Negative beliefs about yourself may have roots in the past, but their impact continues into the present day. Otherwise, you would not be reading this book! This chapter will help you to understand how everyday patterns of thinking and behavior keep low self-esteem going and prevent you from relaxing into your experiences and valuing and appreciating yourself.

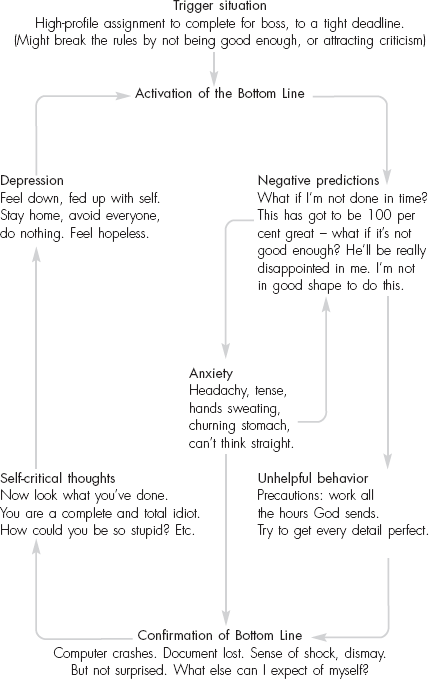

We shall be looking at the vicious circle that is triggered when you find yourself in a situation in which you might break your rules for living and so activate your Bottom Line. The circle is shown in the bottom half of the flowchart on page 33, and is described in detail below. This chapter will outline how it works in practice, showing how anxious predictions and self-critical thinking affect how you feel and act in your daily life. The idea is that you should apply these ideas to yourself and explore how they fit your own thoughts, feelings and behavior. So, while you read the chapter, keep asking yourself: how does this fit? What are the situations that trigger anxious predictions in me? How do my predictions affect my emotions and my body state? What do I do (or not do) to stop them from coming true? What does confirmation of my beliefs about myself feel like for me? How do I know it is happening? What is the nature of my self-critical thoughts? What effect do they have on my feelings, on what I do – most particularly on my beliefs about myself?

You may find it helpful to keep pen and paper beside you, and draw up your own vicious circle as you go through the chapter. Use the ideas described here as an opportunity to reflect on yourself and deepen your understanding of how low self-esteem influences you on a day-to-day basis.

In the last chapter, we introduced the idea that the Rules for Living that you have devised, and the day-to-day strategies through which they express themselves, can, in the short term, help to keep low self-esteem at bay. However, at the end of the day, they actually keep it going because they make demands which are impossible to meet – for example, perfection, universal love and approval, complete self-control or control over your world. This means that well-being is inevitably fragile. If you find yourself in a situation where you are in danger of breaking the rules (e.g. operating below 100 per cent, being disliked or disapproved of, losing control of yourself or your world), the Bottom Line which your rules have protected you against rears its ugly head. Self-doubt emerges from the shadows and begins to dominate the picture. You experience a sense of uncertainty – suddenly you feel insecure.

Figure 6 Situations triggering the Bottom Line

The exact nature of the situations that activate your Bottom Line will depend on the nature of the Bottom Line itself, and on the rules you have adopted to cope with it. So, for example, if your Bottom Line concerns your acceptability to other people, and your rules are designed to ensure that acceptability, then the situations which are likely to be problematic for you are those where you fear your acceptability might be compromised. If, on the other hand, your Bottom Line concerns achievement, success or competence, and your rules focus on high standards and are designed to ensure that you always achieve these, then the situations in which you will feel threatened are those in which you might fall below what you expect of yourself. And so on.

Think back to the people you met in the last chapter. For each of them, the situations that triggered the Bottom Line were a direct reflection of the nature of their beliefs about themselves, and of their Rules for Living:

Thus the situations that activate the Bottom Line and bring it into play are those in which the rules might be broken (or have been broken), situations which raise doubts about yourself and have direct implications for how you perceive yourself and for the value you place on yourself as a person. These may be quite major events, e.g. a broken relationship, a job lost, a serious illness or a child leaving home. However, many of the situations which rouse self-doubt and uncertainty on a day-to-day basis are on a much smaller scale. Many are small ups and downs of a kind you may not even be fully aware of, or may brush aside with ‘Don’t be silly’, or ‘Come on, pull yourself together’.

