The Stomach and Duodenum

Anatomy

Anatomy

The stomach occupies a small area immediately distal to the oesophagus (the cardia), the upper region (the fundus, under the left diaphragm), the mid-region or body and the antrum, which extends to the pylorus (see Fig. 13.8 ). It serves as a reservoir where food can be retained and broken up before being actively expelled into the proximal small intestine.

The smooth muscle of the wall of the stomach has three layers: outer longitudinal, inner circular and innermost oblique layers. There are two sphincters: the gastro-oesophageal sphincter and the pyloric sphincter. The latter is largely made up of a thickening of the circular muscle layer and controls the exit of gastric contents into the duodenum.

The duodenum has outer longitudinal and inner smooth muscle layers. It is C-shaped and the pancreas sits in the concavity. It terminates at the duodenojejunal flexure, where it joins the jejunum.

• The mucosal lining of the stomach can stretch in size with feeding. The greater curvature of the undistended stomach has thick folds or rugae. The mucosa of the upper two-thirds of the stomach contains parietal cells, which secrete hydrochloric acid, and chief cells, which secrete pepsinogen (which initiates proteolysis). There is often a colour change at the junction between the body and the antrum of the stomach, which can be seen macroscopically and confirmed by measuring surface pH.

• The antral mucosa secretes bicarbonate and contains mucus-secreting cells and G cells, which secrete gastrin, stimulating acid production. There are two major forms of gastrin, G17 and G34, depending on the number of amino-acid residues. G17 is the major form found in the antrum. Somatostatin, a suppressant of acid secretion, is also produced by specialized antral cells (D cells).

• Mucus-secreting cells are present throughout the stomach and secrete mucus and bicarbonate. The mucus is made of glycoproteins called mucins.

• The ‘mucosal barrier’, made up of the plasma membranes of mucosal cells and the mucus layer, protects the gastric epithelium from damage by acid and, for example, alcohol, aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and bile salts. Prostaglandins stimulate secretion of mucus, and their synthesis is inhibited by aspirin and NSAIDs, which inhibit cyclo-oxygenase (see Fig. 24.30 ).

• The duodenal mucosa has villi like the rest of the small bowel, and also contains Brunner's glands, which secrete alkaline mucus. This, along with the pancreatic and biliary secretions, helps to neutralize the acid secretion from the stomach when it reaches the duodenum.

Physiology

Physiology

Acid secretion is central to the functionality of the stomach; factors controlling acid secretion are shown in Figure 13.19. Acid is not essential for digestion but does prevent some food-borne infections. It is under neural and hormonal control, and both stimulate acid secretion through the direct action of histamine on the parietal cell. Acetylcholine and gastrin also release histamine via the enterochromaffin cells. Somatostatin inhibits both histamine and gastrin release, and therefore acid secretion.

Other major gastric functions are:

Gastric emptying depends on many factors. There are osmoreceptors in the duodenal mucosa, which control gastric emptying by local reflexes and the release of gut hormones. In particular, intraduodenal fat delays gastric emptying by negative feedback through duodenal receptors.

Gastritis and gastropathy

‘Gastritis’ indicates inflammation associated with mucosal injury (although the term is often used loosely by endoscopists to describe ‘redness’), and ‘gastropathy’ indicates epithelial cell damage and regeneration without inflammation.

Gastritis

Gastritis

Several classifications of gastritis (e.g. Sydney classification) have been proposed but are controversial due to lack of correlation between endoscopic and histological findings. H. pylori infection is the most common cause of gastritis, with autoimmune gastritis being seen in 5% of cases; the remaining causes include viruses (e.g. cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex), duodenogastric reflux and specific causes, e.g. Crohn's, more common in children than adults. Chronic inflammation, particularly if induced by H. pylori, can lead to gastric intestinal metaplasia, a precursor to gastric cancer. The role of surveillance in these patients is unclear.

Autoimmune gastritis

This affects the fundus and body of the stomach (pangastritis), leading to atrophic gastritis and loss of parietal cells, with achlorhydria and intrinsic factor deficiency causing the clinical syndrome of ‘pernicious anaemia’ (see pp. 528–529). Metaplasia, usually of the intestinal type, is almost always in the context of atrophic gastritis. Serum autoantibodies to gastric parietal cells are common and non-specific; antibodies to intrinsic factor are rarer and more significant (see p. 528).

Gastropathy

Gastropathy

Gastropathy is usually caused by irritants (drugs, NSAIDs and alcohol), bile reflux and chronic congestion. Acute erosive/haemorrhagic gastropathy can also be seen after severe stress (stress ulcers); secondary to burns (Curling ulcers), trauma, shock or renal failure; and in portal hypertension (called portal gastropathy). The underlying mechanism for these ulcers is unknown but may be related to an alteration in mucosal blood flow.

Helicobacter pylori infection

Helicobacter pylori is a slow-growing, spiral, Gram-negative, flagellate, urease-producing bacterium (Fig. 13.20), which plays a major role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. It colonizes the mucous layer in the gastric antrum, but is also found in the duodenum in areas of gastric metaplasia. H. pylori is found in greatest numbers under the mucous layer in gastric pits, where it adheres specifically to gastric epithelial cells. It is protected from gastric acid by the juxtamucosal mucous layer which traps bicarbonate secreted by antral cells, and ammonia produced by bacterial urease.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

The prevalence of H. pylori is high in developing countries (80–90% of the population) and much lower (20–50%) in developed countries. Infection rates are highest in lower-income groups. Infection is usually acquired in childhood; although the exact route is uncertain, it may be faecal–oral or oral–oral. The incidence increases with age, probably due to acquisition in childhood when hygiene was poorer (cohort effect) rather than infection in adult life, which is most likely far less than 1% per year in developed countries.

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

The pathogenetic mechanisms are not fully understood, with the majority of the colonized population remaining asymptomatic throughout their life. H. pylori is highly adapted to the stomach environment, exclusively colonizing gastric epithelium and inhabiting the mucous layer, or just beneath. It adheres by a number of adhesion molecules including BabA, which binds to the Lewis antigen expressed on the surface of gastric mucosal cells and causes gastritis in all infected subjects. Damage to the gastric epithelial cell is caused by the release of enzymes and the induction of apoptosis through binding to class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. The production of urease enables the conversion of urea to ammonium and chloride, which are directly cytotoxic. Ulcers are most common when the infecting strain expresses CagA (cytotoxic-associated protein) and VacA (vacuolating toxin) genes secondary to a more pronounced inflammatory and immune response. Expression of CagA and VacA is associated with greater induction of interleukin 8 (IL-8), a potent mediator of gastric inflammation. Genetic variations in the host are also thought to be involved; for example, polymorphisms leading to increased levels of IL-1β are associated with atrophic gastritis and cancer.

Results of H. pylori infection

• Inflammation (antral gastritis and gastric intestinal metaplasia).

• Peptic ulcers (duodenal and gastric).

• Gastric cancer (see pp. 381–382).

Antral gastritis

Antral gastritis is the usual effect of H. pylori infection. It is normally asymptomatic, although patients without ulcers do sometimes experience relief of dyspeptic symptoms after Helicobacter eradication. Chronic antral gastritis causes hypergastrinaemia due to gastrin release from antral G cells. The subsequent increase in acid output is usually asymptomatic but can lead to duodenal ulceration.

Duodenal ulcer

The prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with duodenal ulcers (DUs; see Fig. 13.22A) is falling and in the developed world is now between 50% and 75%, whereas duodenal ulceration was once rare in the absence of H. pylori infection. This has been attributed to a decrease in prevalence of the bacterium and an increase in NSAID use. Eradication of the infection improves ulcer healing and decreases the incidence of recurrence.

The precise mechanism of duodenal ulceration is unclear, as only 15% of patients infected with H. pylori (50–60% of the adult population worldwide) develop duodenal ulcers. Factors that have been implicated include increased gastrin secretion, smoking, bacterial virulence and genetic susceptibility.

Gastric ulcer

Gastric ulcers (GUs; see Fig. 13.22B) are associated with a gastritis affecting the body as well as the antrum of the stomach (pangastritis), causing parietal cell loss and reduced acid production. The ulcers are thought to occur because of a reduction of gastric mucosal resistance due to cytokine production caused by the infection, or perhaps because of alterations in gastric mucus.

Peptic ulcer disease

Peptic ulcer disease

A peptic ulcer consists of a break in the superficial epithelial cells penetrating down to the muscularis mucosa of either the stomach or the duodenum; there is a fibrous base and an increase in inflammatory cells. Erosions, by contrast, are superficial breaks in the mucosa alone. DUs are most commonly found in the duodenal cap; the surrounding mucosa appears inflamed, haemorrhagic or friable (duodenitis). GUs are most commonly seen on the lesser curve near the incisura, but can be found in any part of the stomach.

Epidemiology of peptic ulcer disease

Epidemiology of peptic ulcer disease

DUs affect approximately 10% of the adult population and are 2–3 times more common than GUs.

Ulcer rates are declining rapidly for younger men and increasing for older individuals, particularly women. Both DUs and GUs are common in the elderly. There is considerable geographical variation, with peptic ulcer disease being more prevalent in developing countries related to the high H. pylori infection. In the developed world, the percentage of NSAID-induced peptic ulcers is increasing as the prevalence of H. pylori declines.

