6

Craving for Order

After the heated session in the conference room, welcome back to the studio. Having listened in on de Troy’s disquisition on the merits of destruction, I must admit that it’s hard to fault his argument that much of creation in language is just a by-product of erosion. If there is anything to quibble with, it is only with the ringing overtones of completeness. By trumpeting the forces of destruction, and boasting how much they can achieve, de Troy may have given the impression that erosion can account for all the elaborate structures in language. But here I beg to differ. Even though the forces of destruction can explain an enormous amount, they cannot account for everything. And some of the structures that erosion alone cannot explain happen to be among the most dazzling architectures found in the world’s languages.

One striking example is an edifice which I mentioned in Chapter 1, the verbal system of the Semitic languages. You may recall that the root of a Semitic verb is not a pronounceable string of consonants and vowels, like English ‘twist’ or ‘turn’, but an abstract entity which consists excusively of consonants. Roots such as Arabic s-l-m ‘be at peace’ or Hebrew š-b-t ‘rest’ (š stands for the sound sh) come to life only when they are inserted into a ‘template’: a sequence of sounds with empty slots for the three root-consonants. The Hebrew template ![]() , for instance, expresses the past tense (in the third person ‘he’), so when the root š-b-t is superimposed on this template, it yields šabat ‘he rested’ (hence ‘Sabbath’ – the day on which ‘He rested’). When the same root is inserted into other templates, it generates various other nuances of the verb. In the template

, for instance, expresses the past tense (in the third person ‘he’), so when the root š-b-t is superimposed on this template, it yields šabat ‘he rested’ (hence ‘Sabbath’ – the day on which ‘He rested’). When the same root is inserted into other templates, it generates various other nuances of the verb. In the template ![]() , for example, the root creates the form šobet ‘he rests’; the template

, for example, the root creates the form šobet ‘he rests’; the template ![]() yields hušbeta ‘she was made to rest’, and the template

yields hušbeta ‘she was made to rest’, and the template ![]() gives našbit ‘we will cause to rest’ or ‘we will bring to a standstill’ (typically said by striking workers). These are just a handful of simple examples, but as I mentioned earlier, there are many dozens of such templates, through which the Semitic languages can express every conceivable nuance of the verb.

gives našbit ‘we will cause to rest’ or ‘we will bring to a standstill’ (typically said by striking workers). These are just a handful of simple examples, but as I mentioned earlier, there are many dozens of such templates, through which the Semitic languages can express every conceivable nuance of the verb.

But isn’t it possible that the forces of erosion alone could have created such a system? After all, haven’t we just seen that the wear and tear of erosion can create finely laced structures like the French verbal system, with its criss-crossing of endings for different persons, tenses and other nuances? Why couldn’t a structure like the Semitic verb have developed in much the same way? The fact is that while erosion can create endings – reams and reams of them – the structure on display here is of an entirely different order. What makes the Semitic verbal architecture so special is not so much the sheer bulk of the templates, but rather the remarkable idea behind their design, the system of tri-consonantal roots and prefabricated vowel templates. There is just no way that erosion on its own could ever have come up with such an abstract algebraic scheme, a conceptual design of roots that cannot even be pronounced, but which are superimposed on vowel templates to produce every conceivable nuance of the verb. In fact, if there is anything in language which still seems to cry out for a conscious invention, this is surely it. For if it was not invented, how could people ever have stumbled across such an unusual idea?

And yet, there is an alternative explanation. We do not have to call on a deus ex machina to account for the origin of designs such as the Semitic verbal system, nor is there any need to discern the guiding hand of an architect in their construction. The following pages will try to show that it is within our grasp to understand how abstract linguistic designs could have arisen of their own accord. But if there is to be any chance of success in this enterprise, then we cannot pin all our hopes on erosion alone. We have to call on another essential element, one which the previous chapters have rather neglected.

Chapter 2 mentioned a triad of motives for language’s inner restlessness: economy, expressiveness and analogy. So far, however, only the first two of these motives have received much attention: economy, which causes the erosion in sounds, and expressiveness, which results in the inflationary erosion in meaning and drives the flow of metaphors from the concrete to the abstract. The role of analogy was acknowledged only summarily (in Chapter 4), as the cognitive mechanism behind our ability to find similarities between different domains, that is, our capacity for metaphorical thinking. Nevertheless, to understand how abstract designs can emerge in language, what will prove critical is exactly this overlooked third part of the triad, analogy, or the mind’s craving for order.

This chapter thus sets out to redress the balance, and explore the power of analogy. Analogy will soon emerge as the main element of ‘invention’ in the course of language’s evolution. Nonetheless, this type of invention does not spring from the design of any architect, nor does it follow any careful plan. The element of invention comes from thousands of spontaneous attempts by generation upon generation of order-craving minds to make sense of the chaotic world around them. And as we shall see, the force of such spontaneous innovations can sometimes accumulate to create imposing linguistic structures. By exploring the role of analogy in language change, we will also complete the survey of the central mechanisms of linguistic creation, and will thus be on course for our ultimate goal, projecting our findings onto the distant past in order to discover how the full complexity of language could gradually have evolved.

TO THINK IS TO FORGET A DIFFERENCE

In his story ‘Funes the Memorious’, the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges tells of a man called Funes, who lost consciousness when he was thrown off a horse and after regaining it found that he couldn’t forget anything he had ever seen or heard. ‘He remembered the shapes of the clouds in the south at dawn on the 30th of April of 1882, and he could compare them in his recollection with the marbled grain in the design of a leather-bound book which he had seen only once…’ But it is because of this unusual gift that Funes is incapable of any real thought – he is simply drowning in detail:

It was not only difficult for him to understand that the generic term dog embraced so many unlike specimens of differing sizes and different forms; he was disturbed by the fact that a dog at 3.14 (seen in profile) should have the same name as the dog at 3.15 (seen from the front) … I suspect that he was not very capable of thought. To think is to forget a difference, to generalize, to abstract. In the overly replete world of Funes, there were nothing but details, almost contiguous details.

Borges understood that the ability to pick out patterns, to draw analogies between unequal yet similar things, in short, to ‘forget a difference’, is at the very core of our intelligence. And the process of mastering a language is a good illustration of the role of analogy in enabling us to cope with an overwhelming amount of detail. As anyone who has tried to learn a foreign language will remember, the more order and regularity that can be picked out, the fewer the forms that need to be memorized individually. (An old German proverb says that keeping order is a crutch for those who are too lazy to search for things …) Were it not possible to extract any recurrent patterns from the mass of new information to be absorbed, our minds would simply be swamped by detail.

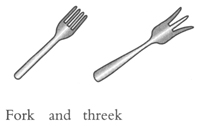

The ability to pick out patterns is not only crucial when learning a foreign language, it is just as vital to young children grappling with their mother-tongue. Babies do not imbibe their language with their mother’s milk, they have to work out the whole darned system for themselves, and the mass of information they have to take in is mind-blowing. The burden becomes lighter, however, the more recurrent patterns they can identify. So it’s no wonder that children act on the assumption that as much as possible in language should follow simple regular rules, hence cute errors such as ‘I goed’, ‘my twoth birthday’, ‘foots’, and so on. These mistakes are nothing other than perfectly sensible attempts to introduce order to corners of the language which happen to be quite messy and irregular. Sometimes, children even manage to outwit language’s most basic principle of the arbitrary sign. Not content with the idea that words mean something only by convention, they find meaningful patterns in the most random of words. An oft-cited case is that of a toddling clever-clogs, who, when presented with a fork with only three prongs, studied it intently and quite naturally pronounced it to be a ‘threek’.

As they grow up, children gradually come to learn which areas of their language do not abide by regular rules, so that most of the errors are corrected: ‘twoth’ is replaced by ‘second’, ‘foots’ and ‘mouses’ by ‘feet’ and ‘mice’, and so on. All the same, if such errors do persist beyond childhood, they can sometimes gain ground, and ultimately overtake some well-established forms. I mentioned in Chapter 2, for instance, that the nouns eye and cow originally had irregular plurals eyn and kine. But at some stage, the ‘errors’ eyes and cows caught on, and eventually usurped the original forms.

