Interactions Among the Branches of Government (Unit 2) |

2 |

Unit 1 established the foundations of American democracy, the founding documents written by the founding fathers. Unit 2 establishes how the three branches of government interact with each other, how they use the powers given by the Constitution, how checks and balances prevent any one branch of government from becoming too strong, and how, ultimately, they must cooperate and compromise in order to govern effectively. This unit will cover the characteristics of each branch and the powers given to the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government.

The first of four institutions to be explored in this unit, Congress can be viewed as the citizens’ direct link to the branch of government that is responsible for public policy. It has a number of functions including, but not limited to, representing the interests of constituents, lawmaking through consensus building, oversight of other governmental agencies, policy clarification, and ratification of public policies.

The presidency has evolved into the focal point of politics and government in America. This institution is the political plum for those seeking elected office. The president plays a predominant role in government, having formal and informal relationships with the legislative and judicial branches and the bureaucracy. Other roles that involve the president more than any other individual or institution in politics and government will be evaluated. Potential conflicts and the reasons why the institution has been criticized for an arrogance of power are important areas to explore.

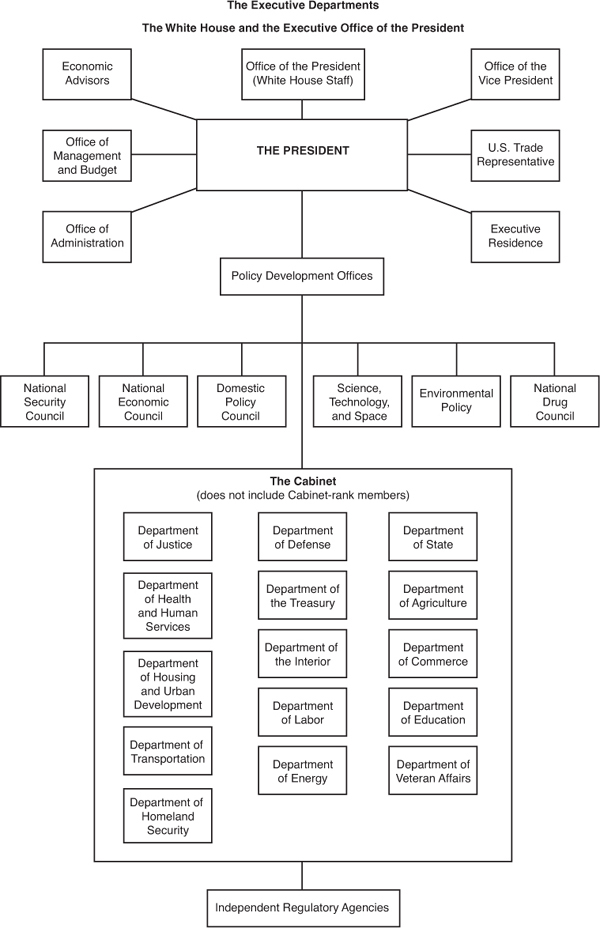

The constitutional basis of power as well as how the president has used executive agencies such as the cabinet, the executive office, and the White House staff demonstrates the growth of the executive branch. Additionally, the shared legislative relationship the president has with Congress points to the complex issue of whether the institution has developed into an imperial presidency, a presidency that dominates the political agenda.

This unit also explores the third branch of government, the judicial branch, its characteristics, functions, and how it uses judicial review to interpret the Constitution and limit the power of the Congress and president.

The unit explores the evolution of the judiciary, how it makes decisions regarding constitutional issues, and the ideological battles between the liberal and conservative members of the court. The terms “judicial activism” and “judicial restraint” are also explained in the context of the past and of today’s court.

The federal bureaucracy, sometimes referred to as the fourth branch of government, plays an important linkage role in Washington. The bureaucracy is primarily responsible for implementing policies of the branches of government. Some bureaucracies also make policy as a result of regulations they issue.

This unit also focuses on four types of governmental bureaucratic agencies—the cabinet, regulatory agencies, government corporations, and independent executive agencies. We will also look at the various theories regarding how bureaucracies function. By tracing the history of civil service, you will be able to understand the role patronage has played in the development of government bureaucracies. You will also see how the permanent government agencies became policy implementers and how they must function in relation to the executive branch, legislative branch, and judicial branch.

Constitutionalism provides for the separation and interaction of the branches of government. Competing Policy-Making Interests of the branches of government are essential to the development and implementation of public policy.

Bully pulpit

Cloture

Committee of the whole

Congressional oversight

Delegate

Discharge petition

Discretionary spending

Divided government

Entitlement

Enumerated power

Executive order

Filibuster

Gerrymandering

Holds

Implied power

Judicial activism

Judicial restraint

Lame duck

Logrolling

Mandatory spending

Necessary and proper clause

One person, one vote

Pocket veto

Policy agenda

Politico

Pork-barrel legislation

Precedent

Rider Amendment

Rules committee

Signing statement

Stare decisis

Trustee

Unanimous consent

Veto

Whips

White House staff

CONSTITUTIONAL REVIEW OF CONGRESS

■ Basis of constitutional authority is found in Article I.

■ A House member must be at least 25 years old, an American citizen for seven years, and an inhabitant of the state the representative represents. Representatives serve two-year terms.

■ A Senate member must be 30 years old, an American citizen for nine years, and a resident of the state the senator represents. Senators serve six-year terms.

■ Common powers delegated to Congress, listed in Article I Section 8 include the power to tax, coin money, declare war, and regulate foreign and interstate commerce.

■ Implied congressional power comes from the “necessary and proper” clause, which has been referred to as the “elastic clause.”

■ The House of Representatives has the power to begin all revenue bills, to select a president if there is no Electoral College majority, and to initiate impeachment proceedings.

■ Senate has the power to approve presidential appointments and treaties and to try impeachment proceedings.

■ Congress may overrule a presidential veto by a two-thirds vote of each house.

Apportionment, Reapportionment, and Gerrymandering Reflect Partisanship

According to the 2010 United States Census report, the Constitutional basis for conducting the decennial census of population is to reapportion the U.S. House of Representatives. Apportionment is the process of dividing the 435 memberships, or seats, in the U.S. House of Representatives among the 50 states. With the exception of the 1920 Census, an apportionment has been made by the Congress on the basis of each decennial census from 1790 to 2010.

The apportionment population for 2010 consists of the resident population of the 50 states plus overseas federal employees (military and civilian) and their dependents living with them, who were included in their home states. The population of the District of Columbia is excluded from the apportionment population because it does not have any voting seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. The 2010 Census apportionment population was 309,183,463. Even though the next census will not be conducted until 2020, the U.S. Census Bureau updates key demographic statistics every year. In 2018, the bureau estimated the U.S. population to be approximately 327.2 million people.

Guarantees of voting equality through “one person, one vote” representation, the recognition that the size and makeup of congressional districts should be as democratic as possible, has achieved this goal. Gerrymandering, how legislative districts are drawn for political purposes, has undermined the equal representation principle. Each state has its own laws dictating who is responsible for redrawing districts after the U.S. Census is completed every ten years. In most states the legislatures have that responsibility. So, if a state legislature has a Democratic majority, districts can be drawn to favor Democratic incumbents. The same principle applies to a state that has a Republican legislative majority. If there is a dispute over this process, the courts step in. The Supreme Court heard arguments related to a Wisconsin case. Even though there was less than a majority vote for the Republican party in the 2016 election, the Republicans gained a majority in the legislature. The court had to decide whether the reapportionment done by the Wisconsin legislature was done strictly for political reasons. There is also the issue of racial gerrymandering whereby states created majority–minority districts. The Supreme Court has ruled that this practice is unconstitutional. The court did, however, allow the Voting Rights Act of 1965 as a means of allowing race to be used as a factor in drawing districts.

