When the a6000 was introduced, Sony boasted that the camera had the fastest autofocus system in the world. That’s saying a lot, because, as you’ll learn in this chapter, mirrorless cameras have one serious hurdle to overcome on the way to world-class AF speed. Until recently, such cameras have depended on a particularly slow method of autofocus, called contrast detection, based solely on what the sensor sees. The much speedier phase detection system was limited to digital SLR cameras (and SLR-like cameras such as the Sony Alpha SLT lineup), because they could use dedicated AF sensors that operated much more quickly and precisely. I’m going to explain both types of autofocus systems in this chapter, and show how Sony was able to combine them into a single hybrid AF system that is, indeed, very, very fast.

One of the most useful and powerful features of modern digital cameras is their ability to lock in sharp focus faster than the blink of an eye. Sometimes. Although autofocus has been with us for more than 20 years, it’s still not exactly perfect in every respect. Camera manufacturers are giving us faster and more precise autofocus systems, like the full-time autofocus possible with mirrorless technology. Granted, the sheer number of options can confuse even the most advanced photographers.

One key problem with autofocus is, as I’ve already mentioned, the speed; another is that the camera doesn’t really know, for certain, what subject you want to be in sharp focus. It may select an object and lock in focus with lightning speed—even though it’s not the center of interest in your photograph. Or, the camera may lock focus too soon, or too late. This chapter will help you choose the options available with your Sony a6000 to help the camera understand what you want to focus on, when, and maybe even why.

Learning to use the Sony a6000’s autofocus system is easy, but you do need to fully understand how the system works to get the most benefit from it. Once you’re comfortable with autofocus, you’ll know when it’s appropriate to use the manual focus option, too. The important thing to remember is that focus isn’t absolute. For example, some things that appear to be in sharp focus at a given viewing size and distance might not be in focus at a larger size and/or closer distance. In addition, the goal of optimum focus isn’t always to make things look sharp. For some types of subjects, not all of an image need be sharp. Controlling exactly what is sharp and what is not is part of your creative palette. Use of depth-of-field characteristics to throw part of an image out of focus while other parts are sharply focused is one of the most valuable tools available to a photographer. But selective focus works only when the desired areas of an image are in focus properly. For the digital camera photographer, correct focus can be one of the trickiest parts of the technical and creative process.

As I said in the introduction to this chapter, there are two major focusing methods used by modern digital cameras: Phase detection, used by Sony Alpha SLT models and some advanced mirrorless models like the a6000 that incorporate the technology into their sensors, and contrast detection, which is the primary focusing method employed by all mirrorless models until very recently.

