What happens when I produce a sign or a string of signs? First of all I must accomplish a task purely in terms of physical stress, for I have to ‘uitter’. Utterances are usually considered as emissions of sounds, but one may enlarge this notion and consider as ‘utterances’ any production of signals. Thus I utter when I draw an image, when I make a purposeful gesture or when I produce an object that, besides its technical function, aims to communicate something.

In all cases this act of uttering presupposes labor. First of all the labor of producing the signal; then the labor of choosing, among the set of signals that I have at my disposal, those that must be articulated in order to compose an expression, as well as the labor of isolating an expression-unit in order to compose an expression-string, a message, a text. Fluency or difficulty in speaking, insofar as it depends on a more or less perfect knowledge of linguistic codes, must be examined by semiotics, although I do not propose to go into the matter here. Rossi-Landi (1968) has dealt with this aspect of performance.

Suppose now that, instead of uttering words, I draw an image corresponding to an object, as when I draw a dog in order to advise people to ‘beware’ of the dog in my garden. This kind of sign-vehicle production seems to be rather different from choosing the word /dog/. It implies extra work. Moreover, it might be pointed out that, in order to say /dog/, I had only to choose among a repertoire of established types, and to produce a single occurrence of that type, while in order to draw the image of a dog I have to invent a new type. Thus there are different sorts of signs, some of them entailing a more laborious mode of production than others.

Finally, when I ‘utter’ words or images (or whatever else), I have to labor in order to articulate them in ‘acceptable’ strings of sign-functions; thus I have to labor on their semantic acceptability and understandability. In the same way, when receiving a sentence, even though I do not have to labor in order to produce the sign-vehicles, I do have to labor in order to interpret them. Obviously I can send my messages in order to mention things and states of the world, in order to assert something about the organization of a given code, in order to question or to command. Either to send or to receive these messages (or texts) requires that the sender should foresee, and the addressee isolate, a complex network of presuppositions and of possible inferential consequences. In exchanging messages and texts, judgments and mentions, people contribute to the changing of codes. This social labor can be either openly or surreptitiously performed; thus a theory of code-changing must take into account the public reformulation of sign-functions and the surreptitious code-switching performed by various rhetorical and ideological discourses.

Many of these activities are already studied by existing disciplines; others will have to constitute the object of a new general semiotics. But even those already studied by pre-or extra-semiotic disciplines will then have to be included as branches of a general semiotics, even if it proves convenient to preserve their present affiliation for the time being.

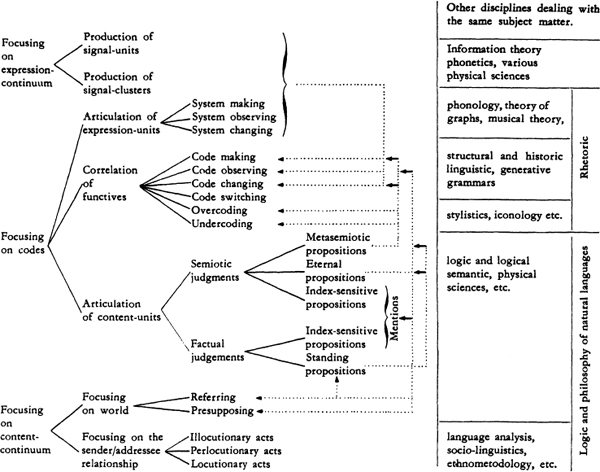

Whereas a theory of codes was concerned both with the structure of sign-function and with the general possibility of coding and decoding, a theory of sign production will thus be concerned with all the problems outlined in Table 31. This table concerns the kind of labor required in order to produce and interpret signs, messages or texts (physical and psychological effort in manipulating signals, in considering, or disregarding, the existing codes; time needed, degree of social acceptance or refusal, energy expended in comparing signs to actual events; pressure exerted by the sender on the addressee, and so on).

The interconnecting arrows linking the various kinds of labor try to correct the oversimplification due to the bi-dimensional format of the diagram; each kind of labor interacts with many others and the process of sign production – in its relationships with the life of codes – represents the result of a network of interacting forces. On the right side are listed the various different approaches that may be applied to the different areas of study, and are in fact actually adopted irrespective of the general semiotic framework that the table proposes. The existence of such a diversity of approaches should not be regarded as a methodological limitation for semiotics; it must simply be listed among the so-called ‘political’ boundaries mentioned in 0.4.

Let us now examine the items of Table 31 one by one.

(i) There is a labor performed on the expression continuum in order to physically produce signals. These signals may be produced as mere physical entities without semiotic function; but as soon as they are produced – or selected among pre-existing entities – as the expression-plane of a sign-function, their mode of production directly concerns semiotics. They may be either already segmented discrete units or material clusters somewhat correlated to a content. In both cases their production presupposes different modes of labor or different techniques of production. These modes of production will be listed in Table 39.

(ii) There is a labor performed in order to articulate expression-units (either already established by an expression system or proposed as the somewhat segmented functives of a new coding correlation). This kind of labor concerns the choice and the disposition of sign-vehicles. There can be expression articulation during the act of constituting (or making) an innovatory code; during a discourse in which the senders try to observe all the laws of the existing codes; within a text where the sender invents new expression units, therefore enriching and changing the system (for example when Laforgue invents the word ‘violupté’ or Joyce ‘meandertale’; see for instance Eco, 1971). Obviously the modification on the expression-plane must be correlated with a modification on the content-plane, otherwise it becomes mere grammatical nonsense; therefore the labor of system observing, system making and system changing on the expression-plane must be considered in relation to the corresponding labor on the content-plane, through the mediation of a labor on the correlation of functives (item iii).

(iii) There is labor performed in order to correlate for the first time a set of functives with another one, and thus making a code; an example of such code making is given by the operation constituting the Watergate Model in chapter 1.

Table 31 Labor presupposed in the process of sign production

(iv) There is labor performed when both the sender and the addressee emit or interpret messages observing the rules of a given code, as in the case of ‘common’ semiotic acts such as the expression /the train from London will arrive at 6.00 P.M./. This kind of disambiguation of expressions was dealt with in chapter 2.

(v) There is a labor performed in order to change the codes shared by a given society. It is a complex process which involves both semiotic and factual judgments (see 3.2.) and other forms of textual manipulation; in this sense it directly involves the aesthetic manipulation of codes (see 3.7.).

(vi) There is labor performed by many rhetorical discourses, above all the so called ‘ideological’ ones (see 3.9.) in which the entire semantic field is approached in apparent ignorance of the fact that its system of semantic interconnections is more vast and more contradictory than would appear to be the case. In order to avoid openly acknowledging the contradictory nature of the Global Semantic System (see 2.13.) ideological discourse must switch from one code to another without making the process evident. Code switching is also performed in aesthetic texts, not as a surreptitious device but as a manifest procedure, in order to produce planned ambiguities and multi-levelled interpretations (see 3.7.1.).

(vii) There is labor performed in order to interpret a text by means of a complex inferential process. This process is mainly based on abductions and produces forms of overcoding (on the basis of a first level of pre-established rules new rules are proposed which articulate more macroscopic portions of the text) and of undercoding (in the absence of reliable pre-established rules, certain macroscopic portions of the text are assumed to be the only pertinent units even though the more basic combinational rules and their corresponding units remain unknown). To this important aspect of text interpretation the whole of section 14 of chapter 2 has been devoted.

(viii) There is labor performed by both the sender and the addressee to articulate and to interpret sentences whose content must be correctly established and detected. Section 2 of the present chapter will deal with these propositions (such as meta-semiotic, eternal and standing propositions) commonly called ‘statements’, while section 3 will deal with the index-sensitive sentences used in mentioning or referring, and will therefore also deal with many problems regarding item (ix).