If you want fully to understand what keeps your poor opinion of yourself going, tuning into these small events is a crucial step. In the chapters to come, you will learn how to become more sensitive to the changes in mood that tell you that your Bottom Line is activated, and how to observe the thoughts, feelings and behavior that follow from activation. For now, just reflect for a moment. Think over the last week. Were there any moments when you felt anxious or ill at ease, uncomfortable with yourself, or doubtful about your ability to handle what was going on? Were there any times when you suspected that you were not coming over as you might wish to do, felt a bit useless, or attracted worrying reactions from other people? Did you at any point feel that things were getting on top of you, or as if you were not operating at the level you expect of yourself?

Make a note of those situations. Do you notice any patterns? If so, what does this tell you about your own personal Rules for Living – what you require of yourself and what you need from other people, in order to feel good about yourself? What rules were you breaking, or in danger of breaking? What kind of ideas about yourself came into your mind in those situations? Were you aware of using any uncomplimentary words to describe yourself? What were they? They may reflect your central negative beliefs about yourself (your Bottom Line).

Once the Bottom Line is activated, the uncertainty inherent in the situation that triggered it gives rise to specific negative predictions (fears about what might happen), whose content depends on the nature of your particular concerns.

To illustrate this, let us take a situation which most people find somewhat intimidating, but which for a person with low self-esteem can be real torture. Suppose you had to stand up and give a talk to a group of people, i.e. speak in front of an audience. Imagine having to do this in any situation with which you are familiar – work, perhaps, or your church, an evening class you have attended, the clinic you take your baby to, or your child’s school assembly. What is your immediate reaction when you contemplate having to stand up and speak in public? What thoughts come to mind? ‘I couldn’t do it’? ‘I’d make a total fool of myself’? ‘No one would want to listen to me’? ‘I’d get so anxious I would have to run out’?

Or do you perhaps have an image in your mind’s eye of what might happen? Yourself red in the face and sweating and everyone staring, for example? Or people gazing out of the window and looking bored and irritated? Or perhaps trying to look kindly on you, but in their heart of hearts thinking what a sad case you are? The thoughts that spring to mind when you contemplate giving a talk in public are likely to be about what you think might happen, and in particular what you envisage might go wrong. That is, they are your own personal view of the future – negative predictions which, as we shall see, have a powerful impact on your feelings and on your behavior.

For a person with low self-esteem confronted with the need to speak in public, what immediately springs to mind will be all the ways in which the presentation could go wrong. He or she will probably assume that the worst will happen, and that there is little or nothing that can be done to prevent it. Just as the situations that activate the Bottom Line vary from person to person, depending on its focus of concern, so the exact nature of the negative predictions will vary from person to person, depending on what is most important to them. When Arran imagined the public speaking scenario, for example, he predicted that people would write him off before he even opened his mouth – no one would accept that someone like him could possibly have anything to say that was worth listening to. Jane’s main concern, in contrast, was that she would fail to meet her audience’s expectations. Sarah’s prediction was simply that people would be bored. Geoff thought he would make a fool of himself by saying something inappropriate. People would consider he was showing off. Jim was concerned that he would be nervous, and that it would show.

You can see here how each person’s predictions stem from the beliefs they have about themselves, and from the rules they have devised to compensate for those beliefs. Once you know their stories, their fears make perfect sense. In Chapter 4, you will be learning how to tune into your own anxious predictions by observing your reactions in situations which make you nervous and observing your thoughts, the words or images which come into your mind when you feel your self-esteem is in danger of being compromised. This is important, because negative predictions, if unchallenged, have a powerful impact on your emotional state and on your behavior, and so contribute to keeping low self-esteem going. Let us consider this by continuing the public speaking example.

