The aim of this book is to explore the theoretical possibility and the social function of a unified approach to every phenomenon of signification and/or communication. Such an approach should take the form of a general semiotic theory, able to explain every case of sign-function in terms of underlying systems of elements mutually correlated by one or more codes.

A design for a general semiotics(1) should consider: (a) a theory of codes and (b) a theory of sign production – the latter taking into account a large range of phenomena such as the common use of languages, the evolution of codes, aesthetic communication, different types of interactional communicative behavior, the use of signs in order to mention things or states of the world and so on.

Since this book represents only a preliminary exploration of such a theoretical possibility, its first chapters are necessarily conditioned by the present state of the art, and cannot evade some questions that – in a further perspective – will definitely be left aside. In particular one must first take into account the all-purpose notion of ‘sign’ and the problem of a typology of signs (along with the apparently irreducible forms of semiotic enquiry they presuppose) in order to arrive at a more rigorous definition of sign-function and at a typology of modes of sign-production.

Therefore a first chapter will be devoted to the analysis of the notion of ‘sign’ in order to distinguish signs from non-signs and to translate the notion of ‘sign’ into the more flexible one of sign-function (which can be explained within the framework of a theory of codes). This discussion will allow me to posit a distinction between ‘signification’ and ‘communication’: in principle, a semiotics of signification entails a theory of codes, while a semiotics of communication entails a theory of sign production.

The distinction between a theory of codes and a theory of sign-production does not correspond to the ones between ‘langue’ and ‘parole’, competence and performance, syntactics (and semantics) and pragmatics. One of the claims of the present book is to overcome these distinctions and to outline a theory of codes which takes into account even rules of discoursive competence, text formation, contextual and circumstantial (or situational) disambiguation, therefore proposing a semantics which solves within its own framework many problems of the so-called pragmatics.

It is not by chance that the discriminating categories are the ones of signification and communication. As will be seen in chapters 1 and 2, there is a signification system (and therefore a code) when there is the socially conventionalized possibility of generating sign-functions, whether the functives of such functions are discrete units called signs or vast portions of discourse, provided that the correlation has been previously posited by a social convention. There is on the contrary a communication process when the possibilities provided by a signification system are exploited in order to physically produce expressions for many practical purposes. Thus the difference between the two theoretical approaches outlined in chapters 2 and 3 concerns the difference between rules and processes (or, in Aristotelian terms, metaphorically used, power and act). But when the requirements for performing a process are socially recognized and precede the process itself, then these requirements are to be listed among the rules (they become rules of discoursive competence, or rules of ‘parole’ foreseen by the ‘langue’) and can be taken into account by a theory of physical production of signs only insofar as they have been already coded. Even if the theory of codes and the theory of sign production succeed in eliminating the naive and non-relational notion of ‘sign’, this notion appears to be so suitable in ordinary language and in colloquial semiotic discussions that it should not be completely abandoned. It would be uselessly oversophisticated to get rid of it. An atomic scientist knows very well that so-called ‘things’ are the results of a complex interplay of microphysical correlations, and nevertheless he can quite happily continue to speak about ‘things’ when it is convenient to do so. In the same way I shall continue to use the word /sign/ every time the correlational nature of the sign-function may be presupposed. Nevertheless the fourth chapter of the book will be devoted to a discussion of the very notion of the ‘typology of signs’: starting from Peirce’s trichotomy (symbols, indices and icons), I shall show to what degree these categories cover both a more segmentable field of sign-functions and an articulated range of ‘sign producing’ operations, giving rise to a more comprehensive n-chotomy of various modes of sign production.

A general semiotic theory will be considered powerful according to its capacity for offering an appropriate formal definition for every sort of sign-function, whether it has already been described and coded or not. So the typology of modes of sign-production aims at proposing categories able to describe even those as yet uncoded sign-functions conventionally posited in the very moment in which they appear for the first time.

Dealing as it does with all these subjects, a project for a general semiotics will encounter some boundaries or thresholds. Some of these must be posited by a purely transitory agreement, others are determined by the very object of the discipline. The former will be called ‘political boundaries’, the latter ‘natural boundaries’; (it will be shown in 0.9 that there also exists a third form of threshold, of an epistemological nature).

A general introduction to semiotics has either to recognize or to posit, to respect or to trespass on all these thresholds. The political boundaries are of three types:

(i) There are ‘academic’ limits in the sense that many disciplines other than semiotics have already undertaken or are at present undertaking research on subjects that a semiotician cannot but recognize as his own concern; for instance formal logic, philosophical semantics and the logic of natural languages deal with the problem of the truth value of a sentence and with the various sorts of so-called ‘speech acts’, while many currents in cultural anthropology (for instance ‘ethnomethodology’) are concerned with the same problems seen from a different angle; the semiotician may express the wish that one of these days there will be a general semiotic discipline of which all these researches and sciences can be recognized as particular branches; in the meantime a tentative semiotic approach may try to incorporate the results of these disciplines and to redefine them within its own theoretical framework.

(ii) There are ‘co-operative’ limits in the sense that various disciplines have elaborated theories or descriptions that everybody recognizes as having semiotic relevance (for instance both linguistics and information theory have done important work on the notion of code; kinesics and proxemics are richly exploring non-verbal modes of communication, and so on): in this case a general semiotic approach should only propose a unified set of categories in order to make this collaboration more and more fruitful; at the same time it can eliminate the naive habit of translating (by dangerous metaphorical substitutions) the categories of linguistics into different frameworks.

(iii) There are ‘empirical’ limits beyond which stand a whole group of phenomena which unquestionably have a semiotic relevance even though the various semiotic approaches have not yet completely succeeded in giving them a satisfactory theoretical definition: such as paintings and many types of complex architectural and urban objects; these empirical boundaries are rather imprecise and are shifting step by step as new researches come into being (for instance the problem of a semiotics of architecture from 1964 to 1974, see Eco 1973 e).

By natural boundaries I mean principally those beyond which a semiotic approach cannot go; for there is non-semiotic territory since there are phenomena that cannot be taken as sign-functions. But by the same term I also mean a vast range of phenomena prematurely assumed not to have a semiotic relevance. These are the cultural territories in which people do not recognize the underlying existence of codes or, if they do, do not recognize the semiotic nature of those codes, i.e., their ability to generate a continuous production of signs. Since I shall be proposing a very broad and comprehensive definition of sign-function – therefore challenging the above refusals – this book is also concerned with such phenomena. These will be directly dealt with in this Introduction: they happen to be co-extensive with the whole range of cultural phenomena, however pretentious that approach may at first seem.

This project for semiotics, to study the whole of culture, and thus to view an immense range of objects and events as signs, may give the impression of an arrogant ‘imperialism’ on the part of semioticians. When a discipline defines ‘everything’ as its proper object, and therefore declares itself as concerned with the entire universe (and nothing else) it’s playing a risky game. The common objection to the ‘imperialist’ semiotician is: well, if you define a peanut as a sign, obviously semiotics is then concerned with peanut butter as well – but isn’t this procedure a little unfair? What I shall try to demonstrate in this book, basing myself on a highly reliable philosophical and semiotical tradition, is that – semiotically speaking –. there is not a substantial difference between peanuts and peanut butter, on the one hand, and the words /peanuts/ and /peanut butter/ on the other. Semiotics is concerned with everything that can be taken as a sign. A sign is everything which can be taken as significantly substituting for something else. This something else does not necessarily have to exist or to actually be somewhere at the moment in which a sign stands in for it. Thus semiotics is in principle the discipline studying everything which can be used in order to lie. If something cannot be used to tell a lie, conversely it cannot be used to tell the truth: it cannot in fact be used ‘to tell’ at all. I think that the definition of a ‘theory of the lie’ should be taken as a pretty comprehensive program for a general semiotics.