Semiotic judgments predicate of a given semiotic item what is already attributed to it by a code (see 3.2.). They can assume three forms: (a) meta-semiotic propositions presupposing a ‘performative’ format («I state that from now on the word ‘ship’ can also be applied to vehicles for space-travel»); (b) eternal propositions of the type «bachelors are males»; (c) index-sensitive propositions coupling certain objects, taken as representative of a bunch of properties, to certain words («this object is a pencil»); this last kind of semiotic judgment, insofar as it is pronounced about actual objects, is also called a ‘mentioning or referring act’ and can be studied under the same profile as index-sensitive factual propositions (see 3.3.1.).

Factual judgments predicate of a given semiotic item what was not attributed to it by the code. This judgment can be of two types: (a) index-sensitive propositions that attribute to a token occurrence of a semiotic type a factual property that, by definition, does not pertain to other ‘tokens’ of the same ‘type’ (“this pencil is black”); this kind of judgment, otherwise called ‘occasion proposition’ (see 2.5.3.), does not modify the semantic representation of a given semiotic item and in this sense it could be left aside by a semiotic inquiry, being better dealt with by a theory of the extensional verification of correspondences between propositions and states of the world; but all the same it has some semiotic purport insofar as, in order to predicate a semantic item as the property of an object, one will need a survey and a definition of this object’s properties and such an operation has a semiotic aspect (see 3.3.3. – 3.3.6.); (b) Standing non index-sensitive propositions like “The moon has been walked on by human beings”: as will be seen in 3.2.2, this kind of judgment when pronounced for the first time is a factual index-sensitive proposition (something is predicated of a given semantic item that no code attributed to it, and it is asserted for the first time by means of an indexical device of the type “in this moment” or “from now on”); but when these judgments are accepted by a society as true, then they assume a meta-semiotic function and gradually become semiotic judgments.

(ix) There is labor performed in order to check whether or not an expression refers to the actual properties of the things one is speaking of. This labor is strictly linked to the one performed in order to grasp the content of the index-sensitive semiotic and factual sentences, or mentions. To this problem section 3 is devoted.

(x) There is labor performed in order to interpret expressions on the basis of certain coded or uncoded circumstances. This labor of inference is linked both to the inferential labor required in order to understand something (thereby becoming the proper concern of a theory of perception and intelligence) and to the inferential labor performed within the text (see vii) which must be considered as an aspect of the labor of over-and undercoding (see 2.14.).

(xi) There is labor that the sender performs in order to focus the attention of the addressee on his attitudes and intentions, and in order to elicit behavioral responses in other people. This kind of labor (which will be considered in many of the following sections) was usually studied by the so-called theory of speech acts. Provided that in the present perspective the notion of ‘speech act’ is taken as concerning not merely verbal acts but every kind of expression (images, gestures, objects), it may be noted that among these various communicational acts figure not only the so-called locutionary ones, which may correspond to semiotic and factual judgments, but also all those types of expression that do not express any assertion but on the contrary perform an action or ask, command, establish a contact, arouse emotions and so on (illocutory and perlocutory acts).(1)

The present chapter 3 will not deal with all problems concerning a theory of sign-production; it will only deal with such specific problems as require direct, immediate and exclusive attention from a semiotic point of view. Let me stress the order of priorities which governs the organization of the eight following sections.

The labor performed in shaping the expression-continuum in order to produce the concrete occurrence of a given sign brings into immediate evidence the fact that there are different kinds of signs. If a general theory of codes, providing the notion of sign-function along with the notion of segmentation of both the expression and the content levels, seemed to offer a unified definition for every kind of sign, the concrete labor of producing these signs obliges one to recognize that there are different modes of production and that these modes of production are linked to a triple process: (i) the process of shaping the expression-continuum; (ii) the process of correlating that shaped continuum with its possible content; (iii) the process of connecting these signs to factual events, things or states of the world. These processes are strictly intertwined; once the problem of shaping the continuum is posed, that of its relationship with the content and the world arises. But at the same time one realizes that what are commonly called types of sign are not the clear-cut product of one of these operations, but rather the result of several of them, interconnected in various ways.

One also realizes that there are some signs that seem better adapted to the expression of abstract correlations (like symbols) and others that would appear to be more useful in direct reference to states of the world, icons or indices, which are more immediately involved in the direct mentioning of actual objects. In order to understand these points it would seem more profitable to tackle the problem of the various kinds of judgments pronounced about the world or codes and acts of mentioning things straight away. So instead of following the theoretical order outlined in Table 31 I will follow a sort of phenomenological order: in pronouncing judgments and performing mentions one discovers how one is using both verbal devices and other sorts of signs, such as for example, a pointing finger or an object taken as an example; at this point one should be able to single out both their differences and their similarities, and to realize that these differences do not characterize the various kinds of signs in themselves but rather discriminate between modes of sign production, every so-called sign being the result of many such operations.

Thus a typology of signs will give way to a typology of modes of sign production, thereby showing, once again, that the notion of ‘sign’ is a fiction of everyday language whose place should be taken by that of sign-function.

To communicate means to concern oneself with extra-semiotic circumstances. The fact that they can frequently be translated into semiotic terms does not eliminate their continuous presence in the background of any phenomenon involving sign production. In other words, signification is confronted with (and communication takes place within) the framework of the global network of material, economic, biological and physical conditions then prevalent. The fact that semiosis lives as a fact in a world of facts limits the absolute purity of the universe of codes. Semiosis takes place among events, and many events happen that no code could have anticipated. The semiotic creativity allowed by codes thus demands that these new events be named and described. The structure of codes can sometimes be upset by an innovatory statement concerning events which do not fit in with the organization of the content. What happens when messages state something concerning an as yet unorganized and non-segmented content? Does the new set of cultural units thus introduced into the social competence modify the pre-established semantic field? And how? This point prompts a return to an old philosophical distinction, widely discussed in logic and linguistic analysis, between analytic and synthetic judgments.

Considered from the point of view of a referential semantics this distinction is open to the broadest criticism. One might well wonder (cf. White, 1950) why such a statement as «all men are rational animals» is considered by traditional philosophers to be an analytic judgment and «all men are bipeds» a synthetic one. In effect, if one predicates the ‘objectivity’ of certain properties, the reason for the distinction between these two types of judgments is not evident. But Cassirer has already given an answer to this problem in Das Erkenntnisproblem in der Philosophie und Wissenschaft der neueren Zeit, II, 8, II. The analytic judgment is the one in which the predicate is contained implicitly in the concept of the subject, and the synthetic judgment is that in which the predicate is added to the subject as an entirely new attribute, due to a synthesis obtained from the data of experience.

Why then, according to Kant, is «all bodies are extensive» analytic and «all bodies are heavy» synthetic? Simply because Kant referred to the ‘patrimony of thought’ which he presumed to be known to his contemporaries. It is worth noting that «body» for him was not a referent but above all a cultural unit. And from the time of Descartes up to Newton and the encyclopedists, «extension» was attributed to this cultural unit as an essential quality which was a part of its definition, whereas «weight» was considered an accessory and contingent quality which did not therefore enter into the same definition. Judgments are either analytic or synthetic according to the existing codes and not according to the presumed natural properties of the objects. Kant explicitly states in the first Kritik that “the activity of our reason consists largely . . . in the analysis of ideas which we already have with regard to objects”. Since, however, the opposition ‘analytic vs. synthetic’ co-involves too many philosophical problems, let us develop the above suggestion within a more specific semiotic context, in this way proposing a more suitable opposition.