Clinical features of peptic ulcer disease

Clinical features of peptic ulcer disease

The characteristic feature of peptic ulcer is recurrent, burning epigastric pain. It has been shown that if a patient points with a single finger to the epigastrium as the site of the pain, this is strongly suggestive of peptic ulcer disease. The relationship of the pain to food is variable and, on the whole, not helpful in diagnosis. The pain of a DU classically occurs at night (as well as during the day) and is worse when the patient is hungry, but this is not reliable. The pain of both GUs and DUs may be relieved by antacids.

Nausea may accompany the pain; vomiting is infrequent but can relieve the pain. Anorexia and weight loss may occur, particularly with GUs. Persistent and severe pain suggests complications, such as penetration into other organs. Back pain suggests a penetrating posterior ulcer. Severe ulceration can occasionally be symptomless, as many who present with acute ulcer bleeding or perforation have no preceding ulcer symptoms.

Untreated, the symptoms of a DU relapse and remit spontaneously. The natural history is for the disease to remit over many years due to the onset of atrophic gastritis and a decrease in acid secretion.

Epigastric tenderness is common in both ulcer and non-ulcer dyspepsia.

Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection

Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection

Diagnosis of H. pylori is necessary if the clinician plans to treat a positive result. This is usually in the context of active peptic ulcer disease, previous peptic ulcer disease or mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, or to ‘test and treat’ patients with dyspepsia under the age of 55 with no alarm symptoms (i.e. weight loss, anaemia, dysphagia, vomiting or family history of gastrointestinal cancer). Examination is usually unhelpful.

Non-invasive methods

• Serological tests detect immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies and are reasonably sensitive (90%) and specific (83%). They have been used in diagnosis and in epidemiological studies. IgG titres may take up to 1 year to fall by 50% after eradication therapy and therefore are not useful for confirming eradication or the presence of a current infection. Antibodies can also be found in the saliva but tests are not as sensitive or specific as serology.

• 13C-Urea breath test (Fig. 13.21) is a quick and reliable test for H. pylori and can be used as a screening test. The measurement of 13CO2 in the breath after ingestion of 13C-urea requires a mass spectrometer. The test is sensitive (90%) and specific (96%), but the sensitivity can be improved by ensuring the patient has not taken antibiotics in the 4 weeks before the test and PPIs in the previous 2 weeks.

• Stool antigen test is beginning to supersede breath testing as the method used to determine H. pylori status. A specific immunoassay, using monoclonal antibodies for the qualitative detection of H. pylori antigen, is now widely available. The overall sensitivity is 97.6% and specificity is 96%. The test is useful in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection and for monitoring efficacy of eradication therapy. Patients should be off PPIs for 2 weeks but can continue with H2-blockers. Newer stool antigen tests are being developed that can be performed in the clinic setting, although at present the sensitivity and specificity are not as good as for those performed in the laboratory.

Invasive methods (endoscopy)

• Biopsy urease test. Gastric biopsies, usually antral unless additional material is needed to exclude proximal migration, are added to a substrate containing urea and phenol red. If H. pylori is present, the urease enzyme that the bacteria produce splits the urea to release ammonia, which raises the pH of the solution and causes a rapid colour change (yellow to red). This enables patients' H. pylori status to be determined before they leave the endoscopy suite. The test may be falsely negative if patients are taking PPIs or antibiotics at the time.

• Histology. H. pylori can be detected histologically on routine (Giemsa) stained sections of gastric mucosa obtained at endoscopy. The sensitivity is reduced if a patient is on PPIs, but less so than with the urease test. Sensitivity can be improved with immunohistochemical staining using an anti-H. pylori antibody.

• Culture. Biopsies obtained can be cultured on a special medium, and in vitro sensitivities to antibiotics can be tested. This technique is typically used for patients with refractory H. pylori infection to identify the appropriate antibiotic regimen; routine culture is rare.

Investigation of suspected peptic ulcer disease

Investigation of suspected peptic ulcer disease

• Patients under 55 years of age, with typical symptoms of peptic ulcer disease who test positive for H. pylori, can start eradication therapy without further investigation.

• Older patients require endoscopic diagnosis (Fig. 13.22) and exclusion of cancer. All gastric ulcers must be biopsied to exclude an underlying malignancy and should be followed up endoscopically until healing has taken place.

• All patients with ‘alarm symptoms’ should undergo endoscopy.

Management

Management

Eradication therapy

Current recommendations are that all patients with duodenal and gastric ulcers should have H. pylori eradication therapy if the bacteria are present. Many patients have incidental H. pylori infection with no GU or DU. On balance, whether all such patients should have eradication therapy is controversial (see ‘Functional dyspepsia’, pp. 429–430).

The increase in the prevalence of GORD and adenocarcinoma of the lower oesophagus in the last few years is currently unexplained, but has been postulated to be linked to eradication of H. pylori; this seems unlikely but is not disproven.

Depending on local antibacterial resistance patterns, standard eradication therapies in the developed world are successful in approximately 90% of patients. Re-infection is very uncommon (1%) in developed countries. In developing countries, re-infection is more common, compliance with treatment may be poor and metronidazole resistance is high (>50%, as it is frequently used for parasitic infections), so failure of eradication is common.

There are many regimens for eradication, but all must take into account that:

• Good compliance is essential.

• There is a high incidence of resistance to metronidazole and clarithromycin, particularly in some populations. Clarithromycin resistance has doubled in Europe in the last decade.

Metronidazole, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, tetracycline and bismuth are the most widely used agents. Resistance to amoxicillin (1–2%) and tetracycline (<1%) is low, except in countries where they are available without prescription, where resistance may exceed 50%. Quinolones (such as ciprofloxacin), furazolidone and rifabutin are also used when standard regimens have failed (‘rescue therapy’). None of these drugs is effective alone; eradication regimens therefore usually comprise two antibiotics, given with powerful acid suppression in the form of a PPI. Bismuth-containing quadruple therapy is advocated as first-line treatment because of increasing clarithromycin resistance; the standard clarithromycin-based triple therapy has been replaced as the treatment of choice in areas where resistance is high.

Example regimens

• Omeprazole 20 mg + clarithromycin 500 mg and amoxicillin 1 g – all twice daily

• Omeprazole 20 mg + metronidazole 400 mg and clarithromycin 500 mg – all twice daily.

These should be given for 7 or 14 days. Two-week treatments increase the eradication rates but increased side-effects may reduce compliance.

In eradication failures and in areas of clarithromycin resistance, bismuth chelate (120 mg 4 times daily), metronidazole (400 mg 3 times daily), tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) and a PPI (20–40 mg twice daily) for 14 days is used. Sequential courses of therapy are also used in such cases (5 days of PPI and amoxicillin, followed by a 5-day period of PPI with clarithromycin and tinidazole). With the increase in clarithromycin resistance, many are using this quadruple therapy for initial treatment.

Prolonged therapy with a PPI after a course of PPI-based 7-day triple therapy is not necessary for ulcer healing in most H. pylori-infected patients. The effectiveness of treatment for uncomplicated duodenal ulcer should be assessed symptomatically. If symptoms persist, breath or stool testing should be performed to check eradication (off PPI therapy).

Patients with a risk of bleeding or those with complications, such as haemorrhage or perforation, should always have a 13C-urea breath test or stool test for H. pylori 6 weeks after the end of treatment to be sure that eradication has been successful. Long-term PPIs may be necessary if a rebleed would be likely to be fatal.

General measures

Stopping smoking should be strongly encouraged, as smoking slows mucosal healing.

Patients with gastric ulcers should be routinely re-endoscoped at 6 weeks to confirm mucosal healing and exclude an underlying gastric cancer. Repeat biopsies may be necessary.

Complications of peptic ulcer disease

Complications of peptic ulcer disease

Haemorrhage

See page 386.

Perforation

The frequency of perforation (see also pp. 432–435) of peptic ulceration is decreasing, partly because of medical therapy. DUs perforate more commonly than GUs, usually into the peritoneal cavity; perforation into the lesser sac also occurs. Detailed management of perforation is described on pages 432-435. Laparoscopic surgery is usually performed to close the perforation and drain the abdomen. Conservative management using nasogastric suction, intravenous fluids and antibiotics is occasionally used in elderly and very sick patients.

Gastric outlet obstruction

The obstruction may be pre-pyloric, pyloric or duodenal. The obstruction occurs either because there is an active ulcer with surrounding oedema or because the healing of an ulcer has been followed by scarring. However, obstruction due to peptic ulcer disease and gastric malignancy are now uncommon; Crohn's disease or external compression from a pancreatic carcinoma is a more common cause. Adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is a very rare cause.

After gastric outlet obstruction, the stomach becomes full of gastric juice and ingested fluid and food, giving rise to the main symptom of vomiting, usually without pain, as the characteristic ulcer pain has abated owing to healing.

Vomiting is infrequent, projectile and large in volume; the vomitus contains particles of previous meals. On examination of the abdomen, there may be a succussion splash. The diagnosis is made by endoscopy but can be suspected from the nature of the vomiting; by contrast, psychogenic vomiting is frequent, small-volume and usually noisy.