Any study of the limits and laws of semiotics must begin by determining whether (a) one means by the term ‘semiotics’ a specific discipline with its own method and a precise object; or whether (b) semiotics is a field of studies and thus a repertoire of interests that is not as yet completely unified. If semiotics is a field then the various semiotic studies would be justified by their very existence: it should be possible to define semiotics inductively by extrapolating from the field of studies a series of constant tendencies and therefore a unified model. If semiotics is a discipline, then the researcher ought to propose a semiotic model deductively which would serve as a parameter on which to base the inclusion or exclusion of the various studies from the field of semiotics.

One cannot do theoretical research without having the courage to put forward a theory, and, therefore, an elementary model as a guide for subsequent discourse; all theoretical research must however have the courage to specify its own contradictions, and should make them obvious where they are not apparent.

As a result, we must, above all, keep in mind the semiotic field as it appears today, in all its many and varied forms and in all its disorder. We must then propose an apparently simplified research model. Finally we must constantly contradict this model, isolating all the phenomena which do not fit in with it and which force it to restructure itself and to broaden its range. In this way we shall perhaps succeed in tracing (however provisionally) the limits of future semiotic research and of suggesting a unified method of approach to phenomena which apparently are very different from each other, and as yet irreducible.

At first glance this survey will appear as a list of communicative behaviors, thus suggesting one of the hypotheses governing my research: semiotics studies all cultural processes as processes of communication. Therefore each of these processes would seem to be permitted by an underlying system of significations. It is very important to make this distinction clear in order to avoid either dangerous misunderstandings or a sort of compulsory choice imposed by some contemporary semioticians: it is absolutely true that there are some important differences between a semiotics of communication and a semiotics of signification; this distinction does not, however, set two mutually exclusive approaches in opposition.

So let us define a communicative process as the passage of a signal (not necessarily a sign) from a source (through a transmitter, along a channel) to a destination. In a machine-to-machine process the signal has no power to signify in so far as it may determine the destination sub specie stimuli. In this case we have no signification, but we do have the passage of some information.

When the destination is a human being, or ‘addressee’ (it is not necessary that the source or the transmitter be human, provided that they emit the signal following a system of rules known by the human addressee), we are on the contrary witnessing a process of signification – provided that the signal is not merely a stimulus but arouses an interpretive response in the addressee. This process is made possible by the existence of a code.

A code is a system of signification, insofar as it couples present entities with absent units. When – on the basis of an underlying rule – something actually presented to the perception of the addressee stands for something else, there is signification. In this sense the addressee’s actual perception and interpretive behavior are not necessary for the definition of a significant relationship as such: it is enough that the code should foresee an established correspondence between that which ‘stands for’ and its correlate, valid for every possible addressee even if no addressee exists or ever will exist.

A signification system is an autonomous semiotic construct that has an abstract mode of existence independent of any possible communicative act it makes possible. On the contrary (except for stimulation processes) every act of communication to or between human beings – or any other intelligent biological or mechanical apparatus – presupposes a signification system as its necessary condition.

It is possible, if not perhaps particularly desirable, to establish a semiotics of signification independently of a semiotics of communication: but it is impossible to establish a semiotics of communication without a semiotics of signification.

Once we admit that the two approaches must follow different methodological paths and require different sets of categories, it is methodologically necessary to recognize that, in cultural processes, they are strictly intertwined. This is the reason why the following directory of problems and research techniques mixes together both aspects of the semiotic phenomenon.

Granted this much, the following areas of contemporary research – starting from the apparently more ‘natural’ and ‘spontaneous’ communicative processes and going on to more complex ‘cultural’ systems – may be considered to belong to the semiotic field.

Zoosemiotics: it represents the lower limit of semiotics because it concerns itself with the communicative behavior of non-human (and therefore non-cultural) communities. But through the study of animal communication we can achieve a definition of what the biological components of human communication are: or else a recognition that even on the animal level there exist patterns of signification which can, to a certain degree, be defined as cultural and social. Therefore the semantic area of these terms is broadened and, consequently, also our notion of culture and society (Sebeok, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1973).

Olfactory signs: Romantic poetry (Baudelaire) has already singled out the existence of a ‘code of scents’. If there are scents with a connotative value in an emotive sense, then there are also odors with precise referential values. These can be studied as indices (Peirce, 1931) as proxemic indicators (Hall, 1966) as chemical qualifiers, etc.

Tactile communication: studied by psychology, present and recognized in communication among the blind and in proxemic behavior (Hall, 1966), it is amplified to include clearly codified social behavior such as the kiss, the embrace, the smack, the slap on the shoulder, etc. (Frank, 1957; Efron, 1941).

Codes of taste: present in culinary practice, studied by cultural anthropology, they have found a clearly ‘semiotic’ systematization in Lévi-Strauss (1964).

Paralinguistics: studies the so-called suprasegmental features and the free variants which corroborate linguistic communication and which increasingly appear as institutionalized and systematized. See the studies of Fonagy (1964), Stankiewicz (1964), Mahl and Schulze (1964, with a bibliography of 274 titles). Trager (1964) subdivides all the sounds without linguistic structure into (a) “voice sets”, connected with sex, age, state of health, etc.; (b) paralanguage, divided into (i) “Voice qualities” (pitch range, vocal lip control, glottis control, articulatory control, etc.); (ii) “vocalizations”, in turn divided into (ii-1) “vocal characterizes” (laughing, crying, whimpering, sobbing, whining, whispering, yawning, belching, etc.), (ii-2) “vocal qualifiers” (intensity, pitch height, extent), (ii-3) “Vocal segregates” (noises of the tongue and lips which accompany interjections, nasalizations, breathing, interlocutory grunts, etc.). Another object of paralinguistics is the study of the language of drums and whistles (La Barre, 1964).

Medical semiotics: until a short time ago this was the only type of research which might be termed ‘semiotics’ or ‘semiology’ (so that even today there is still some misunderstanding). In any case it belongs to general semiotics (as treated in this book), and in two senses. As a study of the connection between certain signs or symptoms and the illness that they indicate, this is a study and a classification of indices in Peirce’s sense (Ostwald, 1964). As a study of the way in which the patient verbalizes his own internal symptoms, this extends on its most complex level to psychoanalysis, which, apart from being a general theory of neuroses and a therapy, is a systematic codification of the meaning of certain symbols furnished by the patient (Morris, 1946; Lacan, 1966; Piro, 1967; Maccagnani, 1967; Szasz, 1961; Barison, 1961).

Kinesics and proxemics: the idea that gesturing depends on cultural codes is now an acquired notion of cultural anthropology. As to pioneer studies in this field see De Jorio (1832), Mallery (1881), Kleinpaul (1888), Efron (1941), Mauss (1950); as to contemporary developments see Birdwhistell (1952, 1960, 1963, 1965, 1966, 1970), Guilhot (1962), LaBarre (1964), Hall (1959, 1966), Greimas (1968), Ekman and Friesen (1969), Argyle (1972) and others. Ritualized gesture, from etiquette to liturgy and pantomime, is studied by Civ’ian (1962, 1965).