Let us call semiotic a judgment which predicates of a given content (one or more cultural units) the semantic markers already attributed to it by a previous code; let us call factual a judgment which predicates of a given content certain semantic markers that have never been attributed to it by a previous code. Therefore /every unmarried man is a bachelor/ is a semiotic judgment solely because there exists a conventional code which refers to a compositional tree which possesses among its markers «never married». Instead /Louis is a bachelor/ is undoubtedly a factual judgment. On May 5, 1821, /Napoleon died on Saint Helena/ constituted a factual judgment. But from that moment on, the same statement has constituted a semiotic judgment because the code has fixed in the compositional tree of /Napoleon/ the definitional connotation «died on Saint Helena». On the other hand /Napoleon, after the battle of Marengo, drank a cup of coffee/ is a factual statement that can hardly be transformed into a semiotic one. Thus White (1950), criticizing the analytic-synthetic distinction, rightly affirms that a judgment is analytic on the basis of a convention and that, when the convention changes, the judgments which were once analytic can become synthetic, and vice versa. But what he intended as a limitation of the logical distinction between analytic and synthetic is instead the condition for the validity of the semiotic distinction between semiotic and factual judgments.

I shall briefly consider a particular example of these judgments, that is, semiotic (or meta-semiotic) and factual statements, granted that these are not to be confused with index-sensitive judgments or mentions (see 2.5.3., where non-statements are called ‘occasion propositions’; mentions will be examined in 3.3.). It should be recalled that:

a) /This is a one dollar bill/ is not a statement: it is a mention (see 3.3).

b) /One dollar is worth 625 lire/ was a semiotic statement in 1971, thereby expressing a coded signifying relationship.

c) /One dollar is worth 580 lire/ was an astonishing factual statement emitted in a given day during 1972.

d) /One dollar is worth 580 lire/ became a semiotic statement of type (b) during 1972.

e) In order to make the factual statement (c) become the new semiotic statement (d) it was necessary that (c) should take the form of a meta-semiotic statement, presupposing or explicitly stating a performative formula such as: /The President of the United States (or the Bank of Italy, or the European Common Market) establishes that, from today on, everybody must accept the financial convention that one dollar is worth 580 lire/. The fact that since 1972 such a meta-semiotic statement has changed so many times only confirms yet again that many codes are very weak and transient, thus lasting l’espace d’un matin, like the rose. But a rose is no less a rose – witness Gertrude Stein – because it is so short-lived; in the same way a code is a code (is a code is a code) provided that a meta-semiotic statement has conventionally established a certain equivalence and a society has accepted it, and remains so until the arrival of another code-changing meta-semiotic adjustment.

Finally, the example of the dollar is particularly apposite, because the financial market represents a perfect case of coupling between units from different content systems, each unit being semantically defined by the opposition it entertains with every other unit. Therefore factual statements sometimes upset and restructure the codes(2).

Even though to designate these operations of content-articulation I have employed terms borrowed from logic (which is mainly concerned with verbal expressions), all these types of propositions also concern non-verbal expressions. The Encyclopaedia Britannica is a text which sets out a lot of meta-semiotic and semiotic statements not only because it records many verbal definitions of various semantic units but also because it uses drawings and photographs in order to analyze the components of the same semantic units (for example visually describing the parts of human body or the elementary components of a four-stroke engine). The New York Times sets out a lot of factual statements not only by means of words but also of photographs or diagrams.

The visual demonstration of the theorem of Pythagoras is a semiotic statement. A road signal announcing a dangerous crossing is at the same time a factual statement and a mention. Other road signals commanding one to «stop» or «beware!» or forbidding right of way are communicational acts that are listed under item (xi). The drawing of a horse with the caption /horse/ represents an index-sensitive semiotic judgment; the portrait of the last winner of the Nobel Prize with the caption /this man has won the Nobel Prize/ constitutes an index-sensitive factual judgment. The Neapolitan gesture meaning «I am hungry» is an index-sensitive factual judgment. And so on.

This dialectic between codes and messages, whereby the codes control the emission of messages, but new messages can restructure the codes, constitutes the basis for a discussion on the creativity of language and on its double aspect of ‘rule-governed creativity’ and ‘rule-changing creativity’.

Factual statements, as usually performed, are an example of creativity permitted by the rules of the code. One can verbally define a new physical particle using and combining pre-established elements of the expression-form in order to introduce something new in the content-form; one can technically define a new chemical compound using and combining pre-existing content-units in a new way, in order to fill up an empty space within a pre-established system of possible semantic oppositions; one can thus alter the structure of both the expression and the content-system following their dynamic possibilities, their combinational capacities – as if the whole code by its very nature demanded continual re-establishment in a superior state, like a game of chess, where the moving of pieces is balanced out by a systematic unit on a higher level. Thus the possibility of meta-semiotic statements which alter the compositional spectrum of a lexeme and reorganize the readings of the sememe is also based on the pre-established elements and combinational possibilities of the code(3).

Signs are used in order to name objects and to describe states of the world, to point toward actual things, to assert that there is something and that this something is so and so. Signs are so frequently used for this end that many philosophers have maintained that a sign is only a sign when it is used in order to name things. Therefore these philosophers have tried to demonstrate that a notion of meaning as separated from the ‘real’ and verifiable ‘denotatum’ of the sign, that is, the object or the state of the world to which the sign refers, is devoid of any real purport. Thus, even when they accept a distinction between meaning and referent (or denotatum) and do not equate the former with the latter, their interest is exclusively directed toward the correspondence between sign and denotatum; the meaning being taken into account only insofar as it can be made to correspond to the denotatum in specular fashion.

The theory of codes outlined in chapter 2 not only tried to restore the meaning’s autonomous status, but even deprived the term /denotation/ of any extensional or referential relevance. The foregoing section, even though it has considered factual statements, has not linked these judgments to the facts about which they are stated. What is characteristic of a factual judgment of the kind examined in the above section is that although it seems to concern facts it can also be used in order to assert non-existent factual states, and therefore to lie.

If I assert that ‘the man who invented eye-glasses was not Brother Alessandro della Spina but his cell-mate’, I do not challenge an established semiotic statement, for the inventor of eye-glasses is a decidedly imprecise historical entity and the encyclopedias are rather vague and cautious on this subject, but I do make a factual statement, or a ‘standing proposition’. It would be very difficult to check whether my judgment is true or false, and some documentation would clearly be needed; but all the same what I have produced is a factual statement (whether true or false) insofar as it does not assert something definitely recorded by a cultural code. Thus factual judgments of this type are not necessarily verified by an actual state of the world or a present entity. In this sense it is possible to assume that they have a meaning irrespective of their verification, and yet once their meaning is understood they demand verification.

Let us now consider another type of factual judgment, the index-sensitive one, i.e. the act of mentioning something actually present, as in /this pencil is blue/ or /this is a pencil/. As was suggested in 3.1., there is a difference between the two examples, and the second can be registered as index-sensitive but semiotic. Nevertheless both seem to be acts of mentioning (or of referring to) something. It may be assumed that in this case their meaning depends directly on the actual thing they refer to, but such an assumption would challenge the independence of meaning from referent maintained in chapter 2.5.

Strawson (1950) says that “mentioning or referring is not something an expression does; it is something that someone can use an expression to do”. From this point of view ‘meaning’ is the function of a sentence or expression; mentioning and referring, and truth and falsity, are functions of the use of the sentence or expression. “To give the meaning of an expression . . . is to give general directions for its use to refer to or mention particular objects and persons; to give the meaning of a sentence is to give general directions for its use in making true or false assertions”.(4) Let us try to translate Strawson’s suggestions into the terms of a theory of codes. To give general directions for the use of an expression means that the semantic analysis of a given sememe establishes a list of semantic properties that should correspond to the supposedly extra-semiotic properties of an object. If this sounds somewhat Byzantine, one could reformulate it as follows: to give general directions for the use of an expression in referring means to establish to which actual experiences certain names, descriptions or sentences can be applied. Clearly this second definition, despite its correspondence to our normal way of speaking, says very little. Moreover, one has to face the question: how does one establish the rules of such an application?

So one must return to the first formulation of the problem. But at this point a new problem arises: how does one establish a correspondence between the semantic properties of a sememe (which clearly is a matter for semiotics) and the supposedly non-semantic properties of a thing? Can the mentioned thing assume the status of a semiotically graspable entity? For, either semiotics cannot define the act of mentioning or in the act of mentioning the thing mentioned should be viewed in some way as a semiotically graspable entity. So we must re-examine the whole process of mentioning.

