Chapter 1

So, You Want to Invest in Shares

IN THIS CHAPTER

Timing your investments

Timing your investments

Defining a share

Defining a share

Buying for profit

Buying for profit

Discovering the five big pluses

Discovering the five big pluses

Reducing risk

Reducing risk

If you’ve been hearing about the sharemarket for a long time, but you’re only now taking the plunge, welcome aboard. There simply isn’t a better place to invest money.

You’re probably already familiar with shares and how they generate long-term wealth. In that case, you may want to skim through Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 quickly and then move on to Chapter 3 for an in-depth view of investment strategies. If that isn’t the case, you’re in the right spot to get started.

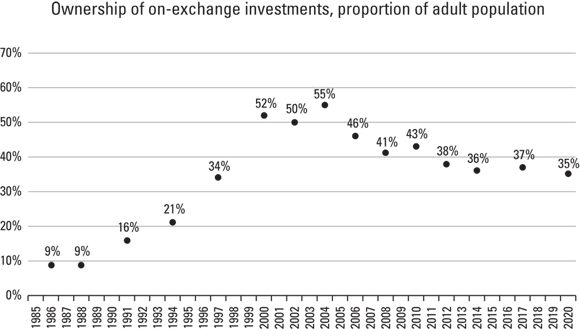

Investing Is All about Timing

Australians are among the world’s most avid share investors, with the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) reporting in its 2020 Australian Investor Study that 35 per cent of the adult population, or 6.6 million people, directly own listed investments — a term that covers shares, real estate investment trusts (REITs), exchange-traded funds (ETFs), listed investment companies (LICs), listed hybrid securities and anything quoted on an exchange (the ASX and international exchanges). The figure is slightly lower than the 37 per cent of adult investors who owned on-exchange investments in the 2017 Australian Investor Study.

While this proportion has fallen from the 55 per cent that owned shares in the ASX Share Ownership Study in 2004, the ASX now looks more broadly at investing. The ASX used to compare Australia’s share ownership levels with its overseas peer-group of markets, but differences in methodology mean that it no longer does so. For example, official US data measures share ownership — directly or indirectly — by households. A survey released by polling group Gallup in April 2020 found that 55 per cent of American households reported having money invested in the sharemarket, either in an individual stock, a mutual fund or a retirement account. That figure was down from 60 per cent before the ‘Great Recession’ (what we in Australia would call the global financial crisis or GFC) of December 2007 to June 2009.

The ASX’s 2020 Australian Investor Study found that:

- 9 million adult Australians own investments outside of superannuation and their primary residence.

- Of those 9 million, 6.6 million own on-exchange investments, making them the most widely used type of investment. Other options invested in included investment properties (residential or commercial), unlisted managed funds and term deposits.

- Of the 6.6 million who own on-exchange investments, 58 per cent own shares listed on an Australian exchange and 15 per cent own shares listed on an international exchange.

- 15 per cent of Australian investors own ETFs.

In addition to this data, Australian investors own a further $1.2 trillion worth of shares (domestic shares of $595 billion and international shares of $600 billion) managed for them in their superannuation accounts. So, chances are you’ve dipped your toes in the sharemarket pond (at least indirectly) before picking up this book.

Figure 1-1 shows share investing trends in Australia from 1986 to 2020.

Source: 2020 Australian Investment Study, Australian Securities Exchange

Note: Where earlier data relies on ownership of shares, the studies since 2014 have used ownership of all listed investment products offered at ASX, which includes shares.

FIGURE 1-1: Ownership of on-exchange investments in Australia 1986–2020.

‘Hang on,’ you say, ‘doesn’t the sharemarket crash and correct regularly? What about the headlines that talk of billions of dollars of investors’ savings being wiped off the value of the sharemarket in a day?’ (See the sidebar ‘What just happened? The COVID-19 crash at a glance’, later in this chapter.)

Occasionally, that happens. No-one who goes into the sharemarket can afford to ignore the fact that, from time to time, share prices can suddenly move in an extreme fashion — sometimes up, sometimes down. When share prices move down, they attract media headlines. However, what the headlines don’t tell you is that on most other days, the sharemarket is quietly adding billions — or even just millions — of dollars in value to investors’ savings.

