may be associated with the medication, with the patient or with the provider. The former include side-effects linked with medications, the degree of complexity and pill burden, and inconvenience of the regimen. Patient factors include the level of motivation and commitment to the therapy, psychological wellbeing, the level of available family and social support, and health beliefs. Supporting adherence is a key part of clinical care and specific guidelines are available (BHIVA 2004). Education of patients about their condition and treatment is a fundamental requirement for good adherence, as is education of clinicians in adherence support techniques. The acceptability and tolerability of the regimen, together with an assessment of adherence, should be documented at each visit. Provision of acute and ongoing multidisciplinary support for adherence within clinical settings should be universal. Medication-alert devices may be useful for some patients.

Treatment failure

Failure of ART – that is, persistent viral replication causing immunological deterioration and eventual clinical evidence of disease progression – is caused by a variety of factors, such as poor adherence, limited drug potency, and food or other medication that may compromise drug absorption. There may be drug interactions or limited penetration of drug into sanctuary sites such as the CNS, permitting viral replication. Side-effects and other patient-related elements contribute to poor adherence.

Changing therapy

A rise in viral load, a falling CD4 count or new clinical events that imply progression of HIV disease are all reasons to review therapy. Reasons for treatment failure include the emergence of resistant viral strains, poor patient adherence and intolerance/adverse drug reactions. Virological failure – that is, two consecutive viral loads of >400 copies/mL in a previously fully suppressed patient – requires investigation. Viral genotyping should be used to help select future therapy, choosing at least two new agents to which the virus is fully sensitive. If a new suitable treatment option is available, it should be started as soon as possible.

Treatment failure in highly treatment-experienced patients poses considerable challenges but new classes of ARVs, with activity against drug-resistant strains of HIV, make long-term virological suppression a realistic objective, even in heavily pre-treated patients. However, in some situations, it may be better to hold back a new drug and await development of another new agent to give the maximum chance of success.

If the patient has a viral load below the limit of detection and a change needs to be made because of intolerance of a particular drug, then a switch should be made to another sensitive drug within the same class. Simplification of complex regimens may be considered if adherence is problematic.

Stopping therapy

ARVs may have to be stopped in, for example, cumulative toxicity, or when there are potential drug interactions with medications needed to deal with another more pressing problem. If adherence is poor, stopping completely may be preferable to continuing with inadequate dosing, in order to reduce the development of viral resistance. Poor quality of life and the view of the patient should be discussed.

The NRTIs efavirenz and nevirapine have long half-lives and, depending on the other components of the regimen, may need be stopped before the other drugs in the mixture to reduce the risk of drug resistance. If this is not possible, a boosted PI may be used, either as a substitute for the NNRTI or as monotherapy, for several weeks to cover the period of sub-therapeutic levels.

Complications of anti-retroviral therapy

Side-effects are a common problem in ART (see Box 12.15). Some are acute and associated with initiation of medication, whilst others emerge after longer-term exposure to drugs.

Allergic reactions

Allergic reactions occur with greater frequency in HIV infection and have been documented with all the ARVs. Abacavir is associated with a potentially fatal hypersensitivity reaction, strongly associated with the presence of HLA-B*5701, usually within the first 6 weeks of treatment. There may be a discrete rash and often a fever, coupled with general malaise and gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms. The diagnosis is clinical and symptoms resolve when abacavir is withdrawn. Re-challenge with abacavir can be fatal and is contraindicated. In the UK, routine screening for the HLA-B*5701 allele has reduced the incidence of abacavir hypersensitivity. Allergies to NNRTIs (often in the second or third week of treatment) usually present with a widespread maculopapular pruritic rash, often with a fever and disordered liver biochemical tests. Reactions can resolve, even with continuing therapy, but drugs should be stopped immediately in any patient with mucous membrane involvement or severe hepatic dysfunction.

