Self-image

Self-concept

Self-perception

Self-confidence

Self-efficacy

Self-acceptance

Self-respect

Self-worth

Self-esteem

All these words refer to aspects of the way we view ourselves, the thoughts we have about ourselves, and the value we place on ourselves as people. Each has slightly different shades of meaning.

‘Self-image’, ‘self-concept’ and ‘self-perception’ all refer to the overall picture a person has of him- or herself. These terms do not necessarily imply any judgment or evaluation of the self, but simply describe a whole range of characteristics. For example:

and

‘Self-confidence’ and ‘self-efficacy’, on the other hand, refer to our sense that we can do things successfully, and perhaps to a particular standard. As one self-confident person put it, ‘I can do things and I know I can do things’. For example:

‘Self-acceptance’, ‘self-respect’, ‘self-worth’ and ‘self-esteem’ introduce a different element. They do not simply refer to qualities we assign to ourselves, whether good or bad. Nor do they simply reflect things we believe we can or cannot do. Rather, they reflect the overall opinion we have of ourselves and the value we place on ourselves as people. Their tone may be positive (e.g. ‘I am good’, ‘I am worthwhile’) or negative (e.g. ‘I am bad’, ‘I am useless’). When the tone is negative, we are talking about low self-esteem.

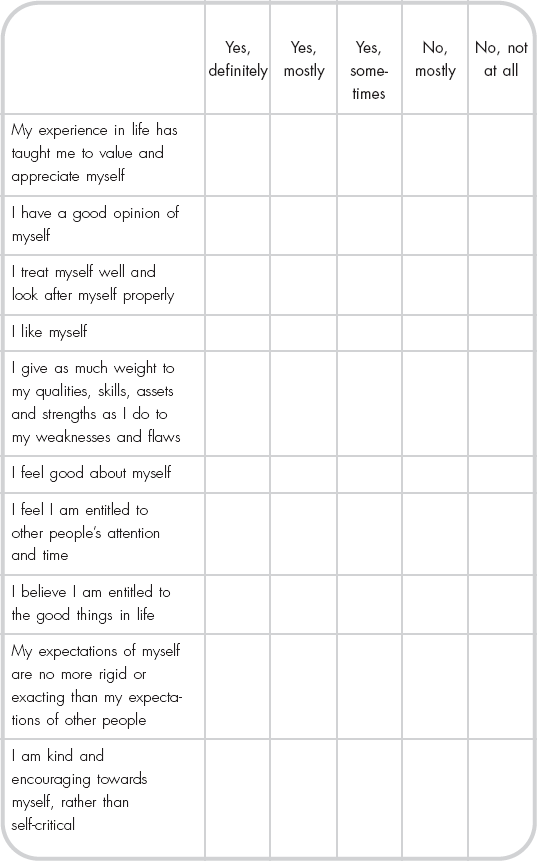

Take a look at the ten questions below. Put a tick next to each question, in the column that best reflects how you feel about yourself. Be honest – there are no right or wrong answers here, simply the truth about how you see yourself.

If your answers to these questions are anything other than ‘Yes, definitely’, then this book could be useful to you. If you are generally comfortable in accepting yourself as you are, if you have no real difficulty in respecting and appreciating yourself, if you see yourself as having intrinsic value and worth despite your human weaknesses, and feel entitled to take up your space in the world and to enjoy its riches, then you have the gift of self-esteem. You may still find ideas in this book that will interest you or open up avenues that you have not previously thought of, but any changes you make will be built on the solid foundation of a broadly positive view of yourself. If, on the other hand, you feel your true self to be weak, inadequate, inferior or lacking in some way, if you are troubled by uncertainty and self-doubt, if your thoughts about yourself are often unkind and critical, or if you have difficulty in feeling that you have any true worth or entitlement to the good things in life, these are signs that your self-esteem is low. And low self-esteem may be having a painful and damaging effect on your life.