POLICY-MAKING PROCESS OF CONGRESS

Unlike the House of Representatives, the Senate was created by the United States Constitution to represent the states equally. Each state has two senators. As a result of the significant difference in size—the House of Representatives with 435 members and the Senate with 100 members—each chamber operates differently. For example, rules allow much more extensive debate over legislation in the Senate compared to the House. How senators and representatives work with each other also differs because of the length of terms they serve, House members serve two years, senators six years. The longer term and smaller body enables senators to maintain friendships and potentially build relationships across party lines. House members must represent their districts, taking into account individual constituents, organized interests, and the district as a whole. For their individual constituents, representatives set up mobile offices and respond personally to written letters. They contact federal agencies, sponsor appointments to service academies, and provide information and services. For organized groups, they introduce legislation, obtain grants and contracts, give speeches, and attend functions. For the district as a whole, representatives obtain federal projects (sometimes from pork-barrel legislation), look for ways of getting legislation that will increase employment or tax benefits, and support policies that will directly benefit the geographic area of the district.

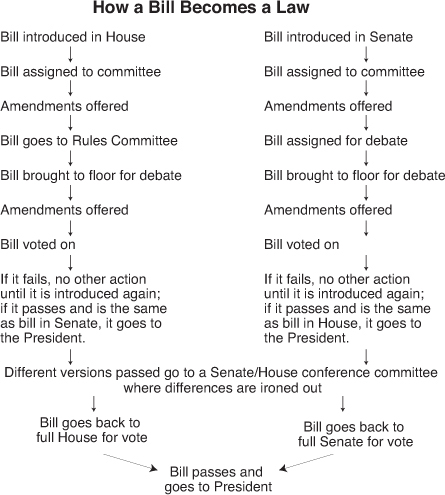

Through such public relations practices as sending out a congressional letter highlighting a reference in the Congressional Record of individuals or the achievements of people in their districts, representatives attempt to get close to the people they represent. By far the most important function of Congress is the legislative responsibility. Before explaining the different approaches to lawmaking, it is important that you understand the way a bill becomes a law.

Obviously, this is a simplified version of the process. And if the president vetoes the bill, the houses of Congress must vote separately to determine whether each has a two-thirds majority to override the veto. In an attempt to increase legislative output, Congress can use several techniques to move legislation along. Logrolling (or “I’ll vote for your legislation, if you vote for mine”) coalitions, consensus building, and pork-barrel deals (legislation that only favors a small number of representatives or senators) often result in agreement to pass bills.

Budget-Making Responsibility of Congress Includes the Debate Over How Much Discretionary and Mandatory Spending Should Be Included

The main legislative responsibility of Congress is passing an annual budget. In response to increased deficit spending, Congress passed the Gramm–Rudman–Hollings Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985. This law was named after its cosponsors, Senators Phil Gramm of Texas, Warren Rudman of New Hampshire, and Ernest Hollings of South Carolina. The law set goals to meet the deficit. If these goals were not met, automatic across-the-board discretionary spending cuts must be ordered by the president. Mandatory programs such as Social Security and interest on the national debt were exempt. In 1989 cuts were made until a budget was approved by Congress. The law also gave direction that the 1993 budget would have to be balanced. Because these were goals, and a balanced-budget requirement would need a constitutional amendment, Congress has used this law as a guide for overall reductions.

Illustrative Example

2011 Debt Limit Agreement and 2013 Fiscal Limit Battle

According to the U.S. Treasury, the national debt has more than doubled over the past decade. Congress needs to vote to raise the debt limit (or debt ceiling) in order for the United States to meet its obligations. In 2011, the Republican majority in the House of Representatives threatened not to raise the debt ceiling unless President Obama made cuts in spending to offset the increase. A crisis was averted in the eleventh hour when a compromise was reached, and the debt ceiling was raised.

Illustrative Example

The Fiscal Cliff and Sequestration

The “fiscal cliff” was a date (January 1, 2013) by which the nation’s economy would be impacted if no action was taken by Congress. For example, that impact would happen in some of the following ways:

■ The so-called Bush tax cuts would expire, and income tax rates would be raised for every taxpayer.

■ Unemployment insurance would run out for millions of people who were out of jobs.

■ There would be mandated cuts in discretionary spending and defense spending defined by law (sequestration).

Congress passed legislation avoiding the fiscal cliff by raising tax rates only on those earning more than $450,000, extending unemployment benefits, and delaying the mandated cuts.

Sequestration was the mandated cuts in discretionary and defense spending passed by Congress for the purpose of reducing spending after President Obama and the House Republicans agreed to raise the debt ceiling and extended the Bush tax cuts in 2011. These cuts took place in 2013, and negotiations began to avert the harmful impact on military and discretionary programs that were cut. Future budgets addressed these cuts, and more funds were provided for the military and for discretionary spending.

Structure of Congress Impacts Public Policy

The bicameral (two-house) structure of the Congress made it a necessity to develop an organization that would result in the ability of each house to conduct its own business, yet be able to accomplish the main function—the passage of legislation.

Each house has a presiding officer. The influence of the Speaker of the House cannot be underestimated. The speaker is selected by the majority party and, even though a House Majority Leader is also part of the unofficial structure of the House, it is the speaker who is really the leader of the majority.

The speaker presides over House meetings and is expected to be impartial in how meetings are run, even though he or she is a member of the majority party. However, with the authority to preside and keep order, the speaker wields a great deal of power: recognizing members who rise to speak, referring bills to committees, answering procedural questions, and declaring the outcome of votes. The speaker also names members to all select (special) committees and conference committees (a committee that meets with the Senate to resolve differences in legislation). The speaker usually votes only to break a tie and has the power to appoint temporary speakers, called speakers pro tempore, to run meetings. The speaker is also third in line after the vice president to succeed the president.

The presiding officer of the Senate, the president of the Senate, is the vice president of the United States. It is a symbolic office, and more often than not the Senate chooses a temporary presiding officer, the president pro tempore to run the meetings. The only specific power of the vice president in the capacity of Senate presiding officer is to break ties. The president pro tempore does not have the same power or influence as the Speaker of the House. Unlike in the House, the real power in the Senate lies with the Senate majority leader. In 2014, the Republicans took control of the Senate; and, thus, the Senate majority leader was a Republican.

The Committee System

Committee chairs, those representatives who chair the standing committees of the House and Senate, wield a great deal of power. In fact, most of the work is done through the committee system. Committee chairs are selected as a result of the seniority system, an unwritten custom that establishes the election of chairs as a result of length of service and of which party holds the majority in the House or Senate. Four types of committees exist in both houses of Congress. Standing committees deal with proposed bills and are permanent, existing from one Congress to the next. Examples of standing committees are Banking, Foreign Affairs, Energy, Governmental Affairs, and Appropriations. Select committees are specially created and conduct special investigations.

The Watergate Committee and Iran–Contra investigators were select Senate committees. Joint committees are made up of members from both houses for the purpose of coordinating investigations or special studies and to expedite business between the houses. Conference committees resolve legislative differences between the House and Senate. Such bills as the Crime Bill of 1994 and the Welfare Reform Act of 1996 had to go through conference committees. Many bills, in fact, must be resolved in this manner. Committee makeup is determined by the percentage of party representation in each house. Representatives attempt to get on influential committees such as the House Ways and Means Committee (which is responsible for appropriations measures), the Senate Judiciary Committee (which makes a recommendation regarding presidential judicial appointments) and the House Rules Committee. Legislation in the House cannot get to the floor without a vote from the Rules Committee. The only exception is if a majority of representatives sign a discharge petition. This action bypasses the Rules Committee, but very rarely succeeds because the majority party usually applies pressure on its members not to sign the petition. The Rules Committee also allocates time for debate and the number of amendments that can be introduced. The House can also convene into a committee of the whole, which is the entire body operating as a single committee to discuss business. This procedure is also not often used.

