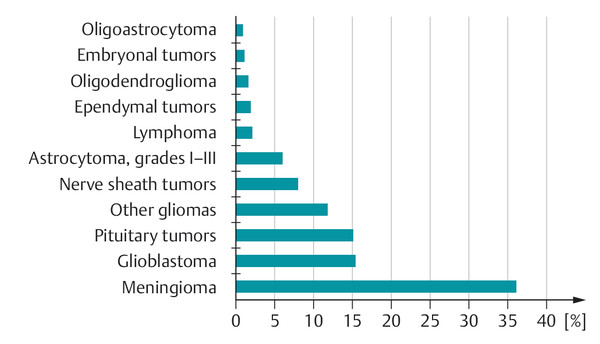

Fig. 6.13 The frequency of tumors of the brain and meninges. (Data from www.cbtrus.org.)

Key Point

Brain tumors are one of the more common causes of intracranial hypertension. They are subdivided into primary brain tumors, which arise from the brain tissue itself (either the neuroepithelial tissue or the neighboring mesenchymal tissues, e.g., the meninges), brain metastases, and tumors arising from the cells of the blood vessels. Brain tumors produce focal brain signs of different types depending on their location, as well as signs of intracranial hypertension that may progress more or less rapidly depending on the rate of tumor growth.

Epidemiology The incidence of tumors of the brain or spinal cord is approximately 5 per 100,000 persons per year in children and adolescents, and 28 per 100,000 persons per year in adults. Brain and spinal cord tumors are the most common kind of solid tumor in children; in adults, they are much rarer than the most common kinds of cancer (prostate, breast).

The frequency of different kinds of brain and meningeal tumors is shown in ▶ Fig. 6.13. The spectrum of brain tumors changes with age. In children and adolescents, the most common tumors are pilocytic astrocytoma, glioma, and medulloblastoma; in adults, the most common tumors are meningioma, glioblastoma, and pituitary tumors. Among the elderly, meningioma and glioblastoma are most common.

Note

Meningioma, schwannoma, and pituitary tumors are among the most common benign tumors; glioblastoma and astrocytoma are among the most common malignant tumors.

Classification and grading In the WHO classification, brain tumors are classified by their histologic type (for a simplified overview, see ▶ Table 6.10) and by their degree of malignity, ranked on a four-point scale ( ▶ Table 6.11): tumors of WHO grades I and II are benign, while those of grades III and IV are malignant.

|

WHO tumor type |

Examples |

|

Neuroepithelial tumors |

Astrocytoma, glioblastoma |

|

Oligodendroglioma |

|

|

Mixed glioma |

|

|

Ependymoma |

|

|

Choroid plexus papilloma |

|

|

Gangliocytoma |

|

|

Pinealocytoma |

|

|

Medulloblastoma |

|

|

Peripheral nerve tumors |

Schwannoma (= neurinoma) |

|

Neurofibroma |

|

|

Meningeal tumors |

Meningioma |

|

Hemangioblastoma |

|

|

Neoplasias of the hematopoietic system |

Primary CNS lymphoma |

|

Malignant lymphoma |

|

|

Germ-cell tumors |

Germinoma |

|

Teratoma |

|

|

Tumors of the sellar region |

Pituitary adenoma |

|

Craniopharyngioma |

|

|

Metastases |

Carcinomas of the:

|

|

Abbreviation: CNS, central nervous system. |

|

|

Grade |

Features |

MRI |

Representative examples |

|

I |

Slowly growing, not malignant, cells appear nearly normal, long survival |

T2-hyperintense, hardly any mass effect, no enhancement |

Pilocytic astrocytoma |

|

II |

Relatively slowly growing, occasional atypical cells, can transform into higher-grade tumors or recur as higher-grade tumors after treatment |

T2-hyperintense, mass effect, no enhancement |

Astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma |

|

III |

Malignant, with anaplastic cells; recur as high-grade tumors |

T2-hyperintense, mass effect, variable enhancement (from none to highly complex) |

Anaplastic astrocytoma |

|

IV |

Malignant, with anaplastic cells; rapid, aggressive growth |

T2-hyperintense, mass effect, ring-shaped enhancement |

Glioblastoma |

|

Source: From Mattle H, Mumenthaler M. Neurologie. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2013. |

|||

Fig. 6.13 The frequency of tumors of the brain and meninges. (Data from www.cbtrus.org.)

