At the heart of low self-esteem lie negative beliefs about the self. These may seem like statements of fact, in the same way that your height and weight and where you live are facts. Unless you are lying (you would like to be thought taller or thinner than you really are; you would prefer people to think you live in a more desirable part of the city), or not in possession of the information you would need to give an accurate account (you have not measured or weighed yourself recently; you have only just moved to a new home and have trouble recalling the address), then statements of fact like these are indisputable – and, indeed, their truth can easily be checked and verified by you and other people.

The same is not true of the judgments we make of ourselves and the worth we place on ourselves as people. Your view of yourself – your self-esteem – is an opinion, not a fact. And opinions can be mistaken, biased and inaccurate – or indeed, just plain wrong. Your ideas about yourself have developed as a consequence of your experiences in life. If your experiences have largely been positive and affirming, then your view of yourself is likely also to be positive and affirming. If, on the other hand, your experiences in life have largely been negative and undermining, then your view of yourself is likely to be negative and undermining.

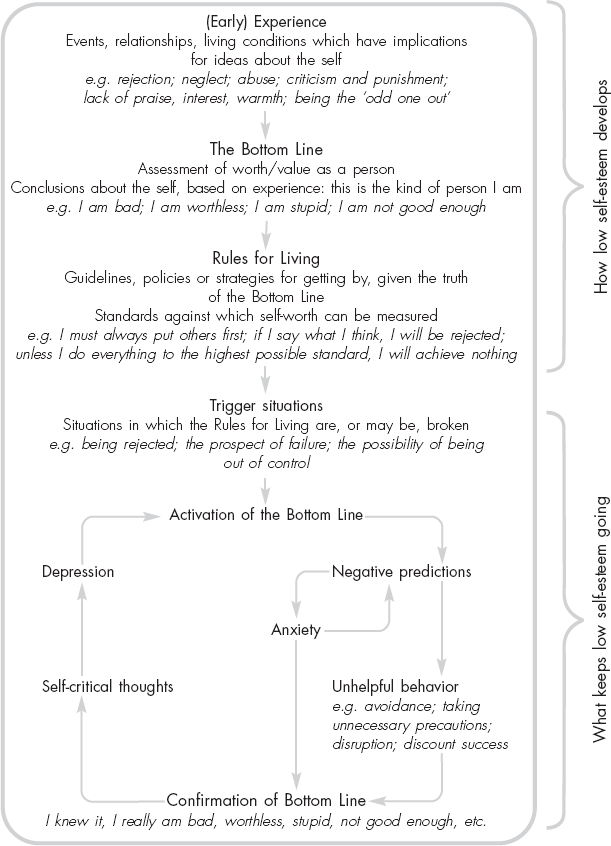

This chapter will explore how experience leads to low self-esteem and reinforces it. The processes involved in the development of low self-esteem are summarized in the top half of the flow chart on page 33. The flow chart shows how low self-esteem can be understood from a cognitive behavioral perspective. Keep it in mind as you read through the chapter. And, as you read, think about how the ideas outlined here might apply to you personally. What fits? What does not fit? What helps you to make sense of how you feel about yourself? Which of the stories told in the chapter ring bells for you? What are the experiences that have contributed to low self-esteem in your own case? What is your Bottom Line? What are your rules for living?

Keep a sheet of paper or a notebook by you, and note down anything that occurs to you as you read – ideas, memories, hunches. The aim is to help you to understand how it is that you have the view of yourself that you do, and to identify and map the experiences that have contributed to your low self-esteem. You will discover that the idea you have of yourself is an understandable reaction to what has happened to you – probably anyone who had your life experience would hold a similar view.

This understanding is the first step to change. You will begin to see how conclusions you reached about yourself (perhaps many years ago) have influenced how you have thought and felt and acted over time. The next chapter will help you to understand how the way you operate now keeps low self-esteem going – how well-established reaction patterns prevent you from changing your opinion of yourself. That is the main implication of this new understanding: opinions can be changed. The remaining chapters provide more detailed ideas about how to bring about change, how to undermine the old negative view of yourself and establish and strengthen a more positive, kindly, accepting alternative.