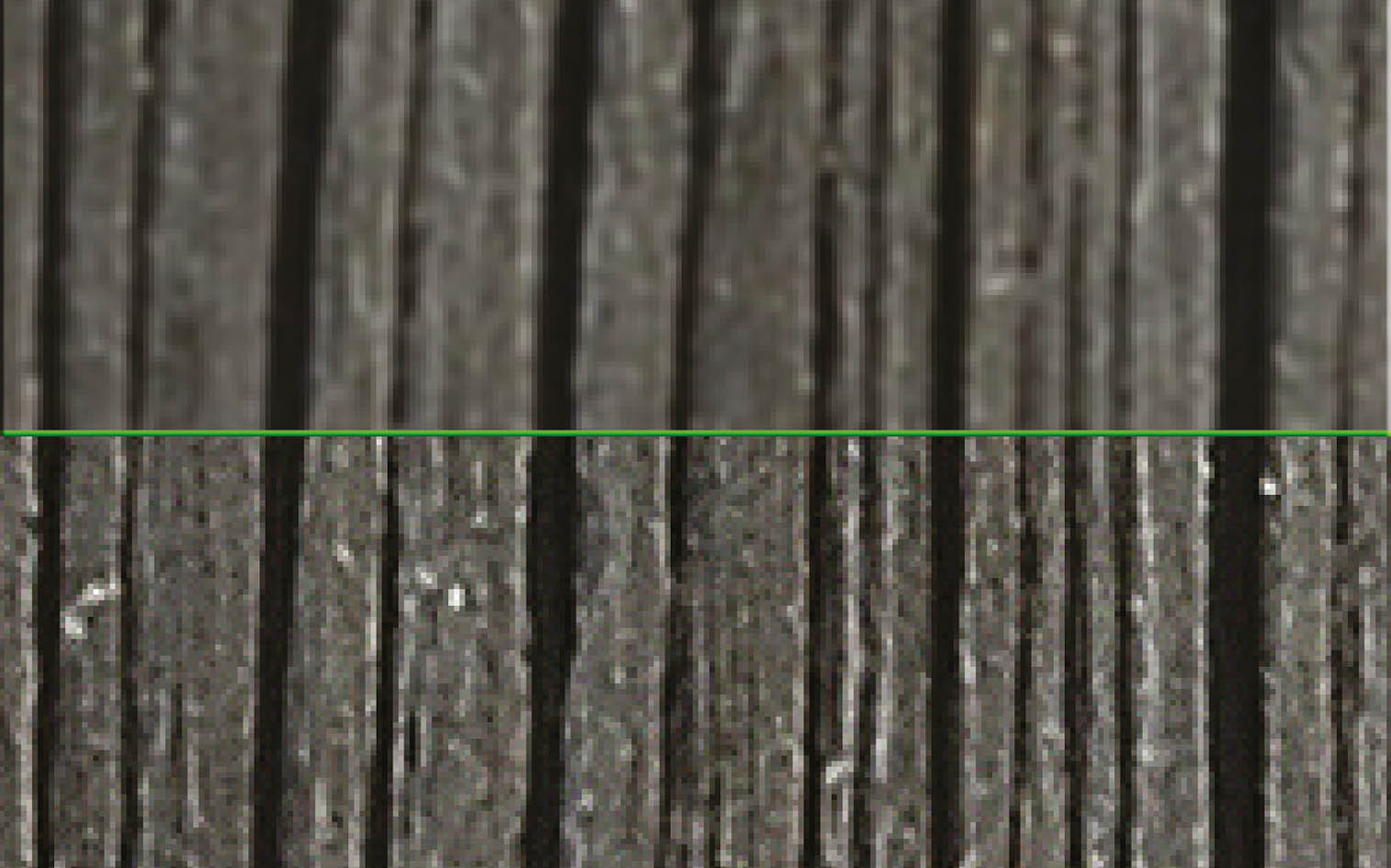

Contrast detection relies on examining the image formed on the sensor, and its operation is illustrated, if over-simplified, in Figure 6.1. At top in the figure, the transitions between the edges of the vertical wood grain grooves are soft and blurred because of the low contrast between them. The traditional contrast detection autofocus system looks only for contrast between edges, and those edges can run in any direction. At the bottom of the figure, the image has been brought into sharp focus, and the edges have much more contrast; the transitions are sharp and clear. Although this example is a bit exaggerated so you can see the results on the printed page, it’s easy to understand that when maximum contrast in a subject is achieved using contrast detection, it can be deemed to be in sharp focus.

Figure 6.1 Using the contrast detection method of autofocus, a camera can evaluate the increase in contrast in the edges of subjects, starting with a blurry image (top) and producing a sharp, contrasty image (bottom).

Contrast detection works best with static subjects, because it is inherently slower and not well-suited for tracking moving objects. Contrast detection works less well in dim light, because its accuracy is limited by its ability to detect variations in brightness and contrast. You’ll find that contrast detection works better with faster lenses, too, because larger lens openings admit more light that can be used by the sensor to measure contrast.

Phase detection is an alternative focusing method available with the a6000’s hybrid AF system and also when you attach the optional LA-EA2 or LA-EA4 A-mount lens adapters, which each have their own built-in phase detection autofocus systems. Phase detection is a crucial part of the a6000’s advanced hybrid AF system, which combines contrast detection with phase detection to give us, potentially, the best of both worlds.

With phase detection, each autofocus sampling area (either a separate sensor with dSLRs and SLT models or embedded pixels in the case of cameras like the a6000) is divided into two halves. The two halves are compared, much like (actually, exactly like) a two-window rangefinder used in surveying, weaponry, and non-SLR cameras like the venerable Leica M film models. The contrast between the two images changes as focus is moved in or out, until sharp focus is achieved when the images are “in phase,” or lined up.

