Political Participation (Unit 5) |

5 |

When looking at the interrelationship between government and politics, you need to understand the nature of political participation. Government has an impact on our everyday lives in many ways. Our federal form of government has a huge effect on how we are able to function as part of our society—from how our recycled garbage is picked up to the speed limit on interstate highways. How citizens participate influence many policy decisions.

A working definition of government is those institutions that create public policy. Constitutionally defined, the formal institutions of government on the national level are the executive branch headed by the president, the legislative branch consisting of the Congress, and the judicial branch made up of the Supreme Court and lower courts. A similar structure exists on the state and local levels. In addition to government’s defined institutions, modern government is also characterized by those agencies that implement public policy—bureaucracies, including regulatory agencies, independent executive agencies, government corporations, and the cabinet. These institutions, sometimes acting independently, sometimes in concert, create and implement public policy. There are also linkage institutions that encourage political participation and utilize support to influence public policy. By definition, a linkage institution is the means by which individuals can express preferences regarding the development of public policy. Examples of linkage institutions are political parties, special-interest groups, and the media. Preferences are voiced through the political system, and when specific political issues are resolved, they become the basis for policy.

Government, politics, and participation thus can be defined by a formula that combines the three concepts and reaches an end goal: government plus politics and participation equals the creation of public policy. In other words, what government does through politics and participation results in public policy.

The media, through daily newspapers and television newscasts as well as columnists and editorials, attempt to influence the voters, the party, and the candidate’s stand on issues. The media have been accused of oversimplifying the issues by relying on photo opportunities (photo ops) set up by the candidates and on 30-second statements on the evening news (sound bites). The interaction of linkage institutions results in the formation of a policy agenda by the candidates running for elected office.

People with similar needs, values, and attitudes will band together to form political parties. Once a political party is formed, in order for the needs, values, and attitudes to translate into actual policy, the party must succeed in electing members to office. Thus, individuals running for office must have a base of electoral support, a base of political support (the party), and a base of financial support. Obviously, the issue of incumbency comes into play as those elected officials who are reelected become entrenched in the system and have an advantage over young political hopefuls who want to break into the system.

In order to implement their policies, Democrats, Republicans, and Independents have to be elected to public office. Candidates and political parties must assess the nature of the electorate. Is there a significant number of single-issue groups, those special interests that base their vote on a single issue? Or is the candidate’s stand on the issues broad enough to attract the mainstream of the voting electorate? The role of the electorate is also crucial in determining the means with which individuals become involved. How the voters perceive the candidate’s positions on issues, the way people feel about the party, the comfort level of the voter in relation to the candidate and the party, as well as the influence the media have on the election—these all come into play in the eventual success or failure of the candidate.

The measure of a democracy is open and free elections. In order for a democracy to succeed, these elections have to be open to all citizens, and issues and policy statements of candidates have to be available to the electorate so citizens can form political parties to advocate policies, and elections would be determined by a majority or plurality.

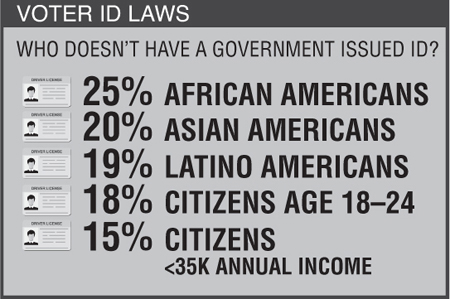

Amendments to the Constitution creating direct elections of senators; voting rights for freed slaves, women, and 18-year-olds; the elimination of poll taxes; and legislation such as the Voting Rights Bill have accomplished this. Participation in government and politics is another indicator. In 2012, many states attempted to pass legislation that would have made voting more difficult: these include voter-identification laws and limiting early-voting opportunities. Proponents of the legislation claimed these restrictive measures would prevent voter fraud. Opponents of these polices viewed it as voter suppression. Ultimately, the courts ruled many of these measures unconstitutional. In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, freeing nine southern states to change their election laws without advance federal approval. As a result, in the presidential election more states passed laws requiring voter IDs and restricting early voting. The courts invalidated many of these laws because they were discriminatory. In those states where the laws were implemented, there was a decrease in voter turnout.

Interest groups and political parties are both characterized by group identification and group affiliation. However, they differ in the fact that interest groups do not nominate candidates for political office. Their function is to influence officeholders rather than to end up as elected officials, and they are responsible only to a very narrow constituency. Interest groups can also make up their own bylaws, which govern how they run their organizations. Because the major function of these groups is the advocacy of or opposition to specific public policies, they can attract members from a large geographic area. The only criterion is that the person joining the group shares the same interest and attitude toward the goals of the organization.

How Civic Participation in a Representative Democracy drives elections and is impacted by the various kind of media.

How Competing Policy-Making Interests is driven by linkage institutions, the media, special-interest groups, political parties, and participation in elections, which are essential to the development and implementation of public policy.

How Methods of Political Analysis are used to measure public opinion.

Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002

Caucus

Closed primary

Coalitions

Critical elections

Demographic

Electoral College

Fifteenth Amendment

Free rider

Incumbency

Iron triangle

Issue network

Linkage institutions

Midterm election

Nineteenth Amendment

Open primary

Party convention

Party identification

Party realignment

Party-line voting

Political efficacy

Political platforms

Proportional voting

Prospective voting

Rational choice voting

Retrospective voting

Seventeenth Amendment

Single-issue group

Social movement

Twenty-fourth Amendment

Twenty-sixth Amendment

Winner-take-all voting

Participation in the political process is the key gauge of how successful political parties are in involving the average citizen. If you develop the actual vote as the key criteria, the future is certainly not bright. Unlike in many foreign countries, the American electorate has not turned out in droves in local or national elections. The reasons why people either vote or decide not to participate in the process depends on a number of factors. Then what does the future hold for the Democrats and Republicans? To answer this question, you must look at the continuum of political involvement.

There is no doubt that statistically the majority of the electorate participates in the political process in conventional ways. From those areas the majority of people participate in, to those areas that a minority participates in, the population as a whole generally is involved in one or more of the following:

■ discussing politics;

■ registering to vote;

■ voting in local, state, and national elections;

■ joining a specific political party;

■ making contact with politicians either by letter, phone, or social media;

■ attending political meetings;

■ contributing to political campaigns;

■ working in a campaign;

■ soliciting funds; and

■ running for office.

Yet one of the ironies of conventional political participation is that less than half of those who are eligible actually vote in most elections.

QUICK REVIEW OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL BASIS OF SUFFRAGE

■ Article I Section 2 Clause (1) required each state to allow those qualified to vote for their own legislatures to qualify as well to vote for the House of Representatives.

■ Article II Section 1 Clause (2) provided for presidential electors to be chosen in each state with the manner determined by state legislatures.

■ The Reserved Power clause of the Tenth Amendment gave the states the right to determine voting procedures.

■ The Fifteenth Amendment gave freed slaves the right to vote.

■ The Seventeenth Amendment changed the meaning of Article I Section 2 to allow eligible voters to elect senators directly.

■ The Nineteenth Amendment made it illegal for the states to discriminate against men or women in establishing voting qualifications.

■ The Twenty-fourth Amendment outlawed the poll tax as a requirement for voting.

■ The Twenty-sixth Amendment prohibited the federal government and state governments from denying the right of 18-year-olds to vote in both state and federal elections.

