In a manner of speaking, people are like scientists. We make predictions (e.g. ‘If I press this switch, the light will come on’, ‘If I stand in the rain, I will get wet’, ‘If I have too much to drink, I will have a hangover’) and we act on them. We use information from what happens to us, and from what we do, to confirm our predictions or to change them. This system of acting on predictions (many of which may be so much a part of how we operate that we do not even put them into words) is generally a useful one, provided that we keep an open mind, are receptive to new information and remain willing to change our predictions in the light of experience and in response to variations in circumstances (e.g., sticking with the light-switch prediction could cause some frustration, in the event of a power cut).

Low self-esteem makes it hard to make realistic predictions, or to act on them with an open mind. When people with low self-esteem make predictions about themselves (e.g. ‘I won’t be able to cope’, ‘Everyone will think I’m an idiot’, ‘If I show my feelings, they will reject me’), they tend to treat them as facts, rather than as hunches which may or may not be correct. So it is difficult to stand back and look at the evidence objectively, or to remain open to experiences which suggest the predictions do not fit the facts. What’s the point? The result is a foregone conclusion.

In low self-esteem, anxious predictions arise in situations where the Bottom Line has been activated because there is a chance that personal Rules for Living might be broken. (If you are absolutely 100 per cent sure that your rule has been broken, then you will miss anxiety and head straight for the sense that your Bottom Line has been confirmed, self-criticism and depression.) If it is not clear whether a rule will actually be broken or not and there is an element of uncertainty or doubt, the consequence will usually be anxiety.

Doubt and uncertainty lead a person to wonder what is going to happen next. Will I be able to cope? Will people like me? Will I make a hash of this? The answers to these questions – predictions about what is about to go wrong – spark anxiety, and lead to a whole range of strategies designed to prevent the worst from happening. Unfortunately, in the long run, these strategies rarely work. The end result, however the doubt is resolved in reality, is a sense that the Bottom Line has been confirmed or, at best, that confirmation has been narrowly escaped.

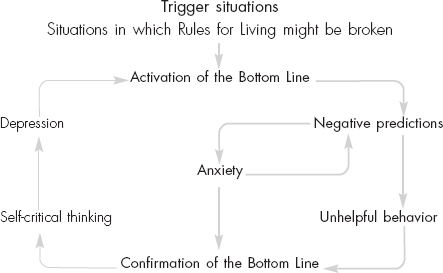

In this chapter, you will learn how to break the vicious circle that keeps low self-esteem going by identifying your own anxious predictions, questioning their validity and checking them out for yourself by approaching situations you might normally avoid and dropping unnecessary precautions. This is the part of the vicious circle that we shall be addressing:

Figure 8 The vicious circle: The role of anxious predictions in keeping low self-esteem going

Think back to the people you met in Chapters 2 and 3. On page 63 was a list of the kind of situations which activated their Bottom Lines. You will see from these examples that, in each case, these are situations where self-protective rules might be broken. And, in each case, there is an element of uncertainty or doubt. Briony’s true (bad) self might be exposed – but she is not sure. Jesse might not be able to meet his high standards – but he is not certain. Karen suspects before she goes shopping that her body shape will not be as it should, for her to feel good about herself – but, as yet, she has no concrete evidence.

This element of doubt is central to the experience of anxiety. It creates a vacuum, which we fill with dreadful imaginings – predictions about what we most fear might happen. We may be aware with a part of our minds that the worst is very unlikely, or even that we would be able to deal with it, should it occur – but we are not convinced and, the more anxious we feel, the less convinced we are.

Anxious predictions result from the sense that we are about to break rules which are important to our sense of self-esteem. Chapter 7 focuses on ways of changing and adapting Rules for Living in their own right. But first, you will learn how to break the vicious circle that keeps low self-esteem going by identifying and changing the predictions that make you anxious in everyday situations.