Etiology Most brain tumors are of no known cause; in rare cases, they can be caused by a prior exposure to ionizing radiation or by a genetic syndrome. Examples include Li–Fraumeni syndrome (astrocytoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumors [PNET], sarcoma), Turcot syndrome (medulloblastoma, glioblastoma), and the phakomatoses (see section ▶ 6.1.8):

Neurofibromatosis, type 1 (neurofibroma, iris hamartoma) and type 2 (meningioma, bilateral acoustic neuroma, retinal hamartoma).

von Hippel–Lindau disease (hemangioblastoma of the cerebellum).

Tuberous sclerosis (cortical hamartoma, giant-cell astrocytoma).

Encephalofacial angiomatosis, that is, Sturge–Weber disease.

General clinical manifestations The general manifestations of brain tumors are presented in ▶ Table 6.12. These can progress more or less rapidly depending on the type and growth rate of the tumor. Malignant tumors typically manifest a “crescendo” course, in which overt signs and symptoms arise soon after the onset of the illness, and then worsen steadily and rapidly. The signs and symptoms of benign tumors, on the other hand, often progress slowly and insidiously, perhaps over many years. Hemorrhage into a brain tumor (either benign or malignant) may cause symptoms to arise very suddenly.

|

Symptoms |

Signs |

|

|

Diagnostic evaluation Neuroimaging studies are essential: the best is generally contrast-enhanced MRI (cf. ▶ Table 4.2). CT may provide useful complementary information in some cases, for example, calcifications or accompanying osseous changes, but may fail to reveal some tumors (especially low-grade gliomas). Sometimes angiography is indicated for visualization of a tumor’s blood supply.

Brain tumors generally cannot be securely diagnosed by imaging studies alone; in most cases, at least some of the tumor must be surgically removed for histologic examination. If total resection is not possible because of the location of the tumor, or contraindicated for other medical reasons, then tissue can be obtained by a stereotactic brain biopsy. A secure histologic diagnosis is needed for the optimal planning of further treatment, such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Moreover, some “brain tumors” turn out, on biopsy, not to be tumors at all, but rather brain abscesses, foci of demyelination, etc. In such cases, diagnostic biopsies save the patient from needless and probably harmful treatment.

Practical Tip

CSF examination is generally neither necessary nor helpful in the evaluation of brain tumors. CSF cytology is clinically useful only in case of meningeal spread (e.g., in carcinomatous meningitis) and when the presence of oligoclonal bands in the CSF helps to establish the correct diagnosis of a large multiple sclerosis plaque that resembles a brain tumor on imaging studies.

Tumor markers may be useful for diagnosis and treatment.

Additional Information

Mass lesions of the CNS that may be misdiagnosed as tumors include:

Residual mass lesions after episodes of ischemia, inflammation, or thrombosis.

Infections (bacterial abscess, tuberculosis, fungal or parasitic infection).

Multiple sclerosis plaques (mainly of the “tumefactive” type).

Sarcoidosis.

Treatment Complete resection of the tumor is indicated whenever possible. The operability of brain tumors depends on their size, location, histologic grade, and relation to the surrounding brain tissue (infiltration vs. displacement). Not every tumor is neurosurgically accessible or fully resectable. Depending on the type of tumor, radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy may have to be used, either as the primary form of treatment or as adjuvant therapy after surgery.

