8

Undermining the Bottom Line

Introduction

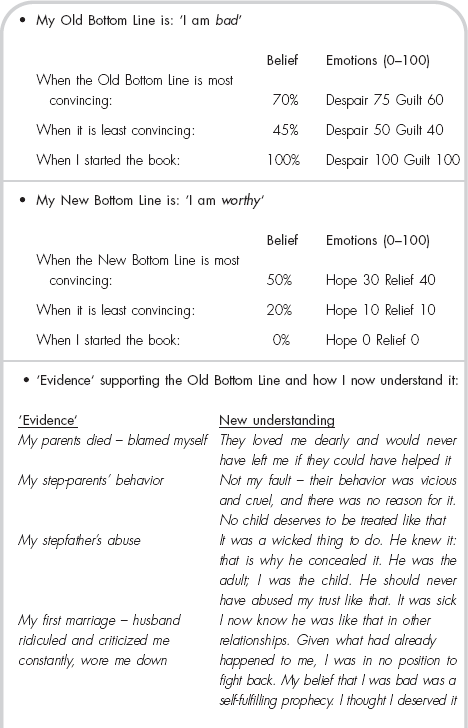

You have now laid the foundations for tackling your Bottom Line, the negative beliefs about yourself that lie at the heart of low self-esteem. Chapter 2 described how these beliefs develop. They are understandable conclusions you reached, probably as a child, on the basis of experience – opinions, not facts. Once established, they are kept in place by biases in how you perceive and interpret what happens to you, and by unhelpful Rules for Living which are designed to help you cope in the world (given the apparent truth of the Bottom Line), but which in fact merely wallpaper over your insecurities while leaving them intact. Chapter 3 described how the Bottom Line is activated in situations where your personal rules are in danger of being broken, giving rise to a vicious circle fuelled by anxious predictions and self-critical thoughts.

Chapters 4 to 7 have addressed the key elements that keep low self-esteem in place, one by one. You have learned how to check out anxious predictions, how to combat self-critical thoughts, and how to focus on your good points and treat yourself like a person who deserves the good things in life. You have formulated new, more realistic and helpful rules for living, and begun to put them into practice.

You may find that, by the time you have completed these chapters and reduced the impact of your Bottom Line on everyday life, your ideas about yourself have already changed. It may be that your old, negative Bottom Line already seems less convincing than it did, even though you have not yet challenged it directly.

Some people find that, once they have broken the vicious circle that keeps low self-esteem going and started acting in accordance with more realistic Rules for Living, the problem of low self-esteem is pretty much resolved. Others find it harder to use specific day-to-day changes in thinking and behavior to alter entrenched negative beliefs about themselves. However things stand for you at this point, this chapter will help you to consolidate what you have learned and bring it to bear on your Bottom Line.

The objective is to help you to formulate a new, more appreciative and kindly view, capitalizing on the work you have already done to help you take the final steps in your journey towards self-acceptance. These steps are:

Identifying the Bottom Line

As you have made your way through the book, you may already have gained a very good sense of what your Bottom Line is. This section will present some possible sources of information to help you identify it clearly (a summary is on page 257). You may find it helpful to consider each source of information in turn. Each will give you a slightly different take on things, so that your idea of what your Bottom Line might be will become increasingly clear.

Even if you are already pretty sure, reviewing this section will give you an opportunity to confirm your hunches, fine-tune the wording and perhaps discover other negative beliefs about yourself that you were less aware of. It is quite possible that you have more than one Bottom Line (like Sarah, who saw herself as both unimportant and inferior). If so, do as you did with your Rules for Living. Choose the Bottom Line that seems most important to you, the one that you would most like to change, and use the chapter to work systematically on that. You can then use what you have learned to change other negative beliefs about yourself if you wish (and, indeed, to change unhelpful negative beliefs you may have about other people, the world in general and life).

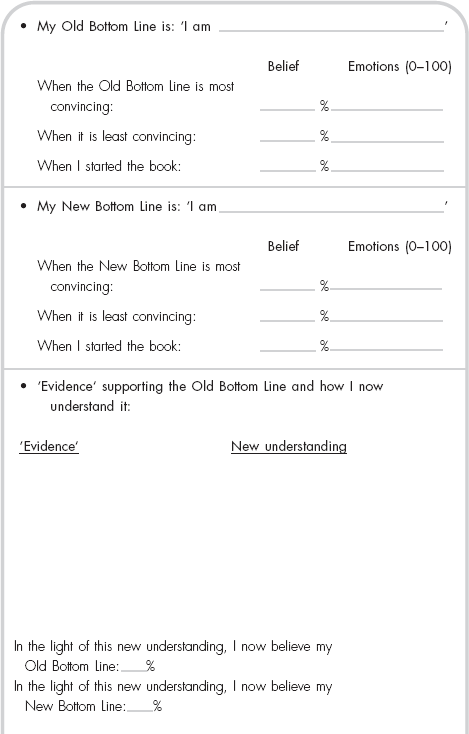

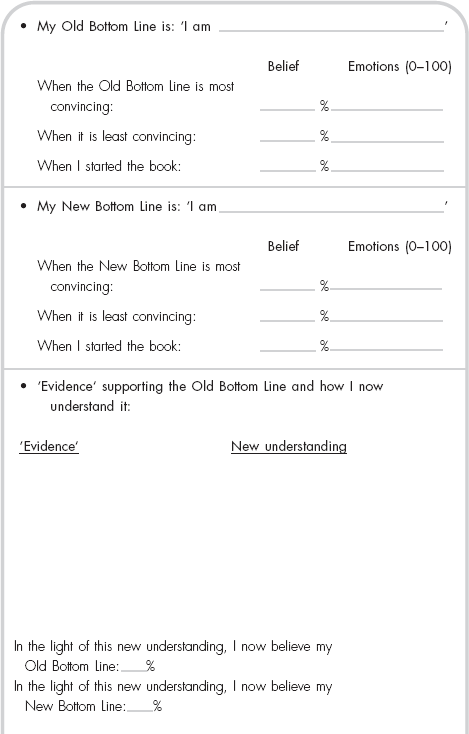

Write down whatever hunches about your Bottom Line come to mind as you consider each potential source of information. When you feel you have a clear sense of what it is, summarize it for yourself (‘My Bottom Line is: “I am”). You may find it helpful to use the Summary Sheet outlined and illustrated at the end of the chapter. Then rate how far you believe it (0–100 per cent), just as you rated belief in your anxious and self-critical thoughts. One hundred per cent would mean that you still find it fully convincing, 50 per cent that you are in two minds, 5 per cent that you now hardly believe it at all, and so on.

You may notice that how far you believe your Bottom Line varies. If your self-esteem is relatively robust, you may find that your Bottom Line only becomes convincing in particularly challenging situations. If so, make two ratings: how far you believe it when it is at its strongest, and how far you believe it when it is least convincing. Alternatively, you may find that your Bottom Line is more or less consistently present and convincing. In this case, you may only need one rating, or the difference between most convincing and least convincing may be smaller.