■ The Voting Rights Acts of 1957, 1960, and 1965 increased the opportunities for minorities to register and allowed the attorney general to prevent state interference in the voting process.

■ The Supreme Court decision in Baker v Carr (1962) established the one-man, one-vote principle.

■ Supreme Court decisions in the 1990s established that gerrymandering resulting in “majority-minority” districts was unconstitutional.

Party Identification

If we assume party identification is a key factor in determining voter turnout and voter preference, then we would assume the Democrats would have the edge. This was definitely true in Congress, where Democrats dominated both houses from World War II until 1994, when the Republicans gained control of the House as well as the Senate. When you look at presidential elections, personality and issues rather than party have been conclusive factors in determining the outcome of the election. In many elections, ticket splitting occurred more than straight party-line voting. This was especially evident in 1996, 2010, and 2014 when the voters kept in office a Democratic president and a Republican Congress. In order to vote, you must be registered. Historically, this was an important factor explaining why voter turnout was low. Party identification in 2016, according to the Gallup Poll, had 36 percent of the electorate identify themselves as Independent, 32 percent Democratic, and 27 percent Republican. In 2016 there was very little ticket splitting as Republican candidates running for reelection won in red states and Democratic candidates won in blue states.

Voting Declines

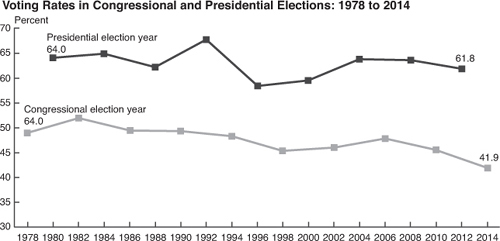

Even though it is easier for people to vote due to early voting opportunities in many states and a greater number of people have registered, there has been a consistent downward trend in voting from 1968 to 2014. The number of people of voting age has more than doubled since 1932. Yet after reaching a high in 1960, the percentage of eligible voters who voted actually declined (except for a small increase in 1984 and 1992). Because of the increase in young voters and successful efforts to enroll minorities and get them to vote, there was a significant increase in the 1992 election when close to 55 percent of the registered voters turned out. In 1996, because of negative voter reaction to the campaign issues raised by President Clinton and Senator Robert Dole, the voter turnout was again below 50 percent. In 2000 the percentage rose to a little above 50 percent. In 2004, there was a record voter turnout that translated into a 60 percent turnout. The 2008 presidential election saw an increase in voter registration and voter turnout. A little more than 62 percent of eligible voters turned out. In 2012 and 2016, the turnout was 58 percent. Since 1932 the highest presidential turnouts (60 percent or more) were in the three elections that took place in the 1960s. National and international events, as well as new legislation that increased voting opportunities for minorities, were probably responsible for the higher numbers. After Watergate the percentage of voters dropped dramatically. It is interesting to note that in off-year congressional elections, voter turnout is significantly lower. From 1974 to 2014 turnout in midterm congressional elections averaged around 40 percent. In 2018, however, a record turnout of more than 50 percent of eligible voters cast ballots in a wave election that had the Democrats retake control of the House of Representatives. Democrats had a nationwide 8.6 percent voting margin over the Republicans and gained 40 seats.

There is a real inconsistency between voter participation and the amount and type of media election coverage provided during campaigns. Everything from presidential debates to town meetings and an increased use of the mass media should result in an increased voter turnout. But because of a decline in party identification and a distrust of politicians, it seems that many eligible voters would rather sit out elections.

The Right to Vote, Also Known as Suffrage

The country has seen a tremendous change in the legal right to vote. When the Constitution was ratified, franchise was given to white male property owners only. Today there is a potential for over 234 million people who are at least 18 years old to vote. It has been a long struggle to obtain suffrage for individuals who were held back by such considerations as property ownership, race, religious background, literacy, ability to pay poll taxes, and gender. In addition, many state restrictions lessened the impact of federal law and constitutional amendments.

The aftermath of the Civil War provided a major attempt to franchise the freed blacks. However, the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment was countered by the passage of literacy laws and poll taxes in most Southern states. The progressive era of the early twentieth century saw the passage of two key amendments, the Seventeenth instituting the direct election of senators and the Nineteenth granting voting rights to women. After the Brown decision in 1954, Congress began formulating voting rights legislation such as the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and these changes were backed by the passage of the Twenty-fourth Amendment, eliminating the poll tax (or any other voting fee). The final groups to receive the vote were Washington, D.C., voters, as a result of the Twenty-third Amendment in 1961, and 18-year-olds, as a result of the passage of the Twenty-sixth Amendment in 1971. In 1992 Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition increased minority voter registration. To make voter registration easier for all groups, the Motor Voter Act of 1993 was signed into law by President Clinton. This law enabled people to register to vote at state motor vehicle departments. In fact, not since the Voting Rights Act of 1965 have so many new voters registered: more than 600,000 registered to vote.

Even though these trends resulted in an increase in the potential pool of voters, it was still left up to the individual states to regulate specific voting requirements. Such issues as residency, registration procedures, availability of voting machines and voting places, and voting times affect the ability of people to vote. However, federal law and Supreme Court decisions have created more and more consistency in these areas. For instance, the Supreme Court has ruled that a 30-day period is ample time for residency qualifications. The Motor Voter Act does provide for the centralization of voter registration along with local registration regulations. Some states have permitted 17-year-olds to vote in some primary elections. Literacy tests have been outlawed in every state as a result of the Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1970 and Supreme Court decisions.

Important Legislation That Advanced Voting Rights

The two significant pieces of modern legislation increasing voting opportunities were the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, previously discussed.

There are some cases where restrictions can exist on a person’s right to vote. People in mental institutions, the homeless, convicted felons, and dishonorably discharged military have been denied the right to vote in some states. Many states have increasingly passed different kinds of voter identification laws to ensure voter integrity. Opponents of these laws claim that the real reason they were passed was to reduce voter turnout among minorities and other groups who traditionally vote Democratic. The Justice Department has stepped in, and many of these laws have been ruled unconstitutional. Although the impact on presidential elections has been negligible, laws that are implemented could potentially reduce turnout in future elections.

Models of Voting Behavior

The different methods of voting behavior include:

■ Retrospective voting—refers to the decisions people make on voting based on how political parties perform, how elected officials perform, and the extent to which an elected administration achieves its goals. Retrospective voters are more concerned with policy outcomes than the tactics used to achieve policy.

■ Rational Choice Voting—refers to voting based on decisions made after considering alternative positions.

■ Prospective Voting—refers to voters deciding that what will happen in the future is the most important factor. If the voter feels the party in power has done a poor job, that voter will vote for the other party. That is why, in a campaign, candidates stress what they will do for the voter if they get elected.

■ Party-line voting—refers to voting for the same party for every office that candidates are running for. Those voters who have the strongest party identification are most likely to vote the party line. A 2014 survey found that only 34 percent of voters voted on a straight party line.

Why People Vote

There are many factors that explain how attitudes, perceptions, and viewpoints individuals hold about politics and government impact voting. Some political scientists view this process as one of political socialization. It is interesting to see the parallels between the factors that influence voting patterns and the factors that shape public opinion and political socialization. They include:

■ the family,

■ the schools,

■ the church,

■ models of public opinion, and

■ the mass media.