The cerebral edema that usually accompanies malignant tumors is treated with corticosteroids (usually dexamethasone). Dexamethasone is also given preoperatively to reduce swelling in all cases of brain tumor with mass effect and elevated ICP. Epileptic seizures, if they arise, are treated with anticonvulsants, for example, levetiracetam. In some circumstances, prophylactic anticonvulsant administration may be helpful as well.

Practical Tip

Epileptic seizures are an important manifestation of brain tumors and can arise either before or after neurosurgical resection.

Note

Astrocytoma is the most common type of primary brain tumor and is classed as a neuroepithelial tumor. Grade III and IV astrocytomas are called anaplastic astrocytoma and glioblastoma, respectively; these forms are highly malignant and lead rapidly to death. Grade I and II astrocytomas are more benign, growing slowly and progressively over a period of years. Pilocytic astrocytoma (grade I), a tumor seen mostly in children and adolescents, is the only type of astrocytoma that generally does not recur after total resection.

A distinction is drawn between primary and secondary glioblastoma. Primary glioblastoma is already a grade IV tumor at the time it arises (or is first discovered); secondary glioblastoma develops by malignant progression from a preexisting lower-grade astrocytoma or other type of glioma. Glioblastoma was historically called “glioblastoma multiforme;” the second word adds no information and has been dropped from modern classifications.

Epidemiology Glioblastoma is the most common and most malignant type of primary brain tumor. It grows by infiltration into the brain tissue. Its highest incidence is in the fifth and sixth decades of life.

Localization and growth Glioblastoma arises in a cerebral hemisphere and can spread to the contralateral hemisphere by way of the corpus callosum (butterfly glioma). Glioblastomas grow rapidly, causing rapidly progressive clinical manifestations; they are, therefore, usually diagnosed within a few weeks or (at most) months of the onset of symptoms.

Clinical features Focal neurologic and/or neuropsychological deficits arise first, sometimes accompanied by epileptic seizures, soon followed by general signs of intracranial hypertension (see ▶ Table 6.9).