Severe or persistent vomiting causes loss of acid from the stomach and a hypokalaemic metabolic alkalosis (see pp. 180–181). Vomiting will often settle with intravenous fluid and electrolyte replacement, gastric drainage via a nasogastric tube, and potent acid suppression therapy. Endoscopic dilatation of the pyloric region is useful, as is luminal stenting, and overall, 70% of patients can be managed without surgery.

Surgical treatment and its long-term consequences

Once the mainstay of treatment, surgery is now used in peptic ulcer disease only for complications including:

No other procedure, such as gastrectomy or vagotomy, is required.

In the past, two types of operation were performed: a partial gastrectomy or a vagotomy. In the latter, either a truncal vagotomy with a pyloroplasty or gastro-jejunostomy was performed, or highly selective vagotomy or proximal gastric vagotomy, which did not require a bypass procedure.

Long-term complications of surgery, which are still seen occasionally, include:

• Recurrent ulcer. If this occurs, check for H. pylori; rule out Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (see p. 512). Malignancy needs to be excluded in all cases.

• Dumping. This term describes a number of upper abdominal symptoms (e.g. nausea and distension associated with sweating, faintness and palpitations) that occur in patients following gastrectomy or gastroenterostomy. It is due to ‘dumping’ of food into the jejunum, causing rapid fluid shifts from plasma to dilute the high osmotic load with reduction of blood volume. The symptoms are usually mild and patients adapt to them. It is rare for it to be a long-term problem, and if so, the symptoms usually have a functional element. Hypoglycaemia can also occur.

• Diarrhoea. This was chiefly seen after vagotomy. Recurrent severe episodes occurred in about 1% of patients. Antidiarrhoeals are the usual treatment.

• Nutritional complications. In the long term, almost any gastric surgery, but particularly gastrectomy, may be followed by:

– iron deficiency, due to poor absorption

– folate deficiency, usually due to poor intake

– vitamin B12 deficiency, due to intrinsic factor deficiency

Other H. pylori-associated diseases

Other H. pylori-associated diseases

• Gastric adenocarcinoma. The incidence of distal (but not proximal) gastric cancer parallels that of H. pylori infection in countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer. Serological studies show that people infected with H. pylori have a higher incidence of distal gastric carcinoma (see p. 382).

• Gastric B-cell lymphoma. Over 70% of patients with gastric B-cell lymphomas (MALT) have H. pylori. H. pylori gastritis has been shown to contain the clonal B cell that eventually gives rise to the MALT lymphoma (see pp. 384 and 382).

NSAIDs, Helicobacter and ulcers

NSAIDs, Helicobacter and ulcers

Aspirin and other NSAIDs deplete mucosal prostaglandins by inhibiting the cyclo-oxygenase (COX) pathway, which leads to mucosal damage. Cyclo-oxygenase occurs in two main forms: COX-1, the constitutive enzyme; and COX-2, inducible by cytokine stimulation in areas of inflammation. COX-2-specific inhibitors have less effect on the COX-1 enzyme in the gastric mucosa; they still produce gastric mucosal damage but less than with other conventional NSAIDs. Their use is limited by concern regarding cardiovascular side-effects.

Some 50% of patients taking regular NSAIDs will develop gastric mucosal damage and approximately 30% will have ulcers on endoscopy. Only a small proportion of patients have symptoms (about 5%) and only 1–2% have a major problem: that is, gastrointestinal bleed or perforation. Because of the large number of patients on NSAIDs, including low-dose aspirin for vascular prophylaxis, this is a significant problem, particularly in the elderly.

H. pylori and NSAIDs are independent and synergistic risk factors for the development of ulcers. In a meta-analysis, the odds ratio (OR) for the incidence of peptic ulcer was 61.1 in patients infected with H. pylori and also taking NSAIDs, compared with uninfected controls not taking NSAIDs.

Management

Management

• Stop the ingestion of NSAIDs.

• Start H. pylori eradication therapy if the patient is H. pylori-positive.

In many people with severe arthritis, stopping NSAIDs may not be possible. Therefore use:

• An NSAID with low GI side-effects at the lowest dose possible (see pp. 665–666). If there is no cardiovascular risk, a COX-2 NSAID can be used (see p. 666).

• Prophylactic cytoprotective therapy, e.g. PPI or misoprostol (a synthetic analogue of prostaglandin E1 800 µg/day) for all high-risk patients, i.e. over 65 years, those with a peptic ulcer history, particularly with complications, and those on corticosteroid or anticoagulant therapy. PPIs reduce the risk of endoscopic duodenal and gastric ulcers and are better tolerated than misoprostol, which causes diarrhoea.

Gastric tumours

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma

Gastric cancer is currently the fourth most common cancer found worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality. The incidence increases with age (peak incidence 50–70 years), and it is rare under the age of 30 years. The highest incidence of the disease is found in Eastern Asia, Eastern Europe and South America. The incidence in men is twice that in women and varies throughout the world, being high in Japan (M: 53/100 000, F: 21.3/100 000) and Chile, and relatively low in the USA (M: 7/100 000, F: 2.9/100 000). In the UK, carcinoma of the stomach (see Fig. 13.1) is the eighth most common cancer (M: 16/100 000, F 9/100 000). The overall worldwide incidence of gastric carcinoma is falling, even in Japan, probably due to reductions in the incidence of Helicobacter and, before this, improvements in food storage. However, the incidence of proximal gastric cancers is increasing in the West and they have very similar demographic and pathological features to Barrett's-associated oesophageal adenocarcinoma.

Epidemiology and pathogenesis

Epidemiology and pathogenesis

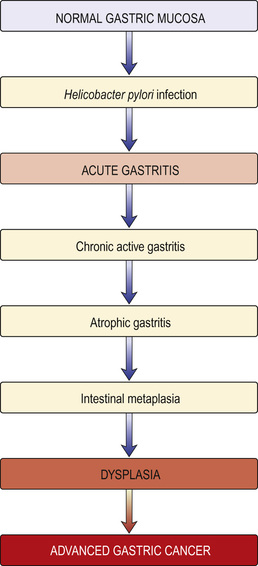

• H. pylori infection and distal gastric cancer are strongly linked. H. pylori is recognized by the International Agency for Research in Cancer (IARC) as a group 1 (definite) gastric carcinogen. H. pylori infection causes chronic gastritis, which eventually leads to atrophic gastritis and pre-malignant intestinal metaplasia (Fig. 13.23). Much of the earlier epidemiological data (i.e. the increase of cancer in lower socioeconomic groups) can be explained by the intrafamilial spread of H. pylori. Epstein–Barr virus is detected in 2–16% of gastric cancers worldwide, but its role in aetiology is not well understood.

• Dietary factors may also be involved (as both initiators and promoters) and have separate roles in carcinogenesis. Diets high in salt probably increase the risk. Dietary nitrates can be converted into nitrosamines by bacteria at neutral pH; nitrosamines are known to be carcinogenic in animals but the evidence in human carcinogenesis is limited. Nitrosamines are also present in the stomach of patients with achlorhydria, who have an increased cancer risk.

• Tobacco smoking is associated with an increased incidence of stomach cancer.

• Genetic abnormality is also a factor. The most common abnormality is a loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of tumour suppressor genes such as p53 (in 50% of cancers, as well as in pre-cancerous states) and the gene encoding adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) (in over one-third of gastric cancers). These abnormalities are similar to those found in colorectal cancers. Some rare families with diffuse gastric cancer have been shown to have mutations in the E-cadherin gene (CDH-1). There is a higher incidence of gastric cancer in blood group A patients.

• First-degree relatives of patients with gastric cancer have 2–3-fold increased relative risk of developing the disease, but this may be environmental rather than inherited.

• Pernicious anaemia carries a small increased risk of gastric carcinoma due to the accompanying atrophic gastritis.

• Partial gastrectomy (postoperative stomach) carries an increased risk of gastric cancer, whether performed for a GU or DU; this is probably due to untreated H. pylori infection.

Screening

Screening

Earlier diagnosis has been advocated in an attempt to improve the poor prognosis of gastric cancer. (Screening is discussed on pp. 591–592.) Although the incidence of gastric cancer is falling in Japan, where aggressive screening by barium studies is followed by endoscopy if there is doubt, there is no evidence that screening has had an effect on overall mortality. Similarly, early investigation of dyspepsia has had little effect on mortality, possibly because of the relatively low prevalence of cancer.

Early gastric cancer

Early gastric cancer is defined as a carcinoma that is confined to the mucosa or submucosa, regardless of the presence of lymph node metastases. It is associated with 5-year survival rates of approximately 90%, but many of these patients would have survived 5 years without treatment. In Japan, mass screening with mobile units has increased the proportion of early gastric cancers (EGC) diagnosed. In a large series of patients from the UK with gastric cancer, only 0.7% were identified as having EGC. They are usually detected by chance, as although EGC exists in Western populations, endoscopists do not readily recognize it at present.

Pathology

Pathology

There are two major types of gastric cancer:

• Intestinal (type 1) with well-formed glandular structures (differentiated). The tumours are polypoid or ulcerating lesions with heaped-up, rolled edges. Intestinal metaplasia is seen in the surrounding mucosa, often with H. pylori. This type is more likely to involve the distal stomach and occur in patients with atrophic gastritis. It has a strong environmental association.