You can visualize how phase detection autofocus works if you look at Figure 6.2. (This is a greatly simplified view just for illustration purposes.) In Figure 6.2 (left), a typical horizontally oriented focus sensor is looking at a series of parallel vertical lines in a weathered piece of wood. The lines are broken into two halves by the sensor’s rangefinder prism, and you can see that they don’t line up exactly; the image is slightly out of focus. The rangefinder approach of phase detection tells the camera exactly how much out of focus the image is, and in which direction (focus is too near, or too far), thanks to the amount and direction of the displacement of the split image. The camera can snap the image into sharp focus and line up the vertical lines, as shown in Figure 6.2, right, in much the same way that rangefinder cameras align two parts of an image to achieve sharp focus.

As with any rangefinder-like function, accuracy is better when the “base length” between the two images is larger, so the two split images have greater separation. (Think back to your high-school trigonometry; you could calculate a distance more accurately when the separation between the two points where the angles were measured was greater.) Autofocus is always performed at the lens’s largest f/stop, regardless of what aperture will be used to take the actual picture. For that reason, phase detection autofocus is more accurate with lenses having a larger (wider) maximum aperture, than with those with a smaller maximum f/stop, and may not work at all when the maximum f/stop is smaller than f/5.6. Obviously, the “opposite” edges of the lens opening are farther apart with a lens having an f/2.8 maximum aperture than with one that has a smaller, f/5.6 maximum f/stop, and the base line is much longer. The camera is able to perform these comparisons and then move the lens elements directly to the point of correct focus very quickly, in milliseconds.

Figure 6.2 When an image is out of focus, the split lines don’t align precisely (left); using phase detection, a camera can align the features of the image and achieve sharp focus quickly (right).

Because of the speed advantages of phase detection, makers of mirrorless cameras are adding on-chip phase detect points to their sensors. Sony, for example, uses a 25-area contrast detection system for autofocus with several of its recent cameras, but includes up to 179 phase detect pixels embedded in the a6000’s sensor, covering 92 percent of the frame. Figure 6.3 shows the location of the two types of focus zones (they don’t appear like this on your camera’s LCD monitor or viewfinder). This hybrid system is more adept at tracking moving subjects.

Although the phase detection approach to focusing is generally considered state-of-the art because of its speed and efficiency, the contrast detection approach has certain advantages of its own, which is why Sony included it in its hybrid system, rather than switching to phase detection completely.

Figure 6.3 The a6000 features 25 contrast detect zones (green brackets) and 179 phase detect zones (red crosses).

There are restrictions you need to keep in mind when using the a6000’s hybrid AF system:

Now that you understand the fundamental principles of how the a6000 achieves focus, let’s discuss the practical application of these principles to your everyday picture-taking activities by setting the various modes and options for use of the autofocus system. We’ll also discuss the use of manual focus, and when that method might be preferable to autofocus.

As you’ve come to appreciate by now, the a6000 offers many options for your photography. Focus is no exception. Of course, as with other aspects of this camera, you can set the shooting mode to either Auto or a SCN mode such as Sports Action, and the camera will do just fine in most situations, using its default settings for autofocus. But, if you want more creative control, the choices are there for you to make. In fact, even in the fully automatic modes, you always have the option of choosing manual focus. (If you select autofocus in those shooting modes, though, you have no further choices available; the autofocus method and Autofocus Area are set for you.)

So, no matter what shooting mode you’re using, your first choice is whether to use autofocus or manual focus. Yes, there’s also a Direct Manual Focus (DMF) option, discussed in Chapter 3, but that still provides autofocus, with the option of fine-tuning focus manually before taking the shot. Until quite recently, manual focus was the only choice available to photographers. That was the only option from the nineteenth century days of Daguerreotypes until about the 1980s, when autofocus started becoming available. Manual focus presents you with great flexibility along with the challenge of keeping the image in focus under what may be challenging conditions, such as rapid motion of the subject, darkness of the scene, and the like. Later in this chapter, I’ll cover manual focus as well as DMF. For now, I’ll assume you’re going to rely on the camera’s conventional AF mode.