While the most ear-catching mistakes are certainly those made by young children, analogical innovations can also come from grown-ups. Here is one recent example which is much more likely to have originated from the speech of teenagers than toddlers, but which is nonetheless based on very similar analogical principles. Some time in the early 1960s a new coinage made its way into British English, and quickly gained currency after featuring in the Beatles’ film A Hard Day’s Night. In one scene, a pompous advertising agent mistakes George Harrison for a ‘focus group’ participant, and asks for his opinion on some new designs of shirt:

AGENT: Now, you’ll like these … They’re ‘fab’ and all the other pimply hyperboles.

GEORGE: I wouldn’t be seen dead in them. They’re dead grotty.

AGENT: Grotty?

GEORGE: Yeah, grotesque.

AGENT: (to secretary) Make a note of that word … I think it’s rather touching really.

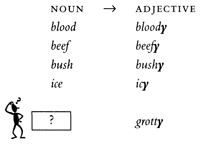

So the adjective ‘grotty’ began as a groovy abbreviation of ‘grotesque’, a simple case of laid-back effort-saving. But at this point in the story the order-craving mind begins to make its presence felt. As the dialogue shows, the relation of ‘grotty’ to its forebear ‘grotesque’ was initially still transparent to all who used it. But before too long, the connection with ‘grotesque’ was forgotten and ‘grotty’ set itself up in its own right, as a word meaning ‘dirty’ or ‘shabby’. And as it happens, the new word ‘grotty’ fitted neatly into a simple regular pattern in the language, whereby many English nouns give rise to adjectives through adding on the ending -y:

So some time around the early 70s, speakers made the following entirely reasonable inference: if adjectives like bloody and beefy are related to the nouns blood and beef, then what could the noun corresponding to the adjective grotty be, except …

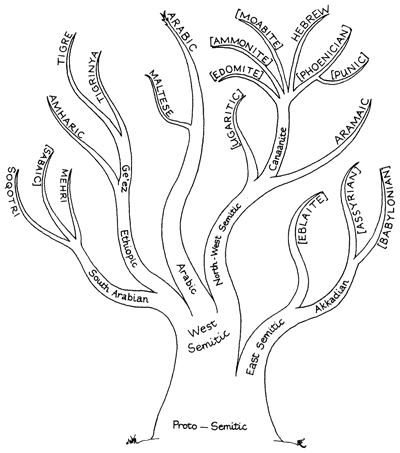

And thus the noun ‘grot’ was born, meaning something like ‘dirt’ or ‘rubbish’. This new coinage seems to have been popularized by a BBC television series of the late 70s, in which a character called Reginald Perrin makes a fortune from a chain of shops called ‘Grot’ that sell goods with ‘terminally built-in obsolescence’.

Linguists call the type of analogy that produced ‘grot’ ‘back formation’, because in terms of historical accuracy, it actually went backwards. Unlike ‘bloody’, for instance, which indeed had the noun ‘blood’ as its forebear, ‘grotty’ began life as an abbreviation of another adjective, ‘grotesque’. (Of course, if one were to trace the ancestry of ‘grotty’ itself much further back, it would emerge that the adjective from which it sprang, ‘grotesque’ ultimately does go back to a noun, but a different one, grotto, meaning ‘cave’. As far as ‘grot’ is concerned, however, this early history is beside the point.) From a historical perspective, then, ‘grotty’ did not owe its existence to a noun ‘grot’, and the analogy that produced ‘grot’ was incorrect. But the speakers who made this inference couldn’t give two hoots about the historical perspective. All they did was recognize a pattern (NOUN+y → ADJECTIVE) and apply it, albeit in reverse, to a new adjective that seemed to fit, thereby making the adjective conform to the regular pattern.

Such an analogical back formation may seem rather strained at first, but inferences of this kind are extremely common, and the history of English provides dozens of other examples. The noun ‘greed’, for instance, emerged in the seventeenth century through exactly the same type of back formation, when speakers ‘incorrectly’ applied the pattern NOUN+y → ADJECTIVE to the adjective ‘greedy’, which did not have a noun counterpart at the time. New verbs can also emerge through such analogical innovations, when common patterns are applied in reverse. The pattern VERB+or → NOUN, for instance, creates many nouns from verbs: ‘visit-or’ (from ‘visit’), ‘govern-or’ (from ‘govern’), ‘vend-or’, ‘survey-or’, and so on. But in the eighteenth century the pattern was incorrectly applied backwards to the nouns ‘editor’ and ‘legislator’ (both of which came from Latin nouns), to create the new verbs ‘edit’ and ‘legislate’. Who knows, perhaps at some stage in the future, similar back formations will make writers ‘auth books’, medics ‘doct patients’, and ships ‘anch in harbour’.

Other back formations produced the English singular nouns ‘cherry’ and ‘pea’. ‘Cherry’ comes from Old Northern French cherise, a word which happened to end with an s sound although it wasn’t plural -just like ‘cheese’ today. In the fourteenth century, some speakers falsely assumed that cherise was an instance of the common pattern NOUN+S → PLURAL, so they applied this pattern in reverse, and produced the singular form ‘cherry’. This must initially have sounded just as ‘wrong’ to educated speakers as ‘one chee’ would to us today. ‘Pea’ had a similar history, as it derives from an earlier singular ‘pease’ (which still survives in the set phrase ‘pease-pudding’). But around 1600 ‘pease’ was misinterpreted as a plural, and so ‘pea’ emerged as the singular form. Such back formations continue even now, as illustrated by the child who was overheard complaining that there was only ‘one Weetabick’ left in the packet.

All this goes to show that the course of change is determined not only by ‘blind’ effort-saving forces, heedless of all but the phonetic environment, but also by the craving for order of generation upon generation of speakers. The mind is constantly on the lookout for any signs of recurrent patterns, because the more regularity it can recognize, the easier its task of coping with the mass of linguistic detail it has to absorb. When the mind picks out a recurrent pattern, it naturally tries to extend it to whatever seems to fit. And since speakers rarely know (nor care) about earlier stages of the language, they can happily extend a pattern even to those forms which never had anything to do with it in the first place.

The birth of ‘grot’ was the outcome of one extremely simple sequence of effort-saving and analogy: a hip abbreviation followed by an extension of the pattern (NOUN+y → ADJECTIVE) to the ‘inappropriate’ ‘grotty’. And it may require a considerable stretch of the imagination to believe that such a simple cycle could have anything to do with the creation of abstract linguistic designs, let alone highly sophisticated ones. And yet the following pages will argue that a series of similar cycles is capable of great feats. In particular, the interplay between erosion and analogy is what must have been behind the development of the Semitic verbal system.

* * *

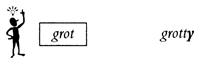

Before delving into the verbal system of the Semitic languages, a few words about their cultural history are in place. The Semitic languages have a written history spanning more than 4,500 years. The original heartland of the Semites seems to have been the Arabian peninsula, whence Semitic-speaking tribes spread in different waves into large areas of the Near East and North Africa (see map).

The oldest known member of the language family is Akkadian, which is attested from around 2500 BC, and is thus one of the earliest written languages of all. (Only Sumerian and Ancient Egyptian can beat that record.) Akkadian was spoken in Mesopotamia, the land ‘between the rivers’, the Euphrates and the Tigris, in an area roughly corresponding to today’s Iraq. The name of the language derives from the city of Akkade, founded in the twenty-third century BC as the imperial capital of the first ‘world conqueror’, King Sargon. Later on, after 2000 BC, Akkadian diverged into two main varieties, Babylonian in the south of Mesopotamia and Assyrian in the north, both of which were to become the languages of powerful empires. Speakers of Akkadian (both Babylonian and Assyrian) dominated the political and cultural horizon of the Near East up until the sixth century BC. Their political star may have waxed and waned, but for a good part of 2,000 years, Mesopotamian emperors, from Sargon in the third millennium BC to Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar in the first, would lay claim to the title ‘King of the Universe’, ruling over the ‘the four corners (of the earth)’. More stable than the power of the sword, however, was the cultural hegemony of Mesopotamia over the whole region. The Akkadian language shaped the dominant canon for much of the Near East in religion, the arts, science and law, and was used as a lingua franca, the means of diplomatic correspondence. Petty governors of provincial Canaanite outposts, mighty Anatolian kings, and even Egyptian Pharaohs wrote to one another in Akkadian. Languages across the Near East also borrowed many scientific and cultural terms from Akkadian, a few of which may even be recognized by English speakers today. The Jewish expression mazel tov ‘good luck’, for example, is based on the Hebrew word mazal luck’, which was borrowed from the Akkadian astrological term mazzaltu ‘position (of a star)’.