• Diffuse (type 2) with poorly cohesive cells (undifferentiated) that tend to infiltrate the gastric wall. It may involve any part of the stomach, especially the cardia, and has a worse prognosis than the intestinal type. Loss of expression of the cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin is the key event in the carcinogenesis of diffuse gastric cancers. Unlike type 1 gastric cancers, type 2 cancers have similar frequencies in all geographic areas and occur in a younger population.

Some 50% of gastric cancers in Western countries occur in the proximal stomach.

Clinical features

Clinical features

Symptoms

Around 50% of patients with EGC discovered at screening have no symptoms. Most patients with carcinoma of the stomach have advanced disease at the time of presentation. The most common symptom of advanced disease is epigastric pain, indistinguishable from the pain of peptic ulcer disease; it may be relieved by food and antacids. The pain can vary in intensity but may be constant and severe, and there may also be nausea, anorexia and weight loss. Vomiting is frequent and can be severe if the tumour encroaches on the pylorus. Dysphagia can occur with tumours involving the fundus. Gross haematemesis is unusual but anaemia from occult blood loss is frequent. No pattern of symptoms is suggestive of EGC.

Widely spreading submucosal gastric cancer causes diffuse thickening and rigidity of the stomach wall and is called ‘linitis plastica’.

Patients can present at a late stage with malignant ascites or jaundice due to liver involvement. Metastases also occur in bone, brain and lung, producing appropriate symptoms.

Signs

Weight loss is often the dominant feature. Nearly 50% of patients have a palpable epigastric mass with abdominal tenderness. A palpable lymph node is sometimes found in the supraclavicular fossa (Virchow's node, usually on the left side), and metastases are present in up to one-third of patients at presentation. This cancer is the most frequently associated with dermatomyositis (see p. 698) and acanthosis nigricans.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

• Gastroscopy (Fig. 13.24) allows biopsies to be taken for histological assessment. Positive biopsies can be obtained in almost all cases of obvious carcinoma, but a negative biopsy does not necessarily rule out the diagnosis. For this reason, 8–10 biopsies should be taken from suspicious lesions. Diffuse type gastric cancer infiltrates the submucosa and muscularis propria and can be undetected on endoscopy; multiple deep biopsies help.

Staging

• CT scan of the chest and abdomen with a gastric water load can demonstrate gastric wall thickening, lymphadenopathy and lung and liver secondaries, but has limited ability to determine the depth of local tumour invasion.

• Endoscopic ultrasound is useful for local staging to demonstrate the depth of penetration of the cancer through the gastric wall and extension into local lymph nodes. It complements CT and ultrasound but is most relevant to confirm that a cancer is confined to the superficial mucosa, before endoscopic resection.

• Laparoscopy is useful in patients being considered for surgery to exclude serosal disease.

• PET and CT/PET can be helpful in further delineation of the cancer.

The TNM classification is used. The tumour grade (T) indicates depth of tumour invasion, N denotes the presence or absence of lymph nodes, and M indicates presence or absence of metastases. TNM classification is then combined into stage categories 0–4. At presentation, two-thirds of patients are at stage 3 or 4: that is, advanced disease (Box 13.13). The histological grade of the tumour also determines survival.

Management

Management

As with all cancers, treatment is discussed with a multidisciplinary team. Early non-ulcerated mucosal lesions can be removed endoscopically by either endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection.

Surgery remains the most effective form of treatment if the patient is an operative candidate. Careful selection has reduced the numbers undergoing surgery and has improved the overall surgical 5-year survival rates to around 30%. Five-year survival rates in ‘curative’ operations are as high as 50%. Surgery, combined chemoradiotherapy and treatment of advanced disease are described on pages 635–636. The multinational MAGIC trial demonstrated the benefits of perioperative chemotherapy with epirubicin, cisplatin and infusional 5-fluorouracil (ECF) (see p. 636), where 5-year survival in operable gastric and lower oesophageal adenocarcinomas increased from 23% to 36%. An alternative regimen is oral epirubicin, oxaliplatin and capecitabine. Despite the improved results, the overall survival rate for a patient with gastric carcinoma has not dramatically improved, with a maximum 5-year survival rate of 10% overall. Palliative care, with relief of pain and counselling, is usually required.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST)

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST)

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) are a subset of gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumours of varying differentiation. They are usually asymptomatic and found by chance but occasionally they can ulcerate and bleed. There are 200–900 new cases each year in the UK. GISTs mostly affect people between 55 and 65 years of age.

These tumours were previously classified as gastrointestinal leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas, leiomyoblastomas or schwannomas. Truly benign leiomyomas do occur, mainly in the oesophagus, but GISTs are now recognized as a distinct group of mesenchymal tumours and comprise about 80% of gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumours. They are of stromal origin and are thought to share a common ancestry with the interstitial cells of Cajal. They have varying differentiation, with mutations occurring in the cellular proto-oncogene KIT (which leads to activation and cell-surface expression of the tyrosine kinase KIT (CD 117)) in 80%, and also in platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFRA) in up to 10% of patients.

Management

Management

Treatment is surgical as far as possible. These tumours generally grow slowly but may be malignant. Imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (see pp. 601–602), is chosen for unresectable or metastatic disease, and is now used as adjunctive therapy after surgical removal of the primary in the absence of metastatic disease. Some patients are resistant to this; sunitinib can be used as an alternative agent over a short time period.

Primary gastric lymphoma

Primary gastric lymphoma

Mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue (MALT) lymphomas are indolent B-cell marginal zone lymphomas that primarily involve sites other than lymph nodes (gastrointestinal tract, thyroid, breast or skin). They constitute about 10% of all types of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL).

Aetiology

Aetiology

About 90% of cases are due to H. pylori infection. Chromosome abnormalities t(1;14)(p22; q32) and t(11;18)(q21; q21) have also been noted in this form of NHL.

Clinical features

Clinical features

Most patients are diagnosed in their 60s with stage I or stage II disease outside the lymph nodes. Patients have stomach pain, ulcers or other localized symptoms, but rarely have systemic complaints such as fatigue or fever.

Management

Management

Eradication of H. pylori infection may resolve cases of local gastric involvement. After standard eradication regimens, 50% of patients show resolution at 3 months. Other patients may resolve after 12–18 months of observation. Stage III or IV disease is treated with surgery or chemotherapy with or without radiation. The prognosis is good, with an estimated 90% 5-year survival.

Gastric polyps

Gastric polyps

Gastric polyps are found in about 1% of endoscopies, usually by chance. They rarely produce symptoms, but larger lesions can result in anaemia or haematemesis.

Endoscopic biopsy is the usual approach to diagnosis and treatment is possible polypectomy based on histological finding. Occasional large or multiple polyps may require surgery.

• Hyperplastic polyps are by far the most common type. Most are <2 cm. The polyps are rarely pre-malignant, but may be accompanied by pre-malignant atrophic gastritis.

• Adenomatous polyps are usually solitary lesions in the antrum. Approximately 3% progress to gastric cancer, especially if >2 cm in diameter, but they are not a common cause of gastric cancer (compare this with colorectal cancer).

• Cystic gland polyps contain microcysts that are lined by fundic-type parietal and chief cells. They are located in the fundus and body of the stomach. They are found in otherwise normal subjects, but are especially common in familial polyposis syndromes and patients on PPIs. Their malignant potential is negligible, although low-grade dysplasia is seen in the absence of familial adenomatous polyposis coli (FAP), and high-grade dysplasia exclusively in its presence.

• Inflammatory fibroid polyps are benign spindle cell tumours infiltrated by eosinophils. Excision of these polyps is indicated because of their propensity to enlarge and cause obstruction.

Acute and Chronic Gastrointestinal Bleeding

This section should be read in conjunction with the descriptions of the specific conditions mentioned.

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding

The cardinal features are haematemesis (the vomiting of blood) and melaena (the passage of black tarry stools, the black colour being due to blood altered by passage through the gut). Melaena can occur with bleeding from any lesion proximal to the right colon. Rarely, melaena can also result from bleeding from the right colon.

Following a bleed from the upper gastrointestinal tract, unaltered blood can appear per rectum, but the bleeding must be massive and is almost always accompanied by shock. The passage of dark blood and clots without shock is always due to lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Aetiology

Aetiology

Peptic ulceration is the most common cause of serious and life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding (Fig. 13.25). The relative incidence of causes depends on the patient population; overall, incidence has fallen. In the developing world, haemorrhagic viral infections (see Box 11.33 ) can cause significant gastrointestinal bleeding.

Drugs

Aspirin (even 75 mg/day) and other NSAIDs can produce ulcers and erosions. These agents are also responsible for gastrointestinal haemorrhage from both duodenal and gastric ulcers, particularly in the elderly. They are available over the counter in the UK and patients may not be aware that they are taking aspirin or an NSAID. Corticosteroids in the usual therapeutic doses have no influence on gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents do not cause acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage per se, but bleeding from any cause is greater if the patient is anticoagulated.