You may also find that your degree of belief has changed since you began to work on overcoming low self-esteem. This is especially likely if you have systematically followed through the ideas for change described in previous chapters. If this is the case for you, write down how far you believed your Bottom Line before you started the book, and how far you believe it now. Consider too what accounts for any changes you have observed. Was it learning to face things that frightened you and discovering the worst did not happen? Was it learning to escape the trap of self-critical thinking? Was it making the effort to focus on what is strong and good in yourself, and beginning to treat yourself like someone who deserves the good things in life? Or was it the work you did on formulating new rules for living and putting them into practice? Or perhaps it was some combination of these. If you can spot what helped, this will tell you what you need to continue doing for yourself.

When you have rated your degree of belief, take a moment to focus on your Bottom Line and notice what feelings emerge, just as you observed your feelings when you learned to spot anxious and self-critical thoughts. Write down any emotions you experience (e.g. sadness, anger, guilt), and rate them according to how powerful they are (0–100). Again, you may notice that, although you can still call up your Bottom Line, your feelings when you focus on it have changed. If the Bottom Line is now less convincing to you than it was, then your distress when you contemplate it should also be less intense.

Sources of information on your Bottom Line

Your knowledge of your own history

When you read the stories of the people described in Chapter 2, did any of them ring bells for you? Did any of the experiences described echo experiences you had when you were growing up? Even if not, did you find yourself thinking back to when you were young and remembering things that happened to you, and the impact they had on how you felt about yourself?

You can use these memories to clarify your Bottom Line, just as you may have used memories of earlier times to help you to identify your Rules for Living. In particular, consider:

Figure 31 Identifying the Bottom Line: Sources of information

• Your knowledge of your own history

• The fears expressed in your anxious predictions

• Your self-critical thoughts

• Thoughts that make it hard for you to focus on your good points and treat yourself like someone who deserves the good things in life

• The imagined consequences of breaking your old rules

• The downward arrow

The fears expressed in your anxious predictions

Think back to the work you did on your anxious predictions. It could be that your fears, and the unnecessary precautions you took to keep yourself safe, will give you clues about your Bottom Line.

Your self-critical thoughts

Look back over the work you did on combating your self-critical thoughts. These thoughts may be a direct reflection of your Bottom Line.

Thoughts that make it hard to accept your good points and treat yourself like someone who deserves the good things in life

Examine the doubts and reservations that came to mind when you were trying to list your good points and observe them in action, when you attempted to give yourself credit for your achievements and treat yourself kindly. Difficulties you experienced in these areas could well reflect the fact that they were not a good fit with your prevailing, negative view of yourself. Jesse, for example, recognized on reflection that his reluctance to give himself credit for what he did or allow himself time to relax reflected his belief that he was simply not good enough.

The imagined consequences of breaking your old rules

In Rules for Living (page 214), sometimes the ‘then . . .’ that follows an ‘if . . .’ or an ‘unless’ is more or less a direct statement of the Bottom Line (e.g. ‘If I make mistakes, then I am a failure’). Go back to the rules you identified, and look at what you imagined would result from breaking them.

The downward arrow

You can use the ‘downward arrow’ technique (pages 226–29) to identify your Bottom Line. The process is much the same as the process of identifying Rules for Living, but the sequence of possible questions has a different emphasis and is designed to focus your attention on your negative beliefs about yourself, rather than your standards and expectations. The main change is to enquire what each level of questioning says about you, rather than what it means to you in terms of how you should behave and the sort of person you should be.

As before, start from a specific incident when you felt bad about yourself. Write down the thoughts and feelings that you experienced – again, it may be helpful to focus particularly on the thought which is most powerful and accounts for most of the emotion you experienced. Then, rather than searching for alternatives to your thoughts, ask yourself a sequence of questions, for example:

It may be helpful to use a range of different questions to help you find your Bottom Line. You are looking for a blanket statement about yourself (‘I am __________’), which not only applies in the situation you are working with, but more broadly across the board. Do not stop at a specific self-critical thought, which is true at a particular moment. You should recognize your Bottom Line as an opinion you have held about yourself over time and across many different situations. You may wish to confirm your findings (or have another go, if you are having trouble finding the Bottom Line, or putting it into words) by using a number of different situations in which you typically feel bad about yourself as your starting point. You will find an example of a downward arrow leading to a Bottom Line on pages 262–3 (Briony).

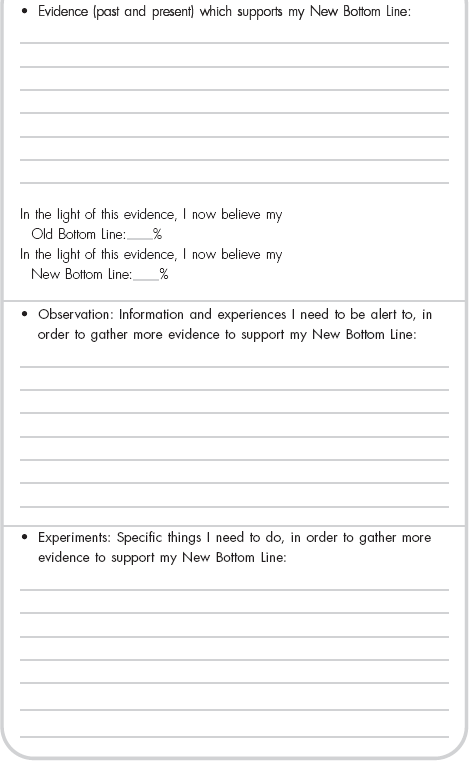

Creating a new Bottom Line

Once you have identified your Bottom Line, it is worth moving on right away to formulate a more positive and realistic alternative to it, even before you begin to think it through and undermine it. This is because, over time, you have probably accumulated a sizeable bank account of experiences that seem to you to support your Bottom Line, given the biases in thinking and memory that keep low self-esteem in place. You can call on your ‘Old Bottom Line Account’ any time you want to, add new deposits, withdraw items and dwell on them like a miser counting and recounting money.

In contrast, you may not even have a ‘New Bottom Line Account’. Or, if you have, it may be more or less empty, and difficult to access. Items get lost in transfer, and you keep forgetting your account number and code. This means that you have nowhere safe, solid and lasting to put ‘New Bottom Line’ deposits.

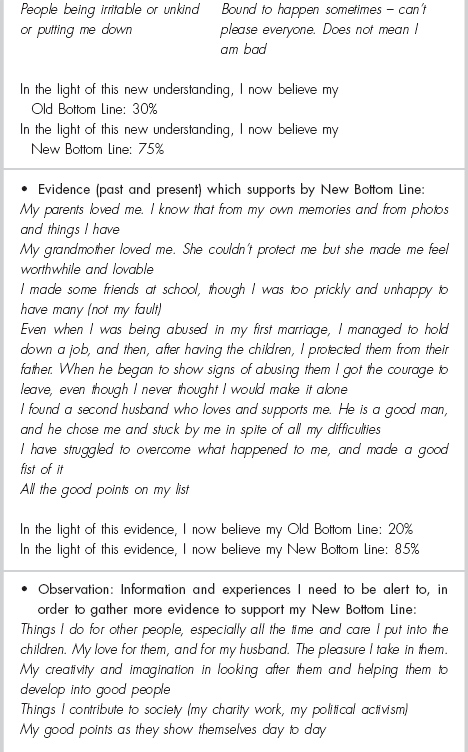

Figure 32 The downward arrow: Identifying the Bottom Line – Briony

Situation: New friend promised to phone and did not do so

Emotions: Sick to my stomach, despairing

Thought: He’s forgotten

If that was true, what would it mean about you?