The act of referring places a sentence (or the corresponding proposition) in contact with an actual circumstance by means of an indexical device. We shall call these indexical devices pointers. A pointing finger, a directional glance, a linguistic shifter like /this/ are all pointers. They are apparently characterized by the fact that they have as their meaning the object to which they are physically connected. I have shown in 2.11.5. that this is not true. Any pointer has first of all a content, a marker of «proximity» or «closeness» independently of the actual closeness of an object. But for the sake of the present analysis let us retain the common notion of pointer as something pointing toward something else.

Suppose now that I point my forefinger toward a cat, saying: /This is a cat/. Everybody would agree on the fact that the proposition «The object I have indicated by the pointer is a cat» is true (or that the proposition «The perceptum at which I pointed at moment x was a cat» is true; to put the matter simply, everyone would agree that what I had called a cat was a cat). In order that the above propositions be true I must be able to translate them as follows: “The perceptum connected with my forefinger at moment x represents the token occurrence of a perceptual type so conceptually defined that the properties possessed by the perceptual model systematically correspond to the semantic properties of the sememe «cat», and both sets of properties are usually represented by the same sign-vehicles”.

At this point the referent-cat is no longer a mere physical object. It has already been transformed into a semiotic entity. But this methodological transformation introduces the problem of the semiotical definition of the percepta (see 3.3.4.). If the sentence was a semiotic act and the cat an empirical perceptum it would be very difficult to say what the expression /is/ was. It would not be a sign, since /this is/ is the connecting device joining a complex sign (the sentence) to an actual perceptum. It would not be a pointer, inasmuch as the pointer points toward the perceptum to be connected with the sign, while /is/ seems to actually perform the connection itself. The only solution seems to be: /this is a cat/ means «the semantic properties commonly correlated by the linguistic code to the lexeme /cat/ coincide with the semantic properties that a zoological code correlates to that perceptum taken as an expressive device». In other terms: both the word /cat/ and that token perceptum //cat// culturally stand for the same sememe. This solution undoubtedly looks rather Byzantine – but only if one is accustomed to think that a ‘true’ perception represents an adaequatio rei et intellectus or is a simplex apprehensio mirroring the thing, as the Schoolmen maintained. But let us simply suppose that the expression /this is a cat/ is uttered in the presence of an iconic representation of a cat. All the above reasoning immediately becomes highly acceptable; we have a sign-vehicle (a) which is a linguistic expression to which a given content corresponds; and we have a sign-vehicle (b) which is an iconic expression to which a given content also corresponds. In this case we are comparing two sets of semantic properties and /is/ can be read as /satisfactorily coincides/ (that is: the elements of the content plane of a code coincide with the element of the content plane of another code; it is a simple process of transliteration)(5). Why does the mentioning act in the presence of a real cat seem so different to us? Clearly because we do not dare to regard perception as the result of a preceding semiotic act, as had been suggested by Locke, Peirce and many other philosophers.

There is a brief passage from Peirce (5.480) which suggests a whole new way of understanding real objects. Confronted with experience, he says, we try to elaborate ideas in order to know it. “These ideas are the first logical interpretants of the phenomena that suggest them, and which, as suggesting them, are signs, of which they are the . . . interpretants”. This passage brings us back to the vast problem of perception as interpretation of sensory disconnected data which are organized through a complex transactional process by a cognitive hypothesis based on previous experiences (cf. Piaget, 1961). Suppose I am crossing a dark street and glimpse an imprecise shape on the sidewalk. Until I recognize it, I will wonder “what is it?” But this “what is it?” may be (and indeed sometimes is) translated as “what does it mean?” When my attention is better adjusted, and the sensory data have been better evaluated, I finally recognize that it is a cat. I recognize it because I have already seen other cats. Thus I apply to an imprecise field of sensory stimuli the cultural unit «cat». I can even translate the experience into a verbal interpretant (/I saw a cat/). Thus the field of stimuli appears to me as the sign-vehicle of a possible meaning which I already possessed before the perceptual event.

Goodenough (1957) observed that: “a house is an icon of the cultural form or complex combination of forms of which it is a material expression. A tree, in addition to being a natural object of interest to a botanist, is an icon signifying a cultural form, the very same form which we also signify by the word tree. Every object, event or act has stimulus value for the members of a society only insofar as it is an iconic sign signifying some corresponding form in their culture . . . . ” Clearly from an anthropological point of view this position is close to what was said in the Introduction and to what will be said in 3.6.3. on the way in which every object may potentially become a sign within the environment of a given culture; and clearly the theory developed here finds many points of contact with the ideas suggested by Peirce.

As Peirce writes: “Now the representative function of a sign lies neither in its material quality nor in its pure demonstrative application; because it is something which the sign is, not in itself or in a real relation to its object; but which it is to a thought, while both of the characters just defined belong to the sign independently of its addressing to any thought. And yet if I take all the things which have certain qualities and physically connect them with another series of things, each to each, they become fit to be signs. If they are not regarded as such they are not actually signs, but they are so in the same sense, for example, in which an unseen flower can be said to be red, this being also a term relative to a mental affection” (5.287).

In order to assert that objects (insofar as they are perceived) can also be approached as signs, one must also assert that even the concepts of the objects (as the result or as the determining schema of every perception) must be considered in a semiotic way. Which leads to the straightforward assertion that even ideas are signs. This is exactly the philosophico-semiotical position of Peirce: “whenever we think, we have present to the consciousness some feeling, image, conception, or other representation, which serves as a sign” (5.283). But thinking, too, is to connect signs together: “each former thought suggests something to the thought which follows it, i.e., is the sign of something to this latter” (5.284).

Peirce is in fact following a very ancient philosophical tradition. Ockham (in I Sent., 2,8; Ordinatio, 2,8; Summa totius logicae, 1, 1) insists on the fact that if the linguistic sign points back to a concept (which is its content), alternatively the concept is a sort of sign-vehicle able to express (as its content) singular things. The same solution can be found in Hobbes (Leviathan, i, 4), not to speak of Locke’s Essay concerning Human Understanding: here Locke explicitly asserts the identity between logic and semiotics (IV,20) and the semiosic nature of ideas. These ideas are not (as the Schoolmen believed) a mirroring image of the thing; they too are the result of an abstractive process (in which – let it be noted – only some pertinent elements have been retained) which gives us not the individual essence of the named things but their nominal essence. This nominal essence is in itself a digest, a summary, a elaboration of the signified thing. The procedure leading from a bunch of experiences to a name is the same as that which leads from the experience of things to that sign of things, the idea. Ideas are already a semiotic product.

Obviously in Locke’s system the notion of idea is still linked to a mentalistic point of view; but it is sufficient to replace the term ‘idea’ (as something which takes place in the mind) by ‘cultural unit’ (as something which can be tested through other interpretants in a given cultural context) and Locke’s position reveals itself as very fruitful for semiotic purposes. Berkeley too (Treatise, Intr., 12) speaks of an idea as general when it represents or stands for all particular ideas of the same sort.

Obviously this interesting chapter of a future history of semiotics deserves a more careful elaboration. But it was in any case important to undertake this first tentative exploration in order to find some historical roots for the approach here proposed. It will help one to understand why throughout the entire history of philosophy the notion of linguistic meaning has been associated with that of perceptual meaning, by means of an identical term (or of a pair of homonymous terms.)