Family tree of the Semitic languages

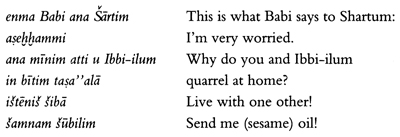

But after nearly 2,000 years of cultural supremacy, the political demise of Assyria and Babylon in the sixth century BC ushered in an age of rapid decline, and within a few centuries both the Akkadian language and its writing system fell into oblivion. Hundreds of thousands of clay tablets, the product of two thousand years of civilization, lay forgotten in the desert sands for two more millennia, to be rediscovered and deciphered only in the nineteenth century. Since then, an almost unbelievable wealth of texts has been recovered from the soil of Iraq and neighbouring countries, and has opened up a unique perspective on one of history’s greatest civilizations. The texts encompass almost every imaginable genre, from poetry (such as the Epic of Gilgamesh) to legal documents (such as the Code of Hammurabi), not to mention religious incantations, histories, royal inscriptions of heroic deeds, diplomatic correspondence, monolingual and multilingual dictionaries, mathematical and astronomical texts, medical treatises, and a seemingly endless quantity of administrative documents. One of the most revealing genres, however, is that of ordinary private letters dealing with quotidian subjects, from commercial haggling to domestic disputes. Here, as one example, is perhaps the first ever recorded endeavour to calm family tensions. This short missive was written in the twenty-third century BC, and shows that on some issues, little has changed in more than 4,000 years:

A letter from the Old Akkadian period, twenty-third century BC

The other languages of the Semitic family are attested from a much later period. The next in line is the Canaanite branch of Semitic, which includes Hebrew and other closely related varieties such as Phoenician, Moabite and Ammonite. Some time in the second millennium BC, the Canaanites developed the first ever writing system for the common man, the alphabet. (Which group among them was the first to do so is still a moot point.) Hebrew was spoken by the Judeans and Israelites until the last few centuries BC, when it was displaced by Aramaic, but it survived as the religious and literary language of the Jews, and was revived in the twentieth century as the language of modern Israel. Phoenician was the language of the seafaring people of the Lebanese coastal cities Tyre, Sidon and Byblos. The entrepreneurial spirit of the Phoenicians is responsible, among other things, for the exportation of the Canaanite alphabet to the Greeks, and for the word ‘Bible’. (The Greeks called papyrus-paper ‘Byblos’, because that was the city from which they imported this commodity. The word then assumed the sense of ‘book’, and thence ‘The Book’.) The Phoenicians also founded various trading colonies in Europe and North Africa, one of which was Carthage (Kart-![]() adasht or ‘Newtown’ in the Punic dialect of Phoenician).

adasht or ‘Newtown’ in the Punic dialect of Phoenician).

Another sibling in the Semitic family, Aramaic, has its roots in today’s Syria. During the first millennium BC, Aramaic speakers spread across a much wider area, so that Aramaic eventually became the street-lingo in Palestine and even in Assyria and Babylon. In the sixth century BC, after the fall of Babylon, Aramaic even became the official language of the Achaemenid (Persian) empire. Some parts of the Old Testament, such as the Book of Daniel, are written mostly in Aramaic, and a later dialect, Syriac, became the vehicle of important Christian literature and exegesis. Varieties of Aramaic are still spoken in some towns and villages of Syria and Northern Iraq today.

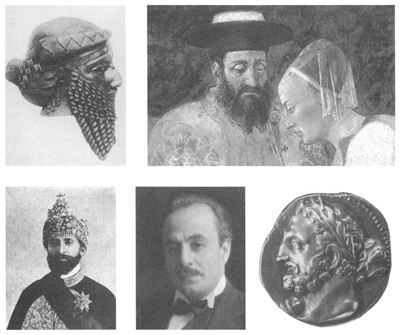

Some famous speakers of Semitic languages. Clockwise from top left: Sargon of Akkade, the first ‘World Emperor’, twenty-third century BC (spoke Akkadian); King Solomon of Judah, tenth century BC (spoke Hebrew) and the Queen of Sheba (probably spoke South Arabian); Hannibal, Carthaginian general, 247–182 BC (spoke Punic, a dialect of Phoenician); Khalil Gibran, Lebanese-American poet, 1883–1931 (spoke Arabic); Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, 1892–1975 (spoke Amharic)

Classical Arabic is attested from a much later period, and is the language of the Qur’an (seventh century AD). Many words in European languages, especially those to do with science, medicine and mathematics were borrowed from Arabic. Notable examples are the words ‘cipher’ and ‘zero’, which through different routes both derive ultimately from the same Arabic word ![]() ifr, meaning ‘nothing’ (

ifr, meaning ‘nothing’ (![]() stands for the sound ts). The word ‘algebra’ is also a loan from Arabic al jabr ‘the setting-together (of broken things)’. With the expansion of Islam, Arabic spread from the Arabian peninsula to large parts of the Near East and North Africa, and is today spoken by around 150 million people.

stands for the sound ts). The word ‘algebra’ is also a loan from Arabic al jabr ‘the setting-together (of broken things)’. With the expansion of Islam, Arabic spread from the Arabian peninsula to large parts of the Near East and North Africa, and is today spoken by around 150 million people.

Finally, on the southern tip of the Arabian peninsula, there are Semitic languages quite different from Arabic, which belong to another branch of the family. These are the South Arabian languages, one of which was spoken in the Kingdom of Saba (biblical Sheba). Speakers of South Arabian languages also emigrated to Africa by crossing the narrow straits between the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, eventually giving rise to the Semitic languages of Ethiopia, such as Amharic and Tigré.

A MYSTERY IN FIVE PARTS

One might well imagine that with such a lineage – longer than that of any other language family – it would be a straightforward matter to discover how the Semitic verbal system came into being. Surely, all that one would need do is look carefully at written records from the last forty-five centuries, and observe ‘in the act’ how the verbal system gradually evolved. Alas, the reality is far less tractable, for when the Semitic languages stepped on to the stage of history in the third millennium BC, the characteristic traits of their verbal system, the consonantal roots and the abstract design of the vowel templates, were already fully in place. So although history dawned so early for the Semitic languages, the birth of their verbal system is nevertheless hidden deep in prehistoric darkness.

This does not mean, however, that all hope need be abandoned just yet. If we are prepared to settle for something less than absolute historical certainty, then the situation improves considerably, for we are lucky enough to have various fossilized relics embedded in the crevices of Semitic languages which can give vital clues as to earlier periods in the life of their verbal system. So by identifying these remnants and piecing them together, we can get a pretty good idea, at least in principle, of how the whole edifice could have arisen.

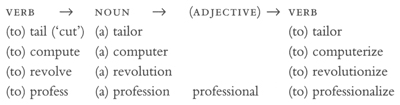

I invite you, therefore, on a historical mystery tour which will take us from Africa to Northern Europe, and from the present to as far back as eight millennia ago. The prize will be an understanding of how a system could have emerged which perhaps of all linguistic structures comes closest to defying the claim that language was never ‘invented’. In order to reach this goal, we will rely on five major clues from the Semitic languages, as well as from languages closer to home. The first clue, the ‘Quirk Vowel’, will reveal the simple origins of the Semitic verb, and suggest that once upon a time the prehistoric ancestor of the Semitic languages must have had completely ‘normal’ verbal roots, pronounceable words containing both consonants and vowels. The second clue, ‘Mutant Vowels and Hollow Verbs’, will suggest that the first step which this ancient ancestor may have taken towards the root-and-template system was the change of just one vowel inside the root. With the third clue, ‘Geese, Guests, and German Cardinals’, we will draw on parallels from English and German in order to discover what may have caused this vowel mutation inside the root. The fourth clue, ‘Revolving, Revolutions, and Revolutionizing’, will suggest how verbs with exactly three consonants could have risen to dominance in Semitic. And finally, the last clue, ‘Syncope and the Liberation of Consonants’, will expose the cycles of erosion and analogy which must have hatched some of the vowel templates, and in so doing created the concept of a purely consonantal root.

But before setting off, a word of warning. As complex structures go, the Semitic verbal system is not easily out-complicated. So trying to uncover its origin does not make for light bedtime reading. The developments involved here are – to put it mildly – tricky, and getting to grips with them is not for the fatigued or faint-hearted. So if you wish, you can safely skip the rest of this chapter and jump straight to the next. But if you do stick with me, and go where many philologists fear to tread, the reward will be the satisfaction of cracking one of the hardest nuts in language.