People internalize viewpoints at a very early age and act on them as they grow older. “Family values” has become an overused phrase, but in fact it is the primary source of the formulation of political opinions. When Vice President Dan Quayle made family values an election issue in 1992, he touched a chord that set off a debate. The reality is that children internalize what they hear and see within their family unit. If a child lives with a single parent, that child will certainly have strong attitudes about child support. If parents tend to speak about party identification, most children will tend to register and vote for the same party as their parents. Schools and the church play a secondary role in the formation of political views. There is no doubt that the Catholic Church’s position on abortion has had a tremendous impact on Catholics taking a stand for the “right to life.” However, the family unit reinforces the viewpoint.

Schools and teachers inculcate the meaning of citizenship at very early ages. Children recite the Pledge of Allegiance and sing the national anthem. Depending upon how open the educational system is, students will also learn how to question the role of government.

Voting Patterns Influenced by Political Socialization, Party Identification, and Political Ideology

In order to understand why people vote, you must look first at the potential makeup of the American electorate. Demographic patterns are determined every ten years when the census is conducted. Besides establishing representation patterns, the census also provides important information related to the population’s

■ age,

■ socioeconomic makeup,

■ place of residence and shifting population movement,

■ ethnicity, and

■ gender.

The 2010 Census

Key aspects of the 2010 census reflect an increase in the aging of America, a population shift to the Sunbelt states, and a decrease in those who would be classified as earning an income close to or below the poverty level. The 2010 U.S. census results released by the Census Bureau indicated major changes in the population of the United States and in population shifts from large industrial states to the Sunbelt of the South and Southwest. Specifically:

■ the official U.S. population count is 325.7 million in 2017. In 2000 the population was 281,421,906. That is a growth rate of 9.7 percent, the lowest growth rate since the Great Depression.

■ minorities, especially Hispanics, make up a growing share of the U.S. population and are the largest ethnic group.

■ children are much more likely to be racial/ethnic minorities than adults.

■ the fastest-growing states are in the South and West.

■ southern and western states gained seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, while northeastern and midwestern states lost seats.

■ metropolitan areas with the fastest rates of growth are mostly in the South and West; the fastest rates of decline tend to be in the Northeast and Midwest.

■ most U.S. population growth during the past century has taken place in suburbs, rather than in city centers.

■ the states of Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania lost congressional seats. New York and Ohio lost two seats.

■ the states that gained seats were Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Nevada, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, and Washington. Texas gained four seats. Florida gained two seats.

Immigrant patterns and these factors have public-policy consequences and are therefore important to the political process. Other factors, such as whether it is a presidential election or a midterm congressional election, impact voter turnout. There is a greater turnout in presidential elections than midterm elections. Voter turnout in presidential elections since 1960 is between 50 and 60 percent compared to around 40 percent in congressional elections.

A Look at the 2020 Census

Although the 2020 census will not impact the presidential election held that year, it could have a profound effect on the 2022 midterms and the 2024 election. Some reasons are demographic. Racial diversity in the United States continues to increase. And, any census question regarding citizenship could have an effect. But, there have been significant state population changes since 2010, and studies show that 16 states will likely either gain or lose a congressional seat after the 2020 census. The biggest winner should be Texas, which could gain three or four electoral votes. Florida, Arizona, Colorado, North Carolina, and Oregon will also gain electoral votes. The biggest losers will be the Rust Belt states—Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. New York, West Virginia, Alabama, and Rhode Island will also lose votes. Many of these states are battleground states in presidential elections.

Optional Readings

Issue Salience and Party Choice, by David RePass

Key Quote:

“As the parties move farther apart on the liberal-conservative spectrum, cross pressured voters—those who pair left-wing economic positions with right-wing social attitudes and vice versa—face a starker choice between the two primary issue dimensions in American politics.”

Stepping Up: The Impact of the Newest Immigrant, Asian, and Latino Voters, by Rob Parel

Immigration Policy Center (2013)

“Across both Democratic and Republican congressional districts, demographics shifts are taking place that will significantly alter the composition of the electorates. Author Rob Parel points out that young Asian and Latino teenagers coming of age, as well as newly naturalized immigrants, will have a major impact on the profile of newly eligible voters in upcoming elections. Using data from the U.S. Census and the Department of Homeland Security, the paper finds that about 1.4 million newly naturalized citizens and 1.8 million first-time Asian and Latino voters will participate in each two-year election cycle, and together these groups will constitute 34 percent of all new eligible voters in the 2014 elections alone. Congressional districts across the country but particularly in California, Texas, Florida, Illinois, New York, New Jersey and New Mexico will see substantial increases in the Asian and Latino composition of new voters. As a result, Parel suggests that representatives must be cognizant of how their decisions today and in the future on matters such as comprehensive immigration reform will impact not only the current electorate but also the electorate in the 2014 and future elections.”

The first linkage institution, political parties and how they influence policy making through political action, will be developed in this chapter. We will cover the major tasks, organization, and components of political parties. We will contrast the party organization with its actual influence on the policy makers in government. Then we will look at the history of the party system in America, evaluating the major party eras. The impact of third parties on the two-party system will also be discussed.

We will also analyze the ideology of the two major parties by looking at their platforms versus the liberal/conservative alliances that have developed. These coalitions may be the first step in the breakdown of the two-party system as we know it.

The Two-Party System

The nature of the party system in America can be viewed as competitive. Since the development of our first parties—the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans—different philosophies and approaches to the development and implementation of public policy have determined which party and which leaders control the government. Our system has been one of the few two-party systems existing in democracies; however, the influence of third-party candidates cannot be underestimated. Parliamentary democracies have multiparty systems.

Because the aim of a political party is to influence public policy, in order to succeed, parties must draw enough of the electorate into their organization and ultimately must get enough votes to elect candidates to public office. You can, therefore, look at a political party in three ways:

■ as an organization,

■ its relationship with the electorate, and

■ its role in government.

In order to achieve their goals, all political parties have the following common functions:

■ nominating candidates who can develop public policy,

■ running successful campaigns,

■ developing a positive image,

■ raising money,

■ articulating these issues during the campaign so that the electorate will identify with a particular party or candidate,

■ coordinating, in the governing process, the implementation of the policies they supported, and

■ maintaining a watchdog function if they do not succeed in electing their candidates.

The completion of each of these tasks depends on how effective the party’s organization is, the extent the party establishes its relationship with the electorate, and how it controls the institutions of government. A complete discussion of these components and functions will take place in other parts of the chapter.

Party Eras

The First Party era (1828–1860) was characterized by the Democrats dominating the presidency and Congress. The Second period (1860–1932) could be viewed as the Republican era. The Third era (1932–1968) gave birth to the success of the New Deal and was dominated by the Democrats. Divided government, in which one party controls the presidency and another party controls one or both houses of Congress, has dominated since 1968.