‘Self-esteem’, then, refers to the overall opinion we have of ourselves, how we judge or evaluate ourselves, and the value we attach to ourselves as people. We will now consider in more detail the kind of impact low self-esteem can have on a person’s life. This will give you an opportunity to reflect on your own opinion of yourself, and what sort of value you place on yourself, as well as considering how your opinion of yourself affects your thoughts and feelings and how you operate on a day-to-day basis.

At the heart of self-esteem lie your central beliefs about yourself and your core ideas about the kind of person you are. These beliefs normally have the appearance of statements of fact. They may seem straightforward reflections of your identity, pure statements of the truth about yourself. Actually, however, they are more likely to be opinions than facts – summary statements or conclusions you have come to about yourself, based on the experiences you have had in your life, and in particular the messages you have received about the kind of person you are. So, to put it simply, if your experiences have generally been positive, your beliefs about yourself are likely to be equally positive. If your experiences have been pretty mixed (as most people’s are), then you may have a range of different ideas about yourself, and apply them flexibly according to the circumstances in which you find yourself. However, if your experiences have been generally negative, then your beliefs about yourself are likely to be equally negative. Negative beliefs about yourself constitute the essence of low self-esteem. And this essence may have coloured and contaminated many aspects of your life.

Negative beliefs about the self – which form the essence of low self-esteem – express themselves in many ways.

To get a sense of this, it may be useful to think about someone you know who you would say had low self-esteem. If you think you have low self-esteem, you could of course consider yourself at this point. But you may find it more helpful first of all to consider another person instead. This is because, if you try to look at yourself, it is often difficult to obtain a clear view – you are too close to the problem. Think now about the person you have chosen. Remember recent times when you have met. What happened? What did you talk about? How did your person look? What did they do? How did you feel with them? Try to get a really clear picture of them in your mind’s eye. Now the question is: how do you know that this person has low self-esteem? What is about them that tells you they have a problem in this area?

Jot down as many things as you can think of that give the game away. Look for clues in what your person says. For example, do you hear a lot of self-criticism, or apologies? What does this tell you about how your person thinks about him- or herself? Look at what your person does, including how he or she gets along with you and other people. For example, is he or she characteristically quiet and shy in company? Or conversely always rather pushy and self-promoting? What does this tell you? And what about self-presentation (posture, facial expression, direction of gaze)? Does he or she, for example, tend to adopt a hunched, inward-turned posture and avoid meeting others’ eyes? Again, what does this tell you about how he or she sees him- or herself? Think too about your person’s feelings and emotions. How does it feel to be him or her? Does he or she seem sad? Or fed up or frustrated? Or shy and anxious? What bodily sensations or changes might go with those emotions?

You will probably discover that clues are to be found in a number of different areas.

Negative beliefs about the self find expression in what people habitually say and think about themselves. Look out for self-criticism, self-blame and self-doubt; the sense that the person does not place much value on him- or herself, discounts positives and focuses on weaknesses and flaws.

Low self-esteem is reflected in how a person acts in everyday situations. Look out for telltale clues like difficulty in asserting needs or speaking out, an apologetic stance, avoidance of challenges and opportunities. Look out too for small clues like a bowed posture, downturned head, avoidance of eye contact, hushed voice and hesitancy.

Low self-esteem has an impact on emotional state. Look out for signs of sadness, anxiety, guilt, shame, frustration and anger.

Emotional state is often reflected in uncomfortable body sensations. Look out for signs of fatigue, low energy or tension.

Your observations show how holding a central negative belief about oneself reverberates on all levels, affecting thinking, behavior, emotional state and body sensations. Consider how this may apply to you. If you were observing yourself as you have just now observed another person, what would you see? What would be the telltale clues in your case?

Just as low self-esteem is reflected in many aspects of the person, so it has an impact on many aspects of life.

There may be a consistent pattern of underperformance and avoidance of challenges, or perhaps rigorous perfectionism and relentless hard work, fuelled by fear of failure. People with low self-esteem find it hard to give themselves credit for their achievements, or to believe that their good results are the outcome of their own skills and strengths.

