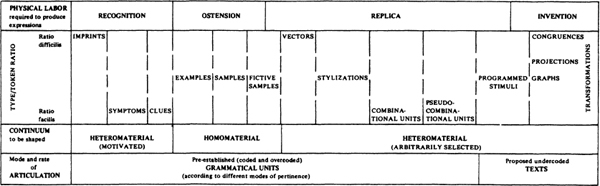

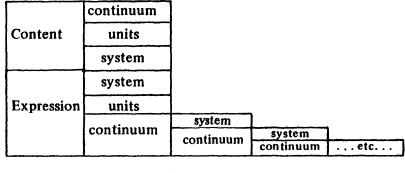

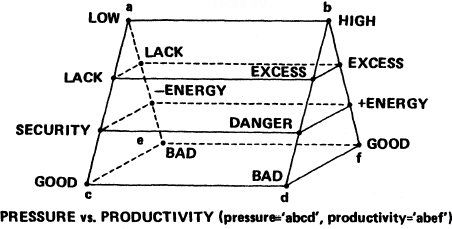

The classification of modes of production outlined in Table 39 takes into account four parameters:

(i) the physical labor needed to produce expressions (ranging from the simple recognition of a pre-existent object or event as a sign to the invention of previously non-existent and un-coded expressions);

(ii) the type/token-ratio, whether facilis or difficilis (see 3.4.9.);

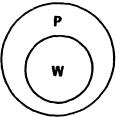

(iii) the type of continuum to be shaped; this continuum can be either homomaterial or heteromaterial; a continuum being homomaterial when the expression is shaped within and by the same material stuff as that with which the possible referent of the sign-function could be made (in cases where signs are used to mention things). All other cases imply a heteromaterial continuum which is arbitrarily selected (except in a few cases in which the matter of the expression is imposed by the direct action of the referent; for instance imprints are impressed upon a given material by the imprinter);

(iv) the mode and complexity of articulation, ranging from systems in which there are precise combinational units that are duly coded or overcoded to those in which there are texts whose possible compositional units have not yet been further analyzed.

A Typology 01 Modesof Sign Production

The table records the way in which expressions are physically produced and not the way in which they are semiotically correlated to their content; the latter is implied by two decisions that must be made either before or after the production of the expression.

For instance, in the case of recognition of symptoms, there is undoubtedly a pre-established motivation due to a preceding experience which has demonstrated that there is a constant physical relationship between a given agent and a given result; it has therefore been decided, by convention, that these resultant objects must be correlated with the notion of that agent under any circumstances, even when one cannot be sure that an existing agent has really produced the result. In the case of words (which may be classed among ‘systematically combinable units’) the correlation is posited after the production of the physical unit and is in any case independent of its form (this assumption being valid even if by unverifiable historical chance the origin of words had some sort of imitative motivation).

For this reason such non-homogeneous objects as a symptom and a word are posited in the same row; every object listed there can be produced according to its pre-existing expression-type (ratio facilis) and this happens irrespective of the reasons for which these objects were selected as the expression of a given content. All of them could be produced by a suitably instructed machine which only ‘knows’ expressions, while another machine could assign to each expression a given content, provided it was instructed to correlate functives (in other words, two expressions can be differently motivated but can function in equally conventional fashion).

On the other hand, all objects ruled by a ratio difficilis are so motivated by the semantic format of their content (see 3.4.9.) that it is irrelevant whether they have been correlated with it on the basis of previous experience (as in the case of footprints, where the semantic analysis of the content has already been performed) or whether the content is the result of the experience of ‘inventing’ the expression (as in the case of paintings). Therefore the motivated way in which they have been chosen (see the further analysis of imprints and projections below) does not affect their mode of production according to a ratio difficilis; they are correlated to certain aspects of their sememes – thereby becoming expressions whose features are also content-features, and thus projected semantic markers (20).

In this sense a machine instructed to produce these objects should be considered to have also received semantic instructions. One might say that since it is instructed to produce expressions, it is being fed with schematic semantic representations (21).

The items recorded in the row corresponding to the parameter ‘type/ token-ratio’ may look like ‘signs’, since to some degree they recall preexisting sign typologies. But they are not; they are short-hand formulas that should be re-translated so as ‘to produce imprints’, ‘to impose a vectorial movement’ or ‘to replicate combinable units’ and so on.

‘imprints’ or ‘examples’ must, at most, be understood as physical objects which, because of certain of their characteristics (not only the way in which they are made, but also the way in which they are singled out) become open to a significant correlation, i.e. ready to be invested with dignity of functive. In other words they are potential expression features or bundles of features. According to the system into which they are inserted, they may or may not be able to convey by themselves a portion of content. So that although they can also act as signs, they will not necessarily do so. It must be clear that the whole of Table 39 speaks of physical procedures and entities that are ordered to the sign-function but that could subsist even if there were no code to correlate them to a content. On the other hand, they are produced in order to signify and the way in which they are produced renders them able to signify in a given way.

A ready-made expression like /cherry brandy/ is the result of two procedures depending on a double type/token-ratio; it is constructed from two combinational units ordered by a vectorial succession; likewise a pointing finger is both a vector and a combinational unit, while a road arrow is both a stylization and a vector. Therefore items like ‘vectors’ or ‘projections’ are not types of signs and cannot be equated with typological categories such as ‘indices’ or ‘icons’. For instance both ‘projections’ and ‘imprints’ could appear to be icons but the former would imply an arbitrarily selected expression-continuum and the latter a motivatedly established one, while both of them (equally governed by a ratio difficilis) would be motivated by a content-type (though imprints are ‘recognized’, while projections are ‘invented’).

Imprints and vectors look like indices, but are in fact dependent on two different type/token-ratios. Moreover, certain categories (e.g. ‘Active samples’) come under two headings: they are the result of a double labor, since something must be replicated in order to be shown (ostension).

All these problems will be dealt with further in the following paragraphs. I have only anticipated some examples in order to stress the fact that one must not look at Table 39 in order to find types of signs. This table only lists types of productive activity that can give rise, by reciprocal and complex interrelations, to different sign-functions, whether they are coded units or coding texts.

Recognition occurs when a given object or event, produced by nature or human action (intentionally or unintentionally), and existing in a world of facts as a fact among facts, comes to be viewed by an addressee as the expression of a given content, either through a pre-existing and coded correlation or through the positing of a possible correlation by its addressee.

In order to be considered as the functive of a sign-function the object or event must be considered as if it had been produced by ostension, replica or invention and correlated by a given kind of type/token-ratio. Thus the act of recognition may re-constitute the object or event as an imprint, a symptom or a clue. To interpret these objects or events means to correlate them to a possible physical causality functioning as their content, it having being conventionally established that the physical cause acts as an unconscious producer of signs. As we will see, the inferred cause, proposed by means of abduction, is pure content. The object can be a fake or can be erroneously interpreted as an imprint, a symptom or a clue, when in fact it is the chance product of other physical agents: in such a case the ‘recognized’ object expresses a content although the referent does not exist.

In the recognition of imprints, the expression is ready-made. The content is the class of all possible imprinters. The type/token-ratio is difficilis. The form of the expression is motivated by the form of the supposed content and has the same visual and tactile markers as the corresponsing sememe, even though the marks of the sememe can be ‘represented’ by the imprint in various ways. For example the size of the imprinter determines (or motivates) the size of the imprint, but there is a similitude rule establishing that the size of the latter is always larger than the size of the former (even if infinitesimally). The weight of the imprinter determines the depth of the imprint, but this process is governed by a proportional rule (that is, an analogy in the strict sense outlined in 3.5.4.). With fingerprints, size is not a pertinent parameter since they can be correlated to their content even if enormously magnified.

These observations may help to clarify in what sense one could say that an imprint represents both a metaphorical and a metonymical operation. In fact imprints appear to be ‘similar’ to the imprinting agent and substitute for or represent it; and they can be taken as a proof of past ‘contiguity’ with the agent.