Clinical approach to the patient

Clinical approach to the patient

All cases with a recent (i.e. within 48 hours) significant gastrointestinal bleed should be seen in hospital. In many, no immediate treatment is required, as there has been only a small amount of blood loss. Approximately 85% of patients stop bleeding spontaneously within 48 hours.

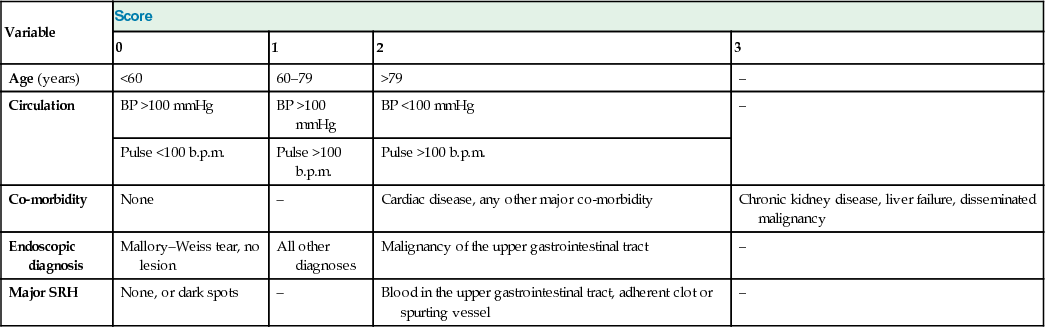

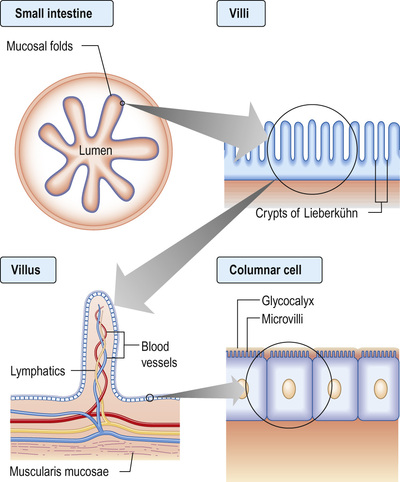

Scoring systems have been developed to assess the risk of rebleeding or death.

Boxes 13.14 and 13.15 show the Rockall score, which is based on clinical and endoscopy findings. The Blatchford score uses the level of plasma urea, haemoglobin and clinical markers, but not endoscopic findings, to determine the need for intervention such as blood transfusion or endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding.

The following factors affect the risk of rebleeding and death:

• evidence of co-morbidity, e.g. cardiac failure, ischaemic heart disease, chronic kidney disease and malignant disease

• presence of the classical clinical features of shock (pallor, cold peripheries, tachycardia and low blood pressure)

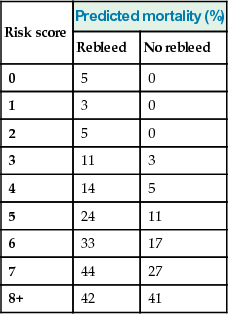

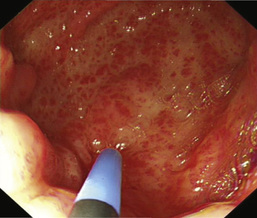

• endoscopic diagnosis, e.g. Mallory–Weiss tear, peptic ulceration, gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE; Fig. 13.26)

• endoscopic stigmata of recent bleeding, e.g. adherent blood clot, spurting vessel

Bleeding associated with liver disease is often severe and recurrent if it is from varices. Liver failure can develop.

Management

Management

Immediate management

This is shown in Box 13.16. In addition, stop NSAIDs, aspirin, clopidogrel and warfarin if patients are taking them. Stopping antiplatelets can be dangerous and may produce thrombosis; discuss this urgently with a cardiologist.

Many hospitals have multidisciplinary specialist teams with agreed protocols and the latter should be followed. Patients should be managed in high-dependency beds. Oxygen should be given and the patient should be kept nil by mouth until an endoscopy has been performed.

Patients with large bleeds and clinical signs of shock require urgent resuscitation. Details of the management of shock are given in Figure 25.24.

Blood volume

The major principle is to restore the blood volume rapidly to normal via one or more large-bore intravenous cannulae; plasma expanders or 0.9% saline are given until the blood becomes available (see pp. 1157–1158). Transfusion of red cell concentrates is used with a proposed transfusion threshold of 70 g/L. This has yet to be universally adopted.

Transfusion must be monitored to avoid overload leading to heart failure, particularly in the elderly. The pulse rate and venous pressure are guides to adequacy of transfusion. A central venous pressure line is inserted for patients with organ failure who require blood transfusion, and in those most at risk of developing heart failure.

Haemoglobin levels are generally a poor indicator of the need to transfuse because anaemia does not develop immediately as haemodilution has not taken place. In most patients, the bleeding stops, albeit temporarily, so that further assessment can be made.

Endoscopy

Endoscopy will usually diagnose, stratify risk, and enable therapy to be performed if needed. Endoscopy should be carried out as soon as possible after the patient has been resuscitated. Patients with Rockall scores of 0 or 1 pre-endoscopy may be candidates for immediate discharge (see below) and outpatient endoscopy the following day, depending on local policy.

Endoscopy can detect the cause of the haemorrhage in 80% or more of cases. In patients with a peptic ulcer, if the stigmata of a recent bleed are seen (i.e. a spurting vessel, active oozing, fresh or organized blood clot or black spots), the patient is more likely to rebleed. Calculation of the post-endoscopy Rockall score (see Box 13.15) gives an indication of the risk of rebleeding and death.

At first endoscopy:

• Varices should be treated, usually with banding.

• Stenting is also used for bleeding varices but is not yet widely available (see p. 471). It is an alternative to a Sengstaken tube.

• Bleeding ulcers and those with stigmata of recent bleeding should be treated using two or three haemostatic methods: injection with adrenaline (epinephrine) and thermal coagulation (with heater probe, bipolar probe, or laser or argon plasma coagulation) or endoscopic clipping; dual and triple therapy is more effective than monotherapy in reducing rebleeding. Haemostatic powders have recently been developed that can be sprayed through a catheter during gastroscopy. These are useful in the more difficult bleeds, such as cancer-related bleeding and challenging ulcers.

• Antral biopsies should be taken to look for H. pylori. A positive biopsy urease test is valid but a negative test is not reliable. If the urease test is negative, gastric histology should always be performed.

Drug therapy

After diagnosis at endoscopy, an intravenous PPI (e.g. omeprazole 80 mg followed by infusion 8 mg/h for 72 h) should be given to all patients with actively bleeding ulcers or ulcers with a visible vessel, as it reduces rebleeding rates and the need for surgery.

Uncontrolled or repeat bleeding

Endoscopy should be repeated to assess the bleeding site and to treat, if possible. Embolization by an interventional radiologist may be necessary if the bleeding persists. If this is not available locally or is unsuccessful, surgery is used to control the haemorrhage primarily.

Discharge policy

The patient's age, diagnosis on endoscopy, co-morbidity, the presence or absence of shock and the availability of support in the community should be taken into consideration. In general, all patients who are haemodynamically stable and have no stigmata of recent haemorrhage on endoscopy (Rockall score pre-endoscopy 0, post-endoscopy <1) can be discharged from hospital within 24 hours. All shocked patients and patients with co-morbidity need longer inpatient observation.

Specific conditions

These are discussed on page 471.

Mallory–Weiss tear

This is a linear mucosal tear occurring at the oesophagogastric junction and produced by a sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure. It often follows a bout of coughing or retching, and is classically seen after alcoholic ‘dry heaves’. There may, however, be no antecedent history of retching. Most bleeds are minor and discharge is usual within 24 hours. The haemorrhage may be large but most patients stop spontaneously. Early endoscopy confirms diagnosis and allows therapy such as clipping if necessary. Surgery with oversewing of the tear is rarely needed.

Chronic peptic ulcer

Eradication of H. pylori is started as soon as possible (see p. 380). A PPI is continued for 4 weeks to ensure ulcer healing. Eradication of H. pylori should always be checked in a patient who has bled, and long-term acid suppression is given if H. pylori eradication cannot be achieved. If bleeding is not controlled, the patient should either undergo angiography and embolization or be referred directly for surgery.

Gastric carcinoma

Most of these patients do not have large bleeds but surgery is occasionally necessary for uncontrolled or repeat bleeding. Usually, surgery can be delayed until the patient has been fully evaluated (see p. 383). Oozing from gastric cancer is very difficult to control endoscopically. Radiotherapy can occasionally be successful but its effects are not immediate.

Bleeding after percutaneous coronary intervention

In the era of ever more aggressive percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), the list of antithrombotic medication grows longer: glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, fondaparinux and platelet inhibitors (e.g. clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor). Taken in addition to the oral anticoagulants that this group of patients are often taking, these give rise to a gastrointestinal bleeding rate of approximately 2% of patients undergoing PCI (who are on antiplatelet therapy, e.g. clopidogrel), and there is a high mortality of 5–10%. It has become increasingly evident in this patient group that gastroscopy should be performed on an urgent basis and not deferred for days or weeks. A bolus of intravenous PPI is administered, followed by an infusion; platelet infusion is given to counter the effect of clopidogrel. Management is difficult, as cessation of antiplatelet therapy has a high risk of acute stent thrombosis and also an associated high mortality. Using a risk assessment score (e.g. Blatchford), a reasonable approach is to stop all antiplatelet therapy in high-risk patients but continue it in low-risk ones. Co-prescribed proton pump inhibition does not decrease the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel, as was first thought. These patients should be under the combined care of a cardiologist and a gastroenterologist.