Musical codes: the whole of musical science since the Pythagoreans has been an attempt to describe the field of musical communication as a rigorously structured system. We note that until a few years ago contemporary musicology had scarcely been influenced by the current structuralist studies, which are concerned with methods and themes that it had absorbed centuries ago. Nevertheless in the last two or three years musical semiotics has been definitely established as a discipline aiming to find its ‘pedigree’ and developing new perspectives. Among the pioneer works let us quote the bibliography elaborated by J.J. Nattiez in Musique en jeu, 5, 1971. As for the relationship between music and linguistics, and between music and cultural anthropology, see Jakobson (1964, 1967), Ruwet (1959, 1973) and Lévi-Strauss (1965, in the preface to The Raw and the Cooked). Outlines of new trends are to be found in Nattiez (1971, 1972, 1973), Osmond-Smith (1972, 1973), Stefani (1973), Pousseur (1972) and others. As a matter of fact music presents, on the one hand, the problem of a semiotic system without a semantic level (or a content plane): on the other hand, however, there are musical ‘signs’ (or syntagms) with an explicit denotative value (trumpet signals in the army) and there are syntagms or entire ‘texts’ possessing pre-culturalized connotative value (‘pastoral’ or ‘thrilling’ music, etc.). In some historical eras music was conceived as conveying precise emotional and conceptual meanings, established by codes, or, at least, ‘repertoires’ (see, for the Baroque era, Stefani, 1973, and Pagnini, 1974).

Formalized languages: from algebra to chemistry there can be no doubt that the study of these languages lies within the scope of semiotics. Of relevance to these researches are the studies of mathematical structures (Vailati, 1909; Barbut, 1966; Prieto, 1966; Gross and Lentin, 1967; Bertin, 1967), not to forget the ancient studies of ‘ars combinatoria’ from Raimundo Lullo to Leibniz (see Mäll, 1968; Kristeva, 1968 as well as Rossi, 1960). Also included under this heading are the attempts to find a cosmic and interplanetary language (Freudentahl, 1960(2)), the structures of systems such as Morse code or Boole’s algebra as well as the formalized languages for electronic computers (see Linguaggi nella società e nella tecnica, 1970). Here there appears the problem of a “meta-semiology”.(3)

Written languages, unknown alphabets, secret codes: whereas the study of ancient alphabets and secret codes has famous precedents in archeology and cryptography, the attention paid to writing, as distinct from the laws of language which writing transcribes, is relatively new (for a survey on classical bibliography see Gelb, 1952 and Trager, 1972). We call to mind either studies such as that of McLuhan (1962) on the Weltanschauung determined by printing techniques, and the anthropological revolution of the “Gutenberg Galaxy” or the “grammatology” of Derrida (1967b). Bridging the gap between classic semantics and cryptography are studies such as that of Greimas (1970) on “écriture cruciverbiste” and all the studies on the topic of riddles and puzzles (e.g. Krzyzanowski, 1960).

Natural languages: every bibliographical reference in this area should refer back to the general bibliography of linguistics, logic, philosophy of language, cultural anthropology, psychology etc. We should only add that semiotic interests, though arising on the one hand from studies in logic and the philosophy of language (Locke, Peirce, and so on), on the other hand assume their most complete form in studies on structural linguistics (Saussure, Jakobson, Hjelmslev).

Visual communication: there is no need for bibliographical reference because this item is dealt with explicitly in this book (in ch. 3). But we must remember that studies of this kind cover an area extending from systems possessing the highest degree of formalization (Prieto, 1966), through graphic systems (Bertin, 1967), color systems (Itten, 1961), to the study of iconic signs (Peirce, 1931; Morris, 1946, etc).

This last notion has been particularly questioned in the recent years by Eco (1968, 1971, 1973), Metz (1970, 1971), Verón (1971, 1973), Krampen (1973), Volli (1973) and others. The latest developments begin to recognize beneath the rather vague category of ‘iconism’ a more complex series of signs, thus moving beyond Peirce’s tripartition of signs into Symbols, Icons and Indices. Finally at the highest levels we have the study of large iconographic units (Panofsky and Schapiro in general), visual phenomena in mass communication, from advertisements to comic strips, from paper money system to playing-cards and fortune-telling cards (Lekomceva, 1962; Egorov, 1965), rebuses, clothes (Barthes, 1967) until finally we come to the visual study of architecture (see Eco, 1973 e), choreographical notation, geographic and topographic maps (Bertin, 1967), and film (Metz, 1970c, 1974; Bettetini, 1968, 1971, 1973; and others).

Systems of objects: objects as communicative devices come within the realm of semiotics, ranging from architecture to objects in general (see Baudrillard, 1968, and the issue of “Communications” 13, 1969 Les Objets). On architecture see Eco, 1968; Koenig, 1970; Garroni, 1973; De Fusco, 1973.

Plot structure: ranging from the studies of Propp (1928) to more recent European contributions (Bremond, 1964, 1966, 1973; Greimas, 1966, 1970; Metz, 1968; Barthes, 1966; Todorov, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1970; Genette, 1966; V. Morin, 1966; Gritti, 1966, 1968). Worthy of emphasis are the studies of the Soviets (Ščeglov, 1962; Žolkovsky, 1962, 1967; Karpinskaja-Revzin, 1966; as well as the classic Russian formalists). The study of plot has found its most important development in the study of primitive mythology (Lévi-Strauss, 1958a, 1958c, 1964; Greimas, 1966; Maranda, 1968) and of games and tales belonging to folklore (Dundes, 1964; Beaujour, 1968; Greimas-Rastier, 1968; Maranda, E.K. & P., 1962). But it also reaches to studies on mass communication, from comic strips (Eco, 1964) to the detective story (Ščeglov, 1962 a) and the popular nineteenth-century romance (Eco, 1965, 1967).

Text theory: the exigencies of a ‘transphrastic’ linguistic and developments in plot analysis (as well as the poetic language analysis) have led semiotics to recognize the notion of text as a macro-unit, ruled by particular generative rules, in which sometimes the very notion of ‘sign’ – as an elementary semiotic unit – is practically annihilated (Barthes, 1971, 1973; Kristeva, 1969). As for a generative text grammar see van Dijk (1970) and Petöfi (1972).

Cultural codes: semiotic research finally shifts its attention to phenomena which it would be difficult to term sign systems in a strict sense, nor even communicative systems, but which are rather behavior and value systems. I refer to systems of etiquette, hierarchies and the so-called ‘modelling secondary systems’ – under which heading the Soviets bring in myths, legends, primitive theologies which present in an organized way the world vision of a certain society (see Ivanov and Toporov, 1962; Todorov, 1966) and finally the typology of cultures (Lotman, 1964, 1967 a), which study the codes which define a given cultural model (for example the code of the mentality of medieval chivalry); finally models of social organization such as family systems (Lévi-Strauss, 1947) or the organized communicative network of more advanced groups and societies (Moles, 1967).

Aesthetic texts: the semiotic field also spills over into the area traditionally belonging to aesthetics. Certainly aesthetics is also concerned with non-semiotic aspects of art (such as the psychology of artistic creation, the relations between artistic form and natural form, the physical-psychological definition of aesthetic enjoyment, the analysis of the relations between art and society, etc.). But clearly all these problems could be dealt with from a semiotic point of view as soon as it is recognized (see 3.7) that every code allows for an aesthetic use of its elements.

Mass communication: as with aesthetics, this is a field which concerns many disciplines, from psychology to sociology and pedagogy (see Eco, 1964). But in most recent years the tendency has been to see the problem of mass communication in a semiotic perspective, while semiotic methods have been found useful in the explanation of numerous phenomena of mass communication.