Most representatives are members of at least one standing committee or two subcommittees (smaller committees that are organized around specific areas). These committees influence legislation by holding hearings and voting on amendments to legislation that have been referred to them. The committees also provide oversight, reviewing the actions of the executive branch. In the House, a key oversight committee is the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. This committee holds hearings that investigate executive branch abuses. Two examples of this were hearings held regarding the attack on the American embassy in Benghazi and on Internal Revenue Service overreach. In the Senate, the Senate Intelligence Committee investigated conduct by the Central Intelligence Agency resulting in torture, and in 2014 released a scathing report condemning such practices. After the 1994 elections, the Republican majority passed new rules that limited the terms of House committee chairs to no more than six years and reduced the number of committees and their staffs.

Along with the committee system, each house has a party system that organizes and influences the members of Congress regarding policy-making decisions. The majority and minority leaders of both houses organize their members by using “whips,” or assistant floor leaders, whose job is to check with party members and inform the majority leader of the status and opinions of the membership regarding issues that are going to be voted on. Whips are responsible for keeping party members in line and having an accurate count of who will be voting for or against a particular bill. The party caucus or party conference is a means for each party to develop a strategy or position on a particular issue. The majority and minority party meet privately and determine which bills to support, what type of amendments would be acceptable, and the official party positions on upcoming business. They also deal with selection of the party leadership and committee membership.

It is one thing to introduce a bill that one day might become law (legislation), and it is another thing to get the votes that can turn that bill into a law. Tactics such as the Senate filibuster, an ongoing speech that needs a vote of 60 senators to cut it off, called cloture, protect minority interests. In 2013, the Senate changed its filibuster rules by passing what was called “the Nuclear Option.” Instead of requiring 60 votes to approve presidential appointments other than Supreme Court nominees, this new rule required a simple majority for approval. The Republican minority was against this procedural change, claiming that it weakened the ability of the minority to debate the qualifications of appointees. When the Republicans gained control of the Senate in 2016 and the Democrats threatened to filibuster President Trump’s appointment of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court, the Republicans also used the Nuclear Option, requiring a simple majority to approve Supreme Court justices. An example of Senate collegiality is the unanimous consent rule. This rule requires the agreement of the entire Senate to move a vote forward. It is usually not challenged because both parties do not want the other party to object. Objections occur when senators feel their voices are not being heard on whatever is being discussed. If a senator wants to slow down the nomination process, then he or she can place a hold on that nominee until any relevant questions get answered.

With treaties, the Senate has a built-in check: senators must approve treaties by a two-thirds majority and can approve presidential appointments by a majority vote. Such significant treaties as the 1962 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and the 2010 Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty are good examples of the president working closely with the Congress.

Constituent Service Is a Component of Representative Accountability Models

If the essence of a senator or representative revolves around the issue of representing his or her constituency, then this member of Congress must define the kind of congressperson he or she will be.

Once elected through the formal process of an open and free election, the definition must begin. Demographic representation mirrors the desires and needs of the various people being represented. Symbolic representation is defined by the style and message of the congressperson and how the people perceive the job he or she is doing. How responsive the legislator is to constituents’ wishes is the last characteristic of representation. How a representative responds to the people who elected him or her is called “constituent service.” The question of whether the representative should reflect the point of view of his or her constituents or vote according to his or her own opinion after hearing information on any issue is a long-standing problem for elected officials. There are three different types of constituent accountability models:

■ Trustee model—voters trust their congressperson to make decisions that the member believes is in the best interests of constituents.

■ Delegate model—voters elect their senator and representatives as their delegates and expect them to vote on the basis of what their constituents believe.

■ Politico model—representatives and senators are the most political in this model, utilizing both the trustee model and delegate model to make decisions.

Gridlock and Divided Government Affect How Congress Operates

As the focal point of public-policy development, Congress has come under public criticism. Polls have reflected deep voter concern regarding the issues of “congressional gridlock,” term limits for representatives and senators, and the influence of lobbyists and PACs on Congresspersons. Many newly elected representatives have committed to reforming congressional structure, procedures, and practices.

Of the three branches of government, the public has given Congress the lowest approval rating. Yet every election they send a majority of incumbents back to Congress. There seems to be a love/hate relationship between the people and their representatives and senators. Many suggestions have been made to improve and reform the organization and productivity of Congress. The poll pointed out the following beliefs:

■ Gridlock is a problem. Congress is considered inefficient, and because of the complicated legislative process, most bills never see the light of day. Reforms have been made, such as streamlining the committee system, improving the coordination of information between the House and the Senate, and requiring some kind of action on all bills proposed.

■ Congress does not reflect the views of its constituents. People have suggested that with the growth of the Internet, representatives should interactively get information from their constituents before voting on crucial issues.

■ Representatives are so busy running for office that they become beholden to special-interest groups and PACs. The response has been that some states voted to establish term limits. The Supreme Court decided this issue in 1995 and ruled that it was unconstitutional for states to enact term limits for senators and representatives.

■ Relations between Congress and the president have deteriorated when one party is in control of the executive branch and the other party controls one or both houses (divided government). When there is a fiscal crisis, the conflict between the branches increases.

The debt ceiling crisis in 2011, when the Republican-majority House fought the president over the debt limit having to be raised, and the fiscal cliff crisis at the end of 2012, when the Republican Congress resisted raising taxes for those couples making more than $500,000, are examples of the conflict between the president and the Congress.

Divided government, where one party controls the executive branch, and the opposition party controls one or both houses of Congress, was rejected by the American people in the 2016 presidential election. That election, when the Republicans maintained control of Congress and won the presidency, ended an era of divided government. This was reversed in 2018 when the Democrats regained control of the House of Representatives.

History of Divided Government

A party era exists when one political party controls either the executive branch and/or legislative branch. From 1968 to 2016 there was an era of divided government. It has been characterized by the election of a president having to deal with an opposition party in one or both houses of Congress.

With the election of Bill Clinton in 1992 and his reelection in 1996, the emergence of an ideological party era seemed to be on the horizon. Even though Clinton had a Democratic majority in both houses during his first term, much of his legislative agenda was embroiled in an ideological battle among liberals, moderates, and conservatives who did not always vote along party lines.

An example of divided government was signaled by the Republican takeover of Congress in 1994. In the 2000 election, divided government became the theme. After the presidential election when Vice President Al Gore received more popular votes than George W. Bush but still lost the electoral vote, Congress initially remained Republican but was closely divided. Then in 2001, the Democrats gained a majority in the Senate after a Republican senator left the party. In 2006, the midterm election—dominated by the Iraq War, and what some called the Bush administration’s “culture of corruption,” there was also a great deal of dissatisfaction with President Bush’s job performance. The end result was a Democratic takeover of Congress. The Democratic incumbents did not lose a single seat and gained 29 seats in the House and six seats in the Senate. The results of this election could be attributed to an unpopular president and a war that had lost public support. One thing is certain. Republican gains in the once-Democratic South suggest a continuation of the party realignment in that area of the country.

The 2008 presidential election was a short-lived start of a new party era—one-party majority rule. Barack Obama had the largest congressional majority since Lyndon Johnson, who also enjoyed a large Democratic majority in both houses of Congress. The era of divided government shifted to this new era of one-party dominance of the executive and legislative branches. This changed after the 2010 midterm election when Republicans regained control of the House of Representatives. In 2014, the GOP also gained more seats in the House and a majority in the Senate, strengthening their hand in policy debates with the president. The 2016 presidential election brought an end to divided government when Republican Donald Trump was elected president. Trump, along with the Republican Congress, had control of the three branches of government. This was reversed in 2018 when the Democrats regained control of the House of Representatives. Many political scientists question the strength of party eras because of the weakening of political parties as illustrated by the increasing number of independent voters, and the rise of the Tea Party. The first decade of this century can be described as a time where one party had majority rule until a “wave” election brought divided government. The rise of the so-called religious right, an evangelical conglomeration of ultraconservative political activists joining the Republican Party, has contributed to this rise of an ideological party era. The attempt at bipartisanship has been replaced by temporary coalitions that depend upon the issue of the day. After the 2000 election, political scientists began referring to the nation as divided into the “blue states” won by the Democrats and the “red states” won by the Republicans.