Figure 1 Low self-esteem: A map of the territory

Cognitive therapy is based on the idea that beliefs about ourselves (and indeed about other people and about life) are all learned. They have their roots in experience. Your beliefs about yourself can be seen as conclusions you have come to on the basis of what has happened to you. This means that, however unhelpful or outdated they may now be, they are nonetheless understandable – there was a time when they made perfect sense, given what was going on for you.

Learning comes from many sources – direct experience, observation, the media, listening to what people around you say and watching what they do. Crucial experiences in terms of beliefs about the self often (though not necessarily) occur early in life. What you saw and heard and experienced in childhood in your family of origin, in the society in which you lived, at school and among your peers will have influenced your thinking in ways which may have persisted to the present day. A range of different experiences may have contributed to thinking badly of yourself. Some of these are summarized below. Each is then considered in more detail.

Figure 2 Experiences contributing to low self-esteem

Early experiences:

• Systematic punishment, neglect or abuse

• Failing to meet parental standards

• Failing to meet peer group standards

• Being on the receiving end of other people’s stress or distress

• Belonging to a family or social group which is a focus for prejudice

• An absence of good things (e.g. praise, affection, warmth, interest)

• Being the ‘odd one out’ at home

• Being the ‘odd one out’ at school

Later experiences:

• Workplace intimidation or bullying, abusive relationships, persisting stress or hardship, exposure to traumatic events

Your idea of yourself and sense of your own worth may be a result of how you were treated early in life. If children are treated badly, they often assume that this reflects something bad in themselves – they must somehow have deserved it. If you were frequently punished (especially if the punishment was excessive, unpredictable or made no sense to you), if you were neglected, abandoned or abused, these experiences will have left a psychological scars. They will have influenced how you see yourself.

Briony, for example, was adopted by her father’s brother and his wife after both her parents were killed in a car crash when she was seven. Her new step-parents already had two older daughters. Briony became the family scapegoat. Everything that went wrong was blamed on her. She could do nothing right. Briony was a loving little girl, who liked to please people. She tried desperately to be good, but nothing worked. Every day she faced new punishments. She was deprived of contact with friends, made to give up music – which she loved – and was forced to do more than her fair share of work around the house. Briony became more and more confused. She could not understand why everything she did was wrong.

One night, when she was eleven, Briony’s stepfather came silently into her room in the middle of the night. He put his hand over her mouth and raped her. He told her that she was dirty and disgusting, that she had asked for it, and that if she told anyone what had happened, no one would believe her, because they all knew she was a filthy little liar. Afterwards, she crept around the house in terror. No one seemed to notice or care. Briony’s opinion of herself crystallized at that point. She was bad. Other people could see it, and would treat her accordingly.

Briony’s experiences were extreme. It is not necessary to be systematically abused in this way to develop a poor opinion of yourself. Much less extreme punishment and criticism will also leave a mark. If others treated you as if nothing you did was good enough, focused on your mistakes and weaknesses at the expense of your successes and strengths, teased or ridiculed you, put you down or made you feel small, all these experiences (even if much less intense) may have left you with the sense that there was something fundamentally wrong with you, or that you were lacking in some way.

Jesse’s father was an insurance salesman. He had never realized his ambitions to rise to a manager’s position, and put this down to the fact that his parents had failed to support him during his years at school. They had never seemed particularly interested in what he was doing, and it was easy to skip school and neglect his homework. He was determined not to make the same mistake with his own children. Every day, at the supper table, he would interrogate them about what they had learned. Everyone had to have an answer, and the answer had to be good enough.

Jesse remembered dreading the sight of his father’s car in the drive when he came home. It meant another grilling. He was sure his mind would go blank and he would be unable to think of anything to say. When this happened, his father’s face would fall in disappointment. Jesse could see that he was letting his father down. He felt he fully deserved the close questioning that followed. ‘If you can’t do better than this,’ his father would say, ‘you’ll never get anywhere in life.’ In his heart of hearts, Jesse agreed. It was clear to him that he was not good enough: he would never make it.

Children and young people can be powerfully influenced, not only by their parents’ explicit or implied standards, but also by the demands of others of the same age. Particularly during adolescence, when the sense of oneself as an independent person is coming into being, and when sexual identity is developing, the pressure to conform can be very strong. Seeing yourself as failing to make the grade in relation to standards in your peer group can be a painful experience, with lasting implications for self-esteem.