Lipodystrophy and metabolic syndrome

A syndrome of lipodystrophy occurs in patients with HIV on ART, comprising characteristic morphological changes and metabolic abnormalities. The main characteristics include a loss of subcutaneous fat in the arms, legs and face (lipoatrophy), deposition of visceral, breast and local fat, raised total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and triglycerides, and insulin resistance with hyperglycaemia. The syndrome is potentially associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity. The highest incidence occurs in those taking combinations of NRTIs and PIs. The older drugs, stavudine and zidovudine, are associated with the lipoatrophy component of the process. Dietary advice and increase in exercise may improve some of the metabolic problems and help body shape. Statins and fibrates are recommended to reduce circulating lipids. Simvastatin is contraindicated, as it has high levels of drug interactions with PIs.

Mitochondrial toxicity and lactic acidosis

Mitochondrial toxicity, mostly involving the older drugs, stavudine and didanosine, in the nucleoside analogue class, leads to raised lactate and lactic acidosis, which has, in some cases, been fatal. NRTIs inhibit gamma-DNA polymerase and other enzymes that are necessary for normal mitochondrial function. Symptoms are often vague and insidious, and include anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain and general malaise. Venous lactate is raised and the anion gap is typically widened. This is a serious condition, requiring immediate cessation of ART and provision of appropriate supportive measures until normal biochemistry is restored. All patients should be alerted to the possible symptoms and encouraged to attend hospital promptly.

Bone metabolism

A variety of bone disorders have been reported in HIV: in particular, osteopenia, osteoporosis and avascular necrosis. The prevalence of these conditions has varied widely in different studies. ARVs, particularly PIs, have been implicated in the aetiology, although untreated HIV is believed to have a direct impact on bone metabolism.

IRIS

Paradoxical inflammatory reactions (immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, IRIS) may occur on initiating ART. This occurs usually in people who have been profoundly immunosuppressed and begin therapy. As their immune system recovers, they are able to mount an inflammatory response to a range of pathogens, which can include exacerbation of symptoms with new or worsening clinical signs. Examples include unusual mass lesions or lymphadenopathy associated with mycobacteria, including deteriorating radiological appearances associated with tuberculosis infection. Inflammatory retinal lesions in association with cytomegalovirus, deterioration in liver function in chronic hepatitis B carriers, and vigorous vesicular eruptions with herpes zoster have also been described. To avoid this situation, certain pathogens, in particular Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Cryptococcus, should be treated for several weeks to reduce the microbiological burden before ARVs are initiated.

Specific therapeutic situations

Acute seroconversion

ART in patients presenting with an acute seroconversion illness is controversial. This stage of disease may represent a unique opportunity for therapy, as there is less viral diversity and the host immune capacity is still intact. There is evidence to show that the viral load can be reduced substantially by aggressive therapy at this stage, although it rises when treatment is withdrawn. The longer-term clinical sequelae of treatment at this stage remain uncertain. People with severe symptoms during primary HIV infection may gain a clinical improvement on ARVs. If treatment is contemplated in this situation, then it should be assumed that it will be continued for the long term.

Pregnancy

In the UK, the mother-to-child HIV transmission rate is 1% for all women diagnosed prior to delivery and 0.1% for women on ART with a viral load of <50 copies/mL. Management of HIV-positive pregnant women requires close collaboration between obstetric, medical and paediatric teams. The management aim is to deliver a healthy, uninfected baby to a healthy mother without prejudicing the future treatment options of the mother. Although considerations of pregnancy must be factored into clinical decision-making, pregnancy per se should not be a contraindication to providing optimum HIV-related care for the woman. HIV-positive women are advised against breast-feeding, which doubles the risk of vertical transmission. Delivery by caesarean section reduced the risk of vertical transmission in the pre-highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) era, but if the woman is on effective ART and the labour is uncomplicated, vaginal delivery carries no additional risk. Women conceiving on an effective ART regimen should continue on their medication. For women naive to therapy who require treatment of their own HIV, whether pregnant or not, triple therapy is the regimen of choice. Risk of vertical transmission increases with viral load. Although the fetus will be exposed to more drugs, the chances of reducing the viral load, and hence preventing infection, are greatest with a potent triple therapy regimen in the mother. In this situation, treatment should start as soon as possible and continue during delivery. The baby should receive zidovudine for 4 weeks postpartum and the mother should remain on ARVs with appropriate monitoring and support.