In their relationships with others, people with low self-esteem may suffer acute (even disabling) self-consciousness, oversensitivity to criticism and disapproval, excessive eagerness to please – even outright withdrawal from any sort of intimacy or contact. Some people adopt a policy of always being the life and soul of the party, always appearing confident and in control, or always putting others first, no matter what the cost. Their belief is that, if they do not perform in this way, people will simply not want to know them.

How people spend their leisure time can also be affected. People with low self-esteem may avoid any activity in which there is a risk of being judged (art classes, for example, or competitive sports), or may believe that they do not deserve rewards or treats or to relax and enjoy themselves.

People with low self-esteem may not take proper care of themselves. They may struggle on when they feel ill, put off going to the hairdresser or the dentist, not bother to buy new clothes, drink excessively or smoke or use street drugs. Or, conversely, they may spend hours perfecting every detail of how they look, convinced that this is the only way to be attractive to other people.

Not everyone is affected to the same extent by central negative beliefs about the self. The impact of low self-esteem depends in part on its exact role in your life.

Sometimes a negative view of the self is purely a product of current mood. People who are clinically depressed almost always see themselves in a very negative light. This is true even for depressions which respond very well to antidepressant medication, and for those which have a strong biochemical basis. These are the recognized signs of clinical depression:

To be recognized as part of a depression that deserves treatment in its own right, at least five of these symptoms (including low mood or loss of pleasure and interest) should have been present consistently over an extended period (two weeks or more). That is, we are not talking here about the fleeting periods of depression that everyone experiences from time to time when things are rough, but rather about a mood state that has become persistent and disruptive.

If your current poor opinion of yourself started in the context of this kind of depression, then seeking treatment for the depression in its own right should be your first priority. Successfully treating the depression could even restore your confidence in yourself without you needing to work extensively on self-esteem. That said, you may still find some of the ideas in this book useful: especially Chapters 5, 6 and 7, which discuss how to tackle self-critical thoughts, how to focus on positive aspects of yourself and give yourself credit for your achievements, and how to change unhelpful rules for living. You may also find it helpful to consult another book in this series, Paul Gilbert’s Overcoming Depression.

Loss of self-esteem is sometimes a consequence of some other problem which causes distress and disruption in a person’s life. Long-standing anxiety problems, for example, including apparently uncontrollable panic attacks, can impose real restrictions on what a person can do, and so undermine confidence and lead to feelings of incompetence and inadequacy. Enduring relationship difficulties, hardship, lasting severe stress, chronic pain and illness can have a similar impact. All of these difficulties may result in demoralization and loss of self-esteem. In this case, tackling the root problem may provide the most effective solution to the problem. People who learn to manage panic and anxiety, for example, are often restored to previous levels of confidence without needing to do extensive work on low self-esteem in its own right. If this is your situation, and your low self-esteem developed as a consequence of some other problem, you may nonetheless find some useful ideas in this book to help you to restore your belief in yourself as swiftly and completely as possible. It could also be worth your while to consult other titles in this series to see whether any of them address your problems directly.

Sometimes low self-esteem, rather than being an aspect or consequence of current problems, seems rather to be the fertile soil in which they have grown. It may have been in place since childhood or adolescence, or as far back as the person can remember. Research has shown that low self-esteem (lasting negative beliefs about the self) may contribute towards a range of difficulties, including depression, suicidal thinking, eating disorders and social anxiety (extreme shyness). If this is true for you, if the difficulties you are currently having seem to you to reflect or spring from an underlying sense of low self-esteem, then working with current problems will undoubtedly be useful in itself, but will probably not produce significant or lasting changes in your view of yourself. And unless the issue of low self-esteem is tackled directly, in its own right, you are likely to remain vulnerable to future difficulties. In this case, you could benefit greatly from using this book as a guide to working consistently and systematically on your beliefs about yourself, undermining the old negative views and building up new and more helpful perspectives.