And since 1950, according to research firm Andex Charts, the S&P/ASX All Ordinaries Accumulation Index (which assumes all dividends are reinvested) has delivered an average return of 11.8 per cent a year, for a real (after-inflation) return of 6.9 per cent a year. In the 30 years to 31 December 2019, says Andex Charts, the same index has earned 9.2 per cent a year, for a real return of 6.7 per cent a year.

In 1985, the Australian stock market was valued at $76 billion, about one-third of Australia’s gross domestic product (GDP — the amount of goods and services produced in the Australian economy). In April 2020, the stock market was valued at $1,760 billion — down from $2,200 billion before the COVID-19 crash — while GDP was about $2,070 billion. Although the nation’s economic output has grown just over nine times since 1985, the value of the stock market has grown by almost 29 times.

Investing is about building wealth for yourself so that you can have the lifestyle you want, educate and give your children a good start in life, and ensure that you have a well-funded, carefree retirement.

When you invest in shares, you get a number of advantages, such as:

- The opportunity to buy a part of a company for a small outlay of cash

- A share of the company’s profits through the payment of dividends (a portion of company profits distributed to investors)

- The company’s retained earnings working for you as well

- The possibility of capital gains as the price rises over time

- An easy way to buy and sell assets

The sharemarket has an exaggerated reputation as a sort of Wild West for money and, therefore, can be a daunting place for a new investor. The sharemarket is a huge and impersonal financial institution; yet, paradoxically, it’s also a market that’s alive with every human emotion — greed and fear, hope and defeat, elation and despair. The sharemarket can be a trap for fools or a place to create enormous wealth. Those who work in the industry see daily the best and worst of human behaviour. And you thought the sharemarket was simply a market in which shares were bought and sold!

Of course, the sharemarket is precisely that — a place for buying and selling shares. Approximately $5 billion worth of shares change hands every trading day (that surged to $10.5 billion in the frenzy of February–March 2020). Shares are revalued in price every minute, reacting to supply, demand, news and sentiment, or the way that investors collectively feel about the likely direction of the market. The sharemarket also works to mobilise your money and channel your hard-earned funds to the companies that put those funds at risk for the possibility of gain. That ever-present element of risk, which can’t be neutralised, makes the sharemarket a dangerous place for the unwary. Although you take a risk with any kind of investment, being forearmed with sound knowledge of what you’re getting into and forewarned about potential traps are absolutely essential for your survival in the market.

Finding Out What a Share Is

Companies divide their capital into millions (sometimes billions) of units known as shares. Each share is a unit of ownership in the company, in its assets and in its profits. Companies issue shares through the sharemarket to raise funds for their operating needs; investors buy those shares, expecting capital gains and dividends. If the company fails, a share is also an entitlement to a portion of whatever assets remain after all the company’s liabilities are paid. The following is a partial list of share definitions.

A share is

- Technically a loan to a company, although the loan is never repaid. The loan is borrowed permanently — like the car keys, if you have teenagers.

- A financial asset that the shareholders of a company own, as opposed to the real assets of the company — its land, buildings and the machines and equipment that its workers use to produce goods and services. Tangible assets generate income; financial assets allocate that income. When you buy a share, what you’re really buying is a share of a future flow of profits.

- A right to part ownership, proportional to the number of shares owned. In law, the part of the assets of a company owned by shareholders is called equity (the shareholders’ funds). Shares are sometimes called equities. They are also called securities because they signify ownership with certain rights.

Now you know what you’re getting when you buy shares. You become a part-owner of the company. As a shareholder, you have the right to vote on the company’s major decisions. Saying ‘I’m a part-owner of Qantas’ sounds so much more impressive than ‘I’m a Qantas Frequent Flyer member’. Just remember not to insist on sitting in with the pilots; as a shareholder, your ownership of Qantas is a bit more arm’s-length than that. That’s what shares were invented to do — separate the ownership of the company from those who manage and run it.

Sharing the profit, not the loss

When you’re a shareholder in a company, you can sit back and watch as the company earns, hopefully, a profit on its activities. After paying the costs of doing business — raw materials, wages, interest on any loans and other items — the company distributes a portion of the profit to you and other shareholders; the rest is retained for reinvestment. This profit share is called a dividend, which is a specified amount paid every six months on each share issued by the company. Shareholders receive a dividend payment for the total amount earned on their shareholding.