Women who do not need treatment for themselves should be prescribed a short course of ART, initiated at the beginning of the second trimester if the baseline viral load is >30 000 HIV RNA copies/mL. Consideration should be given to starting earlier if the viral load is >100 000 HIV RNA copies/mL.

Post-exposure prophylaxis

The time taken for HIV infection to become established after exposure offers an opportunity for prevention. Animal models provide support for the use of triple ARVs for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) but there are no prospective trials to inform the best approach and each situation should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis to estimate the potential risk of infection and potential treatment benefit.

Healthcare workers may be treated following occupational exposure to HIV, as may those exposed sexually. The risk of acquisition of HIV following exposure is dependent on the risk that the source is HIV-positive (if this is unknown in a sexual exposure) and the risk of transmission of the particular exposure. PEP may be useful up to 72 hours after possible exposure. In the UK, the standard regimen is Truvada plus raltegravir, although this may be varied depending on what is known about the source. When the source patient is known to have an undetectable HIV viral load (<200 copies HIV RNA/mL), PEP is not recommended.

Treatment is given for 4 weeks and the recipient should be monitored for toxicity. The at-risk patient should be tested for established HIV infection before PEP is dispensed. Rapid point-of-care tests are particularly useful in this setting. PEP following sexual exposure should not be seen as a substitute for other methods of prevention. Pre-exposure prophylaxis is discussed on page 355.

Towards cure

Current therapy, although effective, is life-long, expensive and complex. There is increasing interest in the possibilities of a cure for HIV: either a ‘functional’ cure, which would mean long-term control of the virus without the use of drugs, or a ‘sterilizing’ cure, which would require all HIV-containing cells to be eliminated. Several reports of successful interventions exist. These include a patient with HIV infection who underwent bone marrow transplantation for acute myeloid leukaemia (the ‘Berlin Patient’), interventions very early in the course of the infection, which may allow immune function to be preserved. Ways are being explored in which latently infected T cells could be purged. The possibilities are being studied of making cells resistant to new HIV infection, using gene manipulation to alter the CCR5 receptor that mediates viral entry into the cell. Despite some early encouraging results, it is clear that there is still a very long way to go and that, at least for the moment, there is no realistic alternative to life-long ART.

Opportunistic infections in the ART era

Although effective ART has resulted in a remarkable decline in opportunistic infections in patients with HIV, not all those at risk may be either on or adhering to effective treatment. In 2009, 19% of those newly diagnosed with HIV in the UK had a CD4 count of <200 cells/mm3 at presentation, and over 25% of those living with HIV remain undiagnosed, making late presentation and opportunistic infections more likely. In parallel, the types of infection seen in the context of HIV have altered, with fewer episodes of the ‘classic’ opportunistic infections, such as Pneumocystis pneumonia and cytomegalovirus, but an increase in community-acquired infections such as Strep. pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae (Box 12.21).

Immune reconstitution with ART may produce unusual responses to opportunistic pathogens and confuse the clinical picture. Thus, prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections remains an integral part of the management of HIV infection.

Prevention of opportunistic infection in patients with HIV

Exposure to certain organisms can be avoided in those known to be HIV-positive and immunosuppressed. Attention to food hygiene will reduce exposure to Salmonella, toxoplasmosis and Cryptosporidium, and protected sexual intercourse will reduce exposure to herpes simplex virus (HSV), hepatitis B and C viruses, and papillomaviruses. Cytomegalovirus-negative patients should be given cytomegalovirus-negative blood products. Travel-related infection can be minimized with appropriate advice.

Immunization strategies

Guidance on the appropriate use of vaccines in HIV (Box 12.22) is available from BHIVA (see ‘Further reading’). Immunization may not be as effective in HIV-positive individuals.