According to Husserl (Logische Untersuchungen, I, IV, VI) the dynamic act of knowing implies an operation of “filling up” which is simply an attribution of sense to the object of perception. He says that to name an object as /red/ and to recognize it as red are the same process, or at least that the manifestation of the name and the intuition of the named are not clearly distinguishable. It would be worth ascertaining to what extent the idea of ‘meaning’ found in the phenomenology of perception agrees with the semiotic notion of a cultural unit. A rereading in this light of Husserl’s discussions might induce us to state that semiotic meaning is simply the socialized codification of a perceptual experience which the phenomeno-logical epoché should restore to us in its original form. And the significance of daily perception (before the epoché intervenes to refresh it) is simply the attribution of a cultural unit to the field of perceptual stimuli as has been said above. Phenomenology undertakes to rebuild from the beginning the conditions necessary for the formation of cultural units which semiotics instead accepts as data because communication functions on the basis of them. The phenomenological epoché would therefore refer perception back to a stage where referents are no longer confronted as explicit messages but as extremely ambiguous texts akin to aesthetic ones.

This is not the place to study this problem in greater depth. Suffice it to say that we have indicated another of semiotics’ limits, and that it would be worth while to continue research on this in relation to the genesis of perceptual signification.

Let us now return to our example of the expression /this is a cat/. One is now ready to accept the idea that an act of mentioning or referring is made possible by a very complicated previous semiosic process which has already constituted the perceived object as a semiotic entity: (i) I recognize the cat as a cat, that is, I apply a cultural schema (or idea, or concept) to it; (ii) I understand the token cat as the sign-vehicle of the type cat (the corresponding cultural unit) concerning myself only with its semantic properties and excluding individualizing physical properties which are not pertinent (clearly the same happens, with some other mediating processes, when I say /this cat is big, black and white/); (iii) among the semantic properties of the cultural unit «cat» I select the ones which are in accordance with the semantic properties expressed by the verbal sign-vehicle.

I thus compare two semiotic objects, that is, the content of a linguistic expression with the content of a perceptual act. At this point I accept the equation posited by the copula /is/. Inasmuch as the equation represents a sort of metalinguistic act, associating a linguistic expression with the living ‘expression’ of a cultural construct (and thereby trying to establish an equivalence between sign-vehicles coming from different codes), it can either be accepted or refused – insofar as it does or does not satisfy the semantic rules imposing as predicates of a given item certain other items, able to amalgamate together through some common semantic properties. So the copula /is/ is a metalinguistic sign meaning «possesses some of the semantic properties of».(6) In some circumstances the metalanguage might not be a verbal one: as when /is/ is replaced by a pointing finger meaning both «this» and «is».

The above discussion (from 3.3.3. to 3.3.5.) has made clear the status of semiotic index-sensitive judgments. But perhaps the nature of factual index-sensitive judgments, such as /this cat is one-eyed/ remains more obscure. In this case I assign to the token of the type-cat a property which is not recognized by the code, so that we would seem to be back with the problem of the relation between on the one hand two semiotic constructs (the sememe «cat» and the conceptual type «cat» and on the other a mere perceptum. Except that the property of being one-eyed is not a mere perceptum, but rather a sort of ‘wandering’ semantic property, coming from some organized subsystem, which is recognized as such and attributed to this one cat, viewed as the occurrence of a more general model. The single occurrence of a type can have more characterizing properties than its model (thus the occurrence of a word shows a lot of free variants), it cannot however have properties which are incompatible with its type.

To predicate new properties of an object is not so different from producing phrases which are semantically acceptable. I can accept well-formed phrases like /the pencil is green/ or /the man sings/ and I must usually refuse phrases like /the pencil sings/ or /the man is green/; it is simply a matter of semantic amalgamation.

Therefore I can accept factual judgments like /this pencil is blue/, for pencils are usually either black or colored, /this pencil is long/ because pencils are physical objects possessing dimensional properties, and /this man sings/ because men can emit sounds. All of them are acceptable factual index-sensitive judgments. On the contrary /this pencil is two miles long/, /this pencil is vibrating at the speed of 2,000 w.p.s./ or /this man is internally moved by a four-stroke engine/ are abnormal factual judgments for they nourish an inner semantic incompatibility. Thus if I said /this cat is four feet long/ there would be two possibilities: either I see that the cat is not actually that long, and in this sense I am simply associating unappropriate words with the living expression of a semantic property that I can conceptually detect and that I could verbally express in another way; or I am really ‘telling the truth’. But if I have told the truth, I am obliged to ask myself: do four-foot-long cats really exist? All my knowledge about cats tells me that they do not usually share such a property, i.e. that the conceptual construct «cat» (corresponding to the sememe «cat» does not possess such a property. Therefore I must assume that what I have seen is perhaps not a cat but a panther. Suppose that I now check and I discover that it has all the properties of a cat and none of the properties of a panther, but that all the same it really is four feet long; then my perception, once it is conceptualized, does not coincide with the conceptual construct that made it possible. I must therefore reformulate the conceptual construct (and therefore the corresponding sememe); it is possible that a mutation may have changed the size of some cats. So I must emit a factual statement (/some cats are four feet long/) after which, by means of a meta-semiotic judgment, I can change the code.

The case of the four-foot-long cat is one of an actually perceived subject of which a puzzling property must be predicated. There are cases of predication in which the property does not create problems, but the subject does. Such is the case of the famous sentence /the present king of France is bald/. To engage in the Olympic Games that this sentence has provoked in contemporary semantics may help to solve the final problem about mentioning.

Everyone is agreed that the sentence in question, if uttered in the present century, is rather puzzling. It may also be suggested that the sentence is meaningless since ‘definite descriptions’ have a meaning only when there is a single object for which they stand. We have already provided the answer to such an assumption, and a theory of codes demonstrates that a description like /the king of France/ is fully endowed with meaning. It is not necessary to assume that a description like /the king of France/ must be verified by a presupposition, thus asking for an existential verification. This theory holds good when attributing a truth value to a proposition; so that if the description /the husband of Jeanne d’Arc/ does not have a ‘referential index’ a statement like /the husband of Jeanne d’Arc came from Brittany/ arouses a lot of interesting questions in terms of extensional semantics. But /the king of France/ stands for a cultural unit, not a person; not only does it share with /the husband of Jeanne d’Arc/ the quality of meaning something, but also it can correspond or not correspond to somebody who actually existed and who, in a possible world, could continue to exist.

So suppose then that someone states that /the king of France is wise/ as Strawson suggests; the expression is endowed with meaning, so the problem is to know under what circumstances it is uttered; if it is used in order to mention Louis XIV, it can be said to be acceptable, but if used in order to mention Louis XV some might judge it rather over-evaluative.

Suppose that I now say /this is the king of France/ pointing with my forefinger toward the President of the French Republic. This is the same as saying /this is a cat/ while indicating a dog. There is a semantic incompatibility between the properties of the sememe and the properties of the cultural unit represented by the indicated person, taken as an occurrence of a conceptual construct.

Suppose that I now say /this man is bald/ when referring to a long haired pop-singer; this represents a typical case of misuse of language. One need only translate the expression as /this man is a bald man/ for it to become clear that I am attributing certain semantic properties to a percept that cannot be taken as an occurrence of a more general model for bald men.

Suppose that I now say /the king of France is bald/; in itself the expression is meaningful and may become true when I use it in order to mention Charles the Bald, who was elected emperor in 875 A.D. If I use the sentence in order to mention Louis XIV the sentence is false. However, both mentions presuppose an indexical device; if I utter them I must in some way indicate which king I am referring to. The same happens when I say /the present king of France is bald/. The word /present/ is in fact a pointer, and as a pointer is a shifter (see 2.11.5.).

What does /the present king of France is bald/ mean? It has the following deep semantic structure: «there is a king of France. The king of France is bald». But /there/ is an ambiguous device : it has the sense of /there/ in /there are many books in the world/ and that of /there/ in /they are there/.. The first /there/ has an imprecise adverbial function, the second has the meaning «in this precise place» and an almost substantive function as in /he is in there/.