If the company takes a loss, shareholders are not required to make up the difference. All this means is they won’t receive a dividend payment that year, unless the company dips into its reserves to pay (for more on dividends, see the section ‘Dividend income’ later in this chapter). However, if a company has too many non-profitable years it can go under, taking both its original investment and its chances of capital growth with it.

Companies that offer shares to the public are traded on the sharemarket as limited companies, which means the liability of the shareholders is limited to their original investment. This original investment is all they can lose. Suits for damages come out of shareholders’ equity, which may lower profits, but individual investors aren’t liable. Again, shareholders won’t be happy if the company continues to lose money this way.

Understanding the market in sharemarket

Shares aren’t much good to you without a market in which to trade them. The sharemarket brings together everybody who owns shares — or would like to own shares — and lets them trade among themselves. At any time, anybody with money can buy some shares.

The sharemarket is a matchmaker for money and shares. If you want to buy some shares, you place a buying order on the market and wait for someone to sell you the amount you want. If you want to sell, you put your shares up for sale and wait for interested buyers to beat a path to your door.

The trouble with the matchmaker analogy is that some people really do fall in love with their shares. (I talk about this more in Chapter 7.) Just as in real love, their feelings can blind them to the imperfections of the loved one.

Because shares are revalued constantly, the total value of a portfolio of shares, which is a collection of shares in different companies, fluctuates from day to day. Some days the portfolio loses value. But over time, a good share portfolio shrugs off the volatility in prices and begins to create wealth for its owner. The more time you give the sharemarket to perform this task, the more wealth the sharemarket can create.

Buying Shares to Get a Return

Shares create wealth. As companies issue shares and prosper, their profits increase and so does the value of their shares. Because the price of a share is tied to a company’s profitability, the value of the share is expected to rise when the company is successful. In other words, higher-quality shares usually cost more.

Earning a profit

Successful companies have successful shares because investors want them. In the sharemarket, buyers of sought-after shares pay higher prices to tempt the people who own the shares to part with them. Increasing prices is the main way in which shares create wealth. The other way is by paying an income or dividend, although not all shares do this. A share can be a successful wealth creator without paying an income.

As a company earns a profit, some of the profit is paid to the company’s owners in the form of dividends. The company also retains some of the profit. Assuming that the company’s earnings grow, the principle of compound interest starts to apply (see Chapter 3 for more on how compound interest works). The retained earnings grow, and the return on the invested capital grows as well. That’s how companies grow in value.

Ideally, you buy a share because you believe that share is going to rise in price. If the share does rise in price, and you sell the share for more than you paid, you have made a capital gain. Of course, the opposite situation, a capital loss, can and does occur — if you’ve chosen badly, or had bad luck. These bad-luck shares, in the technical jargon of the sharemarket, are known as dogs. The simple trick to succeeding on the sharemarket is to make sure that you have more of the former experience than the latter!

When creating wealth, shares consistently outperform many other investments. Occasionally you may see comparisons with esoteric assets, such as thoroughbreds, or art, or wine, which imply that these assets are better earners than shares. However, these are not mainstream assets, and the comparison is usually misleading. The original investment was probably extremely hard to secure and not as accessible, and not as liquid (easily bought and sold) as shares.

Of the mainstream asset classes, in terms of creating wealth over the long term, shares usually outdo property and outperform bonds (loan investments bearing a fixed rate of interest) — especially once the impact of franking credits (see Chapter 10) is taken into account.

Investing carefully to avoid a loss

Shares offer a higher return compared to other investments, but they also have a correspondingly higher risk. Risk and return always go together — an inescapable fact of investment, as I discuss in Chapter 4. The prices of shares fluctuate much more than those of property, while bonds are relatively stable in price. The major risk with shares is that, if you have to sell your shares for whatever reason, they may, at that time, be selling for less than you bought them. Or they may be selling for a lot more. This is the gamble you take.

Everybody who has money faces the decision of what to do with it. The unavoidable fact is that anywhere you place money, you face a risk that all or part of that money may be lost, either physically or hypothetically, in terms of its value. The simplest strategy is to deposit your money in a bank and leave it there. However, when you take the money out in the future, inflation (the rate of change in prices of everyday items) may decrease its buying power.