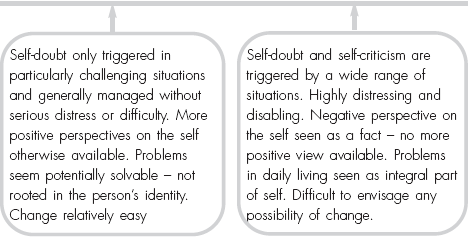

Whether low self-esteem is an aspect or consequence of other difficulties, or a vulnerability factor for them, the extent to which it impinges on life will vary from person to person. This point is illustrated on the following scale:

A person with low self-esteem might fall anywhere on this scale. At the left-hand end would be found people who experience occasional moments of self-doubt, usually under very specific conditions (for example, a job interview, or asking someone out for a first date). Such doubts interfere only minimally with people’s lives. They might feel mildly apprehensive in a challenging situation, but would have no real trouble managing the apprehension, would give it little weight, would find it easy to reassure themselves, and would not be held back from meeting the challenge successfully. When people like this have difficulties in life, they tend to see them straightforwardly as problems to be solved, rather than as a sign that there is something fundamentally wrong with them as a person. In addition to the negative perspective on the self triggered by challenges, they probably have other more positive and constructive alternative views, which influence how they feel about themselves most of the time. They may well find it easy overall to relate to other people, and feel comfortable about asking for help. Such people should find it relatively easy to isolate the situations in which they experienced self-doubt, consolidating and strengthening positive perspectives on the self which are already in place and learning quite rapidly to challenge anxious predictions about performance and to answer self-critical thoughts.

At the other end of the scale would fall people whose self-doubt and self-condemnation were more or less constant. For them, no more positive alternative perspective on the self is available. This is simply the way things are. The slightest thing is enough to spark off a torrent of self-critical thoughts. They find it hard to believe in their capacity to deal with any of life’s challenges, or to achieve lasting closeness to other people. Their fears and their negative beliefs about themselves may be powerful enough to cause widespread disruption in how they go about their lives – opportunities missed, challenges avoided, relationships spoiled, pleasures and achievements sabotaged, and self-defeating and self-destructive patterns of behavior in many areas. When people at this end of the scale have difficulties, rather than seeing these as problems to be solved, they tend to view them as central to their true selves (‘This is me’, ‘This is how I am’). So it is hard to step back far enough to see things clearly, or to work systematically to change things for the better without outside help. Even then, making progress can be tough, because it is difficult to have confidence in the possibility of change or to persist if improvement is slow in coming.

Most of us fall somewhere between these two extremes. This book may have limited relevance for people falling right at the left-hand end, though it could still be a useful source of handy tips for fine-tuning an already robust sense of self-confidence and self-worth. For those who fall at the far right-hand end of the scale, using the book on its own may not be enough. It could, however, be helpful as part of a program of therapy with a cognitive behavioral therapist. Its main use will be for the people who fall in the broad middle area of the continuum – people whose low self-esteem is problematic enough for them to wish to do something about it, but who have enough freedom of movement to be able to stand back from how they habitually see themselves and search for alternative perspectives.

You may be a person who is generally self-confident but suffers from occasional moments of self-doubt in particularly challenging situations. Or you may be someone who is plagued by self-criticism and finds it hard to think of anything good about yourself. The chances are, you are somewhere in between. Whatever the intensity and breadth of impact of your particular brand of low self-esteem, this book provides your road map for a journey towards self-knowledge and self-acceptance. It is intended to help you to understand the origins of your poor opinion of yourself, and to discover how unhelpful thinking habits and self-defeating patterns of behavior keep it going in the present day. You will learn how to use close self-observation as a basis for introducing changes designed to help you to challenge your negative sense of yourself and to develop a new, more kindly, respectful and accepting view.

You do not have to believe that this book will revolutionize your life and make a new person of you. The key things are:

Throughout the book, you will find plenty of opportunities to think about how you developed your poor opinion of yourself, and to reflect on how low self-esteem is affecting you on a daily basis. There are lots of practical exercises and record sheets, to help you apply what you read to your own personal situation. Exactly how you use the book will be up to you. You may decide to skip quickly through it, picking up one or two handy tips. Or you may decide, after you have skimmed the chapter headings, that it would be worth investing time and effort in working through the book systematically, carefully observing how you react in situations that trouble you so that you can change old patterns, rethink your normal strategies for getting by, undermine old, negative beliefs about yourself, and replace them with more helpful and realistic alternatives.