Anxious predictions usually contain biases which feed into the sense of uncertainty and dread. These are:

When we find ourselves in situations where adherence to our particular rules is under threat, the likelihood that something will go wrong is much inflated in our minds. Let us take Kate as an example. You may remember that Kate’s parents had difficulty in expressing their affection for her. Her Bottom Line was that she was unlovable, and her Rules for Living were that if she failed to meet others’ expectations she would be rejected, and that if she ever asked for her needs to be met she would be disappointed. Kate worked in a hairdresser’s. She and her colleagues took it in turns to go out and buy the lunchtime sandwiches. One day, when it was her turn, her boss forgot to pay her back for his sandwich. Kate felt completely unable to ask for what she was owed. She was convinced that, if she did so, her boss would despise her and think she was mean. This was despite the fact that she knew from months of working for him that he was a kind, thoughtful man who was careful of his employees’ welfare. She took no account of the evidence, which suggested that in fact he was likely to be embarrassed, apologize and immediately give her what she was entitled to.

Not only is it likely that bad things will happen, but when they do, they will be very bad. Anxious predictions rarely assume that, if something bad does happen, it will be a momentary inconvenience, quickly over, after which life will go on. At the heart of anxious predictions is the notion that the worst possible thing will happen and that, when it does, it will be on the scale of a personal disaster.

So Kate, for example, when she looked ahead, could not see her boss being mildly inconvenienced by having to pay her back, and then quickly forgetting all about it. She assumed that asking for what was owed her would permanently change their relationship. He would never look at her in the same way again, and she would probably need to find another job – which would be difficult, because he would not want to give her a reference, and she might get a reputation as someone with a tendency to cause personality clashes and find it difficult to get another job of any sort. Then she would not be able to live independently, but would have to go back to her parents and live on state benefit and would be completely stuck. Kate could clearly see all this happening, in her mind’s eye.

You can see here how what, to an outside observer, might seem a trivial event (asking for money for a single sandwich), for Kate leads into a whole saga unfolding, each step worse than the last. This kind of sequence is typical of anxious thinking.

When people are anxious they are apt to think that, if the worst should happen, there will be nothing they can do to prevent it or make it manageable. Kate assumed that, no matter what she did, her boss’s reaction would be completely rejecting. It did not occur to her that she could stand up to her boss, if he did indeed respond as she predicted, by reminding him assertively that she was entitled to get her money back. Nor did she take account of her professional skill and experience, which in fact made it very likely that she would find other employment quite easily.

In addition to underestimating their own personal resources, people making anxious predictions tend to underestimate things outside themselves that might improve the situation or even defuse it entirely. Kate, for example, forgot the support she would get from her colleagues, friends and family if her boss reacted so unreasonably.

Put together, these biases in thinking constitute a perfect recipe for fear. They give you a strong sense that you are at risk – of failure, of rejection, of losing control, of making a fool of yourself. In short, of breaking the rules. So, like any sensible person facing a threat, you take precautions to protect yourself, to stop the worst from happening. Unfortunately, the precautions you take, far from improving things, actually prevent you from discovering for real whether your anxious predictions have any true foundation and so keep low self-esteem going.

It will not be possible for you to discover whether or not your anxious predictions have any basis in reality, unless you drop the precautions you have been taking to ensure that they do not come true. That is the only way to discover if your ideas are correct – if the precautions are not dropped, you will always have a sneaking feeling that you had a narrow escape, and will never really be certain whether your thinking was biased or not.

An example may help to make this point. Imagine you go for a meal at the house of Vladimir, an old friend. As soon as you come in, you notice a powerful smell. Could it be something to do with the cooking? With your pre-dinner drinks, you have garlic croutons and a garlic dip. The first course is garlic soup, with garlic bread. This is followed by roast lamb with whole garlic cloves, and salad with a garlic dressing. For dessert, garlic ice cream (surprisingly interesting) and, to conclude, a creamy French cheese with herbs and – you’ve guessed it – garlic. As the evening progresses, you become gradually aware that the room is hung with wreaths and garlands of garlic. Finally, curiosity wins out over politeness.