This explanation may work (and may indeed be used to distinguish imprints from clues and symptoms, see below) provided one accepts that the similarity of imprints to their possible cause is not immediately detectable, since certain transformational operations must be understood to have taken place, and that past contiguity with the referent is the result of a labor of presupposition performed when the sign is viewed as focusing on the world and interpreted as a mention (see Table 31).

All this means that, first of all, one must learn to recognize imprints (or to fake them). Imprints are usually coded; a hunter learns how to recognize the imprint of a hare without mistaking it for a rabbit’s. Insofar as they are coded, they rely on oppositional expressive systems; roughly speaking, one is dealing with oppositions such as ‘hare vs. rabbit’, though in fact these oppositions should be the product of a more finely analyzable system of pertinent spatial features. Semiotics has not yet done sufficient work on such expressive systems, but one of its provisional boundaries would be that of ‘imprints’ being not signs but rather objects to be inserted into a sign-function; in fact the trace of an animal, viewed as a sign-function, does not only imply spatial or tactile parameters (size or weight) but also vectorial cues (see 3.6.5.).

A trace is also interpreted in terms of its direction. This direction is another productive cue that can be falsified; one can shoe a horse backward so as to give the impression that the horse was going in the opposite direction. When interpreted as an imprint and as a vector, a given trace is correlated not so much with a coded unit (cat, horse, hare, SS soldier and so on) as with a discourse (a horse passed by three days ago going in that direction). Therefore the expression is no longer a sign but rather a text (22).

The correlational dynamics of imprints could be better explained when speaking of projections (3.6.9.) and in fact they are recognized as if they were projected on purpose. As projections, imprints can also be complex texts, in the sense that they can be imprints of very complex events; and in this way they cannot longer be considered as coded units.

But in the present section I am considering coded imprints, corresponding to a coded content; in this sense they are pertinent macro-units in some way analyzable into pertinent elementary features.

Anyway imprints are doubly motivated: once by the form of their content, and once by the presupposed relationship to their cause; therefore an imprint is a heteromaterial object (a cat’s paw mark in the mud is not materially the same as its possible cause) but its matter is strictly motivated by its cause.

Imprints (like any other recognition procedure) are conventionally coded, but the code is not established by an arbitrary social decision but is instead motivated by previous experiences; the correlation between a given form and a given content has been mediated by a series of mentions, inferences based upon uncoded circumstances, meta-semiotic statements (23). Since the experience of an event was constantly associated with a given imprinted form, the correlation, first proposed as the result of an inference, was then posited.

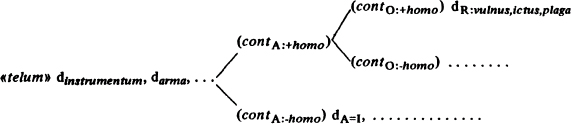

In the recognition of symptoms, the expression is ready-made. The content is the class of all possible causes (organic alterations). The type/token-ratio is facilis, for red spots do not have the same semantic markers as measles, nor does smoke have the same as fire. Nevertheless within the sememic representation of their content there is, among the markers, both the description and the representation of the symptoms.

This explains the way in which a symptom is correlated to the notion of its cause; the notion of the symptom constitutes part of the sememe of the cause and it is thus possible to establish a metonymical correlation between the functives (by a pars toto procedure). The process is notion-to-notion (or unit-to-unit) and the effective presence of the referent is not required. There can be smoke even if there is no fire at all, which means that symptoms can be falsified without losing their significant power. The ratio being facilis, it would be incorrect to speak of a certain ‘iconicity’ of symptoms; they have nothing to do with their content (or referents) in terms of similarity. When symptoms are not previously coded, their interpretation is a matter of complex inference and leads to the possibility of code-making.

Symptoms can be used for mentioning (smoke means «there is fire», red spots on the face mean «this child has measles»). In this case the mentioning procedure works as follows: by a coded and proved causality (contiguity) of the type ‘effect to cause’, an effective presence of the causing whole is deduced.

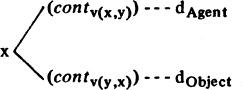

In the recognition of clues, one isolates certain objects (or any other kinds of trace which are not imprints) left by someone on the spot where he did something, so that by their actual presence the past presence of the agent can be inferred. It is evident that, when used for mentioning, clues work in exactly the opposite way from symptoms; by a coded and proved contiguity (of the type ‘owned to owner’) a possible presence of the causing agent is abduced. In order that the abduction be performed, the object must be conventionally recognized as belonging to (or being owned by) a precise class of agents. Thus if at the scene of a murder I find a dental plate I may presume that, if not the murderer, at any rate someone who has no more natural teeth has been there. If on the floor of a political party’s office, recently broken into, I find the badge of the rival organization, I may presume that the burglars were the ‘bad guys’ (obviously clues can also be falsified, and in cases like this they usually are).

As a matter of fact clues are seldom coded, and their interpretation is frequently a matter of complex inference rather than of sign-function recognition, which makes criminal novels more interesting than the detection of pneumonia.

One could say that imprints and clues, even though coded, are ‘proper names’, for they refer back to a given agent. The objection does not affect the fact that they refer, in any case, to a content, for there is nothing to stop the class to which the expression refers from being a one-member class (see 2.9.2.).

But in fact very seldom can imprints and clues be interpreted as the traces of an individual agent (indeed maybe never). When looking at the footprint on the island, Robinson Crusoe was not able to think about an individual. He detected «human being». When discovering Friday he was undoubtedly able to express the index-sensitive proposition «this is the man who probably left the footprint». But even if he had previously known that there was one and only one man on the island he would not, when looking at the footprint, have been able to refer it to a precise individual; the primary denotation of the expression would have been «human being» and the rest would have had to be a matter of inference. It is very difficult to imagine an imprint that mentions a referent without the mediation of a content (24). The only case would be that in which one sees a given individual in the act of producing a footprint; but in this case the footprint would not be ‘recognized’ as a sign, for it would not be ‘instead of’ something else, but ‘along with’ it (see the case of mirrors in 3.5.5.) (25). The same happens with clues. Even if I know that only one particular man, among the murdered person’s circle of friends, has a dental plate, I cannot regard the object left at the scene of the crime as a sign referring back to a «person x». The object simply means «person without teeth», and the rest is once again a matter of inference.

On the contrary many clues are overcoded objects. Suppose that I find a pipe in the same place. What makes me sure that a man was there? A social rule establishing that gentlemen smoke pipes and ladies don’t (the opposite would happen if I found a bottle of Chanel No. 5).

Ostension occurs when a given object or event produced by nature or human action (intentionally or unintentionally and existing in a world of facts as a fact among facts) is ‘picked up’ by someone and shown as the expression of the class of which it is a member.

Ostension represents the most elementary act of active signification and it is the one used in the first instance by two people who do not share the same language; sometimes the object is connected to a pointer, at others it is regularly picked up and shown; in both cases the object is disregarded as a token and becomes, instead of the immediate possible referent of a mention, the expression of a more general content.

Many things have been said about signification by ostension (see for instance Wittgenstein, 1945:29-30) and a purely ostensive language has been invented by Swift. Let me only remark here that in ostension there is always an implicit or explicit stipulation of pertinence. For example, if I show a packet of brand X cigarettes to a friend who is going shopping, this ostension can mean two different things: either «please buy some cigarettes» or «please buy this brand of cigarettes». Maybe in this latter case I would have to add certain indexical devices, such as tapping with the finger on the part of the packet which bears the name of the brand, and so on. Likewise, in other circumstances only a previous stipulation of pertinence makes clear whether, when showing a packet of cigarettes, I mean «packet of cigarettes» or simply «cigarettes».