If so, you may find it most helpful to proceed one chapter at a time, since each introduces ideas and skills that will be useful to you as you proceed, and each is built on the foundations of the last. In this case, first read the chapter through quite quickly, to give yourself a general sense of what it is about. You can use this overview to notice stories and examples that ring bells for you, and to begin to consider how the chapter is relevant to you personally – after all, you are the expert on yourself. Then go back and read the chapter more carefully, in detail, completing the exercises as you go. Do not move on to the next chapter until you feel you have got a good grasp of the change methods introduced – a sense that you understand what they are and how to use them, and that you are beginning to get results. If you rush on, you risk completing nothing properly. In this case, the ideas presented will not be able to have any significant impact on how you feel about yourself. It takes the time it takes – and you are worth it.

If you do decide to work through the book systematically, it will take time. You will probably get most out of it if you set aside a certain amount of time every day (say, 20–30 minutes) to read, reflect, plan what to do and review your records. This is undoubtedly a real commitment, particularly as the book will sometimes ask you to think about events and issues that may be painful to you. However, especially if your doubts about yourself are long-standing and if they distress you and restrict your life, then the commitment could have a substantial payoff. There may be times when you get stuck and can’t think how to take things forward, or can’t find alternatives to your usual way of thinking. Don’t get angry with yourself or give up – put your work to one side for a time and come back to it later, when your mind has cleared and you are feeling more relaxed. You may also find it helpful to work through the book with a friend. Two heads are often better than one, and your stuck points may not be the same as his or hers. You may be able to help each other out, encouraging each other to persist, making sure you make the most of experiments in new ways of operating, sharpening your focus on positive aspects of the self, and thinking creatively about how to treat yourself like someone you value, love and respect.

This book will not help everyone who has low self-esteem. Sometimes a book is not enough. The most common way of dealing with things that distress us is to talk to someone else about them. Often, talking to a loved family member or a good friend is enough to relieve distress and move us forward. Sometimes, however, even this is not enough. We need to see someone professionally trained to help people in distress – a doctor, a counsellor or a psychotherapist. If you find that focusing on self-esteem is actually making you feel worse instead of helping you to see clearly and think constructively about how to change things for the better, or if your negative beliefs about yourself and about the impossibility of change are so strong that you cannot even begin to use the ideas and practical skills described, then it may be that you would do well to seek professional help. This is especially true if you find yourself becoming depressed in the way that was described earlier, or too anxious to function properly, or if you find yourself starting to contemplate self-defeating and self-destructive acts.

There is nothing shameful about seeking psychological help – any more than there is anything shameful about taking your car to a garage if it is not running properly, or going to see a lawyer if you have legal problems you cannot resolve. Seeking help means opening a door to the possibility of a different future. It means taking your journey towards self-knowledge and self-acceptance with the help of a concerned and friendly guide, rather than striking out alone. If you feel comfortable with the approach described in the book, its practical focus and emphasis on personal empowerment through self-observation and systematic change, then your most helpful guide might be a cognitive behavior therapist.

‘Cognitive behavior therapy’ is a form of psychotherapy that was originally developed in the United States by Professor Aaron T. Beck, a psychiatrist working in Philadelphia. It is an evidence-based approach with a solid foundation in psychological theory and clinical research. It was first shown to be effective as a treatment for depression in the late 1970s. Since then, it has broadened in scope, and is now used successfully to help people with a much wider range of problems, including anxiety, panic, relationship difficulties, sexual difficulties, eating problems (like anorexia and bulimia nervosa), alcohol and drug dependency, and post-traumatic stress. You will find other books in this series dealing with some of these problems.