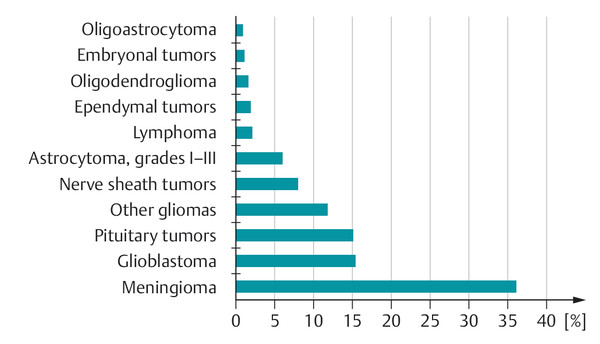

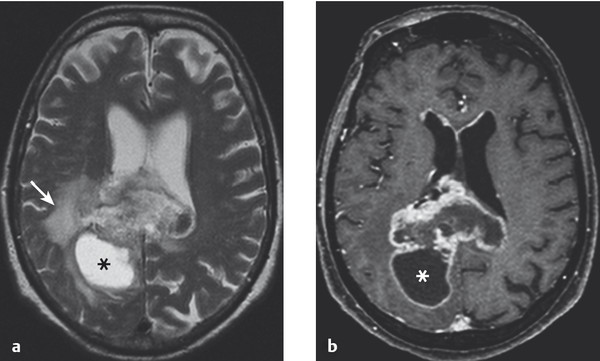

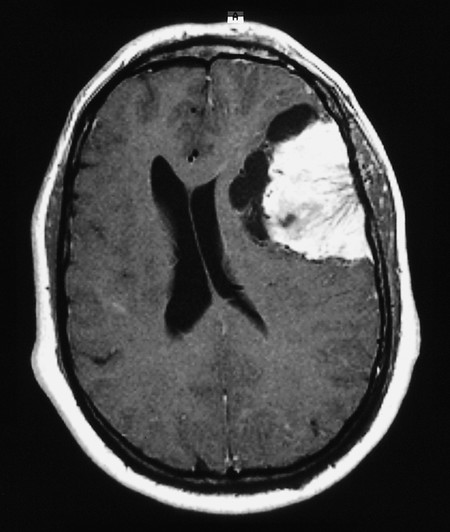

Diagnostic evaluation The diagnosis can be made fairly securely from the typical appearance in neuroimaging studies ( ▶ Fig. 6.14, ▶ Fig. 6.15), though this does not obviate the need for histologic examination of tumor tissue. Contrast-enhanced MRI or CT characteristically reveals ringlike enhancement with a central nonenhancing area, corresponding to necrosis in the interior of the tumor. Intratumoral hemorrhages may also be seen. Peritumoral brain edema is often extensive, causing mass effect and midline shift.

Fig. 6.14 Glioblastoma. The T2-weighted (a) and T1-weighted (b) MR images reveal a butterfly-shaped tumor in the splenium of the corpus callosum and adjacent regions of the two cerebral hemispheres. A cyst (*) in the right occipital lobe is part of the tumor; like the rest of the tumor, the cyst wall displays contrast enhancement (b). Peritumoral edema is most marked in the right hemisphere (→) (a).

Fig. 6.15 Grade II–III astrocytoma. The tumor is hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI (a) and hypointense on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI (b). Its left frontal portion takes up contrast medium (→), probably because of malignant progression here to a grade III tumor.

Prognosis The survival of patients who have undergone the partial or gross total resection of a glioblastoma, with or without adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, is measured in months to a few years at most.

Grade III astrocytoma occupies an intermediate position between grade II astrocytoma and glioblastoma with respect to malignant behavior.

Additional Information

Gliomatosis cerebri, defined as a glial tumor that grows diffusely into three or more lobes of the brain, is included in the category of grade III astrocytoma. It is inoperable and responds poorly to radiotherapy as well.

Epidemiology Astrocytomas of the cerebral hemisphere(s) generally affect adults aged 30 to 40 years.

Growth Though these tumors displace and infiltrate the surrounding brain tissue, they are better demarcated from it than glioblastoma; they often grow quite slowly, sometimes over many years.

Clinical features These include focal or secondarily generalized epileptic seizures, often as the presenting manifestation, as well as behavioral and neuropsychological changes, increasingly severe focal neurologic deficits (e.g., hemiparesis), and signs of intracranial hypertension.

Treatment and prognosis If epileptic seizures are the only manifestation, tumor resection may be useful for seizure control, if the location of the tumor permits. Totally resected tumors sometimes do not recur until years later.

Epidemiology This form of tumor usually arises in children and adolescents.

Localization and growth Pilocytic astrocytoma is usually found in the cerebellar hemispheres or vermis and may extend into the pons. It grows slowly and is benign.

Clinical features The symptoms and signs depend on the site of the tumor; thus, cerebellar manifestations are common.

Diagnostic evaluation These tumors generally display contrast enhancement (and are the only nonmalignant type of brain tumor to do so).

Treatment and prognosis Total resection often results in cure. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are a treatment of second choice if radical surgery would endanger important structures.

Brainstem astrocytoma, even if benign, is generally inoperable and incurable, though its symptoms and signs may improve with radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Epidemiology and growth Ependymoma is a benign tumor usually seen in children and adolescents. It grows by expansion and displacement of brain tissue. It can be partly calcified and cystic.

Localization Ependymomas develop from the neuroepithelium of the walls of the cerebral ventricles and the central canal of the spinal cord. They usually arise in the posterior fossa, most commonly near the fourth ventricle, and in the conus medullaris of the spinal cord (see ▶ Fig. 7.8).