Risk is merely the other side of performance. You can’t have high returns without running some risk. You can lower risk through the use of diversification — the spreading of your invested funds across a range of assets, as explained in Chapter 5.

Making the Most of Share Investing

Investing in shares offers five big pluses. The first two pluses that I discuss in this section are the most critically important. The other three pluses are bonuses, one literally so.

Capital growth

As a company’s revenue, profits and the value of its assets rise, so does the market price of its shares. Subjective factors, such as the market’s perception of the company’s prospects, also play a part in this process. After you’ve looked through this book, you’ll know how to put together a share portfolio that makes the most of this crucial ingredient — capital growth.

Dividend income

Shares may generate for their owners an income, which is called a dividend (a portion of company profits distributed to investors). The dividend is another important method for generating investor wealth. The dividend is paid in two portions — an interim dividend for the first six months of the financial year, and a final dividend for the second half. The two amounts make up the annual dividend. Not every company pays a dividend, but the paying of dividends is a vital part of becoming a member of that elite group of shares known as blue chips.

Shareholder discounts

Recently another reason for owning shares — or, more correctly, a bonus for shareholders — has emerged in the form of the discounts companies offer to shareholders on their goods and services. Many companies offer some form of discount, and the number of companies making these offers is growing. These businesses realise that any inducement they can give people to buy their shares makes good marketing sense. Shareholder perks range from holiday deals to wine, shopping and banking discounts. For example, vitamins and supplements maker Blackmores offers shareholders a 30 per cent discount on purchases of some of its range, while Event Group shareholders can get discounted accommodation and dining at some of its Rydges, Atura or QT hotels, as well as discounts at Thredbo Alpine Resort and at the company’s Event Cinemas, Greater Union, BCC and GU Film House cinemas.

Liquidity

A major attraction of shares as an asset class is that they are extremely liquid, meaning that you can easily buy and sell them. Through your broker’s interface to the stock exchange’s trading system, ASX Trade, virtually any number of shares put on the market by a seller can be matched with a buyer for that number of shares. Some shares are less liquid than others; therefore, if you buy unpopular shares, they may be hard to sell.

Divisibility

A share portfolio is easily divisible. If you, the shareholder, need to raise money by selling some shares, you can sell any number to raise any amount. Divisibility is a major attraction of shares as compared to property. You can’t saw off your lounge room to sell it, but you can sell 500 Telstra shares with one phone call — or with the click of a mouse.

Guarding Against Risk

Shares are the riskiest of the major asset classes because no guarantees exist as to the likelihood of capital gains. Any investor approaching the sharemarket must accept this higher degree of risk.

You can minimise but never avoid the risk that accompanies investing in shares. Share investment is riskier than alternative investments, but after you discover how to keep that risk under control, you can use this knowledge to build wealth for you and your family. I discuss the possible risks you can encounter and how to minimise their effects in Chapter 4.

The unique qualities of shares or stocks (the terms are used interchangeably in Australia) as financial assets make the sharemarket the best and most reliable long-term generator of personal wealth available to investors. Since 1900, according to AMP Capital, Australian shares have earned a return of approximately 11.5 per cent a year, split fairly evenly (48 per cent to 52 per cent) between capital growth and dividend income respectively.

The unique qualities of shares or stocks (the terms are used interchangeably in Australia) as financial assets make the sharemarket the best and most reliable long-term generator of personal wealth available to investors. Since 1900, according to AMP Capital, Australian shares have earned a return of approximately 11.5 per cent a year, split fairly evenly (48 per cent to 52 per cent) between capital growth and dividend income respectively. Franking credits are not dividends paid directly to an investor but arise through the system of dividend imputation, in which shareholders receive a rebate for the tax the company has already paid on its profit. The flow of franking credits from a share portfolio can reduce, and in some cases abolish, your tax liability. (I look at dividend imputation in detail in

Franking credits are not dividends paid directly to an investor but arise through the system of dividend imputation, in which shareholders receive a rebate for the tax the company has already paid on its profit. The flow of franking credits from a share portfolio can reduce, and in some cases abolish, your tax liability. (I look at dividend imputation in detail in