Hepatitis A and B vaccines should be given to those without natural immunity who are at risk, particularly if there is coexisting liver pathology, such as hepatitis C.

Chemoprophylaxis

In the absence of a normal immune response, many opportunistic infections are hard to eradicate using antimicrobials and the recurrence rate is high. Primary and secondary chemoprophylaxis has reduced the incidence of many opportunistic infections. Advantages must be balanced against the potential for toxicity, drug interactions and cost, with each medication added to what are often complex drug regimens.

• Primary prophylaxis is effective in reducing the risk of Pneumocystis jiroveci, toxoplasmosis and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare.

• Primary prophylaxis is not normally recommended against cytomegalovirus, herpesviruses or fungi.

With the introduction of ART and immune reconstitution, ongoing chemoprophylaxis can be discontinued in those patients with CD4 counts that remain consistently >200 cells/mm3. In areas where effective ART may not be available, long-term secondary prophylaxis still has a role. Other less severe but recurrent infections may also warrant prophylaxis (e.g. herpes simplex, candidiasis).

Specific Conditions Associated with HIV Infection

Fungal infections

Pneumocystis jiroveci infection

Pneumocystis jiroveci infection

Pneumocystis jiroveci most commonly causes pneumonia (PCP; see p. 1106) but can cause disseminated infection. It is not usually seen until patients are severely immunocompromised with a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3. The introduction of effective ART and primary prophylaxis in patients with CD4 counts of <200 cells/mm3 has significantly reduced the incidence in the UK. The organism damages alveolar epithelium, which impedes gas exchange and reduces lung compliance.

The onset is often insidious over a period of weeks, with a prolonged period of increasing shortness of breath (usually on exertion), non-productive cough, fever and malaise. Clinical features on examination include tachypnoea, tachycardia, cyanosis and signs of hypoxia. Fine crackles are heard on auscultation, although in mild cases there may be no auscultatory abnormality. In early infection, the chest X-ray is normal but the typical appearances are of bilateral perihilar interstitial infiltrates, which can progress to confluent alveolar shadows throughout the lungs. High-resolution CT scans of the chest demonstrate a characteristic ground-glass appearance, even when there is little to see on the chest X-ray. The patient is usually hypoxic and desaturates on exercise. Definitive diagnosis rests on demonstrating the organisms in the lungs via bronchoalveolar lavage or by PCR amplification of the fungal DNA from a peripheral blood sample. As the organism cannot be cultured in vitro, it must be directly observed either with silver staining or with immunofluorescent techniques.

Treatment should be instituted as early as possible. First-line therapy is with intravenous co-trimoxazole (120 mg/kg daily in divided doses) for 21 days. Up to 40% of patients receiving this regimen will develop some adverse drug reaction, including a typical allergic rash. If the patient is sensitive to co-trimoxazole, intravenous pentamidine (4 mg/kg per day) or dapsone and trimethoprim is given for the same duration. Atovaquone or a combination of clindamycin and primaquine is also used. In severe cases (PaO2 <9.5 kPa), systemic corticosteroids reduce mortality and should be added. Continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) or mechanical ventilation (see pp. 1165–1166) is required if the patient remains severely hypoxic or becomes too tired. Pneumothorax may complicate the clinical course in an already severely hypoxic patient. If not already on ART, this should be initiated early in the course of infection.

Secondary prophylaxis is required in patients whose CD4 count remains <200 cells/mm3, to prevent relapse, the usual regimen being co-trimoxazole 960 mg three times a week. Patients sensitive to sulphonamide are given dapsone, pyrimethamine or nebulized pentamidine. The last protects only the lungs and does not penetrate the upper lobes particularly efficiently; hence, if relapses occur on this regimen, they may be either atypical or extrapulmonary.

