Perhaps the most common question asked of us by parents is whether or not we believe the ketogenic diet is likely to be helpful for their child. Quoting the odds is great, but because every child is different, is there a way to know who will respond and who will not? Most of the anti-convulsant medicines on the market now are initially used for partial (focal) seizures, and of course always in adults first. As most parents are no doubt aware, as time and familiarity with new drugs occurs, these medicines are used not only for generalized seizures (which involve the entire brain all at once) but in young children as well. Sometimes figuring this out takes years. What about the ketogenic diet, which has been used for nearly a century now? For whom does it work best? When should it be tried? Who is it unlikely to help? The answers to these questions are becoming clearer as the diet is being used more.

In general, the diet is used for children with intractable seizures, often occurring daily, that have failed at least two medications for seizure control. Does this mean the diet wouldn’t be helpful earlier? Definitely not, and we suspect the opposite. For more information about using the diet first-line, read Chapter 24.

When compared to many anticonvulsants, especially those of the older generation (e.g., phenobarbital, Dilantin®, Depakote®, Tegretol®), the diet, in our opinion, has a better side-effect profile. When compared to many of the newer drugs, the diet is certainly better established with more data, especially in kids, to support its use. In our experience as well, we do not see the same potential side effects. So why isn’t the diet used first? There is no doubt that it is easier to take a pill than to restrict calories, carbohydrates, and fluids and change the entire family’s lifestyle with the ketogenic diet. However, there is nothing worse than seeing a child for a second opinion that has failed over 10 medications over many years who was not offered the ketogenic diet as an option. The diet should be offered earlier in the course of epilepsy in children, and many epilepsy centers agree. The same feeling is the subject of research into an earlier use of other therapies such as surgery and the vagus nerve stimulator.

Sandra was a 5-year-old girl with new onset of frequent complex partial seizures. Her brother Charlie was on the ketogenic diet for 4 years, having come to see us after years of difficult-to-control seizures that didn’t respond to any medications. Charlie had a dramatic response to the diet and was taken off the diet mostly due to a lack of seizures than any other reason. Due to Charlie’s success, the family wanted to try the diet before any other medications were tried. Although this was an unusual request, Sandra was started on the diet and did just as well as her brother. Because Sandra’s parents had lots of experience with the diet, it made the change in lifestyle much easier for Sandra to handle.

In general, we don’t know for sure. Parents often come to Johns Hopkins to be started on the diet after they see a video, television special, or newspaper article that highlights an amazing “miracle” responder to the ketogenic diet. These children start the diet, are seizure-free within 1–2 weeks (sometimes after the fast), and are medication-free within months. Although wonderful to take care of, these children are uncommon (probably about 10% of our patients on the diet). Based on our information from 1998, more than one-quarter of patients will have a 90% or greater reduction in seizures, but all seizure types appeared to be equally likely to respond. Younger age tended to do slightly better as well.

A few years ago, we looked at 3 years of ketogenic diet patients to see who the “super-responders” were. We found out the same thing as we did years ago: All seizure types, ages, weights, and severities of seizures of children were likely to be miracle responders. The only exceptions were children with just complex partial (focal) seizures, many of whom were possible surgery candidates but chose to try the diet first. This is not to say that many children with partial seizures don’t do well on the diet; many had 90% or greater seizure reductions and were able to lower medicines, but the diet is rarely a cure in this situation. In this situation, if the diet is tried and ineffective after 3 to 6 months, and surgery is an option, we would suggest surgery be looked into at an epilepsy center.

In this study, there were only a few children with Doose syndrome (myoclonic-astatic epilepsy). Our suspicion was that if we did this study again, now years later, this syndrome would turn out to be one in which children are likely to be super-responders. In fact, we often tell families of children in which this is a possible diagnosis that the response to the ketogenic diet is the best “test” for Doose syndrome we know. Keep reading for more information about Doose syndrome.

All that aside, we have our beliefs, based on very recent information, that certain neurologic conditions do extremely well on the diet. Some of this research is from our center, some from others, and some combined. This list is by no means complete but does influence when we decide to try the diet earlier with some patients. These conditions are the perhaps most important. (For more information, see Table 1 of the 2009 international ketogenic diet consensus paper.)

In 2002, we published our experience using the diet for infants with one of the most terrifying epilepsy disorders: infantile spasms (West syndrome). In this condition, infants around 6 months of age develop the sudden onset of clustering body jerks, often out of sleep, with a chaotic EEG, and occasional loss of developmental skills. Treatments include ACTH and vigabatrin, but these drugs have serious side effects, and vigabatrin requires lots of paperwork in order to prescribe nowadays. Knowing the diet can be provided via an infant formula and has fewer side effects, it’s a natural choice. We found that nearly half of the 23 children we had treated, usually those with tough-to-control infantile spasms, had a 90% or better response, improvement on EEG, and better development by 6 months. Infants under age 1 year and who had failed no more than three drugs did better.