That I’m not worth remembering

And what would that tell you about yourself?

That he’s backed off because he’s seen the real me

If he had, what would he have seen?

Something he didn’t like

What would that be? What would he not like?

The real me, that doesn’t deserve to be liked

If that was true, what would it say about you as a person?

I’m bad

Creating a New Bottom Line opens an account in favour of yourself. It gives you a place to store experiences that contradict the Old Bottom Line and support a new, more kindly perspective. You have somewhere you can keep positive aspects of yourself safe, knowing that you can call on them when you need them.

Another way of putting this is to imagine that you have an address book with the names and contact numbers only of people who dislike you and put you down. People who like you, care about you and respect you have no place in your address book. Imagine the consequences if this was really the case. The contact numbers of people who encouraged you to feel good about yourself would be on scrappy bits of paper. They would get lost, or accidentally thrown away, or fall down behind the fridge. You might try to rely on your memory but, with so many other things to attend to, you would forget. In the end, you might not even bother to make a note of their names and numbers at all. You would know there was little point. If you wanted to start getting a more balanced perspective on how people felt about you, your first step would have to be to get yourself a new address book for the people who were on your side.

These two analogies illustrate the purpose of formulating a New Bottom Line. It gives you somewhere to put positive information about yourself, experiences that support a more appreciative point of view. This means that you are not merely attempting to undermine your old, negative beliefs (‘Maybe I’m not completely inadequate, after all’), but actively setting up an alternative and beginning to scan for information and experiences which support it (‘Maybe I am adequate instead’).

The work you have already done in earlier chapters, besides providing you with information about your Old Bottom Line, may also have given you some idea of what your preferred alternative might be. As you have worked through the book, checking out anxious predictions, combating self-critical thoughts, focusing on positive aspects of yourself and changing your rules, what new ideas about yourself have come to mind? When you look back over all you have done in each of these areas, what do the changes you have made tell you about yourself? Are they entirely consistent with your old negative view?

Look in particular at the qualities, strengths, assets and skills you have identified and observed, day to day. Do they fit with your Old Bottom Line? Or do they suggest that it needs updating, that it is a biased, unfair point of view which fails to take account of what is good and strong and worthy in you? What perspective on yourself would better account for everything you have observed? What New Bottom Line would acknowledge that, like the rest of the human race, you are short of perfect, but that along with your weaknesses and flaws you have strengths and qualities?

You are the judge and jury here, not the counsel for the prosecution. Your job is to take all the evidence into account, not just the evidence in favour of condemning the prisoner.

When you have a sense of what it is, write down your New Bottom Line (on the Summary Sheet at the end of the chapter, if you wish). Rate how far you believe it, just as you rated your belief in your Old Bottom Line, including variations in how convincing it seems to you and how your belief has changed since you began to work on overcoming your low self-esteem. Then take a moment to focus your attention on it, and note what emotions come up and how strong they are. As you continue through the chapter, come back to the Summary Sheet from time to time, and observe how your belief in the New Bottom Line changes as you focus on evidence which supports and strengthens it.

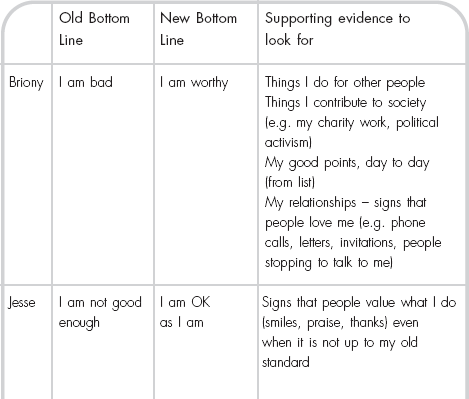

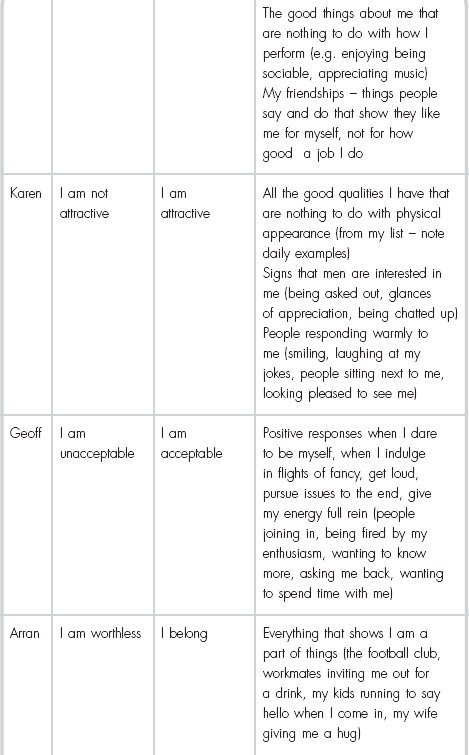

Looking at the examples on page 294, you will see that the New Bottom Line is sometimes simply the opposite of the old one (e.g. Karen, Geoff, Kate). In some cases, on the other hand, the New Bottom Line ‘jumps the tracks’, as it were, and goes off in a new direction which makes the old one almost irrelevant (e.g. Briony, Arran, Chris). Sometimes the New Bottom Line is somewhere between these (e.g. Jesse, Sarah, Jim). The point here is that your New Bottom Line should reflect a point of view that makes sense to you personally, will eventually change how you feel about yourself, and offers opportunities for a fresh perspective on your experiences which will allow you to begin noticing and giving weight to good aspects of yourself. The wording is yours.

You may find a New Bottom Line immediately springs to mind when you think back over everything you have done. Or you may find that your mind is pretty much a blank, especially if your low self-esteem has been in place for a long time and you have a strong taboo on thinking well of yourself which still needs to be challenged.

Do not worry if this is the case. Your ideas may become clearer as you work through the chapter. For the moment, it may be helpful to ask yourself a question that Christine Padesky, a cognitive therapist, suggests: ‘If you were not ____ (your Old Bottom Line), what would you like to be?’ For example, ‘If I were not incompetent, I would like to be competent.’ If you can come up with an answer to the question, however tentative, then even if it seems largely theoretical to you at the moment, write it down. It will give you a starting point for collecting evidence in favour of a new perspective (in this case, ‘I am competent’), even if it does not yet seem at all convincing to you. Conviction may come as you continue to work through the chapter.

You may find that, at this point, old ideas about the inadvisability of thinking well of yourself surface. Remember that we are not talking here about having an inflated self-image (‘I am totally wonderful in every way’, ‘Every day in every way I am getting better and better’). You are not being advised to forget your human weaknesses and flaws, to ignore aspects of yourself which you would like to change or improve on and pretend that they do not exist. This book is not about the power of positive thinking, or about encouraging you to become as unrealistically positive about yourself as you were unrealistically negative. It is about achieving a balanced, unbiased view of yourself which puts your weaknesses and flaws in the context of a broadly favourable perspective, and cheerleads for ‘good enough’ rather than ‘perfect’.