‘What’s with all this garlic?’ you ask.

‘Ah!’, replies Vladimir. ‘I was hoping you wouldn’t notice.

I didn’t want you worrying.’

‘Worrying?’

‘Well, yes. It’s the vampires, you see. I didn’t want you

worrying about the vampires.’

‘The vampires?’

‘Yes. I think we’ve got enough garlic to keep them away,

though,’ says Vladimir reassuringly.

‘But there aren’t any vampires,’ you protest.

‘Exactly!’ says Vladimir smugly.

The strategies people employ to prevent their worst fears from coming true are like Vladimir’s garlic. It seems to him that the only reason the house is not overrun with vampires is that it is full of garlic. He could, of course, be right: though a review of available evidence might suggest that his fears are exaggerated. In order to discover that the danger is more apparent than real, he would have to abandon this self-protective strategy and get rid of all the garlic. Given the strength of his belief in vampires, this might be quite difficult for him to do. He might need to do it one step (or clove) at a time. Or, if he were able to consider the evidence coolly, he might be prepared to go the whole hog and rid the house of garlic entirely. Only then could he discover that his fears are unfounded – he is actually quite safe.

The first steps towards achieving a more balanced view of what is really likely to happen in situations you fear are: first, to become aware of what you are predicting when you become anxious; and, second, to notice the precautions you take to stop your predictions coming true. This means learning how to tune into anxiety or apprehension as soon as it happens, noticing what is running through your mind when the feeling starts, and spotting what you do to protect yourself. This information will provide you with a basis for change – rethinking your predictions and checking out their validity by doing the things you are afraid of without taking unnecessary precautions.

On page 92, you will find a blank record sheet which you can use to make your own record of anxious predictions and the steps you take to avert disaster (the ‘Predictions and Precautions Record Sheet’; there are further blank copies provided in the Appendix). Kate’s dilemma is illustrated as an example on page 93, to give you a sense of what you are aiming at.

The main benefit of using a structured record sheet like this, rather than simply keeping a day-to-day diary of things that come up, is that it will encourage you to follow things through in a systematic way. The headings will remind you of what you should be looking out for, and later what steps you need to take to change things for the better. In contrast, simply keeping a narrative diary may result in you getting lost in your fears, especially if your low self-esteem has been in place for some time and anxious predictions have become a habit that is hard to break. If you do prefer to use your own form of diary, then at least structure your investigations by following the headings on the suggested record sheet.

If at all possible, make your record at the time you actually experience the anxiety. This is because it is often difficult to tune into anxious predictions when you are not actually feeling anxious. Even if you can work out what they are, they may seem ridiculous or exaggerated when you are not in the situation, and so it will be difficult to accept how far you believed them and how anxious you felt at the time. The steps involved are these:

Make a note of when you experienced anxiety. This information may help you to spot patterns from day to day. If, for example, your rules relate to competence and achievement, then you may notice peaks in anxiety as you arrive at work. If, on the other hand, your doubts relate to how acceptable you are to others, then you may find your worst time is weekends, when you are expected to socialize.

What was going on when you started to feel anxious? What were you doing? Who were you with? What was happening?

It could be that the situation that activated your Bottom Line was an outside event (for example, having to answer a difficult question in front of colleagues, or receiving a bill through the post). Or it could be something inside yourself (for example, remembering a time in the past when you felt embarrassed and humiliated, thinking about a task that you have been putting off, or noticing that your palms are sweating when you are about to shake hands).

Changes in your anxiety level are a signal telling you that you are making anxious predictions. Make a note of the emotion you experienced. Was it apprehension? Fear? Anxiety? Panic? Look out for other emotions, too – for example, feeling pressurized, worried, frustrated, irritable or impatient. Rate each emotion between 0 and 100, according to how strong it is. One hundred would mean it was as strong as it could possibly be, 50 would mean it was moderately strong, 5 would mean there was just a hint of emotion, and so on. You could be anywhere between 0 and 100. The idea of rating the intensity of your emotions, rather than just noting that they were present, is that when you come to work on changing your anxious predictions, you will be able to pick up small changes in your emotional state which you might otherwise miss.