The Sony a6000 has three basic AF modes: AF-S (Single-shot autofocus) and AF-C (Continuous autofocus), as well as Automatic AF (AF-A), which switches between the two other modes as required. Once you have decided on which of these to use, you also need to tell the camera how to set the AF frame. In other words, after you tell the camera how to autofocus, you also have to tell it where to direct its focusing attention. I’ll explain all of these points in more detail later in this section.

MANUAL FOCUS

When you select manual focus (MF) in the Focus Mode entry in the Camera Settings 3 menu, the a6000 lets you set the focus yourself by turning the focus ring on the lens. There are some advantages and disadvantages to this approach. While your batteries will last slightly longer in manual focus mode, it will take you longer to focus the camera for each photo. And unlike older 35mm film SLRs, digital cameras’ viewfinders and LCDs are not designed for optimum manual focus. Pick up any advanced film camera and you’ll see a big, bright viewfinder with a focusing screen that’s a joy to focus on manually. So, although manual focus is still an option for you to consider in certain circumstances, it’s not as easy to use as it once was. I recommend trying the various AF options first, and switching to manual focus only if AF is not working for you. And then be sure to take advantage of the focus peaking feature and the automatic frame enlargement (MF Assist), explained in Chapter 3, which can make it easier to determine when the focus is precisely on the most important subject element. And remember, if you use the DMF mode, you can fine-tune the focus after the AF system has finished its work.

Although some cameras added autofocus capabilities in the 1980s, back in the days of film cameras, prior to that focusing was always done manually. Honest. Even though 35mm SLR cameras’ viewfinders were bigger and brighter than they are today and usually offered a split-image or other focusing aid, some photographers still bought special focusing screens and magnifiers, and other gadgets were often used to help the photographer achieve correct focus. Imagine what it must have been like to focus manually under demanding, fast-moving conditions such as sports photography.

Focusing was problematic because our eyes and brains have poor memory for correct focus, which is why your eye doctor must shift back and forth between sets of lenses and ask “Does that look sharper or was it sharper before?” in determining your correct prescription. Similarly, manual focusing involves jogging the focus ring back and forth as you go from almost in focus, to sharp focus, to almost focused again. The little clockwise and counterclockwise arcs decrease in size until you’ve zeroed in on the point of correct focus. What you’re looking for is the image with the most contrast between the edges of elements in the image.

The Sony a6000’s system can assess sharpness quickly, and it’s also able to remember the progression perfectly, making the entire process fast and precise. Unfortunately, even this high-tech system doesn’t know with any certainty which object should be in sharpest focus. Is it the closest object? The subject in the center of the frame? Something lurking behind the closest subject? A person standing over at the side of the picture? Many of the techniques for using autofocus effectively involve telling the a6000 exactly what it should be focusing on.

But there are other factors in play, as well. You know that increased depth-of-field brings more of your subject into focus. But more depth-of-field also makes autofocusing (or manual focusing) more difficult because the contrast is lower between objects at different distances. So, autofocus with a 300mm lens (or zoom setting) may be easier than at a 16mm focal length (or zoom setting) because the longer lens has less apparent depth-of-field. By the same token, a lens with a maximum aperture of f/1.8 will be easier to autofocus (or manually focus) than one of the same focal length with an f/4 maximum aperture, because the f/4 lens has more depth-of-field and a dimmer view. It’s also important to note that lenses with a maximum aperture smaller than f/5.6 would give your Sony Alpha’s autofocus system fits, because the smaller opening (aperture) would allow less light to enter or to reach the autofocus sensor.

To make things even more complicated, many subjects aren’t polite enough to remain still. They move around in the frame, so that even if the a6000’s lens is sharply focused on your main subject, the subject may change position and require refocusing. An intervening subject may pop into the frame and pass between you and the subject you meant to photograph. You (or the a6000) have to decide whether to focus on this new subject, or to remain focused on the original subject. Finally, there are some kinds of subjects that are difficult to bring into sharp focus because they lack enough contrast to allow the a6000’s AF system (or our eyes) to lock in. Blank walls, a clear blue sky, or other low-contrast subject matter may make focusing difficult even with the Hybrid AF system.