Karen, for example, was an attractive, sturdy, energetic girl who enjoyed sport and loved dancing. She grew up at a time when the ideal body shape for women was to be tall and extremely slender. Although she was not at all overweight, Karen’s natural body shape was not even close to this ideal. Her mother tried to boost her confidence by telling her that she was ‘well built’. This clumsy attempt to help her to feel OK about herself backfired. ‘Well built’ was not what she was supposed to be. Karen’s friends were all passionate about fashion and spent hours shopping and trying on clothes. Karen would join them but, in the shared changing rooms common at the time, felt excruciatingly awkward and self-conscious. Every mirror showed how far her body failed to meet the ideal. Her broad shoulders and rounded hips were just completely wrong.

Karen decided to diet. In the first couple of weeks, she lost several pounds. Her friends thought she looked great. Karen was delighted. She continued to restrict her eating and to lose weight. But somehow, no matter how she tried, she could never be thin enough. And she was constantly hungry. In the end, she gave in and began to eat normally again, and indeed to overeat. This was the beginning of a lifelong pattern of alternating dieting and overeating. Karen was never happy with her physical self. As far as she was concerned, she was fat and ugly.

Even in fundamentally loving families, with parents who at heart truly appreciate and value their children, changes in circumstances can sometimes create pressure and distress which have a lasting impact on children. Parents who are stressed, unhappy or preoccupied may have little patience for normal naughtiness, or the natural lack of self-control and skill that are a part of early childhood.

Geoff, for example, was an energetic, adventurous, curious little boy. As soon as he could walk, he had his fingers into everything. Whenever something caught his eye, he would run off to investigate it. He had very little fear and, even as a toddler, was climbing trees and plunging into deep water without a second thought. His mother used to say she needed eyes in the back of her head to keep track of him. Geoff’s parents were proud of his adventurousness and enquiring mind, and found him funny and endearing.

When he was three, however, twin babies arrived. At the same time, Geoff’s father lost his job and had to take work at a much lower rate of pay. The family moved from their house with its little garden to a small apartment on the fourth floor of a large block. With two new babies, things were chaotic. Geoff’s father felt his job loss keenly, and became morose and irritable. His mother was constantly tired. In the confined space of the apartment, there was nowhere for Geoff’s energy to go, and his interest and curiosity only created mess.

He became a target for anger and frustration. Because he was only little, he did not understand why this change had happened. He tried hard to sit quietly and keep out of trouble, but again and again ended up being shouted at and sometimes smacked. It was no longer possible to be himself without being told he was a naughty, disobedient boy and uncontrollable. Even into adulthood, whenever he encountered disapproval or criticism, he still felt the old sense of wrongness and despair – in a word, unacceptability.

It may be that your beliefs about yourself are not simply based on how you personally were treated. Sometimes low self-esteem is more a product of the way a person and his or her family lived, or his or her identity as a member of a group. If, for example, your family was very poor, if your parents had serious difficulties which meant the neighbours looked down on them, if you were a member of a racial, cultural or religious group which was a focus for hostility and contempt, you may have been contaminated by these experiences with a lasting sense of inferiority to other people.

This was true for Arran, whose story shows how a feisty, attractive child can come to believe he has nothing to contribute because his family group is rejected by the society in which he lives.

Arran was the middle one of seven children, in a family of travellers. He was brought up by his mother and his maternal grandmother and had no consistent father figure. Life was tough. There were constant financial strains, and was little permanence of any kind. Arran’s grandmother, a striking woman with brightly bleached hair, coped by drinking. Arran had clear memories of being rushed through the streets to school, his grandmother pushing two babies crammed into a buggy, the older children and another whining toddler trailing behind. Lack of money meant that all the children wore second-hand clothes, which were passed down from one to the next. Their sweatshirts were grubby, their shoes scuffed, their faces smudged, their hair standing on end. Every so often, the grandmother would stop and screech at the older children to hurry up.

What stuck in Arran’s mind was the faces of people coming in the opposite direction as they saw the family approaching. He would see their mouths twist, their frowns of disapproval, their avoidance of eye-contact. He could hear their muttered comments to one another. The same happened when they reached the school. In the playground, other children and parents gave the family a wide berth.