The study of mass communication exists as a discipline not when it examines the technique or effects of a particular genre (detective story or comic strip, song or film) by means of a particular method of study, but when it establishes that all these genres, within an industrial society, have a characteristic in common.

The theories and analyses of mass communication are in fact applied to various genres, granted: 1) an industrial society which seems to be comparatively homogeneous but is in reality full of differences and contrasts; 2) channels of communication which make it possible to reach not determined groups but an indefinite circle of receivers in various sociological situations; 3) productive groups which work out and send out given messages by industrial means.

When these three conditions exist the differences in nature and effect between the various means of communication (movie, newspaper, television or comic strips) fade into the background compared with the emergence of common structures and effects.

The study of mass communication proposes a unitary object inasmuch as it claims that the industrialization of communications changes not only the conditions for receiving and sending out messages but (and it is with this apparent paradox that the methodology of these studies is concerned) the very meaning of the message (which is to say that block of meanings which was thought to be an unchangeable part of the message as devised by the author irrespective of its means of diffusion). In order to study mass communication one can and should resort to disparate methods ranging from psychology to sociology and stylistics; but one can plan a unitary study of such phenomena only if the theories and analyses of mass communication are considered as one sector of a general semiotics (see Fabbri, 1973).

Rhetoric: the revival in studies of rhetoric is currently converging on the study of mass communication (and therefore of communication with the intention of persuasion). A rereading of traditional studies in the light of semiotics produces a great many new suggestions. From Aristotle to Quintilian, through the medieval and Renaissance theoreticians up to Perelman, rhetoric appears as a second chapter in the general study of semiotics (following linguistics) elaborated centuries ago, and now providing tools for a discipline which encompasses it. Therefore a bibliography of the semiotic aspects of rhetoric seems identical with a bibliography of rhetoric (for a preliminary orientation see Lausberg, 1960; Groupe μ, 1970; Chatman, 1974).

Now that we have surveyed the whole semiotic field in a somewhat approximate and disordered fashion, one question emerges: can these diverse problems and diverse approaches be unified? To answer such a question we must abandon mere description and hazard a provisional theoretical definition of semiotics.

We could start by using the definitions put forward by two scholars who foretold the official birth and scientific organization of the discipline: Saussure and Peirce. According to Saussure (1916) “la langue est un système de signes exprimant des idées et par là comparable à l’écriture, à l’alphabet des sourds-muets, aux rites symboliques, aux formes de politesse, aux signaux militaires, etc. etc. Elle est seulement le plus important de ces systèmes. On peut donc concevoir une science qui étudie la vie des signes au sein de la vie sociale; elle formerait une partie de la psychologie sociale, et par conséquent de la psychologie générale; nous la nommerons sémiologie (du grec sëmeion, ‘signe’). Elle nous apprendrait en quoi consistent les signes, quelles lois les regissent. Puisqu’elle n’existe pas encore, on ne peut pas dire ce qu’elle sera; mais elle a droit à l’existence, sa place est déterminée d’avance”.

Saussure’s definition is rather important and has done much to increase semiotic awareness. As will be shown in chapter 1 the notion of a sign as a twofold entity (signifier and signified or sign-vehicle and meaning) has anticipated and promoted all correlational definitions of sign-function. Insofar as the relationship between signifier and signified is established on the basis of a system of rules which is ‘la langue’, Saussurean semiology would seem to be a rigorous semiotics of signification. But it is not by chance that those who see semiotics as a theory of communication rely basically on Saussure’s linguistics. Saussure did not define the signified any too clearly, leaving it half way between a mental image, a concept and a psychological reality; but he did clearly stress the fact that the signified is something which has to do with the mental activity of anybody receiving a signifier: according to Saussure signs ‘express’ ideas and provided that he did not share a Platonic interpretation of the term ‘idea’, such ideas must be mental events that concern a human mind. Thus the sign is implicitly regarded as a communicative device taking place between two human beings intentionally aiming to communicate or to express something. It is not by chance that all the examples of semiological systems given by Saussure are without any shade of doubt strictly conventionalized systems of artificial signs, such as military signals, rules of etiquette and visual alphabets. Those who share Saussure’s notion of sémiologie distinguish sharply between intentional, artificial devices (which they call ‘signs’) and other natural or unintentional manifestations which do not, strictly speaking, deserve such a name.

In this sense the definition given by Peirce seems to me more comprehensive and semiotically more fruitful: “I am, as far as I know, a pioneer, or rather a backwoodsman, in the work of clearing and opening up what I call semiotic, that is the doctrine of the essential nature and fundamental varieties of possible semiosis” (1931, 5.488). “By semiosis I mean an action, an influence, which is, or involves, a cooperation of three subjects, such as a sign, its object and its interpretant, this tri-relative influence not being in anyway resolvable into actions between pairs” (5.484). I shall define the ‘interpretant’ better later (chapter 2), but it is clear that the ‘subjects’ of Peirce’s ‘semiosis’ are not human subjects but rather three abstract semiotic entities, the dialectic between which is not affected by concrete communicative behavior. According to Peirce a sign is “something which stands to somebody for something in some respects or capacity” (2.228). As will be seen, a sign can stand for something else to somebody only because this ‘standing-for’ relation is mediated by an interpretant. I do not deny that Peirce also thought of the interpretant (which was another sign translating and explaining the first one, and so on ad infinitum) as a psychological event in the mind of a possible interpreter; I only maintain that it is possible to interpret Peirce’s definition in a non-anthropomorphic way (as is proposed in chapters 1 and 2). It is true that the same interpretation could also fit Saussure’s proposal; but Peirce’s definition offers us something more. It does not demand, as part of a sign’s definition, the qualities of being intentionally emitted and artificially produced.

The Peircean triad can be also applied to phenomena that do not have a human emitter, provided that they do have a human receiver, such being the case with meteorological symptoms or any other sort of index.

Those who reduce semiotics to a theory of communicational acts cannot consider symptoms as signs, nor can they accept as signs any other human behavioral feature from which a receiver infers something about the situation of the sender even though this sender is unaware of sending something to somebody (see for instance Buyssens, 1943; Segre, 1969 etc.). Since such authors maintain that they are solely concerned with communication, they have the right to exclude a lot of phenomena from the set of signs. Instead of denying that right I would like to defend the right to establish a semiotic theory able to take into account a broader range of sign-phenomena.

I propose to define as a sign everything that, on the grounds of a previously established social convention, can be taken as something standing for something else. In other terms I would like to accept the definition proposed by Morris (1938) according to which “something is a sign only because it is interpreted as a sign of something by some interpreter . . . . Semiotics, then, is not concerned with the study of a particular kind of objects, but with ordinary objects insofar (and only insofar) as they participate in semiosis”. I suppose it is in this sense that one must take Peirce’s definition of the ‘standing-for’ power of the sign “in some respect or capacity”. The only modification that I would introduce into Morris’s definition is that the interpretation by an interpreter, which would seem to characterize a sign, must be understood as the possible interpretation by a possible interpreter. But this point will be made clearer in chapter 2. Here it suffices to say that the human addressee is the methodological (and not the empirical) guarantee of the existence of a signification, that is of a sign-function established by a code. But on the other hand the supposed presence of a human sender is not the guarantee of the sign-nature of a supposed sign. Only under this condition is it possible to understand symptom and indices as signs (as Peirce does).