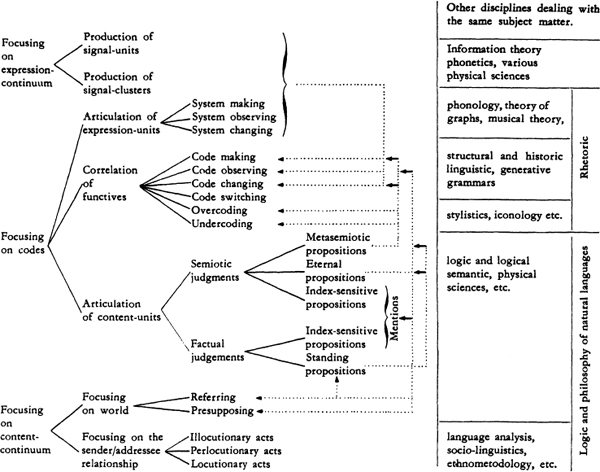

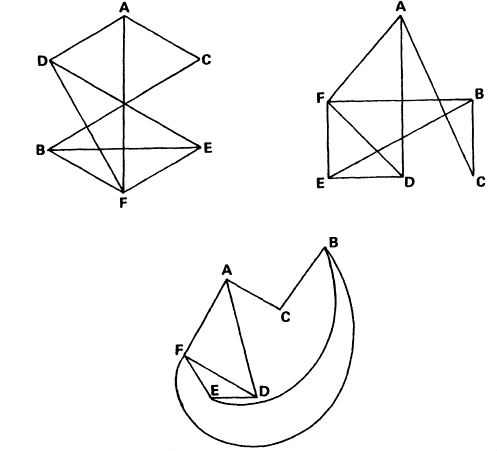

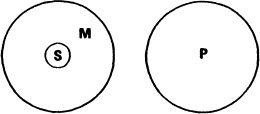

One should thus say: /there is there a king of France/, which would mean: «in the precise historical moment (or in the precise spatial environment) within which the sender of the message is speaking». And this is exactly the meaning of /present/, whose compositional tree could be represented as in Table 32 (according to 2.11.5.)

where the absence of an index suggests an imprecise and multidirectional closeness. In terms of meaning the addressee receives the imperative content «point your attention toward the immediate temporal context». In terms of mentioning the addressee does not discover in such a temporal context a possible perceptum that could correspond to a conceptual type having the properties assigned by a code to a «king of France». Therefore the communication ‘miscarries’; this proposition is neither true nor false, but simply inapplicable to any circumstance, and therefore misused. It is the same when I say /this is the king of France and he is bald/ while pointing my finger toward nothing.

Thus /the present king of France is bald/ is a meaningful sentence that, when considered as a mention, is an example of a misuse of sign production. Whereas /the king of France is bald/ is a meaningful sentence that, when used for imprecise mentions (for instance when uttered without specifying or presupposing any uncoded contextual selection) is simply useless. The proof is that, when hearing it, people will ask: “which one?”, thus demanding an indexical circumstantial marker(7).

Even though a definition of sign-function for every type of signs has been given in 2.1. and the process of sign production has also been examined from the point of view of many non-verbal signs, it would nevertheless be somewhat reckless to maintain that there is no difference between various types of signs. It is indeed possible to express a given content both by the expression /the sun rises/ and by another visual expression composed of a horizontal line, a semicircle and a series of diagonal lines radiating from the imaginary center of the semicircle. But it would seem more difficult to assert that /the sun also rises/ by means of the same visual device and it would be quite impossible to assert that /Walter Scott is the author of Waverley/ by visual means. It is possible to assert both verbally and kinesically that I am hungry (at least in Italian!) but it is impossible to assert by means of kinesic devices that «The Kritik der reinen Vernunft proves that the category of causality is an a priori form while space and time are pure intuitions» (even if Harpo Marx got remarkably near it). The problem could be solved by saying that every theory of signification and communication has only one primary object, i.e. verbal language, all other languages being imperfect approximations to its capacities and therefore constituting peripheral and impure instances of semiotic devices.

Thus verbal language could be defined as the primary modelling system, the others being only “secondary”, derivative (and partial) translations of some of its devices (Lotman, 1967). Or it could be defined as the primary way in which man specularly translates his thoughts, speaking and thinking being a privileged area of a semiotic enquiry, so that linguistics is not only the most important branch of semiotics but the model for every semiotic activity; semiotics as a whole thus becomes no more than a derivation from linguistics (Barthes, 1964).

Another assertion, metaphysically more moderate, but possessing the same practical import, might consist in maintaining that only verbal language has the property of satisfying the requirement of ‘effability’. Thus not only every human experience but also every content expressed by means of other semiotic devices can be translated into the terms of verbal language, while the contrary is not true. The effability power of verbal language is undoubtedly due to its great articulatory and combinational flexibility, which is obtained by putting together highly standardized discrete units, easily learned and susceptible to a reasonable range of non-pertinent variations.

An objection to this approach might run as follows: it is true that every content expressed by a verbal unit can be translated into another verbal unit; it is true that the greater part of the content expressed by non-verbal units can also be translated into verbal units; but it is likewise true that there are many contents expressed by complex non-verbal units which cannot be translated into one or more verbal units (other than by means of a very weak approximation). Wittgenstein underwent this dramatic revelation (as the Acta Philosophorum relate) when during a train journey, Professor Sraffa asked him what the ‘meaning’ of a certain Neapolitan gesture was.

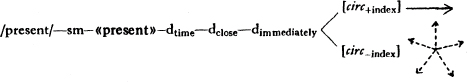

Garroni (1973) suggests that there is a set of contents conveyed by the set of linguistic devices L and a set of contents that are usually conveyed by the set of non-linguistic devices NL; both sets contribute to a subset of contents which are translatable from L into NL or vice versa, but such an intersection leaves aside a vast portion of ‘unspeakable’ but not ‘unexpressible’ contents.

There are many proofs to support this theory. The power of verbal language is demonstrated by the fact that Proust successfully created the impression of rendering through words almost the entire range of perceptions, feelings and values embodied in an impressionist-like painting; but it is no chance that he was obliged to analyze an imaginary painting (by Elstir) for even a summary survey of a real painting could have suggested the existence of portions of content that the linguistic description did not cover. On the other hand it is quite clear that no painting (even if organized as some sort of supremely skillful comic strip with thousands and thousands of frames) could get across all that is conveyed by the Recherche.(8)

Whether there are NL semiotic systems; whether what they convey might be or ought to be called ‘content’ in the sense used up to now; whether as a result semantic markers and their interpretants have to be not only verbal devices but also organized and structured perceptions, habits, behaviors and so on; all this constitutes one of the most fascinating empirical boundaries of the present state of the semiotic art, and demands a great deal of further research.

In order to pursue this research it is absolutely necessary to demonstrate that (i) there exist different kinds of signs or of modes of sign production; (ii) many of these signs have both an inner structure and a relation to their content which is not the same as that of verbal-signs; (iii)a theory of sign production must and can define all of these different kinds of signs by having recourse to the same categorial apparatus.

Such is the aim of the following sections. I shall not attempt an exhaustive coverage of the entire field, but will instead try to define different types of signs, to analyze their constitutive differences and to insert them within the framework of the theory of sign-functions and codes. The conclusion to be drawn from this exploration will be that without doubt verbal language is the most powerful semiotic device that man has invented; but that nevertheless other devices exist, covering portions of a general semantic space that verbal language does not. So that even though this latter is the more powerful, it does not totally satisfy the effability requirement; in order to be so powerful it must often be helped along by other semiotic systems which add to its power. One can hardly conceive of a world in which certain beings communicate without verbal language, restricting themselves to gestures, objects, unshaped sounds, tunes, or tap dancing; but it is equally hard to conceive of a world in which certain beings only utter words; when considering (in 3.3.) the labor of mentioning states of the world, i.e. of referring signs to things (in which words are so intertwined with gestural pointers and objects taken as ostensive signs), one quickly realizes that in a world ruled only by words it would be impossible to mention things. In this sense a broader semiotic inquiry into various equally legitimate types of signs could also help a theory of reference, which has so frequently been supposed to deal with verbal language, as the privileged vehicle for thought alone.