CLUE 1: ‘THE QUIRK VOWEL’

In the complex systems of language, there is hardly any area that is entirely devoid of blots and blemishes, and the Semitic verb is no exception. For learners these irregularities can be a nightmare, but for linguists bent on uncovering the origin of the system they can be a godsend, as they can lead to dark undisturbed corners littered with ancient linguistic fossils, and thus provide vital clues to the earliest days of the verbal system. Perhaps the most conspicuous of all these irregularities is the ‘quirk vowel’, which at first sight seems to mar the clean lines of the verbal system. The language which gives the best idea of what this quirk vowel is about is the oldest sibling in the Semitic family, Ancient Akkadian.

Earlier on, I mentioned that the root of Semitic verbs contains only consonants, and that the vowels only belong to the templates that determine the verb’s various nuances. Here are a few simple templates from Akkadian, where, as before, the fictional root ![]() is used (with the fictional meaning ‘snog’) to stand for the three consonants of any root. The italicized sounds belong to the templates themselves:

is used (with the fictional meaning ‘snog’) to stand for the three consonants of any root. The italicized sounds belong to the templates themselves:

At first sight, there doesn’t seem to be anything especially untoward in the variation between ![]() and

and ![]() . After all, the entire template system is based on the use of different vowels between the root consonants, so one more vowel change seems neither here nor there. But the variation between u and i in the past tense is something of quite a different nature from the abstract design of the other templates. In the other templates, a change of vowel is used to make some grammatical distinction and mark a particular nuance such as tense or person. The variation here, however, does not play any grammatical role, since the change between the vowels u and i does not mark any different nuance of meaning: it doesn’t change the tense, nor does it mark the verb as passive, intensive, or anything of the kind. The choice of vowel here is entirely arbitrary, and when you learn the language, you simply have to memorize which root goes with which vowel in the simple past, just as you have to memorize the gender of every French or German noun.

. After all, the entire template system is based on the use of different vowels between the root consonants, so one more vowel change seems neither here nor there. But the variation between u and i in the past tense is something of quite a different nature from the abstract design of the other templates. In the other templates, a change of vowel is used to make some grammatical distinction and mark a particular nuance such as tense or person. The variation here, however, does not play any grammatical role, since the change between the vowels u and i does not mark any different nuance of meaning: it doesn’t change the tense, nor does it mark the verb as passive, intensive, or anything of the kind. The choice of vowel here is entirely arbitrary, and when you learn the language, you simply have to memorize which root goes with which vowel in the simple past, just as you have to memorize the gender of every French or German noun.

This arbitrary vowel in the past tense of all Akkadian verbs is what I have called the ‘quirk vowel’. But what is such a random vowel doing in the middle of the root-and-template system, where vowels are only meant to mark the grammatical nuance? It is tempting to write off the quirk vowel as just a silly irregularity, whose only purpose is to mess things up and make life unnecessarily difficult for learners. But it turns out that there is much more to the quirk vowel than meets the eye. There is every reason to assume, in fact, that the quirk vowel is an extremely old feature, whose unruliness contains critical clues to the origin of the whole Semitic verbal system.

The first reason to suspect that the quirk vowel is a very old fixture in the system is its location. The quirk vowel does not crop up in fancy nuances such as ‘I will cause to snog’ or ‘I was made to snog intensely’. Rather, it appears in the most basic and common nuance: the simple past ‘I snogged’. And when linguists discover a situation where the simplest forms behave erratically, while more elaborate ones are better behaved, their suspicion is soon aroused, because the simplest and most common words are often those that have managed to cling on to ancient traits that have disappeared elsewhere in the language.

A good example of just that type of conservatism is provided by one particular English verb. In earlier stages of English, all verbs maintained a distinction between singular and plural in the past tense: he ‘herde’ but they ‘herden’ (see Chapter 3). In modern English this distinction has long been levelled out, so that verbs nowadays only have one form: he/they ‘heard’. There is, however, a single but notable exception. Perhaps the most common verb of all, the ubiquitous ‘be’, has clung on to this long forgotten distinction, and it still shows a difference between ‘he was’ and ‘they were’.

The reason why such frequent words can sometimes cling on to outmoded traits that have long been shed elsewhere in the language is their extreme familiarity. The most common words are heard so often that they can quickly become indelibly imprinted in the minds of new generations of learners, and thus withstand even drastic overhauls in the rest of the language. So when a certain trait is found only in the simplest and most common words or forms, there are good reasons to believe that this trait is a survivor from olden times. And since the quirk vowel in Semitic appears in the simplest and most common of the nuances, there is already fertile ground for suspicion that some very old feature is hidden behind the façade of irregularity.

What is more, it turns out that the quirk vowel is not just a whim of Akkadian, but that it crops up in other Semitic languages too. Consider the two corresponding verbs in Arabic:

k-t-m |

(‘cover’) |

aktum |

f-t-l |

(‘twist’) |

aftil* |

Arabic is not a descendant of Akkadian but a sister language (see tree), and thus could not have inherited the quirk vowel from Akkadian. This suggests that the quirk vowel is a feature with a very long pedigree, and that it was already in place in Proto-Semitic, before the Semitic languages had started diverging from one another, at the very least 5,000 years ago.

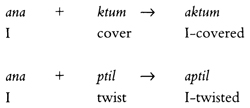

Still, even if the quirk vowel turns out not to be a random quirk after all, but a very ancient feature, how does it help us in our quest? Let us invent a simple thought experiment, and suppose for a moment that the only form of the Semitic verb that was known was this simple past tense with the quirk vowel. If we didn’t know a thing about any of the other templates, and only had Akkadian forms like aktum or aptil to go on, would there be any reason to suppose that the Semitic verb was anything out of the ordinary? And would there be any grounds for suspecting that roots were made up only of consonants? Not at all. If the only evidence available was the simple past tense, the most convincing analysis would surely be that the verb a-ktum ‘I covered’ is made up of the root ktum, and a prefix a- (‘I’), and that the verb a-ptil ‘I twisted’ is similarly made of a- and the root ptil. Just as vowels are a part of the root in English verbs like stab, step or spit, the most obvious explanation for the forms a-ktum and a-ptil would be that the vowels u and i belong to the roots ktum and ptil

In fact, it wouldn’t even be too difficult to draw up an explanation for how the prefix a- came to join forces with the root in forms like a-ktum or a-ptil One could simply say that a- must have come from a pronoun which eroded and fused with the verb, just like the pronouns of colloquial French from the previous chapter, which coalesced with the verb to become prefixes: je + aime → jem. The Semitic forms could thus be explained along the same lines: an original pronoun ‘I’, which comparative evidence suggests started out as ana, was reduced to just a and fused with the verb:

In short, if the only verbal form around in Semitic were the simple past tense, then there would really be nothing at all unusual about its design, nor about the ‘quirk vowel’ it contained. The most obvious explanation would simply be that this vowel had always been a part of roots like ktum or ptil

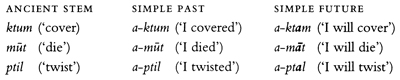

By now, the aim of this thought experiment is perhaps becoming clearer. Since we know the ‘quirk vowel’ is such an ancient feature, the most likely explanation for why it is there is that it is a relic from a much earlier stage of the language, a time before the root-and-template system had started to develop. In other words, the best explanation for how the quirk vowel got to be there is that it was there all along. It must have been there even before the design of the consonantal root was dreamt of, when the ancestor language had roots which looked like ktum or ptil. Now, when a root is a pronounceable string of sounds like this, it is sometimes called a ‘stem’, so to avoid confusion, I will use the term ‘ancient stems’ from now on to refer to the roots in the prehistoric period, which still contained both consonants and vowels.

To sum up then, the distant ancestor of the Semitic languages must have had a fairly ‘normal’ verbal system, with stems like ktum or ptil. The irregular quirk vowel is simply a relic from that distant age – it is the original vowel of these ancient stems. At a later stage of the language, however, and in a way which remains for us to determine, the verbal system somehow underwent a complete transformation, through which those ancient stems gave way to the purely consonantal roots. The more elaborate templates in Semitic derive from that later stage, when the vowel of the ancient stem had been all but eliminated (remaining only in the simple past) and had given way to the abstract design of the purely consonantal root. So, for example, in the nuance ‘I will snog intensely’, only one template ![]() is used with all roots, regardless of the ‘quirk vowel’ in the simple past.

is used with all roots, regardless of the ‘quirk vowel’ in the simple past.