The semiotic nature of indices and symptoms will be examined and reformulated in ch. 3. Here we only need to consider two types of so-called ‘signs’ that seem to escape a communicational definition: they are (a) physical events coming from a natural source and (b) human behavior not intentionally emitted by its senders. Let us look more closely at these two instances.

We are able to infer from smoke the presence of fire, from a wet spot the fall of a raindrop, from a track on the sand the passage of a given animal, and so on. All these are cases of inference and our everyday life is filled with a lot of these inferential acts. It is incorrect to say that every act of inference is a ‘semiosic’ act – even though Peirce did so – and it is probably too rash a statement to assert that every semiosic process implies an act of inference, but it can be maintained that there exist acts of inference which must be recognized as semiosic acts. It is not by chance that ancient philosophy has so frequently associated signification and inference. A sign was defined as the evident antecedent of a consequent or the consequent of an antecedent when similar consequences have been previously observed (Hobbes, Leviathan, 1, 3); as an entity from which the present or the future or past existence of another being is inferred (Wolff, Ontology, 1952); as a proposition constituted by a valid and revealing connection to its consequent (Sextus Empiricus, Adv. math., VIII, 245). Probably this straightforward identification of inference and signification leaves many shades of difference unexplained: it only needs to be corrected by adding the expression ‘when this association is culturally recognized and systematically coded’.

The first doctor who discovered a sort of constant relationship between an array of red spots on the patient’s face and a given disease (measles) made an inference: but insofar as this relationship has been made conventional and has been registered as such in medical treatises a semiotic convention (4) has been established. There is a sign every time a human group decides to use and to recognize something as the vehicle of something else.

In this sense events coming from a natural source must also be listed as signs: for there is a convention positing a coded correlation between an expression (the perceived event) and a content (its cause or its possible effect). An event can be a sign-vehicle of its cause or its effect provided that both the cause and the effect are not actually detectable. Smoke is only a sign of fire to the extent that fire is not actually perceived along with the smoke: but smoke can be a sign-vehicle standing for a non-visible fire, provided that a social rule has necessarily and usually associated smoke with fire.

The second case is one in which a human being performs acts that are perceived by someone as signalling devices, revealing something else, even if the sender is unaware of the revelative property of his behavior. A typical example is gestural behavior. Under some conditions it is perfectly possible to detect the cultural origin of a gesturer because his gestures have a clear connotative capacity. Even if we do not know the socialized meanings of those gestures we can at any rate recognize the gesturer as Italian, Jew, Anglo-Saxon and so on (see Efron, 1941) just as almost everybody is able to recognize a Chinese or German speaker as such even if he does not know Chinese or German. These behaviors are able to signify even though the sender does not attribute such a capacity to them.

One might assume that this case is similar to that of medical symptoms: provided there is a rule assigning a cultural origin to certain gestural styles, those gestures will be understood as signs, independently of the will of the sender. But no one can escape the suspicion that, as long as the gesture is performed by a human being, there is an underlying significative intention. So in this case our example is complicated by the fact that we are dealing with something which has strong links with communicational practice. If in the case of symptoms it was easy to recognize a signification relationship without any suspicion of actual communication, in this second case there is always the suspicion that the subject is pretending to act unconsciously with a specially communicative intention; he may, on the other hand, want to show his communicative intention, while the addressee interprets his behavior as unconscious. Moreover, the subject can act unconsciously while the addressee attributes a misleading intention to him. And so on. This interplay of acts of awareness and unawareness, and of the attribution of voluntarity and involuntarity to the sender, generates many communicative exchanges that can give rise to an entire repertoire of mistakes, arrière pensées, double thinks and so on.

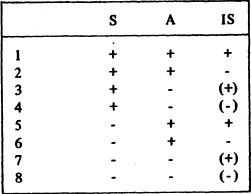

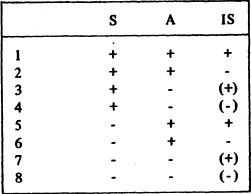

Table 1 should generate all possible understandings and misunderstandings. S stands for Sender, A for Addressee, IS for ‘the intention attributed to the Sender by the Addressee’, while + and - mean either intentional/ unintentional emission (for the Sender) or conscious/unconscious reception (for the Addressee): In case number 1, for instance, a liar intentionally shows the signs of a given sickness in order to deceive the addressee, while the addressee is quite well aware that the sender is lying. In case number 2 the deception is successful. In cases number 3 and 4 the sender intentionally emits a significant behavior which the addressee receives as a simple stimulus devoid of any intentionality: as when, in order to get rid of a boring visitor, I drum on the desk with my fingers, thus expressing nervous tension. The addressee may only perceive it as a subliminal stimulus which irritates him; in such a case he cannot attribute either intentionality or unintentionality to me (which is why + and - are put into brackets), although later he might (or might not) realize that my behavior was intentional.

Cases 1 and 2 also express the opposite of the last situation: I drum intentionally and the addressee perceives my behavior as significant, though he may or may not attribute to me a specifically significative intention. In all these cases (which could constitute a suitable combinatorial explanation of many interpersonal relations, of the type studied by Goffman (1963, 1967, 1969)), behaviors become signs because of a decision on the part of the addressee (trained by cultural convention) or of a decision on the part of the sender to stimulate in the addressee the decision to take these behaviors as signs.

If both non-human and human but unintentional events can become signs, then semiotics has extended its domain beyond a frequently fetishized threshold: that which separates signs from things and artificial signs from natural ones. But while gaining this territory, general semiotics inevitably loses its grip on another strategical position to which it had unduly laid claim. For since everything can be understood as a sign if and only if there exists a convention which allows it to stand for something else, and since some behavioral responses are not elicited by convention, stimuli cannot be regarded as signs.

According to the well-known Pavlov experiment, a dog salivates when stimulated by the ring of a bell because of a conditioned stimulus. The ring of the bell provokes salivation without any other mediation. However, from the point of view of the scientist, who knows that to every ring must correspond a salivation, the ring stands for salivation (even if the dog is not there): there is a coded correspondence between two events so that one can stand for the other. There is an old joke according to which two dogs meet in Moscow, one of them very fat and wealthy, the other pathetically emaciated. The latter asks the former: “How can you find food?”. The former zoosemiotically replies: “That’s easy. Every day, at noon, I enter the Pavlov Institute and I begin to salivate: immediately afterward a conditioned scientist arrives, rings a bell and gives me food”. In this case the scientist reacts to a stimulus but the dog establishes a sort of reversible relationship between salivation and food: it knows that to a given stimulus a given reaction must correspond and therefore the dog possesses a code. Salivation is for it the sign of the possible reaction on the part of the scientist. Unfortunately for dogs, this is not the way things are – at least within the framework of classical experiment: the sound of the bell is a stimulus for the dog, which salivates independently of any social code, while the psychologist regards the dog’s salivation as a sign (or symptom) that the stimulus has been received and has elicited the appropriate response.

To my mind, the difference between the attitude of the dog and that of the psychologist is an enlightening one: to assert that stimuli are not signs does not necessarily mean that a semiotic approach ought not to be concerned with them. Semiotics is dealing with sign-function, but a sign-function represents the correlation of two functives which (outside that correlation) are not by nature semiotic. However, insofar as – once correlated – they can acquire such a nature, they deserve some attention on the part of semioticians. There are some phenomena that could be imprudently listed among supposedly non-signifying stimuli without realizing that ‘in some respect or capacity’ they can act as signs ‘to somebody’.