Put yourself back into the public speaking scenario. Imagine the worst that could happen. Make your anxious predictions as real as you can. What happens to your emotional state when you do this? What changes do you notice in how you feel?

Predicting that things will go wrong normally leads to anxiety. This may not be quite the word you would use – perhaps you feel apprehensive, nervous, uptight, frightened, panicky or even terrified. You will recognize all these as varieties of fear. Now, notice what happens in your body when you are afraid. What changes do you observe? What happens to your heart rate? Your breathing? The level of tension in your muscles? Which muscles in particular have tightened up? Do you notice any sweating – perhaps on your forehead, or the palms of your hands? Do you feel shaky? What about your digestive system? Do you notice any sensations in your stomach – fluttery feelings, perhaps, or a churning sensation?

All these are physical signs of anxiety, the body’s wired-in response to threat.

To a person with low self-esteem, these normal reactions may seem to have a more sinister meaning. They could become a source of further anxious predictions (this mini-vicious circle is illustrated on the right-hand side of the bottom half of the flow chart on page 33). If your mouth had gone dry, for example, you might fear that you would be unable to speak. If your hands were feeling shaky, you might predict that your nervousness would be obvious to your audience, and that they would think you incompetent or weird. If, when you are anxious, your mind tends to go blank, you may worry that you will appear tongue-tied or incoherent, or as if you don’t know what you are talking about. Such reactions to signs of anxiety naturally tend to intensify it and add to the stress of the situation.

Anxious predictions can affect your behavior in a number of unhelpful ways. To understand how this works, let us go back to the public speaking scenario again.

If you believed your anxious predictions strongly enough, you might simply decide to avoid the situation altogether. You might phone the person who had organized your presentation and tell them you had flu and would not be able to make it. Or you might simply not turn up.

This would mean that you had no opportunity to discover whether or not your anxious predictions were in fact correct. It could be that things would actually have gone much better than you predicted – events are often much less intimidating in reality than they are in anticipation. Avoiding the situation stops you from finding this out for yourself. So avoidance, although it may help you feel better in the short term (what a relief – you got out of it), ultimately contributes to keeping low self-esteem going.

The implication of this, when we come to consider how to change current patterns, is that, in order to develop your confidence in yourself and your self-esteem, you will need to begin approaching situations that you have been avoiding. Otherwise, your life will continue to be restricted by your fears, and you will never gain the information you need to have a realistic, positive perspective on yourself.

Rather then avoiding the situation altogether, you might decide to go and give your talk, but put in place a whole range of precautions designed to ensure that your worst fears do not come true – that you manage to obey your rules and escape from the situation with your self-esteem intact. So, for example, Jane thought she would need to spend a great deal of time considering carefully what people might want to hear and trying to include all the possibilities in her talk. During the talk itself, she would be watching constantly for signs that people were not happy with what she was saying, and would smile a lot at her audience. Jesse, on the other hand, believed that the crucial thing was to appear 100 per cent confident and competent, and thought he would rehearse and rehearse and rehearse what he was going to say in order to get the content and presentation style absolutely right in every detail. He would make sure his talk filled all the time available, so that there would be no time for questions which he might not be able to answer.

What would you do if you had to give a public presentation, in order to ensure that your worst fears were not realized?

The problem with self-protective manoeuvres like these is that, however well things go, you are left with the feeling that you had a ‘near miss’. If you had not taken these precautions, then the worst would have happened. So again, you will not have had the opportunity to find out for yourself whether your fears were actually true or not, to discover that your precautions were excessive and even unnecessary. You will be left with the sense that your success (and so your feeling of self-worth) was entirely due to the precautions you took. In practice, this means that part of becoming more confident and content with yourself is to approach situations empty-handed where you normally use precautions. Only by doing this will you discover that your precautions are unnecessary – you can get what you want out of life without them.

It is possible, on occasion, that your performance is quite genuinely disrupted by anxiety. You find yourself stammering, you can see your notes shaking in your hand or your mind genuinely does go blank. These things happen, even to accomplished speakers. Supposing something like this happened to you: what would your reaction be? What thoughts might come into your mind?