From the point of view of the mature root-and-template system, therefore, the quirk vowel may look like an unmotivated irregularity, one that only detracts from the clean beauty of the architecture. But the quirk vowel allows us to peer back into the murk of prehistory, to a time before the consonantal root was even conceived. The simple past was such a common form that it acted as shelter, and managed to protect the quirk vowel from the drastic overhaul of the rest of the system.

CLUE 2: MUTANT VOWELS AND HOLLOW VERBS

What could have transformed the ancient stems, those pronounceable chunks with both consonants and vowels, into the abstract algebraic system of purely consonantal roots? Fortunately, there are some other relics strewn around the Semitic verb which give us clues about the early days of its evolution, and suggest that the thousand-mile march towards the root-and-template system may have started as early as eight millennia ago, with just one small step. A single ‘mutation’ may have developed in the vowel of the ancient stem, and assumed the function of a tense distinction, rather like in the English verbs sit-sat or drink-drank.

To uncover the traces of this early vowel mutation, we have to go scavenging among irregularities again, this time among verbs with an irregular number of consonants. I mentioned earlier that roots in the Semitic languages generally comprise three consonants. The qualifier ‘generally’ was necessary, because there are some roots, such as m-t ‘die’, which fall short of this regular pattern and have only two consonants. These verbs are sometimes called ‘hollow’, because what would have been their middle consonant is empty.

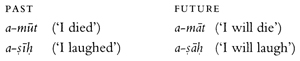

Now, in the simple past tense of Akkadian, these hollow verbs misbehave only mildly. Just like normal verbs like a-ktum or a-ptil, the hollow verbs show the quirk vowel u or i in the simple past, and so they deviate only in that they have one fewer consonant: a-mūt ‘I died’; a-nīk ‘I had sex’; a-![]() ī

ī![]() ‘I laughed’ (the hollow verbs tend to belong to the most basic level of vocabulary). When one moves to the future tense, however, one finds that the hollow verbs begin to misbehave much more wildly. The regular verbs form their future tense with an elaborate template

‘I laughed’ (the hollow verbs tend to belong to the most basic level of vocabulary). When one moves to the future tense, however, one finds that the hollow verbs begin to misbehave much more wildly. The regular verbs form their future tense with an elaborate template ![]() but the hollow verbs have a much simpler future pattern: they simply change their ‘quirk vowel’ to a:

but the hollow verbs have a much simpler future pattern: they simply change their ‘quirk vowel’ to a:

The behaviour of the hollow verbs in the future tense can be called a-mutation: the vowel of the ancient stem (i or u) changes to a. This behaviour is quite similar to that of English pairs like sit-sat, spit-spat, or drink-drank, only that in English it is of course in the past tense that the vowel changes to a.

At first sight, the hollow verbs may seem like just another eccentricity in the elegant architecture of the Semitic verb. Instead of conforming to the proper template for the future tense, the only thing they deign to do is change their single vowel to a. But these irregularities should not be dismissed too lightly, since there are once again good reasons to believe that the a-mutation is an extremely old pattern, a relic from the first steps that the ancestor of the Semitic languages was taking in developing the root-and-template system.

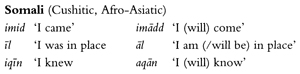

There are various clues within the Semitic languages themselves which suggest the extreme antiquity of the a-mutation, but perhaps the most compelling evidence comes from languages further afield. The Semitic languages are distantly related to some language families in Africa, including the Berber languages of Morocco and the Cushitic languages of Ethiopia and Somalia. Semitic, Berber and Cushitic are members of what scholars nowadays call the Afro-Asiatic language family. No one can say for sure when the Semitic branch of Afro-Asiatic started diverging from the Cushitic branch, but based on the linguistic distance between the languages, linguists believe that it must have been at the very least 8,000 years ago. While none of the other Afro-Asiatic languages has a root-and-template system like that of Semitic, many of them do show a suspiciously familiar vowel mutation between the tenses. In the Cushitic language Somali, for example, one comes across forms like these:

In fact, using the evidence from such verbs in various Cushitic languages, linguists have come to the conclusion that in the ancestor language of Cushitic (and perhaps of other Afro-Asiatic branches) there was a vowel mutation from u or i in the past tense to a in the present/future tense. So it would seem that the a-mutation goes back even beyond the earliest stratum of Semitic, to a time before Proto-Semitic started diverging from Proto-Cushitic, probably at least 8,000 years ago.

The evidence thus suggests that the a-mutation is an extremely old pattern. But if this is so, then why is this mutation only found in a few exceptional hollow verbs? Why is it that the regular verbs form their future tense with an entirely different pattern (the template ![]() )? The most plausible explanation seems to be that the a-mutation was originally much more widespread, and was also the fashion among the normal three-consonant verbs. So, for example, the future tense of the verb a-ktum ‘I covered’ would simply have been a-ktam. But at a later stage, the a-mutation was displaced by the more elaborate future template (as a part of the general overhaul the system underwent with the development of the mature root-and-template system). The few Akkadian verbs that still show the a-mutation are just the last survivors, those which managed to hold out against the new template most obstinately. So even if from the later perspective of the mature Semitic system the a-mutation may look like nothing more than an unmotivated and rather embarrassing irregularity, the a-mutation was probably around long before the other templates had even been thought of.

)? The most plausible explanation seems to be that the a-mutation was originally much more widespread, and was also the fashion among the normal three-consonant verbs. So, for example, the future tense of the verb a-ktum ‘I covered’ would simply have been a-ktam. But at a later stage, the a-mutation was displaced by the more elaborate future template (as a part of the general overhaul the system underwent with the development of the mature root-and-template system). The few Akkadian verbs that still show the a-mutation are just the last survivors, those which managed to hold out against the new template most obstinately. So even if from the later perspective of the mature Semitic system the a-mutation may look like nothing more than an unmotivated and rather embarrassing irregularity, the a-mutation was probably around long before the other templates had even been thought of.

Let’s now put together everything we have uncovered so far: some time in the prehistoric period, the ancestor of the Semitic languages must have started out with ‘normal’ verbs, with sturdy stems like mūt, nīk, ktum or ptil, which had both consonants and vowels to their name. The first step in the evolution of the root-and-template design may have been taken as early as 8,000 years ago, when, for some strange reason, a vowel mutation emerged in the future tense: the vowel of the ancient stem changed to a:

In itself, this mutation pattern may not seem such a huge leap forward. Nevertheless, the a-mutation is a defining moment in the evolution of the Semitic verbal design, since the kernel of a new concept has been formed, from which the notion of the consonantal root will later spring: the idea that a verb can keep the same consonants, but change the vowels between them to mark nuances like tense.

Now this is all very well, of course, but suggesting that the first step was the emergence of one vowel mutation still doesn’t say anything about how this first step could ever have been taken. What could have galvanized the change of vowel in the future tense from i or u to a? The next clue will help us tackle exactly this question.

CLUE 3: GEESE, GUESTS AND GERMAN CARDINALS

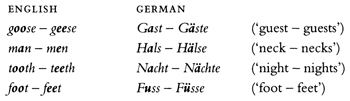

The clues so far have relied mostly on evidence from within the Semitic language family, but in order to understand how the a-mutation could have developed, the best clues actually come from parallels much closer to home. Are there any familiar languages which have a pattern similar to the a-mutation? The first example that springs to mind, of course, is those English verbs like sit-sat, drink-drank, or German ones like trinken-tranken. Unfortunately, however, the origin of the vowel mutation in the Germanic verbs is also pretty obscure, as it goes back to the deepest strata of Proto-Indo-European. But we shouldn’t give up on Germanic just yet, because there happens to be another pattern of vowel mutation in the Germanic languages, whose origin is more recent and thus better understood. Consider the following pairs:

At first, messing around with a bunch of badly behaved Germanic nouns may seem rather a detour from the quest for the origins of the Semitic verb. Nevertheless, I promise that wandering through the thickets of Germanic philology will soon bring us to where we want to be. For whether in Germanic or Semitic, whether in nouns or verbs, our goal is to understand how a vowel mutation with a grammatical function can emerge. And once we have worked out how one vowel mutation has come to mark one grammatical function in one family, it will become much easier to grasp how another vowel mutation could have come to mark a different grammatical function in another family.