Based on this, we have now more than doubled our use of the ketogenic diet for infantile spasms and are seeing the same results—we have treated 2010, by 104 children with infantile spasms. About two-thirds will have a >90% reduction in spasms. We are also using the diet for new-onset infantile spasms (rather than steroids or vigabatrin).

Alexander was a 6-month-old baby when he developed infantile spasms. After initially responding to ACTH, his seizures returned and didn’t go away with a second round of ACTH. Alexander then tried three other medications before starting the ketogenic diet. Although his spasms did not vanish on the diet, they were reduced from 10 clusters a day to 2, and his EEG improved. Best of all, his alertness and development improved as well. He remained on the diet for 2 years total and is now only on a single drug.

In this disorder, children (often ages 3–5 years) present with the sudden onset of head drop seizures and occasionally cognitive decline. Although many neurologists think this is Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, the EEG often shows periods of normal background making this less likely. Traditional medicines such as Depakote® and Keppra® are only occasionally useful. We have used the ketogenic diet for about a dozen of these children with occasionally dramatic success. Allie is one such child, and her story is even highlighted on our epilepsy center’s Web site as a sidebar. Allie became seizure-free within 2 weeks of starting the diet, and her medications were stopped quickly after. Several patients with likely Doose epilepsy have also been similar responders on the modified Atkins diet. Dr. Douglas Nordli from Chicago and Dr. Sudha Kessler from Philadelphia have also seen this improvement with patients having Doose epilepsy, and both have published their experience in medical journals. For more information, go to http://www.doosesyndrome.com.

In a combined study from Johns Hopkins and the Massachusetts General Hospital, we found 12 children with tuberous sclerosis complex (multiple brain tubers; ash-leaf spots on the skin; heart and kidney tubers; epilepsy) that were started on the ketogenic diet did very well. Many had a history of infantile spasms in the past, but none at the time of starting the diet. All but one child had half their seizures improve, and half had >90% improvement. Five children even had several months seizure free. Although there are a limited number of patients, Dr. Elizabeth Thiele and our group agree that the ketogenic diet is a good option for patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Interestingly, at least in our experience, having this condition also made it more likely for seizures to come back in those children who became seizure free on the diet (sometimes years later). In that way, it’s possible that although the diet is a big help for tuberous sclerosis, it may be a more long-term treatment than for Doose syndrome or certainly infantile spasms.

In this rare condition, the molecule that allows glucose to cross into the brain to be used as fuel is missing. Children will often have seizures and cognitive delay until this is recognized, most often by noticing a very low glucose level in the spinal fluid after a spinal tap. Logically, if the body cannot use glucose, then fat makes sense as a better alternative fuel. The ketogenic diet is considered the first and only therapy of choice for children with GLUT-1. More information for this disorder can be found on the internet and in Chapter 24.

Perhaps one of the easiest groups of children to place on the ketogenic diet are those who do not eat solid foods. If the diet is given just as liquids, it avoids all compliance issues. Infants on formula or are breastfeeding will need to directly switch to one of several ketogenic formulas (see Chapter 8 for instructions), which can then be continued for months to years. As infants turn into toddlers, small amounts of solid ketogenic baby foods can be introduced after 1–2 months. Children that are fed using gastrostomy tubes (G-tubes) can also be started on the diet without compliance issues. In a study performed at Johns Hopkins, since 1998, more than a quarter of all patients started on the diet did so using formula only. Nearly 60% had a >90% improvement in seizures, double the average ketogenic diet patient. In any child in an intensive care setting for epilepsy, the diet can be easily started or continued via a temporary nasogastric tube.

The formulas available are very palatable with a taste similar to most other infant formulas. It is easy to calculate for the dietitian and can be soy-based, milk-based, or even hypoallergenic. There is also less room for error and less education involved for parents. The presence of a gastrostomy tube also allows medications to be provided without carbohydrate sweeteners or flavoring. Patients who are ill on the ketogenic diet can occasionally have acidosis and dehydration, but having a gastrostomy tube helps avoid this. Lastly, insurance companies often cover formula in children with gastrostomy tubes because it is being used as a medical therapy rather than for solely nutritional purposes.

Kaylee was a 9-year-old girl with cerebral palsy and daily drop seizures. For years she had a gastrostomy tube for her nutrition and was fed continuously at night only. After failing to achieve seizure control with Keppra and Lamictal, her parents asked to try the ketogenic diet. During the ketogenic diet admission week, switching from Pediasure to KetoCal® was easy for her parents to do and did not cost them any more money per month. Within 2 weeks her seizures were significantly reduced, and the family did not find the diet much different than her previous formula, except for the occasional lab work and checking urine ketones.

There are several other conditions in which the diet may be very helpful. They include Dravet syndrome, absence epilepsy, Rett syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and mitochondrial disorders. In these conditions, several articles have reported the ketogenic diet as leading to superb results. There are conditions, however, in which the diet is not a good idea. These conditions are presented in the following list, which is reproduced in part from the 2009 consensus statement.