Party Realignment

Party realignment, the shift of party loyalty, occurred in 1932 after the country experienced the Great Depression. Fed up with the trickle-down economic theories of Herbert Hoover, the public turned to the New Deal policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt. A new coalition of voters supported FDR’s New Deal. They included city dwellers, blue-collar workers, labor-union activists, the poor, Catholics, Jews, the South, and African Americans where they could vote. An unusual alliance of northern liberals and southern conservatives elected Roosevelt to an unprecedented four terms. This coalition, with the exception of Eisenhower’s election, held control of the White House and Congress until 1968. A direct comparison can be made among Roosevelt’s New Deal, Kennedy’s New Frontier, and Johnson’s Great Society philosophy and election coalition. The growth of the federal government and the growth of social programs became part of the Democratic platform. However, a party realignment began as Johnson fought for civil rights legislation. The Democratic “solid South” turned increasingly Republican, both on the state and national levels as southern white voters rejected the Democratic support for civil rights. In 1989, the so-called Reagan Democrats, blue-collar workers, signaled a new party realignment to the Republican Party. Reagan Democrats reemerged as a decisive factor in the 2016 election, many voting for Donald Trump, especially in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, three battleground states that he won.

Period of Divided Government

The ongoing Vietnam War and Nixon’s promise to end the war brought the Republicans back to power in 1968. Since then, they have won seven of twelve presidential elections but were unable to control Congress until 1994. That is why this modern period has been called the period of divided government. The Watergate scandal and Nixon’s resignation in 1974 saw a weakened GOP and the eventual loss by Gerald Ford to Jimmy Carter in 1976. That election signaled a new southern strategy, which Ronald Reagan was able to capitalize on in 1980. Pulling a constituency that has been labeled as “Reagan Democrats,” Reagan attracted a traditional Democratic base of middle-class workers to his candidacy. Reagan faced a Democratic majority in the House but had the support of a Republican Senate from 1981–1986. George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump had to deal with divided government during their presidencies.

Third Parties

Third political parties, also called minor parties, have played a major role in influencing the outcome of elections and the political platforms of the Democrats and Republicans. Even though these smaller parties and their leaders realize that they have virtually no chance to win, they still wage a vocal campaign. These third parties can be described as ideological, single-issue oriented, economically motivated, and personality driven. They have been called Socialist, Libertarian, Right to Life, Populist, Bull Moose, and United We Stand. But they all have one thing in common—an effort to influence the outcome and direction of an election. Let us look at some of the more successful third-party attempts.

The modern third-party impact has revolved around a political leader who could not get the nomination from his party. George Wallace’s American Independent Party of 1968 opposed the integration policies of the Democratic Party, and he received 13 percent of the vote and 46 electoral votes, contributing to Hubert Humphrey’s defeat in a very close election. John Anderson’s defection from the Republican Party in 1980 and his decision to run as a third-party candidate had a negligible effect on the outcome of that election.

The announcement by Texas billionaire H. Ross Perot that he was entering the 1992 presidential race, and using his own money to wage the campaign, changed the nature of that race. He announced his intention to run on CNN’s Larry King Show and said that if his supporters could get his name on the ballot in all 50 states he would officially enter the race. A political novice, he decided to drop out of the race the day Bill Clinton was nominated by Democrats. He then reentered the heated contest in October, appeared in the presidential debates, and struck a chord with close to 20 percent of the electorate. His folksy style and call for reducing the nation’s deficit played a significant role in the campaign. He did not win a single electoral vote, but won almost 20 percent of the popular vote. Ralph Nader running as the Green Party candidate hurt Al Gore’s chance in the contested 2000 election. In 2016, third-party candidates won 5 percent of the popular vote.

Even though there has been a history of third-party movements, they do not succeed at the ballot box because there are built-in obstacles. Factors like winner-take-all voting districts act as an impediment to third-party candidates.

Party Dealignment

If party realignment signifies the shifts in the history of party eras, then people gradually moving away from their parties has become more of a trend in today’s view of party loyalty. This shift to more neutral and ideological views of party identification has been termed “party dealignment.” Party dealignment is also characterized by voters who are fed up with both parties and register as independents. This trend has been on the rise and, in party-identification surveys, more than one-third of voters identify as independents. Those who are strong party loyalists believe the party matches their ideology. The shift of traditional Southern Democrats to the Republican Party came about because many voters perceived the Republicans as more conservative than the Democrats. Women activists, civil-rights supporters, and people who support abortion rights make up the Democratic coalition because the Democratic Party has supported these issues in their national platform. Party organization and party support have remained stronger than party identification because of the ability of the parties to raise funds and motivate their workers.

Optional Reading

A Comparison of the 2016 Democratic and Republican Party Platforms

Republican Platform |

Key Issue |

Democratic Platform |

“The Constitution’s guarantee that no one can ‘be deprived of life, liberty or property’ deliberately echoes the Declaration of Independence’s proclamation that ‘all’ are ‘endowed by their Creator’ with the inalienable right to life. Accordingly, we assert the sanctity of human life and affirm that the unborn child has a fundamental right to life which cannot be infringed. We support a human life amendment to the Constitution and legislation to make clear that the Fourteenth Amendment’s protections apply to children before birth.” |

Human Life |

“Democrats are committed to protecting and advancing reproductive health, rights, and justice. We believe unequivocally that every woman should have access to quality reproductive health care services, including safe and legal abortion—regardless of where she lives, how much money she makes, or how she is insured. We believe that reproductive health is core to women’s, men’s, and young people’s health and well being…. We will continue to oppose—and seek to overturn—federal and state laws and policies that impede a woman’s access to abortion, including by repealing the Hyde Amendment.” |

“We oppose the use of public funds to perform or promote abortion or to fund organizations, like Planned Parenthood, so long as they provide or refer for elective abortions or sell fetal body parts rather than provide health care.” |

Planned Parenthood |

“We will continue to stand up to Republican efforts to defund Planned Parenthood health centers, which provide critical health services to millions of people.” |

“We support the appointment of judges who respect traditional family values and the sanctity of innocent human life.” |

Judges |

“We will appoint judges who defend the constitutional principles of liberty and equality for all, protect a woman’s right to safe and legal abortion, curb billionaires’ influence over elections because they understand that Citizens United has fundamentally damaged our democracy, and see the Constitution as a blueprint for progress.” |

“We value the right of America’s religious leaders to preach, and Americans to speak freely, according to their faith. Republicans believe the federal government, specifically the IRS, is constitutionally prohibited from policing or censoring speech based on religious convictions or beliefs, and therefore we urge the repeal of the Johnson Amendment.” |

Religious Liberty |

“Democrats know that our nation, our communities, and our lives are made vastly stronger and richer by faith in many forms and the countless acts of justice, mercy, and tolerance it inspires. We believe in lifting up and valuing the good work of people of faith and religious organizations and finding ways to support that work where possible.” |

“We firmly believe environmental problems are best solved by giving incentives for human ingenuity and the development of new technologies, not through top-down, command-and-control regulations that stifle economic growth and cost thousands of jobs.” |

Climate Change/Global Warming |

“Climate change is an urgent threat and a defining challenge of our time…. We believe America must be running entirely on clean energy by mid-century.” |

“We support options for learning, including home-schooling, career and technical education, private or parochial schools, magnet schools, charter schools, online learning, and early-college high schools. We especially support the innovative financing mechanisms that make options available to all children: education savings accounts (ESAs), tuition tax credits.” |

Education/School Choice |

“Democrats are also committed to providing parents with high-quality public school options and expanding these options for low-income youth. We support great neighborhood public schools and high-quality public charter schools, and we will help them disseminate best practices to other school leaders and educators. Charter schools focus on making a profit off of public resources.” |

“We renew our call for replacing ‘family planning’ programs for teens with sexual risk avoidance education that sets abstinence until marriage as the responsible and respected standard of behavior.” |