At other times ostension may suggest an entire discourse, as when I show my shoes to someone not in order to say «shoes», but rather «my shoes are dirty» or «please shine my shoes». In these latter cases the object is not only taken as a sign but also as a referent and the indication constitutes an act of mentioning. As a matter of fact it is as if I were saying «shoes (ostension) + these (mention) + shoes (referent)».

This theory solves the problem of ‘intrinsically coded acts or object’ (see 3.5.8.) without implying that a part or all of the referent will constitute a part of the definition of the sign-function; the shoes are first of all viewed as an expression which is made with same stuff as its possible referent. Therefore ostensive signs (depending on choice) are homomaterial.

In principle ostensive production should be considered as governed by a ratio difficilis, for the shape of the expression is determined by the shape prescribed by the sememic composition of the content; yet in fact they constitute expressions whose form is already established by a sort of repertoire, and therefore they should be considered as governed by ratio facilis. For this reason I have classified them half way between both ratios. In practice they are already produced (as functional objects) and the problem of their type/token-ratio vanishes; but theoretically speaking (and considering them as if they had to be produced) they constitute a particular category of sign-functions in which both the ratios coincide.

Another characteristic of expressions produced by ostension is that they can be taken in two ways: as the conventional expression of a cultural unit (a cigarette means «cigarettes») or as the intensional description of the properties recorded by the corresponding sememe. So I can show a cigarette in order to describe the properties of a cigarette (it is a cylindrical body, several inches long, white etc.). This is the only case in which doubles can be used as signs.

So, as with doubles, in ostension the type/token-ratio becomes a token/token-ratio. Theoretically speaking, type and token coincide, which explains why ratio facilis and ratio difficilis also coincide.

All these observations might well lead to the conclusion that – in expressions produced by ostension – to distinguish expression from referent is a rather Byzantine exercise, which is by no means the case. Suppose that a crowd of men, each of whom has received a piece of bread, hold up these pieces (different in shape and size) shouting /more!/. The differences between referents disappear and only major pertinent features are virtually retained; the crowd is saying «we want more bread» (irrespective of its shape and maybe of its exact quantity). Inasmuch as it is shown, the bread works as a sign, and it is ‘made’ more elementary than it really is, becoming conventionally and virtually deprived of many of its physically detectable properties.

When an object is selected as a whole to express its class, this constitutes a choice of example. The mechanism governing the choice and the signifying correlation are based on a synecdoche of the kind ‘member for its class’. When only part of an object is selected to express the entire object (and thereby its class) this constitutes a choice of sample. The mechanism governing the choice and the signifying correlation is based on a synecdoche of the kind ‘part for the whole (of a member of a class)’. Instances of this case are those in which a tailor shows a small portion of a fabric in order to refer to the entire cut or indeed directly to the jacket (or shirt) made with this fabric, or a musical quotation referring to a whole work (/play me ‘ta-ta-ta-taaa’/ may mean «play me Beethoven’s Fifth»). On the other hand, an instance of ‘metonymical’ sample may be given by a lancet’s meaning «surgeon».

As Goodman (1968) remarks in an interesting discussion on samples, a sample can be taken as the sample of “samples”. Goodman also remarks that a polysyllabic word can be taken as the example of the general class of polysyllabic words. Since it is the case of a double, chosen or produced in order to exemplify not the physical properties of that token but the semantic properties of a metalinguistic sememe (see note 25), a preceding or presupposed discourse is always needed in order to stipulate the pertinence level. Without this previous convention, the ostension of the word /polysyllabic/ would be taken as the description of the properties of the expression /polysyllabic/ and not of every polysyllabic word, such as for instance /monosyllabic/.

Looking at Table 39, one may note that there is one sort of sample that is listed both under the heading of ostension and under that of replica. These are fictive samples, i.e., the sign-functions that Ekman and Friesen (1969) have called ‘intrinsically coded acts’ (see 3.5.8.).

If I pretend to hit someone with a fist, the meaning of the whole act is «I punch you». One could say that this was a regular ostension for I have chosen a token gesture in order to represent its class. As a matter of fact I have not so much ‘picked up’ an existing gesture as ‘re-made’ it, and in remaking it I have disregarded certain properties of the gesture (for instance, I do not really punch my interlocutor, and I therefore stop the trajectory of the gesture a little before its fullfilment). Thus I have replicated part of a gesture as a sample of the entire gesture. Thus so-called intrinsically coded acts are at once both ostension and replicas. Mimicry belongs to this category, as do ‘full’ onomatopoeias (that is, ‘realistic’ reproductions of a given sound by a human voice or other instrument, as opposed to onomatopoeic stylizations, such as /thunder/) (26).

Fictive samples are also homomaterial, because the replica is performed using the same stuff as that of the partially reproduced model. Therefore to call these full onomatopoeias ‘iconic’, in the same way that one calls the image of an object iconic, is to categorize them imprecisely, since images must be classified among projections (see 3.6.7.) where the expression-continuum is different from the stuff of the possible referent and the correspondence is fixed by transformational rules. A fictive sample does not need transformational rules since it is a homomaterial replica (a partial double) and as such has the advantage of being governed by a ratio facilis, while images are governed by a ratio difficilis. That a so-called intrinsically coded act is a matter of convention can be demonstrated by the fact that, in order to work as a sign-function, it required a previous stipulation (27).

This mode of production governs the most usual elements of expression, so that, when defining the notion of sign, one takes into account only replicable objects intentionally produced in order to signify. Thus the best known kinds of replicas are phonemes and morphemes; expression-units constructed according to a ratio facilis, using a continuum completely alien to their possible referents, and arbitrarily correlated to one or more content-units.

But this unit-to-unit correlation is not typical of replicas alone. Recognition and ostension likewise isolate units and symptoms, imprints, clues, examples, samples and fictive samples are coded by a unit-to-unit correlation. There are conventions by which a certain trace means «hare», a certain medical symptom means a given sickness, and an object taken as an example means a precise category. It is true that a footprint can ‘say’ more than «man», as we have seen, and that a packet of cigarettes may also mean «buy me some cigarettes», but then it is equally true that the word /cigarette/ may, under certain circumstances, stand for an entire discourse. This means that all the sign-functions depending on replica, ostension and recognition articulate given units in order to produce more complex texts.

Granted that this is so, one may go on to list under the heading of replicas not only verbal devices, but also ideograms, emblems (like flags), alphabetic letters, various coded kinesic features (for instance gestures meaning «come here», «yes», «no» and so on), musical notes, various traffic signals («stop», «walk», «no turn»), elementary graphic features, symbols in formal logic and mathematics, proxemic features and so on.

It is true that a word can be analyzed into more elementary, non-significant units (phonemes) and phonemes into more elementary, non-articulatory features, while an ideogram or an emblem must be taken as an unanalyzable unit. But this only means that replicable expressions work on different pertinence levels and may be subject to two, one, or no articulation.

During the sixties, semiotics was dominated by a dangerous verbocentric dogmatism whereby the dignity of ‘language’ was only conferred on systems ruled by a double articulation. A typical example of this fallacy is Lévi-Strauss’s discussion on the ‘linguistic’ properties of paintings, tonal music and post-Webernian music.

In verbal language there exist elements of first articulation, endowed with meaning (morphemes), which combine to form broader syntagmatic strings; these elements can subsequently be analyzed into elements of second articulation (phonemes). There is no doubt that meaning in language arises through the interplay of these two types of elements; but this does not mean that every semiotic process must come about in the same way. Instead Lévi-Strauss maintains that language cannot exist unless these conditions are fulfilled.