Fallout from Divided Government

During periods of divided government, when the president is from one party and the Congress has a majority from the other party, the president becomes a “lame duck” much earlier in his term than if the president’s party controlled the Congress. An example of how this played out occurred in President Obama’s second term. Justice Antonin Scalia suddenly died in early 2016, and President Obama named U.S. Court of Appeals Justice Merrick Garland as his replacement. But the Republican-controlled senate refused to hold hearings, asserting that the winner of the 2016 election should make that choice. President Trump named to the court a conservative justice, Neil Gorsuch, who was on a list of names he had unveiled during the campaign.

Optional Readings

Is Congress the “Broken Branch?” by David R. Mayhew (2009)

Key Quote:

“Congress exhibits a particular kind of popular democracy. It tends to incorporate popular ways of thinking—the tropes, the locutions, the moralisms, the assumptions, the causal stories and the rest that structure the meaning of political life in the mass public. Whether this is a service at all can be contested. But there it is. Generation after generation, Congress has juxtaposed popular styles of thinking to the thrusts of rationalization or high-mindedness often favored by the executive branch, the judiciary, or the intelligentsia.”

From Sam Rayburn to Newt Gingrich: The Development of the Partisan Congress, by Barbara Sinclair (2011)

Key Quote:

“The Republican party moves right: right-wing intellectuals and Evangelical Christians transform the Republican [P]arty—The internal engines of partisan polarization: the [H]ouse in the Democratic era—The internal engines of partisan polarization: the Republican [H]ouse—Unorthodox lawmaking in the hyperpartisan house—Partisan polarization, individualism, and lawmaking in the Senate—The President and Congress in a polarized environment—Filibuster strategies and PR wars: strategic responses to the transformed environment—From fluid coalitions to armed camps: the polarization of the National Political Community—The consequences of partisan polarization: the bad, the ugly, and the good?”

CONSTITUTIONAL REVIEW OF THE PRESIDENCY

■ Basis of constitutional power found in Article II

■ Must be 35 years old, a natural-born citizen, and a resident of the United States for 14 years

■ Chief executive

■ Commander in Chief of the armed forces

■ Power to grant pardons

■ Power to make treaties

■ Power to appoint ambassadors, justices, and other officials

■ Power to sign legislation or veto legislation

■ Duty to give a State of the Union report

■ Election by Electoral College

■ Definition of term limits, order of succession, and procedures to follow during presidential disability through constitutional amendments

■ Informal power based on precedent, custom, and tradition in issuing executive orders (orders initiated by the president that do not require congressional approval), executive privilege (keeping executive meetings private), signing statements (presidential statements made in conjunction with a president signing a bill), and creating executive agencies

Presidential Powers Are Bolstered Beyond the Expressed Powers in Article I

Besides the constitutional authority delegated to the president, the nation’s chief executive also has indirect roles. These duties—such as chief legislator, head of party, chief of state, and chief diplomat—truly define the scope of the presidency. Depending upon the skills of the person in office, the power of the presidency will increase or decrease. Each role has a direct relationship with either a political institution or governmental policy-making body. The skills and ability to use these roles result in a shared-power relationship.

The president as chief legislator develops legislative skills and a shared relationship with Congress. In developing a legislative agenda, the president sets priorities and works closely with members of Congress. Three contrasting presidents—Lyndon Johnson, Jimmy Carter, and Bill Clinton—developed different styles in this area. Johnson, having the experience as Senate majority leader, already had the skills of working with Congress when he assumed the office after Kennedy’s assassination. He was able to achieve a great deal of success with his Great Society programs. Carter, coming from the Georgia governorship, was unable to work with congressional leaders and did not implement his agenda. Clinton, although a former governor, used his support staff and developed a working relationship with his own party leaders who held a majority in each house. For the first three years of his presidency, Clinton was able to push through significant legislation, including the Family and Medical Leave Act, a National Service Program, AmeriCorps, and the Crime Bill. The fact that Democrats held a majority was a key factor in whether the president’s legislative agenda was completed.

After the 2006 midterm election, President George W. Bush had to work with Democratic majorities in the House and Senate. Legislative victories decreased, and he faced mounting criticism for the Iraq War. When Barack Obama was elected in 2008, he was able to use his political capital to pass a historic bill reforming the nation’s health care system.

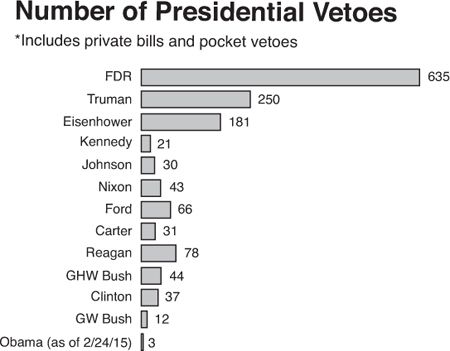

The Veto Is a Powerful Presidential Tool

The veto is a primary tool used by presidents to influence Congress to meet White House agenda priorities. Historically, there have been over 1,450 regular vetoes and fewer than 200 have been overridden by Congress. The presidents who exercised the most vetoes were Franklin Roosevelt (635), Grover Cleveland (304), and Harry Truman (1,100).

Pocket Veto Is Used Less Extensively

Another form of veto a president can use is the pocket veto. This occurs if the president does not sign a bill within ten days and the Congress adjourns within those ten days. This tactic has been used over a thousand times. One of the reasons why the pocket veto is used is that very often there is a rush to pass legislation at the time of planned recesses. One of the issues surrounding the veto is the attempt by some presidents to obtain a line-item veto. Many times, Congress will attach riders or amendments to bills. These riders, often in the form of appropriations, sometimes have nothing to do with the intent of the bill itself and are often considered to be pork-barrel legislation. It becomes a means of forcing the president to accept legislation he would normally veto.

Presidential Appointments that Must Be Confirmed Must Be Approved by the Senate

According to the Congressional Research Service, “The responsibility for populating top positions in the executive and judicial branches of government is one the Senate and the President share. The president nominates an individual, the Senate may confirm him, and the President would then present him with a signed commission. The Constitution divided the responsibility for choosing those who would run the federal government by granting the President the power of appointment and the Senate the power of advice and consent.” When the Senate refused to act on a presidential appointment, presidents have waited for the Senate to adjourn for three days or more. The president then used what is called a “recess appointment,” which bypasses the Senate for one year. This method has been challenged, and the Supreme Court ruled that recess appointments by the president are unconstitutional, even if the Senate only convenes in a pro forma session—opening and adjourning without doing any other business. Members of the president’s White House staff, such as the chief of staff and press secretary, do not have to go through the confirmation process.

Pardon Power Cannot Be Formally Challenged

The president’s influence over the judiciary comes from his power to appoint Supreme Court justices and grant pardons and reprieves. Most judicial appointments are made after checking the appointment with the senator of the state the appointee comes from. This kind of “senatorial courtesy” often guarantees the acceptance of the appointment. The difference between a pardon and a reprieve is that a reprieve is a postponement of a sentence and a pardon forgives the crime and frees the person from legal culpability. One of the most controversial pardons came in 1974, when Gerald Ford pardoned Richard Nixon, who had been named as an unindicted co-conspirator in the Watergate scandal. An instance when the court told the president he went too far was the Supreme Court decision in Nixon v United States (1974). The Court told Richard Nixon he must turn over the Watergate tapes and rejected his argument of executive privilege. An extension of the pardoning power is the power of amnesty. For instance, in 1977 Jimmy Carter granted a blanket amnesty to Vietnam War draft evaders who fled to Canada. President Clinton was criticized after granting over a hundred pardons in the last hours of his presidency. President Trump used his pardon power to make political statements of the people he pardoned. Trump was pressured by many Republicans and Democrats not to pardon the individuals indicted as a result of the 2016 presidential election investigation conducted by Special Counsel Robert Mueller.