Sex Education |

“We recognize that quality, affordable comprehensive health care, evidence-based sex education, and a full range of family planning services help reduce the number of unintended pregnancies.” |

“Any honest agenda for improving health care must start with repeal of the dishonestly named Affordable Care Act of 2010: Obamacare…. |

Obamacare |

“Thanks to the hard work of President Obama and Democrats in Congress we took a critically important step towards the goal of universal health care by passing the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which has offered coverage to 20 million more Americans and ensured millions more will never be denied pre-existing condition.” |

“We condemn the Supreme Court’s ruling in United States v Windsor, which wrongly removed the ability of Congress to define marriage policy in federal law. We also condemn the Supreme Court’s lawless ruling in Obergefell v Hodges …. In Obergefell, five unelected lawyers robbed 320 million Americans of their legitimate constitutional define marriage as the union of one man and one woman.” |

Marriage |

“Democrats applaud last year’s decision by the Supreme Court that recognized LGBT people—like every other American—have the right to marry the person they love. But there is still much work to be done.” |

“We call for expanded support for the stem cell research that now offers the greatest hope for many afflictions—through adult stem cells, umbilical cord blood, and cells reprogrammed into pluripotent stem cells—without the destruction of embryonic human life. We urge a ban on human cloning for research or reproduction, and a ban on the creation of, or mentation on, human embryos for research.” |

Medical Research |

“Democrats believe we must accelerate the pace of medical progress, ensuring that we invest more in our scientists and give them the resources they need to invigorate our fundamental studies in the life sciences in a growing, stable, and predictable way … funded National Institutes of Health to accelerate the pace of medical progress.” |

“We consider the Administration’s deal with Iran, to lift international sanctions and make hundreds of billions of dollars available to the Mullahs, a personal agreement between the President and his negotiating partners and non-binding on the next president …. Because of it, the defiant and emboldened regime in Tehran continues to sponsor terrorisms the region, develop a nuclear weapon, test-fire ballistic missiles inscribed with ‘Death to Israel,’ and abuse the basic human rights of its citizens.” |

Iran |

“We support the nuclear agreement with Iran because, if vigorously enforced and implemented, it verifiably cuts off all of Iran’s pathways to a bomb without resorting to war.” |

“The integrity of our country’s foreign assistance program has been compromised by the current Administration’s attempt to impose on foreign recipients, especially the peoples of Africa, its own radical social agenda while excluding faith-based groups—the sector with the best track record in promoting development—not conform to that agenda. We pledge to reverse this course …. ” |

ForeignAssistance |

“We will support sexual and reproductive health and rights around the globe. In addition to expanding the availability of affordable family planning information and contraceptive supplies, we believe that safe abortion must be part of compre-hensive maternal and women’s health care America’s global health programming.” |

HOW POLITICAL PARTIES ARE ORGANIZED

Political parties exist on both the national and local levels. Their organization is hierarchical. Grass-roots politics on the local level involves door-to-door campaigns to get signatures on petitions, campaigns run through precinct and ward organizations, county committees, and state committees headed by a state chairman. Local party bullies like William “Boss” Tweed or Democratic party machines like Tweed’s Tammany machine in nineteenth-century New York City or the Daley machine in twentieth-century Chicago have diminished in influence. The national political scene is dominated by the outcome of national conventions, which give direction to the national chairperson, the spokesperson of the party, and the person who heads the national committee. The party machine exists on the local level and uses patronage (rewarding loyal party members with jobs) as the means to keep party members in line.

The nominating process drives the organization of the national political party. This procedure has evolved and, even though the national nominating convention (more on this in the next chapter) still selects presidential candidates, the roles of the party caucus and party primary have grown in importance. The role of the national convention is one of publicizing the party’s position. It also adopts party rules and procedures. Sometimes this plays an important part in the restructuring of a political party. After the disastrous 1968 Democratic Convention, with antiwar rioting in the streets and calls for party reform, the McGovern–Frasier Commission brought significant representation changes to the party, making future conventions more democratic. Delegate-selection procedures aimed to include more minority representation. In 1982 another commission further reformed the representation of the Democratic Convention by establishing 15 percent of the delegates as “superdelegates” (technically uncommitted delegates chosen from party leaders and elected party officials). These delegates helped Walter Mondale achieve his nomination in 1984 and enabled Al Gore to defeat Bill Bradley easily in 2000. Superdelegates played a significant role in the 2008 Democratic primaries. Primary elections were completed in June, and neither Barack Obama nor Hillary Clinton had a majority of the delegates. Ultimately, the superdelegates turned to Obama, giving him a majority and enabling him to clinch the nomination. In 2016, there was criticism that these delegates have reduced the intent of the democratic reforms of the McGovern Commission. After the 2016 presidential election, the Democratic National Committee voted to reduce the power of superdelegates. Even though elected party officials would still hold that position, they would not vote on the first ballot at the national convention; however, if no nominee received a majority of votes on the first ballot, the superdelegates would be able to vote on the second ballot and until a nominee was chosen. Ironically, with more than 15 candidates running for president in 2020 and every state having proportional voting results, there is a high probability that there will be a deadlocked convention.

The Republicans, on the other hand, were more concerned about regenerating party identification after the Watergate debacle. They were not interested in reform as much as making the Republican Party more efficient. Their conventions are well run and highly planned. There was, however, some negative publicity at their 1992 convention, which critics said was dominated by the conservative faction of the party. The lesson was learned. In 1996–2016, the Republican and Democratic conventions were highly scripted.

The National Committee

The governing body of a political party is the national committee, made up of state and national party leaders. This committee has limited power and responds to the direction of the national chairperson. The chairperson is selected by the presidential candidates nominated at the convention. In fact, the real party leader of the party in power is the president himself. The chairperson is recognized as the chief strategist and often takes the credit or blame for gains or losses in midterm elections. Some of the primary duties of the national chairperson are fundraising, fostering party unity, recruiting new voters and candidates, and preparing strategy for the next election.

Also, congressional campaign committees in both parties work with their respective national committees to win Senate and House seats that are considered up for grabs.

The future of political parties depends on how closely associated the voters remain with the party. The future is not bright for traditional party politics. There has been a sharp decline in party enrollment and an increase in the affiliation of voters calling themselves independents. More and more ticket splitting (where voters cast ballots, not on party lines, but based upon each individual candidate running for a particular office) has taken place. The impact of the media on the campaign has weakened the ability of the party to get its message out. Finally, the impact of special-interest groups and PACs has reduced the need for elected officials to use traditional party resources.

Suggestions have been made to strengthen voter identification with the party by presenting

■ clearly defined programs on how to govern the nation once their candidates are elected.

■ candidates who are committed to the ideology of the party and are willing to carry out the program once elected.

■ alternative views of the party out of power.

The winning party must take on the responsibility of governing the country if elected and accepting the consequences if it fails. This responsible party model would go a long way in redefining the importance of political parties in America. Even though there is a recognized decline in the importance of political parties, it is highly doubtful that our two-party system will change to a multiparty or ideological party system in the foreseeable future.

Interest Groups as a Linkage to Public Policy

Characteristics of Special-Interest Groups

For the purposes of establishing a common understanding, the definition of an interest group is a linkage group that is a public or private organization, affiliation, or committee that has as its goal the dissemination of its membership’s viewpoint. The result will be persuading public policy makers to respond to the group’s perspective. The interest groups’ goals are carried out by lobbyists and political action committees. They can take on an affiliation based on specialized memberships such as unions, associations, leagues, and committee and single-issue groups such as the National Rifle Association.