In his Entretiens (1961) with a radio interviewer, he had already developed a theory of visual works of art which outlined this viewpoint and he developed it more fully in the “Ouverture” to The Raw and the Cooked. In the former case he referred to a theory of art as iconic sign which he had elaborated in The Savage Mind, where he spoke of art as “a reduced model” of reality. Art is considered as the capture of nature by culture; it raises the brute object to the level of sign, and reveals in it a previously latent structure. But art signifies by means of a certain relationship between its sign and the object which inspired it; thus if it were not an arbitrary and a conventional phenomenon of a linguistic order it would no longer have the character of sign. If in art an appreciable relationship between signs and objects subsists, this is certainly due to the fact that, in one way or another, it presents the same types of articulation as verbal language.

Like verbal language, painting is supposed to articulate units which are endowed with meaning and which can be considered equivalent to morphemes (and here Lévi-Strauss clearly refers to identifiable images, and therefore to iconic signs); these units can be analyzed into minor articulatory elements (forms and colors) which only have oppositional value and are devoid of any autonomous meaning. According to Lévi-Strauss the ‘non-figurative’ schools forgo the primary level “and claim that the secondary level is sufficient”. They fall into the same trap as atonal music, they lose all ability to communicate and slip into “the heresy of the century”, the claim of “wanting to build a sign system on a single level of articulation”.

Lévi-Strauss’s text, which elaborates perceptive observations on the problems of tonal music (in which he recognizes, for example, elements of second articulation) is in point of fact based on a series of unfortunately dogmatic assumptions, namely that: 1) there is no language without double articulation; 2) double articulation is not mobile, the levels cannot be substituted or interchanged, their structure is based on deep natural structures of the human mind. But if one instead examines the functioning of various sign systems, one realizes that: (a) there are systems with various types of articulation or none at all; (b) there are systems whose level of articulation is changeable.

Obviously one may suppose that there probably does exist a profound articulatory matrix which governs every sign-system and all its possible articulatory transformations, but this matrix must not be identified with one of its surface manifestations. This is precisely what Lévi-Strauss does when, for instance, he attributes a privileged status to the tonal system in music, forgetting that tonal system was born at a given historical moment and that the Western ear has grown accustomed to it. Lévi-Strauss rejects the atonal system (as well as the whole of non-figurative painting) for not being governed by a detectable double articulation, thus proposing the tonal system in music and figurative procedures in painting as basic and natural metalanguages, exclusively entitled to define (or reject) every other musical or visual ‘language’.

To confuse the laws of tonal music with the laws of music tout court is rather like believing that if one has a pack of French playing cards (52 plus one or two jokers), the only possible combinations among them are those established by bridge. Whereas on the contrary, bridge is a sub-system which makes possible an endless number of different games, but which could be replaced, still using the same cards, by poker, another sub-system which restructures the articulatory elements constituted by individual cards, enabling them to assume different combinational values and to form other significant arrangements (pair, three of a kind, flush, etc.). Clearly a given game (be it poker, rummy or bridge) isolates only some possible combinations among those permitted by the cards, but it would be a mistake to believe that any one of these combinations is the basic one.

It is true that the 52 (or 54) cards provide a choice which operates within the continuum of possible positional values – as do the notes of the tempered scale – but clearly various sub-systems can be constructed within this system; equally, there are card games which choose different numbers of cards – the 40 cards of the Neapolitan pack, the 32 cards of German skat. The real system which presides over card games is a combinational matrix which can be studied by games theory; and it would be useful if musical science were to study the combinational matrices which permit the existence of diverse systems of attraction; but Lévi-Strauss identifies cards with bridge, confuses an event with the structure which makes multiple events possible.

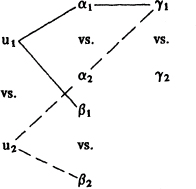

Playing cards bring us face to face with a problem which is very important for our investigation. Does the system of playing cards have two articulations? If poker vocabulary is made possible by the attribution of meanings to a particular articulation of several cards (three aces of different suits, equal to «three of a kind»; four aces equal to «four of a kind») we should consider the combinations of cards as significant strings of first articulation while the cards which form the combinations are elements of second articulation.

Nevertheless the cards are not distinguished merely by the position they assume in the system, but by a twofold position. They are opposed as different values within a hierarchic sequence of the same suit (ace, two, three . . . ten, jack, queen, king) and they are opposed as hierarchic values belonging to four sequences of different suits. Therefore two tens combine to form a «pair»; a ten, a jack, a queen, a king and an ace combine to form a «sequence»; but only the cards of the same suit can combine to form a «suit» or a «royal flush».

Therefore some values are pertinent features as far as certain significant combinations are concerned, and others are so as far as certain others are concerned. But is the single card the ultimate term of any possible state of articulation, thus resisting further analysis? If the seven of hearts constitutes a positional value in respect to the six (of any suit) and in respect to the seven of clubs, what is the single heart if not the element of an ulterior and more analytic articulation?

The first possible answer is that the player (who ‘speaks’ the language of the cards) is not in fact called upon to articulate the unit of suit, because he finds it already articulated in values (ace, two . . . nine, ten); but this point of view, though it may appear logical to the poker player, is already questionable to a player of other games (like the Italian ‘scopa’) in which the points (the units) are added up, and in which therefore the pertinent unit is that of suit (even if the additions have preformed addendae).

All these considerations force one to recognize that it is wrong to believe: 1) that every sign system act is based on a ‘language’ similar to the verbal one; 2) that every ‘language’ should have two fixed articulations. One should on the contrary assume that: (i) semiotic systems do not necessarily have two articulations; (ii) the articulations are not necessarily fixed.

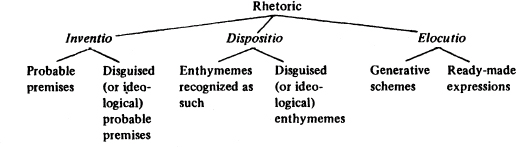

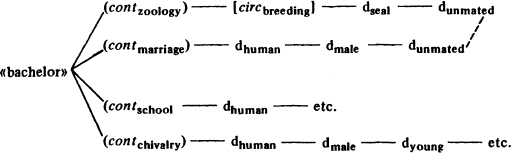

Let us here list a series of different articulatory possibilities, following the proposal set out by Prieto (1966). It will be seen that there exist systems with two articulations, systems with only the first articulation, systems with only the second articulation and systems without articulation. Let us recall that (i) the elements of second articulation (called figurae by Hjelmslev) are purely differential units which do not represent a portion of the meaning conveyed by the elements of first articulation; (ii) the elements of first articulation, commonly called ‘signs’, are strings composed by elements of second articulation and convey a meaning of which the elements of second articulation are not a portion; (iii) there are signs whose content is not a content-unit but an entire proposition; this phenomenon does not occur in verbal language but it does occur in many other semiotic systems; granted that they have the same function as verbal sentences, we shall call these non-verbal sentences ‘super-signs’. In many semiotic systems these super-signs must be considered as strictly coded expression-units susceptible of further combination in order to produce more complex texts (Prieto, following Buyssens, calls these super-signs /sèmes/, but I prefer to avoid such a term, which may be confused with the term /seme/ or /sème/ employed in compositional analysis and standing for «semantic marker», therefore possessing a quite different meaning).

A typical example of super-sign is an ‘iconic’ statement such as a man’s photograph which not only means «person x» but «so and so, smiling, wearing glasses, etc.» (which could be a mere description) or «so and so is walking», which clearly corresponds to a verbal sentence.

Thus following Prieto’s suggestion, let us try to list various types of semiotic systems with various types of articulation:

A. systems without articulation: provide for super-signs which cannot be further analyzed in compositional elements:

1) systems with a single super-sign (for example the blind man’s white cane; its presence indicates «I am blind»; whereas its absence does not necessarily mean the opposite, as might be the case, however, for systems with zero sign-vehicle);

2) systems with zero sign-vehicle (the admiral’s flag on a ship; its presence indicates «admiral on board» and its absence «admiral off board»; the directional signals of an automobile, whose absence means «I am proceeding straight ahead»);

3) traffic lights (each unit indicates an operation to carry out; the units cannot be articulated among themselves to form a text, nor can they be further analyzed into underlying articulatory units);

4) bus lines labelled by single numbers or letters of the alphabet.