Anxiety normally goes along with a whole range of body sensations. These vary to some extent from person to person. They are reflected in the sayings we commonly use to describe anxiety – ‘uptight’, ‘shaking like a leaf’, ‘on edge’, ‘white as a sheet’, ‘sick with fear’, and so on. They include:

All of these are in fact part of the body’s normal built-in response to threat. To some extent, they are actually helpful – for performers such as musicians or athletes, for example, being keyed up gives an edge to their performance. The physical symptoms of anxiety are signs that glands near the kidneys are releasing adrenalin, a hormone that prepares the body for ‘fight or flight’ – that is, to confront and tackle the danger that threatens, or to run away from it. Your anxious predictions are telling your body that it needs to go on red alert. Once you become skilled at defusing the predictions, your body will stop responding in this way. In the meantime, it will be helpful to notice your own particular bodily reactions to anxiety, not least because (as we said in Chapter 3) these reactions can in themselves give rise to further anxious predictions – for example, ‘Everyone will notice how nervous I am and think I’m weird’, ‘If this goes on, I’m going to crack up’, or ‘I can’t possibly cope with this situation, feeling as I do’. Naturally enough, these extra predictions are likely to intensify the anxiety, forming a mini-vicious circle that contributes to keeping the problem going.

So make a note of your body sensations, and rate them between 0 and 100, according to how strong they are, just as you rated the intensity of your emotions. And watch out for any extra predictions you make, based on how you are feeling. You can record them in the next column.

What was going through your mind just before you began to feel anxious? And as your anxiety built up? The thoughts you are looking for will be concerned with the future – with what is about to happen. They will, in effect, be your predictions about what is going to go wrong, or is already going wrong. Write them down, word for word, just as they occur to you. Then rate each one between 0 and 100 per cent, according to how strongly you believe it. One hundred per cent means you are fully convinced, with no shadow of doubt; 50 means you are in two minds; 5 means you think there is a remote possibility; and so on. Again, you could be anywhere between 0 and 100 per cent. Generally speaking, you are likely to find that the more strongly you believe your predictions, the more anxious you feel. And, of course, the reverse is also true – the more anxious you feel, the more likely you are to be convinced by your predictions and to behave accordingly, taking steps to protect yourself that are in fact unnecessary and unhelpful.

You may find that your thoughts do not take the form of identifiable predictions, You may experience images in your mind’s eye instead. These may be snapshots or freeze frames, or they may take the form of movies – a stream of events following on from one another – like Kate’s fears about her boss’s reaction and what would follow from that. These images and sequences may be very vivid and therefore highly convincing. They usually illustrate what a person fears may happen. That is, they are like a visual version of your worst fears – your anxious predictions. Describe them as clearly as you can, identify the predictions they contain, and rate how far you believe each one (0–100 per cent).

Alternatively, you may find that your thoughts do not take the form of explicit predictions, but rather of short exclamations like ‘Oh my god!’, or ‘Here I go again!’. If this is the case, write the exclamation down, and then spend some time considering what it may mean. What is the prediction concealed in the exclamation? If you unpack the meaning behind the explanation, the level of anxiety you are experiencing will make sense. Ask yourself: what might be about to happen? What is the worst that could happen? And then what? And then what? ‘Here I go again’ – well, where? Again, write the hidden predictions down, and rate how far you believe each one (0–100 per cent).

Finally, your prediction may be concealed in a question, such as, ‘Will they like me?’ or ‘Supposing I can’t cope?’ or ‘What if everything that goes wrong?’ Many anxious thoughts take the form of questions, which makes sense when we consider that they are a response to uncertainty or doubt. To find the hidden prediction, ask yourself: what is the answer to this question which would account for the anxiety I am experiencing? For example, if your question is ‘Will they like me?’, the hidden negative prediction is likely to be ‘They won’t like me’. You could believe this fairly strongly, or hardly at all, or somewhere in the middle.