In trying to persuade elected officials to their position, these groups provide a great deal of specialized information to legislators. Group advocates also claim they provide an additional check and balance to the legislative system. Critics of the growth of specialized groups claim they are partly responsible for gridlock in government. In addition, critics point to how groups gain access to elected officials as a tradeoff for political contributions.

Once a specialized group is formed, it also has internal functions such as attracting and keeping a viable membership. Groups accomplish this by making promises to their membership that they will be able to succeed in their political goals, which in the end will benefit the political, economic, or social needs of the members. For example, if people want stricter laws against drunk driving and join Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), they feel a political and social sense of accomplishment when federal law dictates a national minimum drinking age along with federal aid to states for highway construction. For these groups to succeed, they also must have an adequate financial base to establish effective lobbying efforts or create separate political action committees. Dues may be charged or fundraisers might be held. The internal organization will certainly have elected officers responsible to their membership.

Group Theory

The nature of special-interest group membership is not representative of the population as a whole; consequently, the importance of group theory will help explain the context in which these groups develop. It is interesting to note that many have as their members people with higher than average income and education levels and many who are white-collar workers. However, this is balanced by the number of groups that have proliferated and represent the interests of union members and blue-collar workers. A problem interest groups face is the “free rider,” where members of a special interest group join without contributing to it with money or time.

Optional Reading

The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (1965), by Mancur Olson

From the publisher:

“This book develops an original theory of group and organizational behavior that cuts across disciplinary lines and illustrates the theory with empirical and historical studies of particular organizations. Applying economic analysis to the subjects of the political scientist, sociologist, and economist, Mancur Olson examines the extent to which the individuals that share a common interest find it in their individual interest to bear the costs of the organizational effort. The theory shows that most organizations produce what the economist calls “public goods”—goods or services that are available to every member, whether or not he has borne any of the costs of providing them. Economists have long understood that defense, law and order were public goods that could not be marketed to individuals, and that taxation was necessary. They have not, however, taken account of the fact that private as well as governmental organizations produce public goods. The services the labor union provides for the worker it represents, or the benefits a lobby obtains for the group it represents, are public goods: they automatically go to every individual in the group, whether or not he helped bear the costs. It follows that, just as governments require compulsory taxation, many large private organizations require special (and sometimes coercive) devices to obtain the resources they need.”

How Special-Interest Groups Got Legitimacy

Once the Constitution was ratified and the Bill of Rights was added, the First Amendment seemed to give legitimacy to the formation of special-interest groups. Their right of free assembly, free speech, and free press and the right to petition justified group formation. Groups could associate with each other, free from government interference, disseminate the issues they believe in to their membership and to government officials, and attempt to influence the course of public policy.

Mode of Operation of Special-Interest Groups

As interest groups have grown in number and size, they have also become specialized, representing narrow concerns. The following represents a cross section of the different kinds of interest groups that have organizations:

■ Economic and occupational including business and labor groups, trade associations, agricultural groups, and professional associations

—National Association of Manufacturers

—Airline Pilots Association

—AFL-CIO

—American Farm Bureau

—United States Chamber of Commerce

■ Energy and environmental

—American Petroleum Institute

—Sierra Club

■ Religious, racial, gender, and ethnic

—National Organization for Women

—National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

—National Urban League

■ Political, professional, and ideological

—Common Cause

—American Medical Association

—Veterans of Foreign Wars

—National Rifle Association

The majority of these groups have headquarters in Washington, D.C., and all have operating budgets and staffs. Most have hired lobbyists who make contacts with senators and representatives as well as the executive branch. Many have separate political-action committees with well-financed budgets. They place their views on the political agenda by

■ testifying at congressional hearings,

■ contacting government officials directly,

■ providing officials with research information,

■ sending letters to their own membership,

■ trying to influence the press to present their point of view,

■ suggesting and supporting legislation,

■ hiring lobbyists,

■ giving senators and representatives feedback from their constituents,

■ making contributions through PACs to campaign committees,

■ taking congresspersons on trips or to dinner,

■ endorsing candidates, and

■ working on political campaigns.

All these groups and techniques have the potential of cooperating with the legislative process because they do help inform office holders. They also provide elected officials with a viable strategy and a base of support. These groups also have the expertise to give elected officials an additional slant to a problem. Unlike constituents who have hidden agendas, special-interest groups place their goals on the table, up front.

Lobbyists

Lobbyists are the primary instruments for boosting a special-interest group’s goals with policy makers. The term lobbyist describes people who literally wait in the lobbies of legislative bodies to meet senators and representatives as they go to and from the halls of Congress. Manuals have been published for lobbyists outlining the best ways for them to be successful. Some of the techniques include

■ knowing as much as you can about the political situation and the people involved,

■ understanding the goals of the group and determining who you want to see,

■ being truthful in the way you deal with people,

■ working closely with the interest group that hired you,

■ keeping the people you are trying to convince in your corner by telling them of the support they will receive if they agree to the position of the group, and

■ following up on all meetings, making sure the results you want do not change.

Recently, the image of lobbyists has taken a blow because they often have attracted negative publicity. Former government officials who become lobbyists have been criticized because they can take unfair advantage of contacts they developed when they were in office. An additional accusation has been made against government appointees who were former lobbyists but still maintain a relationship with the special-interest group they worked for before getting the position. In 2006, lobbyist Jack Abramoff was convicted of illegal lobbying practices. As a result, Congress became embroiled in a scandal that revealed what many called a “culture of corruption.”

On the other hand, lobbyists also play a positive role as specialists. When tax reform was being considered in the 1990s, lobbyists provided expertise to the congressional committees considering the bills. Sometimes lobbyist coalitions are formed when extremely important and far-reaching legislation, such as health-care reform, is under consideration. Lobbyists may also take legal action on behalf of an interest group.

Lobbyists may also provide ratings of officials. Groups such as Americans for Democratic Action and the American Conservative Union give annual ratings based on their political ideologies. Lobbyists and special-interest groups also use the media to push their viewpoint. During the 1970s energy crisis, lobbyists for Mobil Oil Corporation ran ads that resembled editorial opinion columns, explaining the company’s point of view.

Political Action Committees (PACs)

When an interest group gets involved directly in the political process, it forms separate political action committees. PACs raise money from the special-interest group’s constituents and make contributions to political campaigns on behalf of the special interest. The amount of money contributed over the last few elections has been staggering. PACs such as the National Rifle Association, labor’s “Vote Cope,” the American Bankers Association (BANKPAC), the PAC of the National Automobile Dealers Association, Black Political Action Committees (BlackPAC), and Council for a Strong National Defense have made major contributions to political campaigns and have had a tremendous impact on local and national elections.

The amount of PAC contributions to congressional campaigns skyrocketed from 1981 to 2016. From 1981 to 1982, $83.7 million was contributed to candidates for the House and Senate, as compared with over $285 million contributed to congressional candidates in 2011–2016.