B. Codes with second articulation only: the units are super-signs. These cannot be analyzed into signs but only into figurae (which do not represent portions of the content of the main units):

1) bus lines with two numbers: for example line /63/ indicates that it «runs from place X to place Y»; the unit can be segmented in the figurae /6/ and /3/, which do not have any meaning;

2) naval ‘arm’ signals: various figurae are allowed for, represented by various inclinations of the right and left arm; two figurae combine to form a letter of the alphabet; this letter is not usually a sign because it is without meaning. It acquires the latter only if it is considered as an articulatory element of verbal language and is articulated according to its laws; however, it can acquire a conventional value within the naval code, indicating for instance «we need a doctor» and must then be considered as a super-sign.

C. Codes with first articulation only: the main units can be analyzed into signs but not thereafter into figurae:

1) the numeration of hotel rooms: the unit /20/ usually indicates «first room, second floor»; it can be subdivided into the sign /2/, which means «second floor» and into the sign /0/, which means «first room»;

2) street signals with units analyzable into signs: a white circle with a red border which contains the black outline of a bicycle means «cyclists not allowed» and can be broken down into the expression //red border//, which means «not allowed» and the image of the bicycle, which means «cyclists».

D. Codes with two articulations: super-signs can be analyzed into signs and figurae:

1) verbal languages: phonemes are articulated into morphemes and these in turn into broader syntagms;

2) telephone numbers with six digits: some can be broken down into groups of two digits, each of which indicates (according to position) a section of the city, a street, an individual; whereas each sign of two digits can be broken down into two figurae which have no meaning.

E. Codes with mobile articulation: in some codes there can be both signs and figurae but not always with the same function; the signs can become figurae or vice versa, the figurae super-signs, other phenomena can assume the value of figurae, etc.:

1) tonal music: the notes of the scale are figurae which are articulated into signs (partially significant configurations) such as intervals and chords; these are further articulated into musical syntagms. A given melodic succession is recognizable no matter what instrument (and therefore what timbre) it is played on; but if one changes the timbre for every note of the melody in a conspicuous fashion, one no longer hears the melody but merely a succession of timbres; and so the note is no longer a pertinent feature and becomes a free variant while the timbre becomes pertinent. In other circumstances the timbre, instead of being a figura, can become a sign bearing cultural connotations (such as a rustic bagpipe-pastoral) (cf. Schaeffer, 1966);

2) playing cards: here we have elements of second articulation (the units of the suits, such as hearts or clubs) which combine to form signs endowed with meaning in relation to the game (the seven of hearts, the ace of spades). These may combine into ‘card-sentences’ such as «full» or «royal flush». Within these limits a card game would be a code relying upon an expression-system with two articulations; but it must be noted that there exist in this system (a) some signs without second articulation, e.g. ‘iconological’ super-signs such as “King” or “Queen”; (b) iconological super-signs which cannot be combined into sentences together with other signs, such as the joker or, in certain games the Jack of Spades. Moreover the figurae can, in turn, be distinguished by both shape and color, and can be selected according to various pertinent criteria from game to game; thus in a game in which hearts are of greater value than spades, the figurae are no longer without meaning, but can be understood as signs. And so on: within the card system it is possible to introduce the most varied conventions of play (even those of fortune-telling) through which the hierarchy of articulations can change.

F. Codes with three articulations: according to Prieto it is difficult to imagine such a type of code for, in order to have a third articulation unit, one needs a sort of hyper-unit (the etymology is the same of ‘hyperspace’) composed of ‘signs’ of the more analytical articulation so that its analytical components are not parts of the content that the hyper-unit conveys (in the same way in which figurae are analytical components of signs but the former are not conveying a part of the meaning of the latter). It seems to me that the only instance of third articulation can be found in cinematographic language. Suppose (even if it is not that simple) that in a cinematographic frame there are visual non-significant light phenomena (figurae) whose combination produces visual significant phenomena (let us call them ‘images’ or ‘icons’ or ‘super-signs’). And suppose that this mutual relationship relies on a double articulation mechanism.

But in passing from the frame to the shot, characters perform gestures and images give rise, through a temporal movement, to kinesic signs that can be broken into discrete kinesic figurae, which are not portions of their content (in the sense that small units of movement, deprived of any meaning, can make up diverse meaningful gestures). In everyday life it is rather difficult to isolate such discrete moments of a gestural continuum: but this does not hold true for the camera.

Let me stress the fact that kinesic figurae are indeed significant from the point of view of an ‘iconic’ language (i.e. they are significant when considered as photographs) but are not significant at all from the point of view of a kinesic language! Suppose that I subdivide two typical head gestures (the sign for /yes/ and the sign for /no/) into a large number of frames: I would find a large number of diverse positions which I would not be able to identify as components of one particular gesture. The position //head tilted toward the right// might be either the figura of the sign //yes// coupled with the pointer //indication of the person on the right// or the figura of a sign //no// coupled with //lowered head// (a gesture that may convey various connotations). Thus the camera offers kinesic figurae devoid of content, which can be isolated within the spatial limits of the frame (see Eco, 1968, B.3.I.).

All these alternatives are suggested simply to indicate how difficult it is to fix, in the abstract, the level of articulation of some systems The important thing is avoid trying to identify a fixed number of articulations in fixed interrelationship. According to the point of view from which it is considered, an element of first articulation can become an element of second articulation and vice versa.

After establishing that systems have various types of articulation and that therefore there is no reason to bow to the linguistic model, we must also remember that a system is often articulated by setting up as pertinent features those elements which are the syntagms of a more analytic system; or that, on the contrary, a system considers as syntagms (the ultimate limit of its combinational possibilities) those elements which are the pertinent features of a more synthetic system. A similar possibility was observed in the example of sailors’ arm signals.

Language considers phonemes to be its ultimate articulatory elements, but the code of naval flags involves figurae that, in relation to phonemes, are more analytic (position of the right arm and position of the left arm), these combining to provide syntagmatic configurations (ultimate in relation to that code) which correspond, practically speaking (even though they transcribe letters of the alphabet and not phonemes) to the figurae of the verbal language.

However, a system of narrative functions contemplates large-scale syntagmatic chains (or the kind /hero leaves his house and meets an enemy/) which, for the purposes of the narrative system, are pertinent features, while for the purposes of the linguistic one they are syntagms. Thus a code decides on what level of complexity it will single out its own pertinent features, entrusting the eventual internal (analytic) codification of these features to another code. If one takes the narrative unit /hero leaves home and meets an enemy/ the narrative code isolates it as a complex content-unit and does not concern itself about the language in which it can be expressed and the stylistic and rhetorical devices which contribute to its construction.

All these are examples of successive overcoding. Usually in overcoding the minimal combinational units are the maximal combined chains of a preceding basic code. But sometimes there also is overcoding when the minimal combinable units or the minimal analyzable clusters of a given code are submitted to a further analytical pertinentization.

See for instance the various experiments in which a scanner is used to decompose and analyze an image into distinctive features, convey them to the computer by means of binary signals, and reproduce them in output through a plotter that draws very complex rasters capable of defining any type of image (their complexity is merely a matter of the complexity of the technical apparatus, but in theory it is by no means impossible to reproduce by means of a very refined raster Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, once it has been programmed in input by means of a very complex sequence of binary signals).