Cryptococcosis

Cryptococcosis

The most common presentation of cryptococcal infection (see p. 296) in the context of HIV is meningitis, although pulmonary and disseminated infections can also occur. The organism, C. neoformans, is widely distributed, often in bird droppings, and is usually acquired by inhalation. The onset may be insidious with non-specific fever, nausea and headache. As the infection progresses, the conscious level is impaired and changes in affect may be noted. Fits or focal neurological presentations are uncommon. Neck stiffness and photophobia may be absent, as these signs depend on the inflammatory response of the host, which, in this setting, is abnormal.

Diagnosis is made on examination of the CSF (perform a CT scan before lumbar puncture to exclude space-occupying pathology). Indian ink staining shows the organisms directly and CSF cryptococcal antigen is positive at variable titre. It is unusual for the cryptococcal antigen to become negative after treatment, although the levels should fall substantially. Cryptococci can also be cultured from CSF and/or blood.

Factors associated with a poor prognosis include a high organism count in the CSF, a low white cell count in the CSF, and an impaired consciousness level at presentation.

Initial treatment is usually with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (4.0 mg/kg per day) with or without flucytosine as induction, although intravenous fluconazole (400 mg daily) is useful if renal function is impaired or if amphotericin side-effects are troublesome.

Patients diagnosed with cryptococcal disease should receive ART, starting at approximately 2 weeks after commencement of cryptococcal treatment, to minimize the risk of IRIS.

Candidiasis

Candidiasis

Mucosal infection, particularly oral, with Candida (see p. 295) is common in immunosuppressed HIV-positive patients. C. albicans is the usual organism, although C. krusei and C. glabrata occur. Pseudomembranous candidiasis, consisting of creamy plaques in the mouth and pharynx, is easily recognized but erythematous Candida appears as reddened areas on the hard palate or as atypical areas on the tongue. Angular cheilitis can occur in association with either form. Vulvovaginal Candida may be difficult to treat.

Oesophageal Candida infection produces odynophagia (see p. 366). Fluconazole or itraconazole is the agent of choice for treatment. Disseminated Candida is uncommon in the context of HIV infection, but if present, fluconazole is the preferred drug; amphotericin, voriconazole or caspofungin is also used. C. krusei may colonize patients who have been treated with fluconazole, as it is fluconazole-resistant. Amphotericin is useful in the treatment of this infection, and an attempt to type Candida from clinically azole-resistant patients should be made. The most successful strategy for managing HIV-positive patients with candidiasis is effective ART.

Aspergillosis

Aspergillosis

Infection with Aspergillus fumigatus (see pp. 295–296) is rare in HIV, unless there are coexisting factors, such as lung pathology, neutropenia, transplantation or glucocorticoid use. Spores are air-borne and ubiquitous. Following inhalation, lung infection proceeds to haematogenous spread to other organs. Sinus infection occurs.

Voriconazole is the preferred treatment, with liposomal amphotericin B (3 mg/kg i.v. daily) as an alternative. Caspofungin is also effective.

Histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis and Penicillium marneffei infection

Histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis and Penicillium marneffei infection

These fungal infections are geographically restricted but should be considered in HIV-positive patients who have travelled to areas of high risk. The most common manifestation is with pneumonia, which may be confused with Pneumocystis jiroveci in its presentation (see above), although systemic infection is reported, particularly with Penicillium, which can also produce papular skin lesions. Treatment is with amphotericin B.

Protozoal infections

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasma gondii (see p. 305) most commonly causes encephalitis and cerebral abscess in the context of HIV, usually as a result of reactivation of previously acquired infection. The incidence depends on the rate of seropositivity to toxoplasmosis in the particular population. High antibody levels are found in France (90% of the adult population). About 25% of the adult UK population is seropositive to Toxoplasma.

Clinical features include a focal neurological lesion and convulsions, fever, headache and possible confusion. Examination reveals focal neurological signs in more than 50% of cases. Eye involvement with chorioretinitis may also be present. In most, but not all, cases of Toxoplasma, serology is positive. Typically, contrast-enhanced CT scan of the brain shows multiple ring-enhancing lesions. A single lesion on CT may be found to be one of several on MRI. A solitary lesion on MRI, however, makes a diagnosis of toxoplasmosis unlikely.