Top 10 PAC Contributors to Candidates, 2015–2016 |

||||||

Rank |

Organization |

Total Contributions |

To Democrats & Liberals |

To Republicans & Conservatives |

Percent to Democrats & Liberals |

Percent to Republicans & Conservatives |

1 |

Fahr LLC |

$66,860,491 |

$66,610,491 |

$0 |

100% |

0% |

2 |

Renaissance Technologies |

$50,368,646 |

$26,150,646 |

$22,972,000 |

53% |

47% |

3 |

Paloma Partners |

$38,693,300 |

$38,620,000 |

$3,300 |

100% |

0% |

4 |

Newsweb Corp |

$34,303,441 |

$34,298,041 |

$0 |

100% |

0% |

5 |

Las Vegas Sands |

$26,323,571 |

$43,341 |

$25,799,530 |

0% |

100% |

6 |

Elliott Management |

$24,580,672 |

$37,700 |

$24,541,972 |

0% |

100% |

7 |

Carpenters & Joiners Union |

$23,720,563 |

$23,278,997 |

$436,816 |

98% |

2% |

8 |

National Education Assn |

$23,299,929 |

$21,185,259 |

$366,570 |

98% |

2% |

9 |

Soros Fund Management |

$23,251,198 |

$21,670,483 |

$1,037,215 |

95% |

5% |

10 |

Priorities USA/Priorities USA Action |

$23,233,239 |

$21,060,341 |

$0 |

100% |

0% |

Source: Open Secret

The Difference Between Lobbyists, PACs, Super PACs (Independent Expenditure Committees), 527 Super PACs, and Social Welfare Organizations: 501(c)4 Groups

There is confusion regarding the differences between lobbyists, political action committees (PACs), Super PACs (Independent Expenditure Committees), and Social Welfare organizations also known as 501(c)4 groups:

■ Lobbyists: As previously described, lobbyists represent special-interest groups. They provide information to legislators and advocate their group’s positions. Lobbyists do not contribute money to candidates or office holders. Congressional law dictates how much money a lobbyist can spend when meeting with a legislator.

■ Political Action Committees can be formed by special-interest groups, elected officials, and candidates running for office. PACs formed by special-interest groups can raise money, contribute money to candidates, and spend money advocating their positions. PACs formed by elected officials and candidates running for office can raise money and spend money on advancing their own campaigns, or they can contribute money to other candidates. An example of this type of PAC was “Ready for Hillary,” the political action committee that was formed to encourage Hillary Clinton to run for president in 2016.

■ Super PACs, also known as Independent Expenditure Committees, are regulated by the Federal Election Commission and are supposed to act independently from any candidate or campaign. Independent Expenditure Committees cannot contribute directly to any campaign. They raise money for the purpose of supporting a position on specific issues through political advertisements. The Club for Growth is an independent committee that supports candidates who pledge that they would not vote to raise taxes.

■ 527 Super PACs: Also, independent expenditure committees, these PACs can create independent expenditure accounts that can accept donations without limits from individuals, corporations, labor unions, and other political action committees (thanks to the decision made by the U.S. Supreme Court in the Citizens United case); 527 groups have proliferated and play a significant role in congressional and presidential elections. Examples of 527 groups are Priorities USA (supporting Democratic candidates), American Crossroads, and Americans for Prosperity (supporting Republican candidates). By law, they cannot coordinate their spending with the candidates they support.

■ Social Welfare Organizations also known as 501(c)4 groups: These Super PACs are recognized by the Internal Revenue Service as “Tax Exempt Social Welfare Organizations” formed for the purpose of improving the social welfare of society. There are no limits on how much money they can raise. They can spend money on political advertising that supports their goals, as long as that political activity is not the sole purpose of the group. They differ from 527 groups because they do not have to disclose publicly the names of their contributors. Crossroads GPS is an example of a 501(c)4 group. Such groups have been criticized because of the anonymity of their donors. They have also played a major role in congressional and presidential elections.

The Success or Failure of Special-Interest Groups Depends on Public Support

In order for an interest group to succeed, not only must there be public awareness of the group’s position, but legislators must also accept the bill of goods presented to them. There is no doubt the National Rifle Association’s membership consists of a small percentage of the American public. Yet because of its image—for example, the “We are the NRA” commercials and its advocacy of the constitutional right to bear arms—the public is certainly aware of its stand, and polls indicate that many people support its position.

The National Rifle Association is a good example of how a special-interest group successfully influences public policy. From 1994 to 2012, the NRA’s political influence has been felt by both parties. In 1994, they successfully campaigned against Democrats who voted for the assault weapons ban, a key to the Republicans taking over Congress. After the tragic mass shooting of elementary school children and teachers at Sandy Hook Elementary school in 2012, public opinion shifted in favor of gun-control legislation. Universal background checks, penalties for gun trafficking, regulation of the number of magazine clips, and a new assault weapons ban were part of the legislative agenda. The NRA opposed these measures, citing Second Amendment concerns. Ultimately, Congress failed to approve any new gun-control measures.

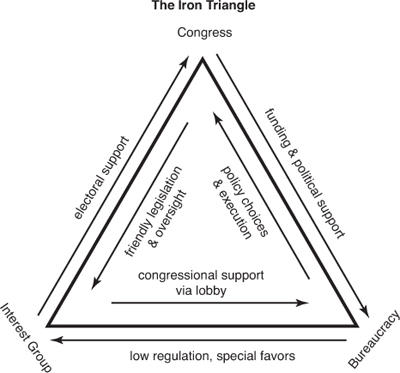

There is a symbiotic relationship among special-interest groups, Congress, and bureaucracies—earlier referred to as the iron triangle, and also called issued networks. The iron-triangle network is a pattern of relationships between an agency in the executive branch, Congress, and special-interest groups lobbying that agency.

Popular vs. Electoral votes

Once the candidate is nominated, the outcome of the election is generally determined by whoever receives the most electoral votes. The potential exists for a third-party candidate drawing enough votes to throw the election into the House of Representatives. When Ross Perot received almost 20 percent of the popular vote in 1992 and established his own political party, many political scientists predicted that in a future presidential election no candidate would receive a majority of the electoral votes. Two factors contribute to this prediction. First, in all but two states the rules of the Electoral College system dictate that the winner takes all the electoral votes of a state even if one candidate wins 51 percent of the vote and the losing candidate gets 49 percent. Second, the allocation of electoral votes does not always reflect true population and voter patterns.

On five occasions in American history, presidential candidates have lost the election even though they received the most popular votes. In 1824 Andrew Jackson received a plurality of popular votes and electoral votes, over 40 percent of the popular votes to 31 percent of the vote obtained by John Quincy Adams. Yet, Jackson did not receive a majority of the electoral votes; Adams received a majority of the votes from the House and was elected president. In 1876 Republican Rutherford B. Hayes lost the popular vote by a little more than 275,000 votes. Called the “stolen election” by historians, Hayes received an electoral majority after an electoral commission was set up by Congress to investigate electoral irregularities in Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Oregon. The commission voted on party lines, and Hayes was officially elected president. In 1888 Grover Cleveland won the popular vote but lost the electoral majority to Benjamin Harrison. In the 2000 election, Vice President Al Gore received more popular votes than George W. Bush. Bush, however, won the majority of the electoral votes and became our 43rd president. If third-party candidate Ralph Nader had not run, Gore would have won enough electoral votes to have won the election.

More Americans voted for Hillary Clinton than for any other losing presidential candidate in U.S. history. The Democrat received more votes than Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump—almost 2.9 million votes, with 65,844,954 (48.2 percent) to his 62,979,879 (46.1 percent), according to revised and certified final election results from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Clinton’s 2.1 percent margin ranks third among defeated candidates, according to statistics from the U.S. Elections Atlas. However, President Trump won the Electoral College vote 304–227, winning three key battleground states, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan by slim margins totaling fewer than 70,000 votes.