Clinical features Their main clinical manifestations are focal (often cerebellar) neurologic deficits and signs of intracranial hypertension resulting from compression of the CSF pathways and occlusive hydrocephalus. An unusually persistent, continuous headache in a child should arouse suspicion of an ependymoma or other mass in the posterior fossa.

Treatment and prognosis The treatment is resection followed by radiotherapy of the entire neuraxis. Seventy percent of treated patients survive for 10 years or longer.

Epidemiology Medulloblastoma mainly affects children (in three-quarters of cases). PNET, a rare type of tumor, is more common in children as well.

Localization and growth These are undifferentiated, highly malignant tumors (WHO grade IV) characterized by rapid growth and rapidly progressive clinical manifestations. Medulloblastomas usually arise from the roof of the fourth ventricle, sometimes filling the entire ventricle, and grow into the inferior portion of the vermis. They grow by infiltration and often metastasize via the CSF into the spinal canal (drop metastases). PNET is mostly supratentorial.

Clinical features The signs and symptoms resemble those of cerebellar astrocytoma (headache, nausea, truncal ataxia), possibly combined with manifestations referable to the spinal cord and cauda equina.

Treatment and prognosis Medulloblastoma is treated by resection followed by radiotherapy (of the entire neuraxis, because of drop metastases) and/or chemotherapy. The prognosis after radical removal is not unfavorable (cure in 50% of cases), but often no more than an incomplete removal can be achieved, in which case tumor recurrence is the rule. PNET carries a worse prognosis than medulloblastoma.

Epidemiology Oligodendroglioma tends to arise between the ages of 40 and 50 years.

Localization and growth It is almost always found in the cerebral hemispheres, particularly the frontal lobes, and is usually a relatively well-differentiated tumor that grows slowly over the years and often becomes calcified.

Clinical features Oligodendroglioma often presents with epileptic seizures; recurrent seizures affect 70% of patients.

Treatment Oligodendroglioma is mostly radioresistant and is best treated by radical resection. If this can be achieved, radiotherapy is usually not given. Nonetheless, apparently radical resection can be followed by tumor recurrence, which may not take place until years after surgery.

Practical Tip

Gliomas of the optic nerve and chiasm arise almost exclusively in children, often as a component of neurofibromatosis.

|

Site |

Most common initial manifestations |

Course |

Special features |

|

Olfactory groove |

Anosmia |

Epileptic seizures, headache, frontal-type personality change, possible involvement of optic nerve |

|

|

Convexity |

Epileptic seizures |

Hemiparesis |

|

|

Parasagittal and falx |

Lower limb paresis, (sometimes) bilateral Babinski sign |

Epileptic seizures |

Rarely, paraparesis |

|

Sphenoid wing |

Loss of visual acuity, visual field defects (when medially located, adjacent to optic nerve); oculomotor disturbances |

Exophthalmos, hemiparesis |

Lateral tumors may be externally evident as temporal hyperostosis |

|

Tuberculum sellae |

Visual disturbances, pale optic discs |

Progressive visual field defect |

|

|

Cerebellopontine angle |

Deafness, vertigo |

Facial and trigeminal nerve deficits, brainstem compression |

Differential diagnosis: acoustic neuroma |

|

Foramen magnum |

Spastic quadriparesis, dysphagia, dysarthria |

Lower cranial nerve deficits |

|

|

Intraventricular |

Intermittent headaches and vomiting |

Progressive hydrocephalus |

Often found in trigone |

|

Intraspinal |

Progressive para- or quadriparesis |

Paraplegia or quadriplegia |

Epidemiology and etiology Meningiomas most often become clinically evident between the ages of 40 and 50 years. They arise sporadically in most cases, but there is a genetic predisposition toward meningioma formation in some tumor syndromes (phakomatoses), above all type II neurofibromatosis ( ▶ Table 6.4). Radiation exposure in early life also predisposes to meningioma formation.