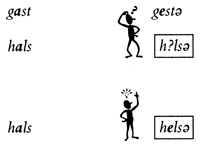

To see how the vowel mutation developed in the Germanic nouns, it is easier to start off with German rather than with English. Comparative evidence suggests that initially, there was nothing unusual about the noun gast (‘guest’), and that its plural was simply *gast-iz (-iz was a normal plural ending of Proto-Germanic). But at some stage before the earliest records of German in the eighth century AD, effort-saving mechanisms were set in motion and a few sound changes occurred. One was a type of assimilation (the ‘Santa Siesta’ principle from Chapter 3). In the word gastiz, there were two different vowels in close proximity, which required two very different configurations of the mouth. Moving the tongue quickly from a shape needed for an a {ah} to an i {ee} is really quite a bother, so to save effort, the first vowel a was ‘coloured’ by the i, and changed into something half-way between, namely to e {eh}. So gastiz became gestiz. Linguists call this process i-mutation, because the i caused the preceding vowel to change.

The final z of gestiz was also dropped at some stage, to give the plural form gesti, which is what we find in the first records of German in the eighth century. But the effort-saving spree did not come to an end right there. In the eleventh century, the final -i of gesti was weakened further to just a schwa, a reduced indistinct vowel (written ![]() in phonetic transcription) which can be heard in English words like elephant {el

in phonetic transcription) which can be heard in English words like elephant {el![]() f

f![]() nt} or ‘bother’ {both

nt} or ‘bother’ {both![]() }. And so gesti ended up as gest

}. And so gesti ended up as gest![]() , giving the pair gast-gest

, giving the pair gast-gest![]() . (In modern German orthography, gest

. (In modern German orthography, gest![]() is spelled Gäste, but for simplicity, a phonetic spelling will be used here instead.) In other words, after the ending iz messed things up by changing gastiz to gestiz, this ending itself fell victim to the forces of erosion and disappeared, leaving behind a mere schwa.

is spelled Gäste, but for simplicity, a phonetic spelling will be used here instead.) In other words, after the ending iz messed things up by changing gastiz to gestiz, this ending itself fell victim to the forces of erosion and disappeared, leaving behind a mere schwa.

So far, these two changes were entirely mechanical effort-saving devices. They had nothing to do with the meaning of the plural – in fact, they had nothing to do with any kind of meaning whatsoever. They were blind changes, influenced only by the phonetic environment. Nevertheless, the combination of these blind changes created the potential for a new meaningful pattern to emerge. The plural form gest![]() was stuck with an e in the middle (instead of the original a), but there was no longer anything to remind speakers of why this e had come to be there in the first place. The order-craving minds of a new generation of speakers could thus seize on the pattern gast-gest

was stuck with an e in the middle (instead of the original a), but there was no longer anything to remind speakers of why this e had come to be there in the first place. The order-craving minds of a new generation of speakers could thus seize on the pattern gast-gest![]() , and assume that the change of vowel from a to e must be there for some purpose, and that purpose must be to indicate plurality.

, and assume that the change of vowel from a to e must be there for some purpose, and that purpose must be to indicate plurality.

And once the mutation from a to e was perceived to be a meaningful pattern, speakers could also extend it by analogy to other nouns, even those which from a historical perspective were not likely candidates. For example, the noun hals (‘neck’) originally had a different plural ending -az, so its plural form was originally *halsaz, not halsiz – no reason for i-mutation there. If it were only down to effort-saving changes, then, the plural halsaz should have ended up as hals![]() . But the new generation of German speakers couldn’t give a sausage about the ‘historical perspective’, so on the analogy of nouns like gast-gest

. But the new generation of German speakers couldn’t give a sausage about the ‘historical perspective’, so on the analogy of nouns like gast-gest![]() , they coined the pair hals-hels

, they coined the pair hals-hels![]() :

:

Even newly borrowed nouns were subjected to this analogy. For example, the nouns kardinal and general entered German only in the thirteenth century, long after the original culprit for i-mutation (the ending -iz) had disappeared. But if the plural of gast is gest![]() , and the plural of hals has now come to be hels

, and the plural of hals has now come to be hels![]() , then what should be the plural of the newcomers kardinal and general, if not kardinel

, then what should be the plural of the newcomers kardinal and general, if not kardinel![]() , and generel

, and generel![]() ? (In modern orthography, these are spelled Kardinäle and Generäte.)

? (In modern orthography, these are spelled Kardinäle and Generäte.)

To summarize, then, what created the pattern of vowel mutation (a → e) as a marker of plurality was a cycle of erosion and analogy. A sequence of effort-saving changes created the conditions for the appearance of this pattern (first, the ending -iz coloured the previous vowel a to e, to give gestiz, and then this ending itself was eroded out of all recognition, to leave just gest![]() ). But it was not erosion on its own that turned these blind changes into a meaningful distinction. The grammatical function of the pattern was the brain-child of the order-craving mind.

). But it was not erosion on its own that turned these blind changes into a meaningful distinction. The grammatical function of the pattern was the brain-child of the order-craving mind.

In English, incidentally, the development initially ran along similar lines, except that it started a few centuries earlier than German. The noun man (originally mann) must have started with a regular plural form *mann-iz, but then the effects of the vowel i changed the preceding a to e, giving menn-iz. Later, the final -iz was reduced, and was then lopped off altogether, leaving our present plural men. From this point onwards, however, English and German took rather different courses. In English, the pattern of vowel mutation never really took off, and was not extended and regularized to other nouns. It might be tempting to conclude from the comparison that the English mind was not quite as order-craving as the German, but in actual fact, the real reason for the difference was more mundane. In English, the mutation pattern was overwhelmed by a much more common plural pattern: the ending -s. So the mutation persisted only in a few very common ‘exceptions’, like men, and a small bunch of other erratic nouns.

Now I promised earlier that the Germanic nouns will land us exactly where we want to be. And just as a reminder of where that is: our ultimate aim is to understand how the architecture of the Semitic verb, with its abstract design of purely consonantal roots and vowel templates, could ever have evolved of its own accord. The first clue revealed that the ancestor of the Semitic languages must have had a fairly ‘normal’ verbal system, with pronounceable stems like ktum, ptil or mūt which had both consonants and vowels. I then suggested that the whole imposing edifice of the Semitic verb may have arisen from rather modest beginnings: the emergence of just one vowel alteration, which I called a-mutation. The vowel u or i of the ancient stem changed to a in the future tense, thus giving rise to pairs like aktum-aktam ‘I covered-I will cover’, amūt-amāt ‘I died-I will die’, and so on. The reason why we then got involved with the Germanic nouns was to find out how such a mutation could have developed in the first place, and how it could have assumed a grammatical function (in the Semitic case, of a future tense).

By now, it should be clear that we have arrived exactly where we wanted to be. The a-mutation in Semitic verbs must have developed along similar lines to the i-mutation in Germanic nouns. Of course, the details would have been quite different. For one thing, the a-mutation in Semitic could never have arisen from an ending like -iz, for the simple reason that an i cannot colour the vowel u (of aktum) into an a (aktam). Nevertheless, the principle must have been just the same: a cycle of erosion and analogy. Some culprit or other must have caused the vowel to change in the future tense, and must later have vanished as a result of further effort-saving changes. Speakers then came to perceive the vowel alteration as a meaningful pattern, and so extended it by analogy to other verbs. So what had started off as a series of blind effort-saving changes assumed a grammatical role – marking the future tense.

We will never know exactly what the culprit looked like in the ancestor of the Semitic languages. The a-mutation is simply too old for that. Nevertheless, one educated guess would be that the culprit in question may not have been a vowel, but rather some consonants, none other, in fact, than the ‘laryngeals’ which we met in Chapter 3 in relation to Saussure’s celebrated hypothesis about the vowel system of Proto-Indo-European. In Indo-European, a laryngeal sound caused the vowel e in its vicinity to change to a, and then disappeared from the scene. In Semitic, laryngeal sounds are still around, and it may well be that they were responsible for the effort-saving change that kicked off the a-mutation. (Appendix B: Laryngeals Again? here suggests one scenario for how this might have happened.) But for now, since the general principles are clear, we can move on to find out how the idea of the consonantal root could have taken off from there.