If you find all these focus factors confusing, you’re on the right track. Focus is, in fact, measured using something called a circle of confusion. An ideal image consists of zillions of tiny little points, which, like all points, theoretically have no height or width. There is perfect contrast between the point and its surroundings. You can think of each point as a pinpoint of light in a darkened room. When a given point is out of focus, its edges decrease in contrast and it changes from a perfect point to a tiny disc with blurry edges (remember, blur is the lack of contrast between boundaries in an image). (See Figure 6.4.)

If this blurry disc—the circle of confusion—is small enough, our eye still perceives it as a point. It’s only when the disc grows large enough that we can see it as a blur rather than as a sharp point that a given point is viewed as being out of focus. You can see, then, that enlarging an image, either by displaying it larger on your computer monitor or by making a large print, also magnifies the size of each circle of confusion. Moving closer to the image does the same thing. So, parts of an image that may look perfectly sharp in a 5 × 7-inch print viewed at arm’s length, might appear blurry when blown up to 11 × 14 inches and examined at the same distance. Take a few steps back, however, and the image may look sharp again.

Figure 6.4 When a pinpoint of light (left) goes out of focus, its blurry edges form a circle of confusion (center and right).

To a lesser extent, the viewer also affects the apparent size of these circles of confusion. Some people see details better at a given distance and may perceive smaller circles of confusion than someone standing next to them. For the most part, however, such differences are small. Truly blurry images will look blurry to just about everyone under the same conditions.

Technically, there is just one plane within your picture area, parallel to the back of the camera (actually the sensor) that is in sharp focus. That’s the plane in which the points of the image are rendered as precise points. At every other plane in front of or behind the focus plane, the points show up as discs that range from slightly blurry to extremely blurry. In practice, the discs in many of these planes will still be so small that we see them as points, and that’s where we get depth-of-field: the range of planes that includes discs that we perceive as points rather than blurred splotches. The size of this range increases as the aperture is reduced in size and is allocated roughly one-third in front of the plane of sharpest focus, and two-thirds behind it. (See Figure 6.5.)

As I noted earlier, manual focus is not as straightforward as with an older manual focus 35mm SLR, equipped with a focusing screen optimized for this purpose and a readily visible focusing aid. But Sony’s designers have done a good job of letting you exercise your initiative in the focusing realm, with features that make it easy to determine whether you have achieved precise focus. It’s worth becoming familiar with the techniques for those occasions when it makes sense to take control in this area.

Note

Nearly all zoom lenses are equipped with a zoom ring as well as a manual focus ring. When you use the 16-50mm f/3.5–5.6 PZ OSS lens however, there’s only one ring. It’s used for zooming when autofocus is active, but when you use manual focus in MF or DMF mode, this ring controls focus.

Figure 6.5 The focused plane (the nose of the train) is sharp but the area in front of that (the lettering on its side) and behind it (the background) are blurred because the depth-of-field (the range of acceptably sharp focus) is shallow in this image.

Here are the basic steps for quick and convenient setting of focus:

The enlargement lasts two seconds before the display returns to normal; you can increase that with the MF Assist Time menu item. In situations where you want to use manual focus without enlargement of the preview image, you can turn this feature off in the Custom Settings menu, using the MF Assist item.

This method gives you the benefit of autofocus but gives you the chance to change the exact point of focus, to a person’s eyes instead of the tip of the nose, for example. This option is useful in particularly critical focusing situations, when the precise focus is essential, as in extremely close focusing on a three-dimensional subject. Because depth-of-field is very shallow in such work, you’ll definitely want to focus on the most important subject element, such as the pistil or stamen inside a large blossom. This will ensure that it will be the sharpest part of the image. DMF is also useful for precisely fine-tuning focus, as I did for Figure 6.6.

Figure 6.6 Direct Manual Focus lets you fine-tune autofocus.

Most serious photographers would not buy a camera if it could not provide manual focus, but autofocus is likely to be your choice in the great majority of shooting situations. Choosing the right AF mode and the way in which focus points are selected is your key to success. Using the wrong mode for a particular type of photography can lead to a series of pictures that are all sharply focused—on the wrong subject. When I first started shooting sports with an autofocus camera (back in the film camera days), I covered one baseball game alternating between shots of base runners and outfielders with pictures of a promising young pitcher, all from a position next to the third base dugout. The base runner and outfielder photos were great, because their backgrounds didn’t distract the autofocus mechanism. But all my photos of the pitcher had the focus tightly zeroed in on the fans in the stands behind him. Because I was shooting with film instead of a digital camera, I didn’t know about my gaffe until the film was developed. A simple change, such as locking in focus or focus zone manually, or even manually focusing, would have done the trick.