Arran’s grandmother, too, was well aware of other people’s stance. She was fiercely protective of the family, in her own way. She would begin shouting and swearing, calling names and screaming threats.

Throughout his schooldays, Arran felt a deep sense of shame. He saw himself as a worthless outcast, whose only defence was attack. He was constantly fighting and scuffling, failed to engage in lessons, left with no qualifications, and became involved with other young men operating on the fringes of the law. The only time he felt good about himself was when he had successfully broken the rules – stolen without being caught or beaten someone up without reprisals.

It is easy to see how painful experiences like those described above could contribute towards feeling bad, inadequate, inferior, weak or unlovable. Sometimes, however, the important experiences are less obvious. This may make how you feel about yourself a puzzle to you. Nothing so extreme happened in your childhood – how come you have so much trouble believing in your own worth?

It could be that the problem was not so much the presence of dramatically bad things, but rather an absence of the day-to-day good things that contribute to a sense of acceptability, goodness and worth. Perhaps, for example, you did not receive enough interest, enough praise and encouragement, enough warmth and affection, enough open confirmation that you were loved, wanted and valued. Perhaps in your family, although there was no actual unkindness, love and appreciation were not directly expressed. If so, this could have influenced your ideas about yourself.

Kate, for example, was brought up by elderly parents from a strict middle-class background. At heart, both were good people who tried their best to give their only daughter a good upbringing and a sound start in life. However, the values they had grown up with meant that both of them had difficulty in openly expressing affection. Their only means of showing how much they loved her was through caring for her practical needs. So, they were good at ensuring that Kate did her homework, in seeing that she ate a balanced diet, that she was well dressed and had a good range of books and toys.

As she grew older, they made sure she went to a good school, took her to girl guides and swimming lessons, and paid for her to go on holiday with friends. But they almost never touched her – there were no cuddles, no kisses or caresses, no pet names. At first, Kate was hardly aware of this. But once she began to see how openly loving other families were, she began to experience a sad emptiness at home. She did her best to change things. She would take her father’s hand as they walked along – and noticed how he would drop it as soon as he decently could. She would put her arms round her mother – and feel how she stiffened. She tried to talk about how she felt – and saw how awkward her parents looked, and how they swiftly changed the subject.

Kate concluded that their behavior towards her must reflect something about her. Her parents did their duty by her, but no more. It must mean she was fundamentally unlovable.

Another more subtle experience that can contribute to low self-esteem is the experience of being the ‘odd one out’. I mean by this someone who did not quite ‘fit’ in your family of origin. Perhaps you were an artistic child in an academic family, or an energetic, sporty child in a quiet family, or a child who loved reading and thinking in a family who were always on the go. There was nothing particularly wrong with you, or with them, but for some reason you did not match the family template or fit the family norm. It could be that you were never subject to anything more than good-natured teasing, or perhaps mild puzzlement. But sometimes people in this situation take away a sense that to be different from the norm means to be odd, unacceptable, or inferior.

Sarah was an exceptional artist. Both her parents, however, were teachers who thought that to achieve academically was the most important thing in life. They were plainly delighted with her two older brothers, who did very well at school, moved on to do well at university, and became a doctor and a lawyer. Sarah, however, was an average student. There was nothing particularly wrong with her schoolwork – she simply did not shine as her parents hoped she would.

Her real talent lay in her hands and eyes. She could draw and paint, and her collages were full of energy and colour. Sarah’s parents tried to appreciate her artistic gifts, but they saw art and craft work as essentially trivial – a waste of time. They never openly criticized her, but she could see how their faces lit up when they heard about her brothers’ achievements and could not help but contrast this with their lack of enthusiasm when she brought her artwork home. They always seemed to have more important things to do than look carefully at what she had done (‘Very nice, dear’).

Sarah’s conclusion was that she was inferior to other, cleverer people. As an adult, she found it difficult to value or take pleasure in her gifts, tended to apologize for and downgrade her work as an artist, and fell silent in the company of anyone she saw as more intelligent or educated than herself, preoccupied with self-critical thoughts.