Prognosis

Prognosis

The mortality from gastrointestinal haemorrhage has not changed from 5–12% over the years, despite many changes in management, mainly because of a demographic shift to more elderly patients with co-morbidity. The lowest mortality rates are achieved in dedicated medical/surgical gastrointestinal units.

Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Massive bleeding from the lower gastrointestinal tract is rare and is usually due to diverticular disease or ischaemic colitis. Common causes of small bleeds are haemorrhoids and anal fissures. The causes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding are shown in Figure 13.27.

Management

Management

Most acute lower gastrointestinal bleeds start and stop spontaneously. The few patients who continue bleeding and are haemodynamically unstable need resuscitation using the same principles as for upper gastrointestinal bleeding (see p. 386). Surgery is rarely required.

A diagnosis is made using the history and examination, including rectal examination and the following investigations as appropriate:

• Proctoscopy (e.g. anorectal disease, particularly haemorrhoids)

• Flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, ischaemic colitis, diverticular disease, angiodysplasia)

• Video capsule endoscopy (Fig. 13.28)

• Angiography to seek vascular abnormality (e.g. angiodysplasia). The yield of angiography is low, so it is a test of last resort.

Isolated episodes of rectal bleeding in the young (<45 years) usually only require rectal examination and flexible sigmoidoscopy because the probability of a significant proximal lesion is very low, unless there is a strong family history of colorectal cancer at a young age. Individual lesions are treated as appropriate.

Chronic gastrointestinal bleeding

Chronic gastrointestinal bleeding

Patients with chronic bleeding usually present with iron deficiency anaemia (see pp. 524–526).

Chronic blood loss producing iron deficiency anaemia in all men, and all women after the menopause, is always due to bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract. The primary concern is to exclude cancer, particularly of the stomach or right colon, and coeliac disease. Occult stool tests are unhelpful.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Chronic blood loss can occur with any lesion of the gastrointestinal tract that produces acute bleeding (see Figs 13.25 and 13.27). However, oesophageal varices usually bleed overtly and rarely present as chronic blood loss. Although uncommon in developed countries, hookworm is the most common worldwide cause of chronic gastrointestinal blood loss.

History and examination may indicate the most likely site of the bleeding, but if no clue is available, it is usual to investigate both the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract endoscopically at the same session (‘top and tail’), especially in males and postmenopausal females:

• Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is usually performed first. Duodenal biopsies should always be taken to diagnose coeliac disease, even if coeliac serology has been performed.

• Colonoscopy follows and any lesion should be biopsied or removed, though it is unsafe to assume that colonic polyps are the cause of chronic blood loss.

• Unprepared CT scanning is a reasonable test to look for colon cancer in frail patients.

• CT colonography can be used as an alternative to colonoscopy.

If gastroscopy, colonoscopy and duodenal biopsy have not revealed the cause, investigation of the small bowel is necessary. Capsule endoscopy is the diagnostic investigation of choice but currently has no therapeutic ability. Positive diagnostic yield varies from 60% to 85%, depending on series. Bleeding lesions can be identified and later treated with balloon-assisted enteroscopy.

Occasionally, intravenous technetium-labelled colloid may be used to demonstrate a potential bleeding site in a Meckel's diverticulum.

Management

Management

The cause of the bleeding should be dealt with, if found. Oral iron is given to treat anaemia (see pp. 525–526), although intravenous infusions are occasionally required. Some patients will require maintenance with regular transfusion as a last resort.

The Small Intestine

Anatomy

Anatomy

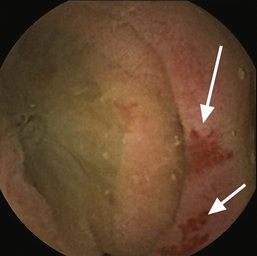

The small intestine extends from the duodenum to the ileocaecal valve. It is 3–6 m in length, and 300 m2 in surface area. The upper 40% is the duodenum and jejunum; the remainder is the ileum. Its surface area is enormously increased by circumferential mucosal folds that bear multiple finger-like projections called villi. On the villi, the surface area is further increased by microvilli on the luminal side of the epithelial cells (enterocytes) (Fig. 13.29).

Each villus consists of a core containing blood vessels, lacteals (lymphatics) and cells (e.g. plasma cells and lymphocytes). The lamina propria contains plasma cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, eosinophils and mast cells. The crypts of Lieberkühn are the spaces between the bases of the villi.

Enterocytes are formed at the bottom of the crypts and migrate toward the tops of the villi, where they are shed. This process takes 3–4 days. On its luminal side, the enterocyte is covered by microvilli and a gelatinous layer called the glycocalyx. Scattered between the epithelial cells are mucin-secreting goblet cells and occasional intraepithelial lymphocytes and Paneth cells. Most of the blood supply to the small intestine is via branches of the superior mesenteric artery. The terminal branches are end arteries; there are no local anastomotic connections.

Enteric nervous system

The enteric nervous system (ENS) controls the functioning of the small bowel; it is an independent system that coordinates absorption, secretion, blood flow and motility. It is estimated to contain 108 neurones (as many as the spinal cord), organized in two major ganglionated plexuses: the myenteric plexus between the muscular layers of the intestinal wall, and the submucosal plexuses associated with the mucosa. The ENS communicates with the central nervous system (CNS) via autonomic afferent and efferent pathways but can operate autonomously.

Coordination of small intestinal function involves a complex and only partly understood interplay between many neuroactive mediators and their receptors, ion channels, gastrointestinal hormones, nitric oxide and other transmitters. Acetylcholine, adrenaline (epinephrine), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and other hormones and opioids have been shown to have actions in the small bowel but the exact role of each is not yet clear.

Gut motility

The contractile patterns of the small intestinal muscular layers are primarily determined by the ENS. The CNS and gut hormones also have a modulatory role in motility. The interstitial cells of Cajal, which lie within the smooth muscle, appear to govern rhythmic contractions.

During fasting, a distally migrating sequence of motor events, termed the migrating motor complex (MMC), occurs in a cyclical fashion. The MMC consists of:

• a period of motor quiescence (phase I)

• a period of irregular contractile activity (phase II)

• a short (5–10-min) burst of regular phasic contractions (phase III).

Each MMC cycle lasts for approximately 90 minutes. In the duodenum, phase III is associated with increased gastric, pancreatic and biliary secretions. The role of the MMC is unclear, but the strong phase III contractions propel secretions, residual food and desquamated cells towards the colon. It is named the ‘intestinal housekeeper’.

After a meal, the MMC pattern is disrupted and replaced by irregular contractions. This seemingly chaotic pattern lasts typically for 2–5 hours after feeding, depending on the size and nutrient content of the meal. The irregular contractions of the fed pattern have a mixing function, moving intraluminal contents to and fro and aiding the digestive process.

Neuroendocrine peptide production

The hormone-producing cells of the gut are scattered diffusely throughout its length and also occur in the pancreas.

Gut hormones play a part in the regulation and integration of the functions of the small bowel and other metabolic activities, including appetite. Their actions are complex and interactive, both with each other and with the ENS (Box 13.17).

Physiology

Physiology

In the small bowel, digestion and absorption of nutrients and ions takes place, as does the regulation of fluid absorption and secretion. The epithelial cells of the small bowel form a physical barrier that is selectively permeable to ions, small molecules and macromolecules. Digestive enzymes, such as proteases and disaccharidases, are produced by intestinal cells and expressed on the surface of microvilli; others, such as lipases produced by the pancreas, are associated with the glycocalyx. Some nutrients are absorbed most actively in specific parts of the small intestine: iron and folate in the duodenum and jejunum, and vitamin B12 and bile salts in the terminal ileum, where they have specific receptors.

General principles of absorption

This process is non-specific, requires no carrier molecule or energy, and takes place if there is a concentration gradient from the intestinal lumen (high concentration) to the bloodstream (low concentration). Vitamin B12 can be absorbed from the jejunum by this means.

Facilitated diffusion

Absorption takes place down a concentration gradient but a membrane carrier protein is involved, conferring specificity on the process. Fructose transport is an example.

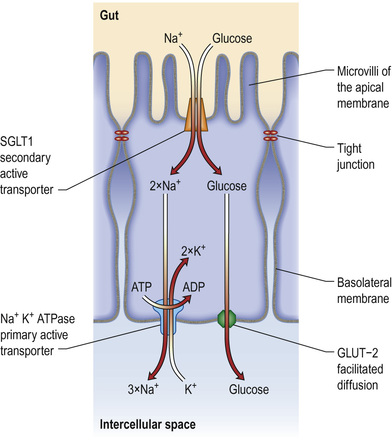

Active transport

Absorption occurs via a specific carrier protein, powered by cellular energy, allowing a substance to be transported against a concentration gradient. Many carrier proteins are powered by ion gradients across the enterocyte wall. For example, glucose crosses the enterocyte microvillous membrane from the lumen into the cell against a concentration gradient by using a co-transporter carrier molecule. This is the sodium/glucose co-transporter, SGLT1 (Fig. 13.30). The process is powered by the energy derived from the flow of Na+ ions from a high concentration outside the cell to a low concentration inside. The sodium gradient across the cell wall is maintained by a separate ATP-consuming Na+/K+ exchanger in the basolateral membrane. Glucose leaves the cell on the serosal side by facilitated diffusion via a sodium-independent carrier (GLUT-2) in the basolateral membrane.