Line-Item Veto Ruled Unconstitutional

In 1994 both houses of Congress passed a line-item veto law, which President Clinton signed. Taking effect in 1997, the purpose of the line-item veto was to let the president strike individual items from the 13 major appropriations bills submitted by Congress that he considered wasteful spending. The goal of the law was to prevent Congress from increasing appropriations with pork. The law was brought to the Supreme Court and was declared unconstitutional as an illegal expansion of the president’s veto power.

Informal Powers Complement Formal Powers

Besides the delegated powers listed at the beginning of this unit, the president has an implied power unique to the three branches—an inherent power to make policy without the approval of Congress. This power is derived from the chief-executive clause in the Constitution and the defined power of the president as commander in chief. The policy directives can come in the form of executive orders and executive actions, as well as foreign policy decisions that involve the commitment of troops and weaponry to foreign countries. Congress has pushed back on these powers by taking the president to court and passing the War Powers Act.

Other Powers of the President

Party Leader

As party leader, the president is the only nationally elected party official. Other party leaders, such as the Speaker of the House and the majority and minority leaders of the Senate and House, are elected by their own parties. In this role, the president has much influence in setting his agenda, especially if he is a member of the majority party. Many times, the president will make the argument to the congressional party leaders that their support will “make or break” the presidency. This kind of pressure was put on the Democratic Party when Bill Clinton lobbied for the passage of his first budget. Another key action the president can take to send a message to Congress is to impound funds. By this act the president refuses to release appropriated funds to executive agencies. President Nixon used this practice to curb congressional spending. Congress retaliated by passing the 1974 Congressional Budget and Impoundment Act, which set limits on impoundment and set up an independent Congressional Budget Office. Even though the presidency does not directly have the power to appoint Congressmen to committees, the president certainly can influence a party member by promising to support pet legislation of the congressperson in return for voting in favor of legislation supported by the president.

Executive Privilege

The president has interpreted the Constitution to allow for executive privilege, the ability of the president to protect personal material. Because the definition of executive privilege is not written, President Nixon, in trying to apply this to his Watergate tapes, did not succeed in protecting the tapes from a congressional committee investigating potential obstruction of justice charges.

Optional Reading

The Chief Magistrate and His Power, by William Howard Taft (1916)

Key Quote:

“It has been suggested by some that the veto power is executive. I do not quite see how. Of course, the President has no power to introduce a bill into either House. He has the power of recommending such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient to the consideration of Congress. But he takes no part in the running discussion of the bill after it is introduced or in its amendments. He has no power to veto parts of the bill and allow the rest to become a law. He must accept it or reject it, and his rejection of it is not final unless he can find one more than one-third of one of the Houses to sustain him in his veto. But even with these qualifications, he is still a participant in the legislation. Except for his natural and proper anxiety not to oppose the will of the two great legislative bodies, and to have harmony in the government, the reasons which control his action.”

THE CABINET AND WHITE HOUSE STAFF

The Cabinet

The cabinet was instituted by George Washington; every administration since has had one. There have also been unofficial advisors such as Andrew Jackson’s so-called Kitchen Cabinet. Cabinet appointees need Senate confirmation and play an extremely influential role in government. There are currently 19 cabinet-level positions. Creation or abolition of these agencies needs congressional approval. There have been cabinet name changes such as the change from Secretary of War to Secretary of Defense. Cabinet agencies have been created because national issues such as the environment, energy, and education are placed high on the national agenda. Cabinet-level positions have been expanded to include the Office of Management and Budget, the director of the Environmental Protection Agency, the vice president, the U.S. Trade Representative, the ambassador to the United Nations, and the chair of the Council of Economic Advisors. In 2002, the cabinet was expanded to include the director of Homeland Security. The vice president also is a permanent cabinet member. Cabinet officials have come from all walks of life. They are lawyers, government officials, educators, and business executives. Many cabinet officials are friends and personal associates of the president. Only three—Robert Kennedy as Attorney General, Ivanka Trump, and Jarred Kushner as presidential advisors and not members of the Cabinet—were relatives of the president. Presidents have used cabinet officials in other capacities. Nixon used his attorney general as campaign manager. Cabinets are scrutinized by the American public to see whether they represent a cross section of the population. It was only recently that full minority representation in the cabinet became a common practice. To put this issue in perspective, the first woman, Frances Hopkins, was appointed to the cabinet in Franklin Roosevelt’s administration.

Cabinet nominees have been turned down by the Senate. George H. W. Bush’s appointment of Texas Senator John Tower was rejected by the Senate as a result of accusations that Tower was a womanizer, had drinking problems, and had potential conflict-of-interest problems with defense contractors. During his term, President Clinton had trouble gaining approval of cabinet appointees. Zoë Baird was nominated as the first female Attorney General. However, because of allegations that Baird had hired an illegal alien as a nanny, Clinton was forced to withdraw the nomination. The event became known as “Nannygate.” Issues facing a president include how much reliance should be placed on the cabinet, whether a cabinet should be permitted to offer differing points of view, and how frequently cabinet meetings should be held. Each cabinet member does administer a bureaucratic agency and is responsible for implementing policy within the agency’s area of interest.

After Barack Obama was elected president, he established new “vetting” procedures (reviewing of one’s credentials) for his appointees. This procedure included a provision that no former lobbyist could serve in an office that the lobbyist had earlier tried to influence. President Obama’s first-term cabinet appointment reflected a “team of rivals” in key positions. He appointed his primary presidential campaign opponent, former First Lady Hillary Clinton, as secretary of state and kept Republican Robert Gates as the defense secretary. The rest of the cabinet reflected ethnic and gender diversity. In his second term, some of President Obama’s appointments were confirmed with significant Republican opposition. For the first time in Senate history, the secretary of defense appointee was filibustered before gaining Senate approval. President Donald Trump’s cabinet consisted of former generals, former opponents from the 2016 Republican primary, and wealthy business executives. No Democrats were appointed to Trump’s cabinet.

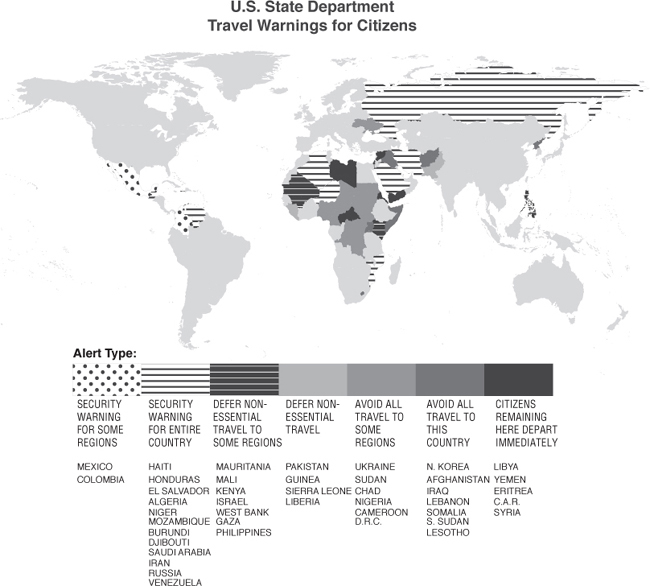

The president relies on two key cabinet departments for advice—the State Department and the Defense Department, both of which are run by civilians. He also relies on the national security advisor (a staff position), and the directors of National Intelligence, CIA, FBI, and Homeland Security. The secretary of defense is second to the president in directing military affairs. The agency is directly in charge of the massive defense budget and the three major branches of the military. Direct military command is under the leadership of the joint chiefs of staff. It is made up of representatives of each of the military services and chaired by a presidential appointee, also a member of the military. During the First Gulf War, General Colin Powell was a key player giving advice to President George H. W. Bush and Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney.