For example, Huff (1967) has produced and analyzed a number of images showing how they could be composed of: (a) elementary units formed by four dots of two sizes, allowing five combinational possibilities; (b) an infinite array of dot sizes, allowing continuous gradations; (c) elementary units formed by a grouping of three dots with two variations in size, so that their combinational possibilities support four types of elements (three small, none large; two small, one large; one small, two large; none small, three large); (d) arrays of dots of two sizes; (e) etc. In every case a question is raised: are we still confronted with a series of analogical sizes? Or are we faced with a series of discrete units such as phonemes, which are distinguished from each other by a series of distinctive features? In this case the distinctive features of the minimal graphic units, described by Huff, are: color, density, form, position of the elements, not to speak of the configurations of the lattice.

In any case Huff himself poses the problem of a binary reduction of the graphic code: “Perhaps (the designer) will even explore the minimal situation by working with elements of only two sizes, ergo, a binary system. In so doing he does meet a most formidable problem: for, in order to maintain a continuous surface, he must solve between two textural gradients in a manner other than the photomechanical process does. Perhaps these operative economies, practised by students of hand-produced rasters, constitute a finesse of little consequence for the computer graphic technique which hypothetically has the capability to formulate the light and shade characteristics of any conceivable surface, thereby matching the photomechanical process. It does seem, however, that the gradation of one size elements in tones of brightness rather than the gradation of one-color elements in varying sizes, though resourcefully adventurous, is ill directed effort – somehow contrary to the fundamental simplicity of digital or binary computers”.

Clearly Huff’s discussion concerns the practical possibilities of graphic realization and not the theoretical possibilities of an absolute binary reduction of the code. In this last sense the examples given by Moles (1968) seem more decisive. He shows for example lattices composed of a single right-angle triangle placed in the upper or lower corner of a square compartment, so as to be able to function in the opposition ‘empty place vs. full place’.

In any case discussion of the binary possibilities of rasters in photomechanical reproduction (which is governed by criteria of practicality) is outweighed by discussion of the possibility of a realizing any ‘iconic’ image by giving digital instructions to a computer which then transmits them to an analogical plotter (28).

Obviously the computer digitally commands a plotter which restores the image by ‘analogical’ means (Soulis and Ellis, 1967:150-151). Cralle and Michael (1967:157) further explain that “When we wish to plot something, we also have to say where to plot it. The addressing scheme normally chosen is obtained by imagining a two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system, superimposed on the screen of the CRT. In both the horizontal (x) and the vertical (y) directions we can assign integers for each point to which the electron beam may be digitally deflected”. Experiments of ‘iconic’ reproduction by means of computers, such as those carried out in the Bell Telephone laboratories by Knowlton and Harmon, by the Japanese Computer Technique Group, show that the digital programming of ‘iconic’ signs can by now achieve in future high degrees of sophistication and that a greater sophistication and complexity is merely a question of time and economic means. Unfortunately this digital reduction concerns the possibility of replicating the expression using another continuum by a procedure which is not the one used by the artist. It does not concern the articulatory nature of the original expressive functive.

Computer experience tells us that it is possible (in principle) to analyze the original signal in figurae, but not that the signal was actually articulated by combination of pre-existent discrete entities. And in fact such entities are hardly identifiable, since the original signal was composed through a ‘continuous’ disposition of a ‘dense’ stuff. Thus replicability through computers or other mechanisms does not directly concern the code governing the replicated sign. It is rather a matter of technical codes governing the transmission of information (a signal-to-signal process), to be considered within the framework of communication engineering (see 1.4.4.). One could suspect that such procedures are rather connected with the production of doubles (see 3.4.7.) or partial replicas (see 3.4.8.). And this is so when a computer transfers an original ‘linear’ drawing into a plotted copy. But things go differently when an ‘absolutely dense’ oil painting is ‘translated’ into a ‘quasi-dense’ raster; in such a case it is very difficult to decide if one is dealing with a partial replica, an ‘icon’ or a pseudo-double.

Let us speak of transformation from expression to expression that offers a satisfactory laboratory model of the procedures required in cases of projection by ratio difficilis (see the models of projections in 3.6.7.).

These examples also demonstrate that, even in cases of non-replicable super-signs, there is the possibility of rendering them replicable using mechanical procedures that institute a ‘grammar’ there where was only a ‘text’. In this sense these experiments provide us with certain challenging theoretical suggestions about the nature of inventions.

Every assumption about the analogical nature of ‘iconic’ signs was always based upon (or aiming to support) the notion of the ineffability and the ‘unspeakability’ of those devices that signify through being mysteriously related to the objects. To demonstrate that at least the signals ordered to those sign-functions are open to analytical decomposition does not solve the problem but does eliminate a sort of magic. One could therefore say that the digital approach constitutes a sort of psychological support for the student who wants to further understand the mystery of iconism. When deciphering a secret message one must first be sure that it is indeed a message and therefore that there is an underlying code, to be ‘abduced’ from it; in the same way the knowledge that iconic signals also are digitally analyzable can help to promote a further enquiry as to their semiotic nature.

To return to the problem of replicas, one can replicate:

(i) features of a given system that must be combined with features of the same system in order to compose a recognizable functive;

(ii) features from a weakly structured repertoire, recognizable on the basis of perceptual mechanisms and correlated to their content by a large-scale overcoding, that must not necessarily be combined with other features;

(iii) features of a given system that must be added to a bundle or to a string of features from one or more other systems in order to compose a recognizable functive.

Features of type (i) have been considered in the preceding paragraph. Verbal language, for instance, combines elements of second articulation to construct elements of first articulation and therefore phrases. Features of type (ii) are stylizations; features of type (iii) are vectors.

I mean by stylizations certain apparently ‘iconic’ expressions that are in fact the result of a convention establishing that they will not be recognized because of their similarity to a content-model but because of their similarity to an expression-type which is not strictly compulsory and permits many free variants.

A typical example of this sort of replica is the King or the Queen in a pack of cards. We do not ‘iconically’ recognize a «man» and then a «King»; we immediately grasp the denotation «King» provided that certain pertinent elements are respected. It is also on this basis that ‘iconograms’ are coded, i.e. recognizable categories in painting such as the Virgin Mary, Saint Lucy, Victory, Athena, the Devil. In these cases the immediate denotation is a matter of ‘invention’ (they are productions governed by a ratio difficilis that establishes certain similarities with a male or female body and so on) while their full signification (this «man» is «Jupiter») is due to the presence of overcoded replicable features (stylizations).

So a painted image of the Devil is a super-sign which will be further analyzed when speaking of ‘inventions’. But, among other procedures, the replica of large-scale overcoded properties contributes to the structuring of such a sign-function. Insofar as it is an iconogram, the image of the Devil is a replica of a previously coded type, irrespective of a lot of free variants.

In fact when looking at the King of Spades or an image of the Virgin Mary we do not really have to grasp the representative meaning of the image, we do not interrogate the expression in order to guess, through a sort of backward projection at the format of the content-type. We immediately recognize this large-scale configuration as if it were an elementary feature. Some general properties having been respected, the expression is recognized as being conventionally linked to a certain content; the content can also be conceptually grasped without having recourse to its spatial and figural markers. The iconogram is a label.

In this sense even vaster configurations can be taken as stylizations; even if a more analytical glance will show them to be composed by more subtle operations. But if this analysis is not performed, they are received as if governed by a ratio facilis, even if they display the same markers as the corresponding sememe (ratio difficilis).

Let us list some of these large-scale stylizations, each category constituting a repertoire of conventional expression, therefore a sub-code:

(i) heraldic features such as the unicorn that supports the arms of the British royal family;

(ii) schematic onomatopoeias, such as /to sigh/ or /to bark/ (these could be analyzed as degenerate full onomatopoeias, and therefore as fictive samples (see 3.6.3.) but in fact they are currently accepted as arbitrary expressions;

(iii) coded macro-ambiental features, such as, in architecture, a house, a temple, a square, a street;

(iv) complex objects and their customary images (like the cars portrayed in advertising);

(v) musical types (a march, ‘thrilling’ music);

(vi) literary or artistic genres (Western, slapstick comedy);

(vii) all the elements of the so-called recognition codes (see 3.5.) by which a leopard is characterized by spots and a tiger by stripes (granted that an elementary ‘feline’ outline has been recognized on the basis of certain similarity procedures);

(viii) iconograms, as studied by iconology: the Nativity, the Last Judgment, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and so on.