But autofocus isn’t some mindless beast out there snapping your pictures in and out of focus with no feedback from you. There are several settings you can modify that return a fair amount of control to you. Your first decision should be whether you set the autofocus mode to Single-shot or Continuous AF. Press the MENU button, go to the Camera Settings 2 menu, and navigate to the line for Focus Mode. Press the center button, then highlight your choice from the submenu, and press the center button again.

If you have set the a6000 for AF-S and Pre-AF (in the Custom Settings 3 menu), you may notice something that seems strange: the camera’s autofocus mechanism will begin seeking focus even before you touch the shutter release button. This is definitely not the norm with the vast majority of cameras. But the Sony a6000 is different in various ways, and this is one of them. No matter which AF mode is selected, the camera will continually alter its focus as it is aimed at various subjects, until you press the shutter release button halfway. At that point, the camera locks focus, in Single-shot AF mode.

Note

In this chapter, I’m assuming that you’re using P, A, S, or M mode where you have full control over the camera features. This is important because the a6000 will use only AF-S in Auto mode, in any scene mode except Sports Action, in Sweep Panorama, and whenever the Smile Shutter feature is active.

The difference between Single-shot AF and Continuous AF comes at the point the shutter release button is pressed halfway. In AF-S mode, focus is locked. By keeping the shutter button depressed halfway, you’ll find you can reframe the image by moving the camera to aim at another angle; the focus (and exposure) will not change. Maintain pressure on the shutter release button and focus remains locked even if you recompose or if the subject begins running toward the camera, for example.

When sharp focus is achieved in AF-S mode, a solid green circle will appear on the lower-left corner of the screen and you’ll hear a little beep. One or more green focus confirmation frames will also appear to indicate the area(s) of the scene that will be in sharpest focus. If for some reason the camera cannot achieve sharp focus, such as in a dark or low-contrast environment, the green circle will flash and you will not hear a focus-confirmation beep. However, unlike some cameras, which lock the shutter if focus cannot be achieved, the a6000 will let you take a shot even if it will be out of focus. I suppose the theory is that a slightly blurred photo is better than no photo at all in difficult situations.

For non-action photography, AF-S is usually your best choice, as it minimizes out-of-focus pictures (at the expense of spontaneity). Because of the small delay while the camera zeroes in on correct focus, you might experience slightly more shutter lag. This mode uses less battery power than Continuous AF.

Switch to this mode when photographing sports, young kids at play, and other fast-moving subjects. In this mode, as with Single-shot AF, the autofocus system is operating constantly even before you depress the shutter release button halfway. The camera can lock focus on a subject if it is not moving toward the camera or away from your shooting position; when it does, you’ll see a green circle surrounded by brackets. (There will be no beep.) But if the camera-to-subject distance begins changing, the camera instantly begins to adjust focus to keep it in sharp focus.

The camera begins using AF-S, and switches to AF-C if the subject begins moving.

So far, you have allowed the a6000 to choose which part of the scene will be in the sharpest focus using its focus detection points called AF Areas. However, you can also specify a single focus detection point that will be active. There are four basic AF Area options. (A fifth option is Face Detection, which I’ll discuss shortly.) Press the MENU button, navigate to the Focus Area item in the Camera Settings 3 menu, press the center button, and select one of the four options. Press the center button again to confirm.

Here is how the four AF Area options work:

Figure 6.7 In Zone mode, an array of nine areas appears, and you can move the zone to nine different locations on the screen. The a6000 selects one or more focus zones within that array.

When you initially select this AF Area mode, a small pair of focus brackets appears in the center of the screen along with four triangles pointing toward the four sides of the screen. (See Figure 6.9.) The triangles merely indicate that the AF Area can be moved in any direction.

Use the directional controls to move the orange brackets around the screen, which allows great versatility in the placement of the active focus detection point. Move the orange brackets until they cover the most important subject area and touch the shutter release button. The brackets will turn green and the camera will beep to confirm that focus has been set on the intended area.