When one is faced with a genuine threat, it makes perfect sense to take steps to prevent it from causing harm. The threat you are facing may be more apparent than real, once you come to stand back and take a good look at it, but for the moment it seems real enough. So what do you do to protect yourself from it? What steps do you take to ensure that it does not come to pass? Complete your record by writing down the precautions you take, in as much detail as you can.

In particular, look out for:

Technically, such precautions are called safety-seeking behaviors, precisely because they are things we do to keep ourselves safe and protect ourselves from breaking our rules. Complete avoidance is usually relatively easy to spot. Safety-seeking behaviors may be less obvious. Sometimes they are quite subtle – you may not be fully aware of them at all. This calls for careful observation of yourself, which you can do best if you experiment with entering situations you fear and watching out for how you keep yourself safe in those situations. You can do this in your imagination, too. Kate, for example, did not at first feel ready to approach her boss at all. But she could imagine how she would operate if she was able to screw up her courage to the point of asking for her money back. She saw herself avoiding eye contact, apologizing profusely, telling him it didn’t really matter, speaking quietly and hesitantly, and rushing to get the encounter over as quickly as possible. Before speaking at all, she would rehearse numerous times exactly what to say, trying to make sure that she made her request in the most inoffensive way.

Keep your record for a few days or a week, making a note of as many examples as you can. By the end of that time, you should have a pretty good idea of the situations in which you feel anxious, the predictions that spark off your anxiety, and the precautions you take to prevent the worst from happening. This is your basis for beginning to question your anxious predictions, and to check them out by dropping unnecessary precautions and finding out for yourself whether what you fear is really likely to happen.

Anxious predictions are unhelpful. Far from preparing you to deal effectively with daily life, they make you feel bad and lead you to waste energy on taking precautions that only serve to keep the vicious circle of low self-esteem going. So changing them has a number of benefits: it makes you feel better, gives you an improved chance of approaching life with confidence and enjoying your experiences, and encourages you to experiment with being your true self.

Two main steps are involved in checking out anxious predictions:

1 questioning them so as to arrive at more realistic and helpful alternatives, and

2 testing new perspectives out in practice by approaching (instead of avoiding) the situations you fear, and dropping your safety-seeking behaviors.

This may seem like rather a daunting prospect. However, you will find that discovering alternatives to your predictions will help you to feel less fearful about going into what now seem like risky situations and to drop self-protective strategies. This is important: if you do not change how you operate when you feel yourself to be under threat, you will never feel fully confident that the new perspectives you discover are genuinely reality-based, rather than rationalizations with no real truth.

The best way to construct a more helpful and realistic perspective on situations that make you anxious is to learn to stand back and question your predictions, rather than accepting them as fact. You can use the questions summarized in the table on page 105, to help you to discover more helpful and realistic perspectives and tackle the biases in thinking that contribute to anxiety. Each time you find an answer or alternative to your anxious predictions, write it down and rate how far you believe it (0–100 per cent). You may well not believe your alternatives fully at the moment, but you should at least be prepared to accept that they might theoretically be true. Once you have a chance to test them out in practice, you will find your degree of belief will increase.

You may find it helpful to write down your alternatives on copies of the record sheet you will find on page 102 (‘Checking Out Anxious Predictions Record Sheet’; additional blank copies are provided in the Appendix). A completed sheet, using Kate as an example, is on page 103. Again, a structured record sheet may be more helpful than a narrative diary because it will help you to follow things through in a systematic way rather than getting stuck in your fears.

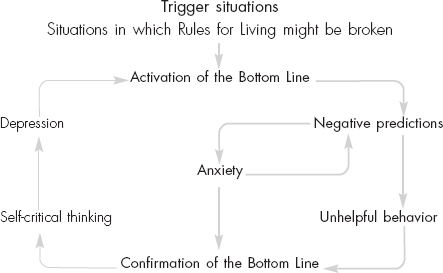

Figure 13 Key questions to help you find alternatives to anxious predictions

• What is the evidence to support what I am predicting?