It is unlikely that you will ever be 100 per cent lovable, 100 per cent competent, 100 per cent worthy, 100 per cent intelligent, 100 per cent attractive, or whatever. Why, after all, should you be the only member of the human race, ever, who is? The work you have been doing and will do asks you to make your flaws and weaknesses simply a part of yourself, rather than a basis for your assessment of your worth. You may decide you can live with them, or you may decide you wish to change them – it is up to you.

To make this point clearer, let us consider it in relation to ‘likeable’. Imagine a 10 cm line representing likeability:

Someone at the right hand end of the line would be 100 per cent likeable. Superficially, this might appear to be a good thing. Someone at the left hand end would be 0 per cent likeable. Right now, put a ‘x’ on the line where you think you fall. If you have doubts about how likeable you are, you probably fall towards the left-hand end of the line. Now let us consider what ‘100 per cent likeable’ and ‘0 per cent likeable’ would actually mean. In order to be ‘100 per cent likeable’, you would have, for example:

It will be immediately clear that 100 per cent likeable is just not possible. Nobody could be such a paragon. Think about people you know. With the extremes (0 and 100 per cent) clearly in mind, where would you put them on the line? And, again, keeping the extremes in mind, where would you now put yourself? When you decide on your New Bottom Line, keep this point in mind. You are not looking for the unattainable 100 per cent, you are looking for ‘good enough’.

Do not worry if, at the moment, your degree of belief in your New Bottom Line is low. If the Old Bottom Line has been in place for some considerable time, it will take time, patience and practice to make the new one powerfully convincing. We shall now move on to consider how to undermine your Old Bottom Line further, and how to strengthen the new one you have tentatively identified. You will find that the work you have already done will stand you in good stead here.

Undermining the Old Bottom Line

Your negative beliefs about yourself are based on experience. They represent your attempt to make sense of things that have happened to you in the past. This means that, given the biases in thinking and memory that keep them in place, as you look back over your life you will find ‘evidence’ that appears to support them. Examining this ‘evidence’ – and searching for other ways to explain it – is the next step towards overcoming low self-esteem. This is similar to the skills you have already acquired when you learned to combat self-critical thoughts, and the ideas you used at that point may also be helpful to you here. However, the scale is broader: the focus is on your general beliefs about yourself, rather than on specific thoughts that arise at a particular moment in time. The key questions to bear in mind are:

What ‘evidence’ supports your Old Bottom Line?

I have put ‘evidence’ in quotation marks here to indicate that, although you may have accepted a range of experiences as support for your Old Bottom Line, signs that what you believed about yourself was indeed true, these experiences may in fact be open to quite different interpretations. It could be that, if you look at them closely, you will realize that they do not reflect badly on you at all. The first step towards understanding this is to identify the experiences you have been taking as supporting evidence.

Reflect for a moment on your Old Bottom Line. What experiences, past and present, come to mind? What events appear to support it? What makes you say that you are inadequate, unlikeable, incompetent, or whatever your Bottom Line may be? What leads you to reach such negative conclusions about yourself?

Supporting ‘evidence’ varies from person to person. Sometimes most of it is located in the past, in relationships or experiences like those described in the stories in Chapter 2. More recent events can also be used as sources of evidence. Some common sources of ‘evidence’ are described and summarized below. As you read, see if any of the ‘evidence’ rings bells for you.

The list is not exhaustive. The ‘evidence’ that you have used to back up your poor opinion of yourself may not be on it. Use this section nonetheless as an opportunity to reflect on what it might be. Bear in mind that you may well be using more than one source of ‘evidence’ to support your Old Bottom Line, and make a note of as many as you can find. Your next task will be to stand back and examine the ‘evidence’ carefully. When you take a good look at it, does it really confirm your negative view of yourself, or could it be understood in a different way?

Current difficulties and symptoms of distress

Briony, for example, became quite depressed at one point. As is characteristic of people who are depressed, she became lethargic and found it hard to gear herself up to do anything. Briony took this to mean that she was a lazy good-for-nothing. In other words, it was yet another sign of what a bad person she was, rather than a temporary symptom of an understandable state which would disappear once her mood lifted.

Figure 33 Sources of ‘evidence’ supporting the old, negative Bottom Line

• Current difficulties and symptoms of distress

• Failure to manage alone

• Past errors and failures

• Specific shortcomings

• Personal characteristics, physical or psychological

• Differences between yourself and other people

• Other people’s behavior towards you, past or present

• The behavior of others for whom you feel responsible

• Loss of something which was a part of your identity

Failure to overcome current difficulties alone

Jim’s difficulty in talking openly to his wife and asking for outside help is an example of this. He saw being unable to manage independently as a sign of weakness, rather than a sensible recognition that two heads are sometimes better than one.

Past errors and failures

Given human frailty, it is impossible to get through life without doing things one regrets. From time to time, we are all selfish, thoughtless, irritable, short-sighted or less than fully honest. We all take short cuts, make mistakes, avoid challenges and fail to achieve objectives. Such normal human weaknesses are often seen by people with low self-esteem as yet further evidence of their fundamental inadequacy.

This was true for Arran. During his teens, he often operated on the fringes of the law. At times, he took part in fights in which other people were hurt, once very badly. He was repeatedly in trouble with the police and appeared in court more than once. As he got older, Arran decided that this way of life was doing him no good. He was afraid to change, however, as this seemed to him the only way to survive in a hostile world. Still, he found the courage to move away from his home city, made new friends and found a job he liked, and eventually married and had children of his own. Despite these very positive changes, he still found it hard to feel good about himself. His past haunted him. Whenever he looked back, he felt utterly worthless.

Specific problems

No one is perfect. We all have shortcomings and aspects of ourselves that we would like to change or improve. People with low self-esteem may see these shortcomings as further proof that there is something fundamentally wrong with them, rather than as specific problems which it might be possible to resolve and which bear no relation to their real worth. Every time Chris had problems with reading or writing, for example, he saw this as further evidence of his stupidity, rather than as an unrecognized specific learning difficulty which was no reflection of his intelligence and which, with proper help, could be overcome.

Physical characteristics

People with low self-esteem may feel that they are too tall, too short, too fat, too thin, the wrong colour, the wrong shape or the wrong build. They may use these observations to undermine their sense of self-esteem. Karen’s belief that her worth depended on how she looked and what she weighed is an example of this. If her weight exceeded what she thought it should be, she immediately felt completely fat, ugly and unattractive. Nothing else counted. She ignored all the other things that made her attractive – for example, her sense of style, her ability to enjoy life and her intelligence.

Psychological characteristics

Psychological characteristics too can lead people with low self-esteem to feel bad about themselves. Geoff, for example, even as an adult, was afraid that his high energy, curiosity and inventiveness would be seen as showing off. Expecting disapproval and criticism, he did what he could to blend in, become part of the furniture, and dampen himself down. Instead of accepting his qualities as gifts, he saw them as further evidence that he was unacceptable.

Differences between yourself and other people

However talented you are, it is likely that there are other people who are more talented. However much you have, there are probably others who have more. People with low self-esteem may use comparisons with other people as a source of evidence to support their poor opinions of themselves. Sarah, for example, was always comparing her work to other artists’. In these comparisons, she usually felt she came off worst. Rather than judging herself on her own merits, regardless of what other people did, she used negative comparisons to fuel her sense of inferiority.

Other people’s behavior towards you, past or present

People who were treated badly as children may see this treatment of evidence of their own lack of worth, whether the treatment came from family, schoolmates or the society in which they lived. Equally, dislike, rejection, disapproval or abuse in the present day can be used to bolster low self-esteem. For example, the treatment she had received from her step-parents was Briony’s main source of evidence that she was bad. Why else would they have been like that? Even as an adult, if someone treated her badly, her immediate assumption was that she must have deserved it in some way. So any unkindness or lack of consideration or disagreement became further evidence of her essential badness.

The behavior of others for whom you feel responsible

This is a particular trap for people with low self-esteem who become parents. They may blame themselves for anything that goes wrong in their children’s lives, even long after the children have grown up and left home. This was true for Briony. When she discovered that her adolescent daughter had occasionally taken street drugs at parties, her immediate reaction was that this must be entirely her fault. She was a bad parent. Her own essential badness had somehow leaked out and contaminated her daughter. This perspective made it difficult for her to handle the situation constructively, to discuss with her daughter the possible consequences of what she was doing, and how best to resist peer pressure.

Loss of something which was a part of your identity

Chapter 7 (pages 212–3) showed how people hang self-esteem on a range of different pegs. If the peg on which you have hung your sense of worth is taken away, this exposes you to the full force of negative beliefs about yourself. Jesse, for example, was made redundant because the firm he worked for was going through hard times. His work was one of the pegs he had hung his self-esteem on. Although the company made it clear that they had no wish to lose him, he took the redundancy very personally. It was another sign that he was not good enough.

How else can the ‘evidence’ be understood?

Each source of ‘evidence’ that is used to support the Bottom Line is open to different interpretations, just as specific self-critical thoughts that run through your head in particular situations are open to different interpretations. Once you have identified the evidence that you feel backs up your Old Bottom Line, your next task is to examine it carefully and assess how far it truly supports what you have been in the habit of believing about yourself. Write down your conclusions on the Summary Sheet at the end of the chapter.

You may find the questions that follow (summarized below) useful to you. You will see that they relate directly to the various sources of evidence outlined above. It may also be worth your while to bear in mind the questions you used to tackle self-critical thoughts (pages 145–55). The particular questions that make sense to you will depend on the nature of the ‘evidence’ you use to support your Old Bottom Line.

Figure 34 Reviewing the evidence that supports your old Bottom Line: Useful questions

• Aside from personal inadequacy, what explanations could there for current difficulties or signs of distress?

• Although it is useful to be able to manage independently, what might be the advantages of being able to ask for help and support?

• How fair is it to judge yourself on the basis of past errors and failures?

• How fair is it to judge yourself on the basis of specific shortcomings?

• How helpful is it to let your self-esteem depend on rigid ideas about what you should do or be?

• Just because someone is better at something than you, or has more than you do, does that make them better as a person?

• What reasons, besides the kind of person you are, might there be for others’ behavior towards you?

• How much power do you actually have over the behavior of people you feel responsible for?

Aside from personal inadequacy, what other explanations could there be for current difficulties or signs of distress?

If this is a time when you are having difficulties or experencing distress, rather than taking this as a sign that there is something fundamentally wrong with you, look at what is going on in your life at the moment. Is anything happening that might make sense of how you are feeling? If someone you cared about was going through what you are going through right now, might they feel similar? If so, what would you make of that? Would you assume that they, too, must be inadequate, bad or whatever? Or would you consider their reactions to be understandable, given what was going on? Even if nothing very obvious is happening in your life right now to explain how you feel, could it be understood in terms of old habits of thinking which are a result of your past experiences? If so, then perhaps you will find it more helpful to be kindly and understanding to yourself, to encourage yourself to do whatever needs to be done and to get whatever help you need, rather than making things worse by using how things are as a stick to beat your back with.

Although it is useful to be able to manage independently, what might be the advantages of being able to ask for help and support?

Like Jim, you may feel that asking for help is a sign of weakness or inadequacy. You should be able to stand on your own two feet. But perhaps being able to ask for help when you genuinely need it actually puts you in a stronger position, not a weaker one, because it may give you a chance to deal successfully with a wider range of situations than you could manage on your own. How do you feel when other people who are in difficulties come to you for help or support? Do you automatically conclude they must be feeble or pathetic? People who have difficulties in asking for help themselves are often very good at giving help to others. They do not judge others adversely. On the contrary, being able to offer help makes them feel useful, wanted and warm towards the person who needs them. This is how other people who care about you might feel about you, if you gave them half a chance.

Alternatively, you may fear (like Kate) that if you ask for help, you will be disappointed. Other people may take a dim view of it. They may refuse, or be scornful, or not be able to give you what you need. It makes sense to select people who you have no strong evidence to suppose will react in this way. That aside, the best way to test out how others will react is to try it. Work out your predictions in advance and check them out, just as you learned to do in Chapter 4.

How fair is it to judge yourself on the basis of past errors and failures?

People with low self-esteem sometimes confuse what they do with what they are. They assume that a bad action is a sign of a bad person, or that to fail at something means to be a failure in a much more global sense. If this were true, no one in the world could ever feel good about themselves. We may regret things we have done (like Arran), but it is not helpful or accurate to move on from that to complete self-condemnation. If you do one good thing, does that make you a totally good person? If you have low self-esteem, you are unlikely to believe this. But you may make the same mistake when you do something wrong.

The belief that you are thoroughly bad, worthless, inadequate, useless or whatever may act as a self-fulfilling prophecy, making it difficult to make reparation for things you regret or to consider calmly how to change things for the better – what’s the point, if it is dyed in the wool? Understanding your past failings in terms of natural human error and early learning may be more constructive. It will allow you to treat yourself more tolerantly – to condemn the sin but not the sinner.

This is not the same as letting yourself off the hook. It is a first step towards putting right whatever needs to be put right, and thinking about how you might avoid making the same mistakes in future. What you did may have been the only thing you could do, given your state of knowledge at the time. Now you can see things differently, so take advantage of your broader current perspective. And remember: you may have done a bad or stupid thing, but that does not make you a bad or stupid person.

How fair is it to judge yourself on the basis of specific shortcomings?

Just because you have difficulty asserting yourself, or being punctual, or organizing your time, or talking to people without anxiety, does it follow that there is something fundamentally wrong with you as a person? Having something about yourself that you would like to improve makes you part of the human race. If you are using specific difficulties as a basis for low self-esteem, you may be employing a double standard (see page 150). Would you judge another person with the same specific difficulty in the same way? If not, experiment with using a more tolerant approach to yourself. Again, it may help you to move forward rather than miring you in self-criticism.

Remember that your shortcomings, whatever they are, are only one side of you (your list of positive qualities may already have begun to make this clear). Albert Ellis, the originator of a form of psychological treatment called ‘Rational Emotive Therapy’, has used an analogy to convey this point. Imagine a basket of fruit. In the basket are a magnificent pineapple, some good apples, a rather mediocre orange or two, a bunch of grapes with the bloom still fresh upon them, some pears which are probably past their best and, lurking underneath, a banana which is completely black and rotten. Now, the question is: how do you judge the basket as a whole? It is impossible to do so. You can only judge its contents one by one. The same is true of people. You cannot judge them as a whole – you can only judge individual aspects of them, and individual things they do.

How helpful is it to let your self-esteem depend on rigid ideas about what you should do or be?

Hanging self-esteem on particular pegs, which may well not be under your control, inevitably makes you vulnerable to low self-esteem. You may have always been aware that your self-esteem was based on a particular aspect of yourself (e.g. your ability to make people laugh, your physical strength, or your capacity to earn a high salary). Or you may have only recognized what you depended on after you had lost it (e.g. you are aging, your physical beauty has dimmed, you have retired, your family have left home). You need now to ask yourself what your worth depends on, apart from the one thing you have decided is your be-all and end-all.

Your list of positive qualities may be a useful starting point here. Take another look at it. How many of the qualities, strengths, skills and talents on the list depend on the peg you usually hang your self-esteem on? If you find it difficult to get a clear perspective on this, think about people you know, like and respect. Write down what attracts you to them. When you consider why you value each person, how important is the one thing your own self-esteem depends on?

Karen found this line of enquiry very helpful in reassessing the contribution of her physical appearance to her self-esteem. Many of the positive qualities she had listed about herself (sense of style, ability to enjoy life, intelligence) bore no relation to her weight or shape. On the other hand, she could see how these qualities might be compromised by the belief that only weight and shape mattered. It was difficult to enjoy life, for example, when she was preoccupied with eating and not eating.

She also made a list of people she liked and respected, and wrote down what she saw as attractive in each one. She had some admiration for people who were thin and fit, but it was outweighed on a personal level by other qualities such as sense of humour, sensitivity, thoughtfulness and common sense. Compared to these, physical appearance was trivial. Karen concluded that she would do better to accept and appreciate herself just as she was, fat or thin, rather than making how she thought about herself dependent on some irrelevant standard.

Just because someone is better at something than you, or has more than you do, does it make them better than you as a person?

The fact that some people are further along a particular dimension than you are (competence, beauty, material success, career progression), does not make them any better than you as people. It is impossible to be best at everything. And (apart from very specific comparisons like height, weight and income) people cannot meaningfully be compared, any more than volcanoes and porcupines can be compared. Your sense of your own worth is best located within yourself, regardless of how you stand in relation to other people.

What reasons, besides the kind of person you are, might there be for others’ behavior towards you?

People with low self-esteem often assume that if others treat them badly or react to them negatively, this must in some way be deserved. This can make it difficult to set limits to what you will allow others to do to you, to feel entitled to others’ time and attention, to assert your own needs, and to end toxic relationships that damage you and stand in the way of feeling better about yourself.

Taking what others think of you, or how they behave towards you, as a measure of your personal worth does not make sense for a number of reasons. For example:

There are many possible reasons why people behave as they do. In the case of the particular person (or people) whose behavior to you seems to back up your Old Bottom Line, what reasons could there be? For example, it could be that their own early learning has made it difficult for them to behave any differently (just as children who are abused or treated violently often become abusers or violent themselves). It could be that they are behaving badly for purely circumstantial reasons (stress, pressure, illness, fear). It could be that, without them necessarily being aware of it, you remind them of someone they do not get on with. It could be that you are simply not their cup of tea. It could be that there is nothing personal about how they treat you – their manner is critical or sharp or dismissive with everyone, not just with you.

If you find it difficult to detach yourself from your usual self-blaming perspective and to think of other reasons why people behave towards you as they do, observe how you explain bad behavior or unkindness towards people other than yourself. For example, in recent years, child abuse has jumped into the headlines. When a case is reported, do you always immediately assume that the child in question must have been to blame? Or do you place responsibility squarely on the adult abuser? Similarly, if you read about intimidation, persecution, rape or assault, is it your automatic conclusion that the person on the receiving end must have deserved it? Or can you see that the perpetrator is responsible for what he or she did? Do you consider that civilian victims of war are to blame for their fate? Or do you see them as innocent victims of violence carried out by others for their own reasons? In each of these cases, is it your automatic reaction to explain what happened in terms of something wrong with the person treated badly – it must in some way be their fault? Or do you explain what happened in some other way? If so, try applying similar explanations to your own experiences.

How much power do you actually have over the behavior of people you feel responsible for?

To feel bad about yourself because someone you feel responsible for is not OK assumes a degree of power over others which, realistically, you may not have. At the relatively trivial end of the scale, if you have a supper party, you can make your home warm and welcoming, you can provide good food and drink, you can play music you know your guests are likely to appreciate, and you can ask a mix of people who you have good reason to believe will get on with one another – but you cannot guarantee that everyone will enjoy themselves. Only they can do that.

To take the more serious example of Briony’s daughter, there is much Briony can do to show how distressed she is, to explain to her daughter why what she is doing may cause her harm, and to help her to think for herself rather than going along with the crowd. But she cannot (without completely removing the independence her daughter needs as a young adult) organize 24-hour surveillance and forbid her to leave the house. In other words, Briony is responsible for managing the situation in the most caring and careful way she can, but she cannot ultimately be responsible for what her daughter does when elsewhere – she simply does not have that much power.

Try to be clear about the limits of your responsibility towards other people, in the sense of separating out what you can realistically do to influence them from what is beyond your control. It is reasonable partly to base your good opinion of yourself on your willingness to meet your responsibilities. It is not reasonable to base your self-esteem on things over which you have no control.

Summary

When you have identified the evidence you use to support your Old Bottom Line and found other ways of understanding it, return to the Summary Sheet at the end of the chapter and briefly note your findings in writing. Then, once again, rate how far you believe your Old and New Bottom Lines, and how you feel when you consider them. Can you see any change? If so, what made a difference? If not, is it that you have not yet discovered a convincing alternative way of interpreting the ‘evidence’? Or is there more ‘evidence’ that you have not yet addressed? If so, have another try.

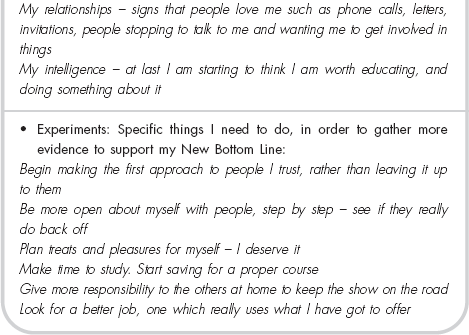

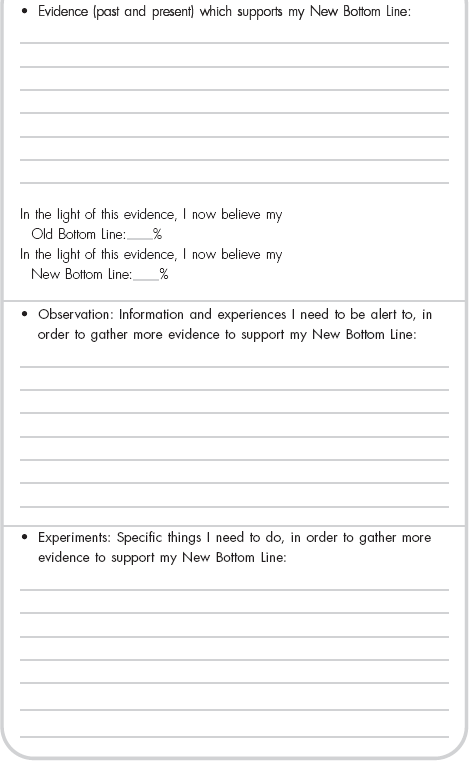

What evidence supports the New Bottom Line and contradicts the old one?

You have identified the evidence you have used to back up your Old Bottom Line, weighed it up and looked for other ways of interpreting or explaining it. The other side of the equation is to seek out evidence that directly contradicts the Old Bottom Line and supports your new alternative. (If you have not yet defined an alternative, stick with looking for evidence that is not consistent with your Old Bottom Line.) These two different angles on undermining the Old Bottom Line are equivalent to answering self-critical thoughts and focusing on your good points. They complement each other. Additionally, just as your work on self-criticism may have helped you to re-evaluate the evidence supporting the Old Bottom Line, so the work you have done on highlighting your strengths, skills and qualities and becoming more aware of them on a day-to-day basis will help you to look in a more focused way for information that supports your New Bottom Line.

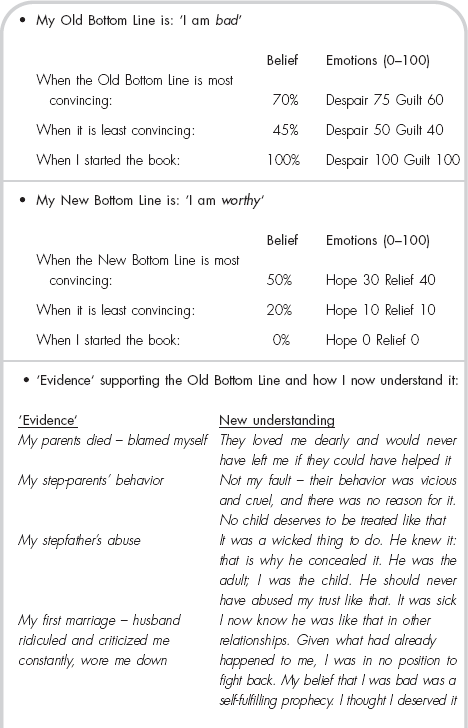

There are two main ways of collecting new evidence that supports the New Bottom Line and contradicts the old one: observation, and behavioral experiments.

1 Observation

Chapter 2 (pages 53–55) described how the Old Bottom Line is kept in place by systematic biases in perception. These make it easy for you to notice and give weight to information consistent with the Bottom Line, while encouraging you to screen out or dismiss information which contradicts it. You have already worked on correcting this bias when you made your list of good points and set about recording examples of them in practice. You now need to consider how to go about seeking out and recording information which directly contradicts your Old Bottom Line, and supports a more generous view of yourself.

It is important to have a clear sense of exactly what you are looking for before you begin your observations, just as you learned to be specific about what you feared might happen when you were checking out anxious predictions. Otherwise, you may waste time on observations that have no real relevance to the issue you are working on, and so will do nothing to weaken the Old Bottom Line and strengthen the New. You may also miss information that could genuinely have made a difference.

The information (or evidence) you need to look for will depend on the exact nature of your Bottom Line. If, for example, your Old Bottom Line was ‘I am unlikeable’ and your New Bottom Line is ‘I am likeable’, then you would need to collect evidence that supported the idea that you are indeed likeable (for example, people smiling at you, people wanting to spend time with you, or people saying that they enjoyed your company). If, on the other hand, your Old Bottom Line was ‘I am incompetent’ and your New Bottom Line is ‘I am competent’, then you would need to collect evidence that supported the idea that you are indeed competent (for example, completing tasks to deadline, responding sensibly to questions, or handling crises at work effectively).

In order to find out what information you personally need to look for, make a list of as many things as you can think of in answer to the following related questions:

and, conversely:

Make sure the items on your list are absolutely clear and specific. If they are vague and poorly defined, you will have trouble deciding if you have observed them or not. This is why ‘likeable’ and ‘competent’ above have been broken down into small elements, rather than left as global terms which might mean different things to different people.

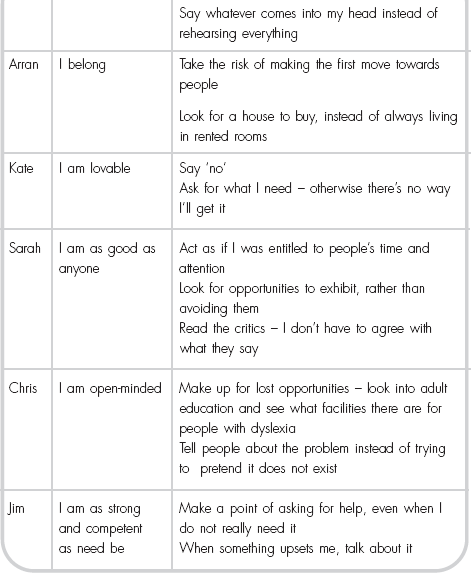

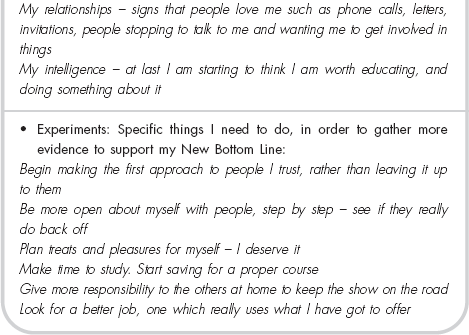

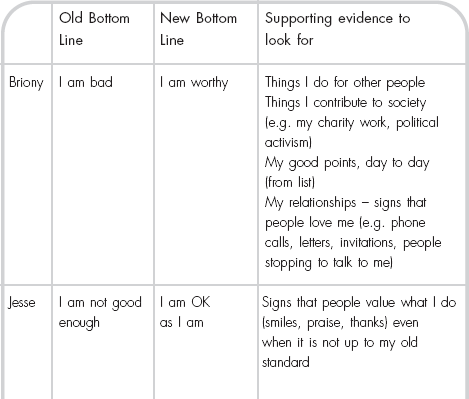

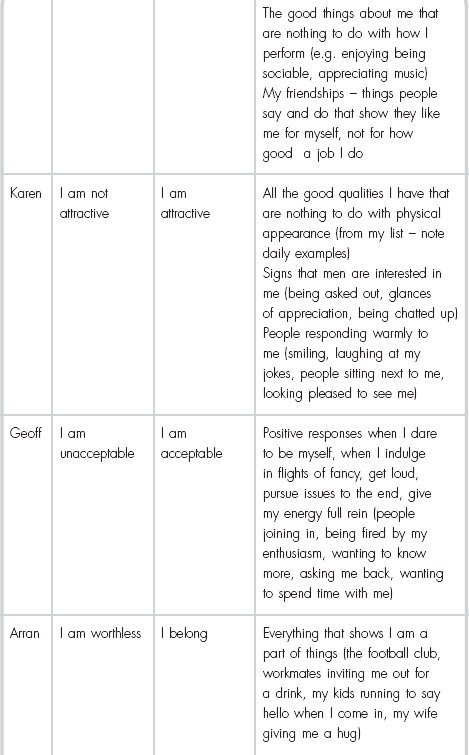

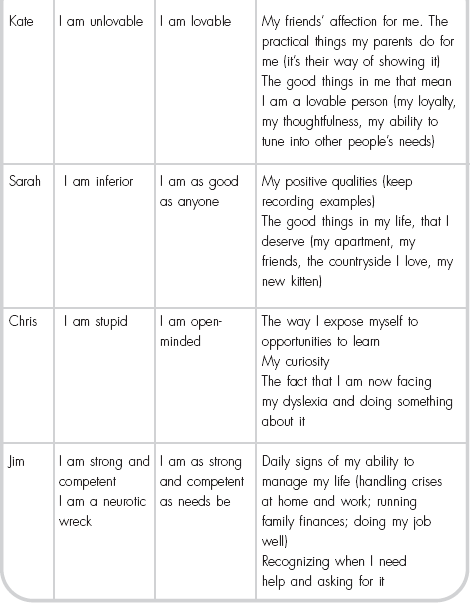

To give you some sense of what the possibilities are, here are examples from the people you first met in Chapter 2. They are a result of each person thinking carefully about what exactly would count as supporting evidence for his or her New Bottom Line.