For instance, the proper objects of a theory of information are not signs but rather units of transmission which can be computed quantitatively irrespective of their possible meaning, and which therefore must properly be called ‘signals’ and not ‘signs’. To assert that these signals are of no importance for a semiotic approach would be rather hasty. One would then be unable to take into account the various features of the linguistic ‘significant’ face of a sign, which, although strictly organized and computatively detectable, can be independent of its meaning and only possesses an oppositional value. Semiotics here comes face to face with its lower threshold. Yet the decision as to whether or not to respect this threshold seems to me a very difficult one to make.

One must undoubtedly exclude from semiotic consideration neuro-physiological and genetic phenomena, as well as the circulation of the blood or the activity of the lungs. But what about the informational theories that view sensory phenomena as the passage of signals from peripherical nerve ends to the cerebral cortex, or genetic heredity as a coded transmission of information? Probably it would be prudent to say that neurophysiological and genetic phenomena are not a matter for semioticians, but that neurophysiological and genetic informational theories are so.

All these problems seem to suggest that one should consider this lower threshold more carefully and with greater attention, as will be done in chapter 1.

Granted that semiotics takes many of its own tools (for example the notions of information and binary choice) from disciplines dealing with this lower threshold, one can hardly exclude it from consideration without embarrassing results. The phenomena on the lower threshold should rather be isolated as indicating the point where semiotic phenomena arise from something non-semiotic, as a sort of ‘missing link’ between the universe of signals and the universe of signs.

If the term ‘culture’ is accepted in its correct anthropological sense, then we are immediately confronted with three elementary cultural phenomena which can apparently be denied the characteristic of being communicative phenomena: (a) the production and employment of objects used for transforming the relationship between man and nature; (b) kinship relations as the primary nucleus of institutionalized social relations; (c) the economic exchange of goods.

We did not choose these three phenomena by accident: not only are they the constituent phenomena of every culture (along with the birth of articulated language) but they have been singled out as the objects of various semio-anthropological studies in order to show that the whole of culture is signification and communication and that humanity and society exist only when communicative and significative relationships are established.

One must be careful to note that this type of research can be articulated through two hypotheses, of which one is comparatively ‘radical’ – a kind of ‘unnegotiable demand on the part of semiotics’ – and the other appears to be comparatively ‘moderate’.

The two hypotheses are: (i) the whole of culture must be studied as a semiotic phenomenon; (ii) all aspects of a culture can be studied as the contents of a semiotic activity. The radical hypothesis usually circulated in two extreme forms: “culture is only communication” and “culture is no more than a system of structured significations”. These formulas hint dangerously at idealism and should be changed to: “the whole of culture should be studied as a communicative phenomenon based on signification systems”. This means that not only can culture be studied in this way but – as will be seen – only by studying it in this way can certain of its fundamental mechanisms be clarified.

The difference between saying culture ‘should be studied as’ and ‘culture is’, is immediately apparent. In fact it is one thing to say that an object is essentialiter something and another to say that it can be seen sub ratione of that something.

I shall try and give a few examples. When Australopithecines used a stone to split the skull of a baboon, there was as yet no culture, even if an Australopithecine had in fact transformed an element of nature into a tool. We would say that culture is born when: (i) a thinking being establishes the new function of the stone (irrespective of whether he works on it, transforming it into a flint-stone); (ii) he calls it “a stone that serves for something” (irrespective of whether he calls it so to others, or out loud); (iii) he recognizes it as “the stone that responds to the function F and that has the name Y” (irrespective of whether he uses it as such a second time: it is sufficient that he recognizes it). (5)

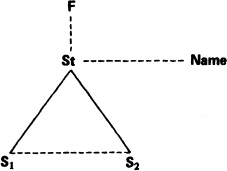

These three conditions result in a semiotic process of the following kind: In Table 2, S1 is the first stone used for the first time as a tool and S2 is another stone, different in size, color and weight from the first one. Now suppose that our Australopithecine, after having used the first stone by chance and after having discovered its possible function, comes upon a second stone (S2) some days later and recognizes it as a token, an individual occurrence of a more general model (St), which is the abstract type to which Si also refers. Encountering S2 and being able to subsume it (along with S1) under type St, our Australopithecine regards it as the sign-vehicle of a possible function F. S1 and S2, as tokens of the type St, are significant forms referring back to and standing for F. According to a typical characteristic of every sign, S1 and S2 have not only to be considered as the sign-vehicle of a possible meaning (the function F): insofar as both stand for F (and vice versa) both are simultaneously (and from different points of view) the sign-vehicle and meaning of F, following a law of total reversibility.

The possibility of giving a name to the type-stone (and to everyone of its occurrence) adds a new semiotic dimension to our diagram. As we will see in the pages devoted to the relationship between denotation and connotation (2.3) the name denotes the type-stone as its meaning but immediately connotes the function of which the object-stone (or the type-stone) is the signifier.

In principle this represents no more than a signification system and does not imply an actual process of communication (except that it is impossible to conceive of the institution of such significant relationships if not for communicative purposes).

However, these conditions do not even imply that two human beings actually exist: the situation is equally possible in the case of a solitary, shipwrecked Robinson Crusoe. It is necessary, however, that whoever uses the stone for the first time should consider the possibility of passing on the information he has acquired to himself the next day, and in order to do this should elaborate a mnemonic device, a significant relationship between object and function. A single use of the stone is not culture. To establish how the function can be repeated and to transmit this information from today’s solitary shipwrecked man to the same man tomorrow, is culture. The solitary man becomes both transmitter and receiver of a communication (on the basis of a very elementary code). It is clear that a definition such as this (in its totally simple terms) can imply an identification of thought and language: it is a question of saying, as Peirce does (5.470-480) that even ideas are signs. But the problem appears in its extreme form only if one considers the extreme example of a shipwrecked individual communicating with himself. As soon as there are two individuals, one can translate the problem into terms not of ideas but of observable sign-vehicles.

The moment that communication occurs between two men, one might well imagine that what can be observed is the verbal or pictographic sign with which the sender communicates to the addressee the object-stone and its possible function by means of a name (for example: /headsplitter/ or /weapon/). But with this we only arrive at our second hypothesis: the cultural object has become the content of a possible verbal communication. The primary hypothesis instead presupposes that the sender could communicate the function of the object even without necessarily involving the verbal name, by merely showing the object. It thus supposes that once the possible use of the stone has been conceptualized, the stone itself becomes the concrete sign of its virtual use. Thus it is a question of stating (Barthes, 1964 a) that once society exists every function is automatically transformed into a sign of that function. This is possible once culture exists. But culture exists only because this is possible.

We will move on now to phenomena such as economic exchange. We must above all eliminate the ambiguity whereby every ‘exchange’ would be ‘communication’ (just as some think that every communication is a ‘transfer’). True, as every communication implies an exchange of signals (just as the exchange of signals implies the transfer of energy); but there are exchanges such as those of goods (or of women) which are exchanges not only of signals but also of consumable physical bodies. It is possible to consider the exchange of commodities as a semiotic phenomenon (Rossi-Landi, 1968) not because the exchange of goods implies a physical exchange, but because in the exchange the use value of the goods is transformed into their exchange value – and therefore a process of signification or symbolization takes place, this later being perfected by the appearance of money, which stands for something else.

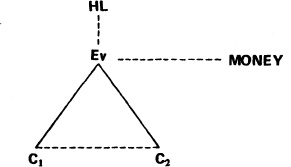

The economic relationships ruling the exchange of commodities (as described in the first book of Das Kapital by Karl Marx) may be represented in the same way as was the sign-function performed by the tool-stone (Table 3).