• What is the evidence against what I am predicting?

• What alternative views are there? What evidence is there to support them?

• What is the worst that can happen?

• What is the best that can happen?

• Realistically, what is most likely to happen?

• If the worst happens, what could be done about it?

What makes you think what you do? What are you going on when you anticipate the worst? Are there experiences in the past (maybe even very early in your life) that have led you to expect disaster in the present day? Or is your main evidence simply your own feelings? Or the fact that in this sort of situation, you always expect things to go wrong – it’s a habit?

Stand back and take a broader view. What are the actual facts of the current situation? Do they support what you think, or do they contradict it? In particular, can you find any evidence which does not fit your predictions? Is there anything you have not been attending to which would suggest that your fears may be exaggerated? Are there any rescue factors you have been ignoring? Any resources in yourself that you have been putting to one side? Any indications from past or current experience that would suggest things may not go as badly as you fear?

The temptation with anxious predictions is to assume the worst – to jump to conclusions. Instead, stick to the facts.

Are you falling into the trap of assuming that your view of things is the only one possible? There are always many ways of thinking about an experience. A mistake, for example, may seem to a person with low self-esteem to be a disaster or a sign of failure. But to another person, it might seem like a minor inconvenience, or an understandable result of normal human imperfection, or a product of tiredness or of a moment’s inattention which simply needs correction, or even a valuable opportunity to learn and to extend one’s knowledge and skill.

Consider the situation you are facing at the moment. What would your view of it be, for example, if you were feeling less anxious and more confident? What might another person make of it? What would you say to a friend of yours who came to you with the same concern – would your predictions be different? Are you exaggerating the importance of the event? Assuming it will have lasting repercussions if things do not work out as you wish they would? What will your perspective be on this event after a week? A month? A year? Ten years? Will anyone even remember what happened? Will you? If so, will you still feel the same about it? Probably not.

Write down the alternative perspectives you have found, and then make sure you review the evidence for and against them, just as you reviewed the evidence for and against your original predictions. An alternative which does not fit the facts will not be helpful to you, so make sure your alternatives have at least some basis in reality.

This question is particularly useful in dealing with anxious predictions. Making your predicted ‘worst’ explicit allows you to get a clear take on it, and can be helpful in a number of ways. Once you have put the worst down in black and white, you may immediately see that what you fear is so exaggerated as to be impossible. Kate, for example, had a flash in her mind’s eye of her boss having a major tantrum in the middle of the salon and throwing her out. In reality, there was no way that he would behave so unprofessionally in front of all his clients and staff, however he felt about her request.

Look for whatever information you need to obtain a more realistic estimate of the true likelihood of what you fear occurring. Even if it is not impossible, it may be much less likely to happen than you predict. Additionally, there may be things you can do to reduce the likelihood of the worst happening, in just the same way that you might have the wiring checked and buy smoke alarms and a fire extinguisher when you move into a new house.

This is a counterbalance to the previous question. Try to think of an answer which is just as positive as your worst is negative. You may notice, incidentally, that you are less inclined to believe in the best than you were to believe in the worst. Why? Could it be that your thinking is biased in some way?

Kate called up an image of her boss congratulating her in front of everyone for standing up for herself, rushing out to buy her flowers and chocolates, and insisting on giving her an immediate pay rise and a promotion. Creating this unlikely vision helped her to see how exaggerated her fears were, too.

Look at the best and worst you have identified. Realistically, what is most likely to happen is probably somewhere in between. See if you can work out what it might be.