Localization and growth These mesodermal tumors arise from the arachnoid and are nearly always benign, well-demarcated lesions that displace rather than invade the adjacent neural tissue as they slowly grow. Histologic examination often reveals a layered architecture resembling an onion. Meningiomas tend to appear in certain classic locations with corresponding typical neurologic manifestations, as listed in ▶ Table 6.13.

Morphologic classification and WHO grading The WHO grading of meningiomas depends on their gross and microscopic structure:

WHO grade I (benign, including most meningiomas): meningotheliomatous, transitional, microcytic, secretory, fibromatous, psammomatous, and angiomatous meningiomas.

WHO grade II (atypical, rapidly growing, with frequent recurrences): chordoid and clear-cell meningiomas.

WHO grade III (malignant, anaplastic, infiltrative): papillary and rhabdoid meningiomas.

Clinical features Meningiomas present with epileptic seizures, focal neurologic deficits (see ▶ Fig. 4.24), or, in rare cases, signs of intracranial hypertension (usually when the tumor lies far away from “eloquent” structures, e.g., in the right frontal lobe). The neurologic deficits may evolve slowly over many years. Meningioma is also a common incidental finding.

Diagnostic evaluation Meningiomas are diagnosed by MRI or CT scanning (see ▶ Fig. 4.24, ▶ Fig. 6.16). These reveal marked, homogeneous contrast enhancement.

Fig. 6.16 Meningioma of the left cerebral convexity (contrast-enhanced MRI). Marked mass effect deforms the ventricles and shifts the midline structures rightward. There are cystic cavities at the tumor–brain interface. Blood vessels supplying the tumor are seen entering it from its “navel” on the outer surface.

Treatment The indications for treatment must then be carefully considered: resection may be desirable in younger patients, but unnecessary in older ones. The need for resection also depends on the localization and growth rate of the tumor. Heavily calcified meningiomas grow very slowly or not at all. Radiotherapy is reasonable only for residual tumor after incomplete resection.

Epidemiology Lymphoma is typically seen in young, immunocompromized (e.g., HIV-infected) patients aged 40 to 60 years but can also affect immunocompetent elderly persons.

Localization and growth Lymphoma may arise secondarily as a metastasis of a lymphoma elsewhere in the body or primarily at one or more sites in the CNS. Primary CNS lymphoma is a rare B-cell variant of non–Hodgkin’s lymphoma and remains restricted to the CNS. These tumors grow rapidly.

Clinical features CNS lymphoma presents with signs of intracranial hypertension, epileptic seizures, and focal neurologic and neuropsychological deficits. The cranial nerves and the eyes are often affected as well.

Diagnostic evaluation CT and MRI generally show CNS lymphoma as a contrast-enhancing tumor near the ventricular wall.

Treatment CNS lymphoma is treated with corticosteroids, chemo- and immunotherapy (methotrexate and rituximab), and radiotherapy.

Note

Primary CNS lymphoma in immunosuppressed persons is usually associated with the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV).

Pituitary tumors usually arise from the cells of the anterior pituitary lobe. Depending on their origin, they can produce hormones in excess or cause hormone deficiency. Thus, they present clinically with endocrine disturbances and/or compressive effects on the adjacent neural tissue.

Hormone-secreting pituitary tumors These most commonly present between the ages of 30 and 50 years. Their presentation depends on the endocrine function of the cells from which they arise:

Basophil adenomas produce excessive adrenocorticotropic hormone, causing Cushing syndrome (which, when caused by a pituitary tumor, is called Cushing disease).

Prolactinomas cause galactorrhea and secondary amenorrhea in women and impotence in men.

The rare eosinophil adenomas produce excessive growth hormone, causing acromegaly. They can also grow large enough to cause other symptoms by mass effect.

Note

Although basophil adenomas and prolactinomas rarely cause mass effect, eosinophil adenomas and, above all, the hormonally inactive chromophobe adenomas can grow quite large, causing compression and dysfunction of the normal pituitary tissue, clinically evident as hypopituitarism (multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies, including hypothyroidism and secondary hypogonadism).