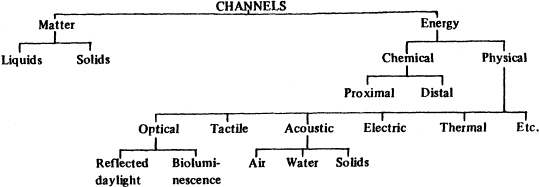

Many different classifications of the various types of signs have been put forward during the development of the philosophy of language, linguistics, speculative grammar, semiotics, etc. All of these classifications served the purposes for which they were established. I shall limit myself here to a brief outline of those that are most relevant to the purpose of the present discussion. First of all, signs may be distinguished according to their channel, or expression-continuum. This classification (Sebeok, 1972) is useful for distinguishing many zoosemiotic devices and examines the human production of signs according to the different techniques of communication involved (Table 34).

This distinction does not seem particularly useful for our present discussion, since it would seem pretty vague to place both Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and Dante’s Divina Commedia among the acoustically channelled signs, and both a road signal and Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe among the optical signs reflected by daylight.

Nevertheless it does permit one to isolate a set of important semiotic problems. There is a way in which Beethoven’s music and Dante’s poetry may be considered under the same heading. Both musical notes and words may be defined by means of sound parameters; the difference between a C emitted by a trumpet and a D emitted by a fiddle is detectable through reference to the parameters of pitch and timbre; the same happens for the difference between a velar voiced stop consonant (such as [g]) and a labial nasal one (such as [n1): in both cases, the decisive parameter is timbre. When distinguishing an interrogative utterance from an affirmative one, the essential parameters are pitch, dynamics and rhythm, as happens when distinguishing two different melodies.

On the other hand, in order to distinguish two road signals or two Manet paintings one resorts to both space and color parameters. In the first case the pertinent elements are the normal spatial dimensions, with features such as ‘up/down’, ‘right/left’, larger/smaller’ and so on; in the second one, pertinent elements are wave-lengths, frequencies or, more commonly speaking, cues. The fact that a road signal is enormously simpler than a Manet painting does not matter. Thus in detecting two tactile signals, one has recourse to certain thermal and pressure gradients, while in detecting the difference between two signs channelled through a solid matter, like two gestural signals, one relies on positional or kinesic parameters such as the direction of the gesture, its stress, and so on.

One of the most disturbing features of a lot of semiotic studies past and present has been the interpretation of various signs on the basis of the linguistic model, and thus the attempt to apply to them something metaphorically similar to the sound parameters or the model of double articulation, etc. As a matter of fact we know very little about other parameters, for instance those that govern the distinction between the olfactory signs, which are based on chemical features. Semiotics has a long way to go if it is to clarify all these problems; but even if one cannot map them entirely, one must nevertheless trace their outlines. For instance, the notion of binarism has become an embarrassing dogma only because the only binary model available was the phonological (and therefore the phonetic) one. Thus the notion of binarism has been associated with that of absolute discretedness, since in phonology the binary choice was applied to discrete entities. Both notions were associated with that of structural arrangement, so that it looked to be impossible to speak of a structural arrangement for phenomena that appeared to be continuous rather than discrete.

But ‘structure’ does not only mean opposition between the poles of a two-tuple of discrete elements. It also means opposition between an n-tuple of gradated entitites, resulting from the conventional subdivision of a given continuum, as happens with the color system. A consonant is either voiced or not, but a shade of red is not opposed to its absence; instead it is inserted within a gradated array of pertinent units cut from a wave-length continuum. Frequency phenomena do not allow the same kind of pertinentization as do timbre phenomena. As has been already said à propos of a theory of codes (see 2.8.3.), there is structure when a continuum is gradated into pertinent units and the array of these units has precise boundaries.

Moreover, nearly all the non-verbal signs usually rely on more than one parameter; a pointing finger has to be described by means of three-dimensional spatial parameters, vectorial or directional elements, and so on. So an attempt to establish a complete set of semiotic parameters will involve the entire physical conditioning of human actions, inasmuch as they are conditioned by the structure of the human body inserted within its natural and artificial environment. As will be shown in 3.6., it is only by recognizing such a range of parameters that it is possible to speak of many visual phenomena as coded signs; otherwise semiotics would be obliged to distinguish between signs which are signs (because their parameters correspond to those of verbal signs, or can be metaphorically viewed as analogous to them) and signs which are not signs at all. Which may sound paradoxical, even though it is upon such a paradox that many distinguished semiotic theories have been established.

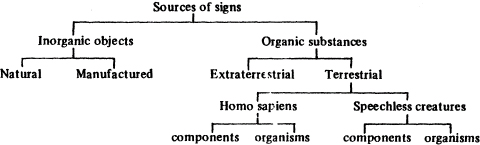

Signs are also distinguished according to whether they originate from a sender or a natural source. Insofar as there exist a lot of signs that are without a human sender, occurring as natural events but being interpreted as semiotic devices, this classification, also summarized by Sebeok (1972), can be useful for the analysis of communicational processes (Table 35).

Signs are also distinguished according to their semiotic specificity. Some signs are objects explicitly produced in order to signify, others are objects produced in order to perform a given function. These latter can only be assumed as signs in one of two ways; either they are chosen as representatives of a class of objects (see 3.6.3.) or they are recognized as forms that elicit or permit a given function precisely because their shape suggests (and therefore ‘means’, ‘signifies’) that possible function. In this second case they are used as functional objects only when, and only because, they are decoded as signs.

There is a difference (as regards sign-specificity) between the injunction /sit down!/ and the physical form of a chair which permits and induces certain functions (among others, that of sitting down); but it is equally clear that they can be viewed under the same semiotic profile.

At this point it would seem advisable to examine what is, perhaps, the most popular of Peirce’s trichotomy, that by which signs are classified as symbols (arbitrarily linked with their object), icons (similar to their object) and indices (physically connected with their object).

This distinction is so widely accepted that we have used it in the preceding pages in order to indicate certain processes, so that they could be immediately, if vaguely, grasped by everyone. It is nevertheless the basic assumption of the following pages that notions such as Icon’ or ‘index’ are all-purpose, practical devices just as are the notions of ‘sign’ or ‘thing’. They can undoubtedly be used for normal purposes, but no satisfactory definition can be found for them in the present context.

The reason is simple: such a trichotomy postulates the presence of the referent as a discriminant parameter, a situation which is not permitted by the theory of codes proposed in this book. The trichotomy could obviously be used in order to discriminate between different kinds of mentions (as indeed it was within that context), but it becomes more disturbing in a classification of modes of sign production which tries to focus exclusively upon the shaping of the signal (i.e. the expression continuum) and the correlation of that signal (as expression) with a content. Thus the following pages represent a critique of the naive notion of index and icon, and the new classification proposed in 3.6. aims to supersede these categories.

A final distinction concerns the replicability of sign vehicles. The same word can be replicated an infinite number of times, but each replica is without economic value, whereas a coin, even though a replica, has a material value of its own. Paper money has a minimal material value but receives a sort of legal value by a convention, so that it cannot be indefinitely replicated; moreover, the process of replication is so technically difficult that it requires special techniques (the reasons of that difficulty are similar to those which seemingly forbid the reproduction of Michelangelo’s Pietà; oddly enough this, too, has received a sort of conventional and ‘legal’ investiture whereby a replica, no matter how perfect, is refused as a fake). Finally a Raphael painting is commonly considered beyond replication except in cases of exceptional skillfulness – and even in these cases the replica is considered imprecise and unable to deceive a well-trained eye.(9) Thus it seems that there are three kinds of relationship between the concrete occurrence of an expression and its model: (a) signs whose tokens can be indefinitely reproduced according to their type; (b) signs whose tokens, even though produced according to a type, possess a certain quality of material uniqueness; (c) signs whose token is their type, or signs in which type and token are identical.