In the same way that not fitting into one’s family of origin can make it difficult to feel good about oneself, so being in some way different from others at school can lead people to see themselves as weird, alien or inferior. Children and young people who stand out in some way from the group can be cruelly teased and excluded. For many children, to be different is to be wrong. This can be true for differences in appearance (e.g. skin colour, wearing spectacles), differences in psychological make-up (e.g. shyness, sensitivity), differences in behavior (e.g. having a different accent, being openly affectionate to parents beyond the age where this is considered cool) and differences in ability (e.g. being overtly intelligent and good at school work, being slow to learn).

Chris’s early childhood was happy. But he began to experience difficulties as soon as he went to school, because of undiagnosed dyslexia. While all the other children in the class seemed to be racing ahead with their reading and writing, he lagged behind. He just could not get the hang of it. He was assigned a teacher to give him special help, and had to keep a special home reading record which was different from everyone else’s.

Other children started to laugh at him and call him ‘thicko’ and ‘dumbo’. He compensated by becoming the class clown. He was the one who could always be relied on to get involved in silly pranks. The teachers too began to lose patience with him, and to label his difficulties laziness and attention-seeking. When his parents were summoned to the school yet again to discuss his behavior, his comment to them was: ‘What can you expect? I’m just stupid.’

Although low self-esteem is often rooted in experiences a person has had in childhood or adolescence, it is important to realize that this is not necessarily the case. Even very confident people, with strong favourable views of themselves, can have their self-esteem undermined by things that happen later in life, if these are sufficiently powerful and lasting in their effects. Examples include workplace intimidation or bullying, being trapped in an abusive marriage, being ground down by a long period of relentless stress or material hardship, and exposure to traumatic events.

Jim’s story illustrates how solid self-confidence can be undermined in this way. Jim was a fireman. As part of his job, he had attended many accidents and fires, and had been in a position on more than one occasion to save life. He had a stable, happy childhood and felt loved and valued by both his parents. He saw himself as strong and competent, able to deal with anything life might throw at him. This was why he was able to succeed and remain outgoing and cheerful despite his tough, risky and demanding job.

One day, as he was driving down a busy street, a woman stepped off the pavement immediately in front of him, and was caught under the wheels of his car. By the time he was able to stop, she had been fatally injured. Jim always carried a first aid kit, and he got out of the car to see what he could do. After a while, however, during which other people had called an ambulance and gathered round to help, he felt increasingly sick and shocked and retreated to his car.

Like many people who have suffered or witnessed horrific accidents, Jim later began to suffer symptoms of post-traumatic stress. He kept replaying the accident in his mind. He found the victim was ‘haunting’ him – he didn’t seem to be able to be able to get her out of his mind, asleep or awake. He was tormented by guilt – he should have been able to stop the car, he should have stayed with the victim to the bitter end. He was constantly tense, irritable and miserable – not at all his usual self.

Jim’s usual way of coping with difficulties was to tell himself that life goes on, that he must put it behind him and live in the present. So he tried not to think about what had happened, and to suppress his feelings. Unfortunately, this made it impossible for him to come to terms with what had happened. He began to feel that his personality had fundamentally changed, and for the worse. The fact that he had not been able to prevent the accident, that he had withdrawn to the car, and that he could not control his feelings and thoughts meant that, far from being the strong, competent person he had believed himself to be, he was actually weak and inadequate – a neurotic wreck.

These stories all show how experience shapes self-esteem. As people grow up, they take the voices of people who were important to them with them. These need not be parents’ voices. Other family members (grandparents, for example, or older siblings), teachers, child minders, friends and schoolmates – all can have a major impact on self-confidence and self-esteem. We may criticize ourselves in their exact, sharp tones, call ourselves the same unkind names, and make the same comparisons with other people and with how we ought to be. That is, the beliefs we hold about ourselves in the present day often directly reflect the messages we received as children.

Along with this, we may re-experience emotions and body sensations, and see images in our mind’s eye that were originally present at a much earlier stage. Sarah, for example, when she submitted a painting for exhibition, would hear her mother’s patient voice (‘Well, I suppose if you like it, dear’) and experience the same sinking feeling in her stomach that she experienced as a child. Geoff, when in the best of spirits and full of energy and ideas, would suddenly catch a flash in his mind’s eye of his father’s distorted, shouting, angry face and feel instantly in the wrong, inappropriate and deflated.