Once you have worked out what the worst is, you can plan how best to deal with it. And once you have worked out how to deal with the worst, anything else is a piece of cake. Remember, anxious predictions underestimate the resources likely to be available to you in difficult situations. Even if what you fear is quite likely, it is possible that you would in fact be better able to cope with it than you have automatically assumed, and that there would be resources available (including the goodwill and assets of other people) to help you to do so. Consider:

Discovering alternatives to anxious predictions is often helpful in itself. You may well find that, as your focus clears, you begin to feel less fearful of the catastrophic consequences of breaking your rules. However, questioning your thoughts may not be enough in itself to convince you that things are not as bad as they seem. You need to act differently, too, to learn how things really are through direct experience. Experimenting with new ways of doing things (for example, being more outgoing and assertive, taking the risk of being yourself with other people or accepting challenges and opportunities you would previously have avoided) allows you to build up a body of experience that contradicts your original predictions and supports new perspectives.

Experiments provide a direct test of what you think, a chance to fine-tune your answers in the real world, to break old habits of thinking and strengthen new ones. They give you an opportunity to find out for yourself whether the alternatives you have thought up are in line with the facts, and therefore helpful to you, or whether you need to think again. But this will only happen if you take the risk of entering situations you have been avoiding, and drop the precautions you have been taking to keep yourself safe. Experiments will help you to weed out alternative ways of thinking that do not work for you, and to strengthen and elaborate those that do. Without them, your new ideas are largely theoretical. With them, you will know on a gut level what the reality is. We shall return to the idea of experiments repeatedly throughout this book.

You have learned to identify your anxious predictions, their impact on your feelings and body state, and the precautions you take to ensure that they do not come true. You have moved on to begin to question your predictions, examining the evidence and searching for alternative perspectives that may be more realistic and helpful. You can use these skills as a basis for setting up experiments to check out for yourself whether your predictions are accurate. You can do this quite deliberately (for example, planning and carrying out one experiment every day), and you can also use situations that arise without you planning them (e.g. an unexpected phone call or an invitation) to practise acting differently and observing the outcome, using the final column of the record sheet on page 102.

Make sure that what you fear might happen is very clearly and explicitly stated (you have already learned to tune in to anxious predictions). Experiments are most useful when they are designed to test out specific troublesome predictions. If your predictions are vague, it will be difficult to ascertain whether or not they have come true. So write down exactly what you expect to happen, including, if relevant, how you think you and other people will react, and rate each prediction according to how strongly you believe it (0–100 per cent). For example, if you are predicting that you will feel bad, rate in advance how bad you think you will feel (0–100), and in what way. Many people find that, to their surprise, they do indeed feel anxious (for example), but not as much as they expected, especially once they get over the initial hurdle of entering the feared situation. Your rating will give you a chance to find out if this is true for you.

Again, your prediction may involve others’ reactions. Perhaps you think that if you behave in a given way, people will lose interest in you, or disapprove of you. If so, work out how you would know this was happening. What would they say or do that would be a signal that they were indeed losing interest or disapproving? Include small signs like changes of facial expression, and shifts in direction of gaze. Once you have defined how you would know that what you fear is happening, you will know exactly what to look for when you go into the situation.

Again, you will be aware from your record-keeping what precautions you normally take to keep yourself safe. If you continue to do so, you will not be able to find out if your predictions are true or not. Even if your experiment seems to turn out well, you will be left with the sense that you have had a ‘near miss’. So be as clear as you can here. Think of all the things you might be tempted to do to protect yourself, no matter how small. Work out in advance what you will do instead. For example, if your normal pattern when you talk to someone is to avoid eye contact and say as little as possible about yourself, in case people discover how boring you are, your new pattern might be to look at people (how else, apart from anything, will you have the remotest idea what they think?) and talk as much about yourself as they do about themselves. If your normal pattern at work is to have an answer to every question and never admit to ignorance, in case people think you are not up to the job, you could practise saying ‘I don’t know’ and ‘I have no opinion on that’. If your normal pattern is to hide your feelings, because to show them at all could lead you to lose control, you might experiment with being a little more open with someone you trust, about something that has annoyed or upset you, or with showing affection more overtly than you normally would.