(ix) pre-established evaluative and appreciative connotations conveyed by iconological means, and mainly used in Kitsch-art: a Greek temple conventionally connoting «classical beauty», a given feminine image historically connoting «grace» or «sex»;

(x) other characterizations, such as one perfume immediately connoting «seduction» or «lust» while another connotes «cleanliness», the incense smell connoting «church», and so on.

Beyond a certain limit it is very difficult to distinguish a stylization from an invention, and frequently the decision is taken not by the sender but by the addressee, who in effect performs a labor of stylization on a given expression. Everyone has experienced how a given musical composition that has for many years been enjoyed as a complex text, with all its features subjected to intensive scrutiny, is at a certain point (as one’s taste becomes accustomed to the musical object in question) simply received as an unanalyzed form that means approximately «Fifth Symphony» or quite simply «Romanticism» or «Music».

Thus stylizations are catachreses of previous inventions, super-signs that could and should convey a complex discourse (being a text) and indeed almost take on the function of proper names. Their replica, however imprecise it may be, is taken as a sufficient token, and as such faithful to its expression-type. They are the proof that a ratio difficilis may, by force of continuous exposure to communication and successive conventions, become a ratio facilis.

Stylization may also combine with other devices to make up a discourse; for instance, by putting together certain stylizations with combinational visual replicas, a road signal could ‘say’: «this road is closed to trucks, cars must run at no more than 30 miles and U-turning is forbidden; please make no noise since there is a hospital in the vicinity».

Let us now examine those features that are not combinable with features of the same system but which exclusively collaborate with features of other systems so as to make up an expression. I have called them vectors.

The classic example is the one (already given in 2.11.4., 2.11.5. and 3.5.7.) of the pointing finger: dimensional features realized by a part of a human body, such as «linearity» and «apicality» are the same as those realized by a graphic arrow; in this sense the pointing finger should be considered as an expression produced by an aggregation of combinational units, like a verbal expression, and so should the arrow. But the finger moves toward something; there is a feature of direction (which naturally characterizes a lot of other kinesic features, though here these features of movement can be articulated with other features of the same type). This directional feature orientates the attention of the addressee according to parameters such as left’, ‘right’ or ‘up’ and ‘down’ and so on. But these are not simple spatial parameters of the type left vs. right’, to be used as combinational units in other kinesic configurations; they should instead be viewed as left-to-right vs. right-to-left’.

The addressee does not have to physically follow that direction (nor indeed does there have to be anything in the indicated direction for the pointers to be significant, see 2.11.5.). As a matter of fact there are two ‘directions’: one is actually and physically perceptible and is an expressive feature; the other is the ‘signified’ direction and is mere content. The directional feature is produced according to a ratio difficilis because the produced direction is the same as that of which one is ‘speaking’.

In order to understand vectors, one must also think of other kinds of directional feature, and one must free the term ‘direction’ from spatial connotations (this perhaps being better realized by the word ‘vector’ or ‘vectorialization’). One may thus regard as vectorial devices the increasing or decreasing of vocal pitch and dynamics in paralinguistic features: for instance when uttered, a ‘question intonation’ is a vectorialization; the nature of a musical melody is grasped not only because of the articulation of combinational units but because of their precise temporal succession. Thus even syntactic-phrase markers must be considered as vectors (29).

In /John beats Mary/ it is the direction of the phrase (a spatial direction in the written phrase and a temporal one in the uttered one) that makes the content understandable; by changing round the proper names the entire content is reversed. Again, a vectorialization is neither a sign nor a complete expression in itself (except taken as an expression signifying a pure vectorial correlation as in /a⊃b/), but rather a productive feature that, in conjunction with others, contributes to the composition of the expression (30). One could say that in some cases a vector by itself can give rise to a sign-function; suppose that I hum an upward pitch-curve; I can succeed in signifying «question» (or «I am questioning» or «what?») by imposing a direction on a sound-continuum without resorting to any other device. But this is a case of coded stylization.

Many vectors are governed by a very schematic ratio difficilis so easily recognizable that, as happens with stylizations, a sort of catachresizing process takes place and the ratio difficilis practically becomes a ratio facilis. The case of the interrogative humming cited above is a typical example of this process.

Half way between replica and invention there are two kinds of productive operation that are not usually considered as semiotically definable. The first one concerns the disposition of non-semiotic elements intended to elicit an immediate response in the receiver. A flash of light during a theatrical performance, an unbearable sound, a subliminal excitation, and so on, are to be listed among stimuli rather than signs, as was stressed in 3.5.5. But in the same paragraph we noted that, when the sender knows the possible effect of the displayed stimulus, one is obliged to consider his knowledge as a sort of semiotic competence, for to him a given stimulus corresponds to a given foreseeable reaction that he expressly aims to elicit. In other words, there is a sign-function by which the stimulus is the expression plane of a supposed effect functioning as its content plane.

Nevertheless the effect of a stimulus is never completely predictable, especially when inserted among other more specifically semiotic elements within a text as a pseudo-sign. Suppose that a speaker is elaborating a persuasive discourse according to the rules of judiciary rhetoric and trying to arouse in his addressees feelings of pity and compassion. He can utter his phrases in a throbbing voice, or with barely detectable vibrations that could suggest that he is tempted to cry. These supra-segmental features could obviously be either paralinguistic devices or mere symptoms indicating his emotional state; but they might also be stimuli he inserts into the discourse in order to provoke some degree of identification in his listeners and to pull them toward the same emotional state. He is using these devices as programmed stimulations but does not know exactly how they will be received, detected, interpreted. The speaker is thus half way between the execution of certain rules of stimulation and the displaying of new unconventionalized elements that might (or might not) become recognized as semiotic devices. Sometimes the speaker is not sure of the relation between a given stimulus and a given presupposed response, and he is more making than performing a tentative coding of programmed stimuli. Therefore these devices stand between replica and invention; and may or may not be semiotic devices, thus constituting a sort of ambiguous threshold. So that even though the expressive string of programmed stimuli can be analyzed into detectable units, the corresponding content remains a nebula-like conceptual or behavioral ‘discourse’. The expression, made of analyzable and replicable units (governed by a ratio facilis) may then generate a vague discourse on the content plane. Among such programmed stimuli one might list: (i) all the programmed synesthesiae in poetry, music, painting, etc.; (ii) all so-called ‘expressive’ signs, such as those theorized by artists like Kandinskij, i.e. visual configurations that are conventionally supposed to ‘convey’ a given feeling directly (force, grace, instability, movement and so on) and that have also been studied by the theorists of Einfühlung or empathy; insofar as these devices hold a motivated relationship with psychic forces or ‘reproduce’ physical experiences, they should be dealt with in the paragraph concerning projections (3.6.7.); insofar as they are displayed by a sender who knows their emphatic effect, they are programmed stimulation (and therefore precoded devices) of which, however, the result (on the content plane) is only partially foreseeable; (iii) all production of substitutive stimuli described in 3.5.8.; (iv) many projections, about which more will be said in 3.6.7.

Anyway one should carefully distinguish between this sort of programmed stimulus and the more explicitly coded devices used to express emotions, such as body movements, facial expressions, and so on, now so precisely recorded by the latest researches in kinesics (Ekman 1969) and in paralinguistics.

Another kind of spurious semiotic operation is pseudo-combination. The most typical example is an abstract painting or an atonal musical composition. Apparently a Mondrian painting or a Schoenberg composition is perfectly replicable and therefore appears to be composed by systematically combinable units. These units are not apparently endowed with meaning but they do follow combinational rules.