People with robust self-esteem might observe the signs of nervousness with interest or detachment rather than fear, and see them as an understandable reaction to being under pressure. They might believe that to be nervous under these circumstances is quite normal, and be pretty confident that their anxiety was much less evident to other people than it was to them, and that even if others noticed, they would not make much of it. In short, as far as confident people are concerned, being anxious does not matter particularly. Their personal rules accommodate a less than perfect performance, and they would not see it as having any real significance for their worth.

If you have low self-esteem, however, then you are likely to see any difficulties or imperfections as evidence of your usual uselessness, incompetence, or whatever. That is, they say something about you as a person. Naturally enough, this also feeds into keeping low self-esteem going. Life being what it is, you will not always operate as you might wish to do. A part of overcoming low self-esteem is to begin to view your weaknesses and flaws – the things you do not do particularly well and the mistakes you make – as simply a part of yourself and an aspect of being human, rather than a reason for condemning yourself as a total person.

Despite your anxieties, your presentation might in fact go just fine. You say what you wanted to say, people seem interested, your nervousness does not get out of hand, there are some interesting questions and you find good answers to them. Supposing this happened to you: what would your reaction be? Would you feel good about yourself – you did a good job, and you deserve a pat on the back? Or would you have a sneaking suspicion that you did it by the skin of your teeth: the audience were just being kind, you were lucky, or the stars were on your side? But next time . . .

Even when things go well, low self-esteem can undercut your pleasure in what you achieve and make you likely to ignore, discount or disqualify anything that does not fit with your prevailing negative view of yourself. The ‘prejudice’ against yourself described in Chapter 2 prevents you from taking in and accepting evidence that contradicts it. So part of overcoming low self-esteem is to begin to notice and take pleasure in your achievements and in the good things in your life. Chapter 6 will focus in detail on how to go about this.

Whether you avoid challenging situations altogether, hedge them about with unnecessary precautions, condemn yourself as a person because they did not go well, or discount and deny how well they actually did go, the end result is a sense that your negative beliefs about yourself have indeed been confirmed. You were absolutely right – you are useless, inadequate, unlovable or whatever it may be. You may actually say this to yourself in so many words – ‘There you are, I always knew it, I am simply not good enough.’ Or confirmation of the Bottom Line may be reflected more in a feeling (sadness, despair) or a change in body state (a heaviness, a sinking in your stomach). Whatever the form confirmation takes, the essential message is that what you always knew about yourself has been proved yet again – you are indeed the person you always thought you were. And the process may not stop there.

The sense that your negative ideas about yourself have been confirmed often leads to a spate of self-critical thoughts. ‘Self-critical’ here does not mean a calm observation that you have done something less well than you wanted, or attracted a negative reaction from someone, followed by considering if there is anything constructive you might want to do to put things right. It means condemning yourself as a person. Self-critical thoughts may just flash briefly through your mind, before you turn your attention to something else. Or you may find yourself trapped in a spiralling sequence of attacks on yourself, perhaps in quite vicious terms. Here is what Jesse (the boy whose father quizzed him at the supper table) said to himself when his computer crashed and he lost an important document he was rushing to complete to deadline:

Now look what you’ve done. You are a complete and total idiot. How could you be so stupid? You always mess things up – absolutely typical. You’ll never amount to anything – you simply haven’t got what it takes. Why are you always so useless? Why can’t you get anything right? You’re a waste of space.

Something which was actually not at all his fault was taken by Jesse to confirm his negative ideas about himself. Because he assumed the crash was all down to something integral to his personality, it also seemed to him to have major implications for his future – it would always be this way. You can probably imagine the mixture of frustration and despair which Jesse experienced at that point, and how difficult it was for him to set about putting the situation calmly to rights.