Another active transport mechanism operates for Na+ absorption in the ileum using an Na+/H+ exchange mechanism, powered by the outwardly directed gradient of H+ across the cell membrane.

Absorption of nutrients in the small intestine

Dietary carbohydrate consists mainly of starch, with some sucrose and a small amount of lactose. Starch is a polysaccharide made up of numerous glucose units. In order to have a nutrient value, starch must be digested into smaller oligo-, di- and finally monosaccharides, which may then be absorbed. Polysaccharide hydrolysis begins in the mouth and is catalysed by salivary amylase, though the majority takes place under the action of pancreatic amylase in the upper intestine. The breakdown products of starch digestion are maltose and maltotriose, together with sucrose and lactose. These are further hydrolysed on the microvillous membrane by specific oligo- and disaccharidases to form glucose, galactose and fructose. These monosaccharides are then able to be transported across the enterocytes into the blood (see Fig. 13.30).

Protein

Dietary protein is digested by pancreatic proteolytic enzymes to amino acids and peptides prior to absorption. These enzymes are secreted by the pancreas as pro-enzymes and transformed to active forms in the lumen. Protein in the duodenal lumen stimulates the enzymatic conversion of trypsinogen to trypsin, and this, in turn, activates the other pro-enzymes, chymotrypsin and elastase.

These enzymes break down protein into oligopeptides. Some di- and tripeptides are absorbed intact by carrier-mediated processes, while the remainder are broken down into free amino acids by peptidases on the microvillous membranes of the enterocytes, prior to absorption into the cell by a variety of amino acid and peptide carrier systems.

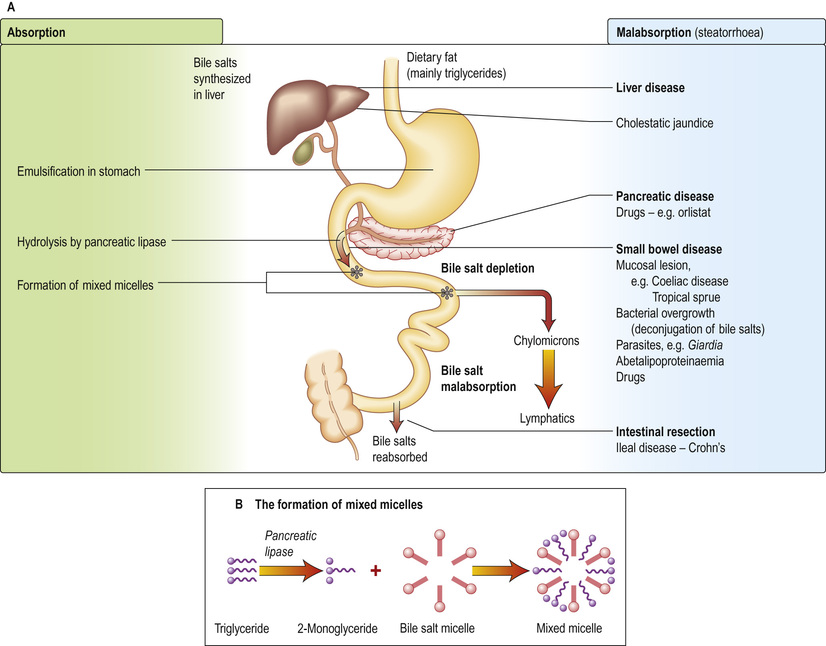

Fat

Dietary fat consists mainly of triglycerides with some cholesterol and fat-soluble vitamins. Fat is emulsified by mechanical action in the stomach. Bile containing the amphipathic detergents, bile acids and phospholipids enters the duodenum following gall bladder contraction. These substances act to solubilize fat and promote hydrolysis of triglycerides in the duodenum by pancreatic lipase to yield fatty acids and monoglycerides. Bile acids, phospholipids and the products of fat digestion cluster together with their hydrophilic ends on the outside to form aggregations called mixed micelles. Trapped in the centre of the micelles are the hydrophobic monoglycerides, fatty acids and cholesterol. At the cell membrane, the lipid contents of the micelles are absorbed, while the bile salts remain in the lumen. Inside the cell, the monoglycerides and fatty acids are re-esterified to triglycerides. The triglycerides and other fat-soluble molecules (e.g. cholesterol, phospholipids) are then incorporated into chylomicrons to be transported into the lymph.

Any unabsorbed lipids that reach the ileum delay gastric emptying via peptide YY, which is secreted by the ileum (called the ‘ileal brake’). This delay allows more time for absorption of lipids in the small intestine.

Medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs, fatty acids of chain length 6–12) are transported via the portal vein with a small amount of long-chain fatty acid. Patients with pancreatic exocrine or bile salt insufficiency can therefore supplement their fat absorption with MCTs.

Bile salts are not absorbed in the jejunum, so the intraluminal concentration in the upper gut is high. They pass down the intestine to be absorbed in the terminal ileum and are transported back to the liver. This enterohepatic circulation prevents excess loss of bile salts (see p. 443).

The pathophysiology of fat absorption is shown in Figure 13.31. Interference with absorption can occur at all stages, as indicated, giving rise to steatorrhoea (>17 mmol or 6 g of faecal fat per day).

Water and electrolytes

Large amounts of water and electrolytes, partly dietary but mainly from intestinal secretions, are absorbed, coupled with absorption of monosaccharides, amino acids and bicarbonate in the upper jejunum. Water and electrolytes are also absorbed paracellularly (between the enterocytes) down electrochemical and osmotic gradients. Additional water and electrolytes are absorbed in the ileum and colon, where active sodium transport is not coupled to solute absorption. Secretion of fluid and electrolytes occurs together to maintain the normal functioning of the gut. Secretory diarrhoea (see p. 426) can occur because of defects in intestinal secretory mechanisms.

Water-soluble vitamins, essential metals and trace elements

These are all absorbed in the small intestine. Vitamin B12 (see pp. 529–530) and bile salts are absorbed by specific transport mechanisms in the terminal ileum; malabsorption of both these substances often occurs following ileal resection.

Calcium

Calcium absorption is discussed on page 708.

Iron

Iron absorption is discussed on pages 523–524.

Response of the small bowel to antigens and pathogens

The small bowel has a number of mechanisms to prevent colonization and invasion by pathogens while simultaneously preventing inappropriate responses to foreign antigens or the indigenous bacterial population. At the same time, commensal bacteria maintain the integrity of the small bowel and play a major role in host physiology.

Mechanisms

• Continuous shedding of surface epithelial cells.

• The physical movement of the luminal contents.

• Colonization resistance – the ability of the indigenous microbiota to outcompete pathogens for a survival niche in the gut.

Innate chemical defence

• Enzymes such as lysozyme and phospholipase A2, secreted by Paneth cells at the base of the crypts, help ensure an infection-free environment in the gut, even in the presence of commensal bacteria.

• Antimicrobial peptides are secreted from enterocytes and Paneth cells in response to pathogenic bacteria. These include defensins, which are 15–20 amino-acid peptides with potent activity against a broad range of pathogens, including Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi and viruses.

• Trefoil peptides are a family of small proteins secreted by goblet cells. They consist of a three-loop structure with intra-chain disulphide bonds, which makes the molecules highly resistant to digestion. Their actions include stabilization of mucus, promotion of cell migration to injured areas, and promotion of repair. Three trefoil factors (TFFs) are found in humans (TFF1, TFF2 and TFF3), all of which have been implicated in the response to gastrointestinal injury in experimental models. Their molecular mode of action is not yet known.

Innate immunological defence

• Humoral defence. IgA is the principal mucosal antibody. It mediates mucosal immunity by agglutinating and neutralizing pathogens in the lumen and preventing colonization of the epithelial surface (Fig. 13.32). IgA is secreted from immunocytes in the lamina propria as dimers joined by a protein called the ‘joining chain’ (J-chain); in this form, it is known as polymeric IgA (pIgA). This pIgA is internalized by endocytosis at the basolateral membrane of enterocytes. It crosses the cell as a complex of pIgA/pIgAR and is secreted on to the mucosal surface.

• B-cell sensitization. Antigens from the lumen of the bowel are transported by M cells and dendritic cells in the follicle-associated epithelium (FAE). This covers Peyer's patches in the ‘dome’ region that contain abundant virgin B cells, helper T cells and antigen-presenting cells. Activated B cells then produce IgA locally and are programmed to home back to the lamina propria. They travel through mesenteric lymph nodes and then via the thoracic duct to the blood and back to the small bowel and other mucosal surfaces (such as the airways), where they undergo terminal differentiation into plasma cells. Homing back to the gut is facilitated by the α4β7-integrin on gut-derived lymphocytes binding to MAdCAM-1, uniquely expressed on blood vessels in the gut.