Contraindications to the use of the ketogenic diet:

Absolute

Carnitine deficiency (primary)

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT) I or II deficiency

Carnitine translocase deficiency

β-oxidation defects

Medium-chain acyl dehydrogenase deficiency (MCAD)

Long-chain acyl dehydrogenase deficiency (LCAD)

Short-chain acyl dehydrogenase deficiency (SCAD)

Long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA deficiency

Medium-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA deficiency

Pyruvate car+boxylase deficiency

Porphyria

Relative

Inability to maintain adequate nutrition

Surgical focus identified by neuroimaging and video-EEG monitoring

Parent or caregiver noncompliance

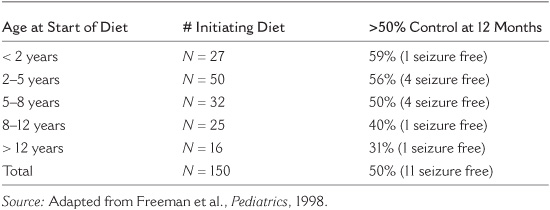

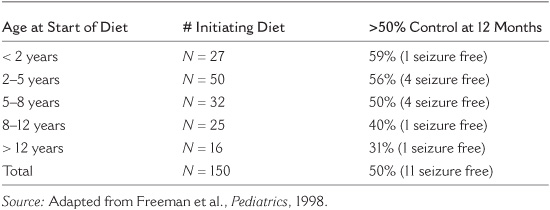

Probably not, but there is a slight trend toward improved seizure control in younger children (see Table 5.1). Younger children often can maintain high ketosis for long periods and compliance is less of a problem. We feel, as do other doctors, that infants may be one of the ideal groups for the diet for this reason. They certainly need extra care due to growth issues, but can do very well on the diet.

What about adolescents and adults? Most centers will tell parents that the diet is impossible to do for a teenager. In a study from both our group and Dr. James Wheless’s at the University of Texas at Houston, we combined our teenage population on the diet (45 teens in total) and found that compliance was very good, seizure reduction was similar to younger children, and side effects were low. Of the participants, 44% were able to stick it out for a year. Menstrual irregularities happened in almost half of teenage girls, but this is tough to separate out from the normal irregularities of this age and the effects of medications. In general, at present we tend to use the modified Atkins diet for most teenagers.

TABLE 5.1

The Effect of Age on Outcomes of the Ketogenic Diet

Dr. Michael Sperling, Dr. Maromei Nei, and their group of epilepsy specialists at the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia have used the diet for adults for years, with good results. Cholesterol does increase, and compliance can be an issue, but ketosis occurs and seizures often improve. We also mostly use the modified Atkins diet here at Johns Hopkins for adults over age 18 years, and we have had good results.

Jack was a 34-year-old man from Ohio with intractable seizures. After failing to see any improvement with a temporal lobe resection, he became interested in alternative approaches. Herbs and biofeedback failed to help his seizures, so he found our center over the internet and enrolled in our Atkins diet study for adults. After 3 months, his seizures had dropped from five per month to two, and he was making moderate ketones consistently. However, he was unprepared for how difficult the diet would be to follow and decided to stop. Interestingly, since that time his seizures have remained somewhat improved.

The level of a child’s intelligence is not a criterion for selecting appropriate candidates for the diet. Some of the most dramatic successes have occurred in the most profoundly handicapped children. Other successes have occurred in children with normal intelligence. However, it is important for parents to carefully assess their goals and expectations before starting the diet. Parents may believe that their child’s substantial intellectual delay is due solely to the medications and that if they could only get their child off medication everything would be back to normal. Such parents are likely to be disappointed.

On the other hand, electrical seizures may be even more frequent than clinical seizures and may indeed interfere with intellect. Children with frequent myoclonic or drop seizures may have very chaotic EEGs and may have had intellectual deterioration since the start of their seizures. Such children may experience striking intellectual improvement if the diet is effective in controlling their seizures.

In short, the diet is intended primarily to control seizures. Decreasing and discontinuing medications is certainly important, but only a secondary goal. Improving intellect is a hope and a desire, but that is not what the ketogenic diet is designed to do.

One of the only things that truly will lead to diet failure is a lack of commitment and time to make it work, which can be both the fault of the family and the physicians. The diet requires a significant investment of the entire family to spend a week to start and learn the diet in the hospital, calculate meal plans and weigh foods, and avoid cheating. A family in which the parents are divorced and one parent does not believe in the diet will nearly always be a ketogenic diet failure. Similarly, if grandparents or other caregivers do not agree that the diet is worth trying and make meals for children that will sabotage the diet, obviously this will not work.

Giving the diet at least 1–2 months to work before making any big medication changes is also crucial. Close communication with the physician and dietitian is not only a good idea, it’s mandatory to make the diet work. The hospital team also must spend considerable time and energy to make the diet program effective with email and phone contact with families, handling illnesses and providing support, and watching and monitoring for both expected and unexpected problems.