This distinction can be easily reduced to that proposed by Peirce’s trichotomous distinction between legisign, sinsign, and qualisign (2.243.ff.): signs of type (a) are pure sin signs; signs of type (b) are sinsigns which also are qualisigns; signs of type (c) are sinsigns which also are legisigns.

If these distinctions are considered from the point of view of the commercial value of the replica, then they are more a matter for Treasury Departments, income tax inspectors, art dealers and organized crime than for a theory of sign-functions (in which an object’s only recognized value is its quality as a functive). From the semiotic point of view, the fact that a hundred dollar bill is counterfeit does not matter: every object looking like a hundred dollar bill will stand for the equivalent amount of gold to its addressees: the fact that the bill is a fake merely means that this is a case of lying.

A perfect replica of Michelangelo’s Pietà which rendered each nuance of the material texture of the original with great fidelity would also possess its semiotic properties. Therefore the value accorded to the ‘authenticity’ of the original statue has more relevance for a theory of commodities, and when given undue importance on the aesthetic level it is a matter for social scientists or critics of social aberrations. The lust for authenticity is the ideological product of the art market’s hidden persuaders; when the replica of a sculpture is absolutely perfect, to privilege the original is like giving more importance to the first numbered copy of a poem than to a normal pocket edition. But when one considers the same problem from the point of view of sign production, other factors have to be considered. Differing modes of production of the expression, along with the necessary type/token-ratio, determine a fundamental difference in the physical nature of various types of signs.

At this point we must make a clear distinction between absolute duplicative replicas which produce a double, and partial replicas, which will simply be called replicas.

I mean by an absolutely duplicative replica a token which possesses all the properties of another token. Given a wooden cube of a given size, matter, color, weight, surface structure and so on, if I produce another cube possessing all the same properties (that is, if I shape the same continuum according to the same form) I have produced not a sign of the first cube, but simply another cube, which may at most represent the first inasmuch as every object may stand for the class of which it is a member, thus being chosen as an example (see 3.6.3.).

Obviously, as Maltese (1970:115) suggests, an absolute replica is a rather Utopian notion, for it is difficult to reconstruct all the properties of a given object right down to its most microscopic characteristics; but there is a threshold fixed by common sense which recognizes that, when a maximum number of parametric features have been preserved, a replica will be accepted as another exemplar of the same class of objects and not as an image or representation of it. Two Fiat 124 cars of the same color are not each other’s icon but two doubles.

In order to obtain a double it is obviously necessary to reproduce – to a given extent – all the properties of the model-object, maintaining their original order and interrelationships. But in order to do so it is necessary to know the rule which governed the production of the model-object. To duplicate is not to represent, to imitate (in the sense of making an image of), to suggest the same appearance; it is a matter of equal production conditions and procedures.

Suppose one has to duplicate an object devoid of any mechanical function, such as a wooden cube: one has to know (a) the modalities of production (or of identification) of the material continuum, (b) the modalities of its formation, i.e. the rules governing the relationships between its geometrical properties. Suppose now that one has to duplicate a functional object, such as a knife. One must also know its functional properties. A knife is the double of another knife if, ceteris paribus, it has the edge sharpened to the same degree. This being so, even if there were some microscopis difference in the surface texture of the handle, which could not be detected by sight, touch or a sensitive weighing machine, everybody would say that the second knife was the double of the first.

If the object is a very complex one, the principle of duplication does not change; what changes is the number of rules and the technical difficulties involved, as would be the case when trying to make the double of a Chevrolet, clearly no matter for the ‘do it yourself’ enthusiast.

An object as functionally and mechanically complex as the human body is not duplicable precisely because we are ignorant of many of its mechanical and functional rules, and first and foremost those required in order to produce living matter. Any duplication which does not follow all the rules of production and which therefore produces only a given percent of the mechanical and the functional properties of the model-object is not a double, but at best a partial replica (see 3.4.8.).

In this sense an uttered word is not the absolute duplicative replica of another word of the same lexicographic type, but rather, as we shall later see, a partial replica. If, however, I print the same word twice (for example: /dog/ . . . /dog/) I can say that one is the double of the other (microscopic differences in inking or in the pressure of the type on the paper being more a matter for metaphysical doubts about the notion of identity or equality).

According to this notion of double, it is commonly supposed that a painting is not truly duplicable. This is not completely true for, under given technical conditions, and using the same materials, one could theoretically establish a perfect double of the Mona Lisa by means of electronic scanners and of highly refined plotters. However, the perfection of such a double is determined by a perfect knowledge of even the microscopic texture of the artifact, which is usually unattainable.

Since we have defined as duplicable an object whose productive rules one knows, a painting will not usually qualify as such. What will qualify are such craft products as are traditionally duplicated without appreciable differences, so that nobody will be tempted to consider the duplicate as an iconic reproduction of the original; the duplicate is as much original as is its model. The same happens in civilizations where the representative rules are strictly standardized, so that an Egyptian painter might quite possibly have been able to duplicate a mural painting.

If Raphael’s painting seems beyond duplication, this is because he invented his rules as he painted, proposing new and imprecise sign-functions and thereby performing an act of code-making (see 3.6.7.). The difficulty in isolating productive rules is due to the fact that, while in verbal language there are recognizable and discrete signal-units, so that even a complex text may be duplicated by means of them, in a painting the signal looks ‘continuous’ or ‘dense’, without distinguishable units. Goodman (1968) remarks that the difference between representative and conventional signs resides in this opposition (dense vs. articulate) and it is to this difference that the difficulty in duplicating paintings is due. As we shall see later (3.5.) this opposition is not sufficient to distinguish the so-called “iconic” or “representative” signs, but it may be retained for the moment.

A painting does in fact possess qualisign elements; the texture of the continuum from which it is made counts for a great deal, so that a dense signal is not reducible to a distinction between pertinent recognizable elements and irrelevant variations; even minimal material variations count. It is this quality which makes a painting into an aesthetic text, as will be better explained in 3.6.7. This is undoubtedly one of the reasons why the duplication of a painting is well-nigh impossible and why its rules of production are hardly detectable.

But the other depends on the particular type/token-ratio realized by a painting. In order to make this point clear, we must now consider the case of partial replicas.

In replicas the type is different from the token. The type only dictates those essential properties that its occurrences must display in order to be judged a good replica, irrespective of any other characteristic that they may possess. Thus tokens of the same type can possess individual characteristics, provided that they respect the pertinent ones fixed by the type. It is this kind of type/token-ratio, for example, that rules the production of phonemes, words, ready-made expressions, etc. Phonology establishes certain phonetic properties that a token phoneme must have in order to be recognized as such; everything else is a matter of free variation. Regional or idiosyncratic differences in pronunciation do not matter, provided they do not affect the recognizability of the pertinent properties.

The type/token-ratio obeys different parameters and rules of fidelity according to different sign systems. Maltese (1970) lists ten kinds of ratio, from the absolute duplicate (which, given six properties of the visual-tactile experience of a given object, reproduces all of them) down to the reproduction of a unique property, as happens in a symbolic and schematic representation on a plane surface. This list coincides in some respects with the various ‘scales of iconicity’ (such as that proposed by Moles) and problems connected with these scales will be considered in 3.6.7.; but at present we are concerned with the three first degrees of Maltese’s scale: between the first (6/6), second (5/6) and third (4/6) one could easily classify the various kinds of type/token-ratio operating within the relationship between an expression and its type. For instance a road signal commanding “stop” is a 6/6 reproduction of its type; it is the absolute duplicative replica of many other signs of the same class. As an object, it is simply a double, but inasmuch as it is a sign it is one in which the fidelity of token to type must be absolute; the type prescribes form, size, painted lines and colors, material smoothness of surface, weight, etc. without permitting free variations. Free variations might well allow one to recognize the sign as such, but would induce a sharp observer (such as a policeman) to suspect a fake.