• Cellular defence. T lymphocytes also provide host defence and initiate, activate and regulate adaptive immune responses. Intestinal T lymphocytes occur principally in three major compartments:

– Organized gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), such as Peyer's patches, where mucosal T cell responses are generated, and after which cells leave the organized lymphoid tissue and home back to the mucosa.

– The lamina propria, containing mostly CD4 cells.

– The surface epithelium, where these lymphocytes are known as intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) and are mostly CD8 cells. T cells are sensitized to antigen in the Peyer's patch lymphoid tissue in a similar fashion to B cells, and pass through mesenteric lymph nodes into the thoracic duct and into the circulation, homing back to the small bowel to end up in the lamina propria or the epithelium. It is probable that IELs are cytotoxic cells, capable of killing virally or bacterially infected epithelial cells. CD4 cells in the lamina propria of healthy individuals are highly activated cells, probably protecting against low-grade infections, since loss of these cells, as in HIV infection, leads to colonization of the gut by protozoa such as cryptosporidia.

Commensal bacteria

The relationship between the hundred thousand billion microbes in the human gut and the host are only beginning to be appreciated. New molecular sequencing techniques have allowed the identification and classification of the gut microbiota. The use of metabonomics has aided the assessment of its functional output. There is increasing evidence that a reduction in the diversity of the gut microbiota is associated with a range of conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease and metabolic syndrome. Germ-free mice have essentially no mucosal immune system, showing that the abundant and activated immune system seen in healthy individuals is driven by the flora, without adverse effects. Bacteria also release chemical signals, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and lipoteichoic acid, which are recognized by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (see p. 127) present on a variety of intestinal cells, priming repair processes and enhancing the ability of the epithelium to respond to injury.

Oral tolerance

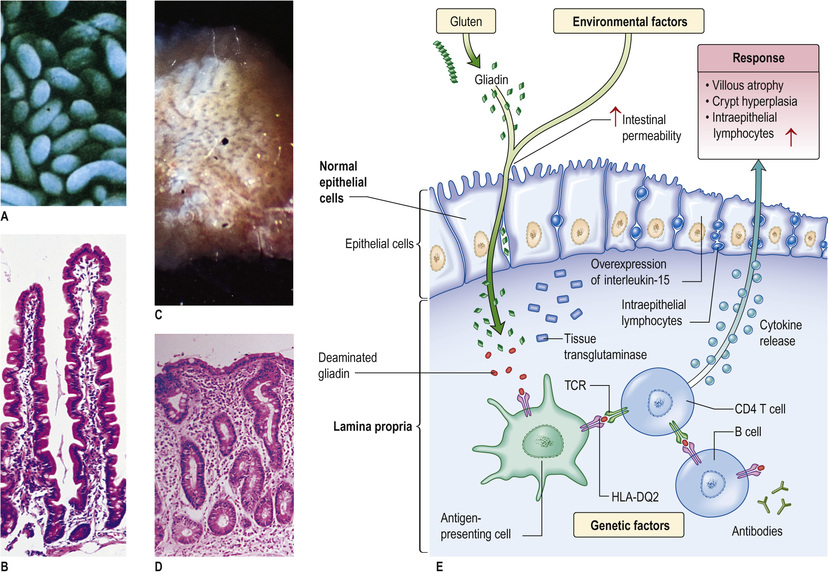

The immune system must guard against pathogens and toxins while avoiding an excessive response to the multiplicity of food antigens and commensal bacteria. The mechanisms by which tolerance occurs are undoubtedly multiple, including maintenance of barrier function to prevent excess antigen uptake, active inhibition via regulatory T cells, and dendritic cells that promote tolerogenic rather than immunogenic T-cell responses. All of these are likely to play a role in diseases such as coeliac disease, caused by an excessive T-cell response to gluten, or Crohn's disease, where tolerance to the indigenous bacterial population is defective.

Clinical features of small bowel disease

Clinical features of small bowel disease

Regardless of the cause, the common presenting features of small bowel disease are listed below. However, 10–20% of patients will have no diarrhoea or any other gastrointestinal symptoms.

• Diarrhoea is common and may be watery.

• Steatorrhoea occurs when the stool fat is >17 mmol/day (or 6 g/day). The stools are pale, bulky and offensive, and float (because of their increased air content), leaving a fatty film on the water in the pan and proving difficult to flush away.

• Abdominal pain and discomfort. Abdominal distension can cause discomfort and flatulence. The pain has no specific character or periodicity and is not usually severe.

• Weight loss is largely due to the anorexia that invariably accompanies small bowel disease. The calorie deficit due to malabsorption is small relative to the reduction in intake.

• Nutritional deficiencies of iron, vitamin B12, folate or all of these, leading to anaemia, are the only common deficiencies. Occasionally, malabsorption of other vitamins or minerals occurs, causing bruising (vitamin K deficiency), tetany (calcium deficiency), osteomalacia (vitamin D deficiency), or stomatitis, sore tongue and aphthous ulceration (multiple vitamin deficiencies). Oedema due to hypoproteinaemia is due to low intake and intestinal loss of albumin (protein-losing enteropathy).

Physical signs are few and non-specific. If present, they are usually associated with anaemia and the nutritional deficiencies described above.

Abdominal examination is often normal, but sometimes distension or, rarely, hepatomegaly or an abdominal mass is found. Visible peristalsis and high-pitched bowel sounds can indicate chronic subacute obstruction of the small intestine: for example, that due to stricturing Crohn's disease. Gross weight loss, oedema and muscle wasting are seen only in severe cases. A neuropathy, not always due to B12 deficiency, can be present.

Investigation of small bowel disease

Investigation of small bowel disease

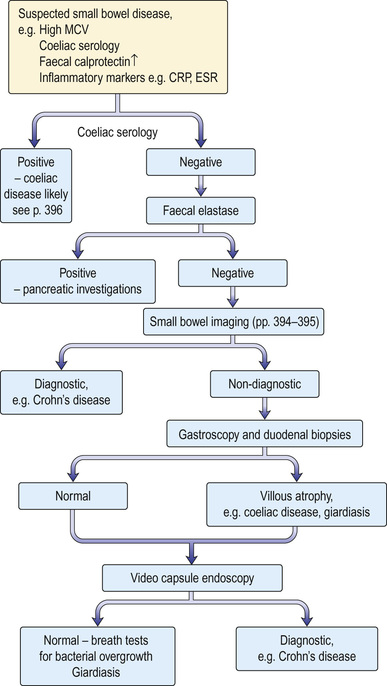

The emphasis in the investigation of malabsorption (Fig. 13.33) is on the structural features of the underlying disorder, rather than on the documentation of malabsorption itself.

Blood tests

• Full blood count (FBC) and film. Anaemia can be microcytic, macrocytic or normocytic, and the blood film may be dimorphic. Other abnormal cells (e.g. Howell–Jolly bodies, p. 553) may be seen in splenic atrophy associated with coeliac disease.

– Serum ferritin and iron saturation should be measured to differentiate iron deficiency from anaemia of chronic disorder (see p. 525). Remember that ferritin is an acute phase protein and is therefore difficult to interpret in the context of an inflammatory response for any reason.

– Serum B12 and serum and red cell folate should be measured. Red cell folate is a good indicator of the presence of small bowel disease. It is frequently low in both coeliac disease and Crohn's disease, which are the two most common causes of small bowel disease in developed countries.

• Inflammatory markers. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) should be assessed.

• Serum calcium and alkaline phosphatase. Low serum calcium and raised alkaline phosphatase may indicate the presence of osteomalacia due to vitamin D deficiency.

• Liver biochemistry and serum albumin. Prothrombin time is also measured.

• Immunological tests. Measurement of serum antibodies to endomysium and tissue transglutaminase is useful for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. These should always be accompanied by an assessment of total immunoglobulin levels.

• Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) testing. This is useful in coeliac disease, particularly if doubt exists about the diagnosis.

Investigation of small bowel anatomy

• MRI enteroclysis. This is cross-sectional imaging that does not involve radiation. It uses oral loading with water or a hypertonic solution to distend the small bowel lumen.

• Small bowel barium follow-through (see p. 363). This detects gross anatomical defects such as diverticula, strictures and Crohn's disease. Dilatation of the bowel and a changed fold pattern may suggest malabsorption but these are non-specific findings. Gross dilatation is seen in myopathic pseudo-obstruction. This is less used because of radiation.

• Small bowel biopsy. This is used to assess the microanatomy of the small bowel mucosa. Biopsies are usually obtained via an endoscope passed into the duodenum and should be well orientated for correct evaluation. The histological appearances are described in the sections on individual diseases. A smear of the jejunal juice or a mucosal impression should also be made when Giardia intestinalis infection is suspected.

• Ultrasound. This is a useful preliminary investigation, which can show thickened small bowel or distended loops.

• CT scanning. CT is used to look for small bowel wall thickening, diverticula, and extraintestinal features such as abscesses (e.g. in Crohn's disease).

• Video capsule enteroscopy. This technique is being widely used to visualize the small bowel lumen and mucosa directly along its entire length. It is particularly useful in the diagnosis of occult gastrointestinal bleeding.

Tests of absorption

These are required only in complicated cases: