Anxious predictions and self-critical thoughts do not come out of the blue. As you learned in Chapter 3, they are usually the end result of underlying Rules for Living, often formed early in life and designed to help a person get by in the world, given the apparent truth of the Bottom Line. The purpose of rules is to make life more manageable. But in fact, in the long run, they stand in the way of getting what you want out of life, and prevent you from accepting yourself as you are.

Rules for Living are reflected on a day-to-day basis in strategies or policies, ways of acting which ensure that their terms are met. When you have low self-esteem, your personal rules determine the standards you expect of yourself, what you should do in order to be loved and accepted, and how you should behave in order to feel that you are a good and worthwhile person. Personal rules keep you on the straight and narrow. They may also detail the consequences if you fail to meet their terms.

Briony’s rule about relationships would be an example of this: ‘If I allow anyone close to me, they will hurt and exploit me.’ Since the consequences of breaking the rules are generally painful, you may have become exquisitely sensitive to situations where their terms might not be met. These are the situations which are likely to activate your Bottom Line, leading to the vicious circle of anxious predictions and self-critical thinking described in Chapter 3.

By now, you have discovered how helpful it is to check out anxious predictions and to combat self-critical thoughts. However, stopping at the level of day-to-day thoughts, feelings and actions and leaving your Rules for Living and your Bottom Line untouched might be equivalent to dealing with weeds in your garden by chopping their heads off rather than digging up their roots. This chapter will tell you how to go about identifying your own personal rules. It will help you to see how they contribute to low self-esteem, and suggest how to go about changing them and formulating new rules, which will allow you more freedom of movement and encourage you to accept yourself, just as you are.

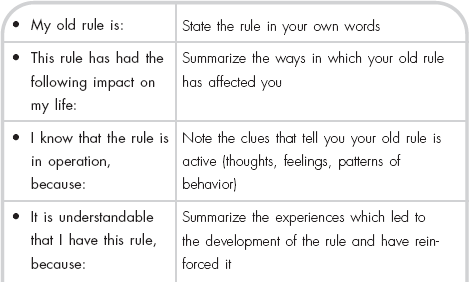

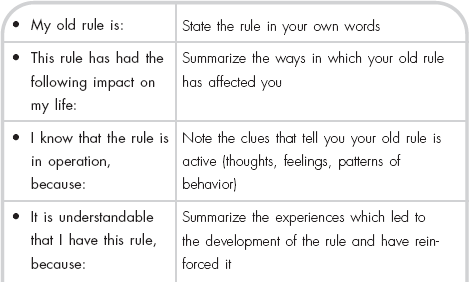

As you work through the chapter, it is worth summarizing in writing what you discover about your rules, your line of argument when you question them, your new rule and your action plan for putting it into practice. You will find some suggested headings on page 203, and an example of a summary on page 208. The headings echo the questions you will find later on in the chapter, and will help you to organize your thoughts in a form that you can come back to and use to ensure that new understanding has a practical impact on your life. This is important because unhelpful rules for living can be difficult to change. A line of argument which seems crystal clear to you when you work through the chapter may become hazy and difficult to grasp next time you are in a problem situation and have real need of it. A written summary will help you to keep your new perspective in view and make it easier for you to act on it, even when the going gets tough.

Rules can be helpful. They help us to make sense of what happens to us, to recognize repeating patterns, and to respond to new experiences without bewilderment. They can even help us to survive (e.g. ‘I must always look both ways before crossing the road’). Rules are part of how society is organized. National constitutions, political ideologies, legal frameworks, religious beliefs, professional ethics and school codes of behavior – all these are rules.

Figure 24 Changing the rules: Headings for a written summary

Parents pass on rules to their children, so that they will be able to deal with life independently (e.g. ‘Make sure you eat a balanced diet’). Children also absorb rules from their families and parents purely by observation. They notice connections (e.g. ‘If I don’t tidy my room, Mum will do it for me’) and these can become a basis for more general rules (e.g. ‘If things go wrong, someone will be there to pick up the pieces’). They tune into expectations that may never be put into words. They notice what is praised and what is criticized, what brings a smile to a parent’s face and what causes a frown. All these experiences can become a basis for personal rules with a lasting impact on how people live their lives.

Helpful rules tend to be tried and tested, based on a solid foundation of experience. They are flexible, and allow the person to adapt to changes in circumstances and to respond differently to different people. So, for example, a person from one culture who travels to another will be able to adapt successfully to local social conventions, so long as their rules for how to relate to people are flexible and open. But if their social rules are rigid, and especially if they are viewed as the right way to behave, the person may run into difficulties.

Some rules, instead of helping us to make sense of the world and negotiate its demands successfully, trap us in unhelpful patterns and prevent us from achieving our life goals. They are designed to maintain self-esteem – in fact, they undermine it, because they place demands on us that are impossible to meet. They make no concessions to circumstances or individual needs (e.g. ‘You must always give 110 per cent, no matter what the cost’). These extreme and unbending rules create problems. They become a strait-jacket, restricting freedom of movement and preventing change.

Rules that make you vulnerable to low self-esteem may operate in many areas of life. They may determine the performance you expect of yourself in a range of different situations. Perfectionist rules like Jesse’s, for example, may not only require high-quality performance in the work environment, but might also require perfection in your physical appearance, in where you live or in how you carry out the most mundane of everyday activities.

Rules can restrict your freedom to be your true self with other people. Like Kate, you may have the sense that approval, liking, love and intimacy are all dependent on your acting (or being) a certain way. Rules may even influence how you react to your own feelings and thoughts. Like Jim, you may base your good opinion of yourself on being fully in control of your emotions, your thoughts and what life throws at you. Unhelpful rules like these imprison you. They build a wall of expectations, standards and demands around you. Here is your chance to break out.

Unhelpful rules are like escape clauses, ways around the apparent truth of the Bottom Line. For example, at heart, you might believe yourself to be incompetent. But so long as you work very hard all the time and set yourself high standards, you can override your incompetence and feel OK about yourself. Or you might believe yourself to be unattractive. But so long as you are a fount of funny stories, the life and soul of the party, maybe no one will notice and so again you can feel OK about yourself.

Rules like these can work very well, much of the time. For long periods, it may be possible to maintain your good opinion of yourself by obeying them. Unfortunately, however, there is a fundamental problem with this approach. Rules allow you to wallpaper over what you feel to be the real truth about yourself (your Bottom Line). But they do not change it. Indeed, the more successful they are, and the better you are at meeting their demands, the less opportunity they give you to stand back and take stock, question your Bottom Line, and adopt a more accepting and appreciative point of view. So the Bottom Line stays intact, waiting to be wheeled into place whenever your rules are in danger of being broken. You can see how this system worked for Jesse on page 208.

Unhelpful rules are rarely formally taught, but rather are absorbed through experience and observation. This is rather like a child learning to speak without learning the formal rules of grammar. As an adult, you speak grammatically (if not, you could not make yourself understood) but, unless you have made a special study of it, you are probably quite unaware of the grammatical rules you are obeying. Consequently, you might find it difficult or impossible to put them into words.

Figure 25 Rules for Living and the Bottom Line: Jesse

Bottom Line

I am not good enough

Rules for Living

Unless I get it right, I will never get anywhere in life If someone criticizes me, it means I have failed

Policy

Go for perfection every time Do everything you can to avoid criticism

Advantage

I do a lot of really good work and get good feedback for it

BUT: Problem

At heart, I still believe my Bottom Line 100 per cent Obeying the rules keeps it quiet, but it doesn’t go away

Plus:

However hard I try, it’s not possible to be perfect and avoid criticism all the time

The more I succeed, the more anxious I get.

I feel a fraud – any minute now, I’m going to fall off the tightrope. And whenever something goes wrong, or someone is less than wholly positive about me, I feel terrible – straight back to the Bottom Line.

Personal Rules for Living are often the same – you may consistently act in accordance with them, without having ever expressed them in so many words. This is likely to be because they reflect decisions you made about how to operate in the world, when you were too young to have an adult’s broader perspective. Your rules probably made perfect sense when you drew them up, but they were based on incomplete knowledge and the limited experience available to you at the time, and so may be out of date and irrelevant to your life in the present day.

Rules are part of our social and family heritage. Think, for example, about gender stereotypes, the rules society has evolved about what men and women should be like. We absorb these ideas from our earliest years and, even if we disagree with them, it may be difficult to act against them. We may be punished for attempting to do so by social disapproval. The difficulties women still have in progressing in the workplace, and the struggle to establish a meaningful role for men in childcare, would be examples of this.

Personal rules are often like exaggerated versions of the rules of the society we grew up in. Western society, for example, places a high premium on independence and achievement. In a particular individual, these social pressures might be expressed through rules like ‘I must never ask for help’ and ‘If I’m not on top, I’m a flop’. Social and cultural rules can change, and such changes (via the family) will have an impact on personal rules. In England, for example, the ‘stiff upper lip’ has traditionally been highly valued. In the individual, this might be expressed as: ‘If I show my feelings, people will write me off as a wimp’ or ‘Rise above it’. More recently, however, the influence of people like Princess Diana has emphasized the importance of openly expressing vulnerability and emotion. In the individual, this might become: ‘If I do not lay all my feelings on the table, it means I am hard and inhuman.’ The culture from which personal rules derive operates at all levels – political systems, ethnic and religious groups, class, community, school. Whatever your background, the chances are that your personal rules reflect the culture you grew up in, as well as your immediate family.

Although your rules may have much in common with those of other people growing up in the same culture, no one else will exactly share your experiences of life. Even within the same family, each child’s experience is different. However careful parents are to be fair to their children, each one will be treated a little differently, loved in a different way. So your rules are unique.

This is because they shape how you see things and how you interpret what happens to you on a day-to-day basis. The biases in perception and in interpretation discussed in Chapter 2 (pages 53–4) reinforce and strengthen them. Rules encourage you to behave in ways that make it difficult for you to discover just how unhelpful they are.

Think back to the work you have done on checking out anxious predictions. You saw how unnecessary precautions prevent you from finding out whether your fears are accurate. Rules work in the same way, but at a more general level. So Jesse, for example, not only strives to be ‘100 per cent great’ when completing his high profile assignment, but in a more general sense has perfectionist standards for everything he does. This means that he has no opportunity to discover that, given his natural talents and skills, he has no real need to place such pressure on himself.

When you have broken the rules, and when you are at risk of doing so, your emotions will be strong. You feel depressed or despairing, not sad. You experience rage, not irritation. You react with fear, not apprehension or concern. These powerful emotions are a sign that a rule is in operation, and that the Bottom Line is gearing up for activation. In this sense, they are useful clues. However, their strength may also make it difficult to observe what is going on from an interested and detached perspective.

Like anxious predictions and self-critical thoughts, personal Rules for Living do not match the facts. They do not fit the way the world works, or what can reasonably be expected of the average human being. Jesse (page 208) recognizes this point when he acknowledges that it is not always possible to be perfect or to avoid criticism. We shall return to this point in more detail when we come to reformulate your personal rules.

Unhelpful rules are over-generalizations. They do not recognize that what is helpful and adaptive changes according to the circumstances in which you find yourself. They do not respond to variations in time and place, or recognize that what works in one situation or at one time of your life will not work in another. This is reflected in their language: ‘always’/‘never’, ‘everyone’/‘no one’,‘everything’/‘nothing’. They prevent you from attending to moment-to-moment changes in your circumstances, from taking each situation on its merits, and from adopting a flexible approach and selecting the best course of action, according to your particular needs at a particular moment in time.

Rules are absolute; they do not allow for shades of grey. Again, this is reflected in their language: ‘I must . . .’, ‘I should . . .’, ‘I ought to . . .’, rather than ‘It would be in my interests to . . .’ or ‘I prefer . . .’; ‘I need . . .’ rather than ‘I want . . .’ or ‘I would like . . .’ This black-and-white quality may reflect the fact that they were developed when you were very young, before you had the breadth of experience to see things from a more complex perspective.

The sequence Jesse identified on page 208 illustrates an important point. He noticed that his rules required something that was in fact impossible: unfailing 100 per cent performance and never encountering criticism of any kind. This is characteristic of unhelpful rules linked to low self-esteem. They mean that your sense of your own worth is dependent on things which are impossible (e.g. being perfect, always being in full control of what happens to you), or outside your control (e.g. being accepted and liked by everyone). People hang self-esteem on a whole range of pegs:

The list is endless. The problem is that none of these things can be guaranteed. We all get old; we all get sick from time to time; we may be damaged or disabled; we may lose our employment; our children leave home (or if they don’t, that becomes a cause of concern); there are times in our lives when we have no one special to love us or when our futures are insecure; and so on. All these things are fragile, and could be taken away. This means that, if we depend on them in order to feel good about ourselves, our self-esteem is also fragile. To be happy with yourself simply for existing, just as you are, regardless of your circumstances, puts you in a far stronger position.

You are looking for general rules that reflect what you expect of yourself, your standards for who you should be and how you should behave, your sense of what is acceptable and what is not allowed, and your idea of what is necessary in order to succeed in life and achieve satisfying relationships. In essence, you are defining what you have to do or be in order to feel good about yourself, and what your self-esteem depends on. If you have low self-esteem, the chances are that these standards are demanding and unrealistic (more, for example, than you would expect of any other person) and that, when you explore their impact, you will discover that they actually prevent you from having a secure sense of personal worth.

Rules for Living can usually be expressed in one of three ways: assumptions, drivers and value judgments.

These are your ideas about the connections between self-esteem and other things in life (for example, those listed on page 213). These usually take the form of ‘If . . . , then . . .’ statements (they can also be phrased as ‘Unless . . . , then . . .’). If you look back at the list of Rules for Living on page 57 in Chapter 2, you will find a number of examples of assumptions, for example:

Sometimes the ‘If . . . /Unless . . ., then . . .’ is not immediately obvious, but you will see it if you look carefully. For example, Arran’s ‘Survival depends on hitting back’ could be understood as an assumption: ‘Unless I hit back, then I will be destroyed.’

Assumptions like these are rather like negative predictions writ large. They describe what you think will happen if you act (or fail to act) in a certain way. This immediately provides a clue to one important way of changing them. They can be tested by setting up the ‘if . . .’ and seeing if the ‘then . . .’ really happens. As you learned in relation to anxious predictions, the threat could be more apparent than real.

These are the ‘shoulds’, ‘musts’ and ‘oughts’ that compel us to act in particular ways, or be particular kinds of people, in order to feel good about ourselves. There are some examples of ‘drivers’ in the list on page 57:

Drivers usually link up with a hidden ‘or else’. If you can find the ‘or else’, you will be able to test out how accurate and helpful they are. For Briony, the ‘or else’ was ‘they will see what a bad person I am and reject me’. For Geoff, it was ‘I will go over the top and spoil things’. For Jim, it was ‘I am weak’.

You can see from these examples that the ‘or else’ may be very close to the Bottom Line. In fact, the ‘or else’ may be a simple statement of the Bottom Line: ‘or else it means that I am inadequate/unlovable/incompetent/ugly’ or whatever. In this case, the driver is a very clear statement of the standards on which a person bases his or her self-esteem.

These are statements about how it would be if you acted (or did not act) in a particular way, or if you were (or were not) a particular kind of person. In a sense, these are rather similar to assumptions, but their terms are more vague, and may need to be unpacked to be fully understood. Examples would be: ‘It’s terrible to make mistakes’, ‘Being rejected is unbearable’, ‘It’s crucial to be on top of things’. If you find rules that take this form, you need to ask yourself some careful questions in order to be clear about the demands they are placing on you. Try to find out what exactly you mean by these vague words (‘terrible’, ‘unbearable’, ‘crucial’). For example:

As we have said, you may never have expressed your personal rules in so many words at all. This can make them less easy to spot than anxious and self-critical thoughts which you can often observe running through your mind.

It also makes ferreting out your rules a fascinating process. You become a detective searching for clues that will give you the key to the story, an explorer hunting the map that will give you an overview of paths through the jungle. You may even feel quite surprised to discover what your rules are (‘Oh, that’s nonsense, I don’t believe that’). If this if your first reaction, stop for a moment and consider. It may be hard to believe your rule when you are sitting calmly with it written down in front of you. But what about when you are in a situation relevant to it? For example, if your rule is to do with pleasing people, what about situations where you feel you have not done so? Or if your rule is to do with success, what about situations where you feel you have failed? And what about times when you are upset and feeling bad about yourself? Even if the rule you have identified does not seem fully convincing to you in the cold light of day, do you in fact act as if it were true? If so, then unlikely as it may seem, you’ve hit pay dirt.

When it comes to identifying your rules, you already have a wealth of relevant information from the work you have done on anxious predictions, self-critical thoughts and enhancing self-esteem. You may already have observed that certain situations reliably spark off uncomfortable emotions and cause you problems. These are likely to be the situations relevant to your own personal set of rules.

The key situations for Jesse, for example, were times when he might be unable to perform to standard and feared he would attract criticism. Your observation of repeating patterns in your reactions may have already given you a pretty clear idea of what your rules are. If not, do not worry. If you have never put your rules into words, then it may take a while to find the right formula. Be creative and open-minded. Approach the task from different angles, using the ideas below to develop hunches about what they might be. Try different rules on for size, experiment with different wordings, and use all the clues at your disposal, until you find a general statement which seems to have been influencing you more or less consistently for some time, and which has affected your life in a range of different situations.

You can use a number of sources of information to identify your rules. Some of these are summarized below and described in more detail on pages 220–30. You will probably find the process most rewarding and thought-provoking if you explore a range of different sources.

It is worth realizing that you may have a number of rules. Make a note of any you discover. But it is probably best to work systematically on one at a time. Otherwise, you may lose track of what you are doing. Choose a rule to work on that relates to an area of your life that you particularly want to change (e.g. relationships with other people). When you have completed the process of formulating an alternative rule and testing it out, you can use what you have learned to tackle other unhelpful rules that you also wish to change.

Figure 26 Identifying unhelpful Rules for Living: Sources of information

• Direct statements

• Themes

• Your judgments of yourself and other people

• Memories, family sayings

• Follow the opposite (things you feel really good about)

• Downward arrow

Look through the record you have kept of your anxious predictions and self-critical thoughts. See if you can identify any rules masquerading as specific thoughts. On reflection, do any of your predictions in particular situations reflect broader issues? Are any of your self-critical thoughts specific examples of a more general rule?

Jesse, when rushing to complete his assignment, has the thought: ‘This has got to be 100 per cent great.’ On reflection, he could see that this statement could also apply in many other situations – it was a general rule.

Even if no Rules for Living are directly stated in your record sheets, can you pick out continuing preoccupations and concerns? Themes that run through the work you have done? What kind of situations reliably make you doubt yourself (for example, noticing you have not done something well, or having to encounter people you are unfamiliar with)? What aspects of yourself are you most hard on? What behavior in other people undermines your confidence? Repeating themes can give you some idea of what you require of yourself, other people and the world in order to maintain your sense of self-esteem.

Sarah noticed from recording her anxious and self-critical thoughts that she was hard on herself whenever someone showed any sign whatsoever of disliking a painting she had done. On reflection, this helped her to identify a new rule: ‘If someone disapproves of me, there must be something wrong with me.’ Jesse, in contrast, noticed when he recorded his activities on the Daily Activity Diary that he tended to dismiss any activity which did not receive a Mastery rating of 8 or above. He realized after consideration that this black-and-white thinking reflected one of his perfectionist rules: ‘If it’s not 100 per cent, it’s pointless.’

Look at your self-critical thoughts. Under what circumstances do you begin to put yourself down? What do you criticize in yourself? What does that tell you about what you expect of yourself? What might happen if you relax your standards? How could things go wrong? If you do not keep a tight rein on yourself and obey the rule, where will you end up? What sort of person might you become (e.g. stupid, lazy, selfish)? What are you never allowed to do or be, no matter what?

Consider, too, what you criticize in other people. What standards do you expect them to meet? These may reflect the demands you place on yourself. Jesse, for example, noticed that he was always impatient with people who took a relaxed attitude to their work, allowed themselves lunch breaks and went home at a reasonable hour. ‘Useless,’ he would say to himself. ‘Might as well not bother to come in at all.’ This harsh judgment of other people was another clue to the high standards he set himself.

As has been said, rules have their roots in experience. Sometimes people can trace them back to particular early memories, or to sayings that were current in the household where they grew up. Identifying these may help you to understand the policies you have adopted. Your rules may now be outdated and unhelpful, but there was a time when they made perfect sense.

When I asked for something as a child, I was often told in disapproving tones: ‘I want doesn’t get.’ The message I took away from this was that if I wanted something, I would not be allowed to have it, or it would be taken away from me. In order to avoid disappointment, it was probably better not to want anything, and it was certainly not a good policy to be open about what you wanted.

I have realized only quite recently, since having children of my own, that ‘I want doesn’t get’ was actually intended to convey an entirely different message: ‘If you want something, say please’ or, more broadly, ‘Be polite’. Despite this new understanding, I still often find it difficult to ask for what I want directly, and feel apprehensive about committing myself to want anything wholeheartedly.

This example shows how statements can have one meaning for the people who make them, and another for the people on the receiving end. What was intended as a lesson in manners was understood in a less benign way. As a child, not knowing any different, I took what I was told absolutely literally. The policy I developed as a consequence has stuck with me through thick and thin. Even insight into the difficulty and its origins has not eliminated it. As you will discover, identifying your rules is only the first step to changing them.

Think back to when you were young, as a child and in your teens, and consider the messages you received about how to behave and the sort of person you should be. When you were growing up:

To help you search out particular memories, look at your thought records again, and pick out feelings and thoughts that seem typical to you (themes). Ask yourself:

Your knowledge of situations which you find difficult is one valuable source of information about your Rules for Living. You may also find clues by looking carefully at the times when you feel particularly good. These may be the times when you have obeyed the rules, done as you should and got the reactions from others that you need in order to feel good about yourself. You did reach those high standards, you did look absolutely stunning in every detail, everyone did like you, it was tough but you did keep things under control. So, ask yourself:

This is a way of using your awareness of how you think and feel in specific problem situations to get at general rules. It was first described in David Burns’s book, Feeling Good, a self-help cognitive therapy manual for depression (pages 263–70). You will find an example (Jesse’s downward arrow) on page 229. These are the steps involved:

Think of a kind of problem situation which reliably upsets you and makes you feel bad about yourself (for example, being criticized, failing to meet a deadline, avoiding an opportunity). These are the situations where your Bottom Line has been activated because you are in danger of breaking your rules, or have actually broken them. Now think of a recent example which is still fresh in your memory.

Remind yourself what happened. On a blank sheet of paper, write down the emotions you experienced in the situation and the thoughts or images that ran through your mind. Identify the thought or image which seems to you to be most important, and which most fully accounts for the emotions you experienced.

Instead of searching immediately for alternatives to your thoughts, ask yourself: ‘Supposing that were true, what would it mean to me?’ When you find your answer to this question, rather than trying to work out alternatives to it, ask the question again: ‘And supposing that were true, what would it mean to me?’ And again. Continue on, step by step, until you discover the general underlying rule that makes sense of your thoughts and feelings in the specific problem situation you started from.

‘What would that mean to you?’ is only one possible question you can use to pursue the downward arrow. You will find others that may be helpful in teasing out the rule behind the problem summarized on page 228.

Remember, it is possible that you have a number of unhelpful rules for living – people often do. You may find it interesting to pursue downward arrows from a number of different starting points. This is crucial if you have difficulty identifying your rule when you first do it. It is also a way of verifying that you are on the right track, and of discovering other rules within your system. Experiment with asking different questions, too. The answers may be illuminating.

Figure 27 Downward arrow questions

• Supposing that were true, what would it mean to you?

• Supposing that were true, what would happen then?

• What’s the worst that might happen? And what would happen then? And then?

• What would be so bad about that? (n.b. ‘I would feel bad’ is not a helpful answer to this question. You probably would feel bad, but that on its own will not tell you anything useful or interesting about your rules. So if your immediate answer is something about your own feelings, ask yourself why you would feel bad.)

• How would that be a problem for you?

• What are the implications of that?

• What does that tell you about how you should behave?

• What does that tell you about what you expect from yourself, or from other people?

• What does that tell you about your standards for yourself?

• What does that tell you about the sort of person you should be in order to feel good about yourself?

• What does that tell you about what you must do or be, in order to gain the acceptance, approval, liking or love of other people?

• What does that tell you about what you must do or be in order to succeed in life?

If, when you do the downward arrow, you have a sense of going round in circles after a certain point, the chances are that you have reached your rule, but that it is not in a form you can easily recognize. Stop questioning, stand back and reflect on your sequence. What Rule for Living do the final levels suggest to you? When you have an idea, a draft rule, try it on for size. Can you think of other situations where this might apply? Does it make sense of how you operate elsewhere?

Try another similar starting point. Does it end up in the same place? Take a few days to observe yourself, especially your anxious predictions and self-critical thoughts. Does your draft rule make sense of your everyday reactions? If so, you are in a position to start looking for a more helpful alternative. If not, what rule might better account for what you observe? Don’t be discouraged; have another go.

You may find at first that you have a good general sense of what your rule might be, but that the way you have expressed it doesn’t feel quite right. Because rules are often unformulated, it may be awkward at first to get the right wording. Play around with the wording until you find a version that ‘clicks’ with you. Try out the different possible forms a rule can take: assumptions, drivers and value judgments. When you get the right wording, you will experience a sense of recognition – ‘Aha! So that’s what it is.’

Figure 28 The downward arrow: Jesse

Situation: Was asked a question I could not answer in a meeting

Emotions: Anxious, self-conscious, embarrassed

Thought: I should know the answer to that

What does it mean to me that I don’t?

That I’m not doing my job properly

And if that was true, what would it mean to you?

That sooner or later people will notice that I’m not up to it

And supposing they did, what would follow from that?

I would lose credibility. I might be demoted

And what are the implications of all that for your performance?

I really can’t afford not to have the answers to everything.

I’ve got to come up with the goods, all the time, no matter what

So what’s the rule?

Unless I always get it right, I will never get anywhere in life

Rules are not like anxious predictions or self-critical thoughts. They do not pop into your head under specific circumstances at specific moments. They may influence how you think, feel and act across a whole range of different situations, and across time. As we said, you may well have learned them when you were very young.

Once you have identified an unhelpful rule, it is worth considering the impact it has had on your life. When you come to change your rule, you will not only need to formulate an alternative, more realistic and helpful Rule for Living, but also to modify its continued influence on daily living. Recognizing its impact will help you to achieve this. You will already have much of the information you need, from the work you have done on anxious predictions, self-critical thoughts and enhancing self-esteem.

Start by looking at your life now. What aspects of it does your rule affect? For example, relationships? Work? Study? How you spend your leisure time? How well you look after yourself? How you react when things do not go well? How you respond to opportunities and challenges? How good you are at expressing your feelings and making sure your needs are met? How do you know your rule is in operation? What are the clues? Particular emotions, or sensations in your body, or trains of thought? Things you do (or fail to do)? Reactions you get from other people?

Now look back over time. Can you see a similar pattern extending into your past? From a historical perspective, what effect has the rule had on you? What unnecessary self-protective policies and precautions has it led to? What have you missed out on, or failed to take advantage of, or lost, or jeopardized because of the rule? What restrictions has it placed on you? How has it undermined your freedom to appreciate yourself, and to relax with others? How has it affected your capacity for pleasure? Look back at the work you have already done in previous chapters. How much of what you have observed can be accounted for by this rule?

You should now have a good sense of what your rule (or rules) might be. Consolidate by summarizing in writing what you have discovered:

You may find it helpful to increase your sense of how the rule operates by watching it in action for a few days. Collect examples (probably very similar to what you have already been recording) and fine-tune your understanding of how it influences you and how you can tell that it is in operation. Once you have identified it, you may discover it popping up all over the place.

Your Rules for Living may have been in place for some considerable time. They will not change overnight. However, you are not at square one. The skills you have already mastered in dealing with anxious predictions and self-critical thoughts, in focusing on your good points and treating yourself to the good life, are all part of changing the rules. Now that you know what they are, you will move on to question the rules in their own right. You will find some helpful questions summarized on page 233 and discussed in more detail below.

Your aim is to find new rules which will encourage you to adopt more realistic standards for yourself and help you to get what you want out of life. As we said earlier, you may have discovered more than one unhelpful rule that keeps your self-esteem low (for example, you need approval and you are also something of a perfectionist). If so, start with the one you would most like to change, and then use what you learn to undermine the others. You will gain more from working systematically on one rule at a time than from jumping around from one to another, doing a little bit here and a little bit there. You may find it helpful to summarize your line of argument and how you plan to test-drive your new rule in a flashcard as discussed on page 243.

Figure 29 Changing the rules: Helpful questions

• Where did the rule come from?

• In what ways is the rule unreasonable?

• What are the payoffs of obeying the rule?

• What are the disadvantages?

• What alternative rule would be more realistic and helpful?

• What do you need to do to ‘test-drive’ your new rule? How can you go about putting it into practice on a day-to-day basis?

The purpose here is not to wallow in the past, but rather to put your rules in context, to understand how they started and what has kept them going. This is a step towards detaching yourself from them. Keep these questions in mind:

You may already have a good sense of where your rules come from. Understanding their origins will help you to see that they were your best options, given the knowledge available to you at the time. This insight in itself is unlikely to produce substantial change, but it can be a helpful first step towards updating your rules for living. However, if you cannot think where your rules have come from, do not despair. This information is not essential to changing them. It just means that the questions which follow are likely to be more helpful to you.

If you know what they are, summarize for yourself the experiences in your life that led to the rule. Remind yourself when you first noticed the cues that tell you it is in operation. Was the rule part of your family culture, or part of the wider culture in which you grew up? Did you adopt it as a means of dealing with difficult and distressing circumstances? Was it a way of ensuring the closeness and caring you needed as a child? Or of managing unkind or unpredictable adults? Or coping with the demands of school? Of avoiding teasing and ridicule?

You may also want to take account of later experiences that have contributed to keeping the rule in place. For example, have you found yourself trapped in abusive relationships? Have other people taken over the critical role your parents took towards you? Have you repeatedly found yourself in environments that reinforce the policies you have adopted? Jesse, for example, had particular problems in one job where he had a bad-tempered and critical boss. Under this pressure, he redoubled his efforts to get it right.

Granted that the rule did make sense at one point, you nevertheless need to ask yourself how relevant it is to you is it now, as an adult. If you come from a broadly Christian country, there was probably a time in your life when you believed in Santa Claus. You had every reason to do so. People you trusted told you he existed, and you saw the evidence with your own eyes on Christmas morning. It made perfect sense to adopt a policy of trying to be especially good in the days before Christmas and putting out a stocking (or pillowcase) for your presents. When I was a child, we also left a glass of brandy and a mince pie out for the old man, and some carrots for the reindeer. In the morning, nothing was left but crumbs.

But things move on, and you now have a broader experience of life and a different understanding of what happened on Christmas Eve. It is unlikely that, as an adult, you are still convinced that Santa Claus exists and behave accordingly. It would be odd if you still put out your stocking – unless, of course, you have good reason to suppose that someone else in your household will fill it, or you are playing Santa Claus for a new generation of children.

If you come from a cultural background which does not recognize Santa Claus, think of other myths or legends which you believed in as a child but which you now understand differently. Maybe the same is true of your personal rules. Are they still necessary or beneficial? Or might you in fact be better off with an updated perspective?

This question is a little like questioning negative thoughts by assessing the evidence for and against them. Unhelpful rules for living are extreme in their demands. In this sense, they depart from the facts and refuse to recognize the richness and variety of experience. Call on your adult knowledge to consider in what ways your rule fails to take account of how the world works. How does it go beyond what is realistically possible for an ordinary, imperfect human being, or what you would expect from another person you respected and cared about? In what ways are its demands over the top, exaggerated or even impossible to meet?

Remember, this was a contract you made with yourself as a child. Would you now allow a child to run your life for you? Why not? What can you see as an adult that you could not grasp when you were very young? Given their limited experience of life, how good are children at seeing that one situation is different from another, that what works with one person does not work with another, that everything passes, that what is true at one time and in one place may not be true at another?

However unhelpful they are in the long run, Rules for Living have genuine payoffs. These help to keep them in place. Jesse, for example, knew that his high standards did genuinely motivate him to produce excellent work, for which he was respected and praised and which had helped to advance his career. This was not something he wished to lose.

It is important to be clear about the payoffs for your own rules, because alternatives you formulate will need to give you the advantages of the old rule, without its disadvantages. Otherwise, you may be understandably reluctant to let go of the old system – after all, better the devil you know than the devil you don’t.

Make a list of the payoffs and advantages of your rule. What benefits do you gain from it? In what ways is it helpful to you? And consider too what you might risk if you were to let go of it. What does it protect you from?

People often have an uneasy feeling that if they were to abandon their rules, catastrophe would follow. Jesse suspected that if he were not a perfectionist, he might never again do a decent piece of work. It felt to him as though perfectionism was the only thing that guaranteed acceptance from other people. Ideas like these can be tested out through experiments at a later stage. For the moment, the important thing is to identify payoffs and fears that keep the old rule in place.

When you have listed all the payoffs of your rule, take a careful look at them. Some of them may be more apparent than real. For example, the rule that you must always put others first may encourage you to be genuinely helpful, and dispose others to feel kindly towards you. But there is a downside: your own needs are not met, and the result can be increasing resentment and fatigue, so that in the end you are no longer in a fit state to attend to others.

Jesse realized, on reflection, that his excellent work did not in fact always guarantee acceptance. He was sometimes so driven and tense that people found him unapproachable and thought him arrogant.

Do not take the payoffs you have identified for granted. Look at them closely, and assess how far they are genuine in practice. Do the same for your concerns about dropping your rule. How do you know these things would actually happen? How could you find out?

You have explored the payoffs; now for the downside. Examine the ways in which the rule restricts your opportunities, robs you of pleasure, contaminates and sours your relationships with other people, undermines your sense of achievement or stands in the way of getting what you want out of life. Use the information you have already collected when you were assessing its impact on your life and observing it in action from day to day.

It may help to clarify the impact of the rule on your chances of achieving the kind of life you want for yourself. Make a list of some of your main goals in life. Examples might be: to have a satisfying career; to take pleasure in what I do; to be relaxed and confident with people; to make the most of every experience. Then ask yourself: does this rule help me to achieve these goals? Is it the best strategy for getting what I want out of life? Or does it in fact stand in my way?

It can be helpful to summarize the payoffs and disadvantages you have identified by taking a blank sheet of paper and drawing a vertical line down the middle. In the left-hand column, write down the payoffs attached to your rule and the apparent risks of letting it go. In the right-hand column, list its disadvantages. Weigh up the two lists and, at the bottom, write your conclusions about just how helpful your rule is to you. If you decide that, on balance, your rule is helpful and takes you where you want to go, then you need take this exercise no further. If, on the other hand, you conclude that the rule is unhelpful, and stands in the way of getting what you want out of life, the next step is to formulate an alternative that will give you the advantages of the old without its disadvantages.

New rules can transform day-to-day experiences. They allow you to deal comfortably and confidently with situations which, under the old system, would have been code violations, triggering anxiety or self-criticism. What would have been disasters become passing inconveniences. What have seemed matters of life and death become exciting challenges and opportunities. New rules open the door to achieving what you want out of life.

To help you to free up your thinking, consider whether you would advise another person to adopt your old rule as a policy. If, for example, an alien from outer space came to you for advice on how to ensure a happy and fulfilled life in your part of the planet, what would you say? Or again, would you want to pass on your rule to your children, if you had any? If not, what would you prefer their rule to be?

Your task is to find a new rule which as far as possible allows you to enjoy the payoffs of the old, but eliminates its disadvantages. The new rule will probably be more flexible and realistic than the old one, more able to take account of variations in circumstances, and to operate in terms of ‘some of the people, some of the time’. It will inhabit the middle ground rather than the extremes. So it will be phrased in terms of ‘I want . . .’, ‘I enjoy . . .’, ‘I prefer . . .’, ‘It’s OK to . . .’, rather than ‘I must . . .’, ‘I should . . .’, ‘I ought to . . .’, or ‘It would be terrible if . . .’ You may find that the new rule starts with the same ‘if . . .’, but ends with a different ‘then . . .’ For example, Jesse replaced ‘If someone criticizes me, it means I have failed’ with ‘If someone criticizes me, I may or may not deserve it. If I have done something worthy of criticism, that’s not failure – it’s all part of being human, and there’s nothing wrong with that.’

This example illustrates something typical of new rules: they are often more lengthy and elaborate than old ones. This reflects the fact that they are based on an adult’s ability to understand how the world works at a deeper level and to take account of variations in circumstances. Sometimes it is nice, however, to capture their essence in a slogan, the sort of snappy statement you might find on a badge or T-shirt. Some time after he had formulated his new rule, Jesse watched a film in which a young boy was struggling to please his father on the mistaken grounds that only something exceptional would win his approval. Jesse to decided to adopt the father’s loving response as a slogan for himself: ‘You don’t have to be great, to be great.’

You may find it difficult at first to find an alternative you feel comfortable with. Write down your best shot, and then try putting it into operation for a week or two to find out how well it works for you and if there are any ways of changing it for the better. It may also be worth your while to talk to and observe other people. What do you think their rules might be? Your observations will give you an opportunity to discover the variety of positions people adopt, and to clarify what stance might work best for you.

Your old rule may have been in operation for some considerable time. In contrast, the new one is only fresh from the lathe, and it may take a while for it to become a comfortable fit. You need to consider what to do to consolidate your new policy, check out how well it works for you, and plan how to put it into practice on an everyday basis. This takes us back to all the work you have already done, and to the central idea of finding things out for yourself by setting up experiments and examining their outcome. The most important thing you can do to strengthen your new rule (and indeed to discover if you need to make further changes to it) is to act as if it was true and observe the outcome. The next section will provide some ideas on how to go about this.

This is a good time to complete your written summary, using the headings on page 232 if you wish. You will find an example (Jesse’s written summary) on pages 247–8. You have already summarized what you discovered when you were identifying your unhelpful rule; now you can summarize what you learned when you worked on changing it.

Like your list of positive qualities and good points, a written summary on its own is not enough. The line of argument you have pursued, and the new rule you have formulated, need to be part of your everyday awareness, so that they have the best possible chance of influencing your feelings and thoughts and what you do in problem situations. So when you have completed your summary, put it somewhere easily accessible and, over the next few weeks, read it carefully every day – perhaps more than once a day, to begin with. A good time is just after you get up. This puts you in the right frame of mind for the day. Another good time is just before you go to bed, when you can think over your day and consider how the work you have done is changing things for you.

The objective is to make your new rule part of your mental furniture so that eventually, acting in accordance with it becomes second nature. Continue to read your summary regularly until you find you have reached this point.

Another helpful way to encourage the changes you are trying to make is to write your new rule on a stiff card (an index card, for example) small enough to be easily carried in a wallet or purse. You can use the card as a reminder of the new strategies you aim to adopt, for example taking it out and reading it carefully when you have a quiet moment in the day, and before you enter situations you know are likely to be problematic for you.

Even when you have a well-formulated alternative and you are beginning to put it into practice, your old rule may still rear its ugly head in the usual situations for some while. After all, it has been around for a long time and may not just slink quietly away as soon as you expose it to the light of day. If you are prepared for this, you will be able to tackle the old rule calmly when you see it in operation, instead of getting discouraged and wondering if you will ever be rid of it. Here is where the work you have done on anxious predictions and self-critical thoughts will pay off. Remember that these are the sign that the old rule is in danger of being broken. Continue to use the skills you have learned to question your thoughts, find alternatives to them, and experiment with acting in different ways. Over time, you will find you have less and less need to do so.

As well as tackling the old rule when it comes up, you need to develop a clear plan of action to help you experiment with acting in accordance with the new rule and observing the outcome. Do the ‘if . . .’ or ‘unless . . .’ and see if the ‘then . . .’ follows. If you look back over earlier chapters, you may well find that in fact you have already been doing so when you checked out anxious thoughts, combated self-criticism by being kinder and more tolerant towards yourself, focused on your good points, gave yourself credit for your achievements, and treated yourself to the good things in life. Examine what you have already done, and identify things which are a part of changing your rules. You can put them in your action plan.

In addition, ask yourself what else you could do to ensure that your new rule is indeed a useful policy, and to explore the impact of adopting it on your everyday life. This means expanding your boundaries, discovering that it is still possible to feel good about yourself even if you are less than perfect, even if some people dislike and disapprove of you, even if you sometimes put yourself first, or even if you are sometimes gloriously out of control.

Make sure that you include specific changes in how you go about things, not just general strategies. Not just ‘to be more assertive’, for example, but ‘ask for help when I need it’, ‘say no when I disagree with someone’, ‘refuse requests when to carry them out would be very costly for me’, ‘be open about my thoughts and feelings with people I know well’. Then consider how to plan these changes into your life. You could, for instance, use the Daily Activity Diary to plan experiments at specific times, with specific people, in specific situations.

You will also need to be sure that you know how to go about assessing the results of your experiments. This is rather like what you learned to do when you were checking out anxious predictions. What exactly do you need to be on the lookout for? What would be the signs that your new policy was paying off – or not? What would you observe in yourself (your feelings, your body state, changes in your behavior) if the new rule was working (or not)? What would you see in others’ reactions to you? Just as you specified your predictions and how you would know if they were true at the thoughts level, so you need to be specific when carrying out experiments to consolidate and strengthen new rules for living.

Do not be surprised if acting in accordance with your new rule feels uncomfortable at first. You may well find that you feel quite apprehensive before you carry out experiments. If so, work out what you are predicting and use your experiment to check it out (remember to drop unnecessary precautions, otherwise you will not get the information you need). Equally, you may find you feel guilty or worried after you have carried out an experiment, even if it has gone well. This happens, for example, with people who are experimenting with being less self-sacrificing or with dropping their standards from ‘110 per cent’ to ‘good enough’. Or again, you may get angry with yourself and become self-critical if you plan to carry out an experiment and then chicken out. Again, if you experience uncomfortable feelings like these, look for the thoughts behind them and answer them, using the skills you have already learned.

It could take as much as six to eight months for your new rule to take over completely. As long as the new rule is useful to you and you can see it taking you in useful and interesting directions, don’t give up. You may find it helpful to review your progress regularly and to set yourself targets. What have you achieved in the last week, or month? What do you want to aim at in the next week, or month?

Keeping written records of your experiments and their outcome, and of unhelpful thoughts that you have tackled along the way, will help you to see how things are progressing. You can look back over what you have done and use it as a source of encouragement. It may also be helpful to work with a friend – ideally, someone who does not share your particular rule and whose particular rule you do not share. Two heads are better than one, but not when you both have identical perspectives.

Figure 30 Changing the rules: Written summary – Jesse

• My old rule is:

Unless I get it right, I will never get anywhere in life.

• This rule has had the following impact on my life:

I have always felt inadequate, not good enough. This has made me work tremendously hard, to the extent that I have been constantly under pressure, tense and stressed. This has affected my relationships. I have not had enough time for people, and I have lost out because of it. At times, it has made me quite ill. And I have sometimes run away from opportunities because I didn’t think I would measure up.

• I know the rule is in operation because:

I get anxious about failing and put myself under more and more pressure. I go over the top in how I go about things – try to dot every ‘i’ and cross every ‘t’. I feel sick with anxiety. And if I think I’ve broken the rule, I become very self-critical, get depressed, and give up altogether.

• It is understandable that I have this rule because:

When I was young, my father’s disappointment with how his life has turned out made him very keen that we should all make the most of ourselves. Instead of encouraging and praising us, he gave us all the message that we were not up to it if we did could not perform the way he wanted us to. That message sank in, and I have tried to compensate by being a perfectionist.

• However, the rule is unreasonable because:

It simply is not humanly possible to get it right all the time. Making mistakes and getting things wrong are all part of learning and growth.

• The payoffs of obeying the rule are:

Sometimes I do really good work, and get praise for it. This is partly why I have done so well in my career. People respect me. When I do get it right, I feel great.

• But the disadvantages are:

I am constantly tense. Sometimes my work is not as good as it could be, because I get in such a state about it. I can’t learn from my mistakes, because they upset me so much, nor can I learn from constructive criticism. When things do not work out, I feel dreadful and it takes me ages to get over it. I avoid anything that I might not be able to get right, and miss all kinds of opportunities because of that. People may respect me, but it keeps them at a distance. They see me as a bit inhuman, unapproachable – even arrogant. The pressure I place on myself is bad for my health. Plus all my time and attention goes on my work – I don’t give allow myself to relax or do things to enjoy myself. In short, the rule leads to stress, misery and fear on all fronts.

• A more realistic and helpful rule would be:

I enjoy doing well – there’s nothing wrong with that. But I’m only human and I will get it wrong sometimes. Getting it wrong is the route to growth.

• In order to test-drive the new rule, I need to:

• Keep reading this summary

• Put my new rule on a flashcard and read it several times a day

• Cut my working hours and plan pleasures and social contact

• Take time for myself

• Revise my standards and give myself credit for less than perfect performance

• Experiment with getting it wrong and observe the outcome. For example, practise saying ‘I don’t know’ when people ask me questions

• Plan my day in advance, and always plan less than I think I can do

• Focus on what I achieve, not on what I failed to do. Tomorrow is another day

• Remember: criticism can be useful – it doesn’t mean I am a complete failure

• Watch out for signs of stress – they mean I am going back to my old ways

• Deal with the old pattern, when it comes up, using what I have learned to tackle anxious predictions and self-criticism

CHAPTER SUMMARY