Why is this? Life goes on, after all. We are no longer children. We have adult experience under our belt. So how come these events, so long ago, still influence how we operate in the present day?

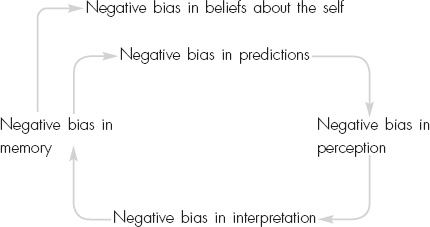

The answer lies in the way that our experiences have created a foundation for general conclusions about ourselves, judgments about ourselves as people. We can call these conclusions the ‘Bottom Line’. The Bottom Line is the view of the self that lies at the heart of low self-esteem. The Bottom Line can often be summed up in a single sentence, beginning with the words, ‘I am . . .’ Look back over the stories you have read on the last few pages. Can you spot the Bottom Lines of the people described there?

Figure 3 The Bottom Line

• Briony |

I am bad |

• Jesse |

I am not good enough |

• Karen |

I am fat and ugly |

• Geoff |

I am unacceptable |

• Arran |

I am worthless |

• Kate |

I am unlovable |

• Sarah |

I am not important; I am inferior |

• Chris |

I am stupid |

• Jim |

I am strong and competent → I am a neurotic wreck |

The distressing ideas that these people have developed about themselves flow naturally from the experiences they have been exposed to. Their opinions of themselves make perfect sense, given what has happened to them. But, when you read their stories, did you agree with those opinions? Did you think that Briony was bad, that Jesse was a failure, Karen fat and ugly, Geoff all wrong? In your opinion, did Arran deserve to be an outcast? Did you agree that Kate was unlovable, Sarah unimportant and inferior, Chris stupid, and Jim inadequate and weak?

As an outsider, you could no doubt see that Briony was not responsible for what was done to her, that Jesse’s father’s own needs were clouding his judgment, that Karen’s only shortcoming was not meeting a false ideal, that Geoff’s parents changed towards him because their difficult circumstances made them lose sight of his lovable qualities and made his strengths into sources of stress. It was probably clear to you that the disapproval Arran attracted was no fault of his own, that the limitations of Kate’s parents restricted how loving they could be with her, that Sarah’s parents’ narrow standards prevented them from enjoying her gifts, that Chris’s slowness to learn was nothing to do with stupidity, and that Jim’s distress was a normal and understandable reaction to a horrific event, and not a sign of weakness or inadequacy.

Now think about your own view of yourself and the experiences that have fed into it, while you were growing up and perhaps also later in your life. What do you think your Bottom Line is? What do you say about yourself when you are being self-critical? What names do you call yourself when you are angry and frustrated? What were the words people in your life used to describe you when they were angry, or disappointed in you? What messages about yourself did you pick up from your parents, other members of your family or your peers? If you could capture the essence of your doubts about yourself in a single sentence (‘I am __________’), what would it be?

Remember, your Bottom Line will not have come from nowhere. You were not born thinking badly of yourself. This opinion is based on experience. What experiences exactly? What comes to mind when you ask yourself when you first felt as you now do about yourself? Was there a single event which crystallized your ideas for you? Do you have any specific memories? Or was there a sequence of events over time? Or perhaps a general climate, for example of coldness or disapproval? Make a note of your ideas. You will be able to use this information later on as a basis for changing your perspective on yourself.

Understanding the origins of low self-esteem is the first step towards change. You can probably see that the conclusions Briony and the others reached about themselves were based on misunderstandings about the meanings of their experiences – misunderstandings that make perfect sense, given that at the time they reached the conclusions they had no adult knowledge on which to base a broader, more realistic view or were too distressed to think straight.

This is the key thing about the Bottom Line at the heart of low self-esteem. However powerful and convincing it may seem, however well rooted in experience, it is usually biased and inaccurate, because it is based on a child’s eye view. If your confidence in yourself has always been low, it is likely that when your Bottom Line was formed, you were too young to say ‘hang on a minute’, stand back, take a good look at it, and question its validity; in short, to realize that it is an opinion, not a fact.