The secretary of state heads the diplomatic arm of the executive branch and supervises a department with well over 24,000 people, including 8,000 foreign-service officers. There are specialists in such areas as Middle East affairs, and the department includes the many ambassadors who are the country’s chief spokespersons abroad. Presidents appoint to the position of secretary of state someone on whom they can closely rely and who can map out a successful foreign policy. Some, like John Foster Dulles, Eisenhower’s secretary of state, have played a major role. Dulles endorsed the policy of brinkmanship—going close to the edge of an all-out war in order to contain communism. President Clinton appointed the first female secretary of state, Madeline Albright, at the start of his second term.

In 1947 the National Security Council was established as an executive-level department. It created as its head the national security advisor. One of the most notable people to head the agency was Henry Kissinger, who served under Presidents Nixon and Ford. Kissinger laid the foundation of Nixon’s policy during the Vietnam War and handled the delicate negotiations that led to Nixon’s historic visit to China. Condoleezza Rice became a key national security advisor to George W. Bush during his administration. She was appointed and confirmed as the first African-American woman to serve as Secretary of State during Bush’s second term.

The White House Staff

The White House staff, managed by the White House chief of staff, directly advises the president on a daily basis. The chief of staff, according to some critics, has an inordinate amount of power, often controlling the personal schedule of the president. Nixon’s chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, kept a personal diary, which revealed the position’s close relationship with the president as well as the influence the chief of staff plays in policy formation. Other staff members include the more than six hundred people who work at the White House, from the president’s chef to the “advance” staffers who make travel arrangements. The key White House staff include the political departments of the Office of Communications, Legislative Affairs, Political Affairs, and Intergovernmental Affairs. There are also the support services—Scheduling, Personnel, and Secret Service—and the policy offices—National Security Affairs, Domestic Policy Affairs, and cabinet secretaries. Each plays an important role in formulating policy and making the White House run smoothly. The first lady has her own office and staff, as does the vice president.

The role of the nation’s first lady is defined by the interests of the sitting president’s wife. Hillary Rodham Clinton was given the responsibility of chairing the Health Care Reform Task Force and moved from the traditional office in the White House reserved for the first lady to the working wing of the White House where other staff members work. After the efforts to get a comprehensive health care bill failed, Clinton took on a more traditional role as the country’s first lady. This role continued during Bill Clinton’s second administration. During the Whitewater investigation, Hillary Clinton was called to testify before a grand jury. No charges were brought against her. Using the theme of her book It Takes a Village to Raise a Child, Clinton was an important advocate for children’s causes. She also became the only former first lady to seek elective office. She was elected to the Senate in 2000 by the voters of New York, and in 2008 and 2016 was an unsuccessful presidential candidate. First Lady Michelle Obama followed Laura Bush’s model and used her influence in taking up the causes of preventing childhood obesity and working with veterans and their families. The newest first lady, Melania Trump, took on the cause of preventing cyberbullying.

Presidential Conflict with Congress over National Security

Another area of potential conflict between the president and Congress is that of national security. As chief diplomat, the president has the constitutional authority of commander in chief of the armed forces, the person who (with the advice and consent of the Senate) can make treaties with other nations and appoint ambassadors. Who are the players and participants in this aspect of public policy? Constitutionally we have already identified the key players:

■ President—in Article II, as commander in chief of the armed forces and chief diplomat; the president has the power to appoint ambassadors and negotiate treaties.

■ Congress—in Article I, having the power to declare war, support and maintain an armed force through appropriations, as well as approve foreign-aid allocations; the Senate has the power to approve appointments and must ratify treaties.

Illustrative Example

War Powers Act

It is the war-making power of the president that has caused the most problems. Since the Vietnam War, Congress has become concerned with the president’s unilateral commitment of American troops. Congress responded by passing the War Powers Act in 1973, overriding a Nixon veto. This act states that a president can commit the military only after a declaration of war by the Congress or by the specific authorization of Congress, if there is a national emergency, or if the use of force is in the national interest of the United States. Once troops are sent, the president is required to inform the Congress within 48 hours and must stop the commitment of troops after 60 days. Congress has the leverage of withholding military funding to force the president to comply. The War Powers Act has been compared to a legislative veto. The proponents of this measure point to such military action as Reagan’s invasion of Grenada, Bush’s Panama invasion, and Clinton’s Somalia and Bosnia policies as examples of why it is necessary for Congress to exercise this authority. Opponents of this act point to the fact that only the president has the complete knowledge of what foreign-policy actions can really have an impact on the national security of the United States. The issue has never been resolved by the courts, and the legislation remains on the books. In 2019, both houses of Congress passed a war powers resolution to pull U.S. support for the Saudi-led effort in Yemen. President Trump vetoed this legislation.

Presidential Conflict with the Senate over Supreme Court Nominees

The other two branches of government, the executive and legislative, are linked in the process of selecting federal justices. In addition, special interests such as the American Bar Association give their input. The result is a process that sometimes becomes embroiled in political controversy. The president must win the approval of the Senate for all federal judgeships. In addition, the tradition of senatorial courtesy, the prior approval of the senators from the state from which the judicial appointment comes, has been part of the appointment process. (This courtesy does not apply to Supreme Court justice nominations.) Once nominated, the judicial candidate must appear before the Senate Judiciary Committee and is given a complete background check by the Department of Justice. Usually, lower-court justices are not hand-picked by the president. They come from recommendations of other officials. Many lower-court judgeships are given as a result of prior political support of the president or the majority party in the houses of Congress.

The consideration of judicial ideology has become increasingly important in the selection of Supreme Court justices. When a Supreme Court nominee appears before the Senate Judiciary Committee, issues such as constitutional precedent, judicial activism, and the candidate’s legal writings and past judicial decisions come under scrutiny. Other issues such as opinions on interest groups, public opinion, media opinion, and ethical and moral private actions of the nominee have been part of the selection process. Let us look at four recent nominees to illustrate this subject.

When Justice Lewis Powell retired from the court in 1987, President Reagan nominated Robert Bork. Bork had been an assistant attorney general in the Justice Department and was part of the “Saturday Night Massacre,” when Nixon fired Attorney General Elliot Richardson. Bork was third in line and carried out Nixon’s order to fire the special prosecutor, Archibald Cox, who was investigating the Watergate break-in. Bork was a conservative jurist and believed in judicial restraint. Many of his writings were questioned, as well as a number of his views regarding minorities and affirmative action. He was rejected by the Senate.

After his defeat, the term “Borked” was coined. It refers to a presidential appointee who does not get approved by the senate because of ideological reasons. Douglas Ginsburg was nominated by Reagan after Bork’s rejection. He was also considered extremely conservative. Under intense Senate questioning, conflict of interest issues surfaced as well as allegations that Ginsburg had used marijuana when he was a professor in law school. Reagan withdrew his nomination and finally succeeded in getting unanimous Senate approval for the more moderate Anthony Kennedy.

The most heated debate over confirmation occurred when President Bush nominated Clarence Thomas in 1991 to replace the first African-American Justice, Thurgood Marshall. This nomination brought to national attention the actions of the male-dominated Judiciary Committee when it came to questioning both Thomas and witness Anita Hill. Thomas was narrowly confirmed by a vote of 52–48. The confirmation process brought to the forefront the conflict between the president’s constitutional authority to nominate the person he considers best qualified and the responsibility of the Senate to approve the nominee. The partisanship of the committee as well as the leaks leading to the testimony of Hill added to the controversy.

When Clinton became president, his first two nominees, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, reflected an attempt on his part to depoliticize the process. Both nominees received easy Senate approval.