Whatever the nature of your experiment, it will be crucial to observe the consequences of acting differently so that, if your worst fears do turn out to be incorrect, you will be in a position to come up with more accurate predictions in similar situations in the future. To make sure you always make the most of any experiment you carry out, always review your results afterwards. What did you learn? What impact did acting differently have on how you felt? How far was what happened consistent with your original predictions, and with the alternatives you found? What implications does what actually happened have for your negative view of yourself? Does it fit? Or does it suggest that you could afford to think more positively of yourself?

In terms of outcome, there are two broad possibilities. Both are useful to you as sources of information about what is keeping your low self-esteem going. On the one hand, experience may show that your anxious predictions were not correct, and that the alternatives you found were indeed more realistic and helpful: so much the better. On the other hand, sometimes experience shows anxious predictions to be absolutely spot on. If so, do not despair. This is valuable information. How did this come about? Was it in fact anything to do with you, or some other element of the situation? What other explanations might there be for what went wrong, besides you? If you did contribute in some way to what happened, is there any way you could handle the situation differently in future, so as to bring about a different result? For example, are you sure you dropped all your safety-seeking behaviors?

Be honest! Look back over what happened and scrutinize yourself carefully. If some precautions were still in place, what do you think might have happened if you had dropped them (anxious predictions)? How could you check this out? Exactly what changes do you still need to make to your behavior? How will you ensure that you drop your safety-seeking behaviors completely, next time?

When you have carefully thought through what happened, work out what experiments you need to carry out next, using the same steps described above. How could you apply what you have learned in other situations? What further action do you need to take? Should you repeat the same experiment to build your confidence in the results? Or should you move on to try similar changes in a new and perhaps more challenging situation? What’s the next step?

Whatever the outcome of your experiment, congratulate yourself for what you did. Giving yourself credit for facing challenges and things that involve an effort is part of learning to accept and value yourself – part of enhancing self-esteem. What does what happened tell you about yourself, other people and how the world works? Given what has hap-pened, what predictions would make better sense next time you tackle this type of situation? What general strategies could you adopt, based on what happened here, that will help you to deal even more effectively with similar situations in future?

Kate needed to buy a new washing machine. She had successfully experimented with asking her boss for the money he owed her, and discovered that her predictions were not accurate. However, she was still doubtful about her ability to ask effectively for what she needed. She predicted that if she took the time to enquire fully about the options available, and did not immediately understand the technological detail, the shop assistant would be impatient and would not respect her. She would know this because the assistant would use a snappy tone of voice, would leave her for another customer, and would make faces at other assistants. Her usual self-protective strategy in this kind of situation was to pretend to understand, only look at one or two models, and be effusively apologetic about taking the assistant’s time.

She decided instead to ask as many questions as she needed in order to be clear about what her options were, to look at models right across the price range, and to be pleasant and friendly but not apologetic at all. After rethinking the prediction in advance, she came to the conclusion that although the reaction she feared might happen, it was unlikely, and might say more about the assistant than about her. This gave her the courage to have a go.

To her dismay, in the first shop she tried, the assistant behaved almost exactly as she had predicted. He was dismissive, kept turning to talk to other people, and did not seem to care whether she bought a machine or not. Fortunately, she had an opportunity that evening to talk over what had happened with a friend. The friend said that she had had much the same experience in the same shop, and recommended trying another with a better record of customer service. This allowed Kate to understand what had happened in a new way, rather than simply assuming that her original predictions must be correct. It restored her morale enough to have another go.

She discovered that it was possible to follow through her new, more assertive strategy without penalty. She asked lots of questions, asked the assistant to repeat himself a number of times, looked at a whole range of models, and in the end did not buy anything. The assistant treated her with courtesy, invited her to telephone if she had any further queries, and gave her his card. Further experiments on the same lines in other shops confirmed this new experience. Kate’s conclusion was: ‘I am entitled to take as long as I want to make a decision to spend my money. Asking questions and showing ignorance is OK – how else am I to find out what I need to know? If people are rude, that’s their problem – it doesn’t say anything about me.’