Figure 6.8 In the Center AF Area mode, the camera displays the focus brackets in the center of the screen; the brackets turn green after focus has been set.

Figure 6.9 When the Flexible Spot AF Area mode is initially selected, the active focus detection point is delineated with orange brackets that turn green when focus is confirmed and locked; the arrows at each side of the screen indicate that you can move the brackets in any of the four directions.

As hinted already, the a6000 has one more trick up its sleeve for setting the AF Area. By default, Smile/Face Detection in the Camera Settings menu is on, enabling the a6000 to attempt to identify any human faces in the scene. If it finds one or more faces, the camera will surround each one (up to eight in all) with a white frame on the screen. (Later, I’ll discuss a feature that allows you to specify favorite faces that the camera should prioritize.) If it judges that autofocus is possible for one or more faces, it will turn the frames around those faces orange. When you press the shutter button halfway down to lock autofocus, the frames will turn green, confirming that they are in focus. The camera will also attempt to adjust exposure (including flash, if activated) as appropriate for the scene.

Face Detection is available only when you’re using AF and when the Metering mode are both set to Multi, the defaults. So, if the Face Detection option is grayed out on the Camera Settings menu, check those other settings to make sure they are in effect. Personally, I usually prefer to exercise my own control as to exactly where the camera should focus, but when shooting quick snaps during a party, Face Detection can be a useful feature. It’s also an ideal choice if you need to hand the camera to someone to photograph you and your family or friends at an outing in the park.

The next magic the a6000 can perform is called Lock-On AF. It’s designed to maintain focus on a specific subject as it moves around the scene that you’re shooting. Don’t confuse this feature with Continuous AF (AF-C), the mode you would use in action photography with a subject running toward you, for example. That feature is often called AF Tracking with other cameras and by many photographers. The a6000 offers that feature too, with AF-C mode autofocus.

The Lock-On AF function can change focus as a person approaches the camera, but it’s not intended for that purpose with a fast action subject. And this feature is far more versatile than Continuous AF mode. Once the camera knows what your preferred subject is, it can maintain focus as it moves around the image area, as a person might do while mingling with a large group of friends at a party.

Lock-On AF in the Camera Settings 5 menu. (You cannot do so when the camera is set for Handheld Twilight or Anti Motion Blur scene mode, or Sweep Panorama or manual focus.) When it’s on, a small white square appears in the center of the screen as in Figure 6.10, left. Move the position of the square with the directional controls until it covers your intended subject and press the center button. The small square now changes to a larger double square (as shown in Figure 6.10, right) that’s called the target frame. You have instructed the a6000 as to your preferred subject. If the camera is set to AF-C mode, the camera tracks a focus subject when the shutter button is pressed halfway.

Move the camera around to change your composition or wait until your targeted subject begins moving around. Note that the target frame will remain on your subject, confirming that it will be in the sharpest focus when you take a photo. Changes in lighting, lack of contrast with the background, extra small or extra large subjects, and anything moving very rapidly can confuse Lock-On AF, but it’s generally quite effective.

And there are a few other benefits with Lock-On AF when using the a6000 when Face Detection is also active. Let’s say you have designated the intended target as your friend Jack’s face. If Jack leaves the room while being tracked and then returns to the scene, Lock-On AF will remember it and focus on Jack again. Whenever a face is your target, the camera can continue tracking that person even if the face is not visible; it will then make the body the target for tracking. If you also activate the camera’s Smile Shutter feature (in the Camera Settings 5 menu) in addition to Face Detection, the a6000 will not only track the targeted face, but it will take a photo if your subject smiles.

And finally, the a6000 provides a face priority feature to instruct the camera to track a certain specific face in a scene where many faces are visible. Activate it in the Camera Settings 5 menu with the Smile/Face Detection entry. The camera will then make the face that you first target its priority subject; it will make that its favorite, tracking the person whenever she’s in the scene and continuing to track the person if she returns after leaving the scene for a while.

Figure 6.10 Left: Decide on the object the camera should track, center it, and press OK to instruct the a6000 as to your preferred target. Right: When Lock-On AF is active, the camera maintains focus on your preferred target, tracking it as it moves around the scene.