Think about your own Bottom Line. Is it possible that you have reached conclusions about yourself on the basis of similar misunderstandings? Blamed yourself for something that was not your fault? Taken responsibility for another person’s behavior? Seen specific problems as a sign that your worth as a person is low? Absorbed others’ standards before you were experienced enough to know their limitations? In particular, if you imagine another person who had had your experiences, would you judge them as negatively as you do yourself, or would you come to different conclusions? How would you understand and explain what has happened to you, if it had happened to someone you respected and cared about?

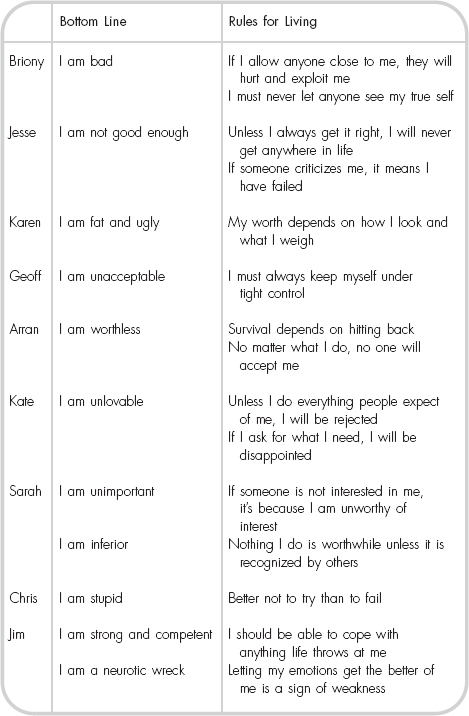

You may find it hard at this stage to approach any sort of different view. Once the Bottom Line is in place, it becomes increasingly difficult to detach oneself from it and question it. This is because it is maintained and, indeed, strengthened by systematic biases in thinking, which make it easy for you to notice and give weight to anything that is consistent with it, while encouraging you to screen out and discount anything that is not. It also leads to the development of Rules for Living: strategies for managing yourself, other people and the world, based on the assumption that the Bottom Line is true.

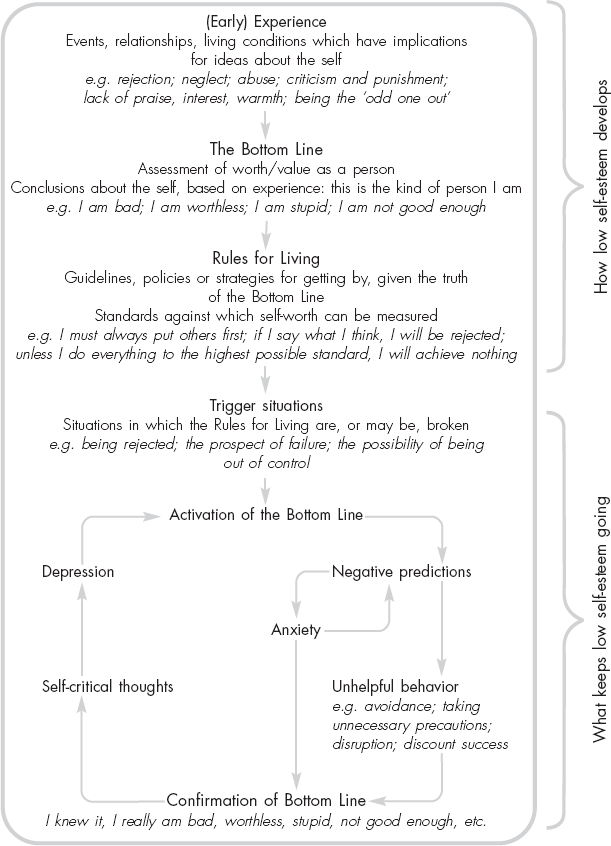

Two biases in thinking contribute to low self-esteem by keeping negative beliefs about the self going. These are: 1) a bias in how you perceive yourself (biased perception); and 2) a bias in what you make of what you see (biased interpretation).

When your self-esteem is low, you are primed to notice anything that is consistent with the negative ideas you have about yourself. You are swift to spot anything about yourself that you are unhappy about, or do not like. This may mean aspects of your physical appearance (e.g. your eyes are too small), your character (e.g. you are not outgoing enough) or simply mistakes that you make (‘Not again. How could I be so stupid?’) or ways in which you fall short of some standard or ideal (e.g. not performing 110 per cent on an assignment). All your shortcomings, flaws and weaknesses jump out and hit you in the face.