The second term of George W. Bush brought about a major change in the makeup of the Supreme Court. Sandra Day O’Connor, the Court’s first female appointee retired, and Bush nominated John G. Roberts Jr. to replace her. Roberts had clerked for William Rehnquist in 1980 when Rehnquist was an associate justice. Roberts went on to serve on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 1992. He had argued 39 cases before the Supreme Court. Roberts described himself as a “strict constructionist,” one who relied heavily on precedent in determining the outcome of cases that came before him.

Before the confirmation process began, Chief Justice William Rehnquist died, and President Bush decided to nominate Roberts as chief justice, leaving O’Connor’s seat vacant until Roberts was confirmed. After the confirmation hearings were completed, the Senate voted to confirm Roberts as the seventeenth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Roberts became the youngest chief justice since John Marshall. Bush’s nominee to replace O’Connor was federal appeals judge Samuel Alito, who was confirmed by the Senate.

President Obama’s first two Supreme Court nominees, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, were approved by the Senate. This maintained the court’s 5–4 conservative majority. Obama was unable to appoint a third replacement to the court after Justice Antonin Scalia died. The Senate majority leader, a Republican, would not agree to hold confirmation hearings or a vote until a new president was elected in 2016. As of June 2019, President Trump had appointed two nominees to the court, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, increasing the court’s conservative majority.

THE NEW TECHNOLOGY AND THE PRESIDENCY

The Bully Pulpit

If you think of the presidents who have been powerful and influential and who have demonstrated leadership, they all have one thing in common. These presidents, such as Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan, all used the “bully pulpit” to advance their policies and communicate with the American people. The term was coined by Theodore Roosevelt, who saw the White House as his bully pulpit to advance his agenda. The bully pulpit is used by presidents to

■ manage a crisis,

■ demonstrate leadership,

■ announce the appointment of cabinet members and Supreme Court justices,

■ set and clarify the national agenda,

■ achieve a legislative agenda, and

■ announce foreign-policy initiatives.

Especially with the 24/7 news cycle covered by the media and social media, a president who knows how to use the bully pulpit has a powerful tool to advance the goals of the administration. The president also uses television to his advantage. The presidency has a great deal of access to television, making prime-time speeches such as the State of the Union address.

Media

As the Internet has grown, a new communications vehicle called social media has emerged. Social media include email, personal opinion pages called blogs, Facebook, and Twitter, and other sites that promote personal interaction. The result is a greater impact on the political agenda. The president can use his social media to bypass the mainstream media and go directly to the constituents, whether supporters in Congress or the political base. President Trump has been called “Twitter-in-Chief” because of his use of that medium. He has over 40 million followers on Twitter and millions of followers on Facebook. Trump’s tweets and Facebook postings as president serve as policy positions as well as communicate how he feels about his political supporters and opponents—postings that go directly to the country via Twitter and Facebook.

QUICK CONSTITUTIONAL REVIEW OF THE JUDICIARY

■ The basis of constitutional power is found in Article III.

■ Judges are appointed by the president with the consent of the Senate and serve for life, based on good behavior.

■ Judicial power extends to issues dealing with common law, equity, civil law, criminal law, and public law.

■ Cases are decided through original jurisdiction or appellate jurisdiction.

■ The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court presides over impeachment trials.

■ Congress creates courts that are “inferior” to the Supreme Court.

How the Supreme Court Exercises Its Power

Number of Cases Accepted for Oral Argument Is Also Known as Certiorari

Based on “the rule of four” (a minimum of four justices agreeing to review a case), the Supreme Court’s docket is taken up by a combination of appeals cases ranging from the legality of the death penalty to copyright infringement.

Prior to 2000, the court released audiotapes of cases argued on a delayed basis. The court released audiotapes for the first time in 2000, immediately following the disputed 2000 presidential election and the legal challenges that followed. The tapes were released to the media and could be heard on the Internet. They continued this practice during subsequent terms whenever there was a case that evoked a large amount of public interest, such as the University of Michigan affirmative action case, the Guantanamo Bay detainee case, and the same-sex marriage cases.

The process for a writ of certiorari (Latin for “to be made more certain”) to be heard is based on five criteria:

■ If a court has made a decision that conflicts with precedent.

■ If a court has come up with a new question.

■ If one court of appeals has made a decision that conflicts with another.

■ If there are other inconsistencies between courts of different states.

■ If there is a split decision in the court of appeals.

If a writ is granted, the lower court sends to the Supreme Court the transcript of the case that has been appealed. Lawyers arguing for the petitioner and respondent must submit to the court written briefs outlining their positions on the case. The briefs must be a specified length, must be on a certain color of paper, and must be sent to the Court within a specified period of time. Additional amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs may be sent to support the position of one side or the other. Once the case has been placed on the docket, the lawyers are notified, and they begin preparing for the grueling process of oral arguments before the court. Attorneys are often grilled for thirty minutes by the sitting justices. Often, the solicitor general of the United States represents the government in cases brought against it. Although these arguments offer the public insight into the legal and constitutional issues of the case, usually they do not change the positions of the judges. After a case is heard, the nine justices meet in conference. A determination is made whether a majority of the justices have agreed on an opinion on the outcome of the appeal.

Once a majority is established, sometimes after much jockeying, the chief justice assigns a justice to write the majority decision. Opposing justices may write dissenting opinions and, if the majority has a different opinion regarding certain components of the majority opinion, they may write concurring opinions. The decision of the case is announced months after it has been reached. Sometimes, when the case is significant, the decision is read by the Chief Justice. At other times a pur curiam decision, a decision without explanation, is handed down. Once a decision is handed down, it becomes public policy. The job of implementing a decision may fall on the executive branch, legislature, or regulatory agencies, or it may require states to change their laws.

Judicial Activism and Judicial Restraint Are Competing Judicial Philosophies

The Supreme Court in particular has a direct impact on public policy through its interpretation of the Constitution and how it relates to specific issues brought before the court.

A court that shows judicial restraint will maintain the status quo or mirror what the other branches of government have established as current policy. Decisions that established the legitimacy of state restrictions on abortions, such as parental approval, and a narrower interpretation of Miranda Rights (those rights guaranteed to people arrested) were characteristic of a more conservative Rehnquist court in the late 1980s and 1990s.

An activist court will plow new ground and, through such decisions as Roe v Wade (1973), or Brown v Board of Education (1954), establish precedents, also called stare decisis, that will force legislative action.

In the early days of the republic, arguments abounded around strict constructionist versus loose constructionist interpretation of the Constitution. Today, we see people arguing whether the court should be activist or demonstrate judicial restraint. All Supreme Court nominees are asked to describe their judicial philosophy.

The critics of judicial activism make the argument that it is not the court’s responsibility to set policy in areas such as abortion, affirmative action, educational policy, and state criminal law.

They believe the civil-liberty decisions have created a society without a moral fiber. The fact that judges are political appointees, are not directly accountable to the electorate, and hold life terms makes an activist court even more unpalatable to some.

On the other hand, proponents of an activist court point to the responsibility of the justices to protect the rights of the accused and minority interests. They point to how long it took for the doctrine of separate but equal to be overturned. And they point to how many states attempt to circumvent court decisions and national law through laws of their own. Proponents of judicial activism also make the argument that the Supreme Court is needed to be a watchdog and fulfill its constitutional responsibility in maintaining the system of checks and balances. As Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist No. 78, “Laws are dead letters without courts to expound and define their true meaning and operation.”