Diagnosis is by characteristic radiological findings on CT and MRI. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) may also be helpful differentiating toxoplasmosis from primary CNS lymphoma. In most cases, an empirical trial of anti-toxoplasmosis therapy is instituted; if this leads to radiological improvement within 3 weeks, this is considered diagnostic. The differential diagnosis includes cerebral lymphoma, tuberculoma or focal cryptococcal infection.

Treatment is with pyrimethamine for at least 6 weeks (loading dose 200 mg, then 50 mg daily), combined with sulfadiazine and folinic acid. Clindamycin and pyrimethamine may be used in patients allergic to sulphonamide.

ART should be initiated as soon as the patient is clinically stable, approximately 2 weeks after acute treatment has begun to minimize the risk of IRIS.

Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidium parvum (see p. 307) can cause a self-limiting acute diarrhoea in an immunocompetent individual. In HIV infection, it can cause severe and progressive watery diarrhea, which may be associated with anorexia, abdominal pain, and nausea and vomiting. In the era of ART, the infection is rare. Cysts attach to the epithelium of the small bowel wall, causing secretion of fluid into the gut lumen and failure of fluid absorption. It is also associated with sclerosing cholangitis (see pp. 476–477). The cysts are seen on stool specimen microscopy using Kinyoun acid-fast stain and are readily identified in small bowel biopsy specimens. ART is associated with complete resolution of infection following restoration of immune function; otherwise, treatment is largely supportive. Nitazoxanide may have some effect.

Microsporidiosis

Microsporidiosis

Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Septata intestinalis are causes of diarrhoea. Spores can be detected in stools using a trichrome or fluorescent stain that attaches to the chitin of the spore surface. ART and immune restoration constitute the treatment of choice and can have a dramatic effect.

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis (see pp. 303–305) occurs in immunosuppressed HIV-positive individuals who have been in endemic areas, which include South America, tropical Africa and much of the Mediterranean. Symptoms are frequently non-specific, with fever, malaise, diarrhoea and weight loss. Splenomegaly, anaemia and thrombocytopenia are significant findings. Amastigotes may be seen on bone marrow biopsy or from splenic aspirates. Serological tests exist for Leishmania but they are not reliable in this setting.

Treatment is with liposomal amphotericin, the drug of choice, and ART once the patient is stable. Relapse is common without ART, in which case long-term secondary prophylaxis may be given.

Viral infections

Hepatitis B and C virus co-infection with HIV

Hepatitis B and C virus co-infection with HIV

Because of the comparable routes of transmission of hepatitis viruses (see pp. 454–455 and 459) and HIV, co-infection is common, particularly in MSM, drug users and those infected by blood products. A higher prevalence of hepatitis viruses is found in those with HIV infection than in the general population. Globally, estimates suggest that 5–15% of people with HIV have chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and about one-third have hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. In the UK, 6.9% of adults with HIV are also estimated to be HBsAg-positive. A global epidemic of acute hepatitis C has been observed over the past decade amongst HIV-positive MSM.

As treatment advances have improved HIV prognosis, hepatitis virus co-infection has become an increasingly significant cause of morbidity and mortality, making the management of HIV and hepatitis co-infection a necessary aspect of clinical care.

All those with newly diagnosed HIV should be screened for hepatitis A, B and C; for those without evidence of immunity, hepatitis A and B vaccines should be provided.

Patients with HIV and hepatitis co-infection are more likely to have rapid liver disease progression than people with mono-infection. In all patients with chronic HCV/HIV and HBV/HIV infections, liver disease should be staged (see p. 452) For those who are likely to have cirrhosis, appropriate monitoring for complications of portal hypertension and HCV screening should be performed. Patients with HIV and liver disease should be jointly managed by clinicians from HIV and hepatitis backgrounds. For people with end-stage liver disease, care should be based in specialist centres, ideally with link to a transplant unit.