Figure 35 Evidence to support the New Bottom Line: Examples

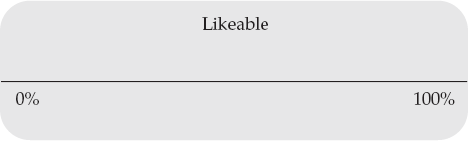

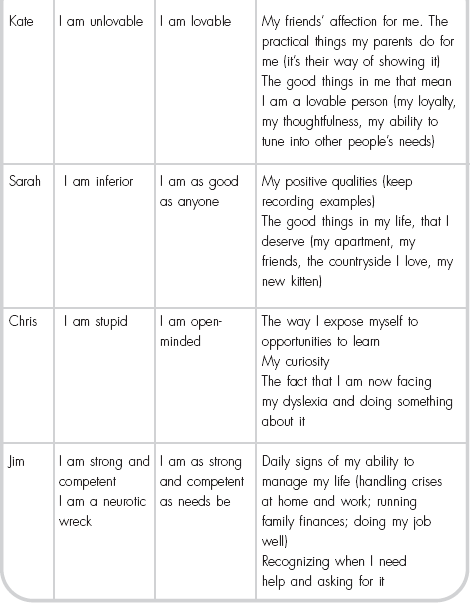

2 Behavioral experiments

You have already gained experience of how to set up and carry out experiments to test the validity of anxious predictions, to act against self-critical thoughts, and to test-drive new Rules for Living. Now is the time to push back the walls of the prison low self-esteem has built around you, by experimenting with acting as if your New Bottom Line was true. Despite the work you have already done on rethinking your old position, you may still feel uncomfortable or even fearful of doing this. Notice what thoughts run through your mind when you contemplate operating differently, when you feel apprehensive about entering new situations, and perhaps also when you have succeeded in being your new self and then afterwards begin to doubt how well it went. The chances are, you will find anxious predictions and self-critical thoughts behind these feelings. If so, you know what to do about them.

Once again, the experiments you need to carry out depend on the exact nature of your New Bottom Line. Consider what experiences would confirm and strengthen your new perspective on yourself. What do you need to do in order to discover that this new perspective is useful and rings true? Remember the situations you found yourself avoiding when you were working on anxious predictions, and the situations where you felt you needed to use unnecessary precautions. You have experimented with approaching what you avoided and dropping your precautions – how does what you discovered fit here? What other experiments could you carry out on similar lines?

Equally, consider the changes you made when you were learning to treat yourself kindly and build rewards and pleasures into your life. How does that fit with what you are doing now? Are there are other similar things you could do now to bolster your belief in your New Bottom Line? Or more of the same?

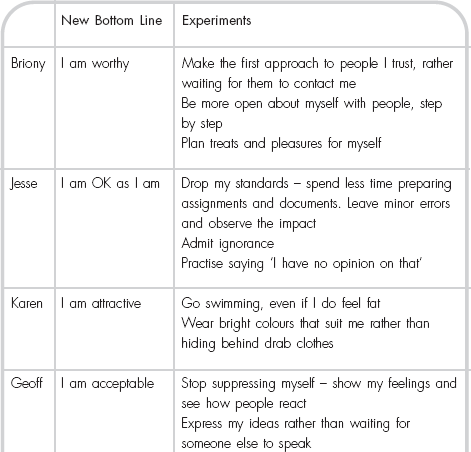

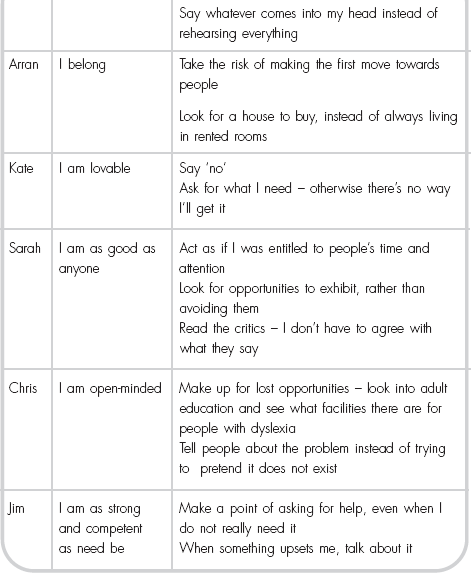

Work out in detail what someone who believed your New Bottom Line would do, how they would operate on a day-to-day basis. Make a list of as many things as you can think of in different areas of life – work, leisure time, close relationships, social life, looking after yourself. Then translate your list into specific experiments and begin to put them into practice in your daily life. Here are some more examples, to give you a sense of the variety of experiments that is possible.

Figure 36 Building a New Bottom Line – behavioral experiments: Examples

Summary

It will be important to record what you observe at this stage. Make sure, too, that you assess the outcome of your experiments carefully, just as you assessed the outcome of experiments when you checked out your anxious predictions. Keeping a careful record of what you notice and of exactly what you did and how it turned out will allow you to accumulate information consistent with your New Bottom Line. You could, for example, write this information down in your Positives Notebook, along with examples of your good points. If you do not record it, it may be forgotten or lost, and will not be available to you in the future when you feel doubtful about yourself.

To conclude, turn again to the Summary Sheet at the end of the chapter, and summarize what you have discovered by seeking out evidence consistent with your New Bottom Line. Then once again rate your belief in both the old and the new, and assess their impact on your feelings. Repeating these ratings regularly as you continue to undermine your Old Bottom Line and collect evidence in favour of your New Bottom Line will allow you to see how they continue to change, over time.

Taking the longer view

Building and strengthening a New Bottom Line does not happen overnight. It may take weeks (or even months) of systematic observation and experimentation before you find the alternative you have identified fully convincing. You have accumulated a lifetime of evidence that supports the Old Bottom Line, collected and stored it, mulled it over and mused on its implications for yourself. You will not need a similar lifetime of evidence in support for your New Bottom Line (that would be a discouraging thought!). But you should expect to make some investment in time and energy, some regular commitment to record-keeping and practice, in order to reach the point where thinking and acting in accordance with your New Bottom Line becomes second nature. When you reach this point, you will have made the final step towards overcoming low self-esteem. The final chapter of the book will give you some ideas on how to do this.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Figure 37 Undermining your Bottom Line: Summary sheet

Figure 38 Undermining your Bottom Line: Summary sheet – Briony