Nobody can deny that there is an expression system even though the content plane remains, as it were, open to all comers. These examples are thus more open signal textures than sign-functions; for this very reason they appear to invite the attribution of a content, thus issuing a sort of interpretive challenge to their addressee (Eco, 1962). Let us call them visual or musical propositional functions that can only ‘wait’ to be correlated to a content, each being susceptible of many different correlations.

Thus when hearing a post-Webernian sound cluster one detects the presence of replicable musical units combined in a certain fashion and sometimes one also knows the rule governing this kind of aggregation of material events.

However, the problem seems to change when one is dealing with abstract expressionist paintings, random music, John Cage’s happenings and so on. In these cases one can speak of textural clouds which lack any predictable rule. Can one then continue to speak of a pseudo-combinational operation? It is exactly this kind of artistic operation which prompted Lévi-Strauss (1964) to deny any linguistic nature to these phenomena, in view of their lack of discrete units or of oppositions based on an underlying system.

One could respond that in these cases the entire material texture, through its very absence of rules, opposed itself to the entire system of rules governing ‘linguistic’ art, thus creating a sort of macrosystem in which manifestations of pure noise are opposed to manifestations of informational order. This solution has the advantage of elegance and does in fact explain many of the intentions behind the work of ‘informel’ artists, but it is equivalent to maintaining that even in non-semiotic phenomena there is a semiotic purport insofar as they are displayed in order to make absent semiotic phenomena relevant. In this sense the creation of ‘art informel’ would be the same as silence in order to ‘express’ refusal to speak.

As a matter of fact there is another reason why many examples of this kind of art have at least the nature of pseudo-combinations. The clue is given by artists themselves when they tell us that they examine the very veining of material, the texture of the wood, canvas, iron or sounds and noises, trying to find in them relationships, forms, new visual or auditory paths. The artist discovers at the deeper level of the expression-continuum a new system of relations that the preceding segmentation of that continuum, giving rise to an expression form, had never made pertinent. These new pertinent features, along with their mode of organization, are so detectable and recognizable, that one becomes able to isolate the work of a given artist, and thus to distinguish, for instance, Fautrier from Pollock or Boulez from Berio.

In this case the establishing of pseudo-combinational units does not precede the making of the work itself; on the contrary, the growth of the work coincides with the birth of the systems. And, provided that these forms convey a content (which is sometimes identical with a metalinguistic account of the nature of the work and its ideological purport), an entire code is proposed as the work is established.

Let me stress that we are here dealing with three problems: (i) the segmentation performed below the level of the recognized expression form, that is, a further segmentation of the expression-continuum; this aspect will become very important in section 3.7. when speaking of the aesthetic text; (ii) the complexity of this segmentation at various levels, which sometimes makes it impossible to detect distinguishable units, thereby making it impossible to establish replicable expression types; when this happens pseudo-combinational units cannot be replicated (in post-Webernian music some sound-clusters can be replicated – indeed there is a score prescribing their way of performance – while others can only be ‘suggested’ by the composer and require an inventive participation on the part of the performer; a Dubuffet painting can hardly be replicated); (iii) the invention of new expression levels along with their possible segmentation and systematization; in such cases pseudo-combinational procedure turns into purely inventive procedure, thus bringing us to the last item in the present classification of modi faciendi signa.

In Table 39 pseudo-combinational units are nevertheless listed among the modes of production governed by a ratio facilis because, as long as they are replicable, they have to reproduce an expression type, though it seems doubtful that they represent a definite case of sign-function so much as one of an ‘open’ signal. But if their constitutive units are not detectable, they are not replicable, and they thus remain half way between sign production and the proposal of new possibilities for manipulating continua.

It is not by chance that programmed stimuli have on the contrary been listed in the same row as examples and samples, in a middle position between ratio facilis and ratio difficilis. Sometimes, as the empathy theorists assume, there is a sort of ‘motivated’ link between a certain line and a certain feeling, and thus cases of stimulation rely on procedures of projection or stylization.

We may define as invention a mode of production whereby the producer of the sign-function chooses a new material continuum not yet segmented for that purpose and proposes a new way of organizing (of giving form to) it in order to map within it the formal pertinent element of a content-type. Thus in invention we have a case of ratio difficilis realized within a heteromaterial expression; but since no previous convention exists to correlate the elements of the expression with the selected content, the sign producer must in some way posit this correlation so as to make it acceptable. In this sense inventions are radically different from recognition, choice, and replica.

Everybody recognizes an expression produced by recognition because a previous experience has linked a given expression-unit with a given content-unit. Everybody recognizes an expression produced by a choice made on the basis of a common mechanism of abstraction, such as the acknowledging of a given item as representative of the class to which it belongs. Everybody recognizes an expression produced by replica, because the replica replicates an expression-type which has already been conventionally correlated with a given content. In all these cases, whether the ratio is facilis or difficilis, everybody recognizes the correspondence between a token and its type because the type already exists as a cultural product. Whether the token expression reproduces a content type, as in the case of imprints, or an expression type, as in the case of phonemes and words, the procedure follows certain basic requirements.

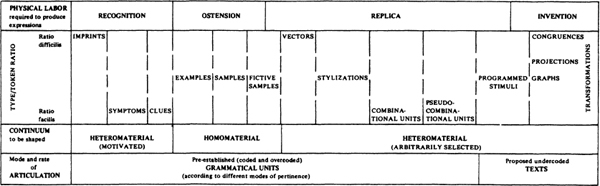

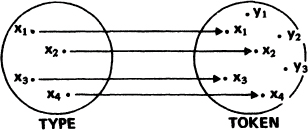

If one views a type (whether of content or of expression) as a set of properties that have been singled out as pertinent, the token is obtained by mapping out the elements of the original set in terms of those of the token set. This procedure can be represented by Table 40, where the xs represent the pertinent properties of the type and the ys non-pertinent and variable elements (31).

In cases of ratio facilis mapping presents no problem; it simply involves the reproduction of a property using the same sort of material as that prescribed by the type. In the case of a phoneme the type may, for instance, prescribe ‘labial+voiced’ (thereby implying: by means of human phonation), thus establishing how to produce a [b].

The notion of mapping is somewhat more problematic in cases of ratio difficilis, because the type of a ratio difficilis is a content unit, a sememe, and its properties are semantic markers, and are not in principle linked to any particular expression continuum.

So what does one mean by mapping the pertinent properties of a glass of wine within another material so as to produce the recognizable wet imprint of a glass of wine upon a table? Formulating the question in this way might make for a puzzling answer, but this is because of one’s ‘referential’ bias. As a matter of fact the imprint of a glass of wine does not have to possess the properties of the object «glass of wine» but it does have to possess those of the cultural unit «imprint of a glass of wine». And in this case the semantic representation of the entity in question entails no more than four semantic markers, i.e. «circle», «red», «length of the inradius (or diameter)» and «wet». To map these markers within another material simply means to realize the geometrical and chemical interpretants of the sememes «circle», «red», «diameter X» and «wet». This done, the mapping process is complete, and the realization of a token of the content type a comparatively easy matter. In this sense one cannot maintain that the imprint of a hare’s paw is an iconic feature in the same way as is the image of a hare. In the former case the content type is culturally established, whereas in the latter one it is not (except in cases of stylization).

The only problem would appear to be: in what sense does a circle of a given diameter realized upon a table map the semantic markers «circle» and «diameter X»?

But on second thoughts, that question is not so different from asking in what sense a labial and voiced consonant maps the abstact phonological type ‘labial+voiced’ in sound. In the latter case the answer seems easy enough: there are certain sound parameters which permit the realization and recognition of the replica (as to how the realization of a parameter is recognizable, this sends us back to basic perceptive requirements that, as was noted in 3.4.7. and 3.4.8., are postulates rather than theorems for a semiotic theory).