Even though this has occurred only five times, there have been extremely close elections, such as the 1960 election between Kennedy and Nixon and the 1976 election between Carter and Ford, where a small voting shift in one state could have changed the outcome of the election. There is also a potential constitutional problem if a designated presidential elector decides not to vote for the candidate he was committed to support—a faithless elector. This has happened on ten occasions without having an impact on the outcome. In 2016, there were seven faithless electors, two defecting from Trump and five defecting from Clinton, an all-time record. That is why the total number of electoral votes received by Trump and Clinton (531) does not add up to the maximum total of 538 electoral votes. The third anomaly of the system could take place if the House and Senate must determine the outcome of the election. The Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution outlines this procedure, and even though it has happened only once, strong third-party candidates make this a distinct possibility in the future.

Two proposed constitutional amendments have been offered to make the system fairer. The first would create a proportional system so that a candidate gets the proportional number of electoral votes based on the size of the popular vote received in the state. In 2011, individual states such as Pennsylvania considered passing legislation that would split their electoral votes proportionally in the 2012 election. A second plan offered would simply abolish the Electoral College and allow the election to be determined by the popular vote with perhaps a 40 percent minimum margin established: any multiparty race resulting in a victor who receives less than 40 percent would require a run-off. Another way to bypass the constitutional amendment route is for state legislatures to pass laws that mandate their electors to vote for the winner of the countrywide popular vote even if the elector’s state voted for a different candidate. The National Popular Vote bill would guarantee the presidency to the candidate who receives the most popular votes in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. It has been enacted into law in the District of Columbia and 15 states, with a total of 196 electoral votes. For this bill to succeed, enough states to carry the total another 74 electoral votes have to join the effort. Every state that has signed on is a “blue” state, and since there are not enough Democratic states to get over the 270 electoral votes threshold, some of the “red” states would also need to sign on.

The Invisible Primary

The time it takes between a candidate’s announcement that he or she is running and the actual start of the party’s convention, it could easily be two years from beginning to end. Add to that the campaign for president, and an additional three to four months are tacked on.

The “invisible primary,” the period between a candidate’s announcement that he or she is running for president and the day the first primary votes are cast, will heavily influence the outcome of the primary season. After the candidate declares, he or she starts building an organization, actively seeking funds—the current start-up fee for presidential races has been estimated at $100 million—and developing an overall strategy to win the nomination. Before the first primary or caucus, the candidate vies for endorsements from party leaders and attempts to raise the public’s interest by visiting key states with early primaries, such as Iowa and New Hampshire. Debates are held among the candidates, and political ads are shown in the early primary states. Since 1976, when little-known Georgia governor Jimmy Carter threw his hat in the ring, the invisible primary has created a perceived front-runner. Front-runner status during the invisible primary has been defined as the candidate who raised the most money. This pattern was broken in 2004, when Vermont governor Howard Dean raised more money than any other Democrat, establishing a record for the amount. Dean’s candidacy also pioneered using the Internet to raise funds. However, after Dean lost the Iowa caucus, his candidacy imploded. In the election of 2008, Hillary Clinton narrowly led Barack Obama in fundraising prior to the Iowa caucus. Republican Rudy Giuliani led the Republican field, with the eventual nominee John McCain lagging behind in fourth place. The Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary changed the dynamics of the race. Both Obama and McCain captured their party’s nomination, increasing their fundraising as the campaign progressed. The Republican field in 2012 held a series of candidate debates prior to the Iowa caucus and the New Hampshire primary. Even though former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney had a fund-raising advantage and was perceived as the best candidate to defeat President Obama, he suffered a series of setbacks as one candidate after another gained front-runner status. Romney ultimately surged ahead during the primaries.

The 2016 invisible primary broke past rules. Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton was expected to coast to the nomination with only minimal opposition. However, Senator Bernie Sanders, a Vermont independent, enrolled as a Democrat and waged a campaign that lasted until June 2016. He became the populist alternative to the establishment candidacy of Secretary Clinton and raised close to $230 million.

The Republican contest was also unique. Seventeen candidates entered the race to compete against of the outsider Donald Trump. After a series of Republican debates prior to the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary, Trump emerged as the front-runner. After narrowly losing in Iowa and winning decisively in New Hampshire, Trump remained the front-runner throughout the Republican primaries.

Primaries and Caucuses

The second stage of the campaign is the primary season. By the time the first caucus in Iowa and the first primary in New Hampshire are held in January, the campaign for the party’s nomination is well under way—some 10 months before election day. By the time these early primary votes are completed, many candidates have dropped out of the race. Prior to 2004, there was a break between the Iowa and New Hampshire votes and other primaries. But in 2004, the Democrats created a primary calendar characterized as “front-loading,” because primaries are held each week. This is the third phase of the campaign. And in February and March several key primaries are held on what has been called “Super Tuesday.” After Super Tuesday, one candidate usually has enough pledged delegates that he or she becomes the presumptive nominee. This did not happen in 2008, as the Democratic candidates fought until the last primary was completed. In 2012, Governor Romney was able to defeat the rest of the Republican field during the primary season and wrapped up the nomination shortly after Super Tuesday. But his image was damaged during the primary campaign as he was attacked not only by his Republican opponents but also by the incumbent, President Obama.

In 2016, Trump became the presumptive nominee in May, after the Indiana primary, first by eliminating most of his opponents after Super Tuesday, capturing a majority of the delegates needed to give him a clear path to the nomination.

Hillary Clinton did not clinch the nomination until the last primary in June 2016. Even though she won a majority of the popular votes in the primary states, because the Democratic primary delegates were awarded proportionally, her opponent remained in the race until the end of the process. Sanders conceded when he saw that the combination of primary delegates and superdelegates would guarantee Secretary Clinton the nomination. In 2020, the Democratic National Committee agreed to allow Iowa to make changes in its caucus to increase voter participation.

Primaries

Without a doubt, the presidential primary has become the decisive way a candidate gains delegate support. It has taken on such importance that key primary states such as New York and California have moved their primary dates to be earlier so that their primaries take on much greater importance. Today, 30 states have presidential primaries. The others use caucuses or party conventions. Presidential primaries can be binding or nonbinding. They can ask the voter to express a preference for a presidential candidate or for delegates who are pledged to support a candidate at the convention. Primaries are used in many ways:

■ Closed primary—only registered party voters can vote. Florida has a closed primary.

■ Open primary—registered voters from either party can cross over and vote in the other party’s primary. New Hampshire has an open primary.

■ Proportional primary representation, where delegates are apportioned based on the percentage of the vote the candidate received in the primary election.

■ Winner-takes-all primary, where, as in the general election, the candidate receiving a plurality receives all the delegates. The Republicans use this method in California. Democratic rules have banned the use of this system since 1976.

■ Non-preferential primary, where voters choose delegates who are not bound to vote for the winner of the primary.

■ A primary in which all the voters, including cross-over voters from other political parties, can express a preference but do not actually select delegates to the convention.

■ A dual primary, where presidential candidates are selected, and a separate slate of delegates is also voted on. New Hampshire uses this type of primary.

Pre-Convention Strategy