Here is a list of the a6000 autofocus features not yet mentioned, or not yet discussed in detail in this chapter, that you should keep in mind.

To register a face, point the camera at the person’s face, make sure it’s within the large square on the screen, and press the shutter release button. Do so for several faces. When you’re taking a photo of a scene that contains more than one registered face, the camera will prioritize faces based on which were the first to be registered in the process you used.

Take advantage of the Order Exchanging option of this menu item so the faces you consider the most important are prioritized. When you access it, the camera displays the registered faces with a number on each; the lower the number the higher the priority. You can now change the priority in which the faces will be recognized, from 1 (say your youngest child) to 8 (perhaps your cousin twice removed). You can also use the Delete or the Delete All options to delete one or more faces from the registry, such as your ex and former in-laws.

While this is not an autofocus feature per se, I’ll discuss it here because it works in conjunction with Face Detection. It’s intended for use when shooting portrait photos (JPEGs only) quickly in situations where you won’t have time to make a perfect composition. After it’s activated with the Auto Object Framing item in the Camera Settings 6 menu, the a6000 determines when you are taking a photo of a person. After you compose such a photo, the Auto Object Framing icon on the screen turns green if the processor decides that it will be able to crop the photo in order to provide an improved composition. (If it cannot do so, try a different composition and make sure the person is well lit from the front.)

While practicing with this feature, take the shot when the icon is green. After you do so a frame showing the trimmed area will be displayed on the screen so you can see what has been cropped to provide a better composition. The cropping will usually eliminate extraneous areas around the subject and it will be done so the eyes in the photo will be off-center. The camera saves both the original image (“poor” composition) and the cropped (better composition) JPEG to the memory card. (See Figure 6.11.)

Just as you suspected, Auto Object Framing is another feature that cannot be activated under certain conditions: in some scene modes and in Panorama mode, in Continuous drive mode or bracketing, when manual focus is used, when certain effects are active, when digital zoom is in use, when Auto HDR is on, and when RAW or RAW&JPEG capture is being used.

Although cropping discards millions of pixels, the camera’s processor ensures that the cropped image will be as large as the “poor” (original) image. That’s achieved by adding pixels to restore it to the full size, using Sony’s By Pixel Super Resolution Technology; this type of interpolation minimizes the loss of quality. Still, for the best results, it’s worth setting Quality to Fine when using Auto Portrait Framing.

Figure 6.11 I intentionally made a poor composition (left) to test the value of Sony’s Auto Object Framing technology. The processor cropped the photo for a better composition (right).

Like most cameras, the a6000 provides an autofocus lock (in AF-S mode), with light pressure on the shutter release button , the AEL button, or when you depress an AF Lock button that you define using Custom Settings 6 menu’s Custom Keys option, as described in Chapter 3. The most frequent use of this feature is when the camera struggles to focus on a desired subject; it works best when AF Area is set to Center. When the camera struggles, simply point the lens at an entirely different object that’s the same distance from the camera. Use AF Lock to maintain focus at the desired distance, recompose, and take the photo. Whether you used light pressure on the shutter release button or depressed the button, both focus and exposure will be locked for the area in sharpest focus.

You might also want to use this lock technique for off-center compositions. Start by centering your subject and depressing the shutter release button partway; the focus and exposure are now locked. While using this technique, you can move the camera to get a better composition, placing the subject far off-center, for example. Since you’re keeping both focus and exposure locked, neither aspect will change as you recompose. Both will be optimized for your intended subject.

You can also use this camera feature to expose for one part of a scene, such as a mid-tone like nearby grass, while focusing on another part of the scene, like a distant white statue in a park. (Both areas must be in the same light, as discussed in a moment.) Again, it works best when AF Area is set to Center. Simply follow these steps:

The technique discussed above should provide a photo with correct exposure and a sharply focused primary subject because you took the light meter reading from a mid-tone area (as discussed in Chapter 5) and set focus on the intended center of interest. When you try it, do remember the warning that the area you meter must be in the same light as the primary subject. In other words, do not meter a grassy area in dark shade when most of the scene, including the center of interest, is in an area lit by bright sunshine.