CLUE 4: REVOLVING, REVOLUTIONS AND REVOLUTIONIZING

From what we have gathered so far, the first step towards the notion of a purely consonantal root may have been the rise of just one vowel mutation, which changed the vowel of the stem to a in the future tense. Of course, the pattern of one vowel mutation is still quite simple, but it is nevertheless a crucial cornerstone for the new concept of a purely consonantal root. The mutation inside the stem rocks the foundations of the old idea that the stem vowel is a permanent fixture, and presents this vowel not as an immutable constant, but rather as a variable whose alterations can mark a grammatical function. The vowel mutation acquaints speakers with an innovative scheme whereby a change of grammatical nuance may be marked not only by adding a prefix or a suffix to the verb, but also by changing the vowel inside it. Clearly, then, the a-mutation is a move in the right direction towards the notion of the purely consonantal root.

There are now just two more steps needed to bring us from this simple a-mutation to the design of the root-and-template system. The first of these is understanding how a verbal landscape dominated by roots with exactly three consonants could have arisen. There is no reason to assume that three-consonant roots had always held sway in Semitic. In fact, as we have seen, there still are verbs with only two consonants around even in the historical era: those hollow verbs like mūt and ![]() ī

ī![]() . Of course, by the time we can start observing them, these hollow verbs have become just a small minority of exceptions, but there are grounds for suspecting that in prehistoric times, there were more of these hollow verbs around. (There is no need to go into all the reasons here, except for mentioning that they are based on both internal considerations and on parallels from other Afro-Asiatic languages, which have more verbs with two consonants than with three.) So we cannot take it for granted that three-consonant verbs were the rule from the very beginning. And we first need to explain how three-consonant verbs could have come to dominate the verbal scene in the ancestor of the Semitic languages.

. Of course, by the time we can start observing them, these hollow verbs have become just a small minority of exceptions, but there are grounds for suspecting that in prehistoric times, there were more of these hollow verbs around. (There is no need to go into all the reasons here, except for mentioning that they are based on both internal considerations and on parallels from other Afro-Asiatic languages, which have more verbs with two consonants than with three.) So we cannot take it for granted that three-consonant verbs were the rule from the very beginning. And we first need to explain how three-consonant verbs could have come to dominate the verbal scene in the ancestor of the Semitic languages.

But why does it matter whether or not the verbal system is dominated by three-consonant verbs? The reason is simply that the mature Semitic templates all require a full set of three consonants to function properly. Whereas the ancient a-mutation is unaffected by how many consonants there are in the root (it works equally well with two, amūt-amāt, or with three, aptil-aptal), all the elaborate templates of the mature system have precisely three slots for the three consonants. Roots with only two consonants simply cannot fit into templates like ![]() , as there just aren’t enough consonants to go around. It seems unlikely, therefore, that these templates could ever have developed in the ancestor of the Semitic languages, before the verbal landscape came to be dominated by roots with three consonants.

, as there just aren’t enough consonants to go around. It seems unlikely, therefore, that these templates could ever have developed in the ancestor of the Semitic languages, before the verbal landscape came to be dominated by roots with three consonants.

So how could three-consonant verbs succeed in taking over the system, if there were originally at least as many verbs with two consonants as with three? Once again, parallels from more familiar languages can set us on the right track. One method by which longer verbs can enter the language is through the ‘swelling’ of older shorter verbs, a phenomenon which can be seen even in English today. Look at how the verbs below start out lean and fit on the left, but then put on more and more weight as they move rightwards:

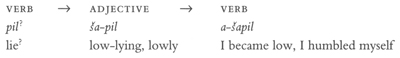

What is going on here is a sort of cycle, from verb to noun and then back to verb again. An ending is used to turn a verb into a noun, and then another ending can turn this noun back into a verb, by which time the word has swollen with endings. Similar cycles can be seen in the Semitic languages, but there, the swelling tends to come from prefixes instead. And there are good reasons to think that many such cycles also took place in prehistoric times, so that verbs which started out with only two consonants swelled to three. One such cycle may have looked something like this:

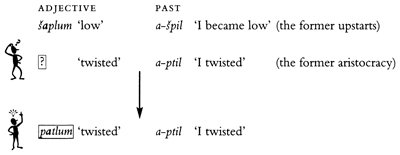

Let’s assume that a prehistoric verb such as pil, perhaps meaning ‘lie’, was turned with the aid of a prefix ša- into an adjective šapil, meaning ‘lowlying’, and then the adjective was itself converted into a new verb a-šapil, ‘I became low’. (Incidentally, in real life, adjectives in Semitic generally appear with case endings, so the adjective šapil would actually look something like šapil-um. We needn’t bother with this case ending just for the moment, but it should not be forgotten altogether, since it will become relevant later.)

Of course, this is not the only way that new swollen verbs could have entered the language, but there is no need to get swamped by the details. What really matters for us is only that three-consonant verbs could have increased and multiplied with time, while some of the older hollow verbs gradually sank into oblivion, as old words often do. And so at some stage the sheer numbers tipped over the balance, and three-consonant verbs began to dominate the scene. They came to be perceived as the norm, while the old hollow verbs remained only as exceptions.*

CLUE 5: ON SYNCOPE AND THE LIBERATION OF CONSONANTS

We have already gained significant ground in our foray on the stronghold of the Semitic verb. Behind us is the knowledge of how one vowel mutation could have assumed the grammatical function of marking the future tense, and how a landscape dominated by three-consonant verbs could have developed. And yet, although we have now reached the final stage, the architecture of the Semitic verb still seems alarmingly distant. In particular, our one simple vowel mutation is still a long way from the mature system with its multitude of templates and nuances.

Nevertheless, we are much closer than may first appear, at least to the fundamental design of the Semitic verb, the purely consonantal root. We are in fact just a stone’s throw away, for in order to understand how the idea of the consonantal root was conceived, we don’t really need all those dozens of fancy templates like ‘I will cause to snog’ (![]() ) or ‘she keeps on snogging intensely’ (

) or ‘she keeps on snogging intensely’ (![]() ). To capture the essence of the root-and-template system, all that is required are a handful of the simplest templates, like the three below:

). To capture the essence of the root-and-template system, all that is required are a handful of the simplest templates, like the three below:

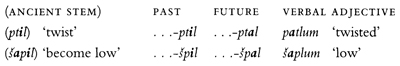

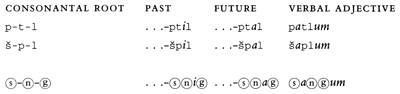

I suggest that if we can explain how just these three templates arose, the notion of a purely consonantal root will fall out for free. And there is even better news in store, since the first two templates have already been derived. We have hypothesized that some cycles of erosion and analogy must have created the a-mutation as a marker of the future tense, and that this a-mutation originally applied not only to the hollow verbs, but to three-consonantal verbs as well, producing pairs like aptil (‘I twisted’) and aptal (‘I will twist’). But the templates ![]() and

and ![]() are really just a different way of showing exactly the same pattern of a-mutation more generally. So in fact, we are now really only one template away from the target. If we can only manage to explain the origin of the third template above, the verbal adjective

are really just a different way of showing exactly the same pattern of a-mutation more generally. So in fact, we are now really only one template away from the target. If we can only manage to explain the origin of the third template above, the verbal adjective ![]() then the consonantal root will be within spitting distance.

then the consonantal root will be within spitting distance.

But what is so special about ![]() anyway, and what makes it so different from

anyway, and what makes it so different from ![]() or

or ![]() ? The real novelty about

? The real novelty about ![]() is the vowel a between its first two consonants. The verbal adjective deviates from the pair

is the vowel a between its first two consonants. The verbal adjective deviates from the pair ![]() and

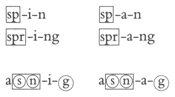

and ![]() because in these the first two consonants behave as an inseparable cluster, much like in the English verbs spin, drink or spring:

because in these the first two consonants behave as an inseparable cluster, much like in the English verbs spin, drink or spring:

The English verbs have three (or even more) consonants, but these always stick together in two groups. The vowel between the clusters may change, to give forms like spin, span or even spun, but one never gets forms like sapin, supun or sapnum. In ![]() however, a vowel has somehow slipped into the first cluster, so that its two consonants have been ‘liberated’ from each other. What remains to be explained, then, is how the vowel a could have made its way into the cluster

however, a vowel has somehow slipped into the first cluster, so that its two consonants have been ‘liberated’ from each other. What remains to be explained, then, is how the vowel a could have made its way into the cluster ![]() of

of ![]()

What type of process could inject a vowel into a cluster of consonants? Of course, it would be much easier to understand a change in the other direction, and explain how a vowel was dropped from between two consonants – after all, erosion can do that sort of thing blindfolded before breakfast. But the opposite is a different matter, as it is far less easy to find a process that can take a vowel, insert it between two consonants, and even lend it a grammatical function. The only thing that can pull off that type of change is – once again – a cycle of erosion and analogy, the interplay of blind changes with the mind’s craving for order.