Self-critical thoughts, like anxious predictions, have a major impact on how we feel and how we deal with our lives. They contribute to keeping low self-esteem going. Think about your own reactions when things go wrong or do not work out as you planned. What runs through your mind in these situations? Are you hard on yourself? Do you put yourself down and call yourself names, like Jesse? Learning to detect and answer your self-critical thoughts, and to find a more realistic and kindly perspective, is part of overcoming low self-esteem. Chapter 5 will focus in detail on how to do this.

When Jesse’s computer crashed, he completely abandoned his project. He felt really down, completely fed up with himself. He just wanted to shut himself away and lick his wounds. He simply couldn’t make himself get started again. He had been due to go away at the weekend with some friends, but he couldn’t face it. He told everyone he was ill, and sat around at home doing nothing in particular. He couldn’t even be bothered to watch television. With nothing else to occupy his mind, he began to brood about the future. He couldn’t see any real prospect that things would change, so what was the point of carrying on?

Self-critical thinking affects mood. Consider this for yourself. How do you feel when you are putting yourself down or being hard on yourself? What effect does it have on your motivation to problem-solve and tackle difficulties you may have in your life? Being critical of yourself, especially if you believe that what you criticize in yourself is a permanent part of your make-up and cannot change, will pull you down into depression. This may be only a momentary sadness, swiftly banished by spending time with people you care about, or by engaging in an absorbing activity. Or it may develop and snowball – as Jesse’s began to do – into a serious depression which may be quite hard to get out of. If this has become the case for you, you may need to address the depression in its own right before you begin to tackle low self-esteem (see Chapter 1 for information on how to recognize depression that might need treatment).

Whether the dip in mood is transitory, or whether it is difficult to shift, depression completes the vicious circle. We know from research into cognitive therapy that depression in itself has a direct impact on thinking. Once you become depressed, whatever the reason for your dip in mood, the depression itself will make you more likely to indulge in self-critical thinking, and to view the future with gloom and pessimism. So depression keeps the Bottom Line activated, and sets you up to continue to predict the worst. Bingo! You have a self-maintaining process which is quite capable of continuing to cycle, if you do not interrupt it, for long periods of time.

As you have made your way through this chapter, you have been asked from time to time to consider how you personally might react in particular situations, to reflect on your own anxious predictions and their impact on your emotional state and your behavior, your own sense that your negative beliefs about yourself have been confirmed, your own typical self-critical thoughts, and the impact these have on how you feel and how easy it is to manage your life to your own satisfaction. If you have not already done so, now is the chance to bring together your observations by drawing up your own vicious circle. As an illustrative example, you will find the circle Jesse drew up after his computer crashed on page 78.

Start by thinking of a type of situation in which you reliably feel anxious and uncertain about yourself. Now look for a specific recent example. Make sure you select something that is still fresh in your mind, so that you will be able to recall accurately how you felt and thought in the situation. Follow the circle through, using the headings in the flow chart on page 78, and noting your own personal experiences and reactions under each heading. If you wish, when you have completed one circle, start from a different anxiety-provoking situation and repeat the process. By doing so, you are increasing your awareness of how your patterns of anxious and self-critical thinking operate to keep low self-esteem going. This is your first step to breaking the circle and moving on.

Figure 7 The vicious circle that keeps low self-esteem going: Jesse

In the chapters that follow, you will discover ways of breaking the vicious circle that keeps low self-esteem going. You will learn how to become aware of your own anxious predictions as they arise, how to question them, and how to test out their accuracy through direct experience, approaching situations you normally avoid and dropping unnecessary precautions, so that you can find out for yourself what is really going on. You will learn how to notice self-critical thinking and nip it in the bud, short-circuiting the development of depression. You will learn how to counter the bias against yourself by focusing on your skills, qualities, assets and strengths and by treating yourself to the good things in life. You will move on to changing the rules that make you vulnerable to entering the vicious circle when you break their terms, and finally you will pull together all the changes you have made and tackle your Bottom Line. Your objective throughout will be to overcome the low self-esteem that has been hampering your appreciation of yourself and your ability to enjoy your life to the full, and to develop and strengthen a new, more kindly and helpful perspective.