In Table 3, C1 and C2 are two commodities devoid of any use value (this having been semiotically represented in Table 2). In the first book of Das Kapital Marx not only shows how all commodities, in a general exchange system, can become signs standing for other commodities: he also suggests that this relation of mutual significance is made possible because the commodities system is structured by means of oppositions (similar to those which linguistics has elaborated in order to describe – for example – the structure of phonological systems). Within this system //Commodity number 1//) becomes the Commodity in which the exchange value of «Commodity number 2» is expressed («Commodity number 2» being the item of which the exchange value is expressed by //Commodity number 1.//(6) This significant relationship is made possible by the cultural existence of an exchange parameter that we can record as Ev (exchange value). If in a use value system all the items referred back to a function F (corresponding to the use value) in an exchange value system Ev refers back to the quantity of human labor necessary to the production of both C1 and C2 (this parameter being recorded as HL). All these items can be correlated, in a more sophisticated cultural system, with the universal equivalent, money (which corresponds in some respects to the cultural name standing for both commodities and their abstract and ‘type’ equivalents, HL and Ev). The only difference between a coin (as sign-vehicle) and a word is that the word can be reproduced without economic effort while a coin is an irreproducible item (which shares some of the characters of its commodity-object). This simply means that there are different kinds of signs which must also be differentiated according to the economic value of their expression-matter. The Marxist analysis also shows that the semiotic diagram ruling a capitalistic economy differentiates both HL and Ev (which are mutually equivalent) from a third element, the salary received by the worker who performs HL. This gap between HL, Ev and Salary constitutes the plus value. But this fact, highly significant from the point of view of an economic enquiry, does not contradict our semiotic model; on the contrary it shows how semiotics can clarify certain aspects of cultural life; and how, from a certain point of view, a scientific approach to economics consists in discovering the one-sidedness of some surface semiotic codes, that is their ideological quality (see 3.9.).

If one turns back to Table 2 one realizes that even that was a one-sided representation of more complex relationships. As a matter of fact a stone has not only that particular function F (head-splitting), but many others too; and a possible global semiotic system (that is, a representation of a culture in its totality) must take into account every possible use value (that is, every possible semantic content or meaning) or a given object – thus recording every kind of functional synonymy and homonymy.

Let us now consider the exchange of women. In what sense can this be considered a symbolic process? In this context women would appear to be physical objects to be used through physiological operations (to be consumed as in the case of food and other goods). However, if the woman were merely the physical body with which the husband enters into sexual relations in order to produce sons, it could not then be explained why every man does not copulate with every woman. Why is man obliged by certain conventions to choose one (or more, according to the custom) following very precise and inflexible rules of choice? Because it is only a woman’s symbolic value which puts her in opposition, within the system, to other women. The woman, the moment she becomes ‘wife’, is no longer merely a physical body: she is a sign which connotes a system of social obligations (Lévi-Strauss, 1947).

So it is clear how my first hypothesis makes a general theory of culture out of semiotics and in the final analysis makes semiotics a substitute for cultural anthropology. But to reduce the whole of culture to semiotics does not mean that one has to reduce the whole of material life to pure mental events. To look at the whole of culture sub specie semiotica is not to say that culture is only communication and signification but that it can be understood more thoroughly if it is seen from the semiotic point of view. And that objects, behavior and relationships of production and value function as such socially precisely because they obey semiotic laws. As for the moderate hypothesis, it simply means that every aspect of culture becomes a semantic unit.

To say that a class of objects (for example «automobile») becomes a semantic entity insofar as it is signified by means of the sign=vehicle /automobile/ will not get us very far. It is obvious that semiotics is also concerned with sodium chloride (which is not a cultural but a natural entity) the moment it is seen as the meaning of the sign-vehicle /salt/ (and vice versa).

But our second hypothesis implicitly suggests something more, i.e., that the systems of meanings (understood as systems of cultural units) are organized as structures (semantic fields and axes) which follow the same semiotic rules as were set out for the structures of the sign-vehicle. In other words, «automobile» is not only a semantic entity once it is correlated with the sign-vehicle /automobile/. It is a semantic unit as soon as it is arranged in an axis of oppositions and relationships with other semantic units such as «carriage», «bicycle» or «feet» (in the opposition “by car” vs. “on foot”). In this sense there is at least one way of considering all cultural phenomena on the semiotic level: everything which cannot be studied any other way in semiotics is studied at the level of structural semantics. But the problem is not that simple. An automobile can be considered on different levels (from different points of view): (a) the physical level (it has a weight, is made of a certain metal and other materials); (b) the mechanical level (it functions and fulfills a certain function on the basis of certain laws); (c) the economic level (it has an exchange value, a set price); (d) the social level (it indicates a certain social status); (e) the semantic level (it is not only an object as such but a cultural unit inserted into a system of cultural units with which it enters into certain relationships which are studied by structural semantics, relationships which remain the same even if the sign-vehicles with which we indicate them are changed; even – that is – if instead of /automobile/ we were to say /car/ or /coche/).

Let us now return to level (d), i.e. to the social level. If an automobile (as an individual concrete object) indicates a certain social status, it has then acquired a symbolic value, not only when it is an abstract class signified as the content of a verbal or iconic communication (that is when the semantic unit «automobile» is indicated by means of the sign-vehicle /car/ or /voiture/ or /bagnole/). It also has symbolic value when it is used an object. In other words, the object //automobile// becomes the sign-vehicle of a semantic unit which is not only «automobile» but, for example, «speed» or «convenience» or «wealth». The object //automobile// also becomes the sign-vehicle for its possible use. On the social level the object, as object, already has its own sign function, and therefore a semiotic nature. Thus the second hypothesis, according to which cultural phenomena are the contents of a possible signification, already refers back to the first hypothesis, according to which cultural phenomena must be seen as significant devices.

Now let us examine level (c) – the economic level. We have seen that an object, on the basis of its exchange value, can become the sign-vehicle of other objects. It is only because all goods acquire a position in the system, by means of which they are in opposition to other goods, that it is possible to establish a code of goods in which one semantic axis is made to correspond to another semantic axis, and the goods of the first axis become the sign-vehicles for the goods of the second axis, which in turn become their meaning. Similarly even in verbal language a sign-vehicle (/automobile/) can become the meaning of another sign-vehicle (/car/) within a metalinguistic discussion such as we have been pursuing in the preceding pages. The second hypothesis refers therefore to the first hypothesis. In culture every entity can become a semiotic phenomenon. The laws of signification are the laws of culture. For this reason culture allows a continuous process of communicative exchanges, in so far as it subsists as a system of systems of signification. Culture can be studied completely under a semiotic profile.

But there is a third sort of threshold, an epistemological one, which does not depend on the definition of the semiotic object but rather on the definition of the theoretical ‘purity’ of the discipline itself. In other words the semiotician should always question both his object and his categories in order to decide whether he is dealing with the abstract theory of the pure competence of an ideal sign-producer (a competence which can be posited in an axiomatic and highly formalized way) or whether he is concerned with a social phenomenon subject to changes and restructuring, resembling a network of intertwined partial and transitory competences rather than a crystal-like and unchanging model. I would put the matter this way: the object of semiotics may somewhat resemble (i) either the surface of the sea, where, independently of the continuous movement of water molecules and the interplay of submarine streams, there is a sort of average resulting form which is called the Sea, (ii) or a carefully ordered landscape, where human intervention continuously changes the form of settlements, dwellings, plantations, canals and so on. If one accepts the second hypothesis, which constitutes the epistemological assumption underlying this book, one must also accept another condition of the semiotic approach which will not be like exploring the sea, where a ship’s wake disappears as soon as it has passed, but more like exploring a forest where cart-trails or footprints do modify the explored landscape, so that the description the explorer gives of it must also take into account the ecological variations that he has produced.