Conversely, you are primed to screen out anything that is not consistent with your prevailing view of yourself. It is difficult for you to get a clear view of your strengths, qualities, assets and skills. The end result is that your general focus as you go through your life is on what you do wrong, not on what you do right.

Low self-esteem not only skews your perception of yourself, but also distorts the meanings you attach to what you see. If something does not go well, you are likely to use this as the basis for a global, overgeneralized judgment of yourself – typical, you always get it wrong, etc. So even quite trivial mistakes and failings may seem to you to reflect your worth as a person, and so have (in your eyes) major implications for the future. Neutral and even positive experiences may be distorted to fit the prevailing view of yourself. If, for example, someone compliments you on looking well, you may privately conclude that you must have been looking pretty bad up till now, or discount the compliment altogether (the exception proves the rule, they were only being kind, etc.). Your thinking is consistently biased in favour of self-criticism, rather than encouragement, appreciation, acceptance or praise.

These biases operate together to keep the system in place. Because your basic beliefs about yourself are negative, you anticipate that events will turn out in a negative way (as we shall explore in further detail in Chapter 4). The anticipation makes you sensitive to any sign that things are indeed turning out as you predicted. In addition, no matter how things turn out, you are likely to put a negative spin on events. Consequently, your stored memories of what happened will also be biased in a negative direction. This will both strengthen the negative beliefs about yourself, and make you more likely to predict the worst in future.

Figure 4 Low self-esteem: Biases in thinking

Consistent biases in thinking prevent you from realizing that your beliefs about yourself are simply opinions – based on experience, true enough, and perhaps powerfully convincing – but opinions nonetheless. And opinions increasingly based on a biased perspective, and so further and further adrift from the real you. Christine Padesky, a cognitive therapist, has suggested that it can be illuminating to consider negative beliefs about the self as akin to prejudices. ‘Prejudice’ refers to a belief which does not take account of all the facts, but rather relies on a biased sample of evidence for its support and may be powerful out of all proportion to its real truth value. It is easy to see examples of such powerful beliefs all around us – prejudices against people of certain racial or cultural or religious groups, people of particular age groups, gender or sexual orientations. Such strong opinions, with no real evidential basis, can even drive people to war.

So it is with low self-esteem. Biases in your thinking about yourself (prejudices against yourself) keep your negative views in place, make you anxious and unhappy, restrict your life and prevent you from searching out a broader, more balanced and accurate view of the kind of person you really are.

Even if you believe yourself to be in some way incompetent or inadequate, unattractive or unlovable, or simply not good enough, you still have to function in the world. Rules for Living help you to do this. They allow you to feel reasonably comfortable with yourself, so long as you obey their terms. That is, they make it possible for people to operate more or less effectively in life, despite their belief in the Bottom Line.

Paradoxically, however, they also in fact help to keep the Bottom Line in place and so maintain low self-esteem. A look at the Rules for Living of the people described above may give you a sense of how they make sense in the context of the Bottom Line, and how they work in practice to protect self-esteem.

The Rules for Living each of these people developed can be understood as an attempt to get by, an escape clause, assuming the Bottom Line to be true. On a day-to-day basis, they are expressed through specific policies or strategies. For example, Briony’s rules about the dangers of exploitation and about hiding her true self led her to adopt the strategy of avoiding close relationships. She kept social contact to a minimum and, if forced to spend time with people, kept the conversation light and avoided questions about herself. She was always sharply vigilant for any signs that people might push her into doing things she did not wish to do, and fiercely protective of her personal space.

And, to some degree, such strategies work. For example, Jesse’s high standards and fear of failure and criticism motivated him to perform to a consistently high level, and allowed him to make a resounding success of his working life. But he paid a price for this. His Rules for Living created an increasing sense of strain, and made it impossible for him to relax and enjoy his achievements. In addition, his need to perform meant that work dominated his life, at the expense of personal relationships and leisure time.

In Chapter 7, you will find more detail about Rules for Living, their impact on your thoughts and feelings and how you manage your life, and how to change them and liberate yourself from the demands they place upon you.