Non–hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas Inactive pituitary tumors are generally diagnosed only when they grow large enough to compress and functionally impair the neighboring structures. Headache can be a nonspecific symptom. They grow upward from the sella turcica and can compress the optic chiasm and cause visual field defects, usually bitemporal upper quadrantanopsia or bitemporal hemianopsia due to compression of the decussating optic nerve fibers (see section ▶ 12.2.1 and ▶ Fig. 12.1). If the nondecussating fibers are compressed as well, visual acuity may be impaired.

Treatment and prognosis These tumors are removed microsurgically, by the transnasal-transsphenoidal route if they are not too large and otherwise through a frontolateral craniotomy. Residual and recurrent tumors are irradiated. Resection can often reverse visual impairment, as long as it is not complete or longstanding. Prolactinomas can often be treated pharmacologically with dopaminergic inhibitors of prolactin secretion, for example, cabergoline. All pituitary tumors require lifelong follow-up, even after initially successful treatment. Hormone substitution may be needed as well (with hydrocortisone, L-thyroxine, antidiuretic hormone, testosterone, estrogen, or combinations of these hormones).

These include craniopharyngioma, dermoid and epidermoid tumors, and cavernoma.

Epidemiology Craniopharyngioma is the most common suprasellar mass in children and adolescents.

Localization and growth These tumors arise in or above the pituitary fossa, often growing upward toward the diencephalon and third ventricle. They are derived from epithelial remnants in Rathke’s pouch and generally contain calcifications and cholesterol crystals.

Clinical features Craniopharyngioma presents with hypopituitarism, diencephalic manifestations (diabetes insipidus), and/or visual disturbances. Like a pituitary tumor, it can cause hemi- or quadrantanopsia and impair visual acuity; it can also cause occlusive hydrocephalus.

Treatment Craniopharyngioma is best treated by complete resection.

Cavernoma (in the earlier and now superseded terminology, cavernous angioma or cavernous malformation) consists of a well-demarcated agglomeration of capillary blood vessels. Cavernomas can be multiple and familial (genetic locus on chromosome 7). They present with epileptic seizures and hemorrhage.

Epidermoid tumors are found at the base of the brain, are often calcified, and cause focal deficits or epileptic seizures. Their peak incidence is between the ages of 25 and 45 years.

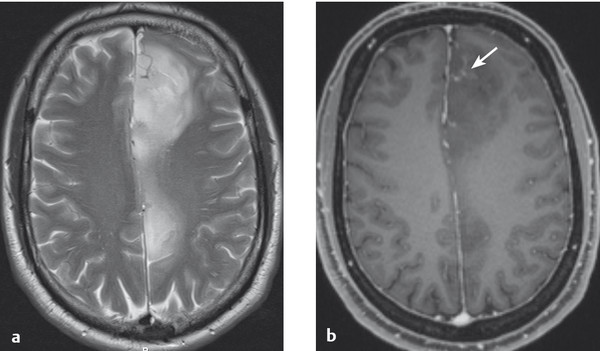

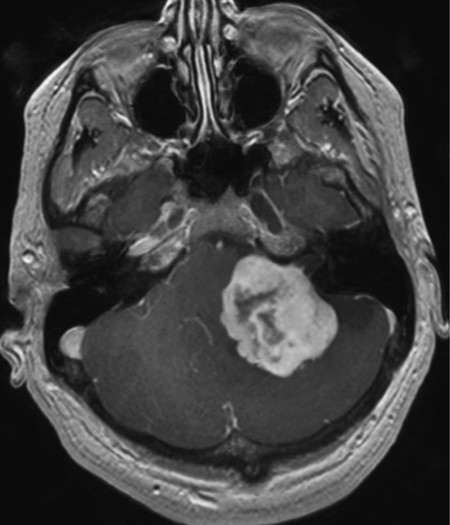

Growth and localization Neurinomas (schwannomas) are benign neoplasms arising from Schwann cells (see ▶ Fig. 7.8). The most common type affects the eighth cranial nerve and is usually (though incorrectly) designated acoustic neuroma ( ▶ Fig. 6.17). This tumor lies in the cerebellopontine angle.