According to the theory of codes and sign production that I intend to propose, it will be clear that the semiotic approach is ruled by a sort of indeterminacy principle: in so far as signifying and communicating are social functions that determine both social organization and social evolution, to ‘speak’ about ‘speaking’, to signify signification or to communicate about communication cannot but influence the universe of speaking, signifying and communicating.

The semiotic approach to the phenomenon of ‘semiosis’ must be characterized by this kind of awareness of its own limits. Frequently to be really ‘scientific’ means not pretending to be more ‘scientific’ than the situation allows. In the ‘human’ sciences one often finds an ‘ideological fallacy’ common to many scientific approaches, which consists in believing that one’s own approach is not ideological because it succeeds in being ‘objective’ and ‘neutral’. For my own part, I share the same skeptical opinion that all enquiry is ‘motivated’. Theoretical research is a form of social practice. Eveiybody who wants to know something wants to know it in order to do something. If he claims that he wants to know it only in order ‘to know’ and not in order ‘to do’ it means that he wants to know it in order to do nothing, which is in fact a surreptitious way of doing something, i.e. leaving the world just as it is (or as his approach assumes that it ought to be).

Ceteris paribus, I think that it is more ‘scientific’ not to conceal my own motivations, so as to spare my readers any ‘scientific’ delusions. If semiotics is a theory, then it should be a theory that permits a continuous critical intervention in semiotic phenomena. Since people speak, to explain why and how they speak cannot help but determine their future way of speaking. At any rate, I can hardly deny that it determines my own way of speaking.

1. There is some discussion as to whether the discipline should be called Semiotics or Semiology. ‘Semiology’ with reference to Saussure’s definition; ‘Semiotics’ or ‘semiotic’ with reference to those of Peirce’s and Morris’. Furthermore one could presumably speak of semiology with reference to a general discipline which studies signs, and regards linguistic signs as no more than a special area; but Barthes (1964 a) has turned Saussure’s definition upside down by viewing semiology as a translinguistics which examines all sign systems with reference to linguistic laws.

So it would seem that anyone inclining toward a study of sign systems that has no necessary dependence on linguistics must speak of semiotics. On the other hand the fact that Barthes has interpreted Saussure’s suggestion in the way he has does not prevent us from going back to the original meaning. However, here I have decided to adopt the formula ‘semiotics’ once and for all, without paying attention to arguments about the philosophical and methodological implications of the two terms, thus complying with the decision taken in January 1969 in Paris by an international committee which brought into existence the International Association for Semiotic Studies. Sticking to Ockham’s razor, some other important distinctions are not taken into account in this book. Hjelmslev (1943), for instance, proposes to divide semiotics into (a) scientific semiotic and (b) non-scientific semiotic, both studied by (c) metasemiotic. A metasemiotic studying a non-scientific semiotic is a semiology, whose terminology is studied by a metasemiology. Insofar as there also exists a connotative semiotic, there will likewise be a meta-(connotative) semiotic. This division, however, does not take into account (for historical reasons) many new approaches to significant and communicative phenomena. For instance, Hjelmslev called ‘connotators’ such phenomena as tones, registers, gestures which, not being at that time the object of a scientific semiotics, should have been studied by a metasemiology, while today the same phenomena fall within the domain of paralinguistics, which would seem to be a ‘scientific semiotic’. Hjelmslev’s great credit was that of having emphasized that there is no object which is not illuminated by linguistic (and semiotic) theory. Even if his semiotic hierarchy could be reformulated, his proposals must be constantly kept in mind. Following Hjelmslev, Metz (1966 b) had proposed calling all the formalizations of the natural sciences ‘semiotics’ and those of the human sciences ‘semiology’. Greimas (1970) suggests applying the term ‘semiotics’ to the sciences of expression and the term ‘semiology’ to the sciences of content. Various other classifications have been proposed, such as those of Peirce and Morris, or the distinction proposed by the Soviet school of Tartu between ‘primary modelling systems’ (the proper object of linguistics) and ‘secondary modelling systems’. Some other classifications can be found in the discussion published in Approaches to Semiotics (Sebeok, Bateson, Hayes, 1964) such as the one by Goffman: (a) detective models (indices); (b) semantic codes; (c) communicative systems in the strict sense; (d) social relations; (e) phenomena of interaction between speakers. See also Sebeok (1973) and Garroni (1973).

2. But see the objections raised to this book by Robert M.W. Dixon in his review in Linguistics, 5, where he observes that even mathematical formulae, considered ‘universal’ by the author, are abstractions from Indo-European syntactical models, and that they can therefore be understood only by someone who already knows the codes of certain natural languages.

3. This concerns the need for a hyperformalized language, formed by empty signs, and adapted to the description of all semiotic possibilities. As for this project, proposed by modern semiologists, see Julia Kristeva, “L’expansion de la sémiotique” (1967). She refers to the research of the Russian Linzbach and predicts an axiomatics through which “semiotics will be built up on the corpse of linguistics, a death already predicted by Linzbach, and one to which linguistics will become resigned after having prepared the ground for semiotics, demonstrating the isomorphism of semiotic practices with the other complexes of our universe.” Semiotics will therefore be presented as the axiomatic meeting-place of all possible knowledge, including arts and sciences. This proposal is developed by Kristeva in “Pour une semiologie des paragrammes” (1967) and in “Distance et anti-representation” (1968), where she introduces Linnart Mall, “Une approche possible du Sunyayada”, whose study of the “zero-logical subject’ and of the notion of ‘emptiness’ in ancient Buddhist texts is curiously reminiscent of Lacan’s ‘vide’ But it must be pointed out that the whole of this axiomatic program refers semiotics back to the characteristica universalis of Leibniz, and from Leibniz back to the late medieval artes combinatoriae, and to Lullo.

4. One should establish from this point on what a convention is. It is not so difficult to explain how someone can posit the conventional relationship between a red spot and measles: one can use verbal language as a metalinguistic device. But what about those conventions that cannot rely upon a previous metalanguage? Paragraphs 3.6.7. to 3.6.9. (about the mode of sign production called ‘invention’) will be devoted to this subject. For a preliminary and satisfactory notion of ‘convention’ let us assume for the time being the one proposed by Lewis, 1969.

5. Whether or not all this applies to the Australopithecines we do not know. It is sufficient to maintain that all this must apply to the first being which performed a semiotic behavior. This could mean – as Piaget (1968, p. 79) suggests – that intelligence precedes ‘language’. But this does not mean that intelligence precedes semiosis. If the equation ‘semiosis=verbal language’ is eliminated, one can view intelligence and signification as a single process.

6. Since this is a book on semiotics and not only on linguistics, I will be obliged at times to quote a non-verbal device as the sign-vehicle of a given cultural content (see chapter 2). Having adopted the decision of representing the sign-vehicles between slashes (/xxx/), and since in a book even the quotation of an object needs to be realized through a word, let me assume that when something which is not a word is taken as a sign-vehicle and is therefore represented by a word, this corresponding word will be written in italics between double slashes (//xxx//). Double slashes thus mean «the object usually corresponding to this word». Thus /automobile/ represents the word ‘automobile’, while //automobile// represents the object usually called /automobile/.