The critics of judicial restraint believe the interests of government are not realized by a court that refuses to make crucial decisions. They suggest the federal system will be weakened by a court that allows state laws that may conflict with the Constitution to go unchallenged. Proponents of judicial restraint point to the fact that it is the role of the Congress to make policy and the role of the president to carry out policy. They believe the court should facilitate that process rather than initiate it. They point to the fact that in many cases the Constitution does not justify decisions in areas where there are no references. The right to an assisted suicide, for instance, became an issue that advocates of judicial restraint urged the court to reject on the grounds that it was not a relevant federal issue to hear on appeal. The Rehnquist court, in fact, ruled against a group of physicians arguing for the constitutional right to assisted suicide. One of the ironies in the debate is that those favoring judicial restraint would like to see precedent be the guiding light. However, in declaring legislation unconstitutional and in creating new precedent, those advocating restraint have themselves become activists.

Limitations of Supreme Court Power

The Supreme Court’s power can only be limited in the following ways:

■ A Constitutional Amendment that would allow a vote to remove a Supreme Court Justice either by the Congress or the electorate. Texas Senator Ted Cruz advocated this after the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriage was constitutional.

■ Congress authorizing the president to appoint more justices. This was tried by Franklin Roosevelt in the famous court-packing proposal. Congress rejected it.

■ The president, Congress, or states not obeying a Supreme Court decision. Andrew Jackson successfully did this when the Supreme Court ruled that Native Americans could not be displaced. That decision resulted in the “Trail of Tears,” where thousands of Native-Americans were forcibly displaced from their homelands. Congress and the states have never directly disobeyed a Supreme Court decision. Congress has attempted to offer constitutional amendments, such as making flag burning illegal. States have challenged Supreme Court rulings such as Brown v Board of Education (1954) by not immediately implementing the decision.

CONSTITUTIONAL REVIEW OF BUREAUCRACIES

■ Constitutional basis found in Article II of the Constitution in the reference to the creation of executive departments.

■ Bureaucracies developed as a result of custom, tradition, and precedent.

Functions of Bureaucracies Are Key to Policy Making

Bureaucracies are defined as large administrative agencies and have their derivation from the French word bureau, which refers to the desk of a government worker, and the suffix cracy, indicating a form of government. Bureaucracies have similar characteristics. They reflect a hierarchical authority, there is job specialization, and there are rules and regulations that drive them.

Over four million government workers make up today’s federal bureaucracy. The number is even greater if you consider the number of state and local government workers. A little more than 10 percent of the federal employees actually work in Washington, D.C. The majority work in regional offices throughout the country. For instance, each state has many offices dealing with Social Security. About a third of the federal employees work for the armed forces or defense agencies. The number of workers employed by entitlement agencies is relatively small—only about 15–20 percent. The background of federal employees is a mix of ethnic, gender, and religious groups. They are hired as a result of civil service regulations and through political patronage. Even though many people feel bureaucracies are growing, they are in reality decreasing in size.

Year |

Executive Branch Civilians (Thousands) |

Uniformed Military Personnel (Thousands) |

Legislative and Judicial Branch Personnel (Thousands) |

Total Federal Personnel (Thousands) |

1991 |

3,048 |

2,040 |

64 |

5,152 |

1992 |

3,017 |

1,848 |

66 |

4,931 |

1993 |

2,947 |

1,744 |

66 |

4,758 |

1994 |

2,908 |

1,648 |

63 |

4,620 |

1995 |

2,858 |

1,555 |

62 |

4,475 |

1996 |

2,786 |

1,507 |

61 |

4,354 |

1997 |

2,725 |

1,439 |

62 |

4,226 |

1998 |

2,727 |

1,407 |

62 |

4,196 |

1999 |

2,687 |

1,386 |

63 |

4,135 |

2000 |

2,639 |

1,426 |

63 |

4,129 |

2001 |

2,640 |

1,428 |

64 |

4,132 |

2002 |

2,630 |

1,456 |

66 |

4,152 |

2003 |

2,666 |

1,478 |

65 |

4,210 |

2004 |

2,650 |

1,473 |

64 |

4,187 |

2005 |

2,636 |

1,436 |

65 |

4,138 |

2006 |

2,637 |

1,432 |

63 |

4,133 |

2007 |

2,636 |

1,427 |

63 |

4,127 |

2008 |

2,692 |

1,450 |

64 |

4,206 |

2009 |

2,774 |

1,591 |

66 |

4,430 |

2010 |

2,776 |

1,602 |

64 |

4,443 |

2011 |

2,756 |

1,583 |

64 |

4,403 |

2012 |

2,697 |

1,551 |

64 |

4,312 |

2013 |

2,668 |

1,500 |

63 |

4,231 |

2014 |

2,663 |

1,459 |

63 |

4,185 |

2015 |

— |

— |

— |

4,083 |

2016 |

— |

— |

— |

4,136 (est.) |

2017 |

— |

— |

— |

4,142 (est.) |

How Federal Workers Are Held Accountable

Workers in federal bureaucracies have different ways of being held accountable. They must respond to

■ the Constitution of the United States,

■ federal laws,

■ the dictates of the three branches of government,

■ their superiors,

■ the “public interest,” and

■ interest groups.

Even with the characteristics described, federal workers are complex individuals who are extremely professional in the jobs they are doing.

The federal government is organized by departments, which are given that title to distinguish them from the cabinet. Agencies and administration refer to governmental bodies that are headed by a single administrator and have a status similar to the cabinet. Commissions are names given to agencies that regulate certain aspects of the private sector. They may be investigative, advisory, or reporting bodies. Corporations are agencies headed by a board of directors and have chairmen as heads.

These agencies each have specific responsibilities that facilitate the day-to-day operation of the government. In reality, policy administration of federal bureaucracies has been limited by a number of checks, such as

■ the legislative power of Congress through legislative intent, congressional oversight, and restrictions on appropriations to agencies;

■ the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946, which defines administrative policy and directs agencies to publicize their procedures;

■ a built-in review process, either internal or through the court system, for appeal of agency decisions;

■ the oversight function of agencies such as the Office of Management and Budget and the General Accounting Office; and

■ political checks, such as pressure brought on by interest groups, political parties, and the private sector, which modifies bureaucratic behavior.

Relations with Other Branches of Government

Although they have independent natures, bureaucracies are linked to the president by appointment and direction and to Congress through oversight. Agency operations are highly publicized through the media when they have an impact on the public. Interest groups and public opinion try to influence the actions of the agencies.

Bureaucracies are inherently part of the executive branch. Even though the regulatory agencies are quasi-independent, they, too, must be sensitive to the president’s policies. The president influences bureaucracies through the appointment process. Knowing their agency heads are appointed by the president makes them respond to his direction for the most part. Bureaucracies such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) came under executive scrutiny in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Presidents also issue executive orders that agencies must abide by. The Veterans Administration (VA) came under close scrutiny in 2014 after a whistle blower revealed lax procedures and false information regarding care for veterans. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) can recommend increases and decreases in proposing new fiscal-year budgets. The budgetary process provides the impetus for agency growth. Finally, the president has the power to reorganize federal departments. President Reagan attempted to abolish the departments of Energy and Education but failed to get the approval of Congress. Congress uses similar tactics to control federal bureaucracies. Because the Senate must approve both presidential appointments and agency budgets, these become sensitive to the issues on Congress’s agenda. Through the process of congressional oversight, agency heads are called before congressional committees to testify about issues related to the workings of the agency.

You have to only go as far as tracing your daily routine to see how influential regulatory agencies have become. Some examples are the regulation of

■ cable television by the Federal Communications Commission,

■ food labeling by the Federal Trade Commission,

■ meat inspection by the Food and Drug Administration,

■ pollution control by the Environmental Protection Agency,

■ airline safety by the National Transportation Safety Board,

■ safety and reliability of home appliances by the Consumer Product Safety Commission,

■ seat belt mandates by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration,

■ gas mileage standards developed by the Department of Transportation,

■ the mediation of labor disputes by the National Labor Relations Board,

■ factory inspections for worker safety by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and

■ the coordination of relief efforts by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Bureaucracies Are First and Foremost Policy-Making Bodies