The effort-saving change that was needed to start this cycle was actually quite straightforward. It is what linguists call ‘syncope’: the dropping of a vowel in the middle of a word. The effects of syncope are evident in English words like ever-every or radical-radically. The orthography may still represent the vowels in the second element of the pairs, but spoken language has long since dropped them, and they are simply pronounced {evry} and {radicly}. When there are too many short vowels in a row, there is just a great temptation to dispense with one of them.

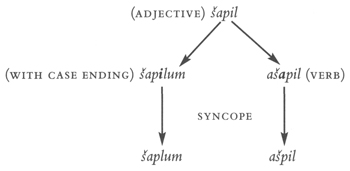

To see what syncope can get up to in our case, let’s go back to where we left off with the prehistoric ancestor of the Semitic languages. There are now two kinds of three-consonant verbs around. On the one hand there are those old verbs, scions like a-ptil (‘I twisted’), which always had three consonants. But on the other hand there are those newly swollen upstarts like a-šapil (‘I became lowly’), which acquired their third consonant only more recently, from the prefix ša-. Now imagine that syncope is unleashed on the language, and that it eliminates the middle vowel whenever there are three short vowels in a row. (This kind of syncope has actually occurred very often in the history of Semitic.) What effects does the syncope have on the two classes of stems? The old class of verbs remains unaffected, since a-ptil only has two vowels. But for the upstarts, the situation looks rather different: a-šapil has three short vowels in a row, and is thus a candidate for syncope. So the middle vowel is dropped, to give just ašpil.

What’s more, the syncope doesn’t even stop there. We saw that a-šapil was born from an adjective šapil ‘low’. But as I mentioned earlier on, in real life the adjectives take case endings such as -um, and together with the case ending, the adjective šapil-um is itself a candidate for syncope, because it has three short vowels in a row. So the middle vowel is dropped, to give šaplum. The effects of syncope on the adjective and the verb that emerged from it are summarized in the diagram:

So far, this was simply a blind effort-saving spree, an instance of syncope that eliminated the middle vowel from a series of three vowels in a row. But now it’s the turn of the order-craving mind. The system that new generations of speakers are faced with is quite different from the earlier stratified society, because the syncope has levelled out some of the old ‘class distinctions’. For the upwardly-mobile verb a-špil, the change has really been quite a boon. Once syncope has removed from a-šapil the give-away vowel of the original prefix ša, the verb a-špil has become almost indistinguishable from the older verbs, scions such as a-ptil. So once the syncope has been and gone, and after any memory of the earlier distinctions has all but faded, the former upstarts display a peculiar pattern: the adjective from which they were derived retains the giveaway a, but in the past tense, this a has been forgotten. So the following pattern comes to be established in speakers’ minds:

![]()

We, as linguists, may recognize that this pattern is the result of an intricate series of historical developments. We know that the vowel a in the adjective šaplum originally came from a prefix ša-, and that blind syncope did away with this a in the past tense of the upstarts. But the new generation of speakers have no idea about any of this. They simply discern a pattern where an adjective has a vowel a between the first two consonants whereas the past tense does not have it. And once speakers recognize this pattern, what could be more natural than to try to extend it to other verbs?

And so the scene is set for back formation. The new generations have no idea about the old distinctions of the past. They don’t know that from a historical perspective, this pattern (ADJECTIVE: ![]() →PAST TENSE:

→PAST TENSE: ![]() ) should apply only to those upwardly-mobile verbs that had sprung from adjectives. The new speakers simply extend the pattern (in reverse) to anything else that seems to fit: if the adjective corresponding to ašpil is šaplum, then what should be the adjective corresponding to a-ptil? It must be patlum, of course.

) should apply only to those upwardly-mobile verbs that had sprung from adjectives. The new speakers simply extend the pattern (in reverse) to anything else that seems to fit: if the adjective corresponding to ašpil is šaplum, then what should be the adjective corresponding to a-ptil? It must be patlum, of course.

The back formation that created patlum does not seem anything out of the ordinary. But in extending and regularizing the pattern, speakers have introduced two major innovations. First, they have created a Verbal adjective’ – an adjective derived from a verb, rather than vice versa. And second, the speakers have liberated the two initial consonants of the old class of three-consonantal verbs, and inserted an a in between the two consonants of the initial cluster pt of ptil What is more, this new vowel is not there simply for decoration – it has a meaningful grammatical purpose, to mark the verbal adjective. And so, all three consonants have achieved independence.

We are nearly there. At the stage we have arrived at (still somewhere in prehistory), there are now three different forms for each verb, as shown below. (The three dots in the past and future tenses stand for the person markers, the prefixes a- ‘I’, ni- ‘we’, and so on.)

The only thing still missing is the idea of the purely consonantal root. But in fact, this idea is already inherent in the system we have reached. In the table above, I still included the ancient stem with its original vowels, but in some sense, this is already an anachronism. For when one examines the three different forms of the verb that are now in use (past, future and verbal adjective), it transpires that the only thing left in common to all three are the consonants. None of the stem’s original vowels appears in all three forms any longer. The vowel i of ptil and šapil has only survived in the past tense, and the vowel a between the first two consonants of the former upstart šapil has only survived in the verbal adjective.

Now the bare stem never crops up in speech on its own – the forms that speakers actually use are the past, the future, and the verbal adjective. Since new generations of speakers can no longer even recognize the stem from the verbal forms they do use, and since they can no longer discern the vowels of the original stem as a common denominator, all that has remained in their perception as a uniting factor between the different verbal forms are the three consonants. For new speakers faced with this set-up, what bears the core sense ‘twist’ is no longer a pronounceable chunk ptil, but only the three consonants p-t-1. And at this point, it really makes sense to start talking about ‘consonantal roots’ such as p-t-1 or š-p-1. So it would actually be more appropriate to present the table above in a different way, with consonantal roots and vowel templates:

So we have finally extracted the essence of the Semitic verbal system! The system we have now arrived at is still quite simple, and does not fully correspond to the situation in the attested period in Akkadian (when the future tense of regular verbs was formed by the more complex template ![]() ). But what we do have now is the notion of a purely consonantal root and the basis for the vowel templates. The root-and-template design is really just a way of representing the pattern which has now emerged, whereby the vowels are determined by the grammatical nuance, and not by the whim of the stem. The three verbal forms we have derived are thus sufficient to kindle in speakers’ perception the idea behind the root-and-template system. They show that the notion of a purely consonantal root need not have been sparked by any celestial flash of inspiration. All that was required to create this remarkable design was a fairly down-to-earth, albeit rather uncommon set-up: the emergence of a few verbal nuances which all share the same consonants, but no longer share any vowels. The vowels of the original stem must have lost their place in speakers’ perception as a distinguishing feature for the core meaning of the verb (such as ‘twist’ or ‘die’), and so they came to be viewed only as marking the grammatical nuance (past, future, and soon). And thus the idea of a purely consonantal root was born.

). But what we do have now is the notion of a purely consonantal root and the basis for the vowel templates. The root-and-template design is really just a way of representing the pattern which has now emerged, whereby the vowels are determined by the grammatical nuance, and not by the whim of the stem. The three verbal forms we have derived are thus sufficient to kindle in speakers’ perception the idea behind the root-and-template system. They show that the notion of a purely consonantal root need not have been sparked by any celestial flash of inspiration. All that was required to create this remarkable design was a fairly down-to-earth, albeit rather uncommon set-up: the emergence of a few verbal nuances which all share the same consonants, but no longer share any vowels. The vowels of the original stem must have lost their place in speakers’ perception as a distinguishing feature for the core meaning of the verb (such as ‘twist’ or ‘die’), and so they came to be viewed only as marking the grammatical nuance (past, future, and soon). And thus the idea of a purely consonantal root was born.

* * *

I want to know God’s thoughts.

The rest are details …

(Albert Einstein)