Fig. 6.17 A large acoustic neuroma in the left cerebellopontine angle. Its conical tip extends into the internal acoustic meatus, while the large tumor mass compresses and displaces the brainstem. Marked contrast enhancement on T1-weighted spin-echo images is typical of this type of tumor.

Clinical features Acoustic neuroma presents initially with eighth nerve dysfunction: progressive hearing loss, tinnitus, and disequilibrium. As it grows, it impinges on the other cranial nerves of the cerebellopontine angle, causing facial palsy and trigeminal sensory deficits. Further growth leads to compression of the cerebellum and brainstem, causing cerebellar signs (especially ataxia) and possibly pyramidal tract signs.

Diagnostic evaluation Neurinomas are generally diagnosed by sectional imaging (CT or MRI). CSF examination is not necessary; if nonetheless performed in a patient with acoustic neuroma, it typically reveals marked elevation of the CSF protein concentration. Neurinomas that grow through a neural foramen (e.g., a spinal intervertebral foramen) have a typical hourglass shape.

Treatment Until recently, the optimal treatment of all neurinomas was complete resection. Now many smaller acoustic neuromas can be treated safely and effectively with stereotactic radiosurgery.

Epidemiology Brain metastases account for approximately 15% of malignant brain tumors. The most common sources of brain metastases are lung cancer in men and breast cancer in women, followed in both sexes by melanoma and renal cell carcinoma.

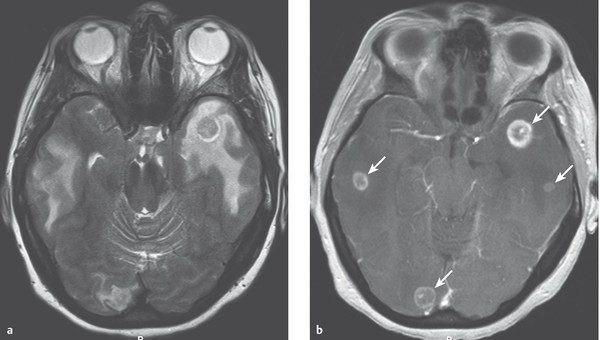

Clinical features and diagnostic evaluation The symptoms and signs of brain metastases depend on their localization. Brain metastases sometimes produce symptoms even before the primary tumor does; in such cases, multiple brain metastases are usually present, even if only a single one is apparent on the neuroimaging study. A case of multiple brain metastases of lung cancer is illustrated in ▶ Fig. 6.18.

Fig. 6.18 Multiple brain metastases of lung cancer. (a) The T2-weighted spin-echo image reveals bitemporal and right occipital lesions with marked surrounding cerebral edema. (b) The T1-weighted image reveals four small contrast-enhancing nodules (→).

Treatment and prognosis Generally speaking, surgical resection is indicated only for solitary metastases, and the indication for surgery should always be carefully considered in the light of the extent of disease. Only approximately 20% of patients who undergo resection of a solitary brain metastasis, followed by radiotherapy, are still alive 5 years later, if they have not already died of the effects of their primary tumor. Brain metastases usually produce extensive peritumoral edema and often cause epileptic seizures; thus, corticosteroids and antiepileptic drugs can be given for palliation. This usually brings about a substantial, if only temporary, clinical improvement.

Additional Information

Neoplastic meningitis is the metastasis of tumor cells to the leptomeninges and subarachnoid space. It can arise with various types of primary tumor and accordingly designated, for example, carcinomatous, gliomatous, or lymphomatous meningitis. It is diagnosed by CSF cytology and carries a poor prognosis.