Cognitive behavior therapy is an ideal approach for low self-esteem. This is because it provides an easily grasped framework for understanding how the problem developed and what keeps it going. In particular, cognitive behavior therapy focuses on thoughts, beliefs, attitudes and opinions (this is what ‘cognitive’ means) and, as we have already noted, a person’s opinion of him- or herself lies right at the heart of low self-esteem.

Do not assume, however, that understanding and insight alone are enough. Cognitive behavior therapy offers practical, tried-and-tested and effective methods for producing lasting change. It does not stop at the abstract, verbal level – it is not just a ‘talking therapy’. It encourages you to take an active role in overcoming low self-esteem, to find ways of putting new ideas into practice on a day-to-day basis, acting differently and observing the impact of doing so on how you feel about yourself (this is the ‘behavioral’ element).

This is a commonsensical, down-to-earth approach to fundamental issues. It will encourage you to attend to and alter broad ideas you have about yourself, other people and life. It will also encourage you to adopt an experimental approach to how you behave in everyday situations, trying out new ideas in practice at work, with your friends and family, and in how you treat yourself, even when you are at home all on your own. The cognitive behavioral approach empowers you to become your own therapist, developing insight, planning and executing change, and assessing the results for yourself. The new skills you develop and practise will continue to be useful to you for the rest of your life.

The end result could be changes in all the areas we identified at the beginning of the chapter:

Chapter 2 explores in greater detail where low self-esteem comes from. It will allow you to consider what experiences in your life have contributed to the way you see yourself, to see how the view you have of yourself makes perfect sense, given what has happened to you.

Chapter 3 homes in on what keeps old negative perspectives going in the present day, and how out-of-date thinking habits and unhelpful patterns of behavior work together in a vicious circle to block the development of self-esteem.

Chapter 4 suggests a first way of breaking out of the circle, showing you how to become aware of and to question negative predictions which make you anxious, restrict what you can do, and so contribute to low self-esteem.

Chapters 5 and 6 complement one another. Chapter 5 will teach you how to catch and answer self-critical thoughts, thus undermining your negative perspective on yourself. Chapter 6 offers ways of actively creating and strengthening a more positive view.

Chapter 7 moves on to consider how to change your rules for living, the strategies you have adopted to compensate for low self-esteem.

Chapter 8 discusses ways of working directly on the central view of yourself which lies at the heart of low self-esteem.

Finally, Chapter 9 suggests ways of summarizing and consolidating what you have learned, and how you might go about taking things further if you wish to do so.

You will notice that direct methods for changing your beliefs about yourself come last. This may seem odd. Surely shifting your negative beliefs about yourself should be the first thing you do? The fact is that it is usually easiest to change long-standing beliefs if you start by considering how they operate in the present day. It is interesting and useful to understand how they developed, but what most needs to change is what keeps them in place. Changing a fundamental view of yourself (or indeed of anything else) may take weeks or months. So, by starting work at this broad, abstract level, you would be attempting the most difficult thing first. This could slow you down and might even be rather discouraging.

In contrast, changing how you think and act from moment to moment can have an immediate impact on how you feel about yourself. It may be possible to make radical changes within days. Working on your thoughts and feelings in everyday situations will help you to clarify the nature of your beliefs about yourself, and the impact they are having on your life. It will form a firm foundation for dealing with the bigger issues at a later stage. It may well also have an impact on your central negative beliefs about yourself, even before you begin to work on them directly. This is particularly likely to be the case if, as you go along, you keep asking yourself questions like:

You may well find that small changes you make in your thinking and behavior will gradually chip away at the boulder of your central negative beliefs about yourself. You may even find that, by the time you reach Chapter 8, that boulder will be too small to need anything more than a few final blows. Even if you have not reduced it to this extent, the work that you have done in undermining negative thinking and focusing on the positive will stand you in good stead when you come to tackle the big, abstract issues. Chapter 8 quite explicitly draws on the work that has been done earlier in the book. This means that you will get most benefit from it when you have absorbed the ideas and skills covered in earlier chapters.

Good luck. Enjoy your journey!